Abstract

The photothermal sensitivity of tobacco refers to the degree to which tobacco responds to changes in light and temperature conditions in its growth environment, which is crucial for determining the planting area of cultivars and improving tobacco yield and quality. In order to accurately and effectively evaluate the photothermal sensitivity of tobacco cultivars, this study selected five cultivars and their hybrid combinations with significant differences planted under different ecological conditions from 2021 to 2022 as materials. The experiment was conducted in two locations with significant differences in temperature and light. We measured the agronomic traits and biomass of the experimental materials, and constructed an effective tobacco photothermal sensitivity evaluation model using principal component analysis, membership function, and regression analysis. The reliability of the model was evaluated by utilizing the photosynthetic characteristics, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant enzyme system activity of the experimental materials. The results showed that tobacco biomass is the most important principal component in agricultural traits, and the comprehensive evaluation model for tobacco photothermal sensitivity is: y = 0.4571y1 + 0.2406y2 + 0.1725y3, where the fitting coefficients R2 of y1, y2, and y3 are 0.945, 0.851, and 0.977, respectively; The photothermal sensitivity of the experimental materials was calculated using this model, and the comprehensive ranking of the 11 experimental materials is: G3 < G5 < G10 < G9 < G11 < G6 < G7 < G2 < G4 < G8 < G1. Conventional identification methods have found that G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, and G11 are sensitive materials, G3, G5, and G10 are insensitive materials, and G1 and G9 are intermediate materials. The consistency rate of the evaluation results of the two methods reached 90.91%. And there is a significant correlation between the agronomic traits selected in the model and the physiological indicators selected by conventional evaluation methods, providing a scientific basis for evaluating the light temperature sensitivity of tobacco cultivars using agronomic traits in this study. The results indicate that the photothermal sensitivity evaluation model established in this study provides an efficient, convenient, and reliable method for evaluating the photothermal sensitivity of tobacco.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-78877-3.

Keywords: Tobacco, Photothermal sensitivity, Principal component analysis, Agronomic traits, Model

Subject terms: Genetics, Plant sciences

Introduction

Light and temperature are important environmental factors for plant growth and development, profoundly affecting plant growth and morphogenesis1. Plants can also adapt to new environments by adjusting their own developmental processes2,3.The photothermal sensitivity of plants refers to the degree to which they respond to changes in light and temperature conditions in their growth environment, which determines the range of their environmental adaptability4. The adaptability is particularly important in the context of climate change, where shifting environmental conditions demand greater resilience from plant species5,6. It is generally believed that crops that are sensitive to light and temperature have a narrower range of adaptation, while those that are insensitive to light and temperature have a wider range7. In addition to genetic characteristics, the photothermal sensitivity of plants is closely related to the light and temperature conditions of their growing environment8,9. Different plants have different sensitivity indicators to light and temperature, and the evaluation methods for photothermal sensitivity of different plants are also different10,11. There is currently no report on the assessment of tobacco photothermal sensitivity.

Identifying the photothermal sensitivity of crops serves as a critical foundation for the strategic exploration, utilization, and selection of germplasm resources with broad adaptability. This process enables the enhancement of breeding programs and the optimization of crop cultivars tailored to diverse environmental conditions12,13. Previous studies have shown on different crops14–16 that the intensity of light and temperature seriously affect the agronomic traits, growth cycle, and even yield of plants. Based on this, some studies17–20 facilitate the use of differences in single crop indicators, such as the length of the growth cycle, the content of chemical components, or the amount of yield, to evaluate the sensitivity of crops to light and temperature. However, recent studies have highlighted the limitations of using a single evaluation indicator, as it may be highly susceptible to environmental fluctuations, making it challenging to accurately and objectively assess the quality of germplasm resources21,22. A more robust approach involves a comprehensive analysis of photothermal sensitivity through multiple indicators. In the research of rapeseed23 and wheat24, researchers conveniently used multiple indicators to evaluate the comprehensive traits of germplasm resources such as quality, yield, and resistance, providing a theoretical basis for early screening of excellent crop cultivars.

With the development of biotechnology, people have begun to identify the photothermal sensitivity of crops by measuring their physiological and biochemical indicators. Yadav25 and Bao26 used chlorophyll content and antioxidant enzyme activity to evaluate the photothermal sensitivity of crops. Dong27 and Khanzada28 evaluated the photothermal sensitivity of wheat leaves by utilizing indicators such as pigment content, photosynthetic capacity, antioxidant enzyme system, and yield components under different light and temperature conditions. Racz29 focused on the differences in antioxidant systems and photosynthetic parameters, and evaluated the photothermal sensitivity of different bell peppers cultivars. In summary, various indicators such as photosynthetic characteristic parameters, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant system enzyme activity have been widely used to identify the photothermal sensitivity of crops.

Nicotiana tobacco L. has very strict requirements for light and temperature30–33.By appropriately increasing temperature and light intensity, or prolonging light duration, the plant height34, stem width35, and leaf length36 of the tobacco are significantly increased. However, when temperature and light intensity decrease and light duration is shortened, the stem width, leaf number, and leaf length of the tobacco are significantly reduced, thereby affecting the biomass of the tobacco37–39.Therefore, different light and temperature conditions have a serious impact on the agronomic traits and even biomass of tobacco plants. Tobacco is an important economic crop in the western region of China, and the stereo climatic40 conditions in the western tobacco growing area is obvious, with significant differences in ecological conditions such as light and temperature within the region. Therefore, this study planted different tobacco cultivars (lines) under different light and temperature conditions from 2021 to 2022. We measured the agronomic traits of different experimental materials, selected important indicators through principal component analysis, calculated their membership function values, and established a comprehensive evaluation model for photothermal sensitivity based on tobacco agronomic traits through stepwise regression; Physiological indicators related to photothermal sensitivity, such as photosynthetic characteristics, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant enzyme activity, were measured to verify the accuracy of the model’s calculation results. The establishment of this model can improve the efficiency of tobacco photothermal sensitivity, and the identification results obtained have scientific significance and application value for the selection and utilization of photothermal insensitive tobacco cultivars.

Materials and methods

Overview of the experimental area

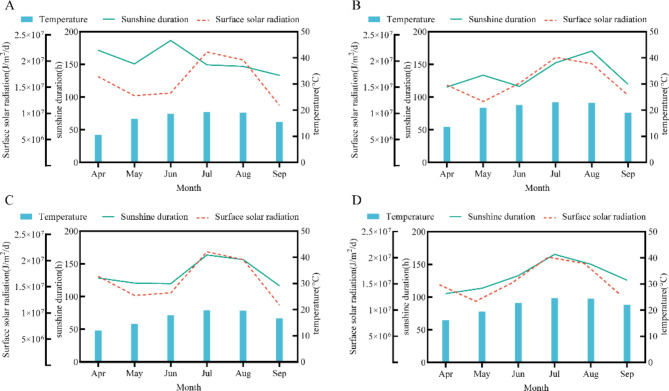

The field experiment was conducted at the tobacco base in Heishitou Town, Weining County, Guizhou Province (E 104° 03′; N 26° 75′, with an altitude of 2200 m and 2307 m) where there were significant differences in lighting and temperature conditions, and at the tobacco research base of Guizhou University in Yangwu Township, Xixiu District, Guizhou Province (E 106° 16′; N 26° 06′, with an altitude of 1250 m).Selected experimental two experimental sites had the same soil nutrient status. Solar radiation, sunshine hours, and temperature data were collected using field meteorological monitoring stations (SCQH-Y9, China), as shown in Fig. 1A–D, The results of the variance analysis of meteorological data can be found in Supplementary Document 1, Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Meteorological data of WN and YW test points. (A) 2021 WN meteorological data. (B) 2021 YW meteorological data. (C) 2022 WN meteorological data. (D) 2022 YW meteorological data.

