Abstract

A 2-y-old, intact female, mixed-breed dog was presented to the veterinary hospital with abdominal distension, anemia, and lethargy following a chronic history of nonspecific gastrointestinal signs. CBC and serum biochemistry revealed moderate nonregenerative anemia with neutrophilia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperglobulinemia, hypoglycemia, decreased urea and creatinine, and hypercholesterolemia. Abdominal radiographs and ultrasound revealed a large heterogeneous mesenteric mass and ascites. Abdominocentesis confirmed septic peritonitis with filamentous bacteria. Fine-needle aspiration of the mass yielded pyogranulomatous inflammation and hyphae. An exploratory laparotomy revealed a large cranial abdominal mass with granulomas present throughout the abdominal cavity. Due to the poor prognosis and disseminated disease, the owner elected euthanasia. Postmortem and histologic examinations detected intralesional mycetomas and bacterial colonies within the mesenteric masses. 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR and sequencing using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections identified Nocardia yamanashiensis, Nocardioides cavernae, and Nocardioides zeicaulis. Fungal culture, PCR, and sequencing confirmed Scedosporium apiospermum. Our report highlights the importance of molecular methods in conjunction with culture and histologic findings for diagnosing coinfections caused by infrequent etiologic agents. Additionally, we provide a comprehensive literature review of Scedosporium apiospermum infections in dogs.

Keywords: dogs, Nocardia yamanashiensis, Nocardioides cavernae, Nocardioides zeicaulis, nocardiosis, peritonitis, scedosporiosis, Scedosporium apiospermum

A 2-y-old, 12.8-kg, intact female, mixed-breed dog was presented to the Auburn University Small Animal Veterinary Teaching Hospital Emergency Service (Auburn, AL, USA) with a 1-wk history of a distended abdomen, anemia, and lethargy. The dog had chronic nonspecific gastrointestinal signs that included vomiting, hyporexia, and progressive weight loss unsuccessfully managed with famotidine (1 mg/kg PO q24h, 7 d). The patient was up-to-date with vaccinations (as per the owner) and was not being treated with any immunosuppressants including corticosteroids.

On presentation, the patient was quiet but alert, with a 39.3°C body temperature (RI: 38.3–39.2°C), tachypnea (44 bpm, RI: 18–34 bpm), and pale-pink and moist oral and conjunctival mucous membranes. CBC revealed a moderate normocytic, normochromic, nonregenerative anemia (Hct 0.22 L/L; RI: 0.38–0.59 L/L) with mild anisocytosis and slight polychromasia, and marked leukocytosis (47.6 × 109/L, RI: 5.1–17.4 × 109/L) characterized by mature neutrophilia (35.7 × 109/L; RI: 2.6–10.4 × 109/L) with a left shift (5.2 × 109/L; RI: 0.0–0.3 × 109/L), monocytosis (2.8 × 109/L; RI: 0.2–1.2 × 109/L), and a slight toxic change in neutrophils. Serum biochemistry showed decreased albumin (11.7 g/L; RI: 30.0–43.0 g/L), glucose (2.77 mmol/L, RI: 4.22–6.44 mmol/L), urea (3.0 mmol/L; RI: 3.2–12.1 mmol/L), creatinine (26 μmol/L; RI: 44–141 μmol/L), and increased globulin (62 g/L; RI: 20–43 g/L) and cholesterol (9.4 mmol/L; RI: 3.4–8.7 mmol/L). A large peripancreatic mass with several other masses and effusion were found during an abdominal ultrasound. Abdominocentesis confirmed an exudate (total solids: 51 g/L; cells: 54.7 × 109/L); the differential cell count was ~72% nondegenerate neutrophils, 21% macrophages, and 8% lymphocytes.

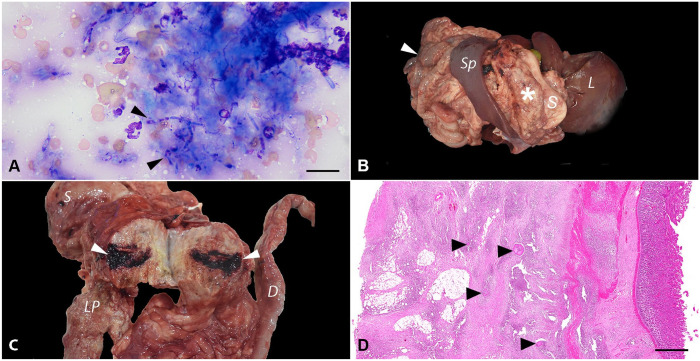

A direct smear of the abdominal fluid yielded very rare filamentous rod-shaped bacteria that were found intracellularly and in a few small extracellular mats and microcolonies. Macrophages were variably vacuolated and occasionally contained intracytoplasmic phagocytized debris. Fine-needle aspiration of the largest mass revealed numerous degenerate neutrophils and epithelioid macrophages surrounding dense mats of fungal organisms that were pleomorphic and varied from round-oval yeast (sometimes with narrow-based budding) to elongated, 2.5–4-μm, variably septate hyphae or pseudohyphae with occasional bulbous ends and thin colorless walls or capsules and granular blue-pink internal structures (Fig. 1A). Exploratory laparotomy confirmed widespread peritoneal granulomas. A large, firm, irregular mass encompassed most of the cranial abdomen, including the entire small intestinal tract and mesentery, greater curvature of the stomach and omentum, and head of the spleen. Given the extension of the lesions in conjunction with a poor prognosis of an intra-abdominal fungal infection, the owner elected euthanasia.

