Abstract

Background: In the past few decades, there has been a gradual increase in breast reconstruction post mastectomy; however, there exists a conflict about whether race has an influence on reconstruction rates. Methods: We conducted an electronic search from MEDLINE and Cochrane CENTRAL from their inception to September 2022. Primary outcome was disparity in rates of Immediate Breast Reconstruction (IBR) in racial minorities. Odds ratios were pooled using a random-effects model. All statistical analyses were performed on the Review Manager. Quality of included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist. Results: Twenty studies (n = 1 840 671) were identified. The pooled analysis of all the studies showed that subjects in racial minorities were significantly less likely to receive IBR as compared to White subjects (OR = 0.62, [95% confidence interval: 0.57-0.68; P < .01, I2 = 97%]. Subgroup analyses revealed that Asian subjects were the least likely to undergo IBR among different minorities (OR = 0.43). Conclusion: There exists a significant disparity in rates of IBR in different racial minorities as compared to White subjects. Future studies are warranted to assess factors contributing to such disparities in provision of healthcare.

Keywords: racial disparity, immediate breast reconstruction, breast cancer, mastectomy

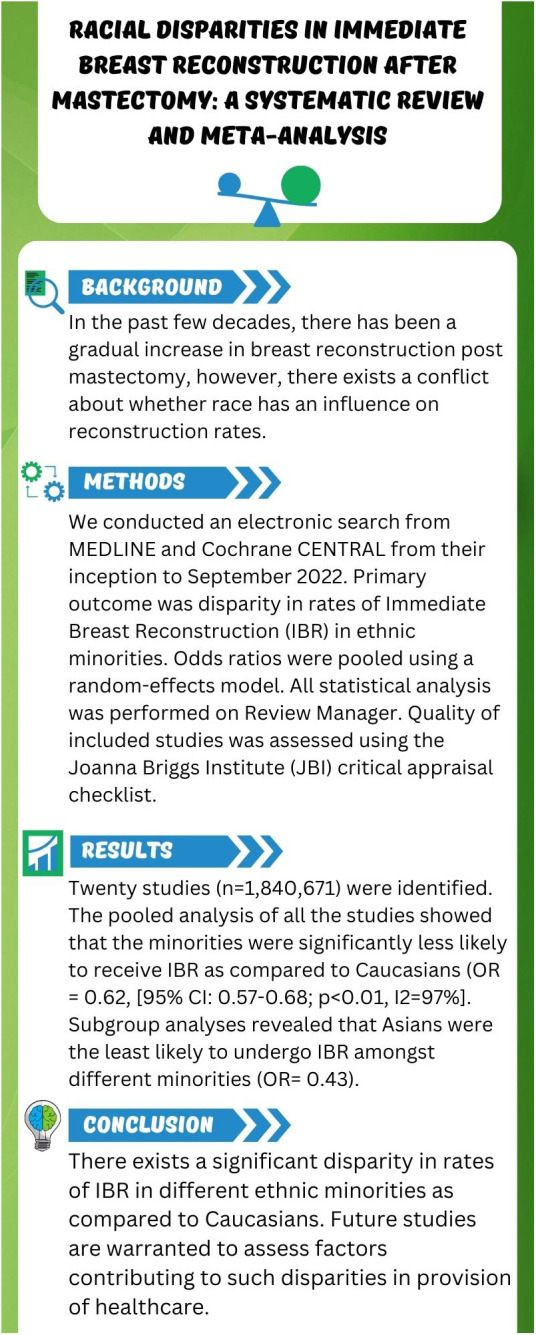

Graphical abstract.

This is a visual representation of the abstract.

Résumé

Historique : Depuis quelques décennies, on constate une augmentation graduelle des reconstructions mammaires après la mastectomie, mais on ne s’entend pas pour déterminer si la race a une influence sur le taux de reconstruction. Méthodologie : Les chercheurs ont réalisé une recherche électronique dans MEDLINE et Cochrane CENTRAL à compter de leur création jusqu’en septembre 2022. Le résultat primaire était la disparité des taux de reconstruction mammaire immédiate (RMI) au sein des minorités raciales. Les chercheurs ont établi les rapports de cote à l’aide d’un modèle à effets aléatoires. Ils ont effectué toutes les analyses statistiques sur Review Manager et évalué la qualité des études au moyen des listes d’évaluation critique de l’Institut Joanna Briggs (IJB). Résultats : Les chercheurs ont extrait 20 études (n = 1 840 671). L’analyse regroupée de toutes les études a révélé que les sujets de minorités raciales étaient beaucoup moins susceptibles de recevoir une RMI que les sujets blancs (RC = 0.62, [IC à 95% : 0.57 à 0.68; P < .01, I2 = 97%]). Parmi les diverses minorités, les analyses de sous-groupes ont révélé que les sujets asiatiques étaient les moins susceptibles de subir une RMI (RC = 0.43). Conclusion : Le taux de RMI est très différent parmi les diverses minorités raciales que chez les sujets blancs. De prochaines études devront être exécutées pour évaluer les facteurs qui contribuent à ces disparités dans la prestation des soins.

