Abstract

Background and Aims

Somatic mutations in the TET2 gene that lead to clonal haematopoiesis (CH) are associated with accelerated atherosclerosis development in mice and a higher risk of atherosclerotic disease in humans. Mechanistically, these observations have been linked to exacerbated vascular inflammation. This study aimed to evaluate whether colchicine, a widely available and inexpensive anti-inflammatory drug, prevents the accelerated atherosclerosis associated with TET2-mutant CH.

Methods

In mice, TET2-mutant CH was modelled using bone marrow transplantations in atherosclerosis-prone Ldlr−/− mice. Haematopoietic chimeras carrying initially 10% Tet2−/− haematopoietic cells were fed a high-cholesterol diet and treated with colchicine or placebo. In humans, whole-exome sequencing data and clinical data from 37 181 participants in the Mass General Brigham Biobank and 437 236 participants in the UK Biobank were analysed to examine the potential modifying effect of colchicine prescription on the relationship between CH and myocardial infarction.

Results

Colchicine prevented accelerated atherosclerosis development in the mouse model of TET2-mutant CH, in parallel with suppression of interleukin-1β overproduction in conditions of TET2 loss of function. In humans, patients who were prescribed colchicine had attenuated associations between TET2 mutations and myocardial infarction. This interaction was not observed for other mutated genes.

Conclusions

These results highlight the potential value of colchicine to mitigate the higher cardiovascular risk of carriers of somatic TET2 mutations in blood cells. These observations set the basis for the development of clinical trials that evaluate the efficacy of precision medicine approaches tailored to the effects of specific mutations linked to CH.

Keywords: CHIP, Inflammation, TET2, Atherosclerosis, Precision medicine, Colchicine

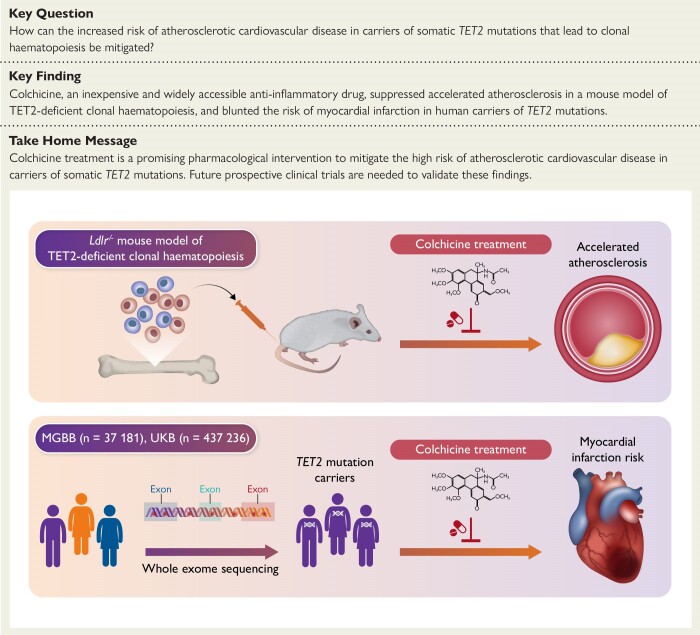

Structured Graphical Abstract

Structured Graphical Abstract.

Clonal haematopoiesis (CH) driven by somatic mutations in the TET2 gene has been associated with heightened inflammation and an increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. In mice, we found that colchicine treatment prevented the development of accelerated atherosclerosis in a mouse model of TET2-deficient CH. In humans, analyses of sequencing data from two large biobanks showed that patients who were prescribed colchicine had attenuated associations between TET2-mutant CH and myocardial infarction. MGBB, Mass General Brigham Biobank; UKB, UK Biobank.

Introduction

Clonal haematopoiesis (CH) driven by acquired mutations has emerged as a new and independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) that may pave the way for new personalized preventive care strategies.1,2 Clonal haematopoiesis is a condition whereby an acquired somatic mutation provides a selective advantage to the haematopoietic stem cell carrying it, leading to its progressive clonal expansion and the propagation of the mutation among the progeny of haematopoietic stem cells, including immune cells. When CH is driven by single nucleotide variants or small insertions/deletions in known haematological malignancy-related genes, such as DNMT3A, TET2 or ASXL1, and more than 4% of cells harbour the mutation, the condition is frequently referred to as CH of indeterminate potential (CHIP). Analysis of whole-exome/genome sequencing datasets has revealed that more than 10% of individuals older than 65 years have CHIP.3,4

Genetic analyses and experiments in mice suggest that carrying certain CHIP mutations is associated with a higher risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD and other cardiovascular conditions.1,2,5–11TET2, which encodes for an epigenetic regulator of gene transcription, is among the most frequently mutated genes in CHIP,3,4 and loss-of-function mutations in this gene have been associated with a ∼two-fold higher risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) and peripheral artery disease.5,6,8 Additionally, biallelic or monoallelic inactivation of Tet2 in mice leads to accelerated atherosclerosis development.6,7 Mechanistically, this phenotype is mainly driven by the pro-inflammatory actions of TET2-mutant cells, characterized predominantly by an upregulation of the cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β, a major contributor to vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis.6,7,12–14

The accumulating evidence linking somatic TET2 mutations to inflammation and atherosclerotic CVD, together with the increasing knowledge about the mechanisms underlying this connection, has led to a great interest in developing personalized preventive care approaches tailored to the pro-inflammatory effects of these mutations. However, demonstrably efficacious therapies remain unavailable. Here, we provide evidence from mouse and human studies suggesting that the higher risk of atherosclerotic disease associated with somatic TET2 mutations can be specifically ameliorated by treatment with colchicine, a widely available and inexpensive anti-inflammatory drug derived from the plant extract of Colchicum autumnale, which showed promise in previous clinical trials for the prevention of atherosclerotic CVD.15–17

Methods

Mice

All mice were maintained on a 12-h light/dark schedule in a specific pathogen-free animal facility in individually ventilated cages and given food and water ad libitum. C57Bl/6J Tet2−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Ldlr−/− mice carrying the CD45.1 isoform of the CD45 haematopoietic antigen were generated at CNIC by crossing C57Bl/6J Ldlr−/− mice from the Jackson Laboratory and B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyCrl mice from Charles River Laboratories.

Experimental studies in mice

The murine experimental design is summarized in Figure 1A and detailed in Supplementary data online, Figure S1. Clonal haematopoiesis was modelled in mice through competitive bone marrow transplantations (BMT) in female low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-deficient mice (Ldlr−/−) as in our earlier studies (see Supplementary Methods).7,12 CD45.1+ Ldlr−/− recipients were transplanted with suspensions of bone marrow (BM) cells containing 10% CD45.2+ Tet2−/− cells and 90% CD45.1+ Tet2+/+ cells (TET2-KO CH mice) or 10% CD45.2+ Tet2+/+ cells and 90% CD45.1+ Tet2+/+ cells (wild-type controls, WT). Starting 4 weeks after BMT, mice were fed a high-cholesterol Western diet (ENVIGO, TD.88137, Adjusted Calories Diet; 42% from fat, 0.2% cholesterol) to promote hypercholesterolaemia and atherosclerosis development. Mice were maintained on a Western diet for 8 weeks, while receiving daily subcutaneous injections of either colchicine (Sigma) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) vehicle as placebo, from Monday to Friday. Colchicine dosage was gradually increased to avoid toxicity, starting with 0.05 mg/kg/day for the first week, and transitioning to 0.1 mg/kg/day for the second week, and 0.2 mg/kg/day for the remaining 6 weeks.

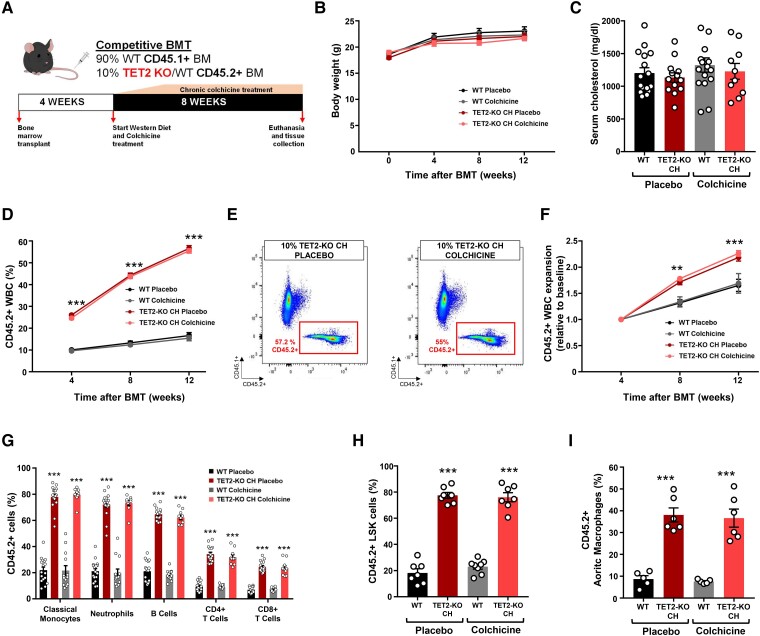

Figure 1.

