ABSTRACT

Aim

The aim of this review was to examine the evidence on multidisciplinary inpatient community rehabilitation intervention programmes for frail older people to establish what frailty rehabilitation programmes if any have been described within the literature and to identify gaps in knowledge and outcome measures used.

Design

A scoping review was conducted.

Methods

Using the Joanna Briggs Institute approach to scoping reviews, a comprehensive literature search was conducted accessing MEDLINE via PubMed, PsychINFO (via Proquest), CINAHL Complete (via EBSCO) and the Cochrane Library and a limited search of the grey literature was undertaken.

Results

Four articles met the inclusion criteria. A heterogenous approach to geriatric rehabilitation was evident across the literature. While the reported rehabilitation interventions were aimed at frail older people, the predominant focus of frailty rehabilitation programmes were on the physical functionality of the older person with an absence or limited measurement of any psychosocial, cognitive or spiritual outcomes or aspects of quality of life.

Conclusion

This scoping review exposed the paucity of scientific evidence supporting the need for inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitative programmes for frail older people wishing to remain at home.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Timely access to inpatient integrated frailty rehabilitation programmes can improve the quality of life and reduce the likelihood of hospital admissions for frail older people who wish to remain living in their own homes. With the current dearth of published evidence available, there is a necessity to undertake further research to understand the form, content and best models of delivery for frailty rehabilitative services for clinical, policy and practice purposes.

Patient or Public Contribution

There was no patient or public contribution.

1. Introduction

Keeping a progressively ageing population healthy and functionally independent well into old age is challenging considering the population predictions for this age group. Globally, projections indicate between 2015 and 2050, the population of people over 60 years of age will double from 12% to 22% (World Health Organization 2018). The Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD 2020) predict between 2020 and 2100 there will be a two‐and‐a‐half‐fold increase in the number of people living over the age of 80 years.

Healthy ageing is defined as: ‘the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables wellbeing in old age’ (World Health Organization 2018). Functional ability is broader than the physical functioning of the body, implying the person's ability to be and do what they consider and value as part of living their lives (World Health Organization 2023). Healthy ageing is essentially about the person living in a supportive environment that maintains their intrinsic capacity and functional ability (World Health Organization 2018). While plenty of older people live healthy and independent lives, ageing is also associated with challenges due to functional decline. Roe et al. (2017) estimate the prevalence of frailty in community‐dwelling older people in Ireland is 24%. Due to demographic changes and population ageing in Ireland, chronic illness and frailty have become an issue of interest from a clinical, public health and policy perspective.

Although frailty is not an inevitable part of ageing, it is increasingly common in people over 80 years of age (Clegg et al. 2013; Richter et al. 2022; Guasti et al. 2022). Frailty is regarded as the clinical condition capturing problematic ageing (Clegg et al. 2013; Heuberger 2011; Richter et al. 2022; Guasti et al. 2022). Importantly, while frailty is acknowledged to be related to the concepts of multimorbidity and disability, there is clear evidence frailty is associated with higher rates of health service utilisation. Roe et al. (2017) showed a statistically significant impact on the average amount of services accessed and used by frail older people including GP services, increased length of stay in hospital and outpatient visits. Developing interventions to prevent or delay disability and frailty, to preserve a person's physical ability, autonomy and quality of life (Kojima 2017) is a reasonable goal in keeping with the World Health Organizations definition of healthy ageing. Rehabilitation is defined as ‘a set of interventions designed to optimise functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment’ (World Health Organization 2023). The goal of rehabilitation and reablement interventions are to reduce hospitalizations, decrease admissions to long‐term care facilities and reduce the risk of mortality from frailty (Harrison Dening 2021).

A community rehabilitation unit (CRU) was established in XXXXX in 2003 to provide a multidisciplinary inpatient reablement programme designed to intervene between outpatients in an acute hospital and older people living in the catchment area of the community hospital.