Test materials and design

Test materials

In previous studies, we have conducted research on the traits, molecules, and molecular aspects of some parents and hybrids41–43. When we expanded the planting area of different materials, we found significant differences in their growth trends under different light and temperature conditions; Therefore, based on the preliminary experimental results, five cultivars with strong regional characteristics, including K326, NC82, JCP2, BN1, and YY87, were selected as parents, and six hybrid combinations were produced using incomplete double row hybridization (NC II) method (Table 1). We ensure that the collection of plant materials and the experimentation and field research of plants comply with relevant institutions, national and international norms and legislation. Floating seedling cultivation method is used for greenhouse sowing. When the seedlings grow to contain five true leaves, they are transplanted into the field.

Table 1.

Material name and number.

| Number | Name | Number | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | K326 | 7 | K326 × JCP2 |

| 2 | NC82 | 8 | K326 × YY87 |

| 3 | JCP2 | 9 | NC82 × BN1 |

| 4 | BN1 | 10 | NC82 × JCP2 |

| 5 | YY87 | 11 | NC82 × YY87 |

| 6 | K326 × BN1 |

Experimental design

The field experiment was conducted using a randomized block design in the tobacco base of Heishi Town, Weining County and the tobacco research base of Guizhou University in Yangwu Township, Xixiu District in 2021 and 2022. Land with no difference in soil nutrient status was selected for planting, with three biological replicates and a row spacing of 110 × 55 cm, the field cultivation management measures were executed according to the Guizhou Standard Quality Tobacco Production Program.

Sample preparation

60 days after transplanting, Three healthy and well-grown tobacco plants were selected from each plot, and 9–11 leaf positions were selected for mixing. Three replicates were taken. After being treated with liquid nitrogen, they were stored in a − 80 ℃ ultra-low temperature refrigerator for measuring chlorophyll content and antioxidant system enzyme activity, respectively.

Measurement items and methods

Determination of agronomic traits and biomass

Collected agronomic traits data of the test materials 60 days after transplantation. Measured the natural plant height, natural leaf number, maximum leaf length, maximum leaf width, and stem circumference of tobacco plants according to YC/T 142-2010 “Methods for Investigation and Measurement of Tobacco Agronomic Traits”. The biomass was measured using the method of killing and drying. The entire plant leaves were picked and killed at 105 ℃ for 30 min, and dried to constant weight at 80 ℃ to determine their dry weight.

Determination of photosynthetic indicators

Photosynthetic measurements were conducted using the LI-6400 portable photosynthetic analyzer manufactured by the LICOR company in the United States. The measurements were carried out in clear and windless weather conditions from 9:00 to 11:00 a.m., during the same period as the biomass measurements. The net photosynthetic rate (Pn), transpiration rate (Tr), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), stomatal conductance (Gs). Measured the 9–11 leaves and performed three biological replicates.

Determination of chlorophyll content

Extract chlorophyll according to Lichtenthale’s method44, and use a UV spectrophotometer (SPECORD200 PLUS, German) to measure the absorbance at 470 nm, 649 nm, and 665 nm, respectively. Calculate the contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotene.

Determination of antioxidant system enzymes

POD, SOD, and CAT in mesophyll tissue were extracted using a Grace, China assay kit. Enzyme activity was measured using a SpectraMax i3x (the United States) at wavelengths of 470 nm, 450 nm, and 510 nm45–47, with three replicates of the technique.

Data statistical analysis

Principal component analysis, membership function analysis, and stepwise regression were conducted using Excel 2016 and SPSS 25 software. Principal component analysis is a multivariate statistical method that examines the correlation between multiple variables. Using the membership function formula, convert the values obtained from principal component analysis into the membership function value Y for the comprehensive evaluation of tobacco photothermal sensitivity. The calculation method for the comprehensive evaluation value Y, membership function value µ, and contribution rate W of tobacco photothermal sensitivity is as follows:

Firstly, used formula

This method calculates the comprehensive evaluation index Y of photothermal sensitivity of 11 tobacco cultivars under different light and temperature conditions, in order to obtain a comprehensive evaluation result of photothermal sensitivity of different tobacco cultivars. Specifically, the study first extracted the main features of the variety through principal component analysis and transformed these features into membership function values to better reflect the variety’s photothermal sensitivity. The importance (W) of each principal component was determined, and the differences between the principal component values and their maximum values for each variety were calculated, as well as the contribution rates of each principal component to the photothermal sensitivity (P) of tobacco cultivars. And these tobacco cultivars are based on these evaluation indicators (µ) and classified through cluster analysis.

Used the RCORR function in the R package HMISC to calculate the Spearman correlation coefficient, used the R package PHEATMap to draw a heat map, and used the R package GGPLOT2 to draw scatter plots, PCA plots, and cluster heat maps. Used GraphPad Prism5 for significance analysis, plot bar charts, and trait squares.

Results and analysis

Analysis of differences in agronomic traits of test materials

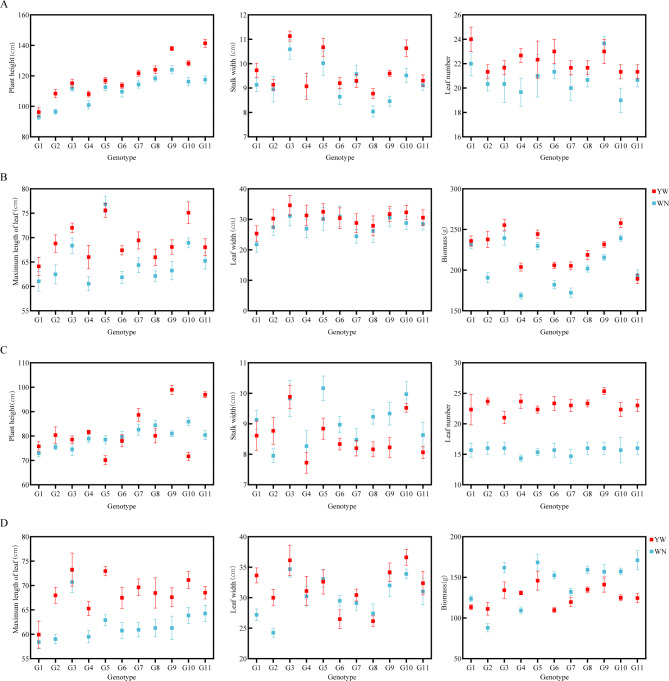

We investigated 6 agronomic traits of 11 experimental materials, YW (Yangwu) and WN (Weining), under different light and temperature environments in 2021 and 2022 (Fig. 2A–D, Supplementary Document 1, Table 2). We found that there were significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) in plant height, stem circumference, maximum leaf length, maximum leaf width, biomass and other traits between these 11 experimental samples at the two experimental points, indicating that there were significant differences in the traits of the selected materials in 2021 and 2021, which can be used to study their sensitivity to the environment.

