Abstract

Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato (s.l.) is an ixodid tick found in the semi-arid southwestern United States and northern Mexico where it is a parasite of medical and veterinary significance, including as a vector for Rickettsia parkeri, a cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the Americas. To describe the comprehensive natural history of this tick, monthly small mammal trapping and avian mist netting sessions were conducted at sites in Cochise County Arizona, within the Madrean Archipelago region where human cases of R. parkeri rickettsiosis and adult stages of A. maculatum s.l. were previously documented. A total of 1949 larvae and nymphs were removed from nine taxonomic groups of rodents and ten species of birds and were used in combination with records for adult stages collected both from vegetation and hunter-harvested animals to model seasonal activity patterns. A univoltine phenology was observed, initiated by the onset of the annual North American monsoon and ceasing during the hot, dry conditions preceding the following monsoon season. Cotton rats (Sigmodon spp.) were significantly more likely to be infested than other rodent taxa and carried the highest tick loads, reflecting a mutual affinity of host and ectoparasite for microhabitats dominated by grass.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-78507-y.

Subject terms: Ecology, Ecological epidemiology, Entomology

Introduction

The Amblyomma (Anastosiella) maculatum complex includes three species broadly distributed within the Neotropical (A. triste, A. tigrinum, and A. maculatum) and Nearctic (A. maculatum) ecoregions of the Americas1. Members of this group share morphological features, exhibit a three-host life cycle, and are recognized for their importance as livestock pests and as vectors of medical and veterinary pathogens2. Rickettsia parkeri is an intracellular pathogen transmitted by ticks that can manifest in humans as a moderately severe spotted fever rickettsiosis, frequently with an inoculation eschar at the site of tick bite. In the United States (U.S.), A. maculatum complex ticks are associated with R. parkeri sensu stricto (s.s) strains3,4 and R. parkeri rickettsiosis had been reported only in the Gulf Coast and the mid-Atlantic regions prior to 2014, when cases were identified in southern Arizona and determined to be associated with A. maculatum sensu lato (s.l.) tick bites5,6. These ticks are recognized as close phylogenetic relatives of both A. maculatum s.s. (Gulf Coast tick) and A. triste s.s., though further resolution is required to determine the precise taxonomic relationship7–9. Follow up investigations have identified adult stage A. maculatum s.l. ticks present within or proximal to ‘sky islands’, habitat characterized as fragmented chains of forested mountains separated by broad valleys in semi-desert regions of southern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, northern Mexico, and West Texas10–13. While A. maculatum group ticks typically inhabit coastal uplands, tallgrass prairie, and savannah ecosystems with ample annual rainfall,14,15, the climate of the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico is comparatively arid for most of the year, with extreme high and low temperatures and highly seasonal precipitation presenting a potentially more inhospitable macroenvironment for hard ticks16. The irregular spatial distribution of A. maculatum s.l. and its association with riparian and montane grassland habitats within the North American Madrean sky islands suggests that this tick may be a relict population of historical periods when warm moist conditions sustained expansive grasslands in the region17,18, which in turn may have supported a broader, more contiguous distribution of these ticks than exists in the current environment.

Limiting adverse impacts of ticks and tick-borne pathogens requires a detailed understanding of the natural history, including seasonal activity patterns of the ticks and identification of the vertebrate hosts ticks parasitize as obligate blood-feeders. Previous studies in the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico have focused exclusively on the adult stage of A. maculatum s.l10–13. which is presumably the primary life stage associated with transmission of R. parkeri to humans5,6. The few immature stage specimen records for A. maculatum s.l. in this region prior to this study consisted of nymphs and a larva collected from avian hosts (passerines and near passerines)9,19, which have been previously shown to transport ticks from neotropical regions to the continental U.S. during annual migration20. Free-ranging immature stages of A. maculatum are difficult to collect using flagging or drag cloth sampling21,22 whereas vertebrate hosts are often useful as aggregators of ticks. Therefore, the goals of this study were to determine the relative contributions of small mammals and birds as hosts for A. maculatum s.l. and to describe the phenology for active stages of these ticks in the region.

Results

Ticks

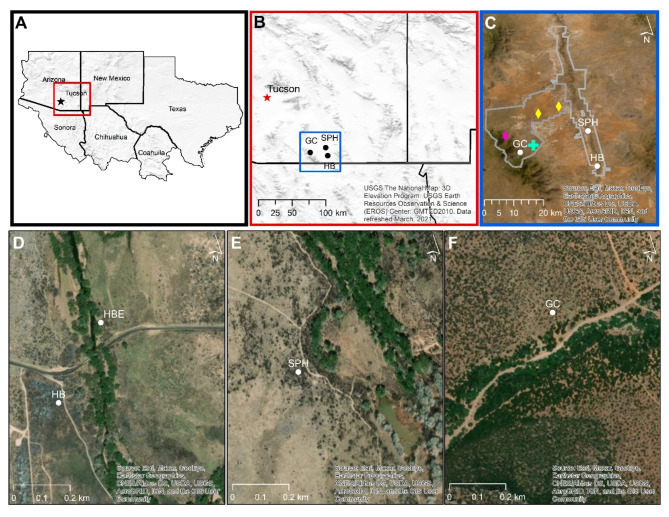

Immature life stages of A. maculatum s.l. were collected from small mammals (all four sites) and avian hosts (San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area [SPRNCA] sites only), and adults were collected from mammalian hosts at Middle Garden Canyon and Ft. Huachuca (GC), and vegetation (all sites) (Figs. 1 and 2a–c). Haemaphysalis leporispalustris immatures (Fig. 2d) were recorded from bird hosts only and no other tick species were collected during our sampling efforts. Table 1 summarizes 1949 immature stage A. maculatum s.l. ticks (1163 larvae and 786 nymphs) collected from small mammals (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 2). A total of 703 larvae (0.692 mean per host) and 464 nymphs (0.457) were collected from primary captures of small mammals and 460 larvae (0.785) and 322 nymphs (0.549) were removed from recaptured small mammals (S1). These differences were most likely a result of Sigmodon species accounting for a greater proportion of recaptures compared to primary captures (S2). Table 2 summarizes tick collections from small mammals by project location, where inter-site variability small mammal community composition and tick load was greatest between GC and the SPRNCA sites (Table 2). A total of 30 A. maculatum s.l. (9 larvae, 21 nymphs) and 10 H. leporispalustris (4 larvae, 6 nymphs) were removed from birds (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Study locations in southern Arizona 2022–2023. A & B – regional (A) and site location (B) maps. Ft. Huachuca and San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area are depicted (C) with boundaries outlined (gray), and locations of hunter harvested ticks for mule deer (yellow diamonds), white-tailed deer (aqua cross) and coyote (fuchsia diamond). Satellite images of sampling sites are shown for (D) Hereford Bridge (HB) post-wildfire, and Hereford Bridge East (HB/HBE), (E) San Pedro House (SPH), and (F) Middle Garden Canyon (GC).

Fig. 2.

Images of ticks collected in this study at Cochise County AZ sites. (A) Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato larval stage, inset – engorged larva. (B) Amblyomma maculatum s.l. nymphal stage, inset – engorged nymph. (C) Amblyomma maculatum s.l. adult females removed from a deer. (D) Haemaphysalis leporispalustris immature stages removed from birds (nymph-top, larva-bottom).

Table 1.

