ABSTRACT

Periampullary malignancies are uncommon and encompass a wide variety of tumors. Early and accurate biopsy-proven diagnosis is important because different malignancy subtypes warrant different management and treatment plans. We present a unique and rare case of periampullary lymphoma, initially presenting as acute pancreatitis.

KEYWORDS: periampullary lymphoma, acute pancreatitis, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, ampullary tumors, tumor resection

INTRODUCTION

Periampullary malignancy refers to neoplasia affecting the vicinity of the ampulla of Vater. Malignancies within the periampullary region encompass tumors affecting the pancreatic head, the distal common bile duct, as well as the duodenal ampulla. Although these tumors comprise only 5% of all gastrointestinal malignancies, they can be quite deadly because they are responsible for more than 30,000 deaths per year within the United States.1,2

As periampullary malignancies constitute a wide variety of tumors, it is of utmost importance to make a definitive diagnosis because different malignancy subtypes are associated with drastically different prognoses and treatment courses. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma has a morbid prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of 5%–15%,3 and the 5-year survival rate of duodenal carcinoma has been reported to be 27%.4 Meanwhile, the prognosis of ampullary carcinoma is typically less grim with 5-year survival rates of up to 40%–65%.5 In addition, the specific histopathology as well as the extent of tumor spread can both dictate the next steps, whether it be surgery, or a significantly less-invasive approach. We present an extremely rare case of periampullary lymphoma initially presenting as acute pancreatitis.

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old woman with a medical history of spontaneously cleared hepatitis B virus presented after 2 episodes of hematochezia in the setting of 3 days of postprandial abdominal pain. She described the abdominal pain as sharp, localized to the upper quadrants, and radiating to the back. In addition, she admitted to progressively worsening dyspnea on exertion over the previous month.

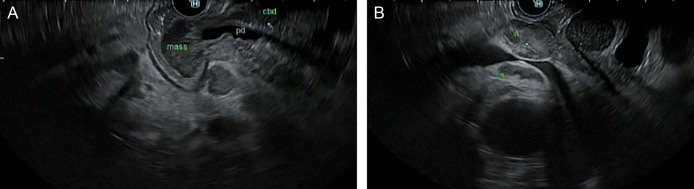

The patient was hemodynamically stable. Her white blood cell count was 7.45 K/μL, hemoglobin 11.5 g/dL, alkaline phosphatase 227 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 189 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 119 U/L, total bilirubin 0.2 mg/dL, and lipase 1,056 U/L. She denied any history of alcohol use, denied any family history of pancreatitis, was not on any medications, and her lipid panel as well as her calcium level were within normal limits. Ultrasound showed dilation of the common bile duct up to 1.7 cm with no cholelithiasis. Magnetic resonance imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed diffuse wall thickening and nodular enhancement of the ampulla bulging into the second portion of the duodenum (Figure 1). There was also diffuse pancreatic ductal and diffuse biliary ductal dilation with intrahepatic and extrahepatic ductal dilation and gallbladder and cystic duct distention. Portocaval, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was also present.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging revealing enhancement of the ampulla bulging into the duodenum along with diffuse biliary and pancreatic ductal dilation.

