Abstract

Objective

Hematuria is one of the most common conditions in children, and increase the risk of chronic kidney disease. Persistent hematuria may be the earliest manifestation of type IV collagen-related nephropathy. Early diagnosis is essential for optimized therapy. Due to the invasive nature of kidney biopsy and the high cost of whole exome sequencing, its application in the diagnosis of isolated hematuria is rare. Hence, we performed noninvasive and convenient genetic testing approaches for type IV collagen-related nephropathy.

Methods

We used noninvasive oral mucosa sampling as an alternative method for DNA isolation for genetic testing and designed a panel targeting three type IV collagen nephropathy-related genes in children with hematuria. Children with persistent hematuria unaccompanied by clinically significant proteinuria or renal insufficiency who underwent genetic testing using a hematuria panel were enrolled.

Results

Thirty-seven of 112 (33.0%) patients were found to have a genetic variant in COL4A3/A4/A5. Pathogenic/likely pathogenic COL4A3/A4/A5 variants were identified in 17 of the 112 patients analyzed (15.2%), which were considered to explain their hematuria manifestations. In addition, variants of unknown significance (VUSs) were found in 17.8% (20/112) of patients. Furthermore, we observed a much greater COL4A3/A4/A5 variant detection rate in patients with a positive family history or more severe hematuria (RBC ≥ 20/HP) or with coexisting microalbuminuria (59.2% vs. 12.7%, p < 0.001; 64.0% vs. 24.1%, p < 0.001; 66.7% vs. 30.1%, p = 0.025).

Conclusions

We present the high prevalence of variants in COL4A genes in a multicenter pediatric cohort with hematuria, which requires close monitoring and long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Hematuria, type IV collagen-related nephropathy, genetic testing, pediatric

Introduction

Hematuria is common in children, affecting 0.5-4.1% of the school-age population [1–5], which increases the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [6,7]. Urinalysis is routinely conducted in school-age children for the early detection of renal asymptomatic disorders. But current diagnostic methods, such as invasive renal biopsy and costly genetic testing, are often deferred in isolated hematuria children, leading to a lack of early definitive diagnosis and loss to follow-up.

Type IV collagen-related nephropathy, caused by COL4A3-COL4A5 gene variants, is a common inherited kidney diseases in children [8,9], often presenting with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. Early diagnosis is essential for optimized therapy, particularly as RAAS blockade can delay kidney failure onset in Alport syndrome [10,11]. Guideline recommend genetic testing for type IV collagen-related nephropathy in patients with persistent hematuria [12]. However, due to insurance policies and economic considerations, limited research has explored genetic screening in children with isolated microscopic hematuria. To improve early diagnosis and timely intervention, we propose a noninvasive genetic testing strategy for these patients.

Methods

Patient cohort

Children with persistent microhaematuria unaccompanied by clinically significant proteinuria or renal insufficiency who underwent genetic testing using a designed panel at the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, Wuhan Children’s Hospital, and Women and Children’s Hospital of Xiamen University from October 2021 to August 2023 were enrolled. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Children’s Hospital of Fudan University (approval No. 2020-525). Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their parents.

The inclusion criteria for patients who underwent hematuria panel sequencing were as follows: 1) had glomerular hematuria that persisted for more than 3 months; 2) did not have clinically significant proteinuria, defined as a urinary albumin to creatinine ratio of more than 0.3 or 24-h urinary protein excretion of more than 300 mg; 3) had normal renal function; and 4) willingness to participate and signed informed consent. Patients who 1) had a known underlying cause of hematuria, such as glomerulonephritis, cystic disease, hypercalciuria, or nephrolithiasis; 2) had concomitant urinary tract infection; or 3) had clinically significant proteinuria (a ratio of urinary albumin to creatinine of more than 0.3 mg/mg or 24-h urinary protein excretion of more than 300 mg) were excluded. The diagnostic criterion for hematuria was a red blood cell count ≥3/HPF in the centrifuged sediment of morning urine. The hematuria grade was classified into two groups according to the following distribution: <20 and ≥20 RBCs/HPF. Clinical, laboratory and pathologic data were collected from medical records.

