Abstract

The Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) consists of 10 questions that assess three aspects of financial planning for retirement: reflection about retirement plans, engagement with information on retirement preparedness, and evaluation of retirement preparedness. The RKS was administered to 1350 adults 50 and older in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) as an experimental module for the 2020 wave along with the “Big Three” questions of financial literacy that assess knowledge about inflation, interest rate, and risk. Results of the study provide support for the reliability of the RKS scales in the full sample and separately for non-retired and retired adults. We also find support for the construct validity of the RKS based on its associations with the Financial Literacy Score (i.e. Big Three questions), retirement status, sociodemographic characteristics, financial outcomes and planning horizons, personality traits, and satisfaction with life and other related outcomes. We find that better RKS scores are correlated with higher objective financial knowledge and levels of education, being retired, better financial outcomes (value of financial assets, probability of leaving a 10,000 bequest, and IRA/Keogh, stock, checking and CD account balances), longer financial planning horizon, being extrovert, open and conscientious, and higher levels of satisfaction with life, income, personal financial situation, and health. We also conduct a multiple regression analysis that provides support for the validity of the RKS. The RKS is useful as it provides new information about knowledge gaps in financial planning for retirement.

Keywords: retirement preparedness, retirement planning, financial literacy, financial knowledge, measurement

1. Introduction

Retirement knowledge is positively related to wealth accumulation, retirement preparedness, and financial wellbeing in retirement among older adults (Bucher-Koenen & Lusardi, 2011; Gustman & Steinmeier, 2001, Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011; Carter & Skimmyhorn, 2018). But 44% of adults in the United States (U.S.) stated they are not saving for retirement (Center for Financial Preparedness, 2022) and 28% of non-retired U.S. adults reported no retirement savings (Federal Reserve, 2023).

Understanding what individuals know about financial planning is important for promoting preparedness and wealth accumulation for retirement. A systematic review indicated that there are significant racial, ethnic, and gender differences in financial knowledge in the United States (Blanco et al., 2022). Women, minorities, and individuals with lower levels of education are more likely to show lower levels related to financial literacy and retirement knowledge, planning, and savings (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011; Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015). Among non-retired adults, 40–44% of Blacks and Hispanics compared to 20% of Whites do not have any retirement savings (Federal Reserve, 2023). In addition, Whites are more likely to feel that their retirement savings are on track (37%) than Blacks (22%) and Hispanics (20%) (Federal Reserve, 2023). Moreover, women are less comfortable managing investments in their retirement accounts than men, and this difference holds regardless of educational attainment (Federal Reserve, 2023).

The complexity of information about retirement saving plans contributes to low rates of retirement planning (Lusardi, 2005). Lack of financial knowledge about retirement leads to mistakes in retirement decision-making (Clark et al., 2012, Jacobs-Lawson et al. 2005; Mitchell, 2017; Yeh, 2022). Overconfidence about financial knowledge, as measured by the difference between subjective and objective financial knowledge, can also negatively affect retirement preparedness (Angrisani & Casanova, 2021). People who have access to financial education in the workplace seem to be more likely to have a retirement saving plan (i.e., a retirement saving account), and having a retirement saving plan is associated with higher levels of retirement confidence (Joo & Grable, 2005). Being financially literate has been associated with lower present bias and more accurate perception of exponential growth, where these two factors have a positive impact on retirement savings (Anantanasuwong, 2023).

A reliable and valid measure of retirement knowledge is needed to devise effective programs and policies to improve retirement knowledge, planning, and preparedness. A recent review of the literature found differences among racial and ethnic groups in engaging and acquiring retirement knowledge (Viceisza et al., 2023). Assessing retirement knowledge is necessary to help devise policies and interventions to address these disparities. The Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) assesses knowledge and financial planning for retirement. The RKS was designed to be applicable to lower educational-level English and Spanish language and to be comparable for retired and non-retired adults.

The RKS was included in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) as an experimental module for the 2020 wave along with the “Big Three” questions of financial literacy that assess knowledge about inflation, interest rate, and risk (Lusardi, 2019; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011). We use this data to assess the reliability and validity of the RKS separately for non-retired and retired adults. We assess the internal consistency reliability of the scale and evaluate associations of the RKS with objective financial knowledge (i.e., Big Three questions), retirement status, sociodemographic characteristics, financial outcomes and planning horizons, personality traits, and satisfaction with life and other related outcomes.

Our paper is organized as follows. In Sections 2 and 3 we present our review of previous measures related to financial planning for retirement and the RKS, respectively. In Section 3 we present our data and methodology. In Section 4 we provide our results, and in Section 5 our conclusion.

2. Previous Measures Related to Financial Planning for Retirement

We reviewed the literature to identify existing measures related to financial planning for retirement used in the United States. We identified a 20-item financial knowledge scale (Knoll & Houts, 2012) and a 10-item variant (Houts and Knoll, 2022). But the most widely used measure of financial knowledge is the Big Three questions on financial literacy that cover inflation, interest rates, and risk created (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011, Lusardi, 2019; Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015). The Big Five questions on financial literacy include the Big Three questions, plus two questions related to the relationship between bond prices and interest rates and the cost of borrowing through a mortgage. A systematic review by Blanco et al. (2022) noted that the Big Three/Five questions on financial literacy are the most widely used measures used of financial knowledge in the United States. Nationally representative surveys such at the HRS, the Understanding American Study, and the National Financial Capability Study have used the Big Three/Five questions to assess objective financial knowledge (Angrisani and Casanova, 2019; Clark and Mitchell, 2022; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011a; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b; Mitchell and Lusardi, 2023; Wann and Burke-Smalley, 2023).

Yakobobski et al. (2018) created a Personal Finance Index (P-Fin Index) to assess financial knowledge in relation to earning, consuming, saving, investing, borrowing, and managing debt, insuring, comprehending risk, and go-to information sources. Another measure related to financial knowledge, the Financial Self-Efficacy Scale (FSES, Lown, 2011), assesses how confident people feel about managing their finances. In addition, the Subjective Financial Knowledge (SFK) measure specifically asks people how confident they feel about their financial knowledge (e.g., Kim & Xiao, 2020, Kim et al., 2019, Nitani et al., 2020).

To assess knowledge about financial planning for retirement, previous studies have asked if the respondent has thought about retirement, at what age they would like to retire, and how much money they would need to retire (Lusardi, 2003; Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011). Similarly, Carr et al. (2015) created a Retirement Planning Score using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79). This score is a combination of the following questions: a) calculated retirement income needed, (like Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011), b) consulted a financial planner, c) read magazines about retirement, d) used a computer to help plan for retirement, or e) attended meetings for retirement planning. Carr et al (2015) coded affirmative answers as 1 and negative answers as 0 and added the answers up to get the scale score.

Another measure related to retirement preparedness was administered by Treger (2022) to young adults (18–25 years old) in an internet survey (Survey Gizmo). Treger (2022) collected information on retirement preparedness and added questions related to the frequency of talking about retirement, the importance of learning about retirement, perceived retirement knowledge compared to peers, and successful retirement compared to parents/grandparents.

Some of the existing retirement knowledge and planning scales are complex and difficult to use with individuals that have low literacy. For example, the Retirement Income Literacy Survey (RILS, Hopkins & Littell, 2016) features 38 items that include complex questions related to financial knowledge.1 In fact, 4 out of 5 older adults in the United States fail this survey. We estimated that the Flesch-Kincaid (1948) grade level for the item stems is 13.2, suggesting that understanding the questions requires more than a high school education.

Our review of the literature indicated a need for a measure of financial planning for retirement that is simple to understand to facilitate efforts to enhance retirement preparedness and diminish racial, ethnic, and gender disparities. A measure of retirement knowledge that is linguistically and culturally appropriate for English- and Spanish-speaking Hispanics is important given that Hispanics, the fastest-growing minority in the United States, lag other racial and ethnic groups in levels of financial literacy, retirement preparedness, and Social Security literacy (Blanco et al., 2017; Richman et al., 2015; Lusardi, 2005). Thus, we discuss next our proposed measure on financial planning for retirement and how our measure contributes to the literature.

3. The Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS)

The Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) is an improved version of the Retirement Knowledge Indicator (RKI) that was administered in a community-based randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the impact of an educational intervention on opening a retirement account (Blanco et al., 2019). The RKI was based on a scale created by Carr et al. (2015) and questions in the HRS that have been associated with knowledge about retirement planning and saving such as those used by Lusardi & Mitchell (2011a, 2011b).

Blanco et al. (2019) educational intervention covered specific concepts related to retirement knowledge, such as compound interest and different types of retirement savings accounts. The intervention also included a visualization exercise of what income would be required to sustain a desired standard of living when reaching retirement age. The retirement planning indicator used in the study was used to assess pre- and post-intervention changes in retirement knowledge. Blanco et al. (2019) administered the measure to 142 mostly Spanish-speaking immigrant women who reported low income and education levels (87% women, 85% immigrants with 67% being Mexican American or Mexican, 70% reported a household income below $30,000, 89% had completed high school or less, 88% were native Spanish speakers, and 53% spoke little to no English). The RKI detected significant improvement in the intervention group on self-reported retirement knowledge. The RKI questions are included in Table A1 in Appendix 1 (Appendices are included as online supplemental material).

