Abstract

Metastatic disease and cancer recurrence are the primary causes of cancer-related deaths. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) are the driving forces behind the spread of cancer cells. The emergence and development of liquid biopsy using rare CTCs as a minimally invasive strategy for early-stage tumor detection and improved tumor management is a promising advancement in recent years. However, before blood sample analysis and clinical translation, precise isolation of CTCs from patients’ blood based on their biophysical properties, followed by molecular identification of CTCs using single-cell multi-omics technologies is necessary to understand tumor heterogeneity and provide effective diagnosis and monitoring of cancer progression. Additionally, understanding the origin, morphological variation, and interaction between CTCs and the primary and metastatic tumor niche, as well as and regulatory immune cells, will offer new insights into the development of CTC-based advanced tumor targeting in the future clinical trials.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Cancer metastasis, Circulating tumor cells, Disseminated tumor cells, Liquid biopsy, Targeted therapy

Background

In 2024, it is projected to be 2,001,140 new cases of cancer and 611,720 deaths from cancer in the USA. Incidence rates for cancers of the breast, pancreas, and uterus increased by 0.6–1% per year between 2015 and 2019. For cancers of the prostate, liver, kidney, human papillomavirus-associated oral cancers, and melanoma, the rate increased by 2–3% per year [1]. Despite advances in cancer treatment, metastasis is still the number one cause of death from cancer around the world [2]. Metastasis is the primary factor causing mortality in colorectal cancer (CRC) [3] and breast cancer patients [4]. A significant barrier to improving outcomes in patient with advanced solid tumor is the limited ability of current clinical diagnostic tools to predict metastasis and detect minimal residual disease (MRD) [5]. This is often the case due to inadequate diagnostic cutoffs, sampling biases caused by tumor tissue or biomarker heterogeneity and limited sampling of metastases [6]. Moving forward, oncologists have introduced liquid biopsy using blood samples from tumors as an alternative, real-time, and minimally invasive method for early detection, prognosis, and prediction of response to anticancer drugs [7]. Tumor-derived blood samples contain analytes such as circulating tumor cells (CTCs), cell-free DNA (cfDNA), cell-free RNA (cfRNA), and exosomes that provide a promising tool for tailoring the management of each patient with advanced cancers [8, 9].

Naturally, invasive primary tumors and metastatic tumors shed CTCs into the bloodstream to seed distant secondary sites and induce metastases. Therefore, isolating CTCs from blood samples using technological tools and analyzing them according to their established cutoff number and molecular profile could be interesting biomarkers for monitoring cancer patients [10]. In addition, targeting CTCs in vivo provides more opportunities to expand their clinical utility in the field of cancer treatment [11].

However, realizing the full potentials of CTCs and applying them in clinical settings is met with technological and biological challenges that must be addressed. Addressing these challenges and promoting translational applications demands a deep understating of the origin and formation of CTC populations, their interactions with tumor vasculature, stromal and immune cells in the bloodstream, as well as their presence in the niche and tumor microenvironment as disseminated tumor cells (DTCs). This review discusses these topics.

CTC biology and tumor metastases

Although each invasive tumor releases thousands of CTCs daily into the bloodstream; however, most of them attach and die due to both mechanical evidences (e.g., shear forces and oxidative stress) and biological reactions (e.g., immune system responses). Therefore, CTCs have a short half-life in bloodstream and need to employ survival mechanisms, such as activating immune evader pathways, more importantly, forming cluster phenotypes (groups of > 2 CTCs). Clustering protects CTCs against attacks from antitumor immune cells, facilitates their rolling in blood vessels, and even allows them to use platelets or neutrophils as escorts to seed and colonize distant organs, eventually contributing to metastasis [12, 13] (Fig. 1). Previous studies have shown that potent CTC cluster may originate from (i) assembling in the primary tumor due to the density of the extracellular matrix (ECM) before intravasation and through the upregulation of mesenchymal traits, as confirmed in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) necessary for tumor metastasis [14], (ii) overexpression of cell surface adhesion molecules and induction of adherent junctions by plakoglobin and keratin 14 [15, 16], (iii) remodeling of ECM or tumor architecture to clear a path, collective invasion provided by the upregulation of stemness factors (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2) [17], and (iii) the formation of CTC clusters in bloodstream through the coupling of CTC-expressing heparanase-mediated expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) as cell–cell adhesion molecules in the focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-Src-paxillin-dependent pathway [18].

Fig. 1.

Models of CTC invasion, cluster formation, intravasation, and induction of tumor metastasis are crucial in understanding cancer progression. The immune suppressive tumor microenvironment, along with stromal cells such as CAFs at the primary site, play significant role in promoting tumorigenesis. In tumors prone to metastasis, EMT allows single CTCs to detach from the primary tumor lesion. This is followed by the upregulation of stemness factors (OCT4, NANOG, SOX2), ECM remodeling, and upregulation of cell–cell interaction mediators, all of which support collective invasion and migration of tumor cells. After intravasation, platelets and neutrophils provide cluster survival against shear stress and antitumor immune cells such as T and NK cells. Following CTC extravasation and dissemination to distant organs, they may enter a dormant phase for an unknown period or induce micro and macro colonization, ultimately leading to tumor metastasis. Abbreviations: CAF, cancer-associated fibroblasts; CTC, circulating tumor cell; DTCs, disseminated tumor cells; ECM, extracellular matrix; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; TAM, tumor-associated macrophages; Treg, regulatory T cell

In comparison to single CTCs, CTC clusters are experiencing hypoxia [19], demonstrating hybrid epithelial-mesenchymal features [20], and expressing more adhesion-dependent survival signals that inhibit the anoikis. They also overexpress transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), increasing their ability to survive. Their presence in the bloodstream is correlated with elevated circulating levels and is associated with worse prognosis [21, 22]. Endothelial cells express N-cadherin or galectin-3, which interact with multiple areas of CTC clusters, facilitating their extravasation [23]. CTC clusters appear to have a lower turnover rate in the bloodstream compared to single cells, which may enable more efficient metastasis extravasation [24]. Platelets associated with clusters can secrete TGFβ that subsequently induces EMT and facilitates the extravasation of CTC clusters [25]. In addition, these platelets release granules containing ATP, which act as potent disruptors of endothelial junctions and may therefore facilitate CTC intravasation and extravasation [26]. CTCs overexpress galectin-4, which binds to red blood cells (RBCs) to form CTC-RBC clusters that enable CTCs to roll steadily along the vessel wall at low flow rates, increasing their adhesion affinity to the endothelial wall and facilitating extravasation [27, 28].