Noninvasive type IV collagen nephropathy-related genetic testing approaches

Noninvasive oral mucosa sampling for DNA extraction

Genomic DNA specimens were isolated from oral mucosa sampling using standard procedures.

Sample Collection Use noninvasive buccal swab sampler to collect buccal mucosa cells: 1) Before sampling, instruct subject to rinse mouth thoroughly to remove food particles; 2) The swab head was gently rubbed against the buccal mucosa 30 times on each side, with a force sufficient to cause slight elevation of the cheek.

DNA Extraction Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy 96 Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA Quantification and Quality Control 1) Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to analyze the degree of DNA degradation and the presence of RNA or protein contamination; 2) The Qubit 3.0 instrument was used to quantify the concentration of extracted DNA. DNA samples with a concentration ≥ 5 ng/µL and a total amount ≥ 0.2 µg were used for subsequent library construction. DNA samples were stored at -20 °C.

Genetic panel design, sequencing and analysis

A custom gene panel was established for the analysis of three Alport syndrome (AS) genes (COL4A3/A4/A5). Amplification primers for the protein coding regions and adjacent intronic sequences (± 20 bp) were designed by the manufacturer using proprietary tools for the genes COL4A3 (NM_000091.4), COL4A4 (NM_000092.4), and COL4A5 (NM_033380.2).

Genetic sequencing was performed by the Medical Laboratory of ZhongKe Co., Ltd. (Nantong, CHN) using a custom hematuria panel consisting of three Alport syndrome-related genes (COL4A3/A4/A5). The mean coverage was ≥500× with ≥99% target coverage. The pathogenicity of the genetic results was assigned according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines [13,14].

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), with percentages for categorical variables. T tests and chi-square tests were used to compare the differences between variable groups according to genetic results. p ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between October 2021 and August 2023, a total of 112 children (from 110 families) were subjected to genetic sequencing using the custom hematuria panel, which consisted of 35 male and 77 female subjects. The mean age at genetic testing was 7.4 ± 3.2 years. A total of 43.8% of the patients in this cohort had a familial history of renal disease, 98% of whom were first-degree relatives. A total of 103 patients presented with isolated microscopic hematuria, and 9 presented with combined microscopic hematuria and microalbuminuria. All children had normal blood pressure. None of them had extrarenal manifestations at the time of genetic testing. The demographic and clinical characteristics of 112 children with hematuria are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 112 children with hematuria and comparison between COL4A3/A4/A5 variants status.

| Characteristics | All (n = 112) |

COL4A3/A4/A5 variants status |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic variants detected (n = 37) |

No variants detected (n = 75) |

|||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.459 | |||

| Male | 35 (31.2%) | 10 (28.6%) | 25 (71.4%) | |

| Female | 77 (68.8%) | 27 (35.1%) | 50 (64.9%) | |

| Age at first presentation to nephrology (years) | 0.670 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 5.4 ± 2.9 | 5.2 ± 2.7 | 5.5 ± 3.0 | |

| Age at genetic sequencing(years) | 0.925 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 7.4 ± 3.2 | 7.3 ± 3.2 | 7.4 ± 3.3 | |

| Family history of kidney disease (n, %) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 49 (43.8%) | 29 (59.2%) | 20 (40.8%) | |

| No | 63 (56.2%) | 8(12.7%) | 55 (87.3%) | |

| Renal manifestation (n, %) | 0.025 | |||

| Isolated microscopic hematuria | 103 (92.0%) | 31 (30.1%) | 72 (69.9%) | |

| Microscopic hematuria and Microalbuminuria | 9 (8%) | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Degree of hematuria | <0.001 | |||

| <20/HPF | 87 (77.7%) | 21 (24.1%) | 66 (75.9%) | |

| ≥20/HPF | 25 (22.3%) | 16 (64.0%) | 9 (36.0%) | |

SD: standard deviation; HPF: high-powered field. Genetic variants detected, patients with COL4A3/A4/A5 variants detected (including pathogenic variants, likely pathogenic variants, or variant of uncertain significance); no variants detected, patients with no COL4A3/A4/A5 variants detected.

