Abstract

Exosomes derived from the stem cells of human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) hold promise for tissue regeneration. Apoptotic cells release a variety of extracellular vesicles that affect intercellular communication. This study aimed to investigate the angiogenic effects of SHED-derived exosomes modified via apoptosis induction on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Apoptosis was induced in SHED via serum starvation for 3 weeks and confirmed by the upregulation of the apoptotic genes, caspase 3 and 9, and via annexin V staining. The apoptotic SHED-derived exosomes were isolated, characterized, and subjected to proteomic analysis. In vitro experiments were performed to assess the effects of apoptotic SHED exosomes on the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of HUVECs. The apoptosis-induced SHED showed increased cell viability and decreased numbers of dead cells compared with those of conventional cultures while retaining their identity as mesenchymal stem cells positive for CD44, CD73, and CD90. The apoptotic SHED-derived exosomes exhibited characteristic features, such as standard size, cup-shaped morphology, and positive staining, for exosomal markers CD9, CD63, and CD81. Proteins associated with apoptosis, programmed cell death, and cellular senescence were downregulated in the apoptotic SHED exosomes, whereas those associated with extracellular matrix organization were upregulated, indicating positive angiogenesis. HUVECs treated with apoptotic SHED exosomes exhibited significantly enhanced proliferation and migration compared with those treated with normal SHED exosomes. The mesh-like structures in the apoptotic SHED exosomes exhibited significantly increased signs of angiogenesis. The findings of this study provide new insights into the potential use of apoptotic SHED-derived exosomes in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-79692-6.

Keywords: Extracellular vesicles, Programed cell death, Neovascularisation, Mesenchymal stem cell, Regeneration, Homeostasis

Subject terms: Cell biology, Stem cells

Introduction

Apoptosis, a ubiquitous process in tissue development, repair, and regeneration, encompasses cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, and nuclear condensation and fragmentation1. Traditionally considered as a silent form of cell death, it is now recognized that apoptotic cells release mitogenic signals that stimulate proliferation in neighboring cells in a nonautonomous manner2. Evidence indicates that apoptosis is crucial in initiating tissue regeneration and maintaining tissue homeostasis, as observed in various contexts where tissue destruction precedes regeneration2–4 However, the precise underlying mechanism involved remains unclear.

In the field of regenerative dentistry, successful tissue regeneration relies on effective vascularization, which ensures the delivery of progenitor cells, nutrients, growth factors, and oxygen to the healing area and the removal of waste products5. Angiogenesis, which refers to the formation of new blood vessels from existing ones, facilitates the transport of growth factors essential for cell viability and interaction5,6.

Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) are gaining attention as a promising avenue for tissue regeneration because of their immature state, rapid proliferation, and differentiation potential7. Recent studies indicate that the therapeutic potential of stem cell-based therapies largely originates from the paracrine secretion of bioactive factors and extracellular vesicles (EVs)8,9. These factors modulate tissue homeostasis and regeneration by influencing the local environment10.

Exosomes, a specific type of EV, are critical in intercellular communication and tissue regeneration. They carry a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including proteins, microRNAs (miRNAs), messenger RNAs (mRNAs), and lipids11. Exosomes reflect the molecular signature of their parent cells, and their content can be altered under stress conditions, such as hypoxia or oxidative stress, which can affect their physiological function12,13. SHED-derived exosomes have positive effects on the angiogenic ability of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro9,13,14. However, despite the established potential of SHED-derived exosomes, their effects under apoptotic microenvironments remain unclear. Apoptotic cells release a heterogeneous population of apoptotic EVs, including apoptotic bodies, apoptotic microvesicles, and apoptotic exosomes, which play a role in communication with neighboring cells and tissue remodeling15. Currently, evidence regarding the angiogenic support provided by SHED-derived exosomes under apoptotic conditions is lacking. Hence, this study aimed to investigate the angiogenic effect of apoptosis-induced SHED-derived exosomes on HUVECs to explore the potential of modified SHED exosomes as a promising treatment option in regenerative dentistry.

Materials and methods

Cell cultivation

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethical Committee on Human Rights Related to Human Experimentation of the Faculty of Dentistry/Faculty of Pharmacy (MUDT/PY-IRB 2023/026.2606). SHED were isolated and cultured as described previously16 and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, HyClone, Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biochrome, Berlin, GY), and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK). Cells from passages 5 to 7 were used for the experiments. HUVECs were obtained from Siriraj Stem Cell and Advanced Vascular and Endovascular Research (SiSCR), Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University. Cells from passages 3–5 were cultured in fibronectin-coated flasks using the endothelial cell growth medium (EGM) EndoGRO-VEGF Complete Culture Media Kit (Merck Ltd, Darmstadt, GY) supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.5% Penicillin–Streptomycin. Both cell types were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

Apoptosis induction

SHED were induced to undergo apoptosis through serum starvation, a natural method that avoids the use of toxic chemicals or harmful residues17,18. SHED were cultured in a growth medium containing 10%FBS until they reached 80% confluence, followed by a switch to an FBS-free medium for 3 weeks without replacement. Apoptosis induction was confirmed by analyzing the mRNA expression of caspase 3 and caspase 9 and conducting the MUSE® Annexin V & Dead Cell Assay Kit staining experiment (see Supplementary information). The controls consisted of normal SHED cultured for 2 days under standard conditions.

