Abstract

Heterochromatin formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe requires the spreading of histone 3 (H3) Lysine 9 (K9) methylation (me) from nucleation centers by the H3K9 methylase, Suv39/Clr4, and the reader protein, HP1/Swi6. To accomplish this, Suv39/Clr4 and HP1/Swi6 have to associate with nucleosomes both nonspecifically, binding DNA and octamer surfaces and specifically, via recognition of methylated H3K9 by their respective chromodomains. However, how both proteins avoid competition for the same nucleosomes in this process is unclear. Here, we show that phosphorylation tunes the nucleosome affinity of HP1/Swi6 such that it preferentially partitions onto Suv39/Clr4’s trimethyl product rather than its unmethylated substrates. Preferential partitioning enables efficient conversion from di-to trimethylation on nucleosomes in vitro and H3K9me3 spreading in vivo. Together, our data suggests that phosphorylation of HP1/Swi6 creates a regime that relieves competition with the “read-write” mechanism of Suv39/Clr4 for productive heterochromatin spreading.

INTRODUCTION

Heterochromatin is a gene-repressive nuclear structure conserved across eukaryotic genomes1. Heterochromatin assembly requires seeding at nucleation sites and lateral spreading over varying distances to define a silenced domain2. In one highly conserved heterochromatic system, the spreading process requires at least two components: First, a “writer” enzyme, a suppressor of variegation 3–9 methyltransferase homolog (Suv39, Clr4 in S. pombe), which deposits Histone 3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me)3. Spreading by this H3K9 methylation “writer” depends on a positive feedback relationship in which the “writer” also contains a specialized histone-methyl binding chromodomain (CD) that recognizes its own product, H3K9me4,5. Second, spreading then further requires a “reader” protein3,6,7, Heterochromatin Protein 1 (HP1, Swi6 in S. pombe), that also recognizes H3K9me2/3 via a CD8.

How do HP1 proteins execute their essential function in heterochromatin spreading? One manner in which they do so is by directly recruiting the Suv39 methyltransferase to propagate H3K9 methylation9–11. Second, HP1 proteins oligomerize on H3K9me-marked chromatin, which has been invoked as a mechanism that supports spreading12. HP1 oligomerization also underlies its ability to undergo Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) in vitro on its own or with chromatin13–15, and condensate formation in vivo13,14,16,17. This condensate formation may promote spreading by providing a specialized nuclear environment that concentrates HP1 and its effectors18 and/or excludes antagonists of heterochromatin13. The silencing of heterochromatin by HP1 may be coupled to spreading by oligomerization, which likely promotes chromatin compaction and blocks RNA polymerase access19,20. Silencing may also require oligomerization-independent mechanisms like HP1’s ability to bind RNA transcripts and recruit RNA turnover machinery21,22.

However, these proposed mechanisms for HP1’s role in spreading do not contend with a central problem, which is that HP1 and Suv39/Clr4 directly compete for the same substrate on multiple levels. This competition can be specific, as HP1 and Suv39/Clr4 have CDs that recognize the H3K9me2/3 chromatin mark12,23. It is also non-specific, as both HP1 and Suv39/Clr4 bind DNA and histone octamer surfaces of the nucleosome substrate5,17,23–26. How can HP1 promote H3K9 methylation spreading by Suv39/Clr4 but not get in its way? One explanation for managing the specific competition is an observed difference in methylation state preference. Clr4, for example, is more selective for the terminal trimethylated (H3K9me3) state than Swi6 or the other HP1 paralog in S. pombe, Chp223. However, how the significant H3K9me3- independent nucleosome affinity of Clr4 and Swi6 is coordinated to avoid competition is not clear.

One possible way to regulate competition in spreading is through post-translational modifications of HP1. For example, HP1a, HP1α, and Swi6 are phosphorylated by CKII protein kinases27–29. Phosphorylation of HP1 across species has been shown to regulate multiple of its biochemical activities including LLPS13, specificity for H3K9me13,30, and affinity for nucleic acids30. In S. pombe, several Swi6 in vivo phosphorylation sites have been documented in the N-terminal extension (NTE), the CD, and the hinge domain27, which, when mutated, disrupt transcriptional gene silencing27. While HP1 phosphorylation has been known to be important for its function for 20 years31, the mechanisms by which phosphorylation-induced biochemical changes in HP1 direct its cellular activity and coordination with H3K9 “writers” remain unclear.

In this study, we focused on previously identified Swi6 phosphorylation target sites27 and found that two sites in particular, S18 and S24, are required for the spreading, but not nucleation, of heterochromatin. Spreading defects in Swi6 S18/24A mutants arise inability to convert H3K9me2 to H3K9me3 outside creation sites. We show biochemically that the primary role of phosphorylation is to lower Swi6’s overall chromatin affinity. This lowered affinity preferentially partitions Swi6 onto H3K9me3 nucleosomes, rather than unmethylated nucleosomes, in vitro and into heterochromatin foci, rather than the nucleoplasm, in vivo. It may appear counter-intuitive that lowered affinity should have this effect. However, since phosphorylation also increases Swi6’s propensity to oligomerize, this ultimately reduces the Swi6 pool available to bind unmethylated sites. We propose that phosphorylation of Swi6 frees up Clr4’s substrates for efficient trimethylation, and thus, spreading.

RESULTS

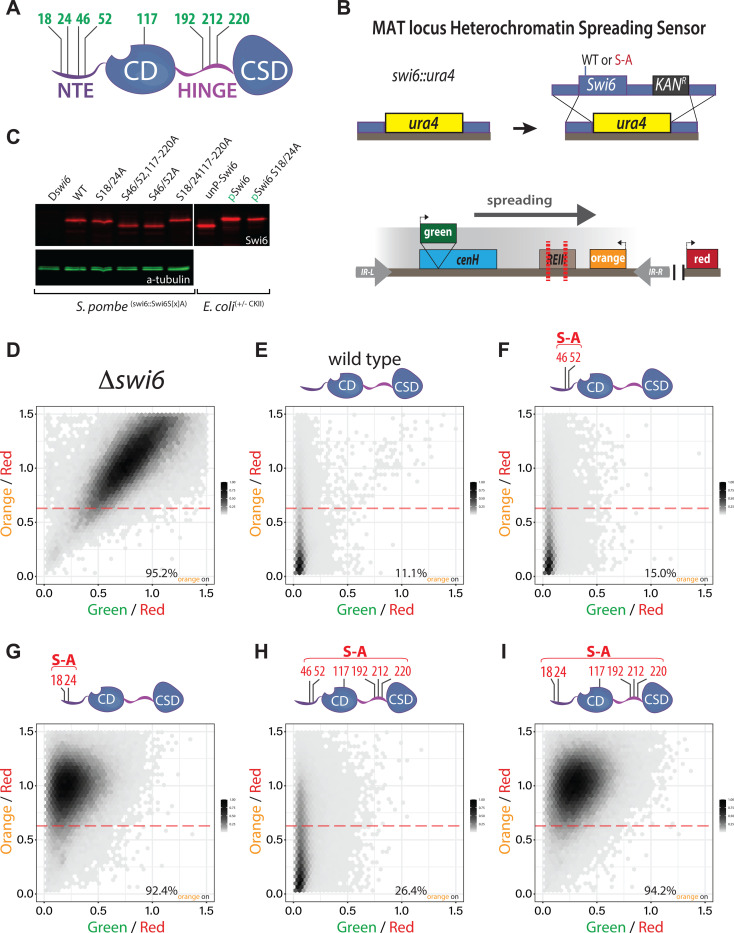

Serines 18 and 24 are necessary for heterochromatin spreading but not nucleation.

Previously, several phosphoserines in Swi6 have been shown to play a role in heterochromatin gene silencing27 (Figure 1A). To address whether the phosphorylation targets play a role in nucleation and/or spreading of heterochromatin, we used our mating type locus (MAT) heterochromatin spreading sensor (HSS32,33) (Figure 1B). The HSS allows us to separate nucleation and spreading events at single-cell resolution via three separate transcriptional reporters: “green” at nucleation sites, “orange” at spreading sites, and “red” in a euchromatic site to control cell-to-cell noise32,33. Specifically, we used a MAT locus HSS with only the cenH nucleator intact (MAT ΔREIII HSS33), which enables us to isolate spreading from one nucleator.

Figure 1: S18 and S24 in Swi6 are required for spreading, but not nucleation of heterochromatin silencing.

A. Overview of the Swi6 protein domain architecture and previously identified (Shimada et al.) in vivo phosphorylation sites (green residue numbers). NTE: N-terminal extension; CD: chromodomain (H3K9me binding); HINGE: unstructured hinge region; CSD: chromo-shadow domain (dimerization and effector recruitment). B. Strategy for production of swi6 S-A mutants in the MAT ΔREIII HSS reporter background. C. Swi6 levels are not affected by S-A mutations. Total extracts of swi6 wild-type or indicated mutants were probed with an anti-Swi6 polyclonal antibody. In vitro purified Swi6 that was either phosphorylated (pSwi6) or not (unpSwi6) is run as size controls. Note, not all mutant Swi6 proteins display a band shift even if they retain phosphosites D.-I. 2-D Density hexbin plots examining silencing at nucleation “green” and spreading “orange” reporter in Δswi6, wild-type, and indicated S-A mutants. The yellow box indicates a “green” and “orange” regime consistent with silencing loss, and the magenta box indicates a regime consistent with loss of spreading, but not nucleation. The dashed line indicates the threshold for orange ON and the numbers the fraction of cells above the line.

To query swi6 serine-to-alanine (S-A) mutants in this background, we first replaced the swi6 open reading frame with the ura4 gene (swi6::ura4). Using homologous recombination, we then replaced the ura4 cassette with either wild-type or S-A mutant swi6 open reading frames followed by a kanamycin resistance marker (Figure 1B). We based our S-A mutations on the phosphoserines previously identified in Shimada et al., which include S18, S24, S46, and S52 in the NTE, S117 in the CD, and S192, S212, and S220 in the hinge (Figure 1A). Here, we constructed the following S-A mutants: S18A and S24A (swi6S18/24A); S46A and S52A (swi6S46/52A); S46A, S52A, S117A, S192A, S212A, and S220A, (swi6S46/52/117−220A, “S18/S24 available”); and S18A, S24A, S117A, S192A, S212A, and S220A (swi6S18/24/117−220A, “S46/S52 available”). These mutants are expressed at similar levels compared to wild-type as assessed by western blot, using a polyclonal anti-Swi6 antibody (Figure 1C, further validated by cytometry in SFigure 4C). Note that not all phospho-site mutants yield an observable band shift by SDS-PAGE gel, even though Swi6 in these mutants is expected to retain phosphorylation at other sites. This was previously observed27 and is likely because the sequence context of a phosphorylated residue determines whether or not it will result in a bandshift34.

