Abstract

Self-compassion (SC) and its influence on mental health have always been a significant focus in psychological research, especially given the alarming prevalence of depression among Chinese university students. The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between SC, encompassing both self-warmth and self-coldness, and depression among Chinese undergraduates, with emotion regulation strategies (ERS) serving as a mediator. The sample comprised 21,353 undergraduates from Yunnan Province, China, with data collected at two time points (T1 and T2). SC was measured using the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF), while depression was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). ERS were measured using the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-short (CERQ-short). Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling. Results demonstrated that the model of self-warmth, self-coldness, ERS, and depression fit the data well. Upon controlling for depression at T1, both self-warmth and self-coldness were significant predictors of depression through ERS. ERS were found to be a significant mediator in this study. The results indicated that self-warmth enhances adaptive ERS and reduces maladaptive ERS, leading to lower levels of depression, while self-coldness has the opposite influence.

Keywords: Self-compassion, Self-warmth, Self-coldness, Depression, Emotion regulation strategies

Introduction

The prevalence of depression among Chinese university students is alarmingly high, representing a significant public health issue [1]. Nationwide research indicates that approximately 21.48% of Chinese university students may be at risk of depression [2]. Extensive studies consistently underscore the pivotal role of self-compassion (SC) in enhancing psychological well-being and alleviating psychological distress, correlating with reduced depression and heightened emotional resilience [3–5]. Researchers have increasingly suggested that examining the overall structure of SC may be limited. Instead, it is valuable to distinguish between the positive and negative components of SC [6, 7]. Self-warmth, representing the positive aspect of SC, and self-coldness, representing the negative aspect of SC, may play distinct roles and have differential impacts on psychological functioning [8, 9].

Recent research has proposed that SC functions as an ERS that helps alleviate depression [3, 10]. However, in most studies, SC is viewed as a trait factor, while ERS are considered proximal factors directly linked to depression [11]. Therefore, when examining the impact of SC on depression, it is more appropriate to consider the mediating role of ERS [12]. Previous studies have primarily utilized cross-sectional designs, which are less conducive to exploring causal or predictive relationships.

Hence, this study examines the connections between SC, including self-warmth and self-coldness, and depression among Chinese undergraduates, while also examines the mediating impacts of ERS using data collected at two different time points.

Self-compassion and depression

Depression is a debilitating disorder marked by profound emotional distress, severe interpersonal challenges, and disabling neurovegetative symptoms, which collectively disrupt mood, thoughts, and the body, significantly impairing daily activities such as eating, sleeping, self-perception, and one's overall outlook on life [13]. In the broadest sense, cognitive models of depression emphasize that people become depressed primarily due to the way they think, highlighting the role of negative thinking patterns in the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms [13]. The cognitive theory of depression posits that depressive emotions may stem from cognitive biases such as overgeneralization, self-criticism, and negative self-attribution [14]. SC is defined as the capacity to wholeheartedly embrace one's own pain or distress, with care and avoid harsh self-criticism. It includes being kind to oneself, recognizing that suffering is part of the human experience, and maintaining a balanced awareness of one’s emotions [15]. It has been considered a positive, emotion-focused coping strategy and a potential component of cognitive-behavioral therapies [16]. Individuals with higher levels of SC tend to evaluate their situations objectively, preventing excessive immersion in negative emotions. They view failures or shortcomings as part of the human condition, avoiding harsh self-criticism [17, 18]. Consequently, those with higher SC experience fewer negative emotions. Meta-analyses indicate that increased levels of SC are indeed associated with reduced levels of depression [19–22]. In contrast, individuals with lower levels of SC may harm themselves through an uncompassionate approach, showing little mercy or forgiveness, which places them at greater risk for depression when struggling with negative emotions [16].

SC is increasingly viewed as a multidimensional construct [23, 24], comprising two components: self-warmth and self-coldness. Based on social mentality theory [25], self-warmth includes positive components like self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness, while self-coldness encompasses negative components like self-criticism, isolation and over-identification. Within the framework of the social mentality theory, the threat-defense system and safety system are proposed as two distinct processing mechanisms that shape individuals' responses in social contexts [26, 27]. These independent systems activate distinct ways in which individuals treat themselves. The stimulation of the threat-defense system is correlated with self-coldness, characterized by self-criticism, harshness, and a lack of SC. When this system is active, individuals may develop a hostile relationship with themselves, displaying aggressive or indifferent attitudes when confronted with potential failure or feelings of inadequacy [25, 28, 29]. In contrast, the activation of the safety system is associated with self-warmth, which encompasses feelings of SC, kindness, and care towards oneself. When this system is active, individuals are more likely to treat themselves with understanding and compassion, promoting behaviors that contribute to personal growth and well-being [25]. The positive dimension of SC represents an individual's ability to relate to protective factors, whereas the negative dimension of SC is more of a risk factor [20]. Thus, self-warmth and self-coldness are relatively independent constructs playing different roles in an individual's life. From the perspective of SC, each component has two opposing dimensions. However, individuals in dialectical cultures may not express their attitudes towards the self in a singular way. Hence, in this cultural context, the existence of positive aspects of SC does not automatically indicate the absence of corresponding negative components. Rather, individuals prone to considering self-warmth and self-coldness as two coexisting and separate constructs [30]. This perspective is supported by studies showing that dialectical thinking tendencies, prevalent in certain cultures, allow for the coexistence of positive and negative aspects of the self. For example, in Japanese culture, the simultaneous experience of positive and negative emotions is more common compared to American culture, which may influence the way SC is conceptualized and measured [31]. This cultural variability necessitates the consideration of dialectical thinking in the validation and application of SC scales across different cultural contexts [32]. Therefore, it is necessary to consider SC as a multidimensional construct in studies conducted with Chinese samples.

