Highlights

-

•

Integration of radiomics and pathomics features yields a robust predictive model for HCC prognosis.

-

•

Radiomics features from MRI and pathomics features from whole slide images contribute to personalized prognostic assessment.

-

•

The developed model holds promise for guiding personalized therapeutic strategies in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Radiomics, Pathomics, Overall survival, MRI

Abstract

Objective

This study aims to develop and validate a radiopathomics model that integrates radiomic and pathomic features to predict overall survival (OS) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients.

Materials and methods

This study involved 126 HCC patients who underwent hepatectomy and were followed for more than 5 years. Radiomic features were extracted from arterial-phase (AP) and portal venous-phase (PVP) MRI scans, whereas pathomic features were obtained from whole-slide images (WSIs) of the HCC patients. Using LASSO Cox regression, both radiomics and pathomics signatures were established. A combined radiopathomics nomogram for predicting OS was constructed and validated. The correlation between the radiopathomics nomogram and OS prediction was evaluated, demonstrating its potential clinical utility in prognosis assessment.

Results

We selected four radiomic features from the AP and PVP MRI scans to construct a signature, achieving a concordance index (C-index) of 0.739 in the training cohort and 0.724 in the validation cohort; these results indicate favourable 5-year OS prediction. Similarly, from 1,141 pathomics features extracted from WSIs, 15 were chosen for a pathomics signature, which had C-indexes of 0.821 and 0.808 in the training and validation cohorts, respectively. The most robust performance was delivered by a radiopathomics nomogram, with C-index values of 0.840 in the training cohort and 0.875 in the validation cohort. Decision curve analysis (DCA) confirmed the highest net benefit achievable by the combined radiopathomics nomogram.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that the radiopathomics nomogram can serve as a predictive marker for hepatectomy prognosis in HCC patients and has the potential to enhance personalized therapeutic approaches.

Introduction

Liver cancer ranks as the third leading cause of cancer-related death globally [1]. In 2020 alone, it caused more than 830,000 deaths worldwide, and projections suggest a 50 % increase in mortality over the next two decades [2]. Additionally, it was the second leading cause of premature cancer-related deaths that year [3]. Liver cancer, predominantly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), accounts for approximately 90 % of all cases [4]. An effective prognosis assessment is a critical component of HCC patient care [5]. Surgical resection can yield a 5-year survival rate of 70 % for early-stage HCC [6]. Unfortunately, most cases are diagnosed at an intermediate to advanced stage [6]. Consequently, the overall survival rate following hepatectomy for HCC patients is unsatisfactory, with a 5-year survival rate of only 50 % or even lower [5,7].

Currently, the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system is globally recognized as the primary staging system for HCC, guiding both prognostic prediction and treatment decisions [8]. However, there is notable variance in initial treatment selection between the BCLC system recommendations and actual clinical practice, especially among East Asian patients [9]. The albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade, which assesses the survival rates of HCC patients via laboratory indicators, plays a role, yet it lacks specificity and effectiveness in predicting the postoperative survival of HCC patients [10]. This lack of specificity and effectiveness highlights the pressing need to identify novel biomarkers associated with HCC prognosis.

Radiomics uses powerful computing tools to obtain detailed data from medical images. These data include quantitative features that can predict tumour behaviour, response to treatment, and overall outcomes, as observed in breast, pancreatic, and lung cancers [11]. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an essential diagnostic tool for HCC [12,13]. At present, radiomics-based MRI is primarily applied to predict postoperative pathological grading [[13], [14], [15]]. Currently, there is relatively limited research on the use of radiomics-based MRI models for predicting long-term survival after the resection of HCC. Radiomics can improve predictive models by revealing tumour heterogeneity at the macroscopic level [16], but it may overlook microscopic tumour features. In some cases, histopathological details from microscopic observations are essential for a comprehensive description of the lesion; however, this correlation is often overlooked [17].

Pathomics utilizes data from digital pathology image analysis to generate quantitative features characterizing tissue sample phenotypes from whole slide images (WSIs). This supplements tumour heterogeneity and enhances predictive models to determine a diagnosis or forecast survival outcomes [18]. Current reports suggest that pathomics holds significant promise for predicting gene mutations and prognosis in HCC patients [19,20]. Given that both radiological and histopathological data provide complementary information about tumour biology, integrating radiological information on macroscopic tumour features with histopathological data on microscopic local lesions may enhance tumour characterization, lead to the construction of more robust models, and improve long-term survival prediction accuracy in HCC patients. The scarcity of research on predicting postoperative prognosis in HCC patients via a combination of MRI radiomics features and histopathological features emphasizes the innovation of this research approach.

Hence, the objective of this research was to develop a predictive model integrating an MRI radiomics signature with a pathomics signature derived from WSIs to predict overall survival (OS) following hepatic resection.