Figure 1.

Systemic nocardiosis, nocardioidiosis, and scedosporiosis coinfection in a 2-y-old mixed-breed dog. A. Fine-needle aspirate of a mesenteric mass. Numerous neutrophils surround dense mats of elongate, variably septate, 2.5–4-μm hyphae or pseudohyphae with occasional bulbous ends and thin colorless walls or capsules and granular blue-pink internal structures (arrowheads). Wright–Giemsa. Bar = 50 µm. B. Postmortem examination. An 11 × 12 × 6.5-cm tan, firm mass (asterisk) effaced the greater omentum between the greater gastric curvature and the left pancreatic lobe. The intestines were diffusely adhered (arrowhead). L = liver; S = stomach; Sp = spleen. C. The mass was granular on cut surface, with 0.1–0.3-cm, yellow necrotic foci, and extensive hemorrhagic areas (arrowheads). D = duodenum; LP = left pancreatic lobe; S = stomach. D. Subgross photomicrograph of the duodenum. The serosal layer and the mesenteric adipose tissue are markedly expanded by pyogranulomatous inflammation with intralesional mats of filamentous bacteria (sulfur granules; arrowheads). H&E. Bar = 1 mm.

On postmortem examination, the dog was in poor nutritional condition (body condition score 2 of 9). The peritoneal space contained ~100 mL of dark-red fluid. The peritoneum was diffusely thickened, with dark-red discoloration and extensive fibrous adhesions encompassing the liver, pancreas, intestine, stomach, and mesentery. An 11 × 12 × 6.5-cm, tan, firm mass effaced the greater omentum between the greater gastric curvature and the left pancreatic lobe (Fig. 1B). On cut surface, the mass was granular, with 0.1–0.3-cm, yellow necrotic foci, and extensive hemorrhagic areas (Fig. 1C). Additional masses were present throughout the abdominal wall. The intestines were diffusely adhered and markedly effaced by similar masses found in the peritoneum, with the intestinal serosa diffusely dark-red and covered with fibrin. The liver adhered to the body wall. White-to-beige, round, firm, 2–4-cm nodules were on the left liver lobes.