Mots-clés: cancer du sein, disparités raciales, mastectomie, reconstruction mammaire immédiate

Introduction

Racial disparity refers to imbalances and incongruities, including income, societal treatment, economic status, and healthcare opportunities, between different racial groups. 1 These differences, specifically the limitations in access to healthcare, lead to poorer outcomes across multiple healthcare domains, especially in response to surgical interventions in many racial minorities. This phenomenon has been widely explored in various surgical interventions.2–5

In the past few decades, there has been a gradual increase in both immediate and delayed breast reconstruction post mastectomy. 6 The National Institute of Health Care Excellence guidelines state that women undergoing mastectomy should be presented with an option of breast reconstruction during the initial consultation. 7 According to the Women's Health Care and Cancer Rights Act in 1998, health plans that offer breast cancer coverage are also required to provide coverage for breast reconstruction and prostheses. 8 In order to increase awareness and availability of reconstructive procedures among racial minorities, Breast Cancer Patient Education Action Coalition was introduced in 2015. Immediate reconstruction offers better cosmetic results, decreased psychological distress and reoperation rates.9–11 Despite the consensus of the beneficial effects of immediate breast reconstruction (IBR), literature has shown that the rates of reconstructive breast surgery are much lower in certain racial groups such as African-Americans and Hispanics.12,13

There exists a conflict about whether race has an influence on reconstruction rates, with certain studies reporting a disparity with rates being much higher in Caucasian women as compared to minority races,12,13 while others reporting a lack of significant impact of race on reconstruction rates.14,15 The factors implicated include social, cultural, and religious beliefs associated with certain races, socioeconomic status, education level, types of insurance plans, 16 regional density of races, and availability of better healthcare facilities. 17 Other factors that need to be considered are health literacy over breast reconstruction options, geographic access to a plastic surgeon, and lastly but most importantly, the physician's failing to offer IBR as an option and inconsistency in their referral pattern. 18

The aim of our study was to reach a consensus about the association between race and IBR in patients undergoing mastectomy with the hope that, in the future, the results might help surgeons ensure equal availability of reconstructive procedures among all racial groups.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We used the guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 19 Our search strategy included all the relevant search terms that had any relationship to either the target population or the outcome being studied.

We conducted an electronic search from MEDLINE, Cochrane CENTRAL, from their inception to September 2022 with no language restrictions. The search string for all the databases was (mastectomy OR breast surgery) AND (race OR racial disparity OR blacks OR African American OR people of African descent OR Asians OR Hispanics OR whites OR Caucasians OR Indians OR browns) AND (immediate breast reconstruction OR IBR). The reference lists of the articles were also manually checked for any relevant studies that could have been missed during the initial search. In addition, we also searched through the World Health Organization's website for any relevant data. The detailed search string including all the syntax elements is given in Supplemental Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

Only those studies were eligible that included: (a) adult females (≥18 years old) who underwent IBR postmastectomy; (b) adjusted odds ratio (AOR) as effect size while comparing race with rate of IBR; and (c) white population as a reference.

Studies having any of the following were excluded: (a) target population ≤18 years old (b) comparison of nonwhite population as a reference with other races; (c) reporting of effect sizes other than AORs for correlation between race and IBR; (d) case reports, review articles, and meta-analyses.

Selection Process

All the retrieved results were uploaded to Google Sheets alongside the links to the articles. Duplicates among the databases were identified and removed promptly. Two independent reviewers (Z and MS) screened the remaining articles (kappa = 0.92) and only the studies that strictly met the eligibility criteria were included in the analysis. Initially, the titles and abstracts of the studies were checked for relevance, however, in case of reasonable doubt regarding relevance, full-text articles were studied. Any disagreement between the reviewers was resolved by a discussion with the third investigator (SUQ). The primary outcome was disparity in rates of IBR in different racial minorities as compared to the White population.

Quality Assessment

To assess the reliability of the included studies, all the shortlisted studies were assessed by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed on Review Manager (Version 5.4.1, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). A detailed analysis was conducted using the AOR with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the results were pooled using a random effects model. Higgins I2 was used to assess the statistical heterogeneity between trials, an I2 statistic of more than 50% was considered to have significant heterogeneity, and a value less than 50% for I2 was considered acceptable. In all cases, a P-value of .05 or less was regarded as significant. Detailed subgroup and sensitivity analyses were conducted to eliminate the heterogeneity obtained using Higgins I2, and forest plots were drafted to visualize the results. Publication bias was identified using a funnel plot.