Both apoptosis-induced and control SHED were assessed for their mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) characteristics by labeling them with monoclonal antibodies specific for human mesenchymal lineage markers, such as CD44, CD73, and CD90 (all purchased from BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Flow cytometry was conducted using a FACSCanto flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Isolation and characterization of SHED exosomes

Exosomes isolation and characterization were conducted as described in previous studies9,14,19. Both normal and apoptosis-induced SHED were washed three times with phosphate-buffer saline (PBS) and then incubated in DMEM without FBS and antibiotic. After 48 h of incubation, conditioned media (CM) from both normal and apoptosis-induced SHED were collected. The CM was centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 min, filtered through 0.2 μm filters, and then concentrated using Amicon® Ultra-15 10 kDa centrifugal filters (Merck-Millipore, Merck Ltd., Darmstadt, GY) at 5,000 ×g for 40 min. The exosomes were isolated via differential ultracentrifugation at 100,000 ×g for 70 min at 4 °C, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and stored at − 80 °C. The concentration of the exosomes was assessed using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. Subsequently, the characteristics of the exosomes, including the particle size distribution, morphology, and presence of exosome-specific markers (CD9, CD63, and CD81 from ThermoFisher Scientific), were determined via nanoparticle tracking analysis, transmission electron microscopy, and flow cytometry, respectively.

Additionally, the exosomes were labeled with the PHK67 green fluorescent cell linker kit (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) to examine the internalization by HUVECs.

Proteomic analysis

Proteomic analysis was performed at the Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS; Orbitrap LC-MS, ThermoFisher Scientific). An Orbitrap HF mass spectrometer, coupled with an EAST-nLC1000 nano-LC system and a nano-C18 column, was used for the LC-MS/MS analysis of the exosomal protein samples (2 μg). Separation was achieved over 125 min with a linear gradient. Data-dependent (TopN15) acquisition with higher-energy collision dissociation at a collision energy of 28 was employed. Full scan mass spectra were acquired from m/z 375 to 1,300, with an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 3 × 106 ions and a resolution of 120,000. The MS/MS scans were initiated at an AGC of 5 × 104 ions and a resolution of 15,000. Further details are provided in the Supplementary file.

Effects of SHED exosomes on angiogenesis

HUVECs treated with 10 μg/ml of both normal and apoptosis-inducing SHED exosomes were used in all the experiments. HUVECs cultured in EGM were used as positive control, and those cultured in DMEM served as the negative control. Further details are provided in Supplementary file.

Proliferation assay

The HUVECs were seeded in fibronectin-coated 96-well plates, and cell proliferation was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay (CCK-8 assay, Dojindo, Kumamoto, JP).

Migration assay

Scratch assays were performed to evaluate cell migration. The closure distance was determined using Image Analysis J software (Olympus, Alexandra, SG).

Tube formation assay

HUVECs were seeded onto Matrigel-coated (Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA) wells. After 6 and 12 h, images of the network structures were captured using phase contrast microscopy and analyzed quantitatively using WimTube software (Onimagin Technologies SCA, Córdoba, SP).

CD31 immunofluorescence staining

The network structures were stained with anti-CD31 antibody, and the staining intensity was analyzed using confocal microscopy (Leica Microsystems CMS GmbH).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was conducted in triplicate and independently repeated at least three times. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data characteristics. Student’s t-test was used for two-group comparisons, and one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s test was used for multiple comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Apoptotic SHED exhibited mesenchymal stem cell markers