Research highlights the significance of differentiating between self-warmth and self-coldness. Findings suggest that increasing self-warmth and reducing self-coldness are crucial for mitigating depression. Self-warmth consistently correlates with reduced depression and increased well-being, whereas self-coldness is linked to higher depression [28, 33]. Self-coldness is particularly linked to higher depression, while self-warmth buffers this adverse effect [34, 35]. When studying SC and depression, it is essential to consider the separate dimensions of self-warmth and self-coldness [6, 24, 34]. This dual approach provides a nuanced understanding of SC's role in mental health.

Given these theoretical underpinnings and findings, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1a: There is a significant correlation between self-warmth and depression.

Hypothesis 1b: There is a significant correlation between self-coldness and depression.

The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies

ERS can be categorized into adaptive and maladaptive strategies. Problematic ERS can prolong or intensify negative emotional experiences, and also associated with poorer mental health outcomes, reduced resilience to stressful events, and a wider range of psychopathological symptoms [36–38]. Poor emotion processing and regulation difficulties are common bases for depression [37, 39, 40]. Different ERS significantly impact psychological well-being. Effective use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies (AERS) can mitigate negative emotions and improve psychological well-being [41, 42]. Conversely, maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (MERS) can exacerbate negative emotional states and contribute to the development and persistence of depression [11, 41].

SC, understood as a foundational element influencing the development and effectiveness of ERS, is vital in emotion regulation research for promoting the acceptance of negative emotions and fostering flexibility in AERS [43]. Building on social mentality theory, Gilbert [25, 44] proposed a model of emotion regulation systems that underscores the importance of SC in activating the self-soothing, safe system. Individuals with higher levels of SC are more adept at engaging this system, enabling them to respond to stress with greater calmness and resilience. This ability is fundamental to how individuals manage and regulate their emotions [45, 46]. Research shows a positive correlation between overall SC and AERS, and a negative correlation with MERS [47, 48]. This suggests that SC is not only a precursor but also a facilitator of effective emotion regulation. Individuals with high SC are less likely to engage in rumination and more likely to accept unwanted thoughts and emotions compared to those with low SC [15, 17]. Furthermore, SC enhances emotional awareness and acceptance, which are critical components of AERS. SC enhances non-judgmental recognition of one's emotions and guides individuals to cope with stress in a self-supportive manner, thereby reducing negative emotional responses [49–51], which allows individuals to confront emotional challenges more effectively, paving the way for the use of more sophisticated and AERS [52]. By providing a supportive internal environment, SC helps individuals approach challenges with a more positive and flexible mindset, promoting the use of adaptive strategies which positively impact mental health [12, 48, 53].

Review studies have highlighted the association between SC, emotion regulation, and mental health across various psychological disorders. The findings indicate that SC is consistently linked with AERS, which can alleviate stress and depression by processing and integrating adverse emotions [12, 52]. SC facilitates the use of strategies that reduce avoidance and enhance tolerance of adverse emotions, which is a key mechanism through which SC promotes mental health [12]. It helps individuals maintain better emotion regulation and make more adaptive emotional responses in stress-inducing situations [54, 55].

Most research views SC as a holistic construct, suggesting it helps individuals develop more flexible and AERS [48]. In studies that consider SC as having both positive and negative dimensions, self-warmth is positively associated with AERS and negatively correlated with depression, while self-coldness is positively correlated with depression and MERS [24]. Self-warmth encourages individuals to adopt more constructive attitudes when facing challenges. Through mindfulness and self-kindness, individuals can face stress and challenges more calmly, using healthier and more effective emotional responses rather than resorting to catastrophizing or experiential avoidance [56–58]. Research regarding the connection between self-coldness and ERS is less extensive. However, previous study suggests that self-criticism, a component of self-coldness, increases levels of rumination, emotional suppression, catastrophizing, self-blame, and experiential avoidance [59], which can harm physical and mental health.

Previous research indicates that the ERS serves as a mediating variable between SC and depression [60]. This relationship also holds when SC is viewed as comprising two factors: self-warmth and self-coldness [61]. Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: AERS and MERS mediate the relationship between self-warmth and depression.

Hypothesis 2b: AERS and MERS mediate the relationship between self-coldness and depression.

The current study

This study examines the mediating role of ERS in the relationship between SC and depression among Chinese undergraduates. Specifically, we construct a mediation model wherein self-warmth and self-coldness predict depression through ERS. We hypothesize that both self-warmth and self-coldness serve as significant predictors of depression over time. Furthermore, ERS significantly mediate this relationship.

Methods

Procedures

The data collection for this study took place in two phases. The first data collection point was in September 2022. Participants were recruited through various online platforms and invited to complete an online survey. This survey collected information on socio-demographic variables, SC, ERS, and depression levels. Before starting the survey, participants were required to sign an electronic consent form. Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the ethics committee of the first author’s institution (NO. KMUST-MEC-149). Informed consent was obtained from all participants/legal guardians with an assent from the participant. One year after the initial data collection, at the second data collection point, the same participants were invited to participate in another survey, which focused on their current levels of depression.