Genetic findings

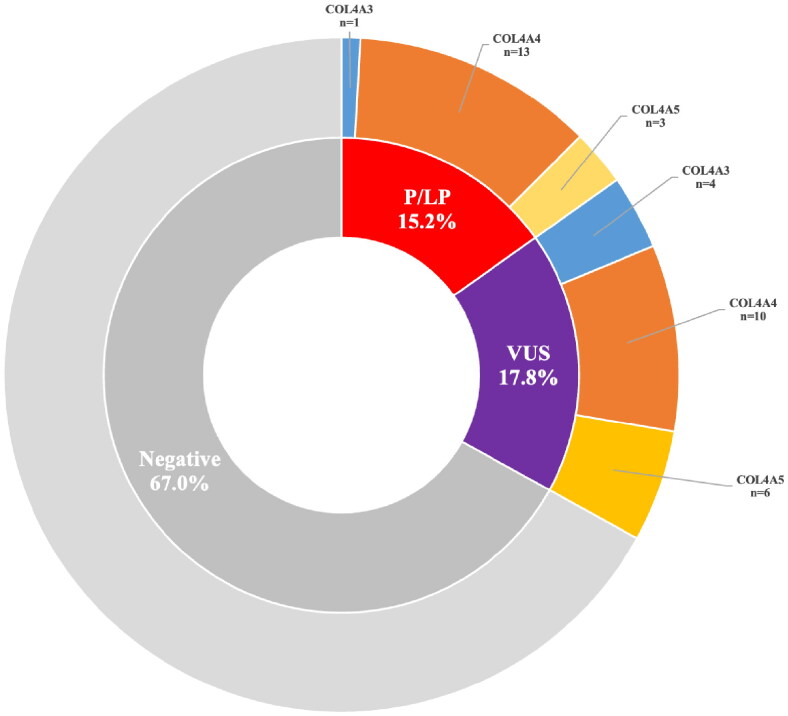

Among the 112 patients tested, 37 (33.0%) were found to carry genetic variants. Of these, 17 had heterozygous pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) variants, while 20 presented variants of unknown significance (VUS). A definitive genetic diagnosis was made for 17 patients (15.2%) who had P/LP variants in one of three Alport syndrome-related genes: COL4A3 (1 case), COL4A4 (13 cases), and COL4A5 (3 cases) (Figure 1). The pathogenic/likely pathogenic mutations were missense in 3 patients (17.6%) and non-missense in the remaining 14 patients (82.4%) from twelve families: 6 with a splice site mutation, 4 with a premature stop codon mutation, and 4 with a frameshift (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Results of COL4A3/A4/A5 sequencing in 112 children with hematuria. Negative, with no variants detected; P/LP, pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Table 2.

Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in COL4A3/A4/A5 genes identified in children with hematuria.

| Patient No. | Gender | Age (years) | Family history | Renal phenotype | Affected gene | Nucleotide change | Protein change | Zygosity (segregation) | ACMG criterion | Variant Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F03 | Female | 11.0 | F | MH | COL4A4 | c.3397 + 1G > C | – | Het(p,het;m,wt) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| F05 | Female | 7.5 | M | MH, MA | COL4A4 | c.1921C > T | p. Arg641* | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| F10 | Female | 9.6 | M/GM | MH | COL4A4 | c.2244delC | p. Ser749fs | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| F20 | Male | 5.6 | N | MH | COL4A4 | c.817-1G > A | – | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| F45 | Female | 11.0 | N | MH | COL4A4 | c.1696 + 1G > T | – | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| F53 | Female | 5.5 | F | MH | COL4A3 | c.1918G > A | p. Gly640Arg | Het(p,het;m,wt) | PM3 +PS4 + PM2 +PP3 | LP |

| F54 | Female | 10.1 | M | MH | COL4A4 | c.3506-13_3528del36 | p. Gly1169fs | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| #F58 | Male | 5.8 | F/B | MH | COL4A4 | c.1178T > A | p. Leu393* | Het(p,het;m,wt) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| #F59 | Male | 8.0 | F/B | MH | COL4A4 | c.1178T > A | p. Leu393* | Het(p,het;m,wt) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| *F62 | Female | 6.2 | M/B/GM | MH/MA | COL4A5 | c.2510-2A > G | – | Het (p,wt;m,het) | PVS1 + PM2 + PP1 | P |