In addition, the expression of cancer stem cell (CSC) markers such as BMI1, CD44, CD133, ALDH1, DLG7, and tendency to cluster (spheroid formation in CSCs) in invasive CTCs indicate the possibility that they originate form CSCs, which are known as metastasis-initiating cells (MICs) [29–31]. Like CSCs, stem cell-like CTCs demonstrate EMT, self-renewal, and more aggressive properties, supporting their survival and resistance to anticancer therapies, ultimately contributing to the formation of distant metastases [32]. Interestingly, in distant organs, the colonized CTCs, known as disseminated tumor cells (DTCs), exhibit dormancy and recurrence, consistent with potentials of CSCs [33]. Overall, EMT and clustering provide a survival advantage for a small fraction of CTCs, protecting them from cell detachment-induced apoptosis and shear forces, thereby promoting of metastasis. In addition, clustering formation protects CTCs from immune assault, as discussed in the following sections.

CTC survival-promoting interactions

During EMT and the formation of invadopodia, at the molecular level, the hypoxic solid tumor environment results in the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), which subsequently induces the expression of L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1CAM) [34] and C-X-C chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) [35]. Both L1CAM and CXCR4 facilitating the biding of CTCs to endothelium and their intravasation [34]. Before invasion and intravasation, CTCs also bind to perivascular macrophages, which further increase endothelial permeability through the production of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) [36]. Stromal cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) interact with invasive tumor cells at the primary site to reduce shear stress and augment collective invasion, while at the secondary site, they provide TME to CTC seeding and colonization [37]. Indeed, CAF-CTC heterotypic clusters indicate higher CTC metastatic potential in vivo [38].

Once CTCs enter the bloodstream, they can overexpress antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL-2 and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1) ligand 1 (PD-L1) or CD47, which protect them against cell death induced by apoptosis and immune cells [39, 40]. In addition, CTCs can be masked by platelets expressing MHC I or neutrophils, which provide CTCs with survival advantages by inhibiting immune clearance by natural killer (NK) cells and CD8 T cells, respectively [41, 42]. Similar to neutrophils, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and macrophages can provide survival advantages for CTC clusters and protecting them from immune surveillance [43] [44] (Fig. 1).

In addition to tumor-supportive immune or stromal cells, recent research has demonstrated that CTC- or tumor-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) support tumor metastasis by shedding CTCs, protecting them in circulation, and promoting their localization in distant sites to induce metastasis [45]. EVs carry TGF-β1 as an EMT promoting factor, or miRNAs that regulate key genes in the EMT/Wnt pathways, such as miR-19b-3p, and miR-10527-5p, and ECM remodeling-related MMP enzymes, all of which facilitate CTC shedding from the primary tumor [46–48]. In addition, EVs carry tumor vascular permeable factors that compromise endothelial junction integrity and facilitate the processes of CTC intravasation and extravasation. In the circulation, tumor-derived EVs contain CD63, PD-L1, and tissue factor (TF), which activate platelets to protect CTCs from shear stress and immune surveillance mediated by T cells, NK cells, and B cells [49, 50]

In distant organs or secondary sites, CTC clusters trap in small capillaries. They express ligands and receptors to interact with tumor-associated endothelial cells (TECs) in the vascular wall, mimicking the diapedesis of leukocytes for extravasation [51]. TEC-derived VEGF and other inflammatory mediators further facilitate vasculature permeability and CTC extravasation [52]. Platelets and neutrophils also support extravasation by creating a pro-inflammatory condition and trapping CTCs in the TEC wall, inducing vascular leakiness [12, 53].

After exiting the bloodstream, CTC metastatic colonization depends on the condition of the TME. Physical and biological factors determine whether metastasis is induced or if dormancy is promoted in DTC for an unknown period of time. The heterogeneity of CTCs in the terms of genetic, phenotypic, metabolic, and other factors ensures their survival throughout the metastatic process. For example, enhanced mitophagy and downregulation of surface biomarkers (e.g., HER2) protect CTCs from ROS-mediated oxidative stress and immune cells identification, respectively [54, 55]. Overall, the phenotypic plasticity and heterogeneity of CTCs impact their ability to acquire adaptive phenotypes for metastasis.

CTC clinical applications

CTC enrichment

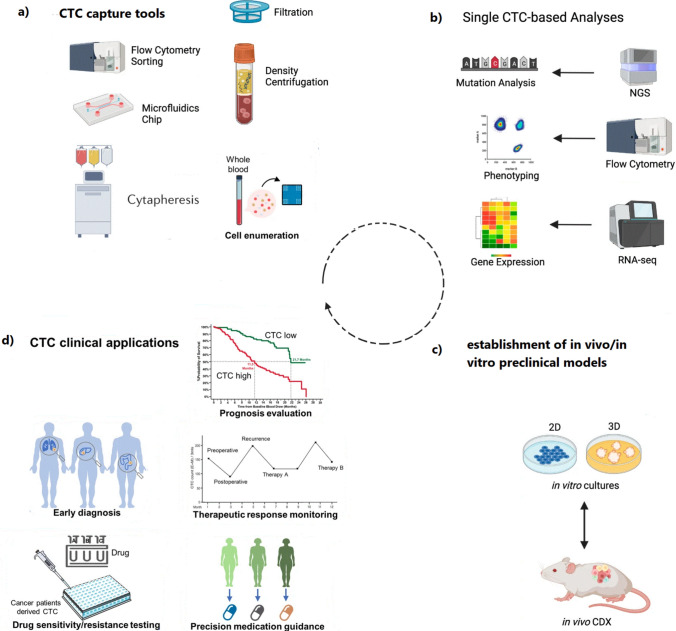

In comparison to invasive tumor tissue biopsy, utilizing liquid biopsy for phenotypic and molecular analysis of CTCs with metastatic potential may serve as an ideal source of biomarkers for real-time clinical applications. However, before deciding, CTC analysis requires pure capturing these cells from the blood samples using innovative technologies and then assessing viable CTCs at molecular and functional levels. Capturing methods are classified based on CTC biophysical and biological markers (Fig. 2a). CTCs that overexpress specific antigens (Table 1) enable positive immunomagnetic selection and isolation of CTCs from blood samples that have been pretreated with a hemolysis solvent.

