Abstract

Background

Traumatic duodenal rupture is rare which accounts for only 2–10% of all Blunt abdominal trauma. The purpose of this study was to investigate the experience of diagnosis and treatment of traumatic duodenal rupture in children.

Methods

This was a retrospective case series study. Clinical data were collected from three children suffering from a traumatic duodenal rupture who received surgical treatment in our hospital from January 2013 to January 2023. Demographic characteristics, trauma mechanism, physical examination, auxiliary examination, operation timing and plan, postoperative management and follow-up of included patients were described. Summarize the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of this type of injury.

Results

Three children (1 male and 2 females) with duodenal rupture due to traumatic abdominal injury were included in the study, with average age of 8.2 years (range 2.75–13.25 years). Among them, One child was injured by heavy objects. The other two children had lumbar fracture and seat belt sign. All three patients underwent emergency operation within 24 h, and recovered well after surgery. No related complications seen during follow-up.

Conclusions

Duodenal rupture is a rare but fatal disease. Early identification and active abdominal exploration can reduce the incidence of related complications and mortality in children with blunt abdominal injury, especially those with seat belt sign. Simultaneously, the standardized postoperative management is significant for the cure of children.

Keywords: Children, Duodenal rupture, Diagnosis, Surgery, Postoperative management

Background

Blunt trauma is the leading cause of death in children, accounting for 90% of injuries [1]. Abdominal trauma sustained from motor vehicle crashes (MVC), falls, sports-related injuries, or other causes can result in substantial mortality from solid organ or hollow viscus injury [2, 3]. Due to the immature musculoskeletal system in children, severe damage to intra-abdominal organs may occur after blunt abdominal trauma. In addition, the unique anatomical location of the duodenum, its injury is relatively rare in clinical practice, accounting for only 2–10% of all abdominal trauma [4]. However, the consequences of duodenal rupture can be devastating, and delayed treatment may give rise to serious complications and mortality [5]. Timely and effective diagnosis and treatment is crucial in clinical work. Shorter operative time and simple and rapid damage control surgery seem to be the key factors affecting the prognosis of pancreaticoduodenal injuries [6]. The purpose of this study was to analyze the clinical data and treatment outcomes of children with traumatic duodenal rupture admitted to our department from 2013 to 2023, thereby providing a single-center experience of this disease.

Methods

General patient data

Clinical data of the patient were collected, including age, gender, weight, trauma mechanism, vital signs, physical findings and symptoms at admission, complete examination and results, type and time of surgical intervention, complications, length of stay, postoperative management and treatment results. In this retrospective study, three children (1 male and 2 females) with traumatic duodenal rupture were admitted to our hospital between 2013 and January 2023, with an average age of 8.2 years (range 2.75–13.25 years). Case 1 who was accidentally struck by a table, resulting in abdominal trauma. The other two patients (Case 2 and 3) were both rear seat passengers suffering from motor vehicle collision with abdominal wall bruising caused by seat belts. All patients were admitted to our hospital for treatment at the first time and underwent surgery within 24 h after the injury. It was confirmed that the perforation site was at the junction of descending and horizontal part of duodenum in all 3 cases.(Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data, surgical management, and outcomes of three children with traumatic duodenal rupture

| Case | Age(years) | Sex | Cause of injury | Clinical manifestations | Abdominal tenderness | Radiography (free air under the diaphragm) | B-mode ultrasound (effusion) | Time to operation in our hospital after injury (hours) | Rupture site | Grades of duodenal injury | Surgical approach | Postoperative complications and treatment | Hospital stay (days) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.9 | Female | Table crush | Abdominal pain | + | - | 8.1 × 6.7 × 3.8 cm | 1.5 | descending section and horizontal section of duodenum completely ruptured, 6 mm in diameter | II | Repair of perforation of posterior duodenal wall | No | 17 | well |

| 2 | 8.6 | Male | Motor vehicle accident | Abdominal pain, vomiting | + | - | 9.8 × 6.2 × 3.5 cm | 15 | descending section and horizontal section of duodenum completely ruptured, 3 mm in diameter | II | Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy + Repair of perforation of posterior duodenal wall | Vomit | 19 | well |

| 3 | 13.4 | Female | Motor vehicle accident | Abdominal pain, vomiting, fever | + | - | 7.8 × 3.2 cm | 21 | descending section and horizontal section of duodenum completely ruptured, 4 mm in diameter | II | Repair of perforation of posterior duodenal wall | No | 19 | well |

Diagnosis and treatment

All patients presented with abdominal pain and tenderness after injury, with one patient experiencing vomiting and the other vomiting and fever in the study. Abdominal X-ray showed no free air under the diaphragm in all children. Abdominal ultrasound showed irregular abdominal effusion on the right retroperitoneum. Two of children underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, indicating varying degrees of duodenal injury and intraabdominal fluid (Fig. 1; Table 1). Laboratory results showed elevated levels of white blood cells (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), α-amylase and lipase (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Axial CT scan image showing rupture of the junction of the descending and horizontal segments of the duodenum with free intra-peritoneal free fluid.

