Abstract

Translational biology posits a strong bi-directional link between clinical phenotypes and a patient’s biological profile. By leveraging this bi-directional link, we can efficiently deconvolute pre-existing clinical information into biological profiles. However, traditional computational tools are limited in their ability to resolve this link because of the relatively small sizes of paired clinical–biological datasets for training and the high dimensionality/sparsity of tabular clinical data. Here, we use state-of-the-art foundation models (FMs) for electronic health record (EHR) data to generate proteomics profiles of pregnant patients, thereby deconvoluting pre-existing clinical information into biological profiles without the cost and effort of running large-scale traditional omics studies. We show that FM-derived representations of a patient’s EHR data coupled with a fully connected neural network prediction head can generate 206 blood protein expression levels. Interestingly, these proteins were enriched for developmental pathways, while proteins not able to be generated from EHR data were enriched for metabolic pathways. Finally, we show a proteomic signature of gestational diabetes that includes proteins with established and novel links to gestational diabetes. These results showcase the power of FM-derived EHR representations in efficiently generating biological states of pregnant patients. This capability can revolutionize disease understanding and therapeutic development, offering a cost-effective, time-efficient, and less invasive alternative to traditional methods of generating proteomics.

Keywords: electronic health record, proteomics, foundation model, machine learning, pregnancy

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Translational biological science is built on the assumption that there is a strong bi-directional link between the biological state of a patient and their observed clinical manifestations. Computational biologists rely on this link to develop machine-learning models that can predict numerous clinical outcomes from biological omics data. Examples include using liquid biopsy proteomics/transcriptomics to predict retinal degeneration [1], proteomics to predict gestational age [2], and metabolomics to predict 23 different clinical conditions [3]. These models not only successfully predicted clinical outcomes but also identified various links between biology and clinical phenotypes, such as 20 proteins related to retinal aging [1], which can be further investigated in future studies for therapeutics and novel biological insight.

But importantly, the link between biology and clinical phenotypes is bi-directional. The success of using biological data to predict clinical outcomes suggests the potential of the converse—using clinical information to generate biological profiles of patients. The use of pre-existing clinical data to generate patient biological profiles could greatly reduce the cost, time, and invasive nature of generating large-scale omics. The resulting biological data could be used to power new and interesting biological discoveries similar to traditionally generated omics data. In addition, it could generate new insights into which clinical phenotypes are most predictive of specific biomarkers that can be used downstream for development of novel diagnostic tools and personalized therapeutics. Some studies have combined clinical and omics data to predict various clinical outcomes [4, 5] or used one omics modality to predict others [6]. However, no study to our knowledge has yet attempted to use clinical data to generate biological omics possibly due to the difficulty of obtaining large paired clinical-omics datasets for training and the difficulties of working with the sparsity and high-dimensionality of tabular clinical data.

Foundation models (FMs) are flexible and generalizable artificial intelligence models typically trained on a large training cohort. They excel at encoding generally useful dense latent representations of high-dimensional data that can be further fine-tuned, using much smaller datasets, for diverse downstream tasks [7]. FMs have revolutionized the development of machine learning algorithms across multiple fields, including healthcare. Clinical language models, a highly popular FM architecture in healthcare, are models designed to process text-like data [8]. Clinical-language-model FMs such as BioClinicalBERT that were trained on biomedical literature and clinical data demonstrated improved performance in multiple domain-specific tasks compared to general FMs like Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [9], demonstrating their utility in solving biomedical problems.

A valuable source of rich clinical information is the electronic health record (EHR). EHR systems are now used at 96% of US hospitals (as of 2021 [10]), meaning that most US patients have pre-existing and continuously increasing amounts of clinical data. This presents a rich opportunity for EHR-specific FMs to advance healthcare. Recently, various groups have released EHR-specific FMs including two state-of-the-art models MOTOR (Many Outcome Time Oriented Representations) [11] (a time-to-event model trained on 8192 clinical prediction tasks) and CLMBR (Clinical Language Model Based Representations) [12] (trained as a next-diagnostic code prediction model). These two FM models demonstrated superior performance across multiple different clinical prediction tasks compared to other machine learning models such as DeepSurv (a different time-to-event model for survival analysis) or Word2Vec (a popular general text representation model) [11, 12]; thus, these EHR-specific FMs appear to achieve powerful generalizable latent representations of EHR data.

Here, we use two state-of-the-art EHR FMs (MOTOR and CLMBR) to generate blood proteomics expression from EHR data in a cohort of healthy pregnant participants. We show that EHR data can be used to accurately generate the blood expression values of 206 proteins in pregnant patients. We show that these proteins are enriched in developmental pathways, while proteins that could not be accurately generated were enriched in metabolic pathways. Finally, we highlight the ability of our model to discover novel clinical and biological insights by identifying a proteomics signature for gestational diabetes. These results open the possibility of using clinical data, such as EHRs, to quickly and efficiently generate the biological profiles of patients.

Results

Generation of electronic health record representations

We used two state-of-the-art EHR FMs, MOTOR [11] and CLMBR [12], to create latent representations of patient EHRs for use in proteomics generation. While both FMs were designed to predict clinical events from EHR data, they have distinct training regimens. Mainly, MOTOR was trained as a time-to-event model, while CLMBR was trained using a next-code prediction task [11, 12]. Comparing their performance may provide insight into what aspects of EHR FMs are most helpful in deconvoluting clinical data into proteomics profiles.

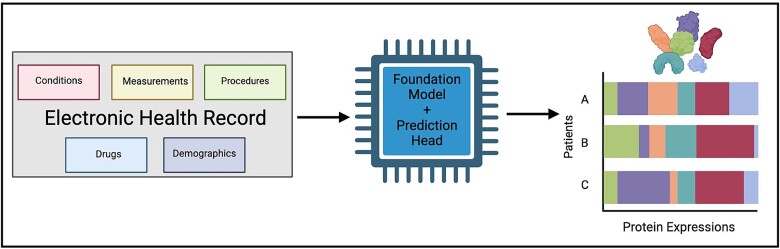

The FMs condense conditions, drugs, measurements, procedures, and demographic information contained in a patient’s EHR into dense fixed-length 768-element vector representations. To do so, all EHR data encompassing conditions, drugs, measurements, procedures, and demographic information of 61 healthy pregnant patients between 22 and 40 years old in the EHR system of Stanford Hospital and Clinics or Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital originally described in Stelzer et al. [13] were collected for input into MOTOR and CLMBR. Paired proteomics was obtained from plasma samples taken at various timepoints throughout pregnancy [13] (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. S1a–c). Each patient had between one and three samples collected, with most (84%) having three collected samples (Supplementary Fig. S1d). The expression values of 1305 proteins were measured through the SomaLogic platform. The median span of EHR data across all samples was 1.5 years (Fig. 1b). The median number of unique EHR features recorded for a given sample was 163 (Supplementary Fig. S1e). Importantly, the paired EHR data for each proteomics sample were limited to records up to and including the collection date for the proteomics plasma sample to better simulate the real-world scenario where we would not have access to “future” data.

Figure 1.

Integration of EHR and proteomics data of pregnant patients using electronic medical record–trained FMs. (a) To train a model capable of efficiently generating proteomics profiles from existing EHR records of pregnant patients, we collected paired EHR–proteomics samples. Proteomics data were collected for each patient from a minimum of one and a maximum of three plasma samples collected per patient. One thousand three hundred five proteins were measured per patient. Patient EHR records were obtained from the earliest EHR entry at Stanford to the sample collection date. Our final cohort had n = 171 samples from N = 61 unique individuals. G1, G2, and G3 represent various gestation time periods where plasma was sampled for proteomics (run on SomaLogic’s platform). (b) EHR records of samples encompassed a wide range of duration, spanning a minimum of 1 month to a maximum of 14.3 years with a median of 1.5 years. (c) Two state-of-the-art EHR foundation models were used to generate low-dimensional latent representations of EHR data for the generation of proteomics expression. EHR records encompassed five categories: demographics, drugs, conditions, procedures, and measurements. Preprocessed EHR data were fed into FMs MOTOR and CLMBR to generate a 768-dimensional vector representation of a sample’s EHR data up to and including the sample collection date. Representations and paired protein expression from proteomics data were used to train 1305 single-task neural networks consisting of two fully connected layers to generate protein expression values for 1305 proteins. Generative performance was assessed by calculating the Spearman correlation between actual and generated values of each protein with a P-value corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.

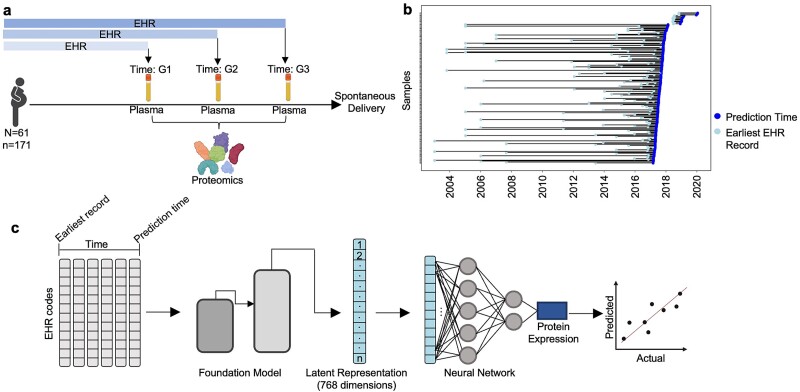

FM representations of EHR data can generate expression values of various proteins

Using MOTOR or CLMBR representations of EHR data, we generated expression values of 206 proteins with significant (Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P-value <.05) Spearman correlation coefficients between actual and generated values (hereafter referred to as significant proteins) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S1). Spearman coefficients for each protein were strongly correlated between MOTOR and CLMBR with a Pearson coefficient of 0.63 (P-value = 3.01e-147), indicating that both FM representations were useful in generating proteomics (Fig. 2a). Indeed, the results for our top proteins are reproducible using both MOTOR and CLMBR representations (Supplementary Fig. S2a and b). However, a detailed comparison revealed that MOTOR representations were better able to generate proteomics as shown by their greater average Spearman coefficient in comparison to that of CLMBR (0.42 versus 0.33, P-value = 4.94e-10) (Fig. 2b). In addition, MOTOR representations resulted in 119 unique significant proteins, while CLMBR resulted in 29 (Fig. 2c). These results were stable across 10 bootstrap iterations, demonstrating the reproducibility of these results (Supplementary Fig. S3). Our results demonstrate that the choice of FM to encode EHR data is important when generating proteomics.

Figure 2.

FM representations of EHR data generate proteomics expression values. (a) Scatterplot demonstrates that both MOTOR and CLMBR representations of EHR data are useful in generating protein expression values from EHR data. Axes plot Spearman coefficients between actual and generated values for each protein when generated using MOTOR (x-axis) and CLMBR (y-axis) representations. Select top proteins are labeled. Gray dots indicate proteins with adjusted P-value >.05 for both models. Dotted red line indicates theoretically equal performance by both models. Pearson correlation of the Spearman coefficients for proteins across MOTOR and CLMBR was calculated to assess the correlation of performance. P-value of the Pearson coefficient was 3.01e-147. (b) To determine if the choice of FM matters for proteomics generation, we directly compared the generative performance of MOTOR versus CLMBR. Line graph shows the change in Spearman correlation for each protein when generated using MOTOR versus CLMBR representations of EHR data. Gray lines are proteins with adjusted P-value >.05 for either model representation. Red lines indicate an increase in Spearman correlation for a given protein from CLMBR to MOTOR while blue lines indicate a decrease in Spearman correlation. * denotes significant adjusted P-value (P = 4.94e-10) using paired Wilcoxon test. (c): Venn diagram of the number of proteins with significant adjusted P-value (<.05) for each model shows MOTOR had approximately four times as many significant proteins compared to CLMBR. (d) Scatterplot showing actual (x-axis) and generated (y-axis) values for the top six proteins generated using MOTOR and CLMBR representations. Generated protein expression values for each patient sample are the average generated value of 10 bootstrap iterations. Line shows the line of best fit with a 95% confidence interval shaded. n = 171.

Our cohort had a wide range of EHR lengths, ranging from ~16 days to 14 years. Consequently, we examined the relationship between EHR length and generative performance per sample. We observed an inverse correlation (Pearson correlation of −0.11) between EHR length and average absolute error for a given sample; however, it did not achieve statistical significance (P-value = .17) (Supplementary Fig. S4). We also observed that the variance in error was lower for samples with longer (>8-year) EHR records (Supplementary Fig. S4).

We focused on the proteins with the highest Spearman coefficients across both FMs, which included sST2, SIGLEC6, PLXNB2, CST3, DDR1, and INHBA, to assess the accuracy and biological relevance of our model (Fig. 2d). Interestingly, all have been linked to pregnancy by previous studies. sST2 has been linked to immune response and preeclampsia in pregnancy [14, 15]. SIGLEC6 has also been linked to preeclampsia and placental function [16, 17]. PLXNB2 has been linked to embryo attachment [18]. CST3 has been shown to be linked to renal function in pregnant women [19, 20]. DDR1 has been linked to mammary gland development and blastocyst implantation [21]. INHBA has been linked to preeclampsia and other gestational diseases [22]. The actual measured values of these six proteins increase over time in our cohort (Supplementary Fig. S5). Our generated values using both MOTOR and CLMBR mirror the expression level changes throughout pregnancy, demonstrating that our model can generate expression levels of proteins that change over time in pregnant patients.

Finally, we observed that the correlation between actual and generated values weakened for samples with high protein expression as shown by the wider confidence intervals (Fig. 2d). A deeper investigation showed that most (96% of all 1305 proteins) of our proteins’ true expressions exhibited right-skewed expression patterns (Supplementary Fig. S6a). The degree of right-skewedness was inversely correlated with model performance as measured by Spearman correlation for both MOTOR and CLMBR representations (Supplementary Fig. S6b–d). This could be due to a lack of enough samples with high protein expression, a lack of specificity of the proteomics data above a certain threshold, or because the real expression pattern of these proteins in the population resembles a bimodal or stepwise function.

In summary, FM representations of EHR data can be used to deconvolute clinical data to generate protein expression profiles. Overall, we accurately generated 206 proteins: 119 using MOTOR representations of EHR data, 29 by CLMBR representations, and 58 by both representations (Fig. 2c). Importantly, MOTOR representations are better able to generate protein expressions compared to CLMBR representations, indicating that the choice of FM matters for this generative task.

Intraindividual variations in protein expression are better generated

Our cohort, with multiple timepoints per patient, enabled us to compare interindividual and intraindividual protein expression differences. We observed greater interindividual variance across 1305 proteins (Supplementary Fig. S7a). We then developed two models: first, predicting other patients’ first timepoint proteomics using one patient’s first timepoint (“interindividual model”) and second, predicting subsequent timepoints within the same patient using the first timepoint (“intraindividual model”). The intraindividual model outperformed the interindividual model, aligning with the lower observed intraindividual variance (Supplementary Fig. S7b).

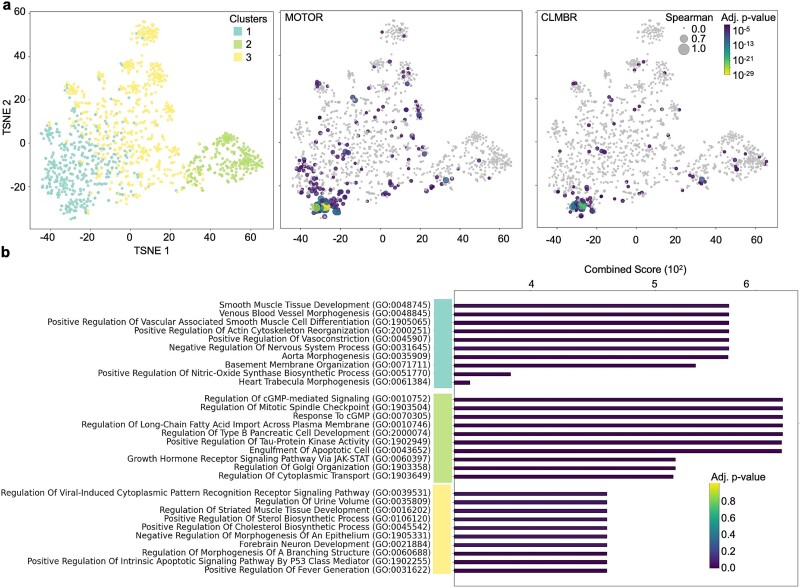

Significant proteins are enriched in development-related pathways

To reveal the biological functional qualities that differentiate significant from nonsignificant proteins, we compared the biological pathways that define each category of proteins. We performed k-means clustering and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) dimensionality reduction on a Pearson correlation matrix of protein expression values to find clusters of proteins enriched for significant proteins and those enriched for non-significant proteins. Most of the significant proteins, 151/177 from MOTOR and 66/87 from CLMBR, were in clusters 1 and 3, while only 2/177 and 9/87 significant proteins, respectively, were in cluster 2 (Fig. 3a). Pathway analysis of all proteins in each cluster using Gene Ontology (GO) pathways showed that clusters 1 and 3 were enriched for developmental pathways, pathways that are likely highly active and important during pregnancy (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, cluster 2 was enriched for metabolism-related pathways (Fig. 3b), indicating that metabolism-related proteins may be difficult to generate from EHR data.

Figure 3.

Significant proteins are enriched in development-related pathways. (a) To identify biological patterns in significant versus nonsignificant proteins, k-means clustering and tSNE dimensionality reduction for visualization were performed using protein expression correlations. Pearson correlation matrix was calculated using protein expressions of all proteins across all patient samples. (Left) Cluster number was determined using an elbow plot and piecewise regression. K-means clustering was performed on the correlation matrix. Significant proteins were concentrated in clusters 1 and 3. Nonsignificant proteins were concentrated in cluster 2. Dot sizes indicate Spearman correlation, and color indicates the adjusted P-value of the protein when generated using MOTOR (middle) or CLMBR (right) representations of EHR data. Gray dots are proteins with adjusted P-value >.05. (b): Proteins in each cluster were analyzed by gene set enrichment analysis. The top 10 results for each cluster ranked by combined score (a ranking metric that adjusts for varying lengths of gene sets in each GO developed by Enrichr) after filtering for significant (adjusted P-value <.05) GO pathways are shown. Cluster 1 and 3 proteins, which have the highest number of significant proteins, are enriched in developmental pathways while cluster 2, which has the lowest number of significant proteins, is enriched in metabolic pathways.

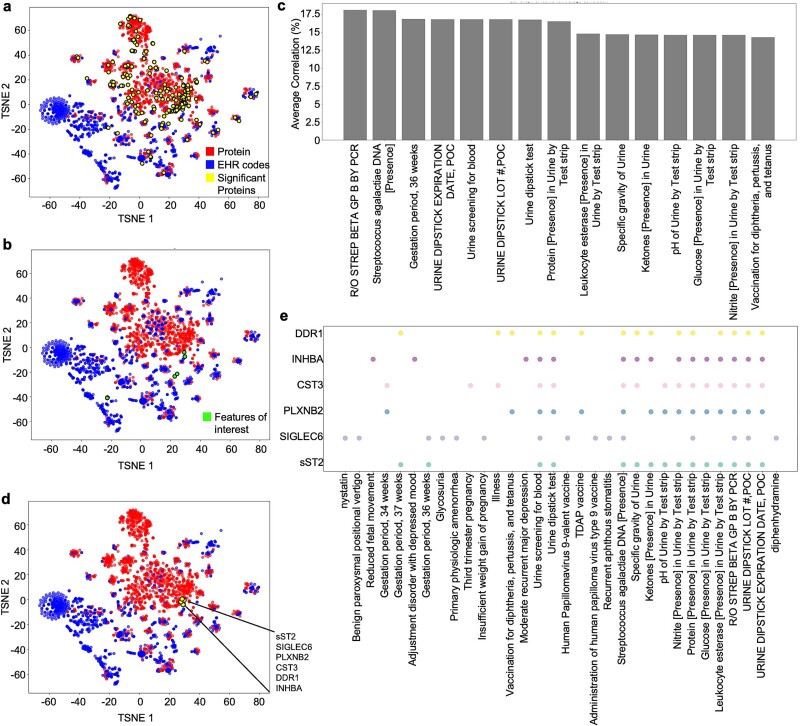

Next, we identified the most informative clinical data for generating proteomics biology by examining Pearson correlations between the true protein expressions and EHR feature counts. A linear correlation is an easily interpretable metric capable of identifying which clinical features are highly associated with fluctuations in protein expression. The 206 significant proteins clustered near specific features, indicating their potential utility in generating proteomics expressions (Fig. 4a). The top 15 of these features with the highest average absolute correlation values across the 206 proteins were extracted for further analysis (Fig. 4b and c). Some of these features were directly or indirectly linked to pregnancy/gestation time such as gestation periods or group B strep (GBS) testing (often performed close to delivery date). But interestingly, many of the features were related to immune or urine measurements including glucose and ketones (Fig. 4c). Focusing on the top (Spearman correlation >0.6 with MOTOR representations, six total proteins) significant proteins, we found that they cluster together (Fig. 4d). When the top 15 features most correlated to each of the top six proteins were extracted, many of the features aligned with the features from Fig. 4b with even more pregnancy-, glucose-, and urine-related features (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. S8). This result is consistent with previous literature that have identified critical roles for all six top significant proteins [14–21, 23] including CST3, which has been shown to be an important marker of renal damage in pregnant women [19, 20]. Collectively, our results indicate that immune features (i.e. vaccinations) and pregnancy-related urine tests (i.e. urine glucose and ketones) are most linearly correlated with protein expression.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis reveals that immune and urine-related clinical features are most associated with significant proteins. (a) To identify EHR features most linearly associated with protein expression, tSNE dimensionality reduction of EHR–protein Pearson correlations was performed, revealing select features that clustered close to significant proteins. EHR count matrix was created by counting the number of times each code appeared in a patient’s record. Final EHR feature count matrix was concatenated with the true protein expression matrix for correlation calculation. Points were colored by category (protein or feature). Yellow proteins are all significantly predicted proteins using either MOTOR or CLMBR (206 proteins). (b) Top 15 EHR features with the highest average correlation across all 206 significantly predicted proteins are marked as green. (c) Average correlation of the top 15 EHR features (marked in green in Fig. 4b) with the highest average correlation across all 206 significantly predicted proteins were identified. Features include various gestation time points, urinalysis assays, and vaccinations. (d) Top proteins with the highest (>0.6) Spearman coefficients in the MOTOR model were identified on the tSNE to determine the top features that were most closely correlated to the proteins. (e) Top 15 features with the highest correlation for each protein. Dot represents the presence of a feature (x-axis) in the top 15 most correlated features list for a given protein (y-axis).

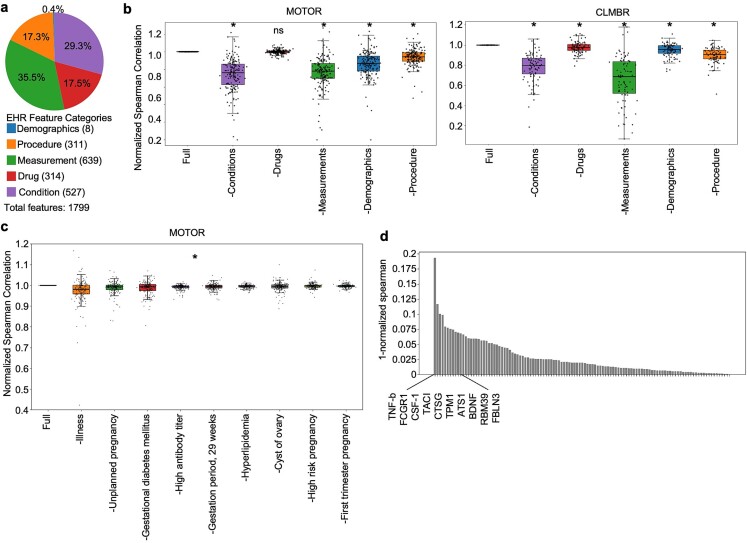

Conditions are the most important electronic health record features for generating proteomics expression

While linear correlation analysis offers valuable insight into highly correlated individual feature–protein pairs, machine learning–based models also capture complex, nonlinear relationships between features and outcomes that would be missed by traditional linear correlation associations. Consequently, we performed dropout feature importance to identify the clinical information most important in our model’s generative performance. Our EHR data were grouped into five categories: demographics, procedures, measurements, drugs, and conditions (Fig. 5a). We conducted dropout feature importance analysis by systematically removing one category of EHR data and rerunning our model. Five “dropout representations” were created, and their performances were compared against the reference model that had no dropped categories (hereafter referred to as the “full” model). Performance was assessed by comparing the normalized Spearman coefficients (the Spearman coefficient of each dropout representation divided by the full model’s Spearman coefficient) for each of the 177 significant proteins for MOTOR and 87 for CLMBR using the paired Wilcoxon test with multiple hypothesis correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Model performance for both MOTOR and CLMBR representations significantly decreased for all dropout representations except drugs in MOTOR (Fig. 5b). Removing conditions led to a 26% and 22% average decrease of Spearman correlations across significant proteins in MOTOR and CLMBR, respectively. Removing measurements led to a 23% and 35% decrease for MOTOR and CLMBR, respectively. Drugs were least useful in generating proteomics expression using both representations with a drop of 0.01% and 2% for MOTOR and CLMBR, respectively. In summary, conditions were the most important category of EHR features for MOTOR, our best-performing FM, while drugs were the least important across both FMs for generating proteomics profiles.