When analyzed by flow cytometry, Δswi6 cells exhibit a silencing defect in which both the nucleation (green ON) and spreading (orange ON) reporters are expressed (Figure 1D). Conversely, wild-type swi6 cells show robust silencing of both reporters as we reported prior33 (orange 11.1% ON, Figure 1E). Mutating only S46 and S52 to alanines (swi6S46/52A) largely phenocopies wild-type swi6 (orange 15% ON, Figure 1F). In contrast, mutation of serines at 18 and 24 (swi6S18/24A) resulted in the loss of spreading (orange 92.4% ON), while largely maintaining proper nucleation (green off) (Figure 1G, SFigure 1A–C). Restoring S18 and S24, while mutating the other 6 serines to alanines (swi6S46/52/117−220A) recovers much of the nucleation and spreading observed in wild-type, though with a modest silencing loss at orange (orange 26.4% ON, Figure 1H, SFigure 1D–F). Thus, S18 and S24 play a dominant role in regulating spreading, while other serines make a minor contribution. However, when only S46 and S52 are available (swi6S18/24/117−220A), cells not only exhibit a loss of spreading (orange 94.3% ON) but also a moderate loss of silencing at the nucleator (green shifted towards ON) (Figure 1I). This loss of silencing approaches but is not as severe as the deletion of ckb1, the gene encoding a crucial regulatory subunit of the CKII kinase. This indicates that while the complete loss of Swi6 phosphorylation disrupts spreading (orange 82–83% ON versus 2.3% in the wild-type control, SFigure 1K, L), it also affects silencing at the nucleator. However, this defect is not nearly as severe as in Δswi6 (Figure 1D), highlighting the role of Swi6 phosphorylation primarily in spreading. Overall, we interpret these results to indicate that NTE S18–52 phosphorylation contributes to regulating spreading, with S18/24 as major and 46/52 as minor contributors. Phosphorylation of serines in the Swi6 CD and hinge make a further minor contribution to Swi6’s overall silencing role, which is revealed only in the context of S18/24A. Given the greater loss of silencing revealed by Δckb1, we speculate that there are additional CKII target residues in Swi6, a notion confirmed by our in vitro Mass Spectrometry (see below), and that their phosphorylation contributes to Swi6’s silencing role at the nucleator.

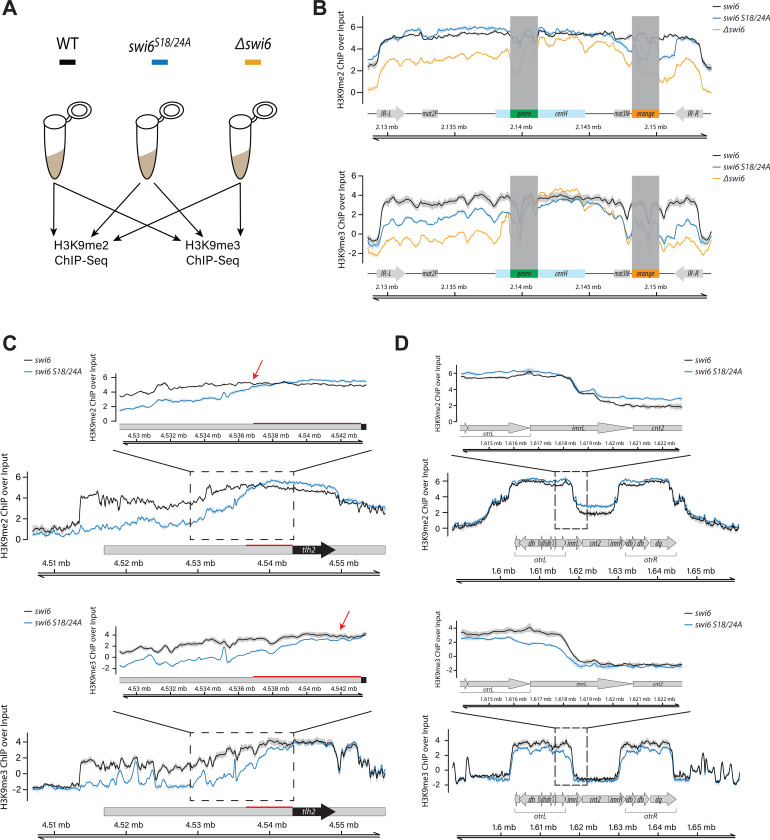

Serines 18 and 24 are required for the spreading of H3K9me3 but not H3K9me2.

We next asked how phosphorylation of S18 and S24 contributes to the propagation of heterochromatic histone marks. We used chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) to address how levels of the heterochromatic marks, Histone 3 lysine 9 di- and trimethylation (H3K9me2/me3), are affected in the context of wild-type swi6, swi6S18/24A, and Δswi6 in the MAT ΔREIII HSS background containing the “green” and “orange” reporters (Figure 2A). Consistent with prior work, we define H3K9me2 as the heterochromatin structural mark35 and H3K9me3 as the heterochromatin spreading and silencing mark7,35,36. We first examined the MAT locus. Note that we cannot make definite statements about ChIP-seq signals over the “green” and “orange” reporters themselves, as the reporter cassettes harbor sequences that are duplicated 3–4 times in the genome32, making ChIP-seq read assignment ambiguous. Overall, H3K9me2 levels at the MAT locus dropped significantly in Δswi6, consistent with prior work7; however, swi6S18/24A mutant maintained similar levels of H3K9me2 to wild-type swi6 (Figure 2B, top). Examining the distribution more closely, at the cenH nucleator, only Δswi6 showed a minor decline of H3K9me2 in some regions. To the left of cenH, H3K9me2 levels decreased in Δswi6 but not in swi6S18/24A. To the right of cenH, H3K9me2 levels also severely declined in Δswi6, while in swi6S18/24A they appear to drop moderately near mat3M, but recovered to wild-type levels at IR-R. When examining H3K9me3, we observed a different relationship: H3K9me3 patterns in swi6S18/24A much more closely mirrored Δswi6. Specifically, to the left of cenH, H3K9me3 dropped to an intermediate level between wild-type and Δswi6, while on the right of cenH, H3K9me3 levels closely matched Δswi6 (Figure 2B, bottom). Importantly, this behavior of H3K9me3 is consistent with our flow cytometry results (Figure 1), where silencing is largely unaffected at “green” in swi6S18/24A, while “orange” was expressed.

Figure 2: Conversion from H3K9me2 to H3K9me3 is compromised outside nucleation centers in S18 and S24 Swi6 mutants.

A. Overview of the ChIP-seq experiments. B-D. ChIP-seq signal visualization plots. The solid ChIP/input line for each genotype represents the mean of three repeats, while the shading represents the 95% confidence interval. B. Plots of H3K9me2 (TOP) and H3K9me3 (BOTTOM) ChIP signal over input at the MAT ΔREIII HSS mating type locus for wild-type (black), swi6S18/24A (blue), and Δswi6 (gold). Signal over “green” and “orange” reporters are greyed out, as reads from these reporters map to multiple locations within the reference sequence, as all reporters contain control elements derived from the ura4 and ade6 genes. C. H3K9me2 (TOP) and H3K9me3 (BOTTOM) plots as in A. for subtelomere IIR for wild-type and swi6S18/24A. The red bar on the H3K9me2 plots indicates the distance from tlh2 to where H3K9me2 levels drop in swi6S18/24A relative to wild-type. Inset: a zoomed-in view proximal to tlh2 is shown for H3K9me2 and me3. The red arrows in the insets indicate the point of separation of the 95% confidence intervals, which is significantly further telomere proximal for H3K9me3. D. H3K9me2 (TOP) and H3K9me3 (BOTTOM) plots as in A. for centromere II for wild-type and swi6S18/24A. Inset: the left side of the pericentromere.

We wanted to further examine if the observation of H3K9me3 loss in swi6S18/24A versus wild-type swi6 held for other genome regions. When we analyzed the subtelomeric region (tel IIR) we found that over the nucleation region tlh2, H3K9me2 levels are slightly elevated in swi6S18/24A, but then begin to drop ~6.4 kb to the left of tlh2 (Figure 2C, top, red bar, and arrow). Interestingly, H3K9me3 levels drop closer to the tlh2 nucleator than H3K9me2; the 95% confidence interval of wild-type and swi6S18/24A separate at the left edge of tlh2 (Figure 2C, bottom). This observation at the tlh2 nucleator suggests the conversion of H3K9me2 to H3K9me3 is inhibited right as heterochromatin structures exit nucleation centers. We observed the same trend at the left subtelomere of chromosome I (tel IL, SFigure 2B). At the subtelomere, spreading distances outside nucleation sites are longer than at other loci, thus this loss of H3K9me3 just outside tlh2 has the opportunity to manifest as an H3K9me2 spreading defect several kilobases downstream. This result is consistent with the requirement of Suv39/Clr4 methyltransferases to bind H3K9me3 for H3K9 methylation spreading5,23. We note that the left telomere of chromosome II contains no annotated nucleators in the published sequence. Hence, we could not observe the same trend there (tel IIL, SFigure 2C). A similar defect in H3K9me3 spreading also occurs at the pericentromere (cenII), specifically, from the outer repeat (otr) into the inner repeat (imr) (Figure 2D, bottom versus top). However, the distances are likely too short from nucleation centers in otr to observe a resulting loss of H3K9me2 (Figure 2D). We note no distinguishable differences in H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 at mei4, a well-studied heterochromatin island (SFigure 1A).

Together, our ChIP-seq data show that swi6S18/24A is deficient in the conversion of H3K9me2 to me3 outside nucleation centers, which results in loss of silencing and ultimately, the loss of H3K9me2 spreading, as evident for the subtelomere.