Participants

The focus of this study is on undergraduates in Yunnan Province, China. Yunnan is home to a significant number of ethnic minority groups and is a relatively less economically developed province compared to other regions in China. The socio-economic factors may impact the availability of mental health resources and support systems for students. Focusing on this population for research and providing empirical support and implications is therefore highly relevant and meaningful. In the first data collection point, a total of 24,786 undergraduates completed the questionnaires. At the second data collection point, 21,353 participants were retained and provided valid data. The matching of participants across the two time points was accomplished using the first four and last four digits of their phone numbers. To further mitigate any potential risk of mismatches, we have performed additional error-checking by cross-referencing the participants' gender, age, and ethnicity, ensuring a robust verification process. The final sample consisted of 14,115 male students (66.1%) and 7,238 female students (33.9%), aged 16 to 29 years (M ± SD = 20.73 ± 1.27). The detailed demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 14,115 | 66.1 |

| Female | 7,238 | 33.9 |

| Siblings | ||

| One child | 7,606 | 35.6 |

| More than one child | 13,747 | 64.4 |

| Subjective socio-economic status | ||

| Worse | 5,000 | 23.4 |

| Average | 15,144 | 70.9 |

| Better | 1,209 | 5.7 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 9,827 | 46 |

| Rural | 11,526 | 54 |

| Ethnic | ||

| Han Chinese | 17,129 | 80.22 |

| Minority ethnic groups | 4,224 | 19.78 |

Measures

Self-compassion scale-short form (SCS-SF)

SC was measured using the SCS-SF [62], a 12-item scale employing a five-point Likert scale from 1 (Almost never) to 5 (Almost always). The SCS-SF is noted for its conciseness and efficiency, making it a preferred choice for SC assessments. It has been validated in various countries [15, 63, 64]. The Chinese version of the SCS-SF, based on the translation by Chen, Yan [65], has shown strong reliability and validity among Chinese university students [66]. The scale comprises six subscales [62], three subscales for the positive components of SC representing self-warmth, and three subscales for the negative components representing self-coldness. In this study, the SCS-SF had a Cronbach’s α of 0.754. The self-warmth and self-coldness subscales had Cronbach’s α of 0.816 and 0.757, respectively.

Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire short form (CERQ-short)

ERS were assessed using the Chinese version of the CERQ-short, initially developed by Garnefski and Kraaij [67] and adapted into Chinese by Zhu, Auerbach [68]. This scale has been validated in the Chinese cultural context [69–71]. The CERQ-short employs a five-point Likert scale, with responses from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The scale includes nine dimensions: putting into perspective, positive refocusing, positive reappraisal, planning, acceptance, self-blame, other-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing. Each dimension consists of two items, totaling 18 questions. The first five dimensions are categorized as AERS, while the last four are categorized as MERS. Higher scores in each dimension indicate a stronger tendency to use that strategy when dealing with negative events.

The acceptance dimension has shown inconsistent correlations with negative psychological outcomes in previous research, sometimes even positively predicting negative psychological results, as it may align more closely with a sense of resigned acceptance [72, 73]. Given these inconsistencies and its factor loading of 0.38 in our CFA of the measurement model, we excluded acceptance from the AERS in our study. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for AERS was 0.824, and for MERS, it was 0.744.

Beck depression inventory (BDI)

The BDI was employed to assess the severity of depression among participants. Designed to evaluate both the nature and extent of depression, the BDI examines symptoms associated with emotional, cognitive, motivational, and physiological experiences linked to depression [74]. The inventory comprises 21 questions, each containing four statements that progressively describe increased levels of depressive symptoms. Participants assess their feelings on a scale of 0 to 3. The Chinese version of the BDI has shown good reliability and validity [75, 76]. The Cronbach's α values of BDI were 0.880 and 0.888 at two different time points in this study.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were conducted using SPSS 29.0. The structural equation model (SEM) was employed in Amos 29.0 to assess the predictive effects of self-warmth and self-coldness on depression. In the SEM analysis, depression at Time 1 (T1) was included as a control variable. The bootstrap analysis with 5000 replicates was employed to examine the 95% confidence intervals of the mediating effects of ERS in the SEM.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the main study variables are presented in Table 2. The results indicate that self-warmth has a mean of 21.96 (SD = 3.973), while self-coldness has a mean of 16.38 (SD = 4.234). The mean scores for AERS and MERS are 32.94 (SD = 5.618) and 21.02 (SD = 4.037), respectively. The mean score for depression is 4.26 (SD = 5.909).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, skewness, and kurtosis for study variables

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Self-warmth | 21.96 | 3.973 | 1 | − 0.349 | 0.392 | ||||

| 2 | Self-coldness | 16.38 | 4.234 | − 0.119** | 1 | 0.212 | − 0.001 | |||

| 3 | AERS | 32.94 | 5.618 | 0.312** | − 0.075** | 1 | − 0.118 | 0.884 | ||

| 4 | MERS | 21.02 | 4.037 | − 0.089** | 0.300** | 0.137** | 1 | 0.202 | 1.171 | |

| 5 | Depression | 4.260 | 5.909 | − 0.217** | 0.268** | − 0.198** | 0.258** | 1 | 2.241 | 7.428 |

Note. **p < 0.01; AERS = adaptive emotion regulation strategies, MERS = maladaptive emotion regulation strategies

As shown in Table 2, the skewness and kurtosis values of the study variables were within acceptable ranges, with skewness values ranging from -3 to + 3 and kurtosis values ranging from − 10 to + 10 [77]. The VIF values for all constructs ranged from 1.120 to 1.153 (below 10), with tolerance values above 0.10 [78], indicating no collinearity issues in the structural model, thereby allowing further analysis to proceed. Harman's single-factor test was primarily employed in this study as a statistical remedy for common method bias. There was no single factor accounting for more than 40% of the variance [79], as the percentage of variance explained by the first component was 34.21%, suggesting that common method bias was not a significant issue in this study. The sample mean for self-warmth was above the midpoint of the scale, while for self-coldness, it was below the midpoint. Similarly, the mean score on AERS exceeded the midpoint, whereas the mean on MERS was below it. The average depression level fell below the clinical cutoff score for moderate depression on the BDI.