Permission has been obtained to publish this figure. Arrows: Rupture of the junction of D2 and D3.

CT, computed tomography

Table 2.

Laboratory examination of the patient at admission and discharge

| Case\Parameters | Admission | Discharged |

|---|---|---|

| WBC(×109/L) | ||

| 7.49 | 7.13 | |

| 9.42 | 4.46 | |

| 22.06 | 10.01 | |

| CRP(mg/L) | ||

| 3.73 | 0.93 | |

| 51.5 | 2 | |

| 8.3 | 1.8 | |

| HB(g/L) | ||

| 134 | 115 | |

| 136 | 123 | |

| 119 | 118 | |

| α-amylase(u/L) | ||

| 76 | - | |

| 186 | 110 | |

| 448 | 68 | |

| Lipase(u/L) | ||

| - | - | |

| 148 | 38 | |

| 514 | 20 |

*White blood cells(WBC); C-reactive protein(CRP); Hemoglobin(HB)

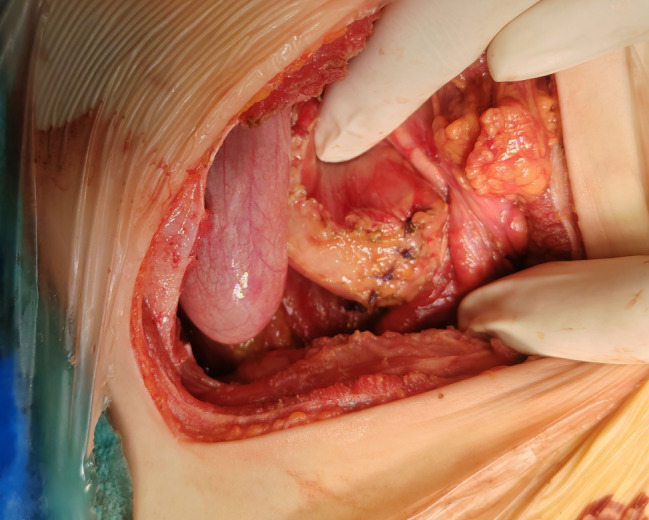

Based on preoperative signs and examinations, three patients suspected varying degrees of duodenal trauma, and therefore underwent emergency exploratory laparotomy. During the surgery, a complete rupture was diagnosed at the junction of the descending and horizontal segments of the duodenum, accompanied by a large accumulation of dark green fluid and periduodenal inflammation (Figs. 1 and 2). All patients were submitted to one-stage duodenal repair (Fig. 3). Furthermore, case 2 underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy examination before and after surgery.

Fig. 2.

Arrows: Intraoperative findings of the rupture in Duodenum

Fig. 3.

Manifestations after intraoperative duodenal repair

Results

All duodenal ruptures in this study were classified as grade II injury according to the classification of duodenal injuries developed by the American Association of Trauma Surgeons [7]. After surgery, the children were strictly fasting, and three patients underwent postoperative indwelling of gastric tubes for 8.7 ± 1.5 days and abdominal drainage tubes for 9.7 ± 2.5 days. One child developed vomiting after five days of eating and improved after fasting for two days. The bladder catheter was removed two days after surgery. The postoperative antibiotics was 8.7 ± 1.5 days, omeprazole was 11 ± 4.6 days, and parenteral nutrition 6 ± 2.6 days (Table 3). The average hospital stay was 18.3 ± 1.2 days (Table 1). All patients recovered well after surgery, and there were no complications such as anastomotic stenosis, intestinal fistula, wound infection or dehiscence.

Table 3.

