Abstract

Introduction

Scapula alata (SA) is a condition characterized by medial winging and reduced upward rotation of the scapula during arm elevation, leading to impaired shoulder function. This study aimed to assess diagnostic and treatment approaches for SA in public hospitals in Denmark.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was undertaken using a self-administered questionnaire to healthcare professionals across departments in public hospitals in Denmark. The survey investigated diagnostic practices, including referral to electroneurography (ENG), ICD-10 coding and local treatment practices.

Results

A total of 20 hospital departments completed the questionnaire. Six hospitals use ENG as part of their diagnostic practice. Six different ICD-10 codes were reported for SA. Annual patient numbers ranged from 0 to 20, with four hospitals accounting for most of the patients. Doctors and physiotherapists are the primary healthcare providers involved in the diagnostic and treatment process. Only four hospitals reported written local guidelines for SA treatment. Treatment approaches included exercise therapy, brace treatment, surgery, and in some cases, a waiting approach.

Conclusion

The survey revealed significant variations in diagnostic and treatment practices for SA across Denmark. This emphasizes the need for further research and national and international consensus, including standardized guidelines for diagnostics and treatment practices.

Keywords: scapula alata, treatment variations, public hospitals, cross-sectional survey

Introduction

Scapula alata (SA) is a condition characterized by medial winging and decreased upward rotation of the scapula from the thorax during elevation of the arm. Scapula alata is most commonly caused by impaired innervation of the long thoracic nerve, often due to trauma or nerve inflammation (thoracic longus neuritis). This leads to pain, weakness in the serratus anterior muscle, altered scapular glenohumeral movement and limited active shoulder mobility.1,2 Scapula alata often affects individuals in the working-age population and can have significant consequences, especially for those with shoulder-intensive occupations but also in everyday activities.2,3

The incidence of SA remains unclear, but studies suggest that it may be more prevalent than previously thought.4,5 Another study suggests that the incidence of serratus anterior palsy is approximately 0.2% of all shoulder disorders and occurs on the dominant side in 86–95%. 6 Diagnosing SA can be complex, often leading to delayed targeted treatment initiation.4,7

Electroneurography (ENG) is used in some studies to diagnose specific nerve lesions, either of the long thoracic nerve or accessory nerve, supporting clinical diagnosis.8–11 It is assumed that a significant proportion of SA patients experience spontaneous remission of symptoms, including nerve and muscle function improvements. However, this remission is often prolonged and can last up to two years. 12

When an SA is suspected, patients are usually referred to orthopaedic departments, where treatment options can be conservative or surgical. 12 Currently, there is no national or international consensus on conservative treatment, which may involve exercise therapy, brace treatment or a waiting approach without active intervention. Limited evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of various conservative treatments, and it remains unclear which treatment modalities, including surgical approaches, are most effective.9,11–14 Furthermore, it is unknown which treatment options are being offered to this patient group nationwide. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to map the current treatment approaches that are offered to patients with SA in Denmark.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted using a quantitative self-administered questionnaire survey distributed to doctors, physiotherapists and other healthcare professionals through the REDCap database. 15 The study is reported according to the STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies. 16

The questionnaire was electronically sent via email to selected professionals from relevant hospital departments known by the expert group to have substantial insight into the management of patients with SA. These contacts were also asked to identify any other relevant contacts across departments and hospitals. Next, we contacted orthopaedic centers that provide orthoses to hospitals treating patients with SA and asked them to identify relevant contacts in departments where this patient group is managed. Finally, a detailed search was performed to identify contacts from the remaining hospitals in Denmark. In this phase, we primarily focused on orthopaedic surgery departments as well as physiotherapy and occupational therapy departments, as previously collected data indicated that these departments are often involved in the treatment of patients with SA. In a corresponding email, the staff was encouraged to forward the questionnaire to relevant personnel or departments if it did not initially reach the intended recipients. In cases of non-response, a follow-up email was sent, and ultimately, telephone contact was established to obtain the remaining responses. In the correspondence email, professionals were asked to complete the questionnaire on behalf of their department and therefore only submit one response per department.

