Abstract

Locomotion is continuously regulated by an animal’s position within an environment relative to goals. Direct and indirect pathway striatal output neurons (dSPNs and iSPNs) influence locomotion, but how their activity is naturally coordinated by changing environments is unknown. We found, in head-fixed mice, that the relative balance of dSPN and iSPN activity was dynamically modulated with respect to position within a visually-guided locomotor trajectory to retrieve reward. Imbalances were present within ensembles of position-tuned SPNs which were sensitive to the visual environment. Our results suggest a model in which competitive imbalances in striatal output are created by learned associations with sensory input to shape context dependent locomotion.

The striatum, the principal input nucleus of the basal ganglia, integrates convergent sensory and motor signals arising from cortical and sub-cortical regions. Striatal spiny projection neurons (SPNs) are thought to transform sensory input to influence the expression, direction, and vigor of ongoing action in specific sensory contexts1–5. However, the basic principles and network dynamics underlying this role remain unresolved. SPNs can be sub-divided into two major classes, direct and indirect pathway SPNs (dSPNs and iSPNs respectively), based on molecular expression profiles and downstream projection targets6–8. Classic models of the basal ganglia posit that dSPNs promote or invigorate movement (‘go’), while iSPNs suppress or slow movement (‘no-go’)9,10. The opponent framework has received support from Parkinsonian models and some pathway specific manipulations11–16, though other manipulation studies have provided conflicting evidence17,18. Neural recording studies have revealed that dSPNs and iSPNs are similarly activated at movement initiations19–27, challenging the simple go-no go model and suggesting that the natural activity of dSPNs and iSPNs may cooperate to drive movement by promoting selected actions and suppressing competing actions respectively1. An alternative model, also consistent with the co-activation results, is that dSPNs and iSPNs activated during movement compete to promote or suppress the same action respectively28. In this model, both cell-types are activated by similar inputs during movement execution, but the relative levels of activation modulate whether the action is initiated and sustained or suppressed. Simultaneous cellular resolution imaging of dSPNs and iSPNs has reported similar population activation levels at locomotion onsets and offsets and during spontaneous running19,21, seemingly in conflict with the competitive model. However, bulk calcium measurements have reported dSPN/iSPN imbalances related to whether spontaneous turning behaviors are executed or suppressed29 and during the execution of specific spontaneous movements30. Importantly, prior studies of cell-type specific SPN signaling have been conducted either with non-simultaneous dSPN/iSPN measurements, precluding direct activity level comparisons, or in task conditions where animals’ movements were not explicitly sensory guided. Therefore, it remains unresolved whether and how imbalances in dSPN and iSPN activity arise and how ongoing task-specific input influences these imbalances at cellular and population levels.

To address these questions, we utilized 2-photon calcium imaging to simultaneously measure dSPN and iSPN activity with cellular resolution as head-fixed mice ran through virtual environments to obtain reward. D1-tdTomato mice31 (n = 5) were injected in the dorsal (primarily central-medial, see Methods) striatum with AAVs to drive pan neuronal expression of the green calcium indicator GCaMP7f32, and were implanted with a chronic imaging window33 (Fig. 1a). This approach yielded simultaneous Ca2+ activity measurements within populations of identified (tdTomato +) dSPNs and putative (tdTomato -) iSPNs (Fig. 1b). Mice were head-fixed on an axial treadmill and their locomotion velocity was translated into corresponding movement of a visual virtual reality (VR) environment projected onto an array of monitors34 (Fig. 1c). Training was performed on a linear track task in which mice initiated locomotion and ran through a virtual corridor with proximal and distal visual cues to receive a water reward delivered through a spout (Fig. 1c). Mice exhibited stereotyped patterns of locomotion across the track in which they rapidly accelerated at the start and slowed down prior to reaching the reward zone (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). Running patterns were often highly consistent within a session but varied somewhat across sessions and mice (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Anticipatory licking was sometimes observed in a short window prior to reward delivery (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Thus, mice displayed behavioral patterns indicating learned associations between locomotion kinematics and position relative to reward.

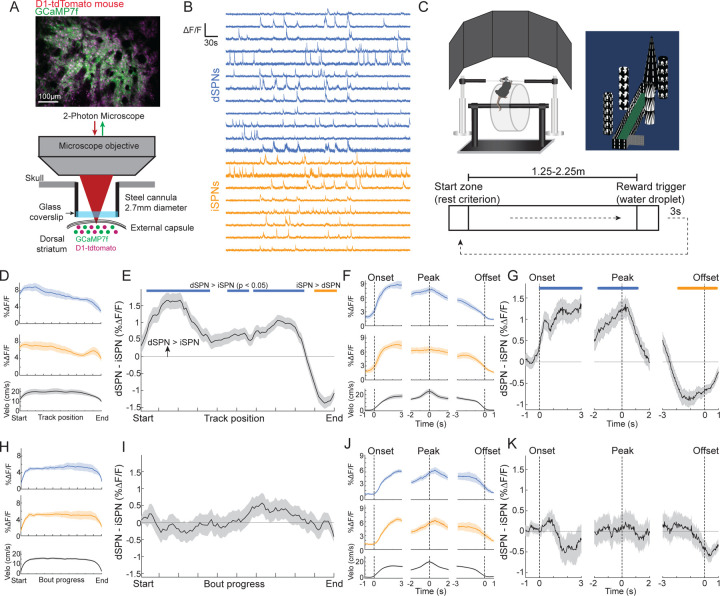

Figure 1: Dynamic imbalances in the activity of striatal projection neuron cell types during stereotyped locomotion in a virtual linear track task.

A.) Schematic of the 2-photon imaging approach for simultaneous cellular resolution Ca2+ imaging of dSPNs and iSPNs in the dorsal striatum of head-fixed mice. B.) Fluorescence traces (min-max normalized ΔF/F) from dSPNs and iSPNs in a representative field. C.) Schematic of the head-fixed virtual reality setup and linear track task design. D.) Mean ΔF/F of dSPNs (blue, n = 1551), iSPNs (orange, n = 2057), and treadmill velocity (black) from 5 mice and 36 sessions binned by position along the linear track. E.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F between dSPNs and iSPNs binned by track position. Blue lines indicate bins where dSPN ΔF/F>iSPN, orange lines iSPN>dSPN (p < 0.05, t-tests on model coefficients, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). F.) Mean ΔF/F and velocity as in D, triggered on onsets, offsets, and the peak velocity of locomotion bouts during VR track traversal. G.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F as in E, triggered on locomotion periods as in F. H.) Mean ΔF/F of dSPNs (blue, n = 1680), iSPNs (orange, n = 2746), and velocity (black) from 3 mice and 35 sessions for spontaneous locomotion bouts occurring outside of VR, binned by relative bout progress normalized to the distance of each bout. I.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F between dSPNs and iSPNs (as in E) binned by normalized bout progress outside VR. J.) Mean ΔF/F and velocity as in H, triggered on onsets, offsets, and the peak velocity of locomotion bouts during spontaneous locomotion bouts outside of VR. K.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F as in I, triggered on accelerations as in J. Shaded regions in all plots are the 95% confidence intervals of the model coefficients from the linear mixed effect model (see Methods).

