Abstract

Background

Coronary computed tomography angiography–derived fractional flow reserve (FFRCT) is a per-vessel index reflecting cumulative hemodynamic burden while coronary events occur in focal lesions.

Objectives

The authors sought to evaluate the additive prognostic value of the local gradient of FFRCT (FFRCT gradient) in addition to FFRCT to predict future coronary events.

Methods

The current study included 245 patients (634 vessels) who underwent coronary computed tomography angiography within 6 to 36 months before the index angiography, of which 209 vessels had future coronary events and 425 vessels did not. Future coronary events were defined as a composite of vessel-specific myocardial infarction or urgent revascularization during a mean interval of 1.5 years. Pre-existing disease patterns were classified according to FFRCT of ≤0.80 and FFRCT gradient of ≥0.025/mm.

Results

Both FFRCT (per 0.01 decrease; adjusted HR: 1.040; 95% CI: 1.029-1.051; P < 0.001) and FFRCT gradient (per 0.01 increase; adjusted HR: 1.144; 95% CI: 1.101-1.190; P < 0.001) were significantly associated with the risk of future coronary events. Lesions with FFRCT gradient of ≥0.025/mm showed significantly higher risk of future coronary events than those with FFRCT gradient of <0.025/mm in both the FFRCT >0.80 (49.2% vs 30.1%; HR: 2.069; 95% CI: 1.265-3.385; P = 0.004) and FFRCT ≤0.80 groups (60.9% vs 38.3%; HR: 1.988; 95% CI: 1.317-2.999; P =0 .001). Adding FFRCT gradient into the model with FFRCT alone showed significantly increased predictability of future coronary events (global chi-square: 45.8 vs 39.9; P = 0.015).

Conclusions

Patients with high FFRCT gradient showed increased risk of future coronary events irrespective of FFRCT. Integrating both FFRCT and FFRCT gradient showed incremental predictability of future coronary events compared with FFRCT alone. (Prediction and Validation of Clinical Course of Coronary Artery Disease With CT-Derived Non-Invasive Hemodynamic Phenotyping and Plaque Characterization [DESTINY Study]; NCT04794868)

Key Words: coronary atherosclerotic disease, coronary CT angiography, cumulative burden, local severity, prognosis

Central Illustration

Coronary atherosclerotic disease (CAD) is caused by atherosclerotic plaque formation and progression, which leads to coronary artery stenosis and myocardial ischemia.1 Treatment of CAD has 2 key components: percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which is a focal treatment to relieve stenosis, and pharmacotherapies, which are systemic treatments for event prevention.2,3 Previous randomized controlled trials demonstrated the benefits of fractional flow reserve (FFR)–guided PCI, and based on these trials, FFR is endorsed as a class 1A recommendation in decision making for PCI.3,4

However, it should be noted that FFR is a per-vessel index that reflects the cumulative hemodynamic burden of CAD in a target vessel, whereas PCI is a per-lesion treatment that relieves inducible myocardial ischemia related to a focal stenosis. Therefore, patients with diffuse CAD could have an FFR of ≤0.80, and angiographically successful PCI in these patients could result in residual ischemia with suboptimal clinical outcomes.5, 6, 7 Conversely, some patients with an FFR of >0.80 in the target vessel might have focal disease with hemodynamic significance, which might benefit from PCI.8,9 Recent studies have shown that the prognosis of patients undergoing PCI can be better discriminated when integrating FFR gradient, reflecting per-lesion local severity, in addition to FFR.7,10 However, there are limited data on whether integrating FFR gradient in addition to FFR can better stratify the risk of future coronary events in medically treated patients.

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA)–derived FFR (FFRCT) is a per-vessel index reflecting cumulative hemodynamic burden, and a recent study demonstrated that FFRCT could be a prognostic indicator, as with invasive FFR.11,12 The local gradient of FFRCT (FFRCT gradient) can be easily extracted from the virtual pullback curve of FFRCT. Therefore, FFRCT technology can provide an alternative platform for the comprehensive analysis of disease patterns with fewer technical limitations. In this regard, the current study sought to evaluate the additive prognostic value of FFRCT gradient in addition to FFRCT to predict future coronary events.

Methods

Study design and population

The study population was derived from DESTINY (Prediction and Validation of Clinical Course of Coronary Artery Disease With CT-Derived Noninvasive Hemodynamic Phenotyping and Plaque Characterization; NCT04794868). DESTINY was designed to evaluate prognostic implications of comprehensive anatomic and physiologic assessment using coronary CTA and computational fluid dynamics (CFD). Briefly, DESTINY enrolled 2 separate patient populations (a coronary event cohort and a negative control cohort) (Figure 1). The coronary event cohort included consecutive patients who underwent coronary CTA within 6 to 36 months before PCI for acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The negative control cohort included age-/sex-matched patients who had undergone coronary CTA within 6 to 36 months before invasive coronary angiography for stable angina but did not undergo PCI at the time of angiography. In both cohorts, coronary CTA was performed at the discretion of each physician as a routine clinical evaluation for suspected CAD.

Figure 1.