In a study by Cowley et al. (2021) several successful models of inpatient rehabilitation care for older adults with frailty were identified. These models included intermediate care units, inpatient rehabilitation units and rehabilitation services situated within residential care settings or care homes. Among these, the community rehabilitation unit is an innovative model to address frailty in older individuals, although the popularity of this model differs worldwide. The service provides an opportunity for frail older people to be admitted to a 7‐day unit to complete a structured rehabilitation programme, rather than simply attend a more traditional 1 day per week rehabilitation service as an outpatient. The programme involves the multidisciplinary team carrying out a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) alongside intense therapy and nursing support. The primary goal was to restore the independence of the frail older person before they are discharged back to their homes and communities.

The primary goal of the CRU programme was to enable frail older people to remain in their homes, living independent lives for as long as possible. Since 2010, demographic data have been gathered concerning the patient population admitted to CRU; however, to date no specific multidisciplinary outcome measures have been used to evaluate the effectiveness of the rehabilitation intervention. To evaluate the impact of the CRU programme for frail older people attending the service, we conducted a scoping review to establish what frailty rehabilitation programmes if any have already been described or discussed within the literature.

2. Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to identify the nature of the evidence reporting multidisciplinary inpatient community rehabilitation programmes for frail older people to consider any gaps in knowledge, outcome measures used and issues requiring further investigation.

3. Methods

A scoping review designed in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) approach for scoping reviews (Peters et al. 2020a) expanding on the five stage methodological framework of Arksey and O'Malley (2005) and the work of Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien (2010) was conducted to identify and map the available evidence. In addition, the PRISMA‐ScR standards for reporting scoping reviews were also adopted (Tricco et al. 2018). In line with JBI guidance, consultation with key stakeholders and the specialist librarian (F.L.) was undertaken during the review process.

3.1. Stage 1—Identifying the Research Question

The process of identifying the research question progressed iteratively among the research team, with input from key stakeholders in the CRU and under the expert guidance of the specialist librarian. Following several consultations with the research team, the research question was agreed to focus more precisely on what is known from the existing literature about the availability of inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes for frail older people.

3.2. Stage 2—Identifying the Relevant Studies

In consultation with the specialist librarian, a comprehensive search strategy was developed. The focus of the search was restricted from January 2010 to August 2022. The eligibility criteria were structured with cognisance of the recommended Population, Concept and Context (PCC) pneumonic for scoping reviews (Peters et al. 2020a, 2020b) (Table 1). The search was limited to articles published in English and people over 65 years. Exclusion criteria included all papers addressing specific purpose rehabilitation, COVID‐19 patients, papers not incorporating a multidisciplinary team approach, patients who were not frail, and rehabilitation programmes not conducted within an inpatient setting.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| PCC category | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Frailty terms |

Non frail people Atrial fibrillation patients Depressed patients Dialysis patients Amputees Renal patients COVID‐19 patients |

| Concept |

Reablement/rehabilitation terms Intense/rapid rehabilitation Multidisciplinary |

Stroke rehabilitation Pulmonary/COPD rehabilitation Brain injury rehabilitation Oncology/palliative rehabilitation HIV rehabilitation Cardiac rehabilitation Robot‐assisted rehabilitation Neurorehabilitation Postfracture/postoperation rehabilitation Diabetes Postbariatric surgery Breast surgery Aortic aneurysms Endocarditis Eating disorders Acute admission |

| Context | Inpatient |

Outpatient department Emergency department |

A comprehensive systematic search for relevant literature was conducted using MEDLINE via PubMed, PsychINFO (via Proquest), CINAHL Complete (via EBSCO) and the Cochrane Library databases. Search terms included a combination of thesaurus and free‐text terms, specific for each database, using Boolean operators, truncation markers and MeSH and Subject headings as necessary to broaden the search and capture the relevant published literature. In order to identify the breadth of literature, we additionally undertook a limited search of the grey literature. This included conducting a focussed search using the advanced Google Scholar interface, hand searching and screening for publications meeting the inclusion criteria in the reference lists of the articles included for full review. In addition, citation searches of those included articles in Google Scholar and Web of Science were also conducted. All literature searches were executed by M.M. under the supervision of the specialist librarian (F.L.) and retrieved citations were stored on EndNote version 9.

