Abstract

The Jumonji C (JmjC) structural domain-containing gene family plays essential roles in stress responses. However, descriptions of this family in Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis (Chinese cabbage) are still scarce. In this study, we identified 29 members of the BrJMJ gene family, with cis-acting elements related to light, low temperature, anaerobic conditions, and phytohormone responses. Most BrJMJs were highly expressed in the siliques and flowers, suggesting that histone demethylation may play a crucial role in reproductive organ development. The expression of BrJMJ1, BrJMJ2, BrJMJ5, BrJMJ13, BrJMJ21 and BrJMJ24 gradually increased with higher Cd concentration under Cd stress, while BrJMJ4 and BrJMJ29 could be induced by osmotic, salt, cold, and heat stress. These results demonstrate that BrJMJs are responsive to abiotic stress and support future analysis of their biological functions.

Introduction

In eukaryotes, each nucleosome comprises 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped around a histone octamer, which includes a single H3–H4 tetramer and two H2A–H2B dimers. Besides their spherical structural domain, histones feature a flexible, charged amino-terminal (N-terminal) tail [1,2]. Histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) regulate chromatin structure through processes such as methylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation, particularly at N-terminal tail residues like lysine, arginine, and serine [3–5]. The addition or removal of these chemical groups on specific histone residues may alter histone–DNA interactions. These modifications are recognized as signals by chromatin-modifying proteins, thereby regulating transcriptional activities [4].

Methylation, one of the most common PTMs, primarily occurs at lysine and arginine residues and is catalyzed by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) and Suppressor of variegation, Enhancer of zeste, Trithorax (SET) structural domain proteins. Histone methylation is usually reversible and can be regulated by methyltransferases and demethylases. There are two key demethylases. The first is lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1, also known as KIAA0601), a nuclear ortholog of amine oxidase and the first demethylase to be discovered. The second is JmjC structural domain-containing histone demethylase (JHDM), which maintains histone methylation homeostasis in vivo [2,6,7]. As a histone demethylase, LSD1 demethylates lysine via a formaldehyde oxidation reaction [8,9]. Jumonji domain-containing proteins (JmjC) were initially identified in mice via a gene-trapping strategy that produced mutations in a gene critical for normal neural tube morphogenesis. The name “Jumonji” (meaning “cross” in Japanese) was derived from changes in neural plate morphology in these mutant mice [10]. Structural analysis has revealed that Jumonji, in the dioxygenase superfamily, has a conserved structural domain (the JmjC domain) with conserved 2-oxoglutarate-Fe (II) binding sites [11]. Proteins containing the JmjC structural domain may reverse histone methylation, while the substitution of histidine residues essential for Fe (II) interactions disrupts their demethylase activity. This suggests that demethylase activity depends on the integrity of the JmjC structural domain [12].

In animals, many key methylated histone marks with corresponding demethylases have been identified. Several histone demethylases with only the JmjC structural domain (referred to as “JmjC domain-only groups”) have been classified based on sequence similarity: lysine-specific demethylase 2 (KDM2)/JHDM1/FBX, KDM3/JMJD1/JHDM2, KDM4/JMJD2, KDM5/JARID, and JMJD3/KDM6). These groups target particular histone lysines with varying methylation statuses [13–15]. Although most JmjC proteins in animals are conserved in plants, Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) and rice (Oryza sativa L.) lack the KDM2/JHDM1 and KDM6/MJD motifs responsible for demethylating H3K36me2/1 and H3K27me3/2, respectively. In plants, JmjC family members are divided into nine subgroups: JMJ6, KDM3/JHDM2, KDM5/JARID1, putative KDMs (PKDMs) PKDM7–PKDM9, and PKDM11–PKDM13 [6,11,16]. In JmjC proteins, mutations in structural domains containing divalent ferrous ions, α-ketoglutarate, and histone polypeptide sites can significantly affect their catalytic activity [6]. For instance, in Rosa Chinensis Jacq. (Chinese rose), the lack of histone demethylase activity in RcJMJ40 is presumed to be due to the absence of two divalent ferrous ions and a fragment of the α-ketoglutarate binding site [14].

In plants, JmjC-containing proteins mediate the epigenetic processes associated with growth and development, transition to flowering, and stress responses [17–19]. JmjC gene family members are found in multiple species, including Arabidopsis [20], maize (Zea mays L.) [21], rice [5], Chinese rose [14]. In Arabidopsis, AtJMJ30 is responsible for regulating flowering time and root growth [22–24]. AtJMJ16 and AtJMJ17 are associated with leaf senescence and the osmotic response [25,26]. In Gossypium hirsutum (Upland cotton), GhJMJ34 and GhJMJ40 significantly enhance the response of the Upland cotton to salt and osmotic stress [27]. In rice, JMJ706 specifically demethylates the H3K9me2 site and is involved in the regulation of rice flower development [28]. And other JmjC genes of rice may play key roles in epigenetic regulation [6]. In summary, the JmjC gene may play an important role in plant growth, development and abiotic stress. To further understand their function, it is essential to identify and classify JmjC family members and develop sequence-based prediction of their demethylase activity.

Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) [29], the main leafy vegetable in China, with a long cultivation history, a wide variety of species, and distinct morphological characteristics [30]. Abiotic stresses including heat, freezing, cold, salinity, drought and nutrient imbalance, severely affect growth and development of Chinese cabbage [31]. The significance of JmjC structural domain-containing histone demethylases in stress resistance in plants is well recognized. However, the systematic research of the histone demethylase gene family in Chinese cabbage is still lacking, and their specific biological functions remain unclear. This study aimed to comprehensively identify histone demethylase-associated genes in Chinese cabbage through genome-wide analyses. By analysing gene structure, conserved structural domains, cis-acting element, chromosomal distribution, and gene duplication, we characterized the JmjC gene family in Chinese cabbage. Additionally, using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), we examined the expression of JmjC family member in the leaves under abiotic stress and characterized their evolutionary relationships and abiotic stress response patterns. Therefore, this study may provide a theoretical basis for further research on the functions of BrJMJ genes and for improving abiotic stress tolerance in Chinese cabbage.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Seedlings of the Chinese cabbage cultivar ‘Xiayang Early 50’ (a highly adaptable inbred variety) were planted in the seedling room of the Department of Horticulture, Jiangxi Agricultural University, China. Seedlings with 2.0–3.0 true leaves were transplanted into Hoagland nutrient solution for 10 days. A cadmium (Cd)-containing reagent (CdCl2·2.5H2O) was added to the nutrient solution to achieve varying final Cd concentration of Cd2 (2.0 mg·L-1), Cd4 (4.0 mg·L-1), Cd6 (6.0 mg·L-1), Cd8 (8.0 mg·L-1), and Cd10 (10 mg·L-1). A Hoagland solution without Cd was used as the control (CK). The treatments lasted for 7.0 days. In addition, other forms of abiotic stress were also assessed, including: osmotic strss (20% PEG6000), salt (200 mM NaCl), cold (4.0°C), and heat (38°C). Among them, osmotic stress (20% PEG6000) and salt (200 mM NaCl) were hydroponic in the seedling room. Hydroponic was performed in the incubator under cold (4.0°C) and heat (38°C) stress. Leaf samples were collected at 0.0, 3.0, 6.0, and 9.0 hours after treatment, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for subsequent RT–qPCR assay.

