Abstract

Background

Targeted next generation sequence analyses in a cohort of 961 previously described patients with clinically suspected Duchene muscular dystrophy (DMD) revealed that 145/961 (15%) had variants in genes associated with other muscular dystrophies (OMDs).

Methods

NGS was carried out in DMD negative patients after deletion/duplication analysis followed by WES for No variant cases.

Results

The majority of patients with OMDs had autosomal recessive diseases that included Limb‐Girdle Muscular Dystrophies (LGMDs), Bethlem, Ullrich congenital Myopathies and Emery‐Driefuss muscular dystrophy. 3.5% of patients were identified with other disorders like Charcot‐Marie Tooth and Nemaline myopathy. A small percentage of patients, 0.6% remain undiagnosed. Of a total of 78 genetic variants identified, 44 were found to be novel. Interestingly, a third of patients with OMDs were found to have LGMD2E/R4, a severe form of LGMD that afflicts young children with clinical symptoms similar to DMD. Almost one third of the unrelated LGMD2E/R4 patients had the same point mutation (c.544A>C) in the SGCB gene, suggestive of a founder effect, described here for the first time in India.

Conclusion

This study underscores the need for a complete genetic work up to precisely diagnose patients and to initiate appropriate counseling programs, disease management and prevention strategies.

Keywords: autosomal recessive disorder, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2E‐R4, muscular dystrophy, next generation sequencing, overlapping symptoms

All the LGMDs molecularly confirmed in this study were the ones clinically suspected to be DMD/BMD. Here in this study, we have attempted to understand age at onset in the patients, could be a differentiating factor to distinguish DMD/BMD from other muscular dystrophies. Based on the age at onset, it is evident that LGMD 2E appears closest in severity to DMD in our cohort, with the variant c.544A>C being the most common and clinical symptoms also shows the same.

1. INTRODUCTION

Next generation DNA sequencing methods have contributed greatly to the precise and unequivocal diagnosis of clinically suspected patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) leading to an enhanced pick‐up rate. DMD is a monogenic, X‐linked recessive, degenerative, neuromuscular disorder affecting young males, and leads to fatal cardiopulmonary and respiratory failure. Early and precise identification of variants in the dystrophin (DMD) gene is critical to the diagnosis of the disease and is becoming an essential part of an effective disease management strategy (Birnkrant et al., 2018). Since DMD is a progressive disease, care guidelines and disease prevention strategies through counselling need to be initiated at the earliest, particularly since effective therapies are now becoming available for a subset of patients (Ryder et al., 2017; Verhaart & Aartsma‐Rus, 2019).

In a recent study, we reported the DMD gene mutational profiles of 961 unrelated, clinically suspected male DMD patients. We utilized a molecular diagnostic approach, which is cost‐effective for most patients and follows a systematic process that sequentially involves identification of hotspot deletions using mPCR, large deletions and duplications using MLPA, and small insertions/deletions and point mutations using an NGS congenital muscular dystrophy gene panel. DMD gene variants were identified in nearly 85% (816/961) of the patients (Kumar et al., 2020). The remaining 15% of patients (145/961) who lacked a DMD gene variant, form the basis of the presentation in this manuscript.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients

Nine hundred and sixty‐one clinically suspected DMD/BMD male patients, 99% of who were unrelated, were received at MDCRC (a non‐profit organization dedicated to diagnosis, care and counselling of patients with muscular dystrophies: www.mdcrcindia.org), in the state of Tamil Nadu (TN) between 2006 and 2013 for molecular diagnosis. These patients were largely referred to MDCRC through a rural MDCRC community genetics initiative (manuscript in preparation) as well as from hospital and clinic referrals in TN state.

Young males within the ages of 2–35 years exhibiting characteristic symptoms of DMD (Kumar et al., 2020) were included in our cohort of 961 patients. Male patients above the age of 35 years and females with DMD‐like symptoms were excluded. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient (or parent/guardian), prior to sample collection.

2.2. Sample collection and DNA isolation and preservation

Three milliliters of blood samples were collected from clinically suspected DMD patients in EDTA vacutainers. Genomic DNA was extracted using a simple desalting protocol as previously described (Miller et al., 1988) and stored at ‐20°C until further use.

2.3. Multiplex PCR, multiplex ligation‐dependent probe amplification (MLPA) and next generation sequencing of DNA samples

The molecular diagnostic workup of genomic DNA was analyzed as outlined by the algorithm in Figure 1. mPCR was performed first and was designed to detect any deletion in the hot spot region of the DMD gene covering 30 exons as we have previously described (Sakthivel Murugan et al., 2010). MLPA analysis was next carried out in mPCR negative samples using PO34 and PO35 probes purchased commercially from MRC, Holland (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) as previously described (Sakthivel Murugan et al., 2010). The absence of a DMD gene variant following mPCR or MLPA led to sequencing of samples using next generation sequence (NGS) analysis as previously detailed (Kumar et al., 2020). The libraries generated were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq series 4500 at MedGenome Labs (Bangalore, India) to generate 2 × 150 bp sequence reads at 80–100× sequencing on‐target depth. Only non‐synonymous and splice site variants found in the muscular dystrophy and congenital myopathy panel genes (Table S1) were used for clinical interpretation. Sanger sequencing using standard protocols on an ABI 3730xl instrument was used to validate the presence of point mutations identified by NGS.

FIGURE 1.

Molecular diagnostic strategy used for 961 suspected DMD patients revealed 105 patients with other muscular dystrophies (OMD). An algorithm used to diagnose 961 patients with clinically suspected DMD. mPCR: Mutiplex PCR, MLPA: Multiplex ligation‐dependent probe amplification; NGS: Next‐generation sequencing; WES: Whole exome sequencing. The number of patients at each step are represented in red.

2.4. Whole exome sequencing

2.4.1. DNA isolation, exome library preparation and sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood using a manual salting out method described in our pervious paper (Kumar et al., 2020). For library preparation, 200 ng of the Qubit quantified DNA was fragmented to ~350 bp inserts. The library was hybridized and enriched using ~50 Mb Agilent Sure Select whole exome panel (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The fragments were then end‐repaired, 3′ adenylated and ligated with the indexed adapters. The adapter‐ligated fragments were then amplified with adapter‐specific primers followed by size selection and purification to generate gDNA library. Library was assessed for fragment size distribution using Tape Station (Agilent, USA) and was quantified using Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and sequenced as 2 × 150 bp paired‐end reads on an Illumina Hiseq 4500 (Illumina, CA) machine according to the manufacturer's protocol. The libraries were sequenced to an average sequencing depth of ≥80–100×.

2.4.2. Data processing, variant calling and annotation

Following quality check and adapter trimming using fastq‐mcf (version 1.04.676), the sequencing reads obtained are aligned to human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19). The aligned reads were sorted, and duplicate reads were removed and the variants were called using GATK best practices pipeline using Sentieon (v201808.07). Gene annotation of the variants was performed using VEP program against the Ensembl release 91 human gene model for the gene panel (Table S1b). The variants were annotated for allele frequency [population databases GnomAD(v3.0), 1000 genome, MedGenome population specific database], in silico prediction tools [CADD, PolyPhen‐2, SIFT, Mutation Taster2, and LRT] and disease databases [OMIM, ClinVar and HGMD]. Clinically significant variants were sequentially prioritized and analyzed using Varminer (MedGenome proprietary variant interpretation tool). In addition to single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small Indels, copy number variants (CNVs) are detected from targeted sequence data using the ExomeDepth (v1.1.10) method. Based on the comparison of read‐depths of the test data with the matched aggregate reference dataset, the algorithm detects CNVs (≥400 bp deletions and duplications). The variants in genes correlating the disease phenotype and inheritance were prioritized. Clinical interpretation of the variants was assigned based on ACMG guidelines.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

2.6. Data submission

All variants identified in this study have been submitted to the Global Variome shared LOVD (www.lovd.nl) and that can be accessed using the link below: https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals?search_owned_by_=%3D%22Lakshmi%20Bremadesam%22#order=id%2CASC&search_Individual/Reference=MDCRC%202021.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Molecular diagnostic strategy used for 961 suspected DMD patients revealed 145 patients with other muscular dystrophies (OMD) and other non‐muscular dystrophies

Initial clinical diagnosis of 961 male patients made largely at the community primary health care level, relied essentially on symptoms, with special emphasis on age at onset of disease, frequent falls, waddling gait, calf muscle hypertrophy, difficulty climbing stairs, Gower's sign and age at loss of ambulation. Males aged 2–35 years with one or more of these clinical symptoms were identified as clinically suspected DMD patients. As we have previously reported, DNA samples of 961 clinically suspected DMD patients were subjected to a methodological algorithm, using a sequential protocol of mPCR, MLPA followed by NGS, designed to identify variants in the DMD gene (Kumar et al., 2020). As is summarized in Figure 1, 715 of the 961 suspected DMD patients (74.4%) were confirmed to have variants in the DMD gene following DNA analysis using multiplex PCR and MLPA (Kumar et al., 2020), leaving 246 patients without detected variants after this round of analysis. This group of 246 suspected DMD patients was next subjected to next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis, which revealed an additional 101 patients with small deletions/ duplications or point mutations in the DMD gene. These relatively small mutations (including point mutations and small deletions or insertions) had remained undetected by the mPCR and MLPA methods. NGS analysis thus increased the diagnostic yield thereby confirming the diagnosis of DMD/BMD from 74.4% (mPCR and MLPA) to a total of 84.9% patients in our cohort (Figure 1).