Figure 5.

Dropout feature importance analysis reveals proteomic signature of gestational diabetes. (a) In addition to simple linear associations, machine learning models can capture complex nonlinear relationships between features and output. To identify such complex biological relationships useful in proteomics generation, dropout feature importance was performed to identify EHR features most helpful in generating proteomics expressions. A total of 1799 unique EHR records that were recorded for at least one sample are grouped into the five EHR categories as shown. (b) Each category of EHR information in Fig. 5a was dropped one at a time before creating FM-derived representations of EHR data for a dropout feature importance analysis. These five dropout representations were used as input to models for each protein trained on the full EHR representation created in Fig. 2. Dropout model performance was compared to the full model’s performance by comparing normalized Spearman correlations to the full model (Spearman correlation of dropout EHR representation/Spearman correlation of full EHR representation) for each protein. X-axis labels are formatted as follows: −X where X is the EHR category removed when creating FM representations. * denotes adjusted P-value statistical significance up to four decimal places using paired Wilcoxon test with multiple hypothesis correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Condition codes were most important for MOTOR representations, while drugs were least important. (c) To identify which specific condition codes were most important in generative performance, a dropout experiment for individual condition codes was conducted similar to Fig. 5b using MOTOR representations. Only MOTOR-significant proteins (177 proteins) were used for analysis. *All conditions shown have normalized Spearman correlation significantly different from that of the full model (paired Wilcoxon test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple hypothesis testing). See Supplementary Table S2 for a full list. (d) Out of the top conditions shown in Fig. 5c, gestational diabetes was particularly interesting due to its specificity. To determine a proteomic signature for gestational diabetes, we identified all proteins with a decrease in generative performance when the gestational diabetes code was removed from their EHR. One hundred fifteen proteins had decreased Spearman coefficients when compared to Spearman coefficients generated with the full model, indicating a link between them and gestational diabetes. The top 10 are highlighted here. For a full list, see Supplementary Table S3. Proteins with established and novel links to gestational diabetes were identified.

Dropout feature importance reveals proteomic signature of gestational diabetes

To obtain a finer resolution on which specific clinical conditions were most essential to generating proteomics expression, we performed 527 dropout feature importance analyses with single-code dropouts of all unique condition codes. Of the 527 unique condition codes, we found dropping 116 of them caused a significant decrease in normalized Spearman correlations compared to the full model for MOTOR and 228 for CLMBR using the paired Wilcoxon test with multiple hypothesis correction. Of the top 10 condition dropouts for each FM ranked by a drop in median normalized Spearman correlation, most were directly related to pregnancy such as unplanned pregnancy, gestational diabetes, or various gestational timepoints (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. S9). The three conditions that caused the biggest decrease in normalized Spearman correlation when removed from MOTOR representations were illness, unplanned pregnancy, and gestational diabetes. All three condition dropouts also caused a significant decrease in generative performance for CLMBR representations (Supplementary Fig. S9, Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly, many of the top features in Fig. 4c and e (such as glucose presence in the urine, ketone presence in the urine, and glycosuria) are highly related to gestational diabetes [24]. These results suggest that gestational diabetes has a proteomic signature in pregnant women. There were 115 individual proteins that had a normalized Spearman correlation <1, indicating a drop in generative performance, in the gestational diabetes dropout model (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Table S3). Some of these proteins have known associations with gestational diabetes such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor [25], glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR) [26], insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2 (IGFBP-2) [27], and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (IGFBP-5) [28] (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table S3). However, other proteins, including most of the top 10 ranked by largest decrease in normalized Spearman correlation, are pro-inflammatory such as tumor necrosis factor-beta (TNF-b), Fc gamma receptor I (FCGR1), and CSF1. This is consistent with the known role of chronic inflammation in gestational diabetes pathogenesis [29–31]. Overall, post hoc analysis of our FM-generated proteomics profiles identified new associations that would not normally be evident when analyzing individual feature–biological outcome relationship pairs.

Generated proteomics of patients with pregnancy complicated by fetal heart rate anomaly identifies differences in cardiac-related protein expression levels

We used our model pipeline with MOTOR representations to generate expressions for 177 significant proteins in 64 080 patients who had a recorded delivery at Stanford (Supplementary Fig. S10a). Patients were stratified based on “labor and delivery complicated by fetal heart rate anomaly,” a prevalent condition in our cohort (Supplementary Fig. S10b). Among the top 10 proteins with the largest differences in expression, all but SIGLEC6 (linked to preeclampsia [16]) were directly associated with cardiac development or disease [32–38]. These findings suggest new research directions for pregnancies complicated by fetal heart rate anomalies.

Discussion

We demonstrate the first proof-of-concept using FM representations of EHR data to generate proteomics, showing that clinical information can generate protein expressions in pregnant patients. Using two state-of-the-art FM models, we generated 206 blood protein expressions in pregnant patients. Significant proteins were linked to vascular development, while nonsignificant ones were enriched in metabolic pathways. The rapid metabolic changes during pregnancy likely make it challenging to predict using the sporadic nature of EHR data.

The comparison between MOTOR and CLMBR demonstrates that the choice of FM is important when generating proteomics from EHR data. Our study used MOTOR and CLMBR because [1] they are trained specifically for EHR clinical data, a much more detailed and information-rich clinical modality compared to other clinical datatypes such as claims data [39, 40], and [2] were trained using much larger EHR datasets (~3 million patients) compared to other currently available EHR FMs [41–43]. MOTOR performed significantly better for nearly all overlapping significant proteins. A combination of several differences between MOTOR and CLMBR may explain this result. Time-to-event models like MOTOR have the additional advantage of accounting for event censoring in the input data, a very common problem in highly sparse datasets like EHR data. In addition, MOTOR was trained on 8192 self-supervised prediction tasks compared to CLMBR’s next-diagnosis code prediction task [11, 12]. These differences suggest that MOTOR’s time-oriented pretraining objective more robustly creates representations for proteomics generation.

Drawing novel associations between specific clinical and biological factors that can spark new avenues of research is an opportunity-rich aspect of using clinical data to generate biological results. Immune-, urine-, and glucose-related features were most correlated with protein expression and/or generative power of the model. The relationship between immunology and pregnancy has been well established [44] and is an exciting area of research. Many of our significant proteins, including our top significant protein sST2, are immune proteins. sST2 is a decoy receptor for IL-33 that prevents IL-33 signaling [45, 46]. Multiple studies have demonstrated a strong link between IL-33 and lung injury, especially during the neonatal period in mice [47]. Conversely, others have demonstrated the protective effects of sST2 in lung inflammation conditions such as allergy in mice [46]. Future studies using generated proteomics in maternal–baby pairs may provide new insight into the human pathophysiology of IL-33 or other immune-mediated developmental diseases.

Drugs were the least informative EHR category for generating proteomics, likely due to the “noisiness” of drug prescription records. The Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) drug table records prescriptions, not the actual administered dosages or durations, and different doses of the same drug are treated as distinct entries. These limitations may introduce confusion, reducing the model’s performance. As OMOP standardization improves, these issues may be resolved.

One limitation of this study is the specific patient cohort used. We selected this cohort to use as our proof-of-concept cohort because pregnancy may be a valuable use case for a noninvasive method of generating proteomics profiles. However, this likely biases the proteins we were able to generate, and the resulting biological analysis, to pregnancy-related proteins. Thus, our current work is limited to pregnant patients. Future validation studies with external cohorts are needed to assess generalizability to other patient cohorts and populations. Second, the incorporation of lab value units will likely improve performance. A given lab measurement in EHR may have multiple units associated with its values. While MOTOR and CLMBR utilize lab values, they currently do not incorporate units when generating representations. A future model where this information is incorporated to properly scale lab values within each measurement type will likely improve generative performance.

Generating biological data such as blood proteomics requires significant resources. Instantly generating such data from existing EHRs offers a promising opportunity. With widespread EHR adoption, using these records to generate proteomics could provide the biological data of millions of patients, opening doors to new clinical and biological questions and enabling the discovery of novel associations between clinical features and proteins.

Methods

Sample collection

Samples for proteomics were collected as part of a previously published study [13] conducted at Stanford’s Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (Stanford, CA, USA). In brief, the study included healthy pregnant women between 22 and 40 years old who were in their second or third trimester with a body mass index below 40, as determined by their doctors using menstrual and ultrasound information. Women with conditions affecting the immune system or those taking related medications were not eligible. Participants were monitored up to childbirth, giving one to three blood samples during their third trimester. Plasma was sent for proteomics analysis (SomaLogic Inc., Boulder, CO). A total of 1305 proteins passed SomaLogic’s quality control and were used for the study. EHRs from Stanford’s Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (STARR-OMOP) database for each participant were collected. Specifically, the person (containing basic demographic information such as age, sex, ethnicity), condition occurrence (containing diagnosis codes), drug exposure (containing prescribed drug codes), measurements (containing hospital laboratory measurements collected), and procedure occurrence (containing clinical procedures undergone) tables were queried.

Generation of electronic health record latent representations using foundation models

Pretrained FMs for MOTOR [11] and CLMBR [12] were obtained from Stanford School of Medicine’s private server. STARR-OMOP EHR data were preprocessed through Framework for Electronic Medical Records (v0.1.16), which allows the specification of a cutoff timepoint [11, 12, 48]. The cutoff timepoint for each sample was set to the date of sample collection for proteomics so that the EHR representations would only encompass information up to and including the day of sample collection, thereby simulating the information that would be available in real-world scenarios at the time of generation. The final preprocessed result organizes all EHR events for a given patient as events (visit days) with each code timestamped to the day ordered in chronological order along with any associated metadata (i.e. type of code, associated numerical values). The preprocessed data were fed through the pretrained FMs to generate 768-element vector representations of EHR data.

Prediction of proteomics using foundation model latent representations of electronic health record data

The latent representations of EHR data created by MOTOR and CLMBR were used as input to a fully connected neural network prediction head. The network was composed of two linear layers (768 nodes and 32 nodes, respectively) with a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function after the first layer. The model was trained for 1000 epochs with Adam optimizer and a learning rate of 0.001. The mean squared error (MSE) loss was used to train and evaluate model performance. The final output was a single number, the generated value of the protein of interest. Individual models were trained for each of the 1305 proteins. To ensure model stability, especially given our smaller sample size, bootstrapping was performed by repeating the train/validation/test split 10 times to maximize the number of times each sample is in the test set. For each bootstrap iteration, the best model was defined by the model with the lowest MSE on the validation set, and expression values were generated using this model. Generated protein expression values for samples in the test set were collected, and the final generated protein expression value for each sample was the average of all generated values (Supplementary Table S4). The model was implemented using PyTorch’s regression module. Evaluation of predictions was performed by calculating Spearman correlations between actual and generated protein expression values. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used to correct for multiple hypothesis testing, and an adjusted P-value threshold of .05 was used for statistical significance.

Electronic health record dropout feature importance analysis

To investigate the relative importance of each EHR category on generative power, six different representations were generated for each FM. The first representation (full representation) utilized all five categories of EHR data (conditions, measurements, procedures, drugs, demographics). The other five representations each had one of the categories dropped. For the condition dropout analysis, 527 models were generated in addition to the full model (one for each of the 527 unique condition codes). The generative performance of each dropout representation model was analyzed relative to the full representation model for proteins that were significantly generated in the full representation model (177 for MOTOR, 87 for CLMBR) by dividing the Spearman correlation for a given protein in the dropout representation model by the Spearman correlation for the protein in the full representation model. A paired Wilcoxon test was used with multiple hypothesis correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to assess the significance of the differences.

Generation of proteins on additional Stanford pregnant patients

We identified 64 080 patients with at least one delivery code (447 codes, see Supplementary Table S6). EHR data from each patient, from their earliest record to their first delivery, were processed through our proteomics generation pipeline using MOTOR representations to generate expression levels for 177 significant proteins (from Fig. 2c). Diagnosis codes present in our cohort were ranked by prevalence to identify the most specific, high-prevalence disease for patient stratification and detailed analysis.