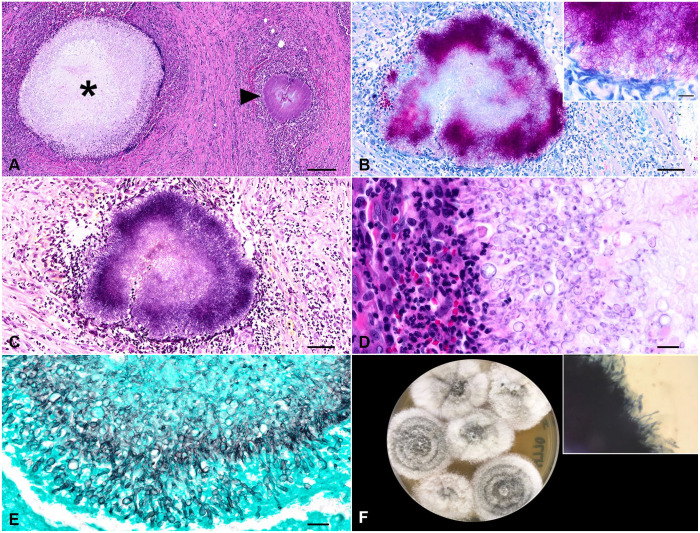

On histologic examination, the serosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal tract and the adjacent mesenteries were markedly expanded and effaced by a plethora of reactive fibroblasts amid collagen bundles admixed with scattered large, clear, well-delineated vacuoles. The tissue was obscured by extensive, pyogranulomas composed of a core of neutrophils, epithelioid macrophages, and fewer plasma cells and lymphocytes surrounding central mats of radiating filamentous bacteria (sulfur granules) and central mats of large, non-pigmented fungi (mycetoma; Figs. 1D, 2A). Fite and Gram stains highlighted 1-µm thick, filamentous, variably gram-positive, acid-fast bacteria and occasional 1-µm gram-positive cocci bacteria (Fig. 2B, 2C). The fungal hyphae were septate, 2–6-µm wide, irregularly branching, with 4–7-µm wide terminal bulbous dilations (Fig. 2D), highlighted with Gomori methenamine silver stain (Fig. 2E). In the remaining gastrointestinal tissue, necrotic debris, edema, and hemorrhage were scattered. Histologic findings were similar within the intestinal serosa and lymph nodes. Other histopathologic findings included marked pulmonary congestion and edema, focal lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic interstitial pneumonia, eosinophilic and granulomatous hepatic capsulitis, moderate periportal lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis, and cholestasis. The eosinophilic and pyogranulomatous inflammation extended to the retroperitoneal and perirenal adipose tissue and the renal capsule.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs of the mesenteric mass. A. Pyogranulomas surround central mats of radiating filamentous bacteria (sulfur granules; arrowhead) and central mats of large, non-pigmented fungi (mycetoma; asterisk). H&E. Bar = 200 µm. B. Fite-stained, 1-µm thick, filamentous, acid-fast bacteria. Bar = 50 µm. Inset: filamentous, acid-fast bacteria. Bar = 10 µm. C. The filamentous bacteria were variably gram-positive. Gram. Bar = 50 µm. D. The mycetomas were surrounded by macrophages and neutrophils. H&E. Bar = 20 µm. E. The fungal hyphae were non-pigmented, septate, 2–6-µm wide, branching, with 4–7-µm wide terminal bulbous dilations. Gomori methenamine silver. Bar = 20 µm. F. Fungal culture from mesenteric tissue. Inhibitory mold agar, 4 d. The growth of the mold started white and cottony, turning light-gray with age and had a tan reverse. Inset: KOH with Parker ink revealed copious branching, septate, hyaline hyphae.

The aerobic culture from mesenteric tissue yielded a heavy growth of mold. The mesenteric tissue plated to Sabouraud dextrose agar (BD Difco), inhibitory mold agar (IMA; BD BBL), and mycobiotic agar (BD BBL) yielded, by day 4, growth of a mold that started white and cottony, with the growth on IMA turning a light-gray with age and having a tan reverse (Fig. 2F). Use of KOH with Parker ink revealed copious branching, septate, hyaline hyphae (Fig. 2F inset). The fungal culture was submitted for identification to the Fungus Testing Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center (San Antonio, TX, USA). Phenotypic characterization and DNA sequencing of 3 genetic loci were used: internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of the rDNA, and partial β-tubulin (TUB) and calmodulin (CAM) genes. Amplification PCR of all target loci was performed with negative and positive controls following validated and published procedures.7,41

BLASTn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) searches were performed. Top matches with sequences of type (CBS 117407) or reference (FMR-8619) strains in BLASTn searches were considered significant. ITS, CAM, and TUB are considered good markers for delimiting Scedosporium species, and ITS and CAM are considered optimal markers. 40 Top matches were with Scedosporium apiospermum type strain CBS 117407T, with 100% base pair match for ITS (GenBank LC739048) and 96.75% for TUB (LC739115) and with the reference strain FMR-8619, with 99.22% match for CAM (GenBank AJ890192). Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of the lymph nodes were submitted to the Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory at Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN, USA) for subgenic 16S ribosomal DNA PCR and next-generation sequencing, followed by analysis with Geneious (Dotmatics) and BLAST, using a published method. 24 BLASTn searches showed 100% identities with sequences of the following type strains: Nocardia yamanashiensis (GenBank NR_117395.1), Nocardioides cavernae (NR_156135.1), and Nocardioides zeicaulis (NR_148831.1).

Nucleotide data from our study are available in GenBank under the following accessions: Nocardia yamanashiensis (PP565356), Nocardioides cavernae (PP565357), Nocardioides zeicaulis (PP565358), S. apiospermum (calmodulin PP621216, β-tubulin PP621217). Overall, the ancillary molecular assays in combination with gross and histologic findings confirmed systemic coinfection of Nocardia yamanashiensis, Nocardioides cavernae, Nocardioides zeicaulis, and S. apiospermum. Our histologic findings that supported Nocardia infection were the dense mats of Fite-positive, gram-positive filamentous bacteria as reported previously. 34 The histologic findings that support Scedosporium were the thin (3–5-µm wide), non-pigmented, irregularly branching, septate hyphae with bulbous dilations. 51

Nocardia spp. are in the class Actinomycetes, order Mycobacteriales, family Nocardiaceae. 50 French veterinarian Edmond Nocard first described the bacteria within this genus in 1888 on the island of Guadeloupe while studying bovine farcy, a condition causing granulomatous inflammation, abscesses, and pulmonary contention (sic) in cattle now attributed to Nocardia farcinica. 15 Nocardia spp. are saprophytic bacteria that are gram-positive, catalase-positive, partially acid-fast, non-motile aerobes that form characteristic beaded filamentous branches.15,50 Found worldwide, Nocardia spp. are environmental bacteria involved in plant decomposition, with pathogenic species isolated from house dust, garden soil, beach sand, swimming pools, and tap water. 56 Nocardiosis is a suppurative-to-granulomatous, localized, or disseminated opportunistic infection affecting humans and many species of animals that is observed more frequently in immunocompromised hosts.46,50

