Abstract

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive neuromodulation technique to activate or inhibit the activity of neurons, and thereby regulate their excitability. This technique has demonstrated potential in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as depression. However, the effect of TMS on neurons with different severity of depression is still unclear, limiting the development of efficient and personalized clinical application parameters. In this study, a multi-scale computational model was developed to investigate and quantify the differences in neuronal responses to TMS with different degrees of depression. The microscale neuronal models we constructed represent the hippocampal CA1 region in rats under normal conditions and with varying severities of depression (mild, moderate, and major depressive disorder). These models were then coupled to a macroscopic TMS-induced E-Fields model of a rat head comprising multiple types of tissue. Our results demonstrate alterations in neuronal membrane potential and calcium concentration across varying levels of depression severity. As depression severity increases, the peak membrane potential and polarization degree of neuronal soma and dendrites gradually decline, while the peak calcium concentration decreases and the peak arrival time prolongs. Concurrently, the electric fields thresholds and amplification coefficient gradually rise, indicating an increasing difficulty in activating neurons with depression. This study offers novel insights into the mechanisms of magnetic stimulation in depression treatment using multi-scale computational models. It underscores the importance of considering depression severity in treatment strategies, promising to optimize TMS therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: Transcranial magnetic stimulation, Multi-scale computational modeling, Depression, Morphological neuron

Introduction

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive technique for neurostimulation and neuromodulation that generates sufficient electric fields (E-Fields) within the cerebral cortex to either activate or inhibit neurons, thereby modulating their excitability. This method has proven effective in treating a variety of clinical neuropsychiatric conditions such as depression, schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, among others (Olsson et al. 2023; Slomski 2018). However, the efficacy of current TMS protocols for depression is often limited due to the use of standardized stimulation settings, complicating the prediction of individual responses to treatment (Balwant 2022; Deng et al. 2023; Gogulski et al. 2022). The variability in treatment outcomes can be attributed to several factors, including differences in individual brain anatomy, the neurophysiological status of patients, and the complexity of stimulus parameters, particularly given the heterogeneity of depression. These factors obstruct our understanding of the interactions between magnetically induced E-Fields and neuronal activity, as well as the development of tailored modulation strategies. Nonetheless, direct monitoring of the activity within the targeted brain regions and neurons during stimulation could greatly enhance our comprehension of TMS effects and facilitate the creation of personalized therapeutic approaches.

To address this limitation, computational modeling serves as a supplementary method to experiments, facilitating the investigation of the biophysical mechanisms underlying TMS. Prior studies have employed the finite element method (FEM) alongside a three-dimensional brain model derived from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data (Zhang et al. 2022). This approach has enabled a visual representation of the spatial distribution of E-Fields induced by TMS (Boayue et al. 2018; Lioumis et al. 2018; Soldati et al. 2018; Van Hoornweder et al. 2022). These models have provided substantial evidence critical for elucidating the mechanisms of magnetic field influence on brain activity under controlled experimental conditions, including the selection of stimulation parameters and assessments of safety for pregnant women and medical professionals (Ahn et al. 2021; Gomez et al. 2021; Weise et al. 2023a). Given that magnetic-induced E-Fields can cause neuron membrane depolarization (Chung et al. 2022; Shirinpour et al. 2021a; Turi et al. 2022), the activation sites may be influenced by the characteristics of the activated neurons as well as by the distribution of the E-Fields. Describing the E-Fields activation in neurons induced by a magnetic coil verbally remains challenging (Angulakshmi et al. 2019; Dolz et al. 2015; Khairandish et al. 2022). To address this, neuron models have been developed to simulate the neuronal response to magnetic fields, including the sites where TMS initiates action potentials and the influence of cellular morphology. However, single-scale models lack comprehensive descriptions of the TMS-induced effects, thus offering limited insights into the neural activation mechanisms of TMS (Caredda et al. 2021; Wischhusen et al. 2019). Consequently, a multi-scale approach that incorporates realistic biophysical modeling of E-Fields in conjunction with neuronal membranes is essential for accurately quantifying the impact of the magnetic field on neurons (Dequidt et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2021).

Multi-scale models that integrate anatomically precise E-Fields with morphologically accurate neurons facilitate the simulation of neuronal responses to pulse stimulation. A plethora of established models exists that explore the interaction between E-field and neuronal models, particularly focusing on the activation sites of TMS, coil rotation, and waveform dynamics (Aberra et al. 2023; Yu et al. 2023). These models predominantly consider the physiological rather than pathological state of neurons. Relevant biological studies on depression have demonstrated that chronic stress can trigger the onset of depression, which subsequently leads to hippocampal atrophy accounting for up to 20% of its original volume. Furthermore, this atrophy is observed to worsen as the progression of depression (Lee et al. 2002). The primary contributing factors have been identified as neuronal atrophy and neuroglial damage, where the timeline of neuronal shrinkage coincides with the reduction in hippocampal volume (Banasr et al. 2007). Prolonged stress may result in significant neuroanatomical changes, such as a reduction in the number of dendrites and synapses, dendritic atrophy within the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex, and a decrease in the size and number of glial cells. (Ding et al. 2020; Rădulescu et al. 2021). It has been observed that long-term, mild, unpredictable stress alters the density of dendritic spines in the CA1 pyramidal neurons of the rat hippocampus, with a corresponding decrease as stress duration extends (Sancho-Balsells et al. 2023; Wu et al. 2023). Furthermore, studies indicate that both short-term and long-term unpredictable chronic mild stress protocols adversely affect neuronal integrity. Notably, neuronal atrophy has been recorded in the dorsolateral hippocampus of male subjects following two weeks of continuous stress exposure (Gaspar et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2022). Depression-related neuronal atrophy significantly impacts critical morphological characteristics, including dendritic diameter, branching, and length. These morphological attributes crucially influence neuronal polarization and discharge behavior under electromagnetic stimulation (Ju et al. 2023; Kaboodvand et al. 2023). Consequently, applying TMS with identical parameters may not produce consistent outcomes across patients with varying degrees of depression. Nevertheless, the differential response of neurons to magnetic field modulation based on depression severity remains unaddressed in existing models.

To investigate the response of neurons across varying degrees of depression to TMS, we employed computational neuro-modeling techniques to directly monitor the integrated activity of target brain regions and neurons during stimulation. These techniques incorporated characteristics associated with depression to construct a multi-scale model of induced E-Fields and neuronal coupling in the brain, which quantifies the impact of induced E-Fields on macroscopic field distribution and neuronal activity. Initially, we developed a biophysically detailed model of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus, incorporating morphological changes associated with depression. And then a comprehensive head model was established using MRI data, which facilitated the simulation of induced E-Fields in the brain via TMS. These models were integrated to simulate the neuronal responses of external E-Fields and delineate the biophysical impact of TMS on neurons exhibiting varying degrees of depression. Our numerical simulation results revealed that the peak membrane potentials and polarization of neurons progressively decrease with the severity of depression increases. The peak concentrations of calcium ions also experience a delay in reaching their peaks with a corresponding reduction in magnitude. This trend is consistent across simulations of neurons with different coupling intensities. Furthermore, the E-Fields thresholds for neuronal activation and the E-Fields amplification factor increase, leading to the activation of these neurons more challenging. Thus, devising a targeted magnetic field intensity adjustment strategy based on the patient's degree of depression is crucial. Oure study provides a novel insight into the modulation mechanisms involved in TMS treatment for depression.