Postoperative management

| Case | stomach tube (d) | abdominal drainage tube (d) | foley catheter (d) | antibiotic (d) | omeprazole(d) | parenteral nutrition (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 16 | 3 |

| 2 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| 3 | 7 | 12 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| mean ± SD | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 9.7 ± 2.5 | 2 | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 11 ± 4.6 | 6 ± 2.6 |

Discussion

The duodenum, primarily a retroperitoneal structure, is uncommon in children with blunt closed abdominal injuries, with an incidence of only 2–10% [4]. But overall mortality is almost 16–18% for duodenal injuries [8]. Duodenal injuries in children are usually closed rather than penetrating unlike adults. Because of the unique anatomical and physiological function of the duodenum, the harm caused by injury may be enormous. When the child’s abdomen is subjected to blunt violence, the descending and horizontal parts of the duodenum are compressed and collided with the spine to form a transient closed intestinal segment, and a sudden increase in internal pressure can lead to duodenal rupture [9, 10]. In addition, it can be accompanied by peripheral vascular damage, leading to hemorrhagic shock. The leakage of pancreatic juice and bile can cause serious erosion and damage to surrounding tissues and organs, and a series of complications may occur due to infection. The most children cannot accurately describe the history or symptoms after injury. Moreover, intestinal injury is relatively rare, and duodenal rupture lacks typical symptoms and signs, as well as specificity in imaging, which brings great difficulties to clinical diagnosis and accurate identification. Therefore, physician should conduct a careful history collection and physical examination. Early identification, timely and effective treatment measures, and standardized management after surgery are all very important.

Seat belt offers protection as it prevents the passenger from being thrown out, when involved in an accident due to high speed vehicle. Ironically, the seat belt restraint itself may be the cause for blunt injury abdomen in a road traffic accident. Garrett and Braunstein [11] had already described the definition of seat belt syndrome, including lumbar spine fractures, abdominal wall bruising (AWB) and intra-abdominal injuries in 1962. In our series, two children suffered from abdominal trauma caused by a collision between vehicles, and both wore seat belts during the accident. After the injury, the child had symptoms of abdominal tenderness and tension, and physical examination showed abrasions on the abdomen. Upon admission to hospital, abdominal X-rays examination revealed no free intraperitoneal gas, but ultrasound showed free fluid in the retroperitoneum. X-ray as a diagnostic tool for viscus perforation is less sensible than CT, ultrasound its operator dependent and takes more time to do it and has less diagnostic sensibility. ECO-FAST (focused assessment sonography for trauma) is useful in adult decision making, but in children, with a usually more conservative approach is less useful. In general CT scan will give you more information and in less time [7].

Our team highly suspected the presence of intestinal injury based on the mechanism of injury, symptoms, and auxiliary examinations, and therefore performed emergency surgical laparotomy exploration within 24 h. Edema was found in the peritoneum and right mesenteric tissue of the colon during intraoperative, with yellow green turbid fluid accumulation visible, confirming duodenal rupture. In 1969, a study reported a case of duodenal rupture caused by a seat belt in a traffic accident. Emergency surgical exploration and repair were performed promptly, and the patient was stable after surgery and discharged on the sixth day [12]. Among the 53 children reported in Paris who had AWB after a vehicle collision, 55% had intra-abdominal injuries, and 19% needed therapeutic laparotomy. It is strongly recommended that the presence of an AWB after MVC should be highly suspected of intra-abdominal injury. Abdominal exploration should be considered in patients with abdominal bruising, pulse rates more than 120 per minute, ultrasound or CT evidence of abdominal fluid and associated lumbar fracture [13]. Santschi’s research also shows that the estimated incidence of seat belt syndrome in traffic accidents is 1/1000 [14]. In addition, Luo et al. [5] recently reported four children suffering from a traumatic duodenal rupture. The diagnosis was missed in one of the children during the initial surgical exploration, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. During the second surgical repair and recovery process, drug-resistant bacterial infection, wound infection, dehiscence, and intestinal fistula occurred. The hospital stay was significantly prolonged. However, the four children in this study underwent timely laparotomy exploration and duodenal repair by the team after admission, with an average hospital stay of 18.3 ± 1.2 days and no postoperative complications. Therefore, in children with seat belt strangulation marks, the damage to abdominal organs cannot be ignored, and emergency surgical exploration can reduce the occurrence of postoperative complications.

Laboratory examination can play a certain role in prompting. Some children with pancreatic injury may exhibit significant elevations of amylase and lipase in the blood and urine, but the results cannot be used to determine whether there is intestinal injury [15]. In our case, the children showed increased inflammatory indexes, and the amylase and lipase levels in cases 2 and 3 were elevated, suggesting possible pancreatic injury. Moreover, case 2 showed board-like rigidity of the abdomen, and combined with the imaging examination of the child, exploratory laparotomy was very necessary. All the 3 patients underwent surgical treatment within 24 h after admission, their postoperative condition remained stable with good recovery, with no related complications. In addition, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed before operation in case 2. Diffuse mucosal ulcer in the descending duodenum, covered with pus moss, filth and bile, can be seen, and perforation due to trauma cannot be ruled out. Combining the results of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with exploratory laparotomy seems to be more favorable evidence, especially for children with atypical symptoms and auxiliary examinations, which can to some extent avoid blind surgery causing greater harm.