Various Nocardia spp. are pathogenic in the dog, including: N. abscessus, N. asteroides, N. brasiliensis, N. caviae, N. cyriacigeorgica, N. otitidiscaviarum, and N. veterana. 56 Clinical manifestations of primary nocardiosis are varied and depend on the route of exposure, which can include local cutaneous trauma or inhalation of contaminated particles. 28 Young outdoor dogs frequently develop subcutaneous abscesses secondary to foreign body migration or puncture wounds. 56 Once inoculated, nocardiosis can remain localized (either respiratory or cutaneous-subcutaneous) or have systemic hematogenous spread to other organs. 28 Disseminated or systemic nocardiosis usually develops in young and immunosuppressed dogs. 56 The chronic use of immunosuppressive medications increases the risk of infection. 56 Initially beginning as pulmonary nocardiosis, dogs exhibit peracute clinical signs such as tachypnea, hemoptysis, hypothermia, collapse, and death, with the dissemination of the organisms from the lung into other organ systems leading to signs such as lethargy, fever, decreased appetite, and signs related to the location of infection. 46 The organs involved most frequently in disseminated nocardiosis are skin and subcutaneous tissues, kidneys, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, CNS, eye, bone, and joints. 46 Treatment options for infections that remain localized include surgical debridement of abscesses and fistulous tracts in combination with antimicrobials, including sulfonamides, and discontinuing any immunosuppressive therapy. 46 The prognosis is poor for disseminated nocardiosis, and treatment options are limited. 46

In our case, 16S rRNA PCR and next-generation sequencing allowed the detection of 3 species of opportunistic bacteria, 2 of them apparently without previously documented medical relevance. Molecular methods, rather than culture, are a reliable source of species identification through sequence analysis of 16S rRNA PCR products. 46 Other molecular methods, such as DNA-DNA hybridization and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), allow the differentiation of closely related species.4,53 Nocardia yamanashiensis has been isolated sporadically from subcutaneous lesions in humans.2,22,35 Additionally, we identified 2 species belonging to the genus Nocardioides, a genus in the class Actinomycetes, order Propionibacteriales, family Nocardioidaceae. 49 Nocardioides spp. are gram-positive, non–acid-fast, catalase-positive, aerobic, and mesophilic bacteria with a ubiquitous distribution. 23 Nocardioides spp. have been isolated from environmental sources including soil, plants, and aquatic environments.18,23,49 Specifically, Nocardioides cavernae was first isolated from a soil sample from a karst cave in Xingyi County in Guizhou province, southwestern China 18 ; Nocardioides zeicaulis was retrieved from the stem tissue of a healthy maize plant. 23 Nocardiosis refers strictly to the infections caused by Nocardia spp. 15 and, to date, there are no medically relevant species or strains within the Nocardioides genus. 49 Given the detection of 2 species within the Nocardioides genus involved in infectious processes in our case, we propose the term “nocardioidiosis” to define infection caused by these bacteria.

Fungi belonging to the Scedosporium spp. complex are versatile and widely distributed organisms that are important human and veterinary pathogens. 12 Scedosporium spp. cause cutaneous, subcutaneous, or disseminated infections in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts, either as primary or opportunistic pathogens.10,40 The route of infection is through inoculation by minor penetrating trauma, through exposed wounds, or inhalation. 10 Scedosporiosis is an infection caused by Scedosporium spp., and sporadic infections in dogs have been attributed to Allescheria boydii, 21 Monosporium apiospermum, 52 Pseudallescheria boydii,1,3,13,32,44,54,55 Scedosporium inflatum, 42 S. apiospermum,5,6,8,9,11,20,25,33,36–39,43,45,48,51,57 and S. prolificans.14,19,47 However, the taxonomy of Scedosporium spp. is rather complex given that it has been subjected to continuous changes since the twentieth century. 10 Such changes within the nomenclature are somewhat confusing and worth clarification when retrieving canine scedosporiosis cases from the literature to avoid considering 2 names as different etiologic agents.

Allescheria boydii has been renamed Pseudallescheria boydii. 31 Monosporium apiospermum was renamed S. apiospermum, 10 and S. inflatum and S. prolificans are now known as Lomentospora prolificans. 30 Scedosporium is the anamorph genus of the teleomorphic Pseudallescheria in the family Microascaceae. 26 Molecular phylogenies published in the last decade led to comprehensive changes in fungal taxonomy and nomenclature and the abolition of the dual nomenclature that was originally based on the anamorph/teleomorph concept of fungi.16,26 This led to the comprehensive revision of the Scedosporium/Pseudallescheria genus, and Scedosporium was adopted as the current name for the genus following the one name/one fungus concept. A comprehensive phylogenetic assessment of the Microascaceae led to the exclusion of S. prolificans from Scedosporium and adoption of Lomentospora prolificans, which is the older name of S. prolificans. 30 The genus Scedosporium includes the S. apiospermum complex (S. angustum, S. apiospermum, S. boydii, S. ellipsoideum, S. fusarium), S. aurantiacum, S. cereisporium, S. dehoogii, S. desertorum, and S. minutisporum.16,17,26,30 Thus, the term scedosporiosis refers to the infections caused exclusively by Scedosporium spp.

