Abstract

Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) is an essential chromatin-binding protein whose mutations cause Rett syndrome (RTT), a severe neurological disorder that primarily affects young females. The canonical view of MeCP2 as a DNA methylation-dependent transcriptional repressor has proven insufficient to describe its dynamic interaction with chromatin and multifaceted roles in genome organization and gene expression. Here we used single-molecule correlative force and fluorescence microscopy to directly visualize the dynamics of wild-type and RTT-causing mutant MeCP2 on DNA. We discovered that MeCP2 exhibits distinct one-dimensional diffusion kinetics when bound to unmethylated versus CpG methylated DNA, enabling methylation-specific activities such as co-repressor recruitment. We further found that, on chromatinized DNA, MeCP2 preferentially localizes to nucleosomes and stabilizes them from mechanical perturbation. Our results reveal the multimodal behavior of MeCP2 on chromatin that underlies its DNA methylation- and nucleosome-dependent functions and provide a biophysical framework for dissecting the molecular pathology of RTT mutations.

Subject terms: Single-molecule biophysics, Chromatin, Molecular biophysics, DNA methylation

Using single-molecule techniques, the authors find that the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2, whose mutations cause Rett syndrome, exhibits distinctive behaviors when bound to nucleosomes versus free DNA, thus directing its multifaceted functions on chromatin.

Main

Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) is a highly abundant chromatin-binding protein in mature neurons and was identified as a DNA methylation-dependent transcriptional repressor1–3. Mutations in the X-linked MECP2 gene cause Rett syndrome (RTT), a severe genetic disorder that occurs 1 in ~10,000 live female births and is characterized by progressive neurological dysfunction and developmental regression4–6. On the other hand, duplication of the MECP2 gene causes MeCP2 duplication syndrome (MDS), another type of rare neurodevelopmental disorder that primarily affects males7,8. Currently there is no cure for RTT or MDS, in part because the complex molecular functions of MeCP2 on chromatin remain poorly understood9,10.

MeCP2 is a highly disordered and basic protein that exhibits preference for binding methylated cytosines in both CpG and non-CpG contexts but also potently binds unmethylated DNA11–13 on which each MeCP2 molecule occupies ~11 base pairs (bp)14. MeCP2 has also been shown to interact with nucleosomes and nucleosome arrays in vitro15–17. The genomic distribution of MeCP2 has been observed to correlate with nucleosome occupancy18. Additionally, MeCP2 can undergo liquid–liquid phase separation with chromatin, which is modulated by RTT mutations19,20. The pervasive genomic binding of MeCP2 has hampered our understanding of its preferred chromatin target sites10,21. MeCP2 has also been reported to associate with other effector proteins, notably the NCoR1/2 co-repressor complex22,23. It is generally presumed that MeCP2’s gene silencing activities are mediated by these effectors, but whether MeCP2 possesses an intrinsic repressive activity remains to be determined.

Myriad RTT mutations are associated with distinct clinical phenotypes. How these mutations perturb MeCP2’s molecular behavior and function at chromatin remains largely unclear. In addition, it is perplexing why MeCP2, despite its high abundance, is exquisitely dosage sensitive, with mild under- or overexpression leading to RTT-like or MDS-like symptoms24. Therefore, elucidating the distribution and dynamics of MeCP2 and its disease mutants on chromatin is imperative toward developing targeted therapies. Single-molecule imaging of MeCP2 in vivo has proven fruitful25, but the heterogeneous cellular environment precludes a definitive description of the biophysical properties of MeCP2 bound to specific chromatin substrates and its interplay with other chromatin-binding factors.

In this work, we used single-molecule correlative force and fluorescence microscopy26 to probe the dynamics and mechanics of purified human MeCP2 and its disease variants on DNA and chromatin substrates. Our results reveal a remarkably diverse repertoire of binding modes of MeCP2 on chromatin and suggest a nucleosome-centric model for MeCP2’s dosage sensitivity and repressive roles. Our work also reveals that RTT mutations differentially disrupt the MeCP2–chromatin interaction, providing a quantitative framework for understanding the molecular mechanism of MeCP2-related disorders.

Results

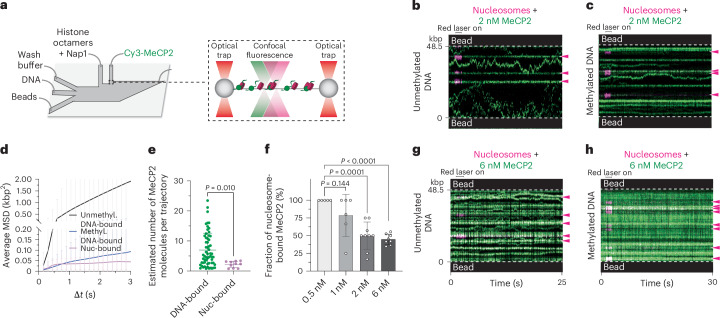

CpG methylation suppresses MeCP2 diffusion on DNA

We purified recombinant full-length human MeCP2 with two of the three native cysteines (C339 and C413) replaced by serines, leaving the remaining C429 for site-specific fluorescent labeling. The replaced residues have not been associated with disease, nor do they affect MeCP2’s binding to DNA (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Using a single-molecule instrument that combines dual-trap optical tweezers and scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy27,28, we first examined the behavior of MeCP2 on methylation-free 48.5-kbp-long bacteriophage λ genomic DNA. A single λ DNA molecule was tethered between two optically trapped beads, held at 1 pN of tension, incubated in a channel containing Cy3-labeled MeCP2, and then moved to another protein-free channel for imaging (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 2a). Surprisingly, we observed that MeCP2 often exhibited long-lived and long-range one-dimensional (1D) diffusive motions on DNA (Fig. 1b,c and Extended Data Fig. 2a). The mobility of MeCP2 varied among individual trajectories (Fig. 1b,c), which may be attributed to the local DNA sequence and the molecular weight of the diffusing unit. Based on the fluorescence intensity, we estimated that each trajectory contained 8.7 ± 7.9 MeCP2 molecules (mean ± standard deviation (s.d.), n = 77), indicating that MeCP2 can diffuse as oligomeric units on DNA. One caveat is that independent MeCP2 units could not be spatially resolved in our assay if they were located within the same diffraction-limited spot (~300 nm). MeCP2 oligomerization appears to depend on DNA binding, as the protein exists primarily as monomers in solution based on mass photometry (MP) results (Extended Data Fig. 1b). We plotted the diffusion coefficient (D) against the estimated number of MeCP2 molecules per trajectory and found that larger oligomers tended to diffuse more slowly (Extended Data Fig. 2b).

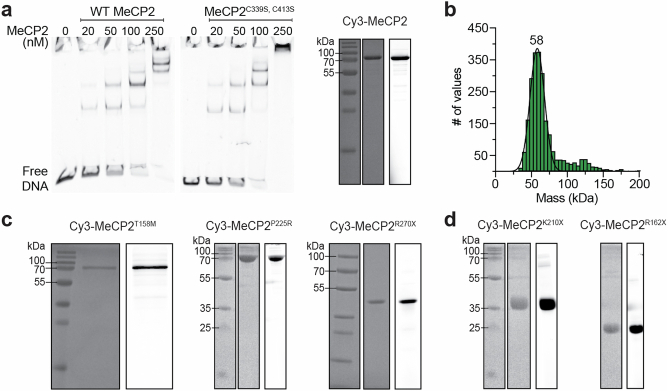

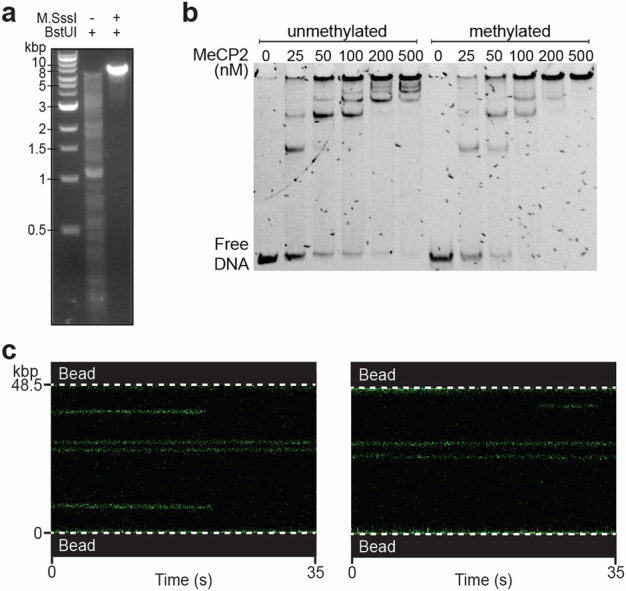

Extended Data Fig. 1. MeCP2 constructs used in this work.

a, (Left) EMSA assay showing the products of 50 nM of 207-bp unmethylated DNA incubated with an increasing concentration of MeCP2 containing all three native cysteines or the single-cysteine version (C339S, C413S) of MeCP2. The latter construct was referred to as MeCP2 in this study. (Right) SDS–PAGE gel for Cy3-labeled MeCP2 (left lane: protein ladder; middle lane: Coomassie Blue staining; right lane: fluorescence scanning). b, Mass distribution for Cy3-labeled MeCP2 obtained by mass photometry with peak value indicated. c, SDS–PAGE gels for Cy3-MeCP2T158M (left), Cy3-MeCP2P225R (middle), and Cy3-MeCP2R270X (right). d, SDS–PAGE gels for Cy3-MeCP2K210X (left) and Cy3-MeCP2R162X (right).

