Abstract

Background

The issue of substance use is increasingly being recognised as a significant global public health concern. In relation to its influence in the Arab world, scholarly investigation continues to be regarded as relatively constrained in scope. We aimed to investigate the prevalence of substance use among patients with psychiatric disorders, as well as the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of this patient population.

This cross-sectional study included 671 patients with psychiatric disorders who attended an outpatient private psychiatric clinic in Amman, Jordan, between January and May 2023. We compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of substance-using and non-substance-using patients. Bivariate and multiple binary logistic regression analyses were used to investigate factors associated with substance use.

Results

The patients were aged 20–80 years, with a mean age of 32.45 ± 10.18 years. Most patients were men, more than half were single and unemployed, and mood disorders were the most prevalent psychiatric disorder. Male sex, a younger age, lower educational attainment, current unemployment, and having a family history of substance use were associated with substance use. Substance users exhibited a higher propensity for engaging in self-harming behaviours, having medical conditions, and being subjected to emotional trauma.

Conclusions

This study found that patients with psychiatric disorders are vulnerable to experiencing substance use. Clinicians should contemplate directing their attention towards patients as a strategy to proactively address the issue of emerging substance use and enhance overall treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Cannabis, Mental illness, Psychiatric patient, Substance use

Background

Substance use among patients with psychiatric disorders is recognised as a major public health concern worldwide. However, the extent of this issue remains unclear [1, 2]. Extant statistics on substance misuse indicate that, notwithstanding legal, cultural, and religious limitations, substance abuse is a growing issue throughout the Arab world. In Arab countries, the World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that the prevalence of alcohol-use disorder varies from 8.7% in Lebanon to 0.3% in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Libya. Drug abuse is also present in Arab countries, and scholarly research indicates varying rates of substance abuse in each country [3].

In the United States, the abuse of drugs, including alcohol, is the most common cause of preventable illness and death [4]. More than 350,000 deaths annually are attributed to drug (including alcohol) use [5]. The National Institute of Drug Abuse and the 2015 National Survey of Drug Use and Health reported that 20.8 million people older than 12 years had substance-related illnesses [6]. Despite strict laws against substance use in the Arab world, alcohol remains the most commonly used substance, especially among adolescents and young adults, with a prevalence ranging from 4.3% to 70% [7]. However, there is a scarcity of epidemiological studies on drug use in Arab psychiatric and general populations [8].

The prevalence of substance use among individuals with severe mental illnesses, such as bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, antisocial personality disorder, and borderline personality disorder, is high [9–13]. Comorbid substance use in patients with psychosis may adversely affect their clinical and social outcomes [9, 13]. Patients with comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders have been investigated worldwide; however, patterns of substance use may vary widely across demographic groups [9].

Despite inconsistent reporting of substance use prevalence rates among patients with psychiatric disorders due to variations in sample size and detection methods, certain features of individuals who use substances remain consistent across studies in this population. Previous research has indicated a correlation between the presence of psychiatric disorders, substance use, and certain demographic factors, such as being male, young, single, and having lower educational levels [14–16].

A better understanding of substance use trends among patients with psychiatric illnesses could greatly benefit healthcare policymakers and practitioners. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to assess the extent of substance use among outpatients in psychiatric clinics in Jordan and determine the demographic and clinical characteristics involved. Thus, the primary goal of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of substance use in a sample of patients with psychiatric disorders who attended a psychiatric clinic in Amman and analyse this in relation to demographic and clinical variables.

Methods

Study design, setting, and period

This cross-sectional study was conducted at an outpatient private psychiatric clinic in Amman, Jordan, over a 5-month period (January to May 2023) after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board of Al-Balqa Applied University (1069/1/3/26). This private clinic provides treatment for a wide range of patients suffering from mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance use disorders, and those with dual diagnosis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All participants were adults aged 18 years or older at the time of inclusion and provided written informed consent to participate. Excluded from the study were thirty-nine patients who were below the age of eighteen, had incomplete or insufficient data, or declined to provide consent. A total of 671 patients with psychiatric disorders attending the outpatient private psychiatric clinic for treatment and meeting the criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder were included. We reviewed the clinical data and demographic parameters of the patients, including age, marital status, educational attainment, occupational history, clinical presentations, medical history (like diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism), history of self-harm, history of abuse [e.g. physical which means a person's intentional violent behavior toward another that results in bodily injury, emotional which means interpersonal violence that incorporates all forms of non-physical violence and distress exhibited through verbal and non-verbal actions, sexual which means one individual's abusive sexual behavior toward another], and current substance use, including alcohol use.