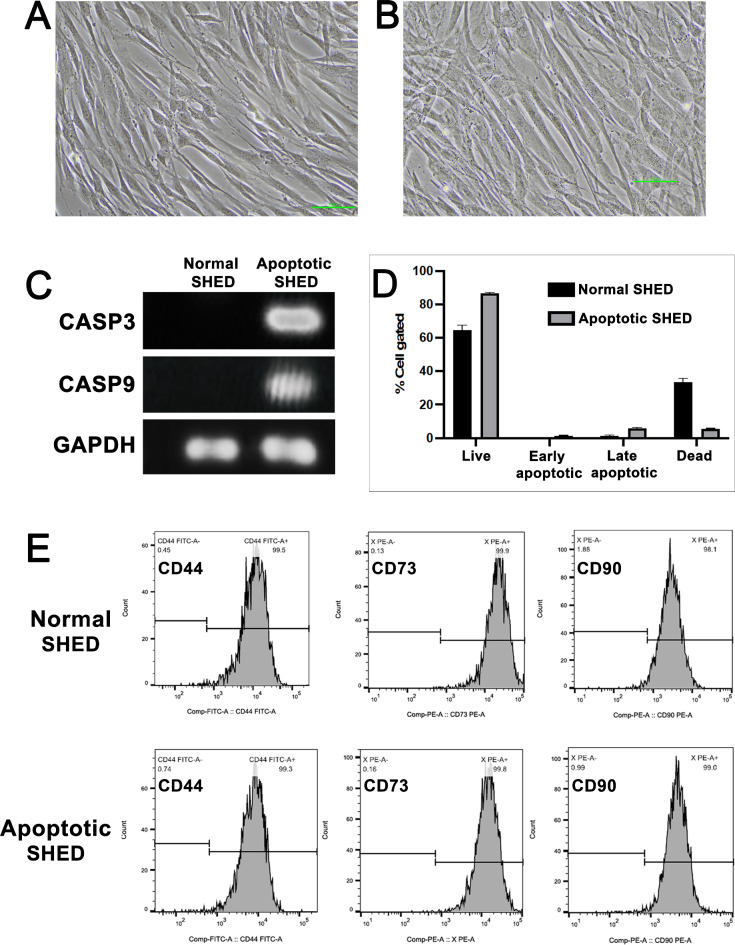

Apoptosis induction in SHED was achieved through serum starvation without medium replacement for 3 weeks. The normal and apoptosis-induced SHED were spindle shaped (Fig. 1A and B, respectively). Apoptosis induction was confirmed by assessing the expression of caspase 3 and caspase 9; no expression was observed in the normal SHED (Fig. 1C). Annexin-FITC and 7-AAD staining revealed increased apoptotic cell populations in apoptosis-induced SHED compared with those from conventional culture conditions (Fig. 1D). The apoptosis-induced SHED demonstrated increased cell viability and decreased dead cell counts than those in normal SHED.

Fig. 1.

Assessment of apoptosis induction in stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED). The morphology of normal SHED (A) and apoptotic SHED (B) observed under an inverted microscope. Scale bar = 50 μm. Gel electrophoresis for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of CASP3 and CASP9 in normal and apoptosis-induced SHED (C). Annexin V & Dead Cell Assay to evaluate apoptosis in the SHED (D). Stem cell markers (CD44, CD 73, and CD90) identified via flow cytometry (E).

Furthermore, similar to normal SHED, the apoptosis-induced SHED retained their identity as stem cells, as evidenced by the positive staining for the MSC surface markers CD44, CD73, and CD90 (Fig. 1E).

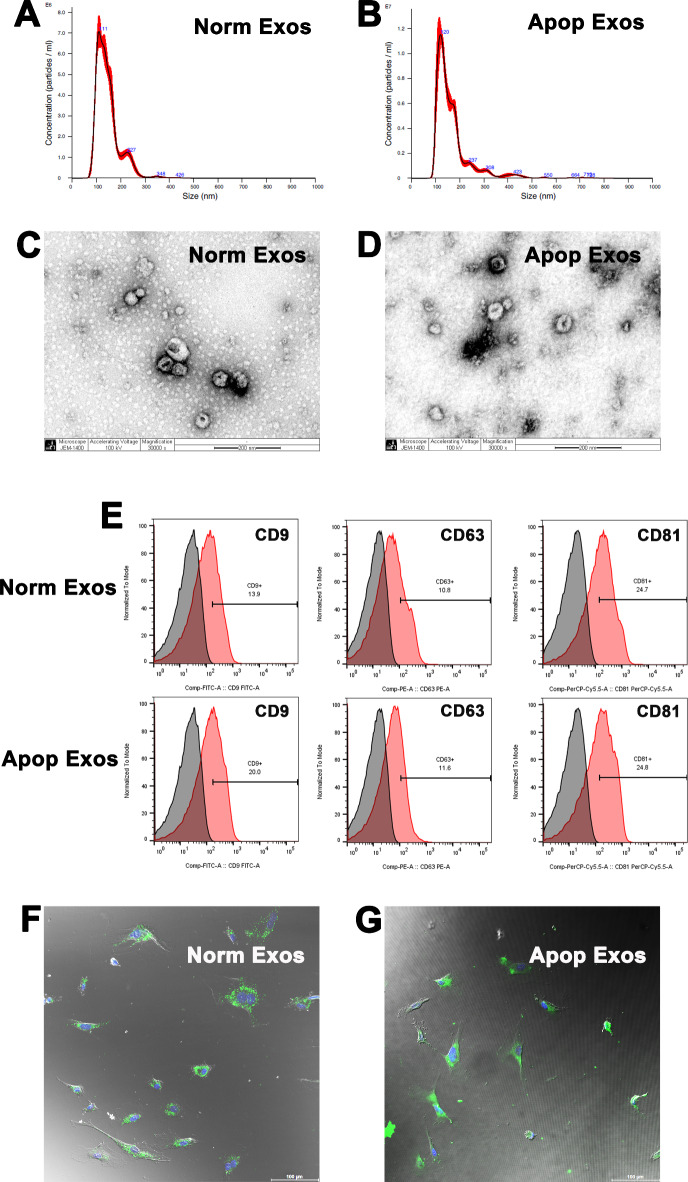

Apoptotic SHED exosomes exhibited typical characteristics

The diameters of exosomes isolated from each type of SHED-culture media ranged from 60 to 200 nm, peaking at 111 nm for normal SHED-derived exosomes (Norm Exos; Fig. 2A) and 120 nm for apoptotic SHED-derived exosomes (Apop Exos; Fig. 2B). Both types of SHED exosomes exhibited the typical cup-shaped morphology (Fig. 2C, D) and expressed the exosome-specific markers CD9, CD63, and CD81 (Fig. 2E), confirming their identity as exosomes.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of exosomes derived from apoptotic SHED. Particle size distribution of exosomes from normal SHED (A) and apoptotic SHED (B) evaluated via nanoparticle tracking. Morphology of exosomes from normal SHED (C) and apoptotic SHED (D) observed under a transmission electron microscope. Scale bar = 200 nm. Surface markers of exosomes (CD9, CD63, and CD81) analyzed via flow cytometry (E). Efficient uptake of PKH67-labeled exosomes (green) from normal SHED (F) and apoptotic SHED (G) by HUVECs detected in 4 h; the nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Additionally, PKH67-labeled SHED exosomes were internalized by endothelial cells, as evidenced by the bright green color in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 2F, G), thus indicating the efficient uptake of SHED exosomes with potential biological effects by the HUVECs.