Study Flow

The current study enrolled 2 separate patient populations (the coronary event cohort and the negative control cohort). The coronary event cohort included consecutive patients who underwent coronary CTA within 6 to 36 months before PCI for ACS. The negative control cohort included age-/sex-matched patients who had undergone coronary CTA within 6 to 36 months before invasive coronary angiography for stable angina but did not undergo PCI at the time of angiography. A total of 245 patients (181 and 64 patients from the coronary event and negative control cohorts, respectively) and 634 vessels (209 vessels were culprit vessels, and 425 vessels were not related to a coronary event) were selected for the current study. ACS = acute coronary syndrome(s); CCTA = coronary computed tomography angiography; CFD = computational fluid dynamics; CTA = computed tomography angiography; FFRCT = coronary CTA–derived fractional flow reserve; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

In the coronary event cohort, patients without a clear culprit lesion on invasive angiography, intravascular ultrasound, or optical coherence tomography were excluded. Also, patients with in-stent restenosis as the cause of ACS, previous history of coronary artery bypass graft surgery, or type 2 myocardial infarction (MI) were excluded from the study. In both cohorts, vessels with suboptimal image quality for anatomic or physiologic analysis of plaque characteristics, including stents before coronary CTA, were excluded by the core laboratories for coronary CTA (Elucid Bioimaging, Inc) and CFD (Shanghai Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases). The current study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Analysis of physiologic plaque characteristics in coronary CTA

Coronary CTA images were obtained in accordance with the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines on Performance of Coronary CTA with a 64-channel scanner (GE Healthcare) or 128-channel dual-source scanner platforms (Siemens Medical System) with electrocardiographic gating.13 A standardized protocol for heart rate control with a β-blocker and sublingual nitroglycerin was used.

Physiologic parameters derived from coronary CTA were analyzed in a blinded fashion at a CFD core laboratory (Shanghai Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases) using a commercial offline software system (RuiXin-FFR, version 1.0, Raysight Medical), which was approved for clinical use by the National Medical Products Administration of China.14,15 Detailed methods of 3-dimensional model reconstruction and CFD-based FFRCT calculation are described in the Supplemental Appendix. Briefly, coronary models were constructed using segmentation algorithms that extract the luminal surface of the epicardial coronary arteries and branches. Coronary flow and pressure were computed by solving the Navier-Stokes equations, assuming that blood is approximated as a newtonian fluid. Boundary conditions for hyperemia were derived from myocardial mass, vessel sizes at each outlet, and the response of the microcirculation to adenosine. Last, physiologic parameters were solved by CFD-based FFRCT calculation. For the current study, 2 physiologic parameters were used: 1) FFRCT; and 2) FFRCT gradient. First, FFRCT was defined as the ratio of the mean downstream coronary pressure (Pd) and the aortic pressure (Pa) derived from the CFD analysis under a simulated hyperemic condition. Second, FFRCT gradient was defined as the peak value of instantaneous FFRCT gradient per unit length in a vessel, which is an index reflecting the local severity of a lesion.7,16 Lesions with a stenosis diameter of >30% were selected for computation of FFRCT gradient.

Analysis of anatomic plaque characteristics in coronary CTA

Coronary CTA images were analyzed for anatomic plaque characteristics in a blinded fashion using histologically validated plaque quantification software (vascuCAP, Clinical Edition, Elucid Bioimaging) at a coronary CTA core laboratory (Elucid Bioimaging, Inc).17 For the assessment of anatomic severity, the percentage of total aggregate plaque volume (%TAPV), percentage of plaque volume (%PV), stenosis diameter, lesion length, maximum plaque burden, and minimum lumen area were measured. Plaque burden was defined as the ratio of wall area divided by overall vessel area.17,18 The %TAPV and %PV by composition in the whole vessel or lesion were calculated as the ratio of plaque volume divided by the vessel or lesion volume, respectively. For the assessment of anatomic plaque characteristics, whole vessel and lesion tissue characterizations were performed by categorizing the vessel wall into different components: calcified tissue, lipid-rich necrotic core, intraplaque hemorrhage, matrix, or perivascular adipose tissue.18 In addition, the presence of the following high-risk plaque characteristics was analyzed according to the definitions from previous studies: 1) low-attenuation plaque (average density: ≤30 HU); 2) positive remodeling (lesion diameter/reference diameter: ≥1.1); 3) napkin-ring sign (ring-like attenuation pattern with peripheral high-attenuation tissue surrounding a central lower-attenuation portion); and 4) spotty calcification (average density: >130 HU; diameter: <3 mm).8,15,19 Lesions with a stenosis diameter of >30% were selected for anatomic plaque characterization. In cases of multiple lesions in the same target vessel, the lesion with the greatest-diameter stenosis was selected as the representative lesion.

Classification of pre-existing disease patterns according to FFRCT and FFRCT gradient

