Abstract

Objective

To measure the plasma levels of human cartilage intermediate layer protein 1 (CILP1) in patients with diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), and to investigate its association with the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in DCM.

Methods

A total of 336 diabetic patients were enrolled and assigned into two groups based on the presence or absence of DCM (DCM group and N-DCM group). The baseline clinical data including glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (ALT), glutamic oxaloacetic acid transferase (AST), albumin, serum creatinine, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), C-reactive protein (CRP), and N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) were recorded. Subsequently, plasma levels of CILP1 at admission were detected by the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method. Echocardiographic parameters were also acquired for all patients. The association of CILP1 with LVEF, LVDD and CRP was determined. In addition, the occurrence of MACE was examined during the 12-month follow-up in the DCM group.

Results

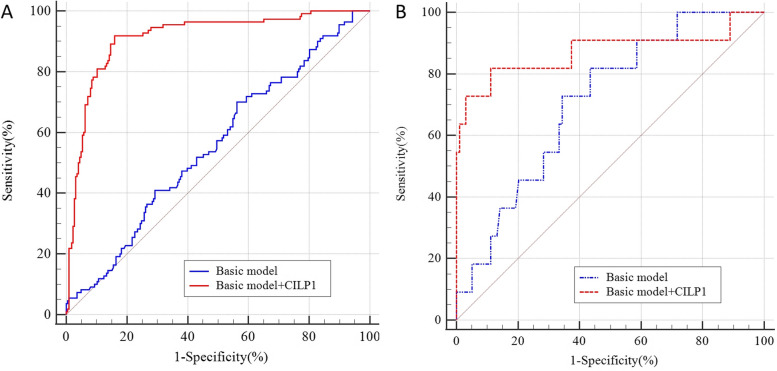

The concentration of CILP1 in the DCM group was higher than in the N-DCM group [1329.97 (1157.14, 1494.36) ng/L vs. 789.00 (665.75, 937.06) ng/L, P < 0.05], higher in the MACE group than in the non-MACE group [1777.23 (1532.83, 2341.26)ng/L vs. 885.00 (722.40, 1224.91) ng/L, P < 0.05). Correlation analysis revealed that CILP1 expression was associated with LVEF, CRP and LVDD (r = -0.58, 0.29 and 0.44, respectively, P < 0.05). Analysis of a nomogram demonstrated that CILP1, sex, age, BMI, LVEF and LVDD could predict the occurrence of MACE in DCM patients at 12 months (P < 0.05). The plasma levels of CILP1 were independently associated with a stronger discriminating power for DCM. Furthermore, inclusion of CILP1 as a covariate in the model caused a significant improvement in risk estimation compared with traditional risk factors for DCM [BASIC: AUC: 0.556, 95%CI: 0.501–0.610; BASIC + CILP1: AUC: 0.913, 95%CI: 0.877–0.941, P < 0.05] and MACE [BASIC: AUC: 0.710, 95%CI: 0.616–0.792; BASIC + CILP1: AUC: 0.871, 95%CI: 0.794–0.928, P < 0.05].

Conclusions

The serum concentration of CILP1 was increased in DCM patients. Elevated fasting plasma CILP1 levels was a robust diagnostic marker of DCM and was independently associated with an increased risk of MACE.

Keywords: Cartilage intermediate layer protein 1, Diabetic cardiomyopathy

Introduction

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is described as cardiomyopathy occurring in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) in the absence of conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as coronary artery diseases, valvular diseases, and hypertension 0. Studies have shown that the prevalence of DM in heart failure (HF) may exceed 30%, while in patients with T1DM and T2DM, the prevalence of HF is approximately 14.5% and 35.0%, respectively [1–3]. The pathophysiological progression of DCM is characterized by diffuse myocardial fibrosis, dysfunctional cardiac remodeling, accompanied with diastolic dysfunction, cardiac hypertrophy, diabetic microangiopathy 0, and some studies have shown that myocardial injury induced by excessive inflammation/oxidative stress pathways, and changes in heart receptors may affect systolic and diastolic function [4], leading to HF, increasing the morbidity and mortality of patients with DM.

