Abstract

Hip arthroscopy has emerged as the primary surgical intervention for Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome (FAIS), a common cause of hip pain in young adults, particularly athletes. This narrative review examines the long-term outcomes, complications, and debates surrounding arthroscopic management of FAIS. Key findings include sustained improvements in patient-reported outcomes, return to sport, and functional recovery, particularly in younger patients and those with cam-type FAIS. However, some patients may eventually require total hip arthroplasty (THA), highlighting the variability in long-term durability. Complications, though infrequent, remain a significant concern, with the most common being transient neuropathy due to prolonged traction, heterotopic ossification, and iatrogenic cartilage damage. Recent studies emphasize the importance of patient selection, with younger patients, those with capsular closure, and those without pre-existing osteoarthritis showing superior outcomes. Additionally, sex-based differences suggest females may experience higher complication rates, though they often report better functional improvements post-surgery. Areas of ongoing debate include the role of labral debridement versus repair, the optimal management of mixed-type FAIS, and the potential benefits of adjunctive procedures such as ligamentum teres debridement. Future research should focus on refining surgical techniques and identifying patient-specific factors to further optimize outcomes. Despite its complexities, hip arthroscopy remains an effective treatment for FAIS, though individualized treatment plans are crucial to addressing the unique needs of each patient. By synthesizing current evidence, this review aims to guide clinicians in optimizing FAIS management and identifying areas for future research.

Keywords: Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS), Hip arthroscopy, Osteoplasty, Labral repair, Cam impingement, Pincer impingement, Radiographic imaging, Patient outcomes, Acetabuloplasty, Femoral head-neck junction, Acetabular rim trimming, MR arthrography, Rehabilitation protocols, Hip joint biomechanics

1. Introduction

Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS) is a chronic musculoskeletal condition characterized by morphological abnormalities of the acetabulum and femoral head, resulting in aberrant biomechanical interactions.1 This syndrome affects a significant proportion of patients presenting with hip pain, with approximately 61 % of individuals reporting hip discomfort in the absence of osteoarthritis (OA) being diagnosed with FAIS.2 The condition predominantly afflicts younger adults and is recognized as a substantial risk factor for the development of degenerative hip arthritis.

FAIS manifests in three distinct morphological variants: Cam-type (characterized by femoral head-neck junction abnormalities), Pincer-type (involving acetabular rim overgrowth), and mixed-type (a combination of Cam and Pincer morphologies).3 The mixed-type variant is the most prevalent, accounting for approximately 85 % of FAIS cases.4 While initial descriptions of FAIS were provided by Ganz et al.5 and Sankar et al.,6 a comprehensive diagnostic consensus was not established until 2016, when 25 clinical societies endorsed a standardized definition.7

The clinical presentation of FAIS is characterized by specific osseous deformities and a constellation of signs and symptoms. Patients typically report pain localized to the groin or hip region, often radiating to the knees, thighs, and buttocks. Additional symptoms may include sensations of locking, stiffness, catching, and clicking in the affected area.8 Objective clinical findings frequently include decreased range of motion (ROM), particularly in internal rotation and flexion.9

Management strategies for FAIS encompass both non-surgical and surgical interventions. Conservative approaches include physical therapy, analgesic medication, activity modification, and intra-articular hip injections. Surgical options, typically considered when conservative measures prove ineffective, include various open and arthroscopic procedures.8,10 Among surgical interventions, hip arthroscopy has emerged as a widely adopted minimally invasive technique. This procedure aims to address joint morphology while simultaneously addressing articular cartilage and labral pathology.11,12 Current evidence suggests that hip arthroscopy yields superior outcomes in terms of pain reduction and restoration of physical function compared to alternative treatment modalities.13 Moreover, hip arthroscopy demonstrates a favorable safety profile, with minor complications occurring in 4.5–7.9 % of cases and major complications in less than 1 % of procedures.12

This narrative review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of FAIS, covering its etiology, diagnostic criteria, management options, outcomes, and future directions. It explores genetic and environmental risk factors, evaluates clinical and radiological diagnostic methods, and discusses surgical and non-surgical interventions, with a focus on hip arthroscopy. The review also examines complications, rehabilitation protocols, and emerging trends in FAIS research. By synthesizing current evidence and clinical perspectives, it seeks to offer an up-to-date resource for healthcare professionals, identify knowledge gaps, and guide future research to advance FAIS understanding and patient care.

2. Pathophysiology of FAIS

The acetabulofemoral joint plays a central role in the pathophysiology of FAIS. The condition arises from improper functioning of this ball-and-socket joint, which articulates the femoral head and acetabulum (Fig. 1). The acetabular labrum, a key component, provides joint depth. A fibrous capsule surrounds the joint and intraarticular structures, with ligaments formed by capsular thickening providing stability.8 Bony abnormalities in the acetabulum and femur can cause impingement and pain during movement. Developmental anomalies, such as bone spurs along the acetabulum or femur, may contribute to altered bone anatomy, disrupting normal articulation and causing impingement and pain 14. Over time, the stress and friction from abnormal articulation can lead to joint depth disintegration, fibrous capsule damage, labral injury, and instability. If untreated, these damages may progress to osteoarthritis (OA).15

Fig. 1.

The figure demonstrates the pathophysiology of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS), where abnormal contact between the femoral head and acetabulum leads to joint damage. FAIS can progress to osteoarthritis as repetitive impingement causes cartilage breakdown, joint space narrowing, and the development of bone spurs.

Both intrinsic and developmental factors contribute to FAIS pathogenesis, including genetic factors, pediatric hip disease, repetitive hip movements, and prior surgical procedures.4 Recent studies suggest that individuals engaged in high-impact sports during adolescence have a higher incidence of FAIS upon skeletal maturity compared to non-athletic individuals.1

In cam-type FAI, femoral anatomy abnormality is the primary cause. The non-spherical femoral head disrupts normal rotation within the acetabulum.16 Typically, cam-type FAI presents with loss of sphericity due to excessive osteochondral extension at the head-neck junction. Siebenrock et al. proposed that this abnormality results from atypical femoral head epiphysis extension due to physeal scar extension in impingement cases.17 Cam abnormalities develop during skeletal growth and are influenced by high-impact sports activities. Agricola et al. reported an increased prevalence of cam deformity in young male soccer players (14.4 years) over a 2-year follow-up period.18 Cam impingement has also been associated with OA development.19

Pincer-type FAI is characterized by extended bone providing excessive acetabular coverage. Albers et al. found that acetabular version increases with age, while depth and femoral head coverage remain relatively constant.20 This increased acetabular coverage is attributed to posterior acetabulum growth. Hingsammer et al. reported that increased acetabular anteversion and acetabular sector angles result from posterior wall growth.21 Mixed-type FAI exhibits pathomorphologies of both cam-type and pincer-type impingement.