A mouse model of TET2-mutant clonal haematopoiesis and chronic colchicine treatment. (A) Summary of experimental design. (B) Mouse body weight throughout the duration of the experiment. (C) Serum cholesterol levels at endpoint. (D) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the white blood cell population at multiple timepoints, evaluated by flow cytometry. (E) Representative dot plots of the endpoint flow cytometry analysis of CD45.2+ white blood cells in TET2-KO clonal haematopoiesis mice treated with colchicine or placebo. (F) Expansion of CD45.2+ white blood cells relative to baseline chimerism. (G) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the main white blood cell populations in peripheral blood 12 weeks after the bone marrow transplantations, determined by flow cytometry. (H) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in the bone marrow lineage-Sca1 + cKit + cell population at endpoint, determined by flow cytometry. (I) Percentage of CD45.2+ cells in aortic macrophages at endpoint, determined by flow cytometry (n = 5–6 pools of two aortae per genotype, as shown in the figure). All results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 17 placebo-treated WT mice; n = 16 placebo-treated TET2-KO clonal haematopoiesis mice; n = 13 colchicine-treated WT mice; n = 10 colchicine-treated TET2-KO clonal haematopoiesis mice unless otherwise indicated). Statistical significance was evaluated by repeated measures two-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests in (D) and (F) and two-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s multiple comparison tests in (G), (H), and (I) (**P < .01, ***P < .001 for the comparison to each corresponding WT control). The error bars indicate SEM

Quantification of aortic atherosclerosis burden in mice

Mice were euthanized, and aortas were removed after in situ perfusion with PBS through the left ventricle of the heart. Tissue fixation was achieved by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight at 4°C. Aortic tissue was then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Histological sections comprising the aortic root were cut at a thickness of 4 μm. An operator who was blinded to genotype quantified plaque size in aortic root sections by computer-assisted morphometric analysis of microscopy images. For each mouse, atherosclerotic plaque size in aortic root cross sections was calculated as the average of five independent sections separated by ∼16 µm. Atherosclerotic plaque composition was examined by histological and immunohistochemical techniques. Vascular smooth muscle cells were identified with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated mouse anti-smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) monoclonal antibody (clone 1A4,Sigma) and Vector Red Alkaline Phosphatase Substrate (Vector Laboratories). Macrophages were detected with a rat anti-Mac2 monoclonal antibody (Cedarlane Laboratories), a biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibody, streptavidin-HRP, and DAB substrate (all from Vector Laboratories), with haematoxylin counterstaining. Collagen content and necrotic core extension were determined in histological sections after a modified Masson’s trichrome staining. Conventional microscopy images were analysed using Fiji software and the colour deconvolution plugin. Additional information on the characterization of atherosclerotic plaques is given in Supplementary Methods. Plasma cholesterol levels were determined using an enzymatic assay (Enzymatic-Colorimetric Cholesterol Kit, Insulab).

Flow cytometry analyses

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry were used to investigate the expansion of TET2-deficient cells among different lineages in BM, aorta, and blood, as in our earlier work.7 In brief, ascending aorta and aortic arches were digested for 45 min at 37°C in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% foetal bovine serum and 0.25 mg/mL Liberase TM (Roche Life Science). Blood was obtained from the facial vein. Bone marrow cells were flushed out from one femur per mouse. Samples were stained with combinations of biotinylated and/or fluorescently labelled antibodies (see Supplementary Methods) in PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 30 min on ice. Dead cells were excluded from analysis by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining in unfixed samples. Data were acquired in a BD FACSymphony cytometer (BD Bioscience) and analysed with FlowJo software. Gating strategies can be found in our previous publications.7,8,12

Cell culture studies

Thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were obtained as previously described.7,12 Pro-inflammatory activation of macrophages was achieved by treatment with 10 ng/mL bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS, InvivoGen) and 2 ng/mL interferon-γ (IFN-γ, Sigma) for 4 h. For NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion, LPS/IFN-γ-primed macrophages were treated with 5 mM adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) (Sigma) for 25 min. Macrophages were treated with colchicine (1 µM) or vehicle, as indicated in figures and figure legends. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was used to evaluate transcript expression of IL-1β and IL-6. 36B4 and β-actin were used as reference genes for normalization. IL-1β secretion by cultured macrophages was quantified using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems). Western blot analyses of IL-1β levels in cell culture supernatants were performed as previously described7,12 using a rabbit polyclonal anti-IL-1β antibody (GeneTex).

Statistical analysis of data in experimental studies

Data are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests in experiments with one independent variable and by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s or Sidak’s multiple comparison tests in experiments with more than one independent variable. All statistical tests were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Human study participants

We used data from the Mass General Brigham Biobank (MGBB) and the UK Biobank (UKB). The MGBB is an ongoing hospital-based cohort study of patients across the Mass General Brigham system. It is enriched with longitudinal electronic medical record (EMR), genomic, and health and lifestyle data.18 We analysed data from 37 181 unrelated MGBB participants, all over 40 years of age and free from leukaemia, with blood-based whole-exome sequencing (WES) data. Relatedness was defined as third-degree relatives identified using the kinship coefficients derived from the Kinship-based Inference for Genome-wide association studies (KING) tool.19 We restricted the study population to MGBB participants older than 40 years to be consistent with the age range of the UKB. All participants provided written, informed consent per the MGBB primary protocol. The UKB is a prospective cohort consisting of ∼500 000 adult participants aged 40–69 years who were recruited between 2006 and 2010 from 22 assessment centres across the UK. Our analysis of the UKB included 437 236 unrelated individuals with blood-based WES data who were leukaemia-free and myocardial infarction (MI)-free at baseline. Details about filtering invalid genotype data can be found elsewhere,20 and relatedness was defined as in the MGBB.

Ascertainment of human study outcomes

Disease outcomes were derived based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) ICD-9/ICD-10 codes from EMRs in the MGBB, and by a combination of self-report, inpatient hospital billing ICD codes and death registries in the UKB. We selected a hard outcome, MI, as the primary atherosclerotic CVD outcome to reduce the potential inaccuracy in using billing codes for ascertaining disease status (see Supplementary data online, Tables S1 and S2). In sensitivity analyses, we evaluated five additional CVD-related outcomes: heart failure, CAD, ischaemic stroke, all-cause mortality, and a composite CVD outcome (defined as any combination of CAD, MI, ischaemic stroke, and all-cause mortality). Additional details on the definitions of these outcomes are given in Supplementary data online, Tables S1 and S2 for both the MGBB and UKB. Biomarker data from complete blood count and lipid panels used in the MGBB were also extracted from EMRs. Blood sample collections and biomarker measurements were performed following the clinical standards at each participating hospital in the MGBB system.18

Identification of CHIP mutations

Blood WES datasets from MGBB and UKB participants and a previously reported pipeline4 were used to identify putative CHIP mutations in a predefined list of genes (see Supplementary data online, Table S3). CHIP was defined as variant allele fraction (VAF) ≥2%. Additional details are given in Supplementary Methods.

Assessment of human study covariates

In the MGBB, demographic information, lifestyle factors, medication use, and comorbidities were curated from EMRs. Patients were defined as colchicine users if they were prescribed this medication anywhere in the medical record. As gout is the primary indication for colchicine and type 2 diabetes has well-established separate associations with CHIP and MI,12,21,22 we adjusted for these two diseases as covariates in our models. The ICD codes used for defining gout and type 2 diabetes are listed in Supplementary data online, Table S1.

In the UKB, participants provided sociodemographic, health, behaviour, and medical history information through baseline questionnaires and interviews conducted by nurses. This served as the source for demographic information, lifestyle factors, and medication usage, with the exception of colchicine. To ensure a comprehensive capture of colchicine usage, we augmented self-reported data with prescription records from the UKB Primary Care database. Participants were classified as colchicine users if they reported usage at baseline or if there was a record of colchicine prescription. Similar to the MGBB, we adjusted for gout and type 2 diabetes in our models using self-reported information and diagnostic codes specified in Supplementary data online, Table S2 to define these conditions.

Statistical analysis of human data

We evaluated the associations between CHIP mutations and MI, and their modification by colchicine prescription status, in the MGBB and UKB. Given the nature of the MGBB as a tertiary hospital-based population, where patients typically present with pre-existing conditions, we employed a cross-sectional analytical design. In contrast, the UKB, characterized by its prospective cohort design, consists predominantly of participants who were healthy at baseline and accrued various conditions during the follow-up of the study. Hence, we utilized survival analysis to evaluate associations in the UKB. In addition to TET2, we examined the two other most frequently mutated CHIP driver genes, DNMT3A and ASXL1, as well as overall CHIP, defined as carrying somatic mutations on any CHIP driver genes, for comparison.