All patients underwent a psychiatric examination by a psychiatrist via a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5). Information regarding drug use was obtained using a supportive approach to encourage patients to respond truthfully. Urine tests for psychoactive substances were performed using Abo17 Biopharm multi drug screening kits. We compared clinical and demographic variables between the patients who did and those who did not use drugs.

Statistical analyses

Data were gathered and tabulated using SPSS software, version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous data are presented as means and standard deviations. Multiple response analysis was used to demonstrate the frequency and percentage of psychoactive substances used. Bivariate and multiple binary logistic regression analyses were employed to investigate factors associated with substance use, with odds ratios (ORs) used to measure the strength of the association between predictors and the outcome variable. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants

Among the 671 patients included in the study, 48.0% (n = 322) reported substance use, while 52.0% (n = 349) did not. The mean age of the patients was 32.45 ± 10.18 years, and 81.4% (n = 546) were men. Among the participants, 388 (57.8%) were single, 360 (53.7%) held a bachelor’s degree or higher, 394 (58.7%) were employed, and 545 (81.2%) lived with their families. Moreover, 506 (75.4%) were smokers, 110 (16.4%) reported having a medical illness, and 25% disclosed engaging in self-harm. The most prevalent psychiatric diagnosis was major depressive disorder, accounting for 30.6% of cases, followed by anxiety disorders (28.0%). Additionally, 148 patients (22.1%) reported a history of emotional abuse, 40 (6.0%) reported physical abuse, 57 (8.8%) reported sexual abuse, and 47 (7.0%) had a family history of substance use (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

| Variables | Categories | Frequencies | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substance user | User | 322 | 48.0 |

| Non-user | 349 | 52.0 | |

| Sex | Male | 546 | 81.4 |

| Female | 125 | 18.6 | |

| Marital status | Single | 388 | 57.8 |

| Married | 229 | 34.1 | |

| Divorced | 54 | 8.1 | |

| Educational level | Elementary | 92 | 13.7 |

| Secondary | 126 | 18.8 | |

| University student | 93 | 13.9 | |

| University degree | 360 | 53.7 | |

| Employment | Yes | 394 | 58.7 |

| No | 277 | 41.3 | |

| Living with family | Yes | 545 | 81.2 |

| No | 126 | 18.8 | |

| Smoking status | Smoker | 506 | 75.4 |

| Non-smoker | 165 | 24.6 | |

| Medical illness | Healthy | 561 | 83.6 |

| Not healthy | 110 | 16.4 | |

| Self-harm | Yes | 158 | 23.5 |

| No | 513 | 76.5 | |

| Psychiatric disorder | Borderline personality disorder | 41 | 6.1 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 76 | 11.3 | |

| Mood disorder | 205 | 30.6 | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 64 | 9.5 | |

| Anxiety disorder | 188 | 28.0 | |

| Psychotic disorder | 59 | 8.8 | |

| Substance use disorder | 38 | 5.7 | |

| Family history of substance use | Yes | 47 | 7.0 |

| No | 624 | 93.0 | |

| Emotional abuse | Yes | 148 | 22.1 |

| No | 523 | 77.9 | |

| Physical abuse | Yes | 40 | 6.0 |

| No | 631 | 94.0 | |

| Sexual abuse | Yes | 57 | 8.8 |

| No | 614 | 91.5 | |

| Age/years Mean ± SD | 32.45 ± 10.18 | ||

| Age of starting drug use Mean ± SD (n = 322) | 20.68 ± 6.25 | ||

| Substance | Single | 97 | 30.1 |

| Multiple | 225 | 69.9 |

Factors associated with substance use

Bivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2) revealed that substance use was 1.55 times more common in men than in women. Patients with an elementary- or secondary-level education had an OR of 5.07 compared with those with a university-level education. Additionally, patients without a job, a history of self-harm, or a family history of substance use had ORs of 2.01, 4.29, and 3.43, respectively. The highest correlation with drug use was observed among smokers, with an OR of 7.22. Individuals who experienced emotional abuse had an OR of 1.70, while those with a medical illness had an OR of 4.44, indicating a higher likelihood of engaging in substance use.

