Abstract

In the present work, we carried out a comparative study of the attenuation coefficient of the white matter of the rat brain during the growth of glial tumors characterized by different degrees of malignancy (glioblastoma 101/8, astrocytoma 10-17-2, glioma C6) and during irradiation. We demonstrated that some tumor models cause a pronounced decrease in white matter attenuation coefficient values due to infiltration of tumor cells, myelinated fiber destruction, and edema. In contrast, other tumors cause compression of the myelinated fibers of the corpus callosum without their ruptures and prominent invasion of tumor cells, which preserved the attenuation coefficient values changeless. In addition, for the first time, the possibility of using the attenuation coefficient to detect late radiation-induced changes in white matter characterized by focal development of edema, disruption of the integrity of myelinated fibers, and a decrease in the amount of oligodendrocytes and differentiation of these areas from tumor tissue and healthy white matter has been demonstrated. The results indicate the promise of using the attenuation coefficient estimated from OCT data for in vivo assessment of the degree of destruction of peritumoral white matter or its compression, which makes this method useful not only in primary resections but also in repeated surgical interventions for recurrent tumors.

1. Introduction

Gliomas are the most common brain tumors, where glioblastoma, being the most aggressive brain tumor, accounts for 48.3% of all primary malignant brain neoplasms [1]. The main feature of gliomas is infiltrative growth into the surrounding brain tissue. Therefore, despite aggressive treatment tactics, including maximum possible tumor removal, radiation and chemotherapy, the median survival rate for glioblastoma does not exceed two years [2].

The main stage of combined treatment of gliomas is surgery, which is performed to remove the tumorous tissue as much as possible while maintaining the patient's high functional status [3]. However, it is necessary to understand that to achieve high-quality tumor resection, it is important to remove not only the tumorous tissue, but also the tissue inside the peritumoral zone, with altered structural and metabolic features, containing tumor cells. Incomplete removal of damaged areas may lead to early tumor recurrence.

After surgical treatment, in order to destroy residual tumor cells remaining in the tumor bed, radiation therapy is used, in particular, X-rays, gamma radiation, proton therapy [4]. Unfortunately, although the use of radiotherapy has increased the life expectancy of patients with gliomas, tumor recurrence occurs in nearly all patients with glioblastoma at various time points after irradiation, requiring repeated surgery [5].

It should be noted that the search for the resection margin of gliomas during repeated resection becomes significantly more complicated, which is associated with the development of radiation-induced changes in nerve tissues located in close proximity to the tumor tissue. This fact is explained by the fact that the adjacent nerve tissues are also exposed to ionizing radiation in order to increase the effectiveness of treatment. In particular, if high-grade gliomas are concerned, treatment guidelines indicate the need to include both the tumor bed and 1.5–2 cm of surrounding tissues in the volume of irradiated tissues in order to kill the remaining tumor cells [6]. Radiation-induced changes differ depending on the time elapsed after irradiation and are classically divided into acute, early-delayed and late stage [7]. Therefore, during repeated surgery, neurosurgeons face the necessity to distinguish the following tissue types: 1) tumorous tissue, 2) damaged nervous tissue infiltrated by tumor cells, 3) radiation-induced changes arising at different time points after irradiation, 4) normal brain tissue.

Gliomas often develop in close proximity to white matter pathways, leading to their destruction and the development of functional deficits in patients [8]. Currently, the main method of in vivo diagnosis of the state of the white matter tracts in cases of primary and recurrent gliomas is diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging (DT-MRI). This technology allows obtaining information about the relative position of the tumor and the pathways, as well as characterizing the orientation and degree of preservation of the tracts based on qualitative and quantitative processing of MRI images [9]. DT-MRI examination is carried out at the preoperative stage and allows neurosurgeons to plan surgical intervention. At the intraoperative stage, DT-MRI images may be loaded into a neuronavigation station, which allows neurosurgeons to perform spatial orientation in the surgical field [10]. However, the “brain shift” phenomenon occurring after opening the dura mater is often observed leading to a possible discrepancy between MRI images and the real position of the structures [11]. To clarify the tumor tissue in situ, some intraoperative imaging technologies (tumor fluorescence and ultrasound) are used, but they are aimed exclusively at detecting tumor tissue and are not specialized for identifying weakly infiltrated or damaged white matter [12,13]. Considering all of the above, the issue of searching for new diagnostic methods that will allow intraoperative determination of the morphological status of white matter in the peritumoral zone remains relevant.

Recently, optical diagnostic methods have been actively developing, among which optical coherence tomography (OCT) can be pointed out. This method allows one to obtain high-resolution images of the internal structure of tissue to a depth of up to 1.5 mm [14]. Currently, OCT occupies a leading position among all optical diagnostic methods being introduced into clinical medicine, due to its non-invasiveness, the absence of the need for additional contrast agents, the absence of a damaging effect on tissue, and the possibility of objectifying the obtained data by quantifying key parameters of the OCT signal, such as the attenuation coefficient.

Over the past decades, the possibility of using OCT in neurosurgery to find the resection margin of malignant neoplasms, especially when they are located next to white matter tissue, has been actively studied. For this purpose, the attenuation coefficient is most frequently used, which is the most common parameter for quantitative processing of OCT data. A number of papers have shown that the use attenuation coefficient estimation from OCT data makes it possible to differentiate normal and tumor brain tissues with high diagnostic accuracy [15–17]. Our research group has previously demonstrated that attenuation coefficient allows detecting areas of damaged white matter in the peritumoral zone of gliomas and to distinguish these areas from intact white matter and tumor in patients [18].

Currently, a number of algorithms are known for calculating the attenuation coefficient, among which the log-and-linear fit approach and depth-resolved approach are the most widely used in biomedical research [19]. The use of both approaches allows detecting differences between pathological and normal brain tissues. For example, in the paper by Kut et al., usage of log-and-linear fit approach make it possible to distinguish between normal white matter and tumorous tissue with excellent sensitivity (92-100%) and specificity (80-100%) [15]. The use of the depth-resolved algorithm for the analysis of OCT images of brain tissue allows us to obtain more contrasting optical maps, in comparison with the log-and-linear fit approach, which was shown in our previously published work [18]. As a result, in the present work we use this approach to analyze the obtained images.

It is necessary to understand that gliomas are characterized by various degrees of malignancy and different invasiveness into surrounding tissues and, as a result, may lead to various morphological changes in the white matter [20,21]. We assume that different glial tumors will have different effects on the OCT signal pattern and white matter attenuation coefficient values, depending on the type of morphological changes caused. Moreover, as far as repeated surgery is concerned, it is necessary to study the possibilities of using OCT to differentiate areas with various glioma-induced alterations, areas with morphological changes occurring after exposure to ionizing radiation and healthy white matter.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to perform quantitative OCT imaging of white matter of the rat brain in different models of glial tumors and after exposure to ionizing radiation and determine the possibility to use OCT for differentiation of various morphological states of white matter. To investigate the effects of glioma growth on white matter attenuation coefficient values, we selected three tumor models, namely, glioblastoma 101/8, astrocytoma 10-17-2, and glioma C6. These tumors are characterized by different growth rates and degrees of invasion into surrounding tissues, which will be reflected in different morphological changes in the peritumoral white matter. Therefore, we assumed that the growth of these tumors would have different effects on white matter attenuation coefficient values depending on the type of structural changes observed.

2. Materials and methods

The work included 2 independent series of experiments. Both series were aimed at studying changes in white matter under the influence of various factors: the first series - with tumor invasion, the second - with exposure to ionizing radiation. The changes were assessed by calculating the attenuation coefficient using OCT data.

2.1. Intracranial rat glioma models and study design for rats with brain tumors

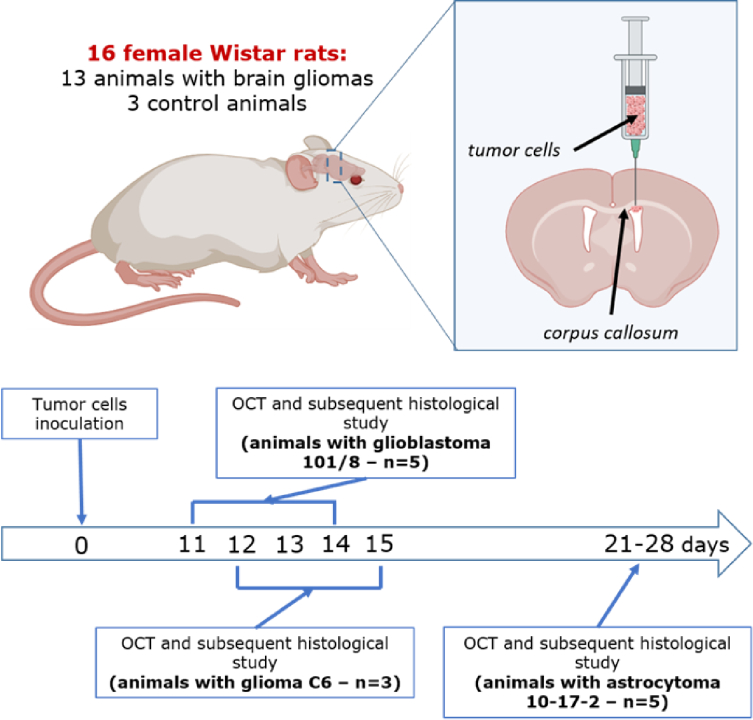

The study was performed on Wistar rats aged 12-16 weeks with orthotopic models of glial tumors. The study included 16 animals, divided into 4 groups: rats with glioblastoma 101/8 (n = 5), rats with astrocytoma 10-17-2 (n = 5), rats with C6 glioma (n = 3), control group of rats without tumor (n = 3). The general design of the experiment included the following steps (Fig. 1): 1) orthotopic injection of glial tumors’ cells; 2) ex vivo OCT study of the brain samples; 3) histological and immunohistochemical (IHC) examination of samples; 4) comparison of OCT and histological data.

Fig. 1.

Study design. The experiment started with the obtainment of orthotopic models of rat gliomas. Tumor cells were inoculated into the right ventricle of the brain with corpus callosum being supposed to be involved into further tumor invasion. As soon as the tumors reached the significant size for OCT study, the animals were euthanized, the brain was removed from the cranial cavity and the fresh frontal sections of the brain were made. Fresh frontal sections were subjected to OCT study and then were forwarded to histological and IHC examinations. Created with biorender.com

The usage of animal models allows standardizing experimental conditions and gives the possibility to select tumors with the necessary characteristics. The used glial tumor models differed in the degree of malignancy, growth rate, and the degree of growth invasiveness into surrounding tissues, and, accordingly, had different effects on surrounding tissues.

Glioblastoma 101/8 was initially obtained in 1967 by an injection of 7,12-dimethyl-(a)-benzanthracene into the right hemisphere of the cerebellum of a female Wistar rat and maintained by continuous intracerebral passages [22]. The tumor shows the typical histological picture of aggressive glioblastoma characterized by fast infiltrative growth into surrounding tissues. C6 glioma was also obtained in the early 1970s as a result of serial intravenous administration of N-Nitroso-N-methylurea to Wistar rats. Intracerebral injection of a cell culture of this tumor quite quickly leads to the formation of a tumor node, with a high tendency to form the necrotic foci and hemorrhages. C6 glioma is characterized by high malignancy, but slightly invades normal brain tissue, which distinguishes it from the experimental model of glioblastoma 101/8 [23]. Glioma model 10-17-2 shows the histological features of an anaplastic astrocytoma. This type of tumor has less pronounced mitotic activity compared to the glioblastoma 101/8, and is also not prone to the formation of necrosis and hemorrhages within the tumor mass. Astrocytoma 10-17-2 is characterized by lower malignancy in comparison with models 101/8 and C6, which is reflected in the lower growth rate of the tumor node and insignificant infiltration of surrounding tissues by tumor cells [24].

Glioblastoma 101/8 and astrocytoma 10-17-2 were produced by an injection of homogenized tumorous tissue obtained from donor rats (∼106 tumor cells in 10 µL PBS) into the brain as described by Khalansky et al. [25]. To produce C6 glioma, C6 rat glioma cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS in CO2 incubator (5% CO2, 37°C, humidified atmosphere). Cells were trypsinized (0.25% trypsin) for 3 min, washed and re-suspended in DMEM to the concentration 5 × 108 cells/mL.

For tumor cells injection animals were anesthetized with zoletil (12.5 mg/kg) and xylazine (1 mg/kg), immobilized on a stereotaxic unit. The indicated amount of cells was inoculated into the ventricle of right hemisphere of the brain at ∼4 mm depth via the hole drilled in the scull 2 mm lateral and 2 mm posterior to the bregma. The animals were maintained in a temperature-, humidity-, and light-controlled room, with free access to water and food. We controlled the rats’ weight and behavior as indicators of tumor growth and invasion, i.e. visual criteria for tumor growth were: 1) a noticeable decrease in the animal’s weight (over 10% of body weight); 2) decreased physical activity; 3) behavioral disorders (lethargy, apathy).

As soon as the above signs were observed, this served as an indicator that the tumor had reached a sufficient size to conduct an OCT examination. The euthanasia of animals was performed via decapitation and the brain was extracted from the cranial cavity. The euthanasia of animals followed by OCT study of the fresh brain samples was carried out on days 11-14 after injection of tumor cell culture in the group with glioblastoma 101/8, on days 21-28 in the group with astrocytoma 10-17-2, and on days 12-15 in the group with C6 glioma.

This study adheres to all relevant international, national, and institutional guidelines for animal care and use and was approved by Institutional Review Board of Privolzhsky Research Medical University.

2.2. Study design for rat brain irradiation

Brain irradiation procedure was carried out on Wistar rats aged 12-16 weeks (n = 6) as was described in detail in our previous work [26]. Healthy (tumor-free) animals were chosen as research objects, since human patients arrive at the irradiation procedure at a time when tumor tissue is absent (after surgical removal). Animals were anesthetized with medetomidine 0.4 mg/kg and then underwent focal X-Ray irradiation (200 kV, 17 mA, 0.3 mm Cu filtration) of the right hemisphere of the brain: 15 Gy at a dose rate 0.7 Gy/min. Irradiation was performed using MultiRad225 X-Ray system (Precision X-Ray, USA). The boundaries of the focal spot size (1.3 ∼ 1.7 cm2) were: in front—binocular connection of the inner canthus of the eye; laterally—the external opening of the auditory canal; inside—sagittal suture. 15 Gy represents a biologic equivalent dose of 63.75 Gy in 2 Gy fractions which is consistent with irradiation doses commonly used for brain tumors (60 Gy in 2 Gy fractions), assuming an α/β of ∼2 Gy for brain tissue [27]. To minimize irradiation of the other parts of the body, rats were covered with a lead apron (0.5 mm Pb).

At 6 months after irradiation animals were euthanized, the brain was extracted from the cranial cavity and fresh frontal sections of the brain were forwarded to OCT study. The timing of euthanasia of animals was dictated by the need to register the occurrence of late changes in the white matter, since in patients most often repeated resections are carried out six months or more after the initial surgical intervention [28].

2.3. OCT device and OCT data processing

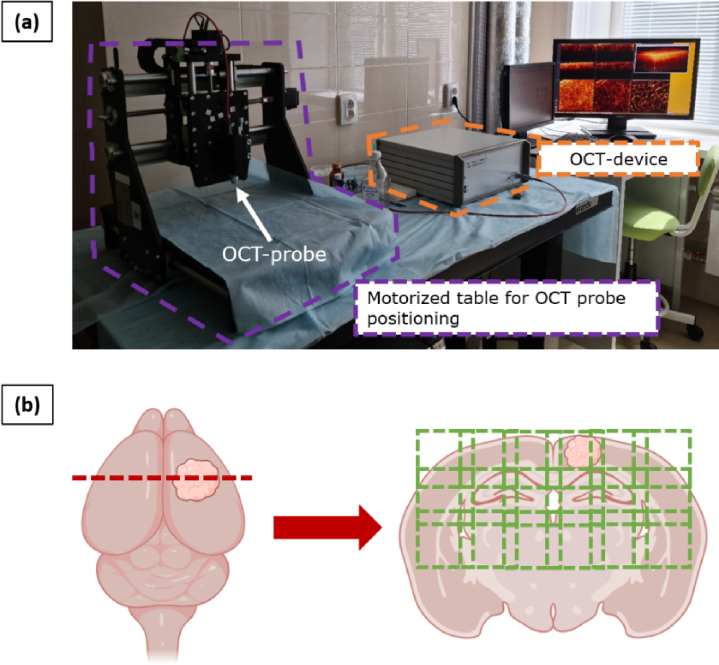

The study was performed with spectral-domain multimodal OCT device (Institute of Applied Physics of Russian Academy of Sciences, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia) (Fig. 2(a)). The utilized system has a common-path interferometric layout operating on 1310 nm central wavelength. The axial resolution is 10 µm and transverse resolution is 15 µm in air. The device has a 20000 A-scans/s scanning rate and performs 3D scanning of 2.4 × 2.4 × 1.25 mm3 with the simultaneous building of 2D OCT images in three different planes: along the scanning plane, perpendicular to the scanning plane and en-face images (top view - 256 × 256 A-scans).