In MGBB analyses, using logistic regression, we first estimated the odd ratios (ORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the relationship between CHIP mutations and MI (prevalent or incident). Then, we performed stratified analyses by examining the associations among colchicine users and non-users separately and tested the interactions between colchicine and CHIP mutations on MI. Models were adjusted for age at the time of sequencing, sex, white race, current smoking status, type 2 diabetes status, gout status, batches, and the first 10 principal components of genetic ancestry. For the tested interactions between colchicine and CHIP mutations, we evaluated their associations with haematopoietic and circulating lipid traits using linear regression models with adjusting for the same sets of covariates. All haematological and lipid traits were log-transformed, standardized to zero mean and unit variance, and approximately normally distributed in the population.

In UKB analyses, we used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and associated 95% CIs of the relationship between CHIP mutations and the incidence of MI over ∼14 years of follow-up. Then, we performed stratified analyses by colchicine use status within this prospective context. Participants with prevalent cases of MI at enrolment were excluded. Statistical models were adjusted for the same covariates as in the MGBB. In parallel with the MGBB, we performed sensitivity analyses examining the associations of CHIP variables with incidences of other cardiovascular outcomes. Analyses used R version 4.0.0 software. Two-tailed P < .05 indicates statistical significance.

Results

Development of an atherosclerosis-prone mouse model of chronic colchicine treatment and TET2-mutant clonal haematopoiesis

To mimic TET2-mutant CHIP, we used a competitive BMT approach in atherosclerosis-prone Ldlr−/− mice, generating haematopoietic chimeras carrying initially 10% Tet2 −/− haematopoietic cells (TET2-KO CH mice), as in our previous work.7 To distinguish Tet2−/− and Tet2+/+ haematopoietic cells in chimeric mice, Tet2+/+ donor cells were obtained from mice carrying the CD45.1 variant of the CD45 cell surface marker, whereas Tet2−/− cells were obtained from mice carrying the CD45.2 variant of this marker. Control mice (WT) were transplanted with 10% CD45.2+ Tet2+/+ cells and 90% CD45.1+ Tet2+/+ cells. Transplanted mice were fed a high-cholesterol Western diet for 8 weeks to induce hypercholesterolaemia and atherosclerosis, while being treated with progressively increasing doses of colchicine, up to 0.2 mg/Kg/day, or PBS as placebo (Figure 1A, Supplementary data online, Figure S1). Neither BM genotype nor colchicine treatment affected body weight (Figure 1B) or circulating cholesterol levels (Figure 1C). Tet2−/− cells expanded among the different white blood cell lineages, to a comparable extent in mice treated with colchicine or placebo (Figure 1D–G and Supplementary data online, Figure S2A). A similar expansion was observed in the population of BM haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (LSK cells, defined as lineage-cKit + Sca1+), which was also unaffected by colchicine treatment (Figure 1H). Circulating white blood cell counts were similar in the different experimental groups (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2B). TET2-deficient cells were also enriched among macrophages within the aortic wall, regardless of colchicine treatment (Figure 1I).

Colchicine prevents the accelerated development of atherosclerosis associated with TET2-mutant clonal haematopoiesis in mice

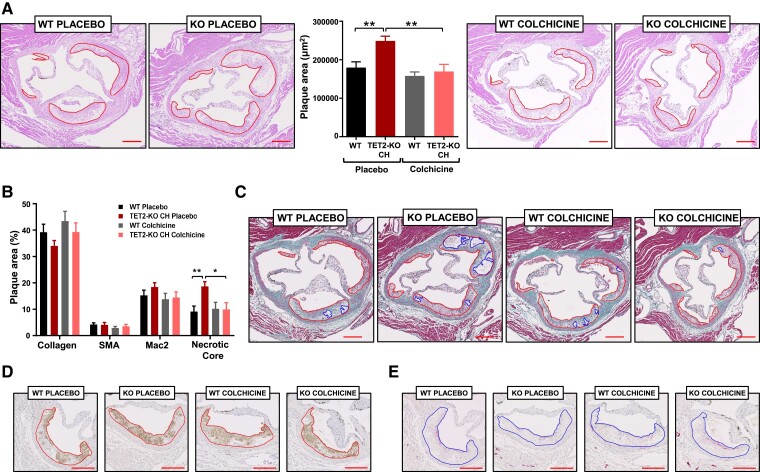

Having characterized our experimental model of TET2-mutant CHIP and chronic colchicine treatment, we next evaluated the size and characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic root. Consistent with our previous findings,6,7 plaque size was significantly increased in chimeric TET2-KO CH mice compared with WT controls in the placebo group (Figure 2A). Colchicine treatment prevented this effect, suppressing the differences in plaque size between both BM genotypes (Figure 2A). Colchicine had a clear atheroprotective effect in TET2-KO CH mice, decreasing plaque size by ∼27% (P = .003), whereas it had no impact on atherosclerosis development in WT controls (P = .693; Pinteraction = .049). The lack of effect of colchicine in LDLR-KO controls contrasts with recent studies in apoE-KO mice,23,24 which probably reflects differences in the inflammatory milieu in these mouse models of atherosclerosis. Similar seemingly conflicting findings have been observed for other anti-inflammatory interventions.7,25–27 The extension of plaque necrotic cores was greater in TET2-KO CH mice than in the WT group, which was also prevented by colchicine treatment (Figure 2B and C). No significant differences were observed in the content of other plaque components, such as macrophages, vascular smooth muscle cells, or collagen (Figure 2B–E). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the proportion of proliferating or apoptotic cells in atherosclerotic plaques (see Supplementary data online, Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Colchicine prevents the effects of TET2-mutant clonal haematopoiesis on experimental atherosclerosis in mice. (A) Aortic root plaque size in the different experimental groups. Representative images of haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections are shown; atherosclerotic plaques are delineated. (B) Histological analysis of plaque composition, quantified as percentage macrophage content (Mac2 antigen immunostaining), vascular smooth muscle cell content (smooth muscle α-actin immunostaining), collagen content (Masson’s trichrome staining), and necrotic core (collagen-free acellular regions in Masson’s trichrome-stained sections). (C) Representative images of Masson’s trichrome-stained sections; atherosclerotic plaques and necrotic areas are delineated. (D) Representative images of Mac2 antigen immunostaining. (E) Representative images of smooth muscle α-actin immunostaining. All results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 17 placebo-treated WT mice; n = 16 placebo-treated TET2-KO clonal haematopoiesis mice; n = 13 colchicine-treated WT mice; n = 10 colchicine-treated TET2-KO clonal haematopoiesis mice). Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests (*P < .05, **P < .01). The error bars indicate SEM

Colchicine suppresses interleukin-1β overproduction in conditions of TET2-mutant clonal haematopoiesis

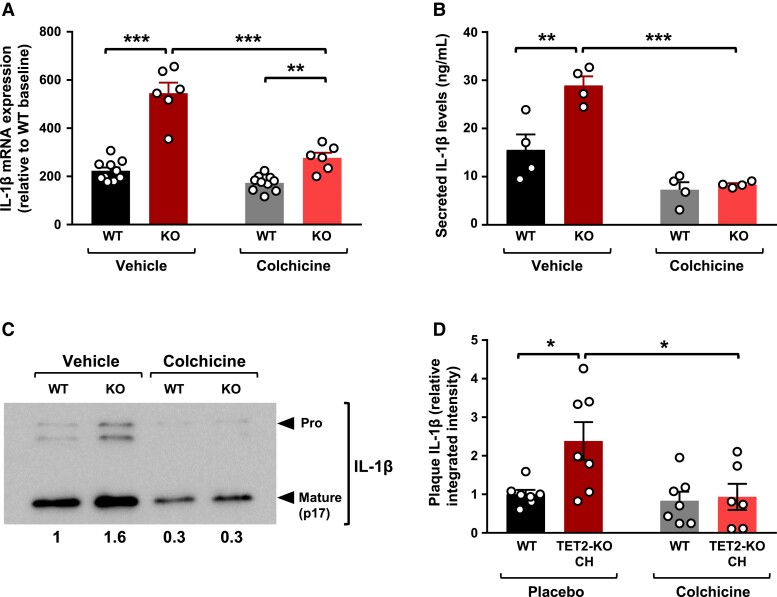

We and others have previously shown that accelerated atherosclerosis in conditions of TET2-KO CH is related to the overproduction by TET2-mutant macrophages of IL-1β, a potent pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic cytokine.6,7,28 On this basis, we evaluated whether colchicine modulates the effect of TET2 deficiency on IL-1β production. We first examined the effects of colchicine on IL-1β transcript levels in TET2-KO peritoneal macrophages and WT controls undergoing pro-inflammatory activation induced by treatment with bacterial LPS and IFN-γ. Consistent with previous findings,7,12 qPCR analyses revealed higher IL-1β transcript levels in TET2-KO macrophages than in WT controls (Figure 3A). Colchicine treatment led to a significant reduction in IL-1β transcript levels, and this inhibitory effect was ∼three-fold greater in TET2-deficient macrophages than in WT controls (48% decrease vs. 16% decrease, respectively, P = .005). Accordingly, colchicine treatment resulted in a marked attenuation of the increased expression of IL-1β in TET2-deficient macrophages compared with WT controls (1.6-fold change in the presence of colchicine; 2.4-fold change in the presence of placebo vehicle, Figure 3A). In contrast, the inhibitory effect of colchicine on the transcript levels of IL-6, another pro-inflammatory cytokine upregulated in TET2-KO macrophages compared with WT controls, was similar in both genotypes (∼70% relative reduction of IL-6 transcript levels, regardless of TET2 genotype, Supplementary data online, Figure S4). Consequently, despite a substantial decrease in absolute IL-6 transcript levels, the relative increase in the expression of IL-6 observed in TET2-KO macrophages remained unaltered by colchicine treatment (∼3.5-fold higher mRNA levels in TET2-KO macrophages, regardless of colchicine treatment, Supplementary data online, Figure S4).

