Abstract

Most synthetic self-assemblies grow indefinitely into size-unlimited structures, whereas some biological self-assemblies autonomously regulate their size and shape. One mechanism of such self-regulation arises from the chirality of building blocks, inducing their mutual twisting that is incompatible with their long-range ordered packing and thus halts the assembly’s growth at a certain stage. This self-regulation occurs robustly in thermodynamic equilibrium rather than kinetic trapping, and therefore is attractive yet elusive. Until now, studies of self-regulating assemblies have focused on non-responsive systems, whose equilibrium point and corresponding size and shape are hardly changeable. Here, we demonstrate a stimuli-responsive, self-regulating assembly. This assembly consists of chiral and magnetically orientable nanorods, where the effective chirality can be changed by balancing chirality-induced twisting and magnet-induced flattening between nanorods. Consequently, the strength of self-regulation in the assembly is modulable by magnetic field intensity, allowing robust, tunable, and reversible control of its size and shape. Our strategy would provide more biomimetic materials with precision and responsiveness.

Subject terms: Supramolecular polymers, Colloids, Nanoparticles

The self-regulation of self-assembled systems is well understood for non-responsive systems, but responsive systems are less studied. Here, the authors report the development of a stimuli-responsive, self-regulating assembly of chiral and magnetically responsive nanorods, with control over the chirality of the system.

Introduction

From biological tissues to synthetic materials, self-assembly is critical for creating functional superstructures from microscopic building blocks1,2. In most self-assemblies, building blocks repeat the same association indefinitely to form structures with unlimited size (Fig. 1a, right)3–8. In nature, however, some assemblies autonomously result in certain sizes and shapes through the self-regulation mechanism9–12, where their well-regulated size and shape lead to various excellent functions. A well-known, intuitive example is the assembly regulated by self-closing, represented by a viral outer shell with a defined diameter9, which grows along a curvature and eventually closes into a sphere or tube. Another intriguing example is the assembly regulated by chirality-induced frustration, as exemplified by a cytoskeletal bundle of defined thickness10, which exposes its open boundary that apparently continues to grow but cannot go any further. This is because the chirality of the filamentous building blocks induces their mutual twisting that is incompatible with their long-range ordered packing and suppresses the assembled bundle to grow beyond a critical diameter (Fig. 1a, left). These examples involve complex feedback mechanisms wherein the building blocks sense the whole assembly’s size, which is much larger than the individual blocks, and reflect it on the assembly pathways.

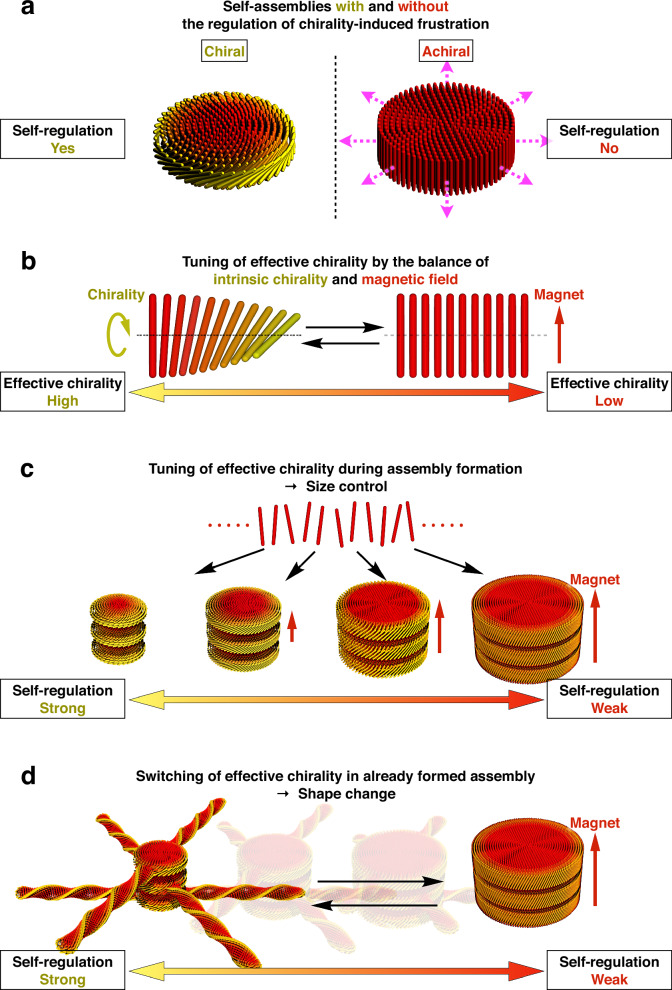

Fig. 1. Design of self-assembly mechanism with self-regulation and stimuli-responsiveness for rational control of size and shape.

a Left: self-assembly with the regulation of chirality-induced frustration, where the chirality of the building blocks induces their mutual twisting, which is incompatible with their ordered packing and stops the assembly’s growth over a certain size. Right: self-assembly without the regulation of chirality-induced frustration, where the building blocks devoid of chirality tend to repeat the same association infinitely to form an unlimited bulk. b Strategy for tuning the degree of chirality effectively expressed in the system by the balance between chirality-induced twisting and magnet-induced flattening. c Size control of the present self-regulating assembly by tuning effective chirality during the assembly is forming. d Shape change of the present self-regulating assembly by switching effective chirality after the assembly is formed.