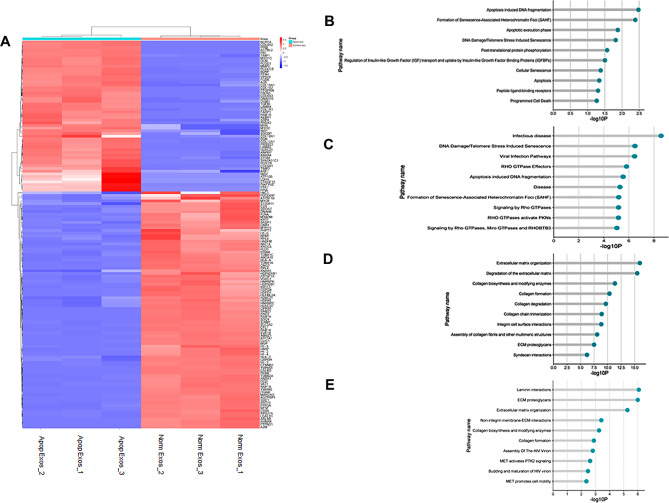

Proteomic analysis

The LC-MS analysis identified and quantified exosomal proteins in the Norm Exos and Apop Exos (Supplementary Table 2). Among the 144 differentially expressed SHED exosomal proteins, 3 were absent, 85 were downregulated, 28 were upregulated, and 28 were exclusively present in Apop Exos (Fig. 3A). Notably, the proteins absent and downregulated in Apop Exos were associated with critical pathways involved in apoptosis, programmed cell death, and cellular senescence, exemplified by histone protein groups (H1-2, H1-3, H1-4, H1-5, H2AC20, H2BC21, and H4C1), protein EVA1, and programmed cell death 6 protein (PDCD6; Fig. 3B, C; Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, the proteins present and upregulated in Apop Exos, such as aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13), 72 kDa type IV collagenase or matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), integrin beta-1 (ITGB1), and moesin (MSN; Fig. 3D, E), were associated with extracellular matrix organization, indicating positive angiogenesis.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of proteins identified in exosomes from normal and apoptotic SHED. Heat map showing the upregulated (red) and downregulated proteins (blue) in the apoptotic SHED exosomes (A). Pathway analysis highlighted the pathways unique to (B), downregulated in (C), upregulated in (D), and exclusive to (E) apoptotic SHED exosomes.