No DMD gene variant was found in 15% (145/961) of patients despite being clinically suspected of having DMD/BMD. NGS data analysis further revealed that 100 of the 145 patients (Figure 1) had other muscular dystrophies, (OMDs; note: for ease of description, we have defined OMDs as patients who do not harbour a DMD gene mutation, but have a bona fide muscular dystrophy with variants in known muscular dystrophy associated genes) including Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophies (LGMD), Bethlem myopathy and Emery Dreifuss myopathy, among others. Twenty nine of the 145 patients were found to have other disorders (not muscular dystrophies) with some overlapping clinical symptoms with DMD. These included patients diagnosed with Axonal Charcot–Marie tooth syndrome and nemaline myopathy, among others.

NGS analysis further revealed that 16 of 145 patients in our cohort had no variants in the genes interrogated in our muscular dystrophy NGS gene panel (Table S1). To further investigate the underlying genetic cause of disease in this group of patients, we subjected their DNA to whole exome sequence (WES) analysis. Our analysis revealed that five additional patients had other muscular dystrophies (OMDs), which had been missed by the initial NGS analysis, likely due to procedural differences between the two methods. Two OMD patients were found to have mutations in two different genes (Patient 1; SGCB and UBA1; Patient 2: SYNE2 and ANO5) (Table 1; shaded in green). Another 5 of 16 patients were diagnosed with other disorders, including myotonia congenita, Charcot Marie tooth disease and Brody myopathy, among others (Table 1). Six patients currently remain undiagnosed with no identifiable variant found upon interrogating the WES Muscular Dystrophy Gene Panel (Tables 1 and S1b).

TABLE 1.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) data of 16 patient samples

| S. No | Was the gene tested in NGS panel? | Gene | Disease category | Type of disease | Variant identified | Variant classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | SGCB | OMD | Limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy‐2E | c.‐60_(429+1_430–1){0} | Likely Pathogenic |

| No | UBA1 | OMD | X‐linked spinal muscular atrophy 2 | c.334C>T | Uncertain Significance | |

| 2 | No | SYNE2 | OMD | Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐5 | c.7076G>T | Uncertain Significance |

| Yes | ANO5 | OMD | Limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy‐2 L | c.827A>T | Uncertain Significance | |

| 3 | Yes | COL6A3 | OMD | Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy‐1; Bethlem myopathy‐1 | c.5645C>T | Uncertain Significance |

| 4 | Yes | SGCG | OMD | Limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy‐2C | c.(297+1_298–1)_(385+1_386‐1)del | Likely Pathogenic |

| 5 | Yes | FKTN | OMD | Congenital MD‐dystroglycanopathy with brain and eye anomalies/Congenital MD‐dystroglycanopathy without impaired intellectual development/LGMD—dystroglycanopathy | c.436C>T | Uncertain Significance |

| 6 | No | CLCN1 | Others | Myotonia congenita | c.2467C>T | Pathogenic |

| 7 | No | MICU1 | Others | Myopathy with extrapyramidal signs | c.91C>T | Pathogenic |

| 8 | No | SH3TC2 | Others | Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 4C | c.3327+2T>C | Pathogenic |

| 9 | No | ATP2A1 | Others | Brody myopathy | c.1808C>T | Uncertain Significance |

| No | NEFH | Others | Axonal Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2CC | c.74A>G | Uncertain Significance | |

| 10 | No | CHRND | Others | Fast‐channel congenital myasthenic syndrome‐3B/Congenital myasthenic syndrome‐3C | c.259C>T | Uncertain Significance |

| 11 | Not applicable | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant |

| 12 | Not applicable | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant |

| 13 | Not applicable | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant |

| 14 | Not applicable | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant |

| 15 | Not applicable | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant |

| 16 | Not applicable | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant | No variant |

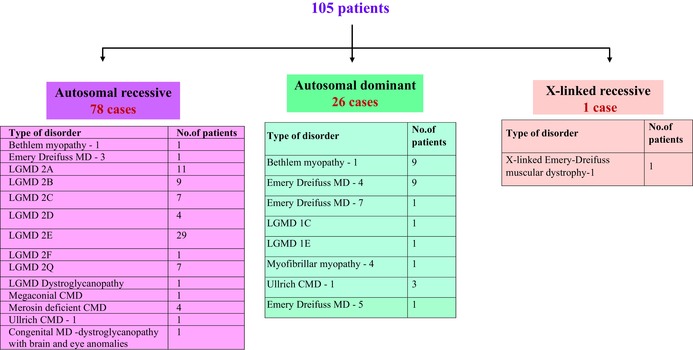

3.2. The majority of OMD patients had autosomal recessive disease

Variant analysis of the 105 OMD patients identified by NGS and WES analysis revealed that 78 of 105 (74.2%) patients had autosomal recessive (AR) diseases (Table 2). While limb girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD) 2E was found most abundantly at 37.1% in this class of patients, LGMD 2A (14%) and LGMD 2B (11.5%) were also encountered frequently (Table 2). Other LGMDs identified included LGMD 2C, 2D, 2F and 2Q. This finding (Table 2) is not surprising given that consanguinity and endogamy, which form the basis of AR disease propagation, are both commonly encountered in the state of Tamil Nadu (Centerwall & Centerwall, 1966). In this regard, in our cohort of 105 OMD cases, we found 58 cases were born to consanguineous couples of which 45 had AR LGMDs of which LGMD2E was the most predominant (21/45). In terms of family history, 23 out of 105 patients had a history of the disease in the family (Table 3). Interestingly, 18 out of 105 patients had both a family history and were products of consanguinity also. Among these, LGMD 2E was again predominant with five families having both family history and consanguinity.

TABLE 2.

Classification of the identified other muscular dystrophies

|

TABLE 3.

Summary of data of patients with autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant and X‐linked recessive diseases

| S. No | Name of the disorder | Number of patients | Inheritance pattern | Age at onset | Number of ambulant patients | Number of non ambulant patients | Age at loss of ambulation | Numbers with family history | Numbers with consanguinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bethlem | 10 |

AD – 9 AR – 1 |

1 to 15y | 8 | 1 | 11y | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | Emery | 13 |

AD – 11 AR – 1 XR – 1 |

2 to 18y | 7 | 4 | 3 to 12y | 5 | 7 |

| 3 | LGMD 2A | 11 | AR – 11 | 6m to 18y | 8 | 2 | 19 to 20y | 2 | 5 |

| 4 | LGMD 2B | 9 | AR – 9 | 3 to 32y | 8 | 1 | 30y | 2 | 7 |

| 5 | LGMD 2E | 29 | AR – 29 | 3 to 18 | 19 | 8 | 8 to 19y | 6 | 21 |

| 6 | LGMD 2Q | 7 | AR – 7 | 2 to 6 | 4 | 1 | 14y | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | Other minor Muscular dystrophies | 26 |

AR – 20 AD – 6 |

6m to 10y | 22 | 1 | 11y | 4 | 13 |

| Total | 105 | 23 | 58 | ||||||

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; XR, X‐linked recessive.

Twenty‐six cases of OMD with an autosomal dominant (AD) mode of inheritance were found among the 105 patients. Of these, Bethlem myopathy and Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy were the most frequently encountered (34.6% each) (Table 2). Only a single patient with an X‐linked AR disorder was found (Table 2; X‐linked Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐1).

