Abstract

Background.

In the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) 2010/VESTED study, pregnant women were randomized to initiate dolutegravir (DTG) + emtricitabine (FTC)/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), DTG + FTC/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), or efavirenz (EFV)/FTC/TDF.

Methods.

We assessed red blood cell (RBC) folate concentrations at maternal study entry and delivery, and infant birth. RBC folate outcomes were (1) maternal change entry to delivery (trajectory), (2) infant, and (3) ratio of infant-to-maternal delivery. Generalized estimating equation models for each log(folate) outcome were fit to estimate adjusted geometric mean ratio (Adj-GMR)/GMR trajectories (Adj-GMRTs) of each arm comparison in 340 mothers and 310 infants.

Results.

Overall, 90% of mothers received folic acid supplements and 78% lived in Africa. At entry, median maternal age was 25 years, gestational age was 22 weeks, CD4 count was 482 cells/μL, and log10 HIV RNA was 3 copies/mL. Entry RBC folate was similar across arms. Adj-GMRT of maternal folate was 3% higher in the DTG + FTC/TAF versus EFV/FTC/TDF arm (1.03 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.00–1.06]). The DTG + FTC/TAF arm had an 8% lower infant-maternal folate ratio (0.92 [95% CI, .78–1.09]) versus EFV/FTC/TDF.

Conclusions.

Results are consistent, with no clinically meaningful differences between arms for all RBC folate outcomes, and they suggest that cellular uptake of folate and folate transport to the infant do not differ in pregnant women starting DTG- versus EFV-based antiretroviral therapy.

Keywords: dolutegravir, efavirenz, pregnancy, infant, red blood cell folate concentrations

Use of antiretroviral treatment (ART) during pregnancy is essential to maintain maternal health and prevent vertical human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission. Botswana was among the first countries to roll out dolutegravir (DTG)–based ART in first-line HIV treatment, in 2016. An initial report in 2018 from the Botswana Tsepamo pregnancy surveillance study showed an early association between DTG use at conception and neural tube defects (NTDs) (prevalence of 4/426 [0.94%] compared to non-DTG regimens (14/11 300 [0.12%]) and HIV-negative women (61/66 057 [0.09%]) [1]. In a subsequent analysis that expanded the surveillance population, the signal suggesting an increased NTD risk was no longer statistically significant [2, 3], although the initial association remains unexplained [3].

The initial signal from the Tsepamo Botswana study in 2018 [1] prompted investigation of possible effects of DTG on folate metabolism and cellular uptake. Risk of an NTD-affected pregnancy increases about 10-fold as red blood cell (RBC) folate concentrations decrease [4], and a number of medications are known to reduce folate concentrations and increase NTD risks [5–7]. Low folate status is also associated with adverse outcomes across the lifespan depending on the timing of exposure. These include other birth defects such as congenital heart defects, developmental delays such as autism, mental health outcomes, and cancers [8]. The wide-ranging impacts of low folate are due to the fundamental role of folate as a source of 1-carbons for DNA and RNA synthesis as well as cellular regulation and detoxification [9]. Two studies concluded that DTG affects folate metabolism [10, 11]. One study in zebrafish suggested that DTG is a partial antagonist of the folate receptor, FOLR1, and that exposure to DTG in the embryonic period can lead to developmental toxicity, which may be mitigated by folic acid supplementation [10]. In the ADVANCE trial of ART-naive nonpregnant adults with HIV randomized to start tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)/emtricitabine (FTC) + DTG, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)/FTC + DTG, or TDF/FTC/efavirenz (EFV), serum folate concentrations were on average lower in women in the TDF/FTC/EFV arm compared to the 2 DTG arms [11]. The authors hypothesized that DTG may block uptake of folate at the cellular level. In contrast, mice randomized to receive a therapeutic DTG dose or water starting at conception had similar total fetal folate levels in the 2 groups, suggesting to the authors that DTG is unlikely to inhibit cellular uptake of folate [12]. However, mice in the DTG group had a greater risk of fetal anomalies compared to controls, with all NTDs occurring in the DTG group [12]. An in vitro study found no evidence of a clinically meaningful inhibition of folate transport by DTG [13]. Children and adolescents randomized to DTG had higher RBC folate concentrations than standard of care [14].

To test the hypothesis that DTG might block cellular uptake and/or transplacental transfer of folate, we measured RBC folate in a subset of pregnant women and newborns who took part in a randomized trial (International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials [IMPAACT] 2010/Virologic Efficacy and Safety of ART Combinations with TAF/TDF, EFV, and DTG [VESTED]) that compared the safety and efficacy of 3 different ART regimens started in pregnancy: DTG + FTC/TAF, DTG + FTC/TDF, and EFV/FTC/TDF) [15]. This trial enrolled women in 9 countries, which also allowed us to explore RBC folate levels and deficiency in pregnant women from a number of regions.

METHODS

Study Design

IMPAACT 2010/VESTED was a multicenter, open-label phase 3 clinical trial that randomized pregnant women living with HIV between 14 and 28 weeks’ gestation to initiate ART in 1 of 3 arms: DTG + FTC/TAF, DTG + FTC/TDF, or EFV/FTC/TDF [15]. Participants were enrolled in 9 countries in Africa, South and North America, and Asia and were ART-naive (up to 14 days’ nonstudy ART during current pregnancy permitted); exclusion criteria included pregnancy with a fetus that had a known anomaly or multiple fetuses, or clinically significant acute medical illness or psychiatric condition, among others [15]. Following randomization, antepartum study visits occurred every 4 weeks and at delivery/birth. The primary pregnancy outcomes, viral suppression at delivery, and other key results were published previously [15].

IMPAACT 2010/VESTED started enrolling in January 2018. Following the initial Tsepamo study report in May 2018 of a possible NTD association with DTG at conception [1, 2], the IMPAACT 2010/VESTED protocol was amended to include evaluation of possible mechanisms that might explain this association, including collection of blood samples from women at entry and delivery and from infants at birth for measurement of whole blood folate and hematocrit to allow the calculation of RBC folate. This study was approved by institutional review boards at each site. All participants provided written informed consent.