Fig. 2.

Agronomic traits of 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022. (A) Plant height, stem circumference, and number of leaves of the tested materials in 2021. (B) The maximum leaf length, leaf width, and biomass of the tested materials in 2022. (C) Plant height, stem circumference, and number of leaves of the tested materials in 2022. (D) The maximum leaf length, leaf width, and biomass of the tested materials in 2022.

Among the differences in agronomic traits between the two experimental sites in 2021, G11 had the largest difference in plant height, reaching 23.85 cm; The stem circumference difference of G9 is the largest, reaching 1.13 cm; The maximum leaf length difference of G3 is the largest, reaching 8.43 cm; The difference in the number of natural leaves in G3 is the largest, reaching 2; The biomass difference of G2 is the largest, reaching 45.12 g, and significantly higher than the other test materials. In mid-2022, the difference in plant height was the highest with G9, reaching 17.95 cm; The maximum difference in stem circumference was found in G2, reaching 0.82 cm; The maximum leaf length difference is the highest in G5, reaching 10.05 cm; The maximum difference in leaf width is G1, reaching 6.46 cm; The difference between the number of natural leaves and G4 is the highest, reaching 9.33; The maximum difference in biomass was found in G11, reaching 46.56 g, which was significantly higher than other materials. This indicates that the selected material exhibits different reactions to light and temperature, which can be used to study photothermal sensitivity of tobacco.

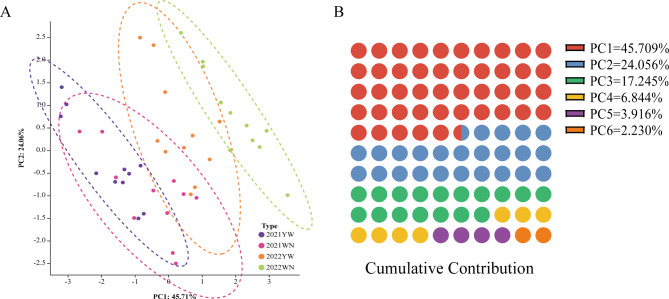

Screening of important agronomic traits

The principal component analysis results of photothermal sensitivity of 11 tobacco cultivars at different experimental points from 2021 to 2022 are shown in Fig. 3.The results showed that the test materials from different years and test points were grouped together, indicating reliable and stable data. PCA data analysis shows that the contribution rate of the first three principal components accounts for 87.010% of the traits of 44 test materials, and the first three principal components can be used for evaluation. The variance contribution rate of the first principal component is 45.709%, representing the principal components of biomass, maximum leaf length, plant height, and stem circumference. The variance contribution rate of the second principal component is 24.056%, mainly composed of the leaf width principal component. The variance contribution rate of the third principal component is 17.245%, mainly composed of the leaf number principal component (Supplementary Document 1, Table 3A,B).

Fig. 3.

Principal component analysis of agronomic traits of 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022. (A) PCA chart of 11 tobacco cultivars YW and WN from 2021 to 2022. (B) Principal component cumulative contribution rate.

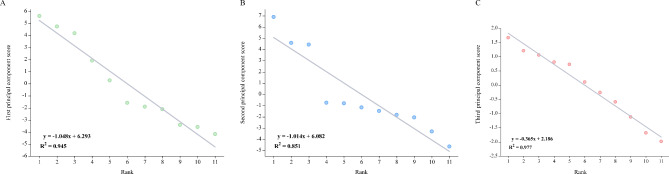

Construction and application of an evaluation model for agronomic traits of photothermal sensitivity of tobacco

To eliminate the impact of data dimensions in the comprehensive score, we first standardized the plant height, stem circumference, natural leaf number, maximum leaf length, leaf width, and biomass of two experimental sites from 2021 to 2022. Based on the standardized values and load matrix, obtain a linear equation (Fig. 4) for each principal component score, and then use the variance contribution rates corresponding to the three principal components as weight coefficients to establish a comprehensive evaluation score model. The regression linear equation and comprehensive evaluation model for the three principal component scores are as follows:

Fig. 4.

Comprehensive score value. (A) The first principal component score. (B) The second principal component score. (C) The third principal component score. The X-axis is for rankting, and the Y-axis is for each principal component score.

where, X1 ~ X6 respectively represent biomass, maximum leaf length, plant height, stem circumference, leaf width, and natural leaf number. The results showed that the ranking of principal components 1, 2, and 3 showed a downward trend, with fitting coefficients R2 values of 0.945, 0.851, and 0.977, respectively.

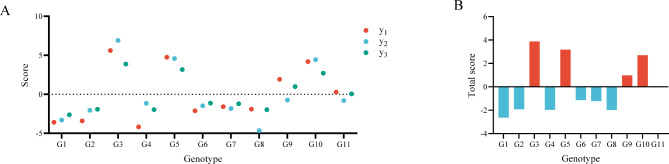

Identification of photothermal sensitivity of test materials

The comprehensive scores of photothermal sensitivity of tobacco in YW and WN experiments from 2021 to 2022 were calculated using the above model (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Document 1, Table 4), and the results were accumulated (Fig. 5B). The light temperature sensitivity ranking of 11 tobacco cultivars is G3 < G5 < G10 < G9 < G11 < G6 < G7 < G2 < G4 < G8 < G1.

Fig. 5.

The photothermal sensitivity scores for 11 test materials, YW and WN, from 2021 to 2022. (A) The light temperature sensitivity scores of 11 test materials in YW and WN from 2021 to 2022. (B) Total score.

The data of 6 agronomic traits from 11 experimental materials were normalized and subjected to cluster analysis (Fig. 6). The results showed that 11 tobacco cultivars (lines) were classified into 3 categories: insensitive, intermediate, and sensitive. The first type of insensitive materials include G3, G5, and G10; The second type of intermediate material includes G9; The third type of sensitive materials include G1, G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, and G11.

Fig. 6.

Cluster analysis of photothermal sensitivity of 11 test materials.