Genome-wide identification of BrJMJ genes

Genomic data for the ‘Brara_Chiifu_V3.0’ reference genome, includeding genome sequences, annotation files, protein sequence files and coding sequences (CDS), were obtained from the Brassicaceae Database (BR-AD) (http://brassicadb.cn/). The JmjC genes were downloaded from the Arabidopsis Genome Database (TAIR http://ara-bidopsis.org/) and aligned with JmjC protein sequences from the Chinese cabbage protein sequence set using BlastP. Sequences with an e-value of 1 × 10−10 were selected using TBtools [30]. Gene function identification was performed using a Hidden Markov Model. BrJMJ genes were screened in Chinese cabbage protein sequence databases using TBtools. Combining these methods, duplicate and low-coverage sequences were removed, and protein sequences initially screened in the SwissProt database (National Center for Biotechnology Information, NCBI) were further compared. Candidate sequences were scrutinized based on their annotations and validated through one-by-one comparison with SMART (http://smart.emblheid-elberg.de/), HMMER (https://www.eb-i.ac.uk/Tools/hmm-er/) and Pfam (http://pfa-m.xfam.org/) databases. Finally, the BrJMJ genes were numbered based on their chromosomal locations.

Phylogenetic tree establishment

To elucidate the JmjC family tree and functional features in Chinese cabbage, we gathered gene IDs and protein sequences of AtJMJs, OsJMJs, ZmJMJs, BpJMJs, and GmJMJs from published studies on Arabidopsis (At) [32], Oryza sativa (Os) [33], Zea mays L (Zm) [21], Betula pendula (Bp: silver birch) [34], and Glycine max (Gm, soybean) [7]. In total, 158 JmjC proteins from these species were compared and analyzed using MEGA 11.0. A root-less phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. The evolutionary tree was embellished and clustered for annotation using Evolview (www.ev-olgenius.info/evol-view/). The evolutionary relationships between JmjC family genes in Brassica rapa and other species were analyzed.

Gene structure, protein structural domain allocation, and cis-acting elements

Based on the annotated Brassica rapa genome files (GFF format), gene structures were analyzed and their structures were visualized using TBtools [35]. The protein structure of each BrJMJ-encoded protein was predicted using SMART (http://smart.embl-hei delberg.de/). Sequences 2,000 bp upstream of the BrJMJs transcriptional start site were extracted using using the ‘GTF/GFF3 Sequences Extract’function of TBtools and submitted to the PlantCARE website (https://bioinfor-matics.psb.ugent.b-e/webtools/plantcare/html/) for prediction of potential cis-acting elements. The results were visualized using TBtools.

Chromosomal distribution and gene duplication analysis

JmjC gene family members were localized to each chromosome based on genome annotations and were plotted for analysis using TBtools. Gene duplication analysis in Chinese cabbage was performed using BLAST comparisons with BrJMJ proteome sequences. Covariances among JmjC gene family members were visualized and plotted using MCScanX.

Transcriptome analysis of BrJMJ gene family in different tissues

Transcriptomes data of Brassica rapa stems (SRX213893), siliques (SRX213892), roots (SRX213890), leaves (SRX213888), flowers (SRX213887), and callus tissues (SRX213886) were downloaded from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.ni-h.gov/sra). The TPM values of BrJMJs in transcripts from different tissues were obtained by analysis using the RNA-seq tool in TBtools, and visual heatmaps were generated using the Heatmap tool in the software.

Analysis of expression specificity in response of BrJMJ genes to abiotic stress by qRT–PCR

RNA was extracted from stress-treated Chinese cabbage samples (Cd, osmotic, salt, cold, and heat stress) using the MolPure®TRIeasy Plus Total RNA Kit (Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). RNA quality was determined using an ultra-micro spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron Corp, USA), with an OD260/280 ratio of 1.8–2.0. The cDNA was synthesized using the Hifair® III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (Yeasen). DNAMAN 6.0 was used to design the BrJMJ qRT-PCR primers.

The reaction mixture for qRT–PCR contained 1.0 μL cDNA, 10 μL Universal Blue SYBR Green Master Mix, 0.5 μL each of the forward and reverse primers, and 8.0 μL sterile ultrapure water. The procedure was as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 2.0 minutes, denaturation at 95°C for 10 seconds, and annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, with synthesis of 40 cycles. The primer sequences were listed in S1 Table (BrActin7 was used as the internal reference gene), and target gene relative expression was calculated using the Eq 2-ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analysis

Three biological replicates were used for each stress treatment in qRT-PCR. Significant differences in gene expression were detected using Duncan’s method in SPSS 22.0. TBtools and Origin were used to analyze and visualize plots.

Results

Identification and phylogenetic analyses of the JmjC family

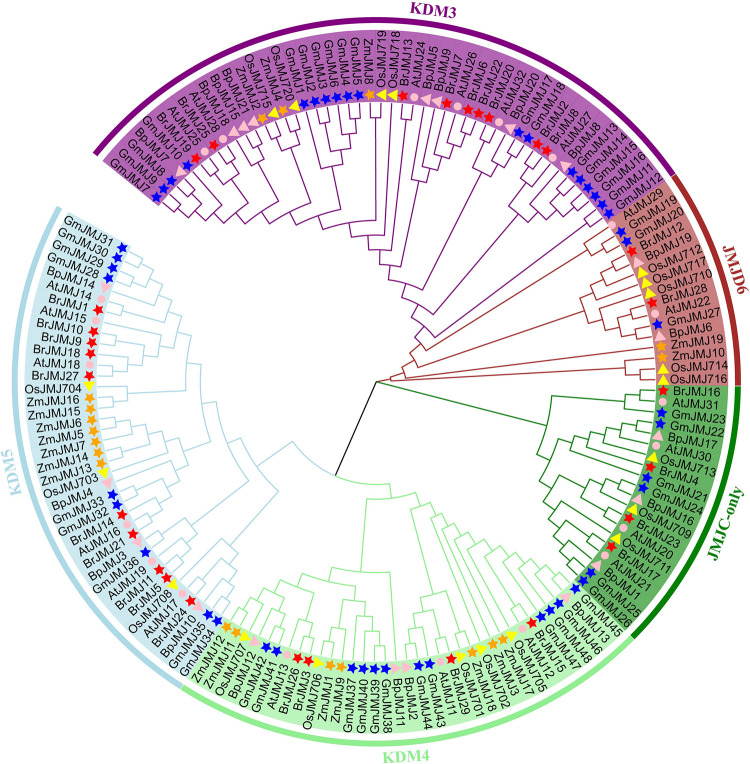

Based on the Brassica rapa genome published in the Brassicaceae Database (BRAD) [21], we identified 29 BrJMJs (BrJMJ1–29) after eliminating false discovery and sequence redundancy (S1 Table). Using Mega 11, a phylogenetic tree was generated based on 158 JmjC protein sequences from six species, including Chinese cabbage, Arabidopsis, rice, maize, birch, and soybean (Fig 1). Based on the phylogenetic tree, the JmjC family can be split into five subfamilies, including the JMJD6, KDM3/JHDM2, KDM4/JHDM3, KDM5/JARID1, and JmjC-only domain subfamilies. In addition to the JmjC-only domain subfamily, the remaining four subfamilies all contain BrJMJ genes from Chinese cabbage, Arabidopsis, rice, maize, birch, and soybean. Indicating that these four subfamilies were retained among the six species [36]. KDM3/JHDM2 was the largest subfamily, with 48 homologous JmjC protein sequences; KDM5/JARID1 was the second largest, with 39 homologous JmjC protein sequences; and JMJD6 was the smallest, with 16 homologous JmjC protein sequences. In addition, KDM4/JHDM3 and JmjC-only domains had 35 and 20 homologous JmjC protein sequences, respectively. The JmjC-only domain subfamily does not exist in maize.

Fig 1. Phylogenetic relationships of JmjC family members in Brassica rapa (Br), Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Zea mays (Zm), Oryza sativa (Os), Betula platyphylla (Bp), and Glycine max (Gm).

Using MEGA11.0, a phylogenetic tree was constructed for 158 JmjC protein sequences from the six species. Red stars, pink circles, orange stars, yellow triangles, pink triangles, and blue starts: Br, At, Zm, Os, Bp, and Gm, respectively.

