Dear Editor,

A mandatory gender-based quota system in nursing school admission has potentially resulted in significant gender inequality in the healthcare workforce for many decades in Bangladesh. As we all know, gender equity is a global goal, and reducing inequities in all sectors is critical for a more just and inclusive society [1]. The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasize “Gender Equality” (Goal 5) and “Reduced Inequalities” (Goal 10), with a target to achieve these by 2030 [2]. Literature suggests that Bangladesh has made some progress and is on track to potentially meet the SDGs within the expected timeframe [3]. However, despite this advancement, the country has lagged in nursing education by implementing a gender-based quota system that limits male participation in nursing education. The gender-based quota system in nursing school admission in Bangladesh contradicts the UN's goals of gender equality (SDG 5) and reducing inequalities (SDG 10) and assists in saving inequalities within an important healthcare workforce.

With disregarding SDGs, gender inequality in nursing school admission has persisted historically in Bangladesh, with the participation of male candidates forcibly limited to just 10 % in public and 20 % in private schools under the updated policy 2023, while 90 % of the seats are reserved for female candidates in public and 80 % of the seats for female candidates in private schools [4]. Previously, the 2019 policy restricted male candidates' admissions to only 10 %, both in public and private nursing schools [5]. It is unclear why 10 % of seats were increased for male candidates in private schools by the updated policy 2023 but not in public schools, revealing the gender inequalities framework within the policy itself. Such inequalities reduce the diversity in the nursing workforce, and a more diverse workforce could certainly enhance patient care outcomes.

The gender-based quota system may create a two-fold disadvantage for male candidates, especially for those from economically underprivileged backgrounds. In Bangladesh, public school education is mostly free of charge, while private education is fully paid out of pocket. According to recent studies, the family's economic status significantly influences enrollment in private schools in Bangladesh [6,7]. Thus, it might be difficult for private nursing schools to find that 90 % of their candidates are female and solvent. The push from private institutions to increase the male quota from 10 % to 20 % may have influenced the updated 2023 policy but requires further investigation. Moreover, a 10 % increase for private schools but not in public schools could disproportionately impact economically disadvantaged candidates, as the additional seats would only be accessible to affluent male students, potentially introducing new forms of inequality, such as economic inequalities within the nursing school admission system.

This discriminatory gender-based quota system has contributed to a significant underrepresentation of male in nursing in Bangladesh. Moreover, the small number of male candidates who manage to get admission may often face social stigma and isolation, as they represent a small minority in their classes [8]. In a hypothetical class of 50 students, only about five are male, making it difficult for them to fully engage in academic and social aspects as they have 45 female friends but do not have that many male friends in the class. With such limited admission opportunities, many talented and capable male students cannot pursue nursing education despite a strong interest in the field to contribute to the health system. In a highly populated country like Bangladesh, where skilled healthcare services are in constant demand, it is crucial to ensure that nursing education is accessible to all candidates, regardless of their gender identity.

The long-imposed gender-based quota system in nursing school admission may not only discriminate against male candidates but also limit the overall progress of the nursing profession in the country. Indeed, this should be counted as a critical issue in the health system so that many talented male candidates can come to nursing and contribute significantly to the field. Without their participation, the nursing profession misses out on the potential of 50 % of the talent pool. This long-term discriminatory quota system may affect the skills, quality of care, research, and innovation in nursing in Bangladesh. A qualified nursing workforce saves lives, while an unskilled force can risk the lives of millions [8]. Therefore, it is essential to determine whether we honestly prioritize a qualified nursing workforce for future Bangladesh or leave nursing as it is while other countries are constantly achieving healthcare milestones.

Bangladesh has never preferred a gender-based quota system for medical school admissions. According to a study based on the data from 2015 to 2016, 48 % of the medical students were female, and 52 % were male, indicating a slightly more balanced gender distribution [9]. The study also reported that Bangladesh has 48 % male and 52 % female registered physicians [9]. Thus, gender inequalities among registered physicians are certainly ignorable in Bangladesh. However, at the core of healthcare, nursing is a female-dominated profession. The participation of females is undoubtedly higher worldwide, but enforcing a mandatory 10 % gender-based quota for whatever reason in its admission system to limit the access of male candidates who are interested in contributing to the health system as a skilled workforce raises serious questions that deserve significant attention. The potential comparison of the balanced representation in medical school admissions and the sky-touching imbalance in nursing admissions makes a pressing issue for immediate reform.