The RKS was designed to measure retirement knowledge among English-language and Spanish-language adults that is appropriate for individuals with low levels of education.2 The RKS makes it possible to compare retirement preparedness knowledge among retired and non-retired adults. The RKS expands upon the RKI yes/no response scale by allowing respondents to report the intensity of reflection, engagement, and evaluation of retirement knowledge using polytomous response options. In addition, the RKI is applicable only to non-retired participants while the RKS assesses knowledge for retired and non-retired individuals.

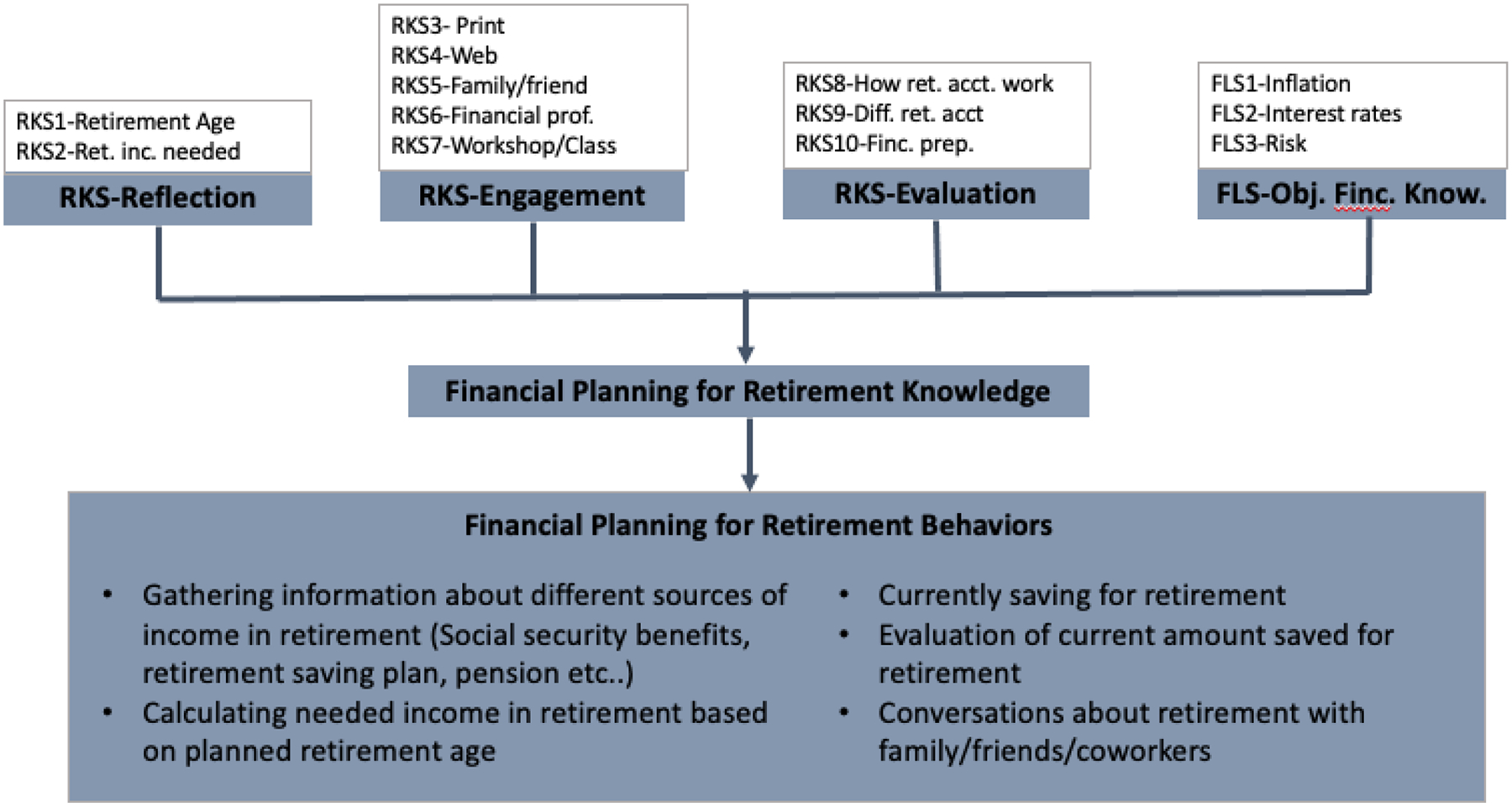

The RKS consists of 10 items that focus on self-assessment of knowledge and engagement with information related to retirement preparedness. Figure 1 shows the different aspects of financial planning for retirement represented in the RKS. The Financial Literacy Score (FLS) represents objective and the RKS subjective financial knowledge relevant for retirement preparedness. Appendix 2 indicates the source of the English and Spanish versions of the RKS and shows the questions included in it.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for the Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS)

The RKS assesses three areas related to retirement knowledge and preparedness:

Reflection about retirement plans (questions 1 and 2)

Engagement with information related to financial planning for retirement (questions 3, 4, 5, 6, & 7)

Evaluation of retirement preparedness (questions 8, 9, and 10)

The first two RKS items assess the extent to which one has reflected on the age at which they would like to retire and on how much they will need to save for retirement. These two questions are usually something people consider as they plan for retirement and might reflect on when they use a retirement saving calculator. The next five RKS items focus on the sources of information people seek when preparing for retirement: in print (book/paper), the internet/web, talking to family and friends, meeting with a financial advisor, and/or attending a class or workshop. The items assess the extent to which people engage with information related to retirement preparedness and their preferred and/or available sources of information. The last three RKS items measure how confident people feel about their retirement knowledge and how prepared they feel for retirement. The evaluation scale questions are specific to financial knowledge relevant to retirement preparedness. These questions indicate the degree to which people feel confident about their understanding of the different types of retirement savings accounts and how retirement savings accounts work. The last question in the scale assesses how confident people feel about their financial preparedness for retirement.

The RKS was designed to assess self-perceived knowledge related to retirement preparedness that can be used across the adult population including those with low levels of literacy. The Flesch-Kincaid grade level for the item stems of the RKS is 6.8 compared to 6.9 for the FLS.

4. Data and Methodology

We use the HRS data from the 2020 wave to evaluate the reliability and validity of the RKS. The HRS is a longitudinal survey that collects data using a complex sample design among a nationally representative sample of older adults 51 years or older. This dataset has extensive information related to health, labor force participation, economic status, family structure, and retirement. HRS data is provided at the individual and household level among individuals and their spouses since 1992.3

The RKS was included as an experimental module in the HRS, where a 10% random sub-sample was invited to participate in a 2–3-minute survey after they completed the core survey. Also included in the experimental module for the RKS were the Big Three questions on financial literacy developed by Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) that have been used to construct a Financial Literacy Scale (FLS).4 The RKS experimental module was answered by 1350 individuals. The 2020 HRS wave data was collected from March 2020 through May 2021.

We use data from the 2020 HRS Core dataset released in May of 2023, in combination with the 2020 RAND HRS “Fat File” released in March of 2023 for all variables used in the analysis. In Appendix 3, Table A2 we provide a description of all the variables used in our analysis and their file source. We also include summary statistics in Appendix Table A.3 for all variables used in this analysis of the full 2020 HRS sample and two subsamples: 1) not included in experimental module 1, and 2) included in experimental module 1. We find no statistically significant difference between the two subsamples for most variables at the 5% level. The only significant difference is that those in the experimental module 1 sample are younger, less likely to be in a nursing home, and have lower levels on satisfaction with their present financial situation, in comparison to those who are not in the experimental module 1.

RKS items are coded so that answers that represent less reflection, engagement, and evaluation of retirement preparedness have lower values. We transformed these responses linearly to a 0–100 possible range, assigning 0 for 1, 33.33 for 2, 66.66 for 3, and 100 for 4. We use the average of the item responses such that RKS scales also have a 0–100 possible range. The FLS items are scored as 0 for incorrect and do not know, and 100 for correct answers.