The BrJMJs were closely associated with the AtJMJs, followed by OsJMJs, ZmJMJs, and GmJMJs. Among members of subfamilies, the BrJMJs were most evolutionarily distant from the BpJMJs, possibly reflecting the significant evolutionary gap between herbaceous and woody species. Over >55% of the BrJMJs showed the highest sequence similarity with Arabidopsis homologs. For example, in the KDM3 subfamily, BrJMJ25 of Chinese cabbage exhibited high homology with Arabidopsis AtJMJ28 (bootstrap values: 100%). In the KDM5 subfamily, Chinese cabbage BrJMJ27 and Arabidopsis AtJMJ18 (bootstrap values: 100%) had great evolutionary similarities, so they belong to homologous proteins. It is suggested that a high degree of sequence homology between the BrJMJs of Chinese cabbage and the AtJMJs of Arabidopsis, likely attributed to both species belonging to the crucifer family.

Gene structure and conserved structural domains

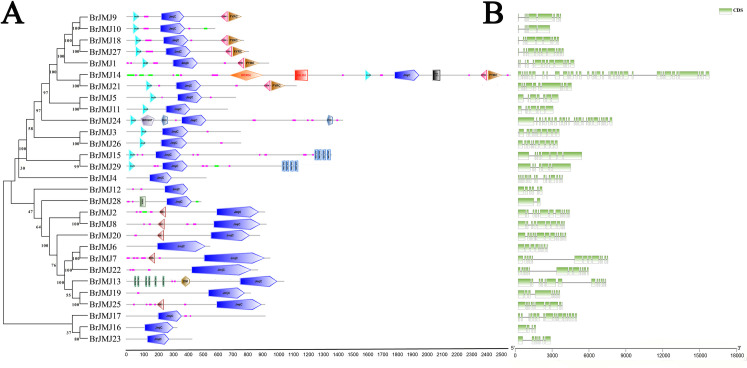

The analysis of protein structural domains helps to reveal the functional and evolutionary relationships of the proteins, shedding light on potential similarities in their functions. To further investigate the differences and commonalities in the structural domains of the different BrJMJs proteins, we performed protein structural domain analysis using the SMART tool (Fig 2A). Our analysis showed that JmjC proteins contain 14 structural domains, with the JmjC structural domain being the most widely distributed, with the JmjC structural domain obviously present in all BrJMJ proteins. The JmjN structural domain was the second most widely distributed, present in 14 BrJMJ proteins. BrJMJ14 exhibited the greatest complexity in structural domains, having six structural domains: JmjC (Jumonji C), JmjN (Jumonji N), DEXDc (DEAD-like helicases superfamily), HELICc (Helicase superfamily c-terminal domain), FYRN (“FY-rich” domain N-terminal) and FYRC (“FY-rich” domain C-terminal) [37]. Among them, the FYRN and FYRC structural domains may promote the function of JmjC by interacting with other proteins [7]. BrJMJ24 contained the specific ARID (AT-rich interaction domain) [7] and PHD (Plant Homeodomain) structural domains. Among them, the PHD structural domain recognized as a versatile epigenetic reader for recognizing H3K4me3, H3K4me, or H3K14ac [38], so we speculate a potential role for BrJMJ24 in versatile epigenetic. BrJMJ15 and BrJMJ29 contained the specific ZnF_C2H2 (zinc-finger of C2H2-type) domain [7]. BrJMJ28 contained a structural F-box (FBOX a receptor for ubiquitination targets) [14], and BrJMJ13 had two specific protein structural domains, DM (Dsx and Mab-3) and AT-hook (DNA binding domain with preference for A/T rich regions) [37]. Additionally, five proteins (BrJMJ2, BrJMJ7, BrJMJ8, BrJMJ20 and BrJMJ25) contained RING (really interesting new gene) [7] as a specific structure. Different BrJMJs have several conserved and specialized domains, which means that the protein structure of the BrJMJ family maybe diverse.

Fig 2. Conserved structural domains of BrJMJ proteins in Chinese cabbage.

JmjC, Jumonji C domain; JmjN, Jumonji N domain; DEXDc, DEAD-like helicases superfamily; HELICc, Helicase superfamily c-terminal domain; PHD, plant homeobox domain; ARID, AT-rich interaction domain; FYRC, “FY-rich” domain C-terminal; FYRN, “FY-rich” domain N-terminal; F-box FBOX a receptor for ubiquitination targets; ZnF_C2H2, zinc-finger of C2H2-type; AT_hook, DNA binding domain with preference for A/T rich regions; DM, Dsx and Mab-3; RING, really interesting new gene (A). Gene structure analysis of BrJMJs in Chinese cabbage, green boxes, exons; black lines, introns. The sizes of exons and introns can be estimated using the scale at the bottom (B).

The intron and exon structure are an important clue to understand the gene evolutionary relationship and functional diversification within a gene family. To further analyze the exon-intron structure and conserved structural regions of the JmjC gene family members, we mapped the structures of the 29 BrJMJs using TBtools. Members of the JmjC gene family contained 2.0–36 exons, with the majority having between 7.0 to 16 exons (Fig 2B). Notably, BrJMJ28 contained the fewest exons (two), while BrJMJ14 the most (36). The large variation in the number of exons may reflect the diversity of JmjC gene family members in Chinese cabbage. Furthermore, we observed a high level of consistency in gene structure among specific groups of genes, such as BrJMJ20/ BrJMJ2/ BrJMJ8, BrJMJ5/ BrJMJ11, BrJMJ19/ BrJMJ25, BrJMJ15/ BrJMJ29, and BrJMJ3/ BrJMJ26, which have the same exon/intron arrangement and number as well as very similar exon lengths.

Conserved structural domains of BrJMJ proteins in Chinese cabbage. JmjC, Jumonji C domain; JmjN, Jumonji N domain; DEXDc, DEAD-like helicases superfamily; HELICc, Helicase superfamily c-terminal domain; PHD, plant homeobox domain; ARID, AT-rich interaction domain; FYRC, “FY-rich” domain C-terminal; FYRN, “FY-rich” domain N-terminal; F-box FBOX a receptor for ubiquitination targets; ZnF_C2H2, zinc-finger of C2H2-type; AT_hook, DNA binding domain with preference for A/T rich regions; DM, Dsx and Mab-3; RING, really interesting new gene (A). Gene structure analysis of BrJMJs in Chinese cabbage, green boxes, exons; black lines, introns. The sizes of exons and introns can be estimated using the scale at the bottom (B).

