Abstract

Objective

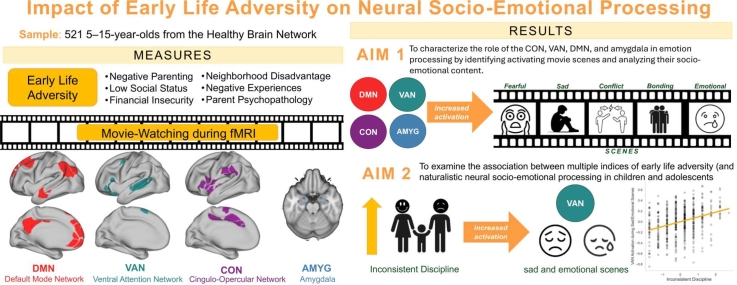

Early life adversity (ELA) has shown to have negative impacts on mental health. One possible mechanism is through alterations in neural emotion processing. We sought to characterize how multiple indices of ELA were related to naturalistic neural socio-emotional processing.

Method

In 521 5–15-year-old participants from the Healthy Brain Network Biobank, we identified scenes that elicited activation of the Default Mode Network (DMN), Ventral Attention Network (VAN), Cingulo-Opercular Network (CON) and amygdala, all of which are networks shown to be associated with ELA. We used linear regression to examine associations between activation and ELA: negative parenting, social status, financial insecurity, neighborhood disadvantage, negative experiences, and parent psychopathology.

Results

We found DMN, VAN, CON and amygdala activation during sad/emotional, bonding, action, conflict, sad, or fearful scenes. Greater inconsistent discipline was associated with greater VAN activation during sad or emotional scenes.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that the DMN, VAN, CON networks and the amygdala support socio-emotional processing consistent with prior literature. Individuals who experienced inconsistent discipline may have greater sensitivity to parent–child separation signals. Since no other ELA–activation associations were found, it is possible that unpredictability may be more strongly associated with complex neural emotion processing than socio-economic status or negative life events.

Key words: Adversity, Emotion processing, Naturalistic fMRI, Adolescence

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

The Default Mode, Ventral Attention Cingulo-Opercular networks, and amygdala play roles in naturalistic emotion processing.

-

•

Increased inconsistent discipline is linked to heightened Ventral Attention Network activation during sad/emotional scenes.

-

•

Findings suggest children in unpredictable caregiving environments may have altered socio-emotional processing.

1. Introduction

Early life adversity (ELA) affects an estimated 47 % of US children (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2013) and has been shown to negatively impact mental health, with about 45 % of individuals who experienced childhood adversity later receiving a psychiatric diagnosis (Green et al., 2010). One potential mechanism through which ELA may influence outcomes is via alterations in neural emotion processing (Gibb et al., 2009, Pollak et al., 2000), likely affecting interpersonal relationships. Indeed, the brain networks that underlie emotion processing (Camacho et al., 2023b, Somerville et al., 2011) are also implicated in mental health (Kaiser et al., 2015, Miller, 2015, Sylvester et al., 2013) and have been found to be altered in individuals with ELA (Chahal et al., 2022, Tottenham, 2014). Further, individuals often face person-specific ELA co-occurrence, where multiple types of adversity are experienced across the lifespan (Adler and Newman, 2002, Evans and Kim, 2013, McLoyd, 1998, Morello-Frosch and Shenassa, 2006). Few studies are powered to examine multiple dimensions of ELA in the same sample, however, making it difficult to parse how specific kinds of ELA may influence neural emotion processing and subsequent child development. Characterizing how myriad ELA types influence real-world neural emotion processing is therefore critical to identifying long-term mental health risks.

Understanding the impacts of early life adversity (ELA) on the brain requires disentangling the influence of varied adversities such as socioeconomic disadvantage, cumulative stress, parental influences, and specific adverse events (Smith and Pollak, 2021). Each of these types of ELA can influence neural emotion processing in unique ways such as through alterations in sensory inputs, nutrition, cognitive stimulation, and socialization (Hostinar and Gunnar, 2013, McLaughlin and Sheridan, 2016). Specifically, repeated exposure to threat (negative experiences or abuse) is theorized to promote hypervigilance (McLaughlin and Lambert, 2017) which in turn can result in a threat attentional or interpretation bias (McLaughlin et al., 2015, Pollak and Sinha, 2002). Alternatively, inconsistent parenting, characterized by varying responses to a child's needs or inconsistent rules and expectations, is associated with unpredictable sensory and social signals. This unpredictability can disrupt a child's ability to interpret stable emotional responses from caregivers and consistent feedback on their behaviors, potentially stunting their emotional development (Bernier et al., 2010, Eisenberg et al., 1998). It is also not uncommon for the experience of a specific adverse event to be associated with multiple other adversity experiences. For instance, the experience of low socioeconomic status can be related to exposure to neighborhood disadvantage (Santiago et al., 2011), limited access to healthcare (Adler and Newman, 2002), and higher levels of family stress (Adler and Newman, 2002, Evans and Kim, 2013, Morello-Frosch and Shenassa, 2006). Moreover, low socioeconomic status affects financial security and social status (Adler and Newman, 2002, McLoyd, 1998), which can have bidirectional influence on parental mental health and child emotional development (Goodman and Gotlib, 1999). Research has shown the interconnectedness and cascading effects of various adverse experiences (Hughes et al., 2017, Iverson, 2021, Masten and Cicchetti, 2010). Thus, a comprehensive examination of how different types of early life adversity affect neural emotion processing within the same sample is necessary to clarify these complex associations.

Individual differences in neural systems that underlie naturalistic emotion processing have also been found to be associated with ELA, specifically the Ventral Attention Network (VAN), Default Mode Network (DMN), Cingulo-Opercular Network (CON) and amygdala. The DMN is implicated in social processing and affective experience (Buckner et al., 2008, Raichle and Snyder, 2007), while the VAN, CON, and amygdala are associated with detecting and attending to emotional cues (salience processing) as well as maintaining arousal states (Menon and Uddin, 2010, Phelps and LeDoux, 2005, Seeley et al., 2007). Animal and human work has shown that the amygdala and anterior portion of the DMN are highly susceptible to stress effects (Chen and Baram, 2016, Kim and Diamond, 2002, Malter Cohen et al., 2013). However, it is unclear how ELA is associated with the functioning of these systems during naturalistic emotion processing. Task-based neuroimaging studies have provided insights into how ELA affects neural responses to specific emotional stimuli. Specifically, maltreated children show greater amygdala activation to negative facial stimuli than non-maltreated children (McCrory et al., 2022, McLaughlin et al., 2019). Children exposed to adversity in the form of deprivation (poverty, unstable environments, limited resources) were shown to have amygdala activation to fearful faces (McLaughlin et al., 2019). Some studies show heightened CON activation to fearful faces (Cisler et al., 2013, Hart et al., 2018), whereas others find no differences in DMN activation between threatening and neutral stimuli (McLaughlin et al., 2020, Weissman et al., 2020). In contrast, resting state studies have revealed how ELA impacts intrinsic functional connectivity in these neural networks. Individuals who experience environmental adversities such as poverty have been shown to have reduced DMN connectivity (Rebello et al., 2018). Additionally, children who experienced familial and environmental deprivation had increased stable connectivity in the VAN and CON relative to children with less deprivation experience (Chahal et al., 2022). These task-based and resting state findings suggest that ELA may influence neural responses during naturalistic emotion processing, potentially leading to heightened activation in the DMN, CON, VAN, and amygdala during emotionally salient scenes, particularly those related to specific adverse experiences. The current literature lacks sufficient evidence to establish a clear hypothesis about how activation patterns might vary according to different types of adversity experienced. As a result, while heightened activation in response to emotionally salient content is anticipated, determining the specific nature of these activation patterns in relation to various types of ELA is challenging due to the mixed and evolving nature of the evidence.