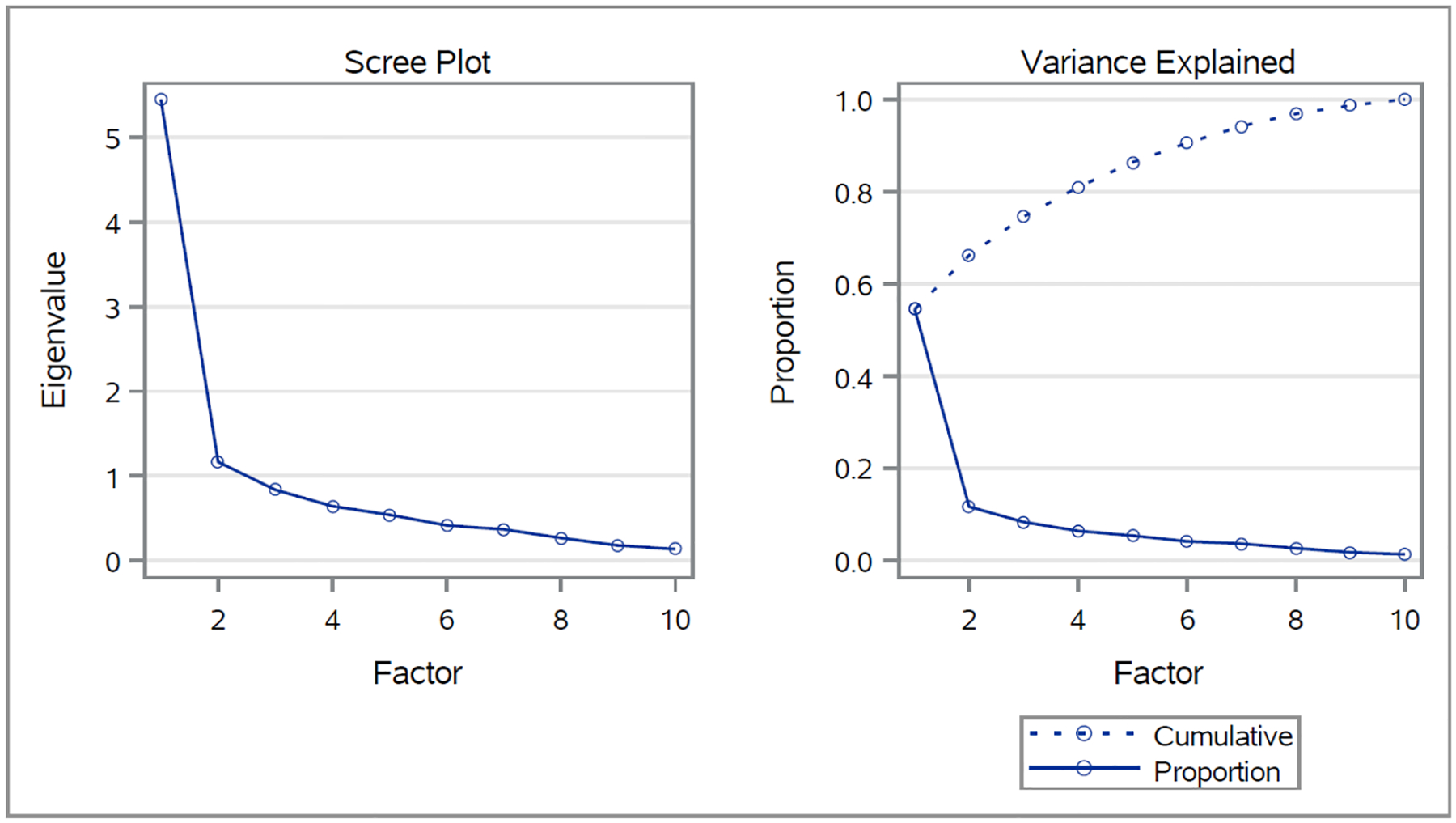

We first examine principal components from polychoric correlations among the 10 RKS items to identify the number of underlying dimensions based on eigenvalues > 1. Then, we estimate a weighted least squares confirmatory factor analysis and examine the goodness of fit with the comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI of 0.90 or larger and RMSEA values of 0.06 or lower are indicative of good practical fit (Bentler and Bonnett, 1980, MacCallum et al., 1996). Next, we evaluate internal consistency reliability (Cronbach, 1951) for multi-item scales in the overall sample and separately for non-retired and retired adults. We evaluate construct validity by estimating associations between the RKS and the FLS based on the following a-priori hypotheses:

H1: More objective financial knowledge (FLS) will be associated with self-assessment of retirement knowledge (RKS).

H2: Better RKS scores will be seen for the retired individuals than the non-retired individuals because those who are retired have been exposed to more information about retirement and are more likely to have had time to reflect on and make decisions about retirement.

H3: Black and Hispanic adults and women will have lower RKS scores than White adults and men. In addition, higher educational attainment and more income will be associated with higher (better) RKS scores.

H4: Financial outcomes (value of financial assets, probability of leaving a 10,000 bequest, and IRA/Keogh, stock, checking, and CD account balances) will be associated with better RKS scores.

H5: Having a longer financial planning horizon (5 to 10 years vs the next few months) will be associated with better RKS scores.

H6: Personality traits related to extroversion, openness, and conscientiousness will be associated with the RKS, such that those individuals who are more extrovert, open, and conscientious will have better RKS scores.

H7: Satisfaction with life, income, personal financial situation, and health will be positively related to RKS scores.

5. Results

Table 1 shows sample characteristics of those in the HRS that completed the RKS experimental module. There is inclusion of different racial and ethnic groups and adults with different educational attainment levels. We note that most of the participants are U.S. born (85%) and answered the survey in English (92%). In addition, 45% were retired, 37% were currently working, and 72% received social security benefits. The average household income was $74,670 and the mean age was 67 years old (34–99 range) among survey participants. Table 1 also includes summary statistics related to financial outcomes and planning horizon, personality traits, and satisfaction with life, income, personal situation, and health.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for Demographic and Socio-Economic Variables

| Obs. | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1347 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1347 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 1347 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 1347 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 |

| Female | 1350 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Couple Household | 1350 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Spanish survey | 1350 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0 | 1 |

| US born | 1350 | 0.85 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 1350 | 67.34 | 10.54 | 34 | 99 |

| Nursing home | 1350 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 1350 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| High school graduate | 1350 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Some college | 1350 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| College grad and above | 1350 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| Working status | 1350 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Retired Status (Survey) | 1350 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income | 1350 | 74.67 | 95.03 | 0 | 1135 |

| Receives social security | 1350 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| Prob. leave bequest $10,000 | 1307 | 65.57 | 39.66 | 0 | 100 |

| IRA/Keogh Acct. Balance | 1350 | 102621 | 285870 | 0 | 2422747 |

| Stocks Acct. Balance | 1350 | 66770 | 350624 | 0 | 4708141 |

| Checking Acct. Balance | 1350 | 30236 | 76002 | 0 | 900000 |

| CD Acct. Balance | 1350 | 6385 | 56717 | 0 | 1700000 |

| Finc. Plan. Hor. (continous) | 1341 | 3.14 | 1.29 | 1 | 5 |

| FP-next few months | 1341 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| FP-next year | 1341 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| FP-next few years | 1341 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 |

| FP-next 5–10 years | 1341 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| FP-greater than 10 years | 1341 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0 | 1 |

| PT. Extrovert | 1129 | 3.17 | 0.57 | 1 | 4 |

| PT. Openness | 1128 | 2.96 | 0.58 | 1 | 4 |

| PT. Conscientiousness | 1129 | 3.37 | 0.49 | 1 | 4 |

| Sat. Health | 1124 | 3.23 | 1.03 | 1 | 5 |

| Sat. Household Income | 1115 | 3.19 | 1.19 | 1 | 5 |

| Sat. Present Financial Situation | 1127 | 3.24 | 1.13 | 1 | 5 |

| Sat. Life as a Whole | 1131 | 4.92 | 1.52 | 1 | 7 |

The principal components from polychoric correlations indicated a substantial first dimension (eigenvalue = 5.45) and a second component with eigenvalue = 1.17. A weighted least squares confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good practical fit for a two-factor model (CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06). The first factor consisted of the seven reflection/engagement with information items with standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.48 to 0.80. The second factor was constituted by the three self-evaluations of knowledge and preparedness items with standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.57 to 0.91. The estimated correlation between the two factors was 0.70, reflecting common variance among the RKS items. See Figure 2 for our factor analysis that provides support for the two factors.

Figure 2.

Factor Analysis of the Retirement Knowledge Scale Items

Based on these results we created a 7-item reflection/engagement scale (coefficient alpha = 0.82) and a 3-item self-evaluation scale (coefficient alpha = 0.80). Table 2 also provides alpha for the 10 RKS items (alpha = 0.86) in the full sample. A reliability coefficient of 0.70 is the threshold often used to indicate a scale is “acceptable” for group (research) comparisons. Table 2 shows the item-test correlations (correlations of the item and the scale score) and item-rest correlations (correlations of each item with scale score without the item included) for the 10-item total scale, 7-item reflection/engagement scale, and 3-item self-evaluation scale. We observe high item-test and item-rest correlations for the RKS items in 10-item total scale, 7-item reflection/engagement scale, and 3-item self-evaluation scale for the full sample. The item-test correlations range between 0.58 and 0.89 and the item-rest correlations range between 0.47 and 0.74.

Table 2.