Cis-acting element analysis

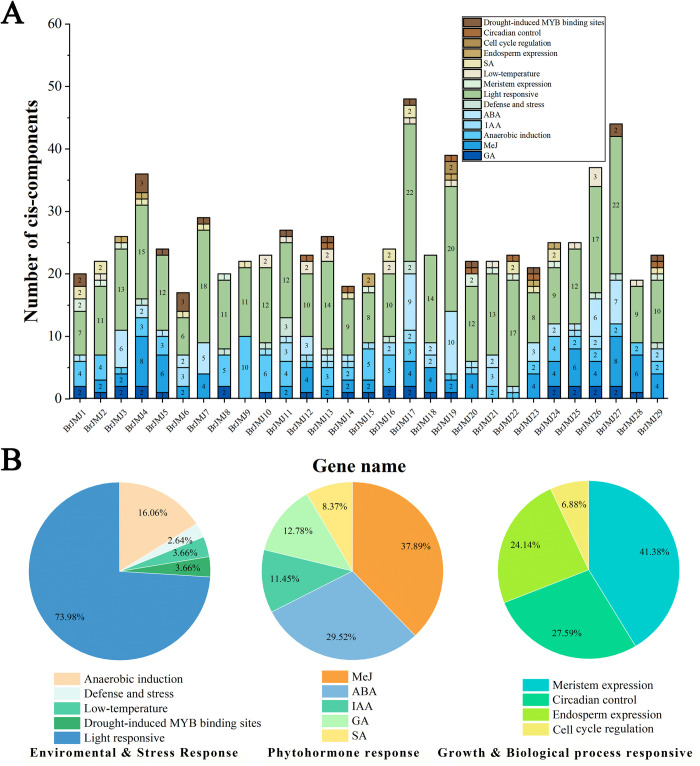

To further elucidate BrJMJs regulation in response to biotic and abiotic stress, we used PlantCARE to analyze the promoter cis-acting elements within the 2000 bp sequence upstream of the start codons of each BrJMJ gene in the Chinese cabbage (Fig 3). Our analysis revealed a variety of phytohormone response elements within the JmjC family, including methyl jasmonate (in 37.89% of the genes), abscisic acid (29.52%), gibberellin (12.78%), growth hormones (11.45%) and salicylic acid (8.37%) elements. Additionally, the JmjC family contains many cis-acting elements associated with defense or responses to abiotic stresses, such as light-responsive element (73.98%) and anaerobically induced (16.06%). The light-responsive element was present in all 29 genes and anaerobic stress-related cis-acting elements were present in most of the genes (86.21%). Growth and biological process responsive elements included meristem expression-responsive elements (41.38%), physiological rhythm-regulating action elements (27.59%) and endosperm expression-specific elements (24.14%).

Fig 3. Cis-acting elements of BrJMJs in Brassica rapa.

Different color blocks represent different components. Relative frequencies in BrJMJs of promoter cis-regulatory elements (CREs), including environment and stress-responsive CREs, phytohormone response CREs, and growth and biological process-responsive CREs.

In terms of gene regulation, the promoters of BrJMJ17, BrJMJ19, and BrJMJ27 were found to contain a variety of light-oriented response elements and ABA response elements. BrJMJ4, BrJMJ27, and BrJMJ28 were identified to have multiple elements associated with the methyl jasmonate response. Additionally, BrJMJ9 contained numerous elements associated with anaerobic responses, suggesting that this gene may play an important role in an anoxic environment. BrJMJ19 was the only member that contained cis-acting elements related to cell-cycle responses, whereas BrJMJ17 had the most cis-acting elements, including those related to light-response and low-temperature, defense mechanism, anaerobic induction and phytohormone response. These findings suggest that the BrJMJ promoters contain numerous and diverse cis-acting elements, potentially acting across multiple abiotic stresses.

Chromosomal distribution and gene duplication

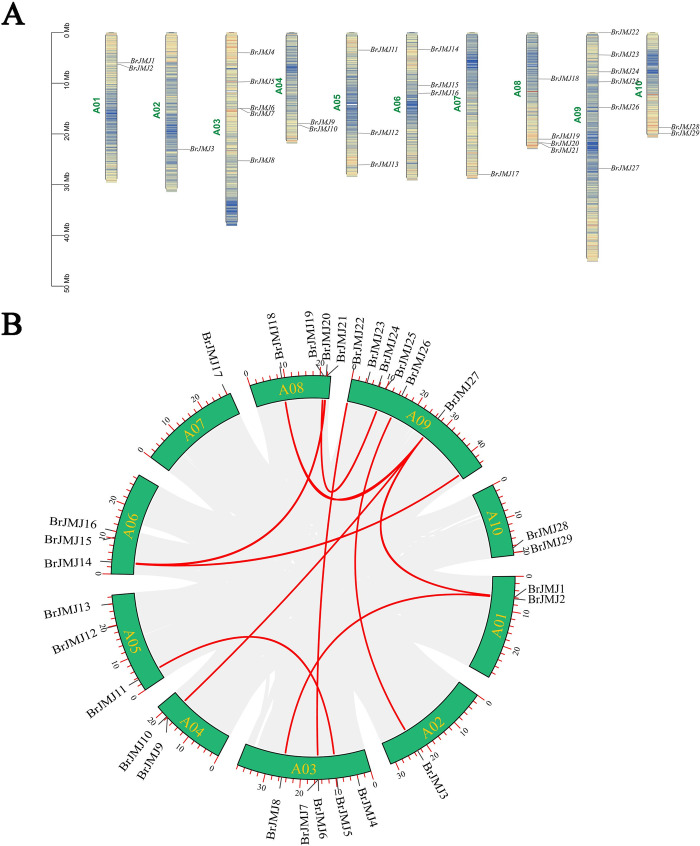

Based on the Chinese cabbage genome annotation file and JmjC gene family member data, a chromosome localization map of BrJMJ family genes was constructed using TBtools (Fig 4A). The 29 BrJMJs were found to be distributed across ten chromosomes, with chromosomes A02 and A07 each contained only one BrJMJ. Notably, 37.93% of the genes were distributed on chromosomes A03 and A09, indicating an uneven distribution of the 29 BrJMJs on the chromosomes. It is suggested that BrJMJ genes might have undergone duplication or loss in the process of evolution.

Fig 4.

Chromosome distribution (A) and schematic representation of inter-chromosomal relationships (B) of the BrJMJs in Brassica rapa. Repeated BrJMJ pairs are highlighted with red lines.

Three types of gene duplication events have been reported, including tandem duplication, segmental duplication, and whole-genome duplication [39]. To investigate duplication of BrJMJs on chromosomal segments, covariance analysis of the BrJMJ family genes was conducted by using MCScanX. This analysis revealed that 10 pairs of JmjC genes exhibited duplication events among the 29 BrJMJ genes (Fig 4B). Interestingly, the 10 pairs of duplicated genes were found to be located on different chromosomes, suggesting that they were produced by segmental duplication, such as BrJMJ5/ BrJMJ11, BrJMJ13/ BrJMJ26, and BrJMJ18/ BrJMJ27. Therefore, this indicates that gene segmental fragment duplication is likely the main method of expansion of the JmjC gene family in Chinese cabbage.