It is difficult to link this prior literature that examined emotion processing using static and context-poor stimuli to real-world functioning because such stimuli lack both context for the emotion cues (cause and aftermath) and complex presentation, such as competing sensory inputs (Crick and Dodge, 1994, Lemerise and Arsenio, 2000). Indeed, behavioral research shows that children learn to reason about others’ emotions based on face cues in context of cause and effect (Hoemann et al., 2019, Ruba and Pollak, 2020, Widen and Russell, 2010, Widen and Russell, 2008). Further, the CON, VAN, and DMN have diverse functions that may have myriad influences on naturalistic emotion processing (Bernard et al., 2020, Corbetta et al., 2008, Coste and Kleinschmidt, 2016, Menon, 2023, Newbold et al., 2021, Smallwood et al., 2021, Vaden et al., 2013) including sensory integration (Raichle and Snyder, 2007, Smallwood et al., 2021), attention (Corbetta and Shulman, 2002), and action planning (Dosenbach et al., 2008) that are not captured by examining emotion-specific activation. Recent work, also using the Healthy Brain Network sample, has shown that movies are a viable alternative to static images to more closely examine naturalistic neural emotion processing (Camacho et al., 2023b, Camacho et al., 2019). Only one study to date has examined neural emotion processing in children with ELA with the use of a Pixar short movie about a baby sandpiper who overcomes its fear of the ocean with the encouragement of its mother (Park et al., 2022). The study found that higher SES was linked to greater anterior DMN activation during parent-child interactions, and negative parenting behaviors were associated with reduced amygdala activation during positive emotional events (Park et al., 2022). Characterizing what content elicits increased VAN, DMN, and CON activation during complex emotion processing could provide deeper insights into the links between ELA and emotion functioning.

In this study, we leveraged a large cross-sectional sample of youth imaged during movie-watching and with measures of the following ELA types: negative parenting practices, parent psychopathology, financial insecurity, social status, neighborhood disadvantage and negative life events. Firstly, we characterized the role of the CON, VAN, DMN and amygdala in emotion processing by identifying movie scenes that induce increased activation in these systems. Secondly, we qualitatively and quantitatively characterize the identified scenes’ content, grouping the identified scenes based on the socio-emotional processing needed to follow the movie. Finally, we characterized associations between activation to the identified scenes and multiple indices of ELA. We predict that (1) there will be heightened activation of each the DMN, CON, VAN, and amygdala during scenes displaying highly salient emotional content, (2) that specific adverse experiences such as negative parenting and life events are associated with activation to scenes depicting themes related to caregiver-child relationships, bonding, and separation.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Data were drawn from the Healthy Brain Network Biobank (HBN) (Alexander et al., 2017), a large, multi-site study of children and adolescents aged 5–21 who completed neuroimaging, cognitive and clinical assessments at one of four sites in the New York area. The sample is enriched for males and children with psychopathology. We excluded data from two out of four sites as they contributed only 12 % of the available datasets. Furthermore, considering that 92 % of the data came from children below the age of sixteen and existing research indicates that emotion processing skills tend to stabilize by mid-adolescence (Camacho et al., 2023b, Camacho et al., 2023a), we focused our analyses solely on children aged between 5 and 15 years. Out of the initial dataset comprising 2053 participants, 1012 were excluded due to incomplete data or functional and/or structural artifacts. Additionally, 83 participants did not watch the 10-minute clip from Despicable Me, 338 were excluded due to high motion according to rigorous data processing criteria, and 99 did not have complete ELA data. This left 620 participants for the fMRI analysis and 521 for ELA analysis. All participants provided informed consent or assent. Full study details are listed on the HBN project website.1 Sample information is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics. Puberty scores were obtained using the Peterson Puberty Scale (Peterson et al., 2012). Consensus lifetime diagnoses provided by HBN were determined by trained clinicians based on a combination of the K-SADS interview (Kaufman et al., 1997), clinician impression of the child, and reviewing questionnaire responses. Since children can have more than one diagnosis, the cumulative psychopathology diagnoses may exceed 100 %.

|

Sample Size (N = 521) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M | SD | |

| 10.47 | 2.79 | ||

| Sex | % | ||

| Male | 60.38 | ||

| Female | 39.62 | ||

| Race | % | ||

| White/Caucasian | 55.38 | ||

| Black/African American | 11.94 | ||

| Hispanic | 8.41 | ||

| Asian | 2.54 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.20 | ||

| Two or more races | 18.98 | ||

| Other Races | 1.76 | ||

| Unknown | 0.78 | ||

| Ethnicity | % | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 69.38 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 23.84 | ||

| Decline to specify | 5.62 | ||

| Unknown | 1.16 | ||

| Income | M | Median | SD |

| $90,000 to $99,999 | $100,000 to $149,999 | $33,470 | |

| Puberty Score | M | Median | SD |

| 9.66 | 8.00 | 4.22 | |

| Psychopathology | % diagnosed | ||

| Major depressive disorder | 14.81 | ||

| Anxiety disorder | 53.28 | ||

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 64.96 | ||

| Autism spectrum disorder | 17.38 | ||

| Intellectual developmental disorder | 2.56 | ||

| Learning disorder | 32.76 | ||

| Communication disorder | 14.53 | ||

| Motor disorder | 11.40 | ||

| Substance use disorder | 0.85 | ||

| Disruptive behavior disorder | 20.51 | ||

| Trauma and stressor-related disorder | 6.27 | ||

| Schizophrenia | 0.28 | ||

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 8.55 | ||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.28 | ||

| Eating disorders | 1.14 | ||

| Missing diagnosis | 34.00 | ||

2.2. Early life adversity indices

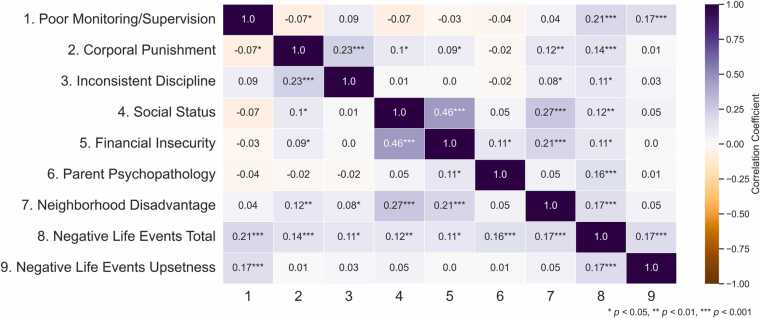

The HBN sample was not recruited with a specific ELA criterion for inclusion. To capture the rich diversity of ELA experiences in this sample, all available indices of ELA were considered for analysis (Table 2, Fig. 1 and S2). These indices map onto different dimensions of adversity: negative life events, corporal punishment, neighborhood disadvantage, and parent psychopathology relate to threat; social status, financial insecurity, and again neighborhood disadvantage relate to deprivation; and inconsistent discipline and poor monitoring/supervision correspond to unpredictability. This comprehensive approach allows for the examination of differential effects of various ELA types on neural emotion processing. Although both the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire and the Negative Life Events Scale included parent and youth reports, the analysis was limited to parent reports due to the low youth response rate and the absence of youth data for other indices. ELA indices were only moderately correlated in this sample (Fig. 1). For more detailed information on the ELA statistics and factor structure, please refer to the supplementary materials (Figure S3 and Table S2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of nine ELA indices from the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ), Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (Barratt), Family History – Research Diagnostic Criteria (PreInt_RDC), Financial Security Questionnaire (FSQ), Negative Life Events Scale (NLES) and PhenX Neighborhood Safety (PhenX).

|

fMRI sample (N = 620) |

fMRI with ELA Sample (N = 521) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (Range) | Mean (SD) | Median (Range) |

| Inconsistent Discipline (APQ) | 2.17 (0.67) | 2.33 (1.0–4.3) | 2.17 (0.67) | 2.33 (1.0–4.0) |

| Poor Monitoring/Supervision (APQ) | 1.69 (0.57) | 1.67 (1.0–3.7) | 1.68 (0.56) | 1.67 (1.0–3.7) |

| Social Status (Barratt) | 16.14 (13.96) | 13.00 (0.0–66.0) | 15.99 (14.01) | 13.00 (0.0–66.0) |

| Financial Insecurity (FSQ) | 0.32 (0.22) | 0.27 (0.0–1.0 | 0.31 (0.21) | 0.27 (0.0–1.0) |

| Neighborhood Disadvantage (PhenX) | 1.99 (0.93) | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 1.97 (0.91) | 2 (1.0–5.0) |

| Negative Life Events Total (NLES) | 6.57 (3.15) | 6.0 (0.0–16.0) | 6.63 (3.14) | 6 (0.0–16.0) |

| N | % | N | % | |

| Corporal Punishment (APQ) | 188 | 34 | 172 | 33 |

| Parent Psychopathology (PreInt_RDC) | 223 | 40 | 208 | 40 |

Fig. 1.

Correlation matrix displaying the Spearman correlation coefficients (r values) among seven ELA indices.