Figure 3.

Colchicine inhibits elevated interleukin-1β production in conditions of TET2-mutant clonal haematopoiesis. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of interleukin-1β transcript expression in peritoneal macrophages isolated from Tet2−/− or +/+ mice (n = 10 WT, 6 KO, from two independent experiments) and stimulated for 4 h with 10 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide and 2 ng/mL interferon-γ in the presence of 1 μM colchicine or phosphate-buffered saline vehicle. mRNA levels are shown relative to the WT untreated group. (B) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis of interleukin-1β protein levels in the supernatant of Tet2−/− and Tet2+/+ peritoneal macrophages (n = 4 mice) stimulated for 4 h with 10 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide and 2 ng/mL interferon-γ in the presence of 1 μM colchicine or phosphate-buffered saline vehicle, combined with a final 25 min incubation with 5 mM adenosine 5′-triphosphate. (C) Representative western blot analysis of pro-interleukin-1β and mature interleukin-1β protein levels in the culture supernatant of Tet2−/− and Tet2+/+ peritoneal macrophages. Numbers indicate mature interleukin-1β levels relative to vehicle-treated WT macrophages. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of interleukin-1β protein levels in aortic root plaques of the different in vivo experimental groups (n = 7 mice per group), quantified as relative integrated fluorescence intensity normalized to plaque area. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). The error bars indicate SEM

Next, we examined the effects of colchicine on IL-1β secretion after LPS/IFN-γ priming and treatment with ATP to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, a macromolecular complex that catalyses IL-1β proteolytic processing and secretion. Consistent with previous work,7,12,28 ELISA analyses of cell culture supernatants revealed that the secreted levels of IL-1β levels were 1.9-fold higher in TET2-KO macrophages than in WT controls (Figure 3B). Similar to previous reports,23,29,30 colchicine treatment led to a significant reduction in IL-1β secretion, assessed by ELISA (Figure 3B). However, this inhibitory effect of colchicine was >1.3-fold greater in TET2-deficient macrophages than in WT controls (71% decrease vs. 53% decrease, P = .049). Overall, colchicine treatment completely suppressed the increased secretion of IL-1β in TET2-deficient macrophages compared with WT controls (Figure 3B). This observation was confirmed by western blot analysis of the levels of the mature cleaved form of IL-1β in cell culture supernatants (Figure 3C).

Consistent with our findings in cell culture experiments, immunostaining and confocal microscopy analyses demonstrated that colchicine suppresses the increased IL-1β protein levels observed in atherosclerotic plaques of TET2-KO CH mice (Figure 3D).

Baseline characteristics of the human study populations

Among the 37 181 unrelated leukaemia-free patients over 40 years old in the MGBB who underwent exome sequencing, the mean (SD) age at sequencing was 61.7 (11.3) years, and 17 800 (47.9%) were men. We identified 5171 (13.9%) individuals with CHIP mutations, of whom 1168 (22.6%) had mutations in TET2, 2443 (47.2%) in DNMT3A, and 457 (8.8%) in ASXL1. A total of 2479 participants were prescribed colchicine. Colchicine users were, on average, older, more likely to be male, more likely to have gout, type 2 diabetes and other conditions, and more likely to be using other medications, when compared with non-users (Table 1). The prevalence of CHIP was higher among patients who were prescribed colchicine. The variant allelic fraction (VAF) of DNMT3A mutations was slightly higher in colchicine users, whereas there was no difference in the VAF of TET2 and ASXL1 mutations between colchicine users and non-users (Table 1). The characteristics of patients with specific mutated genes or overall CHIP, stratified by colchicine treatment status, are shown in Supplementary data online, Tables S4–S7.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population according to colchicine use in the Mass General Brigham Biobank (n = 37 181)

| Metrica | Non-colchicine users (N = 34 702) |

Colchicine users (N = 2479) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at sequencing (years) | 61.4 (11.3) | 65.3 (11.1) | <.01c |

| Male | 16 098 (46.4) | 1702 (68.7) | <.01c |

| White race | 30 674 (88.4) | 2148 (86.6) | .01c |

| Current smokers | 946 (2.7) | 58 (2.3) | .28c |

| BMI | 31.5 (7.3) | 34.8 (8.1) | <.01c |

| Gout | 1749 (5.0) | 1709 (68.9) | <.01c |

| Type 2 diabetes | 8201 (23.6) | 1153 (46.5) | <.01c |

| Cancer | 8681 (25.0) | 658 (26.5) | .09c |

| Hypertension | 11 026 (31.8) | 1365 (55.1) | <.01c |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5748 (16.6) | 1280 (51.6) | <.01c |

| Family history of CVD | 16 019 (46.2) | 968 (39.0) | <.01c |

| Prescription of aspirin | 6936 (20.1) | 962 (39.1) | <.01c |

| Prescription of insulin | 1933 (5.6) | 357 (14.5) | <.01c |

| Prescription of DMARD | 4087 (11.8) | 459 (18.5) | <.01c |

| Prescription of lipid-lowering medication | 21 512 (62.0) | 2128 (85.8) | <.01c |

| CHIP | 4737 (13.7) | 434 (17.5) | <.01c |

| TET2 | 1054 (3.0) | 114 (4.6) | <.01c |

| VAFb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.14 (0.13) | 0.12 (0.12) | .12c |

| Median (IQR) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.18) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.14) | .14d |

| DNMT3A | 2281 (6.6) | 162 (6.5) | .97c |

| VAFb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.14 (0.10) | 0.16 (0.11) | .02c |

| Median (IQR) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.17) | 0.12 (0.07, 0.20) | .02d |

| ASXL1 | 408 (1.2) | 49 (2.0) | <.01c |

| VAFb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.12) | .80c |

| Median (IQR) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.22) | 0.10 (0.06, 0.22) | .75d |

| Disease outcome | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 1800 (5.2) | 414 (16.7) | <.01c |

| Coronary artery disease | 4465 (12.9) | 868 (35.0) | <.01c |

| Ischaemic stroke | 1208 (3.5) | 175 (7.1) | <.01c |

| Haematopoietic and lipid traits | |||

| HCT | 44.3 (3.8) | 45.9 (4.1) | <.01c |

| MCV | 94.9 (6.4) | 97.2 (7.2) | <.01c |

| RDW | 15.5 (3.1) | 17.1 (3.5) | <.01c |

| MCHC | 35.1 (1.2) | 35.6 (1.1) | <.01c |

| PLT | 355.5 (143.5) | 399.0 (166.0) | <.01c |

| RBC | 4.9 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.5) | <.01c |

| WBC | 13.7 (7.3) | 16.7 (8.1) | <.01c |

| HGB | 14.8 (1.4) | 15.4 (1.4) | <.01c |

| Cholesterol | 226.7 (53.1) | 231.7 (57.3) | <.01c |

| Triglycerides | 221.4 (239.6) | 310.2 (275.2) | <.01c |

| HDL cholesterol | 69.1 (22.5) | 63.7 (20.9) | <.01c |

| LDL cholesterol | 138.5 (45.5) | 142.0 (44.0) | <.01c |

The study population includes unrelated patients who do not have leukaemia, are older than 40 years, and have blood-based whole-exome sequencing data; relatedness is defined as third-degree relatives identified using kinship coefficients.

CHIP, clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential; DMARD, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HCT, haematocrit; HGB, haemoglobin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; RDW, red cell distribution width; VAF, variant allele fraction; WBC, white blood cell.

aMetrics are represented as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and % (n) for categorical variables unless otherwise specified.

bVAF was only limited to participants with corresponding CHIP mutations.

c P-values were calculated by t-test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables.

d P-values were calculated by the Mann–Whitney U test without assuming that the continuous variables follow normal distributions.