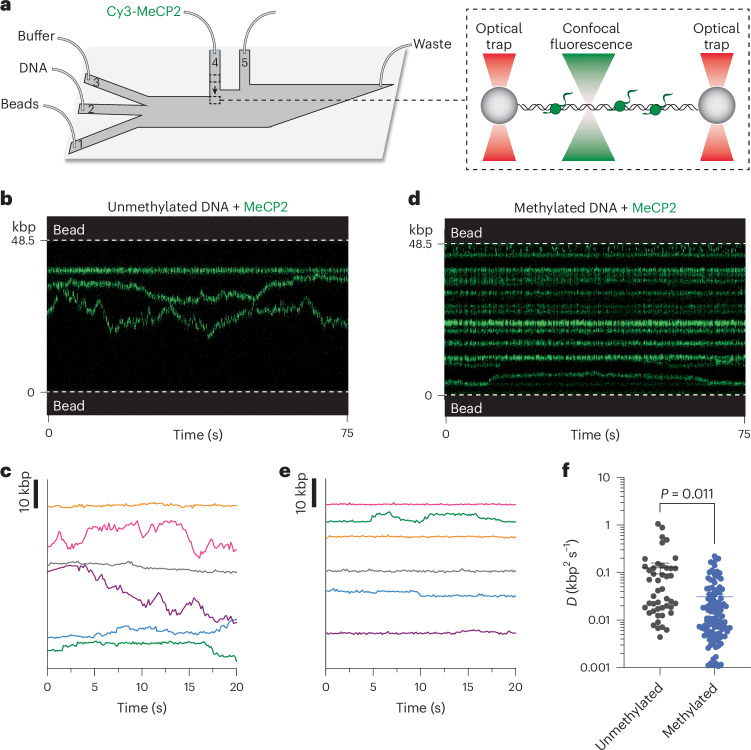

Fig. 1. CpG methylation suppresses MeCP2 diffusion on DNA.

a, Schematic of the experimental setup. A single λ DNA molecule was tethered between a pair of optically trapped beads through biotin–streptavidin linkage. The tether was moved to a channel containing Cy3-MeCP2 to allow protein binding and subsequently to a protein-free channel for imaging. b, Representative kymograph of an unmethylated DNA tether incubated with 2 nM Cy3-MeCP2. The experiment was independently repeated with 22 tethers yielding similar results. c, Example MeCP2 trajectories on unmethylated DNA taken from independent tethers showing their diffusive motions (offset vertically for clarity). d, Representative kymograph of a CpG methylated DNA tether incubated with 2 nM Cy3-MeCP2. The experiment was independently repeated with 22 tethers yielding similar results. e, Example MeCP2 trajectories on CpG methylated DNA (offset vertically for clarity). f, Diffusion coefficients (D) for Cy3-MeCP2 trajectories on unmethylated (black) (n = 46 from 22 independent tethers) and CpG methylated (blue) (n = 109 from 22 independent tethers) DNA. The bars represent mean and s.e.m. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction.

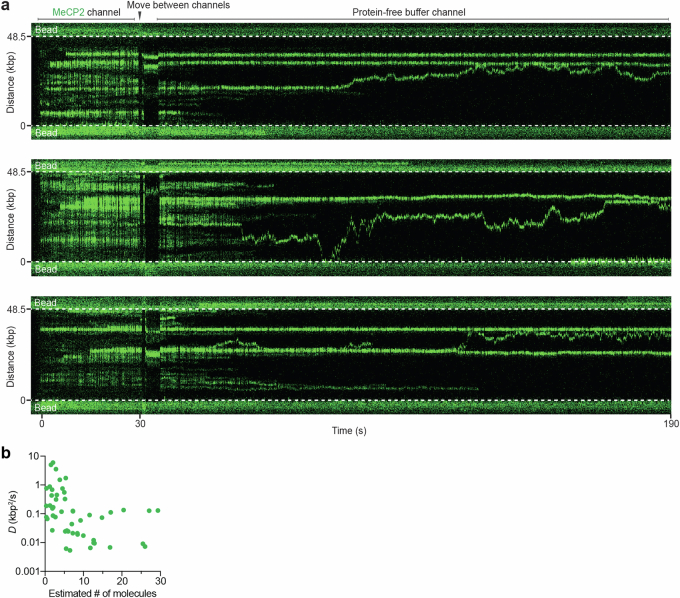

Extended Data Fig. 2. Additional data on MeCP2 interaction with unmethylated DNA.

a, Representative kymographs of unmethylated λ DNA tethers bound with Cy3-MeCP2. Each DNA tether was incubated in a channel containing 2 nM Cy3-labeled WT MeCP2 for 30 s and then moved to a protein-free channel for imaging. b, Diffusion coefficient (D) for MeCP2 trajectories on unmethylated DNA is plotted against the estimated number of MeCP2 molecules in the trajectory (n = 50 trajectories from 22 independent tethers).

Next, we used the bacterial M.SssI methyltransferase to methylate the CpG sites within the λ DNA (3,113 in total) and imaged Cy3-MeCP2 on methylated DNA tethers (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). We found that the average number of MeCP2 trajectories per methylated DNA tether was approximately four times higher than that per unmethylated DNA tether, consistent with previous work showing that CpG methylation enhances the affinity of MeCP2 to DNA13,17. Notably, we also observed that CpG methylation drastically suppressed MeCP2 diffusion (Fig. 1d,e). Mean squared displacement (MSD) analysis showed significantly lower D values for MeCP2 diffusion on methylated DNA than on unmethylated DNA (0.031 ± 0.004 kbp2 s−1 and 0.126 ± 0.032 kbp2 s−1 respectively, mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.)) (Fig. 1f). To exclude the possibility that the suppressed MeCP2 diffusion on methylated DNA was caused by spatial confinement due to enhanced binding, we titrated down the concentration of MeCP2 and still observed a low mobility even when the tethers were sparsely bound with MeCP2 (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Together, these results reveal an intrinsic activity of MeCP2 to scan on DNA, which is suppressed by CpG methylation.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Additional data on MeCP2 interaction with methylated DNA.

a, CpG methylation by M.SssI bacterial methyltransferase is assessed via BstUI digestion. Agarose gel (1%) shows blocked BstUI digestion of 9-kbp linear DNA after M.SssI treatment. b, EMSA showing the products of 50 nM of 147-bp unmethylated or CpG methylated DNA incubated with an increasing concentration of MeCP2. In-well species correspond to higher-order MeCP2:DNA assemblies. c, Representative kymographs of methylated λ DNA tethers incubated with 0.5 nM of Cy3-MeCP2.

RTT mutations differentially perturb MeCP2’s behavior on DNA

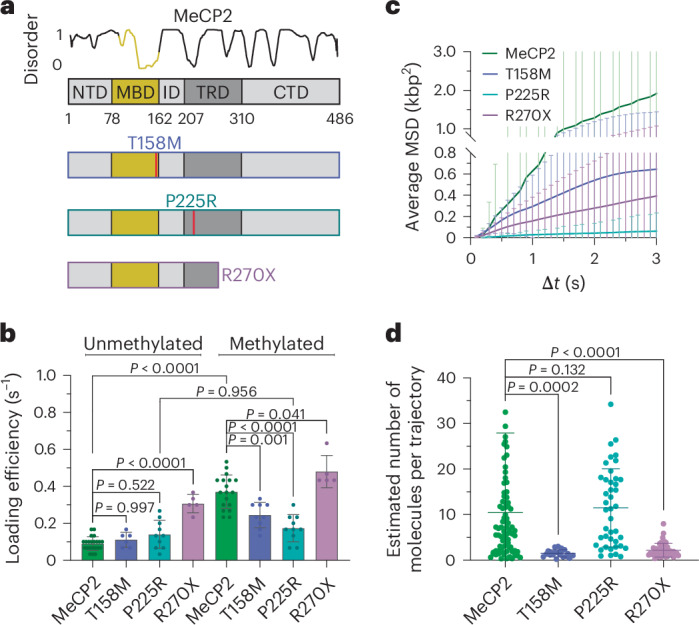

Our single-molecule platform enabled us to dissect the effect of specific RTT mutations on the dynamic behavior of MeCP2 on DNA. We purified and fluorescently labeled a panel of MeCP2 mutants that display a variety of clinical phenotypes29–31 (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 1c). We first studied T158M, a missense mutation within the methyl binding domain (MBD) of MeCP2 that accounts for ~12% of all RTT cases29,32. Our data showed that T158M caused a significant reduction in the level of MeCP2 binding to methylated DNA but no change in its binding to unmethylated DNA (Fig. 2b), consistent with previous bulk results33. Next, we examined the P225R mutation, which resides inside the transcriptional repression domain (TRD) of MeCP2 (Fig. 2a). We found that MeCP2P225R exhibited a markedly diminished ability to bind methylated DNA—to an even larger degree than MeCP2T158M (Fig. 2b). Additionally, P225R significantly slowed down MeCP2’s diffusion on unmethylated DNA (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 4a,b), where it exhibited a similar mobility compared with that on methylated DNA (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Note that MeCP2P225R’s low mobility is not caused by spatial confinement, as this mutant displayed a similar level of binding to unmethylated DNA compared with wild-type (WT) MeCP2 (Fig. 2b). Thus, MeCP2P225R appears to have an impaired ability to discriminate between unmethylated and methylated DNA. We next investigated R270X, a truncating mutation lacking the entire C-terminal domain (CTD) and part of the TRD (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, MeCP2270X displayed elevated binding to DNA, especially to the unmethylated form (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 4a). In addition, the MeCP2R270X trajectories contained fewer protein molecules on average compared with the full-length MeCP2 (Fig. 2d), suggesting that the TRD and CTD contribute significantly to MeCP2 oligomerization on DNA.

Fig. 2. RTT mutations differentially alter MeCP2’s behavior on DNA.

a, Domain structure of MeCP2 and the corresponding PONDR disorder score. Three RTT mutants (T158M, P225R and R270X) are shown below. b, Loading efficiency for 2 nM Cy3-labeled MeCP2 (n = 22 independent tethers), MeCP2T158M (n = 6 independent tethers), MeCP2P225R (n = 10 independent tethers) and MeCP2R270X (n = 5 independent tethers) binding to unmethylated DNA, and for 2 nM Cy3-labeled MeCP2 (n = 18 independent tethers), MeCP2T158M (n = 9 independent tethers), MeCP2P225R (n = 10 independent tethers) and MeCP2R270X (n = 5 independent tethers) binding to CpG methylated DNA. Each dot represents data from one independent tether. The bars represent mean and s.d. c, Average MSD plot for Cy3-labeled MeCP2 (n = 78 from 22 independent tethers), MeCP2T158M (n = 20 from 6 independent tethers), MeCP2P225R (n = 40 from 10 independent tethers) and MeCP2R270X (n = 44 from 5 independent tethers) trajectories on unmethylated DNA. The error bars represent s.d. d, Estimated number of molecules per trajectory for Cy3-labeled MeCP2 (n = 77 from 22 independent tethers), MeCP2T158M (n = 20 from 6 independent tethers), MeCP2P225R (n = 42 from 10 independent tethers) and MeCP2R270X (n = 44 from 5 independent tethers) on unmethylated DNA. The bars represent mean and s.d. The significance for b and d was calculated using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons.