2.2.1. Negative parenting practices

Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Shelton et al., 1996) is a 42-item questionnaire measuring five domains (positive involvement, supervision/monitoring, use of positive discipline, inconsistency in the use of such discipline, and use of corporal punishment) of parents relevant to the treatment and etiology of children externalizing behaviors. Aggregates of the items under the domains inconsistent discipline (APQ_P_ID), and poor supervision/monitoring (APQ_P_PM), were included in analysis. Since a portion of participants were missing one or more items (N=37), only those with responses for more than 50 % of the items in each scale were included in further analysis, and an average score was computed for each. Due to the large number (66 % of sample) of children with no corporal punishment (APQ_P_CP), a dummy variable was created: 1 indicates any experience of corporal punishment, while 0 indicates none. The scores for poor supervision/monitoring were power-transformed to correct for skewness and approximate a normal distribution for further analysis. The inconsistent discipline scores were standardized (z-scored), and the dummy-coded corporal punishment scores were mean-centered.

2.2.2. Social status

Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (Barratt, 2012) is derived from the research of Hollingshead (Hollingshead, 1957, Hollingshead, 1975), who developed an assessment of Social Status using factors such as marital status, employment status, educational achievement, and occupational prestige. The measure is used as a proxy for socio-economic status. The total score (Barratt_Total) was reversed, with higher scores indicating lower levels of social status, and was power-transformed.

2.2.3. Parent psychopathology

The Family History – Research Diagnostic Criteria (Uher et al., 2014) evaluates the psychiatric history of families by interviewing parents of participants regarding their own and their relatives' experiences with psychiatric disorders. The parent psychopathology variable was created using dummy coding, where a value of 1 indicates that either parent (fdx and mdx) had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. To facilitate interpretation of regression coefficients the dummy coded variable was mean-centered.

2.2.4. Financial insecurity

The Financial Security Questionnaire was developed by the HBN team at the Child Mind Institute and evaluates household income, public assistance received, and health insurance details. The income-to-needs ratio was calculated by dividing the midpoint of the endorsed income bin by the number of people in the household. The income-to-needs ratio was reverse scored so that higher scores now indicate higher financial strain or difficulty in meeting basic living standards. Government assistance eligibility was dummy-coded such that a value of 1 indicates the family receives financial assistance and 0 indicates no external government assistance. Lastly, employment status was dummy-coded to indicate whether either parent was employed or not. A value of 1 indicates that neither parent was employed, while a value of 0 indicates that at least one parent was employed. An aggregate of financial insecurity was created by averaging incomes to needs, government assistance eligibility, and current parent employment status items. The final average was power-transformed.

2.2.5. Neighborhood disadvantage

PhenX Neighborhood Safety (Mujahid et al., 2007) is a three item measure of respondents' feelings towards neighborhood level safety, violence and crime on a 5 point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Items were averaged to measure neighborhood safety, with higher scores indicating lower perceived safety, and power transformed to correct skewness and approximate a normal distribution.

2.2.6. Negative life events

Negative Life Events Scale (Sandler et al., 1991) includes items on family, community, and school-based stressors that children may be exposed to. Parents are asked to rate whether the event occurred, whether the child was aware, and the child's level of resulting stress or upsetness. For analysis, both the cumulative number of events (NLES_P_TotalEvents) and the average level of resulting stress or upsetness (NLES_P_Upset_Avg) were included, the former indexing cumulative stress (Felitti et al., 1998, Pollak and Smith, 2021) and the latter the subjective impact of stressors on that child. Both variables were standardized.

2.3. Neural emotion processing indices

2.3.1. Quantifying video features

During the fMRI scan, participants viewed a 10-minute segment of the film "Despicable Me." The segment contained a mixture of positive and negative emotional cues presented within the context of a parent-child relationship. A summary of the 10-minute video segment can be found in the supplement. Emotion-specific and emotion non-specific content was quantified using the EmoCodes video coding system (Camacho et al., 2022). Two raters independently coded the video for various elements, including the presence of faces, bodies and written and spoken words, in addition to the specific emotional expressions of characters. Agreement between raters ranged from 0.65 to 1.00, and their scores were averaged for analysis. These codes were combined to create an overall emotional intensity measure per frame. Specific emotions such as anger, fear, excitement, sadness, and happiness were coded for each character, with the face, body, and voice as separate mediums of expression. Finally, the EmoCodes python library was used to automatically extract low-level video features including brightness, loudness, motion, sharpness, vibrance, and portion of the screen with highly salient content. There were no strong associations among the resulting emotion, emotion non-specific, and low-level content (rs< |0.3|) or between video content and subject motion during fMRI (see supplemental materials for (Camacho et al., 2023b)). Full analysis of these video features are reported extensively in prior work (Camacho et al., 2023b, Camacho et al., 2023a). Example images and their associated intensities from the Despicable Me clip can be found in the supplement.

2.3.2. fMRI preprocessing

MRI data from two different locations, the CitiGroup Cornell Brain Imaging Center (CBIC) and the Rutgers University Brain Imaging Center (RUBIC), were examined for analysis. CBIC collected data using a Siemens 3 T Prisma scanner, while RUBIC used a Siemens 3 T Trio scanner, both employing a 64-channel head coil. The MRI data comprised T1-weighted and T2-weighted anatomy scans, along with BOLD fMRI. Functional MRI data were captured using simultaneous multiband echo planar imaging sequences with an 800 ms TR, while children watched two video clips: a 10-minute segment from the movie Despicable Me and a 3-minute-20-second short called The Present. The Present was not analyzed in this study due to its focus on the relationship between a boy and dog, whereas Despicable Me primarily depicted human–human relationships. For datasets containing multiple T1- or T2-weighted images, the image with minimal artifact/motion was selected for processing. Detailed sequence parameters can be found on the HBN project website.

Data preprocessing utilized the Human Connectome Project Minimal Processing Pipeline (Glasser et al., 2013), augmented with custom Python scripts (v3.8) leveraging numpy (Harris et al., 2020), scipy (Virtanen et al., 2020), nibabel, and pandas libraries (available at https://github.com/catcamacho/hbn_analysis/tree/main/1_activation). Initially, structural T1 and T2-weighted data underwent alignment and correction for gradient and bias field (Andersson and Sotiropoulos, 2016) distortions. Subsequently, freesurfer’s recon-all pipeline v7 (Fischl, 2012) was used to for segmentation and surface generation. Surfaces were aligned to template space via multimodal surface matching (Robinson et al., 2018) and resampled to 32,000 vertices. Surface-level inspection was conducted, and datasets with errors mainly due to motion artifacts in T1 or T2-weighted data or misalignment of surfaces with white matter cortical boundary were excluded (N=336). Manual surface correction was not performed, as the sample size was sufficiently large to accommodate the removal of participants without compromising the analysis. Functional data underwent correction for gradient and bias field (Andersson and Sotiropoulos, 2016) distortions, slice-time correction, rigid realignment, global mean normalization, and volume space masking. Conversion into surface space involved aligning the cortical ribbon to the volume space fMRI data, followed by rescaling the BOLD signal to standard units before applying nuisance regression and bandpass filtering (0.008–0.1 Hz). Nuisance regressors included global signal, six motion parameters, framewise displacement, and temporal censoring of volumes with a framewise displacement of 0.9 mm or more (Siegel et al., 2017, Siegel et al., 2014). Each functional run was deemed usable if 80 % of the sequence had framewise displacement below 0.9 mm. Lastly, the Gordon cortical (Gordon et al., 2016) and Seitzman subcortical and cerebellum atlases (Seitzman et al., 2020) were applied, resulting in denoised time series for 333 cortical regions, 34 subcortical regions, and 27 cerebellar regions, totaling 394 parcels. The Gordon atlas DMN, VAN, and CON parcels and Seitzman Amygdala regions of interest (ROI) were used for further analysis.

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Activation-based scene identification

To identify scenes from the movie clip Despicable Me that had increased levels of activation for each network or the amygdala, a robust method was employed by splitting the sample based on the two sample sites to create a discovery (CBIC; N = 282) and replication (RUBIC; N = 338) sample to ensure the reliability of the results. Using the discovery sample, the fMRI time series was first converted into a percent signal change and then averaged within the networks/ROIs (DMN, VAN, CON, and amygdala), resulting in 4 time series per participant. One-sample t-tests were performed separately for each region/network at each timepoint for each the Discovery and Replication samples to detect scenes with significantly elevated activation. Identified scenes (n = 39) were considered significant if 1) they lasted at least 3.2 seconds (4 TRs) were significant at p<0.05 after Bonferroni-style FDR correction; and 3) were detected in both the discovery and replication samples. Segments of the video corresponding to the each identified scene were extracted by time-shifting the movie file timestamps by 4 seconds to account for the delay in the hemodynamic response.