Item-Scale Correlations for the Retirement Knowledge Scale

| Full Sample | Retired | Non-Retired | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item-test | Item-rest | Item-test | Item-rest | Item-test | Item-rest | ||||

| Obs. | corr. | corr. | Obs. | corr. | corr. | Obs. | corr. | corr. | |

| RKS - 1 through 10 items | |||||||||

| Reflection: Age | 1314 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 603 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 711 | 0.61 | 0.50 |

| Reflection: Money | 1333 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 610 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 723 | 0.66 | 0.56 |

| Engagement: Print source | 1344 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 613 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 731 | 0.73 | 0.65 |

| Engagement: Web | 1345 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 612 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 733 | 0.72 | 0.64 |

| Engagement: Family/friend | 1343 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 610 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 733 | 0.66 | 0.56 |

| Engagement: Finance Professional | 1345 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 611 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 734 | 0.71 | 0.62 |

| Engagement: Workshop/class | 1344 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 611 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 733 | 0.60 | 0.48 |

| Evaluation: How ret. accounts work | 1339 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 609 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 730 | 0.71 | 0.62 |

| Evaluation: Different ret. accounts | 1344 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 612 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 732 | 0.74 | 0.66 |

| Evaluation: Financial preparedness | 1337 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 612 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 725 | 0.57 | 0.46 |

| Coefficient alpha (1–10 items) | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.87 | ||||||

| RKS - 1 through 7 items | |||||||||

| Reflection: Age | 1314 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 603 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 711 | 0.65 | 0.51 |

| Reflection: Money | 1333 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 610 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 723 | 0.72 | 0.59 |

| Engagement: Print source | 1344 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 613 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 731 | 0.77 | 0.66 |

| Engagement: Web | 1345 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 612 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 733 | 0.76 | 0.65 |

| Engagement: Family/friend | 1343 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 610 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 733 | 0.70 | 0.57 |

| Engagement: Finance Professional | 1345 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 611 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 734 | 0.70 | 0.57 |

| Engagement: Workshop/class | 1344 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 611 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 733 | 0.63 | 0.47 |

| Coefficient alpha (1–7 items) | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.83 | ||||||

| RKS - 8 through 10 items | |||||||||

| Evaluation: How ret. accounts work | 1339 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 609 | 0.88 | 0.72 | 730 | 0.89 | 0.73 |

| Evaluation: Different ret. accounts | 1344 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 612 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 732 | 0.89 | 0.73 |

| Evaluation: Financial preparedness | 1337 | 0.77 | 0.51 | 612 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 725 | 0.75 | 0.47 |

| Coefficient alpha (8–10 items) | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.80 | ||||||

Item-test correlation is the correlation of the item and the scale score.

Item-rest correlation is the correlation of the item with the scale score without the item included.

In Table 2 we also provide coefficient alpha and item-rest correlations for the 10-item total scale, 7-item reflection/engagement scale, and 3-item self-evaluation scale in the retired and non-retired subgroups. Cronbach’s coefficient alpha is very similar same for these subgroups as for the full sample, with a 0.01 variability in some cases. The item-test and item-rest correlations are also similar across these subgroups. These results provide evidence of the reliability of our measure in assessing retirement knowledge similarly across retired and non-retired adults.

Tables 3 and 4 present product-moment and polychoric correlations among RKS and FLS items and between the FLS and the RKS scales.5 All 10 items of the RKS were significantly correlated with one another, with the average product-moment correlation being 0.38 (0.20–0.78 range). In Table 3 we see that the items of the RKS had a statistically significant correlation at the 1% level with the FLS items and the average correlation was 0.15 (0.08–0.28 range). Table 3 shows that polychoric correlations were consistent with product- moment correlations. The statistically significant correlation between the RKS items with the FLS items indicates that self-assessment of reflection, engagement, and evaluation of retirement preparedness is correlated with objective financial knowledge.

Table 3.

Correlations Between Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) and Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) Items

| RKS_1 | RKS_2 | RKS_3 | RKS_4 | RKS_5 | RKS_6 | RKS_7 | RKS_8 | RKS_9 | RKS_10 | FL_1 | FL_2 | FL_3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retirement knowledge Scale (RKS) | |||||||||||||

| Self-reflection: Age (RKS_1) | 1 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Self-reflection: Money (RKS_2) | 0.54*** | 1 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Engagement: Print source (RKS_3) | 0.33*** | 0.45*** | 1 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| Engagement: Web (RKS_4) | 0.35*** | 0.45*** | 0.65*** | 1 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.32 |

| Engagement: Family/friend (RKS_5) | 0.35*** | 0.39*** | 0.44*** | 0.42*** | 1 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.27 |

| Engagement: Finance Professional (RKS_6) | 0.26*** | 0.37*** | 0.45*** | 0.42*** | 0.41*** | 1 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.38 |

| Engagement: Workshop/class (RKS_7) | 0.20*** | 0.26*** | 0.43*** | 0.39*** | 0.29*** | 0.46*** | 1 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.26 |

| Self-evaluation: Ret. account work (RKS_8) | 0.30*** | 0.33*** | 0.43*** | 0.39*** | 0.32*** | 0.43*** | 0.32*** | 1 | 0.85 | 0.56 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.33 |

| Self-evaluation: Diff. ret. Account (RKS_9) | 0.31*** | 0.37*** | 0.46*** | 0.42*** | 0.35*** | 0.47*** | 0.33*** | 0.78*** | 1 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.37 |

| Self-evaluation: Fin. Preparedness (RKS_10) | 0.22*** | 0.26*** | 0.27*** | 0.22*** | 0.29*** | 0.38*** | 0.25*** | 0.48*** | 0.49*** | 1 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.33 |

| Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) | |||||||||||||

| Financial literacy: Inflation | 0.12*** | 0.10*** | 0.14*** | 0.12*** | 0.08*** | 0.10*** | 0.08*** | 0.15*** | 0.15*** | 0.16*** | 0.12*** | 0.09 | 0.30 |

| Financial literacy: Interest rate | 0.14*** | 0.14*** | 0.15*** | 0.14*** | 0.14*** | 0.17*** | 0.09*** | 0.16*** | 0.18*** | 0.11*** | 0.16*** | 1 | 0.17 |

| Financial literacy: Risk | 0.13*** | 0.15*** | 0.21*** | 0.22*** | 0.19*** | 0.25*** | 0.16*** | 0.24*** | 0.28*** | 0.24*** | 0.16*** | 0.11* | 1 |

Product-moment correlations are below the diagonal; polychoric correlations are above the diagonal. N= 1351.

Significance denoted as *p<0.10 **p<0.05, ***p<0.01

Table 4.

Correlations between Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) and Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS)

| FLS | RKS | Reflections scale | Engagement scale | Evaluation scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLS | 1 | ||||

| RKS total scale | 0.36*** | 1 | |||

| RKS Reflections scale | 0.23*** | 0.74*** | 1 | ||

| RKS Engagement scale | 0.31*** | 0.91*** | 0.53*** | 1 | |

| RKS Evaluation scale | 0.34*** | 0.78*** | 0.40*** | 0.56*** | 1 |

Product-moment correlations are below the diagonal. N= 1351.

Significance denoted as *p<0.10 **p<0.05, ***p<0.01

Table 4 shows that the FLS and RKS overall scales are significantly correlated (r = 0.36). Correlations of the FLS with RKS scales range from 0.23 to 0.34. There are also statistically significant correlations among the RKS scales, where the mean, maximum and minimum correlations are 0.65, 0.91, and 0.40, respectively. The significant correlation between the RKS and FLS provides support for the construct validity of the RKS. Both measures are correlated but are measuring not redundant. The significant correlation between the RKS and the FLS provides support for our Hypothesis 1 for the construct validity of our proposed measure.

Table 5 provides summary statistics for the RKS and FLS items and scales (all scored on a 0–100 possible range) for the full sample and for the retired and non-retired subsamples. We also include in Table 5 the mean differences between the non-retired and retired groups and t-tests of the significance of differences. For the full sample, we observe the FLS has a mean of 66 and the RKS a mean of 38. The largest mean value for the RKS scales is for reflection (59), followed by evaluation (41) and engagement (27).

Table 5.

Summary Statistics for the Retirement Knowledge Scale and Financial Literacy Scale Items, Scales for Full sample, and Retired and Non-retired Subgroups

| Full Sample in Module 1 | Retired | Non-retired | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obs. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | Mean | NR-R | p-val. | |

| Retirement Knowledge Scale Items | |||||||

| Reflection: What age | 1314 | 59.26 | 41.42 | 60.42 | 58.27 | −2.15 | 0.35 |

| Reflection: How much money | 1333 | 59.54 | 42.74 | 56.12 | 62.43 | 6.30 | 0.01 |

| Engagement: Print source | 1344 | 37.82 | 39.72 | 39.80 | 36.16 | −3.64 | 0.09 |

| Engagement: Web | 1345 | 25.72 | 37.52 | 22.17 | 28.69 | 6.53 | 0.00 |

| Engagement: Family/friend | 1343 | 33.95 | 38.85 | 33.66 | 34.20 | 0.54 | 0.80 |

| Engagement: Finance Professional | 1345 | 24.61 | 36.19 | 27.11 | 22.52 | −4.59 | 0.02 |

| Engagement: Workshop/class | 1344 | 13.99 | 25.75 | 16.31 | 12.05 | −4.26 | 0.00 |

| Evaluation: How ret. saving accounts work | 1339 | 37.91 | 32.59 | 41.27 | 35.11 | −6.16 | 0.00 |

| Evaluation: Different types of ret. savings | 1344 | 35.64 | 30.80 | 39.22 | 32.65 | −6.57 | 0.00 |

| Evaluation: Financial preparedness | 1337 | 49.09 | 34.65 | 58.66 | 41.01 | −17.65 | 0.00 |

| Retirement Knowledge Scales | |||||||

| Reflections scale | 1343 | 59.22 | 37.22 | 58.08 | 60.18 | 2.11 | 0.30 |

| Engagement scale | 1348 | 27.20 | 26.60 | 27.82 | 26.68 | −1.14 | 0.43 |

| Evaluation scale | 1348 | 40.87 | 27.70 | 46.42 | 36.23 | −10.18 | 0.00 |

| Total Scale | 1350 | 37.63 | 24.14 | 39.44 | 36.12 | −3.32 | 0.01 |

| Financial Literacy Scale | |||||||

| Inflation item | 1307 | 70.24 | 45.74 | 72.93 | 68.02 | −4.91 | 0.05 |

| Interest rate item | 1311 | 66.82 | 47.10 | 63.30 | 69.74 | 6.44 | 0.01 |

| Risk item | 1302 | 60.83 | 48.83 | 60.54 | 61.07 | 0.53 | 0.84 |

| Total Scale | 1331 | 65.94 | 30.88 | 65.57 | 66.25 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

| N | 1350 | 614 | 736 | ||||

Minimum and maximum observed scores were 0 and 100, respectively.