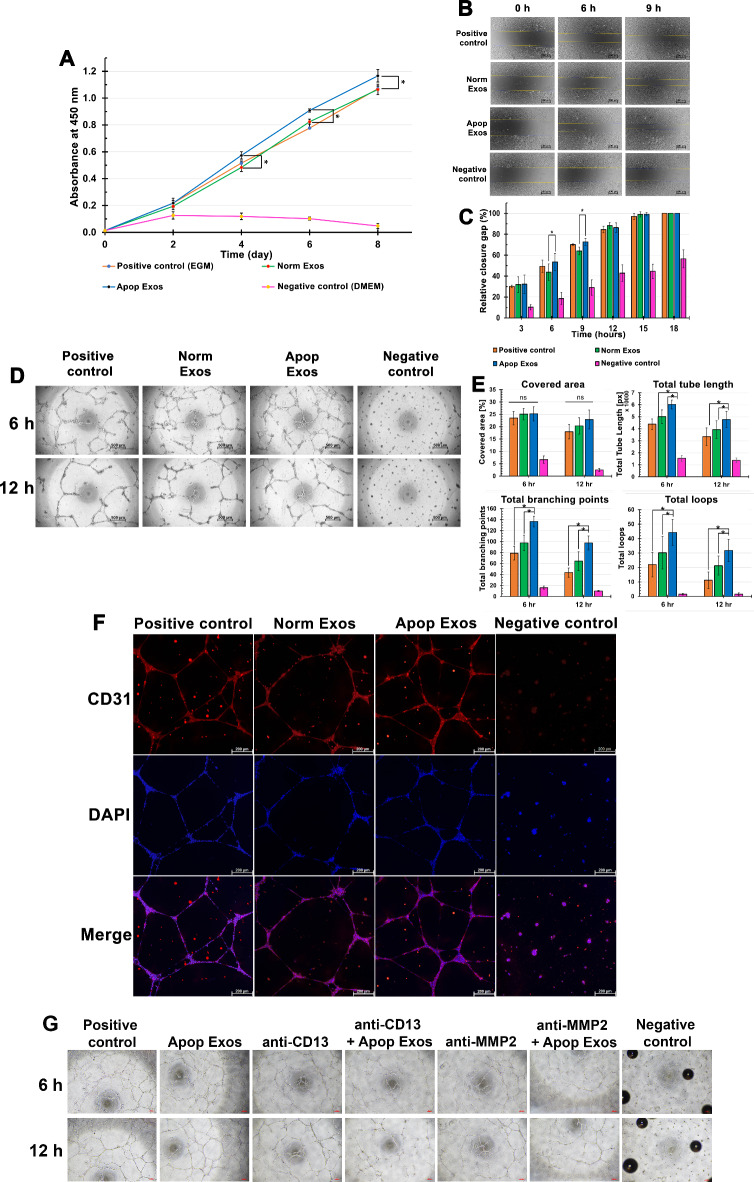

Exosomes derived from apoptotic SHED promoted angiogenesis

Proliferation assay

The HUVECs count, as depicted in Fig. 4A, exhibited continuous growth from day 0 to day 8 across all groups. HUVECs treated with Apop Exos showed significantly higher proliferation than those treated with Norm Exos and the positive controls on days 4 (p < 0.02), 6 (p < 0.02), and 8 (p < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

Promotion of angiogenesis by exosomes derived from apoptotic SHED. Graph represents the average proliferation of HUVECs measured via the CCK-8 assay at various time points. *indicates statistically significant differences between apoptotic and normal SHED exosomes at day 4 (p < 0.02), day 6 (p < 0.02), and day 8 (p < 0.01) (A). Migration of HUVECs assessed using an in vitro scratch assay (B). Scale bars = 500 μm. Quantification of gap closure (%) in B (C). * indicates statistically significant differences between apoptotic and normal SHED exosomes at 6 h (p < 0.02) and 9 h (p < 0.05). Detection of capillary-like network structures formed by HUVECs at 6 and 12 h using Matrigel tube formation (D). Scale bars = 500 μm. Quantification of tubular structures analyzed at 6 and 12 h using WimTube image analysis software (E). *indicates statistically significant differences in the total tube length (p = 0.002), total branching points (p < 0.001), and total loops (p = 0.018) between the apoptosis-induced SHED exosome group and the positive control or normal exosome groups. Immunofluorescence images of the tube network structures at 12 h with the upper panel indicating CD31 expression (red), the middle panel representing DAPI staining (blue), and the lower panel showing a merged image of CD31 and DAPI (F). Scale bars = 200 μm. Tube formation of HUVECs treated with anti-APN/CD13 and apoptotic SHED exosomes, as well as anti-MMP-2 and apoptotic SHED exosomes, showing reduced tube formation and branching. Scale bars = 100 μm (G).

Migration assay

HUVECs cultured in the positive control and Apop Exos-treated groups showed similar levels of relative wound closure at each time point (Fig. 4B). However, the Apop Exos-treated HUVECs showed significantly higher relative gap closure values than the Norm Exos-treated HUVECs at 6 h (53.55 ± 8.09 and 43.7 ± 7.82, respectively; p < 0.02) and 9 h (72.75 ± 3.41 and 64.01 ± 3.70, respectively; p < 0.05; Fig. 4C). No significant differences were observed after 9 h. HUVECs cultured in the negative control group exhibited lower levels of relative wound closure than the other groups at each time point.

Tube formation assay

At 6 h, the HUVECs in the positive and exosome-treated groups formed tubular networks, whereas no such formations were observed in the negative control (Fig. 4D). The Apop Exos group presented with denser, more connected mesh-like structures compared with those of the Norm Exos and positive control groups, which showed discontinuity in tubular formation. At 12 h, all groups showed thicker mesh-like structures with increased discontinuity. The Apop Exos-treated HUVECs maintained superior tube connectivity (Fig. 4D).

The Apop Exos group presented with significantly increased total tube length (p = 0.002), total branching points (p < 0.001), and total loops (p = 0.018) compared with those of the positive and Norm Exos groups at both time points (Fig. 4E), indicating enhanced vascular network formation.

Immunofluorescence staining with CD31 was employed to assess angiogenesis in the experimental groups (Fig. 4F). At 12 h, all groups exhibited positive staining for DAPI and CD31. The positive control and exosome-treated groups formed interconnected tube networks of elongated CD31-positive cells, whereas the negative control group showed cell clumping without tube-like structures and lower CD31 staining intensity than the positive controls.

Based on the experimental results, a preliminary assessment was conducted to explore whether proteins expressed in Apop Exos might be involved in the angiogenesis process (Fig. 4G). The study included seven experimental groups: positive control, negative control, cells treated with 10 μg/ml Apop Exos, anti-APN/CD13 (ABclonal, Woburn, MA, USA), anti-APN/CD13 combined with 10 μg/ml Apop Exos, anti-MMP-2 (ABclonal), and anti-MMP-2 combined with 10 μg/ml Apop Exos. The findings revealed that exosomes derived from SHED apoptosis induced tube formation similar to that of the positive control, with an extensive branching, mesh-like network observed. Notably, in the group where cells were treated with Apop Exos in conjunction with anti-APN/CD13, a reduction in tube formation, including both the number of tubes and branch points, became evident after 6 and 12 h of HUVEC culture (Fig. 4G). However, the addition of anti-APN/CD13 alone did not alter the angiogenic outcome at any time point. This reduction mirrored the effects observed when cells were treated with Apop Exos along with anti-MMP-2 (Fig. 4G). These results suggest that proteins expressed in exosomes from apoptosis-induced SHED, such as APN/CD13 or MMP-2, may influence the development of tube formation.