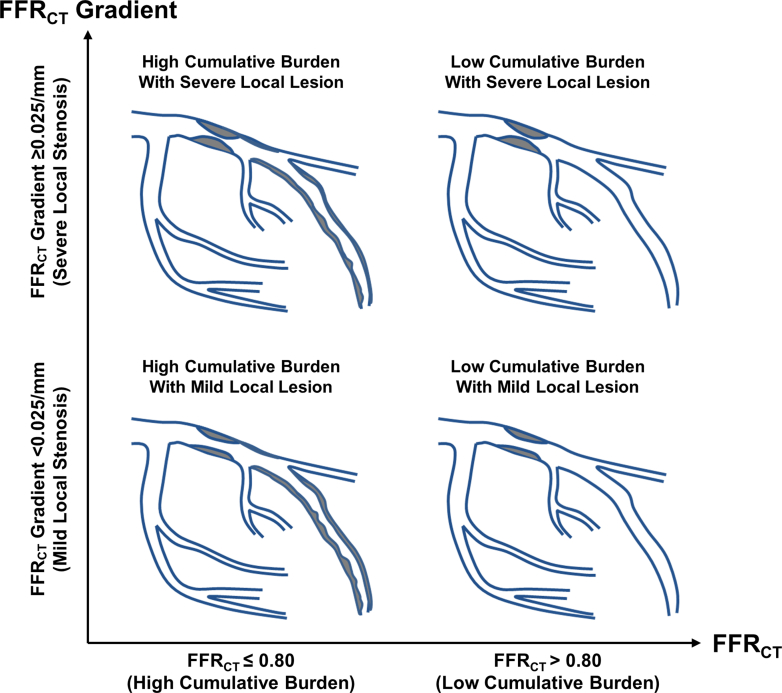

Receiver-operating characteristics curve analysis by the Youden index method was used to obtain the optimal cutoff value of FFRCT and FFRCT gradient to discriminate the occurrence of future coronary events. In the current study, the optimal cutoff values of FFRCT and FFRCT gradient were 0.80 and 0.025/mm, respectively. Based on FFRCT (≤0.80 vs >0.80, respectively) and FFRCT gradient (≥0.025/mm vs <0.025/mm, respectively), vessels were classified into 4 groups according to pre-existing disease patterns of CAD using FFRCT, reflecting the per-vessel cumulative burden of CAD, and FFRCT gradient, reflecting the per-lesion local severity of CAD (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pre-Existing Disease Patterns According to FFRCT and FFRCT Gradient

The cumulative burden and local severity of CAD were assessed by FFRCT in the target vessel and FFRCT gradient in the target lesion, respectively. Using FFRCT and FFRCT gradient, vessels were classified into 4 groups. CAD = coronary atherosclerotic disease; FFRCT = coronary computed tomography angiography–derived fractional flow reserve.

Data collection and clinical outcome

Clinical data were collected by reviewing electronic medical records. All invasive coronary angiograms at future coronary events were analyzed, and culprit lesions were identified by 2 experienced interventional cardiologists at the core laboratory (Samsung Medical Center) who were blinded to the coronary CTA results. Events were adjudicated at the vessel level. In detail, the events were adjudicated by reviewing invasive angiography of the same vessels as each vessel analyzed by coronary CTA. The primary outcome was the occurrence of future coronary events, defined as a composite of vessel-specific MI or urgent revascularization. The definitions of clinical outcomes were in accordance with the Academic Research Consortium.20 Acute MI was defined according to the universal definition of MI.21

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as number and relative frequency (percentage). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (IQR) according to distribution evaluated by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Data were analyzed on a per-patient basis for clinical characteristics and on a per-vessel basis for anatomic and physiologic plaque characteristics and vessel-specific clinical outcomes. For per-patient analyses, Student’s t-test and the chi-square test were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. For per-vessel analyses, a generalized estimating equation with linear model type and independent working correlation structure was used to adjust intrasubject variability among vessels from the same patient. Correlations between anatomic and physiologic parameters were tested using Pearson or Spearman’s correlation coefficient, according to their distributions.

The cumulative incidence of future coronary events is presented as Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared using a log-rank test. The start date was set as the day when coronary CTA was performed, and the event or censor date was set as the day when invasive coronary angiography was performed. To adjust for the interrogated vessels within the same patient, multivariable marginal Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate the adjusted HR (HRadj) and 95% CI. Adjusted covariables were age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and current smoker. The assumption of proportionality was assessed graphically using a log-minus-log plot, and all Cox proportional hazards models satisfied the proportional hazards assumption. The association between physiologic parameters and risk of primary outcome was graphically presented with a penalized spline with 3 degrees of freedom.22 The incremental predictability of FFRCT gradient for future coronary events in addition to FFRCT was evaluated using global chi-square estimated by the likelihood ratio test. All analyses were 2-sided, and P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients and vessels

A total of 245 patients and 617 vessels from DESTINY were selected for the current study (Figure 1). Among them, 181 (73.9%) patients were from the coronary event cohort and 64 (26.1%) patients were from negative control cohort. Of the 469 vessels included in the coronary event cohort, 209 were culprit and 260 were nonculprit vessels. Considering that 165 vessels from the negative control cohort were included, a total of 425 vessels were not related to a coronary event. The mean age was 65.6 ± 10.3 years, and 79.6% of patients were men (Table 1). The mean interval between coronary CTA and invasive coronary angiography was 1.5 ± 0.7 years. Although there were mostly no significant differences in demographics, cardiovascular comorbidities, and medical treatment between coronary event and negative control patients, vessels with coronary events showed significantly higher-diameter stenosis, plaque burden, %TAPV, and %PV as well as lower minimum lumen area than vessels not related to a coronary event (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical and Lesion Characteristics of the Study Population

| Total Patients (N = 245) | Coronary Event Patients (n = 181) | Negative Control Patients (n = 64) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y | 65.6 ± 10.3 | 65.2 ± 10.7 | 66.5 ± 9.3 | 0.446 |

| Male | 195 (79.6) | 145 (80.1) | 50 (78.1) | 0.874 |

| Coronary CTA to ICA interval, y | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 0.157 |

| Clinical presentation | <0.001 | |||

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 11 (4.5) | 11 (6.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 26 (10.6) | 26 (14.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Unstable angina | 144 (58.8) | 144 (79.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Stable angina | 64 (26.1) | 0 (0.0) | 64 (100.0) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 177 (72.2) | 130 (71.8) | 47 (73.4) | 0.932 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 145 (59.2) | 107 (59.1) | 38 (59.4) | 0.999 |

| Dyslipidemia | 104 (42.4) | 74 (40.9) | 30 (46.9) | 0.492 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 17 (6.9) | 13 (7.2) | 4 (6.2) | 0.999 |

