Abstract

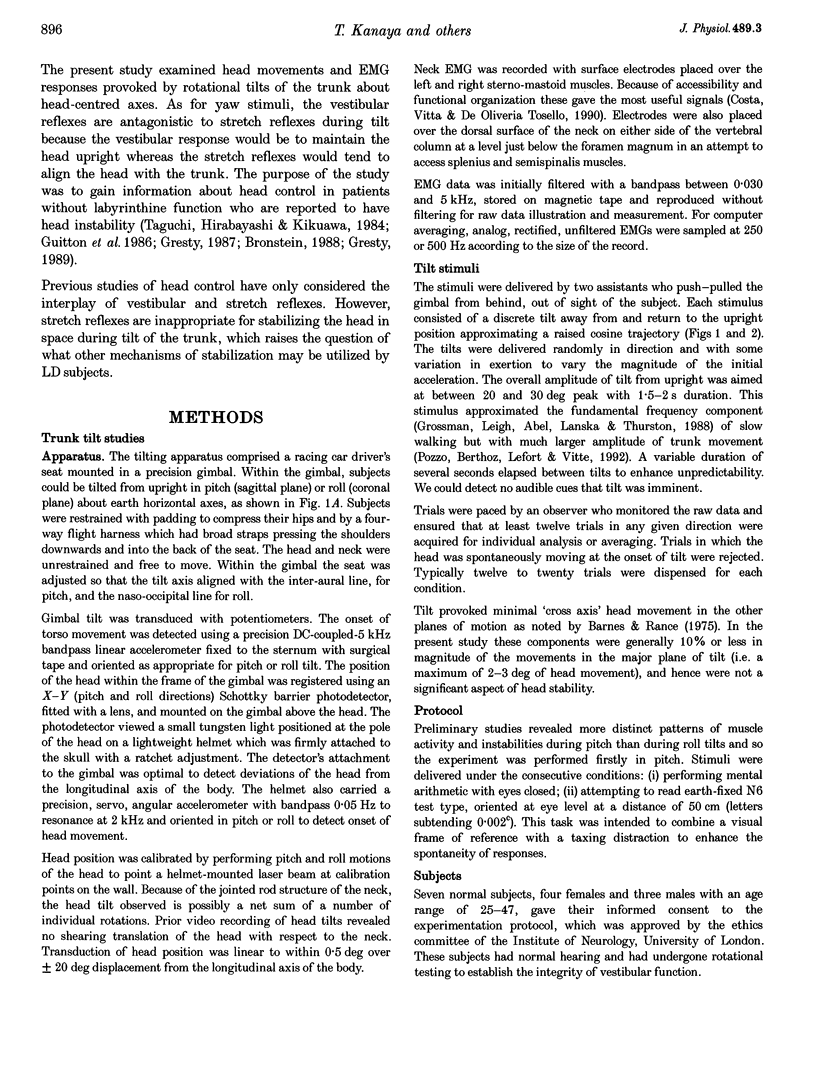

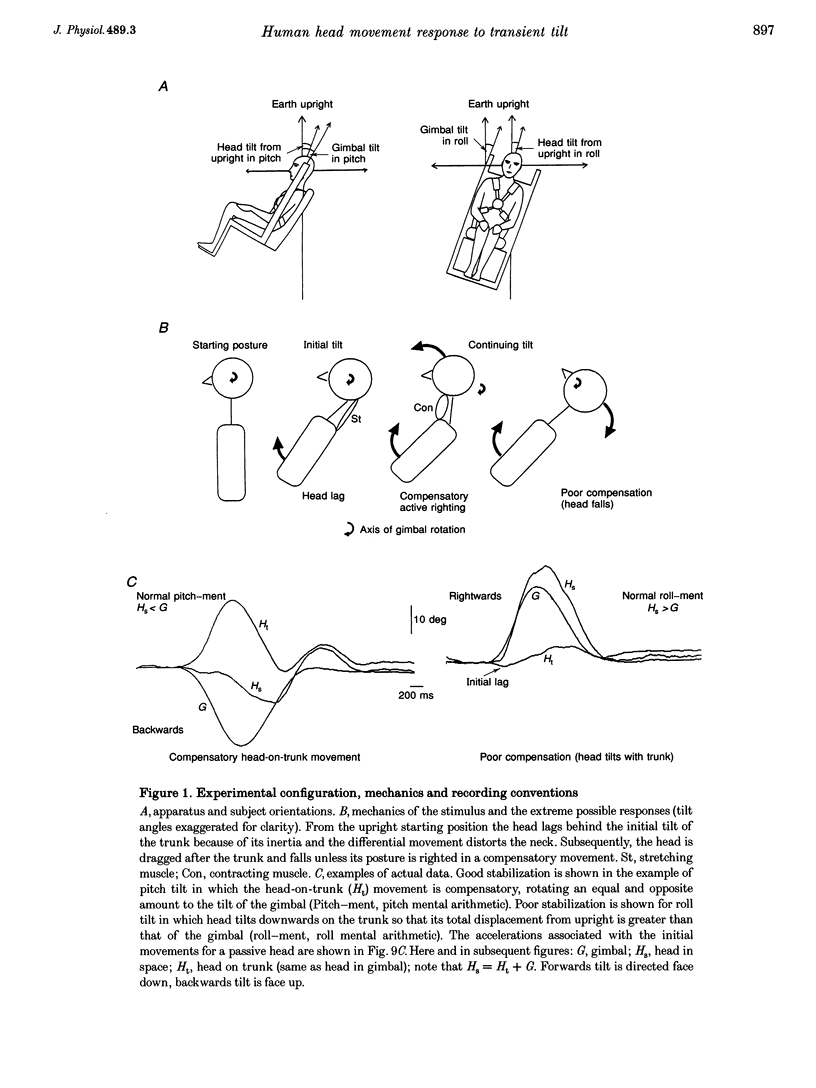

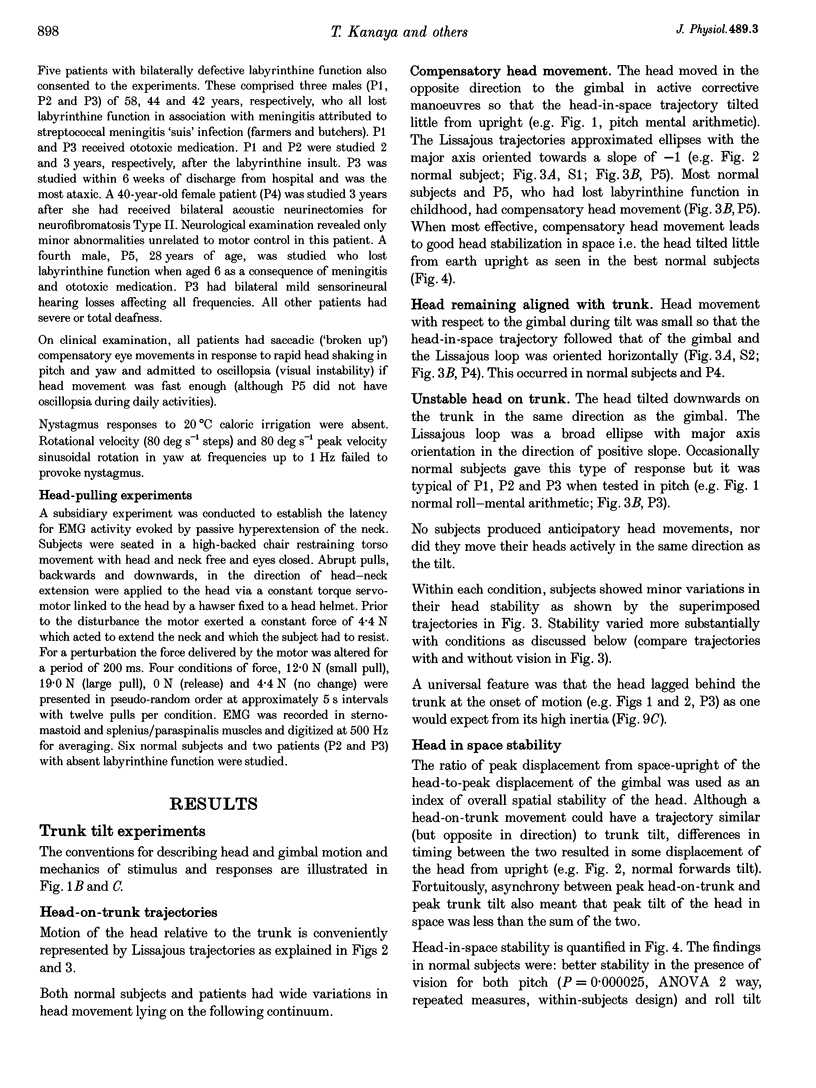

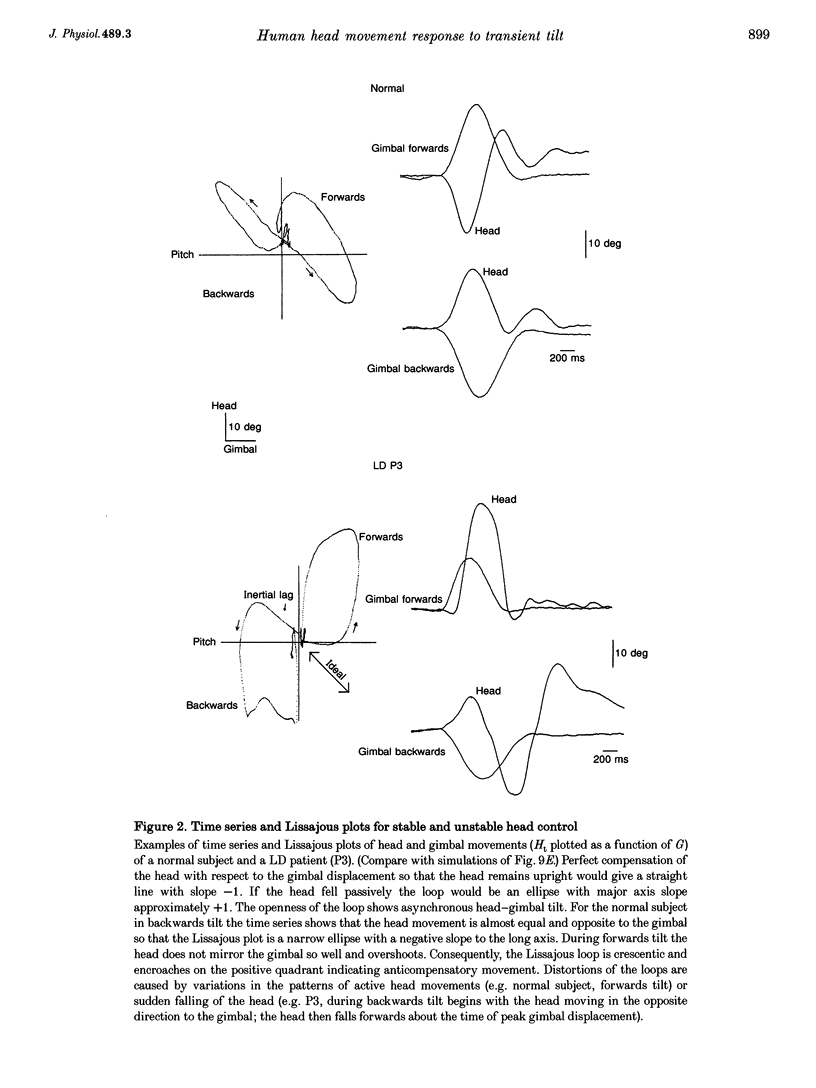

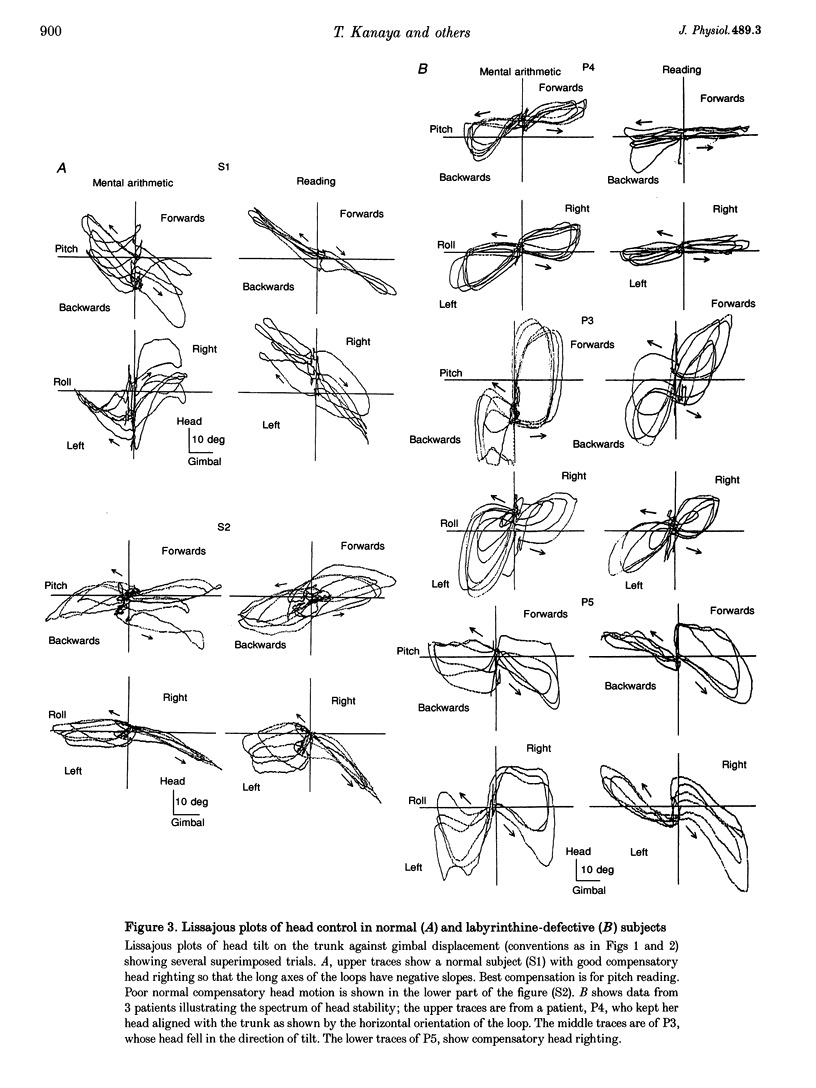

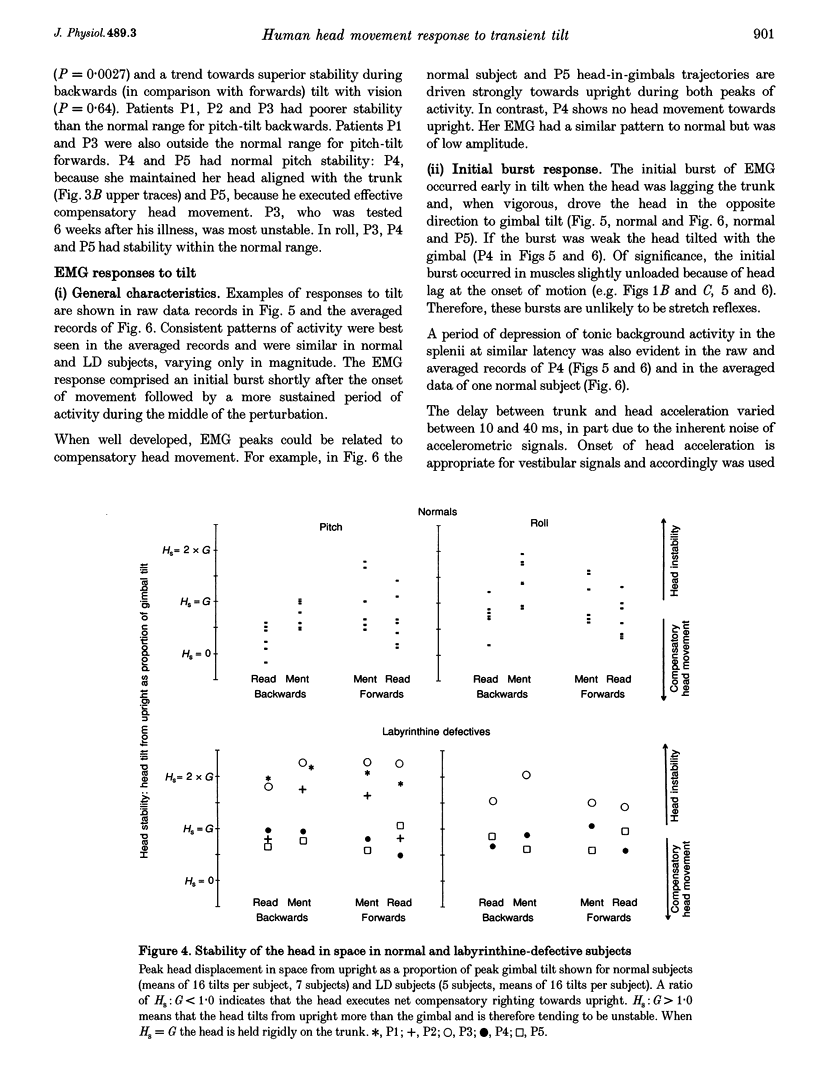

