Abstract

The WHO Classification of Tumours (WCT) guides cancer diagnosis, treatment, and research. However, research evidence in pathology continuously changes, and new evidence emerges. Correct assessment of evidence in the WCT 5th edition (WCT-5) and identification of high level of evidence (LOE) studies based on study design are needed to improve future editions. We aimed at producing exploratory evidence maps for WCT-5 Thoracic Tumours, specifically lung and thymus tumors. We extracted citations from WCT-5, and imported and coded them in EPPI-Reviewer. The maps were plotted using EPPI-Mapper. Maps displayed tumor types (columns), descriptors (rows), and LOE (bubbles using a four-color code). We included 1434 studies addressing 51 lung, and 677 studies addressing 25 thymus tumor types from WCT-5 thoracic tumours volume. Overall, 87.7% (n = 1257) and 80.8% (n = 547) references were low, and 4.1% (n = 59) and 2.2% (n = 15) high LOE for lung and thymus tumors, respectively. Invasive non-mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung (n = 215; 15.0%) and squamous cell carcinoma of the thymus (n = 93; 13.7%) presented the highest number of references. High LOE was observed for colloid adenocarcinoma of the lung (n = 11; 18.2%) and type AB thymoma (n = 4; 1.4%). Tumor descriptors with the highest number of citations were prognosis and prediction (n = 273; 19.0%) for lung, and epidemiology (n = 186; 28.0%) for thymus tumors. LOE was generally low for lung and thymus tumors. This study represents an initial step in the WCT Evidence Gap Map (WCT-EVI-MAP) project for mapping references in WCT-5 for all tumor types to inform future WCT editions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00428-024-03886-6.

Keywords: Evidence maps, WHO tumor classification, Level of evidence, Cancer research

Introduction

One of the key requirements for accurate cancer diagnosis is the availability of a comprehensive classification of different tumor types. The World Health Organization (WHO) therefore regularly updates WHO Classification of Tumours (WCT), produced as a website and as the WHO Blue Books. These are essential resources for pathologists and researchers among many other specialists worldwide. The WCT is based on multidimensional criteria, including clinicopathological features; these criteria are described for each tumor type, and essential and desirable criteria are listed to make reliable tumor diagnoses [1, 2].

Tumor classification has seen and is expected to see more major changes in the recent decades due to increased understanding resulting from the application of new technologies, e.g., large-scale molecular profiling of tumor DNA or artificial intelligence and digital pathology [3–7]. Likewise, new technologies in the field of cancer research are emerging, thus highlighting the importance to approach the classification of tumors from multiple dimensions [3–5].

Given the emergence of new techniques, as well as the heterogeneity of biomedical and cancer research, the quality and level of evidence (LOE) for the study designs of citations in the WCT often vary significantly [8]. Additional reasons are the rarity of some tumor types that are covered in the WCT and the lack of LOE adapted to tumor pathology. The WCT sets the standards for cancer diagnosis and research. Therefore, the WCT is required to follow the principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and aim to synthesize the best available evidence to date. However, identification of the most relevant evidence and assessment of LOE and quality for published data is often difficult. The reasons for this include the high number of existing references and their variable quality. To address and assist in the evaluation of existing evidence, a new technology called the Evidence Gap Map (EGM) has emerged. EGMs synthesize and display available evidence for a given research question and are predominantly used in social sciences and public health [9–11]. No EGMs or evidence maps had been produced to evaluate the cited evidence for tumor classification before, and the WCT EVI MAP project was developed to fill in this gap.

The present study is encompassed within the WCT EVI MAP project, which is funded by the European Commission horizon grant (101057127) and commenced in 2022. This project’s objective is to create living maps of current evidence to identify gaps and pockets of low-level evidence to assist in the production of the WCT next edition [12].

In this study, we have developed evidence maps for the cited references in the WCT 5th edition (WCT-5) for thoracic tumors [1], particularly for lung and thymus tumors, as well as exploring the LOE of the cited studies for different tumor types and tumor descriptors. For this purpose, we used the traditional LOE for assessing the cited evidence, i.e., in accordance with criteria from the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (CEBM) of the University of Oxford [13], available for this purpose during the period of study.

Material and methods

We developed exploratory evidence maps according to our previously published protocol [14] for the cited evidence in the WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, which include tumors of the lung and thymus.