3.3. New variants identified in the majority of patients with OMDs

A total of 78 gene variants were found in the 105 patients with the listed OMDs (Tables 4 and S2). Interestingly, 44 of 78 (56.4%) of these gene variants were found to be novel. All novel variants have been deposited in the Global Variome shared LoVD database, and marked as “Novel variant (2021)”: https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals?search_owned_by_=%3D%22Lakshmi%20Bremadesam%22#order=id%2CASC&search_Individual/Reference=MDCRC%202021.

TABLE 4.

Summary of the mutational status of 105 OMDs reveal a total of 44 novel variants

| Disease | Gene | Novel variant | Previously reported | Total variants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGMD 2A | CAPN3 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| LGMD 2B | DYSF | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| LGMD 2C | SGCG | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| LGMD 2D | SGCA | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| LGMD 2E | SGCB | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| LGMD 2F | SGCD | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| LGMD 2Q | PLEC | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| LGMD 1C | CAV3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| LGMD 1 E | DNAJB6 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| LGMD Dystroglycanopathy | POMT2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bethlem myopathy | COL6A1, COL6A2, COL6A3 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐3 | LMNA | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐4 | SYNE1 | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐5 | SYNE2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐7 | TMEM43 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Congenital muscular dystrophy‐dystroglycanopathy with brain and eye anomalies | FKTN | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Megaconial type congenital muscular dystrophy | CHKB | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Merosin‐deficient congenital muscular dystrophy type 1A | LAMA2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Myofibrillar myopathy‐4 | LDB3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy 1 | COL6A1, COL6A2 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy‐1; Bethlem myopathy‐1 | COL6A3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| X‐linked Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐1 | EMD | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 44 | 34 | 78 |

Of the novel variants, the largest numbers were found in patients with LGMD2Q (n = 6) and LGMD2B (n = 6). Given that 56.4% of all the variants were found to be novel, it is not surprising that the majority (46%) were predicted to be variants of uncertain significance (VUS), 27% of variants were found to be pathogenic and the remaining 27% to be likely pathogenic. Thirty four of the 78 gene variants had been previously reported in the literature (Table 4 and the URL above).

3.4. A third of the OMD patients (32.3%) were diagnosed with other disorders

NGS and WES analyses together revealed that 34 of the 105 patients did not have bona fide muscular dystrophies and were therefore categorized as patients with “other disorders”, as summarized in Table 5. The majority of this group of patients (19/34) had autosomal recessive disease with congenital myasthenic syndrome (7/19), a group of inherited disorders characterized by muscle weakness which is aggravated upon physical exertion (Engel et al., 2015), being the most common. Nemaline myopathy was the next most commonly encountered disorder (5/19). The nemaline myopathies are a heterogenous group of congenital myopathies caused by de novo mutations in at least twelve genes, with α‐actin (ACTA1) and nebulin (NEB) being the most common. A broad spectrum of symptoms is encountered with muscle weakness and hypotonia being predominant (Sewry et al., 2019). Three out of 19 patients were found to have autosomal recessive Charcot Marie tooth (CMT) disease, while 2/14 patients had autosomal dominant CMT (Table 5). CMT represents a set of heterogeneous neuropathic disorders characterized broadly by muscle weakness and decreased muscle size (Morena et al., 2019).

TABLE 5.

Classification of patients with other disorders

|

Of the 14 patients identified with autosomal dominant inherited disease, in the other disorders category, five patients had distal myopathies, a set of primary muscle disorders, which like other muscular dystrophies, exhibit muscle weakness and progressive loss of muscle fibers (Savarese et al., 2020). A single rare case of the X‐linked dominant reducing body myopathy‐1 with infantile or early childhood onset was also identified (Table 5). This category of “other disorders” with several clinical symptoms that overlap with those of DMD, will be elaborated upon elsewhere (manuscript in preparation).

3.5. Analysis of patients with other muscular dystrophies (OMDs): The autosomal recessive limb girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMDs)

3.5.1. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A (LGMD2A/LGMDR1) (MIM# 253600)

LGMD2A, recently classified as LGMDR1, represents a progressive myopathy manifested by the deficiency of a skeletal muscle‐specific isoform of the calcium‐dependent Calpain cysteine protease family referred to as Calpain 3 (CAPN3) (Richard et al., 1995). Eleven of the 78 patients in our cohort of male patients with autosomal recessive OMDs were found to have gene variants in the in the CAPN3 gene associated with LGMD2A. A total of eight CAPN3 gene variants were encountered in the 11 patients, of which three point mutations (c.2003T>G; c.946‐2A>G and c.1343G>A) were found in two patients each (Table 6; see colored cells). Additionally, 3/8 mutants were found to be novel (Table 6). The average age at disease onset was 11.2+/− 5.6 year while the age at diagnosis was found to be 18.8+/−5.9 years in our cohort with a range of 8–27 years. A gap of 7.1 years between the onset of disease and diagnosis was observed in this cohort.

TABLE 6.

Eleven patients with LGMD2A (LGMDR1) with mutations in the CAPN3 gene

| S. No | Age at onset | Age at diagnosis | Consanguinity | Family history | Variant identified | Variant classification | Zygosity | Reported/novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 23 | Yes | Yes | c.608C>T | Likely Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 2 | 12 | 24 | Yes | No | c.1273A>T | Likely Pathogenic | Homozygous | Novel |

| 3 | 13 | 15 | No | No | c.1333G>C | Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 4 | Not available | 11 | No | No | c.2050+1G>A | Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 5 | 3 | 17 | No | No | c.2033A>T | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 6 | 9 | 27 | No | No | c.2003T>G | Uncertain Significance | Homozygous | Novel |

| 7 | 6 months | 8 | Yes | No | c.2003T>G | Uncertain Significance | Homozygous | |

| 8 | 13 | 15 | No | No | c.946‐2A>G | Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 9 | 15 | 16 | No | No | c.946‐2A>G | Pathogenic | Homozygous | |

| 10 | 13 | 24 | Yes | Yes | c.1343G>A | Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 11 | 15 | 20 | Yes | No | c.1343G>A | Pathogenic | Homozygous |

Note: Colored cells indicate the same CAPN3 gene variants. 45% Consanguinity and 18% Family history.

3.5.2. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2B/R2 (MIM# 253601)

LGMD2B/R2 belongs to a class of disorders termed the “dysferlinopathies” caused by deficient levels of the dysferlin protein due to mutations in the DYSF gene. LGMD2B is considered to a milder form of the LGMDs as the age at onset of LGMD2B, though variable, commonly occurs relatively late, and manifests between the ages of 20–30 years. LGMD2B is characterized by weakness and atrophy of the pelvic and shoulder girdle muscles. Of all the LGMDs, LGMD2B demonstrates the slowest progression (Cacciottolo et al., 2011).

Nine suspected DMD patients were diagnosed with LGMD2B/R2 following NGS analysis, of which six had novel mutations in the DYSF gene (Table 7). One pair of unrelated patients had the same DYSF gene mutation (c.1256G>C; Table 7). The average age at onset was 17.8+/− 8.8 years while the age at diagnosis of this group of patients was found to be 31.5 +/− 10.7 years (range 19–56 years). A 13.8‐year gap between onset of disease and disease diagnosis was noted.

TABLE 7.

Nine patients with LGMD2B (LGMDR2) with mutations in the DYSF gene

| S. No | Age at onset | Age at diagnosis | Consanguinity | Family history | Variant identified | Variant classification | Zygosity | Reported/novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | 33 | No | No | c.2625G>A | Pathogenic | Homozygous | Novel |

| 2 | 19 | 27 | No | No | c.6131G>T | Likely Pathogenic | Homozygous | Novel |

| 3 | 32 | 35 | Yes | No | c.4110_4112del | Pathogenic | Homozygous | Novel |

| 4 | 25 | 56 | Yes | Yes | c.3321_3329delCCGCCGCCG | Uncertain Significance | Homozygous | Novel |

| 5 | 3 | 21 | Yes | No | c.2266C>T | Likely Pathogenic | Homozygous | Novel |

| 6 | 10 | 19 | Yes | No | c.5743G>A | Uncertain Significance | Homozygous | Reported |

| 7 | 10 | 30 | Yes | No | c.395C>A | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 8 | 19 | 35 | Yes | Yes | c.1256G>C | Likely Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 9 | 20 | 28 | Yes | No | c.1256G>C | Likely Pathogenic | Homozygous |

Note: Colored cells indicate the same DYSF gene variants. 78% Consanguinity and 22% Family history.