Materials and methods

Patient population

The Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University granted ethical approval for this study on April 8, 2024 (2024-K100–01), adhering to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Declaration of Istanbul. Given its retrospective nature, the requirement for individual informed consent was waived. The study was conducted from December 2015 to December 2018 and involved consecutive patients with HCC who underwent surgical resection and had pathological confirmation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) underwent hepatectomy for HCC without distant metastasis; ii) received enhanced MRI examination no more than 2 months before surgery; iii) had HCC pathology tissue HE slides digitized as WSIs; iv) was classified under the BCLC staging system as stages A and B; and v) completed a minimum of 5 years of follow-up after surgery or until death. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) received preoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or embolization therapy; ii) had a history of partial liver resection; iii) had concurrent cancers at other sites; iv) had incomplete clinical or pathological report information; and v) had blurred images that prevented lesion identification. A total of 126 patients were enrolled at our hospital and underwent hepatectomy for HCC. These patients were randomly assigned to the training and validation cohorts at a ratio of 7:3 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patient cohort selection.

The baseline patient data included age, sex, tumour characteristics (size and presence of liver cirrhosis), intraoperative haemorrhage, postoperative management, BCLC staging, and follow-up parameters (timing and survival) (Table 1). In addition to these parameters, routine laboratory investigations were also performed. Follow-up intervals were typically every 3‒6 months post-surgery and were guided by the alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and imaging results. Tumour recurrence was assessed via radiological methods. OS was determined from the time of surgery until death or the last follow-up assessment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in the training and validation cohorts.

| Characteristics | ALL | Training cohort (n = 88) | Validation cohort (n = 38) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.50802104 | |||

| <60 | 96(76.19) | 69(78.51) | 27(71.05) | |

| ≥60 | 30(23.81) | 19(21.59) | 11(28.95) | |

| Sex | 0.60648455 | |||

| Male | 108(85.71) | 74(84.09) | 34(89.47) | |

| Female | 18(14.29) | 14(15.91) | 4(10.53) | |

| MVI | 1 | |||

| Absent | 92(73.02) | 64(72.73) | 28(73.68) | |

| Present | 34(26.98) | 24(27.27) | 10(26.32) | |

| Size (cm) | 1 | |||

| <5 | 89(70.63) | 62(70.45) | 27(71.05) | |

| ≥5 | 37(29.37) | 26(29.55) | 11(28.95) | |

| PLT (109/L) | 0.16113477 | |||

| <100 | 114(90.48) | 77(87.50) | 37(97.37) | |

| ≥100 | 12(9.52) | 11(12.50) | 1(2.63) | |

| TBiL(μmol/L) | 0.69410402 | |||

| <20 | 110(87.30) | 78(88.64) | 32(84.21) | |

| ≥20 | 16(12.70) | 10(11.36) | 6(15.79) | |

| DBiL(μmol/L) | 1 | |||

| <6 | 98(77.78) | 68(77.27) | 30(78.95) | |

| ≥6 | 28(22.22) | 20(22.73) | 8(21.05) | |

| ALB(g/L) | 1 | |||

| <35 | 11(8.73) | 8(9.09) | 3(7.89) | |

| ≥35 | 115(91.27) | 80(90.91) | 35(92.11) | |

| ALT(U/L) | 0.99240653 | |||

| <40 | 78(61.90) | 55(62.50) | 23(60.53) | |

| ≥40 | 48(38.10) | 33(37.50) | 15(39.47) | |

| AST(U/L) | 0.86997167 | |||

| <45 | 100(79.37) | 69(78.41) | 31(81.58) | |

| ≥45 | 26(20.63) | 19(21.59) | 7(18.42) | |

| PT (seconds) | 1 | |||

| <12.1 | 89(70.63) | 62(70.45) | 27(71.05) | |

| ≥12.1 | 37(29.37) | 26(29.55) | 11(28.95) | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.43969184 | |||

| <7 | 41(32.54) | 31(35.23) | 10(26.32) | |

| ≥7 | 85(67.46) | 57(64.77) | 28(73.68) | |

| HBsAg | 0.65553371 | |||

| Negative | 14(11.11) | 11(12.50) | 3(7.89) | |

| Positive | 112(88.89) | 77(87.50) | 35(92.11) | |

| Postoperativetreatment | 0.35526882 | |||

| Absent | 109(86.51) | 74(84.09) | 35(92.11) | |

| Present | 17(13.49) | 14(15.91) | 3(7.89) | |

| Hypertension | 0.43206544 | |||

| Absent | 103(81.75) | 74(84.09) | 29(76.32) | |

| Present | 23(18.25) | 14(15.91) | 9(23.68) | |

| Diabetes | 1 | |||

| Absent | 111(88.10) | 78(88.64) | 33(86.84) | |

| Present | 15(11.90) | 10(11.36) | 5(13.16) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.95542276 | |||

| Absent | 41(32.54) | 28(31.82) | 13(34.21) | |

| Present | 85(67.46) | 60(68.18) | 25(65.79) | |

| BCLC | 0.36394414 | |||

| 0/A | 98(77.78) | 66(75.00) | 32(84.21) | |

| B | 28(22.22) | 22(25.00) | 6(15.79) | |

| Ascites | 1 | |||

| Absent | 108(85.71) | 75(85.23) | 33(86.84) | |

| Present | 18(14.29) | 13(14.77) | 5(13.16) | |

| Number | 0.10894466 | |||

| 1 | 104(82.54) | 69(78.41) | 35(92.11) | |

| >1 | 22(17.46) | 19(21.59) | 3(7.89) | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ML) | 0.12567065 | |||

| <200 | 55(43.65) | 34(38.64) | 21(55.26) | |

| ≥200 | 71(56.35) | 54(61.36) | 17(44.74) |

MVI, microvascular invasion; PLT, platelet; TBiL, total bilirubin; DBiL, direct bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALB, albumin; PT, prothrombin time; AFP, α-fetoprotein; HBsAg, Hepatitis B virus surface antigen; BCLC, Barcelona clinical liver cancer.

Image acquisition and segmentation

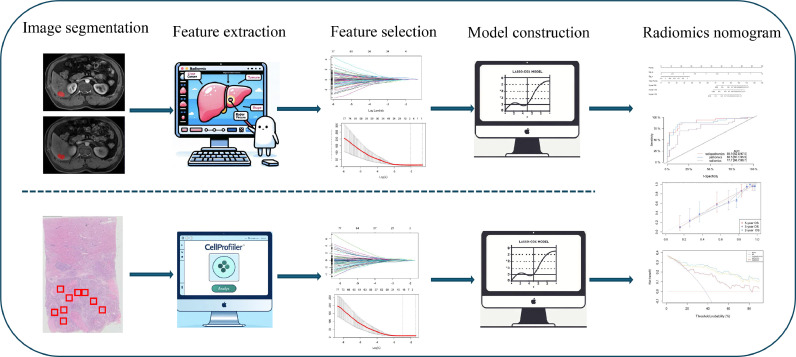

The study workflow is depicted in Fig. 2. Each patient underwent a MR examination of the liver no more than 2 months before surgery, including axial fat-suppressed arterial-phase (AP) and portal venous-phase (PVP) scans performed using a 3.0-T scanner. Further details about the MRI scanning protocol and acquisition variables can be found in Supplementary Information I. The tumour regions of interest (ROIs) in the MR images were manually delineated using ITK-SNAP software (version 3.8.0, http://www.itksnap.org/).

Fig. 2.

The workflow of the RSHCC, PSHCC, and nomogram (radiopathomics) models in this study. Radiomics features are extracted from arterial and portal venous phases of MRI, and pathomics features from WSI. Predictive factors are selected in the training group using the LASSO—Cox regression model. The RSHCC and PSHCC scores are calculated by a linear combination of selected features and applied to the validation group using the same formula. RSHCC radiomics signature of hepatocellular carcinoma, PSHCC pathomics signature of hepatocellular carcinoma, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, WSI whole slide image, LASSO least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

Pathological tissue slides were scanned using a slide scanner (SQS-120P) that was supplied by Shenzhen Shengqiang Technology Co., Ltd. (http://www.sqray.com/product/list) and had a pixel resolution of 20x. These slides were processed using Aperio ImageScope software (version 12.3.3). Pathologists selected 10 nonoverlapping representative slides with the highest number of tumour cells per case, each with a 512 × 512 pixel field of view. This selection was subsequently confirmed by another pathologist (Y T and Zb F).

Feature extraction and selection

Each patient's MRI data were normalized via Z scores to achieve standardized image intensities. The radiomic features were then extracted using the PyRadiomics package in the Python programming language. A total of 1834 features were extracted from the arterial and venous sequences, resulting in 3668 combined features and covering seven feature classes: shape, first-order, grey level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), grey level run length matrix (GLRLM), grey level size zone matrix (GLSZM), grey level difference matrix (GLDM), and neighbourhood grey tone difference matrix (NGTDM). Additional details regarding the extracted radiomic features are provided in Supplementary Information II.

For parallel analysis, pathomic features were extracted using CellProfiler (version 4.2.1), a freely available platform for the quantitative analysis of biological images [21,22]. In total, 1141 pathomic features were obtained. Additional details regarding the extracted pathomic features are provided in Supplementary Information III.

Both of the radiomic and pathomic features were standardized via Z scores. Spearman rank correlation coefficient analysis was subsequently conducted to evaluate the correlations between variables.

Construction of the PSHCC, RSHCC and radiopathomics nomogram

The literature was referenced in regard to predicting the prognosis of gastric cancer using a pathomics signature [18]. First, the LASSO Cox regression model was employed, implementing 10-fold cross-validation with the minimum criteria during model construction to select pathomic and radiomic features. Next, the optimal cutoff values for PSHCC and RSHCC were identified via the maximally selected rank statistics, dividing patients in the training cohort into high and low PSHCC and RSHCC groups. These identical cut-off values were then applied to the validation cohort. Additionally, to further improve prediction accuracy, a random survival forest (RSF) model was applied for predicting 5-year survival. This approach allowed for the handling of complex interactions between variables and was particularly suitable for high-dimensional datasets such as ours [23].

In the training cohort, univariate Cox regression analyses for OS included RSHCC, RSHCC, and clinicopathological characteristics. Variables with a significance level of P < 0.05 were then chosen for multivariate Cox regression analyses. Backwards stepwise regression was employed to identify independent predictors, and on the basis of these predictors, radiopathomics nomograms were constructed to predict OS.

To further evaluate the performance of the model, not only were the concordance index (C-index) and 5-year AUROC calculated, but additional metrics such as the accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score were also analysed. Calibration curves were generated to compare the agreement between the predicted and actual survival probabilities. Statistical differences between different models were compared using the DeLong test. Additionally, decision curve analysis was used to assess the clinical usefulness of the radiopathomics nomograms by evaluating the net benefits at different threshold probabilities. Ultimately, the nomograms were applied in the validation cohort to validate their discrimination, calibration, and clinical usefulness.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were evaluated with t tests, and categorical variables were assessed with chi-square tests. Following these initial assessments, Cox proportional hazards models were employed for both the univariate and multivariate analyses, yielding hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Subsequently, LASSO Cox regression analysis was conducted via the "glmnet" package, leading to the development of prognostic nomograms. These nomograms were then validated and evaluated for performance using the 'rms' package. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated using the riskRegression package. Additionally, decision curve analysis was performed using the stdcaR function. Furthermore, survival analysis was performed using the "survminer" package. Importantly, all tests were two-tailed, with P < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM) and R version 4.0.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

Patient population characteristics

In this study, we included a total of 126 patients, 85.7 % (108 out of 126) of whom were male. The median age was 52 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 48 to 53 years. Table 1 shows the clinical and pathological features of the training (n = 88) and validation (n = 38) cohorts. No significant differences were observed in the clinical or pathological characteristics between the two groups.

In the training cohort, the median follow-up duration was 61 months, ranging from 48 to 63 months, with a 5-year OS rate of 62.5 %. Conversely, the validation cohort had a median follow-up of 62 months, with a range from 60.5 to 69 months, achieving a five-year OS of 76.3 %.

Selection of radiomic and pathomic features

Radiomic and pathomic feature selection utilized 10-fold cross-validation to minimize the mean squared error and identify the optimal λ value (Fig. 3). Using this optimal value, the LASSO Cox regression model was fitted, retaining non-zero coefficient features. A total of 3668 radiomic features were extracted from the AP and PVP MR ROIs. The final RSHCC included 4 radiomic features (Supplementary Information IV). From the selected WSIs, 1141 features were extracted, and after selection, 15 non-zero coefficient features composed the PSHCC (Supplementary Information IV).

Fig. 3.

Feature selection method. The LASSO model, applying a tuning parameter (λ) and employing 10-fold cross-validation, selected radiomics (A, B) and pathomics (C, D) features based on the minimum mean squared error. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

Construction of the radiomics and pathomics signatures

The calculation formulas for the RSHCC and PSHCC are detailed in Supplementary Information IV, with data on the RSHCC and PSHCC for the validation cohort derived from the training cohort. The median (IQR) RSHCC values for the training and validation cohorts were −0.06267 (−0.17787∼0.09946) and 0.05540 (−0.05614∼0.358066), respectively. A comparative analysis revealed that there was no statistically significant difference in the RSHCC distribution between the two cohorts (median difference: −0.152; 95 % CI: −0.342∼0.059; P = 0.139). For PSHCC, the median (IQR) values for the training and validation cohorts were 0.081097 (−0.153477∼0.2084762) and −0.072664 (−0.26456∼0.342244), respectively. Similarly, the distribution of PSHCC between the two cohorts was not significantly different (median difference: 0.059; 95 % CI: −0.191∼0.051; P = 0.682).

The optimal cutoff values for RSHCC and PSHCC were 0.15 and 0.17, respectively, as evidenced by the analysis of the training cohort (Supplementary Information V). These cutoff values produced the highest standardized log-rank statistics. Utilizing these thresholds, patients in both the training and validation cohorts were stratified into high and low RSHCC groups, as well as high and low PSHCC groups. Analysis revealed that elevated levels of both RSHCC and PSHCC were significantly associated with increased mortality risk (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted based on the levels of RSHCC and PSHCC. OS for patients with high and low RSHCC in the radiomics training cohort (A) and validation cohort (B). OS for patients with high and low PSHCC in the pathomics training cohort (C) and validation cohort (D). OS overall survival, RSHCC radiomics signature of hepatocellular carcinoma, PSHCC pathomics signature of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Development and performance of the radiopathomics nomogram