Fig. 2.

a Viable circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are isolated or enriched from peripheral whole blood using techniques such as FACS, MACS, filtration, density gradient centrifugation, and microfluidic devices. b These purified CTCs can then be characterized using single-cell analysis technologies (single-cell genomic/transcriptomic/proteomic analysis) or c used for establishment of in vitro 2D culture (low adherent) or 3D culture (tumoroids) and in vivo CDX. d Examples of clinical applications of CTCs. Abbreviations: CDX, CTC-derived xenografts; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; MACS, magnetic-activated cell sorting. Figure 2 is redesigned from references [88] and [89]

Table 1.

Molecular markers of CTCs in human solid tumors

| Type of cancers | Specific marker(s) | EMT marker | Epithelial markers | Stemness marker | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | HER2, ER, AR | Vimentin, Twist, N-cadherin, β-catenin | EpCAM/CK8,18,19 and E-cadherin | CD44, CD24−, and ALDH1 | [56, 57] |

| Bladder cancer | CK, EGFR, MUC7 | – | EpCAM/CK8,18,19 | CD44v6 | [58–60] |

| Colorectal cancer | PI3K α, CEA, PRL3 | Vimentin, Twist, SNAI1, Plastin3 | EpCAM/CK8,18,19 | Wnt, CD44 | [22, 61] |

| Gastric cancer | MT1-MMP | N-Cadherin | EpCAM/CK19/CK20 | CD24, CD44v6 | [62, 63] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | GPC-3, ASGPR | Vimentin, Twist | EpCAM/CK8,18,19 | NANOG, CD44, and CD133 | [64, 65] |

| Pancreatic cancer | GAS2L1, CA19.9 | Vimentin, Twist, KLF8 | EpCAM/CK8,18,19 | CD44 | [66, 67] |

| Small-cell lung cancer | DLL3 | Vimentin | EpCAM/CK8,18,19 | CD44v6 + / CD31- | [68, 69] |

ASGPR, asialoglycoprotein receptor; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DLL3, delta-like ligand-3; GPC-3, glypican-3; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2; PRL3, Phosphatase of Regenerating Liver 3; MT1-MMP, membrane type1-matrix metalloproteinase

Immune capture of CTCs is performed using anti-CTC antigen antibodies that are immobilized on magnetic beads using magnetic-activated cell separation (MACS) technology, magnetic platforms, and nanowires for in vivo capturing of CTCs after intravascular establishment. EpCAM, EGFR, pan-CK, and CD45 are examples of CTC antigens that are utilized for immune capture of CTCs with acceptable sensitivity and specificity. The FDA-approved CellSearch system and AdnaTest CTC Select use EpCAM-based immunomagnetic capture of CTCs.

CTCs can also be enriched based on their physical criteria such as size (filter-based devices), charge (capture surfaces), density (density gradient centrifugation), or elasticity (microfluidic systems) (Fig. 2a). The pure selection and enrichment of CTCs is achieved through the combination of antigen-dependent and independent technologies [70]. In addition, in vivo capturing of CTCs using nanowires (e.g., anti-EpCAM antibodies decorated on CellCollector, Germany) reduces manipulation, contamination, and stress associated with in vitro isolation of CTCs. More importantly, CellCollector addresses the low number of CTCs in blood samples that require a high volume of blood samples, which is limited in some patients. Similar to CellCollector, cytapheresis is another strategy that combines antigen-dependent selection and provides the ex vivo enrichment of low CTCs from the whole blood volume of patients. The conventional method of isolation and identification of CTCs is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overall methods for isolating CTCs

| Isolation principle | Example technology | CTC/cancer type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size-based methods | |||||

| Membrane microfilters | ISET |

Non-small cell lung, colorectal cancers, melanoma |

+ High sensitivity + Isolation of CTC clusters |

-High loss of small cells | [71] |

| FAST | Colorectal, breast, stomach, lung cancers | KRAS mutation analysis | + High sensitivity | -High loss of small cells | [72] |

| Microfluidic technologies | ieSCI-chip | Breast cancer |

+ High capture efficiency + Fast isolation and processing |

-Limited sample volume -Slow flow rate |

[73] |

| Microfluidic technologies | Labyrinth | Non-small cell lung, liver cancers |

+ Isolation of clusters + Depletion of more than 95% of leukocytes + High cell viability |

-High loss of small cells | [74] |

| Immuno-affinity strategy (cell biological properties) | |||||

| Negative selection | RosetteSep | Liver, breast cancers |

+ Isolation of CTC clusters + Fast isolation (40 min) + CTC marker-free isolation |

-High number of untargeted cells | [75] |

| Positive selection | CELLSEARCH® (Janssen Diagnostics) | Metastatic breast cancer, Colorectal, Prostate |

+ FDA-approved + marker's dependence + Most clinically validated capture technique + high Specificity |

-Low purity of captured CTC -low Sensitivity -cannot Identify EMT |

[76] |

| Positive selection | MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec) |

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Breast (HER2 +) |

+ Identifies EpCAM negative CTCs + Can combined with leukocytes depletion |

-Expensive -Low cell viability -Dependence on expressed proteins -Hard to automate |

[77] |

| Functional Assays | |||||

| Secretory Protein | EPISPOT | Breast cancer |

+ High sensitivity / specificity + Independent Ag phenotype + Allows CTC quantifying |

-Just allows CTC detection based on protein secretion | [78] |

| Adhesive CTC | Vita-Assay (Vitatex) | Prostate | + Allows detection of invasive n CTC | -Low purity | [79] |

| Dielectrophoresis | |||||

| Dielectrophoretic cage | DEPArray™ (Silicon Biosystems) | Breast | Isolation of single CTCs for downstream gene analysis | -High loss of small cells | [80] |

| DEP-FFF | ApoStream® (ApoCell) | Breast | + Independent of EpCAM + useful for viability analysis and culture | Processes more than 10 mL/h | [81] |

| Combined methods | |||||

| Positive selection and microfluidic approaches | RBC-chip | Colorectal cancer |