3.5.3. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy LGMD2Q/R17 (MIM# 613723)

Seven patients were confirmed by NGS having variants in the Plectin (PLEC) gene, leading to a possible diagnosis of LGMD2Q (Gundesli et al., 2010). A wide array of mutation types associated with the PLEC gene was observed in this cohort of patients. While patients 1 and 6 (Table 8) were found to harbour heterozygous mutations in the PLEC gene, patients 3, 4, 5 and 7 were found to have compound heterozygous variants in the PLEC gene (Table 8). Additionally, patients 2, 3 and 5 had variants in the LAMA2 and DYSF genes in addition to heterozygous variants in the PLEC gene (Table 8). The age at disease onset for this cohort was found to be 4.3+/− 1.5 years while the age at diagnosis 14+/−7 years. Six out of 7 variants identified in the PLEC gene in our cohort were found to be novel (Table 8) with two of the 7 patients sharing the same PLEC variant (c.6359G>A), and all PLEC gene variants classified as VUS.

TABLE 8.

Seven patients with LGMD2Q (LGMDR17) with mutations in the PLEC gene

| S. No | Age at onset | Age at diagnosis | Consanguinity | Family history | Zygosity | Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | Mutation 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 15 | No | Yes | Heterozygous | PLEC ; Exon 11; c.1570G>A | None | None |

| 2 | 6 | Not available | No | No | Heterozygous | PLEC ; Exon 14; c.2078G>A | LAMA2 ; Exon 14; c.1963C>T | None |

| 3 | 3 | 15 | Yes | No | Heterozygous | PLEC ; Exon 32; c.10589C>T | PLEC ; Exon 31; c.5008C>T | DYSF ; Exon 34; c.3779G>A |

| 4 | 2 | 24 | No | No | Heterozygous | PLEC ; Exon 32; c.8922G>C | PLEC ; Exon 28; c.4198G>A | None |

| 5 | Not available | 5 | Yes | No | Heterozygous | PLEC ; Exon 32; c.11026C>T | PLEC ; Exon 15; c.2170C>T | DYSF ; Intron 34; c.3898‐4C>G |

| 6 | 5 | 18 | No | Yes | Heterozygous | PLEC ; Exon 31; c.6359G>A | None | None |

| 7 | 4 | 7 | No | No | Heterozygous | PLEC ; Exon 31; c.6359G>A | PLEC ; Exon 31; c.6284C>T | PLEC ; Exon 23; c.3206A>G |

Note: Colored cells indicate the same PLEC gene variants. 28% Consanguinity and 28% Family history.

3.5.4. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2E/ (LGMD2E/R4, MIM# 604286)

Of the 105 patients who had mistakenly been diagnosed as having DMD based on symptoms at presentation, 29/105 (27.6%) patients were accurately diagnosed following NGS analysis to have LGMD2E (Table 9). LGMD2E, an autosomal recessive disorder, is caused by mutations in the gene for β‐sarcoglycan (SGCB).

TABLE 9.

LGMD2E: Twenty‐nine patients with LGMD2E (LGMDR4) with mutations in the SGCB and clinical features

| S. No | Variant identified | Classification—NGS | Age at diagnosis | Consanguinity | Family history | Age at onset | Ambulation status | Age at LoA | Zygosity | Reported/novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.655A>T | Pathogenic | 10 | Yes | No | 3 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | Novel |

| 2 | c.621+1G>T | pathogenic | 14 | Not available | Not available | 10 | Non Ambulant | 13 | Homozygous | Reported |

| 3 | c.499G>A | Likely Pathogenic | 6 | No | No | 6 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | Reported |

| 4 | c.244‐1G>A | Likely Pathogenic | 8 | No | No | 7 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | Novel |

| 5 | c.490A>G | Likely Pathogenic | 32 | Yes | No | 18 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | Novel |

| 6 | c.355A>T | Likely Pathogenic | 22 | No | No | 10 | Non Ambulant | 19 | Homozygous | Reported |

| 7 | c.‐60_(429+1_430–1){0} | Likely Pathogenic | 11 | Yes | Yes | 5 | Non Ambulant | 10 | Homozygous | Novel |

| 8 | c.572delT | Pathogenic | 8 | Yes | No | 6 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | Reported |

| 9 | c.572delT | Pathogenic | 19 | No | No | 9 | Non Ambulant | 14 | Heterozygous | |

| 10 | c.572delT | Pathogenic | 12 | No | No | 9 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Heterozygous | |

| 11 | c.572del | Pathogenic | 8 | Yes | No | 3 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 12 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 9 | No | No | 7 | Ambulant | Not Applicable | Homozygous | Reported |

| 13 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 13 | Yes | No | 5 | Non Ambulant | 9 | Homozygous | |

| 14 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 10 | Yes | Not available | 8 | Non Ambulant | 9 | Homozygous | |

| 15 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 12 | Yes | No | 7 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 16 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 7 | Yes | No | 6 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 17 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 8 | Yes | No | 6 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 18 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 5 | Yes | No | 3 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Heterozygous | |

| 19 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 11 | Yes | No | 7 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 20 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 7 | Yes | Yes | 6 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 21 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 7 | Yes | No | 4 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 22 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 11 | Yes | Yes | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | Homozygous | |

| 23 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 11 | Yes | No | 6 | Non Ambulant | 10 | Homozygous | |

| 24 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 4 | Yes | Yes | Not Available | Not Available | Not Available | Heterozygous | |

| 25 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 10 | No | Yes | 7 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 26 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 10 | Yes | No | 5 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 27 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 8 | Yes | Yes | 4 | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 28 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 8 | Yes | No | Not Available | Ambulant | Not applicable | Homozygous | |

| 29 | c.544A>C | Uncertain Significance | 11 | Yes | No | 3 | Non Ambulant | 8 | Homozygous |

Note: Colored cells indicate the same SGCB gene variants. 72% Consanguinity and 21% Family history.

While a total of nine variants were found in the 29/105 patients with mutations in the SGCB gene (Table 9 and arrows in Figure 2a), two sets of common variants were encountered in this cohort of LGMD2E patients. The c.544A>C point variant was found in 18/29 (62%) unrelated patients (Figure 2a, red arrow) while c.572delT frame‐shift variant was found in four patients (Figure 2a, pink arrow). Both variants have been previously reported, but not in multiple patients samples from a single site (Duggan et al., 1997; Semplicini et al., 2015). While the former variant has been predicted to be likely pathogenic, the latter has been found to be pathogenic (Table 9).

FIGURE 2.

Mutational and functional profile of the SGCB gene in patients with LGMD2E. (a) Organization of the SGCB gene showing six exons with cDNA coordinates numbered below. Blue arrows indicate the positions of single mutations identified in patients. Red arrow indicates the most common c.544A>C variant; Pink arrow: shows the position of the c572delT variant. Exons 1and 2 encode the IC domain, exons 2 and 3 in code the trans‐membrane domain; exons 3,4,5 and 6 encode the EC domain and exons 1 and 6 encompass the 5′ and 3′ non‐coding sequences. (b) Comparison of disease severity of different mutations in the SGCB gene based on age of disease onset in years, in the LGMD2E patients. All but 544 a to C refers to all variants other than the c.544A>C. Calculated p value of 0.035 is considered statistically significant.

The age at onset of disease in our cohort of 29 patients was found to be 6.5+/−3.1 years. The age at loss of ambulation was found to be 11.5+/−3.7 years, which appears to be lower than previously reported (Semplicini et al., 2015). In order to determine if a genotype to phenotype correlation could be gleaned from this cohort of patients, we compared the age of disease onset in patients with the c.544A>C variant (n = 18) to the c572delT(n = 4) and to the other variants considered collectively (n = 7). As is evident in Figure 2b, the age at disease onset in patients with the c.544A>C variant was 5.6+/−1.5 years as compared to the c.572delT variant where the age at disease onset was 6.8+/−2.9 years. While there was no statistically significant difference of this measure between patients with these two variants, a significant difference was noted between variant c.544A>C and the other variants considered collectively in the cohort (Figure 2b: p = 0.035). Given that the age of disease onset between the c.544A>C and c.572delT variants is not statistically different and that the latter has been predicted to be pathogenic, our data support the reclassification of the former from variant of unknown significance to pathogenic at this time.