In the univariate Cox regression analysis, RSHCC, PSHCC, MVI, number, and size were found to be correlated with OS in the training cohort (Table 2). Subsequent backwards stepwise multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed RSHCC and PSHCC as independent prognostic factors for OS, which were incorporated into a radiopathomics nomogram (Fig. 5A). In the training cohort, the C-index for the radiopathomics nomogram for predicting OS was notably high at 0.840 (95 % CI: 0.771∼0.899). The C-index values for the radiomics signature were 0.738 in the training cohort and 0.724 in the validation cohort. For the pathomics signature, the C-index values were 0.821 and 0.808 for the training and validation cohorts. The time-dependent ROC curve for predicting the 5-year OS with this nomogram yielded an area under the ROC curve (AUROC) of 0.899 (95 % CI: 0.824∼0.975) (Fig. 5B). In the validation cohort, the C-index for predicting the 5-year OS was also strong with a value of 0.875 (95 % CI: 0.775∼0.965), and the AUROC was 0.889 (95 % CI: 0.745∼1.000) (Fig. 5C). Additional performance parameters are presented in Table 3. The DeLong test was used to assess AUC differences among the radiomics model, pathomics model, and radiopathomics nomogram. In the validation cohort, P values for the AUC comparisons among the radiopathomics nomogram and both models exceeded 0.05 (Table 4). The calibration curves for both the training and validation cohorts (Fig. 6A, 6B) demonstrated robust concordance between the predicted and observed survival rates. Furthermore, decision curve analysis (DCA) indicated that the use of an imaging-pathologic nomogram for predicting OS provides significantly greater net benefits in both cohorts (Fig. 6C, 6D), emphasizing the clinical relevance of the radiopathomics nomogram.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of the radiopathomics and clinicopathological characteristics for overall survival in training cohort.

| Univariate analysis HR (95 % CI) | p_value | Multivariate analysis HR (95 % CI) | p_value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (<60 Vs ≥60) | 0.907 (0.394–2.091) | 0.819 | ||

| Sex (Male Vs Female) | 1.364 (0.563–3.304) | 0.492 | ||

| MVI (Absent Vs Present) | 2.686 (1.351–5.339) | 0.005 | ||

| Size (cm) (<5 Vs ≥5) | 2.255 (1.129–4.502) | 0.021 | ||

| PLT (109/L) (<100 Vs ≥100) | 0.560 (0.171–1.837) | 0.339 | ||

| TBiL (μmol/L) (<20 Vs ≥20) | 1.106 (0.389–3.147) | 0.850 | ||

| DBiL (μmol/L) (<6 Vs ≥6) | 1.256 (0.585–2.712) | 0.555 | ||

| ALB(g/L) (<35Vs ≥35) | 0.703 (0.247–2.000) | 0.509 | ||

| ALT(U/L) (<40 Vs ≥40) | 1.79 (0.903–3.546) | 0.095 | ||

| AST(U/L) (<45 Vs ≥45) | 2.062 (0.999–4.256) | 0.050 | ||

| PT (seconds)(<12.1Vs ≥12.1) | 1.501 (0.738–3.052) | 0.262 | ||

| AFP (ng/mL) (<7 Vs ≥7) | 1.435 (0.683–3.016) | 0.341 | ||

| HBsAg (Negative Vs Positive) | 1.557 (0.475–5.105) | 0.464 | ||

| Postoperativetreatment (Absent Vs Present) | 1.400 (0.608–3.227) | 0.429 | ||

| Hypertension (Absent Vs Present) | 0.415 (0.127–1.361) | 0.147 | ||

| Diabetes (Absent Vs Present) | 0.722 (0.220–2.366) | 0.590 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis (Absent Vs Present) | 1.22 (0.567–2.625) | 0.611 | ||

| BCLC (AVs B) | 1.601 (0.776–3.303) | 0.203 | ||

| Ascites (Absent Vs Present) | 0.825 (0.290–2.347) | 0.719 | ||

| Number (1 Vs >1) | 1.899 (0.903–3.994) | 0.091 | ||

| Intraoperative blood loss (ML) (<200 Vs ≥200) | 1.533 (0.729–3.221) | 0.260 | ||

| RSHCC | 9.455 (3.872–23.087) | <0.001 | 1.838 (1.097–3.079) | 0.021 |

| PSHCC | 11.928 (5.485–25.941) | <0.001 | 4.971 (2.524–9.791) | <0.001 |

MVI, microvascular invasion; PLT, platelet; TBiL, total bilirubin; DBiL, direct bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALB, albumin; PT, prothrombin time; AFP, α-fetoprotein; HBsAg, Hepatitis B virus surface antigen; BCLC, Barcelona clinical liver cancer; RSHCC, radiomics signature of hepatocellular carcinoma; PSHCC, pathomics signature of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fig. 5.

Radiopathomics Nomogram for Predicting Overall Survival in Hepatectomy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. (A) A radiopathomics nomogram was established using the train cohort, incorporating both radiomics and pathomics signatures. ROC for Predicting 5-Year OS Using Radiomics signature, Pathomics signature, and a radiopathomics nomogram in the train cohort (B) and the validation cohort (C). OS Overall Survival, HCC Hepatocellular Carcinoma. ROC receiver operating characteristic.

Table 3.