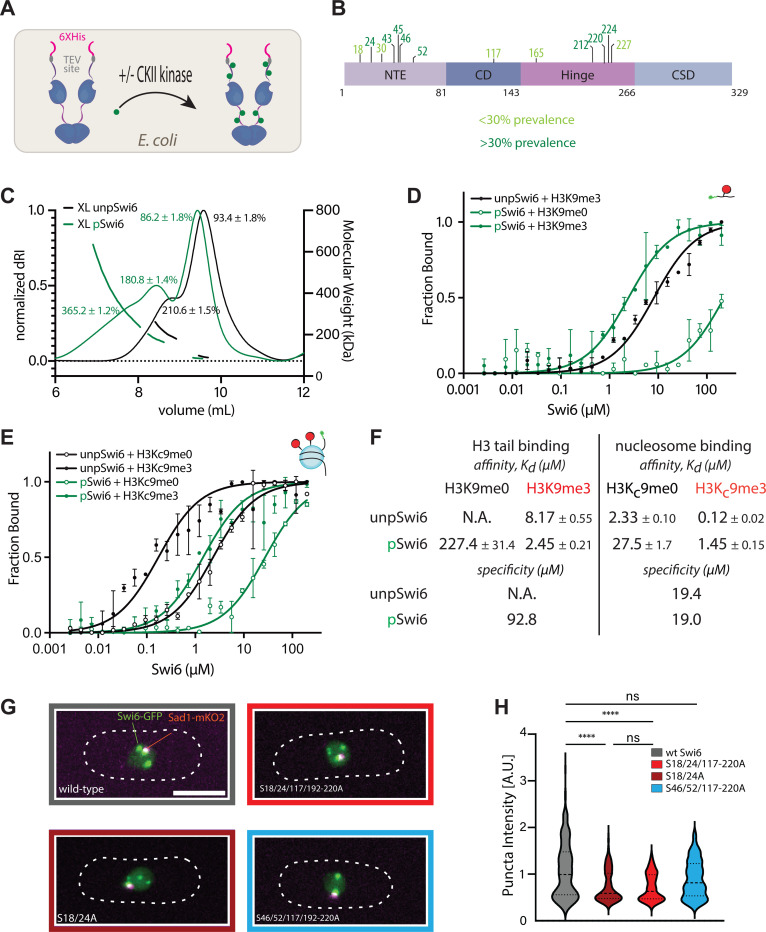

Swi6 phosphorylation increases oligomerization and decreases nucleosome affinity.

Next, we wanted to pinpoint the biochemical mechanisms that can account for the spreading defects in swi6S18/24A (Figure 1G, Figure 2). HP1 oligomerization has been linked to spreading12. In turn, HP1’s intranuclear dynamics have been linked to how it engages chromatin37–40. We thus probed if and how phosphorylation may impact these two properties of Swi6.

We used Size Exclusion Chromatography followed by Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) to probe oligomerization, and fluorescence polarization to quantify H3K9me3 peptide and nucleosome binding. To produce phosphorylated Swi6 (pSwi6), we co-expressed Swi6 with Caesin Kinase II (CKII) in E. coli (Figure 3A). We used 2-dimensional Electron Transfer Dissociation Mass Spectrometry (2D ETD-MS) to identify which residues in pSwi6 are phosphorylated and used unphosphorylated Swi6 (unpSwi6) as a control (Figure 3B). We found that only pSwi6, and not unpSwi6, has detectable phosphorylated peptides. The residues phosphorylated in pSwi6 include several that were identified in vivo (Figure 1A, S18, S24, S46, S52, S117, S212, S220 but not S192) and some additional sites not previously identified (S43, S45, S165, S224, S227). This detection of additional CKII target sites is likely because of the higher sensitivity achieved in our 2D-ETD-MS experiments from purified protein: 1. 2D-ETD-MS better preserves phosphorylation sites compared to other methods and is highly sensitive. 2 Pure, in vitro-produced protein of high yield is likely to result in more detection events than in vivo-derived protein.

Figure 3: Swi6 phosphorylation increases oligomerization and decreases nucleosome binding, without affecting specificity.

A. Production of phosphorylated Swi6 (pSwi6) in E. coli. Casein Kinase II (CKII) is co-expressed with Swi6. After lysis and purification, the 6X His tag is removed from the pSwi6 or unpSwi6 protein. B. Mass Spectrometry on pSwi6. Shown is a domain diagram of Swi6. Phosphorylation sites identified in pSwi6 by 2D-ETD-MS are indicated and grouped by detection prevalence in the sample. C. Size Exclusion Chromatography followed by Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) on EDC/NHS cross-linked unpSwi6 (black) and pSwi6 (green). Relative refractive index signals (solid lines, left y-axis) and derived molar masses (lines over particular species, right y-axis) are shown as a function of the elution volume. [Swi6] was 100μM. D. Fluorescence polarization (FP) with fluorescein (star)- labeled H3 tail peptides (1–20) and pSwi6 (green) or unpSwi6 (black) for H3K9me0 (open circles) and H3K9me3 (filled circles) is shown. Error bars represent standard deviation. Binding was too low to be fit for unpSwi6 and H3K9me0 peptides. E. FP with H3K9me0 (open circles) or H3Kc9me3 (MLA, filled circles) mononucleosomes. Fluorescein (green star) is attached by a flexible linker at one end of the 147 bp DNA template. For D.&E., the average of three independent fluorescent polarization experiments for each substrate is shown. Error bars represent standard deviation. F. Summary table of affinities and specificities for D. and E. G. Representative maximum projection live microscopy images of indicated Swi6-GFP / Sad1-mKO2 strains. H. Analysis of signal intensity in Swi6-GFP foci in indicated strains. Wt Swi6, n=242; Swi6S18/24A, n=251; Swi6S18/24/117−220A, n=145; Swi6S46/52/117−220A, n=192. n, number of foci analyzed.

SEC-MALS traces of uncrosslinked pSwi6 and unpSwi6 reveal both proteins are estimated to be of similar dimer mass, 90.8 kDa and 100.4 kDa respectively (SFigure 3A). However, pSwi6 elutes before Swi6, a trend similar to phosphorylated HP1α13. There is also a small shoulder in the pSwi6 trace, indicating a minor fraction of higher-order oligomers (SFigure 3A, grey arrow). As previously published12, Swi6 crosslinking leads to the appearance of higher molecular weight species. We observed that crosslinked Swi6 and pSwi6 elute as apparent dimers (93.4 and 86.2 kDa, respectively) and tetramers (210.6 and 180.8 kDa, respectively) (Figure 3D). However, only pSwi6 additionally forms octamers (365.2kDa) and possibly even larger oligomers, as indicated by a broad shoulder (Figure 3D).

We next quantified the binding of pSwi6 to H3K9me0 and H3K9me3 peptides by fluorescence polarization (Figure 3D). pSwi6 binds to H3K9me0 and H3K9me3 peptides with affinities (Kd) of 227.4μM and 2.45μM, respectively, revealing a ~93X specificity for H3K9me3 (Figure 3F). While we could not determine the H3K9me0 peptide Kd for unpSwi6, the Kd for the H3K9me3 peptide was 8.17 μM (Figure 3D, F). Previously, the specificity for unpSwi6 was reported at ~130X12, thus indicating little difference in H3K9me3 peptide specificity between the two proteins. We note that consistent with previous reports on total cellular Swi635, recombinant pSwi6 also shows a ~2.2X preference for H3K9me3 versus H3K9me2 peptides (SFigure 3E).

We next probed how phosphorylation affects nucleosome binding. We performed fluorescence polarization with fluorescently labeled nucleosomes that are unmethylated (H3K9me0) or trimethylated (H3Kc9me3)41,12. Phosphorylation had no impact on the specificity for the H3K9me3 mark, consistent with the peptide observation (19.4X, vs. 19X for unpSwi6 or pSw6, respectively, Figure 3E, F).

However, we observe a 12X difference in affinity to the nucleosome overall between pSwi6 and Swi6 (Figure 3F). The H3Kc9me3 nucleosome affinity is 0.12 μM and 1.45 μM for unpSwi6 and pSwi6, respectively, while the H3K9me0 affinity is 2.33 and 27.5 μM, respectively. We note the affinity of pSwi6 to the H3Kc9me3 nucleosome is similar to its affinity to the H3K9me3 peptide, binding only 1.7X tighter to the H3Kc9me3 nucleosome (1.45μM vs. 2.45μM). Instead, and consistent with previous results, unpSwi6 binds 68X more tightly to the nucleosome than to the tail (8.17 μM for the H3K9me3 tail versus 0.12μM for H3Kc9me3), which is thought to arise from additional contacts beyond the H3 tail on the nucleosome.

Why would a 12X lower affinity towards the nucleosome substrate be advantageous for pSwi6’s function in spreading (Figure 1,2)? In the literature, the cellular abundance of Swi6 is measured at 9000– 19,400 molecules per cell42,43. The estimated fission yeast nuclear volume of ~7mm3 44,45 then yields an approximate intranuclear Swi6 concentration of ~2.1 −4.6μM. Given our measured nucleosome Kds (Figure 3F), the intranuclear concentration of unpSwi6 would theoretically be above its Kd for both H3K9me0 and me3 nucleosomes. The concentration of pSwi6 would exceed its Kd for H3Kc9me3 but be significantly below (~10X) its Kd for H3K9me0 nucleosomes. We cannot assume the same fraction of bound nucleosome from in vitro measurements applies in vivo, because nucleosome concentrations in the cell (~10μM based on accessible genome size and average nucleosome density46,47) greatly exceed what is used in a binding isotherm. We can use a quadratic equation48 (see methods) appropriate for these in vivo regimes instead of a typical Kd fit to estimate the fraction bound. As only 2% of the S. pombe genome is heterochromatic, we approximate the total nucleosome concentration (10μM) to reflect unmethylated nucleosomes. The small, methylated nucleosome pool will mostly be bound by Swi6 irrespective of the phosphorylation state. However, we estimate that only 5% of unmethylated nucleosomes would be bound by pSwi6, while this would be ~16% for unpSwi6. At the high end of the Swi6 concentration estimate, this fraction bound would increase to 30% of unmethylated nucleosomes. Further, we expect enhanced oligomerization of pSwi6 on heterochromatin to reduce the free Swi6 pool (see discussion). Therefore, we predict that the main function of phosphorylation is to limit the partitioning of Swi6 into the unmethylated pool, confining it to heterochromatin.

One test of this prediction would be altered localization of wild-type and phosphorylation defective Swi6 versions in the fission yeast nucleus. Across species, HP1 homologs have been shown to localize into heterochromatic foci in vivo and form LLPS droplets in vitro 13,14,16,37. Specifically, phosphorylation of the NTE in human HP1α is one driver of heterochromatin foci formation13,38. We investigated whether the loss of phosphorylation sites that impair heterochromatin spreading (Figure 1, 2) impacted partitioning between heterochromatin foci and regions outside these foci, likely representing H3K9 unmethylated nucleosomes. We C-terminally tagged wild-type swi6 and phospho-serine mutants at the native locus with super fold-GFP (Swi6-GFP), as an N-terminal tag disrupt Swi6 dimerization and oligomerization25. We crossed these strains into a background containing sad1:mKO2, a spindle pole body (SPB) marker (SFigure 4A). We chose this background, as Sad1 denotes the position of pericentromeric heterochromatin49,50 and can help orient other heterochromatin sites relative to it. We examined the following SF-GFP tagged mutant variants: swi6S18/24A, swi6S46/52A, swi6S46/52/117−220A (S18/S24 available), swi6S18/24/117−220A (S46/S52 available) (Figure 1G–I) and imaged these strains by confocal microscopy (Figure 3G, SFigure 4B). Largely, these mutations do not impact either Swi6 accumulation (SFigure 4C), nuclear foci number (SFigure 4D), or position of the foci relative to the SPB51 (SFigure 4E, F).