The correlational analyses revealed several significant relationships. Self-warmth showed a negative correlation with self-coldness, MERS, and depression, and a positive correlation with AERS. These findings suggest that higher levels of self-warmth are associated with lower levels of self-coldness, MERS, and depression, while simultaneously promoting AERS. The positive correlation between self-warmth and AERS (r = 0.312), although moderate, indicates that individuals who exhibit greater self-compassionate warmth are more likely to engage in healthy emotion regulation practices. However, the effect size suggests that while self-warmth is a contributing factor, other influences also play a role in the use of AERS. Conversely, self-coldness was positively correlated with MERS and depression, and negatively correlated with AERS. This pattern indicates that higher levels of self-coldness are linked to less AERS and higher levels of depressive symptoms. The correlation between self-coldness and depression (r = 0.268) further underscores the detrimental impact, although the strength of the correlation suggests that self-coldness is just one of several factors contributing to depressive symptoms. The relationships between AERS, MERS and depression, also provide important insights. AERS was negatively correlated with depression (r = -0.198), implying that effective emotion regulation can reduce depressive symptoms. On the other hand, the positive correlation between MERS and depression (r = 0.258) suggests that MERS are linked to higher levels of depression.

The mediation model

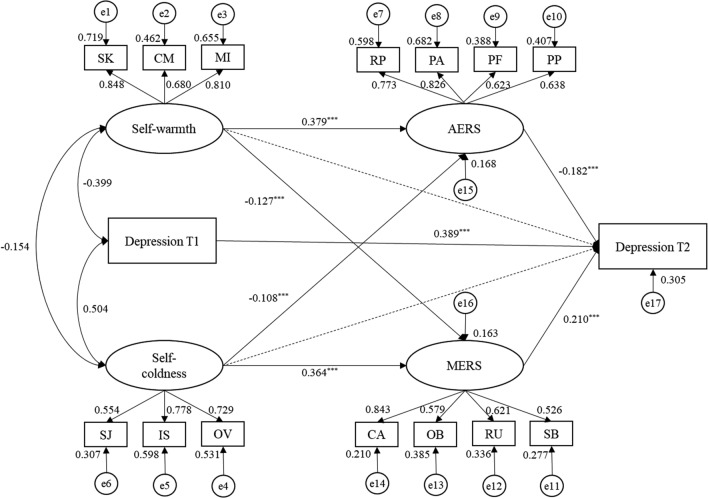

Figure 1 displays the standardized coefficients of the mediation model. The model achieved acceptable fit indices (RMSEA = 0.032, GFI = 0.963, AGFI = 0.957, CFI = 0.947, NFI = 0.945, TLI = 0.942). Upon controlling for depression at T1, the results showed that the direct effect paths from self-warmth and self-coldness to depression were not significant (dotted line). As illustrated in Table 3, the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the mediating effects of AERS and MERS between self-warmth, self-coldness, and depression did not include zero. This indicates that the mediating effects are significant.

Fig. 1.

The mediation model (***p < 0.001, SK = Self-kindness, CM = Common humanity, MI = Mindfulness, SJ = Self-judgment, IS = Isolation, OV = Overidentification, AERS = adaptive emotion regulation strategies, MERS = maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, RP = Refocus on planning, PA = Positive reappraisal, PF = Positive refocusing, PP = Putting into perspective, CA = Catastrophizing, OB = Other-blame, RU = Rumination, SB = Self-blame)

Table 3.

The confidence intervals and effect sizes of the mediation model

| Mediation paths | Estimate | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-warmth → AERS → Depression | − 0.014 | < 0.001 | [− 0.015, − 0.012] |

| Self-warmth → MERS → Depression | − 0.005 | < 0.001 | [− 0.006, − 0.002] |

| Self-coldness → AERS → Depression | 0.004 | < 0.001 | [0.003, 0.005] |

| Self-coldness → MERS → Depression | 0.016 | < 0.001 | [0.014, 0.018] |

AERS = adaptive emotion regulation strategies, MERS = maladaptive emotion regulation strategies

In the structural model, the analysis revealed that self-warmth had a significant positive effect on AERS (β = 0.379, p < 0.001), and a significant negative effect on MERS (β = -0.127, p < 0.001). These coefficients indicate that higher levels of self-warmth are strongly associated with the use of AERS, which are crucial for effectively managing emotions in real-life situations. The negative effect on MERS suggests that self-warmth also plays a role in reducing the reliance on maladaptive strategies, further supporting its beneficial impact on emotional well-being. Conversely, self-coldness exhibited a significant negative effect on AERS (β = -0.108, p < 0.001), and a significant positive effect on MERS (β = 0.364, p < 0.001). These results highlight that self-coldness contributes to a decrease in the use of adaptive strategies and an increase in maladaptive ones, which can exacerbate emotional difficulties. The indirect effects of self-warmth and self-coldness on depression through AERS and MERS were also significant. For instance, the impact of self-warmth on depression through AERS (β = -0.182, p < 0.001) underscores the protective role of AERS in reducing depressive symptoms. On the other hand, the positive indirect effect of self-coldness on depression through MERS (β = 0.210, p < 0.001) indicates that maladaptive strategies may serve as a pathway through which self-coldness heightens the risk of depression.

The model explained 30.5% of the variance in depression. The model’s total effects were as follows: self-warmth (β = -0.096, t = -4.75), self-coldness (β = 0.096, t = 5), AERS (β = -0.182, t = -5.75) and MERS (β = 0.210, t = 14.44). The mediation analysis revealed that AERS and MERS explained 19.73% of the total effect.