Most patients with DCM are asymptomatic during the early stage. This underscores that need to perform screening of DCM patients in the early stages to identify those at risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Numerous cardiovascular biomarkers such as BNP, cardiac troponins and MMPs have been showed to be associated with LV dysfunction in patients with DM [5], and important pathophysiological processes of DCM have been uncovered in recent years. Evidence from other investigations has indicated that CRP and ST2 are subclinical indicators of cardiac remodeling and poor clinical outcomes. Notably, metabolic disorders in diabetes may contribute to the elevation of human myocardial cell SGLT2 level. The SGLT-2i inhibitor has been shown to improve ventricular muscle remodeling in HF patients including those with diabetes cardiomyopathy while also maintaining blood glucose [6, 7]. However, the impact of these indicators on the occurrence of MACE in patients with DCM is not well understood. The available cardiac biomarkers for DCM are not specific and do not predict the prognostic outcomes of DCM effectively [8].

Cartilage intermediate layer protein 1 (CILP1), a secreted glycoprotein found in the extracellular matrix, originates from chondrocytes in articular cartilage [9] and participates in cartilage scaffolding and occurrence of cartilage disorders. CILP1 is a large glycoprotein. It can be secreted in full length or as distinct N- and C-terminal polypeptides after cleavage. The N-terminal half can directly bind to transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) via the thrombospondin type 1 domain, while the C-terminal half serves as a nucleotide pyrophosphohydrolase (NTPPHase) [10]. In recent years, studies have shown that elevated CILP1 is associated with cardiac tissues infarction and with ventricular remodeling after MI, transaortic constriction (TAC), or AngII (angiotensin II) treatment [11–13]. CILP1 decreases cardiac fibrosis by blocking the TGF-β1 signaling pathway through its N- and C- terminal fragment [12]. However, whether CILP1 is contributes to the DCM progression and affects the prognosis of DCM patients has not been reported.

Therefore, we examined the levels of CILP1 in patients with DCM and assesses the impact of CILP1 on cardiac fibrosis, remodeling and prognosis of DCM patients.

Methods

Participants and clinical characteristics

Patients diagnosed as diabetes mellitus (DM) according to the guidelines [14] and admitted to the Cardiology Department in our hospital were enrolled in the study from June 2019 to June 2021. The inclusion criteria were: 1. Patients diagnosed with diabetes cardiomyopathy; 2. Age ≥ 30 and ≤ 75 years old; 3. Received laboratory tests, echocardiography, coronary CTA or coronary angiography to confirm the diagnosis; 4. Gave consent to participate in the study; 5. Patients who completed a follow-up. Exclusion criteria included: 1. Patients with coronary artery stenosis exceeding 50%, or acute and old myocardial infarction; 2. Patients with a history of coronary stent implantation or coronary artery bypass surgery; 3. Patients who received permanent pacemaker implantation surgery (including ICD) in the past; 4. Those with other cardiomyopathies including ischemic cardiomyopathy, valvular heart diseases, congenital heart diseases, hypertensive heart disease, chronic myocarditis, stress-induced cardiomyopathy and uremic cardiomyopathy; 5. Patients with complete atrioventricular block and bundle branch block; 6. Patients with life-threatening bleeding; 7. Malignant tumor patients; 8. With severe infections; 9. With liver and kidney dysfunction; 10. Patients with myocarditis and pericarditis; 11. Patients who refused to participate in the study.

Although there is no universally accepted definition of diabetic cardiomyopathy [15], most studies concur that DCM is a cardiac dysfunction associated with DM in the absence causes of coronary artery diseases, uncontrolled hypertension, significant valvular heart diseases, and congenital heart diseases [15]. Diabetic patients exhibit progressive deterioration of cardiac function, from subclinical phase to systolic dysfunction, accompanied by symptomatic heart failure. In the study, DCM was diagnosed after ruling out the existence of ischemic cardiomyopathy, valvular heart diseases, congenital heart diseases, hypertensive heart disease, chronic myocarditis, stress-induced cardiomyopathy and uremic cardiomyopathy, among others. Patients classified as DCM stage 2–4 based on the criteria proposed by Maisch et al. [16], who presented with NYHA class II-IV symptoms such as chest tightness, palpitations, shortness of breath, and dyspnea, were included in the DCM group. These patients exhibited left ventricular enlargement (left ventricular end-diastolic diameter ≥ 55 mm in males and ≥ 50 mm in females), reduced wall motion, and decreased systolic function with a left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 50%, as determined by echocardiography. Additionally, coronary artery stenosis was ≤ 50%. In contrast, DM patients without these conditions were assigned to the N-DCM group. General characteristics, including past medical histories such as smoking, drinking, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension, were recorded for all participants.

Medications

All participants received conventional glucose-lowering treatment and necessary medical treatment such as diuretics, β-blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor antagonist (ACEI/ARB/ARNI), spironolactone, and other necessary drugs following the current clinical guidelines.

Blood tests

Fasting blood samples were collected in the next morning after admission to the hospital to measure the concentrations of variables such as glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (ALT), glutamic oxaloacetic acid transferase (AST), albumin, serum creatinine, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), C-reactive protein (CRP), and N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). In addition, the concentration of plasma levels of CILP1 at admission was determined by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Echocardiography analysis

All admitted participants received echocardiographic examination while in stable condition during hospitalization. The examination was performed twice and the average value was calculated following the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography [17]. Echocardiographic items were recorded by experienced physicians using the Vivid 7 (GE, USA), examining the standard left ventricular long axis, short axis and apical four-chamber heart, five-chamber heart and other sections were examined simultaneously. The required images were displayed and accurate measurements of the indicators including left atrial diameter (LAD), left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (LVDD), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), mitral regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation, and aortic regurgitation, were conducted.

The left ventricular end-diastolic diameter and the left atrial anterior–posterior diameter were measured on the long axis of the left ventricle adjacent to the sternum, recorded as LVDD and LAD, respectively. The LVEF was measured using the two-dimensional biplane method with four- and two-chamber views at the apex of the heart to evaluate left ventricular systolic function. LVEF ≤ 50% was defined as decreased left ventricular systolic function. Cardiac remodeling was defined as LVDD ≥ 55 mm in males and ≥ 50 mm in females, and (or) LVEF ≤ 50%. In the apical four chamber view, the tissue Doppler sampling volume was placed at the level of the mitral valve annulus on the side wall, and the mitral valve annulus motion displacement was recorded. An e value less than a indicated decreased left ventricular diastolic function.

Follow-up

Patients with DCM were followed up for at least 12 months. During the follow-up, DCM patients were screened for MACE (consisting of myocardial infarction and re-infarction, sudden cardiac arrest, and re-hospitalization for heart failure or other cardiovascular diseases). The follow-up was conducted through telephone, outpatient visits, and inpatient consultations. The initial time of follow-up was defined as the day after discharge, and the end point of the follow-up was the first onset of MACE events, or the end date of follow-up. The follow-up time was presented in months.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS22.0, Graphpad Prism 9, Medcalc and R software. Qualitative data were expressed as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were presented as a median and inter-quartile range. Pearson’s χ2 tests and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare multivariate comparisons of continuous and categorical variables between DCM group and N-DCM group. Correlation analysis was performed to determine the association of plasma levels of CILP1 with echocardiography data and CRP. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was plotted to measure the predictive values of variables on DCM and identify MACE events. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The trial was approved by the ethics committee of our institution. All patients provided written informed consent. (JD-LK-2021–029-02, review).

Results

A total of 336 participants were enrolled in the study, with 226 in the N-DCM group and 110 in the DCM group. During follow-up MACE occurred in 11 patients in the DCM group, with 4 cases of HF or other cardiovascular diseases, 5 cases of myocardial infarction, and 2 cases of death from cardiac shock.

Clinical characteristics, blood tests and echocardiography data

Table 1 shows the baseline information of the study subjects including clinical characteristics, blood tests, echocardiography data. Most of the clinical characteristics were not significantly different among the groups except for smoking, coronary atherosclerosis and AF, while medications including dapagliflozin, ACEI/ARB/ARNI, β-blockers and aldosterone antagonists were frequently required in the DCM group (P < 0.05). Among DCM patients, the concentration of NT-ProBNP, HbA1c and CRP was increased. In contrast, lower LVEF levels, elevated LVDD, pulmonary artery pressure, and proportion of valvular regurgitation were detected in patients with diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Table 1.