| *F63 | Male | 3.8 | M/S/GM | MH | COL4A5 | c.2510-2A > G | – | Hem(p,wt;m,het) | PVS1 + PM2 + PP1 | P |

| F76 | Female | 8.6 | N | MH, MA | COL4A5 | c.1378G > C | p. Gly460Arg | Het(p,wt;m,wt) | PS4 + PM2 + PM6 + PP3 | LP |

| F81 | Male | 12.9 | M | MH, MA | COL4A4 | c.2752G > A | p. Gly918Arg | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PS4 +PM2 +PM3 + PP3 | LP |

| W03 | Female | 3.8 | F | MH | COL4A4 | c.602G > A | p. Trp201* | Het(p,het;m,wt) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| W06 | Female | 5.8 | M | MH | COL4A4 | c.1099 + 1delG | – | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| W10 | Female | 13 | A | MH | COL4A4 | c.3506-13_3528del36 | p. Gly1169fs | Het (p,na;m,na) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

| X08 | Male | 4.8 | F | MH | COL4A4 | c.1505delC | p. Pro502fs | Het(p,het;m,wt) | PVS1 + PM2 | LP |

# Patient F58 and F59 were siblings. * F62 and F63 were siblings.

F: father; M: mother; GM: grandmother; B: brother; S: sister; A: aunt; N: no; MH: microscopic hematuria; MA: microalbuminuria; Het: heterozygous; wt: wild-type; na: not avalible; p: paternal; m: maternal; LP: likely pathogenic; P: pathogenic.

Segregation analysis was performed for all of the patients with a P/LP genetic variant. The variants in COL4A3/A4 showed that the segregations were consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance because one of the affected parents was heterozygous for the same variants, except for the variants c.817-1G > A and c.1696 + 1G > T in COL4A4. Patient F20 had a heterozygous, likely pathogenic variant in COL4A4 (c.817-1G > A) inherited from his healthy father and F45 had a heterozygous, likely pathogenic variant in COL4A4 (c.1696 + 1G > T) inherited from her healthy mother, which did not show consistent co-occurrence with the renal phenotype. Patients F20 and F45 had likely pathogenic variants in COL4A4 (c.817-1G > A and c.1696 + 1G > T, respectively) inherited from their healthy parents, which did not show consistent co-occurrence with the renal phenotype in their families. We speculate that these variants may be associated with incomplete penetrant hematuria in their families. Patient F76, who presented with microscopic hematuria and microalbuminuria, was reported to have a heterozygous, de novo, likely pathogenic variant in COL4A5 (c.1378G > A, p. Gly460Arg).

Variants of unknown significance (VUS) were found in 17.8% (20/112) of patients without a disease-causing variant: COL4A3 (4 cases), COL4A4 (10 cases), and COL4A5 (6 cases) (Table 3, Figure 1).

Table 3.

Variants of uncertain significance in COL4A3/A4/A5 genes identified in children with hematuria.

| Patient No. |

Gender | Age (years) |

Family history |

Renal phenotype |

Affected gene | Nucleotide change | Protein change | Zygosity (segregation) | ACMG criterion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F02 | Male | 3.4 | M | MH | COL4A5 | c.2104G > T | p.Gly702Cys | Hem(p,wt;m,het) | PM1 + PM2 + PP3 |

| F07 | Female | 10.7 | F | MH/MA | COL4A3 | c.4234G > C | p.Gly1412Arg | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM2 + PP3 |

| F09 | Female | 8.6 | F | MH | COL4A4 | c.3443G > T | p.Gly1148Val | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM2 + PP3 |

| F15 | Female | 11.2 | M | MH | COL4A5 | c.1515A > C | p.Pro505Pro | Het(p,wt;m,wt) | PM2 + PM6 |

| F16 | Female | 7.1 | M | MH | COL4A4 | c.870G > A | p.Lys290Lys | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PS3 + PM2 |

| F17 | Male | 3.8 | N | MH | COL4A4 | c.4715C > T | p.Pro1572Leu | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM3 + PP3 |