EPPI-Reviewer [15] and EPPI-Mapper [16] had been previously selected to develop the evidence maps. Both are open access software designed for reviews which permit the import of items in different format for coding and graphical interactive EGM production [15, 16].

A list of cited evidence in the lung and thymus tumor chapters for thoracic tumors [1] was exported from the WCT-5 and imported to EPPI-Reviewer. Therefore, no structured literature search was performed since our objective was to map citations in the WCT-5 for these tumors, thus creating evidence maps instead of EGMs. We extracted the references from the database that holds the WCT content at IARC, as PubMed IDs, and imported the text as a list to EPPI-Reviewer. Eligibility was restricted to citation in one of the target chapters. All study designs were included. All articles had an abstract written in English.

We applied predefined coding tool for the study design and tumor descriptors. Coding in EPPI-Reviewer for each chapter was done by a single reviewer and another reviewer reassessed the citation if the study design was unclear. If the study design was not assigned by information displayed in the title and abstract, the full text was accessed and assessed. LOE was assigned for the study designs based on criteria from the CEBM of the University of Oxford [13]. We then imported the data to EPPI-Mapper to generate an interactive evidence map to graphically display the results.

The resulting maps include the following key components: tumor types constituting the columns of the map, categories of tumor descriptors (Supplementary Table 1) constituting the rows, and LOEs (Supplementary Fig. 1) inside the resulting squares as bubbles (segmenting attribute), i.e., encompassing both tumor type and tumor descriptor. If a particular study had been cited more than once for different tumor types and/or tumor descriptors, it was plotted multiple times. The number of references per tumor type and tumor descriptor was reflected in the size of the bubbles, whereas the LOE was represented through a four-color code: low level evidence in red, moderate level in orange, and high level in blue. Uncodable citations as per study design were displayed in blue. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials were considered high; cohort and case control studies moderate; and cross sectional studies, as well as case series and reports and expert opinions and non-systematic reviews were considered low LOE. Only LOE was considered and not the quality of the study or the journal impact factor. In addition, the aim of this study was to map the cited evidence in WCT-5 but not to assess any author bias.

Results

Tumors of the lung

We included 1434 studies cited in the lung chapter of the WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, which addresses 51 unique tumor types.

Overall, 87.7% (n = 1257) references were labelled as low-level evidence, mainly case series, case reports or narrative reviews, whereas 4.4% (n = 63) were moderate-level, 4.1% (n = 59) were high-level, and 3.8% (n = 51) were uncodable (Fig. 1).

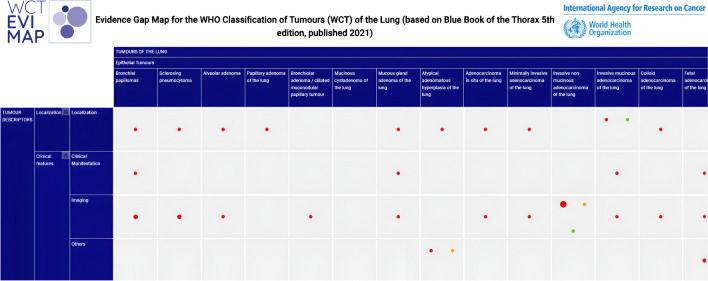

Fig. 1.

Extract of the exploratory evidence map for WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, tumors of the lung chapter (n = 1434)

The complete map can be accessed here.

The number of cited articles greatly varied among different tumor types. Invasive non-mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung chapter had the highest number of citations (n = 215; 15.0%) and, conversely, the highest number of high-level references (n = 25; 11.6%) and the lowest number of low-level cited references (n = 150, 69.8%) among all the chapters. The second chapter in number of cited references was carcinoid/neuroendocrine tumor of the lung (n = 108; 7.5%); however, 92.6% of these were designated as low-level evidence (n = 100). No other chapter contained as many citations as this. We observed that 13.7% (n = 7) of the chapters contained 41 to 72 cited references; 29.4% (n = 15) of the chapters contained 20 to 34 references; and 52.9% (n = 27) of the chapters contained less than 20 cited references, with 33.3% having less than 10 cited references. Only low-level evidence was cited in 45.1% (n = 23) chapters, all corresponding to rare and very rare tumors, while another 94.1% (n = 48) contained more than 85% low-level evidence. The chapters with the highest proportion of high-level references were small cell lung carcinoma of the lung (n = 5; 8.1%) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma of the lung (n = 25; 12.3%) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Number of references per level of evidence and tumor types for WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, tumors of the lung chapter (n = 1434)