We next quantified the accumulation of Swi6-GFP in foci. Unlike foci number or spatial arrangement, the average foci intensity for Swi6-GFP strains carrying the S18/24A mutations is significantly decreased relative to wild-type Swi6-GFP (Figure 3H), while the nucleoplasmic signal increases. Because total Swi6-GFP levels do not change in these mutants (SFigure 4C), this result indicates that Swi6S18/24A-GFP and Swi6S18/24/117−220A -GFP molecules partition away from heterochromatin foci. This finding is consistent with our prediction based on our in vitro measurements and implies that Swi6 molecules that cannot normally be phosphorylated partition onto unmethylated nucleosomes.

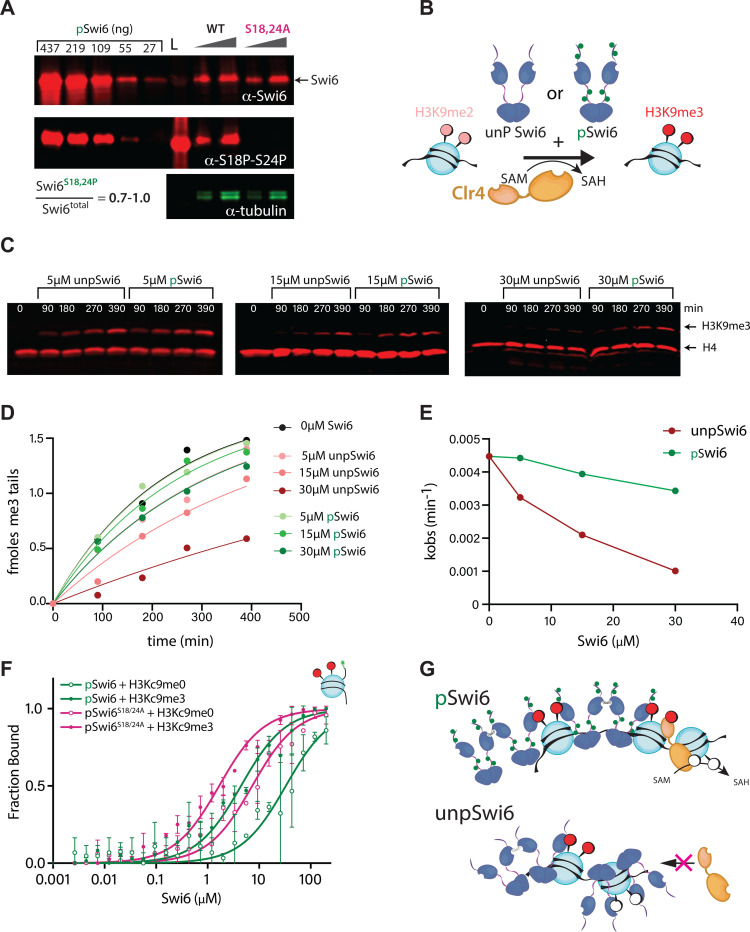

Swi6 phosphorylation facilitates the conversion of H3K9me2 to me3 by Clr4.

As unmethylated nucleosomes are Clr4’s substrates, another prediction emerges. Since unpSwi6 is more likely to bind unmethylated nucleosomes, Swi6 phosphorylation mutants may interfere with Clr4 substrates, which could explain the defect in H3K9me2 to me3 conversion in swi6S18/24A (Figure 2), the slowest transition catalyzed by Clr423. For Swi6 phosphorylation to prevent the conversion of H3K9me to me3, the Swi6 cellular pool would have to be mostly in the phosphorylated state. To test this, we asked what fraction of Swi6 molecules in the cell are phosphorylated at S18 and S24. We addressed this question by a quantitative western blot approach, using two antibodies: a polyclonal Swi6 antibody25 to detect all Swi6 molecules and a phospho-serine antibody specific to phosphorylation at S18 and S24 (top blot vs. bottom blot, respectively, Figure 4A). A standard curve of recombinant pSwi6 allowed us to quantify the total pool of Swi6 molecules vs. those phosphorylated at S18 and S24. The swi6S18/24A mutant control shows these phospho-serine antibodies are indeed specific (Figure 4A). We showed that the majority of cellular Swi6 is phosphorylated at S18 and S24 (Figure 4A and SFigure 5A), 70% and 100% across two biological replicate experiments.

Figure 4: Swi6 phosphorylation mitigates inhibition of the Clr4-mediated conversion of H3K9me2 to H3K9me3.

A. Most Swi6 molecules in the cell are phosphorylated at S18 and S24. Quantitative western blots against total Swi6 and phosphorylated Swi6 at S18/S24. A standard curve of pSwi6 isolated as in Figure 3 is included in both blots. Total protein lysates from wild-type swi6 and swi6S18/24A strains were probed with a polyclonal anti-Swi6 antibody (α-Swi6) or an antibody raised against a phosphorylated S18/S24 peptide (α-S18P-S24P). α-tubulin was used as a loading control. One of two independent experiments is shown. L; ladder. B. Experimental scheme to probe the impact of Swi6 on H3K9 trimethylation. C. Quantitative western blots on the time-dependent formation of H3K9me3 from H3K9me2 mononucleosomes in the presence of pSwi6 or unpSwi6. The same blots were probed with α-H3K9me3 and α-H4 antibodies as a loading and normalization control. D. Single exponential fits of production of H3K9me3 tails over time for indicated concentrations of unpSwi6 or pSwi6. E. plot of kobs vs. [Swi6] (μM). F. Fluorescence polarization with H3K9me0 (open circles) or H3Kc9me3 (MLA, filled circles) mononucleosomes as in Figure 3E., with pSwi6 (green) or pSwi6S18/24A (magenta). Relative Kd values in Table 1. Error bars represent standard deviation. G. Model of the impact of pSwi6 on Clr4 activity. Top: pSwi6 does not engage with K3K9me0 nucleosomes, clearing the substrate for Clr4, and has reduced interactions with the nucleosome core. Bottom: Swi6 binds H3K9me3 and me0 nucleosomes, occluding Clr4 access.

We next tested if Swi6 phosphorylation directly impacted the ability of Clr4 to produce H3K9me3. We incubated pSwi6 or unpSwi6 with Clr4 and monitored the conversion of the H3K9me2 substrate to H3K9me3 under single turnover conditions23 (Figure 4B). pSwi6 shows an in vitro preference for H3K9me3 versus H3K9me2 peptides (SFigure 3E), suggesting that phosphorylation may partition Swi6 towards H3K9me3 versus me0, but also, to some extent, towards H3K9me3 versus me2.

We observed that the presence of unpSwi6 inhibits the conversion of H3K9me2 to H3K9me3 in a concentration-dependent manner, but that this inhibition is significantly alleviated by pSwi6 (Figure 4C and SFigure 5B,C). Note we observe inhibition at the lowest concentration, 5μM, which is near the estimated in vivo concentration of Swi6. When normalizing to H4 and fitting H3K9me3 to kobs, Clr4 methylation rates are significantly slowed in the presence of unpSwi6, while pSwi6 reduces this inhibition (Figure 4D, E).

While these data could explain the H3K9me3-spreading defect, we observe for swi6S18/24A (Figure 2), our in vitro-produced pSwi6 is phosphorylated at multiple residues. Given that S18 and S24 only represent around 1/6 of the detected phosphorylation sites (Figure 3B), we cannot necessarily conclude whether the biochemical phenotypes we observe depend on S18 and S24 phosphorylation. To examine this, we expressed and purified a phospho-mutant protein, pSwi6S18/24A, in which S18 and S24 are mutated to alanines and co-expressed it with CKII. pSwi6S18/24A is still phosphorylated to a similar degree as pSwi6, which is apparent by the similar gel migration shift observed for both proteins (SFigure 3B,C). Upon phosphatase treatment, pSwi6S18/24A and pSwi6 adopt the same migration pattern as unpSwi6 (SFigure 3B, C). 2D ETD-MS analysis of pSwi6S18/24A additionally confirmed a similar phosphopeptide pattern to pSwi6, though with small changes in phosphopeptide prevalence (SFigure 3D).

We examined nucleosome affinity of pSwi6S18/24A compared to pSwi6 via fluorescence polarization and found that pSwi6S18/24A shows increased affinity towards both the H3K9me0 and Kc9me3 nucleosomes, 4.5 and 2.6X, respectively (Figure 4F). This result is consistent with S18 and S24 phosphorylation sites acting to modulate Swi6’s chromatin affinity. However, since the change in affinity for pSwi6S18/24A is less than the 12X loss observed for unpSwi6 vs. pSwi6, this implies that other phosphoserines also contribute to lowering nucleosome affinity.

Overall, this data suggests a model whereby Swi6 NTE phosphorylation, particularly at S18 and S24, partitions Swi6 away from binding the unmethylated substrate of Clr4 in vivo, which is likely enhanced by increased Swi6 oligomerization at heterochromatin sites. Together, both reduced affinity and oligomerization mechanisms promote the H3K9me3 spreading reaction.

DISCUSSION

Previous work27 identified key Swi6 phosphoserines that regulate transcriptional gene silencing. In this work, we find that Swi6 phosphoserines 18 and 24 are required for heterochromatin spreading, but not nucleation (Figure 1). Swi6 phosphorylation promotes oligomerization, and tunes Swi6’s overall chromatin affinity to a regime that allows Clr4 to access its substrate (Figure 3), facilitating the conversion of dimethyl H3K9 to the repressive and spreading-promoting trimethyl H3K9 state (Figure 4). This modulation of chromatin affinity in vivo restricts Swi6 to heterochromatin foci (Figure 3, Figure S4), which suggests that phosphorylation of HP1 molecules may be required for their concentration into the heterochromatic compartment. Three central themes emerge from this work:

Swi6 phosphorylation decreases chromatin affinity, but not specificity.