Self-regulating assemblies in nature yield size/shape-regulated structures not as kinetically trapped intermediates but as thermodynamically equilibrated products. Therefore, this regulation is robust even in complicated and uncontrollable environments such as in vivo. This is in sharp contrast to the size/shape regulation in synthetic self-assembly, which relies exclusively on the kinetic trapping of growing intermediates13–18, and is therefore feasible only when conditions such as temperature, solvent, and component concentration are precisely controllable. Inspired by such natural systems with robust mechanisms, there have been increasing efforts to develop self-regulating assemblies9–12,19,20. However, previous studies have dealt only with constant systems whose thermodynamic equilibrium point is predetermined, so that their size and shape cannot be easily changed9–12,19,20. Among such self-regulating assemblies, here we demonstrate the first example of the stimuli-responsive system, whose thermodynamic equilibrium point can be modulated by external stimuli, allowing for rational control of its size and shape in situ.

To design an assembly with both self-regulation and stimuli-responsiveness, we focused on the above-mentioned feedback mechanism of chirality-induced frustration (Fig. 1a, left)19,20. This regulation is expected to operate more intensely at a higher degree of chirality expressed in the assembly. On the other hand, in some self-assemblies with chirality, such as cholesteric liquid crystals, the effective chirality expressed in the system can be tuned by an external field, such as an electric or magnetic field, which forces the building blocks to orient unidirectionally against their twisting tendency (Fig. 1b)21–26. We envisioned that, by introducing this chirality tuning mechanism, a self-regulating assembly would acquire stimuli-responsiveness.

The above design requires chiral and field-orientable building blocks that pack into ordered structures. Among several candidates that satisfy these requirements27–30, we chose a typical rod-shaped virus30, M13 bacteriophage31–34, because of its easy availability and highly monodisperse shape (contour length of 880 nm / diameter of 6.6 nm). When mixed with a non-adsorptive polymer with appropriate chain length, such as dextran, the rods of the virus are known to pack side-by-side due to the polymer’s entropic demand to force the rods to minimize their exposed surface area, a phenomenon known as the depletion effect35–41. In addition, the virus’s outer shell is composed of amino acids, whose chirality causes a twisted geometry between the virus rods (Fig. 1b, left)30,37,39. Furthermore, despite their diamagnetic nature, the virus rods are unidirectionally orientable under a sufficiently strong magnetic field, owing to their anisotropic diamagnetic susceptibility (Fig. 1b, right)42–44. Due to these characteristics, the virus rods actually afford the stimuli-responsive, self-regulating assembly. When the depletion-induced assembly is performed without a magnetic field, the virus’s chirality is fully expressed to maximize self-regulation, affording assemblies with a uniformly small diameter. In contrast, under a strong magnetic field, the effective chirality and concomitant self-regulation are minimized, resulting in assemblies with larger diameters (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Movie 1). By adjusting the magnetic field intensity, the thermodynamic equilibrium point of the system shifts accordingly, allowing for rational control of the assembly’s diameter. Furthermore, when the magnetic field is switched on/off for an already formed assembly, the thermodynamic equilibrium point shifts largely, so that the assemblies undergo a drastic shape change (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Movie 2). A theoretical model can thoroughly explain these phenomena (Supplementary Method).

The present self-assembly reproduces a feature of biological systems that respond to their environment while regulating their size and shape. In addition, such precise and yet modulable size/shape control is based on thermodynamic equilibration, which does not require extremely accurate control of conditions, unlike the conventional size control based on kinetic trapping13–18. Furthermore, this size/shape control can be done in a clean, remote, and reversible manner, by simply changing the magnetic field intensity42–44. Considering the mechanism, the strategy would be applicable to various non-spherical colloids with chirality and orientability27–30.

Results

Effects of a magnetic field on the self-regulation during the assembly formation

We started by investigating the depletion-induced assembly of the above-mentioned virus without a magnetic field. When colloidally dispersed virus rods (6.5 mg/mL) were mixed with dextran (20 mg/mL) in tris-buffered saline, we observed the formation of micrometer-sized cylindrical objects (Fig. 2a, i and Supplementary Fig. 1a). In optical microscopy, cylinders exposing their side exhibited a stripe pattern with a periodicity of 1.2 µm (Fig. 2a, ii, upper), while cylinders showing their top appeared monotonically (Fig. 2a, ii, lower). Polarized optical microscopy (POM) observation indicates that the virus rods aligned parallel to the cylinder axis (Supplementary Fig. 2a). The 3D confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) reconstruction revealed that the stripe pattern persisted throughout the cylinder (Fig. 2a, iii and Supplementary Movie 1), indicating that this assembly was a lamellar stack of disks with a uniform thickness of ~ 1 µm. The formation of individual disks is attributed to the side-by-side packing of the virus rods to form a one-rod-length thick monolayer assembly caused by the depletion effect of dextran, as reported35–41. Meanwhile, the stacking of thus formed disks is driven by the inter-disk bridging with the dimer virus, which has twice the contour length of the native monomer virus (Supplementary Fig. 3a) and is known to mix in the monomer in a tiny amount during the biological amplification process36. Since the monomer and dimer are separable through the phase separation of their mixture dispersion36, the number of stacked disks in a lamellar cylinder can be controlled by changing the ratio of the dimer to the monomer (Supplementary Figs. 4,5). The lamellar cylinder was assembled over wide ranges of the virus (4.0–6.5 mg/mL) and dextran (18–22 mg/mL) concentrations (Fig. 2b). Notably, the lamellar cylinders had a narrow diameter dispersity at around ~ 4 µm (Fig. 2c), indicating that the presence of self-regulation mechanism due to the virus’s chirality.