Results

Literature Search Results

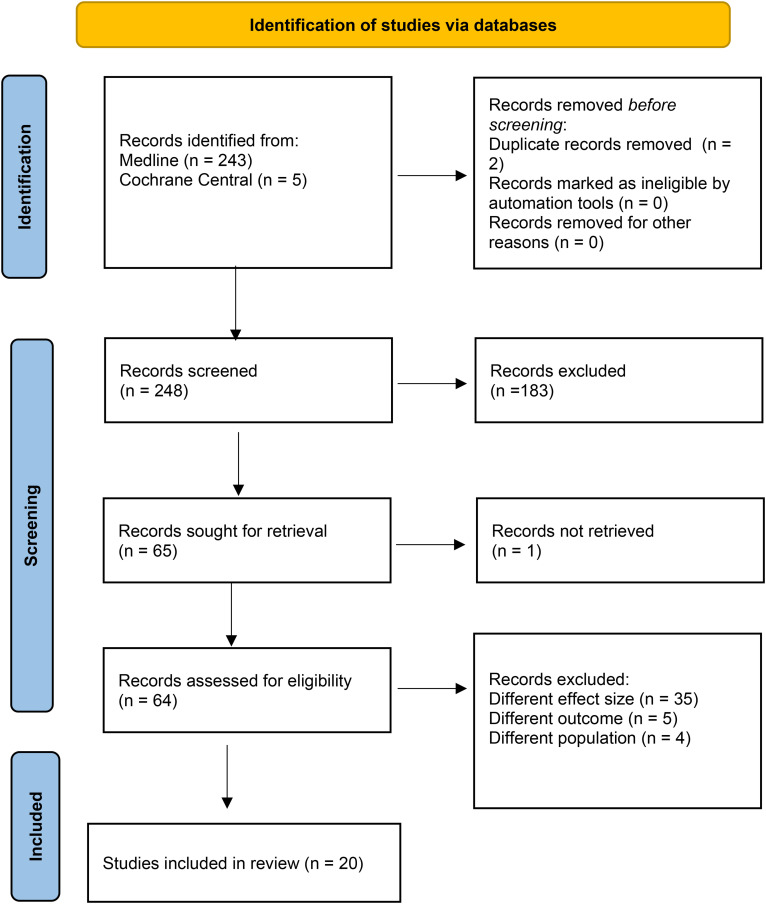

A total of 252 results were retrieved after the initial search. After removing the duplicates and screening the studies based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 20 studies were evaluated.18,20–38 The results are summarized in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram elaborating the literature review process.

Study Attributes and Baseline Characteristics

All the included studies were retrospective and had data extracted from the local and national databases. All of them included White patients whereas only 18 included Black patients,18,20–28,30–34,35(p321),37,38 12 included Hispanic patients,20–22,24–27,31–33,35 and 9 included Asian patients.18,20,21,24,26,27,31,34,35 The studies evaluated a total of 1 840 671 participants undergoing mastectomy out of which 485 943 (26.40%) underwent IBR. Baseline characteristics of all the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Serial number | Author(s) | Year of publication | Time period (of database search) | Study design | Setting/Database | Total no. of Mastectomy patients/Population size (n) | No. of patients who underwent IBR (n) | Races reported in the study | Type of IBR (Implant vs Autologous) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meade et al | 2022 | Oct 2016-Oct 2019 | Retrospective | Chart review (safety-net hospital) | 645 | 180 | White, Non-White (Hispanic, African American, Asian) | Combination |

| 2 | Mandelbaum et al | 2021 | 2005-2014 | Retrospective | NIS database | 729 340 | 301 055 | White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Other (combined group of Native American and other races as reported by NIS) | Combination |

| 3 | Siotos et al | 2020 | 2003-2015 | Retrospective | Johns Hopkins SKCCC Tumor Registry | 1459 | 984 | Caucasian, African American, Asian, Hispanic, Other | Combination |

| 4 | Sergesketter et al | 2019 | 1998-2014 | Retrospective | USA (SEER database) | 346 418 | 75 506 | White, Black, Hispanic, Other | Combination |

| 5 | Momoh et al | 2019 | July 2013-Sept 2014 | Retrospective | USA (SEER database) | 936 | 484 | White, Black, Latina, Asian | NA |

| 6 | Wirth et al | 2018 | 2000-2013 | Retrospective | USA (SEER Database) | 51 862 | 10 113 | Black, White | Combination |

| 7 | Richards et al | 2018 | 2004-2008 | Retrospective | US/ Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), National Cancer institute (NCI), | 5760 | 2385 | Black, White, Hispanic, Asian, Other | NA |