Phosphorylation is known to regulate HP1’s affinity with itself13, DNA30,38, and chromatin30,38, but in manners that are homolog-specific. For example, phosphorylation in the NTE of HP1α induces LLPS, but not for HP1a in Drosophila, where phosphorylation instead regulates chromatin binding16,31,52. Underlying this may be that CKII target sequences are not conserved across HP1s, for example, HP1α is phosphorylated in a cluster of 4 serines at the NTE (S11–14)29, HP1a only at S15 in the NTE, and S202 C-terminal to the CSD31, whereas we report here Swi6 is phosphorylated by CKII in the NTE, CD, and hinge (Figure 3B).

Phosphorylation increases the affinity towards H3K9me3 and H3K9me0 peptides both for Swi6 (Figure 3D) and HP1α38. However, the impact on nucleosome specificity is different across species. Our data here shows that phosphorylation of Swi6 does not affect its specificity for both H3K9me0 and H3Kc9me3 nucleosomes (Figure 3E, F), but phosphorylation of HP1α and HP1a was reported to increase its specificity for H3K9me3 nucleosomes13,30. Instead, Swi6 phosphorylation decreases overall nucleosome affinity for unmethylated and H3Kc9me3 nucleosomes to a similar degree, 11.8X and 12X respectively, in contrast to HP1α30,53. What may explain these differences? Internal interactions between the NTE, CD, hinge, and CSD work together to drive nucleosome binding17,25. We speculate that these domain interactions are differentially impacted by 1. the unique phosphorylation patterns in different HP1 orthologs (see above) and 2. divergence in Swi6 amino acid sequence and size of the NTE and hinge that harbor most CKII target sites. Both these differences result in unique outcomes with respect to nucleosome specificity and affinity in different HP1 orthologs. Cross-linking mass spectrometry studies indicate that the NTE of HP1α54, as well as Swi617, contact the C-terminus of H2A.Z/H2A, respectively, H2B, and the core (HP1α) and tail (Swi6) of H3, among other contacts. NTE phosphorylation may specifically decrease these contacts, leading to detachment from the nucleosome core.

This overall decrease in affinity partitions pSwi6 in a different way than unpSwi6, restricting access of pSwi6 to chromatin inside nuclear foci. This is supported by our imaging data (Figure 3, SFigure 4) but is also consistent with data from human HP1α38 and in vivo diffusion measurements in the swi6 sm-1 mutant. This mutant likely disrupts NTE phosphorylation and shows greater residence outside heterochromatin39. Further, it is likely that increased oligomerization of pSwi6 additionally strengthens this partitioning onto heterochromatin (next section). A separate consequence of this affinity decrease is the relief of competition with Clr4 for the nucleosome substrate (Figure 4, see third section below).

Swi6 phosphorylation increases oligomerization.

Swi6 has been shown to form dimers and higher-order oligomers. Swi6 oligomerization across chromatin has been linked to heterochromatin spreading in vivo12. Here, we show that phosphorylation increases the fraction of oligomeric states, revealing octamers and possibly higher molecular weight species (Figure 3). Swi6 exists in a closed dimer that inhibits the spreading competent state, or an open dimer that promotes oligomerization25. One way pSwi6 could form higher molecular weight oligomers is by phosphorylation shifting the equilibrium from the closed dimer to the open dimer25. We speculate the following thermodynamic consequence of phosphorylation on the nuclear Swi6 pool: Oligomerization will be driven at sites of high Swi6 accumulation, which is likely near its high-affinity H3K9me3 nucleosome target. If this is true, oligomerization will reduce the pool of free Swi6 available to engage unmethylated nucleosomes even further, and below the theoretical level we described above (~5%).

HP1 proteins, like Swi6, form foci in vivo, which are associated with condensate formation, rooted in HP1 oligomerization13,16,17. The reduction of GFP-Swi6S18/24A in nuclear foci we observe (Figure 3) may be due to defects in condensate formation, or simply that fewer Swi6 molecules are available to form heterochromatic condensates. As discussed above, we expect defects in phosphorylation to steer Swi6 toward unmethylated chromatin sites. The reduction of GFP signal in Swi6S18/24A mutant foci may thus be due to losing Swi6 molecules to the nucleoplasmic space.

Phosphorylation of Swi6 enables H3K9 trimethylation by Clr4.

Achieving H3K9 trimethylation is essential for both gene silencing and heterochromatin spreading by Suv39/Clr4 enzymes5,23. For heterochromatin spreading, this is due to the positive feedback loop within Suv39/Clr4, which depends on binding trimethyl H3K9 tails via the CD23,35,55.

For Clr4, the conversion from H3K9me0 to me1 and H3K9me1 to me2 is 10X faster than the conversion from H3K9me2 to me323. This slow step requires significant residence time on the nucleosome and is thus highly sensitive to factors promoting or antagonizing Clr4 substrate access, as well as nucleosome density56. Clr4 and Swi6 both make extensive contacts with nucleosomal DNA and the octamer core17,24. unpSwi6 and Clr4 affinity to H3K9me0 nucleosomes are very similar (1.8μM and 2.3μM for Clr423 and Swi6, respectively), but nuclear Swi6 concentration (2–4 μM) is likely higher than the Clr4 concentration57. Thus, unpSwi6 would compete and displace Clr4 from its substrate. However, pSwi6’s affinity for the H3K9me0 nucleosome (28μM) is in a regime that is well above its predicted in vivo concentration. Any residual competition between pSwi6 and Clr4 would be mitigated by this lower affinity and the likely higher affinity of the Clr4 complex to its in vivo nucleosome substrate, driven by additional chromatin modfications58.

This lowered pSwi6 nucleosome affinity likely relieves the trimethylation inhibition we observe for unpSwi6 (Figure 4). Therefore, we propose that a major outcome of Swi6 phosphorylation is to clear nucleosome surfaces for Clr4 to access its substrate (Figure 4G). An alternative, and non-exclusive, possibility is that the reduced affinity of pSwi6 to trimethyl nucleosomes may also limit the ability of Clr4/Suv39 to spread across nucleosomes, which requires the engagement of its CD23. While the Kc9me3 nucleosome Kd of pSwi6 is just below its predicted in vivo concentration, the fraction bound at trimethylated nucleosomes in vivo would be expected to somewhat lower than for unpSwi6. We note, that instead of starting with H3K9me0 nucleosomes, we examined the conversion of H3K9me2 to me3. pSwi6 may have increased affinity to those H3K9me2 than H3K9me0 substrates43. However, it has been shown by us (SFigure 3E) and others35 that pSwi6 or Swi6 isolated from S. pombe cells, which is mostly phosphorylated (Figure 4A), has a preference for H3K9me3 over H3K9me235. This lower H3K9me2 preference may still help pSwi6 distinguish between binding H3K9me2 versus me3 chromatin in vivo, and not just H3K9me0 versus H3K9me3.

Our in vivo data (Figures 1–3) reveals several serines in Swi6 contribute to spreading, but S18 and S24 have a dominant effect. The contribution of other serines is highlighted by 1. A change in nucleosome affinity in pSwi6S18/24A that is 3–4X less than for unpSwi6 (Figure 4F and Table 1), and, 2. The additional phenotype of swi6S18−220A in gene silencing compared to swi6S18/24A (Figure 1, SFigure 1). Still, why might these two residues, when mutated, have a strong impact on heterochromatin spreading? It is possible that phosphorylation of S18 and S24 plays a disproportional role versus other residues in shifting the Swi6 from the closed to the open state. Alternatively, it is possible that in vivo, phosphorylation at S18 and S24 are involved in the recruitment of H3K9me3-promoting factors, including Clr3, and also other factors like Abo136,59,60. Prior work 27 has shown that Clr3 recruitment to heterochromatin is somewhat compromised in swi6S18−117A, while the recruitment of the anti-silencing protein Epe1 is increased. While this loss of Clr3 and gain of Epe1 may be an indirect consequence of compromised heterochromatin in swi6S18−117A, it cannot be excluded that phosphorylation at S18 and S24 is necessary to help recruit Clr3 and/or exclude Epe1. This would provide another mechanism for Swi6 to support trimethylation spreading by Clr4. Whether this is the case requires further investigation.

Table 1.

Relative affinities of pSwi6 and pSwi6S18/24A for H3K9me0 and H3K9me3 nucleosomes.

Together, we believe that our work resolves a critical problem in heterochromatin biology, which is how “writers” and “readers” promote heterochromatin spreading if they compete for the same substrate surfaces. Phosphorylation of Swi6 tunes the partitioning of Swi6 between unmethylated and methylated nucleosomes in vivo, such that Clr4 unmethylated substrates remain largely unbound. Whether this phosphorylation is regulated temporally, at different stages of heterochromatin formation, or spatially, at nucleation versus spreading sites, remains to be investigated.

LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

In this study, we examine how the phosphorylation of Swi6, especially at S18 and S24, impacts its association with chromatin and interaction with Clr4/Suv39 and, ultimately, heterochromatin spreading. We connect the loss of H3K9 trimethyl spreading and delocalization from heterochromatin foci in swi6S28/24A mutants in vivo to an increased affinity for unmethylated nucleosomes by unpSwi6. However, it is possible that phosphorylation at S18 and S24 is important for the specific recruitment of Swi6 into heterochromatin foci by other factors. Our study does not directly address this possibility. Our biochemical work does not provide direct insight into why S18 and S24 are dominant in vivo compared to other phospho-serines. Further, while we show that pSwi6 drives increased oligomerization, we have no direct evidence that increased oligomerization via phosphorylation in vivo supports H3K9 trimethyl spreading. This would require uncoupling phosphorylation from oligomerization, which we have not been able to do so far. Our kinetic studies focus on the impact of Swi6 phosphorylation on the conversation of H3K9me2 to me3. While Swi6 does prefer H3K9me3 over me2, we do not know if this preference is sufficient in vivo to decrease the residence of pSwi6 on H3K9me2 enough not to inhibit Clr4/Suv39 and support conversion to H3K9me3. Finally, while we show inhibition of this conversion by unpSwi6, our study does not address whether unpSwi6 and Clr4/Suv39 occupy the exact same surfaces on the nucleosome. Theoretically they could co-occupy the nucleosome, and antagonism by unpSwi6 may utilize a mechanism other than displacement/occlusion.