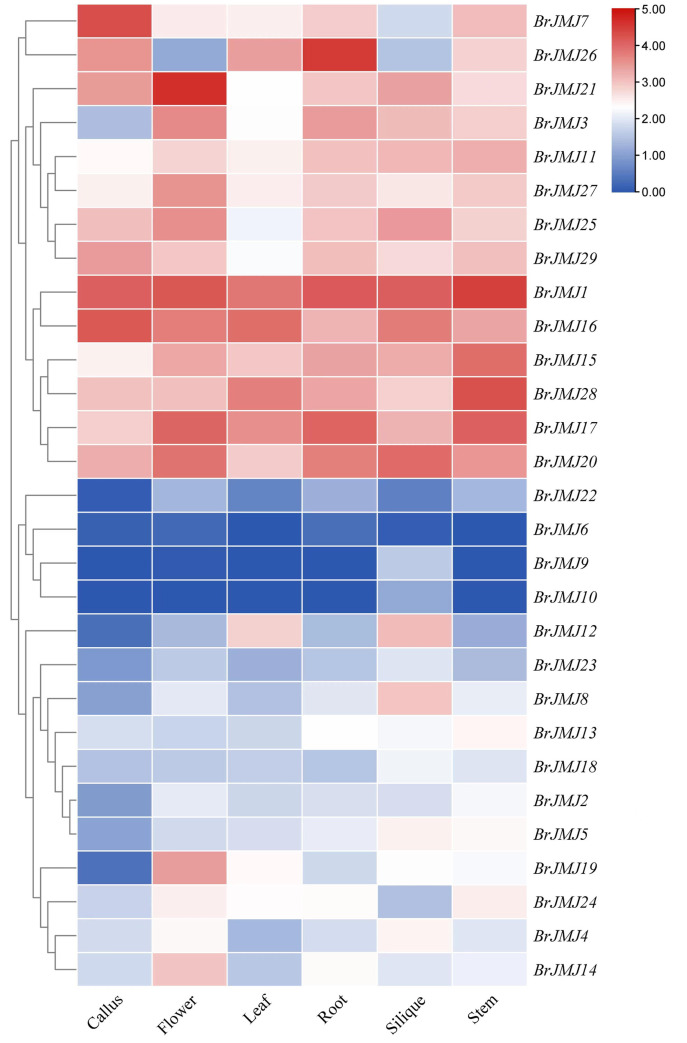

Profiling of tissue-specific BrJMJ gene expression

Based on the analysis of transcriptome data from the Brassicaceae Database, Fig 5 displayed a heatmap of tissue-specific BrJMJ expression in various tissues including callus, flower, leaf, root, silique, and stem. The majority of the 29 BrJMJs exhibited high expression levels in the reproductive organs such as siliques and flowers. Some genes (BrJMJ14/ BrJMJ19/ BrJMJ21/ BrJMJ27) expression was high in the flowers, while other genes (BrJMJ8/ BrJMJ9/ BrJMJ10) displayed high levels of expression in the siliques, suggesting a potential role of histone demethylation in the growth of reproductive organs in Chinese cabbage. In addition, approximately one-third of BrJMJs were highly expressed in stems and root, with some genes (BrJMJ7/ BrJMJ16/ BrJMJ29) being expressed in callus tissues. Interestingly, BrJMJ14/ BrJMJ21 belonged to the same branch of the phylogenetic tree (Fig 1A), but showed different expression patterns in the same tissues. As a result, it can be speculated that they acquire different functions after the duplication event.

Fig 5. Tissue-specific BrJMJ expression.

The heatmap was constructed using TBtools, based on the fragments per kilobase of transcripts per million mapped reads (FPKM) values of BrJMJs in the tissue-specific transcriptome data.

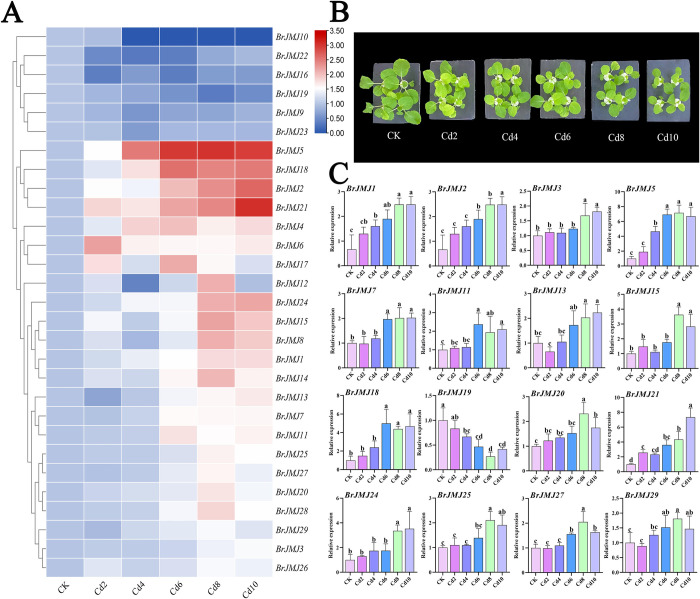

BrJMJ expression under Cd stress

To further investigate the functions of BrJMJs under Cd stress, the relative expression of the 29 BrJMJs was quantified at Cd concentrations of 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0 and 10 mg/L by qRT–PCR. A heatmap was generated to visualize the expression patterns (Fig 6A–6C). With the exception of BrJMJ10, the remaining 28 BrJMJs were differentially expressed under Cd treatment, with over >52.0% showing upregulated expression (Fig 6A). Under the same treatment time, the higher the cadmium concentration, the smaller the leaves of Chinese cabbage (Fig 6B). The expression of certain genes (BrJMJ1, BrJMJ2, BrJMJ5, BrJMJ13, BrJMJ21 and BrJMJ24) increased gradually with increasing Cd concentrations and their expression levels were positively correlated (Fig 6C). Additionally, BrJMJ3, BrJMJ7, BrJMJ15, BrJMJ18, BrJMJ20, BrJMJ25, BrJMJ27, and BrJMJ29 were significantly upregulated (p<0.05) at high Cd concentrations (Fig 6C). BrJMJ15, BrJMJ20, BrJMJ25, BrJMJ27, and BrJMJ29 were significantly upregulated at a Cd concentration of 8.0 mg/L, with a lesser upregulation at 10 mg/L. The expression of BrJMJ11/ BrJMJ18 was significantly upregulated (p<0.05) at a Cd concentration of 6.0 mg/L, but showed less upregulation at Cd levels ≥8.0 mg/L (Fig 6C). BrJMJ9, BrJMJ16, BrJMJ19, BrJMJ22, and BrJMJ23 exhibited downregulation with Cd treatment. BrJMJ19 expression declined gradually with increasing Cd content (Fig 6C). This suggests that numerous BrJMJs may play a role in resistance to Cd stress.

Fig 6. Profiling of BrJMJ expression under Cd stress.

Variation in BrJMJ gene expression with Cd stress, via qRT–PCR, with BrACTIN7 as an internal reference gene. BrJMJ relative expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The results were visualized as a heatmap using TBtools (A). Growth status of Chinese cabbage under Cd stress. Scale bar, 4 cm (B). Using the same RT-qPCR results as in Fig 6A, a histogram of representative genes were generated to analyze significance. Brassica rapa growth varied significantly under Cd stress, with different lowercase letters indicating significant differences (p<0.05). The x axis represents different concentrations of Cd stress treatment, and the y axis represents relative expression (C).

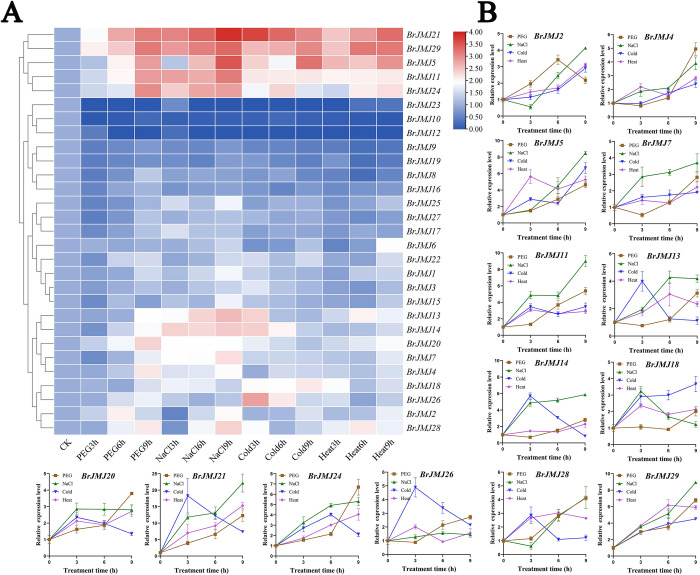

BrJMJ expression under other abiotic stresses

The expression of JmjC proteins under environmental stimulation is specific [40]. Using qRT-PCR, we investigated JmjC family member expression in the leaves under osmotic, salt, cold, and heat stress. A heatmap was generated using the TBtools (Fig 7A). Among the 29 BrJMJs analyzed, the remaining BrJMJs showed differential expression under these abiotic stresses, except for BrJMJ10/ BrJMJ12/ BrJMJ23.

Fig 7. Profiling of BrJMJ expression under other abiotic stresses.

Expression under drought, salt, cold, and heat stress of the 29 BrJMJs, via qRT–PCR. BrACTIN7 was an internal reference gene. BrJMJ relative expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The results were visualized as a heatmap using TBtools (A). The significant changes of representative genes under four abiotic stresses are indicated by the length of vertical lines (p<0.05). Red polyline, green polyline, blue polyline and purple polyline are respectively represented Expression under osmotic, salt, cold, and heat stress of the 29 BrJMJs. The x axis represents the different treatment times of the four abiotic stresses (osmotic, salt, cold, and heat stress), and the y axis represents the relative expression (B).