Methods

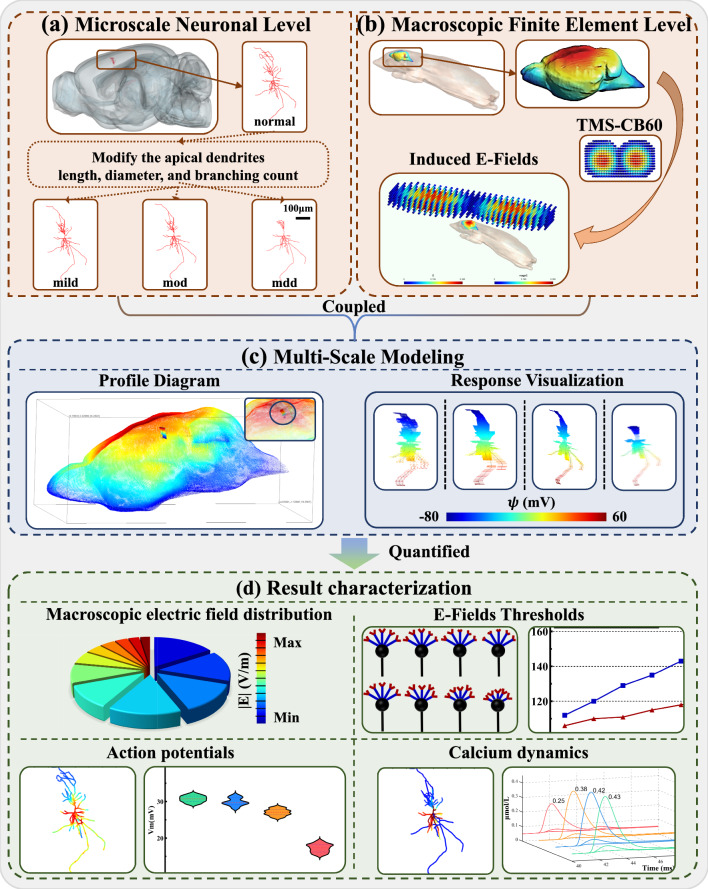

To investigate the mechanisms of action of TMS on the nervous system, we developed a multi-scale computational model that integrates a highly detailed hippocampal pyramidal neuron model with the E-Fields induced in a three-dimensional rat head model (see Fig. 1). By incorporating morphologically accurate hippocampal pyramidal neurons into the three-dimensional rat head model, we assessed the specific effects of E-Fields on different neuronal types. Neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region were categorized as normal, mild, moderate, and severe with the severity of depression, respectively. And thereby the model in our study can accurately simulate the response of individual neurons to TMS from the cellular to the brain region level, including macroscopic E-Fields distribution, action potentials, calcium dynamics, and E-Fields thresholds.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of overall scheme. a Microscale Neuronal Level. b Macroscopic Finite Element Level. c Multi-Scale Modeling. d Result characterization

Morphological neuron modeling with depressive characteristics

In this study, we utilized the NEURON simulation software to construct a detailed morphological model of a pyramidal cell in the hippocampal region (Carnevale 2007), specifically from CA1 of a rat brain. The selection of this particular model was informed by the microstructural characteristics of an actual pyramidal cell from the hippocampus CA1, incorporating precise representations of axonal and dendritic morphologies. Further elaboration of this model enabled the simulation of action potential generation and propagation under conditions of varying degrees of depression severity.

To elaborate, CA1 pyramidal cells were meticulously reconstructed in NEURON, reflecting the dendritic atrophy observed in neuronal cells afflicted by depression, as depicted in Fig. 2a. Additionally, a simplified neuronal model, shown in Fig. 2b, was employed to provide a comprehensive visualization of the neuronal components, including the soma, axon, and both proximal and distal dendrites. Adjustments to the apical dendritic morphology of the neuronal models were classified into four distinct groups—normal, mild, mod, and mdd—based on variations in dendritic diameter, branching complexity, and length, as demonstrated in Fig. 2c.

Fig. 2.

The reconstruction process of morphologically realistic neuronal models. a Morphological differences between normal neurons and neurons with depression. b Components of a simplified neuron. c Adjustments made to the apical dendritic morphology of the simplified neuron model. d Morphological representation of four types of neurons

Figure 2d illustrates the morphological alterations in the reconstructed neurons corresponding to each category of depression severity, with modifications clearly marked using light purple circles and purple-outlined rectangles. This approach facilitated precise recording of the compartment-specific responses to TMS. Detailed data were collected on the electromotive force generated by each neuronal compartment, including the initiation site of action potentials, the dynamic changes in membrane potential, and the velocity of back-propagating action potentials (bpAPs). This high-resolution, biophysical-based model effectively captures the direct responses of hippocampal neurons to TMS, highlighting the model's depth and diversity.

Anatomical rat head model and E-Fields simulation

The head model derived from MRI was segmented into compartments representing skin, skull, gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, a total of 5 tissues, and body fluids. To study the effect of non-invasive brain stimulation on neurons, we start by calculating the E-Fields generated at the macroscopic level using the head model. In this study, the simulation was performed using the dual-coil TMS coil CB60 parameters from MagVenture (Denmark). The stimulating coil was placed 4 mm from the skull and held tangentially to the skull with the coil handle pointing backward. This involves determining the spatial distribution and temporal evolution of the TMS E-Fields. Since the stimulation frequency is relatively low, the quasi-static approximation was used to separate the spatial and temporal components of the E-Fields (Windhoff et al. 2013). Under the quasi-static assumption, the temporal variation of the induced E-Fields in TMS is equivalent to the change in TMS stimulation output (rate of change of coil current [dI/dt]), in this experiment, dI/dt = 1 A/μs. Once the spatial distribution of the E-Fields is determined, the E-Fields at any given time can be obtained by scaling the spatial distribution with the TMS waveform. For the spatial component, we calculated TMS-induced E-Fields using FEM models implemented in the open-source software SimNIBS (Shirinpour et al. 2021b). During TMS stimulation, a magnetic field is created through the coil by the electric current (Rosado 2022), by the following Bio-Savart Law:

| 1 |

where B is the magnetic field, S is the vector location, µ0 is the magnetic constant, C is the route of current I. This equation is used to calculate the magnetic field B at location S in three-dimensional space, generated by the electric current I.

Then, the magnetic field was computed to the E-Fields using Maxwell-Faraday equations:

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

where E is the solution of the equation. Note that I is the current in empty space, which is constant, and div(E) = 0 in empty space.

Coupling E-Fields to neuron model

In this research, macroscopic E-Fields generated by magnetic stimulation were computed within a FEM. These fields were then integrated with a neuronal model, with an assumption that the induced E-Fields were spatially uniform and the stimulus conformed to a simplistic pulse configuration. It is important to note that while neurons inherently produce E-Fields, such fields are insubstantial when juxtaposed with the robust fields induced by TMS. For the purposes of simulation, coordinates of neuronal compartments from the NEURON software were exported and subsequently incorporated into MATLAB, where they were aligned with the FEM-generated E-Fields. Neurons were manually positioned at specified locations and depths within the head model, which was adjusted to reflect the complex geometry of the hippocampus.