3.3. Stage 3—Study Selection

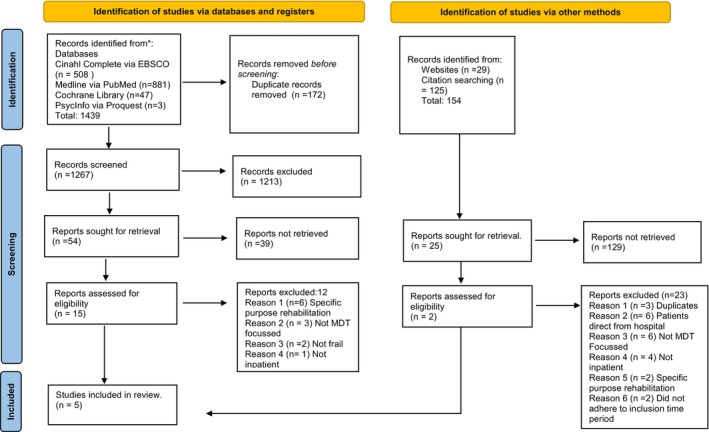

M.M. and M.B. screened all titles of the initial literature search results and agreed on the eligibility of literature to retain. Any discrepancies were resolved by M.C. Title and abstract screening of the retained literature was conducted by M.M. and M.B. and again M.C. independently reviewed and resolved any disagreements. Finally, full‐text review against the inclusion criteria was conducted by two pairs of reviewers (M.M., M.B., M.C. and A.D.). The team met to discuss any disagreements which were resolved by consensus. The results are reported in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (Page et al. 2021) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

3.4. Stage 4—Charting the Data

M.M. and M.B. undertook data extraction using a table template to chart the relevant characteristics of the data. Discussion among the research team led to further refinement and synthesis in accordance with JBI guidelines (Peters et al. 2020a). Finally, the following agreed characteristics of the data were charted including author, year, country, journal, aim, population, setting, intervention, methodology and key findings (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Key features of the five included studies.

| Author, publication year, country | Journal | Aim | Population, mean age, setting, year of study | Intervention, duration | Methodology, measures used | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chang et al. (2010) Taiwan |

Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics | To evaluate the outcomes of elderly inpatients with geriatric syndromes |

1031 patients (over 65 years) at start and 721 patients at end. (Mean age = 72 Years) 12 community hospitals January 2006–June 2007 |

Interdisciplinary geriatric team implementation programme. 10–11 Days |

Prospective study Independent variables:

Dependent variables:

Outcomes collected between June 2008 and October 2008 after discharge but not how long after via telephone interviews and chart review |

|

|

Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) Switzerland |

Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine | To evaluate patient characteristics predicting living at home after geriatric rehabilitation |

210 patients over 65 years at start and 158 completed. (Mean age = 76 years) Geriatric inpatient rehabilitation clinic February–November 2014 |

Inpatient multidisciplinary intervention (Does not specifically outline the precise intervention used.) 20 days = median length of stay |

Prospective study Independent variables:

Dependent variable:

Outcomes collected 3 months after discharge via postal questionnaire and if no response, telephoned. |

|

|

Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) Finland |

Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics | To examine the effects of geriatric inpatient rehabilitation on physical performance and pain in elderly men and women |

430 community‐dwelling persons (Mean age = 83 years.) Inpatient in two rehabilitation centres/hospital for disabled war veterans February 2006–2007. |

Inpatient multidisciplinary team intervention including individual and group therapy. 14–28 days |

Descriptive Intervention study Independent variables:

Dependent variables:

Does not state when post intervention follow‐up conducted via questionnaire and interview |

|

|

Grund et al. (2020) European Union Countries |

European Geriatric Medicine | To provide an overview on structures of geriatric rehabilitation across Europe |

(Mean age: 80 years) No country reported an upper age limit. 30% of countries had lower age group. Of those it was set at 60 and 65 years Survey sent in April 2018 to Board members from 33 European countries |