Physiological and biochemical index evaluation of photothermal sensitivity of test materials

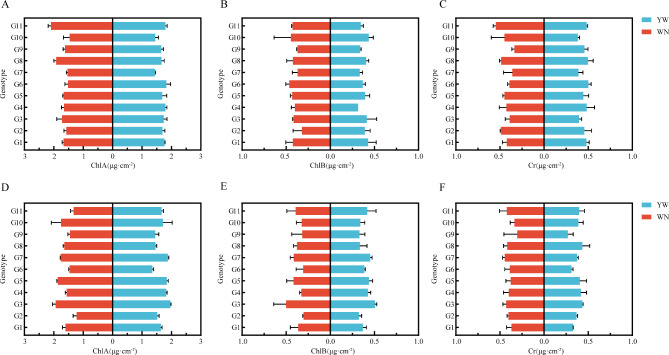

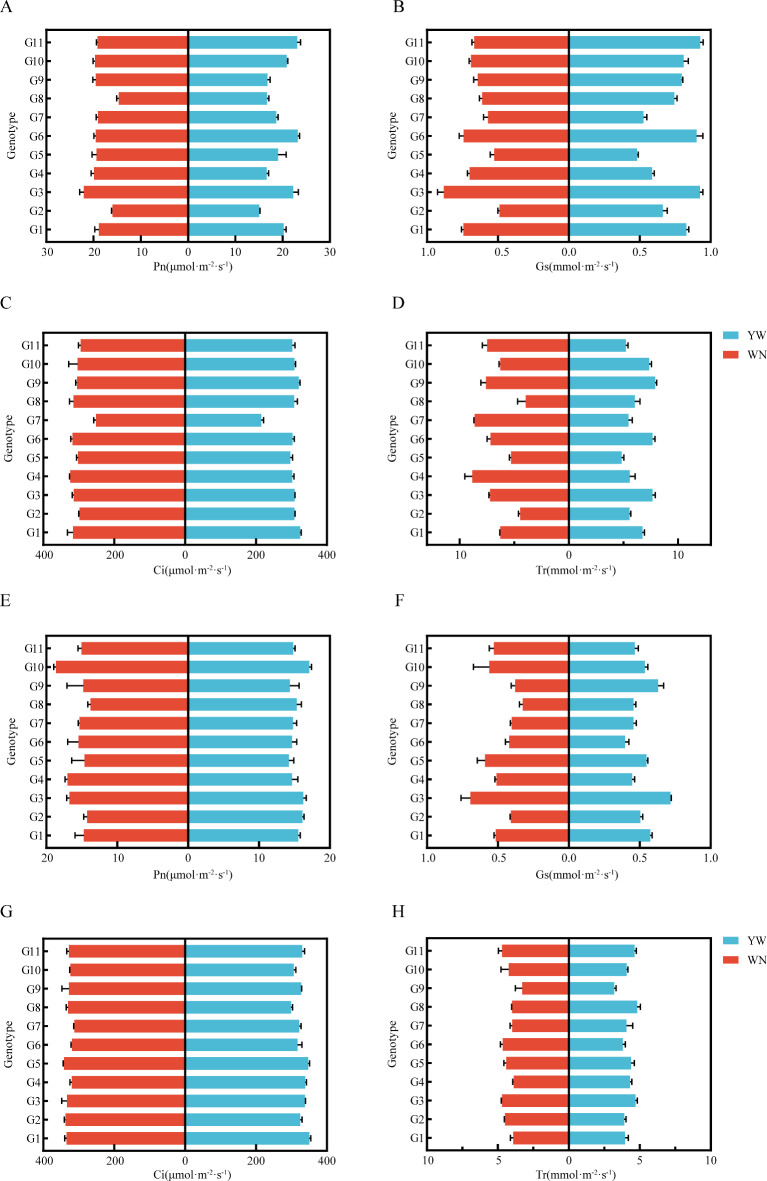

Evaluation of photosynthetic ability: photothermal sensitivity of test materials

We measured the chlorophyll and photosynthetic characteristics of 11 test materials and found that different light and temperature environments affected the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic characteristics of tobacco (Fig. 7, Supplementary Document 1, Tables 5 and 6).The amplitudes of ChlA, ChlB, and Cr at the two experimental sites in 2021 were 2.09–1.46, 0.46–0.32, 0.50–0.34, respectively. Among them, G3, G5, and G10 did not show any differences in the two experiments from 2021 to 2022, and were insensitive to light temperature response. Further measurements were conducted on the Pn, Gs, Ci, and Tr of 11 tobacco cultivars under two different light and temperature environments (Fig. 8). It was found that in 2021, the variation ranges of Pn, Gs, Ci, and Tr of the tested materials at the two experimental sites were 23.23 ~ 14.67, 0.93 ~ 0.493, 24.33 ~ 215.00, 7.92 ~ 3.95, respectively; The variation ranges of Pn, Gs, Ci, and Tr of the tested materials at two experimental points in 2022 are 18.63 ~ 13.73, 0.72 ~ 0.32351.00 ~ 299.00, and 4.82 ~ 3.21, respectively. The results showed that in different light and temperature environments, there were significant differences in the photosynthetic parameters of G2, G4, G6, G8, G9, and G11 between the two regions. In 2022, G2, G4, G8, and G11 showed the same trend. According to the results of the two-year experiment, it can be seen that under different light and temperature environments, the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic parameters of G3, G5, and G10 exhibit stable performance without significant differences, indicating that they belong to the photothermal insensitivity materials; There is a significant difference in chlorophyll content and photosynthetic parameters among G1, G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, and G11, indicating that they are photothermal sensitivity materials.

Fig. 7.

Chlorophyll content of 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022. (A) Chlorophyll a content of the tested materials in 2021. (B) Chlorophyll b content of the tested materials in 2021. (C) The carotene content of the test materials in 2021. (D) Chlorophyll a content of the tested materials in 2022. (E) Chlorophyll b content of the tested materials in 2022. (F) Content of carotene in test materials in 2022.

Fig. 8.

Photosynthetic characteristics of 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022. (A) Pn of the tested materials in 2021. (B) Gs of the tested materials in 2021. (C) Ci of the test materials in 2021. (D) Tr of the tested materials in 2021. (E) Pn of the tested materials in 2022. (F) Gs of the tested materials in 2022. (G) Ci of the test materials in 2022. (H) Tr of the tested materials in 2022.