3. Clinical and radiographic diagnostic criteria

Accurate diagnosis is crucial for optimal FAIS management. Various clinical and radiographic factors, including range of motion, tissue laxity, pelvic dynamics, clinical signs and symptoms, and bony anatomy estimation, should be examined before finalizing a diagnosis and selecting a management option.22 While physical examinations can help identify pathology, they are not specific to FAIS. It's important to determine whether the pain originates from an intra-articular or extra-articular source. A diagnostic image-guided intraarticular hip anesthetic injection can confirm intra-articular pain sources.23 Various physical examination tests, such as the Internal Rotation Over Pressure (IROP), FABER, Scour, and FADIR tests, are used to diagnose FAIS. A systematic review reported that IROP and FABER tests were more sensitive in identifying FAIS compared to other tests.24

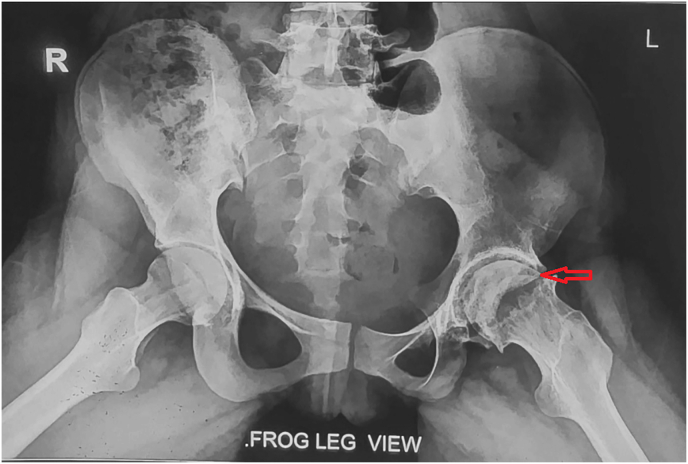

Plain radiographs are commonly used diagnostic tools for FAI.8 They can assess acetabular and femoral anatomy and identify the presence of osteoarthritis. Different radiograph views can better identify specific deformities. For example, a 45° Dunn lateral view is best for identifying cam deformity at the anterolateral region of the femoral head-neck junction.1 Other radiographic views include frog lateral (Fig. 2), anteroposterior plane, cross-table lateral (Fig. 3), and false profile radiographs. Despite advancements in imaging and diagnostic tools, plain radiographs remain widely used in defining acetabular and femoral morphology in FAIS patients.25

Fig. 2.

X-ray Pelvis with both hips showing cam lesion in left hip causing impingement.

Fig. 3.

X-ray showing Pincer lesions bilateral hip causing impingement.

To confirm plain radiograph findings, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MR arthrography (MRA) can be used. MRI identifies structural chondral lesions on the acetabular labrum and femoral head. MRA with joint distention has traditionally been used for evaluating the labrum.22 MRA has higher sensitivity and specificity compared to non-contrast MRI (Fig. 4). Sutter et al. reported that MRA has higher sensitivity (81 % vs 50 %) and specificity (50–100 % vs 50 %) compared to non-contrast MRI for labral tears.26 CT scans are also promising diagnostic modalities to classify proximal femur morphology by computing alpha angles. CT scans provide the best results when recreated into 3D images.27 This process involves importing data into computer software programs to reconstruct 3D images that can be dynamized and analyzed, aiding in hip surgery planning.28

Fig. 4.

Arthroscopic image showing cam bump lesion on femoral head.

4. Non-surgical management of FAIS

While hip arthroscopy has become a primary treatment modality for FAIS, non-surgical management remains a viable alternative for many patients, particularly those who prefer conservative approaches or are not suitable candidates for surgery. Non-surgical treatment focuses on symptom management and functional improvement through physical therapy, activity modification, and pharmacological interventions. Recent studies have explored the efficacy of these conservative approaches in comparison to surgical outcomes, providing valuable insights into their roles in patient care.

Physical therapy (PT) forms the basis of non-surgical management for FAIS. The aim is to strengthen the muscles around the hip, improve range of motion, and reduce impingement-related pain. A targeted program typically includes core strengthening, hip joint mobilization, and functional exercises designed to correct biomechanical imbalances and enhance movement patterns. Recent evidence suggests that patients who adhere to a structured PT regimen may experience notable improvements in pain and function. A study by Pennock et al. reported that approximately 60 % of patients undergoing PT for FAI reported symptom relief, avoiding the need for surgery for at least two years.29 However, these improvements were less sustained when compared to surgical outcomes, especially in terms of long-term pain relief and functional recovery.

Patients with FAIS often find relief through activity modification, which involves reducing high-impact activities like running or jumping that exacerbate impingement. Modifying daily activities, particularly those involving deep hip flexion, can alleviate symptoms. While effective in managing mild cases, this approach may limit athletic individuals or those with high physical demands. The studies have indicated that while activity modification can reduce pain in the short term, it does not address the underlying structural abnormalities and may not be sufficient for long-term management.30

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to manage pain and inflammation associated with FAIS. Corticosteroid injections into the hip joint may offer temporary relief, but studies suggest that their benefits are short-lived, typically lasting only a few months. A recent retrospective cohort study found that corticosteroid injections provided symptom relief in 50 % of patients, though many eventually required surgery due to recurrence of symptoms.31

Surgical management, primarily hip arthroscopy, directly addresses the anatomical abnormalities causing impingement, leading to better long-term outcomes. Studies consistently show that while non-surgical interventions can offer symptom relief, they do not provide the same improvements in hip function or pain relief as surgery. A 2021 meta-analysis concluded that arthroscopy resulted in superior long-term outcomes, with fewer patients reporting recurrence of symptoms compared to those treated non-surgically.32

5. Surgical management: hip arthroscopy for FAI

5.1. Indications for hip arthroscopy

In recent years, hip arthroscopy procedures have significantly increased,33,34 with common utilization in FAIS showing promising patient outcomes.35 Radiographic confirmation of FAIS is the most frequent criterion for deciding on hip arthroscopy.8 However, clinical tests and patient symptoms should also be considered. Not every FAIS case requires surgery; some can be managed non-surgically. Surgery should be reserved for non-arthritic, symptomatic patients with clear radiologic evidence of FAI. Associating physical exam and clinical history with radiological findings is essential in determining the appropriate treatment method.36 In clinical practice, hip arthroscopy is often used in combination with non-surgical modalities.12

5.2. Surgical techniques and procedural steps

The arthroscopic management of FAIS begins with an examination of the region where intra-articular damage has been diagnosed. Sonnenfeld et al. delineated a nine-step protocol for hip arthroscopy in FAIS cases.37 This comprehensive approach encompasses: preoperative room preparation; appropriate positioning of the anesthetized patient; identification and demarcation of osseous landmarks; establishment of anterolateral and mid-anterior portals under image guidance; capsulotomy followed by central compartment assessment; acetabuloplasty; labral repair; peripheral compartment assessment and femoroplasty; and finally, surgical closure and implementation of postoperative rehabilitation protocols.37 This systematic procedure ensures a thorough and effective surgical intervention for FAIS management.