We first examined how the population activity of dSPNs and iSPNs was modulated during track traversal. Consistent with previous findings in head-fixed and freely moving mice19,21,22,24, the mean activity (ΔF/F) of both populations increased as mice initiated locomotion at the start of the track and decreased as they slowed down near the end (Fig. 1d,f and Extended Data Fig. 1d). Mean ΔF/F in the middle of the track, when animals were maintaining high velocity running, was also significantly elevated in both populations. Unlike prior studies in which distinct cell populations were measured in separate groups of mice, our simultaneous imaging approach enabled us to directly compare relative dSPN and iSPN population activity to determine whether output was balanced. Surprisingly, we found that despite qualitatively similar activity patterns relative to track position and locomotion kinematics, the relative balance between dSPN and iSPN activity was dynamically modulated during track traversal. dSPN activity at the beginning and throughout the middle of the track was significantly higher than iSPN activity, but the balance flipped to favor iSPNs near the end of the track (Fig. 1e,g and Extended Data Fig. 1e). The emergence of the dSPN imbalance at the track start was aligned with the onset of locomotion, and the flip to an iSPN imbalance appeared at the offset of locomotion, just prior to the animals stopping at the end (Fig. 1g). Thus, the relative balance of dSPN and iSPN output is dynamically modulated with respect to animals’ locomotor kinematics and position through a learned trajectory to obtain reward.

To test whether the dSPN/iSPN imbalances were purely related to locomotion or whether they were shaped by the linear track task, we asked whether similar imbalances were present during spontaneous locomotion when the linear track VR environment was turned off. Outside VR, mice spontaneously initiated and terminated locomotion. We selected locomotion bouts of comparable length and velocity to trials in VR and calculated the relative dSPN and iSPN activity balance as a function of relative bout progress. Like locomotion bouts in VR, activity in both populations increased at the onset of bouts, decreased at the offset, and was elevated during sustained locomotion (Fig. 1h,j and Extended Data Fig. 1f). However, in contrast to the VR track, there was no average significant imbalance in the dSPN/iSPN population activity during any phase of locomotion bouts (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 1g). No significant imbalance was present at spontaneous bout onsets or during sustained locomotion (Fig. 1k). Furthermore, a larger number of both dSPNs and iSPNs were active inside VR than outside, and higher overall activity was observed in the active populations, suggesting that SPNs receive stronger excitatory drive in the VR environment, perhaps reflecting visual input or other task representations (Extended Data Fig. 1h–k). This was not due to differences in locomotion between VR and no VR periods, as activity differed across the entire range of velocities (Extended Data Fig. 1h). In summary, these results indicate that dynamic dSPN/iSPN imbalances observed during track traversal were shaped by position within the continuously changing VR task environment.

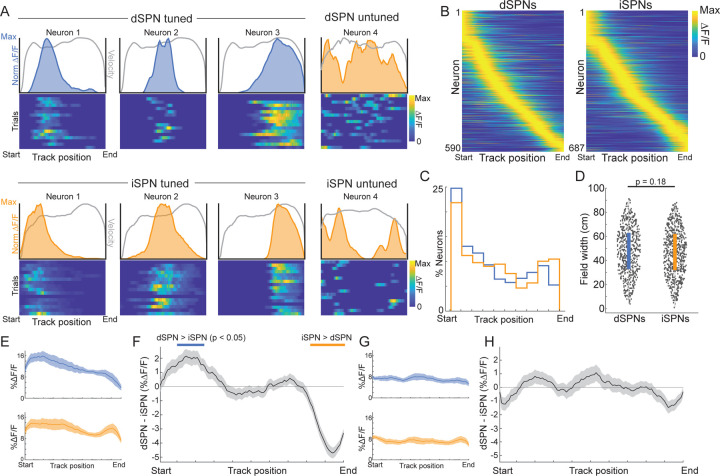

We next asked how dSPN/iSPN imbalances at the population level were generated through activity in single neurons. Imbalances varied with position along the track, so we tested whether individual SPNs represented discrete track positions. Individual dSPNs (590/1812 neurons, 32.56%) and iSPNs (687/2645 neurons, 25.97%) displayed large Ca2+ transients consistently at the same track location across trials, indicating significant encoding of discrete track positions (Fig. 2a,b, see Methods). Significant position encoding dSPNs and iSPNs had activity field peaks tiling positions along the entire track, consistent with prior observations of task tiling in SPNs of rodents and primates35–38 (Fig. 2b–d). For both populations, the largest fraction of neurons had fields near the beginning of the track (Fig. 2c). There was a slight, but non-significantly, larger proportion of dSPNs than iSPNs with fields at the beginning of the track, and a larger proportion of iSPNs than dSPNs at the end of the track (Fig. 2c, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p = 0.07). Mean field widths were similar, on average, for iSPNs and dSPNs (Fig. 2d, Wilcoxon rank sum test, p = 0.18). Strikingly, the dSPN/iSPN imbalances observed at the population level (Fig. 1e) were only present for the position tuned subpopulations (Fig. 2e–f). dSPN/iSPN output was balanced across the track for the active un-tuned population (Fig. 2g–h). Thus, dynamic SPN imbalances are generated by cell ensembles representing discrete track positions tiling the entire locomotor trajectory to reach the goal.

Figure 2: Dynamic imbalances originate from a subpopulation of position selective SPNs that collectively tile the linear track environment.