Average length of stay: 7–65 days 19 out of 20 countries which recognised geriatric rehabilitation had teams led by geriatrician. MDT‐nurses, physios, OTs, SALT, Social workers, dieticians and psychologists 17 out of 20 countries aimed to define treatment goals within the first few days of geriatric rehabilitation |

Online survey of 31 out of 33 European Geriatric Medicine full board members. Structure of survey:

|

|

|

King et al. (2021) Australia |

Australasian Journal of Ageing | To identify frailty measures and outcomes currently reported in randomised controlled trials involving frail older inpatients. |

46 to 1388 patients were 65 and over. (Mean age of the included studies ranged from 74 to 85 years) 2 RCTs community‐dwelling frail people to receive inpatient rehabilitation The rest were enrolled frail patients presenting to hospital |

9 (n = 12) studies trialled specialist geriatric led interventions with MDT comprehensive geriatric assessment. MDT inpatient geriatric rehabilitation by 1 study. Intervention periods varied from 12 days to 35 days |

Systematic Literature review 7 (n = 12) studies applied 6 tools to measure frailty

|

|

3.5. Stage 5—Collating, Summarising and Reporting the Results

The analysis of the extracted data incorporated both a basic descriptive numerical and narrative analysis of the relevant characteristics of the data addressing the research question. As per the guidance regarding a scoping review process neither the methodological quality nor the risk of bias of the included articles were appraised (Tricco et al. 2016).

4. Results

4.1. Selection of Studies

The search initially yielded 1439 articles (Figure 1). With 172 duplicates removed and titles screened, 1213 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Title and abstract screening were conducted on the remaining 54 articles resulting in a further exclusion of 39 papers. The remaining 15 articles underwent full‐text review, of which 12 met one of the exclusion criteria and were consequently excluded (Figure 1). An additional 154 articles were identified as grey literature, of which 129 were excluded. The remaining 25 were screened for title and abstract of which two were included in the final review. Consequently, the total result yielded four articles for inclusion in this review.

4.2. Description of Included Studies

Our scoping review highlights a dearth of global research and evidence focussing on multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation programmes for frail older people. The included articles originated in Taiwan (Chang et al. 2010), Switzerland (Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017), Finland (Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011) and European Union (EU) countries (Grund et al. 2020). Of the four included articles, three were intervention studies (Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017; Chang et al. 2010), the fourth article used an online survey to collect data (Grund et al. 2020). The three intervention studies broadly adopted similar methodological approaches gathering data before and after the rehabilitation programme intervention (Chang et al. 2010; Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011; Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017) to evaluate the impact of their programmes. However, none of these three studies used a control group, limiting the validity of their research findings.

By contrast, Grund et al. (2020) conducted an online survey of 31 European Geriatric Medicine Board members to ascertain the current structure of geriatric rehabilitation services in each of the 31 represented EU countries. Twenty‐six of the 31 respondents were geriatricians. While inpatient geriatric rehabilitation is provided in a variety of healthcare environments throughout the EU, only 20 countries formally recognise geriatric rehabilitation for both inpatients and outpatient's services while nine countries have no geriatric rehabilitation services. There are large differences in how geriatric rehabilitation is structured and delivered with 25 countries reporting several barriers including: financial, political and staffing shortages. Consequently, Grund et al. (2020) state it was difficult to establish a comprehensive and clear understanding of geriatric rehabilitation services in each country. In essence, there is a lack of consensus on what geriatric rehabilitation should look like.

There was a wide range of sample sizes reported in the four articles; from 1008 (Chang et al. 2010), 430 patients (Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011) to 210 patients (Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017). Grund et al. (2020) did not inquire about the numbers of patients attending rehabilitation services in their survey of European countries. However, postintervention, the reported attrition rates were considerable. Chang et al. (2010) reported an attrition rate of 11.4% (n = 115) and a further 19.3% (n = 172) died during the follow‐up period resulting in 71% (n = 721) completing the study, while Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) reported 75% (n = 158) completed their study. Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) did not report on attrition rates.