Unlike other fields of education in Bangladesh, the mandatory gender-based quota system in nursing education is exceptionally enforced. This raised serious questions about the rationale behind this approach: why restrict male candidates if they are interested in pursuing a career in nursing? We tried to answer this question by reviewing the literature on whether the gender-based quota system in nursing school admissions was supported by any research in Bangladesh while upholding nursing standards. However, our investigation found no research supporting such a rationale within the context of Bangladesh. There is also no global consensus for such a compulsory restriction on male participation in nursing education nor any evidence supporting the necessity of this gender-based quota system. This discriminatory gender-based quota system has persisted for many decades without the support of any strong justification or scientific evidence. In such a situation in nursing education in Bangladesh, it is crucial to question why this mandatory gender-based quota persisted for decades, seemingly serving certain agendas of certain groups within healthcare rather than prioritizing patient care with a skilled workforce. Any supporting evidence on imposing a compulsory gender-based quota system in nursing school admission would be interesting to read. We hope whoever the body is responsible for this status quo will provide baseline evidence to the readers for doing so. In July 2024, the quota reform movement in Bangladesh highlighted the issue of discriminatory quota systems across various public service employment in the country [10], and we think that the silent and long-time gender-based quota system in nursing school admission should not be an exception. The global community and local stakeholders must investigate this issue and work towards creating a more equitable and inclusive nursing education for all entities in Bangladesh.

The World Bank projected only 0.6 nurses and midwives for 1000 people in Bangladesh as of 2024, an alarmingly low fig. [11]. In comparison, a neighbouring country, India, has 1.7 nurses and midwives per 1000 people, while Finland, with the highest ratio globally, has 22.3 nurses and midwives per 1000. It should be investigated if the gender-based quota system in nursing school admission is associated with the nurse shortage in Bangladesh. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), male nurses' participation was 62.3 % in 2010, but this figure dropped significantly to 5.9 % by 2017, 8.8 % in 2018, 10 % in 2020, and 4.5 % by 2021 in Bangladesh [12]. This sharp decline in male participation in the nursing workforce may have happened due to the mandatory gender-based quota system in the nursing school admissions stating its action, which likely contributed drastically to the reduced participation of males in nursing.

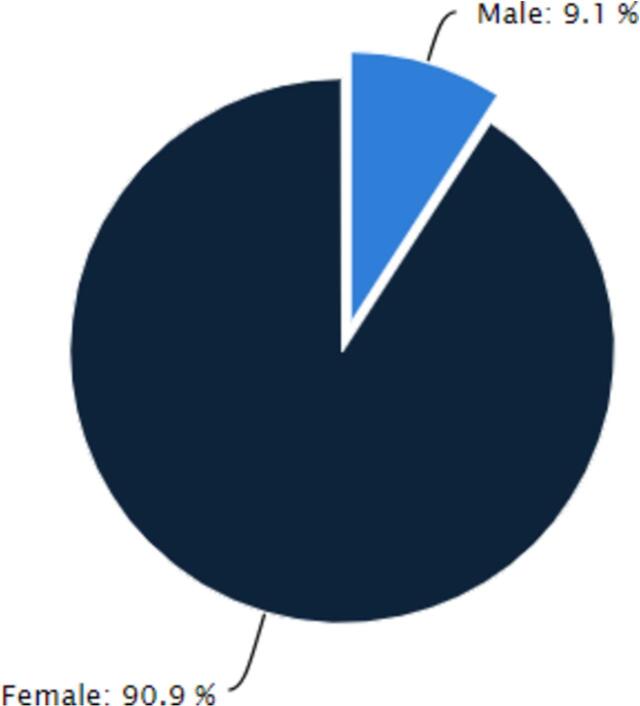

Data from the Directorate General of Nursing and Midwifery (DGNM) shows that as of September 10, 2024, there were 44,858 registered nurses employed by the government, with only 9.10 % being male nurses (Fig. 1) [13]. There is no gender-based quota in the government job recruitment system, but a 10 % male quota implemented in the nursing school admission system is assumed to be responsible for this significant gender inequality. Along with gender inequalities, the geographic inequalities in nurses' employment in the public sector also further highlighted these inequalities, with Dhaka having the highest concentration of nurses (38.10 %), while regions such as Mymensingh (5.64 %) and Sylhet (5.56 %) lag far behind (Table 1), which require to understand in further research if the gender inequalities have any influence on these inequalities.

Fig. 1.

The distribution of nurses' employment in the public sector by gander in Bangladesh (n = 44,858) [13].

Footnote: This figure was found on the DGNM website as of September 09, 2024 [13].

Table 1.

The distribution of nurses' employment in the public sector across Bangladesh (n = 44,858).

| Divisions | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Dhaka | 17,097 | 38.10 % |

| Rajshahi | 5702 | 12.71 % |

| Chattogram | 5685 | 12.67 % |

| Rangpur | 4373 | 9.75 % |

| Khulna | 4235 | 9.44 % |

| Barishal | 2744 | 6.12 % |

| Mymensingh | 2529 | 5.64 % |

| Sylhet | 2493 | 5.56 % |

Footnote: This table was made based on the data available on the DGNM website as of September 09, 2024 [13].