Fig. 2.

OCT device used in the study (a) and the preparation frontal sections of the brain with indicated direction of OCT study (b). For brains with tumor models, the sections were made through the center of the tumorous node and for irradiated brains, sections were made on the level of anterior commissure or internal capsule.

OCT study was carried out immediately after animal decapitation and brain extraction from the cranial cavity. Fresh frontal brain sections were made through the center of the tumorous node in case of brains with tumor models and on the level of anterior commissure or internal capsule for irradiated brains and put under the OCT probe with the following scanning of the full section surface. Three-dimensional OCT images were acquired in contactless mode in several stripes with a step of 2 mm to ensure overlap between adjacent OCT images for ease of subsequent image stitching (Fig. 2(b)).

The obtained 3D OCT images were quantitatively analyzed – converted into 2D en-face color-coded images of the attenuation coefficient distribution. Attenuation coefficient (µ) was calculated in each A-scan in the depth range 120-300 µm to get the highest contrast color-coded maps and providing the best information about the morphology of brain tissue, which was shown in our previous study [29]. For data processing depth-resolved approach, described in detail in [30] was used. This approach was initially proposed in [31] and follows the assumption that the backscattering coefficient is proportional to the attenuation coefficient and the ratio between the coefficients is constant in the OCT image depth range:

| (1) |

where Ii is the sum of OCT signal intensities in both polarization channels, µ att is the specimen attenuation coefficient, z i is the depth coordinate, Δ is the pixel size along the axial dimension.

The used modification allows avoiding systemic µ estimation bias, characteristic for original approach [31] since it accounts for the noise with the non-zero mean, present in the distributions of the measured absolute values of the OCT images. In [30] it was shown, that the depth-resolved attenuation coefficient can be written as:

| (2) |

where μi is the underlying distribution of the attenuation coefficient at depth i, μexpi is the distribution at depth i, estimated according to [31], Hi is the multiplier, dependent on the cumulative noise and cumulative signal at depth i, Nµi is the additive term, which could be treated as noise. In particular, according to [31]:

| (3) |

where Ii is the OCT signal intensity, imax is the index of the maximal depth in the OCT image, Δ is the pixel size.

As was shown in [30]:

| (4) |

where < N > is the amplitude of the noise floor, which can be estimated before the measurements.

Representation (2) allows one to estimate the underlying attenuation coefficient distribution as follows:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where SNRiµ is the local signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for the attenuation coefficient distribution, which is estimated by the averaging in the rectangular window with the side of W pixels. The W value should be sufficiently large (≥32 pixels) to provide sufficient statistics inside each window. The value (Ij + Nj) is simply the measured signal at the depth j. Thus, all the values from Eq. (2) can be measured from the cross-sectional OCT intensity distributions.

One should note that the estimation (3) does not take into account the additive noise, which can lead to significant distortions of the underlying distributions [30], especially at the bigger depths. The effect of the ignoring the noise is two-fold: when the signal is non-zero, µexp underestimates the attenuation coefficient, since the noise of the absolute value of the signal makes the denominator in (3) bigger than it should be. When the signal is zero, the presence of the noise makes the estimate non-zero and it tends to grow with the depth, since the range of the summation of the denominator in (3) is limited by the maximal depth and the value of the denominator decreases with the time. The multiplier in (5) accounts for both of these effects and makes the attenuation coefficient distributions closer to the underlying value in the areas with the high SNR and suppresses it to zero in the areas with low SNR to avoid misinterpretations. One should also note, that the depth-dependent sensitivity of the OCT system was not taken into account in this study, which, according to [30], could be done for the OCT system with a lateral resolution equal to the one used in the study.

Overall, the attenuation coefficient estimation algorithm could be summarized as follows:

-

1.

The distribution of the absolute values of the OCT signal was convolved with 3 × 3 × 3 pixel window to reduce the speckle noise.

-

2.

The distribution µexp was estimated according to Eq. (3).

-

3.

<N > was estimated from the bottom part of the OCT image, where the OCT signal was expected to be 0.

-

4.

Hi, Nµi and SNR i µ values were estimated according to Eqs. (4) and (6) respectively.

-

5.

Estimation of the attenuation coefficient µest was calculated according to the Eq. (5).

The obtained distribution of µ values allowed us to build en-face maps as a rainbow colormap for each OCT image, where orange and red colors represent the areas with high µ values, blue represents low µ values and azure, green and yellow – intermediate ones, respectively. Based on the range of the numerical values of µ, a universal color scale was selected, which allows differentiating brain tissues in the specified color range. As it was previously mentioned, the size of obtained OCT image and, accordingly, en-face color coded map, is 2.4 × 2.4 mm2. Thus, several areas of the rat brain are visualized in one color-coded map. Therefore, we were not able to use the median µ value throughout the entire size of OCT image, since it will be obtained from different types of brain tissue. Therefore, we calculated the median values of µ for the selected region of interest (ROI) to obtain µ values distribution for different tissue types.

Since tumor cells were inoculated into the right ventricle located at a close proximity to corpus callosum, this area was selected as ROI to evaluate the influence of different glioma models and irradiation on the white matter. The calculation of the attenuation coefficient values in the ROI was carried out in strict comparison with the corresponding histological sections.

2.4. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

After OCT imaging, all of the samples were forwarded to histological study. The samples were fixed in 10% formalin for 48 hours and then the series of 4 µm thick histological sections was made. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for obtaining the general information about the sample, i.e. the location of the tumor node and involvement of surrounding structures in tumor growth. The precise study of the white matter morphological features was performed on immunohistochemical (IHC) sections stained using antibodies to myelin basic protein (MBP) (Abcam, USA). The following characteristics were analyzed: 1) packing and degree of preservation of myelinated fibers; 2) the presence and severity of edema; 3) the presence of tumor and/or glial cells.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. To evaluate the results of quantitative image processing, we used the median value among all values of µ calculated for each A-scan in the selected ROI. The total amount of A-scans included in the statistical analysis for each studied group was: 61236 for animals with glioblastoma 101/8, 56234 for animals with astrocytoma 10-17-2, 36046 for animals with C6 glioma, 78688 for irradiated animals and 40524 for animals from the control group. The results are expressed as Me [Q1;Q3], where Me – is the median value of optical coefficient; Q1, Q3 – are the values of 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. To compare optical coefficient values of different tissue types, we used the Mann-Whitney U-test with the hypothesis that there was no difference between the compared groups. To counteract the multiple comparisons problem we used the Bonferroni correction. The differences were considered statistically significant with p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of healthy rats’ brains

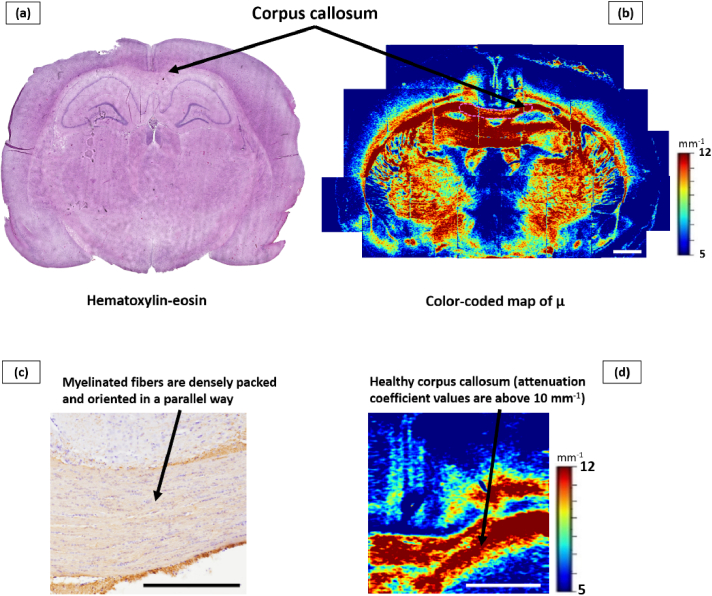

The first stage of the work included the analysis of morphological and scattering properties of white matter in healthy (without tumors and irradiation) rats’ brains. According to histological examination, corpus callosum is characterized by the presence of densely packed myelinated nerve fibers, oriented in a parallel way, and separated by small interspaces.