Discussion

The current study examined the impacts of self-warmth and self-coldness on depression by collecting data at two different time points. We have found that self-warmth and self-coldness could significantly predict the presence of depression through ERS among undergraduate students. The analysis demonstrates that both AERS and MERS serve as mediators in these relationships.

The descriptive statistics indicate a moderate level of SC among undergraduates in Yunnan Province, suggesting that most students generally hold a balanced view toward themselves, being neither overly critical nor unconditionally self-accepting. Neff and their research team conducted a series of cross-cultural studies on SC (which did not include Chinese university students), it was found that Korean undergraduates reported the highest level of SC [80]. The levels of SC among the participants in this study closely align with the results obtained from Korean undergraduates. Previous researchers found these findings somewhat unexpected. This is particularly surprising considering the influence of Confucianism in East Asian cultures, which is generally thought to promote self-criticism as a means of achieving success [15, 81]. In the context of East Asian cultures, where Confucian ideals often emphasize self-criticism and humility, the moderate to high levels of SC observed among Chinese university students might indicate a shift towards more balanced self-views influenced by increasing exposure to global psychological trends and educational practices that promote mental health and well-being. In collectivist cultures like China, individuals tend to view themselves as part of a larger social group, often prioritizing harmonious relationships when making decisions or engaging in behaviors [82]. In this context, SC may be seen as a balance between self-care and maintaining social harmony [83]. A strong sense of responsibility to others, along with social or familial pressures, could limit individuals' willingness to engage in SC, as they may fear being perceived as selfish or neglectful of communal duties. Our findings revealed that self-warmth coexists with self-coldness among Chinese undergraduates.

Our findings align with previous research, indicating that self-warmth enhances the levels of AERS [47, 53, 84]. The findings of this study revealed that the pathway from self-warmth to depression through AERS exhibited a significant negative mediation effect. This indicates that higher levels of self-warmth are associated with increased use of AERS, which, in turn, lead to lower levels of depression. Similarly, the pathway from self-warmth to depression through MERS also exhibited a negative mediation effect, though to a lesser extent. This suggests that while self-warmth reduces the use of MERS, the influence through AERS is more pronounced. In contrast, the mediation pathways involving self-coldness were positively associated with depression. The pathway from self-coldness to depression via AERS showed a positive mediation effect, implying that higher levels of self-coldness are linked to decreased use of AERS, thereby increasing depression levels. Moreover, the pathway from self-coldness to depression through MERS demonstrated the strongest positive mediation effect, indicating that self-coldness significantly increases the use of MERS, which, in turn, exacerbates depression.

The threat-protection system, as described by Gilbert [44], is an emotion regulation mechanism that enables the appropriate detection and response to threats. This system comprises three subsystems: the threat-defense system, focused on protection and safety-seeking; the safety-soothing system, centered on affiliative focus and well-being; and the drive-activation system, aimed at seeking out rewards and achieving goals. Gilbert [44] theorized that the ability for SC is foundational in developing adaptive emotion regulation skills.

Activation of the safety system is associated with self-warmth, encompassing feelings of compassion, kindness, and care towards oneself. This system enables behaviors essential for health and happiness, such as establishing secure and protective relationships with oneself and experiencing internal messages of tranquility and care [85]. When this system is active, individuals are more likely to treat themselves with understanding and compassion, promoting behaviors that contribute to personal growth and well-being. Self-warmth involves acknowledging one's suffering without self-judgment, fostering a nurturing internal environment that supports mental and emotional health [25]. This internal warmth and understanding help individuals provide self-comfort in the face of failure or difficulty, reducing the extent of self-criticism, and encouraging individuals to handle negative emotions more positively. Through self-warmth, individuals can reframe stressful situations as opportunities for growth and learning rather than mere threats or failures. This cognitive shift supports the adoption of more AERS, such as rational thinking, seeking support, and positive reappraisal [56, 60]. Additionally, self-warmth reduces the levels of MERS, consistent with previous research [48, 57, 58]. Self-warmth enhances confidence in one's ability to cope with challenges and difficulties. This heightened self-efficacy reduces the likelihood of resorting to MERS, such as expressive suppression, avoidance, and self-blame, because individuals feel more capable of managing their emotions healthily.

The stimulation of the threat-defense system is correlated with self-coldness, characterized by self-criticism, harshness, and a lack of SC [25]. This system primarily focuses on detecting and responding to potential threats, leading to defensive behaviors aimed at protecting oneself from harm or danger. When this system is active, individuals may develop a hostile relationship with themselves, displaying aggressive or indifferent attitudes when confronted with potential failure or feelings of inadequacy [85]. Self-coldness can manifest as negative self-talk, self-blame, and lack of kindness towards oneself [28].

Self-coldness increases the levels of MERS, corroborating previous research on the impact of self-criticism on MERS, such as rumination, expressive suppression, catastrophizing, self-blame, and experiential avoidance [59, 86]. Self-coldness can lead to the generalization of negative emotions, trapping individuals in a persistent negative emotional state and making it difficult to adopt effective ERS. In this fixed emotional state, individuals are more inclined to use MERS, such as negative avoidance and emotional suppression. AERS require more cognitive functioning to cognitively reconstruct stress and emotions. However, self-coldness might cause individuals to focus excessively on their negative emotions and deficiencies [84]. This excessive introspection and self-anxiety can deplete psychological resources, making it difficult to adopt AERS that require more cognitive and emotional resources.