Summary of rodents captured at field sites in Cochise County, AZ with life stage-specific tick loads.

| Species | No. individuals captured | Total no. processed (recaptures) | No. infested (%) | Total larvae | Mean no. larvae (range) | Total nymphs | Mean no. nymphs (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family (Subfamily) | |||||||

| Cricetidae (Sigmodontinae) | |||||||

| Sigmodon arizonae | 350 | 624 (274) | 240 (38.5) | 840 | 1.35 (0-130) | 657 | 1.05 (0-33) |

| Sigmodon ochrognathus | 62 | 104 (42) | 33 (31.7) | 29 | 0.279 (0-29) | 60 | 0.577 (0-7) |

| Cricetidae (Neotominae) | |||||||

| Peromyscus spp. | 323 | 512 (189) | 78 (15.2) | 206 | 0.402 (0-16) | 56 | 0.109 (0-4) |

| Reithrodontomys montanus | 46 | 49 (3) | 6 (12.2) | 7 | 0.143 (0-3) | 3 | 0.061 (0-1) |

| Neotoma albigula | 29 | 52 (23) | 11 (21.2) | 25 | 0.481 (0-6) | 3 | 0.058 (0-3) |

| Onychomys torridus | 7 | 13 (6) | 3 (23.1) | 3 | 0.231 (0-3) | 2 | 0.154 (0-2) |

| Heteromyidae (Perognathinae) | |||||||

| Chaetodipus intermedius | 148 | 182 (34) | 17 (9.34) | 38 | 0.209 (0-20) | 3 | 0.016 (0-4) |

| Chaetodipus hispidus | 7 | 8 (1) | 1 (12.5) | 5 | 0.625 (0-5) | 1 | 0.125 (0-1) |

| Perognathus flavus | 5 | 5 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heteromyidae (Dipodomyinae) | |||||||

| Dipodomys merriami | 38 | 52 (14) | 5 (9.61) | 10 | 0.192 (0-4) | 1 | 0.019 (0-1) |

| Sciuridae (Xerinae) | |||||||

| Otospermophilus variegatus | 1 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1016 | 1602 | 394 (24.6) | 1163 | 0.726 (0-130) | 786 | 0.491 (0-33) |

All ticks were morphologically identified to Amblyomma maculatum complex and considered A. maculatum sensu lato. The heading No. Individuals Captured indicates animals captured for the first time and Total No. Processed includes individuals captured for the first time plus all instances of recapture. Because most animals were uninfested with ticks, the mean number of ticks infesting each group was listed instead of median.

Table 2.

Site specific capture of small mammals and Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato ticks.

| Species | Individuals Captured (% Site Total) | Captured + Recaptured Total (% Infested) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC | SPH | HB | HBE | GC | SPH | HB | HBE | |

| Family (Subfamily) | ||||||||

| Cricetidae (Sigmodontinae) | ||||||||

| Sigmodon arizonae | – | 124 (36.3) | 148 (56.3) | 78 (57.8) | – | 211 (27.0) | 241 (53.9) | 172 (30.8) |

| Sigmodon ochrognathus | 62 (22.5) | – | – | – | 104 (31.7) | – | – | – |

| Cricetidae (Neotominae) | ||||||||

| Peromyscus spp. | 108 (50.5) | 105 (30.7) | 64 (24.3) | 46 (34.1) | 190 (4.7) | 141 (9.9) | 91 (34.1) | 90 (26.7) |

| Reithrodontomys montanus | 11 (4.0) | 16 (4.7) | 17 (6.5) | 2 (1.5) | 11 (9.0) | 18 (0) | 18 (16.7) | 2 (100) |

| Neotoma albigula | 2 (0.7) | 14 (4.1) | 7 (2.7) | 6 (4.4) | 2 (50.0) | 18 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 24 (16.7) |

| Onychomys torridus | 0 | 4 (1.2) | 3 (1.1) | – | – | 9 (22.2) | 4 (25.0) | – |

| Heteromyidae (Perognathinae) | ||||||||

| Chaetodipus intermedius | 85 (30.1) | 51 (14.9) | 10 (3.8) | 2 (1.5) | 106 (2.8) | 60 (16.7) | 13 (23.1) | 3 (1.0) |

| Chaetodipus hispidus | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.2) | – | – | 3 (0) | 5 (20.0) | – | – |

| Perognathus flavus | 5 (1.8) | – | – | – | 5 (0) | – | – | – |

| Heteromyidae (Dipodomyinae) | ||||||||

| Dipodomys merriami | 0 | 24 (7.0) | 14 (5.3) | – | – | 35 (8.6) | 17 (11.8) | – |

| Sciuridae (Xerinae) | ||||||||

| Otospermophilus variegatus | – | – | – | 1 (0.7) | – | – | – | 1 (0) |

| Total | 276 | 342 | 263 | 135 | 421 (11.1) | 497 (18.3) | 392 (43.9) | 292 (28.8) |

| Species | Amblyomma maculatum s.l. Larvae Total (Range) | Amblyomma maculatum s.l. Nymphs Total (Range) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC | SPH | HB | HBE | GC | SPH | HB | HBE | |

| Family (Subfamily) | ||||||||

| Cricetidae (Sigmodontinae) | ||||||||

| Sigmodon arizonae | – | 79 (0-23) | 341 (0-130) | 420 (0-40) | – | 80 (0-6) | 553 (0-33) | 20 (0-6) |

| Sigmodon ochrognathus | 29 (0-29) | – | – | – | 60 (0-7) | – | – | – |

| Cricetidae (Neotominae) | ||||||||

| Peromyscus spp. | 3 (0-1) | 60 (0-16) | 45 (0-12) | 98 (0-14) | 6 (0-1) | 2 (0-1) | 48 (0-4) | 0 |

| Reithrodontomys montanus | 3 (0-3) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0-2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0-1) | 0 |

| Neotoma albigula | 2 (0-2) | 14 (0-6) | 1 (0-1) | 8 (0-3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0-3) | 0 |

| Onychomys torridus | – | 3 (0-3) | 0 | – | – | 1 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | – |

| Heteromyidae (Perognathinae) | ||||||||

| Chaetodipus intermedius | 2 (0-1) | 31 (0-20) | 4 (0-2) | 1 (0-1) | 2 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 0 | 0 |

| Chaetodipus hispidus | 0 | 5 (0-5) | 0 | – | 0 | 1 (0-1) | 0 | – |

| Perognathus flavus | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | – | – | – |

| Heteromyidae (Dipodomyinae) | ||||||||

| Dipodomys merriami | – | 8 (0-4) | 2 (0-1) | – | – | 1 (0-1) | 0 | – |

| Sciuridae (Xerinae) | ||||||||

| Otospermophilus variegatus | – | – | – | 0 | – | – | – | 0 |

| Total | 39 (0-29) | 200 (0-23) | 393 (0-130) | 531 (0-40) | 68 (0-7) | 86 (0-6) | 608 (0-33) | 20 (0-6) |

Capture totals are listed for small mammal groups for Individuals Captured (first time captured) and Captured + Recaptured Total (first captures and recaptures combined). The percentage of total small mammal captures at a site that was comprised of specific taxonomic groups is listed in parentheses, and the percentage of individuals within each taxon of small mammals that were infested with ticks is listed in parentheses. Total ticks collected from each small mammal species at a site are listed with range in tick load listed in parentheses for individual hosts. Sampling sites are abbreviated as GC (Middle Garden Canyon), SPH (San Pedro House), HB (Hereford Bridge), and HBE (Hereford Bridge East).

Table 3.