Incorporation of neurons into this model involved adapting the head model to accommodate the hippocampal structure, particularly within the CA1 region. The multi-scale modeling approach facilitated the injection of mesoscopic E-Fields from the FEM into the microscopic E-Fields within the neuronal compartments. This setup enabled the simulation of membrane potential changes in response to magnetic stimulation by applying an external current in the NEURON model. The final stage involved embedding these neurons within a realistically modeled hippocampus CA1 section of a rat head in the FEM. The quasi-potentials across all compartments were calculated, and data were captured for subsequent simulation use in NEURON.

Upon successful integration of neurons with the FEM models, simulations of neuronal responses to TMS commenced. These simulations utilized the NEURON-generated models, quasi-potentials, and TMS waveform files. The methodology provided an option to either employ previously calculated quasi-potential files or to proceed with a uniform E-Fields. The simulation outputs, including voltage traces and connectivity coordinates of neuronal segments, were systematically generated. This study further engaged existing experimental data to corroborate the accuracy of the model, employing a simplified biophysical representation of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. This integration was instrumental in simulating the morphological responses of various CA1 neuronal types to TMS, thereby enhancing our understanding of cellular dynamics under such stimulation.

Computation of neuronal activation induced by E-Fields

We then calculate the E-Fields activation on neurons induced by the TMS coil. The following description can compute the quasi-potentials:

| 6 |

where is the E-Fields, is the displacement vector, , and stand for the Cartesian components of the E-Fields, and x, y, and z denote the Cartesian coordinates of each compartment. This step is computed in NEURON simulation software. Regardless of whether the E-Fields is uniform or based on the FEM model, the quasipotentials are calculated at each neuron segment. Furthermore, there is a proportional relationship between the strength of the magnetic field and the strength of the E-Fields.

The quasipotentials as current sources in the Hodgkin-Huxley cable equation, where the current source passes through the plasma membrane, and the current is linked to the quasi-potential as follows:

| 7 |

and in the Hodgkin-Huxley model, this would manifest as another source term:

| 8 |

where represents ionic current. In neurons, ionic current refers to the flow of different ions (such as sodium, potassium, chloride, etc.) across the neuronal membrane, generating an electric current. These ions typically flow through ion channels, which are unevenly distributed across the neuronal membrane and can be regulated by opening or closing the channels. represents any external current applied to the neuron. is synaptic current, which is the current generated at synapses due to the release of neurotransmitters.

The axon is the first to respond when the external E-Fields stimulates a neuron. By integrating the scalar component of the E-Fields along the axon's path, the potential difference between two points on the axon is calculated. At the onset of the pulse, the distribution of electric potential along the axon can be expressed as:

| 9 |

In this equation, represents the potential along the axon, is the scalar component of the E-Fields, is the initial voltage of the pulse, is the width of the unit pulse, is the number of turns in the coil, is the radius of the coil, and are coordinates along the axon's path.

In NEURON simulations, we approximate the membrane potential of the neuronal system by utilizing the voltage at the midpoint of each compartment. In the presence of uniform E-Fields, the potential at each extracellular node j (i.e., ) is determined through a specific method:

| 10 |

In this context, the distance from node to the cathode is represented by . In this scenario, the extracellular potential exhibits a linear decrease along the y-axis while remaining constant along the x-axis. Notably, the influence along the z-axis is disregarded as there is no E-Fields component in that direction. According to Eq. (10), the extracellular potential difference between compartments and can be expressed as follows:

| 11 |

Here, Δl signifies the distance between two adjacent compartments, and γ denotes the angle between the neuronal element and the y-axis.

In addition, we conducted a simulation experiment on calcium ions within neurons, revealing that only trace amounts of calcium ions can reach the neuron's proximal dendrites. This is because calcium ions maintain a high concentration near the soma and do not diffuse to all dendrites that are far from the soma. The diffusion equation describes the migration of calcium in the cyapicallasm:

| 12 |

where is a vector representing the calcium concentration in the cytosol, considering spatial coordinate x and time t. Therefore, it can describe the distribution of calcium ions at different locations and time points within the cyapicallasm. represents the charged state of calcium ions and is a component of , used to indicate the concentration of calcium ions in the cytosol. Simultaneously, calbindin-D28k, as a protein, may regulate the intracellular calcium ion concentration. Its interaction with calcium ions can influence their distribution and concentration within the cell. The interaction between cytosolic calcium and calbindin-D28k is described as follows:

| 13 |

This mentions two rate constants, and . For the sake of simplicity, the expansion of terms is omitted, and the parameters used in this study refer to those in reference (Breit et al. 2018) and are used to describe the dynamics of interaction between calcium ions and calbindin-D28k. Calcium dynamics are modeled by applying a system containing diffusion–reaction equations on a one-dimensional tree structure involving three spatial coordinates. These equations explain the spread of substances in space and their reactions with other substances, potentially reflecting a dynamic model of calcium ion diffusion and interaction with calbindin-D28k in the cyapicallasm. This provides crucial information for understanding the regulation of intracellular calcium ions.

| 14 |

| 15 |

The variance between the total concentration defines compound's concentration () and the free concentration in the cytosol. Assuming constant total concentration across space and time, this implies that free calcium ions and share comparable diffusive properties. Free denotes not bound to calcium ions, whereas total encompasses all within the cytosol, irrespective of its binding status with calcium ions.

Results

Macroscopic E-Fields distribution in rat brain

Figure 3 shows the effects of a biphasic pulse stimulation delivered to the rat head using a CB60 coil on the rat hippocampal neuron model. TMS involves the delivery of transient currents through a coil to generate magnetic field, which can penetrate the skull and create E-Fields effect in the brain region, leading to neurons' depolarization. Figure 3a shows the placement of the coil on the head, targeting the hippocampus of the rat. The TMS-induced E-Fields in the grey matter is strongest in cortical and hippocampal areas (Fig. 3b). The color of the E-Fields maps represents the activation of the corresponding area. E-Fields maps use colors to indicate the activation level in the corresponding areas. Based on the overall range of E-Fields intensity, it is divided into 12 levels, and the E-Fields intensity increases progressively from blue to red, as shown in Fig. 3c. It's important to note that the classification of high and low E-Fields intensity is relative and may vary based on the E-Fields amplification factor. With the increasing of distance from the stimulus sit, the TMS-induced E-Fields in the brain gets weaker following an exponential function. Figure 3d illustrates the location relation between the E-Fields determined with the FEM and the neuron model. In this process, the hippocampal CA1 region of the rat has been stimulated by the E-Fields, resulting in the depolarization of neurons. Compared to culture cells and brain slices, our whole rat brain provided an authentic system to show the activity of the intact neurons. The activated pyramidal cell models with axons and dendrites are shown inside the transparent pial surface, including the four types of neurons from left to right: normal, mild, mod, and mdd.

Fig. 3.