Assessment of RBC Folate

Folate (vitamin B9) encompasses both naturally occurring folates obtained from food and folic acid, a form used in dietary supplements and fortified foods. RBC folate concentrations represent long-term folate stores (over the last 120 days) [16]. Whole blood folate was measured at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention by use of a microbiologic assay calibrated with 5-methyltetrahydrofolate to match the response of endogenous folate (see laboratory 1 in report by Pfeiffer et al.) [17–19]. Whole blood hemolysates were prepared by diluting freshly collected whole blood 1:11 with 1% ascorbic acid solution and stored frozen at −70°C until analysis. The samples of each treatment group were carefully balanced in measurement for minimizing potential bias. The formula for calculating RBC folate concentration in nmol/L is as follows: .

If current hematocrit was unavailable, we used single imputation taking the median baseline value from all women or from all infants. We categorized RBC folate as deficient (at risk of anemia and high risk of an NTD-affected pregnancy, <305 nmol/L), insufficient (increased risk of NTDs, 305–748 nmol/L), or optimal (>748 nmol/L) [20].

Factors That Impact RBC Folate Concentrations

Maternal folate concentrations can be impacted by many factors including dietary intake of foods with naturally occurring folate or fortified with folic acid, folic acid supplements, and folate antagonists. Dietary intake was not collected. Season may reflect availability of relevant foods. Start and stop dates of folic acid and other vitamin/micronutrient supplementation and receipt of folate antagonists at entry and throughout the study were collected. We used the Global Fortification Data Exchange website to obtain the 2019 country level folic acid fortification data (yes/no) for wheat alone or in combination with maize, and the targeted level of folic acid fortification per country (micrograms/day) [21].

Statistical Analysis

The following study outcomes were selected to determine if there is a differential effect of starting DTG- versus EFV-based ART (or TAF vs TDF) on (1) RBC concentration of folate in pregnant women from entry to delivery, and placental transport of folate to the fetus, by evaluating (2) infant RBC folate at birth and (3) the relative amount of folate transferred to the fetus from the mother (infant-to-maternal RBC folate ratio at delivery/birth).

Maternal Characteristics and RBC Folate Concentrations by Treatment Arm

Entry maternal characteristics by treatment arm were described using median (Q1, Q3) for continuous variables and frequency (%) for categorical variables. RBC folate was loge transformed and back transformed to estimate the by arm geometric mean and geometric mean standard deviation for maternal concentrations at study entry and delivery, infant folate at the birth visit, and infant-to-maternal delivery ratio at birth.

Precision Variables

Precision variables were included to potentially increase the precision of the estimated treatment effects: country, time from study entry to delivery (weeks), timing of folic acid supplementation and folate antagonists from entry to delivery, mandatory folic acid fortification in country (yes/no), targeted level of folic acid fortification per country (micrograms/day), and season [19].

Comparison of RBC Folate Concentrations From Entry to Delivery Between Treatment Arms

Longitudinal generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were fit with loge of RBC folate as the outcome measure to compare the 4-week geometric mean ratio trajectory (GMRT) of maternal folate from start of treatment to delivery between study arms. To compare groups, models included a continuous linear time and treatment arm main effects plus a term for time by arm. Model coefficients were exponentiated to estimate the GMRT of 1 arm divided by another with corresponding 95% Wald confidence intervals (CIs). The GEE model was specified using the identity link, an independence working correlation matrix, and the robust variance estimator. Models were summarized both unadjusted and adjusted for precision variables. Targeted level of folic acid fortification per country was not included in the models due to overlap with other variables. The adjusted comparison of GMRT between treatment groups is hereafter referred to as aGMRT/C. All 3 pairwise comparisons between arms were computed, as were comparisons of the combined DTG-containing arms versus the EFV-containing arm.

Comparison Between Arms of Infant Birth Folate and Infant-to-Maternal Delivery Folate

For infant folate concentration and infant-to-maternal delivery ratio outcomes, analyses were conducted with similar approaches to those described above except there was only 1 measurement per person so comparisons are based on geometric mean ratios (GMRs). We fit unadjusted and adjusted linear regression models with the robust variance, with estimates expressed as the geometric mean ratio (adjusted [aGMR]). In a sensitivity analysis for the outcome infant-to-maternal ratio, the model was also adjusted for maternal delivery folate.

All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 software. Our focus was on clinical significance and the point estimate (95% CI). P values are provided, without a cutoff level for statistical significance, to show evidence against the null hypothesis.

RESULTS

Entry Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Overall, 643 women enrolled in IMPAACT 2010/VESTED, of whom 415 entered and 435 delivered (some already on study) after the site implementation date of the amendment and between June 2018 and August 2019 when sample collection for RBC folate measurement occurred. Of these, 340 women and 310 infants had ≥1 RBC folate measurement. Overall, 90% of mothers received folic acid supplements and 90% lived in countries with folic acid fortification of food program. A folate result was obtained at entry on 319 of 415 (77%) women, at delivery on 323 of 435 (74%) women, and in 310 of 420 liveborn infants (74%).

Among the 340 pregnant women included, median entry age was 25 years, median gestational age was 22 weeks, and most (78%) women enrolled in Africa (Table 1). Maternal entry characteristics were similar across study arms except for gestational age. The median number of weeks between entry and delivery was 1 week shorter in the EFV/FTC/TDF arm (18 weeks) compared to the DTG arms (19 weeks), partly due to the EFV/FTC/TDF arm having more infants born preterm.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Pregnant Women With Human Immunodeficiency Virus by Treatment Arm at Study Entry and at Delivery

| Characteristic | DTG + FTC/TAF (n = 114) | DTG + FTC/TDF (n = 114) | EFV/FTC/TDF (n = 112) | Total (n = 340) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristics at study entry | ||||