These findings underscore the dual role of SC facets in influencing ERS and subsequent depression outcomes. Self-warmth appears to be a protective factor against depression by enhancing AERS and reducing maladaptive ones. Conversely, self-coldness exacerbates depression by diminishing AERS and increasing reliance on maladaptive ones. By controlling for depression at T1, our findings revealed that ERS serve as a complete mediator in this relationship. Initially, we observed a significant direct effect of multidimensional SC on depression. However, after accounting for T1 depression, this direct effect was no longer significant, indicating that ERS fully mediate the relationship between SC and depression. This highlights the critical importance of ERS as a mechanism in understanding how SC influences depressive outcomes.

Implications

Our findings contribute new knowledge to studies about the formulation and development of psychological interventions aimed at reducing depression through the enhancement of SC and ERS. By delineating the distinct roles of self-warmth and self-coldness, our research provides a more granular understanding of SC’s multifaceted nature and its differential impact on mental health outcomes. These findings support social mentality theory, which posits that SC involves the activation of internal systems.

Furthermore, this study extends past research by demonstrating the mediating mechanisms in the predictive relationships over time through data collected at two different points. By showing that ERS fully mediate the relationship between SC and depression, our findings emphasize the critical role of these strategies in mental health interventions.

In practical terms, the findings suggest that mental health programs for university students should incorporate components that foster SC. Such programs can help students develop healthier ways of managing negative emotions, thereby reducing the risk of depression. Our study provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the interplay between SC, ERS, and depression. It offers valuable insights for the development of targeted interventions that can enhance psychological well-being and reduce the prevalence of depression among Chinese undergraduates.

Limitations

The present study carries several limitations that require acknowledgment. The sample primarily consisted of undergraduate students, necessitating caution when generalizing the research findings to broader populations. The homogeneity of this group may limit the applicability of the results to a broader demographic.

Another limitation of our study is the use of partial phone numbers for participant matching, which, despite being a measure to balance accuracy and confidentiality, may still raise privacy and confidentiality concerns. Specifically, the use of even partial identifiers could potentially compromise data security and participant privacy. Although we implemented strict data protection protocols to mitigate these risks, the inherent sensitivity of such information remains a limitation that should be considered when interpreting the study’s findings.

Self-report measures can introduce biases, including response style effects and social desirability, which may affect the accuracy of the data collected. To mitigate these potential biases, we employed well-validated and widely used self-report instruments with strong psychometric properties. Additionally, we assured participants of the confidentiality of their responses, which we believe reduced social desirability bias and encouraged more honest reporting. Despite these precautions, we acknowledge that some level of bias may still be present in the data. Collecting objective indicators in future research could further enhance the validity of the findings, to complement self-report data and provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the constructs studied.

The relatively low average depression score observed in our sample appears lower than what is typically reported among student populations. This may indicate that our sample consists of students who generally experience lower levels of depressive symptoms, or it could suggest that the scale used was less sensitive in capturing the full spectrum of depression present in the broader community. This limitation may impact the generalizability of our findings. Future research should consider utilizing more sensitive or alternative measures of depression to ensure a more comprehensive representation of depressive symptoms across similar populations.

Additionally, future research should consider potential confounding variables that might influence the relationship between SC, ERS, and depression. Identifying and controlling for these variables would strengthen the robustness of the findings and provide a clearer understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between multidimensional SC (self-warmth and self-coldness) and depression among Chinese undergraduates, focusing on the mediating role of ERS. Our findings indicate that self-warmth enhances AERS and reduces MERS, leading to lower levels of depression. Conversely, self-coldness decreases the use of AERS and increases reliance on MERS, resulting in higher levels of depression. These results highlight the protective role of self-warmth and the detrimental impact of self-coldness on mental health. The study underscores the importance of cultivating SC and targeting emotion regulation in interventions aimed at reducing depression for Chinese undergraduates, as ERS fully mediate the relationship between SC and depression.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff and administrators at our participating universities. We are especially indebted to the undergraduates and teachers whose participation made this research possible.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Y.P.. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Y.P. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Z.I. provided critical edits. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Kunming University of Science and Technology (Approval No: KMUST-MEC-149). This study has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all participants/legal guardians with an assent from the participant.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liu XQ, et al. Influencing factors, prediction and prevention of depression in college students: a literature review. World J Psychiatry. 2022;12(7):860–73. 10.5498/wjp.v12.i7.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang, Y., L. Wang, and Z. Chen, Report on the mental health status of college students in 2022, In: X. Fu, et al. (Eds). Report on national mental health development in China 2020, 2023, Social Sciences Academic Press (CHINA): Bei Jing. 70–76.