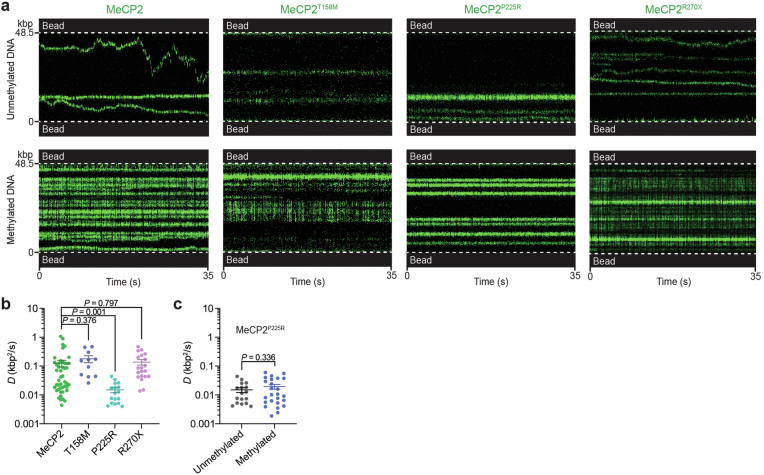

Extended Data Fig. 4. Additional data on the interaction of MeCP2 RTT mutants with DNA.

a, Representative kymographs of unmethylated (top) and methylated (bottom) λ DNA tethers incubated with 2 nM Cy3-labeled MeCP2 or three RTT variants (T158M, P225R, R270X). b, Diffusion coefficients (D) for WT (n = 46 from 22 independent tethers), T158M (n = 11 from 6 independent tethers), P225R (n = 17 from 10 independent tethers), and R270X (n = 20 from 5 independent tethers) Cy3-MeCP2 trajectories on unmethylated DNA. Bars represent mean and s.e.m. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction for each pair. c, Diffusion coefficients (D) for MeCP2P225R on unmethylated (n = 17 from 10 independent tethers) and methylated (n = 25 from 10 independent tethers) DNA. Bars represent mean and s.e.m. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction.

MeCP2 stably binds nucleosomes within chromatinized DNA

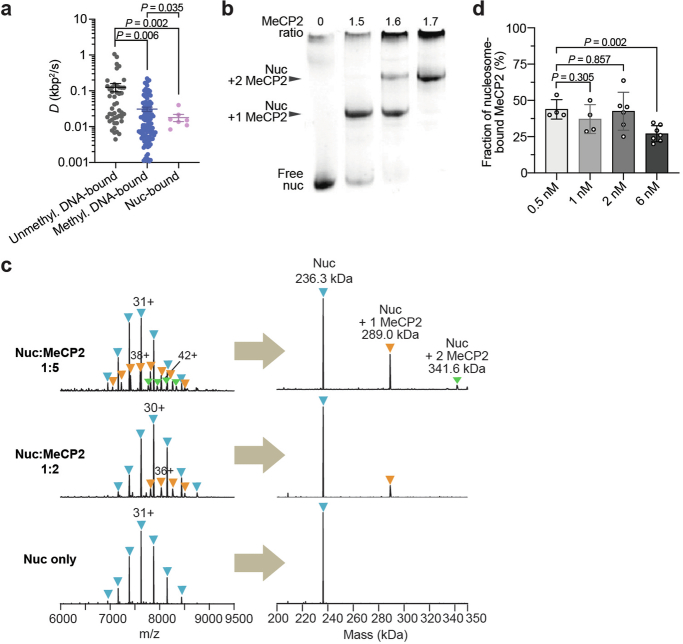

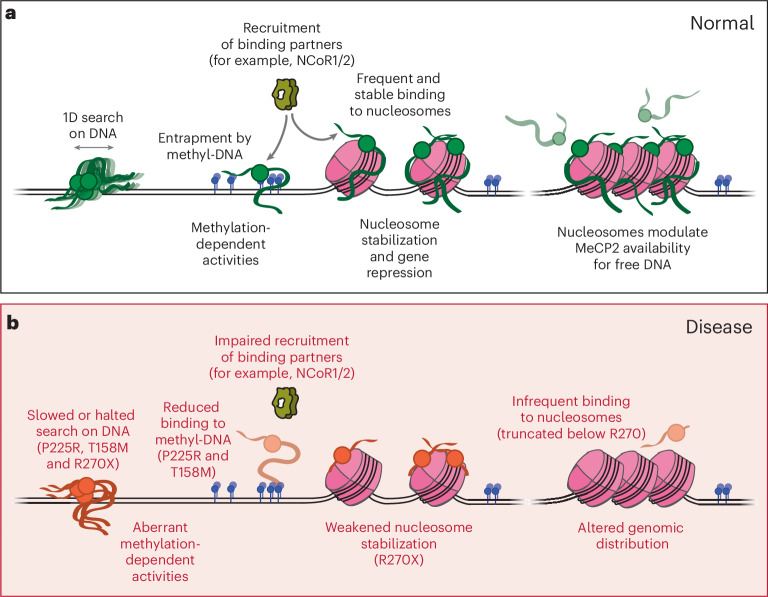

We next sought to visualize the behavior of MeCP2 on chromatinized DNA. To this end, we reconstituted nucleosomes on unmethylated λ DNA tethers in situ using LD655-labeled human histone octamers and the histone chaperone Nap1 (ref. 34) (Fig. 3a). Nucleosomes were sparsely loaded (three to ten per tether) so individual loci could be spatially resolved. We then incubated the nucleosomal DNA tether with Cy3-MeCP2 and simultaneously monitored MeCP2 and nucleosome fluorescence signals via dual-color imaging. Strikingly, we observed frequent colocalization and stable association of MeCP2 with nucleosomes, in contrast to the diffusive MeCP2 trajectories at the intervening bare DNA regions (Fig. 3b). MeCP2 was also observed to stably colocalize with nucleosomes loaded on CpG methylated DNA tethers (Fig. 3c). MSD analysis also supported the notion that MeCP2 remains immobile when bound to nucleosomes (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 5a), as the extracted diffusion coefficient approaches the lower limit that can be measured in our setup and resembles the value for other statically bound proteins35.

Fig. 3. MeCP2 preferentially and stably associates with nucleosomes on chromatinized DNA.

a, Schematic of the experimental setup. LD655-labeled nucleosomes and Cy3-labeled MeCP2 were simultaneously monitored via two-color confocal fluorescence microscopy. b,c, Representative kymograph of a nucleosome-containing unmethylated (b) or CpG methylated (c) DNA tether incubated with 2 nM Cy3-MeCP2. A red laser was flashed on briefly to locate the nucleosomes within the tether. The arrowheads denote nucleosome positions. The experiment was independently repeated with 22 (unmethylated) and 18 (methylated) tethers yielding similar results. d, Average MSD plot for Cy3-MeCP2 trajectories on unmethylated bare DNA (n = 78 from 22 independent tethers), methylated bare DNA (n = 200 from 18 independent tethers) or colocalized with nucleosome loci on unmethylated chromatinized DNA (n = 22 from 6 independent tethers). The error bars represent s.d. e, Estimated number of Cy3-MeCP2 molecules per trajectory on unmethylated bare DNA or bound to nucleosomes on unmethylated DNA. The bars represent mean and s.d. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. f, Fraction of Cy3-MeCP2 trajectories that were colocalized with nucleosome loci on unmethylated DNA in the presence of 0.5 nM (from 5 independent tethers), 1 nM (from 6 independent tethers), 2 nM (from 9 independent tethers) or 6 nM (from 8 independent tethers) MeCP2. The bars represent mean and s.d. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test for each pair. g,h, Representative kymograph of a nucleosome-containing unmethylated (g) or CpG methylated (h) DNA tether incubated with 6 nM Cy3-MeCP2. The arrowheads denote nucleosome positions. The experiment was independently repeated with 8 (unmethylated) and 7 (methylated) tethers yielding similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Additional data on MeCP2-nucleosome interaction.

a, Diffusion coefficients (D) for Cy3-MeCP2 trajectories bound to unmethylated bare DNA (n = 46 from 22 independent tethers), CpG methylated bare DNA (n = 109 from 22 independent tethers), and nucleosomes wrapped with unmethylated DNA (n = 7 from 6 independent tethers). Bars represent mean and s.e.m. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction for each pair. b, EMSA showing the products of 330 nM of mononucleosomes wrapped by 207-bp unmethylated DNA incubated with increasing molar ratios of MeCP2. Shifted bands correspond to the putative 1:1 and 2:1 MeCP2:nucleosome complexes. In-well species likely correspond to higher-order MeCP2:nucleosome assemblies or condensates15,31. c, Native mass spectrometry spectra (left) and the corresponding deconvolved mass spectra (right) for 2 µM of mononucleosomes wrapped by 207-bp unmethylated DNA incubated with different amounts of MeCP2. Addition of two-fold or five-fold molar excess of MeCP2 to the nucleosome sample yielded additional peaks corresponding to the binding of one or two 52.3-kDa MeCP2. d, Fraction of Cy3-MeCP2 trajectories that were colocalized with nucleosome loci on methylated DNA in the presence of 0.5 nM (from 4 independent tethers), 1 nM (from 4 independent tethers), 2 nM (from 6 independent tethers), or 6 nM (from 7 independent tethers) MeCP2. Bars represent mean and s.d. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test for each pair.

We then analyzed the number of MeCP2 molecules at nucleosomal loci on the basis of the fluorescence intensity and found the mean value to be much lower than that on bare DNA (Fig. 3e). This conclusion is corroborated by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and native mass spectrometry (nMS), both showing that each nucleosome typically accommodates one or two molecules of MeCP2 (Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). Although the available bare DNA sites vastly outnumbered the nucleosome sites per tether, we observed a comparable number of nucleosome-bound MeCP2 units versus bare-DNA-bound MeCP2 units (Fig. 3b,c). Within unmethylated nucleosomal DNA tethers, essentially all nucleosomes were occupied by MeCP2 even at a low protein concentration. As we increased the MeCP2 concentration, more MeCP2 units bound to bare DNA (Fig. 3f–h). A similar trend was observed on methylated nucleosomal DNA tethers, although the nucleosome-bound MeCP2 fraction was lower compared with unmethylated tethers given MeCP2’s higher affinity to methylated DNA (Extended Data Fig. 5d). These results indicate that MeCP2 preferentially targets nucleosome sites within chromatinized DNA until they are fully occupied.