| F21 | Female | 9.7 | N | MH | COL4A4 | c.3134G > A | p.Gly1045Glu | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM2 +PP3 |

| F24 | Male | 4.4 | F/GM | MH | COL4A4 | c.2671G > C | p.Gly891Arg | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM2 + PP3 |

| F26 | Female | 11.9 | F | MH | COL4A5 | c.4910C > T | p.Thr1637Ile | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM2 + PP3 |

| F27 | Female | 12.7 | M/GM | MH | COL4A5 | c.2879T > G | p.Leu960Arg | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PM2 |

| F34 | Female | 4.1 | N | MH | COL4A5 | c.4184C > A | p.Pro1395His | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PM2 |

| F35 | Female | 4.4 | N | MH/MA | COL4A4 | c.4421C > T | p.Thr1474Met | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM3 |

| F44 | Male | 3.8 | M/GM | MH | COL4A4 | c.197C > T | p.Pro66Leu | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PM2 |

| F66 | Male | 4.9 | M | MH | COL4A3 | c.3682G > T | p.Gly1228Cys | Het (p,wt;m,het) | PM2 + PP3 |

| F77 | Female | 7.4 | F | MH | COL4A3 | c.209G > T | p.Gly70Val | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PP3 |

| W14 | Female | 5.3 | M | MH | COL4A4 | c.1415G > A | p.Gly472Asp | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PM2 + PP3 |

| W15 | Male | 8.6 | F | MH | COL4A4 | c.1031G > C | p.Gly344Ala | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM2 + PP3 |

| W16 | Female | 10.5 | M | MH | COL4A5 | c.262C > T | p.Pro88Ser | Het(p,wt;m,het) | PP3 |

| X05 | Female | 5.5 | F/GM | MH | COL4A4 | c.1805G > A | p.Gly602Glu | Het (p,het;m,wt) | PM2 + PP3 |

| X09 | Female | 6.1 | M | MH | COL4A3 | c.1823G > T | p.Gly608Val | Het (p,wt;m,het) | PM2 + PP3 |

F: father; M: mother; GM: grandmother; N: no; MH: microscopic hematuria; MA: microalbuminuria; Het: heterozygous; Hem: hemizygous; wt: wild-type; p: paternal; m: maternal.

Subgroup analysis revealed that patients with a positive family history or more severe hematuria (RBC ≥ 20/HP) had a greater prevalence of identified COL4A3/A4/A5 variants (59.2% vs. 12.7%, p < 0.001; 64.0% vs. 24.1%, p < 0.001) (Table 1). Patients with coexisting microalbuminuria were more likely to have a COL4A3/A4/A5 variant than were those without microalbuminuria (66.7% vs. 30.1%, p = 0.025).

Among those with severe hematuria and a family history, the genetic variant rate of COL4A3/A4/A5 increased to 85.7% (12/14). Moreover, in those with severe hematuria, a positive family history and microalbuminuria, the genetic variant detection rate increased to 100% (4/4).

Discussion

Hematuria during early childhood is a common clinical feature of glomerular disease and can indicate the presence of underlying genetic kidney disease. The prognosis varies based on the nature of the molecular change. Genomic sequencing is relatively noninvasive compared to kidney biopsy, a particularly important consideration in the pediatric population as a first-tier approach for diagnosis [15,16], especially those with a family history of hematuria or kidney function impairment [12,17–19]. Due to the invasive nature of kidney biopsy and the high cost of whole-exome sequencing, its application in the clinical diagnosis of children with isolated microscopic hematuria is limited, leading to a lack of early diagnosis and loss to follow-up. The COL4A gene was the most commonly affected gene in hematuria cohorts [8,20]. Mutations in COL4A3/A4/A5 result in a spectrum phenotype from isolated hematuria to end-stage kidney disease, called X-linked Alport syndrome (XL-AS), autosomal recessive Alport syndrome (AR-AS), autosomal dominant Alport syndrome (AD-AS), and a special form of Alport syndrome (Digenic-AS).