2.4.2. Qualitative grouping of scenes

To group the extracted scenes by their social and emotional content, each scene's overall theme was qualitatively examined and compared within the scenes identified for that region/network. Scenes depicting similar social information or emotional content were grouped together. The authors (EJF and MCC) grouped the 39 identified scenes across the regions/networks based on the narrative content of the scenes, resulting in 3 DMN, 4 VAN, 4 CON, and 3 Amygdala scene groups, for a total of 14 scene groups across networks (Table 3). The video feature codes were next examined within each scene group. An ANOVA was conducted to assess differences in video features among scenes within each scene group. Activation from scene groups were then averaged within participants to reduce the number of comparisons made in the ELA analysis.

Table 3.

Description of activated scenes within each network and their scene groupings.

| Default Mode Network | |

|---|---|

| Scene Grouping | Description of Scenes |

| Group 1: Sad/Emotional | Scene 1: Gru goes to the door, where Miss Hattie informs him, she's there for the girls |

| Scene 2: Minions cleaning up the girls’ paintings on the wall, girls standing in the boxes of shame | |

| Scene 4: Gru proclaiming, "I am the greatest criminal mind," before getting into his spaceship | |

| Scene 5: Miss Hattie at the door, Dr. Nefario clearing his throat behind Gru. Gru tells Miss Hattie he’ll get the girls ready and walks them to the car | |

| Group 2: Bonding | Scene 6: Gru reading a book, dismissing it as garbage, the girls asking him to keep reading. |

| Scene 7: Gru reading the book, the girls starting to yawn and fall asleep. | |

| Scene 8: Gru reading the book to the girls before bed | |

| Scene 9: Gru declines reading a book to the girls, but they insist | |

| Scene 10: The girls say they’ll only bother Gru if he doesn’t read them a bedtime story, Gru complies | |

| Scene 11: Girls asleep, Gru gets emotional about content, Gru says goodnight and wakes them up. | |

| Group 3: Action | Scene 3: Gru’s spaceship falling, blasting past a floating minion, as Gru detaches from the spaceship. |

| Ventral Attention Network | |

|---|---|

| Scene Grouping | Description of Scenes |

| Group 1: Sad/Emotional | Scene 3: Girls get into the car with Miss Hattie, pleading for Gru to keep them. |

| Scene 11: Gru sadly watches as the girls drive away. Dr. Nefario insists it's for Gru's own good. | |

| Scene 15: Minions clean up paintings. Girls in boxes of shame at the foster home. | |

| Group 2: Bonding | Scene 2: Gru reads a book, dismissing it as garbage. Girls ask him to continue. |

| Scene 4: Girls asleep, Gru gets emotional about content, Gru says goodnight and wakes them up. | |

| Scene 5: Gru declines reading a book to the girls, but they insist. | |

| Scene 6: Gru enters the room to find hyperactive girls, reminding them it's time to sleep. | |

| Scene 9: Gru enjoys a tea party with the girls before excusing himself as the doorbell rings. | |

| Scene 10: Gru reading the book, the girls starting to yawn and fall asleep. | |

| Group 3: Fear/Pain | Scene 7: Gru finds a doll in bed and gets scared, switching focus to his minions in the lab. |

| Scene 8: Vector gets zapped by Gru while attached to a spaceship. | |

| Scene 12: Vector inflates a parachute. Gru's spaceship falls past a minion. | |

| Group 4: Conflict | Scene 1: Minion hands Gru the recital ticket Gru proclaims "I am the greatest criminal mind.” |

| Scene 13: Miss Hattie inquires about returning the girls and hits Gru with a Spanish dictionary, as Dr. Nefario clears his throat. | |

| Scene 14: Dr. Nefario questions Gru about postponing the heist, suspecting it’s related to the girls’ recital, as Gru defends himself. | |

| Scene 16: Dr. Nefario warns Gru about the girls being a distraction and begins to threaten their involvement. | |

| Cingulo-Opercular Network | |

|---|---|

| Scene Grouping | Description of Scenes |

| Group 1: Sad/Emotional | Scene 3: Gru walks by while the minions clean up the paintings on the wall. |

| Scene 5: Gru watches as girls drive away. Dr. Nefario says it's for Gru's own good, Gru sad, minions crying in the window. | |

| Group 2: Bonding | Scene 2: Girls asleep, Gru gets emotional about content, Gru says goodnight and wakes them up. |

| Scene 4: Gru enjoys a tea party with the girls before excusing himself as the doorbell rings. | |

| Scene 7: Gru reading the book, the girls starting to yawn and fall asleep. | |

| Scene 9: Agnes explains the finger puppets in the book, Gru tries it. | |

| Group 3: Fear/Pain | Scene 6: Vector falling, inflates parachute and flies into electric pole, Gru's spaceship falling. |

| Scene 8: Miss Hattie hits Gru with a Spanish dictionary and says she didn't like what he says. | |

| Group 4: Conflict | Scene 1: Gru says he's the greatest criminal mind and doesn't go to dance recitals. |

| Amygdala | |

|---|---|

| Scene Grouping | Description of Scenes |

| Group 1: Conflict | Scene 3: Gru throws the recital ticket, and the minion catches it. |

| Group 2: Bonding | Scene 2: Edith instructs Gru how to use the book finger puppets. Gru responds sarcastically |

| Group 3: Fear/Pain | Scene 1: Vector inflates a parachute, flies into an electric pole and gets electrocuted. Gru’s spaceship falls past a minion |

2.4.3. Identify activation associated with ELA

To test associations between the network activation groups and indices of ELA, we conducted a series of general linear models (GLMs). First, we tested if ELA explained variance in our activation data above and beyond covariates by conducting 3 GLMs per activation measure, testing if the models with ELA variables provide a better fit to the data than the covariates-only model. Model 1: Age, sex and average framewise displacement were entered as GLM independent variables and the neural activation for each scene group (2.4.2) was entered as dependent variables, for a total of 14 models. Model 2: All nine ELA indices were added to the design from Model 1 as GLM independent variables. Model 3: Age*ELA interaction terms were added to the design from Model 2. We conducted model-level analysis of variance (ANOVA) between the models pairwise to test if adding ELA or ELA*Age terms improved model fit. Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction was applied at the hypothesis level to account for multiple comparisons in testing the association between each ELA index and network activation. Therefore, for each ELA index, we adjusted for comparisons across 3 or 4 scene groups based on the brain network scene grouping determined (2.4.2).

2.4.4. Follow up analysis

Due to the high incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the HBN sample (∼60 %) and the previously found associations between ADHD and brain function (Cortese et al., 2012, Konrad and Eickhoff, 2010), we repeated analyses with ADHD symptoms, as measured by the Strengths and Weaknesses of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Normal Behavior questionnaire (Swanson et al., 2012), included as an additional covariate. Additionally, given the modest correlations between some adversity indices (Fig. 1), we analyzed an additional model that included an aggregate measure of socioeconomic factors (social status, income, and neighborhood disadvantage). Detailed findings on follow up analyses can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S6).

3. Results

3.1. Activation-based scene identification

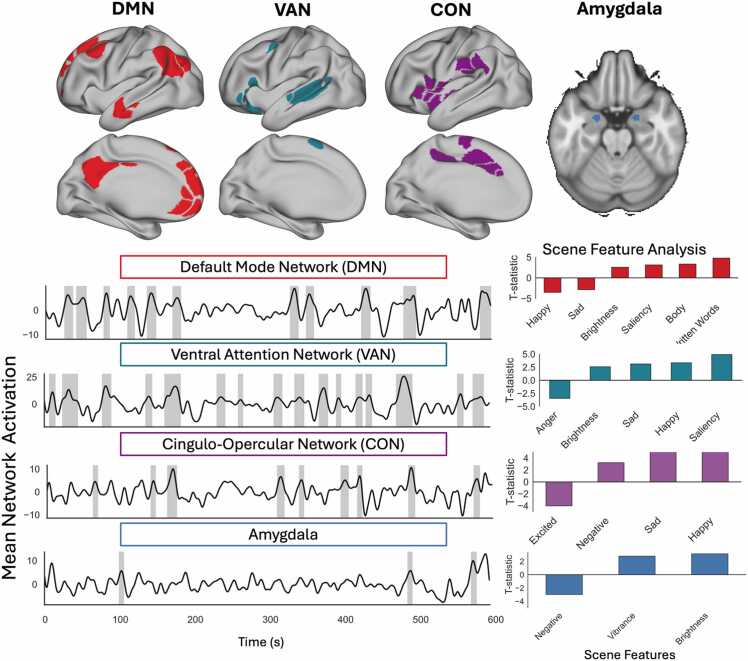

The activation-based scene identification analysis revealed significant increases in activation within eleven scenes for the DMN, sixteen scenes for the VAN, nine scenes for the CON and three scenes for the Amygdala (Fig. 2). DMN scenes were characterized by increased brightness, greater proportion of the scene containing highly salient visual features and were more likely to contain characters and written words, while displaying less overtly happy or sad emotional content. VAN scenes were on average brighter and contained more salient visual features, had greater happy and sad emotional content, and less anger. CON scenes were on average more negative, sad, and happy and had less expression of excited emotion. Lastly, Amygdala scenes were on average more negative, vibrant, and brighter than the rest of the video. Figure S1 in the supplement shows examples of varying video features from the Despicable Me clip.