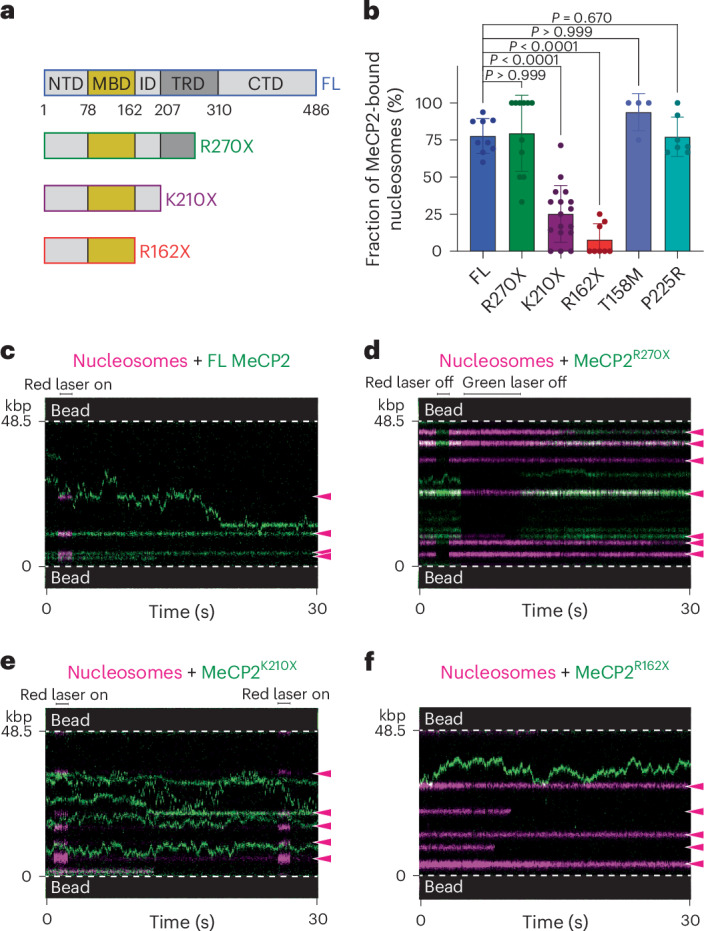

MeCP2–nucleosome interaction requires domains outside the MBD

To map the regions in MeCP2 that are important for its nucleosome binding, we performed single-molecule experiments with a series of MeCP2 truncations (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). We found that MeCP2R270X retained the level of nucleosome colocalization similar to the full-length protein, as did the two missense RTT mutants P225R and T158M (Fig. 4b–d). However, MeCP2K210X and MeCP2R162X showed significantly diminished nucleosome targeting (Fig. 4b–f). Therefore, part of the TRD—a domain originally described to mediate transcriptional repression—is critical to MeCP2’s nucleosome-binding activity. Notably, we found that MeCP2K210X and MeCP2R162X still retained the ability to bind bare DNA and undergo diffusion (Fig. 4e,f).

Fig. 4. Nucleosome targeting by MeCP2 requires domains outside its MBD.

a, Domain structure of full-length (FL) MeCP2 and three truncations R270X, K210X, and R162X. b, Fraction of nucleosomes loaded on unmethylated DNA tethers that were colocalized with MeCP2 after incubation with 2 nM FL (n = 9 independent tethers), R270X (n = 11 independent tethers), K210X (n = 17 independent tethers), R162X (n = 8 independent tethers), T158M (n = 4 independent tethers) or P225R (n = 7 independent tethers) Cy3-MeCP2. Each dot represents data from one independent tether. The bars represent mean and s.d. Significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. c–f, Representative kymographs of an LD655-nucleosome-containing unmethylated DNA tether bound with Cy3-MeCP2 (c), Cy3-MeCP2R270X (d), Cy3-MeCP2K210X (e) or Cy3-MeCP2R162X (f). The arrowheads denote nucleosome positions.

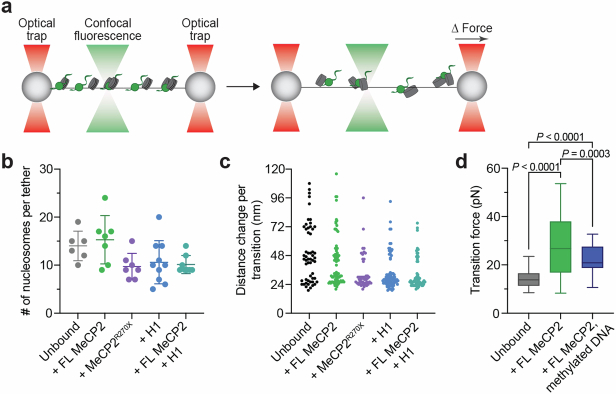

MeCP2 enhances the mechanical stability of nucleosomes

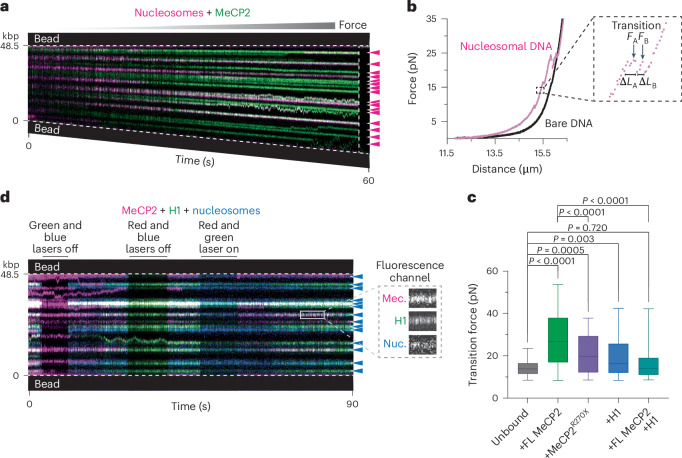

Next, we explored the consequences of MeCP2’s prevalent targeting to nucleosomes. Given that nucleosomes serve as strong barriers against the transcription machinery36,37, we asked whether the stable binding of MeCP2 alters the mechanical properties of the nucleosome that could in turn modulate transcription. We thus conducted mechanical pulling experiments on individual nucleosomal DNA tethers (Extended Data Fig. 6). The resultant force–distance (F–d) curves contain transitions that signify the unwrapping of individual nucleosomes38. We then performed the pulling experiments in the presence of MeCP2 and simultaneously monitored the fluorescence signals from Cy3-MeCP2 and LD655-nucleosomes. Most nucleosome-bound MeCP2 remained associated with the nucleosome throughout pulling (Fig. 5a). Upon analyzing the F–d curves, we found that MeCP2 significantly raised the average force required to unwrap the nucleosome (Fig. 5b,c), providing evidence for a direct stabilization effect of MeCP2 on chromatin. The stabilization effect of MeCP2 was also observed on nucleosome-containing methylated DNA tethers (Extended Data Fig. 6d). In the control experiment where we pulled on MeCP2-bound bare DNA tethers, we did not observe any noticeable transitions in the same force regime (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, the nucleosome-stabilizing effect was diminished when the full-length MeCP2 was replaced with MeCP2R270X (Fig. 5c) even though this truncating mutant is still able to bind nucleosomes (Fig. 4b).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Evaluation of in situ nucleosome loading on λ DNA tethers.

a, Schematic of the experimental setup. Nucleosomal DNA was formed by incubating a λ DNA tether with histone octamers and Nap1, and then subjected to mechanical pulling by separating the two traps at a constant speed, resulting in force-induced nucleosome unwrapping. b, Number of nucleosomes loaded per tether as estimated by the number of nucleosome unwrapping events detected in the force-distance curves of tethers with no MeCP2 or H1 bound (n = 6 independent tethers), bound with full-length (FL) MeCP2 (n = 7 independent tethers), with MeCP2R270X (n = 7 independent tethers), with H1 (n = 10 independent tethers), or with both FL MeCP2 and H1 (n = 8 independent tethers). Bars represent mean and s.d. c, Distribution of the distance change per transition recorded from force-distance curves of tethers with no MeCP2 or H1 bound (n = 61 from 6 independent tethers), bound with FL MeCP2 (n = 76 from 7 independent tethers), with MeCP2R270X (n = 50 from 7 independent tethers), with H1 (n = 79 from 10 independent tethers), or with both FL MeCP2 and H1 (n = 63 from 8 independent tethers). Transition sizes are multiples of 24 nm, consistent with the unwrapping of the inner turn DNA of individual nucleosomes. d, Distribution of transition forces recorded from force-distance curves of nucleosomal DNA tethers with no MeCP2 bound (n = 84 from 5 independent tethers), bound with FL MeCP2 (n = 107 from 7 independent tethers), or methylated nucleosomal DNA tethers bound with FL MeCP2 (n = 55 from 5 independent tethers). Box boundaries represent 25th to 75th percentiles, middle bar represents median, and whiskers represent minimum and maximum values. Significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons.

Fig. 5. MeCP2 enhances the mechanical stability of nucleosomes.

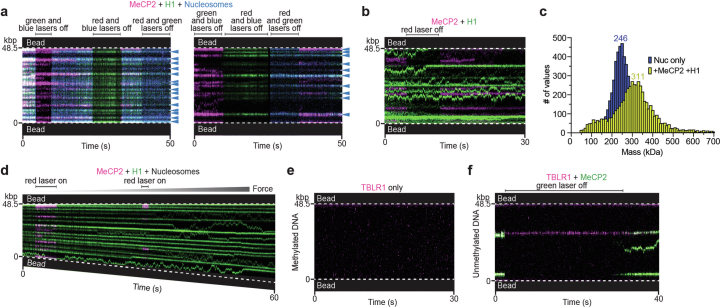

a, Representative kymograph of an LD655-nucleosome-containing unmethylated DNA tether bound with Cy3-MeCP2 and pulled to high forces by gradually increasing the inter-bead distance. The vertical dotted line denotes the time when the tether ruptured. The arrowheads denote nucleosome positions. b, Representative force–distance curve of a MeCP2-bound nucleosome-containing DNA tether (red) showing force-induced transitions overlaid on a force–distance curve of a MeCP2-bound bare DNA tether (black). The inset shows a zoom-in view of two example transitions for which the distance change (ΔL) and the transition force are recorded. The experiment was independently repeated with 7 (nucleosomal DNA) and 5 (bare DNA) tethers yielding similar results. c, Distribution of transition forces recorded from force–distance curves of nucleosomal DNA tethers with no MeCP2 or H1 bound (n = 84 from 5 independent tethers), bound with FL MeCP2 (n = 107 from 7 independent tethers), MeCP2R270X (n = 68 from 7 independent tethers), H1 (n = 106 from 10 independent tethers) or both FL MeCP2 and H1 (n = 81 from 8 independent tethers). The box boundaries represent the 25th to 75th percentiles, the middle bar represents the median and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values. Significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. d, Representative kymograph of an unmethylated DNA tether containing AF488-labeled nucleosomes and incubated with Cy5-labeled FL MeCP2 and Cy3-labeled H1. Lasers were switched on and off to confirm fluorescence signals from each channel. The arrowheads denote nucleosome positions. The inset shows a zoom-in view of individual fluorescence channels at a nucleosome site (Nuc.) where MeCP2 (Mec.) and H1 colocalized.