+ High sensitivity and specificity + High viability |

-Isolation of only EpCAM-positive CTCs | [82] |

| Positive selection and microfluidic approaches | Herringbone-Chip | Lung cancer |

+ One step method + High capture efficiency + Isolation of clusters |

-Isolation of only EpCAM- and EGFR-positive CTCs | [83] |

| Non-microfluidic approaches and cell biological properties | AccuCyte-RareCyte/PIC & RUN | Prostate, breast, lung cancers |

+ High viability + High capture efficiency + provide CTC culturing |

-The presence of false-positive CTCs | [84] |

CTC analysis and tumor detection and prognosis

Downstream analysis of CTCs includes direct drug phenotyping, the creation of CTC-derived xenograft models, and multi-omics interrogations at the single-cell level (e.g., epigenomic, proteomic, genomic, and transcriptomic) [9] (Fig. 2b and c). Epigenetic comparison of CTCs and CTC clusters at the single-cell level revealed that the hypomethylation profile of CTC clusters on the binding sites for OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and SIN3A correlates with stemness, metastatic spreading, and poor prognosis in breast cancer [17]. Therefore, remodeling these sites using Na + /K + ATPase inhibitors resulted in the dissociation of CTC clusters and suppression of metastasis, introducing potential therapeutic targets on a genome-wide scale. Genomic profiling using single-cell genome sequencing can indicate high-throughput intra-tumor heterogeneity, providing new biological insights into tumor formation [85]. In addition, mass spectrometry and microfluidic chambers are utilized for the analysis of proteins secreted by single CTCs and CTC clusters, indicating the potential for providing functional CTC profiling in cancerous samples [86, 87].

Detection of CTCs in peripheral blood has been studied extensively in major solid tumors such as breast, prostate, colorectal, and small cell and non-small-cell lung cancers. These studies have focused on the prognostic value and the ability to predict disease-free and overall survival [9]. Elevated CTC counts (five or more CTCs per 7.5 mL of blood) or changes in CTC numbers in response to therapy have been associated with worse prognosis and can help predict progression-free survival (PFS), disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS) [90].

In addition, the profile of CTC biomarkers presents the benefit of therapy choice. The randomized phase III DETECT III trial (NCT01619111) compared lapatinib in combination with standard therapy versus standard therapy alone in patients with initially HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (MBC) and HER2-positive CTCs. The results indicated that patients with HER2-negative MBC and HER2-positive CTCs benefit from additional HER2-targeted therapy with lapatinib [91].

Better than single CTCs counting, evaluation of CTC clusters can improve early cancer detection [92], monitoring of response [93], prognostic value [94], detection of MRD that determined by the clearance of CTC clusters after standard therapy [94, 95], and prediction of tumor relapse in late stages of disease [96]. These factors are all helpful in guiding therapeutic decisions. Comprehensive analysis of the size or quantity of CTC clusters and associated peripheral blood cells (PBCs) could provide valuable insights into a biomarker-driven strategy for further management after the completion of standard therapy. This analysis could also aid in the risk stratification of patients with unresectable late-stage metastatic tumors [95, 97]. Beyond CTC enumeration, the integration of single-cell multi-omics approaches provides characterization of CTCs at the single-cell level. This approach also sheds light on their role in inter-/intra-tumor heterogeneity, mechanisms of therapeutic resistance, and the discovery of rare CTCs that drive tumor progression and metastasis (Fig. 2b).

However, CTCs are relatively rare in most cancer patients. Functional characterization of rare CTCs requires in vitro or ex vivo expansion, which can be achieved through low-adherent 2D culture or CTCs cultured in ultralow attachment plates to support 3D culture. Alternatively, CTCs can be seeded in a 96-well plate under hypoxic conditions to support long-term CTC culture [98]. Once CTCs reach 90% confluence, they can be collected for molecular characterization [99], used to create lysate in DC vaccines [100], or utilized for developing CTC-derived xenografts (CDX) to better understand cancer biology and identify potential prognostic markers and therapeutic targets [101] (Fig. 2c). These approaches pave the way for personalization of therapeutic option as discussed in pervious reviews [9, 102, 103]) (Fig. 2d).

Target CTCs in vivo

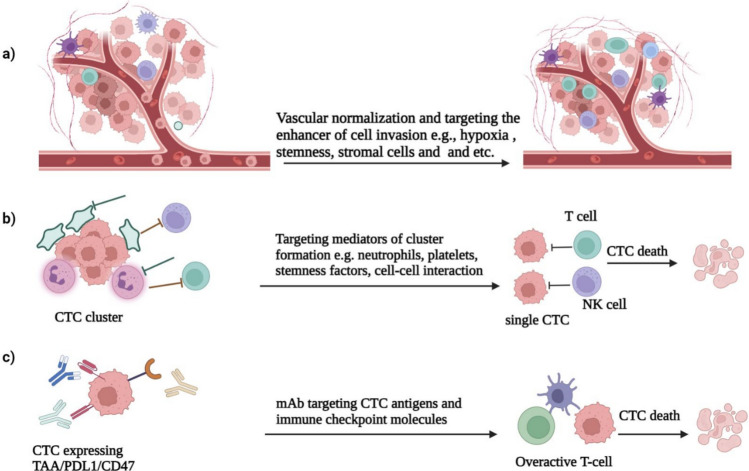

Targeting the primary lesions but not the metastatic tumor, and ignoring the CTCs or DTCs, has resulted in the failure of current therapies such as surgery or systemic chemo radiotherapy for advanced human cancers [104]. Therefore, targeting CTCs before dissemination may interrupt the metastatic progression. Nevertheless, this strategy should be implemented at all stages of metastasis, from CTC shedding, cluster formation, CTCs in the bloodstream, and DTCs in secondary tumors at distant sites (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The approaches for targeting CTCs in vivo. a Inhibition of cancer cell invasion and intravasation can be achieved through vascular normalization and targeting of hypoxia, stemness factors, and tumor-supportive immune cells or stromal cells in the solid tumor microenvironment. b Blocking cellular interactions with platelets or neutrophils that support cluster formation and survival can lead to the dissociation of CTC clusters, producing immune-prone single CTCs for eradication in the systemic circulation. c Targeting CTC survival can be down using small molecules or monoclonal antibodies (mAb) targeting tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) such as EpCAM, HER2, PSA, and immune checkpoint molecules (PD1, PD-L1, CTLA4, CD47) on CTCs or T cells. This reprograms of antitumor immune responses and promotes immune clearance of CTCs in both the bloodstream and their niches in distant sites