A.) Representative dSPNs (top) and iSPNs (bottom) with and without significant track position tuning across trials in a session (see Methods). Color plots are ΔF/F on each trial, binned by track position, normalized to the max ΔF/F across all trials. Shaded blue (dSPNs) and orange (iSPNs) regions above the color plots are the mean ΔF/F for each position. The overlaid gray lines are the mean normalized position binned velocities. B.) Mean ΔF/F binned by track position for all dSPNs (left) and iSPNs (right) classified as having stable track position tuning across trials (see Methods) normalized by the max ΔF/F for each neuron. Neurons are sorted by the positions of the maximum ΔF/F from track start to end. C.) Percent of the total position tuned population of dSPNs (blue) and iSPNs (orange) with a maximum ΔF/F at each position across the virtual track. D.) Boxplot of median field widths of all position tuned SPNs. Each dot is a single SPN. E.) Mean ΔF/F of stable, position-tuned dSPNs (blue, n = 590) and iSPNs (orange, n = 687) from 5 mice and 36 sessions binned by position along the linear track. F.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F between the dSPNs and iSPNs in E binned by track position. Blue lines indicate bins where dSPN ΔF/F > iSPN, orange lines iSPN>dSPN (p < 0.05, t-tests on model coefficients, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). G.) Same as E for active neurons without significant position tuning (n = 406 dSPNs, and 447 iSPNs). P-values, Wilcoxon rank sum test. Shaded regions in all plots are the 95% confidence intervals of the fitted model coefficients from the linear mixed effect model (see Methods).

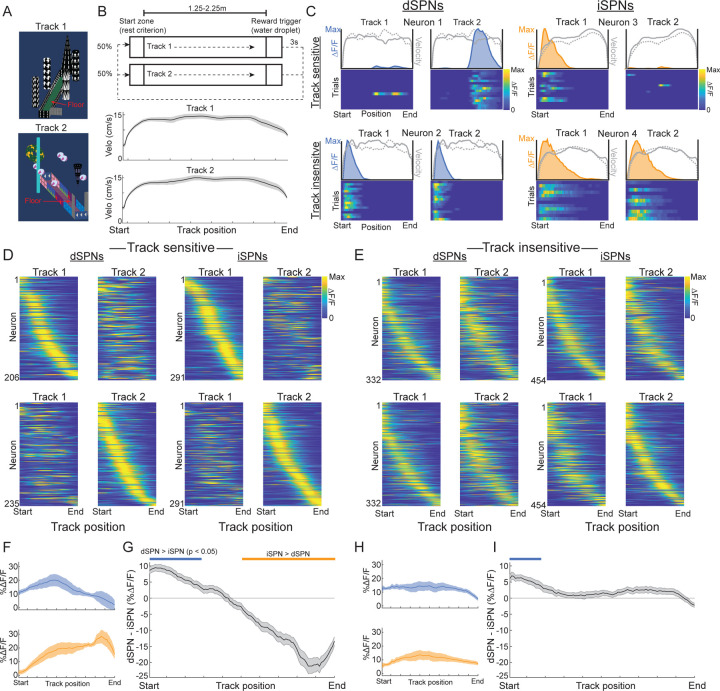

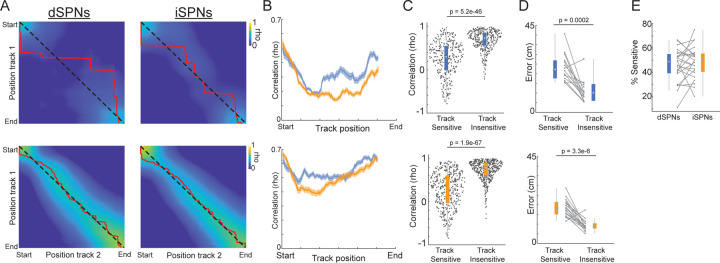

To determine whether the visual environment contributed to position tuning, we examined differences in SPN activity between two familiar, visually distinct virtual tracks (Fig. 3a,b). For each session, mice were pseudorandomly placed in one of the two track environments on each trial. Velocity and acceleration at each position were highly similar between the two tracks (Fig. 2b), allowing us to isolate the influence of the visual input on position specific tuning. Position tuned SPNs of both types were sensitive to the visual environment (333/665 and 437/891 position tuned dSPNs and iSPNs respectively, see Methods), with some significantly tuned in only one track, and others consistently active at different positions within each track (Fig. 3c,d). Other position tuned neurons displayed similar tuning between the two tracks (332/665 and 454/891 position tuned dSPNs and iSPNs respectively), indicating insensitivity to the visual environment (Fig. 3c,e). Correlations between activity on the two tracks were highest at the track start for both cell types, perhaps reflecting stable representations of movement initiation (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). Large imbalances in relative dSPN/iSPN activity were present in the position tuned, track sensitive population, with dSPNs more active in the first half of the track and the iSPNs more active in the second half (Fig. 3f,g), similar to the average imbalances across the whole population (Fig. 1e). However, significant imbalances in the track insensitive population were smaller and only present at the track start (Fig. 3i). These results indicate that dynamic dSPN/iSPN imbalances arise largely from a population of SPNs tuned to discrete positions within specific visual environments.

Figure 3: Subpopulations of position tuned SPNs differ in their sensitivity to environment specific visual input and in their cell-type specific activity imbalances.

A.) Top-down images of the two virtual tracks with distinct distal and proximal features. B.) Task schematic (top) and mean velocity (bottom) binned by track position in the two tracks across all mice and sessions (n = 4 mice and 23 sessions). C.) Representative position tuned dSPNs (left) and iSPNs (right) with tuning that is sensitive (top) or insensitive (bottom) to the visual track environment. Color plots are ΔF/F on each trial, binned by track position, normalized to the maximum ΔF/F across all trials. Shaded blue (dSPNs) and orange (iSPNs) regions above the color plots are the normalized mean ΔF/F for each position. Overlaid gray lines are the normalized position binned velocity; solid line is track 1 and dashed line is track 2. D.) Mean ΔF/F binned by position in each track for all dSPNs (left) and iSPNs (right) classified as having track-sensitive position tuning across trials (see Methods) normalized by the maximum ΔF/F for each neuron across both tracks. Neurons are sorted by the positions of the mean ΔF/F peaks from track start to end. Top row plots are sorted by peak position indices in track 1, bottom row, track 2. Only neurons with significant position tuning in track 1 are shown in top and in track 2 on bottom. Note that the organization of peak tuning locations across neurons and relative ΔF/F magnitudes differ between tracks. E.) Same as D but for neurons with track insensitive position tuning. Note that the organization of peak tuning and ΔF/F magnitudes are relatively similar between tracks. F.) Mean ΔF/F of position-tuned, track sensitive dSPNs (blue, n = 132) and iSPNs (orange, n = 260) from 3 mice and 14 sessions binned by position along the linear track (see Methods for inclusion criteria). G.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F between the dSPNs and iSPNs in F binned by track position. Blue lines indicate bins where dSPN ΔF/F > iSPN, orange lines iSPN>dSPN (p < 0.05, t-tests on model coefficients, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons). H-I.) Same as F-G for position-tuned, non-track sensitive dSPNs (blue, n = 183) and iSPNs (orange, n = 205) from 3 mice and 14 sessions. Shaded regions in all plots are the 95% confidence intervals of the fitted model coefficients from the linear mixed effect model (see Methods).