Performance of a model predicting 5-year OS for HCC resection in training and validation cohorts.

| Cohort | Model | Acc (95 % CI) | Sen | Spe | PPV | NPV | F1 | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| training cohort | pathomics | 0.852 (0.761–0.919) | 0.836 | 0.878 | 0.92 | 0.763 | 0.876 | 0.92 |

| radiomics | 0.795 (0.696–0.874) | 0.854 | 0.697 | 0.825 | 0.742 | 0.829 | 0.825 | |

| radiopathomics nomogram | 0.864 (0.774–0.928) | 0.855 | 0.879 | 0.922 | 0.784 | 0.887 | 0.922 | |

| validation cohort | pathomics | 0.790 (0.627–0.904) | 0.759 | 0.89 | 0.957 | 0.533 | 0.846 | 0.957 |

| radiomics | 0.763 (0.598–0.886) | 1 | 0 | 0.763 | NaN | 0.866 | 0.763 | |

| radiopathomics nomogram | 0.842 (0.688–0.940) | 0.828 | 0.889 | 0.96 | 0.615 | 0.889 | 0.96 |

OS, Overall Survival; HCC, Hepatocellular Carcinoma; Acc, Accuracy; Sen, Sensitivity; Spe, Specificity; PPV, Positive Predictive Value; NPV, Negative Predictive Value; F1, F1_score.

Tabel 4.

Comparison of ROC curves between pathomics, radiomics, and radiopathomics models using the DeLong test.

| Cohort | Model | AUC | Delong test | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| training cohort | pathomics | 0.88 | VS radiomics | 0.11 |

| radiomics | 0.79 | VS radiopathomics | 0.02 | |

| radiopathomics | 0.9 | VS pathomics | 0.18 | |

| validation cohort | pathomics | 0.85 | VS radiomics | 0.44 |

| radiomics | 0.74 | VS radiopathomics | 0.16 | |

| radiopathomics | 0.9 | VS pathomics | 0.18 |

Fig. 6.

Calibration curves and DCA for the radiomics signature, pathomics signature, and a radiopathomics nomogram. Calibration curves for three models on the training cohort (A) and validation cohort (B). DCA for three models on the training cohort (C) and validation cohort (D). DCA Decision curve analysis.

Prediction of 5-year OS via the RSF model

The RSF model was built using the clinicopathological features from Table 2. As 400 survival trees were constructed, the prediction error rate stabilized at a low level (Supplementary Fig. 3A). PSHCC and RSHCC were the two most important features (Supplementary Fig. 3B). The time-dependent ROC curve of the RSF model for predicting 5-year OS had AUROCs of 0.881 and 0.870 for the training and validation cohorts, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3C).

Discussion

In this study, we obtained four radiomic features from AP and PVP MRI scans, along with 15 pathomic features extracted from WSIs. By utilizing LASSO Cox regression, we constructed separate radiomics and pathomics signatures, which we then integrated into a comprehensive radiopathomics model. We confirmed the prognostic value of this radiopathomics model for HCC, thus enabling more precise risk stratification of HCC patients by clinical practitioners. Additionally, we observed that the RSF model demonstrated good performance in predicting 5-year OS, further supporting the importance of radiomic and pathomic features in prognostic assessment.

We primarily used the AUC and DCA to evaluate model performance. Although the radiopathomics model achieved a greater AUC than did the radiomics and pathomics models, especially in the validation cohort, it did not pass the DeLong test. This may be due to the small sample size, although it shows a certain trend. Moreover, DCA indicated that the radiopathomics model produced greater net benefits than the individual models did.

Radiomics, a prominent field in oncology, utilizes quantitative features extracted from medical images and converts them into metrics for precise and thorough lesion assessment, consequently delivering clinically pertinent diagnostic and prognostic insights [24]. Research exploring the predictive utility of radiomic features for overall post-hepatectomy survival in HCC patients is currently limited, with only a sparse body of relevant literature identified thus far. In their study, Zheng et al. [25] developed a combined model integrating radiomic features extracted from contrast-enhanced CT scans with clinical indicators to predict OS rates at 3 and 5 years. Both the training and validation cohorts achieved a C-index of 0.71, indicating favourable predictive ability. Similarly, Zhang et al. [26] used features extracted from multiple sequences of preoperative liver MR images, encompassing tumour, peritumoral, and normal liver parenchyma regions, to construct a radiomics model. By integrating clinical characteristics and imaging semantic features, a composite model was established to predict OS rates at 3 years, achieving high predictive ability. Wang et al. [27]. extracted radiomic features from T1-weighted imaging, T2-weighted imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging, and dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging to establish a combined radiomics model that integrated imaging features and clinical risk factors. This model also demonstrated good predictive performance for the OS rate at 5 years for post-hepatectomy HCC patients. In our study, we utilized radiomic features extracted from two dynamic contrast-enhanced sequences, the AP and PVP, to construct radiomics signatures for predicting 5-year OS. Similarly, this approach yielded satisfactory predictive performance.