S. apiospermum infection has been reported in dogs; affected animals were 8-mo-old to 10-y-old (Table 1). Clinical presentations include unilateral rhinitis, superficial keratitis, cutaneous or subcutaneous infections, localized skeletal infections, and disseminated or localized visceral infections (Table 1). The prognosis for localized infections is favorable after antifungal treatment with voriconazole, itraconazole, terbinafine, or ketoconazole in combination with surgical debridement.6,8,9,25,51 The prognosis is guarded-to-poor in cases with disseminated visceral infection. 11 However, extended remission after surgical removal in combination with systemic antifungal therapy has been reported in cases of visceral disseminated infection.48,51,57 In our case, the extension of the lesions made surgical treatment nonviable; thus, euthanasia was elected and medical treatment was not considered.

Table 1.

Documented cases of Scedosporium apiospermum infections in dogs.

| Breed | Sex | Age | Etiology, clinical, and pathologic findings | Infection distribution | Diagnosis | Follow-up | Location | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German Shepherd | M | 8 mo | Corneal ulceration | Keratomycosis left eye | Culture | Topical 1% miconazole and gentamicin; no follow-up was available | USA | 32 |

| American Staffordshire Terrier | M | 10 mo | 6-mo history of mucopurulent nasal discharge; neutrophilia | Right nasal cavity | Culture | Improvement 7 mo after diagnosis with ketoconazole (20 mg/kg) and amoxicillin (10 mg/kg) | Spain | 6 |

| Labrador Retriever | F | 2 y | 8-mo bilateral mucopurulent nasal discharge; mild leukocytosis | Left nasal cavity | Culture | Recovery after 4-mo treatment with itraconazole (5 mg/kg) and intranasal clotrimazole | Spain | 8 |

| Siberian Husky | F | 2 y | 6-mo history of sneezing and right nasal mucus discharge | Right nasal cavity | Culture | Endoscopic removal of the mass; no recurrent lesion 7 mo after | New Zealand | 9 |

| German Shepherd | F | 6 y | 3-d rear limb motor disorder and an episode of fever 4 wk before presentation; neutrophilia and hyperproteinemia; Leishmania coinfection | T13-L1 discospondylitis osteomyelitis | PCR | Euthanasia due to poor prognosis | France | 20 |

| Rhodesian Ridgeback | CM | 2 y | Immunosuppressant therapy for idiopathic immune-mediated polyarthritis and immune-mediated hemolytic anemia; 2-d history of lethargy and anorexia; nonregenerative anemia, thrombocytopenia | Lymphocutaneous (rump, lateral front leg, and right cranial shoulder) | Culture | No recurrence of the lesions 108 wk after being referred; treatment regime was itraconazole (5 mg/kg), azathioprine (2 mg/kg), and terbinafine (5 mg/kg) | Australia | 5 |

| Mixed breed | SF | 3.5 y | 1-mo history of right nasal discharge | Right nasal cavity | Culture | Resolution after topical treatment with 1% clotrimazole infusion; no recurrence after 12 mo | Australia | 39 |

| Norfolk Terrier | CM | 6 y | 21-d painful ulcer left eye; systemic corticosteroids for 3 mo for IBD (prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg) | Ulcerative keratitis left eye | PCR | Complete resolution after 28-d topical treatment with 1% voriconazole | Denmark | 38 |

| Australian Shepherd | M | 7 mo | Corneal ulceration OD; foreign body removed 4 d before presentation | Corneal ulcer OD | Culture | Resolved after 34-d topical treatment with 1% itraconazole and 0.3% gentamicin sulfate | Australia | 37 |

| Basset Hound | SF | 5 y | 4-mo hematuria, stranguria, urinary incontinence | Dorsal wall of the urinary bladder and left ureter | PCR | Surgical removal and voriconazole; no recurrence 1.5 y follow-up | USA | 25 |

| Bull Terrier | SF | 4 y | 20-d history of nasal discharge, reverse sneezing | Left nasal cavity | Culture PCR | No recurrence 2 mo after topical treatment with 1% miconazole | Italy | 33 |

| Mixed breed | F | 4 y | Chronic fever, vomiting, apathy | Abdominal cavity, peritoneum, mesentery, descending duodenum, caudate liver lobe | PCR | Surgical removal of intestinal and hepatic lesions in combination with itraconazole (5 mg/kg); no recurrence 9 mo follow-up | Germany | 48 |