General information of the two groups

| Variables | DCM (n = 110) | N-DCM (n = 226) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Sex (Male,%) | 97(88.18) | 151(66.81) | 0.97 |

| Age (years) | 67.00[58.00, 73.00] | 65.00[56.00, 74.00] | 0.89 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26[22, 28] | 26 [22, 29] | 0.41 |

| HBP (%) | 25(22.72) | 51(22.57) | 0.97 |

| HL (%) | 50(45.45) | 91(40.27) | 0.37 |

| Coronary atherosclerosis(%) | 63(57.27) | 69(30.53) | < 0.05 |

| Smoking (%) | 17(15.45) | 33(14.60) | < 0.05 |

| Drinking (%) | 13(11.82) | 21(9.29) | 0.85 |

| AF (%) | 13(11.82) | 8(3.53) | < 0.05 |

| Blood tests | |||

| Hb (g/L) | 133.00[120.00, 144.00] | 128.00[118.75, 140.00] | 0.39 |

| Cr (umol/L) | 75.00[59.75, 88.00] | 73.00[64.00, 89.00] | 0.38 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.41[3.69, 5.27] | 4.12[3.77, 4.98] | 0.86 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.51[1.88, 3.36] | 2.55[2.09, 3.32] | 0.12 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.08[0.88, 1.38] | 1.06[0.87, 1.32] | 0.22 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.17[0.87,1.65] | 1.42[1.01, 1.95] | 0.16 |

| NT-ProBNP (pg/ml) | 745.00[202.25,1798.50] | 279.00[98.00,857.50] | < 0.05 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 6.20[5.60,7.33] | 5.50[4.40,5.83] | < 0.05 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.40[5.90,6.78] | 5.00[4.40,5.50] | < 0.05 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 18.00[14.00,22.00] | 11.00[7.00,16.25] | < 0.05 |

| Medications | |||

| ACEI/ARB/ARNI | 80(72.72) | 40(17.70) | < 0.05 |

| β blockers | 95(86.36) | 43(19.03) | < 0.05 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 103(93.63) | 2(0.89) | < 0.05 |

| Dapagliflozin | 96(87.27) | 12(5.30) | < 0.05 |

| Echocardiography data | |||

| LVEF (mm) | 42.00[37.00,46.00] | 64.50[60.00,69.00] | < 0.05 |

| LVDD (mm) | 55.00[52.00,58.00] | 47.00[44.99,50.00] | < 0.05 |

| LAD (mm) | 34.00[32.00,37.00] | 32.00[30.00,34.00] | < 0.05 |

| Pulmonary artery pressure (mmHg) | 33[30, 37] | 26[22.30] | < 0.05 |

| Decreased diastolic function (n,%) | 68(61.82) | 92(40.71) | < 0.05 |

| MVR (moderate or severe) | 42(38.18) | 24(10.62) | < 0.05 |

| TR (moderate or severe) | 43(39.09) | 39(17.26) | < 0.05 |

| AR (moderate or severe) | 26(23.64) | 18(8.00) | < 0.05 |

Abbreviations: HL Hyperlipidemia, AF atrial fibrillation, TC total cholesterol, LDL-C low density lipoprotein, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein, TG triglyceride, NT-ProBNP N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide, FBG fasting blood glucose, ACEI/ARB angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor antagonist, LAD left atrial diameter, LVDD left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, MVR mitral regurgitation, TR tricuspid regurgitation, AR aortic regurgitation

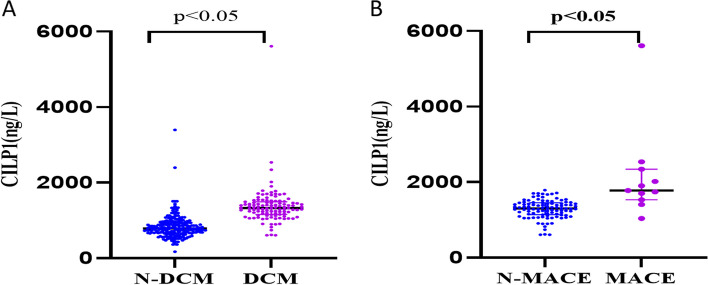

CILP1 protein expression

Comparison of CILP1 protein expression levels between the two groups revealed that the CILP1 protein was markedly higher in patients with DCM [1329.97 (1157.14, 1494.36) ng/L vs. 789.00 (665.75, 937.06) ng/L, P < 0.05] (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the levels of CILP1 were significantly higher among DCM patients who developed MACE in 1-year follow-up [1777.23 (1532.83, 2341.26) ng/L vs. 885.00 (722.40, 1224.91) ng/L, P < 0.05] (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

A Comparison of CILP1 protein levels between the N-DCM and DCM groups. B Comparison of CILP1 protein expression between MACE and N-MACE patients