Our cohort included 112 children, most of whom had isolated microscopic hematuria. In this study, we used noninvasive genetic testing approaches for type IV collagen-related nephropathy in children with hematuria for Alport-related gene variants. Among them, thirty-seven children (33.0%) had genetic variants in one of the COL4A3/A4/A5 genes. Subgroup analysis revealed that patients with a positive family history, severe hematuria or coexistence with microalbuminuria were more likely to have a COL4A3/A4/A5 variant. Our findings align with recent studies showing that children with hematuria and a family history of chronic kidney disease (CKD) are likely to have a monogenic cause of kidney disease [8]. These findings indicate that genetic testing of COL4A should be considered in children with hematuria, especially those with a positive family history, severe hematuria or coexistence with microalbuminuria.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic COLA3/A4/A5 variants were identified in 17 patients, representing 15.2% of our cohort. Previous reports have suggested that heterozygous COL4A3/A4 mutations may explain approximately 25-40% of families with haematuria [21–24]. Even in a cohort of 101 patents with familial hematuric nephropathies, 80% of cases were caused by COL4A gene pathogenic variants [25]. An important difference between the results of the study is the relatively lower rate of P/LP COL4A3/A4/A5 variants in our cohort, which may be due to the milder renal phenotype (hematuria without mass proteinuria and renal impairment) included. The difference in molecular diagnostic rates between our study and the previous study is likely due to the preselection of a cohort highly enriched for hematuria phenotypes instead of a distinct AS phenotype.

Notably, many children with hematuria in this study had a single heterozygous P/LP variant in either COL4A3 or COL4A4. COL4A3/A4 were the most commonly affected genes, accounting for 82.4% of the cases, while COL4A5 was present in 17.6% of the patients. The low frequency of COL4A5 gene mutations in our study cohort is likely due to the enrollment of pediatric patients with isolated micro-hematuria, which differs from previous studies that have reported a higher frequency of COL4A5 mutations in patients with more severe renal phenotypes. The autosomal dominant form of Alport syndrome was previously considered much rarer than the X-linked form (5% vs. 80%) [26,27]. However, several recent studies have indicated that patients with heterozygous pathogenic variants in COL4A3/A4 account for a significantly greater proportion of patients with Alport syndrome than was previously recognized [25,28–30]. The enormous variability in the frequency of COL4A3/COL4A4 and COL4A5 variants in different studies may be due to differences in cohort phenotypes and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Furthermore, in the normal population, the estimated prevalence of heterozygous pathogenic COL4A3 and COL4A4 variants is 20 times greater than that of COL4A5 variants [31]. Based on the clinical features selected, it is not surprising that the frequency of P/LP variants in COL4A3/A4/A5 in our study was much greater than that in the general population. In our cohort, there were no patients carrying biallelic mutations, which may be related to the milder phenotype of the cases included in this group, as patients with biallelic mutations often exhibit more severe phenotypes.

Individuals with a heterozygous pathogenic COL4A3 or COL4A4 gene have a spectrum of phenotypes ranging from asymptomatic hematuria to progressive renal disease, even between family members with the same mutations [29,32–34]. Multiple previous studies have shown that early initiation of angiotensin blockade is safe in children and helps delay the onset of kidney impairment in AS patients [10,11]. According to the current expert treatment recommendations [15], 14 patients with heterozygous disease-causing variants in COL4A3/A4 were diagnosed with AD-AS, and three patients with a P/LP variant in COL4A5 was diagnosed with XL-AS. According to the recommendation, four patients (F05/F62/F76/F81) with microalbuminuria and the XL-AS male (F63) had initiated ACEi treatment.

In this study, 20 patients were detected carried VUSs, which, while not found in normal populations, has not been previously reported in AS patients and cannot be classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants based on predictive algorithms. Most of the families included individual patients and their parents, which made segregation analyses possible. Although all of them underwent segregation testing as part of the process to resolve the VUS to a clinically actionable result, none of the variants were upgraded to P/LP at present. Patients with COL4A3/A4/A5 gene variants of uncertain significance present a diagnostic challenge. Reclassification of these variants requires further segregation analysis within the family or identification of similarly affected families. Additionally, further functional validation experiments are essential to ascertain whether these genetic variants impair gene function. Future studies that incorporate comprehensive bioinformatic analysis and functional validation of the VUS will be crucial in determining their clinical significance of these variants, which will ultimately guide accurate diagnosis and treatment decision. For those with no variants detected, providing long-term follow-up is recommended for early detection of signs, such as proteinuria or hypertension, that may require further comprehensive evaluation, including whole-exome sequencing.