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | 6 (5) | 17 (5) |

| Black or African American | 93 (82) | 96 (84) | 95 (85) | 284 (84) |

| White | 5 (4) | 6 (5) | 7 (6) | 18 (5) |

| Other | 10 (9) | 6 (5) | 4 (4) | 20 (6) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 21 (18) | 19 (17) | 17 (15) | 57 (17) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 91 (80) | 94 (82) | 95 (85) | 280 (82) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Country | ||||

| Brazil | 21 (18) | 19 (17) | 17 (15) | 57 (17) |

| Botswana | 4 (4) | 6 (5) | 7 (6) | 17 (5) |

| India | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Thailand | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 6 (5) | 14 (4) |

| Tanzania | 7 (6) | 5 (4) | 8 (7) | 20 (6) |

| Uganda | 34 (30) | 32 (28) | 32 (29) | 98 (29) |

| United States | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| South Africa | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Zimbabwe | 41 (36) | 43 (38) | 42 (38) | 126 (37) |

| Age, y, median (Q1, Q3) | 26 (22, 30) | 25 (21, 29) | 25 (22, 30) | 25 (22, 30) |

| Age categories, y | ||||

| 18–22 | 40 (35) | 38 (33) | 32 (29) | 110 (32) |

| 23–26 | 23 (20) | 28 (25) | 32 (29) | 83 (24) |

| 27–31 | 31 (27) | 24 (21) | 28 (25) | 83 (24) |

| ≥32 | 20 (18) | 24 (21) | 20 (18) | 64 (19) |

| Weight, kg, median (Q1, Q3) | 63 (55, 71) | 61 (55, 70) | 59 (55, 67) | 61 (55, 69) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (Q1, Q3) | 24 (22, 27) | 24 (22, 27) | 23 (21, 26) | 24 (22, 27) |

| Gestational age, wk, median (Q1, Q3) | 22 (17, 25) | 21 (18, 25) | 22 (18, 26) | 22 (17, 25) |

| Gestational age categories, wk | ||||

| 14–18 | 38 (33) | 35 (31) | 37 (33) | 110 (32) |

| 19–23 | 45 (39) | 47 (41) | 34 (30) | 126 (37) |

| 24–28 | 31 (27) | 32 (28) | 41 (37) | 104 (31) |

| WHO stagea | ||||

| Stage 1 | 113 (99) | 113 (99) | 110 (98) | 336 (99) |

| Stage 2 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (1) |

| CD4 count, cells/μL, median (Q1, Q3) | 483 (334, 632) | 480 (349, 622) | 482 (306, 673) | 482 (326, 644) |

| CD4 count, cells/μL | ||||

| 50 to <350 | 33 (29) | 29 (25) | 35 (31) | 97 (29) |

| 350 to <500 | 29 (25) | 31 (27) | 23 (21) | 83 (24) |

| 500–750 | 40 (35) | 34 (30) | 36 (32) | 110 (32) |

| >750 | 12 (11) | 20 (18) | 18 (16) | 50 (15) |

| HIV RNA, log10 copies/mL, median (Q1, Q3) | 3.2 (2.3, 3.9) | 3.0 (2.1, 3.9) | 3.2 (2.4, 3.7) | 3.1 (2.3, 3.8) |

| HIV RNA categories, log10 copies/mL | ||||

| <50 | 14 (12) | 19 (17) | 12 (11) | 45 (13) |

| 50 to <200 | 11 (10) | 15 (13) | 14 (13) | 40 (12) |

| 200 to <1000 | 27 (24) | 21 (18) | 23 (21) | 71 (21) |

| ≥1000 | 62 (54) | 59 (52) | 63 (56) | 184 (54) |

| Received ARVs during current pregnancy, prior to study entry (yes) | 82 (72) | 85 (75) | 83 (74) | 250 (74) |

| Type of ARVs received during current pregnancy prestudy | ||||

| No known history of ARV receipt | 32 (28) | 29 (25) | 29 (26) | 90 (26) |

| ATV/FTC/RTV/TDF | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| EFV/FTC/TDF | 3 (3) | 7 (6) | 4 (4) | 14 (4) |

| EFV/3TC/TDF | 77 (68) | 74 (65) | 76 (68) | 227 (67) |

| 3TC/RAL/TDF | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 6 (2) |

| TDF | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Category of maternal RBC folate concentration at entry (n = 319) | ||||

| Deficient (<305 nmol/L) | … | … | … | 20 (6) |

| Insufficient (305–748 nmol/L) | … | … | … | 138 (43) |

| Optimal (>748 nmol/L) | … | … | … | 161 (50) |

| Characteristics at delivery | ||||

| Category of maternal RBC folate concentration at delivery (n = 323) | ||||

| Deficient (<305 nmol/L) | … | … | … | 15 (5) |

| Insufficient (305–748 nmol/L) | … | … | … | 142 (44) |

| Optimal (>748 nmol/L) | … | … | … | 166 (51) |

| Preterm birthb | 2/101 (2) | 7/105 (7) | 9/104 (9) | 18/310 (6) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: 3TC, lamivudine; ARV, antiretroviral; ATV, atazanavir sulfate; BMI, body mass index; DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3; RAL, raltegravir; RBC, red blood cell; RTV, ritonavir; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; WHO, World Health Organization.

The denominators for the percentage with preterm birth are number of live births.