Under osmotic stress, 65.4% of the BrJMJs were upregulated (log2FC>1.5) (Fig 7A). And the expression levels of BrJMJ2 was more than 2.0-fold higher with expression levels in the control group following 6.0 hours of osmotic treatment. Under salt stress, 50.0% were upregulated, with expression levels correlating positively with stress treatment duration (log2FC>1.5) (Fig 7A). However, downregulation of BrJMJ18 expression increased with treatment time. BrJMJ20 was upregulated but upregulation of its expression tended to be stable over treatment time. The expression of BrJMJ26 was unaffected by salt stress (Fig 7B). Under cold stress, 46.2% of BrJMJ genes were downregulated, with the degree of downregulated expression increasing over treatment time (log2FC>1.5) (Fig 7A). Under heat stress, 74.0% of BrJMJ genes were upregulated (log2FC>1.5). It can be speculated that the gene expression of the BrJMJ family is significantly affected by low-temperature stress. However, some genes (BrJMJ13/ BrJMJ14/ BrJMJ21/ BrJMJ26) expressions reached their highest levels after 3.0 hours of cold stress but were subsequently inhibited by prolonged exposure to cold stress. Notably, BrJMJ29/ BrJMJ5/ BrJMJ2 were upregulated under both heat and cold stress.

Combining the four abiotic stresses (cold, heat, osmotic, and salt), it was observed that the expression of BrJMJ1/ BrJMJ15/ BrJMJ25 was generally unaffected by the four types of abiotic stress, except for slight upregulation under 9.0 hours salt treatment. Conversely, BrJMJ2, BrJMJ4, BrJMJ5, and BrJMJ29 were upregulated under all stress treatments. In particular, the expression level of BrJMJ29 was upregulated under the four abiotic stresses compared with the control group, and the expression was positively correlated with stress-treatment duration (Fig 7B). These findings indicate that BrJMJs may have significant roles in the responses of Chinese cabbage to abiotic stresses.

Discussion

Epigenetic regulation has garnered increasing attention in the realms of plant growth, development, and stress responses [21]. Within the realm of epigenetic gene expression regulation, PMTs and demethylases are pivotal in modulating histone methylation status [41]. Additionally, JmjC proteins play a crucial role in regulating epigenetic processes as well as the growth and development of plants [7]. The JmjC family has been extensively studied in various species such as Arabidopsis [32], rice [33], birch [34], soybean [7], maize [21], Pyrus bretchneideri [41], and Upland cotton [37]. This research aimed to identify and characterize the expression of JmjC family members in Chinese cabbage. The study delved into the gene structure, conserved structural domains, cis-acting elements, chromosomal distribution, and gene duplication of BrJMJs using specialized software.

The number of JmjC family members varies among species, such as in Arabidopsis (21 JmjC genes) [32], rice (20 JmjC genes) [33], maize (19 JmjC genes) [21], and birch (21 JmjC genes) [34], while significantly more JmjC genes were identified in soybean (48 JmjC genes) [7]. This indicates potential differences in evolutionary history among species. In this study, phylogenetic analysis identified 29 JmjC genes in Chinese cabbage, serving as a valuable reference for genetic evolution studies in this species probably. The BrJMJs were classified into five subfamilies (JMJD6, KDM3/JHDM2, KDM4/JHDM3, KDM5/JARID1, and JmjC-only domain) in Chinese cabbage, which is consistent with findings in other plant species like Arabidopsis, soybean, birch, rice and Lycopersicon esculentum [42]. This suggests potential functional similarities between BrJMJs and JmjC genes across these species. The majority of BrJMJs clustered closely with AtJMJs on small branches, likely due to both species being Brassicaceae (cruciferae) dicotyledonous plants, distinct from monocotyledonous plants like rice and maize.

In plants, tandem and segmental duplication are the most common causes of gene family expansion [43,44], with segmental duplication occurring frequently in slower-evolving gene families [45]. Gene duplication leads to functional diversity and the generation of new genes, with significant implications for environmental adaptation, biological evolution, and continued species evolution probably [46]. Among the 29 BrJMJs found in Chinese cabbage, 10 pairs are the result of segmental duplication. We speculate that segmental duplication may have contributed to expansion of JmjC gene family in Chinese cabbage, potentially playing a crucial role in environmental adaptation.

Cis-acting promoter elements interact with transcription factors to regulate gene transcription [47–49]. The function of the JmjC family members can be inferred from the analysis of cis-acting elements [46]. In this study, BrJMJ17 had the most cis-acting elements, including those related to light-response, low-temperature, defense mechanism, anaerobic induction and phytohormone response. It can be speculated that BrJMJ17 may play an important role in plant stress. Interestingly, JMJ524 responds to circadian rhythms and was upregulated by GA treatment in tomato [50]. However, this phenomenon has not been found in Chinese cabbage, which requires further validation. These results reveal that JmjC genes potentially regulate plant metabolic processes by involving biotic and abiotic responses.

JmjC gene expression varies among species and tissue types. And JmjC gene demethylases play an important role in plant growth and development [51]. In wheat, JmjC expression was higher in nutritional tissue growth than in reproductive organ growth and was higher in roots and spikes than in leaves and seeds [46]. In Chinese rose, most of the JmjC genes were highly expressed in reproductive tissues but not in nutritional tissues [14]. Here, most of the BrJMJs were highly expressed in the reproductive organs (siliques and flowers) and some were highly expressed in the stems and roots. These results indicate that histone demethylation plays a potential role in both nutritional tissue growth and reproductive organ growth of Chinese cabbage, particularly during reproductive organ growth.

BrJMJ14/ BrJMJ21 belonged to the same branch of the phylogenetic tree (Fig 1), but showed different expression patterns in the same tissues. It can be speculated that they may have acquired different functions following the duplication event. Comparable expression patterns of JmjC genes have also been observed in cotton [37] and soybean [7].

When plants are subjected to heavy metal stress in the environment, their organs repress or initiate certain gene expression by altering DNA methylation in response to achieve resistance to heavy metal stress [24]. In Arabidopsis, Cd can induce an increase in DNA methylation [52]. In wheat (Triticum aestivum), Cd phytotoxicity can alter DNA methylation levels to confer heavy metal tolerance [53]. Additionally, overexpression of the histone demethylase gene SlJMJ524 from tomato enhances Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis by regulating metal transporter-related protein genes and flavonoid content [54]. Over >52.0% of BrJMJs were differentially upregulated in expression level under Cd stress. Among them, the expression levels of BrJMJ1/ BrJMJ2/ BrJMJ5/ BrJMJ13/ BrJMJ21/ BrJMJ24 gradually increased with Cd concentrations increasing and had a positive correlation. These findings highlight the significance of DNA methylation in Chinese cabbage resistance to Cd toxicity [55].