List of avifauna captured in the study with tick infestation totals and category of foraging behavior listed for each species.

| Species | Common name | No. Caught | No. Infested | Amblyomma maculatum s.l. | Haemaphysalis leporispalustris | Foraging Location (> 50% of Foraging Time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order, Family | ||||||

| Galliformes, Odontophoridae | ||||||

| Callipepla gambelii | Gambel’s quail | 2 | 1 | 4 N | Ground | |

| Columbiformes, Columbidae | ||||||

| Columbina passerina | Common ground dove | 5 | Ground | |||

| Piciformes, Picidae | ||||||

| Picoides scalaris | Ladder-backed woodpecker | 1 | Mixed- Mid/Upper | |||

| Melanerpes uropygialis | Gila woodpecker | 3 | Mixed- Mid/Upper | |||

| Passeriformes, Tyrannidae | ||||||

| Myiarchus tyrannulus | Brown-crested flycatcher | 2 | Upper/Aerial | |||

| Pyrocephalus rubinus | Vermilion flycatcher | 7 | Upper/Aerial | |||

| Empidonax oberholseri | Dusky flycatcher | 3 | Upper/Aerial | |||

| Empidonax sp. | Flycatcher species | 1 | Upper/Aerial | |||

| Empidonax wrightii | Gray flycatcher | 1 | Upper/Aerial | |||

| Passeriformes, Vireonidae | ||||||

| Vireo plumbeus | Plumbeours vireo | 1 | Mixed - Mid/Upper | |||

| Vireo bellii | Bell’s vireo | 12 | Upper | |||

| Vireo huttoni | Hutton’s vireo | 1 | Upper | |||

| Passeriformes, Corvidae | ||||||

| Molothrus ater | Brown-headed cowbird | 3 | Ground | |||

| Passeriformes, Cardinalidae | ||||||

| Cardinalis cardinalis | Northern Cardinal | 2 | Ground | |||

| Cardinalis sinuatus | Pyrrhuloxia | 2 | Ground | |||

| Passerina ciris | Painted bunting | 1 | Upper | |||

| Passeriformes, Parulidae | ||||||

| Dendroica petechia | Yellow warbler | 15 | Mixed - Mid/Upper | |||

| Dendroica coronata | Yellow-rumped warbler | 19 | Upper | |||

| Geothlypis trichas | Common yellowthroat | 28 | Mixed - Ground/Low/Mid | |||

| Icteria virens | Yellow-breaster chat | 23 | Upper | |||

| Spizella breweri | Brewer’s sparrow | 2 | 1 | 1 N | Mixed - Ground/Lower/Mid | |

| Vermivora celata | Orange-crowned warbler | 2 | Upper | |||

| Vermivora luciae | Lucy’s warbler | 5 | Upper | |||

| Wilsonia pusilla | Wilson’s warbler | 8 | Upper | |||

| Passeriformes, Fringillidae | ||||||

| Carduelis psaltria | Lesser goldfinch | 13 | Upper | |||

| Carpodacus mexicanus | House finch | 3 | Upper | |||

| Passeriformes, Passerellidae | ||||||

| Melospiza lincolnii | Lincoln’s sparrow | 7 | 4 | 7 N | Ground | |

| Melospiza melodia | Song sparrow | 23 | 6 | 1 L, 4 N | 1 L, 1 N | Ground |

| Pipilo aberti | Abert’s towhee | 8 | 1 | 1 N | Ground | |

| Pipilo chlorurus | Green-tailed towhee | 6 | Ground | |||

| Zonotrichia leucophrys | White-crowned sparrow | 28 | 1 | 1 N | Ground | |

| Passeriformes, Troglodytidae | ||||||

| Thryomanes bewickii | Bewick’s wren | 6 | 3 | 6 N | 1 L | Mixed - Ground/Lower |

| Troglodytes aedon | House wren | 2 | 2 | 8 L, 1 N | Mixed - Ground/Lower | |

| Passeriformes, Mimidae | ||||||

| Toxostoma crissale | Crissal thrasher | 1 | 1 | 1 L, 1 N | Ground | |

| Toxostoma curirostre | Curve-billed thrasher | 1 | 1 | 1 L | Ground | |

| Passeriformes, Sittidae | ||||||

| Sitta carolinensis | White-breasted nuthatch | 1 | Upper | |||

| Passeriformes, Regulidae | ||||||

| Regulus calendula | Ruby-crowned kinglet | 9 | Upper | |||

| Passeriformes, Turdidae | ||||||

| Catharus guttatus | Hermit thrush | 1 | Ground | |||

| Catharus ustulatus | Swainson’s thrush | 1 | Mixed - Ground/Low/Mid | |||

| Passeriformes, Pycnonotidae | ||||||

| Turdus migratorius | American robin | 1 | Ground | |||

| Total | 263 | 21 | 9L, 21N | 4L, 6N | ||

No. Caught specifies the number of a bird species processed, and No. Infested indicates individuals of a species infested with ticks. The total number of ticks collected from each bird species is indicated along with specific life stage under the two species of ticks encountered in this study. Nymphs and larvae are abbreviated as N and L.

Taxonomic order authority is Chesser, R. T., S. M. Billerman, K. J. Burns, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, B. E. Hernández -Baños, R. A. Jiménez, A. W. Kratter, N. A. Mason, P. C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, Jr., and K. Winker. 2023. Check-list of North American Birds (online). American Ornithological Society. https://checklist.americanornithology.org/taxa/.

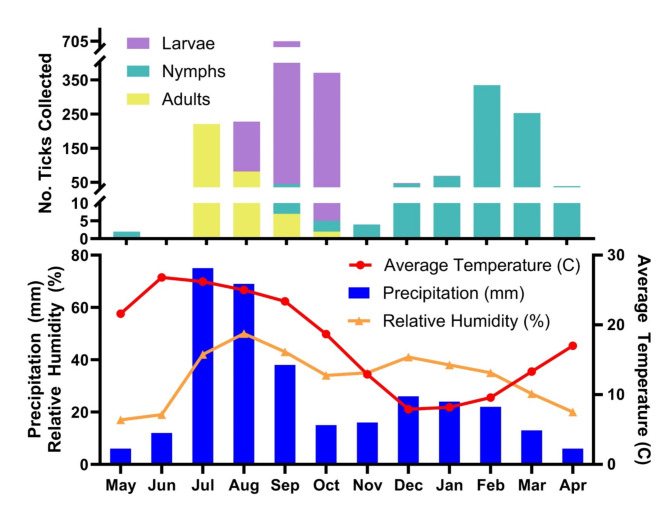

Thirteen adult ticks (nine females, four males), all identified as A. maculatum s.l. were collected by hunters on site at Ft. Huachuca between August and early October 2023. One male and one female tick and two female ticks respectively were removed from two mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). One white-tailed deer (O. virginianus) was infested with four female and three male ticks and two female ticks were removed from a coyote (Canis latrans) (S2). A total of 299 questing adult A. maculatum s.l. were collected from vegetation at the San Pedro House (SPH), Hereford Bridge (HB), and Hereford Bridge East (HBE) locations in July, August, and September of 2022 and 2023. The majority of adults (74%) were collected during the month of July (Figs. 3 and 4) and most were collected during the months when precipitation and relative humidity were highest (Fig. 4).

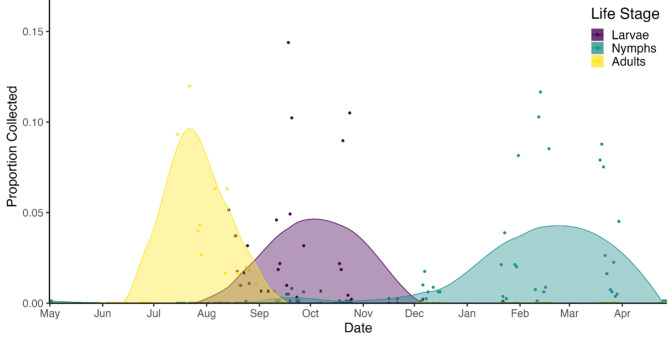

Fig. 3.

Tick phenology. Seasonal activity of adult, nymphal, and larval life stages of Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato were estimated based on the tick numbers collected by calendar date in proportion to the total number of that life stage collected on all dates. Dots represent actual counts for a specific date while curves represent model estimates spanning all dates. Yellow dots represent host-seeking adults collected from vegetation, yellow dots overlayed with a black X represent adults collected from hunter-harvested mammals, and green (nymphs) and purple (larvae) dots represent ticks removed from small mammals and birds. Two data points for adults (0.22 & 0.18) lie outside of the y-axis scale used to emphasize the curves but are included in the data used to create this model.

Fig. 4.