By tumor descriptors, some of the 1434 unique citations were cited multiple times. Therefore, we coded 2018 references among the 18 tumor descriptors. Prognosis and Prediction was the heading with the highest number of cited evidence (n = 273; 19,0%), followed by pathogenesis (n = 269; 18,8%) and histopathological general features (n = 206; 14,4%). On the other extreme, grading (n = 7; 0,5%), staging (n = 34; 2,4%) and pattern/subtypes (n = 35; 2,4%) were the categories with the lowest number of citations (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Number of references per level of evidence and tumor descriptor for WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, tumors of the lung chapter (n = 2018)

| Tumor descriptor | Level of evidence | Number of references per tumor descriptor % (n) | Total number of references per tumor descriptor % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical manifestation Clinical manifestation: others |

High | 2.4% (2) | 4.2% (85) |

| Low | 94.1% (80) | ||

| Moderate | 3.5% (3) | ||

| High | 11.1% (4) | 1.8% (36) | |

| Low | 83.3% (30) | ||

| Moderate | 5.6% (2) | ||

| Cytology | Low | 100.0% (73) | 3.6% (73) |

| Diagnostic molecular pathology | High | 1.5% (2) | 6.4% (130) |

| Low | 79.2% (103) | ||

| Moderate | 10.8% (14) | ||

| Uncodable | 8.5% (11) | ||

| Differential diagnosis | High | 0.8% (1) | 6.4% (130) |

| Low | 97.7% (127) | ||

| Uncodable | 1.5% (2) | ||

| Epidemiology | High | 2.4% (4) | 8.4% (169) |

| Low | 94.1% (159) | ||

| Moderate | 3.6% (6) | ||

| Etiology | High | 5.4% (6) | 5.5% (111) |

| Low | 79.3% (88) | ||

| Moderate | 9.0% (10) | ||

| Uncodable | 6.3% (7) | ||

| General features | High | 1.4% (3) | 10.8% (217) |

| Low | 94.9% (206) | ||

| Moderate | 2.8% (6) | ||

| Uncodable | 0.9% (2) | ||

| Grading | High | 14.3% (1) | 0.3% (7) |

| Low | 42.9% (3) | ||

| Moderate | 42.9% (3) | ||

| Histopathology: others | High | 4.0% (2) | 2.5% (50) |

| Low | 86.0% (43) | ||

| Moderate | 4.0% (2) | ||

| Uncodable | 6.0% (3) | ||

| Imaging | High | 4.7% (5) | 5.3% (106) |

| Low | 93.4% (99) | ||

| Moderate | 1.9% (2) | ||

| Immunohistochemistry | Low | 94.1% (143) | 7.5% (152) |

| Moderate | 0.7% (1) | ||

| Uncodable | 5.3% (8) | ||

| Localization | High | 2.6% (2) | 3.8% (76) |

| Low | 96.1% (73) | ||

| Moderate | 1.3% (1) | ||

| Macroscopic appearance | High | 3.1% (2) | 3.2% (65) |

| Low | 96.9% (63) | ||

| Pathogenesis | High | 1.1% (3) | 13.3% (269) |

| Low | 86.6% (233) | ||

| Moderate | 2.6% (7) | ||

| Uncodable | 9.7% (26) | ||

| Patterns/subtypes | High | 8.6% (3) | 1.7% (35) |

| Low | 85.7% (30) | ||

| Moderate | 2.9% (1) | ||

| Uncodable | 2.9% (1) | ||

| Prognosis and prediction | High | 11.7% (32) | 13.5% (273) |

| Low | 81.0% (221) | ||

| Moderate | 7.0% (19) | ||

| Uncodable | 0.4% (1) | ||

| Staging | Low | 97.1% (33) | 1.7% (34) |

| Moderate | 2.9% (1) |

Tumors of the thymus

We included 677 studies cited in the lung chapter of the WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, which addresses 25 unique tumor types.

Overall, 80.8% (n = 547) of references were labelled as low-level evidence, whereas 7.8% (n = 53) were of moderate-level, and 2.2% (n = 15) were coded as high-level evidence, and 7.2% (n = 49) were found to be uncodable (Fig. 3).