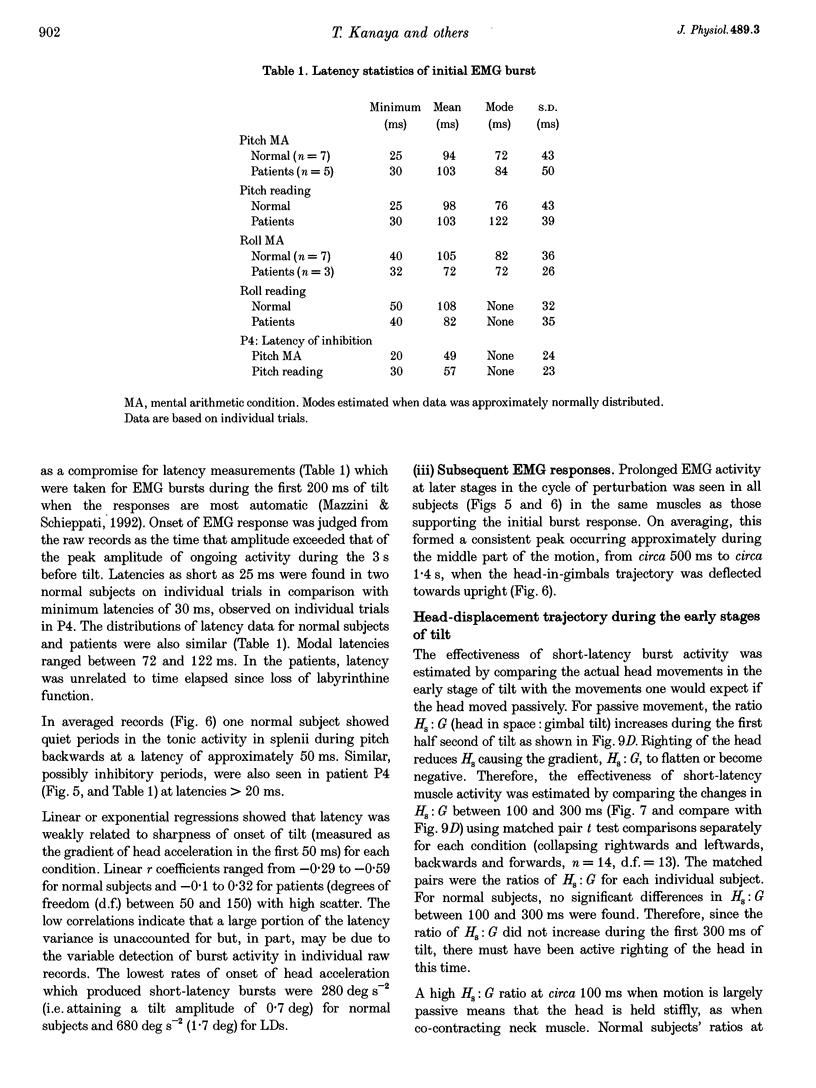

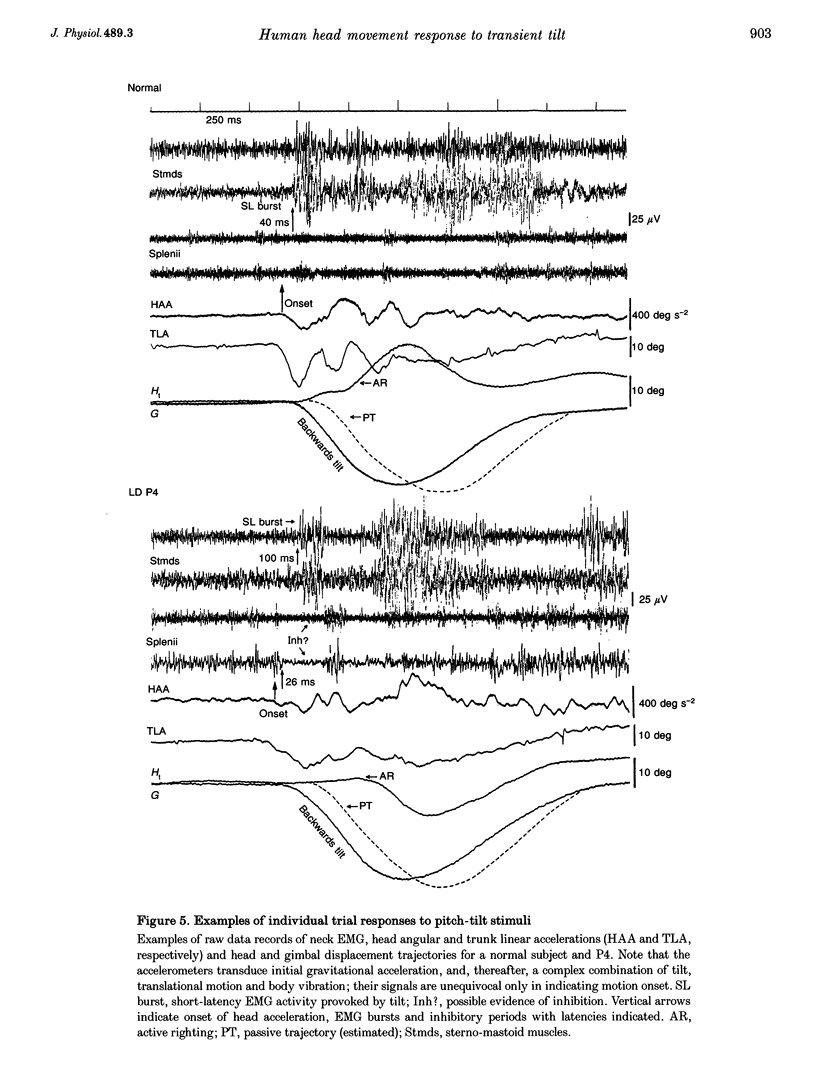

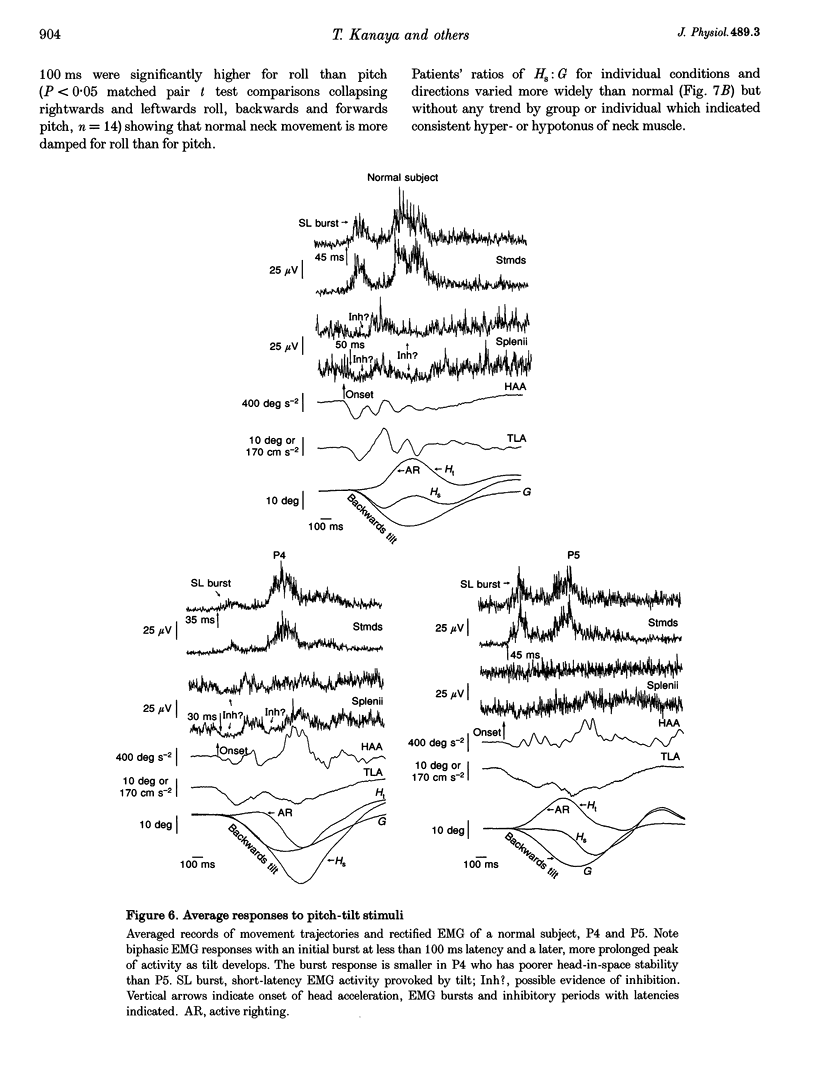

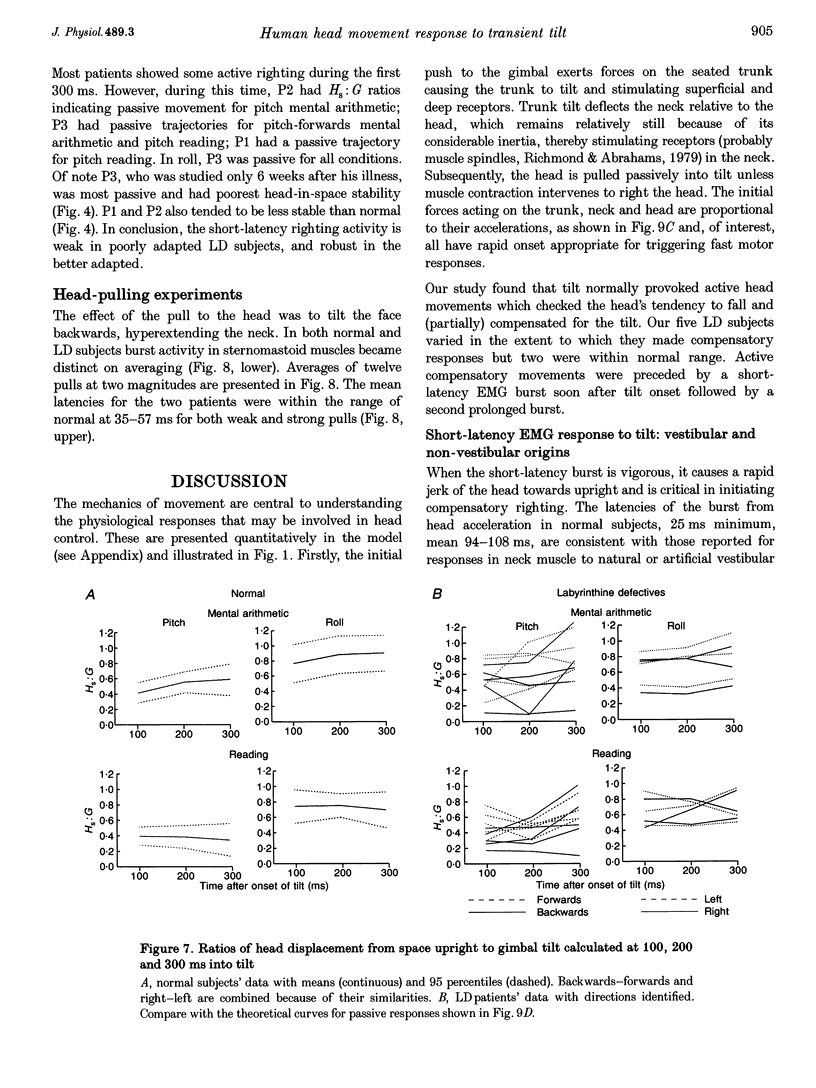

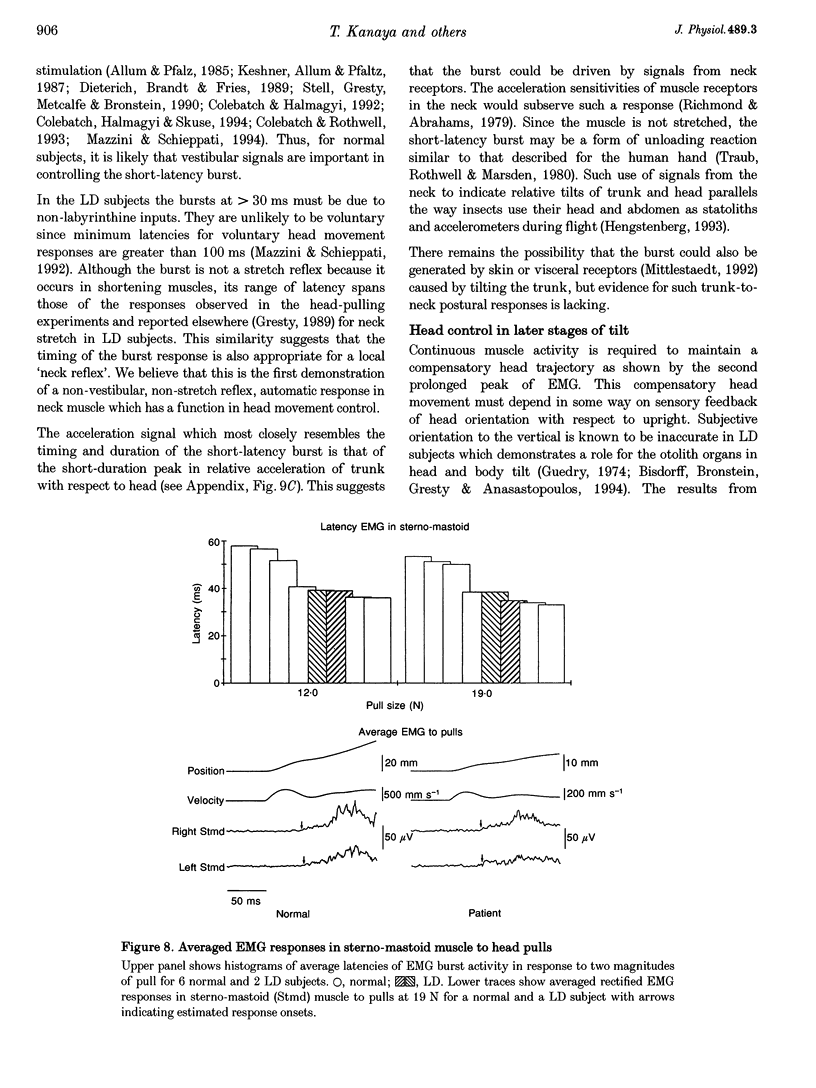

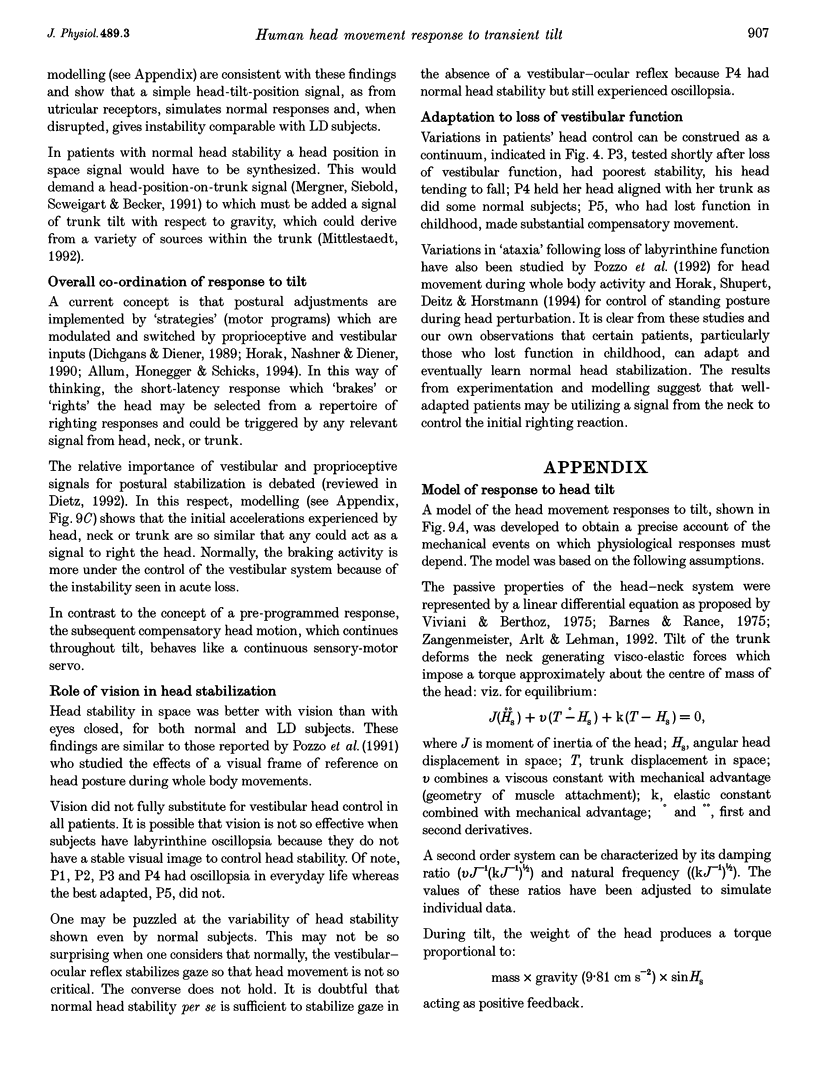