In the UKB, among 437 236 unrelated individuals free of leukaemia and MI at baseline, the mean (SD) age at sequencing was 56.5 (8.1) years, and 199 518 (45.6%) were men. A total of 29 684 participants (6.8%) were found to have CHIP mutations. Of them, 5713 (19.2%) had mutations in TET2, 16 461 (55.5%) in DNMT3A, and 2830 (9.5%) in ASXL1. Colchicine was used by, or prescribed to, 3849 participants. Similar to the MGBB, colchicine users in the UKB were typically older and more predominantly male. They also exhibited a higher prevalence of gout, type 2 diabetes, other conditions, and medication use compared with non-users (Table 2). The characteristics of UKB participants with specific mutated genes or overall CHIP, stratified by colchicine treatment status, are shown in Supplementary data online, Tables S8–S11.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population in the UK Biobank (n = 437 236)

| Metrica | Non-colchicine users (N = 433 387) |

Colchicine users (N = 3849) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at sequencing (years) | 56.5 (8.1) | 59.9 (7.1) | <.01b |

| Male | 196 426 (45.3) | 3092 (80.3) | <.01b |

| White British ancestry | 362 961 (83.7) | 3294 (85.6) | .01b |

| Ever smokers | 194 101 (44.8) | 2204 (57.3) | .28b |

| BMI | 27.4 (4.7) | 30.2 (4.9) | <.01 |

| Gout | 5961 (1.4) | 994 (25.8) | <.01b |

| Type 2 diabetes | 10 184 (2.3) | 245 (6.4) | <.01b |

| Cancer | 39 442 (9.1) | 362 (9.4) | .53b |

| Hypertension | 124 961 (28.8) | 2262 (58.8) | <.01b |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1293 (0.3) | 95 (2.5) | <.01b |

| Family history of CVD | 157 388 (43.5) | 1569 (47.8) | <.01b |

| CHIP | 29 341 (6.8) | 343 (8.9) | <.01b |

| TET2 | 5632 (1.3) | 81 (2.1) | <.01b |

| DNMT3A | 16 294 (3.8) | 167 (4.3) | .07b |

| ASXL1 | 2790 (0.6) | 40 (1.0) | <.01b |

| Disease outcome | |||

| Incident myocardial infarction | 13 453 (3.1) | 298 (7.7) | <.01b |

The study population includes unrelated individuals who do not have myocardial infarction or leukaemia at baseline and have blood-based whole-exome sequencing data; relatedness is defined as third-degree relatives identified using kinship coefficients.

CHIP, clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential.

aMetrics are represented as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and % (n) for categorical variables unless otherwise specified.

b P-values were calculated by t-test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables.

Colchicine blunts the effect of TET2-mutant clonal haematopoiesis on myocardial infarction in humans

In MGBB analyses, adjusted for potential confounders in the present dataset, carrying TET2, ASXL1, or overall CHIP was significantly associated with higher odds of the composite CVD outcome at P = .05 level, although carrying mutations in any of the three examined CHIP genes was not significantly associated with MI odds in the present dataset. The ORs of the cross-sectional associations of TET2, DNMT3A, and ASXL1-mutant CHIP, or overall CHIP, with the composite CVD outcome were 1.14 (95% CI: 1.00–1.31, P = .05), 1.06 (95% CI: 0.96–1.17, P = .28), 1.51 (95% CI: 1.23–1.86, P = 8.5E−05), and 1.14 (95% CI: 1.06–1.22, P = 5.0E−04), respectively (see Supplementary data online, Table S12), and the associations of TET2, DNMT3A, and ASXL1-mutant CHIP and overall CHIP with MI were 1.15 (95% CI: 0.92–1.42, P = .21), 0.90 (95% CI: 0.75–1.07, P = .24), 1.12 (95% CI: 0.80–1.55, P = .52), and 1.06 (95% CI: 0.94–1.20, P = .35), respectively (see Supplementary data online, Table S13). In the UKB, consistent with previous reports,20 survival analysis revealed significant associations between all examined CHIP variables and incidence of the composite CVD outcome over an average follow-up of 13.1 (SD: 2.5) years (see Supplementary data online, Table S14), as well as of ASXL1 mutations and overall CHIP with MI incidence over an average follow-up of 13.3 (SD: 2.3) years (see Supplementary data online, Table S15).

When stratifying by colchicine use, we observed blunting of the effect of TET2-mutant CHIP on MI by colchicine in both the cross-sectional analysis of MGBB and the survival analysis of the UKB, consistent with our murine findings. In MGBB, the relationship between TET2-mutant CHIP and MI was significantly modified by colchicine use [ORcolchicine (95% CI): 0.76 (0.43–1.34); ORno colchicine (95% CI): 1.23 (0.98–1.56); Pinteraction = .04]. In contrast, the modification effect of colchicine on MI risk was not observed for DNMT3A or ASXL1-mutant CHIP (Table 3). Stratifying the associations between colchicine and MI by CHIP mutations yielded consistent modification effects (see Supplementary data online, Table S16). The modification effect by colchicine was also observed for the relationship between CAD and TET2 mutations, but not with other CHIP mutations (see Supplementary data online, Table S17). Adjusting for medication or additional comorbidities did not change substantially the modification effect of colchicine (see Supplementary data online, Tables S18 and S19). Similar to our findings in the MGBB, in the UKB, colchicine modified the relationship between TET2-mutant CHIP and the incidence of MI [HRcolchicine (95% CI): 0.30 (0.08–1.22); HRno colchicine (95% CI): 1.08 (0.95–1.24); Pinteraction = .05], and no such modification effect was seen with DNMT3A or ASXL1-mutant CHIP (Table 4). Additional sensitivity analyses showed findings similar to those of the MGBB (see Supplementary data online, Tables S20–S22). However, we did not observe any significant modification effects of colchicine on the relationship between TET2-mutant CHIP and haematopoietic or lipid traits (Table 5), consistent with our murine findings.

Table 3.

Differential association of clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and myocardial infarction by colchicine prescription status in the Mass General Brigham Biobank (n = 37 181)

| OR (95% CI) | P interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHIP | Colchicine | 0.99 (0.74, 1.33) | .06 |

| No colchicine | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) | ||

| TET2 | Colchicine | 0.76 (0.43, 1.34) | .04 |

| No colchicine | 1.23 (0.98, 1.56) | ||

| DNMT3A | Colchicine | 0.82 (0.53, 1.29) | .32 |

| No colchicine | 0.92 (0.76, 1.11) | ||

| ASXL1 | Colchicine | 1.58 (0.79, 3.19) | .73 |

| No colchicine | 1.03 (0.71, 1.51) |

Logistic regression models adjusted for age at the time of sequencing, sex, White race, current smoking status (yes/no), type 2 diabetes status, gout status, batches (111/112/113), and the first 10 principal components of genetic ancestry. The study population was restricted to unrelated patients in the Mass General Brigham Biobank who do not have leukaemia, are older than 40 years, and have blood-based whole-exome sequencing data; relatedness is defined as third-degree relatives identified using the kinship coefficients.

CHIP, clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential; OR: odds ratio.

Table 4.

Differential association of clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and incident myocardial infarction by colchicine prescription status in the UK Biobank (n = 437 236)

| HR (95% CI) | P interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CHIP | Colchicine | 0.72 (0.46, 1.12) | .03 |

| No colchicine | 1.09 (1.02, 1.16) | ||

| TET2 | Colchicine | 0.30 (0.08, 1.22) | .05 |

| No colchicine | 1.08 (0.95, 1.24) | ||

| DNMT3A | Colchicine | 0.62 (0.32, 1.22) | .12 |

| No colchicine | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) | ||

| ASXL1 | Colchicine | 0.59 (0.15, 2.39) | .22 |

| No colchicine | 1.32 (1.13, 1.55) |

Cox proportional model adjusted for age at the time of sequencing, sex, White British ancestry, ever smoking status (yes/no), type 2 diabetes status at baseline, gout status at baseline, and the first 10 principal components of genetic ancestry. The study population was restricted to unrelated participants in the UK Biobank who do not have diagnoses of leukaemia or myocardial infarction at baseline; relatedness is defined as third-degree relatives identified using kinship coefficients.

CHIP, clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential; HR: hazard ratio.

Table 5.