Fig. 2.

(a) Network based scene identification for Despicable Me. Anatomical visual of each brain network or region (top). (b) Time series plot of each network with scenes of increased neural activation highlighted by grey bars. (bottom, left). T-statistics for video features that significantly differed between identified scenes and the rest of the movie clip (bottom, right).

3.2. Qualitative grouping of scenes

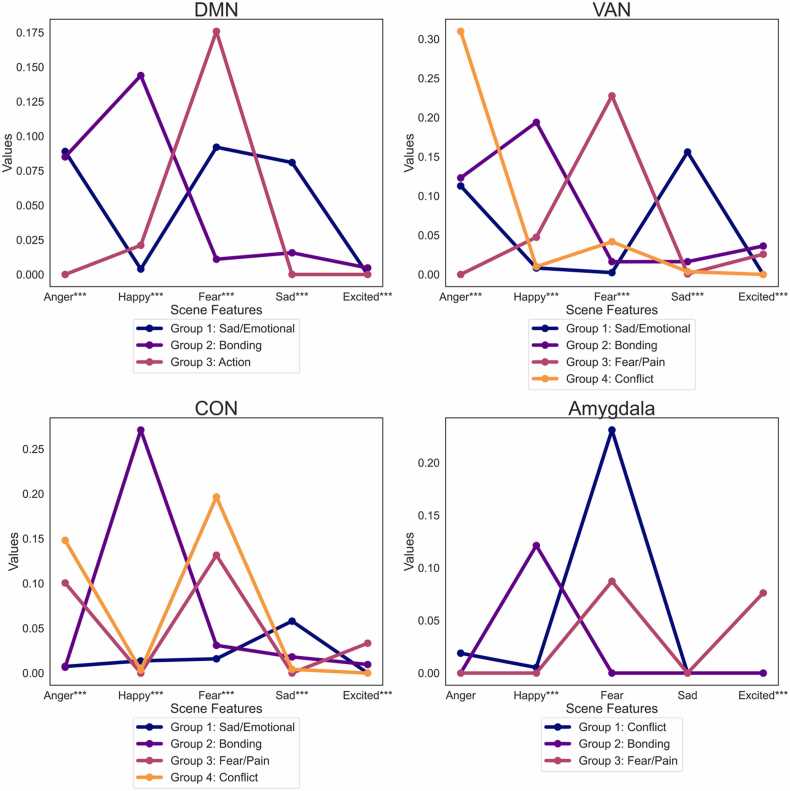

Qualitative grouping was conducted for identified scenes (Table 3). DMN: The DMN-identified scenes were of three groups: sad/emotional (group 1), depicting Gru after the girls were taken away; relationship bonding (group 2), showcased through bedtime reading with Gru; and action content (group 3), such as Gru's spaceship falling. VAN: The VAN scenes were of four groups: sad/emotional (group 1); relationship bonding with Gru and the girls (group 2); fear/pain (group 3), scenes where Vector gets hurt or Gru gets scared; and conflict (group 4), where Gru has adversarial interactions with the minions, Miss Hattie, or Dr. Nefario. CON: The CON activated scenes were categorized into four groups: sad/emotional (group 1); relationship bonding with Gru and the girls (group 2); fear/pain (group 3); and lastly, conflict (group 4). Amygdala: The amygdala activated scenes were categorized into three scene groups. conflict (group 1); relationship bonding with Gru and the girls (group 2); and fear/pain (group 3).

Post-hoc quantitative analysis (ANOVA) using EmoCodes corroborated these groupings (Fig. 3 and S4). For the DMN, high intensities of fear, sadness, and anger were observed in sad/emotional scenes, happiness in relationship bonding scenes, and fear in action content scenes. In the VAN, emotional themes were reflected: sadness in sad/emotional scenes, happiness in relationship bonding scenes, fear in fear/pain scenes, and anger in conflict scenes. In the CON, there was increased sadness in sad/emotional scenes, happiness in relationship bonding scenes, and both fear and anger in fear/pain and conflict scenes. Lastly in the Amygdala, scenes showed high fear during conflict scenes, happiness during bonding scenes and high fear/excitedness during fear/pain scenes.

Fig. 3.

: Emotional content within each scene groups per network: DMN (top, left), VAN (top, right), CON (bottom, left) and Amygdala (bottom, right). *** indicates scene features with significant intensity differences compared to others within the grouping.

Peak activation during those scene groups were averaged according to the grouping, resulting in a total of fourteen activation measures across the four networks/regions.

3.3. Activation associated with adversity

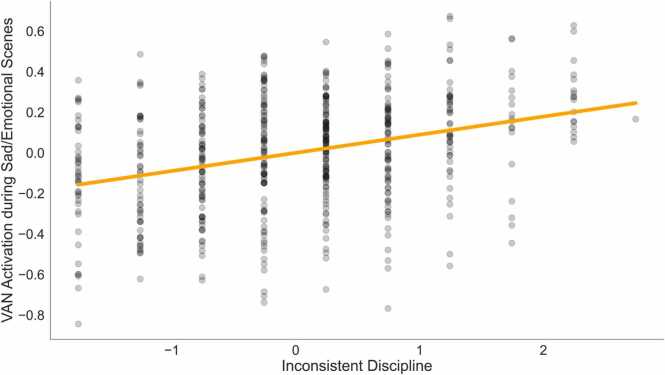

The ANOVA results revealed a significant difference in model fit between the covariate model (Model 1) and the ELA model (Model 2; F (9, 508) = 2.05, p = 0.028) for VAN activation during sad/emotional scenes. However, no significant difference was found between the ELA model and the age*ELA interaction model (Model 3) (F (9, 499) = 0.723, p = 0.663) (Table 4). Therefore, a GLM regression was conducted on Model 2 using ELA indices to predict activation in the VAN during Sad/Emotional scene and including age, sex and average framewise displacement as covariates. Greater inconsistent discipline was associated with increased VAN activation during sad/emotional scenes (β = 0.12, p = 0.006) (Fig. 4), which remained significant after covarying ADHD symptoms (Table S5).

Table 4.

Standardized coefficients and confidence of intervals for terms in the three models predicting variation in neural activation in the VAN during Sad/Emotional scenes.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | |||

| Age | 0.16 [0.08, 0.24] | 0.19 [0.09, 0.30] | 0.18 [0.07, 0.29] |

| Female | 0.08 [−0.09, 0.26] | 0.07 [−0.10, 0.24] | 0.07 [−0.10, 0.25] |

| MeanFD | −0.19 [−0.28, −0.11] | −0.19 [−0.27, −0.10] | −0.19 [−0.27, −0.10] |

| ELA Effects | |||

| Negative Life Events Total | 0.02 [−0.07, 0.11] | 0.03 [−0.06, 0.12] | |

| Negative Life Events Upsetness | 0.02 [−0.07, 0.10] | 0.02 [−0.06, 0.11] | |

| Social Status | −0.09 [−0.18, 0.00] | −0.09 [−0.18, 0.00] | |

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | −0.07 [−0.16, 0.02] | −0.07 [−0.16, 0.02] | |

| Financial Insecurity | 0.07 [−0.02, 0.16] | 0.07 [−0.01, 0.16] | |

| Poor Monitoring/Supervision | −0.06 [−0.16, 0.05] | −0.05 [−0.15, 0.06] | |

| Inconsistent Discipline | 0.12 [0.04, 0.21] | 0.12 [0.03, 0.20] | |

| Corporal Punishment | −0.08 [−0.17, 0.01] | −0.08 [−0.17, 0.01] | |

| Parent Psychopathology | 0.02 [−0.07, 0.10] | 0.02 [−0.07, 0.10] | |

| Age Interaction Effects | |||

| Negative Life Events Total: Age | −0.04 [−0.13, 0.05] | ||

| Negative Life Events Upsetness: Age | −0.04 [−0.13, 0.04] | ||

| Social Status: Age | −0.06 [−0.16, 0.03] | ||

| Neighborhood Disadvantage: Age | −0.04 [−0.13, 0.05] | ||

| Financial Insecurity: Age | 0.01 [−0.09, 0.10] | ||

| Poor Monitoring/Supervision: Age | −0.01 [−0.11, 0.08] | ||

| Inconsistent Discipline: Age | −0.02 [−0.10, 0.07] | ||

| Corporal Punishment: Age | 0.01 [−0.08, 0.10] | ||

| Parent Psychopathology: Age | 0.01 [−0.07, 0.10] | ||

| R^2 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

Note: Results significant at FDR-corrected p<0.05 are noted by *

Fig. 4.