Monthly tick collection and climate conditions. The bars on the top panel represent the quantity of each Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato life stage collected by month and the bottom panel displays the monthly averages over 30 years (1991–2021) for climate conditions in Sierra Vista, AZ. The annual monsoon in southern Arizona begins late June or shortly thereafter and ends in September. Archived climate conditions for Sierra Vista, AZ were accessed from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

Amblyomma maculatum s.l.collection records from one or more types of sampling used in this study were obtained for 119 calendar days. These included a total of 1,184 larvae and 809 nymphs from mammals and birds, and 312 adults from vegetation or hunter harvested animals as data points in the phenology model (Fig. 3, S3). Collection records were also plotted with monthly averages (1991–2021, European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) for daily temperature, humidity, and precipitation at nearby Sierra Vista, AZ to demonstrate the relationship between tick activity and climate (Fig. 4). One or both stages of immature A. maculatum s.l. were found present in each calendar month except June and July. Adults and larvae were simultaneously active for at least 54 days, larvae and nymphs for 134 days, and all three stages were recorded over a span of 26 days (Table 4).

Table 4.

Duration of activity periods of Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato life stages.

| Stage | Earliest date | Latest date | Range (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larvae | 16-Aug | 24-Jan | 161 d |

| Nymphs | 13-Sep | 04-May | 233 d |

| Adults | 17-Jul | 09-Oct | 91 d* |

| Larvae + nymphs | 13-Sep | 24-Jan | 134 d |

| Larvae + adults | 16-Aug | 09-Oct | 54 d |

| Nymphs + adults | 13-Sep | 09-Oct | 26 d |

| Larvae + nymphs + adults | 13-Sep | 09-Oct | 26 d |

Earliest and latest dates indicate the first and last chronological dates ticks were collected during field sampling 2022–2023. *Because monthly sampling was not performed in July prior to the day adults were encountered (July 17th), we used July 10th to calculate known range of activity based on previously published results by Hecht et al. 202011.

Small mammals

In total, 1602 captured animals comprising 11 species were processed, including 1016 primary captures (individuals with no identification tag or obvious sign of ear biopsy) and 586 recaptures (Table 1). Peromyscus species, several of which occur at our sampling sites, can be challenging to differentiate by morphology, and were treated as a single group. Site-specific totals for animals processed were 421, 497, 392, and 292 respectively, for Middle Garden Canyon (GC), SPH, HB and HBE (Table 2). Yellow-nosed cotton rats (Sigmodon ochrognathus) were the Sigmodon species identified at the montane GC site, whereas Arizona cotton rats (Sigmodon arizonae) were captured at the three trapping locations near the San Pedro River.

A total of 394 (24.6%) small mammals were infested with ticks at either first capture or recapture, including site-specific capture totals of 47, 91, 172, and 84 (GC, SPH, HB, HBE). Sixteen individuals were found simultaneously infested with at least one larva and nymph (14 S. arizonae, one Chaetodipus hispidus, one Dipodomys merriami). 22.5% (n = 229) of small mammals were infested with ticks at primary capture and 28.2% (n = 165) recaptured animals were infested. Sigmodon spp. accounted for 40.6% of primary captures and 53.9% of recaptures (S2). Ticks were identified on individuals from each of the rodent groups with the exception of two species that were seldomly encountered Perognathus flavus (n = 5) and Otospermophilus variegatus (n = 1). Stratified by site, the proportion of small mammal captures identified as Sigmodon spp., was highest at HB and HBE (61.5%, 58.9%), the sites where the highest numbers of immature ticks were collected (Table 2). In contrast, at GC where the fewest ticks were collected, the proportion of total captures represented by Sigmodon spp. was the lowest (24.7%).

Larvae and nymphs were identified on hosts at each of the four trapping sites and Sigmodon spp. were significantly more likely to be infested (273/728, 37.5%) relative to all other rodent groups (121/874, 13.8%, p < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test). Tick load (number of ticks removed per host) was non-normally distributed for all rodent groups for both larvae and nymphs (p < 0.0001, Shapiro-Wilk test) and differences in tick load among rodent groups were significant for both larvae (Kruskal-Wallis; H = 29.71, p = 0.001) and nymphs (H = 163.5, p < 0.0001). Larval load of S. arizonae was significantly higher than S. ochrognathus (Dunn’s multiple comparison test, p = 0.001) and differences in larval infestation of other species were either non-significant or inadequate for statistical comparison. Nymphal loads were not significantly different between Sigmodon species, but S. arizonae loads were significantly higher than Peromyscus spp., Chaetodipus intermedius, Neotoma albigula, and D. merriami (p = < 0.0001) and Reithrodontomys montanus (p = 0.005). Sigmodon ochrognathus loads were significantly higher than Peromyscus spp., C. intermedius, and D. merriami (p = < 0.0001) and N. albigula, R. montanus (p = < 0.005). The number of ticks collected from the four least common small mammal groups were too low for statistical comparison. Sigmodon arizonae had the highest mean tick loads for both larvae and nymphs (1.35, 1.05, Table 1). Most attached ticks were observed on ears, and occasionally, on the frontal and parietal regions of the head and nape. Few ticks were removed from the body and appendages, although in several instances, unattached nymphs were found on posterior regions of Sigmodon rats.

Wildfire destruction of the HB site in April 2023 interrupted site sampling for three months. Following modest regeneration of vegetation, trapping was resumed at the site in August through October, and 15 small mammals were captured or recaptured (11 D. merriami, three Peromyscus spp., one C. intermedius) (Table 5). Sigmodon arizonae were notably absent from this location where they had accounted for 63.9% of captures prior to the wildfire. A single larva was removed from each of two D. merriami captured at HB in October 2023, the final month of sampling.

Table 5.

Summary of rodents captured with Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato tick counts at Hereford Bridge before and after wildfire.

| Species | Total captured | primary capture | recapture | % captures | larvae | % total larvae | nymphs | % total nymphs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB pre-fire | 9/20/2022 - 4/1/2023 | |||||||

| Sigmodon arizonae | 241 | 148 | 93 | 63.9% | 341 | 87.2% | 553 | 91.0% |

| Peromyscus spp. | 88 | 61 | 27 | 23.3% | 45 | 11.5% | 48 | 7.9% |

| Chaetodipus intermedius | 12 | 9 | 3 | 3.2% | 4 | 1.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Chaetodipus hispidus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Reithrodontomys montanus | 18 | 17 | 1 | 4.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.5% |

| Neotoma albigula | 8 | 7 | 1 | 2.1% | 1 | 0.3% | 3 | 0.5% |

| Onychomys torridus | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.2% |

| Dipodomys merriami | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| total | 377 | 249 | 128 | 391 | 608 | |||

| Species | Total captured | primary capture | recapture | % captures | larvae | % total larvae | nymphs | % total nymphs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB post-fire | 8/20/2023 -10/27/2023 | |||||||

| Dipodomys merriami | 11 | 10 | 1 | 73.3% | 2 | 100% | 0 | 0 |

| Peromyscus spp. | 3 | 3 | 0 | 20.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chaetodipus intermedius | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| total | 15 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||

Monthly trapping was conducted between September 2022 and April 2023. The site was burned on April 3rd, 2023 and trapping was resumed in late August, September, and October of 2023 once grasses and forbs and begun re-establishing at the site.

Birds

Two-hundred sixty-three birds representing three orders (Galliformes, Piciformes, Passeriformes) and 41 species were captured and identified from the three SPRNCA sites (Table 3). Twenty-one (8.0%) individual birds (10 species) were infested with ticks, including Callipepla gambelii, Toxostoma crissale, Toxostoma curirostre, Thryomanes bewickii, Troglodytes aedon, Pipilo aberti, Spizella breweri, Zonotrichia leucophrys, Melospiza lincolnii, and Melospiza melodia (Table 3).