Overall, our results show that imbalances in cell-type specific dorsal striatal output are shaped by visual input at discrete positions within locomotor trajectories towards a goal. The imbalances aligned, on average, with animals’ locomotor kinematics, with dSPNs favored at positions where animals initiated and sustained locomotion and iSPNs favored when animals slowed down. These results indicate that imbalances within discrete position encoding SPN ensembles may reflect learned associations between dynamic sensory input and locomotor kinematics. In further support of this, imbalances did not exist (or were weaker) when no consistent sensory-locomotion associations were present (outside VR, Fig. 1h–k and Extended Data Fig. 1f,g) or in SPN populations that were not position tuned and environment sensitive (Figs. 2g,h and 3h,i). These results may, in part, explain why imbalances have not been observed in previous studies in head-fixed mice during spontaneous locomotion19 but have been reported in bulk dSPN/iSPN measurements in freely moving mice29,30.

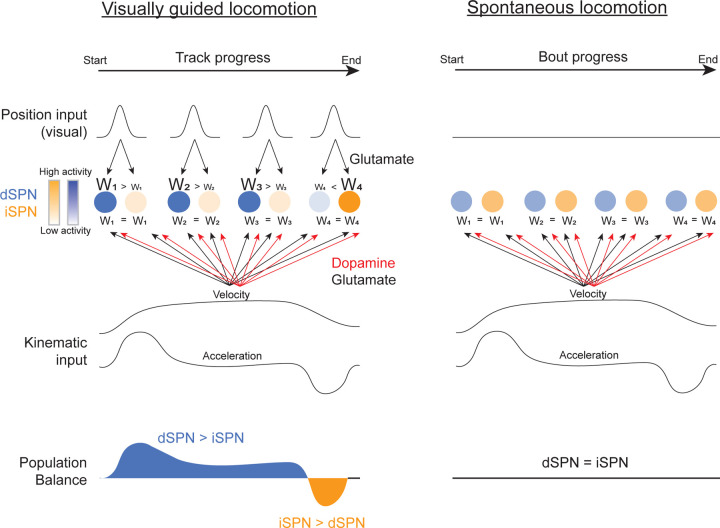

We hypothesize that dSPNs and iSPNs activated by similar patterns of sensory input compete to modulate stereotyped, context-dependent locomotion following repeated experience with an environment. In this view, dSPN/iSPN imbalances within ensembles of position encoding SPNs are established through learning via bi-directional changes in synaptic weights of excitatory synapses (Extended Data Fig. 3). Weights of sensory inputs corresponding to positions where animals initiate or sustain high velocity locomotion are stronger onto dSPNs, while weights associated with low velocity or deceleration are stronger onto iSPNs. Thus, the dSPN/iSPN imbalance at each position is determined by associations between visual input and locomotor kinematics. How might synaptic weights be adjusted to establish sensory driven imbalances? One possibility is through dopamine release, which can modulate opposing cell-type specific potentiation and depression of dSPN and iSPN synapses respectively39,40. Dopamine release in the dorsal striatum rapidly increases and decreases during locomotion accelerations and decelerations respectively33,41,42. These signals could drive plasticity of sensory inputs to SPNs as a function of locomotor kinematics, independently of dopamine release at reward, to promote stereotypic sensory driven movement patterns leading to goals.

Methods:

Animals

Adult male Drd1a-tdTomato mice31 (Jackson Labs, strain# 016204, n = 6 mice, postnatal 10–17 weeks, 24–30g) were used for all experiments. Mice were initially housed in groups and then individually housed following surgery under standard laboratory conditions (20–26°C, 30–70% humidity; reverse 12-h/12 h light/dark cycle; light on at 9 p.m.) with ad libitum access to food and water, except during water scheduling. During training and imaging, the mice were single housed with a water restriction schedule to receive ~1mL water each day. The amount of water was adjusted to maintain a body weight 80–90% of the initial body weight. Five mice were trained and imaged on the VR linear track task, three were imaged during spontaneous running outside of VR, and two were imaged in both. Experiments were conducted during the dark cycle. All animal care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 201800554) and in compliance with the Guide for Animal Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Stereotaxic virus injections and imaging window implants

Mice underwent two separate stereotaxic surgeries, first for intracranial virus injections, then for chronic window implantation for 2-photon imaging. For virus injections, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (3% induction, 1-2% maintenance) then positioned in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf), and a craniotomy was drilled over the dorsal striatum. Intracranial injections of AAVs carrying the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP7f32 (Addgene, AAV1-hSyn-GCaMP7f, 3×10^13 GC/mL diluted 1:4 in PBS) were performed with a 33g Hamilton Neuro Syringe (#65460-02; Hamilton Company) connected to a Micro Syringe Pump Controller (UMP3 and UMC4; WPI). Each mouse received injections at 4 sites ranging from −1.6 to −1.8mm in the DV plane, 1.8–2.2mm in ML, and 0.4–0.6mm in AP each with 300 nL virus solution at a rate of 100nL per minute. The craniotomy was then sealed with Kwik-Sil (WPI) and the exposed skull was covered in thick Metabond (Parkell) to secure a metal headplate33, allowing for pre-training on linear track task (Fig. 1, see below) prior to window implants. 9–14 days after virus injections, mice underwent surgeries for chronic imaging window implantation as described in Howe and Dombeck, 201633. Briefly, the headplate was removed under anesthesia, and the craniotomy cleaned. A circular drill bit (FST #18004-27) attached to a stereotaxic drill (Foredom K.1070 Micromotor Kit) was used to partially widen the existing craniotomy then the bone was further thinned with a hand held dental drill (Midwest Tradition 790044, Avtec Dental RMWT) and removed with a forceps. The cortical tissue overlying the striatum was carefully aspirated under a surgical microscope (Leica) until the external capsule fibers were visible. The external capsule fibers were thinned, and in some mice, the striatum surface was exposed, but no striatum tissue was removed. A very thin layer of Kwik-Sil was then applied to the brain surface, and the imaging window was inserted. Windows attached to metal cannulae (2.7mm diameter) were made in house as previously described33. Metabond was applied around the edges of the cannula and over the entire exposed skull to re-secure the metal headplate. A metal ring was centered over the window and secured to the skull and headplate with Metabond blackened with carbon powder (Sigma). Stickers were placed in the ring to keep debris off the window outside of imaging sessions.