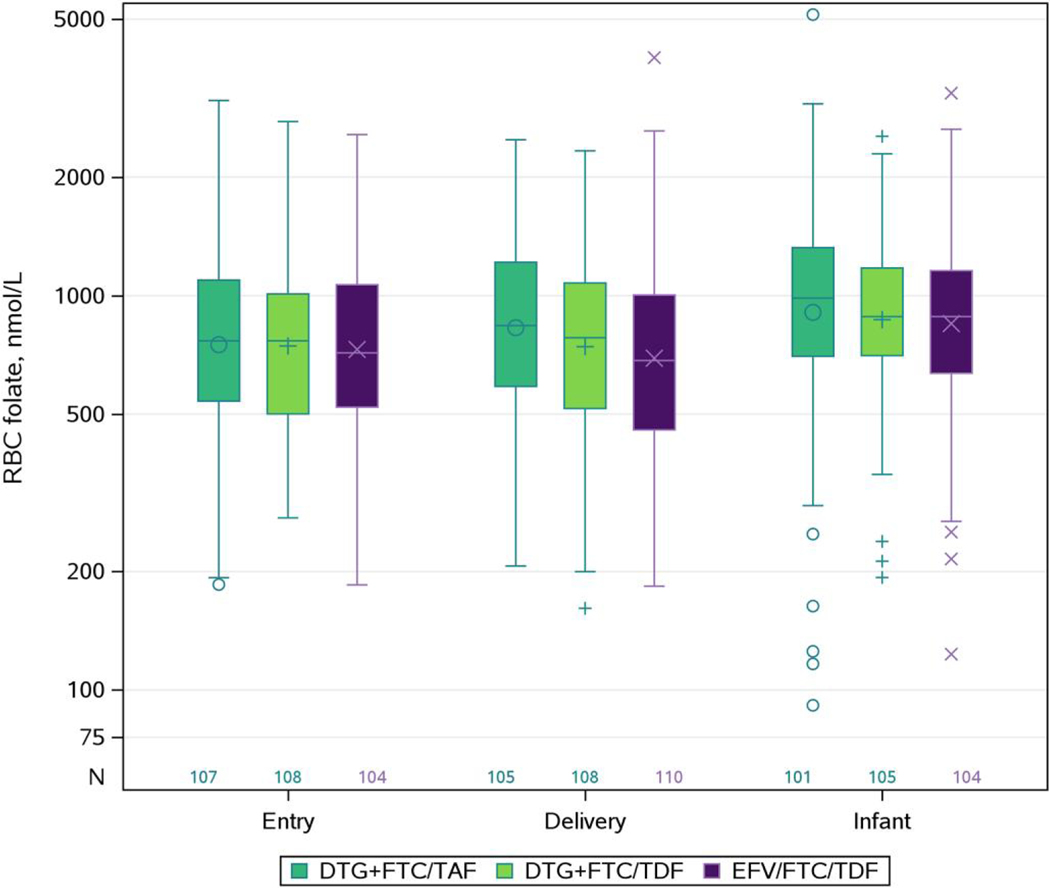

Percent of Pregnant Women Folate Deficient and Insufficient

At entry, the geometric mean for maternal RBC folate was 751 nmol/L, 746 nmol/L, and 731 nmol/L in the DTG + FTC/TAF, DTG + FTC/TDF, and EFV/FTC/TDF arms, respectively (Table 2). At entry and delivery, respectively, maternal RBC folate concentrations were deficient in 6% and 5%, insufficient in 43% and 44%, and optimal in 50% and 51% of pregnant women (Table 1). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of RBC folate for each measure.

Table 2.

Red Blood Cell Folate by Arm (and Differences Between Treatment Arms) in Pregnant Women With Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Their Infants in the IMPAACT 2010/VESTED Study in 9 Countries, June 2018–August 2019

| Group | Treatment Arm | RBC Folate, nmol/L, Geometric Mean (Geometric SD)a | Model Estimates of the GMR of Each Arm Comparison for Each RBC Folate Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Estimate (95% Cl)b,c,d | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Treatment Arm Comparison | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Pregnant women | DTG + FTC/TAF | Entry | 751 (1.76) | Pregnant women RBC folate trajectory | DTG + FTC/TAF vs DTG + FTC/TDF | 1.015 (.977–1.056) | 1.020 (.987–1.053) |

| Delivery | 830 (1.68) | P = .34 | P = .22 | ||||

| DTG + FTC/TDF | Entry | 746 (1.62) | DTG + FTC/TAF vs EFV/FTC/TDF | 1.022 (.983–1.063) | 1.028 (.995–1.062) | ||

| Delivery | 743 (1.67) | P = .22 | P = .094 | ||||

| EFV/FTC/TDF | Entry | 731 (1.67) | DTG + FTC/TDF vs EFV/FTC/TDF | 1.007 (.968–1.047) | 1.008 (.975–1.042) | ||

| Delivery | 694 (1.78) | P = .69 | P = .62 | ||||

| Infant at birth | DTG + FTC/TAF | 907 (1.96) | Infant RBC folate at birth (nmol/L) | DTG + FTC/TAF vs DTG + FTC/TDF | 1.044 (.897–1.215) | 1.019 (.884–1.174) | |

| P = .59 | P = .81 | ||||||

| DTG + FTC/TDF | 869 (1.57) | DTG + FTC/TAF vs EFV/FTC/TDF | 1.068 (.917–1.243) | 1.075 (.932–1.240) | |||

| P = .44 | P = .36 | ||||||

| EFV/FTC/TDF | 850 (1.70) | DTG + FTC/TDF vs EFV/FTC/TDF | 1.023 (.880–1.189) | 1.055 (.915–1.217) | |||

| P = .74 | P = .41 | ||||||

| Infant-to-maternal delivery ratio | DTG + FTC/TAF | 1.16 (2.15) | Infant-to-maternal delivery ratio | DTG + FTC/TAF vs DTG + FTC/TDF | 0.974 (.811–1.169) | 0.963 (.816–1.136) | |

| P = .79 | P = .69 | ||||||

| DTG + FTC/TDF | 1.19 (1.86) | DTG + FTC/TAF vs EFV/FTC/TDF | 0.954 (.794–1.144) | 0.923 (.781–1.089) | |||

| P = .62 | P = .36 | ||||||

| EFV/FTC/TDF | 1.21 (1.76) | DTG + FTC/TDF vs EFV/FTC/TDF | 0.979 (.818–1.172) | 0.958 (.814–1.128) | |||

| P = .80 | P = .57 | ||||||

Abbreviations: Cl, confidence interval; DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; GMR, geometric mean ratio; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

The geometric SDs are on the multiplicative scale, not the additive scale.

This was a complete case analysis. No observations were eliminated for adjusted estimates: There are 114 DTG + FTC/TAF, 114 DTG + FTC/TDF, and 112 EFV/FTC/TDF in the maternal model; 101 DTG + FTC/TAF, 105 DTG + FTC/TDF, and 104 EFV/FTC/TDF in the infant model; and 95 DTG + FTC/TDF, 100 DTG + FTC/TDF, and 100 EFV/FTC/TDF in the infant:maternal ratio model.

Adjusted model of pregnant women folate trajectories includes treatment arm, time from entry to delivery (weeks), treatment arm x weeks, and precision variables (country, use of folic acid supplements, use of folic acid antagonists, mandatory folate fortification in country, and season when folate sample collected).

Adjusted models of infant RBC folate at birth and infant-to-maternal RBC folate ratio include treatment arm and precision variables (time from entry to delivery, country, use of folic acid supplements, use of folic acid antagonists, mandatory folate fortification in country, and season when folate sample collected).

Figure 1.

Box plot of red blood cell (RBC) folate concentrations at entry and delivery in pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus and in infants at birth by treatment arm. The y-axis is displayed on the logarithmic scale, but the actual RBC folate levels are displayed. Diamond is the mean. The box indicates median and interquartile range. The whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum data values, not including outliers. Outliers are those points >75th percentile + 1.5 × interquartile range or analogous points below. Abbreviations: DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; RBC, red blood cell; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

RBC Folate Level Trajectories in Pregnant Women

The estimated average adjusted maternal RBC folate trajectory per 4 weeks (aGMRT) was 1.016 (95% CI, .993–1.040), 0.996 (95% CI, .973–1.020), and 0.998 (95% CI, .965–1.012) for the DTG + FTC/TAF, DTG + FTC/TDF, and EFV/FTC/TDF arms, respectively (not shown). DTG + FTC/TAF was the only arm with estimated increasing aGMRT (positive slope on the loge outcome scale). Differences in aGMRT between arms were small (Table 2). The DTG + FTC/TAF arm had an estimated 2.0% higher aGMRT (based on the adjusted estimate of aGMRT/C: 1.020 [95% CI, .987–1.053]) compared to the DTG + FTC/TDF arm. Compared to the EFV/FTC/TDF arm, the DTG + FTC/TAF arm had an estimated 2.8% higher GMRT (aGMRT/C: 1.028 [95% CI, .995–1.062]), and the DTG + FTC/TDF arm had an estimated 0.8% higher aGMRT (aGMRT/C: 1.008 [95% CI, .975–1.042]). The results were similar when the 2 DTG arms were combined and compared with the EFV/FTC/TDF arm (aGMRT/C: 1.018 [95% CI, .989–1.048]; data not shown). Results were also similar when analyses were restricted to countries with mandatory folic acid fortification (data not shown).

Infant RBC Folate Concentrations

There were 5 infants whose mothers had no folate measurements available; data from these infants were only used in infant folate averages and models. Infant folate concentration was highest in the DTG + FTC/TAF arm (Table 2).

Differences between arms in geometric mean infant folate levels were also small. The DTG + FTC/TAF geometric mean of infant folate was estimated to be 1.9% higher (aGMR, 1.019 [95% CI, .884–1.174]) than the DTG + FTC/TDF arm and 7.5% higher (aGMR, 1.075 [95% CI, .932–1.240]) than the EFV/FTC/TDF arm (Table 2). Infant folate level in the DTG + FTC/TDF arm was estimated to be 5.5% higher (aGMR, 1.055 [95% CI, .915–1.217]) than the EFV/FTC/TDF arm. The results were similar with further adjustment for maternal delivery RBC folate and when the dolutegravir arms were combined and compared with EFV/FTC/TDF (aGMR, 1.065 [95% CI, .941–1.205]; data not shown).