The lengths of stay for geriatric rehabilitation varied significantly ranging from 10 to 11 days for Chang et al. (2010), a median length of 20 days in the Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) study to 14–28 days in the Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) study. The European survey reported an average length of stay of between 7 days in Denmark and 65 days in Malta (Grund et al. 2020).

The mean age of the participants was the late 70s for two studies (Chang et al. 2010; Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017), 80 years for the European survey (Grund et al. 2020) while the highest mean age of 83 years was reported by Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011).

Following further analysis of extracted data, the evidence indicates there is a heterogenous approach to geriatric rehabilitation demonstrated in several ways. Firstly, the lack of clarity about what a CGA means is apparent. A CGA is a multidisciplinary assessment and diagnostic process evaluating the physical, psychosocial and functional capacity of the frail person within a coordinated plan used primarily by geriatricians (Szumacher et al. 2018). There is a recognised gold standard CGA for frail older people reported by Parker et al. (2018). For this scoping review, four articles reported a CGA was conducted on admission on every patient participating in their relevant rehabilitation programme (Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017; Chang et al. 2010; Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011). However, a variety of concepts were measured to complete this assessment indicating a lack of consensus about what a CGA should entail. In addition, while concepts such as cognition, physical performance, mood, functional status, frailty and healthcare utilisation were measured by most, there was a vast variety of measurement tools used making it quite a challenge to analyse.

Despite this disparity, there is consensus that two concepts, cognition and functional status should be measured (Chang et al. 2010; Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011; Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017). Cognition was measured using the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) by the three intervention studies (Chang et al. 2010; Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017; Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011). The Barthel Index was also used to measure functional status by the three intervention studies (Chang et al. 2010; Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017; Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011).

Secondly, the differences in the independent variables measured between four articles indicates the differences in what is perceived to be important for rehabilitation. For example, Chang et al. (2010) measured subjectively sensed problems including hearing, visual acuity, memory, sleep, multiple drug use, incontinence and falls while both Chang et al. (2010) and Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) measured nutritional status using the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) tool (Guigoz, Vellas, and Garry 1996). More emphasis on measuring aspects of mobility status was evident in Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) and Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) studies. Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) used the TUG (Timed up and Go) test (Podsiadlo and Richardson 1991), Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) measured the person's mobility limitation by their ability to walk 2 km and 0.5 km and their stair climbing activity. Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) determined the participants' multiple morbidities using the CIRS (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale) (Huntley et al. 2012) as well as using the VES‐13 scale (Vulnerable Elders Survey) (Saliba et al. 2001) to measure age, self‐rated health, physical function and functional disability. Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) also measured self‐rated health, number of chronic diseases, medications and form of dwelling. Finally, both Chang et al. (2010) and Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) measured depression using the self‐reported Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).

4.3. The Intervention Programmes

The specifics of the interventions implemented for inpatient geriatric rehabilitation were reported by the three intervention studies (Chang et al. 2010; Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017; Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011) aimed at frail older people using a form of interdisciplinary goal setting priorities identifying the personal needs of the older person. However, the predominant focus of the rehabilitation programmes reported was on the physical functionality of the older person. The Swiss study by Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) affirmed improving mobility was a high priority goal in their rehabilitation programme of three treatment sessions per day for a total of 2 h daily, 6 days a week. The treatment was delivered by physical and occupational therapists as well as receiving exercise training in groups and aquatic exercise. The focus of the rehabilitation programme reported by Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) was to promote physical performance, independent living and well‐being. Individual physical therapy five times a week for 60 min was delivered consisting of a variety of content including: therapy for movement, exercise and pain as well as manual and training therapy. The participants in the Finnish study were war veterans who could participate in physical education groups consisting of balance, gym, aquatic and relaxation sessions five times a week for 30 min. Chang et al. (2010) study did not outline the components of their rehabilitation programme except stating interdisciplinary care was delivered with the emphasis on rehabilitation and the management of geriatric syndromes. Grund et al. (2020) described the structures of geriatric rehabilitation in Europe; however, neither described nor ascertained the specific details about what the geriatric rehabilitation programmes encompassed.