Duodenal rupture may lead to severe septic shock in children, so standardized postoperative management is also very important [5]. In this study, three patients fasted for at least one week after surgery, gradually transitioning from parenteral nutrition to enteral based on their condition. All patients were placed with gastrostomy tube, abdominal drainage tube, and bladder catheters for observation of postoperative intestinal patency and anastomotic healing. The application of empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics is very necessary. Therefore, the postoperative team prefers third or higher-generation antibiotics for treatment, and adjusts the plan in timely based on drug sensitivity tests and the patient’s condition. In addition, due to the unique physiological characteristics of duodenal fluid, the incidence of postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage and stenosis is relatively high. So it is necessary to use somatostatin and proton pump inhibitors to inhibit the secretion of digestive fluid. Inviting the clinical nutrition department to develop personalized plans for recovery is crucial for multi-team collaboration.

Conclusions

The difficulty of closed abdominal trauma in children lies in early and timely identification of internal abdominal organ damage. Therefore, the possibility of duodenal rupture should be highly vigilant for children, especially those with the sign of safety belt. Based on the patient’s symptoms, signs and relevant auxiliary examinations, emergency laparotomy exploration should be conducted without delay. Furthermore, preoperative and postoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is feasible to further identify intestinal injury and postoperative recovery.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the children and their families who participated in this study, as well as all the surgeons. We are also grateful for the medical and equipment support provided by Shenzhen Children’s Hospital.

Author contributions

ZC was mainly involved in the patient treatment and data collection as well as writing of the manuscript. YLZ and JHG prepared figures and tables. ZGW and QF were involved in patient treatment/follow-up. BW was responsible for the revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was in part supported by Guangdong High-level Hospital Construction Fund, Shenzhen Science and Technology Program(No. JCYJ20210324134202007), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program(No. KCXFZ20211020164544008).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Shenzhen Children’s Hospital. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gaines BA, Ford HR. Abdominal and pelvic trauma in children. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(11 Suppl):S416–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bixby SD, Callahan MJ, Taylor GA. Imaging in pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. Semin Roentgenol. 2008;43(1):72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaines BA. Intra-abdominal solid organ injury in children: diagnosis and treatment. J Trauma. 2009;67(2 Suppl):S135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutierrez IM, Mooney DP. Operative blunt duodenal injury in children: a multi-institutional review. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(10):1833–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo Y, He X, Geng L, Ouyang R, Xu Y, Liang Y, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of traumatic duodenal rupture in children. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonacci N, Di Saverio S, Ciaroni V, Biscardi A, Giugni A, Cancellieri F, et al. Prognosis and treatment of pancreaticoduodenal traumatic injuries: which factors are predictors of outcome? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18(2):195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malhotra A, Biffl WL, Moore EE, Schreiber M, Albrecht RA, Cohen M, et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: diagnosis and management of duodenal injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(6):1096–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cogbill TH, Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Hoyt DB, Jurkovich GJ, Morris JA, et al. Conservative management of duodenal trauma: a multicenter perspective. J Trauma. 1990;30(12):1469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cocke WM Jr., Meyer KK. Retroperitoneal duodenal rupture. Proposed mechanism, review of literature and report of a case. Am J Surg. 1964;108:834–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McWhirter D. Duodenal rupture following trauma in a child. Scott Med J. 2011;56(2):120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrett JW, Braunstein PW. The seat belt syndrome. J Trauma. 1962;2:220–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buxton B. Rupture of the Duodenum produced by a Safety Belt. Aust N Z J Surg. 1972;38(4):315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paris C, Brindamour M, Ouimet A, St-Vil D. Predictive indicators for bowel injury in pediatric patients who present with a positive seat belt sign after motor vehicle collision. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(5):921–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santschi M, Lemoine C, Cyr C. The spectrum of seat belt syndrome among Canadian children: results of a two-year population surveillance study. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13(4):279–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fakhry SM, Watts DD, Luchette FA, Group EM-IHVIR. Current diagnostic approaches lack sensitivity in the diagnosis of perforated blunt small bowel injury: analysis from 275,557 trauma admissions from the EAST multi-institutional HVI trial. J Trauma. 2003;54(2):295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.