Table 2.

Binary logistic regression results of factors associated with substance use

| Predictors | Bivariate binary logistic regression | Multiple binary logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | P-value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Male | 1.55 | 1.04–2.30 | 0.030 | 1.84 | 1.08–3.13 | 0.025 |

| Age (years) | 0.98 | 0.96–0.99 | 0.006 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Divorced | 1.0 | < .001 | 1.0 | < 0.001 | ||

| Single | 0.51 | 0.28–0.94 | 0.030 | 0.24 | 0.11–0.52 | < 0.001 |

| Married | 0.25 | 0.13–0.47 | < 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.09–0.40 | < 0.001 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| University degree | 1.0 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | 0.033 | ||

| Elementary | 5.07 | 3.04–8.47 | < 0.001 | 2.66 | 1.36–5.20 | 0.004 |

| Secondary | 2.39 | 1.58–3.61 | < 0.001 | 1.50 | 0.88–2.54 | 0.134 |

| University student | 1.02 | 0.79–1.32 | 0.887 | 1.29 | 0.68–2.43 | 0.431 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Yes | 1.0 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 2.01 | 1.47–2.74 | 2.99 | 1.71–5.25 | ||

| Self-harm | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4.29 | 2.88–6.38 | 3.53 | 2.07–6.03 | ||

| Family history of substance use | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3.43 | 1.75–6.72 | 4.04 | 1.84–8.87 | ||

| Smoking behaviour | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 4.98–9.63 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | < 0.001 | |

| Yes | 7.22 | 5.99 | 2.12–10.96 | |||

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||||

| Substance use disorder | 1.0 | < .001 | 1.0 | < .001 | ||

| Borderline personality disorder | 0.23 | 0.07–0.77 | .017 | 0.25 | 0.06–1.02 | .054 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 4.35 | 0.76–24.93 | .099 | 3.87 | 0.64–23.55 | .142 |

| Mood disorder | 0.07 | 0.22–0.19 | < .001 | 0.07 | 0.02–0.24 | < .001 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 0.13 | 0.04–0.42 | < .001 | 0.14 | 0.04–0.48 | .002 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.06 | 0.02–0.17 | < .001 | 0.08 | 0.03–0.26 | < .001 |

| Psychotic disorder | 0.06 | 0.02–0.17 | < .001 | 0.06 | 0.02–0.21 | < .001 |

| Emotional abuse | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.005 | 1.0 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1.70 | 1.17–2.47 | 3.56 | 2.1–6.05 | ||

| Medical illness | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | 0.011 | ||

| Yes | 4.44 | 3.17–6.21 | 2.1 | 1.18–3.58 | ||

| Physical abuse | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.217 | ||||

| Yes | 1.50 | 0.79–2.87 | ||||

| Sexual abuse | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.200 | ||||

| Yes | 1.43 | 0.83–2.47 | ||||

| Living with family | ||||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.280 | ||||

| No | 0.81 | 0.55–1.19 | ||||

Conversely, older patients, both single and married, had lower probabilities of drug use than did younger and divorced patients, with ORs of 0.98, 0.51, and 0.25, respectively. Living alone and being subjected to physical and sexual abuse did not show a significant correlation with substance use; therefore, these variables were excluded from the subsequent model.

In the backward multiple binary logistic regression, male sex, a primary level of education, and unemployment were factors associated with a higher likelihood of substance use, with ORs of 1.84, 2.66, and 3.53, respectively. Patients who self-harmed, had a family history of substance use, and were smokers also exhibited an increased likelihood of substance use, with ORs of 3.53, 4.04, and 5.99, respectively.

Furthermore, the bivariate analysis demonstrated a significant association between age and substance use. However, when age was included in the multiple binary logistic regression model, it no longer remained significant (p > 0.05).