Fig. 2. Effects of a magnetic field on self-regulation during the assembly formation.

a, d Lamellar cylinders composed of M13 bacteriophage (6.5 mg/mL) in the presence of dextran (20 mg/mL) without (a) and with (d) a 10-T magnetic field; (i) wide-view optical microscopy image, (ii) magnified optical microscopy image, and (iii) 3D reconstruction of confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images with negative fluorescent contrast. b, e Phase behavior of the virus assembly upon changing the concentrations of the virus and dextran without (b) and with (e) a 10-T magnetic field. c, f Diameter distributions of the lamellar cylinders at the equilibrated state, formed from [virus] = 6.5 mg/mL and [dextran] = 18 ~ 22 mg/mL, without (c) and with (f) a 10-T magnetic field. All assembly experiments were conducted in tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5, 50 mM of tris, 150 mM of NaCl) within a glass sandwich cell at 20 °C. The box-whisker plot of diameter is based on > 100 different lamellar cylinders under the same conditions, using the whisker method with min and max data and the Tukey quartile method.

Motivated by this confirmed self-regulation mechanism, we performed the assembly formation in a strong magnetic field minimizing the effective chirality in the system. Note that the intensity of the magnetic field used (10 T) was sufficient to orient the virus rods almost perfectly42–44. Under a 10-T magnetic field applied in the in-plane direction of the sample container, the virus rods were again assembled into the lamellar cylinder (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The long axes of the cylinders thus assembled were oriented parallel to the magnetic field (Fig. 2d, i), and could be re-oriented by changing the magnetic field direction (Supplementary Fig. 6). Optical microscopy (Fig. 2d, ii), 3D CLSM (Fig. 2d, iii and Supplementary Movie 1), and POM (Supplementary Fig. 2b) revealed that the assembled structure was essentially similar to that without a magnetic field. The ranges of the virus and dextran concentrations that yielded the lamellar cylinder (Fig. 2e) were also identical to those without a magnetic field. Interestingly, however, the magnetic field significantly affected the diameters of the lamellar cylinders, which were widely distributed and on average ~ 2 times larger (Fig. 2f) than those assembled without a magnetic field (Fig. 2c). Such comparison suggests that the self-regulation was attenuated by the magnetic field that minimized the effective chirality in the system.

A closer analysis of the result revealed that, through the self-assembly with a magnetic field, the lamellar cylinder enlarges not only the diameter but also the length, although the increase in the length is not as obvious as the diameter (Supplementary Fig. 7). As mentioned above, the length of the lamellar cylinder is elongated by the bridging of the monolayer disks with the dimer virus that mixes with the monomer in a tiny amount36 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Given this mechanism, the diameter enlargement of the monolayer disk by the magnetic field should enhance the probability of the bridging, thereby elongating of the lamellar cylinder.

Mechanism for the control of assembly size by magnetically modulable self-regulation

To identify the mechanism of how chirality regulates the assembly’s size and how the magnetic field modulates this regulation, we developed a theoretical model to calculate the free energy of the lamellar cylinder. The model considers depletion energy, Frank free energy (equivalent here to twist energy), and magnetic free energy (Supplementary Method)45,46. Given the cylindrical symmetry, the structure of the lamellar cylinder can be described by the tilt angle of virus rod from the normal of the disks stacked in the cylinder, denoted as θ, as a function of the distance from the disk center, denoted as r (Supplementary Fig. 8a). The cylinder’s radius, corresponding to the maximum of r, is denoted as R. This model affords the energy-optimized structures of the lamellar cylinder at various radii R from 1 to 10 µm, as well as the dependency of the free energy on the radius R, under without and with a magnetic field (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3. Mechanism for the control of assembly size by the magnetic modulation of self-regulation.

a, b Theoretically predicted structure and free energy of the lamellar cylinder without (a) and with (b) a 10-T magnetic field: (i) energy-optimized structures with various cylinder radii R and (ii) free energy as a function of cylinder radius R. c Theoretically predicted structure of the lamellar cylinder at various magnetic-field intensities. Main: free energy as a function of cylinder diameter 2 R, where the plots are offset for easy comparison of their shapes (for plots without offsetting, see Supplementary Fig. 9). Inset: cylinder diameter 2 R at the energy-minimal as a function of magnetic-field intensity. d Experimental control of the size of the lamellar cylinder by changing the intensity of the magnetic field applied during the assembly formation: (i) optical microscopy images and (ii) diameter distributions. The box-whisker plot of diameter is based on > 100 different lamellar cylinders under the same conditions, using the whisker method with min and max data and the Tukey quartile method.