As mentioned above, hypoxia supports collective invasion of tumor cells and intravasation of CTC clusters. Targeting hypoxia or inducing tumor vascular normalization by proangiogenic agents can lead to reduced CTC cluster formation, shedding rate, and suppression of metastasis in animal models [19]. Integrin, cell surface glycoproteins [105], and heparanase (HPSE)-induced hemitropic cluster formation (HPSE upregulates cell–cell contact mediators such as ICAM-1) [18], and targeting these mediators has resulted in clustering suppression and decreased CTC induced tumor metastasis. In addition, disrupting heterotypic cell–cell interactions that occur in the bloodstream and provide the clusters survival, such as CTC-platelet [106] or CTC-neutrophil clusters [12], could reduce the metastatic potential in ovarian and breast cancers (Fig. 3b).

Regarding surface biomarker targeting, CTCs that overexpress antigens and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can be targeted using anti-EpCAM, HER2 PD1, PD-L1, and CTLA4 antibodies. These antibodies mediate T cell killing as a single-agent therapy, or can be improved by dual targeting CTC antigen and ICIs. Dual targeting of EpCAM or HER2 with neutralizing antibodies in combination with ICIs has been shown to eradicate CTCs in models of human colorectal cancer [107] and breast cancer [108] (Fig. 3c). Inspired by the physical interaction between platelets and CTCs that help them evade immune elimination, Li et al. genetically engineered platelets to express tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL). This induced apoptosis in metastatic tumor cells in the bloodstream and reduced systemic prostate cancer metastases [109].

In addition to monoclonal antibodies targeting surface tumor antigens, CTCs could also be targeted by engineered chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells. This was most recently indicated by EpCAM-specific CAR-T cells, which were successful in eliminating CTCs that have intravasated into circulation in a surgery-induced tumor metastasis model in immunocompetent mice [110]. Granzyme B (GrB)-based CAR-T cells were also developed to target membrane-bound HSP70 (mHSP70), effectively inhibiting cancer metastasis in spontaneous metastasis models without causing any apparent toxic effects [111]. CAR-T cells targeting other tumor antigens, such as HER2, PSCA, CEA, TAG-72, and CBT-511, have been developed and are currently being evaluated in preclinical and clinical trials for solid tumors [112, 113]. The promising antitumor activity of these tumor antigen-specific CAR-T cells in preclinical investigations led to the study of the therapeutic effect of EpCAM CAR-T cells in clinical trials (NCT02915445) involving 12 patients with EpCAM-positive epithelial tumors. The result showed that two patients had a partial response, three patients had more than 23 months of progression-free survival (PFS), and one patient experienced a 2-year PFS with detectable EpCAM CAR-T cells 200 days after infusion [114].

However, the administered antitumor agents cannot distinguish disease-relevant CTCs from disease-irrelevant CTCs in the bloodstream, which may be better targeted toward colonized tumor cells at metastatic sites. Various biophysical, biochemical, and immune barriers limit the delivery and therapeutic effects of chemotherapies in the mechanoenvironment of cancer metastasis [115]. Using cell-based vectors (e.g., MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells) with the potential for homing to cancer metastases is a novel platform for both tumor diagnostics and therapies [116]. CTC offer a super benefit with self-homing or self-seeding properties. CTCs armed with both a reporter gene and a cytotoxic prodrug gene therapy, converting nontoxic 5′-fluorocytosine (5FC) into the cytotoxic compound 5′-fluoruridine monophosphate, have been used as a theranostic platform in metastatic disease. This approach resulted in tumor lysis and a reduction of tumor burden in a mouse model, as demonstrated by bioluminescence imaging [117]. Therefore, distinguishing metastasis-relevant CTCs, understanding CTC heterogeneity, and determining the molecular interactions between immune or stromal cells, neutrophils, and CTCs, expands the metastatic potential of CTCs. This provides a rationale for targeting invasive single CTCs or CTC clusters in the treatment of human cancers.

Limitations of the routine analysis of CTCs and prospective approaches

Interestingly, the circadian rhythm may have an effect on CTC release and metastatic dissemination in breast cancer. For example, during sleep or rest, melatonin (and other unknown mechanisms) may increase the CTC count in the bloodstream [118], highlighting the importance of the time of sampling for analyzing CTC. This can influence the prognostic and predictive value, as well as decision-making in the clinic.

Beyond enumeration, the rhythmicity of CTC release into the bloodstream can guide time-controlled clinical trials of chemotherapy by utilizing available therapeutic agents to achieve maximum effectiveness during peaks of CTC generation. Efforts have been made to address the low number of CTCs in blood samples, with cytapheresis and nanowire technologies explored for ex vivo and in vivo capturing of CTCs from large blood volumes, respectively. However, the implementation of these approaches in routine clinical practice may be limited due to their invasive natural and the poor vascular health of heavily treated cancer patients [119, 120].

Since tumor-draining vessels contain higher number of CTCs compared to peripheral locations, it is important to develop attractive liquid biopsy approaches that have access to these vasculatures, especially in patients with early-stage cancer who have undergone surgery [121]. In addition to enumeration, during the capturing process, some CTCs may become loose or deformed, necessitating rapid identification and automated downstream analysis of CTCs [70].