Given that all the LGMDs identified in this study were misdiagnosed to be DMD/BMD, we sought to determine if LGMDs could be differentiated from DMD based on the age at disease onset. As illustrated in Figure 3, the average age at onset of patients with DMD from our previous study of 961 patients (Kumar et al., 2020) was found to be 6.17+/− 3 years. In comparison, the age at onset of LGMD2A was 11.2+/−5.6 (1,8 fold higher than DMD), LGMD2B was 17.8+/−8.8 (2.9 fold higher than DMD), LGMD2Q was 4.3+/−1.5 (0.7 fold or 30% lower than DMD) and LGMD2E 6.5+/−3.1 (no change compared to DMD). Based on this single criterion, it is evident that LGMD2E appears closest in severity to DMD in our cohort, followed by LGMD 2Q.

FIGURE 3.

Age at onset and age at diagnosis of LGMDs compared to DMD. Comparison of the ages at onset of disease and ages of disease diagnosis (in years), in patients diagnosed with LGMDs, 2A, 2B, 2E, 2Q and DMD.

A comparison of the age at onset and age at diagnosis (Figure 3) of the LGMDs in this cohort compared to DMD demonstrated that, the differences between the two measures was largest for LGMD2B (13.8 years), followed by LGMD2Q (9.7 years) and LGMD2A (7.1 years). The difference between the age of onset and the age of diagnosis appeared to be shortest for the most clinically severe muscular dystrophies, DMD (3.9 years) and LGMD2E (4.2 years).

3.6. The autosomal dominant myopathies

3.6.1. Bethlem myopathy (MIM# 158810) and Emery Driefuss muscular dystrophy (MIM# 616516)

Ten cases of Bethlem Myopathy and four cases of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (UCMD; MIM# 254090) were identified in the NGS screen of the 105 suspected DMD patients (Table 2). As opposed to Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy which presents with a severe phenotype, Bethlem myopathy is a milder congenital autosomal dominant myopathy. Both disorders are caused by mutations in genes encoding type VI collagen, including COL6A1 (a1 chain), COL6A2 (a2 chain) and COL6A3 (a3 chain). Collagen VI is an essential part of the extracellular matrix that generates a microfibrillar network associated with the cells and surrounding basement membrane. Mutations in Collagen IV are known to involve both connective tissues and muscle and patients often present with Gower's sign, toe walking and contractures of the joints (rev in [Bushby et al., 2014]).

Four of 10 patients diagnosed with Bethlem myopathy were found to have mutations in the COL6A1 gene, five patients had mutations in the COL6A3 gene and a single patient had a mutation in the COL6A2 gene (Table 10). 4/10 variants identified were found to be novel. The age of disease onset and diagnosis in this small cohort was variable with an average age 10.6+/−7.86 years (range: 2–23 years, Table 10).

TABLE 10.

Ten patients with Bethlem myopathy (LGMDD5) with mutations in the COL6A genes

| S. No | Age at onset | Age at diagnosis | Consanguinity | Family history | Gene | Variant identified | Classification—NGS | Zygosity | Reported/novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not available | 2 | No | No | COL6A1 | c.1022G>A | Likely Pathogenic | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 2 | 1 | 11 | No | No | COL6A1 | c.2348G>A | uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 3 | Not available | 3 | No | No | COL6A1 | c.979A>G | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 4 | 2 | 8 | No | No | COL6A1 | c.928_930del | Likely Pathogenic | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 5 | 5 | 23 | No | No | COL6A2 | c.2611G>A | Likely Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 6 | 15 | 23 | No | No | COL6A3 | c.2030G>A | Likely Pathogenic | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 7 | 3 | 4 | Yes | No | COL6A3 | c.5825C>T | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 8 | 10 | 14 | Yes | Yes | COL6A3 | c.7600T>G | Likely Pathogenic | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 9 | 4 | 14 | Yes | Yes | COL6A3 | c.4405G>C | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 10 | 3 | 4 | No | No | COL6A3 | c.5917+2T>C | Likely Pathogenic | Heterozygous | Novel |

Note: 30% consanguinity and 20% family history.

3.6.2. Emery Driefuss muscular dystrophy (MIM# 616516, MIM# 612998, MIM# 612999, MIM# 614302)

Twelve patients were diagnosed with Emery‐Driefuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD), based on variants found in the Lamin A/C (LMNA; n = 1), Nesprin 1 (SYNE1; n = 9), Nesprin 2 (SYNE2; n = 1) and LUMA (TMEM43; n = 1) genes (Table 11). EDMD is often an X‐linked, autosomal dominant muscular dystrophy wherein muscle atrophy, contractures of the joints and cardiac conduction abnormalities and cardiomyopathy are commonly encountered (rev in Heller et al., 2020). EDMD is included in a class of disorders called the nuclear envelopathies or laminopathies and include a growing group of human hereditary disorders associated with mutations within genes involved with the nuclear envelope (Bonne & Quijano‐Roy, 2013). Depending on the mutant genes associated, OMIM currently recognized seven subtypes, including EDMD1 through 7. However, over 60% of EDMD patients do not have an identifiable mutation in EMD (emerin) or LMN, the two most commonly occurring EMDA‐associated mutant genes (Bonne & Quijano‐Roy, 2013). Patients in our cohort were classified as EDMD3 (n = 1), EDMD4 (n = 9), EDMD5 (n = 1) and EDMD 7 (n = 1) (Table 11). Interestingly 50% of the variants found in our EDMD cohort were found to be novel. We estimated the age at diagnosis of the EDMD4 patients with gene variants in the SYNE1 gene to be 17.7 +/−12.6 years (Table 11, range 8–37 years).

TABLE 11.

Twelve patients with Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophies

| S. No | Age at onset | Age at diagnosis | Consanguinity | Family history | Disease | Gene | Variant identified | Classification—NGS | Zygosity | Reported/novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not available | Not Available | No | No | EDMD ‐ 3 | LMNA | c.674G>A | Pathogenic | Homozygous | Reported |

| 2 | Not available | 14 | Yes | No | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.16671T>A | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 3 | 3 | 28 | Yes | Yes | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.3752G>A | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 4 | 8 | 8 | Yes | Yes | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.13089A>T | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 5 | 5 | 8 | No | No | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.3962T>C | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 6 | 5 | 11 | No | No | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.3656C>T | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 7 | 2 | 8 | Not available | Not available | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.21222A>C | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 8 | 2 | 9 | No | No | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.7611G>T | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 9 | 2 | 37 | Yes | Yes | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.19692+3G>A | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 10 | 18 | 37 | No | No | EDMD ‐ 4 | SYNE1 | c.25907A>G | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Reported |

| 11 | 7 | 16 | Yes | Yes | EDMD ‐ 5 | SYNE2 | c.7076G>T | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Novel |

| 12 | 3 | 15 | Yes | No | EDMD ‐ 7 | TMEM43 | c.488G>A | Uncertain Significance | Heterozygous | Reported |

Note: 50% Consanguinity and 33% Family history.

3.7. Multiple co‐occurring OMD gene variants found in patients following NGS analysis

As is evident in Figure 4a and in data deposited in the LOVD database, https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals?search_owned_by_=%3D%22Lakshmi%20Bremadesam%22#order=id%2CASC&search_Individual/Reference=MDCRC%202021 the majority of OMD patients (56%) in our cohort of 105, harboured a single variant in a bona fide OMD gene. Interestingly, about one third (27.6%) of patients had two variants while 14.3% harboured three variants in the genes interrogated. Two patients (1.9%) were found to have four variants each. The first of these patients had two variants in the LAMA2 gene (Exon 15; c.2131_2134dup a 4 bp insertion and in exon 60; c.8396C>G), both variants classified as likely pathogenic, as well as two missense variants in the PLEC gene (Exon 31; c.4757G>A and Exon 32; c.13172C>T; both classified as VUS). The second patient harbored a single missense variant in the SYNE1 (exon 87; c.16671T>A; VUS) and one in the SGCA gene (exon 9; c.1109G>A; VUS) genes along with two missense variants in the NEB gene (exon 134; c.20419T>C and exon 168; c.23969C>T, both VUS). At the time of diagnosis, the first patient was ambulant and aged 14 years while the second patient was aged 13 years. At the time of writing this report, the patients were aged 27 years and 29 years respectively, but their current ambulation status not known.

FIGURE 4.