The numerical analysis of OCT images revealed that the healthy corpus callosum is characterized by high attenuation coefficient values (µ = 11.7 [10.8; 13.5] mm−1), demonstrating high scattering properties. On color-coded maps, healthy corpus callosum is represented by red, orange, and yellow and is clearly visually distinguishable from blue and dark-blue gray matter areas (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Frontal section of the brain of a rat from the control group. An overview histological section stained with hematoxylin-eosin (a) and an overview color-coded map of the attenuation coefficient µ (b) are presented, where the location of selected region of interest is demonstrated. An enlarged IHC image of the area of the corpus callosum, where ordered, densely located myelin fibers are visualized (c). A color-coded map of µ where the area of healthy callosum is indicated, characterized by high values of the attenuation coefficient (d). Scale bar is 1 mm on the color-coded map and 500 µm on the IHC image.

Please note that in Fig. 3 and subsequent figures, the optical maps and histological images may be presented at different scales. The different scales were chosen due to the need to show the differences between the damaged and healthy tissues on the color-coded maps and at the same time clearly demonstrate the morphological changes that we observe in the damaged areas. Otherwise, the optical maps or histological images would have been completely unrepresentative for readers.

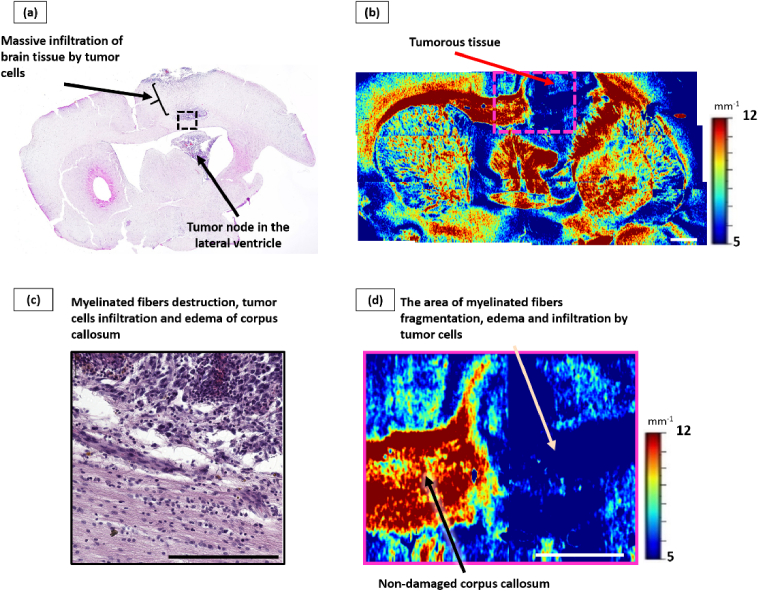

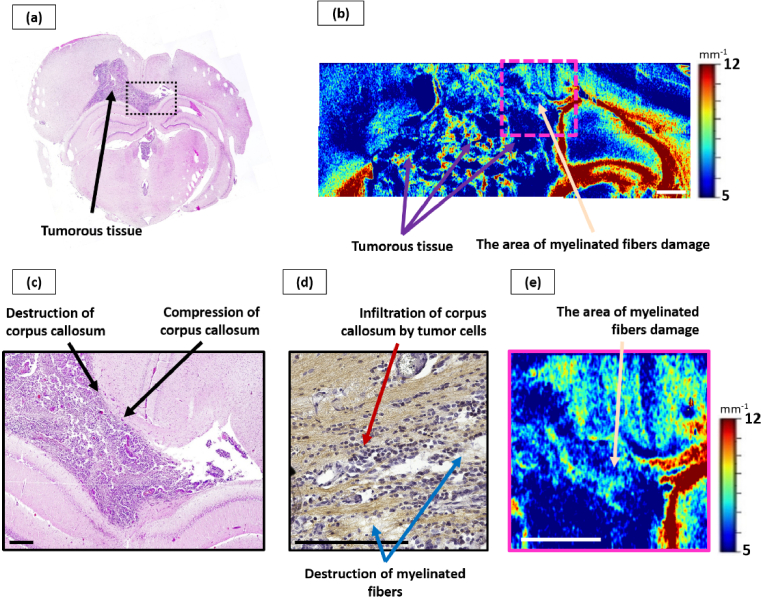

3.2. Effect of glioblastoma 101/8 growth on the corpus callosum

Histological analysis has revealed that glioblastoma 101/8 was located in the areas of grey and white matter of the right hemisphere in all studied cases. In particular, massive invasion of the tumor alongside the white matter tracts of the corpus callosum was observed with subsequent growth of the secondary tumorous nodes in the lateral ventricles (Fig. 4(a)).

Fig. 4.

Influence of glioblastoma 101/8 growth on the corpus callosum. Overview histological section, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (a), with enlarged area of tumor invasion into corpus callosum, which shows areas of significant infiltration by tumor cells (c). Corresponding color-coded maps of µ: b – general view, d – enlarged area from (b), where non-damaged (black arrow) and damaged (beige arrow) white matter areas are seen. Scale bar: 1 mm on color-coded map, 200 µm on histological image.

The significant reduce of backscattering of the corpus callosum arising from the invasive tumor growth was detected by visual analysis of attenuation coefficient color-coded maps. It was reflected in the statistically significant decrease of µ values in this region (µ = 6.1 [5.2; 6.8] mm−1) in comparison with the control group (µ = 11.7 [10.8; 13.5] mm−1, р<0.0001). At the same time, these areas are characterized by a predominance of blue color on optical maps, which does not allow visually distinguishing them from tumor tissue (µ = 3.7 [3.5; 4.2] mm−1) (Fig. 4(b), (d), (beige arrow)).

Morphologically, glioblastoma 101/8 was the most aggressive tumor among the studied models, characterized by prominent infiltration into the white matter tissue. A targeted examination of the corpus callosum revealed moderate swelling, destruction of myelinated fibers, as well as significant infiltration of tumor cells along the fibers with expansion of the spaces between the fibers (Fig. 4(c)).

Thus, it can be concluded that such a significant decrease in the µ values in the white matter region during the glioblastoma 101/8 growth is associated primarily with two processes. On the one hand, there is destruction of myelinated fibers, which are the main scattering elements of the tissue. On the other hand, the attenuation coefficient values are also affected by the development of edema, since an increase in water in the tissues leads to an increase in the absorption of probing radiation.

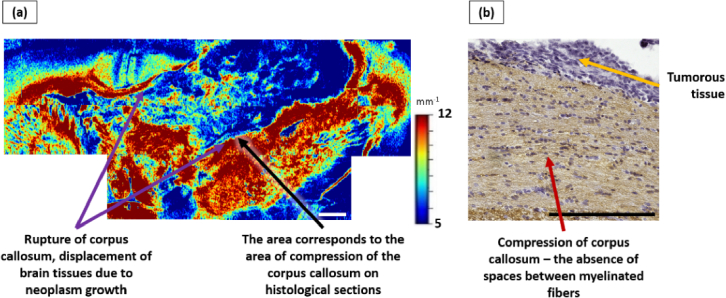

3.3. Effect of astrocytoma 10-17-2 growth on the corpus callosum

Anaplastic astrocytoma 10-17-2 invaded a large area of gray and white matter of one hemisphere in all studied cases. In two out of five cases, the occurrence of foci of necrosis in tumor nodes was observed. In one case, numerous hemorrhages into the tumor tissue were noted.