5.2.1. Labral repair or debridement

In cases where the labral tissue is viable, preservation through repair is a primary objective of hip arthroscopy.38 The repair process involves the careful placement of suture anchors to reattach the labrum to a freshly prepared, bleeding bone edge. Precise anchor placement is crucial to avoid chondral injury (Fig. 5). When sufficient tissue is available, a vertical mattress configuration can be employed to perform the repair, either circumferentially around the labrum or through its base. This technique facilitates the preservation of labral anatomy and yields superior biomechanical outcomes.39 In instances where direct repair is not feasible, labral reconstruction or debridement may be necessary. Various graft options for labral restoration are available, including iliotibial band and gracilis tendon autografts.40,41 The choice of graft and technique depends on the specific pathology and surgeon preference, with the ultimate goal of restoring labral function and joint stability.

Fig. 5.

This figure shows the anatomy of the hip joint and illustrates two treatments for labral tears: labral repair and labral debridement. Labral repair involves reattaching the torn labrum to the acetabulum with suture anchors, while labral debridement smooths damaged labral tissue using an arthroscopic tool.

5.2.2. Osteoplasty for cam or pincer impingement

Surgical interventions for FAIS, such as osteoplasty and acetabular rim trimming, aim to correct morphological abnormalities by reshaping the ball-and-socket joint, facilitating improved articulation while addressing associated tissue damage42 (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). These procedures can be performed via open surgery or arthroscopically. Osteoplasty typically involves using a motorized burr to remove excessive bone from the femoral neck, followed by repair of labral and cartilage damage. Philippon et al. conducted a study in which 23 patients underwent osteoplasty for cam impingement and three had rim trimming for pincer impingement. With a mean follow-up of 2.3 years, they reported improvements in both functional outcomes and patient satisfaction.43 In a comparative study, Bardakos et al. investigated the efficacy of osteoplasty in cam-type FAIS against arthroscopic debridement without excision of the impingement lesion (control group). Their findings demonstrated superior patient outcomes in the osteoplasty group compared to the control group.44 These studies underscore the potential benefits of targeted bony resection in addressing the underlying pathomorphology of FAIS.

Fig. 6.

This figure shows surgical treatment for cam and pincer impingement using osteoplasty. In cam impingement, a motorized burr is used to remove the cam lesion on the femoral head, while in pincer impingement, the burr trims the overgrown acetabular rim, resulting in smoother joint articulation post-osteoplasty.

Fig. 7.

Post-operative X-ray after resection of cam lesion left hip improving hip flexion, abduction and rotations.

5.2.3. Adjunctive procedures

Hip arthroscopy allows for the performance of various adjunctive procedures, such as ligamentum teres debridement and synovectomy, to address co-existing pathologies (Fig. 8). Ligamentum teres tears, a significant contributor to groin pain, frequently occur in conjunction with other intra-articular hip lesions and can be treated during arthroscopic intervention.45 The management of these tears typically involves debridement, which is often performed concurrently with the treatment of co-existing synovitis and other lesions, including chondral defects, FAIS, or labral tears.46 Pergaminelis et al. reported short-term benefits following ligamentum teres debridement in their study.45 For cases involving synovitis, synovectomy—the removal of synovium from the joint—can be performed. This procedure may be carried out either through open surgery or arthroscopically.47 The ability to address these co-existing pathologies during hip arthroscopy enhances the comprehensive management of hip joint disorders.

Fig. 8.

The figure illustrates two arthroscopic procedures: Ligamentum Teres Debridement, showing the removal of a tear in the ligament using a shaver for a smoother post-debridement appearance, and Synovectomy, where inflamed synovium is excised from a hip joint affected by synovitis, resulting in a smooth joint capsule post-procedure.

6. Functional outcomes of hip arthroscopy for FAI

6.1. Patient-reported outcome measures

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are widely utilized to evaluate the efficacy of treatment approaches in FAIS. Previous studies have demonstrated that hip arthroscopy yields remarkable short-term and intermediate-term outcomes in terms of functional improvement, return to sport, and symptom resolution.48,49 Several validated tools are employed to record patient-reported outcomes, including the Hip Outcome Score (HOS), the modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS), the Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS), and the patient acceptable symptomatic state (PASS).50 Recently, Robinson et al. validated the forgotten joint score-12 (FJS-12) as an additional outcome questionnaire for FAIS.51

Numerous studies have reported significant improvements in PROMs following hip arthroscopy in FAIS patients. Thorborg et al. observed substantial enhancements in HAGOS and mHHS scores at both 3 months and 1 year post-arthroscopy.52 In a larger cohort study involving 230 FAIS patients, Laurito et al. reported a 73.11 % increase in HHS scores following hip arthroplasty.53 Furthermore, comparative studies have indicated superior outcomes with hip arthroscopy compared to personalized hip therapy.54 However, it is crucial to note that treatment success is also contingent upon patient expectations.55 These findings collectively underscore the effectiveness of surgical intervention, particularly hip arthroscopy, in improving patient-reported outcomes for individuals with FAIS.

6.2. Return to sports and physical activity

Return to sport is a critical outcome measure for arthroscopic treatment of FAIS. The definition of this metric has evolved from a simple binary outcome to a multifaceted assessment encompassing factors such as sport type, intensity level, frequency of athletic activity, and competitive level compared to pre-operative status.56, 57, 58 Consequently, reported rates of return to sport are contingent upon the specific definition employed, necessitating careful interpretation of literature.

Current evidence suggests that the overall rate of return to sport following contemporary surgery for FAIS ranges from 87 to 93 %, with approximately 55–83 % of athletes returning to their pre-operative level of competition.59,60 A systematic review by Reiman et al. reported that 74 % of athletes with FAIS resumed their previous competitive level post-surgery.61 Corroborating these findings, a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis encompassing 1981 hips among 1911 patients demonstrated an 87.7 % return to sports rate following hip arthroscopy (P < 0.001).62

Jack et al. observed an 86.4 % return to sports rate among athletes with FAIS who underwent hip arthroscopy, with an average return time of 7.1 ± 4.1 months.63 Notably, these athletes maintained their sporting activities for an average of 3.5 ± 2.4 years post-surgery. In a study focusing on National Football League (NFL) players, 84.1 % returned to their sport at a mean duration of 6.7 ± 3.8 months post-surgery.64

It is important to note that return to sport rates are generally lower for individuals involved in contact sports compared to non-contact sports.56 This variability underscores the importance of considering sport-specific factors when counseling patients and interpreting outcomes in FAIS management.