Our study used a noninvasive oral mucosa-derived DNA source for genetic testing in children with isolated hematuria, differing from previous studies that focused on more severe phenotypes and used traditional blood-derived DNA sources. And our findings suggest that isolated hematuria in early childhood may have a genetic basis, supporting the use of genetic testing for early diagnosis and treatment. However, this study has several limitations, including the potential for undetected rearrangements and large deletions or insertions, and the omission of additional genes, such as CHR5, MYH9, CD151, et al., which may also contribute to the hematuria phenotype. Moreover, the clinical significance of VUS is not yet fully understood. Further research is needed to determine the potential pathogenicity and clinical significance of VUS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that oral mucosa sampling is a valuable tool in the diagnosis of type IV collagen nephropathy and reveals that approximately 15.2% of pediatric hematuria cases are attributed to heterozygous COL4A3/A4/A5 mutations. Noninvasive oral mucosa sampling is recommended for genetic sequencing of COL4A3/A4/A5 genes in children with persistent hematuria, particularly those with a family history, severe hematuria, or elevated microalbuminuria.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants and their family members. We would like to acknowledge Tang Shengnan and her colleagues from Zhong Ke Co., Ltd. (Nantong, China) for sequencing and technology support.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant [number 2021YFC2500202, 2022YFC2705105]; National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant [number 82200743, 81900602].

Authors’ contributions

H.X., Q.S. and D.M. contributed to the study design and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.J.L. drafted the manuscript. J.J.L., D.Y.Z., X.W.W. and T.S. contributed to the patient follow-up. J.L.L., D.Y.Z., X.W.W., T.S., C.Y.W., R.F.D., X.L.H., L.H., W.L.X., J.C., Y.H.Z., and J.R. conducted the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are included in the article.