Analysis of en-face color-coded µ maps revealed a statistically significant decrease in the values of the attenuation coefficient of the corpus callosum in 4 out of 5 cases (µ = 7.1 [6.0; 7.7] mm−1) compared to the control group (µ = 11.7 [10, 8; 13.5] mm−1, p < 0.0001). At the same time, these areas are displayed in blue and azure colors (Fig. 5(b)), therefore it becomes impossible to distinguish these areas from the tumor tissue (µ = 5.8 [5.1; 6.9] mm−1). It should be noted that, in contrast to glioblastoma 101/8, in the region of tumor 10-17-2 there were areas with higher µ values, displayed in green-yellow colors, which corresponded to foci of necrosis.

Fig. 5.

Influence of anaplastic astrocytoma 10-17-2 growth on the corpus callosum (example 1). Overview histological section, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (a), with enlarged area, which visualizes a tumor node that has caused destruction and compression of the myelinated fibers of the corpus callosum (c). Overview color-coded map of µ, where tumorous tissue is visualized (b) with enlarged zone indicating the area of myelinated fibers destruction (e). Destruction of the myelin fibers of the corpus callosum leads to a decrease in the attenuation coefficient values, making it impossible to visually differentiate the altered areas of the corpus callosum from tumor tissue. An enlarged IHC image (MBP) obtained from the same section of the rat brain shows infiltration of the corpus callosum by tumor cells and destruction of myelinated fibers (d). Scale bar is 1 mm on color-coded maps and 200 µm on histological images.

In one case, displacement and compression of the corpus callosum due to tumor growth was detected, while non-significant increase in the values of the attenuation coefficient of this area was recorded, while this area is displayed in dark red color (Fig. 6(a)).

Fig. 6.

Influence of anaplastic astrocytoma 10-17-2 growth on the corpus callosum (example 2). a – color-coded map of µ, which shows the tumor node that caused a total rupture of the corpus callosum; however, in the area corresponding to the zone of compression of the corpus callosum, no decrease in µ values is detected. b – IHC image of corresponding brain section showing an enlarged area of the displaced corpus callosum due to tumor growth, where compression of myelinated fibers is observed. Scale bar is 1 mm on the color-coded map and 200 µm on the histological image.

According to the results of histological examination, significant morphological changes in the corpus callosum, caused by the tumor growth, were found in all studied sections: destruction and rupture of myelinated fibers, its infiltration with tumor cells along with the presence of varying degrees of swelling (from moderate to significant) (Fig. 5(c), (d); Fig. 6(b)). In four out of five cases, severe destruction and rupture of myelinated fibers was observed, especially in areas adjacent to the tumor node. In one case, a total rupture of the corpus callosum was discovered with compression of myelinated fibers in the areas corresponding to the zones with no decrease in µ values on color-coded maps (Fig. 6(a)).

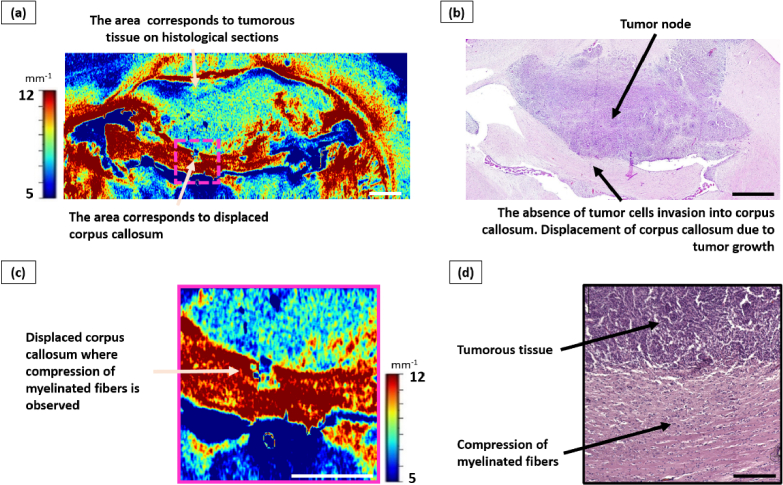

3.4. Effect of glioma C6 growth on the corpus callosum

In all studied cases, the tumor node was located under the meninges in the right hemisphere spreading to the left one. At the same time, it occupied the area of the gray matter of the cortex and bordered the tracts of the white matter of the corpus callosum. There were no necrosis foci or hemorrhages inside the tumor. In addition, this tumor type was found to have little or no invasion of white matter tissue, which distinguished it from models 10-17-2 and 101/8. Thus, the growth of a C6 tumor predominantly causes displacement of brain structures.

During the analysis of the color-coded maps, it was found that the development of C6 glioma does not have a significant impact on the white matter attenuation coefficient values. In all cases, the optical maps showed a displaced corpus callosum, which was characterized by high values of the attenuation coefficient (µ = 11.8 [11.0; 13.7] mm−1) (Fig. 7(a), (c)).

Fig. 7.

Influence of glioma C6 growth on the corpus callosum. a – color-coded map of µ, where a displacement of the corpus callosum region is observed, but the values of the attenuation coefficient are at a high level; b – corresponding histological section, stained with hematoxylin-eosin, where a tumor node is visualized, located in the gray matter and adjacent to the white matter tracts of the corpus callosum. There was no infiltration of tumor cells into the corpus callosum, but this structure is highly displaced due to tumor growth. Scale bar – 1 mm on the color-coded map and overview histological image and 200 µm on the enlarged histological image.

Histological analysis revealed a significant displacement of the corpus callosum due to the growth of the tumor node in all cases (Fig. 7(b), (d)), resulting in compression of myelinated fibers with a decrease in the space between them. In addition, due to compression of the corpus callosum, a higher amount of glial cells fell into the field of view. Infiltration by tumor cells was either insignificant or completely absent.

Thus, in the first series of experiments we demonstrated that, depending on the aggressiveness and growth rate of the tumor, the effect on white matter tissue may vary from compression of myelinated fibers, when µ values may even increase (µ = 11.8 [11.0; 13.7] mm−1) compared to the control group (µ = 11.7 [10.8; 13.5] mm−1), to myelinated fibers destruction accompanied with edema and infiltration of tumor cells, when µ values are significantly reduced (p < 0.0001).

A pronounced decrease in the µ values during invasive tumor growth is explained by changes in backscattering, as well as in the absorption of probing radiation. The main scattering element of white matter is the myelinated fiber, especially the myelin sheath [32]. Accordingly, the observed destruction of myelin fibers leads to a decrease in backscatter due to a decrease in the number of scattering elements in the tissue. The development of edema, on the one hand, leads to an increase in the amount of water in the tissues and an increase in the absorption of probing radiation, which was previously shown on the cerebral cortex [33]. On the other hand, edema leads to an increase in the spaces between the remaining myelinated fibers and, consequently, to a decrease in scattering elements in the field of view (leading to a decrease of µ). Infiltration by tumor cells also affects both the absorption of probing radiation and backscattering. An increase in the number of cells in the field of view, on the one hand, leads to an increase in the number of scattering elements (nuclei), on the other hand, to an increase in absorption (water contained in the cytoplasm). In addition, our group has previously shown that myelinated fibers have a greater influence on µ values compared to cells [29].