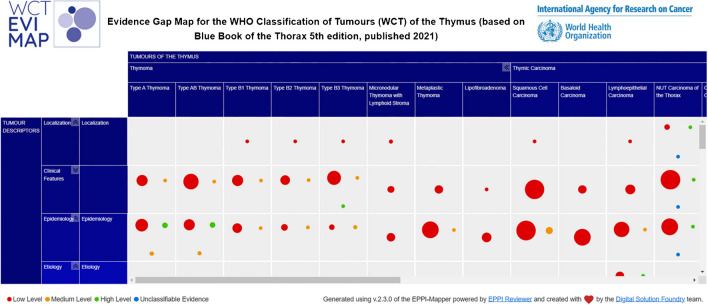

Fig. 3.

Extract of exploratory evidence map for WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, tumors of the thymus chapter (n = 677)

The complete evidence map can be accessed here.

A heterogeneous pattern was found for the number of citations per tumor type. Squamous cell carcinoma yielded the largest number of references (n = 93; 13.7%) but not the largest number of high-level evidence (n = 2; 2.2%). Type B3 thymoma was second in number of references (n = 69; 10.2%). However, the chapters with the lowest level of evidence were metaplastic thymoma (n = 8; 34.8%) and thymic carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS) (n = 5; 38.5%). Nevertheless, these chapters, i.e., metaplastic thymoma and thymic carcinoma NOS also presented the higher number of uncodable studies (n = 14; 60.9% and n = 6; 46.2%, respectively). Other tumor types with low numbers of low LOE studies were the type AB thymoma (n = 25; 71.4%) and small cell carcinoma of the thymus (n = 13; 72.2%). In summary, 24.0% (n = 6) of the chapters cited more than 35 references, specifically between 93 and 44 references, 36.0% (n = 9) 15 to 35 references and 40.0% (n = 10) less than 15 references, specifically 8 to 14 references. Two chapters (8.0%) included only low-level evidence, both corresponding to very rare tumors. The chapters with the highest proportion of high-level references were type AB thymoma (n = 4; 1.4%), thymic carcinoma NOS (n = 1; 7.7%) and type A thymoma (n = 4; 7.7%) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Number of references per level of evidence and tumor types for WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, tumors of the thymus chapter (n = 677)

By tumor descriptor, some of the 677 unique citations were cited multiple times. We coded 1297 references, of which the highest number corresponded to epidemiology (n = 186; 28.0%), prognosis and prediction (n = 184; 27.0%), and pathogenesis (n = 155; 23.3%). On the other extreme, clinical manifestations, other (n = 10; 1.5%), diagnostic molecular pathology (n = 11; 1.7%), and prognosis and prediction (n = 13; 2.0%) presented the lowest number of references (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Number of references per level of evidence and tumor descriptor for WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, tumors of the thymus chapter (n = 1297)

| Tumor descriptor | Level of evidence | Number of references per tumor descriptor % (n) | Total number of references per tumor descriptor % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Clinical manifestation Clinical manifestation: others |