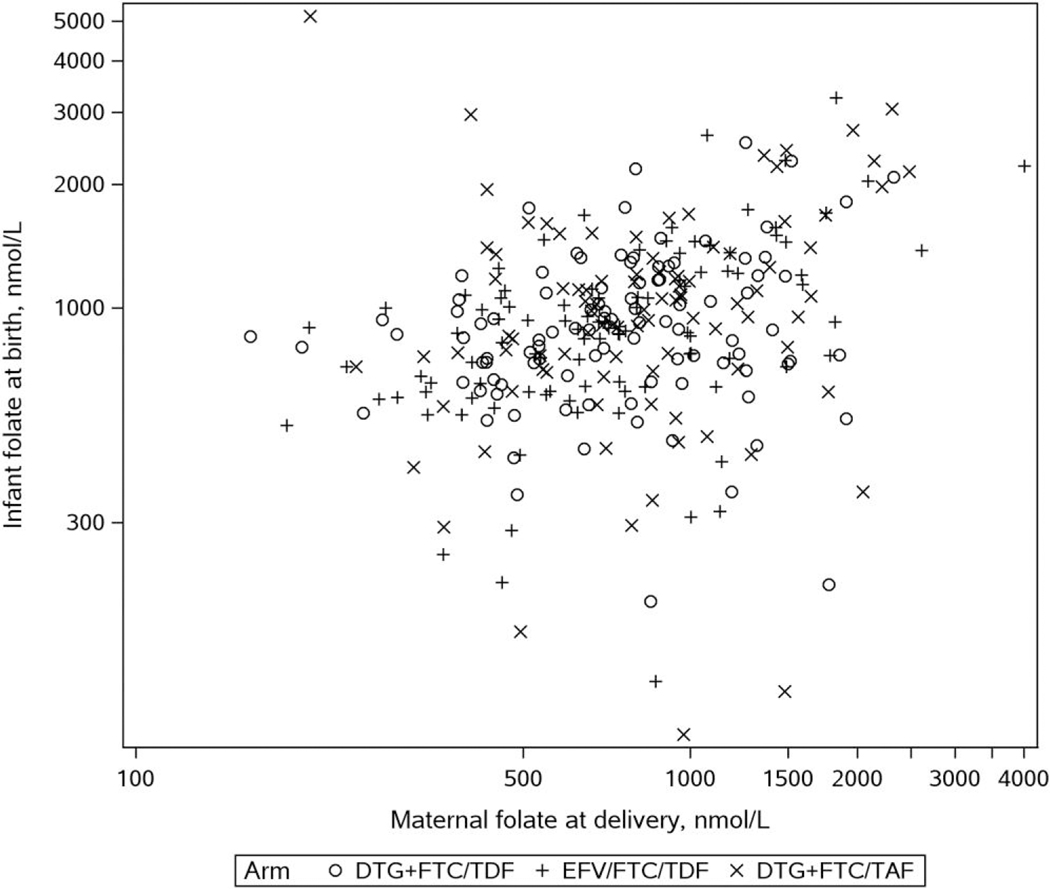

Modeling Infant-to-Maternal Delivery RBC Folate Ratio

Figure 2 is a graph of maternal folate at delivery and infant concentrations at birth. The geometric mean for infant-to-maternal folate ratio was 1.16 in the DTG + FTC/TAF, 1.19 in the DTG + FTC/TDF arm, and 1.21 in the EFV/FTC/TDF arms (Table 2). The DTG + FTC/TAF study arm had an estimated 3.7% lower geometric mean of the infant-to-maternal folate ratio (aGMR, 0.963 [95% CI, .816–1.136]) compared to the DTG + FTC/TDF study arm and a 7.7% lower (aGMR, 0.923 [95% CI, .781–1.089]) infant-to-maternal ratio compared to EFV/FTC/TDF. The infant-to-maternal folate ratio was 4.2% lower (aGMR, 0.958 [95% CI, .814–1.128]) in the DTG + FTC/TDF arm compared to EFV/FTC/TDF. The results were similar when the DTG arms were combined and compared to the EFV arm (5.9% lower; aGMR, 0.941 [95% CI, .816–1.085]; data not shown).

Figure 2.

Red blood cell folate concentrations in pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus at delivery versus infant concentrations at birth. Abbreviations: DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Folic Acid Supplementation

Ten percent of pregnant women received no folic acid supplements, 74% started supplements before study entry, and 16% started on study, with little variation by treatment arm (Table 3). No women started supplementation before conception. However, 90% started supplementation sometime during pregnancy. The earliest day was 9 days after conception and the latest was 235 days after conception with a median of 133 days (Q1, Q3: 101, 158). The distribution of folic acid supplementation start dates was similar between the treatment arms (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 3.

Factors That Impact Red Blood Cell Folate Concentrations by Treatment Arm

| Factor | Timinga | DTG + FTC/TAF (n = 114) | DTG + FTC/TDF (n = 114) | EFV/FTC/TDF (n = 112) | Total n = 340) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Timing of folic acid supplementation in pregnant women, relative to study entry and delivery | Never used for this pregnancy | 13 (11) | 13 (11) | 7 (6) | 33 (10) |

| Started supplements >28 d prior to entryb | 10 (9) | 11 (10) | 13 (12) | 34 (10) | |

| Started folic acid supplements ≤28 d prior to entry | 74 (65) | 68 (60) | 77 (69) | 219 (64) | |

| Started folic acid supplements between study entry and delivery | 17 (15) | 22 (19) | 15 (13) | 54 (16) | |

| Estimated gestational age, d, when starting folic acid supplementation in pregnant women | Median (Q1, Q3) | 131 (94, 157) | 127 (101, 153) | 138 (105, 162) | 133 (101, 158) |

| Minimum, maximum | 9, 235 | 23, 180 | 20, 216 | 9, 235 | |

| Timing of folate antagonist receipt in pregnant women, relative to study entry and delivery | Never received relative to this pregnancy | 67 (59) | 67 (59) | 65 (58) | 199 (59) |

| Started folic acid antagonists prior to study entry | 38 (33) | 37 (32) | 35 (31) | 110 (32) | |

| Started folic acid antagonists on study prior to delivery | 9 (8) | 10 (9) | 12 (11) | 31 (9) | |

| Mandatory folic acid fortification in country | Yes | 104 (91) | 103 (90) | 99 (88) | 306 (90) |

| Season of entry folate measurement in pregnant womenc,d | Spring | 41 (38) | 43 (40) | 44 (42) | 128 (40) |

| Summer | 26 (24) | 28 (26) | 22 (21) | 76 (24) | |

| Fall | 22 (21) | 20 (19) | 22 (21) | 64 (20) | |

| Winter | 18 (17) | 17 (16) | 16 (15) | 51 (16) | |

| No folate measurement | 7 | 6 | 8 | 21 | |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Timing of folic acid supplementation was described as estimated gestational age at initiation and was also categorized in relation to study entry (none before entry, started >28 days before entry, started ≤28 days prior to entry) and from entry through delivery (never used before or during the study, started >28 days before entry, started ≤28 days prior to study entry, started on study prior to delivery). Timing of folate antagonist medication receipt was also categorized at entry (no use before entry, started prior to entry) and from entry through delivery (never took folate antagonists, started prior to study entry, started on study prior to delivery). Folate antagonist medications taken include trimethoprim, pyrimethamine, and dapsone.

No women started folic acid supplementation before conception.

Denominator for each regimen to determine percentage by season: DTG + FTC/TAF (n = 107), DTG + FTC/TDF (n = 108), EFV/FTC/TDF (n = 104) (total N = 319). Women without an entry folate measurement were excluded from the denominators.

Start of each season was 20 March for spring, 21 June for summer, 23 September for fall, and 21 December for winter. For countries south of the equator, these were reversed. Brazil was classified as south and Uganda as north of the equator.

Compared to those with no folic acid supplementation prior to entry, those with use >28 days before entry had higher mean entry RBC folate concentrations (aGMR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.20–1.72]) (Supplementary Table 1). At delivery, the geometric mean of RBC folate was 20% higher in women who started >28 days before entry (aGMR, 1.20 [95% CI, .96–1.50]), 15% higher in those that started <28 days before entry (aGMR, 1.15 [95% CI, .98–1.35]), and 13% higher in those who started supplementation between entry and delivery (aGMR, 1.13 [95% CI, .91–1.40]), compared to those who did not use folic acid supplements. Infant folate concentrations were also higher in newborns whose mothers started >28 days prior to study entry (aGMR, 1.31 [95% CI, .99–1.72]), mothers who started ≤28 days before entry (aGMR, 1.17 [95% CI, .97–1.42]) and mothers who started on study (aGMR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.01–1.62]), each compared to mothers who had no recorded use of folic acid supplements. In contrast, there were no detectable patterns for the aGMR of infant-to-maternal folate ratio by each category of timing of maternal folic acid supplementation compared to no supplementation.