Upon metastasis, the EMT process results in the downregulation of EpCAM and upregulation of mesenchymal markers in CTCs, limiting the application of EpCAM-based CTC enrichment [122]. Therefore, there is a need to develop EMT-independent methods capturing CTCs. In addition, issues such as clogging formation and the requirement of large blood samples have restricted the isolation of CTCs using size/filter-dependent systems (e.g., ISET, MetaCell system, ScreenCell Cyto, and CellSieve) and have also affected their viability in density-based centrifugation.

CTCs are informative sources of biomarkers, even for personalized medicine (Fig. 2). However, presenting precise functional assays requires improvement of optimized culture methods and efficient CTC-derived animal models [70]. In addition, metastasis-targeting agents are used in the advanced stages of tumors, while CTC shedding, dissemination, and metastasis may have already occurred even in the early stages and during tumor formation [123]. The timing and mechanism of CTCs and their clusters entering the bloodstream, their organotropism, as well as dormancy or induction of micro/macrometastasis remain elusive, and this aspect warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

Analysis of liquid biopsy-associated CTC analytes at the single-cell level has the potential to revolutionize cancer management in the future. However, to broaden its application in the clinic and across the cancer spectrum, innovative study designs will likely be required to address unanswered questions about CTC biology and enumeration validity in patients with advanced cancers. New bioengineering techniques, such as implantable, rapid, automated, and noninvasive microchips, are being developed to enable the simultaneous capture and high-throughput analysis of CTCs using multi-omics technologies. However, not all CTCs may induce metastasis, so it is necessary to distinguish the most metastasis-prone CTC subpopulations. In addition, before designing relevant clinical trials, further research into culture conditions and animal models is needed to maximize the effectiveness of interventions and optimize standards of care.

Authors contribution

The first draft and revised of the article was written by R. Sh., SA. P., A.E., M.N. Sh, A.A.A., M.M. A., M. A., A. A., M.M-D., and P.A-Kh. T.E.M and H.S contributed to the study conception and design. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Reza Shahhosseini and SeyedAbbas Pakmehr have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tahereh Ezazi Maleki, Email: ezazi.sbmu2015@gmail.com.