6.3. Long-term outcomes and durability of the procedure

While long-term outcomes of hip arthroscopy for FAIS have not been extensively investigated, emerging evidence suggests its enduring efficacy. A 10-year follow-up study reported significant improvements in all patient-reported outcomes from baseline following arthroscopic procedures in FAIS patients, with a remarkable 100 % survivorship.65 Another study, with a mean follow-up of 32.8 months, demonstrated significant enhancements in patient-reported outcomes post-hip arthroscopy, with notably greater improvements observed in cam-type FAIS compared to mixed or pincer types, due to less acetabular involvement and joint stress.66 Similarly, a five-year follow-up reported sustained improvements in patient-reported measures like the modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS), with most patients returning to pre-symptom activity levels.67

However, it's important to note that some patients may eventually require total hip arthroplasty. Menge et al. reported that 34 % of FAIS patients underwent total hip arthroplasty within 10 years of their initial arthroscopy, although patient-reported outcomes were still significantly improved following the arthroscopic procedure.68 These findings underscore the complex long-term trajectory of FAIS management.

Corroborating the positive trend in outcomes, another study with a 5-year follow-up period also reported significant improvements in patient-reported outcomes after arthroscopy.69 These studies collectively suggest that while hip arthroscopy can provide substantial long-term benefits for many FAIS patients, a subset may require further interventions. This underscores the importance of comprehensive patient counseling and long-term follow-up in the management of FAIS.

6.4. Factors influencing functional outcomes

Functional outcomes following hip surgery in FAIS patients are influenced by a multitude of factors, many of which are patient-specific. These factors include body mass index, sex, age, and lifestyle. Comorbidities play a crucial role, with obesity being a key factor.70 It has been found that patients with BMI ≥30 had inferior outcomes and higher revision rates.71 Likewise, diabetes is a comorbidity affecting results, as Perets et al. (2021) reported lower improvement in patient-reported outcomes for diabetic patients.72

Sex- and age-related disparities significantly influence the outcomes of hip arthroscopy for FAIS, underscoring the need for individualized treatment. Younger individuals, especially those under 40, with high level of physical activity typically demonstrate faster healing rates due to better overall outcomes due to higher healing potential and fewer pre-existing joint degenerations. In a study encompassing 632 hips (632 patients), Ouyang et al. identified younger age, increased alpha angle, and capsular repair as predictors of superior outcomes.73 However, Yang et al. noted that carefully selected older patients can still benefit from the procedure.74

Moreover, the severity of FAIS varies among patients, potentially affecting post-surgical functional outcomes. Gender differences in outcomes have also been observed. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis, incorporating 74 studies, revealed that females exhibited greater improvements in patient-reported outcomes compared to males, although both sexes achieved clinically significant improvements from baseline.75 However, due to differences in hip anatomy and joint laxity, the female patients may suffer higher complication rates.75

Prior hip issues also impact arthroscopy success. It has been demonstrated that patients with pre-existing osteoarthritis had poorer outcomes and faster progression to total hip arthroplasty.76 Additionally, it has been found that previous hip surgeries negatively affected arthroscopy results.77

7. Complications and adverse events

While arthroscopy for FAIS is generally considered a safe and successful procedure with fewer complications compared to open surgery, it is not without risks.78 The unique anatomy of the hip joint contributes to these potential complications. The hip, being a deep-seated joint, is dynamically stabilized by the surrounding muscular envelope and statically by the deep acetabulum.79 This anatomical complexity, coupled with the intricacy of the surgical procedure, inherently carries a risk of various complications.

Initially, complication rates were perceived to be very low. However, with increased experience and longer follow-up periods, long-term complications of hip arthroscopy in FAIS have been increasingly recognized and reported.80 Current estimates place the complication rates of hip arthroscopy between 0.5 % and 6.4 %.81

Interestingly, a systematic review by Owen et al. suggested that females may experience a higher rate of complications following hip arthroscopy compared to males, although this finding did not reach statistical significance.75 This observation highlights the potential influence of patient-specific factors on surgical outcomes and complication rates.

7.1. Intraoperative complications

Several critical neurovascular structures encircle the hip joint, including the gluteal vessels and sciatic nerve posteriorly, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve anterolaterally, and the femoral neurovascular bundle anteriorly. While direct injury to the neurovascular bundle is infrequent, it remains a serious complication that necessitates careful consideration.82 During hip surgery, nerve injuries, although rarely a result of direct penetration, are more commonly attributed to traction forces. Nossa et al. identified transient neurological injury as the most prevalent complication following hip arthroscopy in patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS), often linked to prolonged traction durations.83

Intraoperative damage to the articular cartilage and acetabular labrum is a frequent occurrence during hip arthroscopy. Specifically, inadvertent injury to the superior labrum may arise when establishing the anterolateral portal.84 This complication occurs if the labrum detaches from the acetabulum, causing it to occupy more joint space. Surgeons must be vigilant during the procedure to ensure the labrum is not compromised by the cannula.82

Soft tissues are secured to bones using suture anchors. To restore labral function effectively, the fixation device must be positioned on the acetabular rim adjacent to the articular cartilage, avoiding any damage to the cartilage.85 Improper placement of suture anchors—either too far from the articular cartilage, which may impair labral function, or too close, risking cartilage injury—can have detrimental consequences. To mitigate this risk, surgeons should note that the distal anterolateral accessory (DALA) portal, when using a straight drill guide, allows for anchor placement farther from the articular surface compared to the mid-anterior and anterolateral portals.86

7.2. Postoperative complications

The incidence of heterotopic ossification following hip surgery has increased with the advancement of arthroscopic techniques and the use of larger capsulotomies. This condition is thought to arise from surgical trauma to bone debris and the gluteal muscles, which may stimulate new bone formation. Although heterotopic ossification after hip surgery has not been associated with significant functional impairments, preventive measures are crucial. Proper lavage of the hip joint at the conclusion of the procedure is recommended to remove any bone debris and minimize the risk of heterotopic ossification.87 Additionally, if ossification is detected on the initial postoperative radiograph, close follow-up for up to twelve months is advised.82

Hip arthroscopy typically lasts between 45 and 150 min and involves bone reshaping, soft tissue dissection, and the use of foreign materials such as sutures and implants. These factors contribute to the potential risk of postoperative infection. Despite this risk, the use of chemoprophylaxis in hip surgery has not been extensively studied. Current practice involves the administration of a single intravenous dose of antibiotics, with a repeat dose if the surgery exceeds 120 min.82

7.3. Revision surgery and its outcomes

While many patients successfully recover and return to normal physical activity following hip arthroscopy, some individuals may not experience sufficient improvement and may require revision surgery. When revision surgery becomes necessary, the decision-making process can be complex. A primary challenge is determining whether an underlying condition exists that cannot be addressed surgically. Additional difficulties arise when certain pathologies develop symptoms after the initial procedure, necessitating a second surgery. Moreover, iatrogenic damage during the primary surgery can complicate the secondary procedure and increase the risk of complications.88 An essential consideration when planning revision surgery is the potential outcomes. Even when revision surgery is appropriately indicated, it may still result in suboptimal outcomes. Both the surgeon and the patient must carefully weigh these possible outcomes and set realistic expectations. Therefore, understanding the potential results of revision surgery is crucial in the decision-making process.89

8. Rehabilitation and recovery

8.1. Early postoperative management

Post-operative management protocols for hip arthroscopy are continuously evolving alongside advancements in arthroscopic techniques.90 These protocols are typically informed by the clinician's experience, the characteristics of tissue healing, and the patient's tolerance. A significant post-surgical challenge for patients is managing the progression of weight-bearing activities. Specific guidelines for range of motion (ROM) have been established for patients undergoing surgery to address capsular laxity. These protocols generally share common principles regarding weight-bearing, ROM, initial physical activity, and strength recommendations.91 Current guidelines suggest using an upright stationary bike to facilitate a gentle range of motion. Depending on patient tolerance and the surgical indication, hip and pelvic muscle stretching is also advised. Most protocols recommend a minimum of 12 weeks before resuming athletic or other physical activities, though this timeline may vary based on the specific procedure and individual patient factors.90

8.2. Phases of rehabilitation

The rehabilitation process following hip surgery consists of several phases, each with specific goals and strategies. The initial phase, often referred to as the protective phase, focuses on enhancing the range of motion, reducing lower extremity edema, and re-establishing normal neuromuscular firing patterns in the hip and pelvis. Soft tissue mobilization and manual techniques play a critical role in this phase, aiding in the reduction of quadriceps edema and, during the subsequent two weeks, targeting the adductor group for mobilization.90,92

In the second phase, the primary objective is for the patient to independently perform daily activities with minimal or no pain and gradually progress to walking longer distances. This phase requires ongoing manual intervention to address soft tissue restrictions at the end ranges of motion, while also continuing to improve neuromuscular timing, strength, and control.90,92

The third phase of rehabilitation emphasizes building endurance and strength, enabling the patient to move independently while maintaining control during various activities. The focus shifts to ensuring continuous movement of the extremities over a stable core. Manual muscle testing is essential to assess muscle endurance, and close observation during exercise is necessary to detect compensatory movements and signs of fatigue. If proper form cannot be maintained, the exercise should be halted, prioritizing quality over quantity.92

Once the patient can perform various physical activities without pain, the final phase aims to prevent injury recurrence and acute inflammatory responses during recovery. This requires a progressive, phased program tailored to the patient's needs. Empirical evaluations and evidence-based tests are available to guide the safe return to sports and other high-demand activities.80

8.3. Return to sports and physical activity protocols

Although many athletes successfully return to sports, their performance levels post-return often go unreported.61 The current literature emphasizes that athletes should follow the four rehabilitation phases outlined above to facilitate a safe return to sports. Additionally, rehabilitation guidelines incorporate restrictions on range of motion (ROM) and weight-bearing.93 Studies by Hallberg et al.94 and Kierkegaard et al.95 indicate that athletes returning to sports after hip arthroplasty often lack adequate hip strength. As a result, post-operative strength training of the hip muscles should be an essential component of their rehabilitation protocols.

9. Emerging trends and future directions

Emerging trends in the management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS) are centered around the development of new surgical techniques and technologies, advancements in preoperative planning, and innovative rehabilitation approaches. Surgical options for FAIS now include arthroscopic approaches, open surgery, and a combination of arthroscopic and mini-open methods.96 While specific indications for these surgical techniques are still being refined, ongoing improvements in arthroscopic methods and technological advancements are evident.97 One promising area of research involves the estimation of gait kinematics, highlighting the need for standardized protocols in this process.98,99 Additionally, studies on biochemical markers of inflammation and cartilage breakdown are gaining traction.100,101 The adoption of computer-assisted technologies in hip surgery, particularly in arthroscopy, is also being encouraged. This technology assists in both preoperative diagnosis and assessment, as well as in the surgical procedure itself, potentially leading to improved outcomes and a reduction in complications.102 Notably, recent research has shown that the pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block effectively reduces pain following arthroscopic procedures for FAIS, particularly at 18 and 24 h postoperatively.103

Preoperative planning and patient selection have also seen significant advancements. Emerging techniques in computer-assisted preoperative planning, such as disease stratification based on 3D anatomical features, are enhancing the precision of surgical interventions. This method relies on detailed modeling of each patient's anatomy, enabling more accurate disease categorization and improving the preoperative planning process. These models provide a more precise identification of anatomical variations compared to traditional measures like the alpha angle, offering a deeper understanding of etiology and allowing for better characterization of the disease.104

In the realm of rehabilitation, novel approaches are being developed to improve outcomes following hip surgery. One such approach is neuromuscular training, where patients engage in exercises designed to enhance stability and movement post-surgery.105 Blood flow restriction therapy is another emerging technique aimed at restoring physical performance after hip arthroscopy. This method involves using a tourniquet to occlude venous outflow and reduce arterial flow, combined with resistance exercises, to effectively restore muscular performance post-surgery.106 Additionally, virtual reality is being utilized as a rehabilitation tool, providing real-time feedback during exercises to help restore muscular strength, physical activity, and hip mobility in patients recovering from FAIS.107

10. Conclusion

FAIS is commonly managed through hip arthroscopy, with the choice of surgical method depending on the specific type of FAI. The primary goals of hip arthroscopy are pain relief, restoration of physical function, and long-term durability of the procedure. Substantial evidence indicates that hip arthroscopy leads to improved outcomes in patients with FAIS. However, several factors can influence these outcomes, and both pre- and post-operative complications can arise, which can often be mitigated with proper care.

The studies included in this narrative review primarily relied on retrospective cohorts, case series, and systematic reviews, which inherently introduce selection and reporting biases. Many studies lacked randomized controlled trials (RCTs), limiting the ability to establish causal relationships between hip arthroscopy and long-term functional outcomes in FAIS. Additionally, patient-reported outcome measures were commonly used across studies, but their subjective nature introduces variability based on patient expectations and perception of improvement. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of patient populations, as factors such as age, sex, activity level, and FAIS subtype were not consistently controlled across studies, which may skew the generalizability of findings. Lastly, most studies had limited follow-up durations, and while short- and mid-term outcomes were assessed, long-term durability of arthroscopy in FAIS patients remains less well-documented. Therefore, future research should focus on prospective, multicenter RCTs with standardized protocols and extended follow-up periods to strengthen the evidence base.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cara Mohammed: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, preparation, Literature search, Data extraction. Ronny Kong: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, preparation, Literature search, Data extraction. Venkataramana Kuruba: Literature search, Data extraction. Noman Ullah Wazir: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Vikramaditya Rai: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, preparation, Literature search. Shahzad Waqas Munazzam: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, preparation, Literature search.

Funding

There is no funding source.

Consent for publication: All authors have consented for the publication of the article.

Informed consent: Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Cara Mohammed, Email: caramohammed@gmail.com.

Ronny Kong, Email: ronnygkong@gmail.com.

Venkataramana Kuruba, Email: venkat.ortho@aiimsmangalagiri.edu.in.