Two-photon imaging

Imaging was performed using a resonance scanning 2-photon microscope (Neurolabware, Scanbox) with 20x (UMPLFLN, 20X, 0.5 NA) or 40x (Olympus LUMPlanFL N, 40X, 0.8 NA) objectives. Excitation light was supplied by an InsightX3 laser (Spectra Physics). Field of view sizes were 750 × 900 microns for the 20x objective and 400 × 575 microns for the 40x. GCaMP7f was imaged with 920nm excitation light at 31Hz within 1-2 imaging fields for a total of 30–70 minutes per day. Light power was adjusted for each field so that fluorescence transients could be clearly resolved without significant photobleaching. Each field was also imaged briefly with 1040nm excitation light for visualizing td-Tomato expression in D1 expressing neurons. Fields were imaged within a ~1.5mm region around the center of the cannula (across the ‘dorsal central-medial’ striatum) in each session.

Head fixed behavior apparatus and virtual track task

Head-fixed behavior apparatus.

Mice were head-fixed with their limbs resting on a hollow 8-inch diameter styrofoam ball (Smoothfoam) mounted on a metal rod axle (McMaster-Carr, #1263K46). The axle had ball bearings (McMaster-Carr,7804K129) attached to each end, which were mounted into a 3D printed cradle, permitting the mouse to locomote forward and backward but restricting angular movement. Ball rotation was measured using an optical mouse sensor (Logitech G203, shells removed, 400 dpi sensitivity, polling rate 1kHz) positioned parallel to the axle. Output from the sensor was relayed to a Raspberry Pi (3B+) and converted to an analog voltage through a digital-to-analog converter (DAC, MCP4725) then sampled at 2kHz by an acquisition board (NIDAQ, PCle 6343)43. Water rewards were delivered through a water spout connected to a 60ml syringe gated by a digitally controlled solenoid valve (Neptune Research, #161T012). Spout licking was monitored through a custom capacitive touch circuit connected to the water spout. Solenoid valve control and lick data acquisition was carried out through the NIDAQ board. Custom MATLAB software was used to trigger rewards and visualize and acquire behavioral data.

Virtual linear track task.

The virtual environment was designed using the Virtual Reality MATLAB Engine (ViRMEn34) and displayed across 5 computer monitors vertically arranged in a semi-circle at a distance of ~35cm (side) to ~40cm(front) from the mouse. The linear tracks were distinct 3D visual scenes with different distal and proximal landmarks and walls with unique colors and geometric patterns (Figs. 1c and 3a). Tracks were 160 virtual units long, and output from the optical treadmill sensor was used to update the track display (virtual track position) according to the mouse locomotor velocity. The conversion was scaled so that tracks had a fixed length for each mouse ranging from 1.25–2.25m. Custom MATLAB functions were used to update the mouse track position and control the task contingency and trial structures. All mice were initially trained on a track length of 1m then the track length was gradually increased. Each trial began with the mouse positioned in a ‘start zone’ with a virtual gate blocking the main track. The gate opened when the mouse satisfied a stillness criterion by maintaining its velocity below 8–10 cm/s for 1.5s. The mouse was then free to run down the central arm of the track to reach the reward location at the end, where it received a 7 μL water reward with a 90% probability. After reward delivery, there was a 5s consumption period where the screen froze and the mouse movement did not affect its track position. Mice were then teleported back to the start zone, where the clocks for a 2–6 second inter trial interval and the 1.5 seconds stillness criteria started. Imaging began after mice ran at >1 trial/min, with clear signs of deceleration before reward (visual inspection) for at least 3 days. Five mice were trained initially on one track and four of these were then trained on a second world with the same length but distinct visual features after 5 days (Fig. 3). In 2 world scenarios, two uniquely designed virtual tracks alternated from trial to trial at 50% probability. The reward probability was the same (90%) in the two worlds. Only sessions after 2 days of experience with the 2nd track were included in analysis to avoid novelty effects. Two of the mice trained in VR and one additional mouse were imaged in darkness with the visual display off (Figs. 1h–k and Extended Data Fig. 1f,g). In VR off sessions, mice were delivered unpredicted water rewards at 5–50s intervals drawn from a uniform distribution.

Data pre-processing and analysis

Imaging data pre-processing.

Videos were motion-corrected using a whole-frame cross-correlation algorithm algorithm33,43. Source extraction was done using the CaImAn package, which employs a constrained non-negative matrix factorization (CNMF) algorithm to identify putative neurons (ROIs)44. Selection of qualified ROIs and classification of SPN cell type were performed by manual inspection. Cholinergic and GABAergic interneurons comprise only a small population of striatal neurons (~5% in the rodent) and are characterized by distinct morphology and higher firing rates relative to SPNs. To minimize contamination from this small population, ROIs with large, irregularly shaped soma or with low amplitude continuous fluctuations in Ca2+ fluorescence, common to striatal interneurons, were excluded from analysis. Identification of D1-positive neurons was performed by manually inspecting the alignment of the red, td-Tomato channel with the ROI masks from the green GCaMP7f channel. Green ROI masks that clearly overlapped with a td-Tomato positive soma were classified as dSPNs, while ROIs that unambiguously did not overlap with a td-Tomato positive soma were classified as putative iSPNs. To minimize false positives, ROIs with partial or ambiguous td-Tomato overlap were omitted from analysis, however, our labeling method and cell-identification approach likely yielded more false negatives than false positives, resulting in an apparently larger population of putative iSPNs. Conversion to ΔF/F was done through the method provided by CaImAn, where the baseline fluorescence (F) was determined as the 8th quantile over a 500 frame moving window. ΔF/F was then thresholded to isolate significant positively going Ca2+ transients, defined as events exceeding 2 standard deviations above the median of a null distribution. The null distribution was made by truncating the session ΔF/F with normal distribution parameters in an exponentially modified Gaussian distribution, with parameters estimated using a maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) approach. Coregistration of ROIs across recording movies in and out of VR on the same day (Extended Data Fig. 1d–g) was performed using a multi-session registration algorithm from the CaImAn package. For a pair of track and spontaneous running sessions, each ROI was identified as coregistered if they satisfied three conditions: 1) the ROI was identified across sessions by CaImAn; 2) the ROI passed manual inspection in both sessions; 3) the ROI’s cell type classification was identical in both sessions.