| Current smoker | 48 (19.6) | 36 (19.9) | 12 (18.8) | 0.989 |

| History of percutaneous coronary intervention | 32 (13.1) | 31 (17.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0.003 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 15 (6.1) | 13 (7.2) | 2 (3.1) | 0.390 |

| History of cerebrovascular accident | 34 (13.9) | 24 (13.3) | 10 (15.6) | 0.795 |

| History of peripheral vascular disease | 16 (6.5) | 11 (6.1) | 5 (7.8) | 0.850 |

| Medical treatment after coronary CTA before clinical event | ||||

| Antiplatelet agent | 186 (75.9) | 141 (77.9) | 45 (70.3) | 0.294 |

| ACEI or ARB | 112 (45.7) | 82 (45.3) | 30 (46.9) | 0.943 |

| β-Blocker | 94 (38.4) | 72 (39.8) | 22 (34.4) | 0.539 |

| Calcium-channel blocker | 91 (37.1) | 66 (36.5) | 25 (39.1) | 0.826 |

| Statin | 165 (67.3) | 122 (67.4) | 43 (67.2) | 0.999 |

| Ezetimibe | 8 (3.3) | 7 (3.9) | 1 (1.6) | 0.629 |

| Echocardiographic findings | ||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 62.4 ± 9.8 | 62.0 ± 10.3 | 63.4 ± 8.5 | 0.401 |

| Lesion Characteristics | Total Vessels (N = 634) | Coronary Event Vessels (n = 209) | No Event Vessels (n = 425) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interrogated vessels | <0.001 | |||

| Left anterior descending artery | 235 (37.1) | 106 (50.7) | 129 (30.4) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 185 (29.2) | 45 (21.5) | 140 (32.9) | |

| Right coronary artery | 214 (33.8) | 58 (27.8) | 156 (36.7) | |

| Anatomic severity | ||||

| Diameter stenosis, % | 49.7 ± 24.2 | 56.5 ± 22.1 | 46.1 ± 24.6 | <0.001 |

| Lesion length, mm | 22.7 ± 17.3 | 25.2 ± 17.4 | 21.4 ± 17.1 | 0.063 |

| Maximum plaque burden, % | 82.3 ± 11.9 | 85.7 ± 10.0 | 80.5 ± 12.4 | <0.001 |

| Minimum lumen area, mm2 | 2.19 ± 1.86 | 1.68 ± 1.45 | 2.46 ± 1.99 | <0.001 |

| Anatomic plaque characteristics | ||||

| Total aggregate plaque volume in vessel, % | 48.7 ± 7.6 | 50.2 ± 7.9 | 48.0 ± 7.4 | 0.003 |

| Plaque volume in lesion, % | 58.8 ± 8.9 | 61.0 ± 8.4 | 57.6 ± 9.0 | 0.001 |

| Calcified volume in lesion, % | 11.5 ± 8.1 | 10.6 ± 8.0 | 12.0 ± 8.1 | 0.125 |

| Lipid-rich necrotic core volume in lesion, % | 0.5 ± 1.2 | 0.7 ± 1.4 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.104 |

| Intraplaque hemorrhage volume in lesion, % | 1.5 ± 2.8 | 1.8 ± 3.3 | 1.3 ± 2.5 | 0.112 |

| Physiologic plaque characteristics | ||||

| FFRCT | 0.80 ± 0.13 | 0.75 ± 0.14 | 0.82 ± 0.11 | <0.001 |

| FFRCT gradient (dFFRCT/ds), per mm | 0.026 ± 0.027 | 0.035 ± 0.031 | 0.021 ± 0.023 | <0.001 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; CTA = computed tomography angiography; FFRCT = fractional flow reserve by coronary computed tomography angiography; ICA = invasive coronary angiography.

Association between anatomic and physiologic plaque characteristics

FFRCT showed significant correlation with anatomic parameters of stenosis severity, including %TAPV, %PV, stenosis diameter, lesion length, maximum plaque burden, and minimum lumen area (Supplemental Figure 1). Similarly, FFRCT gradient also showed significant, but modest, correlation with those anatomic variables (Supplemental Figure 2). According to FFRCT and FFRCT gradient, pre-existing disease patterns were classified into the 4 groups (Figure 2). There were significant differences in %TAPV, %PV, stenosis diameter, lesion length, maximum plaque burden, and minimum lumen area among the 4 groups (Table 2, Supplemental Figure 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of Plaque Characteristics According to Pre-Existing Disease Patterns by FFRCT and FFRCT Gradient

| Local Severity | FFRCT Gradient <0.025/mm |

FFRCT Gradient ≥0.025/mm |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFRCT >0.80 (n = 311) | FFRCT ≤0.80 (n = 107) | FFRCT >0.80 (n = 41) | FFRCT ≤0.80 (n = 175) | ||

| Interrogated vessels | <0.001 | ||||

| Left anterior descending artery | 93 (29.9) | 31 (29.0) | 19 (46.3) | 92 (52.6) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 99 (31.8) | 43 (40.2) | 13 (31.7) | 30 (17.1) | |

| Right coronary artery | 119 (38.3) | 33 (30.8) | 9 (22.0) | 53 (30.3) | |

| Anatomic severity | |||||

| Diameter stenosis, % | 40.7 ± 23.3 | 53.6 ± 23.4 | 47.8 ± 26.7 | 61.0 ± 20.2 | <0.001 |

| Lesion length, mm | 20.0 ± 15.8 | 21.3 ± 17.6 | 23.0 ± 17.7 | 27.5 ± 18.3 | 0.008 |