Hippocampal neuron in FEM model of TMS induced E-Fields. a Transcranial magnetic coil stimulation in a rat model. b Macroscopic brain stimulation visualization. c Fan-shaped stimulation intensity chart. d Microscopic neuron stimulation visualization

The impact of TMS on neuronal membrane potential and bpAPs velocity

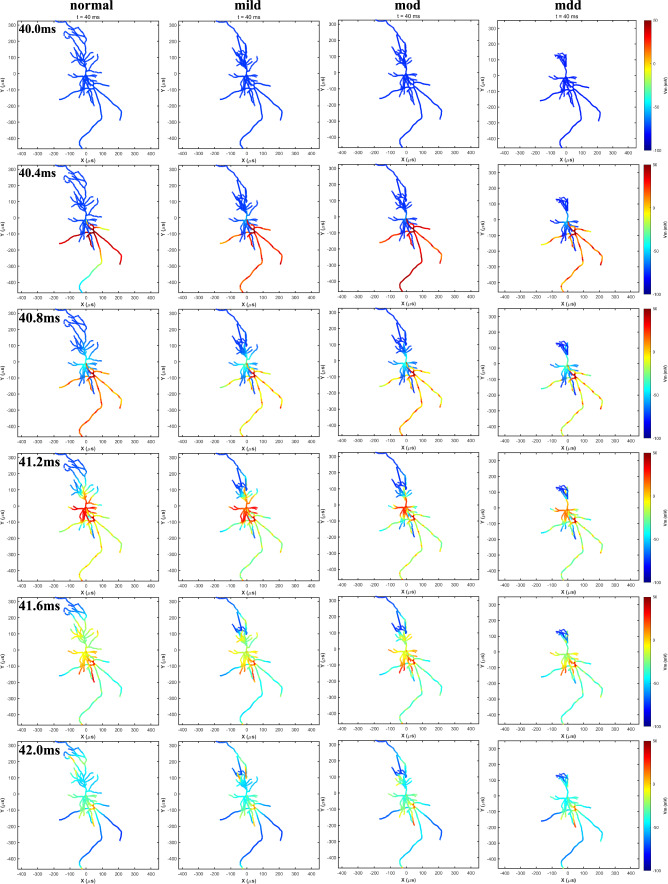

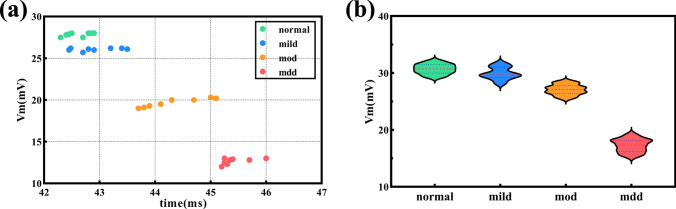

We use biophysical models of CA1 pyramidal cells with varying severity of depression to simulate the difference of neurons in response to TMS-induced E-Fields. Figure 4 illustrates the temporal membrane potential variations of four different types of neurons in response to a single TMS pulse. Membrane potential data were recorded at intervals of 0.4 ms during the period from 40.0 to 42.0 ms. In the initial scenario, the neuron is in a resting membrane potential state throughout the cell. At 40 ms, the magnetic pulse is executed. In the case of normal neuron, the axon terminal at the base of the cell is depolarized and then triggers an action potential. The action potential rapidly propagates to all axonal branches and reaches the soma approximately 1 ms later. Subsequently, dendrites gradually depolarize for their ion diffusion. It's worth noting that the shorter length of basal dendrites results in faster depolarization than apical dendrites. Approximately 4 ms later, the neuron gradually returns to the resting potential. Apical dendrites and small branches depolarize last and thus return to the resting state last. Unlike the normal neuron, it can be observed from the color map that the membrane potential of the neuronal soma and the degree of depolarization in the axon and dendrites decreases correspondingly with the increasing of depression degree. To clarify the differences in membrane potential among different types of neurons, we recorded the peak membrane potentials and their temporal patterns at 8 branching points on neuron dendrites, as depicted in Fig. 5a. These branching points were spaced at intervals of 20 μm, ranging from 20 to 160 μm away from the soma. It is evident that with the increasing severity of depressive symptoms, the peak action potential amplitude and propagation speed at dendritic branching points decrease. Furthermore, we obtained ten sets of peak membrane potential data for four types of neurons through coupled simulations. These neurons had the same coupling depth (1 mm from the gray matter surface) but differed in their specific coupling coordinates. We found that after applying TMS stimulation at 40 ms, the time range for peak potential occurrence was between 41 and 41.5 ms. It is worth noting that the peak membrane potential of neurons gradually decreases during the treatment with the same TMS stimulation parameters as the severity of depression increases (see Fig. 4b). Among these, the most significant decrease in membrane potential occurs in mdd.

Fig.4.

Time series of membrane potentials of four types of neurons during treatment with TMS-induced E-Fields

Fig. 5.

Membrane potential peaks and their temporal dynamics at dendritic branching points and neuronal soma of four distinct neuron types following TMS stimulation: a Dendritic branching points of neurons. b Neuronal soma

Furthermore, we meticulously documented the bpAPs velocity (Fig. 6a), delineating the propagation speed of dendritic bpAPs at varying distances from the soma across different severity of depression. Measurements were conducted in increments of 40 μm ranging from 20 to 300 μm. The result shows a discernible reduction in velocity with the increased severity of depression, notably evident in mdd, where complete propagation had not occurred even at the 4 4 ms. The research findings suggest a positive correlation between bpAPs velocity and dendritic diameter, indicating a gradual decline in retrograde action potential speed with escalating depression levels. In Fig. 6b, we delineate the spatial distribution of bpAPs peaks within a 2.6 ms timeframe under varying depression conditions. It is noteworthy that heightened depression levels correlate with a deceleration in the propagation of bpAPs peaks. Within 2.6 ms, dendritic bpAPs peaks in normal, mild, and mod depression neurons have already extended to 300 μm, while propagation has only reached 240 μm in mdd neurons. At the 180 μm mark lies the boundary between basal and apical dendrites, where it is noticeable that the propagation of bpAPs peaks in apical dendrites is slower.

Fig. 6.

The propagation velocity of action potentials varies with different severity levels of depressed neurons. a Time-varying graph of dendritic membrane potentials. b Relationship between dendritic bpAPs and distance for the four types of neurons

The impact of TMS on calcium dynamics

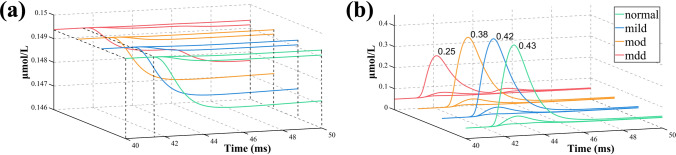

We simulated the calcium dynamics of the neuron compartmental model in response to the TMS-induced E-Fields. Figure 7 illustrates the temporal variations of soma calcium concentrations over time during a single biphasic TMS pulse for four types of neurons. Specifically, data were recorded with a time step of 0.1 ms from 41.8 to 42.3 ms to examine in detail the trends in calcium concentration during this time interval. The average delay between the voltage peak and calcium response is approximately 1.03 ms, indicating a short delay in the internal signal transmission of the neuron. Additionally, it is noteworthy that there exists a relatively high accumulation of calcium ions at the soma, nearly 1.3 µmol/L, and the value is 0.0925 µmol/L at the apical dendrite. This suggests that TMS has an immediate or delayed effect on neuronal and intracellular calcium activity. The soma has a stronger affinity for accumulating calcium ions, possibly due to its larger radius or volume. Compared to the typical neuron, the calcium concentration is relatively low in the volumetric regions of the dendrites. Calcium ions exhibit slow diffusion near the soma. The calcium signaling in normal neurons is higher than in depression neurons, especially neurons in mdd. There is a gradual decrease in calcium ion concentration with the increasing severity of depression at the same time. In the provided figure, the scale for depression ranges from 0.07 to 0.16 (on the right), while the scale for a normal state ranges from 0.06 to 0.16, resulting in a slightly darker appearance of the colors.