Behavioral variables and binning.

The voltage output from the optical sensor was converted to linear velocity in m/s. Velocity traces were smoothed twice consecutively using the MATLAB ‘smooth’ function with window sizes of 1s and 0.5s. Acceleration was the derivative of the smoothed velocity, smoothed again using moving average with a 0.1 second window. Locomotion bouts in and out of VR were defined as periods where the velocity was maintained above a 3 cm/s threshold for more than 3 seconds. For each bout, the first time point above the velocity threshold was labeled a movement onset, and the last time point above velocity threshold was labeled a movement offset. Bouts with a peak velocity below 10 cm/s in VR or 15 cm/s out of VR (to obtain comparable velocities in and out of VR) and those that had velocity drops below 5 cm/s were excluded from analysis. Bout onsets and offsets occurring during reward delivery periods (out of VR) or during ITI periods (in VR) were excluded from all analysis. Position binning on the track was performed by equally dividing the main track (from end of start zone to reward location) into 100 position bins. For spontaneous running, binning was calculated as a percentage of the total distance traveled in each bout. The total distance traveled in a bout was defined as the distance traveled from 1s before movement onset to 1s after movement offset. To account for variability between mice and session and repeated measures, we fit the position binned or triggered average velocity or acceleration to a Linear Mixed Effect model (see below) using the MATLAB function ‘fitlme’. The model considers mice and sessions as random effects, with sessions nested within mice. The estimated population mean and the confidence interval were then used to plot the center line and shaded regions of the line plots.

Quantification of mean population activity and dSPN/iSPN differences.

For plots showing mean ΔF/F or differences between dSPN/iSPN ΔF/F means, we first calculated the means for each trial (binned by position or triggered on events as indicated in each figure) and across each subpopulation (as indicated in each figure, dSPNs/iSPNs, tuned/untuned, etc.) for each imaging field. To calculate the mean activity of dSPNs and iSPNs or their difference, accounting for variability across trials, sessions, and mice, we used a Linear Mixed Effect model (MATLAB function ‘fitlme’) for each bin or timepoint with the following equation:

For a given binary condition variable , is the estimated mean given , and is the estimated difference between the two level of (dSPN and iSPN). Unless otherwise specified, the mixed effect model considers mice and sessions as random effects, with sessions nested within mice. The 95% confidence intervals of the mean or difference terms were displayed as shaded regions in all plots.

Position tuning and track sensitivity.

To determine whether each neuron was stably tuned to a track position over trials, we correlated mean position-binned ΔF/F computed from odd and even trials within a session (rate map). The true correlation coefficient was compared to a distribution of correlation values calculated after shifting the ΔF/F trace of each neuron randomly (> 33ms, 500 iterations) relative to trial epochs and rebinning ΔF/F by odd and even trials and position. If the true within track correlation value exceeded the 95th percentile of the randomized distribution and the neuron had significant ΔF/F transients on at least 40% of trials it was determined to have stable position tuning. Position fields of tuned neurons were calculated by finding the position bin with maximum ΔF/F and finding the positions before and after where the ΔF/F dropped below 20% of the difference between the maximum and minimum ΔF/F values. For population analysis comparing tuned and untuned ΔF/F (Fig. 2e–h), only untuned neurons with a ΔF/F exceeding 0.5 on at least 40% of trials were included to account for overall ΔF/F differences between tuned and untuned populations introduced by our criteria.

Track sensitivity was determined using a similar process on sessions with two tracks. Correlations were computed between mean positional ΔF/F rate maps from track 1 and track 2 and compared to a bootstrap distribution in which two mean positional ΔF/F rate maps were computed using trials that were randomly swapped across the two tracks (500 iterations). If the true cross-track correlation was lower than the 1st percentile of the randomized distribution the neuron was classified as track sensitive. For population analyses comparing track sensitive and insensitive populations (Fig. 3f–i), only neurons with significant position tuning and track sensitivity for the most familiar track (i.e. the one prior to the introduction of the 2nd track sessions) were included. Only trials in the most familiar track (where neurons were significantly tuned) were plotted to avoid confounds with learning or novelty dependent effects in the less familiar track on the dSPN/iSPN balance. One mouse was excluded from the population analysis because it ran in a significantly shorter track than the others.

Notes on statistical tests and sample sizes.

Non-parametric tests for significance were used for all analyses unless otherwise noted. Specific tests and sample sizes are indicated within figure legends or in the main text. Multiple comparisons were corrected using the Bonferroni-Holm’s correction.(Bonferroni-Holm Correction for Multiple Comparisons - File Exchange - MATLAB Central (mathworks.com))

Extended Data

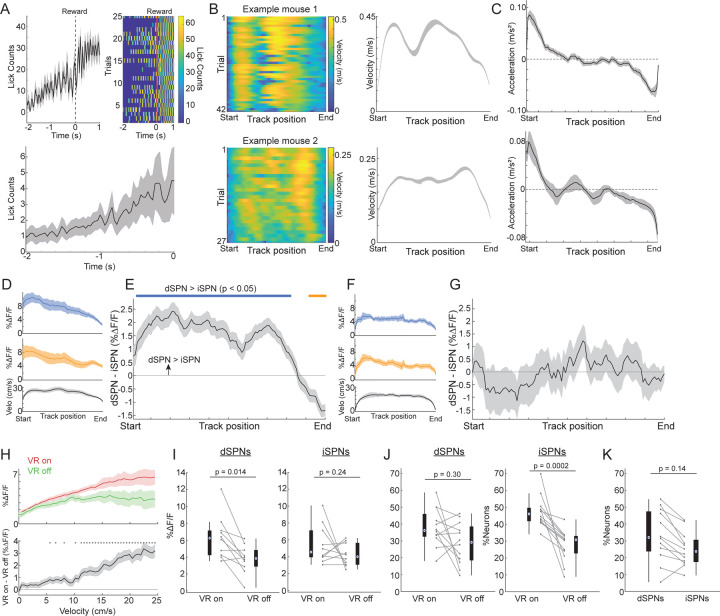

Extended Data Figure 1: Additional behavioral measures and activity comparisons in and out of VR.