The choice of method was based on the purpose of collecting data from a larger group of respondents. The method allowed healthcare professionals to complete the questionnaire at their convenience and required a relatively short amount of time, which was considered appropriate for achieving the desired number of responses.

The questionnaire was developed by an expert group of experienced physiotherapists, orthopaedic surgeons and researchers from the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Viborg Regional Hospital, and Elective Surgery Centre, Silkeborg Regional Hospital. The clinical members of the expert group were all experienced in diagnostics and treatment of patients with SA. The group developed a questionnaire aggregating information about diagnostic and treatment approaches used in the department, encompassing a range of potential treatment options for respondents to consider. Furthermore, options were made for the inclusion of other categories not pre-identified by incorporating an ‘other’ category to capture unforeseen responses. The questions were formulated briefly and precisely, as this method did not allow for control over whether the questions were correctly understood.

Furthermore, the questionnaire gathered information about the use of diagnostic ICD-10 codes, and the annual number of patients with SA in the department. The survey was tested by the expert group before it was distributed, which led to minor adjustments of the questions. The questionnaire with the specific answer categories can be found as Supplementary material. Under Danish law, health science questionnaire surveys that do not involve human biological material do not need ethical approval. 17

Statistics

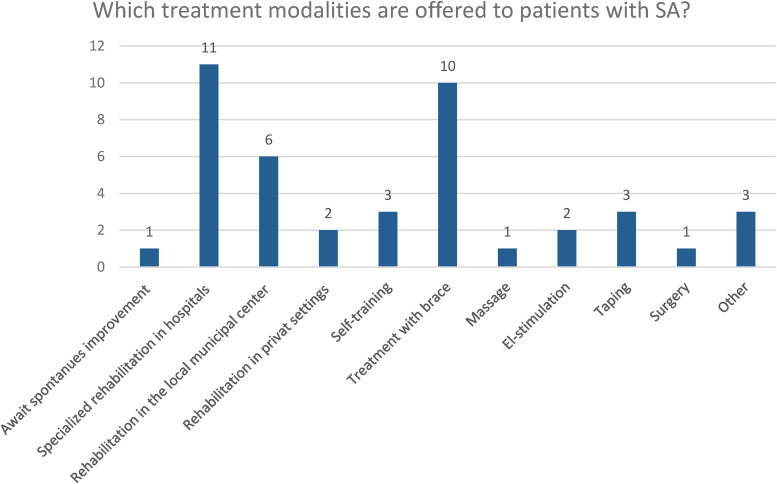

The primary results, including the treatment modalities offered to patients with SA, were presented in a bar chart, displaying the number of Danish hospitals that offer each specific treatment. The secondary results were presented as plain numbers (N). Data from REDCap was uploaded to Excel to generate figures.

Results

A total of 20 responses were obtained through REDCap from Orthopedic departments, Physio- and/or Occupational therapy departments, and one Oncology department. Out of these, two hospitals declined participation with the response: ‘I do not want to participate’. Additional email correspondence was conducted with nine hospitals that chose not to respond, either because they did not treat this specific patient group or because they referred them to another collaborative hospital. The survey was distributed to one hospital that did not provide a response or an explanation for its non-response.

Diagnostics

In six hospitals, referral to ENG examination is used as a part of the diagnostic pathway. In additional seven departments, ENG examination is used only in certain cases, including absence of progression, traumatic injuries, severe paralysis, prognosis assessment and to exclude SA in the absence of classical symptoms. Six different ICD-10 codes were used in the diagnostic documentation of SA. The most frequently used code was DM759 (Shoulder lesion, unspecified), followed by DM758 (Other shoulder lesions). In addition to these, the following codes were reported: DM568, DQ688J, DM792b and DG588. In six departments, the response ‘Do not know’ was given, when asked which diagnostic code was used for patients with SA (Supplementary material).

Treatment setting and procedures

In nine departments, a maximum of five patients receive treatment annually, four departments treat between 6 and 10 patients, two departments treat 11–20 patients and two departments treat more than 20 patients annually. One department reported not seeing any patients with SA. Doctors and physiotherapists primarily examine and treat patients with SA, but in one department, occupational therapists diagnose and treat this patient group. Only four departments had written clinical guidelines for the management of patients with SA. The most common treatment offered to this patient group is exercise therapy (Supplementary material).