Notwithstanding the importance of a strong focus on physical functioning and mobility based on evidence within these rehabilitation programmes, there is a distinct absence of any other type of treatment or therapy from other members of the multidisciplinary team. In addition, there is a lack of focus on a quality‐of‐life perspective for the individual frail older person engaging with the reported interventions despite, for example, the aim of Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) rehabilitation programme being the promotion of well‐being. However, Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) and Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen (2011) did assess the older person's living arrangements and delivered some aspects of the programme within a group, yet there was no measurement of the impact of the group programme on the outcomes. Finally, there was limited evidence of pharmacological, nursing, social work or spiritual care input as part of any rehabilitation programme among these studies.

4.4. Impact and Outcome Measures for Frailty Rehabilitation Programmes

The heterogenous approach to geriatric rehabilitation was evident given the lack of consensus on the outcome measures used to identify the impact of the frailty rehabilitation programmes in the studies reviewed (Chang et al. 2010; Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann 2017; Niemelä, Leinonen, and Laukkanen 2011). While the studies all acknowledged older frail people benefitted from attending the rehabilitation programmes regarding improvement in functional capacity and physical performance, there was a plethora of different outcomes measured including mortality, rehospitalisation, emergency department visits following the rehabilitation programme, admission to long‐term care facilities, living at home and the need for home help services. Given only Kool, Oesch, and Bachmann (2017) specifically reported when the outcome measures were conducted, it is relatively unknown when the outcomes of the various programmes were measured or whether the benefits from the programmes decreased over time. It is indeterminate whether the frailty intervention programmes had any beneficial impact on the psychological or social perspective of the participants or their families.

5. Discussion

This scoping review was conducted to ascertain the extent of multidisciplinary inpatient frailty rehabilitation programmes available for older people. Despite an extensive and comprehensive search strategy, it is evident there is limited research investigating frailty rehabilitation programmes for older people internationally. Explanations for this finding could be similar programmes to the CRU programme are not available, or similar programmes are available; however, the outcomes are not measured or reported in the literature. Abdi et al. (2019) highlight many services and care delivery models or interventions are not based on the needs of older living with frailty. The importance of developing strategies for integrated care supporting frail older people so they can access and receive the right combination of services, in the right place, at the right time is crucial to enable them to remain living in their homes (Roe et al. 2017). Consequently, there is a need for further research to identify rehabilitation interventions clearly addressing the needs of frail older people.

All the included articles reported the use of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) on admission prior to the programme starting; however, it was not clear whether a universal CGA was used. Given a CGA is an internationally established method to assess the physical, psychological and functional capability of older people and is recommended to be closely linked to interventions (Clegg et al. 2013), there was an inconsistency in the measurement and reporting of outcomes. In addition, there is little or no evidence whether the impact of the relevant programme was beneficial to the participants particularly over a period because no data was gathered. Furthermore, there is no evidence as to whether the frailty rehabilitation programmes are cost effective as this was not measured or reported in the literature. These knowledge gaps clearly indicate further research is needed to ascertain the long‐term benefit on frail older people and the cost effectiveness of providing such intervention programmes.

Each of the studies included in the review conducted a CGA from a multidisciplinary team perspective, yet none reported on any psychological, social, cognitive or spiritual intervention or measured such outcomes. In addition, it was evident the physical and physiotherapy assessment while fundamentally important was the exclusive focus of most of programmes reported. There was an absence or limited measuring of outcomes examining quality‐of‐life and psychological well‐being, especially as older people can experience emotional and psychological difficulties caused or exacerbated by multimorbidity and frailty (Abdi et al. 2019). Following the CGA, a person‐centred programme incorporating supports to address these difficulties along with other therapies could be beneficial with better outcomes for frail older people.