Patients with two or more variants in the genes associated with OMD, DMD or other diseases. (a) The percentage of patients in the cohort with one, two, three of four variants. (b) The number of patients with two or three variants with specific variants in bona fide genes for DMD, OMD (other muscular dystrophies) and or other disorders (Oth).

Of the patients with two and three gene variants (Figure 4b), the majority had variants in the OMD genes (2 OMD gene variants: 20 patients and three OMD gene variants: 9 patients). Clinical data was available only for a few patients with dual variants (Table 12). Two cases, both products of consanguineous marriages, with variants of unknown significance in the TMEM43 and SYNE1genes in one case (patient 1), and in the SYNE2 and ANO5 genes in the other (patient 4; Table 12), were non‐ambulant and had scoliosis. Additionally, patient 2 was semi‐ambulant and presented with scapular winging with dual variants in the PLEC and LAMA2 genes. Patient 3, on the other hand, was found to have variants of unknown significance in the SYNE1 and FLNC genes. Yet he remained asymptomatic and apparently normal. He had been tested for muscular dystrophy gene variants (Table S1) because two of his now deceased paternal uncles were symptomatic with suspected DMD. Unfortunately, the uncles did not undergo genetic testing. Never‐the‐less, this individual must remain cautious given his family history and the presence of variants in OMD associated genes.

TABLE 12.

Patients with two OMD variants and disease severity

| ID | Disease category | Type of disease | Gene | Location | Variant identified | Classification | Age at onset of symptoms | Ambulation status—at the time of diagnosis | Age at loss of ambulation | Age at diagnosis | Current age | Family history | Consanguinity | Specific symptoms, if any |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | OMD | Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐7 | TMEM43 | Exon 6 | c.488G>A | Uncertain Significance | 6 | Non Ambulant | 11 | 15 | 25 | No | Yes | Scoliosis; Patient was too lean |

| 1b | OMD | Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐4 | SYNE1 | Exon 117 | c.21436C>T | Uncertain Significance | ||||||||

| 2a | OMD | Limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy type 2Q | PLEC | Exon 14 | c.2078G>A | Uncertain Significance | 9 | Semi Ambulant | Not applicable | 12 | 21 | No | No | First symptom—Scapular winging |

| 2b | OMD | Merosin‐deficient congenital muscular dystrophy type 1A | LAMA2 | Exon 14 | c.1963C>T | Uncertain Significance | ||||||||

| 3a | OMD | Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐4 | SYNE1 | Exon 78 | c.13089A>T | Uncertain Significance | No symptom | Ambulant | Not applicable | 8 | 18 | Yes (2 paternal uncles) | Yes | Normal boy; Because of family history they were tested |

| 3b | OMD | Distal myopathy‐4, Myofibrillar myopathy‐5 | FLNC | Exon 32 | c.5363T>G | Uncertain Significance | ||||||||

| 4a | OMD | Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy‐5 | SYNE2 | Exon 45 | c.7076G>T | Uncertain Significance | 9 | Non Ambulant | 13 | 16 | 27 | No | Yes | Scoliosis; Myalgias |

| 4b | OMD | Limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy‐12 | ANO5 | Exon 9 | c.827A>T | Uncertain Significance |

Note: Patients with two OMD variants and disease severity.

A word of caution: while the contribution of one or more variants to the muscular dystrophies described may be significant, it is not possible to draw any conclusions about the contributions of these mutant genes with regard to disease causation at this time.

3.8. OMDs share overlapping clinical symptoms with DMD and are likely to be misdiagnosed in clinics that lack genetic testing options

The majority of patients included in our study had rural origins in the state of Tamil Nadu in southern India (Kumar et al., 2020). Since rural clinics are not currently equipped to diagnose muscular dystrophies using state‐of‐the‐art NGS methods, physicians in rural clinics rely heavily on clinical presentation in their approach to diagnosis. It was therefore not surprising that nearly 15% of the 961 clinically suspected DMD patients turned out to have other muscular dystrophies and other disorders as confirmed by NGS and WES analyses (see Tables 2 and 5). In order to determine why patients had been misdiagnosed, we selected nine commonly occurring DMD symptoms and asked how frequently these symptoms were observed in the other genetically confirmed muscular dystrophies in our cohort of patients. Based on our observations in Figure 5, all of the DMD‐specific symptoms considered were found to be associated with all the of OMDs encountered in our cohort, albeit with varying frequencies, when compared to patients with genetically confirmed DMD. The symptoms of delayed motor milestones were more pronounced in LGMD2B and LGMD2E, and toe walking was common in Bethlem myopathy compared to DMD (Figure 5). These conclusions however, must be viewed with caution since the number of patients with autosomal recessive disorders were limited in our study.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of symptoms observed in OMDs versus DMD demonstrates a definite overlap. A ratio of the number of patients with the nine indicated symptoms was compared with those seen in patients with DMD. (Ratio = OMD/DMD). Ratios >1 indicate greater occurrence of the symptom in the specific OMD. OMD: other muscular dystrophy: DMD Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

4. DISCUSSION

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is often diagnosed based on clinical manifestations including difficulty in walking, standing and sitting, calf muscle hypertrophy, early contractures of the Achilles tendon, leg muscle weakness, elevated creatine kinase levels, abnormal muscle biopsy coupled with a confirmed molecular analysis (Dobrescu et al., 2015). In our cohort of patients we have observed additional clinical features such as toe walking, frequent falls, Gower's sign and waddling gait (Kumar et al., 2020). The limb girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMDs), on the other hand are a class of diverse genetic disorders caused by alterations in fifteen or more genes. These genetic alterations affect the muscle fiber leading to no specific or distinct clinical features that predict the diverse genotypic variations (Moore et al., 2006). The overlapping and sometimes complex clinical manifestations make it challenging for clinicians to provide a precise clinical diagnosis based exclusively on patient symptoms. Thus patients with LGMDs could easily be mistaken for patients with DMD/BMD, especially if the latter present with milder symptoms (Nallamilli et al., 2018). This report underscores the need to precisely diagnose muscular dystrophies genetically and to implement disease management and prevention strategies through appropriate counselling programs.

Targeted next generation sequence analysis coupled with whole exome sequencing (WES) in a cohort of 961 previously described patients with clinically suspected DMD (Kumar et al., 2020) revealed that 105/961 (10.9%) had variants in genes associated with other muscular dystrophies, including Bethlem and Ullrich congential Myopathies, Emery‐Driefuss muscular dystrophy and the Limb girdle Muscular dystrophies (LGMDs). The majority of these muscular dystrophies were found to be autosomal recessive disorders, which included patients with homozygous variants as well as a few with compound heterozygous variants. Interestingly, a third of the patients with other muscular dystrophies were found to have LGMD2E, a severe form of LGMD that afflicts very young children (Semplicini et al., 2015). An additional 34/961 (3.5%) patients were found to have other disorders including the Charcot–Marie Tooth disorders and nemaline myopathy, among others. A small percentage of patients, (6/961; 0.6%) remain undiagnosed with no known variant in a bona fide OMD gene, despite having DMD‐like symptoms. Interestingly, three of these six patients had experienced frequent falls and difficulty walking at first presentation. While two of the three individuals remain ambulant at ages 28 and 14, one patient became non‐ambulant at the age of 10 years. These six cases need to be further examined, perhaps by whole genome sequencing, for precise identification of gene variants that could lead to diagnoses of their underlying conditions.

In a similar study conducted in Mexico, of 72 unrelated males aged below 18 years with clinical suspicion of muscular dystrophy and no evidence of a DMD gene deletion, NGS analysis revealed 68% with variants in the DMD gene and 12.5% with autosomal recessive LGMD‐related genotypes including LGMD types 2A‐R1, 2C‐R5, 2E‐R4, 2D‐R3 and 2I‐R9 (Alcántara‐Ortigoza et al., 2019). The absence of LGMD2B‐R2 in this study was attributed to the small number of patients included in the study.

Over 400 mutations have been reported in the CAPN3 gene, which was the first non‐structural protein to be linked to a muscular dystrophy (Richard et al., 1995). However, the role of mutant CAPN3 in contributing to the pathogenicity of LGMD2A remains unclear. It is widely known that LGMD2A is the most frequently encountered type of LGMD worldwide (Sáenz et al., 2005) and references therein. An interesting observation was made in one patient with presumed LGMD2A (Table 6, patient # 5). While this patient was heterozygous for a missense mutation in the CAPN3 gene (Exon 18; c.2033A>T) associated with LGMD 2A, further investigation identified a second heterozygous mutation in the CLCN1 gene (Exon 18; c.1667T>A), which is associated with myotonia congentia (Thomsen disease). Based on this observation, the precise diagnosis of this patient and for others with multiple mutations in OMD associated genes, even a genetic analysis remains unclear. A word of caution is therefore merited, while the contribution of one or more variants to the muscular dystrophies described may be significant, it is not possible to draw any conclusions about the contributions of these mutant genes with regard to disease causation at this time.