References

- 1.Vehaskari VM, Rapola J, Koskimies O, et al. Microscopic hematuria in school children: epidemiology and clinicopathologic evaluation. J Pediatr. 1979;95(5 Pt 1):676–684. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80710-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhai YH, Xu H, Zhu GH, et al. Efficacy of urine screening at school: experience in Shanghai, China. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22(12):2073–2079. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murakami M, Yamamoto H, Ueda Y, et al. Urinary screening of elementary and junior high-school children over a 13-year period in Tokyo. Pediatr Nephrol. 1991;5(1):50–53. doi: 10.1007/bf00852844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong X, Ding J, Wang Z, et al. Risk factors associated with abnormal urinalysis in children. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:649068. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.649068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou L, Xi B, Xu Y, et al. Clinical, histological and molecular characteristics of Alport syndrome in Chinese children. J Nephrol. 2023;36(5):1415–1423. doi: 10.1007/s40620-023-01570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vivante A, Afek A, Frenkel-Nir Y, et al. Persistent asymptomatic isolated microscopic hematuria in Israeli adolescents and young adults and risk for end-stage renal disease. Jama. 2011;306(7):729–736. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreno JA, Yuste C, Gutiérrez E, et al. Haematuria as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease progression in glomerular diseases: a review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(4):523–533. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rheault MN, McLaughlin HM, Mitchell A, et al. COL4A gene variants are common in children with hematuria and a family history of kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38(11):3625–3633. doi: 10.1007/s00467-023-05993-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu L, Yap YC, Nguyen DQ, et al. Multicenter study on the genetics of glomerular diseases among southeast and south Asians: deciphering Diversities - Renal Asian Genetics Network (DRAGoN). Clin Genet. 2022;101(5-6):541–551. doi: 10.1111/cge.14116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross O, Licht C, Anders HJ, et al. Early angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in Alport syndrome delays renal failure and improves life expectancy. Kidney Int. 2012;81(5):494–501. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross O, Tönshoff B, Weber LT, et al. A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial with open-arm comparison indicates safety and efficacy of nephroprotective therapy with ramipril in children with Alport’s syndrome. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1275–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savige J, Lipska-Zietkiewicz BS, Watson E, et al. Guidelines for genetic testing and management of alport syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17(1):143–154. doi: 10.2215/cjn.04230321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savige J, Storey H, Watson E, et al. Consensus statement on standards and guidelines for the molecular diagnostics of Alport syndrome: refining the ACMG criteria. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021;29(8):1186–1197. doi: 10.1038/s41431-021-00858-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kashtan CE, Gross O.. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711–719. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savige J, Ariani F, Mari F, et al. Expert consensus guidelines for the genetic diagnosis of Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(7):1175–1189. doi: 10.1007/s00467-018-3985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanks J, Butler G, Cheng D, et al. Clinical and diagnostic utility of genomic sequencing for children referred to a Kidney Genomics Clinic with microscopic haematuria. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38(8):2623–2630. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashtan CE. Genetic testing and glomerular hematuria-A nephrologist’s perspective. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2022;190(3):399–403. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bockenhauer D, Medlar AJ, Ashton E, et al. Genetic testing in renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(6):873–883. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papazachariou L, Papagregoriou G, Hadjipanagi D, et al. Frequent COL4 mutations in familial microhematuria accompanied by later-onset Alport nephropathy due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin Genet. 2017;92(5):517–527. doi: 10.1111/cge.13077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rana K, Wang YY, Powell H, et al. Persistent familial hematuria in children and the locus for thin basement membrane nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(12):1729–1737. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slajpah M, Gorinsek B, Berginc G, et al. Sixteen novel mutations identified in COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 genes in Slovenian families with Alport syndrome and benign familial hematuria. Kidney Int. 2007;71(12):1287–1295. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papazachariou L, Demosthenous P, Pieri M, et al. Frequency of COL4A3/COL4A4 mutations amongst families segregating glomerular microscopic hematuria and evidence for activation of the unfolded protein response. Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis is a frequent development during ageing. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alge JL, Bekheirnia N, Willcockson AR, et al. Variants in genes coding for collagen type IV α-chains are frequent causes of persistent, isolated hematuria during childhood. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38(3):687–695. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05627-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morinière V, Dahan K, Hilbert P, et al. Improving mutation screening in familial hematuric nephropathies through next generation sequencing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(12):2740–2751. doi: 10.1681/asn.2013080912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashtan CE, Segal Y.. Genetic disorders of glomerular basement membranes. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;118(1):c9–c18. doi: 10.1159/000320876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruegel J, Rubel D, Gross O.. Alport syndrome–insights from basic and clinical research. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9(3):170–178. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber S, Strasser K, Rath S, et al. Identification of 47 novel mutations in patients with Alport syndrome and thin basement membrane nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(6):941–955. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savige J. Heterozygous pathogenic COL4A3 and COL4A4 variants (Autosomal Dominant Alport Syndrome) are common, and not typically associated with end-stage kidney failure, hearing loss, or ocular abnormalities. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7(9):1933–1938. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2022.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fallerini C, Dosa L, Tita R, et al. Unbiased next generation sequencing analysis confirms the existence of autosomal dominant Alport syndrome in a relevant fraction of cases. Clin Genet. 2014;86(3):252–257. doi: 10.1111/cge.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibson J, Fieldhouse R, Chan MMY, et al. Prevalence estimates of predicted pathogenic COL4A3-COL4A5 variants in a population sequencing database and their implications for alport syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(9):2273–2290. doi: 10.1681/asn.2020071065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthaiou A, Poulli T, Deltas C.. Prevalence of clinical, pathological and molecular features of glomerular basement membrane nephropathy caused by COL4A3 or COL4A4 mutations: a systematic review. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(6):1025–1036. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfz176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mastrangelo A, Madeira C, Castorina P, et al. Heterozygous COL4A3/COL4A4 mutations: the hidden part of the iceberg? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37(12):2398–2407. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfab334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pierides A, Voskarides K, Athanasiou Y, et al. Clinico-pathological correlations in 127 patients in 11 large pedigrees, segregating one of three heterozygous mutations in the COL4A3/COL4A4 genes associated with familial haematuria and significant late progression to proteinuria and chronic kidney disease from focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(9):2721–2729. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are included in the article.