The structure of the assembly is dictated by the balance between the depletion, chirality, and magnetic effects. Under a 10-T magnetic field, the chirality effect is canceled out by the magnetic effect, while the depletion effect demands the virus rods to minimize their total exposed surface area. Therefore, at the inner region of the disk, the virus rods are forced to pack side-by-side and orient perpendicular to the monolayer disk, whereas, at the disk edge, the virus rods tilt away from the disk normal to form a semicircular cross-section shape due to the surface tension force37. Consequently, the tilt angle θ remains close to 0° over a wide range of r and abruptly increases only at the edge (r = R), which is common regardless of the cylinder’s radius R (Fig. 3b, i). In contrast, without a magnetic field, the chirality effect, which demands the array of virus rods to twist continuously with a pitch determined by their intrinsic chiral structure30, competes with the depletion effect. As a result, the tilt angle θ increases continuously from the center (r = 0) and eventually becomes close to 90° at the edge (r = R), as a common feature regardless of the cylinder’s radius R (Fig. 3a, i). Thus, predicted structures without and with a magnetic field consist of their POM observation viewed from the top that selectively visualizes the domains with tilt virus rods as bright (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b, ii). For both without and with a magnetic field, most parts of the cylinder appeared as dark, while only the cylinder’s edge appeared as bright. In addition, at the edge region, the cylinder with a magnetic field showed a sharper brightness increase than without a magnetic field.

As clarified above, the presence or absence of a magnetic field brings critical effects on the twisting pitch of the array of virus rods, which is represented by the slope of the θ–r curve, i.e., how quickly θ increases upon increasing r. Without a magnetic field, the θ–r curves for various R values show different slopes (Fig. 3a, i) so that the free energy is dependent on R and has a sharp minimum at R = 2 µm (Fig. 3a, ii). Meanwhile, with a magnetic field, the θ–r curve can be divided into a flat region at smaller r and a steep region at larger r. At both the flat and steep regions, the θ–r curves for various R values show similar slopes to each other (Fig. 3b, i). The free energy curve becomes shallow, and the minimum positions shift to larger r (Fig. 3b, ii). This result agrees with our observation that the lamellar cylinders prepared without a magnetic field have diameters of ~ 4 µm with a narrow dispersity (Fig. 2c), while those prepared under a magnetic field grow beyond the diameter of ~ 4 µm with a wide distribution (Fig. 2f).

The present model also predicts how the cylinder’s diameter changes when the effective chirality in the system is gradually tuned. Thus, we calculated the free energy–R curves of the lamellar cylinder under various magnetic-field intensities (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 9). Upon increasing the magnetic-field intensity from 0 to 10 T, the energy minimum point shifts to the larger R region and becomes shallower in depth (Fig. 3c). In good accordance with this theoretical prediction, when the assembly formation experiment was performed under various magnetic-field intensities, the diameters of the resultant lamellar cylinders became larger with wider distribution as the magnetic field became stronger (Fig. 3d).

Effects of a magnetic field on the self-regulation of already formed assembly

Considering that the virus rods in the assembly were packed by the depletion-driven reversible interaction, the degree of twisting might be modulable even after the assembly formation is complete. Therefore, we switched a magnetic field for already formed lamellar cylinders, so that the strength of effective chirality and concomitant self-regulation were abruptly changed. We first assembled the virus rods under a 10-T magnetic field to obtain the larger-diameter lamellar cylinders, as described above (Fig. 2d) and then removed the magnetic field. Surprisingly, we observed the emergence and continuous elongation of many fibers with a uniform thickness of ~ 1.2 µm from the cylinder’s periphery (Fig. 4a, i and Supplementary Movie 3, former half). Accompanying this, the lamellar cylinder at the center decreased in diameter (Fig. 4b, i). This branching transformation took place regardless of the orientation of the lamellar cylinders (Supplementary Fig. 10, i–iii and Supplementary Movie 2). According to 3D CLSM (Fig. 4c, i), the emerging filaments were twisted ribbons with the thickness of the virus rod monolayer, similar to those reported previously37,47. In the reflection-mode CLSM image without a fluorescent dye, bright regions appeared periodically in synchronous with the twisted shape in the bright field image (Fig. 4c, ii), which further verified that the emerging filaments were the twisted ribbons of the virus rod monolayer.

Fig. 4. Effects of a magnetic field on the self-regulation of already formed assembly.

a Shape change of the virus-rod assembly monitored by top-view optical microscopy (upper) and 3D CLSM (lower): (i) branching from the lamellar cylinder to the twisted ribbons upon removal of the magnetic field and (ii) converging from the twisted ribbons back to the lamellar cylinder upon reapplication of the magnetic field. b Time-course changes in the diameters of the lamellar cylinders during (i) branching upon removal of the magnetic field and (ii) converging upon reapplication of the magnetic field. c Characterization of the twisted ribbon branched from the lamellar cylinder: (i) 3D CLSM image and (ii) reflection-mode CLSM (mid), bright-field (upper), and overlapping (lower) images. The original lamellar cylinders were prepared under similar conditions to those in Fig. 2b and then reoriented by a 10-T magnetic field in the out-of-plane direction for their top-view observation. To induce the branching, the magnetic field was removed. To promote converging, a 10-T magnetic field was reapplied in the out-of-plane direction. The box-whisker plot of diameter is based on > 100 different lamellar cylinders under the same conditions, using the whisker method with min and max data and the Tukey quartile method.