Folic Acid Antagonist Use

Little more than half of the women (59%) had no known receipt of 1 or more folate antagonists, 32% started at least 1 folate antagonist prior to study entry, and 9% started while on study (Table 3). The medications used by women were either cotrimoxazole, pyrimethamine, or dapsone. Folate concentrations were similar between those who used versus did not use folate antagonists. However, 95% CIs were wide (Supplementary Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to evaluate RBC folate concentrations and transplacental transfer of folate in pregnant women initiating DTG in pregnancy. We did not identify clinically meaningful differences in maternal RBC folate concentration trajectory during pregnancy, infant RBC folate at birth, or infant-to-mother RBC folate ratio at birth/delivery between pregnant women starting DTG- versus EFV-based ART (nor TAF vs TDF). Overall, these findings are reassuring that DTG treatment in pregnancy does not impact folate concentrations in pregnant mothers or their infants differentially among treatment groups. Our findings also suggest that DTG does not inhibit cellular uptake or transplacental passage of folate.

Despite the fact that 90% of IMPAACT 2010/VESTED study participants lived in countries with folic acid fortification programs, >40% of women had insufficient RBC folate concentration, with 6% deficient at enrollment and 5% deficient at delivery (given the small number of women enrolling in nonfortified countries, it was not feasible to explore folate levels by this factor as other confounding factors could be at play). For comparison, in the United States general population post–folic acid fortification, about 20% of women of reproductive age have suboptimal RBC folate concentrations with deficiency <1% [20, 22]. This suggests that existing folic acid fortification programs are not reaching populations represented in this study at levels sufficient for optimal NTD prevention [4, 23]. RBC folate concentration data from Africa are limited [9] (nearly 80% of our participants were from Africa). Many countries with mandated fortification programs, while reducing NTDs overall, do not meet the needs of specific populations due to limited implementation or poor coverage where fortified foods do not reach vulnerable groups, especially in rural areas [9]. In some settings individuals mostly consume food from their farms, which may not be fortified. In our study, the median gestational age at which women initiated folic acid supplements was 18 weeks and similar across treatment arms; this is long past the time that the neural tube closes (week 4 of pregnancy). Almost half of women in this study had increased risk for NTD related to insufficient folate concentrations caused by insufficient intake of folic acid before neural tube closure because of late initiation of supplementation and suboptimal folic acid fortification. Effective folic acid fortifications programs are beneficial not only for averting NTDs but also for other health outcomes including folate deficiency anemia [9, 24].

RBC folate concentrations increase gradually after initiation of supplementation, and homeostasis is reached 36 months after initiation of continuous intake [25]. In contrast to serum folate, which shows folate intake in the last hours to days, the RBC folate concentration represents an average of folate stores in RBCs over the last approximately 120 days [8]. IMPAACT 2010/VESTED participants started folic acid supplementation at median 18 weeks’ gestation and not randomized, too late to alter folate sufficiency substantially by delivery (although concentrations were higher in women who started folic acid supplementation >28 days before entry). Median folate concentration did not increase from entry to follow-up in any arm, which might be explained by factors including hemodilution and transplacental transfer of folate to the fetus [26, 27]. Folic acid supplementation is recommended before and during early pregnancy for prevention of NTDs and continued throughout pregnancy and lactation to prevent depletion and megaloblastic anemia [28]. Maternal folate status is known to strongly predict the newborn status and protect infants from folate deficiency and megaloblastic anemia [29–31]. Reassuringly, overall there was no decrease in folate from enrollment to delivery as would be expected in pregnancy without folic acid supplementation. There were no NTDs reported in IMPAACT 2010/VESTED.

A major strength of this study is that it was conducted within a randomized controlled clinical trial, balancing the distribution of baseline factors at the time of randomization across treatment arms. Another strength is the systematic longitudinal measurement of RBC folate using optimal laboratory methods, in both pregnant women and newborns. The ability to pair mothers and their infants enables determination that there was active transport of folate across the placenta to the fetus throughout the end of pregnancy. This is reassuring given the number of adverse consequences of low folate to a developing fetus [8]. Our study has limitations. As previously mentioned, there are insufficient numbers to show the impact of treatments in the absence of folic acid intake. RBC folate concentrations were chosen for analysis as the folate status indicator due to their use as a stable indicator of status, low variance, and necessity for both transport across the gut and into the bone marrow and the RBC [9, 31]. Considering the hypothesized mechanism of DTG disruption of folate transport [13, 15], serum indicators have high variance due to very recent folate intake and limited processing and as such are not ideal for this analysis [9, 2]. While we initially hypothesized that DTG would affect cellular uptake of folate, our findings suggest that cellular uptake of folate and transport of folate to the infant do not differ in pregnant women starting DTG- versus EFV-based ART (nor TAF vs TDF) after the first trimester.

Data availability.

Per the Network Manual of Procedures, Section 19.7: “The data cannot be made publicly available due to the ethical restrictions in the study’s informed consent documents and in the IMPAACT Network’s approved human subjects protection plan; public availability may compromise participant confidentiality. However, data are available to all interested researchers upon request to the IMPAACT Statistical and Data Management Center’s data access committee (email address: sdac.data@fstrf.org) with the agreement of the IMPAACT Network.”

Supplementary Material

Financial support.

Overall support for IMPAACT was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the NIH, under award numbers UM1AI068632-15 (IMPAACT Leadership and Operations Center), UM1AI068616-15 (IMPAACT Statistical and Data Management Center, D. L. J., P. D., S. B.) and UM1AI106716-15 (IMPAACT Laboratory Center), and by NICHD contract number HHSN275201800001I. S. L. was also supported by K24 AI131928 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

P. D. and S. B. have received funds from ViiV/GSK that were paid to Harvard.

Disclaimer.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Code availability.