MeCP2 and H1 co-bind nucleosomes

Linker histone H1 is another major regulator of eukaryotic chromatin that compacts nucleosomes39. Whether MeCP2 and H1 compete for chromatin binding remains under debate3,14,40. To directly visualize the interplay between these two chromatin regulators, we performed three-color single-molecule fluorescence experiments with Cy3-labeled H1.4, Cy5-labeled MeCP2 and AF488-labeled nucleosomes loaded on λ DNA tethers. Contradictory to an antagonistic binding model, we observed frequent colocalization of H1 and MeCP2 at nucleosome sites (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 7a). MeCP2 signal was detected at the majority (63%) of H1-bound nucleosomes in our experiment. Of note, MeCP2 and H1 were rarely observed to colocalize on bare DNA (Extended Data Fig. 7b), suggesting that their interaction mainly occurs at the nucleosome. The existence of the ternary complex is further supported by MP results, which showed a mass peak consistent with a nucleosome–MeCP2–H1 complex with 1:1:1 stoichiometry (Extended Data Fig. 7c). We then investigated how the co-binding of MeCP2 and H1 impinges on nucleosome stability. Notably, pulling on nucleosomal DNA tethers incubated with both MeCP2 and H1 yielded an average transition force significantly lower than the value for tethers incubated with MeCP2 only (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 7d). Together, these results reveal that the nucleosome can simultaneously accommodate both H1 and MeCP2, but H1 attenuates the nucleosome-stabilizing effect of MeCP2, indicating that the binding pose of MeCP2 in the ternary complex is distinct from that in the MeCP2–nucleosome binary complex. Further studies will be required to test this hypothesis.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Additional data on the interplay between MeCP2 and its binding partners.

a, Representative kymographs of AF488-nucleosome-containing unmethylated DNA tethers bound with Cy5-MeCP2 and Cy3-H1. Arrows denote nucleosome positions. b, Representative kymograph of an unmethylated bare DNA tether bound with LD655-MeCP2 and Cy3-H1 (4 nM each). c, Mass distribution for mononucleosomes containing 207-bp DNA (blue) and for those incubated with Cy3-MeCP2 and H1 (yellow). Peak mass values are indicated. d, Representative kymograph of a nucleosome-containing unmethylated DNA tether bound with Cy5-MeCP2 and Cy3-H1 while being pulled to high forces. e, Representative kymograph of a bare methylated DNA tether incubated with LD655-TBLR1 showing a lack of binding. f, Representative kymograph of a bare unmethylated DNA tether incubated with LD655-TBLR1 and Cy3-MeCP2.

MeCP2 mediates effector recruitment to chromatin

We then sought to investigate the recruiting function of MeCP2 in light of its dynamic behavior on chromatin revealed by the current work. MeCP2 is known to interact with the NCoR1/2 co-repressor complex through its transducin β-like protein 1-related (TBLR1) component22,23,41 and recruit this complex to heterochromatin30. To probe the interplay between MeCP2 and TBLR1 at chromatin, we performed single-molecule experiments to simultaneously visualize LD655-labeled CTD domain of TBLR1 and Cy3-MeCP2 on bare and nucleosomal DNA tethers. We found that TBLR1 is recruited to bare methylated DNA in a strictly MeCP2-dependent manner: long-lived and static TBLR1 trajectories were observed on methylated DNA tethers and always colocalized with MeCP2 trajectories (Fig. 6a,c), whereas no TBLR1 signal was detected in the absence of MeCP2 (Extended Data Fig. 7e). TBLR1 can be recruited by MeCP2 to bare unmethylated DNA too but at a much lower frequency compared with methylated DNA (Fig. 6b,c and Extended Data Fig. 7f). TBLR1 also exhibited a higher mobility along with MeCP2 on unmethylated DNA, implicating MeCP2’s diffusive property in its recruiting function. Next, we examined TBLR1 binding to nucleosomal DNA. We found that, although TBLR1 alone readily bound nucleosomes (Fig. 6d), as expected on the basis of previous reports42,43, MeCP2 significantly increased the frequency of TBLR1 recruitment to nucleosome loci (Fig. 6e,f). Finally, we showed that the RTT mutation R306C dramatically reduced the ability of MeCP2 to recruit TBLR1 to DNA as well as to nucleosomes (Fig. 6c,f), consistent with previous studies showing the importance of the R306 residue for MeCP2–TBLR1 interaction23,41,44. Together, these results suggest that MeCP2 directs co-repressor recruitment to chromatin through its distinct DNA- and nucleosome-binding modalities.

Fig. 6. MeCP2 mediates effector recruitment to methylated DNA and nucleosomes.

a,b, Representative kymographs of a CpG methylated (a) or unmethylated (b) DNA tether incubated with Cy3-labeled MeCP2 and LD655-labeled TBLR1. c, Loading efficiency for 20 nM LD655-TBLR1 binding in the absence of MeCP2 to unmethylated (n = 6 independent tethers) or methylated (n = 5 independent tethers) DNA, in the presence of 2 nM MeCP2 to unmethylated (n = 9 independent tethers) or methylated (n = 7 independent tethers) DNA, or in the presence of 2 nM MeCP2R306C to unmethylated (n = 7 independent tethers) or methylated (n = 4 independent tethers) DNA. Each dot represents data from one independent tether. The bars represent mean and s.d. d,e, Representative kymographs of an AF488-nucleosome-containing unmethylated DNA tether incubated with LD655-TBLR1 only (d) or with both LD655-TBLR1 and Cy3-MeCP2 (e). Lasers were switched on and off to confirm fluorescence signals from each channel. The arrows denote nucleosome positions. The inset shows a zoom-in view of individual fluorescence channels at a nucleosome site (Nuc.) where TBLR1 (TBL.) and MeCP2 (Mec.) colocalized. f, Fraction of nucleosomes loaded on an unmethylated DNA tether that were colocalized with TBLR1 in the absence (n = 4 independent tethers) or presence of 2 nM MeCP2 (n = 5 independent tethers) or MeCP2R306C (n = 6 independent tethers). Each dot represents data from one independent tether. The bars represent mean and s.d. Significance for c and f was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test for each pair.

Discussion

More than two decades after the discovery that mutations in MeCP2 are the genetic drivers for RTT, the molecular behavior of this unique protein on chromatin remains unclear, which impedes the development of targeted therapy. In this study, we developed a single-molecule platform to visualize the dynamics of purified MeCP2 and its disease mutants on individual bare and nucleosomal DNA substrates. This approach uncovered several features of the MeCP2–chromatin interaction that may underlie the multiplexed functions of MeCP2 in gene regulation and genome organization (Fig. 7).

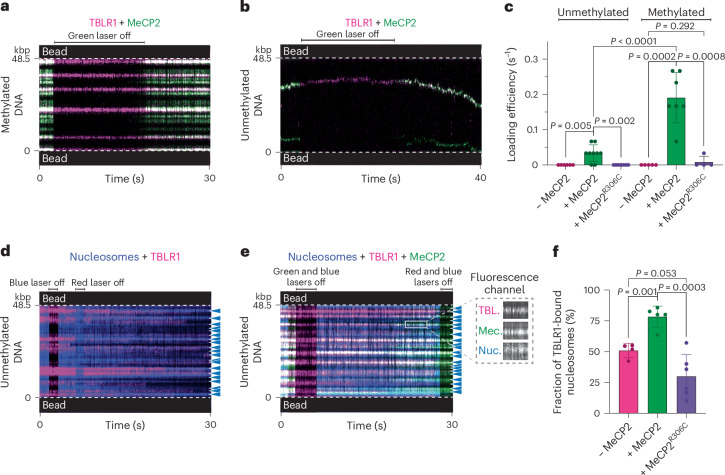

Fig. 7. Working model for normal MeCP2 function on chromatin and its dysregulation in disease.

a, WT MeCP2 rapidly scans unmethylated bare DNA regions, often in oligomeric units, and becomes trapped upon encountering methyl-CpG sites, where it performs methylation-dependent activities such as recruiting transcriptional co-repressors. In contrast, MeCP2 stably engages with nucleosomes and protects them from mechanical perturbation. This interaction also facilitates the recruitment of binding partners of MeCP2 to nucleosome sites. Nucleosomes also serve as molecular sponges that efficiently capture MeCP2, reducing the pool of MeCP2 molecules available to bind bare DNA. b, Aberrant function of RTT-causing MeCP2 mutants can be manifested through diverse mechanisms, including slowed or halted search on bare DNA, reduced binding to methyl-DNA, reduced nucleosome targeting, weakened nucleosome stabilization, impaired effector recruitment and imbalanced chromatin distribution. These abnormal MeCP2 behaviors may contribute to the molecular basis for MeCP2-related disorders such as RTT and MDS.

Diffusion kinetics govern MeCP2’s activity on DNA

Our results reveal that MeCP2 undergoes 1D diffusion when bound to DNA. This property, previously unknown for MeCP2 but reported for other methyl-CpG-binding proteins45, allows the protein to quickly sample many DNA sites without dissociation, which facilitates target search46,47. The high mobility of MeCP2 also helps rationalize the sensitivity of unmethylated DNA to DNase I digestion even when bound to MeCP2 (ref. 48). We further showed that MeCP2 diffusion is much slower on CpG methylated DNA, probably due to a longer residence time on each methyl-DNA site. We speculate that such low mobility stalls MeCP2 and provides ample time for its effector proteins to exert function, thereby achieving its functional specificity despite only a modest difference in its binding affinities to methylated versus unmethylated DNA13. Future investigations will characterize the effect of DNA methylation on MeCP2’s diffusion kinetics in non-CpG contexts such as CAC tri-nucleotides, which the protein also recognizes49,50.

Nucleosomes serve as regulatory hubs for MeCP2

Echoing previous biochemical and genomic results showing that MeCP2 binds nucleosomes15–17, our single-molecule results further reveal that the MeCP2–nucleosome interaction is prevalent and stable, contrasting the protein’s dynamic behavior on bare DNA. We propose that this stable association mediates hitherto underappreciated nucleosome-directed activities of MeCP2 (Fig. 7a). In support of this concept, we demonstrate that MeCP2 binding per se stabilizes nucleosomes against mechanical unwrapping. The forces required to unravel MeCP2-bound nucleosomes measured in our assays exceed the maximal forces generated by the transcription machinery and chromatin remodelers51,52. Thus, the nucleosome-stabilizing effect of MeCP2 is expected to impinge on various processes in gene expression and genome organization. In addition, we found that the co-binding of H1 attenuates this nucleosome-stabilizing effect, suggesting that MeCP2’s mechanical impact on chromatin is subjected to regulation by other chromatin-binding factors.

We also showed that MeCP2 enhances the recruitment of TBLR1 to nucleosomes. This finding is compatible with the previously proposed ‘bridge hypothesis’, which postulates that MeCP2 recruits the co-repressor complex to heterochromatin to execute its role as a global repressor21. Our results add to this model by demonstrating that the recruitment function exploits the differential diffusion kinetics of MeCP2 dependent on the DNA methylation status and nucleosome occupancy. Moreover, our results suggest that nucleosomes serve as ‘molecular sponges’, sequestering MeCP2 away from bare DNA sites. Given that MeCP2 and histones exist in near stoichiometric amounts in neuronal nuclei1, it is plausible that nucleosomes capture the vast majority of MeCP2, leaving only a small pool of free proteins. As such, even a mild decrease or increase in the overall MeCP2 level would drastically affect the protein availability and lead to aberrant downstream functions, thereby explaining MeCP2’s exquisite dosage sensitivity despite its high abundance29,30,53,54. Overall, our study highlights nucleosomes as regulatory hubs for MeCP2’s genomic activities. It will be interesting to investigate how histone posttranslational modifications, such as H3K9 and H3K27 methylation18,55, modulate MeCP2’s behavior at chromatin using our single-molecule platform.