Cross-sectional associations between clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential mutation and haematopoietic and lipid traits stratified by colchicine status among Mass General Brigham Biobank participants

| HCT (n = 17 649) |

MCH (n = 17 655) |

RDW (n = 17 654) |

MCHC (n = 17 655) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | ||

| CHIP | Colchicine | −0.16 (−0.31, −0.02) | .49 | 0.05 (−0.25, 0.35) | .71 | 0.25 (0.11, 0.40) | .17 | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.13) | .86 |

| No colchicine | −0.13 (−0.17, −0.09) | 0.00 (−0.10, 0.09) | 0.15 (0.11, 0.19) | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.01) | |||||

| TET2 | Colchicine | −0.25 (−0.51, 0.00) | .22 | −0.47 (−1.00, 0.05) | .13 | 0.12 (−0.13, 0.37) | .81 | 0.09 (−0.14, 0.33) | .27 |

| No colchicine | −0.11 (−0.19, −0.03) | −0.07 (−0.25, 0.12) | 0.09 (0.00, 0.17) | −0.06 (−0.14, 0.02) | |||||

| DNMT3A | Colchicine | −0.01 (−0.23, 0.21) | .84 | −0.10 (−0.55, 0.36) | .65 | 0.11 (−0.11, 0.33) | .28 | −0.01 (−0.21, 0.20) | .76 |

| No colchicine | −0.06 (−0.12, 0.00) | 0.05 (−0.08, 0.19) | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.06) | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.08) | |||||

| ASXL1 | Colchicine | −0.23 (−0.60, 0.14) | .97 | −0.51 (−1.28, 0.25) | .66 | 0.25 (−0.12, 0.61) | .14 | −0.01 (−0.35, 0.34) | .53 |

| No colchicine | −0.17 (−0.29, −0.05) | −0.30 (−0.57, −0.02) | 0.44 (0.32, 0.56) | −0.08 (−0.20, 0.04) | |||||

| PLT (n = 17 654) |

RBC (n = 17 655) |

WBC (n = 17 655) |

HGB (n = 17 655) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | ||

| CHIP | Colchicine | 0.06 (−0.07, 0.20) | .30 | −0.16 (−0.31, −0.01) | .52 | −0.06 (−0.19, 0.07) | .04 | −0.15 (−0.30, −0.01) | .56 |

| No colchicine | 0.00 (−0.04, 0.04) | −0.12 (−0.17, −0.08) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.13) | −0.12 (−0.17, −0.08) | |||||

| TET2 | Colchicine | 0.05 (−0.19, 0.29) | 0.71 | −0.08 (−0.34, 0.18) | 0.89 | −0.19 (−0.41, 0.03) | 0.11 | −0.21 (−0.46, 0.04) | 0.40 |

| No colchicine | 0.01 (−0.07, 0.09) | −0.10 (−0.18, −0.02) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) | −0.11 (−0.19, −0.03) | |||||

| DNMT3A | Colchicine | −0.01 (−0.22, 0.20) | 0.75 | 0.01 (−0.22, 0.23) | .74 | −0.08 (−0.27, 0.11) | .09 | −0.01 (−0.23, 0.21) | .91 |

| No colchicine | 0.01 (−0.04, 0.07) | −0.06 (−0.12, 0.00) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15) | −0.05 (−0.10, 0.01) | |||||

| ASXL1 | Colchicine | 0.17 (−0.18, 0.52) | .32 | −0.08 (−0.46, 0.29) | 0.62 | −0.04 (−0.37, 0.28) | 0.69 | −0.21 (−0.58, 0.15) | 0.84 |

| No colchicine | 0.01 (−0.11, 0.13) | −0.11 (−0.23, 0.01) | 0.02 (−0.10, 0.14) | −0.18 (−0.30, −0.06) | |||||

| Cholesterol (n = 23 401) |

Triglyceride (n = 23 564) |

HDL cholesterol (n = 23 343) |

LDL cholesterol (n = 15 372) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | Beta (95% CI) | P interaction | ||

| CHIP | Colchicine | −0.11 (−0.23, 0.01) | .36 | −0.07 (−0.18, 0.05) | .002 | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.06) | .45 | −0.16 (−0.30, −0.02) | .11 |

| No colchicine | −0.07 (−0.10, −0.03) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.07) | −0.06 (−0.09, −0.02) | −0.06 (−0.10, −0.01) | |||||

| TET2 | Colchicine | −0.08 (−0.29, 0.14) | .91 | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.17) | .09 | 0.05 (−0.16, 0.25) | .08 | −0.20 (−0.45, 0.05) | .34 |

| No colchicine | −0.07 (−0.14, 0.00) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.15) | −0.11 (−0.18, −0.04) | −0.09 (−0.18, 0.00) | |||||

| DNMT3A | Colchicine | 0.01 (−0.17, 0.18) | 0.94 | −0.07 (−0.24, 0.11) | 0.16 | 0.03 (−0.14, 0.20) | 0.81 | −0.01 (−0.22, 0.20) | 0.84 |

| No colchicine | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.06, 0.04) | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.09) | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.07) | |||||

| ASXL1 | Colchicine | 0.06 (−0.25, 0.38) | .34 | −0.03 (−0.35, 0.28) | .58 | −0.09 (−0.40, 0.21) | .69 | −0.09 (−0.46, 0.27) | .75 |

| No colchicine | −0.11 (−0.22, 0.01) | −0.06 (−0.18, 0.07) | −0.09 (−0.21, 0.02) | −0.04 (−0.18, 0.09) | |||||

The study population was restricted to unrelated patients in the Mass General Brigham Biobank who do not have leukaemia, are older than 40 years, have blood-based whole-exome sequencing data, and have available biomarker measurements close to blood draw for sequencing.

CHIP, clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HCT, haematocrit; HGB, haemoglobin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PLT, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; RDW, red cell distribution width; WBC, white blood cell.

Discussion

Our study combining experiments in mice and genetic analyses in humans provides evidence suggesting that colchicine treatment can mitigate the increased risk of atherosclerotic CVD associated with CH driven by somatic TET2 mutations (Structured Graphical Abstract). These results provide important new insights that should help translate our growing knowledge of CHIP into personalized strategies for the management of CVD risk in carriers of somatic TET2 mutations.

The identification of colchicine as an effective means to prevent accelerated atherosclerosis in conditions of TET2-mutant CHIP paves the way for the development and application of precision medicine approaches guided by sequencing CHIP genes, specifically TET2. It also provides the prospect of a widely available low-cost therapeutic option. Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential has emerged as a new CVD risk factor, and several institutions have created specialized clinics for counselling patients with CH-related mutations.31–33 Furthermore, patients with established atherosclerotic CVD and TET2 mutations have significant residual risk of recurrent events.34 However, CHIP screening is not yet recommended in the context of CVD, as there is a lack of evidence-based interventions to prevent the heightened CVD risk associated with carrying these mutations. Previous experiments in mice and analyses of human specimens linked TET2-mutant CHIP to exacerbated inflammatory responses, mainly driven by an overproduction of IL-1β,6,7 which provided rationale for the clinical exploration of IL-1β as a target for the prevention of the increased CVD risk associated with somatic TET2 mutations.35 Supporting this possibility, an exploratory post hoc analysis of the CANTOS randomized clinical trial showed that high-risk patients with CVD with haematopoietic TET2 mutations exhibited greater protective response to treatment with canakinumab—an IL-1β-neutralizing antibody—than those without CHIP mutations.36 However, the use of canakinumab as a precision strategy to prevent CVD in TET2 mutation carriers faces likely insurmountable challenges, considering its high cost37 and the rejection by regulatory agencies of applications to extend its use for the secondary prevention of atherosclerotic CVD.38,39 In contrast, colchicine may provide a more feasible anti-inflammatory approach in this setting, as (i) it is widely available and inexpensive and (ii) it is already recommended by European and Latin American guidelines for the prevention of CVD in selected, high-risk patients with atherosclerosis,40,41 and has been approved for this purpose by North American regulatory agencies.42,43 Colchicine has broader anti-inflammatory effects than direct IL-1β blockade with canakinumab, but it is known to inhibit IL-1β/NLRP3-driven inflammation,29,30 the primary mechanism driving atherosclerosis development in experimental models of TET2-mutant CHIP.6,7,28 Accordingly, our experiments in mice and cultured macrophages show that colchicine suppresses the overproduction of IL-1β in conditions of TET2 loss of function. However, we cannot rule out that additional anti-inflammatory actions of colchicine23,24,44–46 also contribute to its atheroprotective effects in this context. Although there may be shared pro-atherogenic mechanisms among mutations in different CHIP genes, the link to IL-1β/NLRP3-driven inflammation is notably robust for TET2 mutations,4,6,7,12–14,28,36,47,48 which may explain the results of our human studies, wherein colchicine modifies specifically the effect of TET2 mutations, and not that of other mutated genes. Consistent with this observation, several CHIP mutations not affecting TET2 seem to modulate inflammatory responses and atherosclerosis at least in part through mechanisms not known to be targeted by colchicine, such as impaired apoptotic cell uptake49 or exacerbated macrophage proliferation.8

Our results may also facilitate the use of colchicine for atherosclerotic CVD prevention by providing a specific clinical niche for this drug in the context of precision medicine. Several prospective randomized placebo-controlled trials, totalling over 10 000 patients with coronary heart disease, have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits of colchicine in a wide range of patients with atherosclerosis.15–17 However, similar to other anti-inflammatory approaches, the broad use of colchicine may not be justified, given the potential side effects of chronic suppression of inflammation. Indeed, colchicine-treated patients exhibited a numerically greater incidence of non-cardiovascular death in clinical trials, albeit without a clear pattern or evident mechanism.15 In this context, the benefit/risk ratio of colchicine could be improved by using it selectively in individuals predicted to get a particular benefit from treatment with this anti-inflammatory drug, such as TET2 mutation carriers. Although further research is required, these selective benefits of colchicine could be extensive to other cardiovascular conditions, beyond atherosclerosis, that have been linked to TET2-mutant CHIP in earlier studies, such as heart failure development and progression.48,50–52