Full sample includes all of those for which there was data on the retirement knowledge total scale.

Retired sample includes those who answered the survey for retired participants.

Non-retired sample includes those who answered the survey for participants who have non-retired yet.

There are interesting insights that help us understand better where people are in their retirement preparedness journey, how they reflect and engage with information related to retirement preparedness and evaluate their knowledge and preparedness. In relation to reflecting on retirement age and how much money will be needed, we show that 59% of those in the full sample have thought about it. The means for different forms of engagement with information related to retirement suggest that printed sources were more popular than family and friends, and web sources (38 versus 34 and 26). Also, participants reported being less likely to engage with a finance professional (25) and less likely to attend a workshop or a class on retirement planning (14). Among the components of the RKS scale on evaluation, the highest mean was for self-assessment of retirement preparedness (49). The means for the individual’s self-assessment of how retirement saving accounts work and the different types are lower (38 and 36) than self-assessment of retirement preparedness. The mean for the FLS total scale is 66, with 70% answering the inflation question correctly, 67% the interest rate question correctly, and 61% the risk question correctly.

Table 5 shows that the difference between non-retired and retired groups on the RKS total scale and most of its items are statistically significant—only reflection about what age they would like to retire and engagement with information about retirement with family and friends are not statistically significantly different across these two groups. In fact, the means for the reflection and engagement scale are not statistically significantly different between retired and non-retired adults. For most of the RKS items, retired adults score higher, as hypothesized. But those non-retired are more likely to reflect on how much money they need for retirement and more likely to look at information from the Web than retired adults. On the other hand, retired adults are more likely to engage with a finance professional, attend a workshop or class, in comparison to non-retired adults. Retired participants are also more likely to have higher scores than non-retired adults for their self-evaluation on knowledge about how retirement savings account work and the different types of retirement accounts, and their financial preparedness for retirement. Thus, the estimates shown in Table 5 provide support for our Hypothesis 2, where hypothesize that retired participants will score higher on the RKS, in comparison to non-retired participants.

The FLS is not statistically significantly different between retired and non-retired adults. While the inflation and interest rate questions are statistically significantly different across groups at the 5% level, the risk question is not statistically significantly different.

Table 6 provides product-moment correlations of the RKS and FLS scales with individual sociodemographic characteristics. We find that the RKS is negatively correlated with being Black and Hispanic but positively correlated with being White and born in the United States. The RKS is also negatively correlated with being female and answering the survey in Spanish. While lower levels of education are negatively correlated with the RKS, higher levels are positively correlated with the RKS. Household income, working and retired status are all positively correlated with the RKS. Surprisingly, receiving social security and age are negatively correlated with the RKS. Thus, correlations in Table 6 provide support for Hypothesis 3.

Table 6.

Product-moment Correlations of the Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) and Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) with Individual Demographic Characteristics

| RKS | Scale Reflection | Scale Engagement | Scale Evaluation | FLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 0.21*** | 0.16*** | 0.11*** | 0.30*** | 0.26*** |

| Black, non-Hispanic | −0.08*** | −0.05** | −0.03 | −0.15*** | −0.16*** |

| Hispanic | −0.20*** | −0.15*** | −0.13*** | −0.24*** | −0.17*** |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Female | −0.11*** | −0.05* | −0.06** | −0.18*** | −0.15*** |

| Couple Household | 0.19*** | 0.10*** | 0.17*** | 0.18*** | 0.13*** |

| Spanish survey | −0.18*** | −0.12*** | −0.12*** | −0.21*** | −0.15*** |

| US born | 0.14*** | 0.10*** | 0.07*** | 0.18*** | 0.10*** |

| Age | −0.07*** | −0.13*** | −0.12*** | 0.10*** | −0.05* |

| Nursing home | −0.03 | 0 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | −0.33*** | −0.21*** | −0.28*** | −0.33*** | −0.23*** |

| High school graduate | −0.11*** | −0.08*** | −0.11*** | −0.07** | −0.11*** |

| Some college | 0.06** | 0.08*** | 0.04 | 0.05* | 0.05* |

| College grad and above | 0.35*** | 0.19*** | 0.32*** | 0.32*** | 0.28*** |

| Working status | 0.15*** | 0.17*** | 0.15*** | 0.05* | 0.12*** |

| Retired Status (Survey) | 0.07** | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.18*** | −0.01 |

| Household income | 0.32*** | 0.19*** | 0.28*** | 0.30*** | 0.23*** |

| Receives social security | −0.15*** | −0.17*** | −0.15*** | −0.03 | −0.12*** |

Significance denoted as *p<0.10 **p<0.05, ***p<0.01

In Table 7 we provide correlations of the RKS and the FLS with variables related to Hypotheses 4, 5, 6 and 7. There is a positive and significant correlation between the RKS and the financial wellbeing variables related to the probability of leaving a bequest of $10,000 or more, and balance in IRA/Keogh, stock, checking, and CD accounts (Hypothesis 4). The FLS and RKS scales are also positively and significantly correlated to all of these variables in most cases (correlation is not significant between the CD account balance and the RKS reflection scale and the FLS), which provides support for Hypothesis 4.

Table 7.

Product-moment Correlations of the Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) and Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) with financial, personality and wellbeing variables

| RKS | Scale Reflection |

Scale Engagement |

Scale Evaluation |

FLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prob. leave bequest $10,000 | 0.36*** | 0.17*** | 0.29*** | 0.44*** | 0.25*** |

| IRA/Keogh Acct. Balance | 0.31*** | 0.15*** | 0.25*** | 0.37*** | 0.20*** |

| Stocks Acct. Balance | 0.19*** | 0.08*** | 0.16*** | 0.22*** | 0.12*** |

| Checking Acct. Balance | 0.20*** | 0.08*** | 0.14*** | 0.29*** | 0.17*** |

| CD Acct. Balance | 0.07*** | 0.03 | 0.06** | 0.10*** | 0.04 |

| Finc. Plan. Hor. (continuous) | 0.14*** | 0.08*** | 0.12*** | 0.15*** | 0.10*** |

| FP-next few months | −0.16*** | −0.11*** | −0.13*** | −0.16*** | −0.09*** |

| FP-next year | −0.05* | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.06** | −0.02 |

| FP-next few years | 0.04 | 0.06** | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 |

| FP-next 5–10 years | 0.15*** | 0.10*** | 0.12*** | 0.15*** | 0.10*** |

| FP-greater than 10 years | −0.03 | −0.05* | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0 |

| PT. Extrovert | 0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.10*** | 0.14*** | 0 |

| PT. Openness | 0.24*** | 0.15*** | 0.21*** | 0.24*** | 0.14*** |

| PT. Conscientiousness | 0.20*** | 0.11*** | 0.17*** | 0.21*** | 0.11*** |

| Sat. Health | 0.13*** | 0 | 0.10*** | 0.20*** | 0.10*** |

| Sat. Household Income | 0.17*** | −0.01 | 0.10*** | 0.33*** | 0.14*** |

| Sat. Present Finc. Situation | 0.16*** | −0.02 | 0.09*** | 0.33*** | 0.14*** |

| Sat. Life as a Whole | 0.17*** | 0.05 | 0.12*** | 0.24*** | 0.06** |

Significance denoted as *p<0.10 **p<0.05, ***p<0.01

We also look at how the RKS correlates with the financial planning horizon of the individual, where we provide support for Hypothesis 5. In Table 7 we show that the RKS, RKS scales and FLS are negatively correlated with financial planning horizon of next few months. We also observe that all measures in Table 7 are positively correlated with a financial planning horizon of five to 10 years.

We look at how the RKS, RKS scales, and FLS correlate with personality traits that are more conducive to engaging with information about retirement, reflecting about retirement, and making future plans for retirement. These correlations provide support for our Hypothesis 6. The RKS is positively correlated with extroversion, openness, and conscientiousness. While all the scales and scales are positive and significantly correlated with being open and conscientious, being an extrovert is not correlated with the reflection scale and the FLS.

Finally, we look at how the RKS is correlated with satisfaction with health, household income, present financial situation, and life as a whole. As noted in our Hypothesis 7, we expect that higher levels of satisfaction will be positively correlated with the RKS. Table 7 correlations provide support for this hypothesis, where the RKS and the RKS scales engagement and evaluation, and the FLS have a positive and significant correlation at least at the 5% level will all satisfaction-related variables. Interestingly, the RKS reflection scale has no correlation with the satisfaction related variables.

We perform a multiple regression analysis to provide further support to our Hypothesis 2 and 3. We consider the RKS total scale, RKS subscales and FLS as dependent variables and include as independent variables socio-economic and demographic characteristics. Table 8 provides the coefficients for the variables considered our analysis using an Ordinary Least Square estimator with robust standard errors. We observe in Table 8 that retired status and household income are positively associated with the RKS total scale and subscales (all significant at least at the 5% level). As expected, lower levels of education being a minority (Black and Hispanic) is associated with lower values for the total scale and subscales in most cases.