Fig. 7.

Time series of calcium ions of four types of neurons during treatment with TMS-induced E-Fields

Figure 8a depicts the temporal propagation of intracellular calcium-binding protein concentration induced by TMS, where calcium-binding proteins are a class of proteins that bind with calcium ions and regulate intracellular calcium concentration and signaling. As the severity of depression increases, an elongation in the reaction time of calcium-binding proteins is observed, measured as 41.7, 41.9, 42, and 42.05 ms, respectively. In this figure, there are three branches for the calcium-binding protein concentration of each type of neuron, representing the apical dendrites, basal dendrites, and soma, from top to bottom. Figure 8b illustrates the temporal propagation of cytosolic calcium ion levels during the treatment with TMS-induced E-Fields. The amplitude of calcium signals decreases, accompanied by prolonged reaction times in the depressed state with the severity of depression increases. For E-Fields-triggered behavior, the response of distal dendrites to the E-Fields is relatively limited compared to the soma. In the figure, there are three branches for the calcium ion concentration of each type of neuron, representing the soma, basal dendrites, and apical dendrites, from top to bottom.

Fig. 8.

Time series plots of soma calcium-binding protein and cytosolic calcium ion concentrations in four types of neurons: a Soma calcium-binding protein concentration. b Cytosolic calcium ion concentration

Furthermore, we investigated the effects of TMS-induced E-Fields at different coupling depths on the membrane potential and cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration of neurons. We set five different depths relative to the gray matter surface: 0.8, 0.85, 0.9, 0.95, and 1 mm. Figure 9a displays the peak membrane potentials of four types of neurons at various depths. When depth was varied, the time for the membrane potential of the same type of neuron to reach its peak gradually delayed, while the magnitude of the membrane potential remained relatively stable, fluctuating within ± 3 mV. On the contrary, as the level of depression changes, at the same coupling depth, the time required for the membrane potential of neurons to reach its peak gradually delays, accompanied by a gradual decrease in the peak amplitude. These findings are consistent with our previous experimental results (see Fig. 5). In studying the peak cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration of four types of neurons at different depths (see Fig. 9b), we found that as the coupling depth increased, the time for the cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration of the same type of neuron to reach its peak gradually delayed, while the magnitude of the peak concentration remained relatively stable. However, under the same coupling depth, the peak cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration in depressive states was lower compared to normal states. This finding is highly consistent with the data presented in Figs. 7 and 8.

Fig. 9.

The effects of different coupling depths on the peak membrane potential and calcium ion concentration of neurons: a peak membrane potential of neurons. b peak cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration

The impact of TMS on neuronal activation threshold

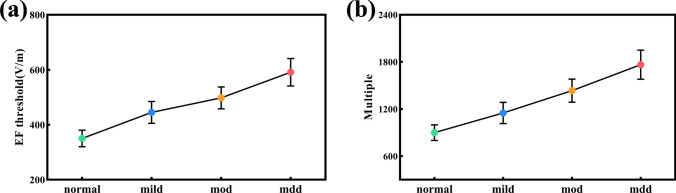

Gradually increasing the E-Fields amplification factor can determine the minimum voltage intensity required for a neuron to produce an action potential. This threshold stimulation intensity is referred to as the E-Fields threshold of the neuron. The current injection can roughly simulate the response of the whole-cell to TMS. We calculated E-Fields threshold of the action potential of the four types of neurons. It can be observed that both the E-Fields threshold gradually increases with an increase in the severity of depression (Fig. 10a). The E-Fields amplification factor is a crucial element within the multi-scale model, used to modulate the effects of the E-Fields. In multi-scale modeling, a distinctive feature lies in the capacity to fine-tune the E-Fields amplification factor during neuronal coupling. This precise adjustment allows for the effective activation of neurons and pinpoints their minimum value, which is known as the minimum E-Fields amplification factor (Escale). Figure 10b illustrates the required the Escale for neuron activation, indicating that Escale gradually increases with the increased severity of depression. Neurons with low current threshold are more susceptible to magnetic stimulation and need lower values of E-Fields amplification factor, which suggests that the activation of major depressive neurons may need to enhance TMS intensity.

Fig. 10.

The E-Fields threshold and E-Fields amplification factors of four types of neurons are presented as follows: a E-Fields threshold thresholds and b E-Fields amplification factors

The significant difference between normal and depressed neuron in morphology lies in the apical dendritic number, diameter, and length, as shown in Fig. 2a. To further investigate the role of dendrites in the impact of neuronal morphology on magnetic stimulation threshold, we modified the dendritic diameter, length as well as branch number connecting to the proximal dendrites, finding that a decrease in dendritic diameter, length, and quantity of all can led to an increase in the E-Fields threshold (Fig. 11). The E-Fields threshold was linearly correlated to the number of dendrites in this experiment.

Fig. 11.

The impact of neuronal morphology on the magnetic stimulation threshold: a dendritic diameter, b length, c branch number

Discussion

To evaluate the relationship between neuronal activity and the severity of depression, this study developed a multi-scale computational model, which includes a neuronal model characterized by depression-related morphological and electrophysiological properties, as well as a three-dimensional rat brain model incorporating induced E-Fields. This model expands upon the NeMo-TMS model by incorporating pathological characteristics of depression in neurons (Shirinpour et al. 2021a) and coupling the neuronal model to the hippocampus of the adult rat. Consequently, we were able to simulate the dynamic activity of neurons in response to electrical or magnetic field stimulation under conditions of depression. Our research represents the first exploration of the quantifiable effects produced on neurons by TMS across varying degrees of depression severity, deepening our understanding of changes in brain neuronal activity in depression following physical field intervention. Considering recent studies on the mechanisms by which TMS affects neural cells, our simulation results provide significant insights into the magnetic field-mediated mechanisms involved in depression.