: Relationship between Inconsistent Discipline (x-axis) and VAN Activation during Sad/Emotional Scenes (y-axis), controlling for age, sex, average framewise displacement, and other adversity indices from Model 2. Orange line represents model predictions, and black points represent actual data.

For all other 13 neural activation measures, Model 2 and 3 did not explain more variance in the activation data as compared to Model 1 (Tables S4 and S5).

4. Discussion

This study used a data-driven approach to investigate how ELA-implicated brain networks/regions support complex emotion processing and characterize the associations between this activation and nine ELA measures. The activation-based scene identification analysis revealed that the VAN, CON, DMN, and amygdala had increased activation primarily during scenes that were sad or fearful or featured pain, conflict, threat, or bonding. Increased VAN activation during sad/emotional scenes was associated with increased inconsistent discipline. No other ELA–activation associations were significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. Together, this suggests that inconsistent caregiver signals may influence complex emotion processing more so than other ELA. We used movie-watching to characterize how the VAN, CON, DMN, and amygdala are involved in naturalistic neural emotion processing. This approach is more ecologically valid as compared to highly controlled static stimuli such as an emotional faces task (Hariri et al., 2002) by capturing the rich social context in which emotion cues are typically presented (Kamps et al., 2022). Consistent with the hypothesized role of these networks and regions (Bush et al., 2000, Corbetta and Shulman, 2002, Etkin et al., 2011, Phan et al., 2002, Phelps and LeDoux, 2005), the VAN and CON had increased activation during highly salient and negative emotional content, while the DMN had great activation to social scenes in general, and the amygdala had greater activation to scenes that were brighter and more vibrant without an overall preference for social/emotional content. Qualitatively, the DMN, VAN, CON, and amygdala had increased activation during scenes with both sad and bonding content., the VAN, CON, and amygdala exhibited increased activation during fear and pain scenes. However, notable differences arose in other contexts: action scenes were associated with heightened activity in the DMN, while conflict scenes were linked exclusively to the VAN and CON. This pattern of neural activation is noteworthy because it indicates that specific brain networks are consistently engaged during certain emotional scenes, like sadness or bonding, while others become more active during fear or conflict scenes. The findings complement those of previous studies suggesting that the functional specialization of brain regions, particularly the DMN, plays a crucial role in individuals' capacity to understand and interpret social cues and emotions (Richardson, 2019). Overall, these findings suggest that these networks/regions are performing similar emotion processing functions under more naturalistic contexts as are found using more controlled tasks: the DMN supporting social/relational processing while the CON, VAN and amygdala are supporting lower and higher order stimulus-driven salience processing.

We found that greater inconsistent discipline was associated with greater VAN activation to sad or emotional scenes. This suggests that unpredictable caregiving environments may influence how children process complex negative emotional scenes. The scenes included in this grouping were those that depict moments where Gru experiences separation from the girls and navigates the emotional process of coping with this separation. This finding complements the literature that uses static images where youth with the experience of adversity are able to better recognize sad and angry faces as opposed to happy or fearful ones (Saarinen et al., 2021). This could be because sad and emotional scenes contained more instances of sadness and anger, providing more opportunities for recognition and reactivity to these emotions. The portrayal of Gru's separation from the children, leading to heightened neural activation, draws parallels with research on parental and child separation. Specifically, emerging literature underscores the role of parenting and unpredictable environments in shaping emotion regulation and reactivity from infancy to adolescence (Tan et al., 2020) where disorganized attachment is linked to heightened emotional reactivity (Obeldobel et al., 2023) and separation from parents have shown consistent negative effects on overall child socio-emotional development (Waddoups et al., 2019). Further research characterizing how children with inconsistent caregiving process complex social cues over time would help elucidate how this pattern develops, informing socio-emotional intervention.

Other adversity indices such as parent psychopathology, socioeconomic factors, and negative life events did not show associations with our activation measures. This fails to replicate prior work (Chai et al., 2015, Dawson et al., 2003, George et al., 2024, Park et al., 2022) and suggests that not all types of adversity have the same impact on neural emotional processing. An important consideration not addressed is the timing of exposure to stressors (Gee and Casey, 2015, Lupien et al., 2009), which may influence these associations since short-term responses to stressors may differ significantly from longer-term impacts on emotion processing. Additionally, these associations suggest that unpredictable stressors may have a different impact on emotional processing than isolated or acute adverse experiences. Individual differences in resilience and vulnerability could play a role in the varying impacts; some individuals may have coping mechanisms that mitigate the impact of certain types of adversity (Cicchetti, 2016). For instance, an individual who has faced and overcome significant challenges in their childhood might develop a higher level of emotional resilience, enabling them to handle stress and adversity more effectively in adulthood (Masten, 2001). This aligns with the hidden talents framework, which suggests that individuals in harsh and unpredictable environments develop stress-adapted skills leading to positive developmental outcomes (Ellis et al., 2022).

Finally, it's important to acknowledge that the sample in this study was not specifically recruited for ELA, which could impact our understanding of certain associations and limited variance for some factors. Future work characterizing complex emotion processing in samples selected for specific high ELA is needed to replicate the associations we found. Nonetheless, our results provide important insight to the influence of ELA on emotion processing in a sample enriched for psychopathology with diverse ELA. Finally, it is also possible that there are sex or puberty related effects that influence our findings. Although it is beyond the scope of this study, future research could examine our observed effects in association each pubertal status and sex.

In conclusion, this study enhances our understanding of how stress-associated brain systems process complex emotional information. We found increased DMN, VAN, CON, and amygdala activation associated with scenes depicting sadness, emotional bonding, fear, and conflict. Activation in the DMN, VAN, CON, and amygdala was consistently elevated during scenes depicting sadness and bonding, with further increases in the VAN, CON, and amygdala observed in fear and pain scenes, while action scenes uniquely heightened DMN activity and conflict scenes specifically engaged the VAN and CON. These results add evidence to previous literature on the distinct roles of these networks in emotion processing. Youth with inconsistent disciplining showed increased VAN activation during sad/emotional and bonding scenes, suggesting sensitivity to disrupted parent-child relationships and the associated salient negative emotions. This work provides important insight to the conditions and context under which specific ELA may influence real-world emotion processing.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (MH132185 to MCC; MH109589 to DMB).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Deanna M. Barch: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. Jenna H. Chin: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. M. Catalina Camacho: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Emily J. Furtado: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the families that participated in the Healthy Brain Network project, the Child Mind Institute for sharing the data publicly, Sri Kandala for assistance with data processing, and Leah Fructman, Dori Balser, Elizabeth Williams, Arieona Witherspoon, and David Steinberger for coding the videos. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (MH132185 to MCC; MH109589 to DMB).

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2024.101469.

Appendices A-E. Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability

This manuscript used an open dataset. We include the link to the dataset in the manuscript.