Several birds were observed infested with both A. maculatum s.l. and H. leporispalustris, including a Bewick’s wren captured in February that was infested with three A. maculatum nymphs and a H. leporispalustris larva. A song sparrow from which a single A. maculatum s.l. nymph was collected at initial capture, was again infested with an A. maculatum s.l. nymph and a H. leporispalustris larva when recaptured eight days later. The data reveal significant patterns in infestations among the various foraging behaviors and habitat preferences of captured avifauna. Infestations were more common in avifauna that spend > 50% of time foraging on the ground or in dense vegetation located on the ground, extending into the lower canopy. For example, Gambel’s Quail (C. gambelii 1/2; 50% infested with ticks), Lincoln’s Sparrow (M. lincolnii 4/7; 57%), Song Sparrow (M. melodia 6/23; 26%), Brewer’s Sparrow (S. breweri 1/2; 50%), Bewick’s Wren (T. bewickii 3/6; 50%), and House Wren (T. aedon 2/2; 100%) forage on the ground or near the lower understory in dense vegetation. Birds that primarily forage in mid to upper canopies, such as Yellow Warblers, Painted Buntings, Ruby-crowned Kinglets, and multiple vireos and flycatchers were not infested with A. maculatum s.l. Likewise, the Gila and Ladder-backed woodpeckers, which specialize in foraging on tree trunks and branches, did not yield ticks (Table 3).

Discussion

Regular sampling at Arizona locations where A. maculatum s.l. are well-established revealed that these ticks are opportunistic parasites of many species of small and large mammals and birds. Common hosts for immature stages include sigmodontine rats and to a lesser extent, other coexistent myomorphs (mice and rats). Ground foraging bird species were also parasitized by larvae and nymphs, while species classified as aerial, mid and upper canopy foragers were not associated with A. maculatum s.l. at our sites. Additionally, most birds found infested with A. maculatum s.l. are classified as year-round residents in southern Arizona23,24, indicating probable autochthonous acquisition of endemic ticks. Frequency and intensity of tick infestations were lower for avian hosts than small mammals, suggesting the greatest significance of avian hosts in this system may be the ability to function as long-distance transport vehicles capable of flying hundreds of miles within the short period that immature ticks are attached while feeding20. Two avian species found infested with A. maculatum s.l. are considered either neotropical migrants (M. lincolnii) or both resident and neotropical migrants (Z. leucophrys), indicating a potential avenue where interactions between groups of avifauna with distinct spatial niches could accelerate regional dispersion of ticks.

As key hosts for the reproductive adult stages, large mammals including deer and canines are likewise important sources of tick dispersal. At a sampling site completely denuded of vegetation by wildfire in the spring of 2023, few rodents and no ticks were observed present during summer months, yet two larvae were subsequently collected at this location in October 2023 when the vegetation was primarily new forbs amid sparse grass coverage. This suggests that A. maculatum s.l. adult females, which are unlikely to parasitize small mammals or passerine birds, were transported to the location while feeding on deer or another large transient host, effectively reintroducing ticks to a de-populated, early-stage successional habitat. This type of dissemination would be expected to be more localized and concentrated than avian introductions of ticks on account of the more limited short-term range of large vertebrates and the preference of reproductive stages of A. maculatum for these hosts, leading to a scenario where an infested deer could transport multiple females each capable of producing a clutch containing thousands of eggs. Interestingly, both post-fire larvae were collected from Merriam’s kangaroo rats (D. merriami), a comparatively rare species with low tick loads. Populations of kangaroo rats and other granivorous pocket mice have been shown to increase following summer wildfires in this region that result in concomitant rapid decline of Sigmodon rat populations25,26. A similar pattern was observed at our burned site where Sigmodon were no longer observed, replaced by kangaroo rats as the most common rodent captured, demonstrating the advantages of a generalist approach to parasitism, as well as the rapidity A. maculatum s.l. can become re-established in a favorable habitat.

Across all sampling locations, Sigmodon rats were significantly more likely than other small mammals to be infested with immature A. maculatum s.l. and likewise, carried the highest aggregate tick loads. This finding is unsurprising considering that the hispid cotton rat (S. hispidus) is recognized as a key host for A. maculatum s.s. in the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic regions of North America27–29. Similarly, in South America, two members of the A. maculatum complex, Amblyomma triste and to a lesser extent, Amblyomma tigrinum are associated with other sigmodontine rats30–33. Physiological attributes including body size may positively reinforce this relationship, especially for the larger nymphal stage, however the association is likely more representative of a shared affinity of the rats and ticks for grass-dominated microhabitats. In southern Arizona, Arizona cotton rats (S. arizonae) are primarily associated with grassy riparian corridors, and yellow-nosed cotton rats (S. ochrognathus) with semi-arid oak savannahs34,35. While many of the rodent species we encountered maintain diets consisting largely of seeds, arthropods, and cacti, cotton rats are nutritionally dependent primarily on graminoid vegetation36,37. In addition, they are known to fashion nests and refuges within bunches of grass, or alternately, weave large nests of grass within burrows abandoned by other rodents34 and signs of rat modification of sacaton tussocks were common at our SPRNCA sites. Big sacaton (Sporobolus wrightii) can reach heights of over eight feet and the long blades offer an ideal platform for A. maculatum adults questing for large animals. In addition to increased opportunities for encountering hosts, the dense bases of bunch grasses offer protected microhabitats for quiescent and questing immature stages, which are less physiologically resistant to desiccation than adults38–40. Although we did not evaluate the fauna and flora of sub-optimal tick habitat, a meta-analysis by Nava & Guglielmone41 concluded that environmental conditions including habitat may be more important than specific host associations for Neotropical hard ticks.

While A. maculatum s.l. and Gulf Coast ticks (A. maculatum s.s.) share similar host preferences14, the latter are known to have highly variable univoltine phenology specific to region. Seasonal activity patterns reported for adult stages of Gulf Coast ticks in Kansas and Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia differ by as much as four months, emerging as early as February with an April peak in Kansas and northern Oklahoma14,15,27. In Arizona, A. maculatum s.l. activity seems to be initiated by the onset of the North American monsoon, when up to 60% of the annual precipitation falls between July and September42,43. The onset of the seasonal monsoon is associated with a rise in relative humidity that likely triggers activity of dormant adults, which ascend vegetation to quest at heights for medium-to-large mammalian hosts, exposing them to potentially intense desiccative conditions44,45. Metabolic demands associated with more extreme environmental conditions may account for a shorter seasonal window of activity for adult A. maculatum s.l., which become scarce by early autumn, compared with adult Gulf Coast ticks, which are active for up to 5–6 months14,15,27.

We estimated peak larval activity to occur around 8–10 weeks after the adult peak, and our last record of this stage was in January, which may be the end limit of longevity for unfed larvae (161 days). Nymphs were regularly observed on small mammals from September through May (233 days). Outside of a period lasting from early May through mid-August, small mammal hosts with one or both immature stages attached were captured each month, indicating that immatures questing in protected microclimates near the soil and basal vegetation are less constrained by low ambient winter temperatures than by excessively hot and dry conditions such as those occurring during the pre-monsoon period in May and June. Interestingly, despite the consistent numbers of small mammals sampled each month, we observed a sequence of modest nymphal activity in September in both years sampled, followed by relative absence of this stage in October and November prior to the winter peak (Fig. 3), which may reflect larval activity spanning two discrete seasons. Developmental period in ticks is strongly influenced by environmental conditions, especially temperature, and at the onset of larval emergence in late August conditions at our sites presented elevated ambient humidity levels, long degree days, and maximal vegetation cover. At temperatures above 70 degrees, A. maculatum s.s. larvae feed and molt within 17 to 39 days38, which independently, suggests a much earlier peak in nymphs than the four-month interval we observed between peaks of the two stages in the field. However, the drop in average daily temperatures between mid-August and October may prolong the developmental period for all but the earliest of the larval cohort to successfully acquire a bloodmeal. Following the onset of nymphal activity, all three life stages were simultaneously active for nearly four weeks, potentially influencing co-feeding transmission of Rickettsia among ticks. Most nymphs were collected between January and April and applying an estimated of 17–71 days for nymph to adult molting period14, it is likely that newly emerged adults undergo quiescence or behavioral diapause for weeks or months until monsoon conditions arrive.