METHODS

Strain construction

To construct wild-type swi6 and swi6 phosphoserine mutants, the swi6 open reading frame (ORF) was first deleted by integrating a ura4 gene cassette in the MAT HSS background. A plasmid, pRS316, was constructed containing 5’ homology-swi6 promoter-swi6 (or swi6 S-A mutant)- 3’ UTR-kan-3’ genome homology and linearized by PmeI double digest to replace the ura4 cassette by genomic integration via homologous recombination. After transformation, cells were plated on YES agar for 24 hours before replica plating on G418 selection plates. For the Δckb1 mutant, we crossed the deletion strain from our chromatin function library32 to the MAT ΔREIII HSS and selected Δckb1 MAT ΔREIII HSS strains by random spore analysis on HYG+G418 double selection. For Swi6-GFP fusions in the Sad1-mKO2 background, swi6 wild-type and swi6 S-A mutant strains were first crossed with the sad1::mkO2 strain to remove the MAT HSS. Next, swi6 and swi6 S-A mutant ORFs were C-terminally fused to SF-GFP followed by a hygromycin resistance marker by CRISPR/Cas9 editing as previously described61. Modifications were confirmed by gDNA extraction and PCR amplification of the 5’ swi6 to 3’ genome region downstream from the hygromycin marker. For all strain construction, isolates were verified by genomic PCR.

Western blot

Proteins were separated on a 15% SDS-Page gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore) for 90 minutes at 100V and 4°C. Membranes were blocked overnight in 1:1 1X PBS: Intercept PBS Blocking Buffer (LiCor). Next, membranes were incubated with either polyclonal anti-Swi6 antibody25 or anti-pSwi6 antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals, this study) diluted 1:1000 in 1:1 1X PBS, 0.2% Tween-20 (PBS-T): Intercept PBS Blocking Buffer overnight at 4°C on a nutator. Anti-α-tubulin antibody was diluted 1:2000 and used as loading control. Membranes were washed twice with PBS-T for 10 minutes followed by two washes for 5 minutes before incubation with secondary antibodies. Secondary fluorescent antibodies were diluted either 1:10000 (anti-rabbit, 680 nm, Cell Signaling Technology 5366P, lot # 14) or 1:5000 (anti-mouse, 800 nm, Li-Cor, D10603–05) and were incubated with the membranes for 45 minutes at RT. Finally, membranes were washed 3 times with PBS-T for 10 minutes and once with PBS for 10 minutes before imaging on a LiCor Odyssey CLx imager.

HSS Flow cytometry

Strains were struck out of a −80°C freezer onto YES plates. Recovered cells were grown in 200 μL of YES media in a 96-well plate overnight to saturation at 32°C. The next morning, cells were diluted 1:25 in YES media into mid-log phase and analyzed by flow cytometry on an LSR Fortessa X50 (BD Biosciences). Fluorescence compensation, data analysis, and plotting in R were performed as described in Greenstein et al. 202233.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP -seq) sample collection and library preparation

Cells were grown in YES media overnight to saturation (32°C, 225RPM shaking). The following morning cells were diluted to OD 0.03, grown to OD 1, and 300×106 were fixed and frozen at - 80°C. Cells were processed for ChIP as described in Canzio et al. 2011 with the following modifications: Three technical replicates were processed for ChIP-seq. After lysis, cells were bead beat 10 rounds for 1 minute each round with 0.5 mm Zirconia/Silica beads (Cat No. 11079105z). Tubes were chilled on ice for 2 minutes between rounds. Lysates were then spun down to isolate chromatin. The chromatin pellet was resuspended in 1.5 mL lysis buffer, moved to a 15 mL Diagenode Bioruptor tube (Cat. No. C01020031) and sonicated with a Diagenode Bioruptor Pico sonicator for a total of 35 cycles, 30 seconds on/ 30 seconds off, in the presence of sonication beads (Diagenode, Cat. No. C03070001). Every 10 cycles tubes were vortexed. Chromatin lysate was spun down for 30 minutes at 14000 RPM and 4°C. The lysate volume was brought up to 900 μL. 45 μL was taken out to check shearing of the DNA. 40 μL was taken out for input and kept at RT until the reverse crosslinking step. The remaining ~800 μL was divided into 2 tubes to incubate with either 2 μL anti-H3K9me2 (Abcam 1120, Lot No. 1009758–6) or 1 μg anti-H3K9me3 (Diagenode, Cat. No. C15500003 Lot No. 003) overnight on a tube rotator at 4°C. The next morning, Protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen, LOT 01102248) and M280 Streptavidin beads (Invitrogen, LOT 2692541) were washed twice with Lysis Buffer without protease inhibitors. 20 μL Protein A Dynabeads beads were added to each anti-H3K9me2 sample, and 30 μL M-280 Streptavidin beads were added to each anti-H3K9me3 sample. Beads were incubated with samples for 3 hours on a tube rotator at 4°C, and then washed with 700 μL cold buffers at RT on a tube rotator in the following order: 2X Lysis Buffer for 5 minutes, 2X High Salt Buffer for 5 minutes, 1X Wash Buffer for 5 minutes, and 1X TE (buffer recipes as in[62]). Samples were incubated with 100 μL elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) for 20 minutes at 70°C in a ThermoMixer F1.5 (Eppendorf). Input samples were brought up to 100 μL in TE with a final concentration of 1% SDS. Input and eluted samples were then incubated overnight in a 65°C water bath with 2.5 μL 2.5 mg/mL Proteinase K (Sigma Aldrich, Lot 58780500) for reverse crosslinking. Samples were purified with a PCR clean-up kit (Machery-Nagel) and eluted in 100 μL 10 mM Tris pH 8.0. The quality and size of the DNA were assessed by 4200 TapeStation instrument (Agilent). Next, libraries were prepared using Index Primer Set 1 (NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina, E7335L, Lot 10172541), Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (E7805L, Lot 10202083). The manufacturer’s protocol, “Protocol for FS DNA Library Prep Kit (E7805, E6177) with Inputs ≤100 ng (NEB)”, was used starting with 200 pg of DNA. PCR-enriched adaptor-ligated DNA was cleaned up using NEBNext sample purification beads (E6178S, Lot 10185312, “1.5. Cleanup of PCR Reaction” in manufacturer’s protocol). Individual adaptor-ligated DNA sample concentrations were quantified using a Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher), and the quality of the DNA was assessed by a 4200 TapeStation instrument (Agilent). Libraries were pooled to equimolar quantities and sequenced using a NextSeq 2000 P2 (400 million clusters) (Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco) (40bp read length, paired-end).

ChIP-seq data analysis

Sequencing adaptors were trimmed from raw sequencing reads using Trimmomatic v0.39. The S. pombe genome was downloaded from NCBI under Genome Assembly ASM294v2. The MAT locus of chromosome II was edited to our custom HSS MAT locus, and the genome was indexed using the bowtie2-build function of Bowtie2 v2.5.163. Trimmed sequencing reads were aligned to the genome using Bowtie2 v2.5.1 with flags [--local --very-sensitive-local --no-unal --no-mixed --no-discordant --phred33 -I 10 -X 700]64. Next, the resulting SAM files were converted to BAM files using SAMtools v1.1865 view function: -S -b ${base}.sam > ${base}.bam. The resulting BAM files were further processed by removing low-quality alignments, PCR duplicates, and multimappers, and retain properly aligned paired-end reads using SAMtools view with the following flags: -bh -F 3844 -f 3 -q 10 -@ 4. The processed BAM files were then sorted and indexed (SAMtools). Sorted, indexed BAM files were converted to bigWig coverage tracks using deepTools v3.5.466: bamCoverage: -b “$bam_file” -o “$filename_without_extension.bw” -binSize 10 --normalizeUsing CPM --extendReads --exactScaling --samFlagInclude 64 -effectiveGenomeSize 13000000. BigWig files normalized to input were generated using the bigwigCompare tool (deepTools). Normalized bigWig files were loaded into R v4.3.0 using rtracklayer v1.60.167 and processed for visualization as in Greenstein et al. 2022 with modifications. The Gviz v1.44.2 (Bioconductor) DataTrack function was used to create a visualization track of ChIP-seq signal in bigWig files for each genotype68. The Bioconductor GenomicRanges package was used to create a GRanges object to store custom genomic coordinates defined by a BEDfile69. Genomic annotations for signal tracks were created using the AnnotationTrack (Gviz) function. The GenomeAxisTrack (Gviz) function generated a visual reference (in megabases) to display the position of genomic annotations and signal tracks. Finally, the plotTracks (Gviz) function was used to plot the DataTrack, AnnotationTrack, and GenomeAxisTrack objects for visualization.

Swi6-GFP live cell imaging

Swi6-GFP/Sad1-mKO2 strains were struck out onto fresh YES 225 agar plates and incubated at 32°C for 3–5 days. Colonies were inoculated into liquid YES 225 medium (#2011, Sunrise Science Production) and grown in an incubator shaker at 30°C, 250 rpm to an OD of 0.2 −0.6. Cells were placed onto 2% agarose (#16500500, Invitrogen) pads in YES 225, covered with a coverslip (#2850–22, thickness 1 ½, Corning), and sealed with VALAP for imaging. Cells were imaged on a Ti-Eclipse inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments) with a spinning-disk confocal system (Yokogawa CSU-10) and a Borealis illumination system that includes 488nm and 541nm laser illumination and emission filters 525±25nm and 600±25nm respectively, 60X (NA: 1.4) objectives, and an EM-CCD camera (Hamamatsu, C9100–13). These components were controlled with μManager v. 1.4170,71. The temperature of the sample was maintained at 30°C by a black panel cage incubation system (#748–3040, OkoLab). The middle plane of cells was first imaged in brightfield and then two Z-stacks with a step size of 0.5μm were acquired in spinning-disk confocal mode with laser illumination 488nm and 541nm (total of 9 imaging planes per channel). The exposure, laser power, and EM gain for the Z-stacks were respectively 50ms / 1% / 800, and 200ms / 5% / 800. Between 9 and 12 fields of view were acquired per strain.

Image analysis

For each field of view, nuclei were manually cropped using Fiji. Cells containing multiple Sad1-mK02 foci were discarded from this analysis. For each selected nucleus TrackMate was used to determine the coordinates in space (X, Y, Z) of Sad1 and every Swi6 focus and their fluorescence intensity72,73. Using a custom script on Jupiter Notebook in Python we then automatically counted the number of Swi6 foci detected by TrackMate for each nucleus. Additionally, we automated the calculation of the distance between Swi6 foci and the spindle pole body by measuring the distance from each Swi6 focus to Sad1 within a given nucleus. For Swi6 intensity measurements, a region of interest (ROI) outside of each nucleus was automatically selected to measure the background intensity. This background intensity was then used to correct Swi6 fluorescence signal by subtracting the average intensity of this ROI for a given analyzed nucleus. Finally, we used a one-way ANOVA statistical test on Swi6 intensity signal to determine differences between mutants.