| Golden Retriever | MC | 8 y | 4-wk history of violent sneezing, licking nasal planum | Right nasal cavity foreign body (grass seed) | Culture PCR | 3-mo treatment with itraconazole (2.5 mg/kg); no recurrence of lesion 8 mo after initial presentation | Australia | 45 |

| Maremmano-Abruzzese Sheepdog | F | 10 mo | Lethargy, lateral decubitus, miosis, muscular rigidity, diarrhea, vomiting, anorexia 36 h before presentation; leukocytosis, neutrophilia. | Mammary gland, kidney, mesentery, lymph nodes | Culture PCR | Dog died shortly after clinical evaluation | Italy | 11 |

| Border Collie | M | 10 y | 2-mo history of stranguria, tenesmus, and weight loss; decreased albumin, increased globulins; 7 y before presentation the patient had intestinal perforation and peritonitis due to NSAID use | Mass adhered to the ventral body of the urinary bladder and abdominal wall and a mesenteric mass | Culture PCR | No recurrence after 6-mo treatment with itraconazole (10 mg/kg) | USA | 51 |

| Irish Terrier | CM | 10 y | 6-mo right-sided nasal discharge; congenital bronchiectasis; lobectomy of right cranial lung lobes; long-term treatment of prednisone (0.1 mg/kg), increased ALP | Right nasal cavity | Culture | 3-mo treatment with itraconazole (2.5 mg/kg), followed by topical treatment with clotrimazole, without surgical debridement; patient’s condition worsened and was euthanized | UK | 36 |

| Pug | NS | NS | Skin wound after a dog fight; the dog swam in a lake after being wounded | Deep skin wound in the right forelimb | Culture PCR | Resolution of lesions after 4-wk treatment with itraconazole and voriconazole (5 mg/kg) | India | 43 |

| Golden Retriever | CM | 6 y | Large abdominal masses; jejunojejunostomy due to foreign body ingestion 2 y before presentation; leukocytosis, increased TP | Abdominal cavity, peritoneum, mesentery | Culture PCR | 45–50% reduction of granuloma size due to 4-mo treatment with voriconazole (5 mg/kg) after surgical removal | Japan | 57 |

| Mixed breed | F | 2 y | 1-wk history of distended abdomen, anemia, lethargy, vomiting, hyporexia; coinfection with Nocardia yamanashiensis, Nocardioides cavernae, and Nocardioides zeicaulis | Abdominal cavity, mesentery, lymph nodes, pancreas, intestinal serosa | Culture PCR | Euthanized due to poor prognosis | USA | Our case |

ALP = alkaline phosphatase; CM = castrated male; F = female; M = male; NS = not specified, OD = right eye; SF = spayed female; TP = total protein.

The diagnosis of scedosporiosis is achieved through culture in combination with molecular testing.11,33,45,51 Because the identification of the fungus based only on morphology is unreliable, ancillary testing using MALDI-TOF MS and DNA sequencing of phylogenetically informative targets such as ITS, CAM, and TUB is recommended for S. apiospermum identification.27,29,57 As found in our case, S. apiospermum colonies are wooly, with gray-brown to gray-white margins, and branching, septate, hyaline hyphae. 57 The reported histologic features align with our findings, with the description of mycetomas containing 3–5-μm wide, non-pigmented, parallel-walled, irregularly branching, septate hyphae with terminal bulbous dilations. 51

In the documented cases of S. apiospermum intra-abdominal infection, the agent was inoculated through penetrating trauma directly into the peritoneal space without inflammatory lesions in the ventral subcutis or abdominal wall. 57 Specifically, the 2 case reports of intra-abdominal infection reported previous intestinal perforation and peritonitis or jejunostomy due to a foreign body as the inciting causes.51,57 In our case, there was no evidence of previous abdominal surgery or traumatic injury; the patient had not been spayed. However, we strongly suspect that penetrating trauma through the abdominal wall is the most likely origin of infection in our case, in the absence of primary enteric disease.

The use of corticosteroids at immunosuppressive doses to treat immune-mediated conditions, including polyarthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, has been identified to increase the risk for opportunistic lymphocutaneous and ocular infection caused by S. apiospermum in dogs.5,38 The patient in our case was not under chronic treatment with immunosuppressive drugs, including corticosteroids, according to the owner. Viral comorbidities were unlikely given that the patient was up-to-date with vaccinations, according to the owner. Histologic findings within the liver and kidneys revealed the extension of the peritoneal inflammation within the capsule, retroperitoneal, and perirenal adipose tissue. Viral inclusions or suppurative infiltrates within the airways were not found. However, the absence of viral inclusions does not rule out a viral coinfection. Ancillary testing for viral infections was not performed in our case and this is a limitation of our study. CBC and serum biochemistry findings reported in canine scedosporiosis are nonspecific and include neutrophilia, hyperglobulinemia, hyperproteinemia, thrombocytopenia, nonregenerative anemia, and increased alkaline phosphatase activity.5,20,32,36,51 Neutrophilia, nonregenerative anemia, and hyperglobulinemia were the clinicopathologic findings reported in our case, due to chronic peritonitis. Leishmania coinfection was documented in a S. apiospermum case of T13-L1 discospondylitis and osteomyelitis in a dog. 20