- 3.Diedrich A, et al. Self-compassion enhances the efficacy of explicit cognitive reappraisal as an emotion regulation strategy in individuals with major depressive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2016;82:1–10. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karakasidou E, et al. Self-compassion and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of Greek college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(6):4890. 10.3390/ijerph20064890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo Y, et al. Self-compassion may reduce anxiety and depression in nursing students: a pathway through perceived stress. Public Health. 2019;174:1–10. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muris P, Otgaar H. Deconstructing self-compassion: How the continued use of the total score of the self-compassion scale hinders studying a protective construct within the context of psychopathology and stress. Mindfulness. 2022;13(6):1403–9. 10.1007/s12671-022-01898-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muris P, Otgaar H. The process of science: a critical evaluation of more than 15 years of research on self-compassion with the self-compassion scale. Mindfulness. 2020;11(6):1469–82. 10.1007/s12671-020-01363-0. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung J, et al. The relations between self-compassion, self-coldness, and psychological functioning among North American and hong kong college students. Mindfulness. 2021;12(9):2161–72. 10.1007/s12671-021-01670-0. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner RE, et al. Two is more valid than one: examining the factor structure of the self-compassion scale (SCS). J Counseling Psychol. 2017;64(6):696–707. 10.1037/cou0000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preuss H, et al. Cognitive reappraisal and self-compassion as emotion regulation strategies for parents during COVID-19: An online randomized controlled trial. Int Intervent. 2021;24:100388. 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kökönyei G, et al. Emotion regulation predicts depressive symptoms in adolescents: a prospective study. J Youth Adolescence. 2024;53(1):142–58. 10.1007/s10964-023-01894-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inwood E, Ferrari M. Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: a systematic review. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2018;10(2):215–35. 10.1111/aphw.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingram RE, et al. Depression: social and cognitive aspects. In: Krueger RF, Blaney PH, editors., et al., Oxford textbook of psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2023. p. 257–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(8):969–77. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neff KD. Self-compassion: theory and measurement. In: Finlay-Jones A, Bluth K, Neff K, editors. Handbook of self-compassion. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akbari M, et al. Neglected side of romantic relationships among college students: breakup initiators are at risk for depression. Fam Relations. 2022;71(4):1698–712. 10.1111/fare.12682. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neff KD. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):85–101. 10.1080/15298860309032. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neff KD. Self-compassion: theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Rev Psychol. 2023;74(1):193–218. 10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muris P, Otgaar H. Self-esteem and self-compassion: a narrative review and meta-analysis on their links to psychological problems and well-being. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2023;16:2961–75. 10.2147/PRBM.S402455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muris P, Petrocchi N. Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017;24(2):373–83. 10.1002/cpp.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zessin U, Dickhäuser O, Garbade S. The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: a meta-analysis. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2015;7(3):340–64. 10.1111/aphw.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muris P, Fernández-Martínez I, Otgaar H. On the edge of psychopathology: strong relations between reversed self-compassion and symptoms of anxiety and depression in young people. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2024;27(2):407–23. 10.1007/s10567-024-00471-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullrich-French S, Cox AE. The use of latent profiles to explore the multi-dimensionality of self-compassion. Mindfulness. 2020;11(6):1483–99. 10.1007/s12671-020-01365-y. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muris P, et al. Good and bad sides of self-compassion: a face validity check of the self-compassion scale and an investigation of its relations to coping and emotional symptoms in non-clinical adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(8):2411–21. 10.1007/s10826-018-1099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert P. Self-compassion: an evolutionary, biopsychosocial, and social mentality approach. In: Finlay-Jones A, Bluth K, Neff K, editors. Handbook of self-compassion. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert P. A brief outline of the evolutionary approach for compassion focused therapy. EC Psychol Psychiatry, 2017.

- 27.Gilbert P. Compassion and cruelty: a biopsychosocial approach. In: Gilbert P, editor. Compassion. London: Routledge; 2005. p. 9–74. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen GE. Self-compassion and self-coldness: Effects on psychological well-being and distress in cultural context, in school of psychology. 2020, Fuller Theological Seminary: United States, California. p. 66.

- 29.Gilbert P, et al. Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2011;84(3):239–55. 10.1348/147608310X526511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chio FHN, Mak WWS, Yu BCL. Meta-analytic review on the differential effects of self-compassion components on well-being and psychological distress: the moderating role of dialecticism on self-compassion. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:101986. 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto Y, Ryff CD. Cultural differences in the dialectical and non-dialectical emotional styles and their implications for health. Cogn Emotion. 2011;25(1):22–39. 10.1080/02699931003612114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arimitsu K. Self-compassion across cultures. In: Finlay-Jones A, Bluth K, Neff K, editors. Handbook of self-compassion. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 129–41. [Google Scholar]