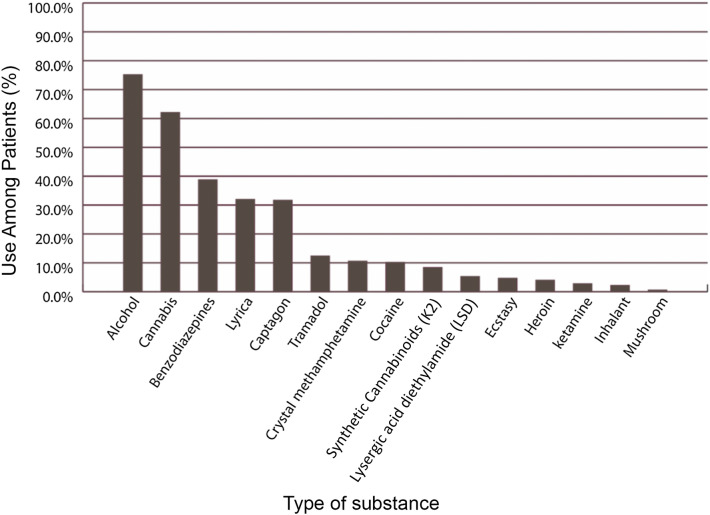

Use of multiple psychoactive substances among patients with psychiatric disorders

The use of a variety of substances was examined, and the subsequent multiple response analysis revealed the prevalence of the use of each substance. The most commonly used substances were alcohol (75.2%), followed by cannabis (62.1%) and benzodiazepines (38.8%). Conversely, the least frequently consumed substances were ketamine (2.8%), inhalants (2.2%), and mushrooms (0.6%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The use of multiple psychoactive substances among patients with psychiatric disorders

Multiple response analysis for substance use based on psychiatric disorders

The use of different types of substances was associated with different psychiatric disorders, with alcohol and cannabis being commonly used among individuals with various psychiatric disorders (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple response analysis for most substances used based on psychiatric disorders

| Psychiatric diagnosis | Cannabis | Captagon | Alcohol | Benzodiazepines | Cocaine | Ecstasy | Crystal meth | Tramal | Inhalants | LSD | Lyrica | Ketamine | Heroin | K2 | Mushrooms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borderline personality disorder | 13 | 4 | 24 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 48.2% | 14.8% | 88.9% | 48.0% | 7.4% | 3.7% | 3.7% | 7.4% | 0.0% | 3.7% | 22.2% | 3.7% | 3.7% | 3.7% | 0.0% | |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 53 | 37 | 52 | 36 | 10 | 5 | 17 | 16 | 3 | 5 | 37 | 3 | 6 | 14 | 1 |

| 71.6% | 50.0% | 70.3% | 48.6% | 13.5% | 6.8% | 23.0% | 21.6% | 4.1% | 6.8% | 50.0% | 4.1% | 8.1% | 18.9% | 1.4% | |

| Mood disorder | 35 | 11 | 50 | 22 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 48.6% | 15.3% | 69.4% | 30.6% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.9% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 1.4% | 1.4% | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 30 | 16 | 27 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 88.2% | 47.1% | 79.4% | 29.4% | 20.6% | 20.6% | 8.8% | 11.8% | 2.9% | 14.7% | 35.3% | 8.8% | 5.9% | 2.9% | 0.0% | |

| Anxiety disorder | 32 | 11 | 43 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 52.5% | 18.0% | 70.5% | 27.9% | 3.3% | 1.6% | 3.3% | 6.6% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 32.8% | 1.6% | 0.0% | 4.9% | 0.0% | |

| Psychotic disorder | 18 | 8 | 15 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| 90.0% | 40.0% | 75.0% | 45.0% | 15.0% | 0.0% | 25.0% | 15.0% | 5.0% | 5.0% | 30.0% | 0.0% | 5.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | |

| Substance use disorder | 19 | 15 | 31 | 18 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 55.9% | 44.1% | 91.2% | 52.9% | 17.6% | 2.9% | 17.6% | 17.6% | 2.9% | 5.9% | 29.4% | 2.9% | 2.9% | 5.9% | 0.0% |

Association between demographic factors and the use of one or more substances

The results of the bivariate binary logistic regression analysis (Table 4) revealed that men had a higher likelihood (OR = 2.63) of using multiple substances than did women. Additionally, older patients were less likely (OR = 0.95) to engage in the use of multiple substances compared with younger patients. Furthermore, individuals with an elementary-school educational level and those with a family history of substance use showed higher ORs (2.51 and 5.19, respectively) for using multiple psychoactive substances than did those with a university degree and no family history of substance use.

Table 4.