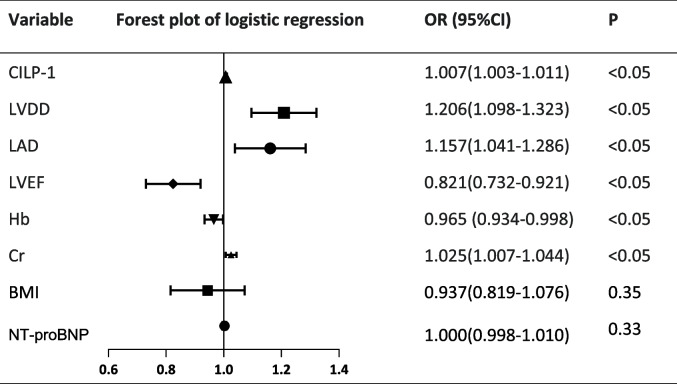

Uni-variate regression analysis for MACE and correlation analysis

In the univariate regression analysis, Cr, Hb, LVEF, LAD and LVDD were found to be significant predictors of MACE in DCM patients, with hazard ratios of 1.025, 0.965, 0.821, 1.157 and 1.206, respectively. Moreover, elevated plasma levels of CILP1 remained a significantly strong predictor of MACE (Table 2). A graded increase in the risk was recorded when the levels of CILP1 were analyzed as a continuous variable (unadjusted hazard ratio, 1.007, 95% CI: 1.003–1.011, P < 0.05). However, there was no significant different in NT-ProBNP and BMI (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of MACE in patients with DCM

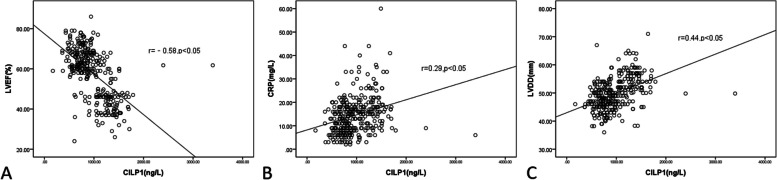

Correlation analysis revealed significant association of plasma levels of CILP1 with the LVEF (Spearman’s r = -0.58, P < 0.05), CRP (Spearman’s r = 0.29, P < 0.05) and LVDD (Spearman’s r = 0.44, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A, B, C). However, no correlation was found between NT ProBNP and CILP1 (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Y axis represents LVEF, CRP or LVDD and X axis denotes CILP1 concentrations. Correlation analyses between CILP1 and LVEF (A), CRP (B) as well as LVDD (C)

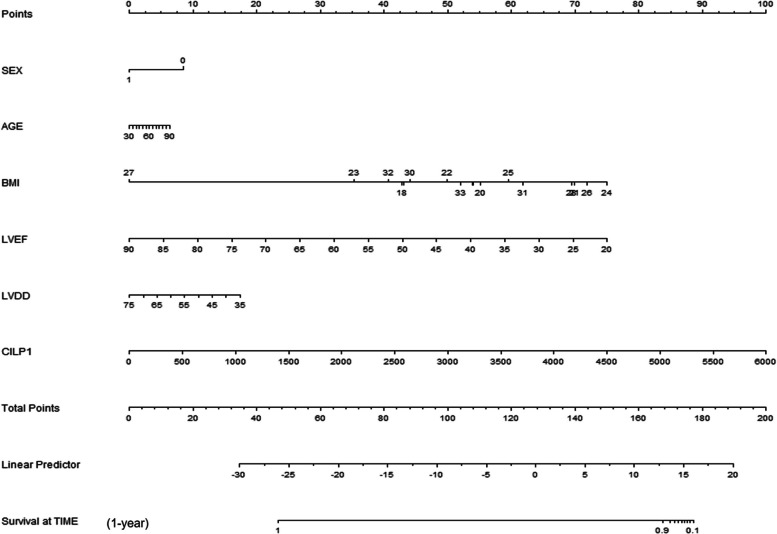

Nomogram construction

Interestingly, univariate analysis revealed significant association of LVEF, LVDD and CILP1 with the occurrence of MACE. These variables were used to construct a nomogram that included 6 risk factors: sex, age, BMI, LVEF, LVDD, CILP1 (Fig. 3). The total score was generated to predicted 1-year MACE for DCM patients by adding all scores based on these clinical variables. The results demonstrated that CILP1 concentration was a valuable factor to evaluate the prognosis in patients with DCM.

Fig. 3.

A constructed nomogram for predicting the prognosis of a patient with MACE

Clinical value of CILP1 for DCM and MACE

After adjusting for traditional risk factors (sex, age, BMI, HBP, HL, smoking, drinking) and other baseline covariates, the receiver-operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis indicated that CILP1 could independently diagnose DCM (BASIC: AUC: 0.556, 95%CI: 0.501–0.610, BASIC + CILP1, AUC: 0.913, 95%CI:0.877–0.941) (Fig. 4(A). Moreover, CILP1 could predict the outcomes of DCM as shown in Fig. 4(B). The inclusion of CILP1 as a covariate resulted in a significant improvement in risk estimation compared with traditional risk factors for MACE (BASIC: AUC: 0.710, 95%CI: 0.616–0.792, BASIC + CILP1, AUC: 0.871, 95%CI: 0.794–0.928).

Fig. 4.

The receiver-operating characteristic curve (ROC) for CILP1 in predicting the DCM and the MACE events. Basic model including sex, age, BMI, HBP, HL, smoking, drinking

Discussion

The high incidence of diabetes and its associated vascular complications has become a major public health problem. In this study, the use of quadruple therapy (ACEI/ARB/ARNI,β blockers, Aldosterone antagonistsDap and agliflozin) for heart failure management was more common in DCM patients than in non-DCM patients. Research has shown that ARNI is an anti-remodeling drug for HF patients which can induce cardiac remodeling. However, the incidence of MACE in DCM patients in this study reached 10%. This underscores the need to screen for high-risk patients who are prone to developing DCM as early as possible [18]. However, there are no robust diagnostic biomarkers of DCM. In this study, we investigated, for the first time, the concentration of CILP1 protein in DCM patients, and explored its association with echocardiographic parameters, as well as its potential to predict the diagnosis and prognosis of DCM patients.

The results showed that CILP-1 expression was up-regulated in stage 2–4 of diabetic cardiomyopathy, and it was strongly correlated with LVEF, LVDD and CRP. Moreover, fasting plasma CILP1 levels could predict the risk of incident MACE in DCM patients independently of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and the presence of coronary stenosis. Including CILP1 as a covariate significantly enhanced the accuracy of risk prediction for MACE, surpassing traditional risk factors.

The pathophysiological mechanism of DCM is complex and includes many factors and pathways, with cardiac fibrosis being a common factor [6]. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)–S6 kinase1 (S6K1) pathway has strongly been linked to the pathogenesis of DCM, with increased S6K1 phosphorylation in DCM patients found to cause abnormal activation of the RAAS and insulin resistance in heart. It also disrupts phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling and activation of protein kinase B (Akt) [19, 20]. For instance, aberrant PI3K/Akt signaling has been shown to decrease glucose uptake and intracellular calcium overload. Studies have reported that impaired PI3K/Akt signaling pathway suppresses endothelial nitric oxide synthase and NO production in coronary endotheliocyte, which promotes cell apoptosis due to Ca2+ overload and enhances coronary vasodilation, imbalances energy homeostasis and myocardial substrate flexibility [21]. Additionally, insulin resistance triggers myocardial damage, hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis by disrupting the function of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [22], which is accompanied by inflammatory gene expression, AGEs deposition, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and cardiac cells apoptosis. Furthermore, several studies have confirmed diffuse extracellular matrix (ECM) and collagen deposition in diabetic patients [23, 24], which are driven by increased TGFβ1 activity, alteration of collagen degrading matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) activity, and the structural features of myocardial tissues [25, 26]. CILP1 plays a significant role in modulating the TGF-β signaling pathway, with its larger N-terminal fragment, shorter C-terminal fragment, and full-length protein all capable of influencing this pathway. Notably, the N-terminal fragment and full-length CILP1 can bind to TGF-β via the shared thrombospondin-1 domain [27]. Pathophysiological changes in the ECM, particularly involving CILP1, are implicated in irreversible myocardial fibrosis. This fibrosis contributes to the development and progression of DCM, ultimately leading to poor clinical outcomes [28, 29]. CILP1 can increase ECM generation in diabetes patients by interfering with TGF-βsignal transduction and inducing myocardial fibrosis, suggesting that it may influence the occurrence and prognosis of DCM.