Based on neurophysiological findings on depression (Banasr et al. 2021; Gaspar et al. 2022), the neuron models were modified to the type of normal, mild, mod, and mdd with depressive features by atrophy in neuronal dendrites. Numerical simulation results of our model show that the action potentials of all four types of neurons initiated from the axon terminals propagated to the soma, and finally spread to the dendrites, which agree with previous simulations and electrophysiological experiments, i.e. TMS-induced the activation of neurons primarily by somatic depolarization. It is particularly noteworthy that the significant difference among the four-type neuron is the peak membrane potential of neuronal cell bodies gradually decreases with the severity of depression increases (see Fig. 4). A prediction from our modeling was that the significant decrease in the membrane potential of neurons of mdd may be partially attributed to the most pronounced changes in the dendritic morphology of this type neurons. Previous simulations have shown that the changes in membrane potential are determined by the magnitude of the TMS-induced E-Fields gradient and the passive spatial constant of the axon fibers (Pashut et al. 2011). From this result, it can be inferred that the change of the morphological diameter of neurons alters the axial and membrane resistance, leading to the change of the spatial constant of neurons. This variation is expected to affect the induced E-Fields's contribution to a given compartment's membrane potential. Numerous depression studies in different species have confirmed neurophysiological changes in the brain. After chronic, unpredictable, mild stress, the neurons in mice generally exhibit hyperpolarization of membrane potential, and the resting membrane potential subsequently decreases. This may occur through activating calcium-dependent and calcium-independent potassium channels to reduce neuronal excitability (Fang et al. 2021). Other experimental studies using chronic unpredictable mild stress to establish rat model of depression show that mice exhibited reduced dendritic complexity, spine density, and fewer AMPA receptors in dendritic spines. During the Forced Swim Test, the activity of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region significantly decreased (Aguilar-Valles et al. 2021; Ma et al. 2021). These findings underscore that depression may affect neuronal electrophysiological properties through various mechanisms, decreasing membrane potential (Kim et al. 2022; Lei et al. 2020). The change makes activating action potentials in neurons using the same TMS parameters difficult.

Furthermore, this propagation mode of action potential initiating at the proximal axon region and propagating backward, named bpAPs, represents the typical feature of action potential propagation in the central nervous system of most mammals (Kotler et al. 2023; T. Pashut et al. 2014). The most significant difference between the four types of neurons is the average velocity of bpAPs gradually decrease with the severity of the neurons, as shown in Fig. 6. These simulations lead to a prediction that that the polarization of neuronal dendrites decreased with the increased severity of depression, which may be positively correlated with dendrite atrophy. A recent novel imaging experiment with primary cultures of hippocampus neurons has provided some support for the relationship between dendritic morphology and bpAPs. This elegant study reported that velocity and amplitude of bpAPs were positively correlated with dendritic diameter (Tian et al. 2022). It implies that as the degree of depression increases, the amplitude of action potentials propagating to dendrites decreases, and the polarization level of neuronal dendrites decreases, potentially to the point where action potentials may not be triggered. These changes suggest that dendrites of neurons with depression exhibit reduced responsiveness to stimuli, which may decrease neuronal excitability, thereby affecting neuronal function and information processing.

Our findings indicate that TMS leads to alterations in the membrane potential state and increases in Ca2+ levels, concurrently with a reduction in cytoplasmic calcium-binding proteins. The calcium dynamics of neuron in mdd significantly differ from those in normal neurons, exhibiting diminished amplitude and delayed responses (K. Ma et al. 2022). Compared to normal neurons, depressed neurons exhibit complex Ca2+ signaling under TMS due to morphological changes (Murphy et al. 2016). TMS enhances neuronal calcium responses, which in turn may influence molecular and structural changes related to neuronal function, such as survival, dendritic morphology, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release. The impact of TMS on intracellular calcium activity can be immediate or delayed. Our results support the hypothesis that the differential regulation of depression by TMS is partially related to changes in cellular morphology, potentially explaining the altered cellular morphology responses of depressed neurons to TMS. However, regarding the impact of magnetic stimulation on Ca2+ balance, evidence suggests that TMS in rat brains activates distal fibers leading to the activation of inhibitory neurons targeting dendrites in the cortex, thereby suppressing dendritic Ca2+ activity (Murphy et al. 2016). Given the complexity and diversity of TMS effects on neurons, it is unsurprising that the literature reports some inconsistencies in TMS-mediated modulation of neuronal or subcellular functions. Clinically, TMS is designed with specific temporal patterns to induce neuroplasticity, accompanied by transient or sustained changes in Ca2+ dynamics, neurotransmitter release, and protein expression. However, for individuals with depression, plasticity may be more challenging to occur at different levels from superstructures to brain networks, and these processes may be driven by changes in the release of intracellularly stored Ca2+ (Grehl et al. 2015). Furthermore, we also investigated the impact of TMS on neurons with varying coupling depths. We quantified trends in neuronal membrane potentials and calcium ion concentrations, which align with the trends observed in previous studies (refer to Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) (Banerjee et al. 2017; Weise et al. 2023b; Ye et al. 2015). These comparisons validate the efficacy of TMS in modulating neuronal activity and reveal subtle differences in its mechanisms of action, which may provide crucial theoretical support for further research in neuromodulation. However, the mechanism of the effect of TMS on calcium dynamics is still unclear, and future studies are expected to verify the difference in the response of morphological neurons to TMS in different severity of depression.

We conducted computational analyses to determine the activation threshold of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons under various states of depression when stimulated by external E-Fields. As depicted in Fig. 10a, the study assessed the responsiveness of four distinct morphological types of these neurons to E-Field stimulation. Findings indicate that the threshold for E-Field-induced neuronal action potentials escalates with increasing severity of depression. This escalation correlates with a reduction in the dendritic diameter, length, and branching. Consistent with earlier simulations (Tamar Pashut et al. 2011), our results suggest that reductions in dendritic dimensions elevate the magnetic threshold required for depolarization. This phenomenon likely results from the diminished capacity of smaller dendrites to mitigate the effects of magnetic pulses, thereby enhancing current escape and attenuating depolarization, as shown in Fig. 10b. Notably, the scaling factor for E-Fields (Escale) is substantially elevated in depressive states compared to normal conditions and intensifies as depression severity increases. Therefore, triggering neuronal action potentials in a depressive state necessitates a higher E-Field intensity. This requirement may explain the observed differences in the brain's and neurons' responses to TMS-induced exogenous E-Fields in patients with major depression (Ding et al. 2023; Yi et al. 2017).

Our model posits that the reduction in the number of distal dendrites in mdd neurons elevates the magnetic threshold required for stimulation. This observation appears to conflict with findings from a prior study (Tamar Pashut et al. 2011), which suggested that an increase in proximal dendrites connected to the soma decreases the magnetic threshold. The latter effect can be attributed to each additional dendrite acting as a current sink, thereby drawing current away from the soma. Consequently, it may be hypothesized that neurons with lower current thresholds could be activated at reduced magneto-stimulation MS intensities. Conversely, neurons exhibiting depressive phenotypes may necessitate higher intensity TMS for activation. Furthermore, as depression intensifies, neurons typically demonstrate a reduction in dendritic diameter, length, and branching (Gaspar et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023; Rădulescu et al. 2021), which in turn diminishes the efficacy of these structures as current sources, ultimately increasing the threshold for E-Fields-triggered action potentials (refer to Fig. 11) (Pagkalos et al. 2023; Tran-Van-Minh et al. 2015).