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting these findings. First, the regime of colchicine treatment in our mouse experiments is difficult to extrapolate to the clinical scenario, with most clinical trials using a dose regimen of 0.5 mg colchicine administered orally once daily. However, the dose of colchicine used in our experiments is lower than that used in most previous studies in mouse models of CVD,24,53–56 which supports the potent effects of colchicine in the setting of TET2-mutant CHIP. Second, experimental atherosclerosis studies were conducted exclusively in female mice, so we cannot rule out the possibility of sex-related differences on the effects of TET2 mutations or colchicine. However, it must be noted that the effects of TET2 mutations on atherosclerosis have been independently demonstrated in both male57 and female mice6,7 in prior studies. Third, our analysis of the MGBB population used data from EMRs, where ascertainment of disease was based on the billing codes, which may not always be able to capture the true underlying condition and exact starting time of disease. To overcome this limitation, we used a hard outcome, MI, as the atherosclerotic cardiovascular outcome and examined its cross-sectional association with CHIP in this population. Fourth, as pharmacy data were unavailable in both the MGBB and UKB, and to maximize power, we stratified by colchicine ever-prescription (or any prior exposure to colchicine). This may have attenuated the effect of colchicine on the association between CHIP and MI in our study, as many patients were likely treated with colchicine for short periods of time, in contrast to clinical trials during which colchicine is administered longer term.15–17 Fifth, the allocation of colchicine in humans in both the MGBB and UKB was non-random and, while known confounders were considered, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding introduced by the clinical heterogeneity of patients and additional factors. However, the interaction observed for TET2-mutant CHIP and colchicine was not observed for other genes and was highly consistent in two human populations and in mice, supporting the reliability of our findings.

Conclusions

In summary, the current study highlights the potential of colchicine as a personalized preventive care strategy to mitigate the increased cardiovascular risk of TET2 mutation carriers, on top of the current standard of care. Future prospective clinical trials are needed to validate these findings. In the meantime, our results provide preliminary evidence and a strong first step to pursue such financially demanding endeavours. Overall, this research illustrates how a deep understanding of the effects of the different somatic mutations linked to CH may facilitate the development of genomically informed precision medicine approaches against atherosclerotic CVD.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal online.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

María A Zuriaga, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Zhi Yu, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, 75 Ames St., Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center and Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, CPZN 3.184, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Nuria Matesanz, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Buu Truong, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, 75 Ames St., Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center and Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, CPZN 3.184, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Beatriz L Ramos-Neble, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Mari C Asensio-López, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain; Cardiology Department, Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, IMIB-Arrixaca and University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain.

Md Mesbah Uddin, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, 75 Ames St., Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center and Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, CPZN 3.184, Boston, MA 02114, USA.

Tetsushi Nakao, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, 75 Ames St., Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center and Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, CPZN 3.184, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Abhishek Niroula, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Medical Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Institute of Biomedicine, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; SciLifeLab, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; Cancer Program, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Virginia Zorita, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Marta Amorós-Pérez, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Rosa Moro, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Benjamin L Ebert, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Michael C Honigberg, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, 75 Ames St., Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center and Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, CPZN 3.184, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Domingo Pascual-Figal, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain; Cardiology Department, Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, IMIB-Arrixaca and University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain; CIBER en Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBER-CV), Madrid, Spain.

Pradeep Natarajan, Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, 75 Ames St., Cambridge, MA 02142, USA; Cardiovascular Research Center and Center for Genomic Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, CPZN 3.184, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, 25 Shattuck St., Boston, MA 02115, USA.

José J Fuster, Program on Novel Mechanisms of Atherosclerosis, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3, 28029 Madrid, Spain; CIBER en Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBER-CV), Madrid, Spain.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

P.N. reported research grants from Allelica, Amgen, Apple, Boston Scientific, Genentech/Roche and Novartis, personal fees from Allelica, Apple, AstraZeneca, Blackstone Life Sciences, Creative Education Concepts, CRISPR Therapeutics, Eli Lilly & Co, Esperion Therapeutics, Foresite Capital, Foresite Labs, Genentech / Roche, GV, HeartFlow, Magnet Biomedicine, Merck, Novartis, TenSixteen Bio, and Tourmaline Bio, equity in Bolt, Candela, Mercury, MyOme, Parameter Health, Preciseli and TenSixteen Bio, and spousal employment at Vertex Pharmaceuticals, all unrelated to the present work. M.C.H. reported advisory board service for Miga Health, consulting fees from Comanche Biopharma, and research support from Genentech. B.L.E. received research funding from Novartis and Calico and consulting fees from AbbVie and is a member of the scientific advisory board and shareholder for Neomorph Inc., TenSixteen Bio, Skyhawk Therapeutics, and Exo Therapeutics. Other authors reported no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Data Availability

Individual-level MGBB data are available from https://personalizedmedicine.partners.org/Biobank/Default.aspx, only to Mass General Brigham investigators with appropriate approval from the institutional review board. Individual-level UKB data are available to approved researchers via the UK Biobank Access Management System (https://ams.ukbiobank.ac.uk/ams/). Other data that support the findings of this study are available on request to the corresponding authors.

Funding

Z.Y. was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (K99HG012956). T.N. was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K99HL165024). M.C.H. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08HL166687) and the American Heart Association (940166, 979465). B.L.R.-N. was supported by grant PRE2019-087829, funded by the MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ESF Investing in your future. M.A.-P. was supported by grant FPU18/02913, funded by the MICIU. M.C.A.-L. was supported by grant FJC2020-042841-I, funded by the MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR. P.N. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL148050) and the Leducq Foundation (TNE-18CVD04). J.J.F. was supported by grant RYC-2016-20026, funded by the MICIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ESF Investing in your future; grant PLEC2021-008194, funded by the MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR; grant PID2021-126580OB-I00, funded by the MICIU/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and by the ERDF/EU; and grant 202314-31, funded by the Fundació ‘La Marató de TV3’ and the Leducq Foundation (TNE-18CVD04). The project leading to these results also received funding from the ‘la Caixa’ Foundation under the project codes LCF/PR/HR17/52150007 and LCF/PR/HR22/52420011. The CNIC is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MICIU), and the Pro CNIC Foundation and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (grant CEX2020-001041-S funded by the MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033).

Ethical Approval

Animal experiments followed protocols approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) and conformed to EU Directive 86/609/EEC and Recommendation 2007/526/EC regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, enforced in Spanish law under Real Decreto 1201/2005. The secondary use of human data was approved by the Massachusetts General Brigham Institutional Review Board (protocol 2020P000904).