Hossein Saffarfar, Email: dr.h.saffarfar@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. Cancer statistics. 2024;74(1):12–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gbolahan O, et al. Time to treatment initiation and its impact on real-world survival in metastatic colorectal cancer and pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 2023;12(3):3488–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li F, et al. Molecular targeted therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: current and evolving approaches. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1165666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuentes JDB, et al. Global stage distribution of breast cancer at diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2024. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larribère L, Martens UM. Advantages and challenges of using ctDNA NGS to assess the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) in solid tumors. Cancers. 2021;13(22):5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appierto V, et al. How to study and overcome tumor heterogeneity with circulating biomarkers: the breast cancer case. In: Seminars in cancer biology. Elsevier; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esposito A, et al. Liquid biopsies for solid tumors: Understanding tumor heterogeneity and real time monitoring of early resistance to targeted therapies. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;157:120–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li M, et al. Liquid biopsy at the frontier in renal cell carcinoma: recent analysis of techniques and clinical application. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):1–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visal TH, et al. Circulating tumour cells in the-omics era: how far are we from achieving the ‘singularity’? Br J Cancer. 2022;127(2):173–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartkopf AD, et al. Changing levels of circulating tumor cells in monitoring chemotherapy response in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(3):979–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia W, et al. In vivo coinstantaneous identification of hepatocellular carcinoma circulating tumor cells by dual-targeting magnetic-fluorescent nanobeads. Nano Lett. 2020;21(1):634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szczerba BM, et al. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature. 2019;566(7745):553–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasimir-Bauer S, et al. In early breast cancer, the ratios of neutrophils, platelets and monocytes to lymphocytes significantly correlate with the presence of subsets of circulating tumor cells but not with disseminated tumor cells. Cancers. 2022;14(14):3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aceto N, et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters are oligoclonal precursors of breast cancer metastasis. Cell. 2014;158(5):1110–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheung KJ, et al. Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell. 2013;155(7):1639–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung KJ, et al. Polyclonal breast cancer metastases arise from collective dissemination of keratin 14-expressing tumor cell clusters. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(7):E854–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gkountela, S., et al., Circulating tumor cell clustering shapes DNA methylation to enable metastasis seeding. Cell, 2019. 176(1): p. 98–112. e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wei R-R, et al. CTC clusters induced by heparanase enhance breast cancer metastasis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(8):1326–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donato C, et al. Hypoxia triggers the intravasation of clustered circulating tumor cells. Cell Rep. 2020;32(10):108105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francescangeli F, et al. Sequential isolation and characterization of single CTCs and large CTC Clusters in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancers. 2021;13(24):6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amintas S, et al. Circulating tumor cell clusters: united we stand divided we fall. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapeleris J, et al. Cancer stemness contributes to cluster formation of colon cancer cells and high metastatic potentials. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;47(5):838–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strell C, Entschladen F. Extravasation of leukocytes in comparison to tumor cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2008;6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Au SH, et al. Clusters of circulating tumor cells traverse capillary-sized vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(18):4947–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labelle M, Begum S, Hynes RO. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):576–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward Y, et al. Platelets promote metastasis via binding tumor CD97 leading to bidirectional signaling that coordinates transendothelial migration. Cell Rep. 2018;23(3):808–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao L, et al. Effects of flowing RBCs on adhesion of a circulating tumor cell in microvessels. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2017;16:597–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helwa R, et al. Tumor cells interact with red blood cells via galectin-4-a short report. Cell Oncol. 2017;40:401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Sousa e Melo F, et al. A distinct role for Lgr5+ stem cells in primary and metastatic colon cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7647):676–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasimir-Bauer S, et al. Expression of stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in primary breast cancer patients with circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W, et al. Unraveling the roles of CD44/CD24 and ALDH1 as cancer stem cell markers in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lianidou E, Hoon D. Circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA. In: Principles and applications of molecular diagnostics. Elsevier; 2018. p. 235–81. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adorno-Cruz V, et al. Cancer stem cells: targeting the roots of cancer, seeds of metastasis, and sources of therapy resistance. Can Res. 2015;75(6):924–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delle Cave D, et al. Nodal-induced L1CAM/CXCR4 subpopulation sustains tumor growth and metastasis in colorectal cancer derived organoids. Theranostics. 2021;11(12):5686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guan G, et al. The HIF-1α/CXCR4 pathway supports hypoxia-induced metastasis of human osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;357(1):254–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harney AS, et al. Real-time imaging reveals local, transient vascular permeability, and tumor cell intravasation stimulated by TIE2hi macrophage–derived VEGFA. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(9):932–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ortiz-Otero N, et al. Chemotherapy-induced release of circulating-tumor cells into the bloodstream in collective migration units with cancer-associated fibroblasts in metastatic cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma U, et al. Heterotypic clustering of circulating tumor cells and circulating cancer-associated fibroblasts facilitates breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;189:63–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smerage JB, et al. Monitoring apoptosis and Bcl-2 on circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 2013;7(3):680–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaiswal S, et al. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 2009;138(2):271–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coffelt SB, et al. IL-17-producing γδ T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522(7556):345–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiegel A, et al. Neutrophils suppress intraluminal NK cell–mediated tumor cell clearance and enhance extravasation of disseminated carcinoma cells. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(6):630–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei C, et al. Crosstalk between cancer cells and tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu S, et al. Targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cells derived from surgical stress: the key to prevent post-surgical metastasis. Front Surgery. 2021;8: 783218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo S, et al. The role of extracellular vesicles in circulating tumor cell-mediated distant metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yin Y, et al. Extracellular vesicles from mast cells induce mesenchymal transition in airway epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2020;21:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, et al. CD103-positive CSC exosome promotes EMT of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: role of remote MiR-19b-3p. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao Z, et al. Exosomal mir-10527–5p inhibits Migration, Invasion, Lymphangiogenesis and Lymphatic Metastasis by affecting Wnt/β-Catenin signaling via Rab10 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Nanomed. 2023;18:95–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dudiki T, et al. Mechanism of tumor-platelet communications in cancer. Circ Res. 2023;132(11):1447–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gomes FG, et al. Breast-cancer extracellular vesicles induce platelet activation and aggregation by tissue factor-independent and-dependent mechanisms. Thromb Res. 2017;159:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paku S, et al. The evidence for and against different modes of tumour cell extravasation in the lung: diapedesis, capillary destruction, necroptosis, and endothelialization. J Pathol. 2017;241(4):441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yadav A, et al. Tumor-associated endothelial cells promote tumor metastasis by chaperoning circulating tumor cells and protecting them from anoikis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10): e0141602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayes B, et al. Circulating tumour cell numbers correlate with platelet count and circulating lymphocyte subsets in men with advanced prostate cancer: data from the ExPeCT clinical trial (CTRIAL-IE 15–21). Cancers. 2021;13(18):4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Labuschagne CF, et al. Cell clustering promotes a metabolic switch that supports metastatic colonization. Cell Metab. 2019;30(4):720–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jordan NV, et al. HER2 expression identifies dynamic functional states within circulating breast cancer cells. Nature. 2016;537(7618):102–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Papadaki MA, et al. Circulating tumor cells with stemness and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition features are chemoresistant and predictive of poor outcome in metastatic breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18(2):437–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cristofanilli M, et al. The clinical use of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) enumeration for staging of metastatic breast cancer (MBC): International expert consensus paper. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;134:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang R, et al. Co-expression of stem cell and epithelial mesenchymal transition markers in circulating tumor cells of bladder cancer patients. OncoTargets therapy. 2020;13:10739–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Retz M, et al. Mucin 7 and cytokeratin 20 as new diagnostic urinary markers for bladder tumor. J Urol. 2003;169(1):86–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rink M, et al. The current role of circulating biomarkers in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Trans Androl Urol. 2019;8(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hong X-C, et al. PRL-3 and MMP9 expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in circulating tumor cells from patients with colorectal cancer: potential value in clinical practice. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 878639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun L, et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells regulate PD-L1-CTCF enhancing cancer stem cell-like properties and tumorigenesis. Theranostics. 2020;10(26):11950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mao D, et al. Pleckstrin-2 promotes tumour immune escape from NK cells by activating the MT1-MMP-MICA signalling axis in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023;572: 216351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nel I, et al. Role of circulating tumor cells and cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hep Intl. 2014;8:321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yi B, et al. The clinical significance of CTC enrichment by GPC3-IML and its genetic analysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodriguez-Aznar E, et al. EMT and stemness: key players in pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancers. 2019;11(8):1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu L, et al. GAS2L1 is a potential biomarker of circulating tumor cells in pancreatic cancer. Cancers. 2020;12(12):3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Obermayr E, et al. Cancer stem cell-like circulating tumor cells are prognostic in non-small cell lung cancer. J Personalized Med. 2021;11(11):1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Messaritakis I, et al. Characterization of DLL3-positive circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and evaluation of their clinical relevance during front-line treatment. Lung Cancer. 2019;135:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castro-Giner F, Aceto N. Tracking cancer progression: from circulating tumor cells to metastasis. Genome Medicine. 2020;12(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun N, et al. High-purity capture of CTCs based on micro-beads enhanced isolation by size of epithelial tumor cells (ISET) method. Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;102:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim T-H, et al. FAST: size-selective, clog-free isolation of rare cancer cells from whole blood at a liquid–liquid interface. Anal Chem. 2017;89(2):1155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Surappa S, et al. Integrated “lab-on-a-chip” microfluidic systems for isolation, enrichment, and analysis of cancer biomarkers. Lab Chip. 2023. 10.1039/D2LC01076C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeinali M, et al. High-throughput label-free isolation of heterogeneous circulating tumor cells and CTC clusters from non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Cancers. 2020;12(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ge Z. Isolation of circulating tumor cells by RosetteSep enrichment and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: from Liquid Biopsy to Immunotherapy, 2021; p. 13.

- 76.Neumann MHD, et al. Isolation and characterization of circulating tumor cells using a novel workflow combining the cell search® system and the Cell Celector™. Biotechnol Prog. 2017;33(1):125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lozar T, et al. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of magnetic-activated cell separation technology for CTC isolation in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10: 554554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alix-Panabières C. EPISPOT assay: detection of viable DTCs/CTCs in solid tumor patients. Minimal residual disease and circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. 2012; p. 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Tulley S. et al., Vita-Assay™ method of enrichment and identification of circulating cancer cells/circulating tumor cells (CTCs). Breast Cancer: Methods and Protocols, 2016; p. 107–119. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Bischoff, F.Z., G. Medoro, and N. Manaresi, DEPArray™ Technology for Single CTC Analysis. Circulating Tumor Cells: Isolation and Analysis, 2016; p. 365–376.