| 8 | Schumacher et al | 2017 | 2004-2013 | Retrospective | USA (The National Cancer Database (NCDB)) | 297 121 | 145 577 | White, Black, Other | Combination |

| 9 | Offodile et al | 2015 | 2005-2011 | Retrospective | ACS-NSQIP database (USA) | 44 597 | 16 642 | White, Black, Asian, Hispanic | NA |

| 10 | Mahmoudi et al | 2015 | 1998-2006 | Retrospective | US/New York State inpatient database | 44 621 | NA | White, African American, Hispanic | Implant |

| 11 | Butler et al | 2015 | 2005-2011 | Retrospective | US/ ACS-NSQIP | 48 564 | 16 150 | Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, Other | Autologous |

| 12 | Fischer et al | 2014 | 2005-2011 | Retrospective | ACS-NSQIP datasets | 42 823 | 12 383 | White, Black, Hispanic, Other | Combination |

| 13 | Kruper et al | 2013 | 2003-2007 | Retrospective | OSHPD database | 4395 | 402 | White, Hispanic, African American, Asian, Other (6 American Indians/Alaskan natives, 14 native Hawaiians/ other Pacific Islanders, 303 with races other than as stated above, and 160 white with unknown ethnicity) | Implant |

| 14 | Hershman et al | 2012 | Jan 2000-March 2010 | Retrospective | US (Perspective database) | 123 702 | 37 360 | White, Black, Other | Combination |

| 15 | Kruper, Holt et al | 2011 | 2003-2007 | Retrospective | US/ California office of statewide health planning and development hospital discharge database (OSHPD) | 15 794 | 4152 | White, African American, Asian, Other, Unknown | Combination |

| 16 | Kruper, Xu, et al | 2011 | 2003-2007 | Retrospective | US (OSHPD) | 18 222 | 5270 | White, Hispanic, African American, Asian, Other (one Native American patient, 74 patients with races other than white, African American, or Asian, and 80 white patients with unknown ethnicity), Unknown | NA |

| 17 | Jeevan et al | 2010 | April 2006-Feb 2009 | Retrospective | UK (HES database) | 44 837 | 7375 | White, non-White | Combination |

| 18 | Rosson et al | 2008 | Jan 1, 1995-Dec 31, 2004 | Retrospective | US (Maryland Hospital Discharge Database) | 17 925 | 4994 | White, African American | NA |

| 19 | Morrow et al | 2005 | Dec 2001-Jan 2003 | Retrospective | USA (SEER database) | 646 | 245 | White, African American, Other | NA |

| 20 | Tseng et al | 2004 | Jan,1 2001-Dec 31, 2002 | Retrospective | USA (The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) | 1004 | 376 | White, African American, Hispanic, Asian, Middle Eastern | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; IBR, immediate breast reconstruction.