High | 0.8% (1) | 9.9% (129) |

| Low | 93.0% (120) | ||

| Moderate | 6.2% (8) | ||

| High | 10.0% (1) | 0.8% (10) | |

| Low | 90.0% (9) | ||

| Cytology | Low | 100.0% (24) | 1.9% (24) |

| Diagnostic molecular pathology | Low | 90.9% (10) | 0.8% (11) |

| Uncodable | 9.1% (1) | ||

| Differential diagnosis | Low | 94.0% (63) | 5.2% (67) |

| Moderate | 4.5% (3) | ||

| Uncodable | 1.5% (1) | ||

| Epidemiology | High | 4.8% (9) | 14.3% (186) |

| Low | 81.7% (152) | ||

| Moderate | 12.9% (24) | ||

| Uncodable | 0.5% (1) | ||

| Etiology | High | 2.2% (1) | 3.5% (45) |

| Low | 97.8% (44) | ||

| General features | Low | 91.1% (123) | 10.4% (135) |

| Moderate | 8.1% (11) | ||

| Uncodable | 0.7% (1) | ||

| Histopathology: others | Low | 100.0% (1) | 0.1% (1) |

| Imaging | Low | 97.2% (35) | 2.8% (36) |

| Uncodable | 2.8% (1) | ||

| Immunohistochemistry | Low | 95.9% (118) | 9.5% (123) |

| Moderate | 3.3% (4) | ||

| Uncodable | 0.8% (1) | ||

| Localization | High | 5.6% (1) | 1.4% (18) |

| Low | 88. .9% (16) | ||

| Uncodable | 5.6% (1) | ||

| Macroscopic appearance | Low | 91.5% (54) | 4.5% (59) |

| Moderate | 8.5% (5) | ||

| Pathogenesis | High | 1.3% (2) | 12.0% (155) |

| Low | 69.0% (107) | ||

| Moderate | 2.6% (4) | ||

| Uncodable | 27.1% (42) | ||

| Patterns/subtypes | Low | 100.0% (21) | 1.6% (21) |

| Prognosis and prediction | High | 2.2% (4) | 14.2% (184) |

| Moderate | 23.9% (44) | ||

| Low | 67.4% (124) | ||

| Uncodable | 2.7% (5) | ||

| Staging | Low | 67.7% (63) | 7.2% (93) |

| Moderate | 9.7% (9) | ||

| Uncodable | 22.6% (21) |

Discussion

We observed that references cited in the WCT-5 for thoracic tumors, chapters on tumors of the lung and thymus, mostly correspond to a low LOE based on the CEBM LOE and study design. Additionally, the number of cited references was heterogeneously distributed, with some tumor types including hundreds of citations and others less than 10. It is likely that these differences are related to tumor incidence, i.e., the higher the incidence of a specific tumor, the higher the number of published studies addressing it. In line with this, invasive non-mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung, which is a high-incidence lung tumor, had the highest number of citations [17]. This is further supported by the fact that the tumors with the highest proportion of high LOE were high incidence tumors and the tumor types presenting only low LOE evidence were rare and very rare tumors. This could be because achieving higher sample numbers and, thus, performing high LOE studies is difficult for rare tumor entities. However, with regard to tumors presenting a higher incidence, we observed that only 3.5% of all cited evidence addressed squamous cell carcinoma, i.e., variations exist across tumor entities. Another possible explanation is the lack of existing evidence for some neoplasms, mainly for rare tumor types, as well as the inaccessibility of some studies. For example, certain types of lung cancer, such as adenocarcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) present a higher proportion in non-smoking people of East Asian origin in comparison to non-smokers from elsewhere [18–20]. Consequently, research written in a language different than English may be less accessible to the research community and editors of the WCT. Yet another possible explanation is that existing evidence is written by non-pathologists and, therefore, does not use tumor descriptors that appear in the WCT headings for certain tumor types.

In addition, the tumor descriptor sections with the highest number of references overall were Prognosis and Prediction and Pathogenesis. This may be due to research focusing more on these areas, or of greater clinical relevance. Therefore, a focus on improving under-researched or under-cited categories of tumor descriptors and pockets of low LOE may be desirable to inform future WCT editions for thoracic tumors. This is especially important for rare tumors, for which solid evidence is often lacking. This could be achieved through international consortiums/groups focusing on particular rare tumors to achieve higher sample numbers and thus perform higher LOE research. In addition to mapping citations within the WCT, we plan to map all available evidence since 2018, when WCT-5 started publication, using an extensive search strategy for tumor types within the WCT EVI MAP project [12], to identify gaps in published research, both for tumor type and tumor descriptor, as well as pockets of low LOE. Knowing the lack of literature in certain tumor types and descriptors through this project will enable researchers to identify research future research areas to focus on.

For lung tumors, the type with the highest number of references, i.e., invasive non-mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung, also presented the highest number of high LOE. However, we did not observe the same for thymus tumors. We believe it would be interesting to explore the distribution of high LOE references across for other tumors in the WCT [12].

We analyzed the cited evidence in accordance with tumor types and descriptors and LOE as per study designs. However, visualizations of the geographical area in which the studies were performed, and publication date distribution of the selected evidence would help identifying additional gaps and pockets of LOE. Most of the study settings in tumor research are in high-income countries and therefore addressing lung and thymic tumors in people of European origin [21, 22].

Our study has other limitations. Most of the coding of each chapter was done by a single reviewer. However, to overcome this limitation, a second reviewer was employed to solve doubts and disagreements. In addition, an assessment of the risk of bias or overall methodological quality of the selected studies is usually performed in evidence synthesis. The value of a study not only depends on the study design although it is an important aspect. Given the exploratory character of our study, we did not evaluate critically the included studies for the quality.