Among our sites, rodents captured at the SPRNCA locations had greater tick loads than at the comparatively rocky, higher elevation GC site situated at the base of the Huachuca Mountains where cotton rats were less abundant. Following a wet and relatively cool monsoon season the first year of our study, this period was considerably hotter and drier in the second year, with less than 30% of the previous year’s precipitation46. The effects were particularly evident at GC, including dry stream beds and a lack of new growth grasses. Of the relatively few larvae collected at GC, most (29/39) were found on a single S. ochrognathus in 2022, and in 2023 when cotton rats were scarce or absent from the pre-monsoon period through larval emergence, only 6 total larvae were collected at GC. In contrast, at the lower elevation riparian sites where the water table remains high even during periods of low precipitation47, there was ample new growth grass and S. arizonae were regularly captured each month. Like many tick species, A. maculatum s.l. is unevenly distributed across the landscape, existing in small pockets of ideal habitat interspersed within the desert ecosystem. The presence of engorged adult females on large animals between the Huachuca Mountains and the San Pedro River underscores the importance of tick translocation by wildlife movement between low riparian areas and the fragmented grassland at higher elevation sites bordered by desert valleys, which represent most locations where these ticks have been identified6,10,11. As most of the desert wetlands, known as ciénegas in the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico have been reduced or drained in the last 150 years, expansive grasslands supported by stable shallow ground water tables have disappeared as a consequence48. Climate trends including warmer temperatures and aridification, along with intensive changes in patterns of land usage can lead to local extinctions of organisms in lowland areas of sky island biomes; whereas nearby montane elevation gradients can function as isolated buffer zones within the larger desert landscape retaining fragments of microhabitat critical for survival of certain species49. Historically, big sacaton (S. wrightii) grasslands were widely dispersed along the San Pedro River, however much of this habitat vanished in the last century as the river channel became widened and deepened with a lower water table following a series of anthropogenic and hydrogeomorphic events50,51. As forest and grassland habitats have gradually recovered along portions of the San Pedro River corridor in recent decades43,52, montane grassland refugia may have acted as sources of reintroduction of A. maculatum s.l., and with the ticks, a corresponding increased risk of R. parkeri rickettsiosis to humans working and recreating in these areas.

Compared to other species of the A. maculatum complex, A. maculatum s.l. currently inhabits an environmental niche that is hotter and drier with greater variability in temperature range and seasonality of precipitation16. Allerdice et al.8 previously demonstrated reproductive incompatibility between hybrid Arizona A. maculatum s.l. and A. maculatum s.s. sourced from Georgia, suggesting that the two may be distinct species. Continued research on A. maculatum s.l. should further define its taxonomic relationship with Gulf Coast ticks, explore possible physiological and behavioral adaptations associated with survival of this tick in arid environments, and determine the relative roles of ticks and their hosts in enzootic maintenance of R. parkeri in this region.

Methods

Study areas

Monthly small mammal trapping sessions were conducted between August 2022 and October 2023 at four sites in Cochise County, Arizona, U.S. (Fig. 1). Hereford Bridge (HB) and San Pedro House (SPH), two sampling sites within the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area (SPRNCA), were selected based on the presence of adult A. maculatum s.l. previously reported by Allerdice et al.10. The SPRNCA encompasses 57,000 acres of desert riparian corridor that provides critical habitat for overwintering and migratory birds, along with a wide range of other wildlife53. These sites were sampled monthly, except August and October (HB & SPH), and December (SPH) of 2022. A third sampling site, the Middle Garden Canyon (GC) located on the U.S. Army installation Fort Huachuca was selected for trapping based on expected suitability of tick habitat, as well as previous documentation of A. maculatum s.l. adults in nearby locations11. GC was sampled in August and December 2022, followed by monthly sessions from March through October 2023. After the HB site was wholly denuded by wildfire following the April sampling session, a replacement site Hereford Bridge East (HBE) on the opposite side of the San Pedro River (northeast side of the bridge) was sampled monthly, from May through October 2023. Limited trapping (one night per month) was resumed at the original HB site from August through October 2023 once new growth vegetation emerged. Cumulatively, traps were set at one or more sites in each calendar month beginning with August 2022 and ending October 2023. Trapping sessions occurred in August and September of both years, and animals were captured on at least six separate dates in each calendar month.

Habitat varied among the four sites, but areas with the greatest concentration of grasses were preferentially selected for trap lines. The HB site consisted of riparian floodplain where the dominant vegetation was a mixture of Big sacaton (Sporobolus wrightii) and weedy forbs, along with whitethorn acacia (Acacia constricta), and velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina). At HBE, the habitat included Big sacaton grassland bordered by Freemont cottonwood (Populus fremontii), Gooding’s willow (Salix gooddingii) and velvet mesquite on the river side, and desert scrubland on the opposite side. At SPH, the trapping sites were just outside the riparian zone where the vegetation included Big sacaton, velvet mesquite, white thorn acacia and weedy forbs. The GC site was located on a shallow sloping, rocky hillside in and adjacent to Madrean oak woodland. The habitat was dry savannah with irregular patches of grama grass (Bouteloua) interspersed with Arizona white oak (Quercus arizonica), border pinyon, American century plant (Agave americana), tree cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata), mountain yucca (Yucca madrensis) and alligator juniper (Juniperus deppeana).

Small mammal capture

Sherman live traps (3 × 3.5 × 9”; Tallahassee, FL, USA) were set for up to three consecutive nights, with the total number deployed (35–150) varying based on our prior capture success rate at a site. Traps were spaced approximately 10 m apart and baited with either a peanut butter and oat mixture, or commercial bird seed mix. Trap lines were checked at sunrise and closed during the day during elevated temperatures. Cotton batting or wool were placed in traps during cold months for insulation. Additional trapping was performed during the day in winter months when diurnally active Sigmodon rats were preferentially targeted. Tomahawk live traps were occasionally deployed at SPRNCA but mesomammals were rarely observed and none were captured. Sites within the SPRNCA were typically sampled for one or two consecutive nights, 2–3 times per month to minimize recapture of animals on consecutive days, with some weather-related variability. Small mammals were anesthetized with isoflurane, using a Sigma Delta Vaporizer (Penlon, United Kingdom) and Pro 5 portable oxygen concentrator (Pro O2, Alabama, USA) at settings of 1–4% isoflurane and 90% O2 at a flow rate of 3 L/min. Morphological measurements were recorded, and blood and sera collected via retroorbital bleed using EDTA and SST Microtainer capillary blood collection tubes (BD, New Jersey, USA). Ear tissue biopsies were preserved in RNAlater Solution (Invitrogen-ThermoFisher, Massachusetts, USA). Tissues were placed on cold packs in the field setting, and later stored at 4° C. until DNA extraction. Animals were examined for ectoparasites for up to 10 min while under anesthesia; arthropod specimens were collected using fine-tipped forceps and/or paintbrushes and preserved in 80% ethanol. All samples were stored at 4° C until they could be processed. Ear tags with identification numbers were attached to all rodents processed except those weighing under 10 g and/or species with prohibitively small ears (C. intermedius, R. montanus, P. flavus and some Peromyscus spp.). Because recapture status was primarily useful for determining ectoparasite load and Rickettsia infection status rather than estimating rodent abundance, animals suspected to have lost previous ear tags were designated as new captures and re-tagged. Once recovered, rodents were subsequently released at the original site of capture.