Discussion

In the present study, exosomes from apoptosis-induced SHED enhanced the angiogenic behavior of endothelial cells when deprived of serum, showing that cells under stress can contribute to tissue regeneration. The induction of apoptosis was confirmed through the genetic expression of CASP3 and CASP9, along with an increase in apoptotic populations observed via annexin-FITC and 7-AAD staining20. Additionally, we confirmed the stem cell properties of the apoptosis-induced SHED using the MSC surface markers CD44, CD73, and CD90, as described previously16, thus highlighting the role of apoptosis in healing and indicating its potential in regenerative medicine.

Serum starvation led to suppressed cellular proliferation, induced cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase, and increased apoptosis18. It has been reported that serum starvation can induce caspase-dependent apoptosis in rat cells, particularly through the intrinsic amplification loop of caspase-917. Additionally, serum starvation-induced apoptosis has been observed in oral tissue cells, such as tongue epithelial cells, through mechanisms other than the caspase cascade. In this experiment, serum starvation was applied for 3 weeks. In a pilot study, serum starvation was conducted for 2 days, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, and 5 weeks. Surviving SHED were found in every group except the 5-week group, where significant cell death was observed. After 3 weeks of starvation, SHED exhibited positive expression of CASP3 and CASP9, while other durations showed partial or no expression of these caspase genes (Supplementary file). Lorenz et al. (2023)21 demonstrated the accelerated intracellular metabolism of HUVECs due to serum starvation, which aided the cells in adapting to the energy deficiency. However, prolonged starvation led to decreased intracellular metabolism and lower mitochondrial activity. Similarly22, subjected SHED to glucose and serum deprivation for 2 weeks and reported increased late apoptosis; however, they maintained cell vitality with a halted cell cycle. However, in the current study, SHED cultured without serum for 3 weeks exhibited increased cell viability compared with that of normal SHED, despite a decrease in the dead cell count. This observation indicates a potential adaptive mechanism employed by the cells to survive under harsh conditions. The lack of nutrients initially caused oxidative stress, disrupting cellular balance, triggering signaling pathways while altering metabolism. It induced the production of reactive oxygen species, creating an oxidative stress environment. Moreover, despite being under stress, the cells showed negligible cell death compared with those at basal conditions, suggesting an adaptive strategy for enduring oxidative stress while maintaining viability23. Although transplanted MSCs typically undergo extensive apoptosis within 24 h, this process enhances tissue regeneration and homeostasis through the release of survival proteins and immunomodulatory molecules2,24. Apoptotic exosomes from HUVECs induced by serum starvation positively affect endothelial cell angiogenesis via the NF-κB signaling pathway, resulting in reduced apoptosis, improved wound closure, and enhanced angiogenic activity in exposed HUVECs25,26. The results from apoptotic exosomes in our study may differ due to variations in the source of parent cells and cultivation processes.

Multiple studies have affirmed the therapeutic benefits of SHED, utilizing both cell-based and cell-free methodologies14,27. Exosomes derived from apoptosis-induced SHED exhibited exosome profiles consistent with the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2018 guidelines (MISEV2018) and with the findings of other investigations8,9, resembling those derived from healthy SHED. Analysis of protein profiles revealed that exosomes derived from apoptotic SHED exhibited a downregulation in proteins associated with apoptosis, programmed cell death, and cellular senescence, including histone proteins, compared with those in exosomes derived from normal SHED. Extracellular histones induce autophagy and apoptosis in HUVECs in a dose-dependent manner28. Histone can regulate the expression of EVA1 protein, which is associated with lysosome and the endoplasmic reticulum and linked to autophagy and apoptosis. Downregulation of EVA1 protein expression was also observed in this study. In a recent study, silencing of EVA1 decreased apoptosis, permeability, and inflammatory marker expression in endothelial cells29. Additionally, exosomes from apoptotic SHED showed decreased expression of the proapoptotic protein PDCD6. In one study, PDCD6 was reported to suppress proliferation and invasion by inhibiting the phosphorylation of signaling regulators downstream of PI3K, Akt, and mTOR and decreasing cyclin D1 expression30. These protein contents reflect the cellular adaptations to microenvironmental changes and are transmitted to exosome cargoes. Overall, these findings may support the findings of the current study, wherein a higher number of live cells were observed in the apoptotic SHED than in normal SHED. The results of this study indicate a potential mechanism by which SHED secrete exosomes for survival in adverse conditions.