Table 8.

Multiple Regression Analyses of Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) Total Scale and Subscales, and Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) as Dependent Variables

| RKS | Reflection Scale | Engagement Scale | Evaluation Scale | FLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retired Status (Survey) | 10.52 | 10.69 | 9.41 | 11.29 | 0.97 |

| (6.29)** | (3.57)** | (5.02)** | (5.85)** | (0.42) | |

| Spanish survey | −3.62 | −1.52 | −3.78 | −4.88 | −3.07 |

| (1.29) | (0.30) | (1.19) | (1.60) | (0.75) | |

| Age | −0.29 | −0.58 | −0.36 | 0.03 | −0.16 |

| (3.85)** | (4.29)** | (4.23)** | −0.36 | −1.56 | |

| Female | −2.13 | −0.90 | 0.23 | −6.31 | −6.75 |

| (1.76) | (0.44) | (0.16) | (4.57)** | (4.14)** | |

| Couple Household | 4.61 | 2.17 | 4.48 | 6.13 | 1.46 |

| (3.10)** | (0.88) | (2.55)* | (3.61)** | (0.74) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | −4.71 | −8.57 | −1.01 | −8.41 | −14.57 |

| (3.34)** | (3.49)** | (0.63) | (5.11)** | (7.04)** | |

| Hispanic | −7.59 | −15.32 | −2.82 | −10.65 | −13.55 |

| (3.47)** | (4.11)** | (1.10) | (4.42)** | (4.10)** | |

| Other, non-Hispanic | −7.47 | −12.60 | −5.77 | −7.65 | −8.96 |

| (2.50)* | (2.50)* | (1.56) | (2.34)* | (2.38)* | |

| Less than high school | −20.95 | −17.25 | −22.02 | −21.72 | −20.19 |

| (11.90)** | (5.68)** | (10.90)** | (10.83)** | (8.32)** | |

| High school graduate | −13.29 | −11.39 | −14.41 | −12.59 | −15.82 |

| (7.67)** | (4.15)** | (7.13)** | (6.47)** | (7.30)** | |

| Some college | −7.99 | −3.55 | −9.93 | −7.66 | −8.52 |

| (4.79)** | (1.37) | (4.89)** | (4.14)** | (4.10)** | |

| Working status | 5.51 | 9.19 | 4.72 | 4.16 | 1.17 |

| (3.42)** | (3.17)** | (2.55)* | (2.32)* | (0.54) | |

| Household income | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| (4.35)** | (1.99)* | (3.67)** | (4.64)** | (3.05)** | |

| Receives social security | −3.24 | −5.87 | −2.68 | −2.17 | −3.76 |

| (1.94) | (2.14)* | (1.35) | (1.19) | (1.75) | |

| Financial respondent | 1.45 | 0.41 | 0.74 | 3.20 | 0.83 |

| (0.95) | (0.17) | (0.41) | (1.89) | (0.42) | |

| Nursing Home | −5.14 | 9.49 | −5.90 | −10.52 | −13.73 |

| (1.35) | (0.98) | (1.25) | (1.57) | (1.65) | |

| Constant | 60.66 | 104.09 | 54.11 | 42.52 | 96.33 |

| (11.20)** | (10.70)** | (8.74)** | (6.56)** | (13.05)** | |

| R 2 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.19 |

| N | 1347 | 1340 | 1345 | 1345 | 1328 |

Robust standard errors in parenthesis. Significance denoted as *p<0.10 **p<0.05, ***p<0.01 Reference group for categorical variables: Whites (race/ethnicity) and college graduate and above (education).

Interestingly age is negatively associated with retirement knowledge, for the total scale and the reflection and engagement scale. This finding might be due to the high correlation between age and retirement status (correlation equals 0.64). We find that being female is only negatively associated with the evaluation scale. Working status is positively associated with the total the reflection scales. For the associations between objective financial knowledge measured with the FLS, we find similar findings, where women, Blacks, Hispanics and those with lower levels of education are likely to have lower scores. Household income is positively associated with FLS as expected.

To evaluate the robustness of our findings about our measure being consistent across retired and non-retired individuals, we also conduct a multiple regression analysis where we interact the retirement status with gender, couple household, household income, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. We find that only the interaction of the female dummy variable with the retirement status dummy variable is statistically significant at the 5 percent level for the reflection scale. We find similar results when we include all interactions in the same model.6

We also conducted a multiple regression analysis to provide further support for Hypotheses 4 and 5, where we included financial outcomes related to retirement preparedness as dependent variable and our scales as independent variables. Table 9 shows the coefficients for the total scale and subscales included as independent variables for the estimation of the model separately using as dependent variable each financial outcome. We also estimate the model using the financial planning horizon variable as dependent variable to evaluate how retirement knowledge measured with our scale predicts financial planning horizons. We include all independent variables shown in Table 8 as independent variables in these estimations, but we include only coefficients for our scales for purpose of space.7

Table 9.

Multiple Regression Analyses of Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) Total Scale and Subscales, and Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) as Independent Variables

| RKS Total | RKS Reflection | RKS Engagement | RKS Evaluation | FLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: IRA/Keogh Account Balance | |||||

| Coefficient | 2100.20 | 442.65 | 1314.22 | 2527.87 | 633.61 |

| Standard Error | (5.50)** | (2.18)* | (3.64)** | (7.32)** | (2.82)** |

| R2 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| N | 1347 | 1340 | 1345 | 1345 | 1328 |

| Dependent variable: Stocks Account Balance | |||||

| Coefficient | 1851.67 | 336.02 | 1383.26 | 1919.79 | 580.74 |

| Standard Error | (3.05)** | (1.27) | (2.45)* | (4.76)** | (2.47)* |

| R2 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| N | 1347 | 1340 | 1345 | 1345 | 1328 |

| Dependent variable: Probability leave bequest of $10,000 or more | |||||

| Coefficient | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.12 |

| Standard Error | (7.18)** | (2.04)* | (5.39)** | (9.96)** | (3.26)** |

| R2 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.25 |

| N | 1304 | 1298 | 1302 | 1302 | 1289 |

| Dependent variable: Financial Planning Horizon | |||||

| Coefficient | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| Standard Error | (3.62)** | (1.73) | (3.19)** | (3.56)** | (1.98)* |

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| N | 1338 | 1333 | 1336 | 1336 | 1320 |

Robust standard errors in parenthesis.

Significance denoted as *p<0.10 **p<0.05, ***p<0.01.

All estimations include the following control variables: retired status, Spanish survey, age, female, couple household, race/ethnicity dummy variables (Black, Hispanic, other non-Hispanic; White is the reference group, educational attainment dummy variables (less than high school, high school graduate, some college; college and above as reference group), working status, household income, receives social security, financial respondent, and nursing home.

In Table 9 we observe that the RKS total scale and evaluation scale are positively and significantly associated with all dependent variables at the 5% significance level. The engagement scale is positively and significantly associated with at the 5 % level with all dependent variables, but the stock account balance. The FLS is positively and significantly associated with the IRA/Keogh account balance and the probability of leaving a bequest of $10,000 or more. Interestingly, the reflection scale only seems to be marginally positively associated at the 10 % level with the IRA/Keogh account balance and the probability of leaving a bequest of $10,000 or more. Therefore, this multiple regression analysis shows that the RKS total scale and subscales are good predictors of financial outcomes associated with higher levels of financial planning and retirement preparedness.

6. Conclusion

We find support for the reliability and validity of the RKS in assessing self-reported reflection on retirement plans, engagement with retirement preparedness information, and self-evaluation of retirement knowledge related concepts and retirement preparedness among older adults. The RKS can be used in the future to measure progress on improving retirement knowledge and preparedness among U.S. adults. Data collected through the application of the RKS can also be helpful for assessing gender, racial, and ethnic disparities on reflection, engagement and evaluation of retirement knowledge and preparedness. Data from the RKS can help to better understand where the information gaps are in relation to retirement preparedness, which can be helpful with the purpose to improve and reduce racial, ethnic and gender gaps in retirement preparedness in the U.S.

We also see the application of the RKS as a measure to include in financial education programs that aim at improving financial knowledge and money management skills specific to retirement preparedness. The RKS can be used before and after implementation of an educational program, which will help measuring any changes on retirement knowledge the program participant makes after being exposed to the intervention.

We also caution that our analysis is based on randomly selected subsample from the HRS, and the respondents to the HRS experimental module is not representative of the U.S. population. Our sample was concentrated in adults 51 years and older. For future research, we suggest administering the RKS to a larger sample that can provide national representation, and that includes working age younger adults (25 to 54 years old). Working with a nationally representative sample and including younger cohorts will be beneficial to measure retirement knowledge in the United States so that we are more equipped on understanding where the knowledge gaps are and improve retirement preparedness among all groups, but especially among women and minority groups.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sylvia Paz for input about the Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) and Helen Levy, Associate Director for the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), for her feedback about including the RKS in the HRS. Luisa R. Blanco and Ron D. Hays received support from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG021684, and from the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) under NIH/NCATS Grant Number UL1TR001881. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, Pepperdine University or UCLA. All errors are our own.

Appendix 1

Table A1. Questions for the Retirement Knowledge Indicator (RKI).