- 81.Gupta V, et al. ApoStream™, a new dielectrophoretic device for antibody independent isolation and recovery of viable cancer cells from blood. Biomicrofluidics. 2012. 10.1063/1.4731647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guo L, et al. Recent progress on nanostructure-based enrichment of circulating tumor cells and downstream analysis. Lab Chip. 2023. 10.1039/D2LC00890D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xue P, et al. Isolation and elution of Hep3B circulating tumor cells using a dual-functional herringbone chip. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2014;16:605–12. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ramirez AB, et al. RareCyte® CTC analysis step 1: AccuCyte® sample preparation for the comprehensive recovery of nucleated cells from whole blood. Circulating Tumor Cells: Methods Protoc. 2017. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7144-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gawad C, Koh W, Quake SR. Single-cell genome sequencing: current state of the science. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(3):175–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Armbrecht L, et al. Quantification of protein secretion from circulating tumor cells in microfluidic chambers. Adv Sci. 2020;7(11):1903237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Donato C, et al. Mass spectrometry analysis of circulating breast cancer cells from a Xenograft mouse model. STAR protoc. 2021;2(2): 100480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kahounová Z, et al. Circulating tumor cell-derived preclinical models: current status and future perspectives. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(8):530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lin D, et al. Circulating tumor cells: biology and clinical significance. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou Y, et al. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6): e0130873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fehm T, et al. Abstract PD3–12: Efficacy of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib in the treatment of patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer and HER2-positive circulating tumor cells-results from the randomized phase III DETECT III trial. Cancer Res. 2021;81(4):PD3-12. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Krol I, et al. Detection of clustered circulating tumour cells in early breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2021;125(1):23–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bidard F-C, et al. Efficacy of circulating tumor cell count–driven vs clinician-driven first-line therapy choice in hormone receptor–positive, ERBB2-negative metastatic breast cancer: The STIC CTC randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(1):34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu MC, et al. Circulating tumor cells: a useful predictor of treatment efficacy in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Park C-K, et al. Blood-Based Biomarker Analysis for Predicting Efficacy of Chemoradiotherapy and Durvalumab in Patients with Unresectable Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers. 2023;15(4):1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chemi F, et al. Pulmonary venous circulating tumor cell dissemination before tumor resection and disease relapse. Nat Med. 2019;25(10):1534–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Khoo BL, et al. Short-term expansion of breast circulating cancer cells predicts response to anti-cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6(17):15578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carmona-Ule N, et al. Short-term Ex Vivo Culture of CTCs from advance breast cancer patients: clinical implications. Cancers. 2021;13(11):2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mohamed BM, et al. Ex vivo expansion of circulating tumour cells (CTCs). Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nakamura A, et al. CTCs as tumor antigens: a pilot study using ex-vivo expanded tumor cells to be used as lysate for DC vaccines. Personalized Med Univ. 2019;8:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pereira-Veiga T, et al. CTCs-derived xenograft development in a triple negative breast cancer case. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(9):2254–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang Q, et al. Single-cell omics: a new perspective for early detection of pancreatic cancer? European J Cancer. 2023;190:112940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Orrapin S, et al. Deciphering the biology of circulating tumor cells through single-cell RNA Sequencing: implications for precision medicine in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhao Z-M, et al. Early and multiple origins of metastatic lineages within primary tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(8):2140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xu XR, Yousef GM, Ni H. Cancer and platelet crosstalk: opportunities and challenges for aspirin and other antiplatelet agents. Blood J American Society Hematol. 2018;131(16):1777–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cooke NM, et al. Aspirin and P2Y 12 inhibition attenuate platelet-induced ovarian cancer cell invasion. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen H-N, et al. EpCAM signaling promotes tumor progression and protein stability of PD-L1 through the EGFR pathway. Can Res. 2020;80(22):5035–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Muller P, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) renders HER2+ breast cancer highly susceptible to CTLA-4/PD-1 blockade. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(315):315ra188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li J, et al. Genetic engineering of platelets to neutralize circulating tumor cells. J Control Release. 2016;228:38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy decreases distant metastasis and inhibits local recurrence post-surgery in mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2023;34(23–24):1248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sun B, et al., Granzyme B-based CAR T cells block metastasis by eliminating circulating tumor cells. bioRxiv, 2024; p. 2024.03. 18.585442.

- 112.Li H, et al. CAR-T cells for Colorectal cancer: target-selection and strategies for improved activity and safety. J Cancer. 2021;12(6):1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dorff TB, et al. PSCA-CAR T cell therapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 2024;30(6):1636–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Li D, et al. EpCAM-targeting CAR-T cell immunotherapy is safe and efficacious for epithelial tumors. Sci Adv. 2023;9(48):eadg9721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pal K, Sheth RA. Engineering the tumor immune microenvironment through minimally invasive interventions. Cancers. 2022;15(1):196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liu L, et al. Mechanoresponsive stem cells to target cancer metastases through biophysical cues. Sci Trans Med. 2017;9(400):eaan2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Parkins KM, et al. Engineering circulating tumor cells as novel cancer theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10(17):7925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Diamantopoulou Z, et al. The metastatic spread of breast cancer accelerates during sleep. Nature. 2022;607(7917):156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mulrooney DA, Blaes AH, Duprez D. Vascular injury in cancer survivors. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5(3):287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ning N, et al. Improvement of specific detection of circulating tumor cells using combined CD45 staining and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;433:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Crosbie PA, et al. Circulating tumor cells detected in the tumor-draining pulmonary vein are associated with disease recurrence after surgical resection of NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1793–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Satelli A, et al. Epithelial–mesenchymal transitioned circulating tumor cells capture for detecting tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(4):899–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hosseini H, et al. Early dissemination seeds metastasis in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;540(7634):552–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.