The coinfection by ubiquitous saprobic and opportunistic infectious agents is infrequent and most likely derived from their inoculation during penetrating trauma. The extension of the lesion and immunologic status of the affected host are determinant factors. Nocardiosis and scedosporiosis are well-documented, rare infections in dogs. However, the presence of Nocardioides bacteria, historically lacking medical relevance, poses a diagnostic challenge. Thus, molecular methods are essential in these cases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Parsons, Lisa Jolly, and Keisha Snerling from the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine (AUCVM) Histology Laboratory for their technical assistance and slide preparation. We thank Stephen Gulley for his technical assistance during the postmortem evaluation.

Footnotes

Eric J. Fish is the owner of EJF Veterinary Consulting. The remaining authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Laura M. Lee  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6105-0317

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6105-0317

Rebecca P. Wilkes  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4846-0439

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4846-0439

Daniel Felipe Barrantes Murillo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0744-3774

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0744-3774

Contributor Information

Jessica Rose Lambert, Departments of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Arthur Colombari Cheng, Departments of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Laura M. Lee, Departments of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA

Donna Raiford, Departments of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Emily Zuber, Departments of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Erin Kilbane, Departments of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Eric J. Fish, EJF Veterinary Consulting, Tampa, FL, USA

Ewa Królak, Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Katelyn C. Hlusko, Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA

Maureen McMichael, Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA.

Rebecca P. Wilkes, Department of Comparative Pathobiology, Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (ADDL), College of Veterinary Medicine, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA

Nathan P. Wiederhold, Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA), San Antonio, TX, USA

Connie F. Cañete-Gibas, Fungus Testing Laboratory, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA), San Antonio, TX, USA

Daniel Felipe Barrantes Murillo, Departments of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA; Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA.