Correlation matrix calculations

The correlation matrix for the proteomics data (Fig. 3a) was created by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient for each protein–protein pair. K-means clustering (k = 3) followed by dimensionality reduction was performed using tSNE (perplexity = 30, learning rate = 200) for visualization. The cluster number was determined by calculating the within-cluster sum of squares and plotting an elbow plot. Piecewise regression was calculated using the within-cluster-sum of squares to identify the optimal cluster number. To calculate the correlation matrix for features and protein expression (Fig. 4a), the feature count matrix was first generated by counting the number of times each EHR feature code occurred for each sample until the cutoff timepoint. Only the features that had occurred at least once in one sample were kept for analysis, resulting in 1799 features. The feature count matrix was combined with the protein expression matrix to calculate the correlation matrix as above. Dimensionality reduction was performed using tSNE (perplexity = 30, learning rate = 200) for visualization.

Pathway analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using GO pathways through GSEApy (v1.1.2) [49]. Protein names were converted to Entrez gene symbols. The list of all proteins theoretically detectable by SomaLogic v4 was used as the background list of proteins for reference. Adjusted P-values and combined score (a ranking metric that adjusts for varying lengths of gene sets in each GO developed by Enrichr [50]) are reported. The full results for each cluster in Fig. 3 are shown in Supplementary Table S5.

Key Points

Proteomics expression values can be generated from foundation model representations of electronic health records in pregnant patients.

Developmental pathway proteins are best generated.

Clinical conditions are the most useful category of electronic health record data when generating proteomics.

Feature importance analysis of the model reveals established and novel associations between clinical features and protein expression, such as a proteomics signature of gestational diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Ethan Steinberg and Dr Nigam Shah at Stanford for their work on MOTOR and CLMBR. We also thank the patients who donated blood samples for proteomics analysis. The graphical abstract and portions of Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S3 were created using BioRender.com.

Contributor Information

David Seong, Immunology Program, Stanford University School of Medicine, 240 Pasteur Drive, Palo Alto CA, 94304, United States; Medical Scientist Training Program, Stanford University School of Medicine, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Samson Mataraso, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Camilo Espinosa, Immunology Program, Stanford University School of Medicine, 240 Pasteur Drive, Palo Alto CA, 94304, United States; Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Eloise Berson, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

S Momsen Reincke, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Lei Xue, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Chloe Kashiwagi, Immunology Program, Stanford University School of Medicine, 240 Pasteur Drive, Palo Alto CA, 94304, United States; Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Yeasul Kim, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Chi-Hung Shu, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Philip Chung, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Marc Ghanem, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Feng Xie, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Ronald J Wong, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Martin S Angst, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Brice Gaudilliere, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Gary M Shaw, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

David K Stevenson, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Nima Aghaeepour, Immunology Program, Stanford University School of Medicine, 240 Pasteur Drive, Palo Alto CA, 94304, United States; Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford CA, 94305, United States; Department of Biomedical Data Science, Stanford University, 1265 Welch Road, Stanford CA, 94305, United States.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R35GM138353], Burroughs Wellcome Fund [1019816], the March of Dimes, the Alfred E. Mann Foundation, the Hess Research Fund, the Roberts Foundation Research Fund, and the Chambers–Okamura Prematurity Fund.

Data availability

All codes are available at https://github.com/dhs37929/BIB_proteomics_generation The omics data for the onset of labor cohort are available through the original study [13]. The Stanford EHR data, model weights, or any other derivations from the EHR data for the onset of the labor cohort cannot be shared publicly due to HIPAA restrictions.

References

- 1. Wolf J, Rasmussen DK, Sun YJ. et al. Liquid-biopsy proteomics combined with AI identifies cellular drivers of eye aging and disease in vivo. Cell 2023;186:4868–4884.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Espinosa CA, Khan W, Khanam R. et al. Multiomic signals associated with maternal epidemiological factors contributing to preterm birth in low- and middle-income countries. Sci Adv 2023;9:eade7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buergel T, Steinfeldt J, Ruyoga G. et al. Metabolomic profiles predict individual multidisease outcomes. Nat Med 2022;28:2309–20. 10.1038/s41591-022-01980-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carrasco-Zanini J, Pietzner M, Davitte J. et al. Proteomic signatures improve risk prediction for common and rare diseases. Nat Med 2024;30:2489–98. 10.1038/s41591-024-03142-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carrasco-Zanini J, Pietzner M, Koprulu M. et al. Proteomic prediction of diverse incident diseases: a machine learning-guided biomarker discovery study using data from a prospective cohort study. Lancet Digit Health 2024;6:e470–9. 10.1016/S2589-7500(24)00087-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu Y, Ritchie SC, Liang Y. et al. An atlas of genetic scores to predict multi-omic traits. Nature 2023;616:123–31. 10.1038/s41586-023-05844-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moor M, Banerjee O, Abad ZSH. et al. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature 2023;616:259–65. 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clusmann J, Kolbinger FR, Muti HS. et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Commun Med (Lond) 2023;3:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alsentzer, E, Murphy J, Boag W., et al. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop (eds. Rumshisky A, Roberts K, Bethard S & Naumann T.) 72–8 ( Association for Computational Linguistics, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, 2019). 10.18653/v1/W19-1909, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Trends in Hospital and Physician Adoption of Electronic Health Records | HealthIT.gov. https://www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/national-trends-hospital-and-physician-adoption-electronic-health-records

- 11. Steinberg E, Fries J, Xu Y., et al. MOTOR: a time-to-event foundation model for structured medical records. Preprint at 10.48550/arXiv.2301.03150 (2023), [DOI]