References

- Adler N.E., Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: Pathways and policies. Health Aff. 2002;21:60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L.M., Escalera J., Ai L., Andreotti C., Febre K., Mangone A., Vega-Potler N., Langer N., Alexander A., Kovacs M., Litke S., O’Hagan B., Andersen J., Bronstein B., Bui A., Bushey M., Butler H., Castagna V., Camacho N., Chan E., Citera D., Clucas J., Cohen S., Dufek S., Eaves M., Fradera B., Gardner J., Grant-Villegas N., Green G., Gregory C., Hart E., Harris S., Horton M., Kahn D., Kabotyanski K., Karmel B., Kelly S.P., Kleinman K., Koo B., Kramer E., Lennon E., Lord C., Mantello G., Margolis A., Merikangas K.R., Milham J., Minniti G., Neuhaus R., Levine A., Osman Y., Parra L.C., Pugh K.R., Racanello A., Restrepo A., Saltzman T., Septimus B., Tobe R., Waltz R., Williams A., Yeo A., Castellanos F.X., Klein A., Paus T., Leventhal B.L., Craddock R.C., Koplewicz H.S., Milham M.P. An open resource for transdiagnostic research in pediatric mental health and learning disorders. Sci. Data. 2017;4 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J.L.R., Sotiropoulos S.N. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1063–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, W., 2012. Social class on campus: The Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (BSMSS). Social class on campus. URL 〈https://socialclassoncampus.blogspot.com/2012/06/barratt-simplified-measure-of-social.html〉 (accessed 12.11.23).

- Bernard F., Lemee J.-M., Mazerand E., Leiber L.-M., Menei P., Ter Minassian A. The ventral attention network: the mirror of the language network in the right brain hemisphere. J. Anat. 2020;237:632–642. doi: 10.1111/joa.13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A., Carlson S.M., Whipple N. From External Regulation to Self-Regulation: Early Parenting Precursors of Young Children’s Executive Functioning. Child Development. 2010;81:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner R.L., Andrews-Hanna J.R., Schacter D.L. The brain’s default network. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G., Luu P., Posner M.I. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000;4(00):215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613. 01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho M.C., Balser D.H., Furtado E.J., Rogers C.E., Schwarzlose R.F., Sylvester C.M., Barch D.M. Higher Intersubject Variability in Neural Response to Narrative Social Stimuli Among Youth With Higher Social Anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho M.C., Karim H.T., Perlman S.B. Neural architecture supporting active emotion processing in children: A multivariate approach. NeuroImage. 2019;188:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho M.C., Nielsen A.N., Balser D., Furtado E., Steinberger D.C., Fruchtman L., Culver J.P., Sylvester C.M., Barch D.M. Large-scale encoding of emotion concepts becomes increasingly similar between individuals from childhood to adolescence. Nat. Neurosci. 2023;26:1256–1266. doi: 10.1038/s41593-023-01358-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho M.C., Williams E.M., Balser D., Kamojjala R., Sekar N., Steinberger D., Yarlagadda S., Perlman S.B., Barch D.M. EmoCodes: a Standardized Coding System for Socio-emotional Content in Complex Video Stimuli. Affec Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s42761-021-00100-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahal R., Miller J.G., Yuan J.P., Buthmann J.L., Gotlib I.H. An exploration of dimensions of early adversity and the development of functional brain network connectivity during adolescence: implications for trajectories of internalizing symptoms. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022;34:557–571. doi: 10.1017/S0954579421001814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai X.J., Hirshfeld-Becker D., Biederman J., Uchida M., Doehrmann O., Leonard J.A., Salvatore J., Kenworthy T., Brown A., Kagan E., de los Angeles C., Whitfield-Gabrieli S., Gabrieli J.D.E. Functional and structural brain correlates of risk for major depression in children with familial depression. NeuroImage: Clin. 2015;8:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Baram T.Z. Toward Understanding How Early-Life Stress Reprograms Cognitive and Emotional Brain Networks. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;41:197–206. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2013. Overview of Adverse Child and Family Experiences among US Children.

- Cicchetti D. John Wiley & Sons; 2016. Developmental Psychopathology, Risk, Resilience, and Intervention. [Google Scholar]

- Cisler J.M., Scott Steele J., Smitherman S., Lenow J.K., Kilts C.D. Neural processing correlates of assaultive violence exposure and PTSD symptoms during implicit threat processing: A network-level analysis among adolescent girls. Psychiatry Res.: Neuroimaging. 2013;214:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M., Patel G., Shulman G.L. The Reorienting System of the Human Brain: From Environment to Theory of Mind. Neuron. 2008;58:306–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M., Shulman G.L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:201–215. doi: 10.1038/nrn755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese S., Kelly C., Chabernaud C., Proal E., Di Martino A., Milham M.P., Castellanos F.X. Toward Systems Neuroscience Of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. AJP. 2012;169:1038–1055. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste C.P., Kleinschmidt A. Cingulo-opercular network activity maintains alertness. NeuroImage. 2016;128:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N.R., Dodge K.A. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 1994;115:74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G., Ashman S.B., Panagiotides H., Hessl D., Self J., Yamada E., Embry L. Preschool outcomes of children of depressed mothers: role of maternal behavior, contextual risk, and children’s brain activity. Child Dev. 2003;74:1158–1175. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach N.U.F., Fair D.A., Cohen A.L., Schlaggar B.L., Petersen S.E. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008;12:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N., Cumberland A., Spinrad T.L. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychol. Inq. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B.J., Sheridan M.A., Belsky J., McLaughlin K.A. Why and how does early adversity influence development? Toward an integrated model of dimensions of environmental experience. Dev. Psychopathol. 1–25. 2022 doi: 10.1017/S0954579421001838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A., Egner T., Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011;15:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans G.W., Kim P. Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013;7:43–48. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D.F., Spitz A.M., Edwards V., Koss M.P., Marks J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14(98):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797. 00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee D.G., Casey B.J. The impact of developmental timing for stress and recovery. Neurobiol. Stress, Stress Resil. 2015;1:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George G.C., Heyn S.A., Russell J.D., Keding T.J., Herringa R.J. Parent Psychopathology and Behavioral Effects on Child Brain–Symptom Networks in the ABCD Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb B.E., Schofield C.A., Coles M.E. Reported history of childhood abuse and young adults’ information-processing biases for facial displays of emotion. Child Maltreat. 2009;14:148–156. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser M.F., Sotiropoulos S.N., Wilson J.A., Coalson T.S., Fischl B., Andersson J.L., Xu J., Jbabdi S., Webster M., Polimeni J.R., Van Essen D.C., Jenkinson M. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage. 2013;80:105–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S.H., Gotlib I.H. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol. Rev. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon E.M., Laumann T.O., Adeyemo B., Huckins J.F., Kelley W.M., Petersen S.E. Generation and evaluation of a cortical area parcellation from resting-state correlations. Cereb. Cortex. 2016;26:288–303. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J.G., McLaughlin K.A., Berglund P.A., Gruber M.J., Sampson N.A., Zaslavsky A.M., Kessler R.C. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication i: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C.R., Millman K.J., van der Walt S.J., Gommers R., Virtanen P., Cournapeau D., Wieser E., Taylor J., Berg S., Smith N.J., Kern R., Picus M., Hoyer S., van Kerkwijk M.H., Brett M., Haldane A., del Río J.F., Wiebe M., Peterson P., Gérard-Marchant P., Sheppard K., Reddy T., Weckesser W., Abbasi H., Gohlke C., Oliphant T.E. Array programming with NumPy. Nature. 2020;585:357–362. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri A.R., Tessitore A., Mattay V.S., Fera F., Weinberger D.R. The amygdala response to emotional stimuli: a comparison of faces and scenes. NeuroImage. 2002;17:317–323. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart H., Lim L., Mehta M.A., Simmons A., Mirza K. a H., Rubia K. Altered fear processing in adolescents with a history of severe childhood maltreatment: an fMRI study. Psychol. Med. 2018;48:1092–1101. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoemann K., Xu F., Barrett L.F. Emotion words, emotion concepts, and emotional development in children: a constructionist hypothesis. Dev. Psychol. 2019;55:1830–1849. doi: 10.1037/dev0000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead, August, 1957. Two factor index of social position.

- Hollingshead, August, 1975. Four-factor index of social status.