Protein cloning and purification

Wildtype swi6 open reading frame was cloned by ligation-independent cloning into vector 14B (QB3 Berkeley Macrolab expression vectors). Vector 14B encodes an N-terminal 6xHis tag followed by a TEV cleavage sequence. Wildtype Swi6 was expressed in BL21-gold (DE3) competent cells. To produce Swi6S18/24A, a gene block containing S18A/S24A Swi6 was cloned into vector 14B using Gibson assembly. To isolate pSwi6 and pSwi6S18/S24A, the respective vectors were co-expressed with the catalytic subunits of Caesin Kinase II in pRSFDuet. All three proteins were grown, harvested, and purified using a protocol adapted from [10] and modified as follows: Cells were grown at 37°C until OD600 0.5–0.6 and induced with a final concentration of 0.4mM Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside. Induced cells were grown at 18°C overnight. Harvested cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 1X PBS buffer pH 7.3, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Igepal CA-630, 7.5 mM Imidazole, 1 mM Beta-Mercaptoethanol (βME), with protease inhibitors. Resuspended cells were sonicated 2 seconds on /2 seconds off at 40% output power for three 5-minute cycles. The lysate was centrifuged at 25,000xg for 25 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. Nickel NTA resin was equilibrated with lysis buffer. The supernatant and resin were incubated for 1–2 hours and washed 3 times with 40 ml of lysis buffer each time before the protein was eluted with 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 400 mM Imidazole, and 1 mM βME. The eluted protein was then dialyzed in TEV cleavage buffer containing 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM βME and 6 mg TEV protease. The following morning 3–6 mg of TEV protease was spiked in for about 1 hour to ensure full cleavage. Nickel NTA resin was equilibrated with TEV cleavage buffer and the his-tagged TEV was captured by the resin while Swi6 protein was isolated by gravity flow. Cleaved protein was concentrated using a 10kDa MWCO concentrator and applied to a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL size exclusion column equilibrated in storage buffer containing 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, and 10 mM βME. Protein was concentrated, flash-frozen in N2 (liq), and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was quantified against a BSA standard curve on an SDS page gel and sypro red stain.

EDC/NHS crosslinking

unpSwi6 or pSwi6 was purified as described above. However, the storage buffer was 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 100 mM KCl for SEC-MALS. Protein, either 100 μM Swi6 or pSwi6, was incubated with 2 mM EDC and 5 mM NHS in a total volume of 95 μL for 2 hours. The reaction was quenched with a final concentration of 20 mM hydroxylamine.

Size-exclusion Chromatography coupled with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS)

Crosslinked and uncrosslinked Swi6 and pSwi6 were filtered with 0.2 μm spin columns (Pall Corporation, Ref. ODM02C34). For SEC, uncrosslinked and crosslinked proteins were injected onto a KW-804 silica gel chromatography column (Shodex) in a volume of 50 μL at 100 μM. The column was run using an ÄKTA pure FPLC (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and equilibrated with SEC-MALS storage buffer at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min and temperature of 8°C. The SEC column was connected in-line to a DAWN HELEOS II (Wyatt Technology) 18-angle light scattering instrument and an Optilab T-rEX differential refractive index detector (Wyatt Technology). Data was analyzed using ASTRA software (version 7.1.4.8, Wyatt Technology) and graphed using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.5.1).

Fluorescence Polarization

Fluorescence Polarization binding measurements were conducted as described in Canzio et al. 2013 and modified as follows:

Peptide reaction buffer was 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.01% NP-40, and 2 mM βME. Fluoresceinated H31–20 K9me0 or H31–20 K9me3 peptide concentration was fixed at 100 nM while Swi6, pSwi6, or pSwi6S18/24A protein concentration varied from 0–200 μM. Mononuclesome reaction buffer was 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 80 mM KCl, 4 mM Tris, 0.2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.01% NP-40, 2 mM βME. H3K9me0 and H3KC9me3 mononucleosomes were reconstituted with fluorescein-labeled 601 DNA as described12. Nucleosome concentration was fixed at 25 nM while Swi6, pSwi6, or pSwi6S18/24A protein concentrations varied from 0–200 μM. Both peptide and mononucleosome reaction volumes were 10 μL and measured in a Corning 384 low-volume, flat bottom plates (product number 3820, LOT 23319016). Fluorescence polarization was recorded using a Cytation 5 microplate reader (Biotek, λex= 485/20nm, λem= 528/20nm) and Gen5 software (Biotek, version 3.09.07). Data was analyzed and fit to a Kd equation using GraphPad Prism.

Single turnover kinetics

Clr4 protein was purified exactly as described23. H3K9me2 nucleosomes were purchased from Epicypher (#16–0324), and pSwi6 and unpSwi6 were purified as above. Single turnover reactions were carried out as follows: 5 μM Clr4 was preincubated 5 minutes with 1 mM final S-adenosyl-methionine (liquid SAM, 3 2mM, NEB #B9003S), and varying concentrations of pSwi6 or unP Swi6, at 25°C to reach equilibrium. 5μM Clr4 was chosen as the minimal Clr4 concentration to yield robust H3K9me3 signal under Single Turnover conditions. The reaction was started with the addition of H3K9me2 nucleosomes to 500nM final. Timepoints were stopped by boiling with SDS-Laemmli buffer. Samples were separated on 18% SDS-PAGE gel and probed for the presence of H3K9me3 (polyclonal, Active Motif #39161. lot 22355218–11) and H4 (Active Motif #39269 lot 31519002) as a loading control. Signals were quantified on a Li-Cor imager by using a dilution of H3K9me3 nucleosomes (Epicypher, #16–0315), establishing standard curves for H4 and H3K9me3. Rates were fit to a single exponential rise in GraphPad Prism software exactly as published23.

Phosphatase treatments

1500 ng of Swi6, pSwi6, and pSwi6S18/24A were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C with 50 U of Calf Intestinal Phosphatase (QuickCIP, NEB, M0525S) in 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.9. Reactions were stopped by boiling in SDS-Laemmli buffer. For reactions with inactivated CIP, 200U CIP was pre-incubated for 20 minutes at 80°C. 75 ng of Swi6, pSwi6, and pSwi6S18/24A that was either mock-treated, treated with active or inactivated CIP was separated on either a 15% SDS-PAGE gel or a SuperSep Phos-Tag gel (Fujifilm, 15.5%, 17 well, 100×100×6.6mm, Lot PAR5302). The Phos-Tag gel was washed with western transfer buffer with 10 mM EDTA to remove Zn2+ ions and then blotted and probed for Swi6 with Swi6 polyclonal antibody as above.

Mass Spectrometry

In-solution Trypsin/Lys C digested peptides were analyzed by online capillary nanoLC-MS/MS using several different methods. High resolution 1 dimensional LCMS was performed using a 25 cm reversed-phase column fabricated in-house (75 μm inner diameter, packed with ReproSil-Gold C18–1.9 μm resin (Dr. Maisch GmbH)) that was equipped with a laser-pulled nanoelectrospray emitter tip. Peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 300 nL/min using a linear gradient of 2–40% buffer B in 140 min (buffer A: 0.02% HFBA and 5% acetonitrile in water; buffer B: 0.02% HFBA and 80% acetonitrile in water) in a Thermo Fisher Easy-nLC1200 nanoLC system. Peptides were ionized using a FLEX ion source (Thermo Fisher) using electrospray ionization into a Fusion Lumos Tribrid Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data was acquired in orbi-trap mode. Instrument method parameters were as follows: MS1 resolution, 120,000 at 200 m/z; scan range, 350−1600 m/z. The top 20 most abundant ions were subjected to higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) or electron transfer dissociation (ETD) with a normalized collision energy of 35%, activation q 0.25, and precursor isolation width 2 m/z. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of 1, a repeat duration of 30 seconds, and an exclusion duration of 20 seconds.

Low-resolution, 1-dimensional LCMS was performed using a nano-LC column packed in a 100-μm inner diameter glass capillary with an integrated pulled emitter tip. The column consisted of 10 cm of ReproSil-Gold C18–3 μm resin (Dr. Maisch GmbH)). The column was loaded and conditioned using a pressure bomb. The column was then coupled to an electrospray ionization source mounted on a Thermo-Fisher LTQ XL linear ion trap mass spectrometer. An Agilent 1200 HPLC equipped with a split line so as to deliver a flow rate of 1 ul/min was used for chromatography. Peptides were eluted with a 90-minute gradient from 100% buffer A to 60% buffer B. Buffer A was 5% acetonitrile/0.02% heptafluorobutyric acid (HBFA); buffer B was 80% acetonitrile/0.02% HBFA. Collision-induced dissociation spectra were collected for each m/z. Multidimensional protein identification technique (MudPIT) was performed as described74,75. Briefly, a 2D nano-LC column was packed in a 100-μm inner diameter glass capillary with an integrated pulled emitter tip. The column consisted of 10 cm of ReproSil-Gold C18–3 μm resin (Dr. Maisch GmbH)) and 4 cm strong cation exchange resin (Partisphere, Hi Chrom). The column was loaded and conditioned using a pressure bomb. The column was then coupled to an electrospray ionization source mounted on a Thermo-Fisher LTQ XL linear ion trap mass spectrometer. An Agilent 1200 HPLC equipped with a split line so as to deliver a flow rate of 1 ul/min was used for chromatography. Peptides were eluted using a 4-step gradient with 4 buffers. Buffer (A) 5% acetonitrile, 0.02% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA), buffer (B) 80% acetonitrile, 0.02% HFBA, buffer (C) 250mM NH4AcOH, 0.02% HFBA, (D) 500mM NH4AcOH, 0.02% HFBA. Step 1: 0–80% (B) in 70 min, step 2: 0–50% (C) in 5 min and 0– 45% (B) in 100 min, step 3: 0–100% (C) in 5 min and 0– 45% (B) in 100 min, step 4 0–100% (D) in 5 min and 0–45% (B) in 160 min. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra were collected for each m/z. Data analysis: RAW files were analyzed using PEAKS (Bioinformatics Solution Inc) with the following parameters: semi-specific cleavage specificity at the C-terminal site of R and K, allowing for 5 missed cleavages, precursor mass tolerance of 15 ppm (3 Da for low-resolution LCMS), and fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.5 Daltons. Methionine oxidation and phosphorylation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine were set as variable modifications and Cysteine carbamidomethylation was set as a fixed modification. Peptide hits were filtered using a 1% false discovery rate (FDR). Phosphorylation occupancy ratio for amino acids was determined by summing the count of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated amino acids detected in the experiment. We only considered phospho-peptides detected more than once and at least 2% minimal ion intensity.