| Maximum plaque burden, % | 77.7 ± 11.6 | 83.9 ± 11.5 | 83.1 ± 12.0 | 88.0 ± 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Minimum lumen area, mm2 | 2.92 ± 1.97 | 1.70 ± 1.50 | 2.06 ± 2.02 | 1.43 ± 1.41 | <0.001 |

| Anatomic plaque characteristics | |||||

| Total aggregate plaque volume in vessel, % | 45.9 ± 6.3 | 51.2 ± 7.1 | 48.6 ± 8.3 | 52.2 ± 8.0 | <0.001 |

| Plaque volume in lesion, % | 55.4 ± 8.0 | 61.5 ± 8.4 | 59.2 ± 8.4 | 62.0 ± 9.0 | <0.001 |

| Calcified volume in lesion, % | 10.6 ± 6.9 | 13.4 ± 10.1 | 10.9 ± 10.0 | 11.9 ± 7.9 | 0.170 |

| Lipid-rich necrotic core volume in lesion, % | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 1.5 | 0.027 |

| Intraplaque hemorrhage volume in lesion, % | 1.1 ± 2.3 | 1.4 ± 2.9 | 3.3 ± 4.9 | 1.7 ± 2.9 | 0.007 |

| Physiologic plaque characteristics | |||||

| FFRCT | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.10 | <0.001 |

| FFRCT gradient (dFFRCT/ds), per mm | 0.011 ± 0.005 | 0.017 ± 0.005 | 0.034 ± 0.008 | 0.055 ± 0.034 | <0.001 |

Values are as n (%) or mean ± SD.

FFRCT = fractional flow reserve by coronary computed tomography angiography.

Prognostic impact of FFRCT and FFRCT gradient

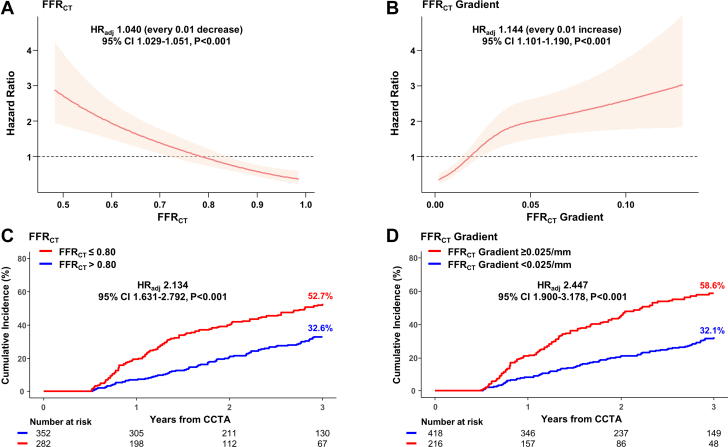

Both FFRCT (HRadj: 1.040 [every 0.01 decrease]; 95% CI: 1.029-1.051; P < 0.001) and FFRCT gradient (HRadj:1.144 [every 0.01 increase]; 95% CI: 1.101-1.190, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with the risk of future coronary events. When vessels were classified according to the optimal cutoff values of FFRCT or FFRCT gradient, the cumulative incidence of a future coronary event was significantly different according to FFRCT (52.7% vs 32.6%, respectively, for the FFRCT ≤0.80 vs FFRCT >0.80 groups; HRadj: 2.134, 95% CI: 1.631-2.792; P < 0.001) and FFRCT gradient (58.6% vs 32.1%, respectively, for FFRCT gradient ≥0.025/mm vs FFRCT gradient <0.025/mm groups; HRadj: 2.447; 95% CI: 1.900-3.178; P < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Physiologic Plaque Characteristics and Future Coronary Events

Associations of (A) FFRCT and (B) FFRCT gradient with future coronary events risk are presented in spline plots. Solid red lines represent HRs, and red shaded areas represent 95% CIs. Kaplan-Meier curves and cumulative incidence of future coronary events were compared according to (C) FFRCT and (D) FFRCT gradient. CCTA = coronary computed tomography angiography; FFRCT = coronary computed tomography angiography–derived fractional flow reserve; HRadj = adjusted HR.

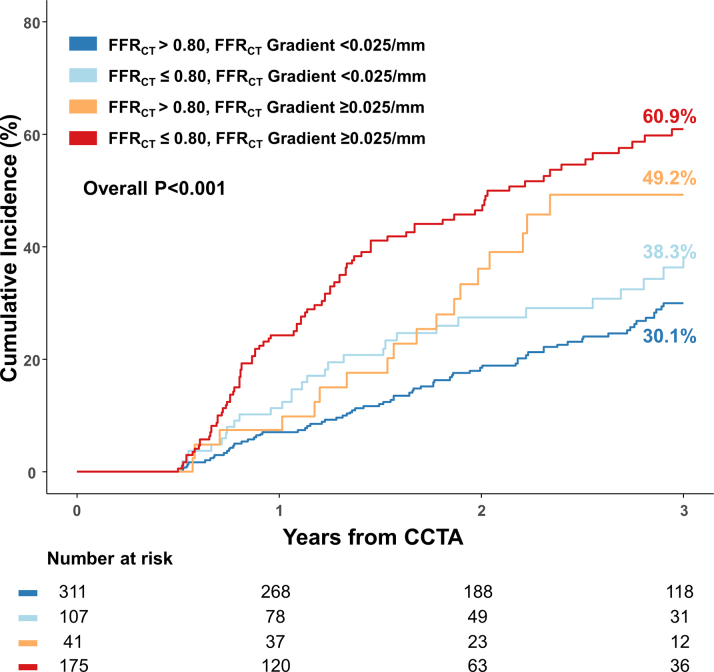

In addition, vessels with FFRCT gradient of ≥0.025/mm showed significantly higher risk of future coronary events than vessels with FFRCT gradient of <0.025/mm in both the FFRCT >0.80 (49.2% vs 30.1%; HRadj: 2.069; 95% CI: 1.265-3.385; P = 0.004) and FFRCT ≤0.80 subgroups (60.9% vs 38.3%; HRadj: 1.988; 95% CI: 1.317-2.999; P = 0.001) (Figure 4). The risk of future coronary events was significantly different according to pre-existing disease patterns classified by FFRCT and FFRCT gradient (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

