Abstract

Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence angiography has emerged as an intraoperative method to accurately assess real-time tissue vascularity, perfusion and anastomotic patency in flap surgery. We illustrate a complex case of elbow reconstruction in an elderly patient with a free anterolateral thigh flap, which relied on intraoperative ICG to evaluate the flap pedicle and map the site of arterial occlusion. Supermicrosurgical instrumentation was employed to perform complex perforator-to-perforator anastomosis following resection of the vascular site of the lesion. These unique applications in a patient of known surgical risk enabled immediate flap salvage, and after 6 months postoperatively, the flap remained healthy with adequate wound healing.

Keywords: ICG, ALT, Salvage, Occlusion, Microsurgery, Elbow

Introduction

Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence angiography has emerged as an intraoperative method to accurately assess real-time tissue vascularity, perfusion and anastomotic patency in flap surgery.1 ICG is a water-soluble dye that binds to plasma proteins, and exhibits fluorescent property when subjected to near-infrared light.1 Several advantages of ICG angiography in microsurgery were established previously,1, 2, 3 including reduced partial flap loss and re-exploration rate.2 We illustrate a complex case of elbow reconstruction with a free anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap, which relied on intraoperative ICG to evaluate the flap pedicle and detect the site of arterial occlusion.

Patient case

The patient was a retired 65-year-old man referred for reconstruction of a skin and fascial defect overlying the posterolateral column of the right distal humerus. The background involved a right linked cemented total elbow replacement (TER) indicated for rheumatoid arthritis, performed 5 months prior to the reconstruction, that had become infected postoperatively. The TER was explanted and a cement spacer was subsequently inserted 2 months prior to reconstruction. The patient also had a history of hypertension and mild asthma. A non-smoking status was reported. Following discussion, the patient underwent a free ALT flap to reconstruct the upper limb defect. The total defect measured 11 by 7 cm in size (Fig. 1). The ALT flap was raised on a single perforator, the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery, with an intramuscular course through the vastus lateralis. The flap displayed acceptable perfusion before detachment from the thigh.

Fig. 1.

The skin and fascial defect overlying the posterolateral column of the right distal humerus on a background of infected total elbow replacement indicated for rheumatoid arthritis.