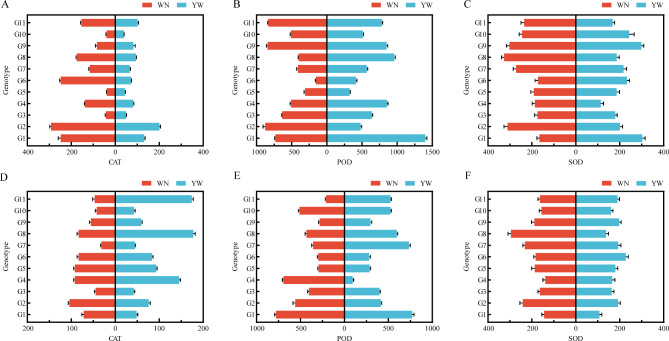

Evaluation of leaf antioxidant system activity: photothermal sensitivity of test materials

The CAT, SOD, and POD of 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022 were measured at two experimental points. Based on the results from 2021 to 2022 (Fig. 9A–F Supplementary Document 1 Tables 7 and 8), it was found that the variation of CAT, POD, and SOD of 11 test materials in 2021 was 293.33 ~ 38.74 U/g, 1399.33 ~ 155.67 U/g, 302.74 ~ 113.40 U/g, and 177.67 ~ 31.68 U/g, 778.67 ~ 94.00 U/g, 295.67 ~ 107.55 U/g, respectively. The results showed that there was no significant difference in CAT, SOD, and POD among G3, G5, and G10 in the past two years. The three test materials showed stable performance at different test points and were insensitive to light and temperature reactions, belonging to the photothermal insensitivity type; G1, G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, and G11 showed significant differences in different light and temperature environments, indicating that the light and temperature adaptability range of the above-mentioned test materials is relatively narrow, and they cannot fully utilize their potential. They are more sensitive to light and temperature conditions and belong to the photothermal sensitivity type of materials; G9 showed inconsistent performance in two years of testing and belongs to the intermediate type material.

Fig. 9.

Antioxidant system activity of 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022. (A) CAT activity of 11 test materials in 2021. (B) POD activity of 11 test materials in 2021. (C) SOD activity of 11 test materials in 2021. (D) CAT activity of 11 test materials in 2022. (E) POD activity of 11 test materials in 2022. (F) SOD activity of 11 test materials in 2022.

Reliability analysis of the evaluation model for agronomic traits of photothermal sensitivity of tobacco

Consistency score of evaluation results between two methods

We have compiled the calculation results of the evaluation model for agronomic traits of photothermal sensitivity of tobacco and the results of conventional identification methods. The results of the evaluation model for agronomic traits of photothermal sensitivity of tobacco were G3< G5< G10< G9< G11< G6< G7< G2< G4< G8< G1. Through cluster analysis, the test materials can be divided into insensitive materials: G3, G5, G10; sensitive materials: G1, G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, G11; Intermediate material: G9; The test materials can be classified into insensitive materials through conventional identification methods: G3, G5, G10; sensitive materials: G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, G11; Intermediate materials: G1, G9. The results showed that the recurrence rate of the two different identification methods was 90.91%, proving the reliability of using the the evaluation model for agronomic traits of photothermal sensitivity of tobacco to identify tobacco photothermal sensitivity.

Scientific analysis of the evaluation model for agronomic traits

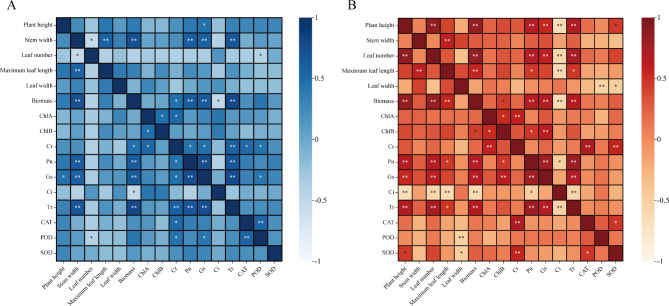

Correlation analysis was conducted on the agronomic traits, chlorophyll content, photosynthetic characteristics, antioxidant system enzyme activity, and other indicators of 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022 (Fig. 10A, B, Supplementary Document 1, Tables 9 and 10). The correlation analysis results showed that under different light and temperature environments, tobacco agronomic traits showed extremely significant (P ≤ 0.01) or significant (P ≤ 0.05) correlations with Pn, Ci, Gs, Chlb, Cr content, SOD, POD, and other indicators. In the 2-year experimental results, all six agronomic traits showed a positive correlation with chlorophyll content and photosynthetic characteristics, while a negative correlation with antioxidant system enzyme activity. The results showed that using agronomic traits to evaluate tobacco light temperature sensitivity is reliable.

Fig. 10.

Correlation heatmap of phenotypic and physiological measurement indicators for 11 test materials from 2021 to 2022. (A) Correlation analysis of phenotypic and physiological measurement indicators among 11 tested cultivars in 2021. (B) Correlation analysis of phenotypic and physiological measurement indicators among 11 tested cultivars in 2022. “*” indicates a significant level of correlation (p < 0.05), and “**” indicates a highly significant level of correlation (p < 0.01).

Discussion

The impact of light and temperature environment on crop growth and development

Light and temperature are the most important environmental factors that affect plant growth, development, and morphogenesis31,48,49. The photoperiod regulates the growth process of plants50, while temperature and radiation51 affect the growth process of plants. After being received by the photoreceptors52,53 and temperature receptors54 of plants, light and temperature signals are integrated with endogenous signals to regulate plant physiological metabolism and hormone levels. A suitable light and temperature environment is conducive to the formation of plant yield55, while an unsuitable light and temperature environment can cause a decrease in plant photosynthesis rate, poor growth and development, ultimately leading to a decrease in yield and quality36,56 Therefore, it is particularly important to choose suitable cultivation crops based on the light and temperature environment. Previous studies on different varieties of forage57 and sugarcane58 under different light and temperature environments have shown that there are differences in light and temperature responses among different cultivars, mainly manifested in growth potential, agronomic shape, and yield. Therefore, coordinating crop cultivars with light and temperature resources59,60 can maximize the potential of cultivars. The results of this study indicate that there are significant differences in the agronomic shapes of 11 test materials between the two test points from 2021 to 2022. Among them, in the YW test point with higher temperature, the agronomic shapes, biomass and other indicators of G1, G2, G4, G6 and other cultivars are significantly higher than those of the WN test point with lower temperature; There was no significant difference between G3 and G5, indicating that different tobacco cultivars have different sensitivities to the comprehensive response to light and temperature. Therefore, it is particularly important to choose suitable cultivation cultivars based on the light and temperature environment.

Evaluation indicators for crop photothermal sensitivity

The photosynthesis of plants is a core function of plant physiology, greatly influenced by light and temperature61, and can be used to prove whether plants are in the optimal growth environment62. As the material basis for energy conversion in photosynthesis, chlorophyll is crucial for plant growth and development. Its content determines the strength of leaf photosynthetic function. Previous studies63 have shown that chlorophyll content can not only serve as an indicator of nutrient levels, but also reflect the tolerance of crops to stress. A large number of studies64–67 have shown that inappropriate light and temperature conditions reduce the activity of photosynthetic enzymes68, or cause damage to leaf tissue, leading to a decrease in the efficiency of plant photosynthetic electron transport chains and the production of excessive superoxide anion free radicals, leading to changes in chlorophyll content, net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and intercellular CO2 concentration. Therefore, previous studies69–72 utilized differences in indicators such as photosynthetic rate, intercellular CO2 concentration, stomatal conductance, and chlorophyll content to determine whether different cultivars of crops were under appropriate light and temperature conditions, and to identify differences between cultivars. Based on this, this study measured the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic characteristics of 11 test materials. The results showed that the chlorophyll a content and net photosynthetic rate of 11 tobacco cultivars at the YW test point from 2021 to 2022 were higher than those at the WN test point, indicating that low temperature had an adverse effect on tobacco photosynthesis, thereby inhibiting the accumulation of dry matter.