The heterogenous nature of studies investigating rehabilitation programmes for older people was evident throughout our extensive literature search. In particular, the term frail remains ill‐defined and is not a universally agreed term given many studies did not report how they measured frailty (King et al. 2021). While our inclusion criteria were refined iteratively, and the term frailty was included to capture more specific studies this may have led to studies being excluded if the term ‘frail’ was missing from the title, abstract or keywords. Additionally, given our search was limited from 2010 to 2022, it was noteworthy King et al. (2021) concluded there have been no major clinical trials involving frail older inpatients during the last decade. Furthermore, only studies published in the English language were included thus reported inpatient rehabilitation programmes not reported in English were excluded.

This scoping review identified the multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation programmes available for frail older people reported in the peer‐reviewed and grey literature. The findings demonstrate some similarities to the CRU programme established in XXX; although the findings from our scoping review made visible the paucity of research focusing on frailty rehabilitation programmes internationally and the limited research available on their outcomes. In essence, from this review there was a dearth of evidence, indicating a need for further research into rehabilitation programmes for frail older people who wish to continue to live well in the community.

6. Conclusion

Frailty intervention programmes like the CRU model established in XXX promote healthy ageing and can reduce the risk of deterioration from frailty syndromes and reduced physical functioning. However, there is a paucity of studies identifying inpatient multidisciplinary programmes to support frail older people to remain living at home. While this may be a result of limited research another potential cause may be insufficient awareness of CRU as a model. That said, further research is needed to establish the most effective person centred, cost effective and multidisciplinary intervention programme suitable for the well‐being of older people living with frailty. From the evidence reviewed, any programme adopted should be empirically evaluated ensuring the outcomes measured align closely with both the intervention adopted and the identified individual needs of the person.

7. Implications for Practice

Multidisciplinary inpatient intervention programmes are beneficial for frail older people and should be continued with a particular focus on mobility. However, to date it is not possible to make further recommendations in practice as there is a gap in the literature systematically evaluating person‐centred interventions. Extensive research needs to be conducted to address this significant gap in knowledge.

8. Patient and Public Involvement

This project was a scoping of the literature; therefore, no patient or public contribution was necessary.

Author Contributions

M.C. and M.B. conceived the study. M.C. and M.B. developed the study design. M.C., M.M. M.B. and F.L. created the proposed search strategy. M.M. and F.L. conducted literature search. M.M. and M.B. completed title and abstract screening, full‐text screen and data extraction. M.C. and A.D. resolved any conflicts. M.M. and M.B. drafted the review manuscript. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by IReL.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable—no new data generated.