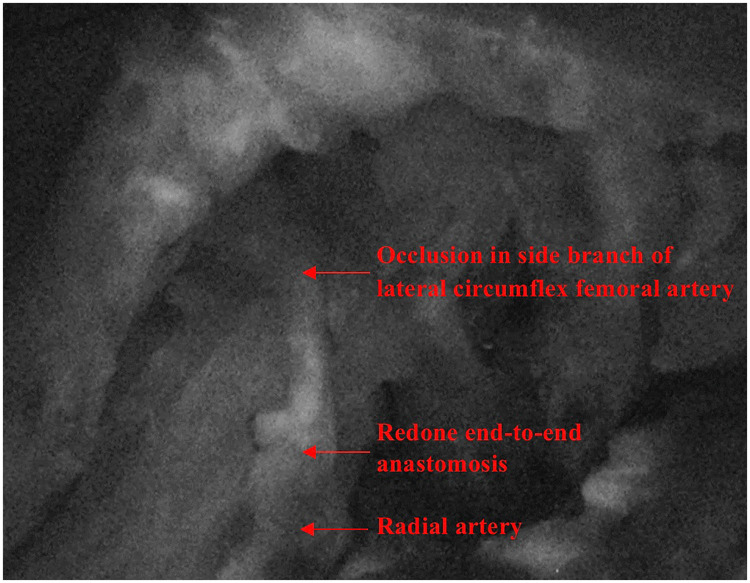

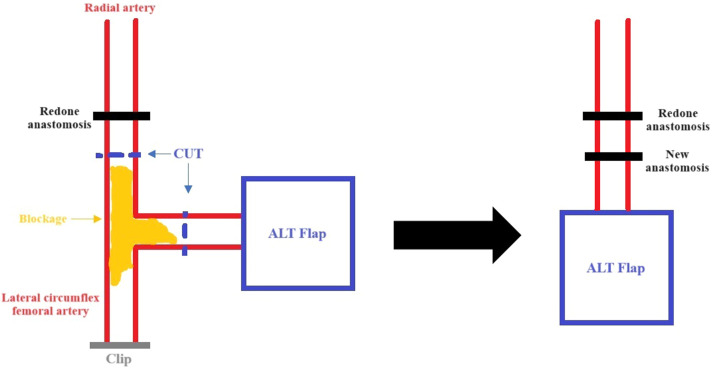

The pedicle was tunnelled subcutaneously to the antecubital fossa. Since an end-to-side anastomosis onto the brachial artery was unachievable, despite the pedicle being 10 cm long with a diameter <0.8 mm, the radial artery was ligated and rotated to supply the flap. Two veins were anastomosed using 1.5 mm and 2.5 mm standard venous couplers, respectively, one onto the vena comitans of the radial artery and the other onto the cephalic vein. The microsurgical arterial anastomosis to the radial artery was conducted end-to-end using 9−0 interrupted sutures. The flap was assessed with ICG and showed no perfusion under imaging (Leica M530 OHX). The end-to-end anastomosis was repeated because it was felt a potential arterial thrombosis had occurred. At this juncture, 5000 units of heparin were administered intravenously, and heparinised saline was flushed into the flap. Repeat ICG displayed satisfactory flow at the connection between the recipient and donor arteries, yet the flap did not appear perfused (Supplement 1). With ICG angiography, the entire pedicle was traced and it was identified that blood flow to the flap was reduced by an occlusion occurring at a side branch of the donor vessel distal to the redone anastomosis (Fig. 2). Potentially, this was an area of atheroma that had become critically occluded. Based on these findings, the blocked segment was resected around 2 cm distal to the redone anastomosis, and a perforator-to-perforator anastomosis was performed using 10−0 interrupted sutures (Fig. 3) with supermicrosurgical instrumentation. ICG angiography thereafter demonstrated adequate flow through this anastomosis and a well-perfused flap. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 6. After 6 months postoperatively, the flap remained healthy and wound healing was satisfactory (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

ICG angiography was used to evaluate perfusion of the ALT flap. The occlusion distal to the site of the redone end-to-end anastomosis prevented adequate flow of ICG past it.

Fig. 3.

A schematic representation of the procedure carried out to salvage the ALT flap following assessment of the flap pedicle with ICG. The arterial blockage in the side branch was a suspected atheroma.

Fig. 4.

The salvaged ALT flap integrated into the elbow recipient site, and remained clinically stable 6 months following the elbow defect reconstruction.

Discussion

With current evidence, ICG angiography has become an attractive tool for assisting microsurgical free flap procedures in perforator selection, flap perfusion evaluation, and reducing re-exploration and fat necrosis incidence.2, 3, 4 The relatively high expense of ICG,1 however, has decreased its wider application to all patient groups, and has restricted its use entirely in some centres. It is therefore important to identify specific patients that would benefit most from this intraoperative assessment method. For the case described herein, ICG salvaged the ALT flap in an older patient with comorbidities that predisposed to atherosclerosis. The patient also had darker skin tone, which complicated the interpretation of findings from clinical flap assessment alone.

The utility of ICG to scan the pedicle for occlusions proved significant for this patient's flap salvage. An atheroma was suspected for the arterial occlusion in this case. Firstly, the occlusion was situated in an arterial side branch, which is a known preferred location for atheroma formation.5 Secondly, there were medical risk factors such as hypertension present. Although the flap was heparinised, dislodgement of a relatively small clot may have transformed a partially occluding atheroma into a lesion causing critical stenosis. Some alternative causes of arterial occlusion included damage at the pedicle (such as iatrogenic thermal injury) and clot propagation. We do acknowledge that the excised vessel segment was not subjected to histological examination and, therefore, no definite evidence for the cause of the thrombosis was obtained.

Furthermore, although perforator-to-perforator anastomosis for flap salvage was previously described, the utility of ICG in providing a road map for this technique has not been detailed by current literature.6 The dye enabled accurate localisation of the lesion. It is worth noting that severe adverse reaction to ICG has been reported in literature and hence preoperative allergy testing is recommended.4 Nonetheless, in comparison with ICG, current alternatives such as the flow coupler technology and laser Doppler flowmetry are less suitable for precisely identifying the anatomical location of lesions in blood vessels.

Although no level-one evidence has detailed our experience described herein, ICG angiography in this patient was a useful clinical adjunct for mapping vessel lesions and supporting the perforator-to-perforator technique in free flap surgery.

Statements and Declarations

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

No funding received.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

None required.

Patient consent

Signed informed consent document was obtained.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2024.10.001.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Supplement 1. Relative to native skin, the ALT flap remained dark with ICG, which evidenced poor flap perfusion.

References

- 1.Faderani R., Yassin A.M., Brady C., Caine P., Nikkhah D. Versatility of Indocyanine Green (ICG) dye in microsurgical flap reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023;76:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2022.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choudhary S., Khanna S., Mantri R., Arora P. Role of Indocyanine green angiography in free flap surgery: a comparative outcome analysis of a single-center large series of 877 consecutive free flaps. Indian J Plast Surg. 2023;56(3):208–217. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-57270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varela R., Casado-Sanchez C., Zarbakhsh S., Diez J., Hernandez-Godoy J., Landin L. Outcomes of DIEP flap and fluorescent angiography: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(1):1–10. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li K., Zhang Z., Nicoli F., et al. Application of indocyanine green in flap surgery: a systematic review. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2018;34(2):77–86. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasilewski J., Niedziela J., Osadnik T., et al. Predominant location of coronary artery atherosclerosis in the left anterior descending artery. The impact of septal perforators and the myocardial bridging effect. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2015;12(4):379–385. doi: 10.5114/kitp.2015.56795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velazquez-Mujica J., Losco L., Aksoyler D., Chen H.C. Perforator-to-perforator anastomosis as a salvage procedure during harvest of a perforator flap. Arch Plast Surg. 2021;48(4):467–469. doi: 10.5999/aps.2020.02194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1. Relative to native skin, the ALT flap remained dark with ICG, which evidenced poor flap perfusion.