In this study, we verified significant changes in individual neurons influenced by TMS regarding membrane potential, intracellular calcium concentration, cytoplasmic calcium-binding proteins, and activation thresholds. Numerical simulations disclosed the profound impact of dendritic morphological alterations on neuronal activity, thereby underscoring the potential critical role of dendritic structures in treating depression with TMS. This investigation is the first to reveal the effects of magnetic stimulation on the fundamental cellular mechanisms of neurons in patients with varying degrees of depression, potentially involving synaptic, neural circuitry, and cellular environmental responses to TMS. Depression is a network-level disorder involving complex neural circuits (Malgaroli et al. 2021; Park et al. 2020), where synaptic connections between neurons may alter, and dendrites and their connections with other neurons may play a key role in the brain network dynamics of depression. The primary efficacy of TMS in antidepressant therapy is attributed to its regulatory effects on network functions (Adke et al. 2021; Kaboodvand et al. 2023). Consequently, focusing solely on individual neuron may not fully reflect the complexity of interactions within neural networks. The subsequent work of our study will develop a microcircuits or neural network model with neuronal morphological features to precisely simulate the pathological states of depression. And integrating macroscopic brain tissue model to investigate the impact of TMS on neural networks, which is crucial for delineating the potential mechanism of TMS as a therapeutic tool for treating depression.

Conclusion

This investigation has revealed the nuanced responses of neurons, exhibiting varying levels of depressive symptomatology, to TMS by utilizing a multi-scale computational model. The research conclusively demonstrates that the structure of neurons critically influences the effectiveness of TMS. Our findings robustly support the hypothesis that structural differences in neurons, especially those associated with depressive states, significantly impact their activation thresholds. By integrating morphologically accurate neuron models and finite FEM simulations, this study has provided new insights into the potential therapeutic mechanisms of TMS for treating depression. Together, these results in our study enhance the understanding of TMS in individuals with depression and provide concrete empirical support for the strategic regulation of neuronal activity.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the doctors of the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University and the Sixth Clinical Medical College of Hebei University for their assistance. We also sincerely thank Sina Shirinpour et al. for their original multi-scale model and guidance.

Author contributions

Licong Li designed the study and revised manuscript. Shuaiyang Zhang developed the computational model and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Hongbo Wang and Fukuan Zhang performed the analyses of numerical simulation results. Bin Dong, Jianli Yang and Xiuling Liu reviewed the results and provided funding support. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the major research instrument development project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82327810), Foundation of President of Hebei University (Grant No. XZJJ202202) and Hebei Province “333 talent project” (Grant No. A202101058).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jianli Yang, Email: yangjianli_1987@126.com.

Xiuling Liu, Email: liuxiuling121@hotmail.com.

References

- Aberra AS, Wang R, Grill WM, Peterchev AVJ (2023) Multi-scale model of axonal and dendritic polarization by transcranial direct current stimulation in realistic head geometry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Adke AP, Khan A, Ahn H-S, Becker JJ (2021) Cell-type specificity of neuronal excitability and morphology in the central amygdala. Eneuro. 10.1523/ENEURO.0402-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Valles A, De Gregorio D, Matta-Camacho E, Eslamizade MJ (2021) Antidepressant actions of ketamine engage cell-specific translation via eIF4E. Nature 590(7845):315–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S, Fröhlich FJB (2021) Pinging the brain with transcranial magnetic stimulation reveals cortical reactivity in time and space. Brain Stimul 14(2):304–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulakshmi M, Priya GLJI (2019) Walsh Hadamard transform for simple linear iterative clustering (SLIC) superpixel based spectral clustering of multimodal MRI brain tumor segmentation. IRBM 40(5):253–262 [Google Scholar]

- Balwant MJI (2022) A review on convolutional neural networks for brain tumor segmentation: methods, datasets, libraries, and future directions. IRBM 43(6):521–537 [Google Scholar]

- Banasr M, Duman RSJC, Targets ND-D (2007) Regulation of neurogenesis and gliogenesis by stress and antidepressant treatment. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 6(5):311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banasr M, Sanacora G, Esterlis IJ (2021) Macro-and microscale stress–associated alterations in brain structure: translational link with depression. Biol Psychiatry 90(2):118–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee J, Sorrell ME, Celnik PA, Pelled G (2017) Immediate effects of repetitive magnetic stimulation on single cortical pyramidal neurons. PLoS ONE 12(1):e0170528. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boayue NM, Csifcsak G, Puonti O, Thielscher A (2018) Head models of healthy and depressed adults for simulating the electric fields of non-invasive electric brain stimulation. F1000Res 7:704. 10.12688/f1000research.15125.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breit M, Kessler M, Stepniewski M, Vlachos A (2018) Spine-to-dendrite calcium modeling discloses relevance for precise positioning of ryanodine receptor-containing spine endoplasmic reticulum. Sci Rep 8(1):15624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caredda C, Mahieu-Williame L, Sablong R, Sdika M (2021) Real time intraoperative functional brain mapping based on RGB imaging. IRBM 42(3):189–197 [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale TJS (2007) Neuron simulation environment. Scholarpedia 2(6):1378 [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Im C, Seo H, Jun SC (2022) Key factors in the cortical response to transcranial electrical Stimulations-A multi-scale modeling study. Comput Biol Med 144:105328. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng ZD, Robins PL, Dannhauer M, Haugen LM (2023) Comparison of coil placement approaches targeting dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in depressed adolescents receiving repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: an electric field modeling study [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dequidt P, Bourdon P, Tremblais B, Guillevin C (2021) Exploring radiologic criteria for glioma grade classification on the BraTS dataset. IRBM 42(6):407–414 [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Wu Z, Zhao LJC, Practice C (2020) Whale optimization algorithm based on nonlinear convergence factor and chaotic inertial weight. Concurr Comput Pract Exp 32(24):e5949 [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Wu Y, Li T, Yu D (2023) Metabolic energy consumption and information transmission of a two-compartment neuron model and its cortical network. Chaos Solitons Fractals 171:113464 [Google Scholar]

- Dolz J, Massoptier L, Vermandel MJI (2015) Segmentation algorithms of subcortical brain structures on MRI for radiotherapy and radiosurgery: a survey. IRBM 36(4):200–212 [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Jiang S, Wang J, Bai Y (2021) Chronic unpredictable stress induces depression-related behaviors by suppressing AgRP neuron activity. Mol Psychiatry 26(6):2299–2315. 10.1038/s41380-020-01004-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar R, Soares-Cunha C, Domingues AV, Coimbra B (2022) The duration of stress determines sex specificities in the vulnerability to depression and in the morphologic remodeling of neurons and microglia. Front Behav Neurosci 16:834821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogulski J, Ross JM, Talbot A, Cline CC (2022) Personalized rTMS for depression: a review

- Gomez LJ, Dannhauer M, Peterchev AVJN (2021) Fast computational optimization of TMS coil placement for individualized electric field targeting. Neuroimage 228:117696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grehl S, Viola HM, Fuller-Carter PI, Carter KW (2015) Cellular and molecular changes to cortical neurons following low intensity repetitive magnetic stimulation at different frequencies. Brain Stimul 8(1):114–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju C, Ding H, Hu BJTCJ (2023) A hybrid strategy improved whale optimization algorithm for web service composition. Comput J 66(3):662–677 [Google Scholar]