- 12. Steinberg E, Jung K, Fries JA. et al. Language models are an effective representation learning technique for electronic health record data. J Biomed Inform 2021;113:103637. 10.1016/j.jbi.2020.103637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stelzer IA, Ghaemi MS, Han X. et al. Integrated trajectories of the maternal metabolome, proteome, and immunome predict labor onset. Sci Transl Med 2021;13:eabd9898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sasmaya PH, Khalid AF, Anggraeni D. et al. Differences in maternal soluble ST2 levels in the third trimester of normal pregnancy vers us preeclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X 2021;13:100140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Granne I, Southcombe JH, Snider JV. et al. ST2 and IL-33 in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. PLoS One 2011;6:e24463. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rumer KK, Uyenishi J, Hoffman MC. et al. Siglec-6 expression is increased in placentas from pregnancies complicated by preterm preeclampsia. Reprod Sci 2013;20:646–53. 10.1177/1933719112461185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schmidt EN, Lamprinaki D, McCord KA. et al. Siglec-6 mediates the uptake of extracellular vesicles through a noncanonical glycolipid binding pocket. Nat Commun 2023;14:2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh H, Aplin JD. Endometrial apical glycoproteomic analysis reveals roles for cadherin 6, desmoglein-2 and plexin b2 in epithelial integrity. Mol Hum Reprod 2015;21:81–94. 10.1093/molehr/gau087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Babay Z, al-Wakeel J, Addar M. et al. Serum cystatin C in pregnant women: reference values, reliable and superior diagnostic accuracy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2005;32:175–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee H. Cystatin C in pregnant women is not a simple kidney filtration marker. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2018;37:313–4. 10.23876/j.krcp.18.0146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vogel WF, Aszódi A, Alves F. et al. Discoidin domain receptor 1 tyrosine kinase has an essential role in mammary gland development. Mol Cell Biol 2001;21:2906–17. 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2906-2917.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Florio P, Cobellis L, Luisi S. et al. Changes in inhibins and activin secretion in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001;180:123–30. 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00503-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Florio P, Ciarmela P, Luisi S. et al. Pre-eclampsia with fetal growth restriction: placental and serum activin a and inhibin a levels. Gynecol Endocrinol 2002;16:365–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gribble RK, Meier PR, Berg RL. The value of urine screening for glucose at each prenatal visit. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:405–10. 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00198-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moosaie F, Mohammadi S, Saghazadeh A. et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2023;18:e0268816. 10.1371/journal.pone.0268816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anghebem-Oliveira MI, Webber S, Alberton D. et al. The GCKR gene polymorphism rs780094 is a risk factor for gestational diabetes in a Brazilian population. J Clin Lab Anal 2017;31:e22035. 10.1002/jcla.22035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boughanem H, Yubero-Serrano EM, López-Miranda J. et al. Potential role of insulin growth-factor-binding protein 2 as therapeutic target for obesity-related insulin resistance. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:1133. 10.3390/ijms22031133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhao D, Shen L, Wei Y. et al. Identification of candidate biomarkers for the prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus in the early stages of pregnancy using iTRAQ quantitative proteomics. Proteomics Clin Appl 2017;11. 10.1002/prca.201600152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aggarwal BB, Gupta SC, Kim JH. Historical perspectives on tumor necrosis factor and its superfamily: 25 years later, a golden journey. Blood 2012;119:651–65. 10.1182/blood-2011-04-325225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bournazos S, Wang TT, Ravetch JV. The role and function of Fcγ receptors on myeloid cells. Microbiol Spectr 2016;4. 10.1128/microbiolspec.MCHD-0045-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin W, Xu D, Austin CD. et al. Function of CSF1 and IL34 in macrophage homeostasis, inflammation, and cancer. Front Immunol 2019;10:2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schroen B, Heymans S, Sharma U. et al. Thrombospondin-2 is essential for myocardial matrix integrity: increased expression identifies failure-prone cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 2004;95:515–22. 10.1161/01.RES.0000141019.20332.3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robson A, Makova SZ, Barish S. et al. Histone H2B monoubiquitination regulates heart development via epigenetic control of cilia motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:14049–54. 10.1073/pnas.1808341116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roh JD, Hobson R, Chaudhari V. et al. Activin type II receptor signaling in cardiac aging and heart failure. Sci Transl Med 2019;11:eaau8680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E: from cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016;94:739–46. 10.1007/s00109-016-1427-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown DA, Breit SN, Buring J. et al. Concentration in plasma of macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 and risk of cardiovascular events in women: a nested case-control study. Lancet 2002;359:2159–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kojima Y, Ono K, Inoue K. et al. Progranulin expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaque. Atherosclerosis 2009;206:102–8. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ng A, Wong M, Viviano B. et al. Loss of glypican-3 function causes growth factor-dependent defects in cardiac and coronary vascular development. Dev Biol 2009;335:208–15. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boiarsky R, Lim J, Sai A, Dixit N, Sontag D. Deep Contextual Clinical Prediction with Reverse Distillation. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2021;35:249–258. 10.1609/aaai.v35i1.16099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Prakash PKS, Chilukuri S, Ranade N. et al. RareBERT: transformer architecture for rare disease patient identification using administrative claims. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2021;35:453–60. 10.1609/aaai.v35i1.16122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miotto R, Li L, Kidd BA. et al. Deep patient: an unsupervised representation to predict the future of patients from the electronic health records. Sci Rep 2016;6:26094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang J, Kowsari K, Harrison JH. et al. Patient2Vec: a personalized interpretable deep representation of the longitudinal electronic health record. IEEE Access 2018;6:65333–46. 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2875677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li Y, Rao S, Solares JRA. et al. BEHRT: transformer for electronic health records. Sci Rep 2020;10:7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mor G, Aldo P, Alvero AB. The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 2017;17:469–82. 10.1038/nri.2017.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ. et al. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest 2007;117:1538–49. 10.1172/JCI30634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hayakawa H, Hayakawa M, Kume A. et al. Soluble ST2 blocks interleukin-33 signaling in allergic airway inflammation. J Biol Chem 2007;282:26369–80. 10.1074/jbc.M704916200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chang J, Xia Y-F, Zhang M-Z. et al. IL-33 Signaling in lung injury. Transl Perioper Pain Med 2016;1:24–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wornow M, Xu Y, Thapa R. et al. The shaky foundations of large language models and foundation models for electronic health records. npj Digit Med 2023;6:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fang Z, Liu X, Peltz G. GSEApy: a comprehensive package for performing gene set enrichment analysis in Python. Bioinformatics 2023;39:btac757. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y. et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics 2013;14:128. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All codes are available at https://github.com/dhs37929/BIB_proteomics_generation The omics data for the onset of labor cohort are available through the original study [13]. The Stanford EHR data, model weights, or any other derivations from the EHR data for the onset of the labor cohort cannot be shared publicly due to HIPAA restrictions.