Different abiotic stresses can regulate the expression of JmjC genes, thus influencing plant growth and development [34]. Our study observed differential expression of most BrJMJs under four abiotic stresses (osmotic, salt, cold, and heat). In particular, over >74.0% of BrJMJs were upregulated in expression level under heat stress, such as BrJMJ2/ BrJMJ21/ BrJMJ24/ BrJMJ29. H3K36me2/3 demethylase can improve the resilience of Chinese cabbage under heat stress [56]. We speculate that these genes may play an important regulatory role in improving Chinese cabbage resistance to high temperature stress. Similarly, in maize, the expression of seven genes of the ZmJMJs family (ZmJMJ3, ZmJMJ5, ZmJMJ8, ZmJMJ10 and ZmJMJ19) can be upregulated with heat stress [21]. Our findings revealed that half of BrJMJs were significantly downregulated under cold stress (log2FC>1.5), implying a response to external low temperatures by downregulating BrJMJs in Chinese cabbage probably, which is consistent with the findings in birch [34]. Conversely, most JmjC gene members of the allotetraploid cotton species showed upregulate in response to cold stress [37]. BrJMJ11/ BrJMJ21/ BrJMJ28/ BrJMJ29 were significantly upregulated under osmotic stress and salt stress. Similar findings were observed in cotton, where GhJMJ40 and GhJMJ34 showed upregulated expression [37], suggesting that these genes might have the same regulatory mechanisms under osmotic stress and salt stress in both cotton and Chinese cabbage. A similar phenomenon exists in Jatropha curcas L. (Jatropha), with JcJMJ18 expression significantly upregulated under salt stress [15]. This suggests that JmjC family genes may actively respond to osmotic and salt stress by up-regulating their expression [15]. In conclusion, the varied expression patterns of BrJMJs under different abiotic stress conditions imply their responsiveness to stress treatments.

Conclusions

This study conducted a comprehensive analysis on the structural characteristics, evolutionary relationships, and gene expression of JmjC gene family members in Chinese cabbage. A total of 29 members were identified, showcasing a high level of conservation at the genome level. By analyzing the evolutionary relationships of BrJMJs, a high degree of sequence homology between the BrJMJs of Chinese cabbage and the AtJMJs of Arabidopsis was observed. This may be attributed to their shared membership in the crucifer family. For these genes, the promoter cis-acting elements were enriched in response to stress related to light, low-temperature, anaerobic conditions and phytohormone treatment. The high expression of BrJMJs in the siliques and flowers indicated a potential role of histone demethylation in reproductive organ growth. Furthermore, stress associated with Cd exposure, osmotic, salinity, cold, and heat induced their expression. These findings may provide a theoretical basis and reference for further research on the potential functions of Chinese cabbage BrJMJs and improving abiotic stress tolerance in Chinese cabbage.

Supporting information

It includes the gene name, gene ID, forward primer sequence, reverse primer sequence, and the gene name and gene ID of the closest Arabidopsis thaliana homolog for each of the BrJMJ genes.