The proteins present and upregulated in the apoptosis-induced SHED exosomes were predominantly associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) modulation. The ECM plays a crucial role in signaling and regulating angiogenesis, supporting endothelial cell adhesion, survival, and migration during the formation of new blood vessels31,32. This observation aligns with the findings of Tratwal et al. (2015), who demonstrated that induction of MSCs via serum starvation led to alterations in growth factors, matricellular proteins, and proangiogenic paracrine mechanisms crucial for vasculoprotection, extracellular matrix remodeling, and blood vessel maturation33. Furthermore, APN/CD13 was upregulated in the apoptotic SHED exosomes, highlighting its potential significance in endothelial morphogenesis during angiogenesis in the current study. In one study, RNA interference (RNAi) targeting APN/CD13 inhibited capillary tube formation and reduced the cellular adhesion of HUVECs to various molecules, including type IV collagen, type I collagen, and fibronectin34. The MMP family is essential for connective tissue turnover during wound healing and neovascularization35. MMP2 can cleave type I and type IV collagen, the key components of the basement membranes of blood vessels. Additionally, MMP2 has been shown to promote the proliferation and vascular angiogenesis of endothelial cells in vitro36. Elevated MMP2 protein expression was observed in the apoptotic SHED exosomes in the current study. Based on the preliminary experimental results, it appears that proteins such as APN/CD13 and MMP-2, which were found to be upregulated in apoptosis-induced SHED exosomes compared with normal SHED exosomes, play a significant role in influencing tube formation in HUVECs. The observed reduction in tube formation, particularly in the presence of anti-APN/CD13 or anti-MMP-2 alongside Apop Exos, suggests that these proteins may be key mediators in the angiogenesis process. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the precise mechanisms through which these proteins contribute to the observed effects, potentially opening new avenues for understanding exosome-mediated regulation of angiogenesis. A significant upregulation of integrin beta 1 and MSN was observed within the apoptotic SHED exosomes, indicating their potential involvement in angiogenesis, a process intricately governed by vascular endothelial growth factor. Integrin beta 1 facilitates cellular adhesion to the extracellular matrix, whereas MSN modulates cell shape and motility, potentially activating angiogenesis via the VEGFR2-RhoJ-PAK2/4-ERK pathway37. The collective action of exosomal proteins underscores their therapeutic relevance in addressing angiogenic-related disorders38.

In the current study, HUVECs cultured with apoptosis-induced SHED exosomes showed significantly higher proliferation and migratory rates than those cultured with normal SHED exosomes. The apoptosis-induced SHED exosome-treated group also showed increased tubular structure formation, with enhanced network continuity over a 12 h period. These findings suggest that apoptosis-induced SHED exosomes contribute to endothelial cell angiogenesis by promoting neovascularization, potentially through exosomal proteins. A promising link between the apoptosis-induced SHED exosomes and their protein profiles was observed, implicating these proteins in the angiogenic properties of derived exosomes. However, further studies are required to validate these findings in both groups. While our results primarily focused on exosomal proteins, exosomes contain heterogeneous bioactive molecules, such as exosomal RNAs (miRNAs and mRNAs), which are known to play significant roles13,26,39. Thus, proteins represent only one aspect of the multifaceted nature of exosomes and should be considered alongside other bioactive factors when describing their potential. Moreover, the underlying mechanism of apoptotic exosomes and the key contributors to the observed positive angiogenesis in HUVECs remain unclear. The results are limited to the specific cell types studied, SHED and HUVECs, and may not be applicable to other cell types. Therefore, future research should aim to clarify the precise mechanisms, identify key mediators, and explore different apoptosis induction protocols across various cell types to fully realize the potential of exosome applications.

In conclusion, apoptosis-induced SHED exosomes enhanced angiogenesis in HUVECs by promoting proliferation, migration, and tubular structure formation. Proteomic analysis revealed distinct protein profile alterations related to apoptosis and angiogenesis. These findings indicate the potential for using apoptosis induction as a strategy to enhance exosome production, which may prove beneficial for dental tissue regeneration.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Mahidol University (Fundamental Fund: fiscal year 2023 by National Science Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF)) and National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT): High-Potential Research Team Grant Program. Moreover, the authors thank Enago (www.enago.com) for the English language review.