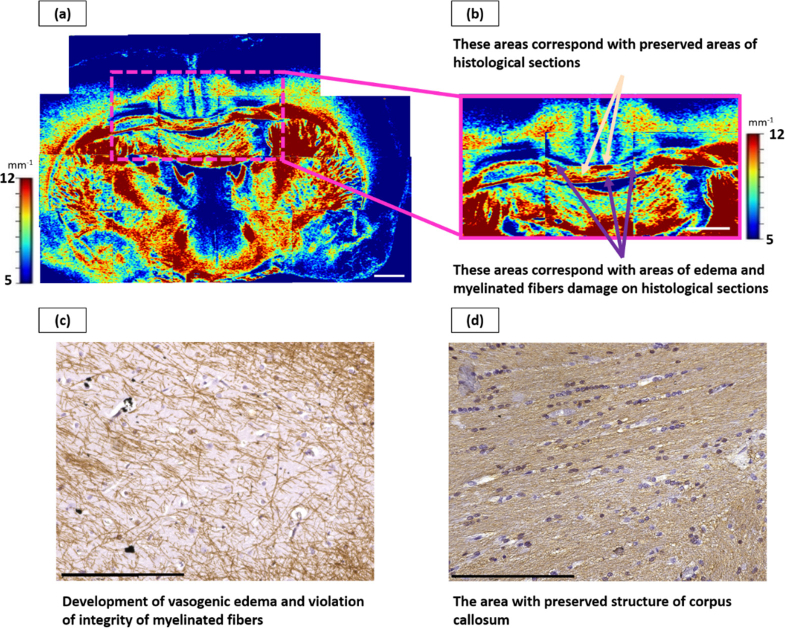

3.5. Effect of irradiation on the corpus callosum

As mentioned above, classically, radiation-induced changes in nervous tissue are divided into three stages depending on the time elapsed after irradiation. Our task in the study was to register late changes that begin to arise six months after irradiation.

The analysis of IHC images revealed morphological changes in the corpus callosum area, characterized by three main features, in 4 out of 6 rats: 1) the development of vasogenic edema of slight or moderate severity; 2) disruption of the integrity of myelinated fibers, reflected in the disappearance of staining with antibodies to MBP; 3) reduced amount of oligodendrocytes (Fig. 8(c)). At the same time, these changes were focal, affecting not the entire area of the corpus callosum, thereby maintaining intact areas with a dense parallel arrangement of myelinated fibers (Fig. 8(d)). In remaining 2 rats we have not discovered any morphological changes. Accordingly, no changes in the numerical values of µ were detected in these cases.

Fig. 8.

Late radiation-induced changes of the corpus callosum. Color-coded maps of µ: a – general view, b – enlarged area from (a), where non-damaged (beige arrows) and damaged (violet arrows) areas of corpus callosum are seen. c and d – corresponding IHC section, demonstrating areas with edema and myelinated fibers damage (c) and preserved area (d). Scale bar: 1 mm on color-coded map, 200 µm on IHC images.

During the analysis of color-coded maps, areas with reduced values of the attenuation coefficient (µ = 9.0 [8.5; 9.4]) compared to normal corpus callosum (p < 0.0001), displayed predominantly in blue (Fig. 8(a), (b), (violet arrows)), were found. These areas corresponded to areas with a violation of the corpus callosum morphology. Areas with high µ values (orange-red) (Fig. 8(a), (b), (beige arrows)) corresponded to areas with dense packing of intact myelinated fibers.

Thus, in this series of experiments, based on quantitative processing of OCT data, we for the first time demonstrated the mosaic nature of radiation-induced changes in white matter that occur six months after exposure to ionizing radiation. The decrease in µ values in this case is associated primarily with two factors, the mechanism of which was discussed above, namely, with the development of edema and disruption of the integrity of myelinated fibers. A decrease in the number of oligodendrocytes presumably had a less significant effect on the µ values in comparison with these factors.

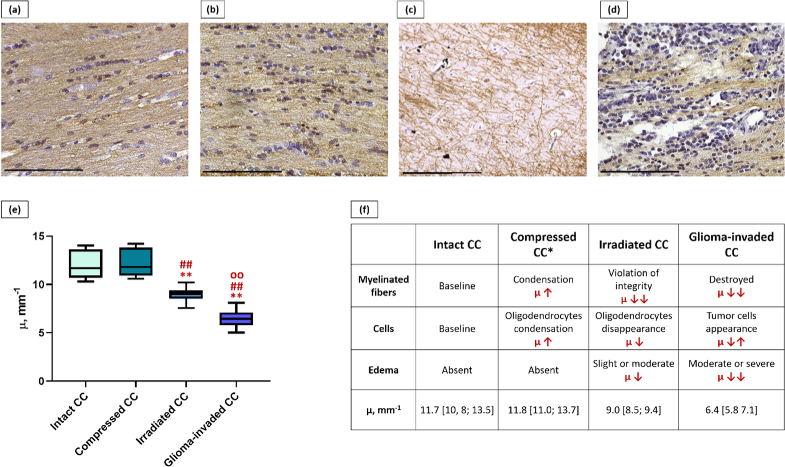

3.6. Comparison of the different morphological states of corpus callosum

To sum up all the obtained data, four morphological states of the corpus callosum were identified: intact (control), compressed, irradiated and glioma-invaded, characterized by different values of µ (Fig. 9). The “compressed corpus callosum” group included all rats with C6 glioma and one rat with 10-17-2 astrocytoma, where a rupture of the corpus callosum was observed. The “irradiated corpus callosum” group included 4 rats after irradiation in which structural changes were observed. The “glioma-invaded corpus callosum” group included 4 rats with astrocytoma 10-17-2 and 5 rats with glioblastoma 101/8.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of different morphological states of corpus callosum (CC). IHC images of intact (a), compressed (b), irradiated (c) and glioma-invaded (d) corpus callosum. Distribution of µ values for studied states of corpus callosum (e): **p < 0.0001 in comparison with intact CC, ##p < 0.0001 in comparison with compressed CC. oop < 0.0001 in comparison with irradiated CC. Components influencing the µ values in studied cases (f). *In case of compressed CC, a higher amount of myelinated fibers and oligodendrocytes appear in the field of view due to displacement of tissue. Scale bar – 200 µm.

The intact corpus callosum is characterized by a dense packing of myelinated fibers, oriented in a parallel way and separated by small interspaces (Fig. 9(a)).

When compression of the corpus callosum arises, which develops as a result of the rapid growth of the tumor node, the spaces between the myelinated fibers disappear. Consequently, more myelinated fibers (main scattering elements) as well as oligodendrocytes forming myelin sheath appear in the field of view (Fig. 9(b)). This leads to a slight increase in µ values in comparison with intact corpus callosum, which is not statistically significant.

In the irradiated (Fig. 9(c)) and glioma-invaded (Fig. 9(d)) corpus callosum, three morphological components influenced the attenuation coefficient. Firstly, in both cases we observed destruction or disruption of the integrity (ruptures) of myelinated fibers - a decrease in the number of main scattering elements. Secondly, the development of edema (which causes the increased absorption) was observed as a universal reaction of white matter to a damaging effect [34]. Moreover, in the case of glioma-invaded corpus callosum, the edema was more pronounced in comparison with the irradiated corpus callosum, which reduced the attenuation coefficient to a greater extent. Third, the number of cells changed, namely, with tumor invasion of the corpus callosum tissue, a large number of tumor cells were found in addition to the glial cells present, while with irradiation the number of oligodendrocytes decreased. In addition, it should be emphasized that after irradiation the changes were focal, while with tumor invasion the changes affected the entire tissue of the corpus callosum. Moreover, in both conditions, the values of µ were statistically significantly different, both from the intact corpus callosum and from the compression state. Additionally, statistically significant differences were found between the irradiated and glioma-invaded corpus callosum, where the white matter being destroyed due to tumor growth characterized by the lowest µ values.

4. Discussion

Optical coherence tomography is a rapidly developing diagnostic technique, being introduced into various fields of medicine from ophthalmology, where OCT has already become the gold standard for diagnosing a number of diseases, to endovascular surgery [14]. Over the past two decades, active research has been carried out on the possibility of using this method to visualize brain tissue, which can be used in neurosurgery [35]. In particular, the work focuses on detecting changes in the properties of nervous tissue during strokes [36] and traumatic injuries [37], imaging of the meninges [38]. However, the most widely studied question is to find differences between tumor and normal brain tissues, which may be used to find the resection margins of malignant brain tumors.

Previously published papers demonstrate the promise of using the OCT method for differentiating between normal white matter and a tumor, for which both visual and quantitative analysis of OCT images based on attenuation coefficient estimation can be used [39–41]. However, more attention should be paid to a targeted study of the peritumoral area, whose characteristics may differ depending on the type of tumor and its features. In addition, the issue of using OCT in case of repeated resections after radiation therapy, where nerve tissue is altered not only due to tumor growth, but also due to irradiation, has not been previously studied.