Each MRI sequence provides distinct information. In particular, the AP and PVP enable the observation of dynamic changes in tumour blood flow at different time points, thereby offering an abundance of information for diagnosis and staging [28]. Consequently, this study focused on extracting radiomic features from these two phases to enhance the exploration of MRI sequence combinations and contribute to existing research on MRI radiomics for predicting the OS of post-hepatectomy HCC patients.

Pathomics is a novel tool capable of comprehensively extracting features, with the potential to improve tumour outcome estimation [29]. Furthermore, pathomics can seamlessly integrate into other omics methods to enhance model performance [16,29]. Pathomics has been utilized to predict treatment response in patients with breast cancer, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, gastric cancer, and colorectal cancer, as well as OS and progression-free survival in patients with HCC and colorectal cancer; in all of these cases, good predictive efficacy is observed [18,[29], [30], [31], [32], [33]]. In contrast to the pathomic features utilized by Shi et al. [30]. to assess OS, the pathological features in this study were extracted using CellProfiler software, which employs handcrafted feature-based approaches. CellProfiler is a free, open-source software that automatically measures phenotypes from biological images and has been used in digital pathology analysis with satisfactory performance [17,18,29,31]. This capability allowed us to extract effective features for stratifying HCC risk.

Building on the integration of pathomics with other omics features, as previously mentioned, we established a radiopathomics model in this study. By combining radiomics and pathomics signatures, the model aims to predict OS in post-hepatectomy HCC patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between a radiopathomics signature and the prognosis of HCC patients. OS, which serves as a pivotal indicator for assessing the efficacy of tumour treatments and predicting patient prognosis, has consistently played a crucial role in clinical practice. Thus, extensive gene expression data are utilized to predict the prognosis of cancer patients [34,35]. While molecular analysis offers precise risk assessment for tumours, its cost and complexity hinder its clinical application. This study maximizes the available clinical data to evaluate patient survival risk. In our study, while the radiomics and pathomics models performed well individually, our integrated model outperformed both of them. Combining both models may leverage tumour heterogeneity and enhance treatment efficacy. This was confirmed by the DCA on the validation cohort, indicating superior net benefits when compared with those from the individual models.

Regrettably, despite the initial collection of a substantial number of clinicopathological indicators, none were ultimately incorporated into the final model through univariate or multivariate analyses. Some studies have shown that the BCLC stage is an independent prognostic factor for HCC [26,30], whereas others have reported that the BCLC stage is not an independent risk factor [27]. The results of this study align with the latter. This discrepancy may be related to the specific clinical practice of BCLC, and the prognostic value of BCLC for HCC warrants further exploration. Additionally, stepwise regression analysis indicated that MVI may not be among the most independently influential factors in predicting HCC prognosis, a finding similar to that of Kim et al. [36].. These findings suggest that, in our study, the significance of MVI in explaining HCC patient prognosis may be relatively limited. However, its exclusion from the model could be due to its correlation or collinearity with other variables. Furthermore, the importance of MVI may vary depending on sample characteristics, study design, and other factors, underscoring the need for further research in larger sample populations to validate our findings.

Our study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective study, the models may not perform as well with "real-world" data, necessitating prospective validation. Second, the single-centre design and small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Despite these limitations, the observed trends indicate potential significance and highlight the need for further research. Third, the radiomic features from our study are solely derived from arterial- and portal venous-phase MR images, indicating a lack of diversity in sample features. Future research could address this by collecting multiple sequence data for feature enrichment. Therefore, it is imperative to perform prospective, international, multicentre clinical trials to further validate the robustness of the radiopathomics signature in this study.

In conclusion, we developed a radiopathomics signature based on features from MRI scans and WSIs to predict OS in post-hepatectomy HCC patients. This model serves as a potential tool for clinicians to stratify prognostic risks and aid in personalized clinical decision-making.

Informed consent statement

All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: 82060310.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lijuan Feng: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Wanyun Huang: Writing – original draft, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Xiaoyu Pan: Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis. Fengqiu Ruan: Visualization, Validation, Investigation. Xuan Li: Visualization, Validation, Investigation. Siyuan Tan: Visualization, Validation, Investigation. Liling Long: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2024.102174.

Contributor Information

Lijuan Feng, Email: fenglijuan2022@163.com.

Wanyun Huang, Email: fskhwy1204@163.com.

Xiaoyu Pan, Email: drpanxiaoyu@126.com.

Fengqiu Ruan, Email: Ruan00823@163.com.

Xuan Li, Email: lixuanytxy@163.com.

Siyuan Tan, Email: 13607862676@163.com.