RTT mutations alter aspects of MeCP2 dynamics on chromatin

Our work establishes a biophysical framework to dissect the altered molecular behavior of MeCP2 RTT mutants at the local chromatin level and understand their diverse molecular pathology (Fig. 7b). We observed that the MeCP2T158M mutant displays a modestly reduced level of binding to methylated DNA—as expected—but otherwise near-normal DNA scanning and nucleosome binding activities. This is in accord with an earlier report showing that a main source for T158M pathology is the decreased protein stability in vivo and that increasing protein expression is sufficient to ameliorate RTT-like phenotypes53.

Previous work reported that the P225R substitution moderately reduces the MeCP2 abundance in neurons, causes impaired TBLR1 recruitment to heterochromatin and dampens the methylation-dependent transcriptional repression activity of MeCP2 (ref. 30). In our study, we observed this mutant exhibits reduced binding to methylated DNA but retains the ability to bind nucleosomes, which may explain its weakened but not abolished TBLR1 recruitment and transcriptional repressive activities. Additionally, we found that MeCP2P225R loses the ability to discriminate between unmethylated and CpG methylated DNA in terms of binding and diffusion kinetics, which may result in ectopic activities that are normally restricted to methylated genomic regions.

The MeCP2R270X truncating mutant was shown to exhibit normal genome-wide binding patterns but cause substantial transcriptional dysregulation30,31. We showed that this truncation indeed retains both DNA-binding and nucleosome-binding capacities. We further found a reduced nucleosome-stabilizing activity in this mutant, in accord with its deficiency in compacting nucleosome arrays as reported previously30,31. Moreover, we identified the region between K210 and R270 to be essential for MeCP2’s ability to bind nucleosomes but not for its ability to bind DNA. Therefore, RTT truncating mutations in this region (for example, R255X) may cause an imbalanced MeCP2 distribution between DNA and nucleosomes and, consequently, aberrant function. These insights will potentially inform targeted intervention strategies to restore the normal activities of MeCP2 at chromatin in specific disease contexts.

Besides providing molecular insights into MeCP2 and RTT biology, this work highlights the central role of nucleosomes in modulating the distribution and dynamics of chromatin regulators56. It is worth noting that, for technical reasons, the nucleosome density and protein concentrations were used in our experiments at lower than physiological levels. It is therefore desirable to further develop the single-molecule platform to allow observation and manipulation of chromatin complexes in a native-like environment.

Methods

Protein purification and labeling

MeCP2

Human MeCP2 in the pTXB1 plasmid (Addgene #48091) was propagated in Escherichia coli 5-alpha cells (New England BioLabs). Following mutagenesis for fluorescent labeling and/or creating RTT mutations using the Q5 mutagenesis kit (New England BioLabs), plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Thermo Fisher) for overexpression. Expression and purification of MeCP2 started with chitin–intein MeCP2 fusion proteins. The protocol was adapted from a previously published protocol57 and the manufacturer’s instructions for the IMPACT system (New England BioLabs). Four liters of cells in the presence of 100 μg ml−1 carbenicillin were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside overnight at 16 °C. Lysates were prepared by resuspending cell pellets in column buffer (20 mM Tris hydrochloride pH 8.0, 500 mM sodium chloride, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (GoldBio)) followed by sonication and centrifugation at 23,700g for 30 min. Lysates were applied to a 10 ml bed volume of chitin resin (New England BioLabs) that was preequilibrated with column buffer for 1.5 h at 4 °C on a tube rotator. The resin was washed with 20× resin bed volumes of column buffer and then flushed with 3× resin bed volumes of column buffer supplemented with 50 mM dithiothreitol before being capped and left overnight at room temperature for intein cleavage. Fractions were eluted with column buffer and analyzed by SDS–PAGE, and peak fractions were pooled, concentrated and added to a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated with column buffer attached to an AKTA pure system (Cytiva) for gel filtration. Peak fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and aliquoted for fluorescent labeling or flash frozen and stored in −80 °C.

To obtain full-length MeCP2 site-specifically labeled with a Cy3 or Cy5 fluorophore, two out of three native cysteine residues were mutated to serine (C339S and C413S), leaving a single cysteine residue (C429) located near the end of the disordered CTD. None of the labeling positions used has been implicated in RTT. MeCP2C339S,C413S (referred to as MeCP2 in this study) was expressed and purified as described above and subsequently incubated with 3× molar excess of Tris carboxy ethyl phosphene at 4 °C for 30 min. Cy3- or Cy5-maleimide dye (Cytiva) was added at a 20:1 molar ratio of dye to MeCP2 and incubated at 4 °C overnight in the dark. To remove free dye, labeled protein was dialyzed in 3× 1-liter column buffer and subsequently analyzed by SDS–PAGE, concentrated, aliquoted, flash frozen and stored in −80 °C. A similar protocol was performed to fluorescently label MeCP2 mutants, several of which contain different labeling positions to accommodate for truncating mutations: Cy3-C429 T158M MeCP2, Cy3-C429 P225R MeCP2, Cy3-S242C R270X MeCP2, Cy3-S194C K210X MeCP2 and Cy3-S13C R162X MeCP2. The labeling efficiencies for these MeCP2 constructs range from 80% to 100%.

Histone octamers

Recombinant human core histones were purified and labeled with an LD655 or AF488 fluorophore as previously described58. Briefly, core histones were individually expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells, extracted from inclusion bodies and purified under denaturing conditions using Q and SP ion exchange columns (GE Healthcare). H4L50C was labeled with LD655-maleimide (Lumidyne Technologies) under denaturing conditions. Octamers were reconstituted by adding equal molar amounts of each core histone (LD655-H4L50C, H3.2, H2A and H2B) and purified by gel filtration as described previously. The same protocol was performed to obtain histone octamers containing AF488-H2AK12C.

TBLR1

Recombinant human TBLR1CTD (residues 134–514) was inserted into a pCAG-TEV-3C plasmid, and the GFP fusion protein was expressed in 400 ml of suspension HEK293 cells. Cell pellet was lysed in 20 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris hydrochloride pH 8.0, 300 mM sodium chloride, 3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.2% NP40, 1 mg ml−1 aprotinin, 1 mg ml−1 leupeptin, 1 mg ml−1 pepstatin A, 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM ATP and 2 mM magnesium chloride) with the addition of 1 µl Benzonase (Millipore Sigma) by vortexing. The solution was nutated on a rotating nutator at 4 °C for 20 min and centrifuged at 48,300g for 30 min at 4 °C. The lysate was collected, added to 1 ml of GFP nanobody-coated agarose bead slurry that was preequilibrated with wash buffer (50 mM Tris hydrochloride pH 8.0, 300 mM sodium chloride and 3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and nutated on a rotating nutator at 4 °C for 1.5 h. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000g for 2 min, and the supernatant was removed. The beads were washed 3× with 1 ml wash buffer to remove detergent and protease inhibitors. The beads were resuspended in 250 µl wash buffer, and 250 µl of 3C protease was added. The bead solution was nutated at 4 °C in the rotating nutator overnight. Beads were then pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000g for 2 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. This step was repeated 3× after the addition of wash buffer to collect 5 ml of supernatant in total. The eluted protein was then concentrated and added to a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated with wash buffer attached to an AKTA pure system (Cytiva) for gel filtration. Peak fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and aliquoted for fluorescent labeling.

To attach a fluorophore to the N terminus of TBLR1CTD, the purified protein was dialyzed in 3× 1 liter of labeling buffer (45 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 200 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 0.25 mM EDTA) and LD655-NHS dye (Lumidyne Technologies) was added at a 5:1 molar ratio of dye to TBLR1CTD. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h in the dark, and the reaction was quenched by adding 30 mM Tris hydrochloride pH 7.0 for 5 min at room temperature. To remove free dye, labeled protein was dialyzed in 3× 1 liter of storage buffer (45 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 200 mM sodium chloride and 1 mM dithiothreitol) and subsequently analyzed by SDS–PAGE, concentrated, aliquoted, flash frozen and stored in −80 °C. The final labeling efficiency was estimated to be ~85%.

Recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae Nap1 was expressed and purified as previously described34. Recombinant linker histone H1.4A4C was purified and labeled with a Cy3 fluorophore as previously described59.

DNA substrate preparation

Biotinylated λ DNA

To generate terminally biotinylated double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), the 12-base overhang on each end of the bacteriophage λ genomic DNA from Dam and Dcm methylation-free E. coli (48,502 bp; Thermo Fisher) was filled in with a mixture of unmodified and biotinylated nucleotides by the exonuclease-deficient DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment (New England BioLabs). The reaction was performed by incubating 17 µg of λ DNA (dam-, dcm-), 32 µM each of dGTP/biotin-14-dATP/biotin-11-dUTP/biotin-14-dCTP (Thermo Fisher) and 5 U of Klenow in 1× NEBuffer 2 (New England BioLabs) (120 µl total volume) at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 mM EDTA and heat inactivated at 75 °C for 20 min. Biotinylated DNA was then ethanol precipitated for at least 1 h at −20 °C in 3× volume ice-cold ethanol and 300 mM sodium acetate pH 5.2. Precipitated DNA was recovered by centrifugation at 13,500g for 30 min at 4 °C. After removing the supernatant, the pellet was washed twice with 1 ml of 70% ethanol, each round followed by centrifugation at 13,500g for 1 min at 4 °C and removal of the supernatant. The resulting pellet was air dried, resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and 1 mM EDTA) and stored at 4 °C.

CpG methylated λ DNA

To generate CpG methylated DNA, 500 ng of biotinylated λ DNA was incubated at 37 °C with 1.6 M of S-adenosylmethionine (New England BioLabs) and 20 U of CpG methyltransferase M.SssI (New England BioLabs) (20 µl total volume) overnight. The reaction was stopped by heat inactivation at 65 °C for 20 min. The DNA was then isolated by phenol–chloroform extraction by raising the volume to 250 µl, adding an equal volume of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v) and inverting the tube vigorously to mix. The mixture was centrifuged at 13,500g for 5 min at room temperature and the supernatant was collected. The process was repeated using the supernatant. The DNA was then purified by ethanol precipitation, resuspended in TE buffer and stored at 4 °C. Methylation efficiency was assessed by incubating the methylated DNA with CpG methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme BstUI (New England BioLabs), which is unable to perform digestion in the presence of methylation at its cut site (157 predicted sites on λ DNA).