Plants have evolved antioxidant systems to cope with adverse environments, playing a crucial role in defense against light and temperature stress during growth and development. Mainly including SOD, POD, CAT, etc73–75. The accumulation of intracellular ROS in crops under inappropriate light and temperature environments can disrupt cellular homeostasis76, and the synchronous action of all these antioxidants leads to ROS removal and protects plants from oxidative damage. Islam77 measured the antioxidant enzyme activity of barley and wheat under different light and temperature conditions, and found that its antioxidant enzyme activity was 1.2–5.7 times higher under inappropriate light and temperature conditions than under suitable light and temperature growth conditions. Therefore, a large number of studies78–81 use the differences in enzyme activity of crop antioxidant systems under different environments to determine whether plants are in a suitable light and temperature growth environment. Based on this, this study measured the SOD, POD, CAT and other indicators of the test materials. The results showed that there were significant differences in SOD, POD, CAT of tobacco cultivars such as G1, G2, G4, G6, G7, and G11 in 2 years of field experiments, indicating that SOD, POD, CAT can be used to characterize the differences in light and temperature at the test points. In summary, indicators such as chlorophyll content, photosynthetic characteristics, and antioxidant enzyme activity are suitable for evaluating the photothermal sensitivity of tobacco.

Evaluation method for crop photothermal sensitivity

The re-evaluation and utilization of crop cultivars is an important way to expand the genetic foundation of breeding and fully utilize seed resources. The quality, yield, and resistance of crops are complex quantitative traits influenced by their own genetic factors and external environmental conditions82,83. It is difficult to accurately and objectively evaluate the quality of germplasm resources using a single indicator84, while comparing crop differences in different environments using traditional methods by measuring multiple indicators is more complex28. So far, modeling analysis has been increasingly applied in plant evaluation85,86. Mathematical models can significantly evaluate different scenarios, make more predictive decisions, and avoid human biases and errors24. This study found that there is a high correlation between various meteorological factors that affect tobacco photothermal sensitivity (Supplementary Document 1, Tables 11 and 12), and ordinary regression analysis may lead to significant errors in the results. Principal Component Analysis87 is a statistical method that converts multiple variables into a few principal components through dimensionality reduction.Therefore, this method can solve problems involving multiple interrelated variables. Transform multiple agronomic traits with certain correlations into several independent and unrelated composite variables, and explain the original information as much as possible. Then, gradually regress the new variables to obtain a principal component regression model; This type of model is more objective and reliable in evaluating results88. However, this method is suitable for large sample analysis, and when the sample size is less than the number of variables, it cannot provide comprehensive conclusions and algorithms; Although the extracted principal components must be able to provide explanations that are consistent with the actual background and meaning, and their meanings are generally somewhat ambiguous, unlike the clear and precise meanings of the original variables.At present, there have been studies on incorporating the obtained principal components into membership functions for analysis23,89, Principal component analysis is the process of generating new, relatively perpendicular coordinates through coordinate changes. The new scale of the research object on the principal component coordinate axis is included as a variable in the membership function analysis, and there is currently no relevant mathematical basis. In fact, the relevant results of membership functions can be used as input data for principal component analysis and cluster analysis90,91, But there is no mature analysis method with the opposite process, we suggest not analyzing in this order. This study analyzed 11 tobacco cultivars under different lighting and temperature environments. Although the limitation of evaluating at a single experimental site was ruled out, the number of experimental sites was still limited; If we can increase the number of test sites and arrange the lighting and temperature conditions in a gradient, the results obtained may be more reliable. This study only used the agronomic traits of tobacco for rapid analysis, which can greatly improve the efficiency of identification, but ignored the importance of tobacco chemical composition; We referred to previous methods for identifying crop photosensitivity and measured physiological indicators such as chlorophyll content, photosynthetic characteristics, and antioxidant enzyme activity in tobacco to validate the model results. However, we should also pay more attention to the overall performance of plant growth, such as critical points such as wilting and death, and incorporate them into physiological indicator analysis to draw more scientific conclusions. Next, we can focus on key traits and use this method to screen for sensitive and insensitive tobacco cultivars, create mutant plants, and further analyze the mechanism of tobacco photothermal sensitivity.

Conclusion

This study established a comprehensive evaluation model for tobacco photothermal sensitivity based on agronomic trait data: y = 0.4571y1 + 0.2406y2 + 0.1725y3. Referring to previous methods for identifying crop photothermal sensitivity, the evaluation model was validated using physiological indicators such as photosynthetic characteristics, chlorophyll content, and antioxidant enzyme system activity of the test materials. It was found that the reliability of the identification results of the agronomic trait evaluation model reached 90.91%. This study provides an efficient evaluation method for the sensitivity of tobacco cultivars to light and temperature, which has important theoretical value and practical significance for the breeding of tobacco insensitive cultivars and the study of regional distribution of cultivars.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the editor and reviewers for critically evaluating the manuscript and providing constructive comments for its improvement.

Abbreviations

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- YW

Yangwu test point

- WN

Weining test point

- Pn

Net photosynthetic rate

- Gs

Stomatal conductance

- Ci

Intercellular carbon dioxide concentration

- Tr

Transpiration rate

- CAT

Catalase

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- POD

Peroxidase

Author contributions

Author 1 (First Author): Conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft; validation. Author 2: Data curation, writing—original draft; Author 3: Visualization, investigation, formal analysis; Author 4: Resources, supervision, software; Author 5: Software, validation; Author 6: Visualization, supervision; Author 7: Visualization, supervision; Author 8: Investigation, validation; Author 9: Investigation, validation; Author 10: Investigation, validation; Author 11: Visualization, resources; Author 12: Visualization, resources; Author 13: Visualization, writing—review & editing; Author 14: Visualization, writing - review & editing; Author 15 (Corresponding Author): Conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing—review & editing.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32060510), Guizhou Tobacco Company (2022XM02).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Franklin, K. A. Light and temperature signal crosstalk in plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol.12, 63–68 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith, H. Phytochrome and photomorphogenesis in plants. Nature. 227, 665–668 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quint, M. et al. Molecular and genetic control of plant thermomorphogenesis. Nat. Plants. 2, 15190 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Major, D. J. Effects of daylength and temperature on soybean development1. Crop Sci.15, 174–179 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang, D. R. et al. Positive effects of public breeding on us rice yields under future climate scenarios. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.121, e1984998175 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Springate, D. A. K. P. Plant responses to elevated temperatures: a field study on phenological sensitivity and fitness responses to simulated climate warming. Glob. Change Biol. 456–465 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cober, E. R., Stewart, D. W. & Voldeng, H. D. Photoperiod and temperature responses in early-maturing, near-isogenic soybean lines. Crop Sci.41, 721–727 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poneleit, C. G. D. B. E. Kernel Growth Rate and Duration in Maize as Affected by Plant Density and Genotype (Crop Sci, 1979).