Association between demographic factors and the use of multiple substances using binary logistic regression analysis

| Predictors | Bivariate binary logistic regression | Multiple binary logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | 95% CI | P-value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1.0 | 0.002 | 1.0 | 0.048 | ||

| Male | 2.63 | 1.41–4.89 | 2.60 | 1.01–6.71 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.95 | 0.92–0.97 | < .001 | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | .006 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| University degree | 1.0 | 0.036 | ||||

| Elementary | 2.51 | 1.24–5.06 | 0.010 | |||

| Secondary | 1.18 | 0.65–2.17 | 0.583 | |||

| University student | 2.03 | 0.97–4.23 | 0.060 | |||

| Family history of substance use | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.008 | 1.0 | 0.005 | ||

| Yes | 5.19 | 1.55–17.40 | 6.06 | 1.71–21.45 | ||

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||||

| Substance use disorder | 1.0 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | < 0.001 | ||

| Borderline personality disorder | 0.61 | 0.21–1.82 | 0.378 | 0.85 | 0.19–3.74 | 0.834 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 2.97 | 1.03–8.56 | 0.044 | 2.00 | 0.66–6.03 | 0.221 |

| Mood disorder | 0.34 | 0.14–0.83 | 0.018 | 0.31 | 0.12–0.80 | 0.016 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 1.68 | 0.52–5.39 | 0.383 | 1.26 | 0.36–4.43 | 0.719 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.52 | 0.21–1.30 | 0.160 | 0.48 | 0.18–1.25 | 0.132 |

| Psychotic disorder | 3.24 | 0.62–16.83 | 0.162 | 2.41 | 0.50–12.99 | 0.305 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Divorced | 1.0 | 0.387 | ||||

| Single | 1.44 | 0.68–3.07 | 0.346 | |||

| Married | 0.66 | 0.29–1.50 | 0.325 | |||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.544 | ||||

| No | 1.16 | 0.72–1.87 | ||||

| Living with family | ||||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.854 | ||||

| No | 1.06 | 0.56–2.0 | ||||

| Self-harm | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.413 | ||||

| Yes | 1.23 | 0.75–2.04 | ||||

| Smoking behaviour | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.551 | ||||

| Yes | 2.33 | 0.14–37.69 | ||||

| Emotional abuse | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.122 | ||||

| Yes | 1.72 | 0.87–3.43 | ||||

| Physical abuse | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.367 | ||||

| Yes | 1.60 | 0.58–4.44 | ||||

| Sexual abuse | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.884 | ||||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.48–2.33 | ||||

| Medical illness | ||||||

| No | 1.0 | 0.377 | ||||

| Yes | 1.24 | 0.77–2.00 | ||||

In the multivariable logistic regression, men continued to exhibit a higher OR of using multiple substances than did women (OR = 2.60), while patients who were older or had mood disorders had lower odds of using multiple substances (OR = 0.96 and OR = 0.31, respectively). The strongest predictor for using multiple substances was found to be a family history of substance use (OR = 6.06). However, educational attainment was not a robust predictor of using multiple substances and was therefore excluded from the final model.

Discussion

Substance abuse among patients with psychiatric disorders is an increasing concern in the Arab world, given the exposure of individuals and populations to diverse cultures and contemporary substances [5]. To gather information on the prevalence of substance use, the sociodemographic and clinical variables of the users, and the types of substances used, we conducted this study on substance use among patients with psychiatric disorders in Amman, Jordan. It is worth noting that the prevalence of drug abuse in the Arab world appears to be lower than that in Western countries [17].

The present findings support those of earlier clinical investigations indicating that men are more likely than women to engage in substance use [16]. According to a biopsychosocial model, men tend to participate in hazardous activities more frequently, have easier access to substances, and experience less social stigma. In our study, substance users were found to be younger than non-users, which aligns with global research findings [17]. Therefore, young male patients with psychiatric disorders are at a higher risk of substance-related problems, as observed in similar studies conducted in South London [3, 5, 10].

Our study also identified a significant association between limited educational attainment and the prevalence of substance use, consistent with the results of a study conducted in the United States [18]. These findings support the hypothesis that education serves as a protective factor against substance abuse and that substance use may negatively impact academic motivation [19].

Furthermore, our study revealed an association between unemployment and substance use, which aligns with international research findings [20]. This could be attributed to unemployed individuals using substances as a coping mechanism for dealing with unemployment. Moreover, substance users may experience a greater burden of mental illness symptoms, which could contribute to their unemployment.