Instructions: For the following questions, please respond by circling yes or no.

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you know how saving accounts work and how money grows over time in these accounts? | Yes | No |

| 2. Do you know what you have to do to plan for retirement? | Yes | No |

| 3. Do you know the different types of plans for retirement savings or retirement available? | Yes | No |

| 4. Have you talked to a family member or friend about planning for retirement and ways to prepare? | Yes | No |

| 5. Have you obtained information about planning for retirement in a book, magazine or brochure? | Yes | No |

| 6. Have you obtained information about planning for retirement through a computer or cellphone using the Internet? | Yes | No |

| 7. Have you consulted with financial advisor on how to plan for retirement person? | Yes | No |

| 8. Have you obtained information about planning for retirement in a workshop? | Yes | No |

| 9. Have you ever thought what age you plan to retire? | Yes | No |

| 10. Have you ever tried to calculate how much you would have to save for retirement? | Yes | No |

Blanco et al. (2019) calculated the RKI assigning a value of 1 for a yes response, zero otherwise, and adding all values. The RKI value ranges from 0 to 10.

Appendix 2. Description and Availability of the Retirement Knowledge Scale

The Retirement knowledge Scale (RKS) was designed to measure retirement knowledge among low- and moderate-income, English- and Spanish-speakers, and retired and non-retired individuals. The RKS was included in the Health Retirement Study (HRS) experimental module in the 2020 wave. For more information on the HRS experimental modules go to the HRS website:

https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/documentation/modules

You can find the instrument of the RKS used by HRS:

The RKS assesses three areas related to retirement knowledge and preparedness:

Reflection about retirement plans (questions 1 and 2)

Engagement with information related to retirement planning (questions 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7)

Evaluation of retirement preparedness (questions 8, 9 and 10)

The RKS was designed to be comparable across retired and non-retired individuals. Higher scores represent greater levels of self-reflection, engagement, and self-evaluation. We transformed the 1–4 coding of item responses to a 0–100 possible range: 0–100 score = (original integer – 1)*100/3. So, 1 is recoded to 0, 2 to 33.3333, 3 to 66.6666, and 4 is recoded to 100. RKS scale scores are the average of the recoded item scores. This percentage of total scoring approach is analogous to financial literacy measures that are scored 0 for incorrect and do not know, and 100 for correct answers.

RKS Items Questions and Responses for retired and non-retired

| Question for retired participant: Before you retired, how often did you… Question for not-retired participant: How often have you… |

| 1. think about the age you expected to retire? |

| 2. think about how much money you needed to save for retirement? |

| 3. read in a brochure, magazine, or book about how to plan for retirement? |

| 4. read on the Web/internet about how to plan for retirement? |

| 5. talk to a family member or a close friend about how to plan for retirement? |

| 6. talk to a finance professional about how to plan for retirement? |

| 7. attend a workshop or class about financial planning for retirement? |

Answers: 1. Never (1) 2.One time (2), 3.Two to three times (3), 4. Four or more times(4)

| Question for retired participant: Before you retired, how much did you know about… Question for not-retired participant: How much do you know about… |

| 8. how retirement savings accounts work? |

| 9. different types of retirement savings plans? |

Answers: 1. Nothing at all (1) 2.A little (2), 3.Somewhat (3), 4. A great deal(4)

| Question for retired participant: Before you retired, how well prepared financially were you for retirement? Question for not-retired participant: How well prepared financially are you for retirement? |

| 10. how retirement savings accounts work? |

Answers: 1. Not prepared at all (1) 2.A little prepared (2), 3.Somewhat prepared (3), 4.Very prepared (4)

Appendix 3

Table A2.

Description of Variables Included in this Analysis

| Variable name in analysis | Variable name in HRS | Variable description |

|---|---|---|

| Source: 2020 RAND HRS Fat File | ||

| Race/Ethicity: 4 groups | raracem, rahispan | Using the two variables about race and ethnicity, we constructed four dummy variables: 1) White, non-Hispanic adult equal to 1, zero otherwise; 2) Black non-Hispanic adult equal to 1, zero otherwise, 3) Hispanic adult equal to 1, zero otherwise, and 4) Other equal to 1, zero otherwise. We refer in paper to Whites to Whites non-Hispanics and Blacks to Blacks non-Hispanics for simplicity. |

| Female | ragender | We classify gender groups as men and women. We created a dummy variable Female equal 1, zero otherwise. |

| US born | rabplace | Dummy variable constructed as equal to 1 if born in US, zero otherwise. |

| Age | rage | Age of respondent (continuous variable). |

| Educational attainment: 4 groups | raeduc | Dummy variables constructed for 4 different groups of educational attainment: Less than Highschool, High school graduate, Some college, College grad and above. |

| Working status | rwork | Dummy variable equal to 1 if working for pay, equal to zero if otherwise. |

| Household income | hitot | Continuous variable constructed as Income in thousands (hittot/1000). |

| Receives social security | rassrecv | Dummy variable equal to 1 if someone in household receives social security benefits. |

| Prob. leave bequest $10,000 | rbeq10k | Probability of leaving a bequest of $10,000 or more (continuous variable with probabilities ranging from 0 to 100). |

| IRA/Keogh Acct. Balance | haira | Net value of Individual Retirement Accounts (IRA) and/or Keogh accounts in household (self, husband/wife/partner, continuous variable). |

| Stocks Acct. Balance | hastck | Net value of stocks, mutual funds and investment trusts in household (self, husband/wife/partner, continuous variable). |

| Checking Acct. Balance | hachck | Net value of Individual Retirement Accounts (IRA) and/or Keogh accounts in household (self, husband/wife/partner, continuous variable). |

| CD Acct. Balance | hacd | Value of checking, savings, or money market accounts in household (self, husband/wife/partner, continuous variable). |

| Finc. Plan. Hor.: 5 groups | rfinpln | Financial planning horizon dummy variables constructed for 5 financial planning horizons: 1) next few months, 2) next year, 3) next few years, 4) next 5–10 years, and 5) greater than 10 years. |

| PT. Extrovert | rlbext | Continuous variable from the big 5 personality traits, extroversion. |

| PT. Openness | rlbopen | Continuous variable from the big 5 personality traits, openness to experience. |

| PT. Conscien-tiousness | rlbcon5 | Continuous variable from the big 5 personality traits, conscientiousness (5 sub-items). |

| Sat. Health | rlbsathlth | Continuous variable for satisfaction with health. |

| Sat. Household Income | rlbsatinc | Continuous variable for satisfaction with total household income. |

| Sat. Present Finc. Situation | rlbsatfin | Continuous variable for satisfaction with present financial situation. |

| Sat. Life as a Whole | rlbsatwlf | Continuous variable for life satisfaction scale. |

| Source: 2020 HRS Core | ||

| Couple Household | RCOUPLE | We classify households as coupled households if married or partnered. |

| Spanish survey | RA012 | Language for survey, where Spanish survey dummy variable is equal to 1 if survey answered in Spanish, zero if answered in English. HRS survey is only available in English and Spanish. |

| Nursing home | RA028 | Whether individual is in nursing home, equal to 1 if individual resides in nursing home, equal to zero otherwise. |

| Retired Status (Survey) | RJ005M1 | Whether individual reported being retired and given the retired survey for the experimental module 1. Equal to 1 if individual responded retired to their current employment status, equal to zero otherwise. |

| Source: 2020 HRS Experimental Module 1 | ||

| Retirement Knowledge Scale (RKS) | Constructed | We constructed the RKS as the mean of all RKS items. All responses for the RKS items were transformed linearly to a 0–100 possible range, assigning 0 for 1, 33.33 for 2, 66.66 for 3, and 100 for 4. Please refer to HRS webpage for routing document for survey questions: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/meta/2020/core/qnaire/online/Module1_Retirement_2020B-A.pdf |

| Self-reflection: Age (RKS_1) | RV101 | Reflection about retirement age (how often). Variable with values 1–4, 1=never, 2=one time, 3=two or three times, 4=four or more times. |

| Self-reflection: Money (RKS_2) | RV102 | Reflection about how much money you would need to save for retirement (how often). Variable with values 1–4, 1=never, 2=one time, 3=two or three times, 4=four or more times. |

| Engagement: Print source (RKS_3) | RV103 | Engagement with information about retirement, printed source (how often). Variable with values 1–4, 1=never, 2=one time, 3=two or three times, 4=four or more times. |

| Engagement: Web (RKS_4) | RV104 | Engagement with information about retirement, web/internet (how often). Variable with values 1–4, 1=never, 2=one time, 3=two or three times, 4=four or more times. |

| Engagement: Family/friend (RKS_5) | RV105 | Engagement with information about retirement, family/friends (how often). Variable with values 1–4, 1=never, 2=one time, 3=two or three times, 4=four or more times. |

| Engagement: Finance professional (RKS_6) | RV106 | Engagement with information about retirement, finance professional (how often). Variable with values 1–4, 1=never, 2=one time, 3=two or three times, 4=four or more times. |

| Engagement: Workshop/class (RKS_7) | RV107 | Engagement with information about retirement, attended workshop/class (how often). Variable with values 1–4, 1=never, 2=one time, 3=two or three times, 4=four or more times. |

| Self-evaluation: Ret. account work (RKS_8) | RV108 | Evaluation of knowledge about how retirement savings accounts work. Variable with values 1–4, 1=nothing at all, 2=a little, 3=some, 4=a great deal. |

| Self-evaluation: Diff. ret. Account (RKS_9) | RV109 | Evaluation of knowledge about different types of retirement savings accounts. Variable with values 1–4, 1=nothing at all, 2=a little, 3=some, 4=a great deal. |

| Self-evaluation: Fin. Preparedness (RKS_10) | RV110 | Evaluation of retirement preparedness. Variable with values 1–4, 1=not at all prepared, 2=a little prepared, 3=somewhat prepared, 4=very prepared. |

| Financial Literacy Scale (FLS) | Constructed | We constructed the FLS as the mean of all FLS items. FLS item scored as 0 for incorrect and do not know and 100 for correct answers. Please refer to HRS webpage for routing document for survey questions: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/meta/2020/core/qnaire/online/Module1_Retirement_2020B-A.pdf |

| Financial literacy: Inflation (FLS_1) | RV111 | Financial literacy question about the concept of inflation (balance in a savings account with X interest rate and X inflation rate). |

| Financial literacy: Interest rate (FLS_2) | RV112 | Financial literacy question about the concept of compound interest rate (balance in a savings account after X years of). |

| Financial literacy: Risk (FLS_3) | RV113 | Financial literacy question about the concept of risk (buying single company stock versus stock mutual fund). |

Table A3.