Finally, the CEBM LOE were primarily designed for clinical and therapeutic medical procedures. Given the specific characteristics of pathology, the possibility of performing studies that correspond to high CEBM LOE is limited [23]. This may explain the high number of low LOE studies in our exploratory map. Having identified this limitation, we recently developed a hierarchy for evidence in tumor pathology (HETP), which adapts CEBM LOE to tumor pathology [24]. This study performed prior to the development of HETP lends support to the concept that CEBM LOE may not accurately reflect the LOE pertaining to tumor pathology. The preparation of evidence maps applying HETP are currently in progress within the WCT EVI MAP project [12], which will enable comparison facilitating adoption of HETP for evidence maps for tumor pathology in future.

Conclusion

The present study represents a first step in the WCT EVI MAP project [12], which aims to assess existing evidence for different tumor types and their descriptors. We observed that, when applying CEBM LOE, most studies were coded as low LOE. We also observed great heterogeneity throughout all assessed areas. The next step will involve mapping the existing evidence for tumor types in WCT-5 using HETP to create living maps to support the editorial boards for the new edition of the WCT for each organ and system. Additionally, we hope to promote high LOE research in the future by mapping existing evidence, both generally and for certain tumor types.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Laura Brispot and Benjamin Duclos for their significant contribution in coordinating this project at the International Agency for Research on Cancer and organizing the email invitations; and Teresa Lee for her precious input and feedback on search strategies.

WCT EVI MAP (in alphabetical order):

- Alex Inskip, NIHR Innovation Observatory Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom.

- Anne-Sophie Bres, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

- Beatriz Perez-Gomez, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

- Clarissa Wong Jing Wen, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore.

- Elena Plans-Beriso, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

- Ester García Ovejero, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

- Fiona Campbell, Newcastle University (UNEW), Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom.

- Inga Trulson, German Heart Center Munich, Munich, Germany.

- Irmina Michalek, Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology (MSCNRIO), Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

- Joanna A. Didkowska, National Research Institute of Oncology, Warsaw, Poland.

- Karolina Worf, German Heart Centre Munich, Munich, Germany.

- Kateryna Maslova, Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology (MSCI), Warsaw, Poland.

- Latifa Bouanzi, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

- Oana Craciun, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

- Łukasz Taraszkiewicz, Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Warszawa, Poland.

- Magdalena Chechlińska, National Research Institute of Oncology, Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

- Magdalena Kowalewska, Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Warszawa, Poland.

- Marina Pollan, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Madrid, Spain.

- Mervyn Hwee Peng Ong, Luma Medical Centre, Singapore, Singapore.

- Michael Gilch, German Heart Center, Munich, Germany.

- Natthawadee Wong Laokulrath, Luma Medical Centre, Singapore, Singapore.

- Nur Diyana Md Nasir, Singapore Breast Surgery Center, Singapore, Singapore.

- Cecile Monnier, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

- Puay Hoon Tan, Luma Medical Centre, Singapore, Singapore.

- Richard Colling, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- Ruoyu Shi, Luma Medical Centre, Singapore, Singapore.

- Sophie Gabriel, German Heart Center Munich, München, Germany.

- Stefan Holdenrieder, German Heart Centre Munich, Munich, Germany.

- Valerie Koh Cui Yun, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore.

- Zi Long Chow, Luma Medical Centre, Singapore, Singapore.

Author contribution

IAC, II, SA, and JDAM performed developed the concept, designed and performed the study concept and design; SA, RCJ, and JDAM provided acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and statistical analysis; CG, DL, IAC, and NM performed writing, review, and revision of the paper; RCJ, DL, and GGL provided technical and material support and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission [HORIZON grant number 101057127]. All partners signed a consortium agreement.

Data availability

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since we developed maps based on published literature and no patient was involved in this study, no Ethics Review Board approval was necessary.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Disclaimer

The content of this article represents the personal views of the authors and does not represent the views of the authors’ employers and associated institutions. Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer / World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer / World Health Organization.

Christine Giesen and Javier del Águila Mejía contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Christine Giesen, Email: giesenc@iarc.who.int.