It has been shown that CILP1 is a promising biomarker of cardiac fibrosis [27]. Early research demonstrated that CILP1 was expressed in human heart, and correlated strongly with ECM proteins, especially in myocardial infarction tissues of mice [11]. Circulating levels of full-length CILP1 have been reported to decrease in patients with heart failure; however, its expression was found to be abundant in fibrotic myocardial tissue, indicating its specificity for fibrotic regions [30]. This sensitivity to changes in the ECM positions CILP1 as a promising marker for cardiac fibrosis. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated elevated CILP1 concentrations in mice with left ventricular hypertrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy compared to controls. The study further confirmed that CILP1 is associated with both right and left ventricular remodeling, right ventricular maladaptation, and ventriculoarterial uncoupling in patients with pulmonary hypertension [31]. This study also found that CILP1 was elevated in patients with diabetes cardiomyopathy and positively correlated with cardiac enlargement, but negatively correlated with cardiac systolic function. This implies that CILP1 may be involved in the development of cardiac fibrosis.

A variety of mechanisms have been proposed for myocardial stiffness, which results in the loss of cardiac function leading to HF. Regan TJ etc. found that collagen accumulated in the all layers of the ventricular myocardium, causing LV remodeling, perivascular and interstitial fibrosis [32]. Changes in the morphology of ECM have been linked to the development of myocardial dysfunction and impaired ventricular compliance [28]. The expression of CILP1 is highly associated with ECM genes and involved in TGFβ signaling in human cardiac tissue. Furthermore, increased fatty acids utilization and impaired mitochondrial structure contribute to cardiac dysfunction [33]. A previous study found that hyperglycaemia-induced oxidative stress caused DNA damage and apoptosis of myocardial cells, independently increasing the risk of HF [28]. This suggests that CILP1 increases fatty acid utilization and mitochondrial structural damage by inducing oxidative stress and DNA loss, thereby influencing the occurrence and prognosis of DCM.

In this study, we found elevated plasma levels of CRP in DCM patients, which correlated with CILP1. CRP is regarded as acute phase reaction protein that activates inflammation, causes cells lysis and apoptosis. Research had demonstrated that excessive inflammation may worsen the prognosis of heart diseases [34]. Another research showed that CRP levels were up-regulated in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes [35]. Overactivation of inflammation was also detected in Type 2 diabetes and its complications [36]. Overexpression of CRP accelerates the progression of diabetic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular remodeling, deteriorating systolic and diastolic LV function in diabetic cardiomyopathy, by stimulating angiotensinogen, oxidative stress, cardiac apoptosis, and fibrosis [36]. These findings show that CILP1 is involved in the chronic inflammatory response during diabetic cardiomyopathy.

This study found elevated plasma levels of CILP1 in patients with DCM, suggesting that it may be a prognostic biomarker for cardiovascular events in patients with DCM. However, there are certain limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the analysis was based on a small simple size, with few endpoints. Therefore, these present results need to be further verified on a larger cohort of patients. Secondly, it remains unknown how external conditions such as newly approved drugs correlate with the long-term prognosis of DCM patients. Lastly, the follow-up was not long enough, and thus, further studies are warranted to validate our findings.

Conclusions

In summary, elevated plasma CILP1 was detected in DCM patients. The analysis revealed that CILP1 was not only a predictor of MACE, but also influenced the progression of DCM in terms of cardiac remodeling. This suggests that it may be a potential therapeutic target.

Moreover, elevated levels of CILP1 in DCM patients could predict the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events.

Future prospects

During the formation of DCM, CILP levels varies across different stage. Therefore, in light of the current findings, we plan to continue enrolling diabetic patients and monitor their progress over time. Based on their echocardiographic findings, we will categorize them into subgroups for further analysis. This approach aims to identify high-risk groups for DCM early through CILP level measurement, potentially improving long-term patient outcomes through timely intervention.

Authors' contributions

LX and ZQ contributed to the study design. LX contributed to the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results, as well as writing the manuscript. XL and XJ was involved in data acquisition and research. LX and XL participated in project discussions. LX and ZQ are the guarantor of this work and had full access to all the data in the study, taking responsibility for data integrity and accuracy of analysis.

Funding

The project was supported by the Guiding Project of Suzhou Science and Technology Development Plan (SKYXD2022048, SYSD2020203 and SLT2023203), the Development Fund of Xuzhou Medical University Affiliated Hospital (XYFZ202202) and Natural lipid-regulating drugs evidence-based research fund project (2023-CCA-NLD-348).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

All the patients provided written informed consent (JD-LK-2021–029-02, review).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li Xiang and Xiang Liu contributed equally to this article.

Contributor Information

Li Xiang, Email: 1229299337@qq.com.

Zhenguo Qiao, Email: qzg66666666@163.com.