Summary Statistics for all variables in analysis for 2020 HRS Full Sample and Two Subsamples: Not in Experimental Module 1 and in Experimental Module 1

| (1) Full sample |

(2) Not in Experimental Module1 |

(3) In Experimental Module 1 |

(4) Difference (2) - (3) |

(5) Difference (2) - (3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | b | P-value | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.81 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.42 |

| Hispanic | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.55 |

| Female | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.01 | 0.54 |

| Couple Household | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| Spanish survey | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| US born | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.85 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| Age | 67.99 | 68.05 | 67.34 | 0.71 | 0.02 |

| Nursing home | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.85 |

| High school graduate | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.85 |

| Some college | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.75 |

| College grad and above | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Working status | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.37 | −0.01 | 0.44 |

| Retired Status (Survey) | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.78 |

| Household income | 78.03 | 78.31 | 74.67 | 3.65 | 0.34 |

| Receives social security | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.79 |

| Prob. leave bequest $10,000 | 64.46 | 64.39 | 64.76 | −0.37 | 0.74 |

| IRA/Keogh Acct. Balance | 192172 | 201832 | 102346 | 99486 | 0.72 |

| Stocks Acct. Balance | 102949 | 107281 | 64418 | 42863 | 0.29 |

| Checking Acct. Balance | 33004 | 33357 | 29947 | 3410 | 0.24 |

| CD Acct. Balance | 13500 | 14349 | 6135 | 8214 | 0.70 |

| Finc. Plan. Hor. (continuous) | 3.18 | 3.18 | 3.15 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| FP-next few months | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.17 | −0.01 | 0.37 |

| FP-next year | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.95 |

| FP-next few years | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.79 |

| FP-next 5–10 years | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 0.61 |

| FP-greater than 10 years | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.60 |

| (1) Full sample |

(2) Not in Experimental Module1 |

(3) In Experimental Module 1 |

(4) Difference (2) - (3) |

(5) Difference (2) - (3) |

|

| Mean | Mean | Mean | b | P-value | |

| PT. Extrovert | 3.18 | 3.18 | 3.17 | 0.00 | 0.82 |

| PT. Openness | 2.94 | 2.94 | 2.95 | −0.01 | 0.57 |

| PT. Conscientiousness | 3.36 | 3.36 | 3.35 | 0.01 | 0.54 |

| Sat. Health | 3.28 | 3.29 | 3.23 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Sat. Household Income | 3.28 | 3.29 | 3.23 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Sat. Present Finc. Situation | 3.34 | 3.34 | 3.26 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Sat. Life as a Whole | 4.98 | 4.98 | 4.92 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Observations | 15482 | 14108 | 1350 | 15458 |

Footnotes

You can test your knowledge using this scale in the American College Center for Income Retirement website here: https://retirement.theamericancollege.edu/2020-retirement-income-literacy-survey

For more information on the HRS experimental modules, go to the HRS website https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/documentation/modules. You can find the RKS in the HRS https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/meta/2020/core/qnaire/online/Module1_Retirement_2020B-A.pdf.

The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

You can access the questions on financial literacy from Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) in the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center (GFLEC) website: https://gflec.org/education/questions-that-indicate-financial-literacy/

Polychoric correlations not included in Table 3 since all variables are continuous.

Estimation results for models with interactions of the retired status dummy not included for purpose of space, but available upon request.

Full set of coefficients for these regressions are available upon request.

References

- Anantanasuwong K (2023). Improving retirement savings by alleviating behavioral biases with financial literacy. The Journal of Retirement, Jor.2023.1.140, 140. 10.3905/jor.2023.1.140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angrisani M, & Casanova M (2021). What you think you know can hurt you: Under/over confidence in financial knowledge and preparedness for retirement. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 20(4), 516–531. doi: 10.1017/S1474747219000131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, & Bonett DG (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. 10.1037//0033-2909.88.3.588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco Luisa., Garcia C, and Gutierrez R (2022). Systematic Review of Racial, Ethnic and Gender Differences on Financial Knowledge in the United States. Pepperdine University, School of Public Policy Working Papers. Paper 80. Available online (Accessed November 23, 2022) https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/sppworkingpapers/80 and https://ssrn.com/abstract=4145999 [Google Scholar]

- Blanco L, Duru O, & Mangione C (2019). A community-based randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention to promote retirement saving among Hispanics. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, (2019). doi: 10.1007/s10834-019-09657-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco L, Aguila E, Gongora A, Duru KO (2017). Retirement Planning among Hispanics: In God’s Hands? Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 29(4), 311–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher-Koenen T & Lusardi AM (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10(4), 565–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SP, & Skimmyhorn W (2018). Can information change personal retirement savings? evidence from social security benefits statement mailings. American Economic Review, 108, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carr NA, Sages RA, Fernatt FR, Nabeshima GG, & Grable JE (2015). Health Information Search and Retirement Planning. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 26(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Financial Preparedness. (2022). 2019 Retirement Preparedness Survey. Available online (Accessed on November 9, 2022): https://www.cfp.net/knowledge/reports-and-statistics/consumer-surveys/2019-retirement-preparedness-survey

- Clark RL, Mitchell OS. (2022). Factors influencing the choice of pension distribution at retirement. NBER; Working Paper 30115. [Google Scholar]

- Clark RL, Morrill MS, Allen SG (2012). The role of financial literacy in determining retirement plans. Economic Inquiry, 50, 4: 851–866. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Reserve. (2023). Report on the Economic Well-being of U.S. Households in 2022. Available online (accessed June 2023): https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2022-report-economic-well-being-us-households-202305.pdf

- Flesch R (1948). A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology. 32(3), 221–233. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustman A & Steinmeier T (2001). Imperfect knowledge, retirement and saving. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 8406. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Retirement Study (2020). HRS Early Core public use dataset. Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740). Ann Arbor, MI. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins J & Littell D (2016). Retirement Income Planning Literacy in America : A Method for Determining Retirement Knowledgeable Clients. Journal of Financial Planning, 28(10), 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Houts CR, & Knoll MA (2020). The financial knowledge scale: new analyses, findings, and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(2), 775–800. 10.1111/joca.12288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs-Lawson JM, & Hershey DA (2005). Influence of future time perspective, financial knowledge, and financial risk tolerance on retirement saving behaviors. Financial Services Review, 14(4), 331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Joo SH, & Grable JE (2005). Employee education and the likelihood of having a retirement savings program. Journal of Financial Counseling & Planning, 16(1), 37. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KK,. & Xiao JJ (2020). Racial/ethnic differences in consumer financial capability: The role of financial education. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(1), 379–395. 10.1111/ijcs.1262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KT, Lee J, & Lee JM (2019). Exploring racial/ethnic disparities in the use of alternative financial services: the moderating role of financial knowledge. Race and Social Problems, 11(2), 149–160. 10.1007/s12552-019-09259-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll MA & Houts CR. (2012). The financial knowledge scale: an application of item response theory to the assessment of financial literacy. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 46(3), 381–410. [Google Scholar]

- Lown JM, Development and Validation of a Financial Self-Efficacy Scale (2011). Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(2), 54. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A (2003). Planning and saving for retirement. Dartmouth College, Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A (2005). Financial Education and the Saving Behavior of African-American and Hispanic Households. Department of Economics at Dartmouth College, Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, & Mitchell O (2011a). Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 17078. [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A, & Mitchell O (2011b). Financial literacy and retirement planning in the united states. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10(4), 509–525. 10.1017/S147474721100045X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusardi A (2019). Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 155(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, & Sugawara HM (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell OS, & Lusardi A (2015). Financial literacy and economic outcomes: evidence and policy implications. The Journal of Retirement, 3(1), 107–114. 10.3905/jor.2015.3.1.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell OS, & Lusardi A (2023). Financial literacy and financial behavior at older ages. In The Routledge Handbook of the Economics of Ageing. Eds. Mitchell O and Lusardi A Routeledge, London. 10.4324/9781003150398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]