Results of the Meta-Analysis

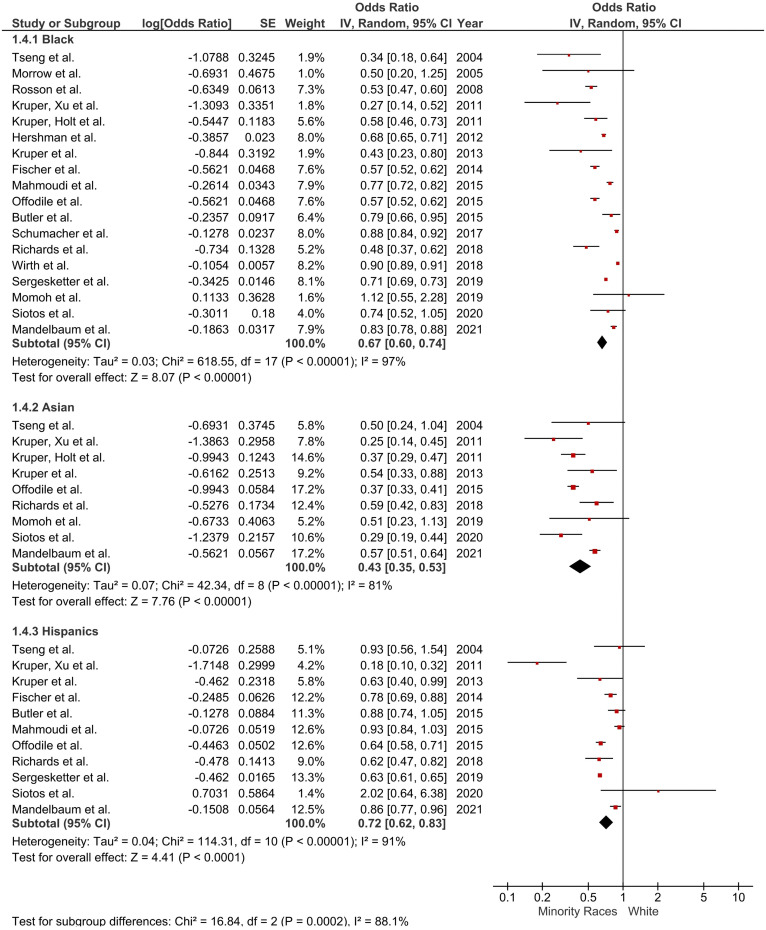

All the studies reported rates of IBR following mastectomy in individual racial minorities, using White patients as the reference population. The pooled analysis of all the studies showed that patients in racial groups other than White (Asian, Hispanic, and Black populations) were significantly less likely to receive IBR as compared to White patients (OR = 0.62, [95% CI: 0.57-0.68; P < .01, I2 = 97%]. Subgroup analysis based on the individual racial minorities revealed the following trends: Black patients were 33% less likely to undergo IBR compared to White patients (OR = 0.67 [95% CI: 0.61-0.74]; P < .01, I2 = 97%), while Asian patients underwent IBR at a rate that was 57% lower (OR = 0.43 (95% CI: 0.35-0.53); P < .01, I2 = 81%). Finally, Hispanic patients were 27% less likely to receive IBR compared to their White counterparts (OR = 0.73 (95% CI: 0.64-0.84); P < .01, I2 = 91%). Figure 2 summarizes these results.

Figure 2.

Subgroup analysis based on ethnicity.

Quality Assessment

The detailed assessment of quality of the included studies is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality Assessment Using JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist.

| Study | Study population | Exposure | Ascertainment of exposure | Confounders identification | Adjustment for confounders | Presence of outcome of interest | Assessment of outcome | Follow-up time | Follow-up loss | Strategies for loss to follow-up | Statistical analysis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fischer et al22 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Jeevan et al29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Kruper et al21 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Mahmoudi et al32 | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | 6 |

| Mandelbaum et al20 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Meade et al36 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Butler et al33 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Hershman et al38 | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 7 |

| Kruper et al35 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Momoh et al18 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | 6 |

| Morrow et al30 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | 5 |

| Offodile et al24 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 7 |

| Richards et al31 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Schumacher et al28 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Sergesketter et al25 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 7 |

| Siotos et al26 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 7 |

| Tseng et al27 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 7 |

| Wirth et al23 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Rosson et al37 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

| Kruper et al34 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | 8 |

Abbreviations: Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear; NA, not applicable; JBI, Joanna Briggs Institute.

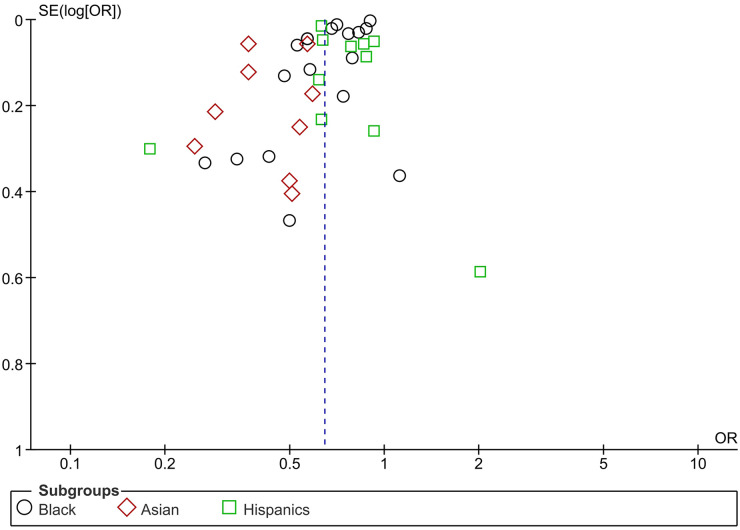

Publication Bias

Funnel Plot analysis, shown in Figure 3, of the three racial minorities suggests a significant publications bias especially for Asian patients where studies clutter around 0.5. This means that most studies published were focusing on Asian patients having lower odds of receiving IBR than White subjects. Studies which were not published were not included. While the funnel plot of Black and Hispanic patients is not uniform enough to rule out publication bias, most studies gather near the value of 1, suggesting a smaller difference in the odds of receiving IBR when compared with the White population. This could also explain the high heterogeneity in the results, especially for Asian minorities. Well-published studies covering all aspects of a particular outcome may help to configure more causes of disparity and may also reduce heterogeneity for future meta-analyses.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot analysis for the ethnic minorities.