Most hospitals refer patients to specialized rehabilitation in hospitals (N = 11) or general rehabilitation in the local municipal center (N = 6). Ten departments use a combination of brace treatment and rehabilitation, which can occur in private, municipal and regional settings. One department chooses to await spontaneous improvement without treatment, while another location offers surgery and refers patients to a higher level of expertise. In addition, patients receive treatments such as taping, massage, self-training and rehabilitation in private settings (Supplementary material). The participating hospitals covered a wide geographical area in Denmark (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The number of Danish hospitals (y-axis) that offer a specific treatment (x-axis) for patients diagnosed with scapula alata.

Discussion

This is the first study to provide an overview of diagnostic and treatment procedures for patients with SA in Denmark. Our survey revealed a considerable variation across hospitals, with lack of consensus regarding the use of ENG examination as part of the diagnostic procedures, diagnostic coding and treatment pathways. We found a notable variation in the use of non-specific ICD-10 codes across hospital departments. Moreover, patients with SA are offered various forms of conservative treatments, no treatment, and, in rare cases, surgical treatment. This underlines a national lack of consensus regarding the treatment of these patients, where treatment options offered, most likely reflect local practices and traditions, rather than evidence-based protocols. Consequently, this could compromise the quality of treatment of patients with SA causing clinical uncertainty among healthcare professionals.

The absence of a specific ICD-10 code for SA complicates the effort to gather important data to understand the incidence and demographic characteristics of the SA population, as ICD-10 codes ‘shoulder lesion, unspecified’ and ‘Other shoulder lesions’ include a broad non-specific group of patients with diverse shoulder disorders. The large variation in diagnostics, coding and treatment practice of patients with SA may also be influenced by the potential challenges in diagnosing this relatively rare and sometimes complex condition. 12

The current evidence on outcomes after both surgical and non-surgical treatment for SA is sparse. A recent systematic review based on 23 studies of low to moderate quality 12 found only six studies investigated outcomes following non-surgical treatment and only one study investigating the effect of a specific physical therapy program. However, that study did not report on clinical outcomes such as pain, persistent winging or function. Seventeen studies evaluated surgical treatments. Notably, tendon transfer surgery demonstrated significant improvements in function, pain and shoulder scores for both SA and TP palsy. The review suggests that tendon transfer represents a viable option for patients who do not experience improvement after initial non-surgical treatment. Nevertheless, higher-quality evidence is needed to further validate these findings and to provide additional guidance for clinical practice. Moreover, it emphasizes the lack of studies evaluating clinical outcomes in conservative treatment, potentially leading to overlooked opportunities in conservative management strategies.

Thus, there is an urgent need for high-quality research, to establish consensus about diagnostic criteria for SA and evaluate the effectiveness of different treatment methods to support national and international consensus. This will ensure that patients with SA receive accurate diagnostics and effective treatment, irrespective of their geographic location.

Limitations

The chosen methodology in this study limits our ability to fully comprehend the rationale behind the diverse treatment strategies observed across the country. Furthermore, it was not possible to explore details such as the respondents’ overall knowledge of local practices in their departments, the extent of the use of brace treatment, surgical indications and variations in other diagnostic criteria. Finally, expanding the questionnaire to encompass a broader spectrum of treatment centers, including private clinics, hospitals specializing in rheumatology and neurology and spinal cord centers, could have provided a more comprehensive and nuanced overview of the treatment landscape. Despite this selection, the results are considered useful for providing an overview of the current national treatment of patients with SA.