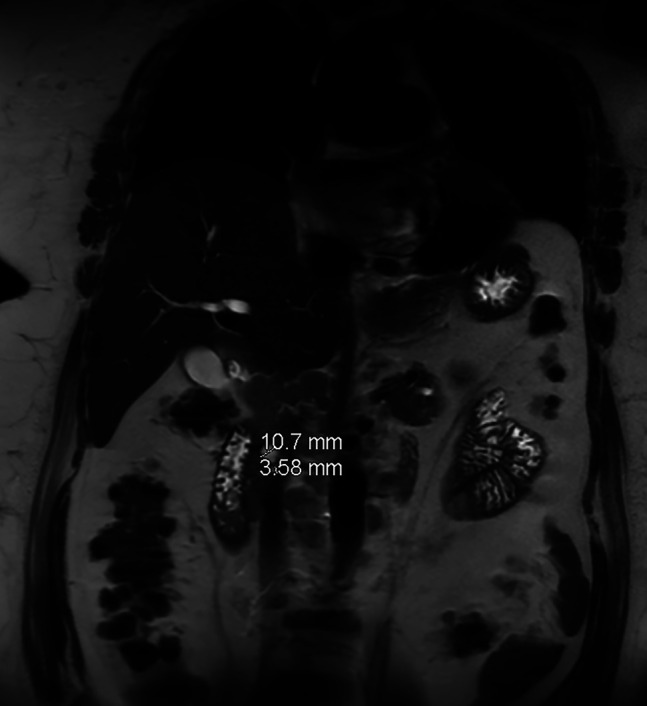

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids and bowel rest before advancing her diet slowly. She had no further episodes of hematochezia while she was hospitalized, her hemoglobin remained stable, and endoscopic evaluation was deferred. After symptomatic improvement, the patient was discharged and returned 3 weeks later for esophagogastroduodenoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound. A large infiltrative, ulcerated mass with bleeding was found at the major papilla (Figure 2). Endoscopic ultrasound revealed dilation in the gallbladder, intrahepatic bile ducts, and common bile duct to 16 mm (Figure 3). Biopsy of the mass was positive for germinal cell subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (Figure 4). Positron emission tomography–computed tomography showed the lesion within the ampulla to be with abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose-avidity as were the regional lymph nodes. The patient was tentatively scheduled for a Whipple procedure for treatment of a presumably aggressive cancer, which was ultimately deferred once the histopathology had resulted. The patient was instead, referred for chemotherapy instead of extensive surgery. As her biliary obstruction worsened, and the total bilirubin increased to 15.9 mg/dL, a biliary drain was placed by interventional radiology to optimize the patient for R-CHOP chemotherapy. Bone marrow involvement was found to be present on biopsy shortly thereafter. After 2 rounds of chemotherapy, the patient developed recurrent pneumonias, renal failure, and subsequently died 4 months after diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic view of the large polypoid, ulcerated mass at the major duodenal papilla.

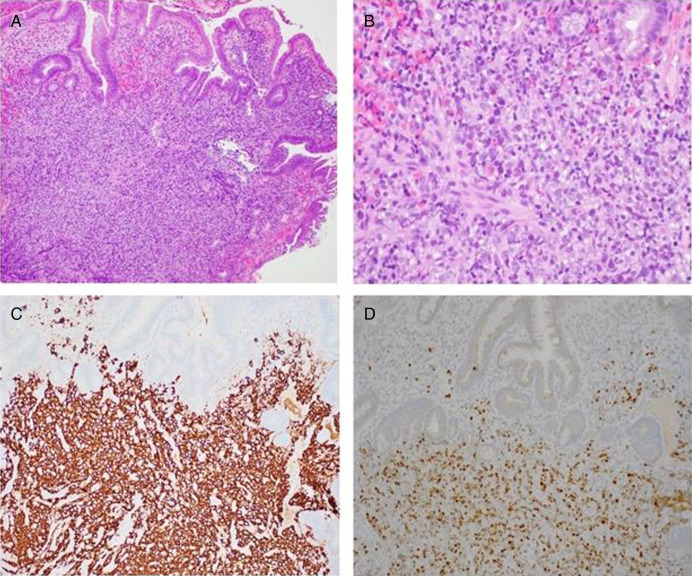

Figure 3.

(A) Endosonographic view of the periampullary mass invading into the pancreas and bile duct. (B) Endosonographic view of several round, heterogenous lymph nodes with well-defined margins in the porta hepatis region.

Figure 4.

Pathology slides of the biopsied ampullary mass revealed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (germinal center B-cell subtype) based on morphological, immunophenotypical, and genetic findings. Small intestinal mucosa showed infiltrate of large atypical lymphocytes (A: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), 100×; B: H&E, 400× magnification). By immunohistochemistry, these large atypical lymphocytes were positive for cluster of differentiation (CD) 20 (C: 200× magnification), B-cell leukemia/lymphoma (BCL6) (D: 200× magnification), CD10, and BCL2 with high proliferative index (Ki-67, 80%), but negative for CD5, multiple myeloma 1, BCL1, and myelocytoma (MYC). In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr encoding region was negative, and no evidence of MYC, BCL2-immunoglobulin heavy chain, and BCL6 gene rearrangements was detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization.

DISCUSSION

The most frequent site of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma within the gastrointestinal tract is the stomach. Malignant biliary obstruction occurs in only 1%–2% of patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and typically arises when nearby enlarged lymph nodes compress the biliary tract.6 It is rare for biliary obstruction to result from direct compression by a primary lymphoma. In fact, there are only a handful of case reports within the literature on periampullary lymphoma. Of these reports, follicular lymphomas are most common, followed by marginal zone and mantle cell lymphomas.7 It is even rarer for DLBCL to be diagnosed within the periampullary region. The uniqueness of our case is amplified by the fact that our patient represents the second known case of a primary periampullary DLBCL presenting as acute pancreatitis.8