References

- Abdi, S. , Spann A., Borilovic J., de Witte L., and Hawley M.. 2019. “Understanding the Care and Support Needs of Older People: A Scoping Review and Categorisation Using the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Framework (ICF).” BMC Geriatrics 19, no. 1: 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , and O'Malley L.. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8, no. 1: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.‐H. , Tsai S. L., Chen C. Y., and Liu W. J.. 2010. “Outcomes of Hospitalized Elderly Patients With Geriatric Syndrome: Report of a Community Hospital Reform Plan in Taiwan.” Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 50, no. Suppl 1: S30–S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, A. , Young J., Iliffe S., Rikkert M. O., and Rockwood K.. 2013. “Frailty in Elderly People.” Lancet 381, no. 9868: 752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley, A. , Goldberg S. E., Gordon A. L., and Logan P. A.. 2021. “Rehabilitation Potential in Older People Living With Frailty: A Systematic Mapping Review.” BMC Geriatrics 21, no. 1: 533. 10.1186/s12877-021-02498-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grund, S. , van Wijngaarden J. P., Gordon A. L., Schols J. M. G. A., and Bauer J. M.. 2020. “EuGMS Survey on Structures of Geriatric Rehabilitation Across Europe.” European Geriatric Medicine 11, no. 2: 217–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guasti, L. , Dilaveris P., Mamas M. A., et al. 2022. “Digital Health in Older Adults for the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Diseases and Frailty. A Clinical Consensus Statement From the ESC Council for Cardiology Practice/Taskforce on Geriatric Cardiology, the ESC Digital Health Committee and the ESC Working Group on e‐Cardiology.” ESC Heart Failure 9, no. 5: 2808–2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guigoz, Y. , Vellas B., and Garry P. J.. 1996. “Assessing the Nutritional Status of the Elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as Part of the Geriatric Evaluation.” Nutrition Reviews 54, no. 1 Pt 2: S59–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Dening, K. 2021. “Frailty Leads to Higher Mortality and Hospital Use.” Evidence Based Nursing 24, no. 1: 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuberger, R. A. 2011. “The Frailty Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics 30, no. 4: 315–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley, A. L. , Johnson R., Purdy S., Valderas J. M., and Salisbury C.. 2012. “Measures of Multimorbidity and Morbidity Burden for Use in Primary Care and Community Settings: A Systematic Review and Guide.” Annals of Family Medicine 10, no. 2: 134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, S. J. , Raine K. A., Peel N. M., and Hubbard R. E.. 2021. “Interventions for Frail Older Inpatients: A Systematic Review of Frailty Measures and Reported Outcomes in Randomised Controlled Trials.” Australasian Journal on Ageing 40, no. 2: 129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, G. 2017. “Frailty as a Predictor of Disabilities Among Community‐Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” Disability and Rehabilitation 39, no. 19: 1897–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool, J. , Oesch P., and Bachmann S.. 2017. “Predictors for Living at Home After Geriatric Inpatient Rehabilitation: A Prospective Cohort Study.” Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 49, no. 2: 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D. , Colquhoun H., and O'Brien K. K.. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5, no. 1: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä, K. , Leinonen R., and Laukkanen P.. 2011. “The Effect of Geriatric Rehabilitation on Physical Performance and Pain in Men and Women.” Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 52, no. 3: e129–e133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2020. The Territorial Impact of COVID‐19: Managing the Crisis Across Levels of Government. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy‐responses/the‐territorial‐impact‐of‐covid‐19‐managing‐the‐crisis‐across‐levels‐of‐government‐d3e314e1/. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews.” PLoS Medicine 18, no. 3: e1003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S. G. , McCue P., Phelps K., et al. 2018. “What Is Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)? An Umbrella Review.” Age and Ageing 47, no. 1: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J. , Godfrey C., McInerney P., Munn Z., Tricco A. C., and Khalil H.. 2020a. “Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version).” In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J. , Marnie C., Tricco A. C., et al. 2020b. “Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews.” JBI Evidence Synthesis 18: 2119–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo, D. , and Richardson S.. 1991. “The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 39, no. 2: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, D. , Guasti L., Walker D., et al. 2022. “Frailty in Cardiology: Definition, Assessment and Clinical Implications for General Cardiology. A Consensus Document of the Council for Cardiology Practice (CCP), Association for Acute Cardio Vascular Care (ACVC), Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), council on Valvular Heart Diseases (VHD), council on Hypertension (CHT), Council of Cardio‐Oncology (CCO), working Group (WG) Aorta and Peripheral Vascular Diseases, WG e‐Cardiology, WG Thrombosis, of the European Society of Cardiology, European Primary Care Cardiology Society (EPCCS).” European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 29, no. 1: 216–227. 10.1093/eurjpc/zwaa167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe, L. , Normand C., Wren M. A., Browne J., and O'Halloran A. M.. 2017. “The Impact of Frailty on Healthcare Utilisation in Ireland: Evidence From the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing.” BMC Geriatrics 17, no. 1: 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, D. , Elliott M., Rubenstein L. Z., et al. 2001. “The Vulnerable Elders Survey: A Tool for Identifying Vulnerable Older People in the Community.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49, no. 12: 1691–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumacher, E. , Sattar S., Neve M., et al. 2018. “Use of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and Geriatric Screening for Older Adults in the Radiation Oncology Setting: A Systematic Review.” Clinical Oncology 30, no. 9: 578–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. 2016. “A Scoping Review on the Conduct and Reporting of Scoping Reviews.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 16: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169, no. 7: 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2018. Ageing and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/ageing‐and‐health. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2023. “Rehabilitation.” https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/rehabilitation.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable—no new data generated.