A.) Mean spout licking triggered on reward deliveries at the end of the linear track from one representative session (top left) and across mice (n = 5) and sessions (n = 36) (bottom). Top right is a raster of lick counts on all individual trials for the session at top left. B.) Left: Velocity binned by track position across all trials in two example sessions in two different mice with distinct velocity profiles. Right: Mean velocity binned by track position for the two sessions shown at left. C.) Mean treadmill acceleration binned by track position (top) and locomotion bout progress (bottom) across all sessions in (top, n = 36 sessions) and out (bottom, n = 35 sessions) of VR. D.) Mean ΔF/F of dSPNs (blue, n = 271), iSPNs (orange, n = 358), and treadmill velocity (black) binned by position along the linear track from the 2 mice and 12 sessions with corresponding imaging of the same fields outside VR. E.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F between dSPNs and iSPNs binned by track position for the sessions in D. F.) Mean ΔF/F of dSPNs (blue, n = 218), iSPNs (orange, n = 293), and treadmill velocity (black) for spontaneous locomotion bouts occurring outside of VR binned by relative bout progress normalized to the distance of each bout from the 2 mice in D (10 sessions) D. G.) Mean difference in population ΔF/F between dSPNs and iSPNs binned by bout progress for the sessions in F. H.) Top: Mean ΔF/F binned by velocity for all SPNs imaged in the same sessions in and out of VR. Bottom: Difference in mean ΔF/F between inside and outside VR for the cells and sessions at top. Asterisks, p < 0.05. I.) Boxplot of the mean ΔF/F per second during locomotion bouts (see Methods) in VR-on and VR-off sessions for dSPNs (left) and iSPNs (right). Each point is the mean across all neurons in a session, lines connect corresponding sessions with the same imaging field. J.) Boxplot of the percentage of the total dSPNs (left) and iSPNs (right) active only in VR-on or VR-off periods for sessions with the same imaging fields in both as in I. K.) Boxplot of the percentage of the total dSPNs and iSPNs active in both VR-on and VR-off periods as in J. P-values, Wilcoxon rank sum test. Shaded regions, 95% confidence intervals of the model coefficients from the linear mixed effect model (see Methods).

Extended Data Figure 2: Additional comparisons of track sensitive and insensitive neurons.

A.) Pairwise correlations (Spearman’s rho) between the mean ΔF/F at a given track position across all track sensitive (top) and insensitive (bottom) neurons in track 1 and the mean ΔF/F across the same neurons in track 2. Matrices show correlations between the mean ΔF/F population vectors for all combinations of track positions. Values along the diagonal (dashed line) are correlations for the same relative positions in tracks 1 and 2, so high correlations indicate similar mean population activity in the two tracks at that position. Red lines indicate the combination of track 1 and 2 positions with the highest correlation. B.) Mean correlations for track sensitive (top) and insensitive (bottom) dSPN (blue) and iSPN (orange) mean ΔF/F population vectors between the same relative positions in tracks 1 and 2 (the diagonal in A). Correlations were computed for each session at each position then averaged across sessions. C.) Boxplots of the correlations (Spearman’s rho) of position-binned mean ΔF/F for each neuron (dot) between track 1 and track 2 for all dSPNs (top) and iSPNs (bottom) classified as track sensitive and insensitive. D.) Boxplots of the absolute deviation (error, in cm; red line in A) between the empirical peak correlation position and the expected peak correlation if the activity pattern relative to position was identical in track 1 and track 2 for track sensitive and insensitive dSPNs (top) and iSPNs (bottom). Pairs of connected dots are comparisons of SPNs in the same session. E.) Boxplot of the percent track sensitive dSPNs and iSPNs of the total stable position tuned population for each session. Dots and lines indicate percentages for each session. P-values, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test.

Extended Data Figure 3: Model for the generation of dSPN/iSPN activity imbalances.