- 9.Li, X., Liang, T. & Liu, H. How plants coordinate their development in response to light and temperature signals. Plant. Cell.34, 955–966 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lisuma, J. B., Semoka, J. M. & Mbwambo, A. F. Effect of timing fertilizer application on leaf yield and quality of tobacco. Heliyon. 9, e19670 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Long, S. P. Photosynthesis engineered to increase rice yield. Nat. Food. 1, 105 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derek, M. & Wright, S. N. T. H. Understanding photothermal interactions will help expand production range and increase genetic diversity of lentil (Lens Culinaris Medik.). Plants People Planet. 171–181 (2021).

- 13.Wang, C. & Wu, T. Changes in photo-thermal sensitivity of widely grown Chinese soybean cultivars due to a century of genetic improvement. Plant. Breed. 94–104 (2015).

- 14.McClung, C. R., Lou, P., Hermand, V. & Kim, J. A. The importance of ambient temperature to growth and the induction of Flowering. Front. Plant. Sci.7, 1266 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, G. et al. Optimizing planting density and impact of panicle types on grain yield and microclimatic response index of hybrid rice (Oryza Sativa L). Int. J. Plant. Prod.15, 447–457 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alsajri, F. A. et al. Morpho-physiological, yield, and transgenerational seed germination responses of soybean to temperature. Front. Plant. Sci.13, 839270 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long, T., Bai, G. & Fu, M. Study on photoperiod sensitivity of 10 maize inbred lines in Southwest China. J. Mt. Agric. Biol. 33 (02), 5–9 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fei, Z. et al. Comprehensive identification of light temperature response in soybean varieties through photoperiod treatment and staged sowing experiments. J. Crops. 35 (08), 1525–1531 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia, X. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the main agronomic traits of foxtail millet resources under different light and temperature conditions. Chin. Agricultural Sci.51 (13), 2429–2441 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lou, W., Ji, Z. & Wen, H. Sensitivity analysis of biochemical components of spring tea in Longjing 43 to meteorological factors. J. Ecol.33 (02), 328–334 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamshidi, S. et al. Modeling interactions of planting date and phenology in Louisiana Rice under current and future climate conditions. Crop Sci.64, 2274–2287 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu, T. & Lu, S. Molecular breeding for improvement of Photothermal adaptability in soybean. Mol. Breed.60, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Chang, T. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of high-oleic rapeseed (Brassica Napus) based on quality, resistance, and yield traits: a new method for rapid identification of high-oleic acid rapeseed germplasm. Plos One. 17, e272798 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, X. et al. A comprehensive yield evaluation indicator based on an improved fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method and hyperspectral data. Field Crop Res.270, 108204 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yadav, N. et al. Physiological response and agronomic performance of drought tolerance mutants of Aus Rice Cultivar Nagina 22 (Oryza Sativa L). Field Crop Res.290, 108760 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bao, Y. et al. Analysis of overwintering indexes of Winter Wheat in Alpine regions and establishment of a cold resistance model. Field Crop Res.275, 108347 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong, C., Fu, Y., Liu, G. & Liu, H. Low light intensity effects on the growth, photosynthetic characteristics, antioxidant capacity, yield and quality of wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) at different growth stages in Blss. Adv. Space Res.53, 1557–1566 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khanzada, A. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of high-temperature tolerance induced by heat priming at early growth stages in winter wheat. Physiol. Plant.174, e13759 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racz, A. et al. Fight against cold: photosynthetic and antioxidant responses of different Bell Pepper cultivars (Capsicum Annuum L.) to cold stress. Biol. Futura. 74, 327–335 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huo, H., Wei, S. & Bradford, K. J. Delay of Germination1 (Dog1) regulates both seed dormancy and flowering time through microrna pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.113, E2199–E2206 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Ruelland, E. & Zachowski, A. How plants sense temperature. Environ. Exp. Bot.69, 225–232 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, Y. et al. Cold stress in the harvest period: effects on tobacco leaf quality and curing characteristics. Bmc Plant. Biol.21, 131 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu, B. et al. The influence of light quality on the accumulation of flavonoids in tobacco (Nicotiana Tabacum L.) leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B-Biol. 162, 544–549 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu, C. et al. Effects of prolonged light exposure on the growth, development, and photosynthetic characteristics of tobacco leaves. Northwest. Bot. J.33 (04), 763–770 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan, K. & Chen, Z. Effects of different ecological conditions on the morphology and related physiological indicators of flue-cured Tobacco. J. Ecol.32 (10), 3087–3097 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, F. et al. Phytochrome a and B function antagonistically to regulate cold tolerance via abscisic acid-dependent jasmonate signaling1[Open]. Plant. Physiol. (Bethesda). 170, 459–471 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu, G. et al. The effects of long-term shading and light conversion on the photosynthetic efficiency of different tobacco varieties. Chin. Agric.Sci.10, 2368–2375 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, Z. Monitoring of high-temperature ripening indicators and the effect of light and temperature on the photosynthetic physiology of southern Hunan tobacco. Zhengzhou University, MA Thesis. (2017).

- 39.Deng, J. et al. Review of the effects of light and temperature conditions on the growth, development, and quality formation of flue-cured Tobacco. Crop Res.29 (06), 678–681 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiang, D. A brief discussion on the three dimensional climate resources and agricultural structure adjustment in Guizhou. South. Agric.9 (15), 183–184 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pi, K. et al. Negative regulation of tobacco cold stress tolerance by Ntphya. Plant. Physiol. Biochem.204, 108153 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu, A. et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals the key role of overdominant expression of photosynthetic and respiration-related genes in the formation of Tobacco(Nicotiana Tabacum L.) Biomass Heterosis. BMC Genom.25, 598 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pi, K. & Huang, Y. Overdominant expression of genes plays a key role in Root Growth of Tobacco hybrids. Front. Plant. Sci. 1107550 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: measurement and characterization by Uv-Vis spectroscopy. Curr.Protoc. Food Anal. Chem.1, F3–F4 (2001).