Bird capture

Avian mist nets (30 mm x 12 mm and 38 mm x 12 mm) were used to capture birds at SPH, HB, and HBE between December 2022 and October of 2023. Netting sites were chosen proximal to, but not overlapping with small mammal trap lines, and situated in grassland-riparian interface or underneath the deciduous canopy of the San Pedro River. Up to six nets were deployed and checked at regular time intervals according to weather conditions. Morphological measurements of bird were recorded, individuals were identified to species following methods of Pyle & Howell54, and Sibley55 and banded with USGS identification tags, followed by a full-body search for ectoparasites prior to release. Ticks and other ectoparasites were removed using fine tipped forceps and preserved in 80% ethanol until formal identification.

Hunter-collected ticks

In Autumn of 2023, during the firearms and bow hunting seasons at Ft. Huachuca, hunters were provided forceps and tubes of ethanol and encouraged to collect any ticks observed on carcasses, recording the location harvested. On-base processing sites were checked for specimen tubes weekly.

Off host tick collection

Weekly sampling for adult ticks was performed at SPRNCA sites during the period of adult activity. A combination of tick flags (52.5 cm x 74 cm white flannel cloth attached to a wooden dowel) and insect sweep nets were dragged or swept over or through vegetation, preferentially targeting bunches of Big sacaton along trails, in areas proximal to but not overlapping with small mammal trap lines. Sampling was performed during daylight hours, and time of sampling is not addressed here since it did not have a discernable influence on the quantity of ticks collected. Ticks were preserved in 80% ethanol.

Tick identification and imaging

Adult A. maculatum s.l. specimens were identified using morphological descriptions listed by Lado et al.7. Immature ticks previously identified as Amblyomma were visually confirmed by an entomologist with experience distinguishing members of the A. maculatum complex as described in Estrada-Pena et al.1. Although there is no published key for speciating immature stages of the A. maculatum complex, all adult stage ticks present at our sites were morphologically confirmed as A. maculatum s.l. Haemaphysalis leporispalustris were morphologically identified according to keys described in Kohls56 and Egizi et al.57. A Nikon SMZ25 stereo microscope and NIS-Elements Imaging software (Nikon Americas Inc., Melville, NY, USA) were used to create tick images.

Statistical analysis and phenology calendar

Prism 10 (Graphpad, California, USA) was used to perform tests of statistical significance. Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate differences in infestation, species specific tick loads were tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk, and Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were used to evaluate interspecies differences in tick load. LOESS-based phenology curves for A. maculatum s.l. life stages were modeled in R (version 4.2.3) using data collected in this study which included adults removed from vegetation and hosts, and immatures removed from small mammals and birds. On dates sampled in both 2022 and 2023, the mean tick count for the two days was used. Daily data points (proportions) were calculated by dividing daily tick counts for each calendar day sampling was performed by the total of that stage collected on all dates.

Approval for animal handling

All animal handling procedures were reviewed and approved by the Texas A&M AgriLife Research Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee AUP #2021–027 A, Arizona Game and Fish Department Scientific Activity Permits SP909232 and SP798901, and USGS Federal Bird Banding Permit #24367. All procedures were conducted in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use guidelines and all authors complied with Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the US Department of Defense Tick and Tick-borne Disease Research Program Grant W81XWH-21-2-0029 and the National Institute for Food and Agriculture Hatch Project #1019784 awarded to TLJ. The authors thank the Environmental Resources Division at Fort Huachuca for on-site coordination and hunter harvest tick collection, the Arizona Bureau of Land Management, and Chris Lefrak for assistance with software programming.

Author contributions

G.E.L. - field investigation, identifications, data analysis, and writing original draft. T.J.L. - field investigation, identification, data analysis, and review and editing. M.E.J.A. - identifications, resources, review and editing. C.D.P. - conceived the study, scientific guidance, and review and editing. B.A.G. - guidance and training on avian sampling, and review and editing. P.A.L. field investigation, and review and editing. P.D.T. - scientific guidance, and review and editing. T.L.J. conceived the study, field investigation, data analyses, and review and editing.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Geoffrey E. Lynn, Email: geoff.lynn@ag.tamu.edu

Tammi L. Johnson, Email: Tammi.Johnson@ag.tamu.edu

References

- 1.Estrada-Peña, A., Venzal, J. M., Mangold, A. J., Cafrune, M. M. & Guglielmone, A. A. The Amblyomma maculatum Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae: Amblyomminae) tick group: Diagnostic characters, description of the larva of A. Parvitarsum Neumann, 1901, 16S rDNA sequences, distribution and hosts. Syst. Parasitol.60(2), 99–112. 10.1007/s11230-004-1382-9 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paddock, C. D. & Goddard, J. The Evolving Medical and Veterinary Importance of the Gulf Coast tick (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol.52(2), 230–252. 10.1093/jme/tju022 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nieri-Bastos, F. A., Marcili, A., De Sousa, R., Paddock, C. D. & Labruna, M. B. Phylogenetic evidence for the existence of multiple strains of Rickettsia parkeri in the New World. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.84(8), e02872–e02817. 10.1128/AEM.02872-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allerdice, M. E. J., Paddock, C. D., Hecht, J. A. & Karpathy, G. J. Phylogenetic differentiation of Rickettsia parkeri reveals broad dispersal and distinct clustering within north American strains. Microbiol. Spectr.9(2), e0141721. 10.1128/Spectrum.01417-21 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrick, K. L. et al. Rickettsia parkeri Rickettsiosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis.22(5), 780–785. 10.3201/eid2205.151824 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaglom, H. D. et al. Expanding recognition of Rickettsia parkeri Rickettsiosis in Southern Arizona, 2016–2017. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. (Larchmont N Y)20(2), 82–87. 10.1089/vbz.2019.2491 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lado, P. et al. The Amblyomma maculatum Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae) group of ticks: Phenotypic plasticity or incipient speciation? Parasites Vectors11(1), 610. 10.1186/s13071-018-3186-9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allerdice, M. E. J. et al. Reproductive incompatibility between Amblyomma maculatum (Acari: Ixodidae) group ticks from two disjunct geographical regions within the USA. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 82(4), 543–557. 10.1007/s10493-020-00557-4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Groschupf, K. & Mertins, J. W. Ticks and novel chigger mite species on passerine birds in southeastern Arizona. Arizona Birds – Journal of Field Ornithologists 1–12. (2022). (2022).

- 10.Allerdice, M. E. J. et al. Rickettsia parkeri (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) detected in ticks of the Amblyomma maculatum (Acari: Ixodidae) Group collected from multiple locations in southern Arizona. J. Med. Entomol.54(6), 1743–1749. 10.1093/jme/tjx138 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecht, J. et al. Distribution and occurrence of Amblyomma maculatum sensu lato (Acari: Ixodidae) and Rickettsia parkeri (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae), Arizona and New Mexico, 2017–2019. J. Med. Entomol.57(6), 2030–2034. 10.1093/jme/tjaa130 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delgado-de la Mora, J. et al. Rickettsia parkeri and Candidatus Rickettsia andeanae in ticks of the Amblyomma maculatum Group, Mexico. Emerg. Infect. Dis.25(4), 836–838. 10.3201/eid2504.181507 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paddock, C. D. et al. Rickettsia parkeri (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) in the Sky Islands of West Texas. J. Med. Entomol.57(5), 1582–1587. 10.1093/jme/tjaa059 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teel, P. D., Ketchum, H. R., Mock, D. E., Wright, R. E. & Strey, O. F. The Gulf Coast tick: A review of the life history, ecology, distribution, and emergence as an arthropod of medical and veterinary importance. J. Med. Entomol.47(5), 707–722. 10.1603/me10029 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadolny, R. M. & Gaff, H. D. Natural history of Amblyomma maculatum in Virginia. Ticks tick-borne Dis.9(2), 188–195. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.09.003 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuervo, P. F., Artigas, P., Lorenzo-Morales, J., Bargues, M. D. & Mas-Coma, S. Ecological niche modelling approaches: Challenges and applications in vector-borne diseases. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis.8(4), 187. 10.3390/tropicalmed8040187 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehringer, P. J. Jr. & Haynes, C. V. The pollen evidence for the environment of early man and extinct mammals at the Lehner mammoth site, southeastern Arizona. Am. Antiq.31(1) (1965).