- 33.López A, Sanderman R, Schroevers MJ. A close examination of the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms. Mindfulness. 2018;9(5):1470–8. 10.1007/s12671-018-0891-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brenner RE, et al. Do self-compassion and self-coldness distinctly relate to distress and well-being? A theoretical model of self-relating. J Counseling Psychol. 2018;65(3):346–57. 10.1037/cou0000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson C, Misajon R, Brooker J. Self-compassion and self-coldness and their relationship with psychological distress and subjective well-being among community-based Hazaras in Australia. Transcult Psychiatry. 2024;61(2):229–45. 10.1177/13634615241227683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):217–37. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dryman MT, Heimberg RG. Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: a systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;65:17–42. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cludius B, Mennin D, Ehring T. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion. 2020;20(1):37–42. 10.1037/emo0000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(3):316–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aksu G, Eser MT, Huseynbalayeva S. The relationship between depression and emotion dysregulation: a meta-analytic study. Turkish Psychol Counseling Guidance J. 2023;13(71):494–509. 10.17066/tpdrd.1292047_7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schäfer JÖ, et al. Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: a meta-analytic review. J Youth Adolescence. 2017;46(2):261–76. 10.1007/s10964-016-0585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lincoln TM, Schulze L, Renneberg B. The role of emotion regulation in the characterization, development and treatment of psychopathology. Nat Rev Psychol. 2022;1(5):272–86. 10.1038/s44159-022-00040-4. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Himmerich SJ, Orcutt HK. Examining a brief self-compassion intervention for emotion regulation in individuals with exposure to trauma. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(8):907–10. 10.1037/tra0001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilbert P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. Br J Clin Psychol. 2014;53(1):6–41. 10.1111/bjc.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(3):223–50. 10.1080/15298860309027. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilbert P. Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Adv Psychiatric Treatment. 2009;15(3):199–208. 10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Finlay-Jones AL, Rees CS, Kane RT. Self-compassion, emotion regulation and stress among Australian psychologists: testing an emotion regulation model of self-compassion using structural equation modeling. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0133481. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paucsik M, et al. Self-compassion and emotion regulation: testing a mediation model. Cogn Emot. 2023;37(1):49–61. 10.1080/02699931.2022.2143328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J Res Personal. 2007;41(1):139–54. 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kroshus E, Hawrilenko M, Browning A. Stress, self-compassion, and well-being during the transition to college. Soc Sci Med. 2021;269:113514. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allen AB, Leary MR. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2010;4(2):107–18. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finlay-jones AL. The relevance of self-compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clin Psychol. 2017;21(2):90–103. 10.1111/cp.12131. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Diedrich A, et al. Adaptive emotion regulation mediates the relationship between self-compassion and depression in individuals with unipolar depression. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2017;90(3):247–63. 10.1111/papt.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dundas I, et al. Self-compassion and depressive symptoms in a Norwegian student sample. Nordic Psychol. 2016;68(1):58–72. 10.1080/19012276.2015.1071203. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Svendsen JL, et al. Trait Self-compassion reflects emotional flexibility through an association with high vagally mediated heart rate variability. Mindfulness. 2016;7(5):1103–13. 10.1007/s12671-016-0549-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wisener M, Khoury B. Specific emotion-regulation processes explain the relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion with coping-motivated alcohol and marijuana use. Addict Behav. 2021;112:106590. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Refae M, et al. A self-compassion and mindfulness-based cognitive mobile intervention (Serene) for depression, anxiety, and stress: Promoting adaptive emotional regulation and wisdom. Front Psychol. 2021;12:648087. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson EA, O’Brien KA. Self-compassion soothes the savage ego-threat system: effects on negative affect, shame, rumination, and depressive symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2013;32(9):939–63. 10.1521/jscp.2013.32.9.939. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gadassi Polack R, et al. Emotion regulation and self-criticism in children and adolescence: longitudinal networks of transdiagnostic risk factors. Emotion. 2021;21(7):1438–51. 10.1037/emo0001041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bakker AM, et al. Emotion regulation as a mediator of self-compassion and depressive symptoms in recurrent depression. Mindfulness. 2019;10(6):1169–80. 10.1007/s12671-018-1072-3. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rask B, Andersson O. Emotion regulation difficulties as a mediator between self-compassion, self-warmth, self-coldness and mental health. 2019; 22.

- 62.Raes F, et al. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(3):250–5. 10.1002/cpp.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garcia-Campayo J, et al. Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health Quality Life Outcomes. 2014;12:4. 10.1186/1477-7525-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayes JA, et al. Construct validity of the self-compassion scale-short form among psychotherapy clients. Counselling Psychol Quarter. 2016;29(4):405–22. 10.1080/09515070.2016.1138397. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen J, Yan S, Zhou L. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Self-compassion Scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2011;19(6):734–6. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2011.06.006. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang L-Y, et al. Longitudinal measurement invariance, validity, and reliability analysis of the self-compassion scale-short form among Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2023;31(01):107–111115. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2023.01.019. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire—development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personal Individual Diff. 2006;41(6):1045–53. 10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu X, et al. Psychometric properties of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire: Chinese version. Cogn Emotion. 2008;22(2):288–307. 10.1080/02699930701369035. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng X, et al. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the Chinese version of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire-short in patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2024;33(7):e6373. 10.1002/pon.6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun J, et al. The mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation in BIS/BAS sensitivities, depression, and anxiety among community-dwelling older adults in China. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2020;13:939–48. 10.2147/PRBM.S269874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cai W-P, et al. Relationship between cognitive emotion regulation, social support, resilience and acute stress responses in Chinese soldiers: exploring multiple mediation model. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:71–8. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jermann F, et al. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ). Eur J Psychol Assess. 2006;22(2):126–31. 10.1027/1015-5759.22.2.126. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rice K, et al. Factorial and construct validity of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ) in an Australian sample. Aus Psychol. 2022;57(6):338–51. 10.1080/00050067.2022.2125280. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steer RA, et al. Dimensions of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in clinically depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55(1):117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang W, Wu D, Peng F. Application of Chinese version of beck depression inventory-II to Chinese first-year college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2012;20(6):762–4. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shek DT. Reliability and factorial structure of the Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol. 1990;46(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kline RB. Structural equation modeling. In: Nichols AL, Edlund J, editors. The cambridge handbook of research methods and statistics for the social and behavioral sciences. Cambridge: Building a Program of Research Cambridge University Press; 2023. p. 535–58. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pallant J. SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. London: Routledge; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Podsakoff PM, et al. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tóth-Király I, Neff KD. Is Self-compassion universal? Support for the measurement invariance of the self-compassion scale across populations. Assessment. 2021;28(1):169–85. 10.1177/1073191120926232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heine SJ. An exploration of cultural variation in self-enhancing and self-improving motivations. In: Cross-cultural differences in perspectives on the self. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2003. p. 118–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98(2):224–53. 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhao M, et al. Self-compassion in Chinese young adults: Specific features of the construct from a cultural perspective. Mindfulness. 2021;12(11):2718–28. 10.1007/s12671-021-01734-1. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Phillips WJ. Self-compassion mindsets: the components of the self-compassion scale operate as a balanced system within individuals. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(10):5040–53. 10.1007/s12144-019-00452-1. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gilbert P. Compassion focused therapy: an evolution- informed, biopsychosocial approach to psychotherapy: history and challenge, in compassion focused therapy: clinical practice and applications. New York: Routledge; 2022. p. 24–89. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodrigues TF, et al. The mediating role of self-criticism, experiential avoidance and negative urgency on the relationship between ED-related symptoms and difficulties in emotion regulation. Eur Eating Disord Rev. 2022;30(6):760–71. 10.1002/erv.2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.