The continuation of a gender-based quota system in nursing school admission in Bangladesh is both unfair and detrimental to the advancement of nursing in this era of modern healthcare. This historical gender-based quota system has also reduced the diversity in the nursing workforce. The policy makers' consensus to impose a mandatory gender-based quota in nursing school admission that solely aims to limit male participation reinforces man-made and intentional gender inequalities, which firmly contradict the UN's SDGs, and this may be associated with restricting the overall progress of the healthcare sector of Bangladesh. To address this concern, we urge the stakeholders to take prompt action to evaluate and revise the necessity of nourishing this controversial gender-based quota system for nursing school admission. We believe that removing the gender-based quota from nursing school admission would allow talented individuals, regardless of gender identity, to pursue nursing as a career. This inclusive strategy would open a new door so that everyone, regardless of gender identity, has equal opportunities to contribute to the nursing workforce, thereby strengthening the healthcare system of Bangladesh. Furthermore, assessing and addressing social stigmas towards male nurses may be perceived due to the impact of the gender-based quota system and building a supportive environment throughout nursing education should be prioritized. This can be accomplished through awareness campaigns and promoting a culture honouring nursing professionals, regardless of gender identity. Finally, we encourage stakeholders, governments, healthcare leaders, local regulatory bodies, and global organizations to participate in this debate and advocate for an equitable and merit-based admission policy that will benefit the building of stronger healthcare in Bangladesh.

Funding

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shimpi Akter: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Masuda Akter: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Sopon Akter: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Humayun Kabir: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Shimpi Akter, Email: shimpi.akter@gmail.com, akter.shimpi@gmail.com.

Humayun Kabir, Email: humayun.kabir03@northsouth.edu.

References

- 1.Gupta G.R., Oomman N., Grown C., Conn K., Hawkes S., Shawar Y.R., et al. Gender equality and gender norms: framing the opportunities for health. The Lancet. 2019;393:2550–2562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou J.R. A Scoping Review of Ontologies Relevant to Design Strategies in Response to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Sustainability. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/SU131810012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khasru S.M., Nahreen A., Radia M.A. Social Development and the Sustainable Development Goals in South Asia. 2019. SDGs in Bangladesh: promises, prospects and opportunities; pp. 23–48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Bangladesh Gazette . BNMC [Internet] 9 Mar 2023. Nursing and Midwifery Admission Policy 2023; pp. 3165–3171.https://bnmc.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bnmc.portal.gov.bd/page/b5bf8666_ee6e_471b_b903_fc0463e87111/2023-06-12-05-05-9f1858b4012f5df4bf92e2a4b9f486e9.pdf [cited 30 Sep 2024]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Bangladesh Gazette . BNMC [Internet] 10 Dec 2019. Nursing and Midwifery Admission Policy 2019; pp. 25543–25547.https://bnmc.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bnmc.portal.gov.bd/page/b5bf8666_ee6e_471b_b903_fc0463e87111/2019-12-10-22-44-5c6297380daa99aa1a81a50145267b86.pdf [cited 30 Sep 2024]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nobi M.N. A comparative study of the socioeconomic profile of public and private University students in Bangladesh. The Chittagong University J Soc Sci. 2012;30:43–56. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322869644 Available: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehedi M., Emon H., Abtahi A.T., Jhuma S.A. 2023. Factors Influencing College Student’s Choice of a University In Bangladesh. [cited 30 Sep 2024] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salvador J.T., Mohammed Alanazi B.M. Men’s experiences facing nurses stereotyping in Saudi Arabia: a phenomenological study. Open Nurs J. 2024:18. doi: 10.2174/0118744346299229240321052429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hossain P., Das Gupta R., YarZar P., Jalloh M.S., Tasnim N., Afrin A., et al. ‘Feminization’ of physician workforce in Bangladesh, underlying factors and implications for health system: insights from a mixed-methods study. PloS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0210820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amnesty International What is happening at the quota-reform protests in Bangladesh? 2024. https://amnesty.ca/features/quota-reform-protests-bangladesh/ [cited 8 Sep 2024]. Available:

- 11.Worldbank Nurses and Midwives (per 1,000 people) | Data. 9 Sep 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.NUMW.P3 [cited 8 Sep 2024]. Available:

- 12.WHO Nursing Personnel by Sex (%) 20 May 2024. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/nurses-by-sex- [cited 30 Sep 2024]. Available:

- 13.DGNM Directorate General of Nursing and Midwifery. 9 Sep 2024. http://pmis.dgnm.gov.bd/ [cited 8 Sep 2024]. Available: