Abstract

The spin Hall effect couples charge and spin transport1–3, enabling electrical control of magnetization4,5. A quintessential example of SOI-induced transport is the anomalous Hall effect (AHE)6, first observed in 1880, in which an electric current perpendicular to the magnetization in a magnetic film generates charge accumulation on the surfaces. Here we report the observation of a counterpart of the AHE that we term the anomalous spin-orbit torque (ASOT), wherein an electric current parallel to the magnetization generates opposite spin-orbit torques on the surfaces of the magnetic film. We interpret the ASOT as due to a spin-Hall-like current generated with an efficiency of 0.053 ± 0.003 in Ni80Fe20, comparable to the spin Hall angle of Pt7. Similar effects are also observed in other common ferromagnetic metals, including Co, Ni, and Fe. First principles calculations corroborate the order of magnitude of the measured values. This work suggests that a strong spin current with spin polarization transverse to magnetization can be generated within a ferromagnet, despite spin dephasing8. The large magnitude of the ASOT should also be taken into consideration when investigating spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic/nonmagnetic bilayers.

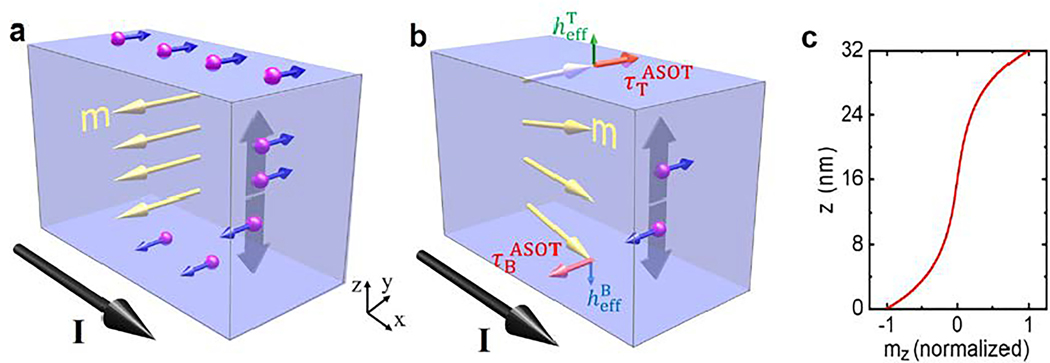

The spin Hall effect can convert a charge current into a perpendicular flow of spin angular momentum (spin current) 9. One of its manifestations in a magnetic conductor is the AHE10, illustrated in Fig. 1a. Due to the imbalance of electrons with spins parallel and antiparallel to the magnetization, the flow of spin current results in charge accumulation on the top and bottom surfaces. The spin current in this configuration is polarized parallel with the magnetization11–13. Applying similar considerations to the configuration illustrated in Fig. 1b, in which the electric current is parallel to the magnetization, a spin current can flow between the top and bottom surfaces of the magnetic conductor, except with electron spins transverse to the magnetization. In single-layer ferromagnets with bulk inversion symmetry, the transversely polarized spin current does not give rise to a bulk spin torque (those with broken bulk inversion symmetry have been shown to exhibit a non-zero bulk spin-orbit torque14,15). Instead, we predict that it will result in net anomalous spin-orbit torque (ASOT) on the top and bottom surfaces, where inversion symmetry is broken (see Supplementary Information section S1). It should be noted that the term “anomalous” here does not mean the ASOT has different behavior from conventional spin-orbit torque5 – the two have the same symmetry – but rather is used to illustrate its connection with the AHE. Both ASOT and AHE are spin-orbit interaction-induced phenomena that can only be observed in single-layer magnetic conductors, under different current and magnetization configurations, as illustrated in Figs. 1a and 1b.

Figure 1. Illustrations of the anomalous Hall effect and anomalous spin-orbit torque.

a, In the anomalous Hall effect (AHE) a charge current I (black arrow) perpendicular to the magnetization m (yellow arrows) generates a flow of spin current (grey arrows) in the -direction. Here blue arrows on purple spheres represent spin directions of electrons. Due to the imbalance of majority and minority electrons, the flow of spin current results in spin and charge accumulation on the top and bottom surfaces. b, When a charge current is applied parallel with the magnetization, the AHE vanishes, but spin-orbit interaction generates a flow of transversely polarized spin current that gives rise to anomalous spin-orbit torque (ASOT). The ASOTs (red arrows) are equivalent to out-of-plane fields (green arrows) that tilt the magnetization out of plane. and are the ASOTs and equivalent fields at the top (bottom) surfaces, respectively. c, Simulated distribution of the out-of-plane magnetization in a 32 nm Py film driven by equal and opposite ASOTs on the surfaces, scaled by the maximum value.

Interconversion between transversely polarized spin current and charge current has been recently studied in ferromagnetic multilayers16–19 with considerable spin-charge conversion efficiency. Due to strong spin dephasing8,20, transversely polarized spin current decays rapidly near the surface of the ferromagnet; therefore, the spin-charge conversion observed in these studies are likely due to interfacial spin-orbit interaction21. Transversely polarized spin current generated in the bulk of ferromagnets has yet to be demonstrated. Recently it has been theoretically predicted that transversely polarized spin current is allowed in diffusive ferromagnets22 because the spin-orbit interaction, which generates spin current, competes with spin dephasing. In this paper, we also show that transversely polarized spin current can exist in ferromagnets in the clean limit, using first-principles calculations. We refer to the mechanism of the current-induced transversely polarized spin current in the bulk ferromagnet as the transverse spin Hall effect (TSHE). We emphasize that the TSHE is different from previously studied spin current generation in the AHE configuration12, where the spin polarization is necessarily parallel with the magnetization.

Under the assumption that the current-induced ASOT in a ferromagnet results in a small perturbation to the magnetization, the ASOTs are equivalent to effective magnetic fields in the -direction23 that tilt the magnetization out of plane, as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

The out-of-plane magnetization tilting, , due to the ASOT at the top () and bottom () surfaces can be derived as

| (1) |

where is the total thickness of the film, is the exchange length, is an applied external magnetic field in the -direction, is the effective demagnetizing field, is the saturation magnetization, and is the projection of the unit magnetization along the -direction. Here, the ASOT is assumed to be located only at the surfaces and the surface anisotropy is neglected. (See Supplementary Information section S4 for the derivation of Eq. (1), a discussion of why ASOT can be treated as a pure surface effect, and a numerical analysis that takes into account the surface anisotropy.)

Because exchange coupling in the magnetic material aligns the magnetization, the spatially-antisymmetric magnetization tilting is expected to be measurable only when the magnetic material is thicker than the exchange length (e.g. 5.1 nm for Ni80Fe20). A simulation of the out-of-plane magnetization distribution due to ASOT in a 32 nm Ni80Fe20 (Py) film is shown in Fig. 1c.

To observe ASOT, we fabricate a sample with structure substrate/AlOx(2)/Py(32)/AlOx(2)/SiO2(3), where the numbers in parentheses are thicknesses in nanometers; the substrate is fused silica, which allows optical access to the bottom of the sample. Py is chosen because it is magnetically soft and widely used for the study of spin-orbit torques. The film is lithographically patterned into a square and connected by gold contact pads, as shown in Fig. 2(a). When an electric current of 40 mA is applied directly through the sample, ASOTs at the top () and bottom () surfaces lead to non-uniform magnetization tilting, as described by Eq. (1). When a calibration current of 400 mA is passed around the sample, an out-of-plane Oersted field is generated that uniformly tilts the magnetization out of plane, which is used for calibrating the magnitude of the ASOTs:

| (2) |

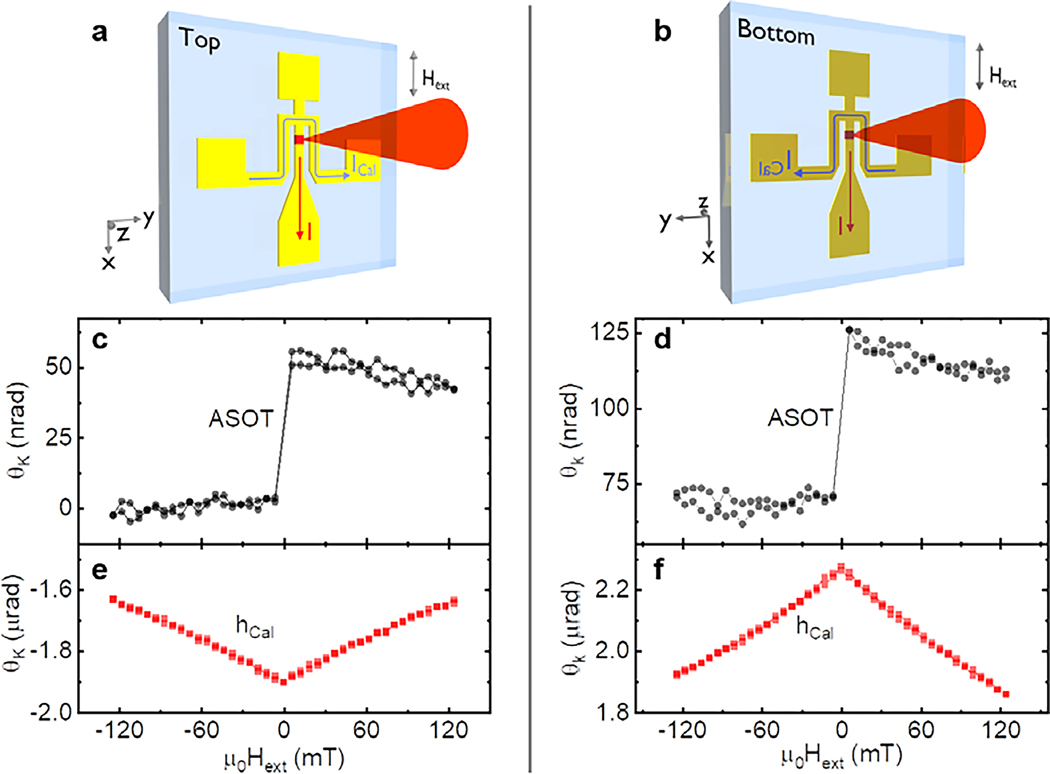

Figure 2. Symmetry of the anomalous spin-orbit torque.

Diagrams of the measurement configurations with the laser incident on a, the top and b, the bottom of the sample. The plots below each diagram correspond to signals measured in that diagram’s configuration. c-d, The measured Kerr rotation signals for when current is applied through the sample, which arise from ASOTs. e-f, The measured Kerr rotation signals for when the calibration field is applied.

We detect the magnetization changes using the polar magneto-optic Kerr effect (MOKE) by measuring the Kerr rotation and ellipticity change of the polarization of a linearly polarized laser reflected from the sample24,25. The penetration depth of the laser in Py is approximately 14 nm, which is less than half the thickness of the 32 nm Py. Therefore, the MOKE response is more sensitive to the ASOT-induced out-of-plane magnetization on the surface on which the laser is directly incident.

The Kerr rotation due to ASOT as a function of the external field (shown in Figs. 2c and d) resembles a magnetization hysteresis, as can be understood from Eq. (1). The overall offsets of the Kerr rotation signals are due to a residual, current-induced out-of-plane Oersted field due to imprecision in locating the MOKE probe spot exactly in the center of the sample, (see Supplementary Information Fig. S4b for MOKE signal dependence on the laser spot position), which does not depend on the in-plane magnetization orientation23. In contrast, when a uniform calibration field is applied, the Kerr rotation is symmetric as a function of external field (see Fig. 2e and f), consistent with Eq. (2). The Kerr rotation due to ASOT on the top (Fig. 2c) and bottom (Fig. 2d) surfaces are the same sign, in agreement with our phenomenological model (Fig. 1c), which predicts the bottom ASOT has similar magnitude but opposite sign as the top ASOT. In contrast, the Kerr rotation due to the calibration field (Fig. 2e and f) changes sign because is reversed upon flipping the sample.

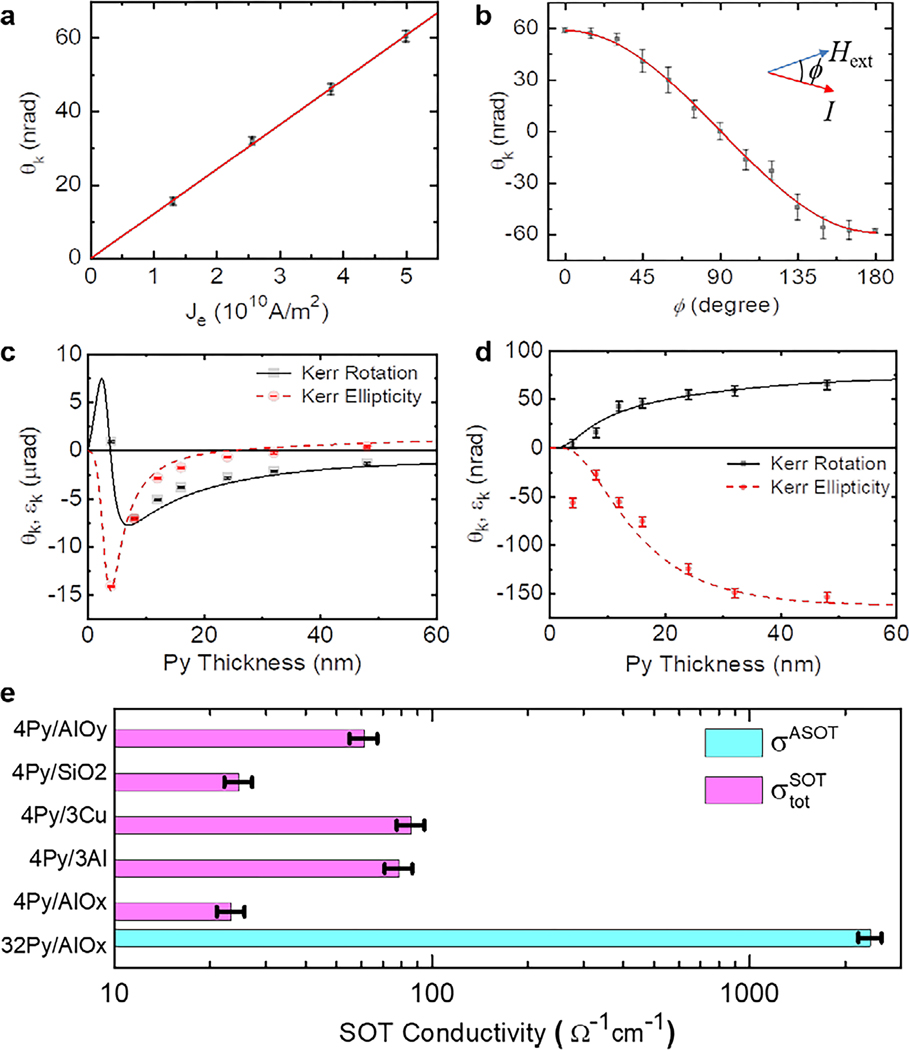

As shown in Fig. 3a, the polar MOKE response due to ASOT is linear with applied electric current, indicating no significant heating-related effects up to 5 × 1010 A/m2 current density. As shown in Fig. 3b, the polar MOKE response exhibits a cosine dependence on the relative angle between the electric current and the magnetization, consistent with Eq. (1).

Figure 3. Dependence of ASOT on current density, angle, thickness and the interface.

Kerr rotation change as a function of a, current density and b, the angle between current direction and magnetization. Kerr rotation (experimental, black squares; fit, black solid line) and ellipticity change (experimental, red circles; fit, red dashed line) c, due to the calibration field, and d, due to ASOT. e, Comparison between total SOT conductivities () measured for 4 nm Py with different capping layers, and the bottom-surface ASOT conductivity () of 32 nm Py. Error bars indicate single standard deviation uncertainties. In all these samples, the other side of the Py is in contact with AlOx.

Unlike the Oersted field, which depends on the total current, ASOT should depend on the current density. To confirm this, we grow a series of AlOx(2)/Py(t)/AlOx(2)/SiO2(3) films on silicon substrates with 1 μm-thick thermal oxide, where varies from 4 nm to 48 nm. For all samples, we apply the same current density of 5 × 1010 A/m2, and use MOKE to quantify the ASOT. To fit the measured MOKE results, we use a propagation matrix method24 (see method section and Supplementary Information S5) to numerically simulate the MOKE signal as a function of the Py thickness. As presented in Fig. 3c, the validity of the method is first verified by a thickness-dependent calibration measurement, where a uniform 0.85 mT out-of-plane calibration field is applied to all samples. To extract the ASOT amplitude, the top-surface Kerr rotation and the ellipticity change due to the ASOT is fitted in Fig. 3d. The only free fitting parameter is the ASOT on the top surface, , which is assumed to be the same for all Py thicknesses under the same current density and to have equal magnitude and opposite sign as the ASOT on the bottom surface . The good agreement between experiment and simulation supports the assumption that ASOT depends on current density. The ASOTs are extrapolated to be from the fitting♣. Relating this torque to a spin current allows us to find the Spin-Hall-angle-like efficiency of the ASOT , where is the electron charge, is the electric current density and is the reduced Planck constant; this efficiency is comparable with the effective spin Hall angle of Pt (0.056 ± 0.005) measured in a Pt/Py bilayer7. The corresponding ASOT conductivity for 32 nm Py is calculated as , where is the applied electric field. In Fig. 3d, the deviation of the ASOT-induced change in Kerr ellipticity from the model for the 4 nm Py sample can be accounted for if a 1% variation between and is assumed, which may be due to a slight difference in spin relaxation at the two interfaces (see Supplementary Information section S6 for further discussion).

Since ASOT results in magnetization changes near the surface, the extracted ASOT values may be influenced by spin-orbit interaction at the interface with the capping layer, such as Rashba-Edelstein spin-orbit coupling26–28. To determine the relative contribution of such interface effects, we compare the ASOT at the top surface of the AlOx(3)/Py(32)/AlOx(3) sample with the total spin-orbit torque (SOT) in a series of control samples, AlOx(3)/Py(4)/Cap, where Cap is varied among AlOx(3), AlOy(3, different oxidation time), SiO2(3), Cu(3)/SiO2(3) and Al(3)/SiO2(3). These capping layer materials are often assumed to have weak spin-orbit interaction due to their being light elements, but they will change the electrostatic properties and band structures of the top interface. The bottom surface is the same as for the 32 nm Py sample and thus any interfacial contribution from the bottom surface should have similar ASOT conductivity. Since Py is only 4 nm in these control samples (thinner than the exchange length), the magnetization uniformly responds to the total SOT, which is a sum of the ASOTs at the top and bottom surfaces (). Interfacial spin-orbit effects, like the Rashba-Edelstein effect or interface-generated spin currents, are highly material- and structure-specific21,29. For this reason, if either effect played an important role in the ASOT, we would not expect quantitatively, or even qualitatively, similar results for interfaces with substantially different characteristics. Should there be a significant interface-dependence of the ASOT, a large total SOT will be observed in some of these control samples with asymmetric interfaces. As shown in Fig. 3e, all samples exhibit total SOT conductivities of at most 4% of the bottom-surface ASOT conductivity of the 32 nm Py sample. This suggests that the top-surface ASOT, which varies less than 4% among Py with different capping layers, does not contain a substantial contribution from the interface of the Py with the capping layers.

The insensitivity of ASOT to the interface implies that it arises from the bulk spin-orbit interaction within the magnetic material. ASOT can be phenomenologically understood as the result of the TSHE – a flow of transversely polarized spin current generates ASOT by transferring spin angular momentum from one surface to the other. We evaluate the TSHE conductivity using linear response in the Kubo formalism in the clean limit using density functional theory30 (see Supplementary Information section S7 for technical details). First-principles calculations for Ni, Fe and Co all show significant TSHE conductivities, summarized in Table 1. We also measure the ASOT conductivities of these materials experimentally, provided in Table 1. For comparison, we also calculate and measure the AHE conductivities for these materials. If the ASOT is only due to the TSHE from the intrinsic band structure, the calculated TSHE conductivity should match the measured ASOT conductivity. As shown in Table 1, the conductivities are similar in magnitude as those calculated, indicating that the intrinsic mechanism may significantly contribute to the ASOT. However, the signs for Fe and Co are opposite between measured and calculated values; this may be because the intrinsic mechanism is not the sole source of ASOT and other mechanisms should be taken into account. By analogy with the AHE, we expect that extrinsic mechanisms such as skew scattering10,31 can also contribute to generating transversely polarized spin current and hence ASOT (see Supplementary Information Fig. S8).

Table 1. Measured and calculated electrical, AHE and ASOT conductivities.

All values have units of . All experimental data are extrapolated based on 40 nm sputtered polycrystalline films, sandwiched between two 3 nm AlOx layers. The positive sign for the ASOT conductivity corresponds to the scenario that if the applied electric field is in the -direction, the generated spin current flowing in the -direction has spin moment in the --direction. Under this choice, the spin Hall conductivity of Pt is positive.

| Ni | Fe | Co | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation | Structure | FCC | BCC | HCP |

| AHE Conductivity | −1.3 | 0.72 | 0.45 | |

| TSHE Conductivity | 3.92 | 1.05 | −0.24 | |

| Experiment | Structure | FCC | BCC | HCP |

| Conductivity | 56 | 32 | 46 | |

| AHE Conductivity | − 0.5 ± 0.05 | 0.5± 0.05 | 0.3± 0.03 | |

| ASOT Conductivity | 3.5 ± 0.1 | −1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | |

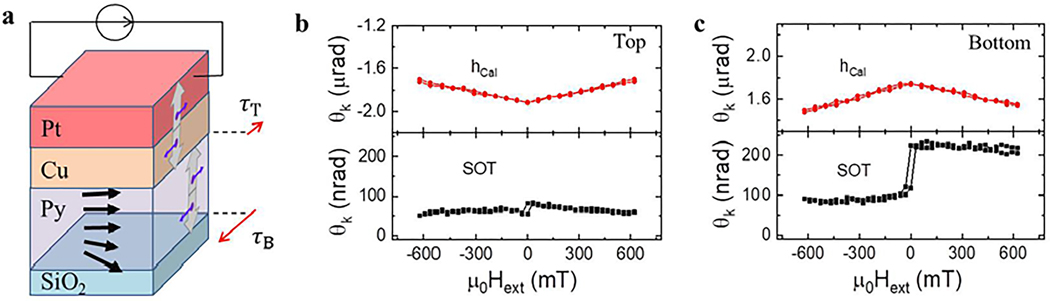

The existence of ASOT may change some of the conventional understanding of spin-orbit torques in magnetic multilayers. For example, an electric current can generate a net spin-orbit torque in a SiO2/Py/Cu/Pt multilayer acting on the Py magnetization. The net spin-orbit torque is the superposition of spin-orbit torques at the two surfaces of the Py layer. Although Pt or the Pt/Cu interface were often thought to be the source for spin-orbit torque, we find that the spin-orbit torque at the SiO2/Py interface is much larger than that at the Py/Cu interface, as shown in Fig. 4. This is because the spin-orbit torque at the Py/Cu interface is the superposition of ASOT in Py and the external spin-orbit torque due to spin current generated from Pt, the two of which are in opposite directions. Therefore, although the total spin-orbit torque appears to be consistent with the spin Hall angle of Pt, the actual spin-orbit torque at the SiO2/Py interface is in fact greater than that at the Py/Cu interface.

Figure 4.

(a) Illustration of the asymmetric SOTs in a SiO2/Py(32)/Cu(3)/Pt(2)/AlOx(3) multilayer. Measurement configurations are the same as in Figure 2. The net spin torques at the top surface , and at the bottom surface are probed by MOKE, where is the spin-orbit torque due to spin current generated from Pt injected into Py. From the spin current shown in the figure, it can be expected that is smaller than , contrary to common understanding. (b) The measured Kerr rotation signals when light probes the top surface with calibration field applied and current-driven spin-orbit torque applied. (c) The measured Kerr rotation signals when the bottom surface is interrogated with calibration field applied and current-driven spin-orbit torque applied. While the Kerr rotations due to the calibration signal are similar in magnitude, those due to current-driven spin-orbit torque are much larger at the bottom surface than at the top surface.

Although the total ASOT equals zero in an isolated magnetic layer with symmetric surfaces, such symmetry is likely broken when the ferromagnet is in contact with a nonmagnetic layer with strong spin-orbit coupling (see Supplementary Information section S9 for more discussion). If there is an asymmetry in the ASOT at the two surfaces of the magnetic layer, a net spin-orbit torque is expected, which contributes to the total spin-orbit torque in magnetic multilayers. This net spin-orbit torque, arising from the spin-orbit interaction of the ferromagnet itself, may have been previously overlooked.

Methods

Sample Fabrication

The samples used in this study are fabricated via magnetron sputtering. The AlOx layers are made by depositing 2 nm Al film and subsequent oxidization in an oxygen plasma.

MOKE Measurement of ASOT

The MOKE measurements are performed with a lock-in balanced detection system25, which is illustrated in Supplementary Information Fig. S3. An alternating current with frequency 20.15 kHz is applied through the patterned sample and the ASOT-induced MOKE response at the same frequency is measured. We use a Ti:sapphire mode-locked laser with ≈100 fs pulses at 80 MHz repetition rate with center wavelength 780 nm; the detectors used are slow relative to the repetition rate, so the measured signals are averaged over the pulses. The laser beam is focused by a 10x microscope objective into a spot of ~4 μm diameter. Laser power below 4 mW is used to avoid significant heating effects. To eliminate the quadratic MOKE contribution, the average is taken of the signals for incident laser polarizations of 45° and 135° with respect to the magnetization25. A combination of a second half-wave plate and a Wollaston prism is used to analyze the Kerr rotation signal. For Kerr ellipticity measurements, a quarter-wave plate is inserted before the half-wave plate.

Fitting of the thickness-dependent MOKE signal

In the simulations, the magnetic film is discretized into many sublayers of thickness 0.4 nm. By assuming equal and opposite ASOT, , at the top and bottom of each sublayer, we calculate the resultant out-of-plane magnetization using numerical methods (see Supplementary Information section S4). For calibration, a constant out-of-plane calibration field is applied to all sublayers, and the out-of-plane magnetization is calculated using the same numerical methods. Based on the calculated out-of-plane magnetization distribution, the polar MOKE response is determined using the propagation matrix method and taking into account multiple reflections (see Supplementary Information section S5). The above processes provide linear relationships between and with the predicted MOKE response for various film thicknesses. In modelling the thickness-dependent MOKE response for calibration, shown in Fig. 3a, all parameters are measured by other techniques. The good agreement corroborates our numerical model. In the fitting of the thickness-dependent MOKE response due to ASOT, shown in Fig. 3b, we assume fitting parameter is the same for all film thicknesses under the same current density. All other parameters are the same as those used in modelling the calibration result. The good agreement shown in Fig. 3b confirms our assumption that depends on the current density.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work done at the University of Denver is partially supported by the PROF and by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number ECCS-1738679. W.W., D.G.C. and V.O.L. acknowledge support from the NSF-MRSEC under Award Number DMR-1720633. T.W., Y.W, and J.Q.X acknowledge support from NSF under Award Number DMR-1505192. V.P.A. acknowledges support under the Cooperative Research Agreement between the University of Maryland and the National Institute of Standards and Technology Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology, Award 70NANB14H209, through the University of Maryland. We would also like to thank Mark Stiles and Emilie Jue for critical reading of the manuscript, and Xiao Li for illuminating discussions.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

All the uncertainties in this letter are single standard deviation uncertainties. The principle source of uncertainty here is the fitting uncertainty, which is determined by a linear regression analysis by plotting the experimental data as a function of the simulation results.

References

- 1.Hirsch JE Spin Hall effect. Physical Review Letters 83, 1834–1837, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1834 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato YK, Myers RC, Gossard AC & Awschalom DD Observation of the spin hall effect in semiconductors. Science 306, 1910–1913, doi: 10.1126/science.1105514 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura T, Otani Y, Sato T, Takahashi S. & Maekawa S. Room-temperature reversible spin Hall effect. Physical Review Letters 98, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.156601 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mihai Miron I. et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189–U188, doi: 10.1038/nature10309 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L. et al. Spin-Torque Switching with the Giant Spin Hall Effect of Tantalum. Science 336, 555–558, doi: 10.1126/science.1218197 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall EH On the “Rotational Coefficient” in Nickel and Cobalt. Proc. Phys. Soc. London 4, 325 (1880). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L, Moriyama T, Ralph DC & Buhrman RA Spin-Torque Ferromagnetic Resonance Induced by the Spin Hall Effect. Physical Review Letters 106, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.036601 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh A, Auffret S, Ebels U. & Bailey WE Penetration Depth of Transverse Spin Current in Ultrathin Ferromagnets. Physical Review Letters 109, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.127202 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang SF Spin Hall effect in the presence of spin diffusion. Physical Review Letters 85, 393–396, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.393 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagaosa N, Sinova J, Onoda S, MacDonald AH & Ong NP Anomalous Hall effect. Reviews of Modern Physics 82, 1539–1592, doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.82.1539 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miao BF, Huang SY, Qu D. & Chien CL Inverse Spin Hall Effect in a Ferromagnetic Metal. Physical Review Letters 111, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.066602 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taniguchi T, Grollier J. & Stiles MD Spin-Transfer Torques Generated by the Anomalous Hall Effect and Anisotropic Magnetoresistance. Physical Review Applied 3, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.3.044001 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang HL, Du CH, Hammel PC & Yang FY Spin current and inverse spin Hall effect in ferromagnetic metals probed by Y3Fe5O12-based spin pumping. Applied Physics Letters 104, doi: 10.1063/1.4878540 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernyshov A. et al. Evidence for reversible control of magnetization in a ferromagnetic material by means of spin-orbit magnetic field. Nature Physics 5, 656–659, doi: 10.1038/nphys1362 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciccarelli C. et al. Room-temperature spin-orbit torque in NiMnSb. Nature Physics 12, 855–860, doi: 10.1038/nphys3772 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian D. et al. Manipulation of pure spin current in ferromagnetic metals independent of magnetization. Physical Review B 94, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.94.020403 (2016). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das KS, Schoemaker WY, van Wees BJ & Vera-Marun IJ Spin injection and detection via the anomalous spin Hall effect of a ferromagnetic metal. Physical Review B 96, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.220408 (2017). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphries AM et al. Observation of spin-orbit effects with spin rotation symmetry. Nature Communications 8, doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00967-w (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baek SHC et al. Spin currents and spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic trilayers. Nature Materials 17, 509–513, doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0041-5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ralph DC & Stiles MD Spin transfer torques. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 320, 1190–1216, doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2007.12.019 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amin VP, Zemen J. & Stiles MD Interface-Generated Spin Currents. Physical Review Letters 121, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.136805 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pauyac CO, Chshiev M, Manchon A. & Nikolaev SA Spin Hall and Spin Swapping Torques in Diffusive Ferromagnets. Physical Review Letters 120, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.176802 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan X. et al. Quantifying interface and bulk contributions to spin-orbit torque in magnetic bilayers. Nature Communications 5, doi: 10.1038/ncomms4042 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiu ZQ & Bader SD Surface magneto-optic Kerr effect. Review of Scientific Instruments 71, 1243–1255, doi: 10.1063/1.1150496 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan X. et al. All-optical vector measurement of spin-orbit-induced torques using both polar and quadratic magneto-optic Kerr effects. Applied Physics Letters 109 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pesin DA & MacDonald AH Quantum kinetic theory of current-induced torques in Rashba ferromagnets. Physical Review B 86, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.86.014416 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurebayashi H. et al. An antidamping spin-orbit torque originating from the Berry curvature. Nature Nanotechnology 9, 211–217, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.15 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baek S.-h. C. et al. Spin currents and spin–orbit torques in ferromagnetic trilayers. Nature Materials, doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0041-5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SR, Kim CH, Yu J, Han JH & Kim C. Orbital-Angular-Momentum Based Origin of Rashba-Type Surface Band Splitting. Physical Review Letters 107, 156803, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.156803 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang XJ, Yates JR, Souza I. & Vanderbilt D. Ab initio calculation of the anomalous Hall conductivity by Wannier interpolation. Physical Review B 74, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.74.195118 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmann A. Spin Hall Effects in Metals. Ieee Transactions on Magnetics 49, 5172–5193, doi: 10.1109/tmag.2013.2262947 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.