Of the 11 patients identified with CAPN3 variants, a surprising and significant difference in age at onset between patients #6 (age 9 years) and #7 (age 6 months) (Table 6) was observed, given that the two unrelated patients share the same mutation in the CAPN3 gene. Upon further examination of the mutational profiles of both patients, it was found that while #6 had a homozygous mutation in the CAPN3 gene (Exon 18; c.2003T>G), two additional heterozygous variants in #7 in the PLEC gene (Exon 28; c.4198G>A and Exon 32; c.8887G>A) were found. These additionally variants could potentially account for the earlier age of disease onset in the latter, suggesting that multiple mutations in genes associated with muscle function could together contribute to disease severity.

In a previous study of 238 LGMD2A patients from Europe, the mean age at disease onset was found to be 13.8+/−8.1 years, with a range of 2–49 years (Sáenz et al., 2005). In that study 30.7% of patients were found to have the c.2362AG>TCATCT insertion mutation in the CAPN3gene. This mutation was not observed in our cohort (Table 6).

LGMD2Q is characterized by proximal muscle weakness with occasional falls, difficulties climbing stairs with a progressive course leading to loss of ambulation in early adulthood caused by variants in the PLEC gene (Irwin McLean et al., 1996). Of the seven OMD patients with variants in the PLEC gene, 4 were found to have compound heterozygous variants within the PLEC gene. On the other hand, 3/7 patients had heterozygous variants in the PLEC gene as well as additional variants in the DYSF (Exon 34; c.3779G>A and intron 34; c.3898‐4C>G) and LAMA2 (Exon 14; c.1963C>T) genes (Table 8). Furthermore, patients 1 and 6 harbored heterozygous PLEC gene variants alone. Thus, further analyses of these patients may shed light on whether single or multiple variants in the PLEC gene, coupled with other variants in genes associated with OMDs, could contribute to disease.

A third of the patients in our cohort with autosomal recessive muscular dystrophies were found to have variants in the SGCB gene associated with LGMD2E.While the clinical symptoms of LGMD2E vary, the age at diagnosis is usually under the age of 10 years. Loss of ambulation follows in the mid‐late teens (Semplicini et al., 2015). Nearly two thirds of the 29 LGMD2E patients in our cohort were products of consanguineous marriages. Interestingly, 18/29 unrelated patients, all belonging to the state of Tamil Nadu, harboured the same c.544A>C variant in exon 4 of the SGCB gene, which could likely disrupt the integrity of the dystroglycan complex (Xie et al., 2019). Similar results were observed in eight Iranian families with the same haplotype harbouring a pathogenic mutation in the SGCB gene leading to the deletion of exon 2, which contributes to the trans‐membrane domain of the β‐sarcoglycan protein. A founder effect was also suggested in this study (Mojbafan et al., 2020). In a second study from Iran, Alavi et al. showed that 12 out of 14 LGMD2E patients had a deletion mutation resulting in the loss of exon 2 in SGCB gene. Interestingly, 10 of 12 patients with this deletion were from the south and south‐east of Iran and haplotype analysis based on three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) markers strongly suggested the possibility of a founder effect (Alavi et al., 2017). Finding the same mutation in the SGCB gene in multiple unrelated patients in our cohort, hailing from the same geographic region within the state of Tamil Nadu in India, is suggestive of a founder effect. Confirmation of this suggested finding will require more patient samples and additional analysis. This is the first report of multiple patients with the c.544A>C point variant in LGMD2E patients from India.

It has been previously shown that LGMD2E is among the most severe forms of the LGMDs. Data from our cohort of patients confirm this and further demonstrate that when comparing the age at onset of disease and the age at loss of ambulation, both LGMD2E and DMD are comparable. This observation may explain the large numbers of LGMD2E patients who were mistakenly thought to be ones with DMD, in our cohort.

Our analyses specifically demonstrate that diagnosis of patients based only on symptoms is not recommended as it could lead to the misdiagnosis of DMD in upto 15% of cases, as we observed in our cohort. Genetic analysis by NGS using a well‐defined muscular dystrophy panel is therefore highly recommended and should be included as part of our previously recommended diagnostic workflow (Figure 1 and Kumar et al., 2020) of patients presenting with DMD‐like symptoms. The results using this approach could impact treatment as well as counselling of patients and their families, thus playing a vital role in patient well‐being.

No epidemiological conclusions should be derived from our study regarding the prevalence of the LGMDs and other autosomal recessive diseases in the state of Tamil Nadu, India, largely because our study was originally designed to identify and diagnose patients with DMD, and therefore only males have been considered in this study (Kumar et al., 2020).

With the complete genetic analyses of the 961 clinically suspected DMD patients our findings demonstrated that about 15% of patients can be misdiagnosed with having DMD based on clinical criteria alone. This study underscores the need for a complete genetic work up to precisely diagnose patients with muscular dystrophies and myopathies. Thus, suspected muscular dystrophy cases, particularly those suspected with DMD, who do not have a confirmed molecular diagnosis after mPCR and MLPA analysis need to be investigated by next generation sequencing. This effort would confirm the muscular dystrophy type so that appropriate counselling programs could be initiated as early as possible to inform prevention strategies and initiate treatment regimens, if any. These comprehensive efforts are intended to improve the quality of life of patients and to empower carrier females, where applicable, and parents in consanguineous marriages to make informed reproductive choices to impede the propagation of muscular dystrophies in the community.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

All procedures performed in this protocol involving human subjects were in compliance with the ethical standards of our institution (MDCRC, Coimbatore, TN, India) and in line with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. This protocol has been approved by the MDCRC Ethics Committee (MDCRC/03/IEC‐DMD016).

Supporting information

Table S1:

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the patients and their families involved in this study. We also thank the clinicians associated with MDCRC for sending clinical details, written consent forms and patient samples as per our Centre format. We acknowledge and thank all our charitable donors and funding agencies for their financial assistance that enabled us to provide free of cost diagnostics and counselling to all our patients.

Karthikeyan, P. , Kumar, S. H. , Khanna‐Gupta, A. , & Bremadesam Raman, L. (2024). In a cohort of 961 clinically suspected Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients, 105 were diagnosed to have other muscular dystrophies (OMDs), with LGMD2E (variant SGCB c.544A>C) being the most common. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 12, e2123. 10.1002/mgg3.2123

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All the variants identified in this study have been submitted to the “Global Variome shared LOVD” (www.lovd.nl) and that they can be accessed using the URL https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals?search_owned_by_=%3D%22Lakshmi%20Bremadesam%22#order=id%2CASC&search_Individual/Reference=MDCRC%202021.