FFRCT Gradient and Clinical Outcomes in Subgroups According to FFRCT

Kaplan-Meier curves and cumulative incidence of future coronary events are compared according to FFRCT gradient in vessels with (A) FFRCT of >0.80 and (B) FFRCT of ≤0.80. Abbreviations as in Figure 3.

Figure 5.

Clinical Outcomes According to Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography–Derived Fractional Flow Reserve and Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography–Derived Fractional Flow Reserve Gradient

Kaplan-Meier curves and cumulative incidence of future coronary events are compared between 4 groups classified by both FFRCT and FFRCT gradient. Abbreviations as in Figure 3.

Incremental predictability of integrating FFRCT gradient into FFRCT

Compared with FFRCT or FFRCT gradient alone, the model integrating both FFRCT and FFRCT gradient significantly increased the predictability of future coronary events (global chi-square for FFRCT, FFRCT gradient, and integrated model: 39.9, 35.8, and 45.8, respectively; P = 0.015 against FFRCT, and P = 0.002 against FFRCT gradient) (Supplemental Figure 4). In the multivariable model, pre-existing disease patterns were an independent predictor for future coronary events (HRadj: 1.314; 95% CI: 1.128-1.530; P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent Predictor of Future Coronary Events

| Univariable Analysis |

Multivariable Analysisa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Pre-existing disease patterns by FFRCT and FFRCT gradient | 1.433 (1.294-1.587) | <0.001 | 1.312 (1.126-1.528) | 0.001 |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 4.938 (2.252-10.82) | <0.001 | 2.379 (0.708-7.992) | 0.161 |

| Total aggregate plaque volume in vessel, % | 1.027 (1.008-1.046) | 0.004 | 1.002 (0.964-1.040) | 0.936 |

| Plaque volume in lesion, % | 1.030 (1.009-1.050) | 0.004 | 1.009 (0.976-1.042) | 0.595 |

| Low attenuation plaque | 1.655 (1.185-2.311) | 0.003 | 1.377 (0.929-2.041) | 0.111 |

| Positive remodeling | 1.218 (0.898-1.652) | 0.205 | ||

| Napkin-ring sign | 1.046 (0.697-1.571) | 0.827 | ||

| Spotty calcification | 1.205 (0.869-1.670) | 0.264 | ||

FFRCT = fractional flow reserve by coronary computed tomography angiography.

The multivariable model was constructed using coronary computed tomography angiography–derived variables with a P value of <0.05 from the univariable analyses along with age, sex, and diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

The current study evaluated the incremental prognostic value of FFRCT gradient in addition to FFRCT to predict future coronary events in medically treated patients. The main findings are as follows. First, FFRCT gradient and FFRCT were significantly associated with future coronary events. Second, FFRCT gradient of ≥0.025/mm was associated with an increased risk of future coronary events irrespective of FFRCT. Third, integrating both FFRCT and FFRCT gradient showed incremental predictability of future coronary events vs FFRCT or FFRCT gradient alone (Central Illustration).

Central Illustration.

FFRCT and FFRCT Gradient From Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography for Future Coronary Events

The current study evaluated the additive prognostic value of FFRCT gradient in addition to FFRCT to predict future coronary events using noninvasive coronary CTA and CFD in predicting risk of future coronary events. Both FFRCT and FFRCT gradient were significantly associated with the risk of future coronary events. Lesions with FFRCT gradient of ≥0.025/mm showed significantly higher risk of future coronary events than those with FFRCT gradient of <0.025/mm in both the FFRCT >0.80 and FFRCT ≤0.80 groups. Adding FFRCT gradient into the model with FFRCT alone showed significantly increased predictability of future coronary events. Integrating both FFRCT and FFRCT gradient showed incremental predictability of future coronary events compared with FFRCT alone. CCTA = coronary computed tomography angiography; CFD = computational fluid dynamics; FFRCT = coronary computed tomography angiography–derived fractional flow reserve; HRadj = adjusted HR.

Two different aspects of CAD

Atherosclerotic plaque formation is the key pathophysiology of CAD.1 Although atherosclerotic plaque accumulates throughout the entirety of the coronary arteries, the degree of accumulation varies across coronary arteries. Therefore, cumulative atherosclerotic burden in the target vessel and local severity of stenosis can be different according to the distribution of atherosclerotic plaque.23 Local severity of CAD, represented by stenosis diameter, plaque burden, or minimal lumen area, is a well-known prognostic factor of CAD.24,25 Likewise, cumulative burden of CAD, represented by %TAPV, FFR, calcium score, and the extent of nonobstructive CAD, is also known to be associated with the prognosis of CAD patients, even in the absence of severe local stenosis.26, 27, 28, 29 Because these 2 different aspects might benefit from different treatment, it is important to characterize and differentiate the disease pattern considering these 2 different aspects of CAD.