Having a family history of substance use was significantly associated with substance use in our study, consistent with the findings of research conducted at a rehabilitation centre in Ahmedabad, India [21]. Strong evidence suggests that family history plays a role in substance use [22, 23], influenced by both genetic and environmental factors [24]. Social factors are also associated with an increased risk of substance abuse [25]. Our research further revealed that patients who experienced emotional maltreatment were more likely to engage in substance use.

In our study, similar to the findings of a report from the United Kingdom and North America, the most commonly used substance among patients with psychiatric disorders was alcohol [26, 27]. However, this finding contradicts the pattern observed in the rest of the world, as Arab countries tend to have lower rates of alcohol use and alcohol use disorders, with higher rates of lifelong abstainers (94.9%) [28]. Conversely, our study demonstrated that alcohol was the most used substance among our cohort of patients with psychiatric disorders. In Arab countries where alcohol is legal, individuals with substance use issues frequently abuse alcohol, as observed in the United Arab Emirates [29, 30] and Lebanon [31]. This discrepancy highlights the unique cultural and social factors that contribute to substance use patterns in different regions.

Worldwide data have shown that cannabis is the most commonly used illicit substance [32], which is in line with our findings. Specifically, among patients with psychosis, we found that cannabis was the most commonly used substance, which is consistent with findings from other studies [33–35]. The relationship between cannabis use and psychosis is significant. It is likely a complex, multidirectional relationship, and the precise mechanisms are still a matter of debate [36].

We also found that the prevalence of opiate use and its association with psychiatric disorders were lower and weaker, respectively, compared with those of other substances. This is consistent with findings from other studies. For instance, a Swedish study by Dalmau et al. [37] reported a comorbidity rate of less than 6%. However, it is noteworthy that the comorbidity rate of mixed opiate abusers significantly increases when alcohol abuse is present [13].

The existing research suggests that the prevalence of substance abuse varies among Arab countries, although there is a concerning prevalence of polysubstance use [38]. Similarly, in our study, most patients were polysubstance users (69.6%), with alcohol (75.2%), cannabis (62.1%), and benzodiazepines (38.8%) being the most commonly used substances. It is important to note that polysubstance use poses unique risks in terms of substance interactions and can impact the effectiveness of substance use disorder treatments. Individuals may engage in polysubstance use to mitigate the adverse effects of one substance by another, to enhance the effects of a substance, or due to the availability of different substances [38].

The research findings have significant clinical implications. Systematic screening for substance use in psychiatric patients is essential, it is also important to address comorbidities in treating patients with substance use. Implementing early preventive strategies for substance use in all environments, in addition to educational initiatives highlighting the risks associated with substance use. The consideration of abuse or addiction should precede the prescription of drugs such as benzodiazepines, tramadol, or pregabalin, among other substances, by medical practitioners. This research also emphasises the need of implementing substance use awareness programs, systematic screening, early detection, and suitable treatment of substance use in patients with mental illness.

Limitations

The study has some limitations that should be considered. First, the data used in this study were self-reported, which may introduce bias and inaccuracies. Additionally, the study focused on a specific population and may not be representative of substance use patterns in other demographics or regions.

Conclusions

The available literature on substance use and abuse in Arab countries is currently limited. However, among patients with psychiatric disorders, our findings indicate that substance use is more prevalent among certain demographic groups, specifically young, unemployed men with a low level of education and a family history of substance use. These findings highlight the need for further research in diverse settings and populations to better understand the scope and underlying factors contributing to substance use in Arab countries. Additionally, targeted interventions and prevention strategies should be developed to address the specific needs of these high-risk groups and reduce the burden of substance abuse in these communities.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- OR

odds ratio

- SCID-5

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5

Author contributions

Research idea, material preparation, data collection and analysis, and writing the first draft of the manuscript were performed by Layali N Abbasi. Tewfik K Daradkeh, Mohamed ElWasify, and Sanad Abassy performed data analysis and reviewed and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Data is available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Al-Balqa Applied University (1069/1/3/26). All the participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Katz G, Durst R, Shufman E, Bar-Hamburger R, Grunhaus L. Substance abuse in hospitalized psychiatric patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:672–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trivedi C, Desai R, Rafael J, et al. Prevalence of substance use disorder among young adults hospitalized in the US hospital: a decade of change. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317: 114913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alharbi FF, Alsubaie EG, Al-Surimi K. Substance Abuse in Arab World: Does It Matter and Where Are We? In: Laher I, editor. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 2371–98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie H, Roser M Drug use. OurWorldInData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/drug-use. 2019