REFERENCES

- Alavi, A. , Esmaeili, S. , Nilipour, Y. , Nafissi, S. , Tonekaboni, S. H. , Zamani, G. , Ashrafi, M. R. , Kahrizi, K. , Najmabadi, H. , & Jazayeri, F. (2017). LGMD2E is the most common type of sarcoglycanopathies in the Iranian population. Journal of Neurogenetics, 31, 161–169. 10.1080/01677063.2017.1346093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara‐Ortigoza, M. A. , Reyna‐Fabián, M. E. , González‐Del Angel, A. , Estandia‐Ortega, B. , Bermúdez‐López, C. , Cruz‐Miranda, G. M. , & Ruíz‐García, M. (2019). Predominance of dystrophinopathy genotypes in mexican male patients presenting as muscular dystrophy with a normal multiplex polymerase chain reaction DMD gene result: A study including targeted next‐generation sequencing. Genes, 10(11), 856. 10.3390/genes10110856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnkrant, D. J. , Bushby, K. , Bann, C. M. , Alman, B. A. , Apkon, S. D. , Blackwell, A. , Case, L. E. , Cripe, L. , Hadjiyannakis, S. , Olson, A. K. , Sheehan, D. W. , Bolen, J. , Weber, D. R. , Ward, L. M. , & DMD Care Considerations Working Group . (2018). Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 2: Respiratory, cardiac, bone health, and orthopaedic management. The Lancet Neurology, 17, 347–361. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30025-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonne, G. , & Quijano‐Roy, S. (2013). Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, laminopathies, and other nuclear envelopathies. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 113, 1367–1376. 10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushby, K. M. D. , Collins, J. , & Hicks, D. (2014). Collagen type VI myopathies. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 802, 185–199. 10.1007/978-94-7-7893-1_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciottolo, M. , Numitone, G. , Aurino, S. , Caserta, I. R. , Fanin, M. , Politano, L. , Minetti, C. , Ricci, E. , Piluso, G. , Angelini, C. , & Nigro, V. (2011). Muscular dystrophy with marked Dysferlin deficiency is consistently caused by primary dysferlin gene mutations. European Journal of Human Genetics, 19, 974–980. 10.1038/ejhg.2011.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centerwall, W. R. , & Centerwall, S. A. (1966). Consanguinity and congenital anomalies in South India: A pilot study. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 54, 1160–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrescu, M. A. , Petrescu, I. O. , Tache, D. E. , Farcas, S. , Puiu, M. , Stanoiu, B. , Tudorache, I. , & Bastian, A. (2015). Diagnosis management strategy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Jurnalul Pediatrului, 18, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, D. J. , Gorospe, J. R. , Fanin, M. , Hoffman, E. P. , Angelini, C. , Pegoraro, E. , Noguchi, S. , Ozawa, E. , Pendlebury, W. , Waclawik, A. J. , & Kuncl, R. W. (1997). Mutations in the Sarcoglycan genes in patients with myopathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 336, 618–625. 10.1056/nejm199702273360904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A. G. , Shen, X. M. , Selcen, D. , & Sine, S. M. (2015). Congenital myasthenic syndromes: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 14, 420–434. 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70201-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundesli, H. , Talim, B. , Korkusuz, P. , Balci‐Hayta, B. , Cirak, S. , Akarsu, N. A. , Topaloglu, H. , & Dincer, P. (2010). Mutation in exon 1f of PLEC, leading to disruption of plectin isoform 1f, causes autosomal‐recessive limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy. American Journal of Human Genetics, 87, 834–841. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller, S. A. , Shih, R. , Kalra, R. , & Kang, P. B. (2020). Emery‐Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Muscle and Nerve, 61, 436–448. 10.1002/mus.26782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, W. , Pulkkinen, L. , Smith, F. J. D. , Rugg, E. L. , Lane, E. B. , Bullrich, F. , Burgeson, R. E. , Amano, S. , Hudson, D. L. , Owaribe, K. , McGrath, J. , McMillan, J. , Eady, R. A. , Leigh, I. M. , Christiano, A. M. , & Uitto, J. (1996). Loss of plectin causes epidermolysis bullosa with muscular dystrophy: cDNA cloning and genomic organization. Genes and Development, 10, 1724–1735. 10.1101/gad.10.14.1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. H. , Athimoolam, K. , Suraj, M. , das Christu Das, M. , Muralidharan, A. , Jeyam, D. , Ashokan, J. , Karthikeyan, P. , Krishna, R. , Khanna‐Gupta, A. , & Bremadesam Raman, L. (2020). Comprehensive genetic analysis of 961 unrelated Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients: Focus on diagnosis, prevention and therapeutic possibilities. PLoS One, 15(6), e0232654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. A. , Dykes, D. D. , & Polesky, H. F. (1988). A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Research, 16, 1215. 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojbafan, M. , Bahmani, R. , Bagheri, S. D. , Sharifi, Z. , & Zeinali, S. (2020). Mutational spectrum of autosomal recessive limb‐girdle muscular dystrophies in a cohort of 112 Iranian patients and reporting of a possible founder effect. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 15, 14. 10.1186/s13023-020-1296-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S. A. , Shilling, C. J. , Westra, S. , Wall, C. , Wicklund, M. P. , Stolle, C. , Brown, C. A. , Michele, D. E. , Piccolo, F. , Winder, T. L. , Stence, A. , Barresi, R. , King, N. , King, W. , Florence, J. , Campbell, K. P. , Fenichel, G. M. , Stedman, H. H. , Kissel, J. T. , … Mendell, J. R. (2006). Limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy in the United States. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 65, 995–1003. 10.1097/01.jnen.0000235854.77716.6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morena, J. , Gupta, A. , & Hoyle, J. C. (2019). Charcot‐marie‐tooth: From molecules to therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(14), 3419. 10.3390/ijms20143419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallamilli, B. R. R. , Chakravorty, S. , Kesari, A. , Tanner, A. , Ankala, A. , Schneider, T. , da Silva, C. , Beadling, R. , Alexander, J. J. , Askree, S. H. , Whitt, Z. , Bean, L. , Collins, C. , Khadilkar, S. , Gaitonde, P. , Dastur, R. , Wicklund, M. , Mozaffar, T. , Harms, M. , … Hegde, M. (2018). Genetic landscape and novel disease mechanisms from a large LGMD cohort of 4656 patients. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, 5, 1574–1587. 10.1002/acn3.649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, I. , Broux, O. , Allamand, V. , Fougerousse, F. , Chiannilkulchai, N. , Bourg, N. , Brenguier, L. , Devaud, C. , Pasturaud, P. , Roudaut, C. , Hillaire, D. , Passos‐Bueno, M.‐R. , Zatz, M. , Tischfield, J. A. , Fardeau, M. , Jackson, C. E. , Cohen, D. , & Beckmann, J. S. (1995). Mutations in the proteolytic enzyme calpain 3 cause limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Cell, 81(1), 27–40. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90368-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, S. , Leadley, R. M. , Armstrong, N. , Westwood, M. , de Kock, S. , Butt, T. , Jain, M. , & Kleijnen, J. (2017). The burden, epidemiology, costs and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: An evidence review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 12, 79. 10.1186/s13023-017-0631-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz, A. , Leturcq, F. , Cobo, A. M. , Poza, J. J. , Ferrer, X. , Otaegui, D. , Camaño, P. , Urtasun, M. , Vílchez, J. , Gutiérrez‐Rivas, E. , Emparanza, J. , Merlini, L. , Paisán, C. , Goicoechea, M. , Blázquez, L. , Eymard, B. , Lochmuller, H. , Walter, M. , Bonnemann, C. , … López de Munain, A. (2005). LGMD2A: Genotype‐phenotype correlations based on a large mutational survey on the calpain 3 gene. Brain, 128(4), 732–742. 10.1093/brain/awh408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakthivel Murugan, S. M. , Chandramohan, A. , & Lakshmi, B. R. (2010). Use of multiplex ligation‐dependent probe amplification (MLPA) for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) gene mutation analysis. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 132(3), 303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarese, M. , Sarparanta, J. , Vihola, A. , Jonson, P. H. , Johari, M. , Rusanen, S. , Hackman, P. , & Udd, B. (2020). Panorama of the distal myopathies. Acta Myologica, 39, 245–265. 10.36185/2532-1900-028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semplicini, C. , Vissing, J. , Dahlqvist, J. R. , Stojkovic, T. , Bello, L. , Witting, N. , Duno, M. , Leturcq, F. , Bertolin, C. , D'Ambrosio, P. , Eymard, B. , Angelini, C. , Politano, L. , Laforêt, P. , & Pegoraro, E. (2015). Clinical and genetic spectrum in limb‐girdle muscular dystrophy type 2 E. Neurology, 84(17), 1772–1781. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewry, C. A. , Laitila, J. M. , & Wallgren‐Pettersson, C. (2019). Nemaline myopathies: A current view. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility, 40, 111–126. 10.1007/s10974-019-09519-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaart, I. E. C. , & Aartsma‐Rus, A. (2019). Therapeutic developments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature Reviews Neurology, 15, 373–386. 10.1038/s41582-019-0203-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z. , Hou, Y. , Yu, M. , Liu, Y. , Fan, Y. , Zhang, W. , Wang, Z. , Xiong, H. , & Yuan, Y. (2019). Clinical and genetic spectrum of sarcoglycanopathies in a large cohort of Chinese patients. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 14, 43. 10.1186/s13023-019-1021-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1:

Data Availability Statement

All the variants identified in this study have been submitted to the “Global Variome shared LOVD” (www.lovd.nl) and that they can be accessed using the URL https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals?search_owned_by_=%3D%22Lakshmi%20Bremadesam%22#order=id%2CASC&search_Individual/Reference=MDCRC%202021.