In the current study, we evaluated the changes of attenuation coefficient values and morphology of brain white matter, caused by infiltrative growth of rat glial tumors of different degree of malignancy and at 6 months after irradiation, and studied the possibility to use OCT for differentiation of morphological changes of white matter caused by to different factors.

Previously, our research group has demonstrated that attenuation coefficient calculation is capable to detect areas of damaged white matter in the peritumoral zone of brain gliomas in patients, without dividing gliomas by degree of malignancy [18]. However, we assume that different glial tumors will have different effects on the white matter attenuation coefficient values, depending on the type of morphological changes caused.

It was found that among the studied tumor models, the most aggressive tumor, causing a significant decrease of attenuation coefficient values of the corpus callosum (µ = 6.1 [5.2; 6.8] mm−1), was glioblastoma 101/8. The development of this tumor was characterized by massive invasion of white matter tissue, causing destruction and rupture of myelinated fibers, as well as edema, making it impossible to visually distinguish damaged areas of white matter from tumor tissue on optical maps. Anaplastic astrocytoma 10-17-2 also caused a sharp decrease in the attenuation coefficient values recorded from the corpus callosum region (µ = 7.1 [6.0; 7.7] mm−1). The decrease of µ in this case is morphologically explained by the formation of the following changes: tissue edema, destruction and rupture of myelinated fibers. Tumor cell infiltration in this case was less than in the case of glioblastoma 101/8 growth. The development of C6 glioma, unlike other models of glial tumors, did not cause a decrease in the attenuation coefficient of the corpus callosum, with the exception of areas where destruction of myelin fibers was observed. This fact is explained by displacement and compression of the corpus callosum due to the growth of the tumor node, detected histologically.

In addition, we for the first time demonstrated that attenuation coefficient estimation may be used to detect late radiation-induced changes arising in white matter 6 months after irradiation and distinguish these areas both from the glioma-induced changes and healthy white matter. Late changes were characterized by focal development of edema, disruption of the integrity of myelinated fibers and a decrease in the number of oligodendrocytes, which was reflected in a statistically significant decrease of µ to 9.0 [8.5; 9.4] in comparison with the control group. In this case, the values of µ were higher than those of the peritumoral white matter, damaged due to infiltrative growth of gliomas. In addition, it should be noted that in previous work [26], by calculating the attenuation coefficient from OCT data, we recorded acute and early-delayed radiation-induced changes in the white matter of the brain, which was also demonstrated on the corpus callosum.

Thus, in the present work we were able to identify four morphological states of the corpus callosum: intact, compressed, irradiated and glioma-invaded, characterized by different values of the attenuation coefficient. The lowest µ values were recorded in cases where changes such as destruction of myelinated fibers, edema (moderate or significant) and infiltration of tumor cells were observed. Such a significant decrease in µ is caused by a pronounced decrease in backscattering with a simultaneous increase in the absorption of probing radiation. In cases where focal changes were observed, including mild to moderate edema, disruption of the integrity of myelinated fibers and a decrease in the number of oligodendrocytes, µ values were lower compared to the control and compressed corpus callosum, but statistically significantly higher compared to glioma-invaded corpus callosum. Isolated compression of the corpus callosum leads to a slight increase in µ compared to the control, which is associated with an increase in the number of scattering elements in the field of view.

Moreover, we can expect that in addition to the above conditions, it is possible to simultaneously detect the isolated edema of the corpus callosum, which is characteristic of the stage of acute and early-delayed radiation-induced changes. Previous work [26] showed the following values of µ for the irradiated corpus callosum: 10.6 [9.0; 12.5] mm−1 for the stage of acute changes (mild edema) and 9.8 [8.8; 11.2] mm−1 for early-delayed changes (moderate edema). If we compare these ranges of µ values with the values obtained for the morphological conditions studied in this work, the corpus callosum, characterized by isolated edema, will occupy a position on the diagram (Fig. 9) between intact/compressed and irradiated corpus callosum.

Thus, all of the aforementioned indicates that OCT, in particular, attenuation coefficient calculation, is a promising tool for finding the resection margin not only during primary tumor removal, but also during repeated resections at various time points, where the surrounding nerve tissue is changed not only due to tumor growth, but also as a result of exposure to ionizing radiation.

A number of limitations of our work should be noted.

Firstly, our study was conducted on ex vivo brain tissue samples, although OCT is marketed primarily as an in vivo technology. The choice of object was due to the following reasons: 1) the need to study the deep structures of the brain (to access the corpus callosum, removal of the cortex is necessary); 2) the need for a detailed description of the location of the tumor and identification of structures involved in tumor growth; 3) the need for a detailed analysis of the entire peritumoral zone (after in vivo studies it would be impossible to obtain high-quality frontal brain sections, as in our work). In addition, it should be noted that during in vivo studies, the nature of the OCT signal could be influenced by the respiration of the animal, which will lead to the formation of artifacts in the images and the impossibility of subsequent processing.

Secondly, OCT studies with an applied focus are carried out mainly on tissue samples obtained from patients. However, it should be noted that glial tumors of patients are heterogeneous even within the same grade. Moreover, as far as repeated resections are concerned, firstly, the amount of such patients is significantly reduced compared to patients undergoing first surgery; secondly, patients are forwarded to repeated resection on different time points after irradiation. Therefore, in order to ensure representative sampling, samples would have to be collected over a long period of time.

Thirdly, it is not completely known what exact changes myelinated fibers undergo both during tumor invasion and post-radiation changes. On IHC images, we observe the disappearance of MBP staining, indicating that there is no myelin in the area of interest. Unfortunately, without electron microscopy we cannot say what exactly we are observing: isolated demyelination or a total disruption of the structure of the fibers (both the sheath and the axon). This issue remains the subject of further research. However, in any case, the normal structure of the fibers is disrupted, which leads to the inability to conduct impulses.

Fourthly, the utilized method of the attenuation coefficient estimation was a model-based method, i.e. method, consistently derived from the model of the OCT signal formation. To our knowledge, the method was not consistently verified on the calibrated samples.

The authors plan to continue research on this topic and further confirm the results on the postoperative samples obtained from patients with brain gliomas.

5. Conclusions

We discovered that studied models of rat gliomas and irradiation change the attenuation coefficient of white matter (more precisely, a corpus callosum as an example) in a different way. It was demonstrated that some tumor models have a pronounced effect on white matter µ values, due to infiltration of tumor cells, myelinated fibers destruction and edema, while other tumors cause compression of the myelinated fibers of corpus callosum without their ruptures and prominent invasion of tumor cells, which preserved the attenuation coefficient values changeless. The formation of late radiation-induced changes is characterized by focal development of edema, disruption of the integrity of myelinated fibers and a decrease in the amount of oligodendrocytes, which also leads to a decrease in µ in comparison with normal corpus callosum. However, the µ values remain statistically significantly higher compared to areas destroyed due to invasive growth of gliomas. Thus, using the OCT method, it is possible to distinguish various morphological states of the white matter, which indicates the prospects of its intraoperative use in both primary and repeated resections of malignant brain tumors.

Funding

Russian Science Foundation10.13039/501100006769 (23-25-00118).