Vikramaditya Rai, Email: raizobiotec@gmail.com.

Shahzad Waqas Munazzam, Email: swmwar@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Pun S., Kumar D., Lane N.E. Femoroacetabular impingement. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):17–27. doi: 10.1002/art.38887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jauregui J.J., Salmons H.I., Meredith S.J., Oster B., Gopinath R., Adib F. Prevalence of femoro-acetabular impingement in non-arthritic patients with hip pain: a meta-analysis. Int Orthop. 2020;44(12):2559–2566. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04857-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hale R.F., Melugin H.P., Zhou J., et al. Incidence of femoroacetabular impingement and surgical management trends over time. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(1):35–41. doi: 10.1177/0363546520970914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhry H., Ayeni O.R. The etiology of femoroacetabular impingement: what we know and what we don't. Sport Health. 2014;6(2):157–161. doi: 10.1177/1941738114521576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganz R., Parvizi J., Beck M., Leunig M., Nötzli H., Siebenrock K.A. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:112–120. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sankar W.N., Nevitt M., Parvizi J., Felson D.T., Leunig M. Femoroacetabular impingement: defining the condition and its role in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2013;21:S7–S15. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-07-S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin D.R., Dickenson E.J., O'Donnell J., et al. The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(19) doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096743. 1169-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fortier L.M., Popovsky D., Durci M.M., Norwood H., Sherman W.F., Kaye A.D. An updated review of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Orthop Rev. 2022;14(3) doi: 10.52965/001c.37513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egger A.C., Frangiamore S., Rosneck J. Femoroacetabular impingement: a review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2016;24(4):e53–e58. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasculli R.M., Callahan E.A., Wu J., Edralin N., Berrigan W.A. Non-operative management and outcomes of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(11):501–513. doi: 10.1007/s12178-023-09863-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khanduja V., Ha Y.-C., Koo K.-H. Controversial issues in arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Surg. 2021;13(4):437. doi: 10.4055/cios21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buzin S., Shankar D., Vasavada K., Youm T. Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement-associated labral tears: current status and future prospects. Orthop Res Rev. 2022;14:121–132. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S253762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nwachukwu B.U., Rebolledo B.J., McCormick F., Rosas S., Harris J.D., Kelly B.T. Arthroscopic versus open treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of medium-to long-term outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(4) doi: 10.1177/0363546515587719. 1062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw C. Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a cause of hip pain in adolescents and young adults. Mo Med. 2017;114(4):299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matar H.E., Rajpura A., Board T.N. Femoroacetabular impingement in young adults: assessment and management. Br J Hosp Med. 2019;80(10):584–588. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2019.80.10.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorentino G., Fontanarosa A., Cepparulo R., et al. Treatment of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. Joints. 2015;3(2):67. doi: 10.11138/jts/2015.3.2.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siebenrock K.A., Wahab K.H., Werlen S., Kalhor M., Leunig M., Ganz R. Abnormal extension of the femoral head epiphysis as a cause of cam impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:54–60. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agricola R., Heijboer M.P., Ginai A.Z., et al. A cam deformity is gradually acquired during skeletal maturation in adolescent and young male soccer players: a prospective study with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):798–806. doi: 10.1177/0363546514524364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agricola R., Waarsing J.H., Arden N.K., et al. Cam impingement of the hip: a risk factor for hip osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(10):630–634. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albers C.E., Schwarz A., Hanke M.S., Kienle K.P., Werlen S., Siebenrock K.A. Acetabular version increases after closure of the triradiate cartilage complex. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(4):983–994. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hingsammer A.M., Bixby S., Zurakowski D., Yen Y.M., Kim Y.J. How do acetabular version and femoral head coverage change with skeletal maturity? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(4):1224–1233. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4014-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mascarenhas V.V., Caetano A., Dantas P., Rego P. Advances in FAI imaging: a focused review. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2020;13:622–640. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09663-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nepple J.J., Prather H., Trousdale R.T., et al. Clinical diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement. JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2013;21 doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-07-S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacheco-Carrillo A., Medina-Porqueres I. Physical examination tests for the diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement. A systematic review. Phys Ther Sport. 2016;21:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atalar E., Üreten K., Kanatlı U., et al. The diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement can be made on pelvis radiographs using deep learning methods. Joint diseases and related surgery. 2023;34(2):298. doi: 10.52312/jdrs.2023.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutter R., Zubler V., Hoffmann A., et al. Hip MRI: how useful is intraarticular contrast material for evaluating surgically proven lesions of the labrum and articular cartilage? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(1):160–169. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han J., Won S.H., Kim J.T., Hahn M.H., Won Y.Y. Prevalence of cam deformity with associated femoroacetabular impingement syndrome in hip joint computed tomography of asymptomatic adults. Hip Pelvis. 2018;30(1):5–11. doi: 10.5371/hp.2018.30.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhn A.W., Ross J.R., Bedi A. Three-dimensional imaging and computer navigation in planning for hip preservation surgery. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2015;23(4):e31–e38. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pennock A.T., Bomar J.D., Parvanta K., Upasani V.V. Non-operative management of femoroacetabular impingement: a prospective study. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;6(7_suppl 4) doi: 10.1177/2325967118S00069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terrell S.L., Olson G.E., Lynch J. Therapeutic exercise approaches to nonoperative and postoperative management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. J Athl Train. 2021 Jan 1;56(1):31–45. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0488.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van den Hoek Catharina W., Wolterbeek Nienke, Kaas Laurens. Patient characteristics cannot predict the long-term effect of an intra-articular bupivacaine and corticosteroid injection in patients with femoroacetabular impingement: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma. 2023;41 doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2023.102174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mok T.N., He Q.Y., Teng Q., et al. Arthroscopic hip surgery versus conservative therapy on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a meta-analysis of RCTs. Orthop Surg. 2021 Aug;13(6):1755–1764. doi: 10.1111/os.13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dippmann C., Kraemer O., Lund B., et al. Multicentre study on capsular closure versus non-capsular closure during hip arthroscopy in Danish patients with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rath E., Tsvieli O., Levy O. Hip arthroscopy: an emerging technique and indications. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14(3):170–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacFarlane R.J., Konan S., El-Huseinny M., Haddad F.S. A review of outcomes of the surgical management of femoroacetabular impingement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96(5):331–338. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184900723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasser R., Domb B. Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement. EFORT Open Reviews. 2018;3(4):121–129. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonnenfeld J.J., Trofa D.P., Mehta M.P., Steinl G., Lynch T.S. Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2018;8(3):e23. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.18.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Domb B.G., Hartigan D.E., Perets I. Decision making for labral treatment in the hip: repair versus débridement versus reconstruction. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2017;25(3):e53–e62. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hapa O., Barber F.A., Başçı O., et al. Biomechanical performance of hip labral repair techniques. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2016;32(6):1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Philippon M.J., Bolia I., Locks R., Utsunomiya H. Treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: labrum, cartilage, osseous deformity, and capsule. Am J Orthoped. 