FFR is a surrogate marker of myocardial ischemia in a target vessel and a well-validated decision-making tool for revascularization.3,4 FFR is a per-vessel index that reflects cumulative pressure decrease occurring throughout the entire vessel.30 Therefore, despite similar FFR values, the severity of local stenosis can be different according to the distribution of atherosclerotic plaque in the target vessel.7 In this regard, the current study hypothesized that the integration of a quantifiable index reflecting local severity in addition to FFR would enable better prediction of future coronary events.

Pre-existing disease patterns by coronary CTA–derived FFRCT and FFRCT gradient

Currently, the most commonly used invasive method to evaluate the local severity of CAD is the pullback maneuver with a pressure wire and assessment of the pressure step-up amount across the stenosis.30 However, the conventional pullback maneuver has been interpreted by visual assessment without established objective criteria. In this regard, novel indexes such as pullback pressure gradient (PPG) index or FFR gradients have been introduced in recent studies.16,31 The PPG index was developed by using a motorized FFR pullback curve to quantify the distribution of CAD and discriminate between diffuse and focal lesions.31 However, because the PPG index indicates the proportion of a vessel where FFR drop occurs, the PPG index mostly represents the distribution of CAD, not the absolute degree of the local severity of stenosis. Conversely, Lee et al16 introduced the concept of instantaneous FFR gradient per unit time, which quantifies the local severity of CAD. That study included patients who underwent PCI based on a pre-PCI FFR of <0.80 and showed that patients without major FFR gradient showed higher rates of suboptimal PCI results than patients with major FFR gradient.

These recent studies demonstrate the objective quantification of the physiologic distribution and the local severity of CAD. However, inherent technical difficulties with pressure wire pullback, including the need for a motorized pullback device for the PPG index or constant manual pullback speed for FFR gradient, limit their clinical applicability in daily practice. Conversely, FFRCT technology and a virtual pullback curve can provide both FFRCT in the target vessel and FFRCT gradient across the target stenosis without additional procedures. Indeed, both FFRCT and FFRCT gradient showed significant correlation with coronary CTA parameters of anatomic severity (%TAPV, %PV, diameter stenosis, lesion length, maximum plaque burden, and minimum lumen area). More importantly, not only FFRCT, a per-vessel index indicating the cumulative burden over an entire vessel, but also FFRCT gradient, a per-lesion index indicating local severity, was associated with increased risk of future coronary events. Furthermore, FFRCT gradient was able to stratify vessels with higher risk of future coronary events in both the FFRCT >0.80 and FFRCT ≤0.80 groups. These results imply that FFRCT gradient in addition to FFRCT could provide additional prognostic implication to stratify vessels with higher risk of future coronary events.

Clinical implication of coronary CTA–derived FFRCT and FFRCT gradient

When pre-existing disease patterns were classified according to FFRCT and FFRCT gradient, the 4 groups showed distinct characteristics in coronary CTA parameters of anatomic severity (%TAPV, %PV, diameter stenosis, lesion length, maximum plaque burden, and minimum lumen area). In addition, integration of FFRCT gradient into the model with FFRCT significantly increased the predictability of future coronary events compared with either FFRCT or FFRCT gradient alone. These results further support the importance of considering FFRCT gradient in addition to the well-validated FFRCT in determining the treatment of CAD patients.

Although the clinical implications of local severity of CAD represented by the gradient of invasive FFR or quantitative flow ratio were previously evaluated, those studies mainly focused on predicting post-PCI physiologic results or clinical outcome.7,10,16 However, the current study evaluated the prognostic implication of FFRCT gradient from coronary CTA that was performed before the index invasive coronary angiography. Therefore, the current results represent the natural course of vessels according to disease patterns by FFRCT and FFRCT gradient in medically treated patients. Another point that needed to be highlighted is that physiologic indexes used in this study were derived from noninvasive coronary CTA. The clinical utility of coronary CTA has been continuously demonstrated in recent trials,32,33 and current guidelines recommend coronary CTA as the first diagnostic tool in evaluating symptomatic patients and FFRCT as a next diagnostic step in the presence of significant stenosis in coronary CTA.34 Because FFRCT gradient can be derived from virtual the pullback curve of FFRCT without an additional procedure, further study is warranted to validate the clinical implication of FFRCT gradient in addition to FFRCT in treatment decision making for symptomatic patients with CAD.

Study limitations

First, this study has limitations related to the observational design of the study. Consequently, confounding bias may occur because of measured and unmeasured variables. Second, only patients who underwent invasive coronary angiography 6 to 36 months after coronary CTA were included in the study, which may have caused selection bias. Therefore, the current results may not be generalized to an overall population who underwent coronary CTA. Further external validation is needed in future studies. Third, many vessels that were not suitable for coronary CTA or CFD analysis were excluded, which could cause selection bias. Fourth, the decision to perform coronary CTA and PCI was left to the physician’s discretion.

Conclusions

Patients with a high FFRCT gradient showed increased risk of future coronary events irrespective of FFRCT. In addition to the vessel-specific index, FFRCT, integration of the lesion-specific index, FFRCT gradient, showed incremental predictability of future coronary events.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: The integration of FFRCT gradient in addition to FFRCT further discriminated the risk of future coronary events and increased the predictability of future coronary events.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE: FFRCT gradient in addition to FFRCT could provide additional prognostic information to stratify vessels with higher risk of future coronary events.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Future study is warranted to evaluate the prognostic benefit of subsequent treatment decisions incorporating FFRCT gradient in patients with stable CAD.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The current study was supported by the internal research funds provided from the Heart Vascular Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center (OTX0004011). Other than providing financial support, the sponsors were not involved with design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr Hahn has received institutional research grants from the National Evidence-Based Healthcare Collaborating Agency, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea; Abbott Vascular; Biosensors; Boston Scientific; Daiichi-Sankyo; Donga-ST; Hanmi Pharmaceutical; and Medtronic Inc. Dr Gwon has received institutional research grants from Boston Scientific, Genoss, and Medtronic Inc. Dr J.-M. Lee has received institutional research grants from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Philips Volcano, Terumo Corporation, Zoll Medical, and Donga-ST. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Original data used in this analysis will be shared upon reasonable request. Any relevant inquiry should be emailed to Dr Joo Myung Lee (drone80@hanmail.net) or Dr Seung-Hun Lee (lsh8602@naver.com).