- 6.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2016) Results from the 2015 National survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. substance abuse and mental health services administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.pdf. [PubMed]

- 7.Salamoun MM, Karam AN, Okasha TA, Atassi L, Mneimneh ZN, Karam EG. Epidemiologic assessment of substance use in the Arab world. Arab Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;19:100–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweileh WM, Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sawalha AF. Substance use disorders in Arab countries: research activity and bibliometric analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2014;9:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menezes PR, Johnson S, Thornicroft G, et al. Drug and alcohol problems among individuals with severe mental illness in South London. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt GE, Malhi GS, Cleary M, Lai HM, Sitharthan T. Comorbidity of bipolar and substance use disorders in national surveys of general populations, 1990–2015: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guy N, Newton-Howes G, Ford H, Williman J, Foulds J. The prevalence of comorbid alcohol use disorder in the presence of personality disorder: systematic review and explanatory modelling. Personal Ment Health. 2018;12:216–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt GE, Large MM, Cleary M, Lai HMX, Saunders JB. Prevalence of comorbid substance use in schizophrenia spectrum disorders in community and clinical settings, 1990–2017: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;191:234–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merrick TT, Louie E, Cleary M, et al. A systematic review of the perceptions and attitudes of mental health nurses towards alcohol and other drug use in mental health clients. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2022;31:1373–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rush B, Koegl CJ. Prevalence and profile of people with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders within a comprehensive mental health system. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:810–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toftdahl NG, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Prevalence of substance use disorders in psychiatric patients: a nationwide Danish population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messer T, Lammers G, Müller-Siecheneder F, Schmidt RF, Latifi S. Substance abuse in patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:338–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, et al. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008;5: e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor (MI): Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynskey M, Hall W. The effects of adolescent cannabis use on educational attainment: a review. Addiction. 2009;95:1621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, Finger MS. Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:350–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadri AM, Bhagyalaxmi A, Kedia G. A study of socio-demographic profile of substance abusers attending a de-addiction center in Ahmedabad City. Indian J Community Med. 2003;28:74–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merikangas KR, Stolar M, Stevens DE, et al. Familial transmission of substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:973–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bierut LJ, Dinwiddie SH, Begleiter H, et al. Familial transmission of substance dependence: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and habitual smoking: a report from the collaborative study on the genetics of alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:982–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:106–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict Behav. 2012;37:747–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall EJ. Adolescent alcohol use: risks and consequences. Alcohol. 2014;49:160–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy SJ, Williams JF, Ryan SA, et al. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138: e20161211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Dhaheri F. A 10 year retrospective study of the National Rehabilitation Center, Abu Dhabi: trends, population characteristics, associations and predictors of treatment outcomes [dissertation]. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alblooshi H, Hulse GK, El Kashef A, et al. The pattern of substance use disorder in the united arab emirates in 2015: results of a national rehabilitation centre cohort study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2016;11:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karam EG, Yabroudi PF, Melhem NM. Comorbidity of substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders in acute general psychiatric admissions: a study from Lebanon. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43:463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report 2020 Other drug policy issues. New York: United Nations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green AI. Treatment of schizophrenia and comorbid substance abuse: pharmacologic approaches. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green AI, Brown ES. Comorbid schizophrenia and substance abuse. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67: e08. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wittchen HU, Fröhlich C, Behrendt S, et al. Cannabis use and cannabis use disorders and their relationship to mental disorders: a 10-year prospective-longitudinal community study in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright A, Cather C, Gilman J, Evins AE. The changing legal landscape of cannabis use and its role in youth-onset psychosis. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2020;29:145–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalmau A, Bergman B, Brismar B. Psychotic disorders among inpatients with abuse of cannabis, amphetamine and opiates. do dopaminergic stimulants facilitate psychiatric illness. Eur Psychiatry. 1999;14:366–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Guazzelli Williamson V, Setlow B, Cottler LB, Knackstedt LA. The importance of considering polysubstance use: lessons from cocaine research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;192:16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.