- 18.Holmgren, C. A., Norris, J. & Betancourt, J. L. Inferences about winter temperatures and summer rains from the late quaternary record of C4 perennial grasses and C3 desert shrubs in the northern Chihuahuan Desert. J. Quat. Sci.22(2), 141–161 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mertins, J. W., Moorhouse, A. S., Alfred, J. T. & Hutcheson, H. J. Amblyomma triste (Acari: Ixodidae)Jnorth North American collection records, including the first from the United States. J. Med. Entomol.47, 536–542 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee, N. et al. Importation of exotic ticks and tick-borne spotted fever group rickettsiae into the United States by migrating songbirds. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis.5(2), 127–134. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.09.009 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teel, P. D., Hopkins, S. W., Donahue, W. A. & Strey, O. F. Population dynamics of immature Amblyomma maculatum (Acari: Ixodidae) and other ectoparasites on meadowlarks and northern bobwhite quail resident to the coastal prairie of Texas. J. Med. Entomol.35(4), 483–488. 10.1093/jmedent/35.4.483 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portugal, I. I. I. & Goddard, J. S. Collections of immature Amblyomma maculatum Koch (Acari: Ixodidae) from Mississippi, US. Syst. Appl. Acarol.20(10), 20–24 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy, E. D. & White, D. W. In Birds of the World Version 1.0. (eds Poole, A. F.) (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2020). 10.2173/bow.bewwre.01

- 24.Gill, F. B. & Prum, R. O. Ornithology, Fourth Edition (W.H. Freeman Press, 2019).

- 25.Bock, C. E. & Bock, J. H. Response of birds, small mammals, and vegetation to burning Sacaton grasslands in southeastern Arizona. J. Range Manag., 31(41) (1978).

- 26.Litt, A. R. Effects of experimental fire and nonnative grass invasion on small mammals and insects. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson. (2007).

- 27.Clark, K. L., Oliver, J. H. Jr, McKechnie, D. B. & Williams, D. C. Distribution, abundance, and seasonal activities of ticks collected from rodents and vegetation in South Carolina. J. Vector Ecol.23(1), 89–105 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cumbie, A. N. et al. Survey of Rickettsia parkeri and Amblyomma maculatum associated with small mammals in southeastern Virginia. Ticks tick-borne Dis.11(6), 101550. 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101550 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, C. R., Ponnusamy, L., Richards, A. L. & Apperson, C. S. Analyses of bloodmeal hosts and prevalence of Rickettsia parkeri in the Gulf Coast tick Amblyomma maculatum (Acari: Ixodidae) from a reconstructed Piedmont prairie ecosystem, North Carolina. J. Med. Entomol.59(4), 1382–1393. 10.1093/jme/tjac033 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nava, S., Mangold, A. J. & Guglielmone, A. A. The natural hosts of larvae and nymphs of Amblyomma tigrinum Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae). Vet. Parasitol.140(1–2), 124–132. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.009 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Venzal, J. M. et al. Amblyomma triste Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae): hosts and seasonality of the vector of Rickettsia parkeri in Uruguay. Vet. Parasitol.155(1–2), 104–109. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.017 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guglielmone, A. A. & Nava, S. Rodents of the subfamily Sigmodontinae (Myomorpha: Cricetidae) as hosts for South American hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) with hypotheses on life history. Zootaxa2904, 45–65 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nava, S. et al. Seasonal dynamics and hosts of Amblyomma triste (Acari: Ixodidae) in Argentina. Vet. Parasitol.181(2–4), 301–308. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.03.054 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmeister, D. F. The yellow-nosed cotton rat, Sigmodon ochrognathus, in Arizona. Am. Midl. Nat.70(2), 429–441 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gwinn, R. N., Palmer, G. H. & Koprowski, J. L. Sigmodon arizonae (Rodentia: Cricetidae). Mammalian Species. 43(883), 149–154 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker, R. H. Nutritional strategies of myomorph rodents in north American grasslands. J. Mammal.52(4), 800–805 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Randolph, J. C., Cameron, G. N. & Wrazen, J. A. Choice of a Generalist Grassland Herbivore, Sigmodon hispidus. J. Mammology. 72(2), 300–313 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hixon, H. Field biology and environmental relationships of the Gulf Coast tick in southern Georgia. J. Econ. Entomol.33, 179–189 (1940). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Needham, G. R. & Teel, P. D. Off-host physiological ecology of ixodid ticks. Ann. Rev. Entomol.36, 659–681. 10.1146/annurev.en.36.010191.003303 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portugal, J. S. & Goddard, J. Field observations of questing and dispersal by colonized nymphal Amblyomma maculatum Koch (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Parasitol.102(4), 481–483. 10.1645/15-909 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nava, S. & Guglielmone, A. A. A meta-analysis of host specificity in Neotropical hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). Bull. Entomol. Res.103(2), 216–224. 10.1017/S0007485312000557 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams, D. K. & Comrie, A. C. The north American Monsoon. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc.78(10) (1997).

- 43.Stromberg, J. C., Rychener, T. J. & Dixon, M. D. Return of fire to a free-flowing desert river: effects on vegetation. Restor. Ecol.17(3), 327–338 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goddard, J., Varela-Stokes, A. & Schneider, J. C. Observations on questing activity of adult Gulf Coast ticks, Amblyomma maculatum Koch (Acari: Ixodidae), in Mississippi, U.S.A. Syst. Appl. Acarol.16, 195–200 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Portugal, I. I. I., Wills, J. S. & Goddard, R. Laboratory studies of questing behavior in colonized nymphal Amblyomma maculatum ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Med. Entomol.57(5), 1480–1487. 10.1093/jme/tjaa077 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Total precipitation by year. Monsoon Season Station Climate Summaries: Sierra Vista, Climate Science Applications Program University of Arizona Cooperative Extension. https://cales.arizona.edu/climate/misc/stations/monsoon/SIERRA%20VISTA/stationHistory.html

- 47.Webb, R. H. & Leake, S. A. Ground-water surface-water interactions and long-term change in riverine riparian vegetation in the southwestern United States. J. Hydrol.320, 302–323 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendrickson, D. A. & Minckley, T. A. Cienegas vanishing climax communities of the American Southwest. Desert Plants6(3), 131–175 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiens, J. J. et al. Climate change, extinction, and Sky Island biogeography in a montane lizard. Mol. Ecol.28, 2610–2624 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hereford, R. Entrenchment and Widening of the Upper San Pedro River, Arizona 282 (Geological Society of America Special Paper, 1993).

- 51.Sayer, N. F. A history of land use and natural resources in the middle San Pedro River Valley, Arizona. J. Southwest.53(1), 87–137 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stromberg, J. C., Tluczek, M. G. F., Hazelton, A. F. & Hoori, A. A century of forest expansion following extreme disturbance: Spatio-temporal change in Populus/Salix/Tamarix forests along the Upper San Pedro River, Arizona, USA. For. Ecol. Manag.259, 1181–1189 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bureau of Land Management. San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. www.blm.gov/national-conservation-lands/arizona/san-pedro accessed 5/20/2024.

- 54.Pyle, P. & Howell, S. N. G. Identification Guide to North American Birds (Slate Creek, 1997).

- 55.Sibley, D. Sibley Birds West: Field Guide to Birds of western North America, Second edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016).

- 56.Kohls, G. M. Records and new synonymy of new world Haemaphysalis ticks, with descriptions of the nymph and larva of H. Juxtakochi Cooley. J. Parasitol.46, 355–361 (1960). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Egizi, A. M. et al. A pictorial key to differentiate the recently detected exotic Haemaphysalis longicornis Neumann, 1901 (Acari, Ixodidae) from native congeners in North America. ZooKeys818, 117–128 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.