Abstract

Bullous lung disease presenting as a pneumothorax in pregnancy has not been reported in the literature to date. We present the case of a woman in her third pregnancy presenting to routine antenatal clinic with a secondary spontaneous pneumothorax in the third trimester. We describe the multidisciplinary approach to her management with obstetrics, obstetric anaesthesiology, cardiothoracic surgery and midwifery. This included decision making around conservative management in the initial disease course, preparation for delivery and a plan for definitive surgery postnatally. Caesarean section was performed at 36 weeks’ gestation owing to worsening chest pain. The underlying pathological process was deemed to be bullous lung disease which was confirmed on histology obtained from a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery procedure done postnatally. We demonstrate the importance of the multidisciplinary team approach in the care of complex and rare medical conditions in pregnancy.

Keywords: Bullous lung disease, pneumothorax in pregnancy

Introduction

We present the case of a pregnant woman presenting with a secondary pneumothorax and the importance of multidisciplinary team (MDT) management in these rare cases.

Case report

History

A 32-year-old multiparous woman presented to a routine antenatal clinic in a standalone maternity hospital at 33 weeks and 4 days of gestation. She had a history of essential hypertension, for which she was taking labetalol 500 mg six-hourly and aspirin 150 mg. She had a 10-pack-year smoking history. SARS-CoV-2 infection had been diagnosed 2 weeks prior to presentation. She did not seek medical attention at the time as she felt her symptoms were mild. She noted an ongoing cough associated with progressive dyspnea and was unable to climb one flight of stairs. Respiratory examination revealed absent air entry on the right side with hyper-resonance to percussion.

Investigations

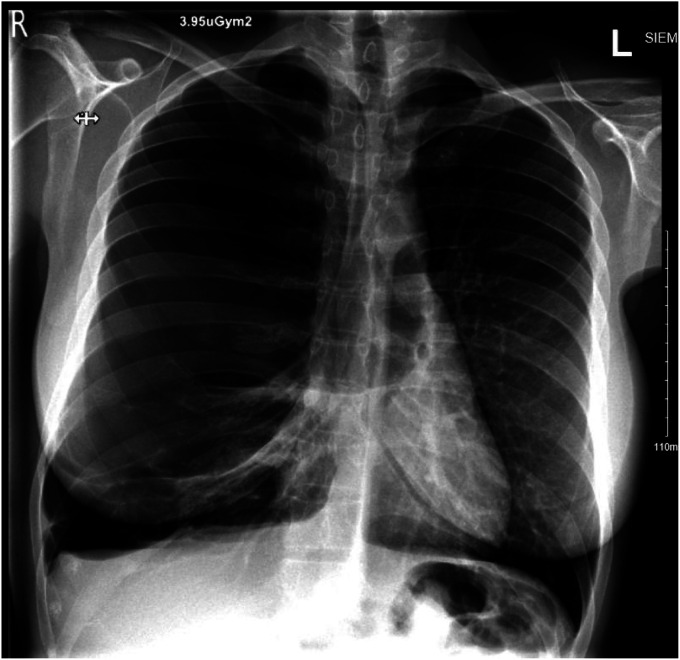

An urgent chest X-ray (CXR) (Figure 1) showed a large right-sided pneumothorax. She was commenced on oxygen via nasal prongs prior to transfer to the closest general hospital. A chest drain was inserted in the emergency department and she was admitted to the high-dependency unit (HDU) for close observation.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray.

There was a persistent air leak from the initial chest drain, and the lung failed to fully re-expand within 24 h. A second chest drain was placed under −2kPA of suction with no improvement. A third chest drain was inserted, with partial re-inflation seen on CXR. Computed tomography (CT) thorax showed significant underlying lung disease with bullous destruction of the right lung and emphysematous change of the left lung. These were new changes from normal lung imaging 4 years prior. Alpha-1 antitrypsin levels were normal at this time. She remained stable and was discharged home 6 days later with a single chest drain connected to a Portex® ambulatory chest drainage system. Paracetamol and oxycodone as required were prescribed for pain management.

At a follow-up appointment, the chest drain was noted to be working well, with stable appearances of her CXR. A MDT meeting was convened which included obstetrics, obstetric anaesthesiology, cardiothoracics and midwifery. Mode of delivery was discussed; she had had two previous uncomplicated term vaginal births and vaginal birth was not contra-indicated following MDT discussion. This was also the patient's preference and if spontaneous labour did not occur by 40 weeks’ gestation, an induction of labour would be planned. A communication plan was put in place in case of drain-related complications in the maternity hospital (given it's nature as a standalone maternity hospital). The decision was made to delay definitive surgery until after delivery.

Three days later, the patient presented with worsening dyspnea and severe pain from the site of the chest drain, requiring increased analgesia. The chest drain was adjusted and the patient was admitted to the cardiothoracic HDU. The following day the chest drain was removed and a new drain was inserted. Over the following days, she reported significant pain with escalating analgesic requirements in the form of regular paracetamol and oxycodone. Owing to the change in clinical circumstances, mode of delivery was re-considered and decision was made for delivery at 36 weeks and 1 day of gestation by non-maternity hospital. Due to the number of chest drain replacements during the clinical course with no improvement in pain or symptoms, this decision was made to allow for both adequate pain control and definitive surgical management postnatally. She underwent an uncomplicated lower segment caesarean section, delivering a live female infant. Postnatal recovery was uncomplicated. She was discharged home on day 5 postoperatively with planned outpatient follow-up with obstetrics and cardiothoracics.