Single-molecule experiments

Experimental setup

Single-molecule experiments were performed at room temperature on a LUMICKS C-Trap instrument, which combines three-color confocal fluorescence microscopy with dual-trap optical tweezers28. Data were acquired using LUMICKS Bluelake software version 1.6.16. Rapid optical trap movement was enabled by a computer-controlled stage within a five-channel flow cell (Fig. 1a). Channels 1–3 were separated by laminar flow, which were used to form DNA tethers between two 3 µm streptavidin-coated polystyrene beads (Spherotech) held in optical traps. Under a constant flow, a single bead was caught in each trap in channel 1. The traps were then moved to channel 2, and biotinylated DNA was caught between both traps as detected by an increase in the force reading. Flow was stopped, and the traps were moved to channel 3 containing only buffer where the presence of a single DNA tether was confirmed by the force–distance curve. Channels 4 and 5 were loaded with proteins as described for each assay. Flow was turned off during data acquisition and visualization of protein behavior.

Fluorescence detection

Cy3, LD655 (or Cy5) and AF488 fluorophores were excited by three laser lines at 532, 638 and 488 nm respectively. Kymographs were generated by confocal line scanning through the center of the two beads at 100 ms per line. Individual lasers were occasionally turned off to confirm the presence of other fluorophore-labeled proteins. To investigate the behavior of Cy3-MeCP2 on DNA, optical traps tethering a λ DNA molecule under 1 pN of constant tension were moved into channel 4 of the microfluidic flow cell containing 2 nM of Cy3-MeCP2 (unless specified otherwise) in an imaging buffer containing 20 mM Tris hydrochloride pH 8.0 and 100 mM sodium chloride. Following 30 s incubation, the tether was moved to channel 3 containing buffer only for removal of nonspecific binding events and imaging.

To generate nucleosome-containing DNA tethers, optical traps tethering a λ DNA molecule under 1 pN of constant tension were moved into channel 4 of the microfluidic flow cell containing 2 nM LD655-histone octamers and 2 nM Nap1 in 1× HR buffer (30 mM Tris acetate pH 7.5, 20 mM magnesium acetate, 50 mM potassium chloride and 0.1 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin). Following a 3 s incubation (both octamer concentration and incubation time were optimized to form three to ten nucleosomes on each DNA tether), tethers were moved to channel 3 containing 0.25 mg ml−1 sheared salmon sperm DNA in 1× HR buffer for removal of nonspecific octamer binding. Formation of properly wrapped nucleosomes was confirmed by pulling the tether to generate force–distance curves showing force-induced transitions of expected distance change occurring at expected force regime60. To investigate the behavior of Cy3-MeCP2 on this substrate, a nucleosome-containing DNA tether was moved to channel 5 containing 2 nM of Cy3-MeCP2 (unless specified otherwise) in imaging buffer. Following a 30 s incubation, the tether was moved to channel 3 for imaging.

To investigate the interplay between MeCP2 and H1, AF488-nucleosome-containing DNA tethers were moved to channel 5 containing 2 nM of LD655-MeCP2 and 10 nM of Cy3-H1 in imaging buffer. Following a 30 s incubation, tethers were moved to channel 3 for imaging. The same protocol was used to investigate the interplay between MeCP2 and TBLR1, except that 2 nM of Cy3-MeCP2 and 20 nM of LD655-TBLR1CTD were used.

Force manipulation

Nucleosomal DNA tethers (unbound or bound with MeCP2/H1 proteins) were first relaxed by lowering the distance between traps in channel 3 until ~0.25 pN of force was reached. The force was zeroed, and the tether was subjected to pulling by moving one trap relative to the other at a constant velocity of 0.1 µm s−1 until the DNA entered the overstretching regime (~65 pN) or the tether broke.

Data analysis

Kymographs were processed and analyzed using a custom script (https://harbor.lumicks.com/single-script/c5b103a4-0804-4b06-95d3-20a08d65768f) that incorporates tools from the lumicks.pylake Python library and other Python modules (Numpy, Matplotlib and Pandas) to generate tracked lines using the kymotracker greedy algorithm. To determine the MSD, the tracked lines were smoothed using a third-order Savitzky–Golay filter with a window length of 11 tracked frames, and the MSD was calculated from each smoothed trajectory. The diffusion coefficient (D) was calculated by fitting the MSD curve for each trajectory to the equation for 1D diffusion where (α is the exponential term used to characterize normal diffusion (), subdiffusion () or superdiffusion ()). The first 1.5 s segment of each MSD curve was used for the fit61. The fit was discarded if the value of the fit was less than 0.8. Trajectories with an α value between 0.7 and 1.3 (over 50% of all trajectories) were included for further analysis. The estimated number of molecules per trajectory was determined by dividing the photon count for each trajectory averaged over a 30 s time window by the photon count for a single Cy3-MeCP2 under the same imaging condition. The loading efficiency of MeCP2 or TBLR1 on DNA was determined per tether by dividing the number of fluorescent trajectories by the incubation time (30 s) in the protein channel (channel 4). Only stably bound proteins were considered, defined as those that survived dragging from channel 4 to channel 5 and lasted longer than 30 s in the protein-free channel (channel 5).

Force–distance curves obtained from pulling experiments were analyzed by extracting the distance change (ΔL) and the transition force of abrupt rips associated with individual nucleosome unwrapping events. Only rips occurring above 8 pN were analyzed, which correspond to unwrapping of the inner DNA turn of the nucleosome60.

nMS analysis

Mononucleosomes used for nMS were assembled by salt gradient dialysis using unlabeled WT human histone octamers as previously described62. Two micromolar of the reconstituted nucleosome was mixed with MeCP2 at varying molar ratios and then buffer-exchanged into nMS solution (150 mM ammonium acetate pH 7.5 and 0.01% Tween-20) using Zeba desalting microspin columns with a 40 kDa molecular weight cutoff (Thermo Scientific). Each nMS sample was loaded into a gold-coated quartz capillary tip that was prepared in-house and was electrosprayed into an Exactive Plus Extended Mass Range (EMR) instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a modified static nanospray source63. The mass spectrometry parameters used included the following: spray voltage, 1.22 kV; capillary temperature, 150 °C; S-lens RF level, 200; resolving power, 8,750 at m/z of 200; AGC target, 1 × 106; number of microscans, 5; maximum injection time, 200 ms; in-source dissociation, 0–10 V; injection flatapole, 8 V; interflatapole, 4 V; bent flatapole, 4 V; high-energy collision dissociation, 150–180 V; ultrahigh vacuum pressure, 5 × 10−10 mbar; total number of scans, 100. Mass calibration in positive EMR mode was performed using cesium iodide. Raw nMS spectra were visualized using Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser (version 4.2.47). Data processing and spectra deconvolution were performed using UniDec version 4.2.0 (refs. 64,65).

nMS analysis of the four individual histone proteins and MeCP2 confirmed their primary sequences and revealed that these proteins had undergone canonical N-terminal processing (removal of N-terminal methionine). In addition, unbound bacterial DnaK was observed in the MeCP2 sample. Overall, the following expected masses based on the sequence after N-terminal processing were used for the component proteins: H2A, 13,974.3 Da; H2B, 13,758.9 Da; H3.2, 15,256.8 Da; H4, 11,236.1 Da; MeCP2, 52,309.4 Da. Based on its sequence, the mass of the 207 bp dsDNA used was 127,801.8 Da. For the reconstituted nucleosome sample, we obtained one predominant peak series corresponding to the fully assembled nucleosome (histone octamer + dsDNA) with a measured mass of 236,277 Da (mass accuracy of 0.01%).

MP

Data were collected using a OneMP mass photometer (Refeyn) that was calibrated with bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), β-amylase (224 kDa) and thyroglobulin (670 kDa). Movies were acquired for 6,000 frames (60 s) using AcquireMP software (version 2.4.0) and default settings. Final protein concentrations were empirically determined to achieve ∼75 binding events per second. Peak mass values are predicted to fall within ~5% error. Raw data were converted to frequency distributions using Prism 9 (GraphPad) and a bin size of 5 or 10 kDa.

EMSA

In a buffer containing 20 mM Tris hydrochloride pH 8.0 and 100 mM sodium chloride in a total volume of 20 µl, 147 bp or 207 bp unmethylated or CpG methylated DNA or mononucleosome wrapped with 207 bp unmethylated DNA at described concentrations was incubated with an indicated molar ratio of MeCP2 at room temperature for 10 min. Then, 3.6 µl of 2 M sucrose was added and 15 µl of each sample was run on a 6% native PAGE gel at 110 V for 70 min (for DNA sample) or 90 min (for nucleosome sample). The DNA was stained with SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Thermo Fisher) and visualized using a gel imager (Axygen).

Statistical analysis

The errors reported in this study represent s.d. or s.e.m. P values were determined from two-tailed unpaired t-tests (with Welch’s correction as specified in each figure caption) for comparison between two conditions and determined from one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s tests for comparison between multiple conditions using Prism 10 (GraphPad).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41594-024-01373-9.

Supplementary information

Source data

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unmodified gels.

Statistical source data.

Unmodified gels.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unmodified gels.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Arimura, H. Funabiki and V. Risca (Rockefeller University) for their advice on the project, R. Gong, D. Phua and G. Alushin (Rockefeller University) for help with TBLR1 purification, Y. David and A. Osunsade (Sloan Kettering Institute) for providing purified H1 and T. Kapoor (Rockefeller University) for providing access to the MP instrument. G.N.L.C. acknowledges support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number F31MH132306. J.W.W. is supported by an NRSA Training Grant from the NIH (T32GM066699). L.E.V. is supported by a Chemistry-Biology Interface Training Grant to the Tri-Institutional PhD Program in Chemical Biology (NIH T32 GM115327 and GM136640). B.T.C. acknowledges support from the NIH under award numbers P41GM109824 and P41GM103314. S.L. is supported by an Innovation Award from the International Rett Syndrome Foundation, the Robertson Foundation, the Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance, a Starr Cancer Consortium grant and the NIH (DP2HG010510 and R01GM149862). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Extended data

Author contributions

G.N.L.C. conceived the project, prepared the reagents and performed the single-molecule and bulk experiments. M.B. and J.A.L. assisted with the preparation of RTT mutant proteins and single-molecule experiments. J.W.W. wrote the scripts for and assisted with single-molecule data analysis. P.D.B.O. and B.T.C. performed the nMS experiments. L.E.V. performed the MP experiments. S.L. oversaw the project. G.N.L.C. and S.L. wrote the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology thanks Karl Duderstadt and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. Primary Handling Editors: Carolina Perdigoto, Jean Nakhle and Dimitris Typas, in collaboration with the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology team.

Data availability

All kymographs used for analysis have been deposited as datasets in Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.11557684; 10.5281/zenodo.11558336; 10.5281/zenodo.11559182)66–68. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Kymographs were processed and analyzed using a custom script that can be accessed on LUMICKS Harbor (https://harbor.lumicks.com/single-script/c5b103a4-0804-4b06-95d3-20a08d65768f).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41594-024-01373-9.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41594-024-01373-9.