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental methods, figures, and references, please see the online version of this paper.

Contributor Information

Seung Hun Lee, Email: lsh8602@naver.com, gfmaniac@gmail.com.

Joo Myung Lee, Email: drone80@hanmail.net, joomyung.lee@samsung.com.

Appendix

References

- 1.Libby P., Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111:3481–3488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collet J.P., Thiele H., Barbato E., et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1289–1367. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knuuti J., Wijns W., Saraste A., et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407–477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawton J.S., Tamis-Holland J.E., Bangalore S., et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfrum M., De Maria G.L., Benenati S., et al. What are the causes of a suboptimal FFR after coronary stent deployment? Insights from a consecutive series using OCT imaging. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e1324–e1331. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J.M., Hwang D., Choi K.H., et al. Prognostic implications of relative increase and final fractional flow reserve in patients with stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2099–2109. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin D., Dai N., Lee S.H., et al. Physiological distribution and local severity of coronary artery disease and outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:1771–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J.M., Choi K.H., Koo B.K., et al. Prognostic implications of plaque characteristics and stenosis severity in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2413–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J.M., Choi G., Koo B.K., et al. Identification of high-risk plaques destined to cause acute coronary syndrome using coronary computed tomographic angiography and computational fluid dynamics. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S.H., Kim J., Lefieux A., et al. Clinical and prognostic impact from objective analysis of post-angioplasty fractional flow reserve pullback. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:1888–1900. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairbairn T.A., Nieman K., Akasaka T., et al. Real-world clinical utility and impact on clinical decision-making of coronary computed tomography angiography-derived fractional flow reserve: lessons from the ADVANCE Registry. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3701–3711. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas P.S., De Bruyne B., Pontone G., et al. 1-Year outcomes of FFRCT-guided care in patients with suspected coronary disease: the PLATFORM study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor A.J., Cerqueira M., Hodgson J.M., et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2010;4:407.e1–407.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng Y., Wang X., Tang Z., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CT-FFR with a new coarse-to-fine subpixel algorithm in detecting lesion-specific ischemia: a prospective multicenter study. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2024;77(2):129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2023.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S.H., Hong D., Dai N., et al. Anatomic and hemodynamic plaque characteristics for subsequent coronary events. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.871450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S.H., Shin D., Lee J.M., et al. Automated algorithm using pre-intervention fractional flow reserve pullback curve to predict post-intervention physiological results. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2670–2684. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Assen M., Varga-Szemes A., Schoepf U.J., et al. Automated plaque analysis for the prognostication of major adverse cardiac events. Eur J Radiol. 2019;116:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckler A.J., Karlöf E., Lengquist M., et al. Virtual transcriptomics: noninvasive phenotyping of atherosclerosis by decoding plaque biology from computed tomography angiography imaging. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:1738–1750. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.315969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motoyama S., Ito H., Sarai M., et al. Plaque characterization by coronary computed tomography angiography and the likelihood of acute coronary events in mid-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Garcia H.M., McFadden E.P., Farb A., et al. Standardized end point definitions for coronary intervention trials: the Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2192–2207. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., Jaffe A.S., et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2231–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Govindarajulu U.S., Malloy E.J., Ganguli B., Spiegelman D., Eisen E.A. The comparison of alternative smoothing methods for fitting non-linear exposure-response relationships with Cox models in a simulation study. Int J Biostat. 2009;5 doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1104. Article 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbab-Zadeh A., Fuster V. The risk continuum of atherosclerosis and its implications for defining CHD by coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2467–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chow B.J., Small G., Yam Y., et al. Incremental prognostic value of cardiac computed tomography in coronary artery disease using CONFIRM: Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:463–472. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.964155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone G.W., Maehara A., Lansky A.J., et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maddox T.M., Stanislawski M.A., Grunwald G.K., et al. Nonobstructive coronary artery disease and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312:1754–1763. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakazato R., Shalev A., Doh J.H., et al. Aggregate plaque volume by coronary computed tomography angiography is superior and incremental to luminal narrowing for diagnosis of ischemic lesions of intermediate stenosis severity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Detrano R., Guerci A.D., Carr J.J., et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J.M., Koo B.K., Shin E.S., et al. Clinical implications of three-vessel fractional flow reserve measurement in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:945–951. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toth G.G., Johnson N.P., Jeremias A., et al. Standardization of fractional flow reserve measurements. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:742–753. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collet C., Sonck J., Vandeloo B., et al. Measurement of hyperemic pullback pressure gradients to characterize patterns of coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1772–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SCOT-HEART Investigators. Newby D.E., Adamson P.D., Berry C., et al. Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:924–933. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Group D.T., Maurovich-Horvat P., Bosserdt M., et al. CT or invasive coronary angiography in stable chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1591–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2200963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gulati M., Levy P.D., Mukherjee D., et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:e187–e285. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.