Of further interest, when a 10-T magnetic field was applied to this branched assembly so that the effective chirality was minimized again, a reverse phenomenon occurred. The twisted ribbons gradually converged towards the central lamellar cylinder (Fig. 4a, ii and Supplementary Movie 3, latter half), so that the cylinder continued to thicken and eventually reached close to its original size (Fig. 4b, ii). The converging transformation also did not depend on the orientation of the cylinders (Supplementary Fig. 10, iii–v). Overall, it was found that the on/off switching of the magnetic field controls the reversible polymorphic shape change of the virus rod assembly between the lamellar cylinder and the twisted ribbon. It was also found that the repeatable cycle number of the transformation depends on the distance between the assembled cylinders. When a cylinder is far enough away from the other cylinders, it can repeat the transformation many times, but when several cylinders are located close to each other, the twisted ribbons grown from different cylinders tend to become entangled (Supplementary Fig. 11), preventing the perfect recovery of the twisted ribbons into the lamellar cylinder.

Mechanism for the control of assembly shape by magnetically modulable self-regulation

We hypothesized that the drastic shape changes of the virus rod assemblies are controlled by the switching of effective chirality, i.e., abrupt change of the degree of twist between the virus rods. To confirm this, the larger-diameter lamellar cylinder, just after being prepared in a 10-T magnetic field, was monitored under a magnet-free condition from the cylinder’s top, using retardation imaging (Fig. 5a, i and Supplementary Fig. 12) and director field mapping (Fig. 5a, ii)48. Initially, only the edge of the cylinder showed weak retardation (Fig. 5a, i/ii, 0 min). As time passed, the retardation increased at the edge and expanded towards the cylinder interior (Fig. 5a, i/ii, 10–30 min), indicating that the tilting of the virus rods progressed from the edge to the center. The time-course plot of the retardation against the distance from the cylinder’s center revealed a quantitative change in the local tilt of virus rods (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Fig. 5. Mechanism of the control of assembly shape by the magnetic modulation of self-regulating.

a Structural and dynamics changes of the larger-diameter lamellar cylinder just after removal of the magnetic field: (i) time-course changes of the retardation image viewed from the top, (ii) time-course changes of director field of the area highlighted by dotted square in (i), and (iii) trajectories of fluorescently labeled virus rods monitored by top-view fluorescence optical microscopy in which 0.02% of the virus rods are fluorescently labeled. b Theoretically predicted energy diagram of the virus rod assembly: (i) the larger-diameter lamellar cylinder prepared with a magnetic field, (ii) the lamellar cylinder just after the removal of the magnetic field, (iii) the lamellar cylinder after reducing its radius through branching of the twisted ribbon, and (iv) the twisted ribbon branched from the lamellar cylinder.

The tilting of the edge-region virus rods impacts the microscopic dynamics of virus rods in assembly, as revealed by fluorescence optical microscopy of the lamellar cylinder containing 0.02% fluorescent-labeled virus rods36. When viewed from the cylinder’s top, the individuals of the labeled virus rods were observed as spots migrating within a disk in the cylinder. We classified these spots into two groups based on their diffusion being higher and lower than a threshold of 0.09 µm s–1. We found that the spots with higher mobility were predominantly located at the cylinder’s edge (Fig. 5a, iii, yellow), while those with lower mobility were at the cylinder’s center (Fig. 5a, iii, red). The diffusion coefficient of the former group was more than an order of magnitude higher than that of the latter group (Supplementary Fig. 14)49,50.

For further rationalization of this shape-change mechanism driven by tuning the effective chirality in the already formed assembly, we employed the theoretical model constructed in the previous section, where the free energy diagram of the lamellar cylinder without (Fig. 5b, yellow) and with a magnetic field (Fig. 5b, red) has already been obtained. We also calculated the optimized structure of the twisted ribbon and its free energy (Supplementary Method and Supplementary Fig. 15)47, where its radius R should be constant at 0.6 µm as experimentally observed (Fig. 4c) so that the free energy is depicted as a horizontal line in the diagram (Fig. 5b, green). Under the minimized effective chirality by applying a magnetic field, the depletion effect urges the virus rods to assemble according to the corresponding free energy curve (Fig. 5b, red) to form the larger-diameter lamellar cylinder with little tilt of the virus rods (Fig. 5b, i). When the effective chirality is maximized by removing the magnetic field, the assembly transitions to a new free energy curve (Fig. 5b, yellow), rendering the large cylinder diameter energetically unstable (Fig. 5b, ii). To release this instability, the lamellar cylinder begins to reduce its diameter by sprouting twisted ribbons (Fig. 5b, iv). This transition continues until the assembly reaches the free energy minimum (Fig. 5b, iii). When the effective chirality is again minimized by applying a magnetic field, the assembly returns to the original free energy curve (Fig. 5b, red), and the cylinder’s edge converges with the twisted ribbons to re-form the larger-diameter lamellar cylinder, as demanded by the depletion effect (Fig. 5b, i).

A remaining question is why the larger-diameter lamellar cylinder, after removing the magnetic field (Fig. 5b, ii), does not simply split into multiple small-diameter cylinders (Fig. 5b, iii), but sprouts twisted ribbons (Fig. 5b, iv) to reduce its diameter (Fig. 5b, iii), although the theoretical study reveals that the smaller-diameter cylinder (Fig. 5b, iii) is more stable than the twisted ribbon (Fig. 5b, iv). As observed in Fig. 5a, the virus rods in the assembly can dynamically migrate at the region near the edge, while the splitting of an assembly into multiple pieces never occurs. This is because the assembly tends to avoid a transformation that drastically increases the exposed surface area, which results in a severe energetic cost due to the depletion effect. Under such restriction, the larger-diameter cylinder or the twisted ribbons sprouting from the cylinder core cannot split to form multiple smaller-diameter cylinders. In other words, the small cylinder without twisted ribbons can be obtained only from the unassembled dispersion of the virus rods, which have abundantly exposed surfaces (Fig. 2a–c).