Conclusion

This study reveals notable national variation in diagnostics and treatment approaches of patients with SA across public hospitals in Denmark. We identified a lack of consensus regarding diagnostics, code practices and treatment regimens for this patient group, which could potentially impact the quality of care provided. There is a great need for further research to establish clear diagnostic criteria and treatment practices for patients with SA.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sel-10.1177_17585732241285330 for Variations in treatment approaches for patients with scapula alata – A national survey across public hospitals in Denmark by Kirstine Lyngsøe Hvidberg, Cecilie Rud Budtz, Grethe Aalkjær, Søren Villumsen, Brian Elmengaard, David Høyrup Christiansen and Helle Kvistgaard Østergaard in Shoulder & Elbow

Acknowledgements

The authors extend our gratitude to all the participating departments in public hospitals in Denmark for their valuable contributions to this study.

Footnotes

Contributorship: The study was primarily conceived and designed by KLH, HKØ and CRB with inputs from GA, SV, BE and DHC. HKØ and CRB secured funds for the study. All authors contributed to the formulation and content of the survey. KLH collected and analysed the quantitative data. The first draft of the paper was written by KLH with substantial input from HKØ and CRB. All authors reviewed and approved the final revised manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This study is funded by Clinic, Education and Research (CER) Communities: Optimizing Patient Pathways.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was not sought for the present study because it explores a current practice and does not include any experimental interventions. Thus it is not required according to ethical regulations. This study was completed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the responders(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Guarantor: KLH

Funding and trial registration: This project is funded by Clinic, Education and Research (CER) Communities: Optimizing Patient Pathways.

ORCID iD: Kirstine Lyngsøe Hvidberg https://orcid.org/0009-0005-1537-2522

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Didesch JT, Tang P. Anatomy, etiology, and management of scapular winging. J Hand Surg Am 2019; 44: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, Savin DD, Shah NR, et al. Scapular winging: evaluation and treatment: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97: 1708–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vetter M, Charran O, Yilmaz E, et al. Winged scapula: a comprehensive review of surgical treatment. Cureus 2017; 9: e1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srikumaran U, Wells JH, Freehill MT, et al. Scapular winging: a great masquerader of shoulder disorders: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96: e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nath RK, Lyons AB, Bietz G. Microneurolysis and decompression of long thoracic nerve injury are effective in reversing scapular winging: long-term results in 50 cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pikkarainen V, Kettunen J, Vastamäki M. The natural course of serratus palsy at 2 to 31 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471: 1555–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galano GJ, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CSet al. et al. Surgical treatment of winged scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466: 652–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng CY, Wu F. Scapular winging secondary to serratus anterior dysfunction: analysis of clinical presentations and etiology in a consecutive series of 96 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2021; 30: 2336–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2008; 1: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seror P, Lenglet T, Nguyen C, et al. Unilateral winged scapula: clinical and electrodiagnostic experience with 128 cases, with special attention to long thoracic nerve palsy. Muscle Nerve 2018; 57: 913–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lafosse T, D'Utruy A, El Hassan B, et al. Scapula alata: diagnosis and treatment by nerve surgery and tendon transfers. Hand Surg Rehabil 2022; 41s: S44–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geurkink TH, Gacaferi H, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, et al. Treatment of neurogenic scapular winging: a systematic review on outcomes after nonsurgical management and tendon transfer surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2023; 32: e35–e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meininger AK, Figuerres BF, Goldberg BA. Scapular winging: an update. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011; 19: 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vastamäki M, Pikkarainen V, Vastamäki Het al. et al. Scapular bracing is effective in some patients but symptoms persist in many despite bracing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473: 2650–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E AD, Egger M, Pocock SJ, et al. STROBE checklist: cross-sectional studies2007. Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/STROBE_checklist_v4_cross-sectional.pdf.

- 17.Projects AoRERoHR. Overview of Mandatory Reporting https://researchethics.dk/ [updated 2024. Section 14(2) of the Danish Act on Committees]. Available from: https://researchethics.dk/information-for-researchers/overview-of-mandatory-reporting.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sel-10.1177_17585732241285330 for Variations in treatment approaches for patients with scapula alata – A national survey across public hospitals in Denmark by Kirstine Lyngsøe Hvidberg, Cecilie Rud Budtz, Grethe Aalkjær, Søren Villumsen, Brian Elmengaard, David Høyrup Christiansen and Helle Kvistgaard Østergaard in Shoulder & Elbow