(PDF)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The Natural Science Foundation of China (31860560) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20224BAB205027). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Timothy Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997; 389:251–260. 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niu Y, Bai J, Zheng S. The Regulation and Function of Histone Methylation. Journal of Plant Biology. 2018; 61(6):347–357. 10.1007/s12374-018-01766. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the Histone Code. Science. 2001; 293(55–32):1074–1080. 10.1126/science.1063127. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cairns BR. The logic of chromatin architecture and remodelling at promoters. Nature. 2009; 461(7261):193–198. 10.1038/nature08450. doi: 10.1038/nature08450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allis CD, Jenuwein T. The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2016; 17(8):487–500. 10.1038/nrg.2016.59. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu F, Li G, Cui X, Liu C, Wang XJ, Cao X. Comparative Analysis of JmjC Domain‐containing Proteins Reveals the Potential Histone Demethylases in Arabidopsis and Rice. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2008; 50(7):886–896. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00692.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00692.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Y, Li X, Cheng L, Liu Y, Wang H, Ke D, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Soybean JmjC Domain-Containing Proteins Suggests Evolutionary Conservation Following Whole-Genome Duplication. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016; 7:1800. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01800. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, et al. Histone Demethylation Mediated by the Nuclear Amine Oxidase Homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004; 119(7):941–953. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao J, Lee U-S, Wagner D. Tug of war: adding and removing histone lysine methylation in Arabidopsis. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2016; 34:41–53. 10.10 16/j.pbi.2016.08.002. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi T, Yamazaki Y, Katoh-Fukui Y, Tsuchiya R, Kondo S, Motoyama J, et al. Gene trap capture of a novel mouse gene, jumonji, required for neural tube formation. Genes Development. 1995; 9:1211–1222. 10.1101/gad.9.10.12-11. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC-domain-containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2006; 7(9):715–727. 10.1038/n-rg1945. doi: 10.1038/nrg1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X, Hu Y, Zhou DX. Epigenetic gene regulation by plant Jumonji group of histone demethylase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)—Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2011; 1809(8):421–426. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.03.0 04. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosammaparast N, Shi Y. Reversal of Histone Methylation: Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms of Histone Demethylases. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2010; 79(1):155–179. http://10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.07090-7.103946. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong Y, Lu J, Liu J, Jalal A, Wang C. Genome-wide identification and functional analysis of JmjC domain-containing genes in flower development of Rosa chinensis. Plant Molecular Biology. 2020; 102(4–5):417–430. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00955-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Jiang X, Bai H, Liu C. Genome-wide identification, classification and expression analysis of the JmjC domain-containing histone demethylase gene family in Jatropha curcas L. Scientific Reports. 2022; 12(1):6543. 10.10-38/s41 598-022-10584-3. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-10584-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo M, Hung FY, Yang S, Liu X, Wu K. Histone Lysine Demethylases and Their Functions in Plants. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2014; 32(2):558–565. 10.1007/s1-1105-013-0673-1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kooistra SM, Helin K. Molecular mechanisms and potential functions of histone demethylases. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012; 13(5):297–311. 10.1038/nr-m3327. doi: 10.1038/nrm3327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He X, Wang Q, Pan J, Liu B, Ruan Y, Huang Y. Systematic analysis of JmjC gene family and stress--response expression of KDM5 subfamily genes in Brassica napus. PeerJ. 2021; 9: e11137. 10.7717/peerj.11137. doi: 10.7717/peerj.11137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Feng S, Zhang Y, Xu L, Luo Y, Yuan Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the plant-specific PLATZ gene family in Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). BMC Plant Biology. 2022; 22(1):160. 10. 1186/s12870-022-03546-4. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03546-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang TJ, Huang S, Zhang A, Guo P, Liu Y, Xu C, et al. JMJ17-WRKY40 and HY5-ABI5 modules regulate the expression of ABA‐responsive genes in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist. 2021; 230(2):567–584. 10. 1111/nph.17177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian Y, Chen C, Jiang L, Zhang J, Ren Q. Genome-wide identification, classification and expression analysis of the JmjC domain-containing histone demethylase gene family in maize. BMC Genomics. 2019; 20(1):1–16. 10.1186/s12 864-019-5633-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee K, Park OS, Seo PJ. JMv30‐mediated demethylation of H3K9me3 drives tissue identity changes to promote callus formation in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2018; 95(6):961–975. 10.1111/tpj.14002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruoka T, Gan E-S, Otsuka N, Shirakawa M, Ito T. Histone Demethylases JMJ30 and JMJ32 Modulate the Speed of Vernalization Through the Activation of FLOWERING LOCUS C in Arabidopsis thaliana. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022; 13:837831. 10.3389/fpls.2022.837831. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.837831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bender J. Cytosine methylation of repeated sequences in eukaryotesthe: the role of DNA pairing. Trends in biochemical sciences. 1998; 23:252–256. 1-0.10-16/s0968-0004(98)012 25–0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang S, Zhang A, Jin JB, Zhao B, Wang TJ, Wu Y, et al. Arabidopsis histone H3K4 demethylase JMJ17 functions in dehydration stress response. New Phytologist. 2019; 223(3):1372–1387. 10.1111/nph.15874. doi: 10.1111/nph.15874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu P, Zhang S, Zhou B, Luo X, Zhou XF, Cai B, et al. The Histone H3K4 Demethylase JMJ16 Represses Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2019; 31(2):430–443. 10.1105/tpc.18.00693. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Z, Wang X, Qiao K, Fan S, Ma Q. Genome-wide analysis of JMJ-C histone demethylase family involved in salt-tolerance in Gossypium hirsutum L. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2021; 158:420–433. 10.1016/j.plaphy.20-20.11.029. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Guo S, Xu Y, Li C, Zhang Z, Zhang D, et al. OsmiR396d-Regulated OsGRFs Function in Floral Organogenesis in Rice through Binding to Their Targets OsJMJ706 and OsCR4. Plant Physiology. 2014; 165(1):160–174. 10.1104/pp.114.235564. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.235564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie F, Yuan J-L, Li Y-X, Wang C-J, Tang H-Y, Xia J-H, et al. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Candidate Genes Associated with Leaf Etiolation of a Cytoplasmic Male Sterility Line in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica Rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(4):922. 10.33-90/ ijms19040922. doi: 10.3390/ijms19040922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, Yang S, Ren J, Ye X, jiang X, Liu Z. Genome-wide identification and functional analysis of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel gene family in Chinese cabbage. 3 Biotech. 2019; 9(3):1–14. 10.1007/s13205-019-1647-2. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1647-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pozsa‐Viejo L, Payá‐Milans M, San Martín‐Uriz P, Castro‐Labrador L, Lara‐Astiaso D, Wilkinson MD, et al. Conserved and distinct roles of H3K27me3 demethylases regulating flowering time in Brassica rapa. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2022; 45(5):1428–1441. 10.1111/ pce.14258. doi: 10.1111/pce.14258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng S, Hu H, Ren H, Yang Z, Qiu Q, Qi W, et al. The Arabidopsis H3K27me3 demethylase JUMONJI 13 is a temperature and photoperiod dependent flowering repressor. Nature Communications. 2019; 10(1):1303. 10.1038/s41467-019-09310-x. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09310-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zong W, Zhong X, You J, Xiong L. Genome-wide profiling of histone H3K4-tri-methylation and gene expression in rice under drought stress. Plant Molecular Biology. 2012; 81(1–2):175–188. 10.1007/s11103-012-9990-2. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9990-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen B, Ali S, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang M, Zhang Q, et al. Genome-wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of the JmjC domain-containing histone demethylase gene family in birch. BMC Genomics. 2021; 22(1):1–19. http://10.1186/s12864-021-08063-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, et al. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Molecular Plant. 2020; 13(8):1194–1202. 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian S, Wang Y, Ma H, Zhang L. Expansion and Functional Divergence of Jumonji C-Containing Histone Demethylases: Significance of Duplications in Ancestral Angiosperms and Vertebrates. Plant Physiology. 2015; 168(4):1321–1337. 10.1104/pp.15.00520. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Feng J, Liu W, Ren Z, Zhao J, Pei X, et al. Characterization and Stress Response of the JmjC Domain-Containing Histone Demethylase Gene Family in the Allotetraploid Cotton Species Gossypium hirsutum. Plants. 2020; 9(11):1617. 10.3390/plants9111617. doi: 10.3390/plants9111617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He M, Xu Y, Chen J, Luo Y, Lv Y, Su J, et al. MoSnt2-dependent deacetylation of histone H3 mediates MoTor-dependent autophagy and plant infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Autophagy. 2018; 14(9):1543–1561. 10.1080/15 548627.2018.1458171. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1458171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang D, Yang W, Pi J, Yang G, Luo Y, Du S, et al. Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization, and Expression Profiling of the Glutaredoxin Gene Family in Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis). Forests. 2023; 14(8):1647. 10.33-90/f1408 1647. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi N. Removal of H3K27me3 by JMJ Proteins Controls Plant Development and Environmental Responses in Arabidopsis. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021; 12:687416. 10.3389/fpls.2021.687416. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.687416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan W, Liu W, Liu Z, Zhu X, Wu J, Wang P. Genome-wide identification, expression analysis, and functional verification of the JMJ (Jumonji) histone demethylase gene family in pear (Pyrus bretchneideri). Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2023; 19(1):10. 10.1007/s11295-023-01586-x. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cigliano RA, Sanseverino W, Cremona G, Ercolano MR, Conicella C, Consiglio FM. Genome-wide analysis of histone modifiers in tomato: gaining an insight into their developmental roles. BMC Genomics. 2013; 14:1–20. 10.11 86/1471-2164-14-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niu H, Xia P, Hu Y, Zhan C, Li Y, Gong S, et al. Genome-wide identification of ZF-HD gene family in Triticum aestivum: Molecular evolution mechanism and function analysis. Plos One. 2021; 16(9): e0256579. 10.1371/journal. pone.025 6579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi Y, Shen Y, Ahmad B, Yao L, He T, Fan J, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of dirigent gene family in strawberry (Fragaria vesca) and functional characterization of FvDIR13. Scientia Horticulturae. 2022; 297:110913. 10.1016/j.scienta.2022.110913. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cannon SB, Mitra A, Baumgarten A, Young ND, May G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biology. 2004; 4(1):1–21. 10.1186/14-712229-4-10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Pan C, Long J, Bai S, Yao M, Chen J, et al. Genome-wide identification of the jumonji C domain- containing histone demethylase gene family in wheat and their expression analysis under drought stress. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022; 13:987257. 10.3389/fpls.2022.987257. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.987257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibraheem O, Botha CEJ, Bradley G. In silico analysis of cis-acting regulatory elements in 5′ regulatory regions of sucrose transporter gene families in rice (Oryza sativa Japonica) and Arabidopsis thaliana. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 2010; 34(5–6):268–283. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luan Y, Wang B, Zhao Q, Ao G, Yu J. Ectopic expression of foxtail millet zip-like gene, SiPf40, in transgenic rice plants causes a pleiotropic phenotype affecting tillering, vascular distribution and root development. Science China Life Sciences. 2010; 53(12):1450–1458. 10.1007/s11427-010-4090-5. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4090-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gago J, Grima-Pettenati J, Gallego PP. Vascular-specific expression of GUS and GFP reporter genes in transgenic grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Albariño) conferred by the EgCCR promoter of Eucalyptus gunnii. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2011; 49(4):413–419. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J, Yu C, Wu H, Luo Z, Ouyang B, Cui L, et al. Knockdown of a JmjC domain-containing gene JMJ524 confers altered gibberellin responses by transcriptional regulation of GRAS protein lacking the DELLA domain genes in tomato. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2015; 66(5):1413–1426. 10.10-93/jxb/er-u493. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crevillén P. Histone Demethylases as Counterbalance to H3K27me3 Silencing in Plants. iScience. 2020; 23(11):101715. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101715. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang H, He L, Song J, Cui W, Zhang Y, Jia C, et al. Cadmium-induced genomic instability in Arabidopsis: Molecular toxicological biomarkers for early diagnosis of cadmium stress. Chemosphere. 2016; 150:258–265. 10.101-6/j.chemosphere. 2016.02.042. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shafiq S, Zeb Q, Ali A, Sajjad Y, Nazir R, Widemann E, et al. Lead, Cadmium and Zinc Phytotoxicity Alter DNA Methylation Levels to Confer Heavy Metal Tolerance in Wheat. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(19):4676. 10.3390/ijms20194676. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Q, Sun W, Chen C, Dong D, Cao Y, Dong Y, et al. Overexpression of histone demethylase gene SlJMJ524 from tomato confers Cd tolerance by regulating metal transport-related protein genes and flavonoid content in Arabidopsis. Plant Science. 2022; 318:111205. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111205. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fan SK, Ye JY, Zhang LL, Chen HS, Zhang HH, Zhu YX, et al. Inhibition of DNA demethylation enhances plant tolerance to cadmium toxicity by improving iron nutrition. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2019; 43(1):275–291. 10.1111/ pce.13670. doi: 10.1111/pce.13670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xin X, Li P, Zhao X, Yu Y, Wang W, Jin G, et al. Temperature-dependent jumonji demethylase modulates flowering time by targeting H3K36me2/3 in Brassica rapa. Nature Communications. 2024; 15(1):5470. 10.1038/s41-467-024-49721-z. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49721-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]