- 45.Dragišić Maksimović, J. J., Poledica, M. M., Radivojević, D. D. & Milivojević, J. M. Enzymatic Profile of ′Willamette′ Raspberry Leaf and Fruit affected by Prohexadione-Ca and young canes removal treatments. J. Agric. Food Chem.65, 5034–5040 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gutteridge, J. M. & Halliwell, B. The measurement and mechanism of lipid peroxidation in biological systems. Trends Biochem. Sci.15, 129–135 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo, J. et al. Isolation and identification of algicidal compound from streptomyces and algicidal mechanism to microcystis aeruginosa. PLoS One. 8, e76444 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chory, J. & Wu, D. Weaving the complex web of signal transduction. Plant. Physiol.125, 77–80 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, X. et al. The effect of different light quality LED weak light on the morphology and photosynthetic performance of cherry tomato plants. Northwest. Bot. J.30 (04), 725–732 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song, Y. et al. Application and comparison of three light temperature models in simulating Rice Growth stages. J. Ecol.33 (12), 3262–3267 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, M. et al. Simulation of flue-cured tobacco leaf area and dry matter yield based on the radiant heat product method. J. Ecol.33 (22), 7108–7115 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kami, C., Lorrain, S., Hornitschek, P. & Fankhauser, C. Light-regulated plant growth and development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol.91, 29–66 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen, M. & Chory, J. Phytochrome signaling mechanisms and the control of plant development. Trends Cell. Biol.21, 664–671 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jung, J. H. et al. Phytochromes function as thermosensors in arabidopsis. Science. 354, 886–889 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu, Y., Wang, E., Yang, X. & Wang, J. Contributions of climatic and Crop Varietal changes to crop production in the North China Plain, since 1980S. Glob. Change Biol.16, 2287–2299 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bisbis, M. B., Gruda, N. & Blanke, M. Potential impacts of climate change on vegetable production and product quality—a review. J. Clean. Prod.170, 1602–1620 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iannucci, A., Terribile, M. R. & Martiniello, P. Effects of temperature and photoperiod on flowering time of forage legumes in a mediterranean environment. Field Crop Res.106, 156–162 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dias, H. B. et al. Traits for Canopy development and light interception by twenty-seven Brazilian sugarcane varieties. Field Crop Res.249, 107716 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou, B. et al. Wheat growth and grain yield responses to sowing date-associated variations in weather conditions. Agron. J.112, 985–997 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah, F., Coulter, J. A., Ye, C. & Wu, W. Yield Penalty due to delayed sowing of winter wheat and the mitigatory role of increased seeding rate. Eur. J. Agron.119, 126120 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berry, J. O. B. Photosynthetic Response and Adaptation to Temperature in Higher Plants (Annual Review of Plant Physiology, 1980).

- 62.Calatayud, A., Iglesias, D. J., Talón, M. & Barreno, E. Effects of long-term ozone exposure on Citrus: Chlorophyll a fluorescence and gas exchange. Photosynthetica. 44, 548–554 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neufeld, H. S. et al. Visible Foliar Injury caused by ozone alters the relationship between spad meter readings and chlorophyll concentrations in cutleaf coneflower. Photosynth. Res.87, 281–286 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu, L., Wang, Z. & Huang, B. Diffusion limitations and Metabolic Factors Associated with Inhibition and Recovery of Photosynthesis from Drought stress in a C perennial grass species. Physiol. Plant.139, 93–106 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben-Asher, J., Tsuyuki, I., Bravdo, B. & Sagih, M. Irrigation of grapevines with saline water: I. Leaf Area Index, stomatal conductance, transpiration and photosynthesis. Agric. Water Manage.83, 13–21 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang, L. et al. Effects of low temperature stress on leaf tissue structure and physiological indicators of cashew seedlings. J. Ecol. Environ.18 (01), 317–320 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farquhar, G. D. S. V. C. J. A biochemical model of photosynthetic Co 2 assimilation in leaves of C 3 species. Planta 78–90 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Sassenrath, G. F. O. D. The relationship between inhibition of photosynthesis at low temperature and the inhibition of Photosynthesis after rewarming in Chill-Sensitive Tomato. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. (Paris). 28 (4), 457–465 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hou, W. et al. Effects of Chilling and High temperatures on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in leaves of Watermelon seedlings. Biol. Plant.60, 148–154 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asada, K. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their Functions1. Plant. Physiol. (Bethesda). 141, 391–396 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nadarajah, K. K. Ros Homeostasis in Abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Foyer, C. H. & Noctor, G. Redox regulation in photosynthetic organisms: signaling, acclimation, and practical implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal.11, 861–905 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choudhury, S., Panda, P., Sahoo, L. & Panda, S. K. Reactive oxygen species signaling in plants under Abiotic Stress. Plant. Signal. Behav.8, e23681 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choudhury, F. K., Rivero, R. M., Blumwald, E. & Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J.90, 856–867 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Awad, J. et al. 2-Cysteine peroxiredoxins and thylakoid ascorbate peroxidase create a water-water cycle that is essential to protect the photosynthetic apparatus under high light stress Conditions1. Plant. Physiol. (Bethesda). 167, 1592–1603 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hussain, H. A. et al. Chilling and drought stresses in crop plants: implications, cross talk, and potential management opportunities. Front. Plant. Sci.9, 393 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Islam, M. Z. et al. Assessment of biochemical compounds and antioxidant enzyme activity in Barley and Wheatgrass Under Water-Deficit Condition. J. Sci. Food Agric.102, 1995–2002 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jaspers, P. & Kangasj Rvi, J. Reactive oxygen species in abiotic stress signaling. Physiol. Plant.138, 405–413 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lv, X. et al. The role of calcium-dependent protein kinase in hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide and Aba-Dependent Cold Acclimation. J. Exp. Bot.69, 4127–4139 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou, J. et al. Rboh1-Dependent H2O2 production and subsequent activation of Mpk1/2 play an important role in Acclimation-Induced Cross-tolerance in Tomato. J. Exp. Bot.65, 595–607 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xia, X. et al. Reactive oxygen species are involved in Brassinosteroid-Induced stress tolerance in Cucumber1[W]. Plant. Physiol. (Bethesda). 150, 801–814 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen, W. et al. Detection of qtl for six yield-related traits in Oilseed rape (Brassica Napus) using dh and immortalized F2 populations. Theor. Appl. Genet.115, 849–858 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu, R. et al. Characterization of a rapeseed anthocyanin-more mutant with enhanced resistance to Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. J. Plant. Growth Regul.39, 703–716 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shi, S. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of 17 qualities of 84 types of rice based on principal component analysis. Foods. 10, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Jaskulak, M., Grobelak, A. & Vandenbulcke, F. Modelling assisted phytoremediation of soils contaminated with Heavy metals—Main opportunities, limitations, decision making and future prospects. Chemosphere. 249, 126196 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alvarez-Vázquez, L. J., Martínez, A., Rodríguez, C., Vázquez-Méndez, M. E. & Vilar, M. A. Mathematical analysis and optimal control of heavy metals phytoremediation techniques. Appl. Math. Model.73, 387–400 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Abdi, H. W. L. J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat.4, 433–459 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Greenacre, M. et al. Principal component analysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers. 2, 100 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu, Y. Q. Z. Z. Comprehensive evaluation of Luzhou-Flavor Liquor Quality based on fuzzy mathematics and principal component analysis. Food Sci. Nutr. 1780–1788 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Marengo, E., Robotti, E., Righetti, P. G. & Antonucci, F. New approach based on fuzzy logic and principal component analysis for the classification of two-dimensional maps in health and disease. Application to Lymphomas. J. Chromatogr. A. 1004, 13–28 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Legendre, P. Numerical ecology. In Encyclopedia of Ecology, 2nd ed. (ed. Fath, B.) 487–493 (Elsevier, 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.