2017;46(1):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Locks R., Chahla J., Frank J.M., Anavian J., Godin J.A., Philippon M.J. Arthroscopic hip labral augmentation technique with iliotibial band graft. Arthroscopy Techniques. 2017;6(2):e351–e356. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.A multi-centre randomized controlled trial comparing arthroscopic osteochondroplasty and lavage with arthroscopic lavage alone on patient important outcomes and quality of life in the treatment of young adult (18-50) femoroacetabular impingement. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2015;16:64. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0500-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Philippon M.J., Briggs K.K., Yen Y.M., Kuppersmith D.A. Outcomes following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement with associated chondrolabral dysfunction: minimum two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(1):16–23. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.21329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bardakos N.V., Vasconcelos J.C., Villar R.N. Early outcome of hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement: the role of femoral osteoplasty in symptomatic improvement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(12):1570–1575. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B12.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pergaminelis N., Renouf J., Fary C., Tirosh O., Tran P. Outcomes of arthroscopic debridement of isolated Ligamentum Teres tears using the iHOT-33. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2017;18(1):554. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1905-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chahla J., Soares E., Devitt B., et al. Ligamentum teres tears and femoroacetabular impingement: prevalence and preoperative findings. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2016;32 doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian K., Gao G., Dong H., Zhang W., Wang J., Xu Y. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the hip joint: the regional surgical technique. Arthroscopy Techniques. 2022;11(7):e1181–e1187. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2022.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sawyer G.A., Briggs K.K., Dornan G.J., Ommen N.D., Philippon M.J. Clinical outcomes after arthroscopic hip labral repair using looped versus pierced suture techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1683–1688. doi: 10.1177/0363546515581469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zanchi N., Safran M.R., Herickhoff P. Return to play after femoroacetabular impingement. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(12):587–597. doi: 10.1007/s12178-023-09871-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chahal J., Van Thiel G.S., Mather R.C., 3rd, et al. The patient acceptable symptomatic state for the modified Harris hip score and hip outcome score among patients undergoing surgical treatment for femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(8):1844–1849. doi: 10.1177/0363546515587739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson P.G., Rankin C.S., Murray I.R., Maempel J.F., Gaston P., Hamilton D.F. The forgotten joint score-12 is a valid and responsive outcome tool for measuring success following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(5):1378–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06138-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thorborg K., Kraemer O., Madsen A.D., Hölmich P. Patient-reported outcomes within the first year after hip arthroscopy and rehabilitation for femoroacetabular impingement and/or labral injury: the difference between getting better and getting back to normal. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(11):2607–2614. doi: 10.1177/0363546518786971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laurito G.M., Aranha F.L., Piedade S.R. Functional outcomes of arthroscopic treatment in 230 femoroacetabular impingement cases. Acta Ortopédica Bras. 2021;29(2):67–71. doi: 10.1590/1413-785220212902236846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griffin D.R., Dickenson E.J., Wall P.D.H., et al. Hip arthroscopy versus best conservative care for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (UK FASHIoN): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10136):2225–2235. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31202-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Realpe A.X., Foster N.E., Dickenson E.J., Jepson M., Griffin D.R., Donovan J.L. Patient experiences of receiving arthroscopic surgery or personalised hip therapy for femoroacetabular impingement in the context of the UK fashion study: a qualitative study. Trials. 2021;22(1) doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05151-6. 211. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishøi L., Thorborg K., Kraemer O., Hölmich P. Return to sport and performance after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in 18-to 30-year-old athletes: a cross-sectional cohort study of 189 athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(11):2578–2587. doi: 10.1177/0363546518789070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wörner T., Thorborg K., Stålman A., Webster K.E., Olsson H.M., Eek F. High or low return to sport rates following hip arthroscopy is a matter of definition? Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(22):1475–1476. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ardern C.L., Glasgow P., Schneiders A., et al. Consensus statement on return to sport from the first world congress in sports physical therapy, bern. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(14):853–864. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096278. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parvaresh K.C., Wichman D., Rasio J., Nho S.J. Return to sport after femoroacetabular impingement surgery and sport-specific considerations: a comprehensive review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13(3):213–219. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09617-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ko S.J., Terry M.A., Tjong V.K. Return to sport after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a comprehensive review of qualitative considerations. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13(4):435–441. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09634-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiman M.P., Peters S., Sylvain J., Hagymasi S., Mather R.C., Goode A.P. Femoroacetabular impingement surgery allows 74% of athletes to return to the same competitive level of sports participation but their level of performance remains unreported: a systematic review with meta analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(15):972–981. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Minkara A.A., Westermann R.W., Rosneck J., Lynch T.S. Systematic review and meta analysis of outcomes after hip arthroscopy in femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(2):488–500. doi: 10.1177/0363546517749475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jack R.A., 2nd, Sochacki K.R., Hirase T., Vickery J.W., Harris J.D. Performance and return to sport after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in professional athletes differs between sports. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(5):1422–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.10.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sochacki K.R., Jack R.A., Hirase T., et al. Performance and return to sport after femoroacetabular impingement surgery in national Football League players. Orthopedics. 2019;42(5):e423–e429. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20190403-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Domb B.G., Prabhavalkar O.N., Maldonado D.R., Perez-Padilla P.A. Long-term outcomes of arthroscopic labral treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents: a nested propensity-matched analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2024;106(12):1062–1068. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.23.00648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Said H.G., Masoud M.A., Morsi M.M.A., El-Assal M.A. Outcomes of hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement: the effect of morphological type and chondrolabral damage. Sicot j. 2019;5:16. doi: 10.1051/sicotj/2019012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Winge S., Winge S., Kraemer O., Dippmann C., Hölmich P. Arthroscopic treatment for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS) in adolescents-5-year follow-up. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2021 Jul 3;8(3):249–254. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnab051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Menge T.J., Briggs K.K., Dornan G.J., McNamara S.C., Philippon M.J. Survivorship and outcomes 10 Years following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement: labral debridement compared with labral repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(12):997–1004. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winge S., Winge S., Kraemer O., Dippmann C., Hölmich P. Arthroscopic treatment for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS) in adolescents-5-year follow-up. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2021;8(3):249–254. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnab051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin L.J., Akpinar B., Bloom D.A., Youm T. Age and outcomes in hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement: a comparison across 3 age groups. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49(1):82–89. doi: 10.1177/0363546520974370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mygind-Klavsen B., Nielsen T.G., Lund B., et al. Clinical outcomes after revision hip arthroscopy in patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS) are inferior compared to primary procedures. Results from the Danish Hip Arthroscopy Registry (DHAR) Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29:1340–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06135-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Perets I., Chaharbakhshi E.O., Barkay G., Mu B.H., Lall A.C., Domb B.G. Diabetes mellitus is not a negative prognostic factor for patients undergoing hip arthroscopy. Orthopedics. 2021;44(4):241–248. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20210621-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ouyang V.W., Saks B.R., Maldonado D.R., et al. Younger age, capsular repair, and larger preoperative alpha angles are associated with earlier achievement of clinically meaningful improvement after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Arthroscopy. 2022;38(7):2195–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang F, Shi Y, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Huang H, Ju X, Wang J. Arthroscopy Confers Excellent Clinical Outcomes in Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome (FAIS) Patients Aged 50 Years. Orthop. Surg. 2023;15(4):947–952. doi: 10.1111/os.13666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Owen M.M., Gohal C., Angileri H.S., et al. Sex-based differences in prevalence, outcomes, and complications of hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(8) doi: 10.1177/23259671231188332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vesey RM, Bacon CJ, Brick MJ. Pre-existing osteoarthritis remains a key feature of arthroscopy patients who convert to total hip arthroplasty. Journal of ISAKOS, Volume 6, Issue 4, 199 - 203. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Spencer A.D., Hagen M.S. Predicting outcomes in hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2024 Mar;17(3):59–67. doi: 10.1007/s12178-023-09880-w. Epub 2024 Jan 6. PMID: 38182802; PMCID: PMC10847074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maupin J.J., Steinmetz G., Thakral R. Management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: current insights. Orthop Res Rev. 2019;11:99–108. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S138454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mei-Dan O., Young D.A. A novel technique for capsular repair and labrum refixation in hip arthroscopy using the SpeedStitch. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1(1):e107–e112. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crim J. Imaging evaluation of the hip after arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement. Skeletal Radiol. 2017;46(10):1315–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2665-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Papavasiliou A.V., Bardakos N.V. Complications of arthroscopic surgery of the hip. Bone Joint Res. 2012;1(7):131–144. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.17.2000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakano N., Khanduja V. Complications in hip arthroscopy. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2016;6(3):402–409. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2016.6.3.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nossa J.M., Aguilera B., Márquez W., et al. Factors associated with hip arthroscopy complications in the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Current Orthopaedic Practice. 2014;25(4) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mayer S.W., Fauser T.R., Marx R.G., et al. Reliability of the classification of cartilage and labral injuries during hip arthroscopy. Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2021;7(3):448–457. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnaa064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ridley T.J., Ruzbarsky J.J., Seiter M., Peebles L.A., Philippon M.J. Arthroscopic labral repair of the hip using a self-grasping suture-passing device: maintaining the chondrolabral junction. Arthrosc Tech. 2020;9(9):e1263–e1267. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stanton M., Banffy M. Safe angle of anchor insertion for labral repair during hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2016;32(9):1793–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Matsuda D.K., Calipusan C.P. Adolescent femoroacetabular impingement from malunion of the anteroinferior iliac spine apophysis treated with arthroscopic spinoplasty. Orthopedics. 2012;35(3):e460–e463. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120222-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mansor Y., Perets I., Close M.R., Mu B.H., Domb B.G. In search of the spherical femoroplasty: cam overresection leads to inferior functional scores before and after revision hip arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(9):2061–2071. doi: 10.1177/0363546518779064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shapira J., Kyin C., Go C., et al. Indications and outcomes of secondary hip procedures after failed hip arthroscopy: a systematic review. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2020;36(7):1992–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Edelstein J., Ranawat A., Enseki K.R., Yun R.J., Draovitch P. Post-operative guidelines following hip arthroscopy. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2012;5:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s12178-011-9107-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cheatham S.W., Enseki K.R., Kolber M.J. Postoperative rehabilitation after hip arthroscopy: a search for the evidence. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24(4):413–418. doi: 10.1123/JSR.2014-0208a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hanish S., Muhammed M., Kelly S., DeFroda S. Postoperative rehabilitation for arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a contemporary review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(9):381–391. doi: 10.1007/s12178-023-09850-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Holling M.J., Miller S.T., Geeslin A.G. Rehabilitation and return to sport after arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a review of the recent literature and discussion of advanced rehabilitation techniques for athletes. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2022;4(1):e125–e132. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hallberg S., Sansone M., Augustsson J. Full recovery of hip muscle strength is not achieved at return to sports in patients with femoroacetabular impingement surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(4):1276–1282. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5337-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kierkegaard S., Langeskov-Christensen M., Lund B., et al. Pain, activities of daily living and sport function at different time points after hip arthroscopy in patients with femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2016;51 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khan M., Bedi A., Fu F., Karlsson J., Ayeni O.R., Bhandari M. New perspectives on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(5):303–310. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Clohisy J.C., Kim Y.-J., Lurie J., et al. Clinical trials in orthopaedics and the future direction of clinical investigations for femoroacetabular impingement. JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2013;21 doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-07-S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ayeni O.R., Sansone M., de Sa D., et al. Femoro acetabular impingement clinical research: is a composite outcome the answer? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:295–301. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alradwan H., Khan M., Grassby M.H.-S., Bedi A., Philippon M.J., Ayeni O.R. Gait and lower extremity kinematic analysis as an outcome measure after femoroacetabular impingement surgery. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 2015;31(2):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bedi A., Lynch E.B., Sibilsky Enselman E.R., et al. Elevation in circulating biomarkers of cartilage damage and inflammation in athletes with femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11) doi: 10.1177/0363546513499308. 2585-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nepple J.J., Thomason K.M., An T.W., Harris-Hayes M., Clohisy J.C. What is the utility of biomarkers for assessing the pathophysiology of hip osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1683–1701. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nakano N., Audenaert E., Ranawat A., Khanduja V. Current concepts in computer‐assisted hip arthroscopy. Int J Med Robot Comput Assist Surg. 2018;14(6) doi: 10.1002/rcs.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eppel B., Schneider M.M., Gebhardt S., et al. Pericapsular nerve group block leads to small but consistent reductions in pain between 18 and 24 hours postoperatively in hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement surgery: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial. Arthroscopy. 2024;40(2):373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2023.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang J., Pettit M., Kumar K.H.S., Khanduja V. Recent advances and future trends in hip arthroscopy. Journal of Arthroscopic Surgery and Sports Medicine. 2020;1(1):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Judd D.L., Winters J.D., Stevens-Lapsley J.E., Christiansen C.L. Effects of neuromuscular reeducation on hip mechanics and functional performance in patients after total hip arthroplasty: a case series. Clin BioMech. 2016;32:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cognetti D.J., Sheean A.J., Owens J.G. Blood flow restriction therapy and its use for rehabilitation and return to sport: physiology, application, and guidelines for implementation. Arthroscopy, sports medicine, and rehabilitation. 2022;4(1):e71–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fascio E., Vitale J.A., Sirtori P., Peretti G., Banfi G., Mangiavini L. Early virtual-reality based home rehabilitation after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):1766. doi: 10.3390/jcm11071766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]