References

- 1. Allison N, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Pseudallescheria boydii in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1989;194:797–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anzalone CL, et al. Nocardia yamanashiensis in an immunocompromised patient presenting as an indurated nodule on the dorsal hand. Tumori 2013;99:156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baszler T, et al. Disseminated pseudallescheriasis in a dog. Vet Pathol 1988;25:95–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown-Elliott BA, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:259–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown JS, et al. Lymphocutaneous infection with Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog on immuno-suppressant therapy. Aust Vet Pract 2009;39:50–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cabañes FJ, et al. Nasal granuloma caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:2755–2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cañete-Gibas CF, et al. Species distribution and antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus section Terrei isolates in clinical samples from the United States and description of Aspergillus pseudoalabamensis sp. nov. Pathogens 2023;12:579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caro-Vadillo A, et al. Fungal rhinitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a labrador retriever. Vet Rec 2005;157:175–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coleman MG, Robson MC. Nasal infection with Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog. N Z Vet J 2005;53:81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cortez KJ, et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008;21:157–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Teodoro G, et al. Disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum infection in a Maremmano-Abruzzese sheepdog. BMC Vet Res 2020;16:372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elad D. Infections caused by fungi of the Scedosporium/Pseudallescheria complex in veterinary species. Vet J 2011;187:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elad D, et al. Disseminated pseudallescheriosis in a dog. Med Mycol 2010;48:635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Erles K, et al. Systemic Scedosporium prolificans infection in an 11-month-old Border collie with cobalamin deficiency secondary to selective cobalamin malabsorption (canine Imerslund-Gräsbeck syndrome). J Small Anim Pract 2018;59:253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fatahi-Bafghi M. Nocardiosis from 1888 to 2017. Microb Pathog 2018;114:369–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gilgado F, et al. Molecular and phenotypic data supporting distinct species statuses for Scedosporium apiospermum and Pseudallescheria boydii and the proposed new species Scedosporium dehoogii. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46:766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guého E, De Hoog GS. Taxonomy of the medical species of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium. J Mycol Med 1991;1:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Han M-X, et al. Nocardioides cavernae sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from a karst cave. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2017;67:633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haynes SM, et al. Disseminated Scedosporium prolificans infection in a German shepherd dog. Aust Vet J 2012;90:34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hugnet C, et al. Osteomyelitis and discospondylitis due to Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest 2009;21:120–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jang SS, Popp JA. Eumycotic mycetoma in a dog caused by Allescheria boydii. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1970;157:1071–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kageyama A, et al. Nocardia inohanensis sp. nov., Nocardia yamanashiensis sp. nov. and Nocardia niigatensis sp. nov., isolated from clinical specimens. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004;54:563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kämpfer P, et al. Nocardioides zeicaulis sp. nov., an endophyte actinobacterium of maize. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2016;66:1869–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klindworth A, et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kochenburger J, et al. Ultrasonography of a ureteral and bladder fungal granuloma caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a basset hound. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2019;60:E6–E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Konsoula A, et al. Lomentospora prolificans: an emerging opportunistic fungal pathogen. Microorganisms 2022;10:1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lackner M, et al. Proposed nomenclature for Pseudallescheria, Scedosporium and related genera. Fungal Divers 2014;67:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lafont E, et al. Invasive nocardiosis: disease presentation, diagnosis and treatment—old questions, new answers? Infect Drug Resist 2020;13:4601–4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lau AF, et al. Development of a clinically comprehensive database and a simple procedure for identification of molds from solid media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol 2013;51:828–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lennon PA, et al. Ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer analysis supports synonomy of Scedosporium inflatum and Lomentospora prolificans. J Clin Microbiol 1994;32:2413–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Malloch D. New concepts in the Microascaceae illustrated by two new species. Mycologia 1970;62:727–740. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marlar AB, et al. Canine keratomycosis: a report of eight cases and literature review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1994;30:331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matteucci G. Rinite micotica da Scedosporium apiospermum in un cane: prima segnalazione in Italia [Mycotic rhinitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog: first report in Italy]. Veterinaria (Cremona) 2017;31:333–337. Italian. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol. 1. Elsevier, 2016:637–639. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mitjà O, et al. Mycetoma caused by Nocardia yamanashiensis, Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012;86:1043–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Natsiopoulos T, et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec Case Rep 2022;10:e438. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nevile JC, et al. Keratomycosis in five dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 2016;19:432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Newton EJW. Scedosporium apiospermum keratomycosis in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2012;15:417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paul AEH, et al. Fungal rhinitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog. Aust Vet Pract 2009;39:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramirez-Garcia A, et al. Scedosporium and Lomentospora: an updated overview of underrated opportunists. Med Mycol 2018;56(Suppl 1):102–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rothacker T, et al. Novel Penicillium species causing disseminated disease in a Labrador Retriever dog. Med Mycol 2020;58:1053–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Salkin IF, et al. Scedosporium inflatum osteomyelitis in a dog. J Clin Microbiol 1992;30:2797–2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singh AD, et al. Scedosporium apiospermum isolated from a skin wound in a dog and in vitro activity of eleven antifungal drugs. Vlaams Diergeneeskd Tijdschr 2022;91:268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smedes SL, et al. Pseudoallescheria boydii keratomycosis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;200:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith CG, et al. Canine rhinitis caused by an uncommonly-diagnosed fungus, Scedosporium apiospermum. Med Mycol Case Rep 2018;22:38–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sykes JE. Chapter 60: Nocardiosis. In: Sykes JE, ed. Greene’s Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 5th ed. Elsevier, 2023:714–722. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Taylor A, et al. Disseminated Scedosporium prolificans infection in a Labrador retriever with immune mediated haemolytic anaemia. Med Mycol Case Rep 2014;6:66–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thiel C, et al. Intraabdominelle Infektion mit zwei Isolaten aus dem Scedosporium apiospermum-Komplex bei einem Hund [Intraabdominal infection with two isolates of the Scedosporium apiospermum complex in a bitch]. Wien Tierarztl Monatsschr 2018;105:13–24. German. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tóth EM, Borsodi AK. The family Nocardioidaceae. In: Rosenberg E, et al., eds. The Prokaryotes: Actinobacteria. 4th ed. Springer, 2014:651–694. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Traxler RM, et al. Updated review on Nocardia species: 2006–2021. Clin Microbiol Rev 2022;35:e0002721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsoi MF, et al. Scedosporium apiospermum infection presenting as a mural urinary bladder mass and focal peritonitis in a Border collie. Med Mycol Case Rep 2021;33:9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tuntivanich P. First report on fungal pneumonia caused by Monosporium apiospermum (Allescheria boydii) in a dog and the effective treatment. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1980;16:269–272. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Verroken A, et al. Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of Nocardia species. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:4015–4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Walker RL, et al. Eumycotic mycetoma caused by Pseudallescheria boydii in the abdominal cavity of a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;192:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Watt PR, et al. Disseminated opportunistic fungal disease in dogs: 10 cases (1982–1990). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995;207:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Whitney J, Barrs V. Actinomycosis, nocardiosis, and mycobacterial infections. In: Bruyette DS, ed. Clinical Small Animal Internal Medicine. 1st ed. Vol. 2. Wiley, 2020:977–984. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yoshimura A, et al. Multiple intra-abdominal fungal granulomas caused by Scedosporium apiospermum effectively treated with voriconazole in a Golden retriever. Med Mycol Case Rep 2023;42:100611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]