- Kaboodvand N, Iravani B, van den Heuvel MP, Persson J (2023) Macroscopic resting state model predicts theta burst stimulation response: a randomized trial. PLoS Comput Biol 19(3):e1010958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairandish MO, Sharma M, Jain V, Chatterjee JM (2022) A hybrid CNN-SVM threshold segmentation approach for tumor detection and classification of MRI brain images. IRBM 43(4):290–299 [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lei Y, Lu X-Y, Kim CS (2022) Glucocorticoid-glucocorticoid receptor-HCN1 channels reduce neuronal excitability in dorsal hippocampal CA1 neurons. Mol Psychiatry 27(10):4035–4049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler O, Khrapunsky Y, Shvartsman A, Dai H (2023) SUMOylation of NaV1. 2 channels regulates the velocity of backpropagating action potentials in cortical pyramidal neurons. Elife 12:e81463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AL, Ogle WO, Sapolsky RM (2002) Stress and depression: possible links to neuron death in the hippocampus. Bipolar Disord 4(2):117–128. 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01144.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y, Wang J, Wang D, Li C (2020) SIRT1 in forebrain excitatory neurons produces sexually dimorphic effects on depression-related behaviors and modulates neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the medial prefrontal cortex. Mol Psychiatry 25(5):1094–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Huang W, Chen Y, Aslam MS (2023) Acupuncture alleviates CUMS-induced depression-like behaviors by restoring prefrontal cortex neuroplasticity. Neural Plast 20231:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioumis P, Zomorrodi R, Hadas I, Daskalakis ZJ (2018) Combined transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroencephalography of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. J vis Exp. 10.3791/57983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Li C, Wang J, Zhang X (2021) Amygdala-hippocampal innervation modulates stress-induced depressive-like behaviors through AMPA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(6):e2019409118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Rothwell J, Goetz SJ (2022) A revised calcium-dependent model of theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation [DOI] [PubMed]

- Malgaroli M, Calderon A, Bonanno GA (2021) Networks of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 85:102000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SC, Palmer LM, Nyffeler T, Müri RM (2016) Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) inhibits cortical dendrites. Elife 5:e13598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson SE, Singh H, Kerr MS, Podlesh Z (2023) The role of transcranial magnetic stimulation in treating depression after traumatic brain injury. Brain Stimul 16(2):456–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagkalos M, Chavlis S, Poirazi PJNC (2023) Introducing the dendrify framework for incorporating dendrites to spiking neural networks. Nat Commun 14(1):131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S-C, Kim DJJ (2020) The centrality of depression and anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder determined using a network analysis. J Affect Disord 271:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashut T, Wolfus S, Friedman A, Lavidor M (2011) Mechanisms of magnetic stimulation of central nervous system neurons. PLoS Comput Biol 7(3):e1002022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashut T, Magidov D, Ben-Porat H, Wolfus S (2014) Patch-clamp recordings of rat neurons from acute brain slices of the somatosensory cortex during magnetic stimulation. Front Cell Neurosci 8:145. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rădulescu I, Drăgoi AM, Trifu SC, Cristea MBJE (2021) Neuroplasticity and depression: rewiring the brain’s networks through pharmacological therapy. Exp Ther Med 22(4):1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado JM (2022) Ultrastructural neuronal modeling of calcium dynamics under transcranial magnetic stimulation. Temple University, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- Sancho-Balsells A, Borràs-Pernas S, Brito V, Alberch J (2023) Cognitive and emotional symptoms induced by chronic stress are regulated by EGR1 in a subpopulation of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Int J Mol Sci 24(4):3833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirinpour S, Hananeia N, Rosado J, Tran H (2021a) Multi-scale modeling toolbox for single neuron and subcellular activity under transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Stimul 14(6):1470–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirinpour S, Mantell K, Li X, Puonti O (2021b) New tools for computational modeling of non-invasive brain stimulation in SimNIBS. Brain Stimul 14(6):1644 [Google Scholar]

- Slomski AJJ (2018) Repetitive TMS for treating depression in veterans. JAMA 320(16):1631–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati M, Mikkonen M, Laakso I, Murakami T (2018) A multi-scale computational approach based on TMS experiments for the assessment of electro-stimulation thresholds of the brain at intermediate frequencies. Phys Med Biol 63(22):225006. 10.1088/1361-6560/aae932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian W, Peng L, Zhao M, Tao L (2022) Dendritic morphology affects the velocity and amplitude of back-propagating action potentials. Neurosci Bull 38(11):1330–1346. 10.1007/s12264-022-00931-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Van-Minh A, Caze RD, Abrahamsson T, Cathala L (2015) Contribution of sublinear and supralinear dendritic integration to neuronal computations. Front Cell Neurosci 9:67. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turi Z, Hananeia N, Shirinpour S, Opitz A (2022) Dosing transcranial magnetic stimulation of the primary motor and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices with multi-scale modeling. Front Neurosci 16:929814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoornweder S, Meesen RL, Caulfield KA (2022) Accurate tissue segmentation from including both T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI scans significantly affect electric field simulations of prefrontal but not motor TMS. Brain Stimul 15(4):942–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Liu B, Liu L, Zhu Y (2021) A review of deep learning used in the hyperspectral image analysis for agriculture. Artif Intell Rev 54(7):5205–5253 [Google Scholar]

- Weise K, Numssen O, Kalloch B, Zier AL (2023a) Precise motor mapping with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Nat Protocol 18(2):293–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise K, Worbs T, Kalloch B, Souza VH (2023b) Directional sensitivity of cortical neurons towards TMS-induced electric fields. Imaging Neurosci 1:1–22. 10.1162/imag_a_00036 [Google Scholar]

- Windhoff M, Opitz A, Thielscher A (2013) Electric field calculations in brain stimulation based on finite elements: an optimized processing pipeline for the generation and usage of accurate individual head models (Report No. 1065-9471) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wischhusen J, Padilla FJI (2019) Ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction (UTMD) for localized drug delivery into tumor tissue. IRBM 40(1):10–15 [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Ding H, Gong M, Qin A (2022) Evolutionary multiform optimization with two-stage bidirectional knowledge transfer strategy for point cloud registration. IEEE Trans Evol Comput 200:300. 10.1109/TEVC.2022.3215743 [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Gong P, Gong M, Ding H (2023) Evolutionary multitasking with solution space cutting for point cloud registration. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput Intell 8:110–125 [Google Scholar]

- Ye H, Steiger A (2015) Neuron matters: electric activation of neuronal tissue is dependent on the interaction between the neuron and the electric field. J Neuroeng Rehabil 12:65. 10.1186/s12984-015-0061-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi GS, Wang J, Deng B, Wei XL (2017) Morphology controls how hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neuron responds to uniform electric fields: a biophysical modeling study. Sci Rep 7(1):3210. 10.1038/s41598-017-03547-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G, Ranieri F, di Lazzaro V, Sommer M (2023) The origin of I-waves: computational neuronal network model of the cortical column response to TMS. Brain Stimul 16(1):149 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Duan J, Sa Y, Guo YJI (2022) Multi-atlas based adaptive active contour model with application to organs at risk segmentation in brain MR images. IRBM 43(3):161–168 [Google Scholar]