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Schaff L. R., Mellinghoff I. K., “Glioblastoma and Other Primary Brain Malignancies in Adults: A Review,” JAMA 329(7), 574–587 (2023). 10.1001/jama.2023.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frosina G., “Recapitulating the Key Advances in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of High-Grade Gliomas: Second Half of 2021 Update,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(7), 6375 (2023). 10.3390/ijms24076375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sales A. H. A., Beck J., Schnell O., et al. , “Surgical Treatment of Glioblastoma: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends,” J. Clin. Med. 11(18), 5354 (2022). 10.3390/jcm11185354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann J., Ramakrishna R., Magge R., et al. , “Advances in Radiotherapy for Glioblastoma,” Front. Neurol. 8, 748 (2018). 10.3389/fneur.2017.00748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Y. H., Wang Z. F., Pan Z. Y., et al. , “A Meta-Analysis of Survival Outcomes Following Reoperation in Recurrent Glioblastoma: Time to Consider the Timing of Reoperation,” Front. Neurol. 10, 286 (2019). 10.3389/fneur.2019.00286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niyazi M., Andratschke N., Bendszus M., et al. , “ESTRO-EANO guideline on target delineation and radiotherapy details for glioblastoma,” Radiother. Oncol. 184, 109663 (2023). 10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leibel S., Sheline G., “Tolerance of the brain and spinal cord to conventional irradiation,” in Radiation Injury to the Nervous System (Raven; 1991), pp. 239–256 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aabedi A. A., Young J. S., Chang E. F., et al. , “Involvement of White Matter Language Tracts in Glioma: Clinical Implications, Operative Management, and Functional Recovery After Injury,” Front. Neurosci. 16, 932478 (2022). 10.3389/fnins.2022.932478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh F. C., Irimia A., Bastos D. C., et al. , “Tractography methods and findings in brain tumors and traumatic brain injury,” NeuroImage 245, 118651 (2021). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Navarrete R., Contreras-Vázquez C., León-Alvárez E., et al. , “Multimodal Neuronavigation for Brain Tumor Surgery,” in Central Nervous System Tumors (IntechOpen, 2022). 10.5772/intechopen.97216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerard I. J., Kersten-Oertel M., Hall J. A., et al. , “Brain shift in neuronavigation of brain tumors: An updated review of intra-operative ultrasound applications,” Front. Oncol. 10, 618837 (2021). 10.3389/fonc.2020.618837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sastry R., Bi W. L., Pieper S., et al. , “Applications of ultrasound in the resection of brain tumors,” Neuroimaging 27(1), 5–15 (2017). 10.1111/jon.12382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun R., Cuthbert H., Watts C., “Fluorescence-Guided Surgery in the Surgical Treatment of Gliomas: Past, Present and Future,” Cancers 13(14), 3508 (2021). 10.3390/cancers13143508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leitgeb R., Placzek F., Rank E., et al. , “Enhanced medical diagnosis for dOCTors: a perspective of optical coherence tomography,” J. BioMed. Opt. 26(10), 100601 (2021). 10.1117/1.JBO.26.10.100601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kut C., Chaichana K. L., Xi J., et al. , “Detection of human brain cancer infiltration ex vivo and in vivo using quantitative optical coherence tomography,” Sci. Transl. Med. 7(292), 292ra100 (2015). 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juarez-Chambi R. M., Kut C., Rico-Jimenez J. J., et al. , “AI-Assisted In Situ Detection of Human Glioma Infiltration Using a Novel Computational Method for Optical Coherence Tomography,” Clin Cancer Res. 25(21), 6329–6338 (2019). 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan W., Kut C., Liang W., et al. , “Robust and fast characterization of OCT-based optical attenuation using a novel frequency-domain algorithm for brain cancer detection,” Sci. Rep. 7(1), 44909 (2017). 10.1038/srep44909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achkasova K. A., Moiseev A. A., Yashin K. S., et al. , “Nondestructive label-free detection of peritumoral white matter damage using cross-polarization optical coherence tomography,” Front. Oncol. 13, 1133074 (2023). 10.3389/fonc.2023.1133074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang S., Bowden A. K., “Review of methods and applications of attenuation coefficient measurements with optical coherence tomography,” J. Biomed. Opt. 24(09), 1–17 (2019). 10.1117/1.JBO.24.9.090901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffau H., “White Matter Tracts and Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas: The Pivotal Role of Myelin Plasticity in the Tumor Pathogenesis, Infiltration Patterns, Functional Consequences and Therapeutic Management,” Front. Oncol. 12, 855587 (2022). 10.3389/fonc.2022.855587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks L. J., Clements M. P., Burden J. J., et al. , “The white matter is a pro-differentiative niche for glioblastoma,” Nat. Commun. 12(1), 2184 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-22225-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iablonovskaia L., Spryshkova N. A., “Morphologic and biologic characteristics of experimental tumors of the cerebellum in rats,” Arkh. Patol. 33(2), 50–53 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giakoumettis D., Kritis A., Foroglou N., “C6 cell line: the gold standard in glioma research,” Hippokratia 22(3), 105–112 (2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukina M., Yashin K., Kiseleva E., et al. , “Label-Free Macroscopic Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Brain Tumors,” Front. Oncol. 11, 666059 (2021). 10.3389/fonc.2021.666059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steiniger S. C., Kreuter J., Khalansky A. S., et al. , “Chemotherapy of glioblastoma in rats using doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles,” Int. J. Cancer. 109(5), 759–767 (2004). 10.1002/ijc.20048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achkasova K., Kukhnina L., Moiseev A., et al. , “Detection of acute and early-delayed radiation-induced changes in the white matter of the rat brain based on numerical processing of optical coherence tomography data,” J. Biophotonics 17(4), e202300458 (2024). 10.1002/jbio.202300458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fowler J. F., “The linear-quadratic formula and progress in fractionated radiotherapy,” Br. J. Radiol. 62(740), 679–694 (1989). 10.1259/0007-1285-62-740-679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalita O., Kazda T., Reguli S., et al. , “Effects of Reoperation Timing on Survival among Recurrent Glioblastoma Patients: A Retrospective Multicentric Descriptive Study,” Cancers 15(9), 2530 (2023). 10.3390/cancers15092530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moiseev A. A., Achkasova K. A., Kiseleva E. B., et al. , “Brain white matter morphological structure correlation with its optical properties estimated from optical coherence tomography (OCT) data,” Biomed. Opt. Express 13(4), 2393–2413 (2022). 10.1364/BOE.457467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moiseev A. A., Sherstnev E., Kiseleva E., et al. , “Depth-resolved method for attenuation coefficient calculation from Optical Coherence Tomography data for improved biological structure visualization,” J. Biophotonics 16(12), e202100392 (2023). 10.1002/jbio.202100392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vermeer K. A., Mo J., Weda J. J., et al. , “Depth-resolved model-based reconstruction of attenuation coefficients in optical coherence tomography,” Biomed. Opt. Express 5(1), 322–337 (2014). 10.1364/BOE.5.000322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menzel M., Axer M., Amunts K., et al. , “Diattenuation Imaging reveals different brain tissue properties,” Sci. Rep. 9(1), 1939 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-38506-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez C. L., Szu J. I., Eberle M. M., et al. , “Decreased light attenuation in cerebral cortex during cerebral edema detected using optical coherence tomography,” Neurophotonics 1(2), 025004 (2014). 10.1117/1.NPh.1.2.025004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michinaga S., Koyama Y., “Pathogenesis of brain edema and investigation into anti-edema drugs,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16(5), 9949–9975 (2015). 10.3390/ijms16059949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartmann K., Stein K. P., Neyazi B., et al. , “Theranostic applications of optical coherence tomography in neurosurgery?” Neurosurg. Rev. 45(1), 421–427 (2022). 10.1007/s10143-021-01599-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J., Ding N., Yu Y., et al. , “Whole-brain microcirculation detection after ischemic stroke based on swept-source optical coherence tomography,” J. Biophotonics 12(10), e201900122 (2019). 10.1002/jbio.201900122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osiac E., Mitran S. I., Manea C. N., et al. , “Optical coherence tomography microscopy in experimental traumatic brain injury,” Microsc. Res. Tech. 84(3), 422–431 (2021). 10.1002/jemt.23599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartmann K., Stein K. P., Neyazi B., et al. , “Optical coherence tomography of cranial dura mater: Microstructural visualization in vivo,” Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 200, 106370 (2021). 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Assayag O., Grieve K., Devaux B., et al. , “Imaging of non-tumorous and tumorous human brain tissues with full-field optical coherence tomography,” Neuroimage Clin. 2, 549–557 (2013). 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almasian M., Wilk L. S., Bloemen P. R., et al. , “Pilot feasibility study of in vivo intraoperative quantitative optical coherence tomography of human brain tissue during glioma resection,” J. Biophotonics 12(10), e201900037 (2019). 10.1002/jbio.201900037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strenge P., Lange B., Draxinger W., et al. , “Differentiation of different stages of brain tumor infiltration using optical coherence tomography: Comparison of two systems and histology,” Front. Oncol. 12, 896060 (2022). 10.3389/fonc.2022.896060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.