Discussion

Using a rod-shaped virus as a simple model31–34, we demonstrated a self-regulating assembly whose size and shape can be modulated by external stimuli. The key to this achievement is the introduction of the chirality-modulation mechanism21–26 into a self-assembly regulated by chirality-induced frustration19,20. In conventional assemblies regulated by this mechanism, the degree of chirality expressed in them is predetermined, so that their size and shape are not modulable19,20. In contrast, our assembly composed of the virus rods with chirality30 and magnetic orientability42–44 can modulate its effective chirality by the magnetic-field intensity21–26 (Fig. 1b), so that the strength of self-regulation is modulated accordingly. When the self-regulation strength is adjusted during the assembly formation, the assembly’s final size is controlled on demand (Fig. 1c). Meanwhile, when the self-regulation strength is switched on/off in the already formed assembly, a drastic shape change is caused reversibly (Fig. 1d).

The self-assembly mechanism described here has broad implications. From the viewpoint of biomimetic science, the present self-assembly is an important example of reproducing biological systems that respond to their environment while regulating their size and shape. From a materials science perspective, its regulation mechanism based on thermodynamic equilibration is expected to address the limitation of conventional regulation mechanism based on the kinetic trapping of growing intermediates, which requires strictly tuned conditions and cannot work in less-controllable environment13–18. Our preliminary studies revealed that the present self-assembly is tolerant at physiological temperature and pH (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17b) but not operable in physiological medium (Supplementary Fig. 19) or at non-physiological pH ranges (Supplementary Fig. 17a, c). Such a limitation in environmental tolerance would be able to be solved by tuning the surface potential of the virus rod (Supplementary Fig 18), which remains a challenge to be addressed in the future. From the practical standpoint, the present size/shape control can be induced simply by changing the magnetic field intensity, and is therefore clean, remote, and reversible without changing the properties of building blocks, leading to various future applications. Indeed, taking advantage of the magnetic orientation, a huge lamellar assembly with large-area orientability (several millimeters) and ultralong periodicity (1200 nm) can be constructed, which has potential use as a photonic crystal for manipulating near-infrared lights (Supplementary Fig. 20). Our approach, based on the balance between chirality-induced twisting and field-induced alignment is, in principle, applicable to various non-spherical colloids with chirality and orientability27–30.

Methods

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, reagents were used as received from New England Biolabs [E. coli ER2738 and M13 bacteriophage], Sigma Life Science [dextran from Leuconostoc spp. (450 K–650 K Da)], Nacalai Tesque [polyethylene glycol (PEG; 6000 Da)], STAR Chemical [tris(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane (tris)], Sigma Aldrich [sodium chloride (NaCl), fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran], Bemis [Parafilm M sealing film], Toray [Dow Corning Toray], Muto Pure Chemicals [micro cover glass (18 × 24 mm, 0.12–0.17 mm)], and ThermoFisher Scientific [DyLight 488 NHS Ester]. Deionized water was obtained from a Millipore model Milli-Q integral water purification system. Zeta potentials were measured by using a Malvern model Zetasizer Pro Red zeta potential analyzer.

Preparation of the virus

M13 bacteriophage was amplified by E-coli and purified by repetitive precipitation with PEG/NaCl according to the literature method51. The concentration of the virus was determined by UV/Vis spectroscopy using an Implen model NanoPhotometer or a Thermo Scientific model NanoDropTM One spectrometer48,51. The doping ratio of the virus dimer of each sample was determined by atomic force microscopy (AFM) observation (Supplementary Fig. 4). The fluorescent-labeled virus was prepared from the pristine virus and DyLight 488 NHS Ester, according to the literature49.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

AFM images were collected in tapping mode with an Asylum model Research Cypher AFM system with a sharpened tetrahedral-shaped silicon cantilever (resonant frequency, 70 kHz; spring constant, 2 N m–1; OMCL-AC240TS-R3, Olympus). A solution of the virus (10 µg/mL) was spin-coated for 30 s at 3000 rpm onto a freshly cleaved mica surface and subjected to the AFM measurement.

Assembling of virus rods

Cover glasses were precleaned in soap, deionized water, and ethanol for 30 min under sonication. The cell was made by sandwiching a layer of parafilm (~ 130 µm thickness) with two cover glasses. A mixture of the virus (1.5–6.5 mg/mL) and dextran (15–30 mg/mL) in a tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5, 50 mM of tris, 150 mM of NaCl) was filled in the cell, whose sides were sealed with Dow Corning Toray. The cell was kept at 20 °C for 60 h.

Application of magnetic field

Magnetic fields of 1–10 T were generated by a JASTEC model JMTD-10T100 superconducting magnet with a bore of 100 mm. The glass-sandwiched cell filled with a virus sample was placed in the magnetic field so that the field was directed in the in-plane or the out-of-plane direction.