References

- 1.Ma X, Mei S, Wuyun Q, Zhou L, Sun D, Yan J. Epigenetics in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Clin. Epigenetics. 2024;16(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JJ. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of heart failure in diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2021;45(2):146–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Triposkiadis F, et al. Diabetes mellitus and heart failure. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):S37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sardu C, et al. Stretch, injury and inflammation markers evaluation to predict clinical outcomes after implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in heart failure patients with metabolic syndrome. Front Physiol. 2018;9:758.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murtaza G, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy - A comprehensive updated review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;62(4):315–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marfella R, et al. Sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors improve cardiac function by reducing JunD expression in human diabetic hearts. Metabolism. 2022;127:154936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marfella R, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) expression in diabetic and non-diabetic failing human cardiomyocytes. Pharmacol Res. 2022;184:106448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumric M, et al. Role of novel biomarkers in diabetic cardiomyopathy. World J Diab. 2021;12(6):685–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang QJ, et al. Matricellular protein Cilp1 promotes myocardial fibrosis in response to myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2021;129(11):1021–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, et al. Prognostic value of cartilage intermediate layer protein 1 in chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9(1):345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Nieuwenhoven FA, et al. Cartilage intermediate layer protein 1 (CILP1): a novel mediator of cardiac extracellular matrix remodelling. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang CL, et al. Cartilage intermediate layer protein-1 alleviates pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis via interfering TGF-beta1 signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;116:135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLellan MA, et al. High-resolution transcriptomic profiling of the heart during chronic stress reveals cellular drivers of cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. Circulation. 2020;142(15):1448–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacks DB, et al. Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Diab Care. 2023;46(10):e151–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paolillo S, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: definition, diagnosis, and therapeutic implications. Heart Fail Clin. 2019;15(3):341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizamtsidi M, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: a clinical entity or a cluster of molecular heart changes? Eur J Clin Invest. 2016;46(11):947–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang RM, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sardu C, et al. Angiotensin receptor/Neprilysin inhibitor effects in CRTd non-responders: from epigenetic to clinical beside. Pharmacol Res. 2022;182:106303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia G, DeMarco VG, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(3):144–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avagimyan A, Fogacci F, Pogosova N, Kakrurskiy L, Kogan E, Urazova O, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: 2023 update by the International Multidisciplinary Board of Experts. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024;49(1 Pt A):102052. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Yi CH, Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Yuan J. Integration of apoptosis and metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:375–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resnikoff HA, Miller CG, Schwarzbauer JE. Implications of fibrotic extracellular matrix in diabetic retinopathy. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2022;247(13):1093–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aykac I, Podesser BK, Kiss A. Reverse remodeling in diabetic cardiomyopathy: the role of extracellular matrix. Minerva Cardiol Angiol. 2022;70(3):385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poteryaeva ON, et al. Changes in activity of matrix metalloproteinases and serum concentrations of proinsulin and C-Peptide depending on the compensation stage of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2018;164(6):730–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asthana P, Wong HLX. Preventing obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes by targeting MT1-MMP. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2024;1870(4): 167081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gross S, Thum T. TGF-beta inhibitor CILP as a novel biomarker for cardiac fibrosis. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5(5):444–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rupee S, Rupee K, Singh RB, Hanoman C, Ismail AMA, Smail M, et al. Diabetes-induced chronic heart failure is due to defects in calcium transporting and regulatory contractile proteins: cellular and molecular evidence. Heart Fail Rev. 2023;28(3):627–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kariya S, et al. Transvenous retrograde thoracic ductography: initial experience with 13 consecutive cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(3):406–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S, et al. Cardiac fibrosis is associated with decreased circulating levels of full-length CILP in heart failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5(5):432–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keranov S, et al. CILP1 as a biomarker for right ventricular maladaptation in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(4):1901192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regan TJ, et al. Myocardial composition and function in diabetes. The effects of chronic insulin use. Circ Res. 1981;49(6):1268–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berthiaume JM, et al. Mitochondrial NAD(+)/NADH redox state and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2019;30(3):375–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Codner E, et al. C-Reactive protein and insulin growth factor 1 serum levels during the menstrual cycle in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes. Diab Med. 2016;33(1):70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sardu C, et al. Inflammatory related cardiovascular diseases: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(22):2565–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, et al. Gypenosides improve diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting ROS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(9):4437–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mano Y, et al. Overexpression of human C-reactive protein exacerbates left ventricular remodeling in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2011;75(7):1717–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.