WCT EVI MAP:

Alex Inskip, Anne-Sophie Bres, Beatriz Perez-Gomez, Clarissa Jing Wen Wong, Elena Plans-Beriso, Ester García Ovejero, Fiona Campbell, Inga Trulson, Irmina Michalek, Joanna A. Didkowska, Karolina Worf, Kateryna Maslova, Latifa Bouanzi, Oana Craciun, Łukasz Taraszkiewicz, Magdalena Chechlińska, Magdalena Kowalewska, Marina Pollan, Mervyn Hwee Peng Ong, Michael Gilch, Natthawadee Wong Laokulrath, Nur Diyana Md Nasir, Cecile Monnier, Puay Hoon Tan, Richard Colling, Ruoyu Shi, Sophie Gabriel, Stefan Holdenrieder, Valerie Cui Yun Koh, and Zi Long Chow

References

- 1.BlueBooksOnline. https://tumourclassification.iarc.who.int/home. Accessed 9 Jan 2024

- 2.Evidence Synthesis and Classification Branch (ESC). https://www.iarc.who.int/branches-esc. Accessed 28 Mar 2024

- 3.Cree IA, Indave Ruiz BI, Zavadil J et al (2021) The International Collaboration for Cancer Classification and Research. Int J Cancer 148:560–571. 10.1002/ijc.33260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salto-Tellez M, Cree IA (2019) Cancer taxonomy: pathology beyond pathology. Eur J Cancer 115:57–60. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commentary: Cancer research quality and tumour classification - Ian A Cree, B Iciar Indave (2020). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1010428320907544. Accessed 28 Mar 2024 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Chew EJC, Tan PH (2023) Evolutionary Changes in Pathology and Our Understanding of Disease. Pathobiology 90:209–218. 10.1159/000526024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahadir CD, Omar M, Rosenthal J et al (2024) Artificial intelligence applications in histopathology. Nat Rev Electr Eng 1:93–108. 10.1038/s44287-023-00012-7 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Indave BI, Colling R, Campbell F et al (2022) Evidence-levels in pathology for informing the WHO classification of tumours. Histopathology 81:420–425. 10.1111/his.14648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White H, Albers B, Gaarder M et al (2020) Guidance for producing a Campbell evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst Rev 16:e1125. 10.1002/cl2.1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell F, Tricco AC, Munn Z et al (2023) Mapping reviews, scoping reviews, and evidence and gap maps (EGMs): the same but different— the “Big Picture” review family. Syst Rev 12:45. 10.1186/s13643-023-02178-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snilstveit B, Vojtkova M, Bhavsar A et al (2016) Evidence & gap maps: a tool for promoting evidence informed policy and strategic research agendas. J Clin Epidemiol 79:120–129. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.WCT EVI MAP: Home. https://wct-evi-map.iarc.who.int/. Accessed 9 Jan 2024

- 13.Explanation of the 2011 OCEBM Levels of Evidence. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/explanation-of-the-2011-ocebm-levels-of-evidence. Accessed 27 Mar 2024

- 14.Del Aguila MJ, Armon S, Campbell F et al (2022) Understanding the use of evidence in the WHO Classification of Tumours: a protocol for an evidence gap map of the classification of tumours of the lung. BMJ Open 12:e061240. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.EPPI-Reviewer: systematic review software. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=2914. Accessed 26 Mar 2024

- 16.EPPI-Mapper. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3790. Accessed 27 Mar 2024

- 17.Zhang Y, Vaccarella S, Morgan E et al (2023) Global variations in lung cancer incidence by histological subtype in 2020: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 24:1206–1218. 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00444-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toh C-K, Wong E-H, Lim W-T et al (2004) The impact of smoking status on the behavior and survival outcome of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis. Chest 126:1750–1756. 10.1378/chest.126.6.1750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang JJ, Wen W, Zahed H et al (2024) Lung Cancer Risk Prediction Models for Asian Ever-Smokers. J Thorac Oncol 19:451–464. 10.1016/j.jtho.2023.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha SY, Choi S-J, Cho JH et al (2015) Lung cancer in never-smoker Asian females is driven by oncogenic mutations, most often involving EGFR. Oncotarget 6:5465–5474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray M, Mubiligi J (2020) An approach to building equitable global health research collaborations. Ann Glob Health 86:126. 10.5334/aogh.3039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Academies of Sciences E, Affairs P and G, Committee on Women in Science E et al (2022) Why Diverse Representation in Clinical Research Matters and the Current State of Representation within the Clinical Research Ecosystem. In: Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups. National Academies Press (US) [PubMed]

- 23.Crawford JM (2007) Original research in pathology: judgment, or evidence-based medicine? Lab Invest 87:104–114. 10.1038/labinvest.3700511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colling R, Indave B, Aguilla J et al (2023) A new hierarchy of research evidence for tumor pathology: a delphi study to define levels of evidence in tumor pathology. Mod Pathol 37:100357. 10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.