Optical microscopy

Optical microscopy images under normal light and cross-polarized light were taken on a Nikon model ECLIPSE Pi2-E inverted microscope. The diameters of the lamellar cylindrical assemblies of the virus were evaluated by analyzing optical microscopy images taken after subjecting glass sandwiched cells in a 10-T magnetic field directed in the out-of-plane direction, using the software ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). For fluorescence optical microscopy, the virus assembly was prepared from a pristine virus containing 0.02% of the fluorescent-labeled virus. As a light source, a Nikon model INTENSILIGHT C-HGFIE with a 450–490 nm filter was used. The migration profiles of individual virus rods were analyzed according to the literature36,49,50.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

CLSM images were taken on a Leica model TCS SP8 microscope. In the negative-contrast CLSM, the virus assembly was prepared by treating the pristine virus with the fluorescent-labeled dextran and observed by using a 500 nm laser. In the reflection-mode CLSM, the assembly was prepared by treating the pristine virus with the pristine dextran and observed by using a 476 nm laser.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)

Small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) measurement was performed on a Rigaku model NANOPIX 3.5 m system using a Rigaku model HyPix-6000 detector. The virus sample was filled into a 1.5 mm-φ glass capillary. To obtain the azimuthal angle plots, the 2D SAXS image was integrated along the Debye-Scherrer ring with a q range of 0.1–1.0 nm–1, using the Fit2D software (http://www.esrf.eu/computing/scientific/FIT2D/).

Retardation imaging and director field mapping

Polarimetric microscopic images were taken on an Olympus BX61W1 microscope with an FWHM bandpass filter and then converted into retardation images. Polarizing plates and quarter-wave plates were set as described in Supplementary Fig. 10. Director field mapping was conducted according to the literature48.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JST CREST Grant Numbers JPMJCR17N1 and JPMJCR22B1 Japan (for Y.I.), JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 20H02791 (for Y.I.), JST SICORP Grant Number JPMJSC22C3 (for F.A.), National Research, Development, and Innovation Office FK Grant Number 142643 (for P.S.), National Research, Development, and Innovation Office EIG Concert-Japan Grant Number 2023-1.2.1-ERA_NET-2023-00008 (for P.S.), and Hungarian Academy of Sciences János Bolyai Research Scholarship Grant Number BO/00294/22/11 (for P.S.). S.W. acknowledges the Junior Research Associate (JRA) Program from RIKEN and JSPS for a Young Scientist Fellowship.

Author contributions

S.W. and Y.I. conceived the project. S.W. designed and performed all experiments. X.W. and N.U. co-designed the experiments. S.W. and L.K. conducted the theoretical studies. P.S. and F.A. analyzed the data of retardation imaging. S.W., T.A., Z.D., and Y.I. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with the input of all other authors. The manuscript reflects the contributions of all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jun Lu, Gurvinder Singh, and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this work are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided in this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-54217-x.