References

- 1.Skene, P. J. et al. Neuronal MeCP2 is expressed at near histone-octamer levels and globally alters the chromatin state. Mol. Cell37, 457–468 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis, J. D. et al. Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to methylated DNA. Cell69, 905–914 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nan, X., Campoy, F. J. & Bird, A. MeCP2 is a transcriptional repressor with abundant binding sites in genomic chromatin. Cell88, 471–481 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amir, R. E. et al. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet.23, 185–188 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Percy, A. K. Rett syndrome. Current status and new vistas. Neurol. Clin.20, 1125–1141 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagberg, B. Rett’s syndrome: prevalence and impact on progressive severe mental retardation in girls. Acta Paediatr. Scand.74, 405–408 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Esch, H. MECP2 duplication syndrome. Mol. Syndromol.2, 128–136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubs, H. et al. XLMR syndrome characterized by multiple respiratory infections, hypertelorism, severe CNS deterioration and early death localizes to distal Xq28. Am. J. Med. Genet.85, 243–248 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moretti, P. & Zoghbi, H. Y. MeCP2 dysfunction in Rett syndrome and related disorders. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev.16, 276–281 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandweiss, A. J., Brandt, V. L. & Zoghbi, H. Y. Advances in understanding of Rett syndrome and MECP2 duplication syndrome: prospects for future therapies. Lancet Neurol.19, 689–698 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo, J. U. et al. Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat. Neurosci.17, 215–222 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabel, H. W. et al. Disruption of DNA-methylation-dependent long gene repression in Rett syndrome. Nature522, 89–93 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraga, M. F. et al. The affinity of different MBD proteins for a specific methylated locus depends on their intrinsic binding properties. Nucleic Acids Res.31, 1765–1774 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosh, R. P., Horowitz-Scherer, R. A., Nikitina, T., Shlyakhtenko, L. S. & Woodcock, C. L. MeCP2 binds cooperatively to its substrate and competes with histone H1 for chromatin binding sites. Mol. Cell. Biol.30, 4656–4670 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgel, P. T. et al. Chromatin compaction by human MeCP2. Assembly of novel secondary chromatin structures in the absence of DNA methylation. J. Biol. Chem.278, 32181–32188 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikitina, T. et al. MeCP2–chromatin interactions include the formation of chromatosome-like structures and are altered in mutations causing Rett syndrome. J. Biol. Chem.282, 28237–28245 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikitina, T. et al. Multiple modes of interaction between the methylated DNA binding protein MeCP2 and chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol.27, 864–877 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, W., Kim, J., Yun, J. M., Ohn, T. & Gong, Q. MeCP2 regulates gene expression through recognition of H3K27me3. Nat. Commun.11, 3140 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang, L. et al. Rett syndrome-causing mutations compromise MeCP2-mediated liquid-liquid phase separation of chromatin. Cell Res30, 393–407 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, C. H. et al. MeCP2 links heterochromatin condensates and neurodevelopmental disease. Nature586, 440–444 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tillotson, R. & Bird, A. The molecular basis of MeCP2 function in the brain. J. Mol. Biol.432, 1602–1623 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokura, K. et al. The Ski protein family is required for MeCP2-mediated transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem.276, 34115–34121 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyst, M. J. et al. Rett syndrome mutations abolish the interaction of MeCP2 with the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor. Nat. Neurosci.16, 898–902 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao, Y. et al. Identification and characterization of conserved noncoding cis-regulatory elements that impact Mecp2 expression and neurological functions. Genes Dev.35, 489–494 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piccolo, F. M. et al. MeCP2 nuclear dynamics in live neurons results from low and high affinity chromatin interactions. eLife8, e51449 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chua, G. N. L. & Liu, S. When force met fluorescence: single-molecule manipulation and visualization of protein–DNA interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys.53, 169–191 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasserman, M. R., Schauer, G. D., O’Donnell, M. E. & Liu, S. Replication fork activation is enabled by a single-stranded DNA gate in CMG helicase. Cell178, 600–611.e16 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Hashemi Shabestari, M., Meijering, A. E. C., Roos, W. H., Wuite, G. J. L. & Peterman, E. J. G. Recent advances in biological single-molecule applications of optical tweezers and fluorescence microscopy. Methods Enzymol.582, 85–119 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown, K. et al. The molecular basis of variable phenotypic severity among common missense mutations causing Rett syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet25, 558–570 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guy, J. et al. A mutation-led search for novel functional domains in MeCP2. Hum. Mol. Genet27, 2531–2545 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker, S. A. et al. An AT-hook domain in MeCP2 determines the clinical course of Rett syndrome and related disorders. Cell152, 984–996 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neul, J. L. et al. Specific mutations in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 confer different severity in Rett syndrome. Neurology70, 1313–1321 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, Y., Kucukkal, T. G., Li, J., Alexov, E. & Cao, W. Binding analysis of methyl-CpG binding domain of MeCP2 and Rett syndrome mutations. ACS Chem. Biol.11, 2706–2715 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, S. et al. Nucleosome-directed replication origin licensing independent of a consensus DNA sequence. Nat. Commun.13, 4947 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carcamo, C. C. et al. ATP binding facilitates target search of SWR1 chromatin remodeler by promoting one-dimensional diffusion on DNA. eLife11, e77352 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodges, C., Bintu, L., Lubkowska, L., Kashlev, M. & Bustamante, C. Nucleosomal fluctuations govern the transcription dynamics of RNA polymerase II. Science325, 626–628 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kujirai, T. et al. Structural basis of the nucleosome transition during RNA polymerase II passage. Science362, 595–598 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz-Celis, C. et al. Assignment of structural transitions during mechanical unwrapping of nucleosomes and their disassembly products. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA119, e2206513119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fyodorov, D. V., Zhou, B. R., Skoultchi, A. I. & Bai, Y. Emerging roles of linker histones in regulating chromatin structure and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.19, 192–206 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito-Ishida, A. et al. Genome-wide distribution of linker histone H1.0 is independent of MeCP2. Nat. Neurosci.21, 794–798 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruusvee, V. et al. Structure of the MeCP2–TBLR1 complex reveals a molecular basis for Rett syndrome and related disorders. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA114, E3243–E3250 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon, H. G. et al. Purification and functional characterization of the human N–CoR complex: the roles of HDAC3, TBL1 and TBLR1. EMBO J.22, 1336–1346 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoon, H. G., Choi, Y., Cole, P. A. & Wong, J. Reading and function of a histone code involved in targeting corepressor complexes for repression. Mol. Cell. Biol.25, 324–335 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heckman, L. D., Chahrour, M. H. & Zoghbi, H. Y. Rett-causing mutations reveal two domains critical for MeCP2 function and for toxicity in MECP2 duplication syndrome mice. eLife3, e02676 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leighton, G. O. et al. Densely methylated DNA traps methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 2 but permits free diffusion by methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 3. J. Biol. Chem.298, 102428 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Hippel, P. H. & Berg, O. G. Facilitated target location in biological systems. J. Biol. Chem.264, 675–678 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halford, S. E. & Marko, J. F. How do site-specific DNA-binding proteins find their targets? Nucleic Acids Res.32, 3040–3052 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nan, X., Meehan, R. R. & Bird, A. Dissection of the methyl-CpG binding domain from the chromosomal protein MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res.21, 4886–4892 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagger, S. et al. MeCP2 recognizes cytosine methylated tri-nucleotide and di-nucleotide sequences to tune transcription in the mammalian brain. PLoS Genet.13, e1006793 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sperlazza, M. J., Bilinovich, S. M., Sinanan, L. M., Javier, F. R. & Williams, D. C. Jr. Structural basis of MeCP2 distribution on non-CpG methylated and hydroxymethylated DNA. J. Mol. Biol.429, 1581–1594 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galburt, E. A. et al. Backtracking determines the force sensitivity of RNAP II in a factor-dependent manner. Nature446, 820–823 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sirinakis, G. et al. The RSC chromatin remodelling ATPase translocates DNA with high force and small step size. EMBO J.30, 2364–2372 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lamonica, J. M. et al. Elevating expression of MeCP2 T158M rescues DNA binding and Rett syndrome-like phenotypes. J. Clin. Invest.127, 1889–1904 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sztainberg, Y. et al. Reversal of phenotypes in MECP2 duplication mice using genetic rescue or antisense oligonucleotides. Nature528, 123–126 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fuks, F. et al. The methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 links DNA methylation to histone methylation. J. Biol. Chem.278, 4035–4040 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou, K., Gaullier, G. & Luger, K. Nucleosome structure and dynamics are coming of age. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.26, 3–13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yusufzai, T. M. & Wolffe, A. P. Functional consequences of Rett syndrome mutations on human MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 4172–4179 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li, S., Zheng, E. B., Zhao, L. & Liu, S. Nonreciprocal and conditional cooperativity directs the pioneer activity of pluripotency transcription factors. Cell Rep.28, 2689–2703.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leicher, R. et al. Single-stranded nucleic acid binding and coacervation by linker histone H1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.29, 463–471 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brower-Toland, B. D. et al. Mechanical disruption of individual nucleosomes reveals a reversible multistage release of DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA99, 1960–1965 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Codling, E. A., Plank, M. J. & Benhamou, S. Random walk models in biology. J. R. Soc. Interface5, 813–834 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee, K. M. & Narlikar, G. Assembly of nucleosomal templates by salt dialysis. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol.10.1002/0471142727.mb2106s54 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Olinares, P. D. B. & Chait, B. T. Native mass spectrometry analysis of affinity-captured endogenous yeast RNA exosome complexes. Methods Mol. Biol.2062, 357–382 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marty, M. T. et al. Bayesian deconvolution of mass and ion mobility spectra: from binary interactions to polydisperse ensembles. Anal. Chem.87, 4370–4376 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reid, D. J. et al. MetaUniDec: high-throughput deconvolution of native mass spectra. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom.30, 118–127 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chua et al. Kymographs of MeCP2 on DNA. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.11557684 (2024).

- 67.Chua et al. Kymographs of MeCP2 on nucleosomes. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.11558336 (2024).

- 68.Chua et al. Kymographs of MeCP2 & TBLR1 on chromatin. Zenodo10.5281/zenodo.11559182 (2024).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unmodified gels.

Statistical source data.

Unmodified gels.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Unmodified gels.

Statistical source data.

Statistical source data.

Data Availability Statement

All kymographs used for analysis have been deposited as datasets in Zenodo (10.5281/zenodo.11557684; 10.5281/zenodo.11558336; 10.5281/zenodo.11559182)66–68. Source data are provided with this paper.

Kymographs were processed and analyzed using a custom script that can be accessed on LUMICKS Harbor (https://harbor.lumicks.com/single-script/c5b103a4-0804-4b06-95d3-20a08d65768f).