During stereotyped locomotion through a familiar environment (e.g. the VR track), individual dSPNs and iSPNs (blue and orange dots, respectively) receive excitatory, glutamatergic inputs encoding distinct visual features of the environment at each position, giving rise to the position tuning within specific environments we observed (Figs. 2 and 3 and Extended Data Fig. 2). In addition, position tuned SPNs receive glutamatergic and dopaminergic inputs which signal locomotor kinematics at all positions in the environment. Note that each SPN likely receives different relative levels of position and locomotor input, giving rise to diverse tuning across the population (e.g. some neurons will not be sensitive to visual input, Fig. 3). The visual input at each position onto dSPNs and iSPNs is equivalent, but the synaptic weights (W) of the position inputs onto each SPN differ depending on the locomotion kinematics at each position: dSPN weights > iSPN at positions where animals accelerate or sustain high velocity and iSPN weights < dSPN at positions where animals decelerate. Thus, the relative dSPN/iSPN balance at each position reflects an association of context specific visual input and locomotion kinematics. The asymmetric weights onto dSPNs and iSPNs are produced by the kinematic signal transmitted by the dopaminergic (perhaps in conjunction with the glutamatergic) inputs. Dopamine release bi-directionally modulates synaptic plasticity in SPNs, promoting long term potentiation and depression of dSPN and iSPN synapses respectively39,40. Thus, dopamine fluctuations related to ongoing locomotion kinematics will selectively strengthen or weaken the sensory inputs at each position with repeated stereotyped experience (e.g. animals always slow down at the same track position). When visual inputs are not associated with consistent locomotor kinematics (such as during spontaneous running with VR off, Fig. 1h–i and Extended Data Fig. 1d–g) or if neurons receive only continuous locomotor input, the dSPN/iSPN output is balanced (right panels).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Klingenstein-Simons’s Foundation fellowship, Whitehall Foundation Fellowship, National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH125835) to M.W.H and a Postdoctoral Training Fellowship to B.F. through the Boston University Center for Systems Neuroscience. We thank the Boston University Centers for Neurophotonics and Systems Neuroscience for financial and technical support and Boston University Animal Science Center for providing central laboratory and animal care and support resources. We thank Dr. Mai-Anh Vu, Ryan Senne and Kylie Feliciano for their technical help with analysis pipelines, task design, and equipment setup. We thank Dr. Milan Valyear and Eleanor Brown for their comments on a draft of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mink J. W. THE BASAL GANGLIA: FOCUSED SELECTION AND INHIBITION OF COMPETING MOTOR PROGRAMS. Prog. Neurobiol. 50, 381–425 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graybiel A. M., Aosaki T., Flaherty A. W. & Kimura M. The basal ganglia and adaptive motor control. Science 265, 1826–1831 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robbe D. To move or to sense? Incorporating somatosensory representation into striatal functions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 52, 123–130 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong Q., Znamenskiy P. & Zador A. M. Selective corticostriatal plasticity during acquisition of an auditory discrimination task. Nature 521, 348–351 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sippy T., Lapray D., Crochet S. & Petersen C. C. H. Cell-Type-Specific Sensorimotor Processing in Striatal Projection Neurons during Goal-Directed Behavior. Neuron 88, 298–305 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerfen C. R. et al. D 1 and D 2 Dopamine Receptor-regulated Gene Expression of Striatonigral and Striatopallidal Neurons. Science 250, 1429–1432 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parent A., Bouchard C. & Smith Y. The striatopallidal and striatonigral projections: two distinct fiber systems in primate. Brain Res. 303, 385–390 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckstead R. M. & Cruz C. J. Striatal axons to the globus pallidus, entopeduncular nucleus and substantia nigra come mainly from separate cell populations in cat. Neuroscience 19, 147–158 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander G. E. & Crutcher M. D. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 13, 266–271 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLong M. R. Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci. 13, 281–285 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albin R. L., Young A. B. & Penney J. B. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 12, 366–375 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz A. V. et al. Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature 466, 622–626 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bateup H. S. et al. Distinct subclasses of medium spiny neurons differentially regulate striatal motor behaviors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 14845–14850 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durieux P. F., Schiffmann S. N. & De Kerchove d’Exaerde A. Differential regulation of motor control and response to dopaminergic drugs by D1R and D2R neurons in distinct dorsal striatum subregions: Dorsal striatum D1R- and D2R-neuron motor functions. EMBO J. 31, 640–653 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panigrahi B. et al. Dopamine Is Required for the Neural Representation and Control of Movement Vigor. Cell 162, 1418–1430 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yttri E. A. & Dudman J. T. Opponent and bidirectional control of movement velocity in the basal ganglia. Nature 533, 402–406 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tecuapetla F., Jin X., Lima S. Q. & Costa R. M. Complementary Contributions of Striatal Projection Pathways to Action Initiation and Execution. Cell 166, 703–715 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H. & Jin X. Multiple dynamic interactions from basal ganglia direct and indirect pathways mediate action selection. eLife 12, RP87644 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maltese M., March J. R., Bashaw A. G. & Tritsch N. X. Dopamine differentially modulates the size of projection neuron ensembles in the intact and dopamine-depleted striatum. eLife 10, e68041 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui G. et al. Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation. Nature 494, 238–242 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker J. G. et al. Diametric neural ensemble dynamics in parkinsonian and dyskinetic states. Nature 557, 177–182 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbera G. et al. Spatially Compact Neural Clusters in the Dorsal Striatum Encode Locomotion Relevant Information. Neuron 92, 202–213 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin X., Tecuapetla F. & Costa R. M. Basal ganglia subcircuits distinctively encode the parsing and concatenation of action sequences. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 423–430 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weglage M. et al. Complete representation of action space and value in all dorsal striatal pathways. Cell Rep. 36, 109437 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klaus A. et al. The Spatiotemporal Organization of the Striatum Encodes Action Space. Neuron 95, 1171–1180.e7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nonomura S. et al. Monitoring and Updating of Action Selection for Goal-Directed Behavior through the Striatal Direct and Indirect Pathways. Neuron 99, 1302–1314.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varin C., Cornil A., Houtteman D., Bonnavion P. & De Kerchove d’Exaerde A. The respective activation and silencing of striatal direct and indirect pathway neurons support behavior encoding. Nat. Commun. 14, 4982 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bariselli S., Fobbs W. C., Creed M. C. & Kravitz A. V. A competitive model for striatal action selection. Brain Res. 1713, 70–79 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng C. et al. Spectrally Resolved Fiber Photometry for Multi-component Analysis of Brain Circuits. Neuron 98, 707–717.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markowitz J. E. et al. The Striatum Organizes 3D Behavior via Moment-to-Moment Action Selection. Cell 174, 44–58.e17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ade K. K., Wan Y., Chen M., Gloss B. & Calakos N. An Improved BAC Transgenic Fluorescent Reporter Line for Sensitive and Specific Identification of Striatonigral Medium Spiny Neurons. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5, 32 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dana H. et al. High-performance calcium sensors for imaging activity in neuronal populations and microcompartments. Nat. Methods 16, 649–657 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howe M. W. & Dombeck D. A. Rapid signalling in distinct dopaminergic axons during locomotion and reward. Nature 535, 505–510 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aronov D. & Tank D. W. Engagement of Neural Circuits Underlying 2D Spatial Navigation in a Rodent Virtual Reality System. Neuron 84, 442–456 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitzer-Torbert N. C. & Redish A. D. Task-dependent encoding of space and events by striatal neurons is dependent on neural subtype. Neuroscience 153, 349–360 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berke J. D., Breck J. T. & Eichenbaum H. Striatal Versus Hippocampal Representations During Win-Stay Maze Performance. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 1575–1587 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin D. Z., Fujii N. & Graybiel A. M. Neural representation of time in cortico-basal ganglia circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 19156–19161 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizumori S. J. Y., Ragozzino K. E. & Cooper B. G. Location and head direction representation in the dorsal striatum of rats. Psychobiology 28, 441–462 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calabresi P., Picconi B., Tozzi A. & Di Filippo M. Dopamine-mediated regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 30, 211–219 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerfen C. R. & Surmeier D. J. Modulation of Striatal Projection Systems by Dopamine. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34, 441–466 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patriarchi T. et al. Ultrafast neuronal imaging of dopamine dynamics with designed genetically encoded sensors. Science 360, eaat4422 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azcorra M. et al. Unique functional responses differentially map onto genetic subtypes of dopamine neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 1762–1774 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vu M.-A. T. et al. Targeted micro-fiber arrays for measuring and manipulating localized multi-scale neural dynamics over large, deep brain volumes during behavior. Neuron 112, 909–923.e9 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giovannucci A. et al. CaImAn an open source tool for scalable calcium imaging data analysis. eLife 8, e38173 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]