Pre-registered Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Tall AR, Fuster JJ. Clonal hematopoiesis in cardiovascular disease and therapeutic implications. Nat Cardiovasc Res 2022;1:116–24. 10.1038/s44161-021-00015-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Natarajan P. Genomic aging, clonal hematopoiesis, and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2023;43:3–14. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.318181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kessler MD, Damask A, O'Keeffe S, Banerjee N, Li D, Watanabe K, et al. Common and rare variant associations with clonal haematopoiesis phenotypes. Nature 2022;612:301–9. 10.1038/s41586-022-05448-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bick AG, Weinstock JS, Nandakumar SK, Fulco CP, Bao EL, Zekavat SM, et al. Inherited causes of clonal haematopoiesis in 97,691 whole genomes. Nature 2020;586:763–8. 10.1038/s41586-020-2819-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2488–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:111–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA, Polackal MN, Ostriker AC, Chakraborty R, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science 2017;355:842–7. 10.1126/science.aag1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zekavat SM, Viana-Huete V, Matesanz N, Jorshery SD, Zuriaga MA, Uddin MM, et al. TP53-mediated clonal hematopoiesis confers increased risk for incident atherosclerotic disease. Nat Cardiovasc Res 2023;2:144–58. 10.1038/s44161-022-00206-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fidler TP, Xue C, Yalcinkaya M, Hardaway B, Abramowicz S, Xiao T, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome exacerbates atherosclerosis in clonal haematopoiesis. Nature 2021;592:296–301. 10.1038/s41586-021-03341-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu B, Roberts MB, Raffield LM, Zekavat SM, Nguyen NQH, Biggs ML, et al. Supplemental association of clonal hematopoiesis with incident heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:42–52. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bick AG, Pirruccello JP, Griffin GK, Gupta N, Gabriel S, Saleheen D, et al. Genetic interleukin 6 signaling deficiency attenuates cardiovascular risk in clonal hematopoiesis. Circulation 2020;141:124–31. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fuster JJ, Zuriaga MA, Zorita V, MacLauchlan S, Polackal MN, Viana-Huete V, et al. TET2-loss-of-function-driven clonal hematopoiesis exacerbates experimental insulin resistance in aging and obesity. Cell Rep 2020;33:108326. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abplanalp WT, Mas-Peiro S, Cremer S, John D, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Association of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential with inflammatory gene expression in patients with severe degenerative aortic valve stenosis or chronic postischemic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:1170–5. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Libby P. Interleukin-1 Beta as a target for atherosclerosis therapy: biological basis of CANTOS and beyond. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2278–89. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fiolet ATL, Opstal TSJ, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Jolly SS, Keech AC, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine in patients with coronary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2021;42:2765–75. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Schut A, Opstal TSJ, et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1838–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2497–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1912388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karlson EW, Boutin NT, Hoffnagle AG, Allen NL. Building the Partners HealthCare Biobank at partners personalized medicine: informed consent, return of research results, recruitment lessons and operational considerations. J Pers Med 2016;6:2. 10.3390/jpm6010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Manichaikul A, Mychaleckyj JC, Rich SS, Daly K, Sale M, Chen WM. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 2010;26:2867–73. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yu Z, Fidler TP, Ruan Y, Vlasschaert C, Nakao T, Uddin MM, et al. Genetic modification of inflammation- and clonal hematopoiesis-associated cardiovascular risk. J Clin Invest 2023;133:e168597. 10.1172/JCI168597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tobias DK, Manning AK, Wessel J, Raghavan S, Westerman KE, Bick AG, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) and incident type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care 2023;46:1978–85. 10.2337/dc23-0805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Joseph JJ, Deedwania P, Acharya T, Aguilar D, Bhatt DL, Chyun DA, et al. Comprehensive management of cardiovascular risk factors for adults with type 2 diabetes: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022;145:e722–59. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwarz N, Fernando S, Chen YC, Salagaras T, Rao SR, Liyanage S, et al. Colchicine exerts anti-atherosclerotic and -plaque-stabilizing effects targeting foam cell formation. FASEB J 2023;37:e22846. 10.1096/fj.202201469R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meyer-Lindemann U, Mauersberger C, Schmidt AC, Moggio A, Hinterdobler J, Li X, et al. Colchicine impacts leukocyte trafficking in atherosclerosis and reduces vascular inflammation. Front Immunol 2022;13:898690. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.898690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zeng W, Wu D, Sun Y, Suo Y, Yu Q, Zeng M, et al. The selective NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 hinders atherosclerosis development by attenuating inflammation and pyroptosis in macrophages. Sci Rep 2021;11:19305. 10.1038/s41598-021-98437-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Westerterp M, Fotakis P, Ouimet M, Bochem AE, Zhang H, Molusky MM, et al. Cholesterol efflux pathways suppress inflammasome activation, NETosis, and atherogenesis. Circulation 2018;138:898–912. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van der Heijden T, Kritikou E, Venema W, van Duijn J, van Santbrink PJ, Slutter B, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition by MCC950 reduces atherosclerotic lesion development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:1457–61. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yalcinkaya M, Liu W, Thomas LA, Olszewska M, Xiao T, Abramowicz S, et al. BRCC3-mediated NLRP3 deubiquitylation promotes inflammasome activation and atherosclerosis in Tet2 clonal hematopoiesis. Circulation 2023;148:1764–77. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 2006;440:237–41. 10.1038/nature04516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, Lee H, Zou J, Saitoh T, et al. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 2013;14:454–60. 10.1038/ni.2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sidlow R, Lin AE, Gupta D, Bolton KL, Steensma DP, Levine RL, et al. The clinical challenge of clonal hematopoiesis, a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:958–61. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bolton KL, Zehir A, Ptashkin RN, Patel M, Gupta D, Sidlow R, et al. The clinical management of clonal hematopoiesis: creation of a clonal hematopoiesis clinic. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2020;34:357–67. 10.1016/j.hoc.2019.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steensma DP, Bolton KL. What to tell your patient with clonal hematopoiesis and why: insights from 2 specialized clinics. Blood 2020;136:1623–31. 10.1182/blood.2019004291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gumuser ED, Schuermans A, Cho SMJ, Sporn ZA, Uddin MM, Paruchuri K, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential predicts adverse outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1996–2009. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.03.401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Viana-Huete V, Fuster JJ. Potential therapeutic value of interleukin 1b-targeted strategies in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2019;72:760–6. 10.1016/j.recesp.2019.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Svensson EC, Madar A, Campbell CD, He Y, Sultan M, Healey ML, et al. TET2-driven clonal hematopoiesis and response to canakinumab: an exploratory analysis of the CANTOS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:521–8. 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sehested TSG, Bjerre J, Ku S, Chang A, Jahansouz A, Owens DK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of canakinumab for prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:128–35. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1MS2QX. (8 May 2024, date last accessed).

- 39. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/canakinumab-novartis. (8 May 2024, date last accessed).

- 40. Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Back M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3227–337. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ponte-Negretti CI, Wyss FS, Piskorz D, Santos RD, Villar R, Lorenzatti A, et al. Latin American Consensus on management of residual cardiometabolic risk. A consensus paper prepared by the Latin American Academy for the Study of Lipids and Cardiometabolic Risk (ALALIP) endorsed by the Inter-American Society of Cardiology (IASC), the International Atherosclerosis Society (IAS), and the Pan-American College of Endothelium (PACE). Arch Cardiol Mex 2022;92:99–112. 10.24875/ACM.21000005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/215727s000lbl.pdf (8 May 2024, date last accessed).

- 43. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info?lang=eng&code=100936 (8 May 2024, date last accessed).

- 44. Cronstein BN, Molad Y, Reibman J, Balakhane E, Levin RI, Weissmann G. Colchicine alters the quantitative and qualitative display of selectins on endothelial cells and neutrophils. J Clin Invest 1995;96:994–1002. 10.1172/JCI118147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kuijpers TW, Raleigh M, Kavanagh T, Janssen H, Calafat J, Roos D, et al. Cytokine-activated endothelial cells internalize E-selectin into a lysosomal compartment of vesiculotubular shape. A tubulin-driven process. J Immunol 1994;152:5060–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.152.10.5060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weng JH, Koch PD, Luan HH, Tu HC, Shimada K, Ngan I, et al. Colchicine acts selectively in the liver to induce hepatokines that inhibit myeloid cell activation. Nat Metab 2021;3:513–22. 10.1038/s42255-021-00366-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shin TH, Zhou Y, Chen S, Cordes S, Grice MZ, Fan X, et al. A macaque clonal hematopoiesis model demonstrates expansion of TET2-disrupted clones and utility for testing interventions. Blood 2022;140:1774–89. 10.1182/blood.2021014875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, MacLauchlan S, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, et al. Tet2-mediated clonal hematopoiesis accelerates heart failure through a mechanism involving the IL-1beta/NLRP3 inflammasome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:875–86. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ampomah PB, Cai B, Sukka SR, Gerlach BD, Yurdagul A Jr, Wang X, et al. Macrophages use apoptotic cell-derived methionine and DNMT3A during efferocytosis to promote tissue resolution. Nat Metab 2022;4:444–57. 10.1038/s42255-022-00551-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pascual-Figal DA, Bayes-Genis A, Diez-Diez M, Hernandez-Vicente A, Vazquez-Andres D, de la Barrera J, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of progression of heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1747–59. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Assmus B, Cremer S, Kirschbaum K, Culmann D, Kiefer K, Dorsheimer L, et al. Clonal haematopoiesis in chronic ischaemic heart failure: prognostic role of clone size for DNMT3A- and TET2-driver gene mutations. Eur Heart J 2021;42:257–65. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dorsheimer L, Assmus B, Rasper T, Ortmann CA, Ecke A, Abou-El-Ardat K, et al. Association of mutations contributing to clonal hematopoiesis with prognosis in chronic ischemic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:25–33. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Akodad M, Fauconnier J, Sicard P, Huet F, Blandel F, Bourret A, et al. Interest of colchicine in the treatment of acute myocardial infarct responsible for heart failure in a mouse model. Int J Cardiol 2017;240:347–53. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.03.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mori H, Taki J, Wakabayashi H, Hiromasa T, Inaki A, Ogawa K, et al. Colchicine treatment early after infarction attenuates myocardial inflammatory response demonstrated by (14)C-methionine imaging and subsequent ventricular remodeling by quantitative gated SPECT. Ann Nucl Med 2021;35:253–9. 10.1007/s12149-020-01559-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huang C, Cen C, Wang C, Zhan H, Ding X. Synergistic effects of colchicine combined with atorvastatin in rats with hyperlipidemia. Lipids Health Dis 2014;13:67. 10.1186/1476-511X-13-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tsutsui H, Ishibashi Y, Takahashi M, Namba T, Tagawa H, Imanaka-Yoshida K, et al. Chronic colchicine administration attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1999;31:1203–13. 10.1006/jmcc.1999.0953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]