References

- 1.Zhu, J. et al. Protein assembly by design. Chem. Rev.121, 13701–13796 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li, Z., Fan, Q. & Yin, Y. Colloidal self-assembly approaches to smart nanostructured materials. Chem. Rev.122, 4976–5067 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goor, O. J. G. M., Hendrikse, S. I. S., Dankers, P. Y. W. & Meijer, E. W. From supramolecular polymers to multi-component biomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev.46, 6621–6637 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato, K. et al. Peptide supramolecular materials for therapeutics. Chem. Soc. Rev.47, 7539–7551 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boles, M. A., Engel, M. & Talapin, D. V. Self-assembly of colloidal nanocrystals: from intricate structures to functional materials. Chem. Rev.116, 11220–11289 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien, M. N., Lin, H.-X., Girard, M., de la Cruz, M. O. & Mirkin, C. A. Programming colloidal crystal habit with anisotropic nanoparticle building blocks and DNA bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 14562–14565 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grzelczak, M., Liz-Marzán, L. M. & Klajn, R. Stimuli-responsive self-assembly of nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev.48, 1342–1361 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mu, R. et al. Stimuli-responsive peptide assemblies: Design, self-assembly, modulation, and biomedical applications. Bioact. Mater.35, 181–207 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perlmutter, J. D. & Hagan, M. F. Mechanisms of virus assembly. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem.66, 217–239 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popp, D. & Robinson, R. C. Supramolecular cellular filament systems: How and why do they form? Cytoskeleton69, 71–87 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPhedran, R. C. & Parker, A. R. Biomimetics: Lessons on optics from nature’s school. Phys. Today68, 32–37 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagan, M. F. & Grason, G. M. Equilibrium mechanisms of self-limiting assembly. Rev. Mod. Phys.93, 025008 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogi, S., Sugiyasu, K., Manna, S., Samitsu, S. & Takeuchi, M. Living supramolecular polymerization realized through a biomimetic approach. Nat. Chem.6, 188–195 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weyandt, E. et al. Controlling the length of porphyrin supramolecular polymers via coupled equilibria and dilution-induced supramolecular polymerization. Nat. Commun.13, 248 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, X. et al. Cylindrical block copolymer micelles and co-micelles of controlled length and architecture. Science317, 644–647 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacFarlane, L., Zhao, C., Cai, J., Qiu, H. & Manners, I. Emerging applications for living crystallization- driven self-assembly. Chem. Sci.12, 4661–4682 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vreeland, E. C. et al. Enhanced nanoparticle size control by extending LaMer’s mechanism. Chem. Mater.27, 6059–6066 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall, C. R., Staudhammer, S. A. & Brozek, C. K. Size control over metal–organic framework porous nanocrystals. Chem. Sci.10, 9396–9408 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claessens, M. M. A. E., Semmrich, C., Ramos, L. & Bausch, A. R. Helical twist controls the thickness of F-actin bundles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA105, 8819–8822 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang, Y., Meyer, R. B. & Hagan, M. F. Self-limited self-assembly of chiral filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett.104, 258102 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iizuka, E. The effects of magnetic fields on the structure of cholesteric liquid crystals of polypeptides. Polym. J.4, 401–408 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiang, J. et al. Electrically tunable laser based on oblique heliconical cholesteric liquid crystal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA113, 12925–12928 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medle Rupnik, P., Lisjak, D., Čopič, M., Čopar, S. & Mertelj, A. Field-controlled structures in ferromagnetic cholesteric liquid crystals. Sci. Adv.3, e1701336 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen, T. et al. Ultrasensitive magnetic tuning of optical properties of films of cholesteric cellulose nanocrystals. ACS Nano14, 9440–9448 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otaki, M., Nimori, S. & Goto, H. Oriented quasi-domain structure of helical spin polymers prepared by electrochemical polymerization in a cholesteric liquid crystal under a magnetic field, showing a helical stripe magnetic domain. Mater. Adv.4, 3292–3302 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, Z. et al. A magnetic assembly approach to chiral superstructures. Science380, 1384–1390 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, P.-X., Hamad, W. Y. & MacLachlan, M. J. Structure and transformation of tactoids in cellulose nanocrystal suspensions. Nat. Commun.7, 11515 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyström, G., Arcari, M. & Mezzenga, R. Confinement-induced liquid crystalline transitions in amyloid fibril cholesteric tactoids. Nat. Nanotech.13, 330–336 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siavashpouri, M. et al. Molecular engineering of chiral colloidal liquid crystals using DNA origami. Nat. Mater.16, 849–856 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barry, E., Beller, D. & Dogic, Z. A model liquid crystalline system based on rodlike viruses with variable chirality and persistence length. Soft Matter5, 2563–2570 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith, G. P. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science228, 1315–1317 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dogic, Z., Purdy, K. R., Grelet, E., Adams, M. & Fraden, S. Isotropic-nematic phase transition in suspensions of filamentous virus and the neutral polymer Dextran. Phys. Rev. E69, 051702 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalil, A. S. et al. Single M13 bacteriophage tethering and stretching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA104, 4892–4897 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, B. Y. et al. Virus-based piezoelectric energy generation. Nat. Nanotech.7, 351–356 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dogic, Z. Surface freezing and a two-step pathway of the isotropic-smectic phase transition in colloidal rods. Phys. Rev. Lett.91, 165701 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barry, E. & Dogic, Z. Entropy driven self-assembly of nonamphiphilic colloidal membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107, 10348–10353 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibaud, T. et al. Reconfigurable self-assembly through chiral control of interfacial tension. Nature481, 348–351 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, T., Zan, X., Winans, R. E., Wang, Q. & Lee, B. Biomolecular assembly of thermoresponsive superlattices of the tobacco mosaic virus with large tunable interparticle distances. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.52, 6638–6642 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma, P., Ward, A., Gibaud, T., Hagan, M. F. & Dogic, Z. Hierarchical organization of chiral rafts in colloidal membranes. Nature513, 77–80 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung, B., Wensink, H. H. & Grelet, E. Depletion-driven morphological transitions in hexagonal crystallites of virus rods. Soft Matter15, 9520–9527 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu, M., Zheng, X., Grebe, V., Pine, D. J. & Weck, M. Tunable assembly of hybrid colloids induced by regioselective depletion. Nat. Mater.19, 1354–1361 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torbet, J. & Maret, G. High-field magnetic birefringence study of the structure of rodlike phages Pf1 and fd in solution. Biopolymers20, 2657–2669 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Photinos, P., Rosenblatt, C., Schuster, T. M. & Saupe, A. Magnetic birefringence study of isotropic suspensions of tobacco mosaic virus. J. Chem. Phys.87, 6740–6744 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen, M. R., Mueller, L. & Pardi, A. Tunable alignment of macromolecules by filamentous phage yields dipolar coupling interactions. Nat. Struct. Biol.5, 1065–1074 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang, L., Gibaud, T., Dogic, Z. & Lubensky, T. C. Entropic forces stabilize diverse emergent structures in colloidal membranes. Soft Matter12, 386–401 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang, L. & Lubensky, T. C. Chiral twist drives raft formation and organization in membranes composed of rod-like particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA114, E19–E27 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan, C. N., Tu, H., Pelcovits, R. A. & Meyer, R. B. Theory of depletion-induced phase transition from chiral smectic-A twisted ribbons to semi-infinite flat membranes. Phys. Rev. E82, 021701 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rajabi, M., Lavrentovich, O. & Shribak, M. Instantaneous mapping of liquid crystal orientation using a polychromatic polarizing microscope. Liq. Cryst.50, 181–190 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lettinga, M. P., Barry, E. & Dogic, Z. Self-diffusion of rod-like viruses in the nematic phase. Europhys. Lett.71, 692 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lettinga, M. P. & Grelet, E. Self-diffusion of rodlike viruses through smectic layers. Phys. Rev. Lett.99, 197802 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maniatis, T. Fritsch, E. F. Sambrook, J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York, (1982).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this work are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided in this paper.