Liling Long, Email: cjr.longliling@vip.163.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angeli-Pahim I., Chambers A., Duarte S., Zarrinpar A. Current trends in surgical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15(22):5378. doi: 10.3390/cancers15225378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumgay H., Arnold M., Ferlay J., et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 2022;77(6):1598–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet J.M., Kelley R.K., Villanueva A., et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2021;7(1):6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forner A., Reig M., Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1301–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilles H., Garbutt T., Landrum J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2022;34(3):289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Q., Li J., Liu F., et al. A radiomics nomogram for the prediction of overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Cancer Imag. 2020;20(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s40644-020-00360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel A., Cervantes A., Chau I., et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annal. Oncol. 2018;29:iv238–iv255. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee K.H., Choi G.H., Yun J., et al. Machine learning-based clinical decision support system for treatment recommendation and overall survival prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-center study. npj Digit Med. 2024;7(1):2. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00976-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudo M. Newly developed modified ALBI grade shows better prognostic and predictive value for hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liv. Cancer. 2022;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000521374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding-Theobald E., Louissaint J., Maraj B., et al. Systematic review: radiomics for the diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Alim. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;54(7):890–901. doi: 10.1111/apt.16563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrero J.A., Kulik L.M., Sirlin C., et al. Diagnosis, staging and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Published online 2018. doi:10.1002/hep.29913. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Liu H.F., Wang M., Wang Q., et al. Multiparametric MRI-based intratumoral and peritumoral radiomics for predicting the pathological differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Insig. Imag. 2024;15(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s13244-024-01623-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y.J., Cho S.G., Lee K.Y., Kim J.M., Lee J.W. Association between relative liver enhancement on gadoxetic acid enhanced magnetic resonance images and histologic grade of hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(30):e7580. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Y., Si Z., Chun C., et al. Multiphase MRI -based radiomics for predicting histological grade of hepatocellular carcinoma. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2024:jmri.29289. doi: 10.1002/jmri.29289. Published online February 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu C., Shiradkar R., Liu Z. Biomedical engineering department, case western reserve university, Cleveland 44106, OH, USA, department of radiology, Guangzhou first people's hospital, school of medicine, South China university of technology, Guangzhou 510080, China. Integrating pathomics with radiomics and genomics for cancer prognosis: a brief review. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2021;33(5):563–573. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2021.05.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao L., Liu Z., Feng L., et al. Multiparametric MRI and whole slide image-based pretreatment prediction of pathological response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: a multicenter radiopathomic study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020;27(11):4296–4306. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08659-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen D., Fu M., Chi L., et al. Prognostic and predictive value of a pathomics signature in gastric cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):6903. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34703-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang J., Zhang W., Yang J., et al. Deep learning supported discovery of biomarkers for clinical prognosis of liver cancer. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023;5(4):408–420. doi: 10.1038/s42256-023-00635-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M., Zhang B., Topatana W., et al. Classification and mutation prediction based on histopathology H&E images in liver cancer using deep learning. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2020;4:14. doi: 10.1038/s41698-020-0120-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stirling D.R., Swain-Bowden M.J., Lucas A.M., Carpenter A.E., Cimini B.A., Goodman A. CellProfiler 4: improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinform. 2021;22(1):433. doi: 10.1186/s12859-021-04344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter A.E., Jones T.R., Lamprecht M.R., et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome. Biol. 2006;7(10):R100. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajkomar A., Dean J., Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380(14):1347–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1814259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park H.J., Park B., Lee S.S. Radiomics and deep learning: hepatic applications. Kor. J. Radiol. 2020;21(4):387–401. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2019.0752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng B.H., Liu L.Z., Zhang Z.Z., et al. Radiomics score: a potential prognostic imaging feature for postoperative survival of solitary HCC patients. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1148. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z., Chen J., Jiang H., et al. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI radiomics signature: prediction of clinical outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020;8(14) doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3041. 870-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X.H., Long L.H., Cui Y., et al. MRI-based radiomics model for preoperative prediction of 5-year survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2020;122(7):978–985. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0706-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Do R.K.G., Rusinek H., Taouli B. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging of the liver: current status and future directions. doi:10.1016/j.mric.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Jiang W., Wang H., Dong X., et al. Pathomics signature for prognosis and chemotherapy benefits in stage III colon cancer. JAMA Surg. 2024 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.8015. Published online February 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi J.Y., Wang X., Ding G.Y., et al. Exploring prognostic indicators in the pathological images of hepatocellular carcinoma based on deep learning. Gut. 2021;70(5):951–961. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng L., Liu Z., Li C., et al. Development and validation of a radiopathomics model to predict pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Digital Heal. 2022;4(1):e8–e17. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J., Wu Q., Yin W., et al. Development and validation of a radiopathomic model for predicting pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):431. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-10817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu N., Guo X., Ouyang Z., et al. Multiparametric MRI-based radiomics combined with pathomics features for prediction of the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Heliyon. 2024;10(2):e24371. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L., Wang L., Sun J., et al. N6-methyladenosine related gene expression signatures for predicting the overall survival and immune responses of patients with colorectal cancer. Front. Genet. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.885930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo J., Zhu W.C., Chen Q.X., Yang C.F., Huang B.J., Zhang S.J. A prognostic model based on DNA methylation-related gene expression for predicting overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2024;13 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1171932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S., Shin J., Kim D.Y., Choi G.H., Kim M.J., Choi J.Y. Radiomics on gadoxetic acid–enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for prediction of postoperative early and late recurrence of single hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25(13):3847–3855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.