Discussion

This meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between race and the receipt of IBR in postmastectomy patients. The results showed a decreased likelihood of receiving IBR in all racial minorities compared to the White population. The discrepancy was most pronounced in Asian patients, with a 57% lower likelihood of receiving IBR. This was followed by Black patients, which had a 33% lower likelihood, and finally, Hispanic patients with a 27% lower likelihood of receiving IBR.

In general, the available evidence was assessed as having moderate quality. Out of the 20 studies included in the final analysis, 17 provided combined AORs. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses had only minimal impact on the odds ratios, with the overall results consistently demonstrating a significant positive association.

In comparison with the two largest studies that have been conducted previously, Mandelbaum et al 20 and Sergesketter et al, 25 our study corroborates the existing notion that racial disparity exists between various races despite the increasing trend of postmastectomy IBR in recent years. Our meta-analysis reinforces the trend observed in the receipt of IBR in association with race. Due to the larger pool included in the analysis, it can be highlighted with greater certainty that racial minorities are lagging behind the White population in receiving IBR after undergoing mastectomy.

Wirth et al 23 explained how geographical regions have an impact on the receipt of IBR among the different races themselves, later comparing them to the White population. Black subjects belonging to the Southwest region were more likely to receive postmastectomy breast reconstruction than those living in the Pacific Coast. Other regions showing disparity included the East and Southwest regions. Mandelbaum et al 20 explained that factors such as an age less than 40, private insurance coverage along with top income quartile range, a high load of patients, an urban-teaching hospital setting, and bilateral mastectomy, were associated with an increased odds of IBR.

Segesketter et al 25 pointed out that the type of IBR also influences the rates of IBR. Compared to the White population, which prefers implant-based reconstruction, tissue-based IBR is preferred in the Black and Hispanic populations. Similar results were explained by Offodile et al 24 which revealed that the Asian subgroup preferred a free-transfer autologous reconstruction over an implant-based reconstruction.

An increasing trend of IBR due to expansion of the state Medicaid rules shown by Mahmoudi et al 32 entails how factors influencing race or minorities have influenced the receipt of IBR, further explaining the disparity.

A comprehensive investigation is warranted to examine the entirety of the patient journey, spanning from the diagnosis of breast cancer in individuals of a specific race to their interaction with healthcare facilities and providers, culminating in mastectomy and receipt of IBR. This exploration should encompass a wide range of factors, including personal preferences as well as socioeconomic and geographical considerations. The results of our meta-analysis highlight that further thought be put into establishing schemes to tackle it.

An enhanced doctor–patient communication system is essential for effectively addressing language barriers. It is crucial for doctors to place particular emphasis on patients of diverse racial backgrounds who intentionally choose not to pursue IBR, which entails ensuring these patients are well-informed about the potential benefits of IBR and addressing any misconceptions they may have. Encouraging community-driven programs to raise awareness about IBR and conducting surveys to gather individual insights into the challenges faced by individuals from different racial backgrounds when considering IBR are important steps to take. Our efforts should be specifically directed toward racial groups exhibiting significantly lower rates of IBR compared to the White population. Moreover, government-led strategies should be devised and implemented to ensure IBR is covered by all insurance programs. The utilization of IBR has a significant role in restoring self-esteem for patients who experience a negative impact on their body image during breast cancer treatment. As healthcare providers, it is our responsibility to support patients throughout the entirety of their care journey, addressing all aspects of their well-being.39,40

A qualitative study would be an excellent addition to the literature regarding the topic as that will help to better rule out the exact causes of disparities and the subjectivity associated with it. A good addition to the literature could be looking at the trends in racial disparity and geographical differences.

Moreover, a few implications toward future research would be to assess economic and healthcare accessibility. If there is any social stigma associated with IBR that should be checked out as well. Patient and physician awareness is necessary regarding the benefits of IBR and should be offered to all the patients after mastectomy. A possible cause of disparity could be a difference in complications among different racial groups and more studies should be structured considering the aforementioned. This will not only help improve the outcomes for individual patients but also help in better policy making.

Limitations

Our study provides a comprehensive review of existing literature to assess the influence of race on the rate of receiving IBR following mastectomy. However, it is important to interpret the results in light of certain limitations. Firstly, we excluded studies that did not utilize individuals of White race as the reference race and those that did not report AORs. Moreover, our analysis revealed significant heterogeneity, likely stemming from the inclusion of minority populations from various geographic regions, which could have greatly impacted the findings. Additionally, the varying time spans considered for sample sizes should be taken into account as an important factor. Furthermore, like all meta-analyses, our study is susceptible to selection bias, and this should be considered when evaluating and implementing the results.

Conclusion

Our analysis concludes that there is a significant association between race and utilization of IBR. Minority races especially Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations are less likely to undergo reconstruction postmastectomy compared to White population. Since disparity still exists, this sets the stage for further research to identify the exact causes and strategies for mitigation.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-psg-10.1177_22925503241255142 for Racial Disparities in Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Shurjeel Uddin Qazi, MBBS, Sarah Aman, MBBS, Muhammad Hassaan Wajid, MBBS, Zainab Qayyum, MBBS, Muhammad Bilal Shahid, MBBS, Alina Tanvir, MBBS, Sania Javed, MBBS, Mahnoor Saeed, MBBS, Eesha Razia, MBBS, Alina Nayyar, MBBS, Osama Abdur Rehman, MD, and Faisal Khosa, MD in Plastic Surgery

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to the Research Council of Pakistan for their invaluable support throughout the entire process of conducting this meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: SUQ: Inception of the idea, overall supervision of the project and relevant guidance where needed. SA: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction, Data Analysis, Quality Appraisal and Referencing. MHW: This author was involved in Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction, Data Analysis, Manuscript Writing. ZQ: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction, Data Analysis and Manuscript Writing. MBS: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Analysis, Manuscript Writing and Referencing. AT: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction and Referencing. SJ: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction, Data Analysis and Manuscript Writing. MS: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction, Data Analysis and Manuscript Writing. ER: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction, Data Analysis and Manuscript Writing. AN: Article Search, Article Selection, Data Extraction and Data Analysis. OAR: Article Search, Article Selection and Data Extraction. FK: Mentorship and supervision during the project.

Authors’ Note: Faisal Khosa is the recipient of the Michael Smith Health Research BC Health Professional-Investigator award (2023-2028); Don Rix Physician Leadership Lifetime Achievement Award (2022); BC Achievement Foundation – Mitchell Award of Distinction (2022); University of British Columbia – Distinguished Achievement Award for Equity, Diversity & Inclusion (2022) and Vancouver Medical Dental & Allied Staff Association – Equity, Diversity & Inclusion Award (2022).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Muhammad Hassaan Wajid https://orcid.org/0009-0004-4952-6801

Sania Javed https://orcid.org/0009-0001-2154-5216

Osama Abdur Rehman https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1300-3114

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Henry C. HUSL Library: Social Justice: Racial Disparity. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://library.law.howard.edu/socialjustice/disparity

- 2.Patel J, Pallapothu S, Langston A, et al. A systematic review of the recruitment and outcome reporting by sex and race/ethnicity in stent device development trials for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. Published online October 19, 2022:S0890-5096(22)00634-3. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2022.09.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021;27(6):900‐912. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht LM, Pester B, Braciszewski JM, et al. Socioeconomic and racial disparities in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2020;30(6):2445‐2449. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04394-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina G, Clancy TE, Tsai TC, Lam M, Wang J. Racial disparity in pancreatoduodenectomy for borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(2):1088‐1096. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08717-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albornoz CR, Bach PB, Mehrara BJ, et al. A paradigm shift in U.S. breast reconstruction: increasing implant rates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(1):15‐23. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729cde [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018. Accessed January 20, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519155/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act (WHCRA) | CMS. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/whcra_factsheet.