- Hostinar C.E., Gunnar M.R. The Developmental Effects of Early Life Stress: An Overview of Current Theoretical Frameworks. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013;22:400–406. doi: 10.1177/0963721413488889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K., Bellis M.A., Hardcastle K.A., Sethi D., Butchart A., Mikton C., Jones L., Dunne M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(17) doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667. e356–e366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson J.M. Developmental Variability and Developmental Cascades: Lessons From Motor and Language Development in Infancy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2021;30:228–235. doi: 10.1177/0963721421993822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser R.H., Andrews-Hanna J.R., Wager T.D., Pizzagalli D.A. Large-Scale Network Dysfunction in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-analysis of Resting-State Functional Connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:603–611. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamps F.S., Richardson H., Murty N.A.R., Kanwisher N., Saxe R. Using child-friendly movie stimuli to study the development of face, place, and object regions from age 3 to 12 years. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022;43:2782–2800. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J., Birmaher B., Brent D., Rao U., Flynn C., Moreci P., Williamson D., Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.J., Diamond D.M. The stressed hippocampus, synaptic plasticity and lost memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:453–462. doi: 10.1038/nrn849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad K., Eickhoff S.B. Is the ADHD brain wired differently? A review on structural and functional connectivity in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010;31:904–916. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise E.A., Arsenio W.F. An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Dev. 2000;71:107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien S.J., McEwen B.S., Gunnar M.R., Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malter Cohen M., Jing D., Yang R.R., Tottenham N., Lee F.S., Casey B.J. Early-life stress has persistent effects on amygdala function and development in mice and humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:18274–18278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310163110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 2001;56:227–238. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S., Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010;22:491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory E., Foulkes L., Viding E. Social thinning and stress generation after childhood maltreatment: a neurocognitive social transactional model of psychiatric vulnerability. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;(22) doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366. 00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K.A., Colich N.L., Rodman A.M., Weissman D.G. Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: a transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Med. 2020;18:96. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01561-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K.A., Lambert H.K. Child trauma exposure and psychopathology: mechanisms of risk and resilience. Curr. Opin. Psychol., Trauma. Stress. 2017;14:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K.A., Peverill M., Gold A.L., Alves S., Sheridan M.A. Child maltreatment and neural systems underlying emotion regulation. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2015;54:753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K.A., Sheridan M.A. Beyond Cumulative Risk: A Dimensional Approach to Childhood Adversity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2016;25:239–245. doi: 10.1177/0963721416655883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K.A., Weissman D., Bitrán D. Childhood adversity and neural development: a systematic review. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2019;1:277–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-084950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V.C. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am. Psychol. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V. 20 years of the default mode network: a review and synthesis. Neuron. 2023;111:2469–2487. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Uddin L.Q. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010;214:655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L.E. Perceived threat in childhood: a review of research and implications for children living in violent households. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2015;16:153–168. doi: 10.1177/1524838013517563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello-Frosch R., Shenassa E.D. The environmental “riskscape” and social inequality: implications for explaining maternal and child health disparities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:1150–1153. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujahid M.S., Diez Roux A.V., Morenoff J.D., Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: from psychometrics to ecometrics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;165:858–867. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold D.J., Gordon E.M., Laumann T.O., Seider N.A., Montez D.F., Gross S.J., Zheng A., Nielsen A.N., Hoyt C.R., Hampton J.M., Ortega M., Adeyemo B., Miller D.B., Van A.N., Marek S., Schlaggar B.L., Carter A.R., Kay B.P., Greene D.J., Raichle M.E., Petersen S.E., Snyder A.Z., Dosenbach N.U.F. Cingulo-opercular control network and disused motor circuits joined in standby mode. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019128118. e2019128118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeldobel C.A., Brumariu L.E., Kerns K.A. Parent–Child Attachment and Dynamic Emotion Regulation: A Systematic Review. Emot. Rev. 2023;15:28–44. doi: 10.1177/17540739221136895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park A.T., Richardson H., Tooley U.A., McDermott C.L., Boroshok A.L., Ke A., Leonard J.A., Tisdall M.D., Deater-Deckard K., Edgar J.C., Mackey A.P. Early stressful experiences are associated with reduced neural responses to naturalistic emotional and social content in children. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022;57 doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2022.101152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C.C., Wellman H.M., Slaughter V. The mind behind the message: advancing theory-of-mind scales for typically developing children, and those with deafness, autism, or asperger syndrome. Child Dev. 2012;83:469–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan K.L., Wager T., Taylor S.F., Liberzon I. Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: a meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage. 2002;16:331–348. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps E.A., LeDoux J.E. Contributions of the Amygdala to Emotion Processing: From Animal Models to Human Behavior. Neuron. 2005;48:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak S.D., Cicchetti D., Hornung K., Reed A. Recognizing emotion in faces: Developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Dev. Psychol. 2000;36:679–688. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak S.D., Sinha P. Effects of early experience on children’s recognition of facial displays of emotion. Dev. Psychol. 2002;38:784–791. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak S.D., Smith K.E. Thinking clearly about biology and childhood adversity: next steps for continued progress. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021;16:1473–1477. doi: 10.1177/17456916211031539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle M.E., Snyder A.Z. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. NeuroImage. 2007;37:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebello K., Moura L.M., Pinaya W.H.L., Rohde L.A., Sato J.R. Default mode network maturation and environmental adversities during childhood. Chronic Stress. 2018;2 doi: 10.1177/2470547018808295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson H. Development of brain networks for social functions: Confirmatory analyses in a large open source dataset. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019;37 doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E.C., Garcia K., Glasser M.F., Chen Z., Coalson T.S., Makropoulos A., Bozek J., Wright R., Schuh A., Webster M., Hutter J., Price A., Cordero Grande L., Hughes E., Tusor N., Bayly P.V., Van Essen D.C., Smith S.M., Edwards A.D., Hajnal J., Jenkinson M., Glocker B., Rueckert D. Multimodal surface matching with higher-order smoothness constraints. Neuroimage. 2018;167:453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruba A.L., Pollak S.D. The development of emotion reasoning in infancy and early childhood. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2020;2:503–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-060320-102556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen A., Keltikangas-Järvinen L., Jääskeläinen E., Huhtaniska S., Pudas J., Tovar-Perdomo S., Penttilä M., Miettunen J., Lieslehto J. Early adversity and emotion processing from faces: a meta-analysis on behavioral and neurophysiological responses. Biol. Psychiatry.: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2021;6:692–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I., Wolchik S., Braver S., Fogas B. Stability and quality of life events and psychological symptomatology in children of divorce. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1991;19:501–520. doi: 10.1007/BF00937989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago C.D., Wadsworth M.E., Stump J. Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. J. Econ. Psychol., Spec. Issue Psychol. Behav. Econ. Poverty. 2011;32:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley W.W., Menon V., Schatzberg A.F., Keller J., Glover G.H., Kenna H., Reiss A.L., Greicius M.D. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitzman B.A., Gratton C., Marek S., Raut R.V., Dosenbach N.U.F., Schlaggar B.L., Petersen S.E., Greene D.J. A set of functionally-defined brain regions with improved representation of the subcortex and cerebellum. Neuroimage. 2020;206 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton K.K., Frick P.J., Wootton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1996;25:317–329. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2503_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J.S., Mitra A., Laumann T.O., Seitzman B.A., Raichle M., Corbetta M., Snyder A.Z. Data Quality Influences Observed Links Between Functional Connectivity and Behavior. Cereb. Cortex. 2017;27:4492–4502. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J.S., Power J.D., Dubis J.W., Vogel A.C., Church J.A., Schlaggar B.L., Petersen S.E. Statistical improvements in functional magnetic resonance imaging analyses produced by censoring high-motion data points. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014;35:1981–1996. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood J., Bernhardt B.C., Leech R., Bzdok D., Jefferies E., Margulies D.S. The default mode network in cognition: a topographical perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021;22:503–513. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.E., Pollak S.D. Rethinking concepts and categories for understanding the neurodevelopmental effects of childhood adversity. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021;16:67–93. doi: 10.1177/1745691620920725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville L.H., Fani N., McClure-Tone E.B. Behavioral and neural representation of emotional facial expressions across the lifespan. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2011;36:408–428. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.549865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J.M., Schuck S., Porter M.M., Carlson C., Hartman C.A., Sergeant J.A., Clevenger W., Wasdell M., McCleary R., Lakes K., Wigal T. Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: history of the SNAP and the SWAN rating scales. Int J. Educ. Psychol. Assess. 2012;10:51–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester C.M., Barch D.M., Corbetta M., Power J.D., Schlaggar B.L., Luby J.L. Resting state functional connectivity of the ventral attention network in children with a history of depression or anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2013;52:1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.10.001. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P.Z., Oppenheimer C.W., Ladouceur C.D., Butterfield R.D., Silk J.S. A review of associations between parental emotion socialization behaviors and the neural substrates of emotional reactivity and regulation in youth. Dev. Psychol. 2020;56:516–527. doi: 10.1037/dev0000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]