Treatment

Three weeks postnatally she underwent a right-sided two-port video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) with lung volume reduction of her right upper lobe, resection of giant bullae, extensive decortication of pockets of fluid and talc insufflation for pleurodesis. Lung expansion was confirmed under direct vision prior to closure. She recovered well postoperatively and was stable at outpatient review 3 weeks later, with minimal analgesia requirements. CXR at this time showed pleural thickening with a small apical fluid collection. Histology examination confirmed emphysematous lung with respiratory bronchiolitis and a focal sub-pleural organising pneumonia. Histological examination of the cortex showed fibrinous pleuritis with chronic pleuritis and empyema.

Discussion

Pneumothorax is defined as air in the pleural space and can occur spontaneously or secondary to trauma or iatrogenic causes. 1 It is estimated to occur in 5.8/100,000 women per year outside of pregnancy. 2 A recent systematic review of pneumothorax in pregnancy described 87 cases of spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy, most commonly occurring in the perinatal period.3–7 There has only been one case reported of bullous emphysema in pregnancy, which occurred in a patient with known alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. 8

A MDT approach to the management of complex medical conditions in pregnancy is imperative. 9 There have been various management strategies for pneumothorax in pregnancy described in the literature which align with management outside of pregnancy. Initial management includes observation if the mother is not dyspnoeic and the pneumothorax is small.3,10 Other treatment options include chest drain placement, VATS or thoracotomy for recurrent or persistent pneumothoraces. 6 VATS is a useful addition in the evaluation and management of recurrent pneumothorax and bullous lung disease.11–13

Bullous lung disease occurs due to air-filled spaces within the lung. It is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, infection, malignancy or cystic lung disease. Recent case reports describe associations with electronic cigarette use, cannabis use and severe COVID pneumonitis.14–16 In our patient, bullous lung disease had developed relatively rapidly since previous normal lung imaging less than 4 years prior. This has previously been described in male patients in association with smoking or COVID infection.17,18 In our case, pregnancy and recent COVID infection on a background of heavy cigarette consumption were likely major contributors.

Pneumothorax recurrence is more common in pregnancy. 10 Observation and aspiration are suitable initial management options during pregnancy with a plan for corrective VATS performed after delivery. 6 As was employed in this case, the guidelines recommend close MDT input. If a chest drain is not in place, epidural anaesthesia is preferable to general anaesthesia intrapartum to avoid positive pressure ventilation. An assisted vaginal delivery can be considered to minimise the active second stage of labour. By shortening the length of Valsalva, this can help to prevent increased intrathoracic pressure, it's associated barotrauma and decrease the recurrence risk of pneumothorax. 10

As this case was managed across two sites – a maternity unit and a general hospital, clear written and verbal communication was very important with pathways for emergency communication highlighted. This case shows the importance of an MDT approach in the care of complex medical conditions in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.

Guarantor: GM guarantees the manuscript's accuracy.

Contributorship: All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Gabriela McMahon https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1511-6172

Claire M. McCarthy https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8342-8050

References

- 1.van Berkel V, Kuo E, Meyers BF. Pneumothorax, bullous disease, and emphysema. Surg Clin North Am 2010; 90: 935–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta D. Epidemiology of pneumothorax in England. Thorax 2000; 55: 666–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrafiotis AC, Assouad J, Lardinois I, et al. Pneumothorax and pregnancy: a systematic review of the current literature and proposal of treatment recommendations. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021; 69: 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lal A, Anderson G, Cowen M, et al. Pneumothorax and pregnancy. Chest 2007; 132: 1044–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terndrup TE, Bosco SF, McLean ER. Spontaneous pneumothorax complicating pregnancy–case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med 1989; 7: 245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanase Y, Yamada T, Kawaryu Y, et al. A case of spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy and review of the literature. Kobe J Med Sci 2007; 53: 251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooley S, Geary M, Keane DP. Spontaneous pneumothorax and febrile neutropenia in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 2002; 22: 91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson AR. Pregnancy and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63: 817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor C, McCance DR, Chappell L, et al. Implementation of guidelines for multidisciplinary team management of pregnancy in women with pre-existing diabetes or cardiac conditions: results from a UK national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017; 17: 434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65: ii18–ii31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrakis I, Katsamouris A, Drossitis I, et al. Usefulness of thoracoscopic surgery in the diagnosis and management of thoracic diseases. J Cardiovasc Surg Torino 2000; 41: 767–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onugha O, Ivey R, McKenna R. Novel techniques and approaches to minimally invasive thoracic surgery. Surg Technol Int 2017; 30: 231–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng CSH, Yim APC. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) bullectomy for emphysematous/bullous lung disease. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg MMCTS 2005; 2005, mmcts.2004.000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalra SS, Pais F, Harman E, et al. Rapid development of bullous lung disease: a complication of electronic cigarette use. Thorax 2020; 75: 359. https://mmcts.org/tutorial/1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra R, Patel R, Khaja M. Cannabis-induced bullous lung disease leading to pneumothorax: case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e6917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berhane S, Tabor A, Sahu A, et al. Development of bullous lung disease in a patient with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13: e237455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J-H, Kim J, Lee J-K, et al. A case of bilateral giant bullae in young adult. Tuberc Respir Dis 2013; 75: 222–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pednekar P, Amoah K, Homer R, et al. Case report: bullous lung disease following COVID-19. Front Med 2021; 8: 770778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]