- 9.Holley DT, Toursarkissian B, Vásconez HC, et al. The ramifications of immediate reconstruction in the management of breast cancer. Am Surg. 1995;61(1):60‐65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkins EG, Cederna PS, Lowery JC, et al. Prospective analysis of psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: one-year postoperative results from the Michigan breast reconstruction outcome study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(5):1014‐1025; discussion 1026-1027. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200010000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan SR, Fletcher DRD, Isom CD, Isik FF. True incidence of all complications following immediate and delayed breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(1):19‐28. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181774267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malekpour M, Devitt S, DeSantis J, Kauffman C. Racial disparity in immediate breast reconstruction; a gap that is not closing. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2022;30(4):317‐323. doi: 10.1177/22925503211055525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alderman AK, McMahon L, Wilkins EG. The national utilization of immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction and the effect of sociodemographic factors. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):695‐703; discussion 704-705. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041438.50018.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desch CE, Penberthy LT, Hillner BE, et al. A sociodemographic and economic comparison of breast reconstruction, mastectomy, and conservative surgery. Surgery. 1999;125(4):441‐447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llaneras J, Klapp JM, Boyd JB, et al. Post-mastectomy patients in an urban safety-net hospital: how do safety-net hospital breast reconstruction rates compare to national breast reconstruction rates? Am Surg. Published online December 28, 2021:31348211054071. doi: 10.1177/00031348211054071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shippee TP, Kozhimannil KB, Rowan K, Virnig BA. Health insurance coverage and racial disparities in breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(3):e261‐e269. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habermann EB, Thomsen KM, Hieken TJ, Boughey JC. Impact of availability of immediate breast reconstruction on bilateral mastectomy rates for breast cancer across the United States: data from the nationwide inpatient sample. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(10):3290‐3296. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3924-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Momoh AO, Griffith KA, Hawley ST, et al. Patterns and correlates of knowledge, communication, and receipt of breast reconstruction in a modern population-based cohort of patients with breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(2):303‐313. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777‐784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandelbaum A, Nakhla M, Seo YJ, et al. National trends and predictors of mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2021;222(4):773‐779. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kruper L, Xu XX, Henderson K, Bernstein L, Chen SL. Utilization of mastectomy and reconstruction in the outpatient setting. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(3):828‐835. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2661-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer JP, Wes AM, Tuggle CT, et al. Mastectomy with or without immediate implant reconstruction has similar 30-day perioperative outcomes. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(11):1515‐1522. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wirth LS, Hinyard L, Keller J, Bucholz E, Schwartz T. Geographic variations in racial disparities in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a SEER database analysis. Breast J. 2019;25(1):112‐116. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Offodile AC, Tsai TC, Wenger JB, Guo L. Racial disparities in the type of postmastectomy reconstruction chosen. J Surg Res. 2015;195(1):368‐376. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sergesketter AR, Thomas SM, Lane WO, et al. Decline in racial disparities in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis from 1998 to 2014. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(6):1560‐1570. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siotos C, Lagiou P, Cheah MA, et al. Determinants of receiving immediate breast reconstruction: an analysis of patient characteristics at a tertiary care center in the US. Surg Oncol. 2020;34:1‐6. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2020.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tseng JF, Kronowitz SJ, Sun CC, et al. The effect of ethnicity on immediate reconstruction rates after mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer. 2004;101(7):1514‐1523. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schumacher JR, Taylor LJ, Tucholka JL, et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with post-mastectomy immediate reconstruction in a contemporary cohort of breast cancer survivors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(10):3017‐3023. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5933-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeevan R, Cromwell DA, Browne JP, et al. Regional variation in use of immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer in England. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36(8):750‐755. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrow M, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, et al. Correlates of breast reconstruction: results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2005;104(11):2340‐2346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards CA, Rundle AG, Wright JD, Hershman DL. Association between hospital financial distress and immediate breast reconstruction surgery after mastectomy among women with ductal carcinoma in situ. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(4):344‐351. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahmoudi E, Giladi AM, Wu L, Chung KC. Effect of federal and state policy changes on racial/ethnic variation in immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(5):1285‐1294. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butler PD, Nelson JA, Fischer JP, et al. Racial and age disparities persist in immediate breast reconstruction: an updated analysis of 48,564 patients from the 2005 to 2011 American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program Data Sets. Am J Surg. 2016;212(1):96‐101. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruper L, Holt A, Xu XX, et al. Disparities in reconstruction rates after mastectomy: patterns of care and factors associated with the use of breast reconstruction in southern California. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(8):2158‐2165. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1580-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kruper L, Xu X, Henderson K, Bernstein L. Disparities in reconstruction rates after mastectomy for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): patterns of care and factors associated with the use of breast reconstruction for DCIS compared with invasive cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(11):3210‐3219. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2010-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meade AE, Cummins SM, Farewell JT, et al. Breaking barriers to breast reconstruction among socioeconomically disadvantaged patients at a large safety-net hospital. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(7):e4410. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosson GD, Singh NK, Ahuja N, Jacobs LK, Chang DC. Multilevel analysis of the impact of community vs patient factors on access to immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy in Maryland. Arch Surg. 2008;143(11):1076‐1081; discusion 1081. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershman DL, Richards CA, Kalinsky K, et al. Influence of health insurance, hospital factors and physician volume on receipt of immediate post-mastectomy reconstruction in women with invasive and non-invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(2):535‐545. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2273-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Victoria M, Marie B, Dominique R, et al. Breast reconstruction and quality of life five years after cancer diagnosis: VICAN French national cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;194(2):449‐461. doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06626-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kowalczyk R, Nowosielski K, Cedrych I, et al. Factors affecting sexual function and body image of early-stage breast cancer survivors in Poland: a short-term observation. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19(1):e30‐e39. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-psg-10.1177_22925503241255142 for Racial Disparities in Immediate Breast Reconstruction after Mastectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by Shurjeel Uddin Qazi, MBBS, Sarah Aman, MBBS, Muhammad Hassaan Wajid, MBBS, Zainab Qayyum, MBBS, Muhammad Bilal Shahid, MBBS, Alina Tanvir, MBBS, Sania Javed, MBBS, Mahnoor Saeed, MBBS, Eesha Razia, MBBS, Alina Nayyar, MBBS, Osama Abdur Rehman, MD, and Faisal Khosa, MD in Plastic Surgery