The analytic code, such as in supplementary material, is available upon reasonable request.

Potential conflicts of interest.

All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Clinical Trials Registration.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

References

- 1.Zash R, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-tube defects with dolutegravir treatment from the time of conception. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:979–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, et al. Neural-tube defects and antiretroviral treatment regimens in Botswana. New Engl J Med 2019; 381:827–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zash R, Diseko M, Holmes LB, et al. Neural tube defects and major external structural abnormalities by antiretroviral treatment regimen in Botswana: 2014–2022. In: International AIDS Society, Brisbane, Australia, 23–26 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crider KS, Devine O, Hao L, et al. Population red blood cell folate concentrations for prevention of neural tube defects: Bayesian model. BMJ 2014; 349:g4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alonso-Aperte E, Varela-Moreiras G. Drugs-nutrient interactions: a potential problem during adolescence. Eur J Clin Nutr 2000; 54(Suppl 1):S69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAuley JW, Anderson GD. Treatment of epilepsy in women of reproductive age: pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002; 41:559–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, Berry RJ, Hobbs CA, Hu DJ. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects: National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009; 163:978–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey LB, Stover PJ, McNulty H, et al. Biomarkers of nutrition for development—folate review. J Nutr 2015; 145:1636–80S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crider KS, Qi YP, Yeung LF, et al. Folic acid and the prevention of birth defects: 30 years of opportunity and controversies. Annu Rev Nutr 2022; 42:423–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabrera RM, Souder JP, Steele JW, et al. The antagonism of folate receptor by dolutegravir: developmental toxicity reduction by supplemental folic acid. AIDS 2019; 33:1967–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandiwana NC, Chersich M, Venter WDF, et al. Unexpected interactions between dolutegravir and folate: randomized trial evidence from South Africa. AIDS 2021; 35:205–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohan H, Lenis MG, Laurette EY, et al. Dolutegravir in pregnant mice is associated with increased rates of fetal defects at therapeutic but not at supratherapeutic levels. EBioMedicine 2021; 63:103167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Zhang X, Mudunuru J, et al. Clinical extrapolation of the effects of dolutegravir and other HIV integrase inhibitors on folate transport pathways. Drug Metab Dispo 2019; 47:890–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barlow-Mosha LN, Ahimbisibwe GM, Chappell E, et al. Effect of dolutegravir on folate, vitamin B12 and mean corpuscular volume levels among children and adolescents with HIV: a sub-study of the ODYSSEY randomized controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc 2023; 26:e26174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lockman S, Brummel SS, Ziemba L, et al. Efficacy and safety of dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide fumarate or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate HIV antiretroviral therapy regimens started in pregnancy (IMPAACT 2010/VESTED): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021; 397:1276–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and Its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B(6), folate, vitamin B(12), pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeiffer CM, Zhang M, Lacher DA, et al. Comparison of serum and red blood cell folate microbiologic assays for national population surveys. J Nutr 2011; 141:1402–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molloy AM, Scott JM. Microbiological assay for serum, plasma, and red cell folate using cryopreserved, microtiter plate method. Methods Enzymol 1997; 281:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Broin S, Kelleher B. Microbiological assay on microtitre plates of folate in serum and red cells. J Clin Pathol 1992; 45:344–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tinker SC, Hamner HC, Qi YP, Crider KS. U.S. women of childbearing age who are at possible increased risk of a neural tube defect–affected pregnancy due to suboptimal red blood cell folate concentrations, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007 to 2012. Birth Defects Res A Clin Molec Teratol 2015; 103:517–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global Fortification Data Exchange. Introduction Available at: https://fortificationdata.org. Accessed 7 August 2023.

- 22.Pfeiffer CM, Sternberg MR, Zhang M, et al. Folate status in the US population 20 y after the introduction of folic acid fortification. Am J Clinical Nutr 2019; 110: 1088–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordero AM, Crider KS, Rogers LM, Cannon MJ, Berry RJ. Optimal serum and red blood cell folate concentrations in women of reproductive age for prevention of neural tube defects: World Health Organization guidelines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:421–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Crider KS, Yeung LF, et al. Periconceptional folic acid use prevents both rare and common neural tube defects in China. Birth Defects Res 2022; 114:184–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crider KS, Devine O, Qi YP, et al. Systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship between folic acid intake and changes in blood folate concentrations. Nutrients 2019; 11:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milman N, Byg KE, Hvas AM, Bergholt T, Eriksen L. Erythrocyte folate, plasma folate and plasma homocysteine during normal pregnancy and postpartum: a longitudinal study comprising 404 Danish women. Eur J Haematol 2006; 76:200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Úbeda N, Reyes L, González-Medina A, Alonso-Aperte E, Varela-Moreiras G. Physiologic changes in homocysteine metabolism in pregnancy: a longitudinal study in Spain. Nutrition 2011; 27:925–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura T, Picciano MF. Folate and human reproduction. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83:993–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay G, Clausen T, Whitelaw A, et al. Maternal folate and cobalamin status predicts vitamin status in newborns and 6-month-old infants. J Nutr 2010; 140:557–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin H, Lindblad B, Norman M. Endothelial function in newborn infants is related to folate levels and birth weight. Pediatrics 2007; 119:1152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallis DBJ, Shaw GM, Lammer EJ, Rinnell RH. Folate-related birth defects: embryonic consequences of abnormal folate transport and metabolism. In: Bailey L, ed. Folate in health and disease. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 2009:155–78. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Per the Network Manual of Procedures, Section 19.7: “The data cannot be made publicly available due to the ethical restrictions in the study’s informed consent documents and in the IMPAACT Network’s approved human subjects protection plan; public availability may compromise participant confidentiality. However, data are available to all interested researchers upon request to the IMPAACT Statistical and Data Management Center’s data access committee (email address: sdac.data@fstrf.org) with the agreement of the IMPAACT Network.”