Author contributions

T.S. contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. C.C. contributed to design, data acquisition, and analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. L.T. contributed to data acquisition and analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. W.C. contributed to data acquisition and analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. K.I. contributed to design, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. K.P. contributed to design, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. H.S. contributed to conception, design, analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD052291. [Project name: Exosome from apoptotic dental stem cells, the Unique link: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/review-dataset/1f7fca69498140b6aed1311fc08daad9] (Token: PQQuALi5gtgE).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Misra, A., Rai, S. & Misra, D. Functional role of apoptosis in oral diseases: an update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol.20(3), 491–496 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pérez-Garijo, A. When dying is not the end: apoptotic caspases as drivers of proliferation. Semin Cell. Dev. Biol.82, 86–95 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, H. et al. Donor MSCs release apoptotic bodies to improve myocardial infarction via autophagy regulation in recipient cells. Autophagy. 16(12), 2140–2155 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryoo, H. D. & Bergmann, A. The role of apoptosis-induced proliferation for regeneration and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol.4(8), a008797 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Genova, T. et al. The Crosstalk between osteodifferentiating stem cells and endothelial cells promotes angiogenesis and bone formation. Front. Physiol.10, 1291 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diomede, F. et al. Functional relationship between Osteogenesis and Angiogenesis in tissue regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21(9) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Yin, Z. et al. A novel method for banking stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth: lentiviral TERT immortalization and phenotypical analysis. Stem Cell. Res. Ther.7, 50 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, M., Li, J., Ye, Y., He, S. & Song, J. SHED-derived conditioned exosomes enhance the osteogenic differentiation of PDLSCs via wnt and BMP signaling in vitro. Differentiation. 111, 1–11 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu, J. et al. Exosomes secreted by stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous Teeth promote alveolar bone defect repair through the regulation of Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.5(7), 3561–3571 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Moshy, S. et al. Dental Stem cell-derived Secretome/Conditioned medium: the future for regenerative therapeutic applications. Stem Cells Int.2020, 7593402 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper, L. F., Ravindran, S., Huang, C. C. & Kang, M. A role for exosomes in Craniofacial tissue Engineering and Regeneration. Front. Physiol.10, 1569 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borges, F. T. et al. TGF-β1-containing exosomes from injured epithelial cells activate fibroblasts to initiate tissue regenerative responses and fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.24(3), 385–392 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, P. et al. Exosomes Derived from Hypoxia-conditioned stem cells of human deciduous exfoliated Teeth Enhance Angiogenesis via the transfer of let-7f-5p and miR-210-3p. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.10, 879877 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sunartvanichkul, T. et al. Stem cell-derived exosomes from human exfoliated deciduous teeth promote angiogenesis in hyperglycemic-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Appl. Oral Sci.31, e20220427 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakarla, R., Hur, J., Kim, Y. J., Kim, J. & Chwae, Y. J. Apoptotic cell-derived exosomes: messages from dying cells. Exp. Mol. Med.52(1), 1–6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonmanee, T., Thonabulsombat, C., Vongsavan, K. & Sritanaudomchai, H. Differentiation of stem cells from human deciduous and permanent teeth into spiral ganglion neuron-like cells. Arch. Oral Biol.88, 34–41 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schamberger, C. J., Gerner, C. & Cerni, C. Caspase-9 plays a marginal role in serum starvation-induced apoptosis. Exp. Cell. Res.302(1), 115–128 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, Y. et al. Serum starvation-induces down-regulation of Bcl-2/Bax confers apoptosis in tongue coating-related cells in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep.17(4), 5057–5064 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benedikter, B. J. et al. Ultrafiltration combined with size exclusion chromatography efficiently isolates extracellular vesicles from cell culture media for compositional and functional studies. Sci. Rep.7(1), 15297 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satitmanwiwat, S. et al. The scorpion venom peptide BmKn2 induces apoptosis in cancerous but not in normal human oral cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 84, 1042–1050 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenz, M. et al. Serum starvation accelerates intracellular metabolism in endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24(2) (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Pawar, M. et al. Glucose and serum deprivation led to altered proliferation, differentiation potential and AMPK activation in stem cells from human deciduous tooth. J. Pers. Med.12(1) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.White, E. Z. et al. Serum deprivation initiates adaptation and survival to oxidative stress in prostate cancer cells. Sci. Rep.10(1), 12505 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu, Y. et al. Emerging understanding of apoptosis in mediating mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Cell. Death Dis.12(6), 596 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Migneault, F. et al. Apoptotic exosome-like vesicles regulate endothelial gene expression, inflammatory signaling, and function through the NF-κB signaling pathway. Sci. Rep.10(1), 12562 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brodeur, A. et al. Apoptotic exosome-like vesicles transfer specific and functional mRNAs to endothelial cells by phosphatidylserine-dependent macropinocytosis. Cell. Death Dis.14(7), 449 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishino, Y. et al. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) enhance wound healing and the possibility of novel cell therapy. Cytotherapy. 13(5), 598–605 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibañez-Cabellos, J. S. et al. Extracellular histones activate autophagy and apoptosis via mTOR signaling in human endothelial cells, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) -. Mol. Basis Disease. 1864(10), 3234–3246 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canham, L. et al. EVA1A (Eva-1 Homolog A) promotes endothelial apoptosis and inflammatory activation under disturbed Flow Via Regulation of Autophagy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.43(4), 547–561 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rho, S. B. et al. Programmed cell death 6 (PDCD6) inhibits angiogenesis through PI3K/mTOR/p70S6K pathway by interacting of VEGFR-2. Cell. Signal.24(1), 131–139 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hynes, R. O. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science. 326(5957), 1216–1219 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, P., Takai, K., Weaver, V. M. & Werb, Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol.3(12) (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Tratwal, J. et al. Influence of vascular endothelial growth factor stimulation and serum deprivation on gene activation patterns of human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther.6(1), 62 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukasawa, K. et al. Aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) is selectively expressed in vascular endothelial cells and plays multiple roles in angiogenesis. Cancer Lett.243(1), 135–143 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stetler-Stevenson, W. G. Matrix metalloproteinases in angiogenesis: a moving target for therapeutic intervention. J. Clin. Invest.103(9), 1237–1241 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, Y. et al. MMP-2 and MMP-9 contribute to the angiogenic effect produced by hypoxia/15-HETE in pulmonary endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol.121, 36–50 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, M. et al. RhoJ facilitates angiogenesis in glioblastoma via JNK/VEGFR2 mediated activation of PAK and ERK signaling pathways. Int. J. Biol. Sci.18(3), 942–955 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abudula, M. et al. Ectopic endometrial cell-derived Exosomal Moesin induces Eutopic Endometrial Cell Migration, enhances angiogenesis and cytosolic inflammation in Lesions contributes to endometriosis progression. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.10, 824075 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, M. et al. SHED aggregate exosomes shuttled miR-26a promote angiogenesis in pulp regeneration via TGF-β/SMAD2/3 signalling. Cell. Prolif.54(7), e13074 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [1] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD052291. [Project name: Exosome from apoptotic dental stem cells, the Unique link: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/review-dataset/1f7fca69498140b6aed1311fc08daad9] (Token: PQQuALi5gtgE).