Estimate of in vivo nucleosome fractions bound

In vitro binding isotherms for nucleosomes (N) can be fit simply via . However, this assumes first that and , such that [Swi6] total ≈ [Swi6] free. In the nucleus, these assumptions do not hold. However, a quadratic equation48 can be used to estimate N bound, accounting for bound Swi6. In this case, . To estimate the fraction of unmethylated nucleosomes bound by pSwi6 or unpSwi6, we used from Figure 4F, total Swi6 concentrations of 2.1–4.6μM, and total nucleosome contraction estimate of ~10μM.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Figure 1: Additional isolates demonstrating that S18 and S24 in Swi6 are required for spreading, but not nucleation of heterochromatin silencing. 2-D Density hexbin plots examining silencing at nucleation “green” and spreading “orange” reporter in the MAT ΔREIII HSS for three additional isolates of A.-C. swi6S18/24A mutants, C.-F. swi6S46/5/117−220A (“S18/24 available”), and G.-I. swi6S46/52A. J-L. As A.-I. but for the Δckb1 mutant. An independent wild-type isolate from the cross is shown alongside 2 Δckb1 isolates.

Supporting Figure 2: H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 ChIP-seq plots in additional genomic loci in wild-type or swi6S18/24A A. H3K9me2 (TOP) and H3K9me3 (BOTTOM) plots as in Figure 2 at mei4 for wild-type and swi6S18/24A. B. H3K9me2 (TOP) and H3K9me3 (BOTTOM) plots as in Figure 2 at tel IL for wild-type and swi6S18/24A. B. H3K9me2 (TOP) and H3K9me3 (BOTTOM) plots as in Figure 2 at tel IIL for wild-type and swi6S18/24A.

Supporting Figure 3: Characterization of recombinant pSwi6 A. Size Exclusion Chromatography followed by Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) on uncrosslinked unpSwi6 (black) and pSwi6 (green). Relative refractive index signals (solid lines, left y-axis) and derived molar masses (lines over particular species, right y-axis) are shown as a function of the elution volume. A migration shift is apparent in pSwi6, as well as a small shoulder of higher molecular weight species (arrow). B. Calf Intestine Phosphatase (CIP) treatment of Swi6 examined in a 15% SDS-PAGE gel. unpSwi6, pSwi6, or pSwi6S18/24A were treated with (+) or without (−) CIP or with heat-inactivated CIP (b). C. CIP treatment of Swi6 examined in a Phos-Tag gel as in A. Blots of both gels were probed with an anti-Swi6 polyclonal antibody. D. Mass Spectrometry on pSwi6S18/24A. Shown is a domain diagram of Swi6S18/24A. Phosphorylation sites identified in pSwi6 S18/24A by 2D-ETD-MS are indicated and grouped by detection prevalence in the sample.

Supporting Figure 4: Analysis of Swi6-GFP heterochromatin foci number and spatial distribution. A. Strategy for production of GFP-tagged swi6 S-A mutants in the sad1:mKO2 background. The wildtype swi6 or S-A mutant gene from Figure 2A was cut with CRISPR/Cas9, and the break was repaired with a cassette containing a super-folder GFP, swi6 3’ sequence homology, and a HygMX cassette. B. Representative maximum projection live microscopy images of indicated Swi6S46/52A-GFP /Sad1-mKO2 compared to the wild-type strain. C. Quantification of Swi6-GFP signals by flow cytometry. The GFP signal of independent wild-type or S-A mutant isolates compared to GFP- cells as measured by flow cytometry. D. Distribution of nuclear foci in nuclei of indicated strains represented as relative frequency. Wt Swi6-GFP, n=85; Swi6S18/24A-GFP, n=94; Swi6S18/24/117-220A-GFP, n=50; Swi6S46/52/117-220A-GFP, n=82. E. distribution of Swi6-GFP heterochromatin foci relative to Sad1-mKO2. overview: center-to-center distances were measured in 3D from the peri-spindle pole body Sad1-mKO2 signal to all Swi6-GFP foci identified in each nucleus. F. relative frequency histogram binning the distribution of Sad1-mKO2 to Swi6-GFP foci distances in indicated strains.

Supporting Figure 5: Additional replicates of Swi6 westerns from cell lysates and nucleosome trimethylation. A. Independent repeat of α-Swi6 and α-S18P-S24P westerns as in Figure 4A. B. A repeat of quantitative western blots querying time-dependent formation of H3K9me3 from H3K9me2 mononucleosomes in the presence of pSwi6 or unpSwi6 (0 and 5μM Swi6). C. A repeat of quantitative western blots querying time-dependent formation of H3K9me3 from H3K9me2 mononucleosomes in the presence of pSwi6 or unpSwi6 (15μM and 30μM Swi6). B and C. Swi6 concentration time courses were collected at the same time; westerns were run on separate days.

Table 2.

Table of S. pombe strains used in this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Geeta J. Narlikar for the discussion on theory and critical feedback on the manuscript. We thank Sigurd Braun, Daniele Canzio, and Lucy D. Brennan for valuable feedback and discussion. B.A-S. was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant R35GM141888 and a National Science Foundation grant 2113319. D.R.K. and C.T. were supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowships Grant No. 2034836. E.S. was supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation and National Institutes of Health supplement DP2GM123484-01S1. We acknowledge the UCSF PFCC (RRID:SCR_018206) for assistance in generating Flow Cytometry data. The research reported here was supported in part by the DRC Center Grant NIH P30 DK063720. We thank the Southworth lab for access and training to SEC-MALS equipment.

Data availability statement:

ChIP-Seq data is deposited at NIH GEO Record GSE271394

REFERENCES

- 1.Grewal S. I. S. The molecular basis of heterochromatin assembly and epigenetic inheritance. Mol. Cell 83, 1767–1785 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamali B., Amine A. A. A. & Al-Sady B. Regulation of the heterochromatin spreading reaction by trans-acting factors. Open Biol. 13, 230271 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elgin S. C. & Reuter G. Position-effect variegation, heterochromatin formation, and gene silencing in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5, a017780 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang K., Mosch K., Fischle W. & Grewal S. I. S. Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15, 381–8 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller M. M., Fierz B., Bittova L., Liszczak G. & Muir T. W. A two-state activation mechanism controls the histone methyltransferase Suv39h1. Nat Chem Biol 12, 188–93 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noma K. et al. RITS acts in cis to promote RNA interference-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional silencing. Nat Genet 36, 1174–80 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall I. M. et al. Establishment and maintenance of a heterochromatin domain. Science 297, 2232–2237 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs S. A. & Khorasanizadeh S. Structure of HP1 chromodomain bound to a lysine 9-methylated histone H3 tail. Science 295, 2080–3 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haldar S., Saini A., Nanda J. S., Saini S. & Singh J. Role of Swi6/HP1 self-association-mediated recruitment of Clr4/Suv39 in establishment and maintenance of heterochromatin in fission yeast. J Biol Chem 286, 9308–20 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenuwein T. & Allis C. D. Translating the histone code. Science 293, 1074–80 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aagaard L., Schmid M., Warburton P. & Jenuwein T. Mitotic phosphorylation of SUV39H1, a novel component of active centromeres, coincides with transient accumulation at mammalian centromeres. J. Cell Sci. 113 (Pt 5), 817–829 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canzio D. et al. Chromodomain-mediated oligomerization of HP1 suggests a nucleosome-bridging mechanism for heterochromatin assembly. Mol. Cell 41, 67–81 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson A. G. et al. Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547, 236–240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanulli S. & J Narlikar G. Liquid-like interactions in heterochromatin: Implications for mechanism and regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 64, 90–96 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keenen M. M. et al. HP1 proteins compact DNA into mechanically and positionally stable phase separated domains. eLife 10, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strom A. R. et al. Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature 547, 241–245 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanulli S. et al. HP1 reshapes nucleosome core to promote phase separation of heterochromatin. Nature 575, 390–394 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holla S. et al. Positioning Heterochromatin at the Nuclear Periphery Suppresses Histone Turnover to Promote Epigenetic Inheritance. Cell 180, 150–164.e15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer T. et al. Diverse roles of HP1 proteins in heterochromatin assembly and functions in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 8998–9003 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verschure P. J. et al. In vivo HP1 targeting causes large-scale chromatin condensation and enhanced histone lysine methylation. Mol Cell Biol 25, 4552–64 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller C. et al. HP1(Swi6) Mediates the Recognition and Destruction of Heterochromatic RNA Transcripts. Mol. Cell 47, 215–27 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motamedi M. R. et al. HP1 proteins form distinct complexes and mediate heterochromatic gene silencing by nonoverlapping mechanisms. Mol. Cell 32, 778–90 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Sady B., Madhani H. D. & Narlikar G. J. Division of labor between the chromodomains of HP1 and Suv39 methylase enables coordination of heterochromatin spread. Mol. Cell 51, 80–91 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akoury E. et al. Disordered region of H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4 binds the nucleosome and contributes to its activity. Nucleic Acids Res 47, 6726–6736 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canzio D. et al. A conformational switch in HP1 releases auto-inhibition to drive heterochromatin assembly. Nature 496, 377–81 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirai A. et al. Impact of nucleic acid and methylated H3K9 binding activities of Suv39h1 on its heterochromatin assembly. Elife 6, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimada A. et al. Phosphorylation of Swi6/HP1 regulates transcriptional gene silencing at heterochromatin. Genes Dev 23, 18–23 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eissenberg J. C., Ge Y. W. & Hartnett T. Increased phosphorylation of HP1, a heterochromatin-associated protein of Drosophila, is correlated with heterochromatin assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 21315–21321 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeRoy G. et al. Heterochromatin Protein 1 Is Extensively Decorated with Histone Code-like Post-translational Modifications*. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 2432–2442 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishibuchi G. et al. N-terminal phosphorylation of HP1alpha increases its nucleosome-binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 12498–511 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao T., Heyduk T. & Eissenberg J. C. Phosphorylation site mutations in heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) reduce or eliminate silencing activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9512–9518 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenstein R. A. et al. Local chromatin context regulates the genetic requirements of the heterochromatin spreading reaction. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010201 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenstein R. A. et al. Noncoding RNA-nucleated heterochromatin spreading is intrinsically labile and requires accessory elements for epigenetic stability. eLife 7, e32948 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Donoghue L. & Smolenski A. Analysis of protein phosphorylation using Phos-tag gels. J. Proteomics 259, 104558 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jih G. et al. Unique roles for histone H3K9me states in RNAi and heritable silencing of transcription. Nature (2017) doi: 10.1038/nature23267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada T., Fischle W., Sugiyama , T., Allis C. D. & Grewal S. I. S. The nucleation and maintenance of heterochromatin by a histone deacetylase in fission yeast. Mol. Cell 20, 173–85 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]