An accurate diagnosis is key to optimal management. Although locally invasive cholangiocarcinomas, pancreatic and duodenal adenocarcinomas, and ampullary carcinomas are managed with resection, lymphomas are primarily treated with chemotherapy.9,10 In fact, resection is not indicated for lymphomas in the absence of intestinal obstruction, severe hemorrhage, or perforation.11 Unfortunately, many of the cases within the literature document pancreaticoduodenectomies being performed on patients. In these cases, surgery was performed because of technical challenges hindering biopsy, if biopsy results were indeterminate, or if treatment plans were solely based on clinical presentation and imaging without tissue biopsy.12 In our patient, the general surgery service was consulted immediately after the periampullary mass was found on esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Although surgical planning for resection was initiated, it was discontinued once the biopsy resulted in lymphoma. Unnecessary resection of periampullary lymphomas should be avoided because it is associated with an increase in both mortality and delay of chemotherapy initiation.13 Obtaining the diagnosis through tissue biopsy is imperative to ensure appropriate treatment and may prevent a complicated surgery with adverse outcomes.

Standard treatment of periampullary DLBCL is no different than that of DLBCL in other locations. A regimen of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab is the treatment of choice. Although our patient's biliary obstruction was treated with biliary decompression before chemotherapy initiation, in general, periampullary lymphomas with biliary obstruction can be treated strictly with regimen of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab.14 Previously untreated DLBCL carries a favorable prognosis, with 5-year survival rates ranging between 60% and 95%.15 Unfortunately for our patient, bone marrow infiltration contributed to a poor prognosis, and the patient died after only 4 months.

DISCLOSURES

Author contributions: BR Abramowitz and N. Ridout substantially contributed to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, the drafting of the manuscript, and the editing of the manuscript. H. Attia, Z. Li, and PJ Hammill substantially contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, the drafting of the manuscript, and the editing of the manuscript. EB Grossman substantially contributed to the conception and design of the work, the drafting of the manuscript, and the editing of the manuscript and is the article guarantor. All authors gave their final approval of this version of the manuscript to be published.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

Contributor Information

Nicholas Ridout, Email: nicholas.ridout@downstate.edu.

Hagar Attia, Email: hagar.attia@downstate.edu.

Zhonghua Li, Email: liz@nychhc.org.

Patrick J. Hammill, Email: patrick.hammill@downstate.edu.

Evan B. Grossman, Email: evg9007@med.cornell.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ross WA, Bismar MM. Evaluation and management of periampullary tumors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6(5):362–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez-Cruz L. Periampullary carcinoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA. (eds.). Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Zuckschwerdt: Munich, Germany, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhan HX, Xu JW, Wu D, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Cancer Med. 2017;6(6):1201–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchbjerg T, Fristrup C, Mortensen MB. The incidence and prognosis of true duodenal carcinomas. Surg Oncol. 2015;24(2):110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin J, Wang H, Peng F, et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative Naples prognostic score on short- and long-term outcomes after pancreatoduodenectomy for ampullary carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2021;10(6):825–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lokich JJ, Kane RA, Harrison DA, McDermott WV. Biliary tract obstruction secondary to cancer: Management guidelines and selected literature review. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5(6):969–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trivedi P, Gupta A, Pasricha S. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of ampulla of vater: A rare case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43(2):340–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada R, Sakuno T, Inoue H, et al. A case of duodenal malignant lymphoma presenting as acute pancreatitis: Systemic lupus erythematosus and immunosuppressive therapy as risk factors. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11(4):286–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facer BD, Cloyd JM, Manne A, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes for patients with ampullary carcinoma who do not undergo surgery. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(14):3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cillo U, Fondevila C, Donadon M, et al. Surgery for cholangiocarcinoma. Liver Int. 2019;39(Suppl 1):143–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yildirim N, Oksüzoğlu B, Budakoğlu B, et al. Primary duodenal diffuse large cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma with involvement of ampulla of Vater: Report of 3 cases. Hematology. 2005;10(5):371–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lokesh KN, Lakshmaiah KC, Premalata CS, Lokanatha D. Periampullary lymphoma masquerading as adenocarcinoma. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013;4(2):155–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stagnitti F, Coletti M, Corona F, et al. Small intestine tumors: Our experience in emergencies [in Italian]. G Chir. 2003;24(1-2):34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dudgeon DJ, Brower M. Primary chemotherapy for obstructive jaundice caused by intermediate-grade nonHodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 1993;71(9):2813–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang WR, Liu X, Zhong QZ, et al. Prediction of 5-year overall survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma on the pola-R-CHP regimen based on 2-year event-free survival and progression-free survival. Cancer Med. 2024;13(1):e6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]