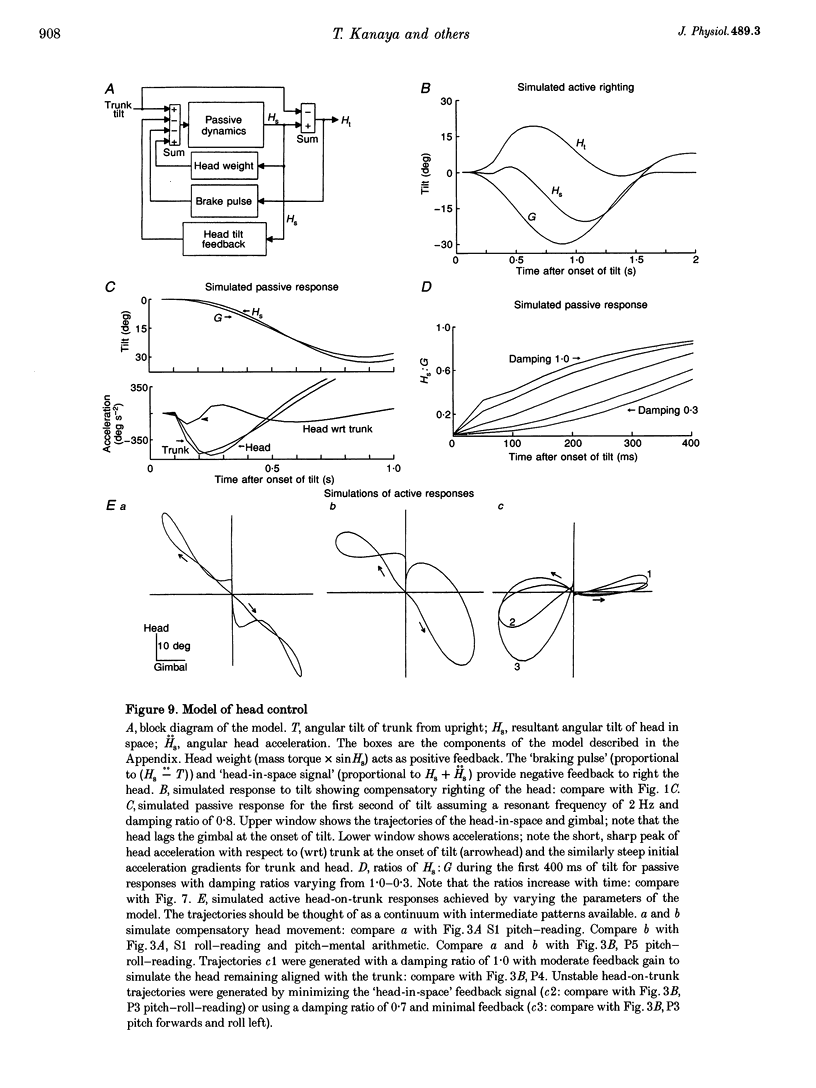

1. Head movement responses to discrete, unpredictable tilts of the trunk from earth upright were studied in normal and labyrinthine-defective (LD) subjects. Tilts of the seated, restrained trunk, were delivered in pitch and roll about head-centred axes and approximated raised cosine displacements with peak amplitudes of 20-30 deg and durations of 1.5-2 s. Subjects performed mental arithmetic with eyes closed or read earth-fixed text. 2. At the onset of tilt the head momentarily lagged behind the trunk because of inertia. Subsequently, head control varied widely with three broad types: (i) head relatively fixed to the trunk (in normal subjects and some patients); (ii) head unstable, falling in the direction of gimbal tilt (typical of acute patients for pitch motion); (iii) compensatory head movement in the opposite direction to gimbal tilt (observed consistently in normal subjects and in well-adapted patients). 3. EMG was well developed in subjects with compensatory head movement and consisted of an initial burst of activity at minimum latencies of 25-50 ms (means 72-108 ms), followed by a prolonged peak; both occurring in the 'side up' neck muscles, appropriate for righting the head. These muscles are shortened during the initial head lag so the responses cannot be stretch reflexes. In normal subjects their origin is predominantly labyrinthine but in patients they may be an 'unloading response' of the neck. 4. Head stability in space was superior with the visual task for all subjects but vision only partially compensated for labyrinthine signals in unstable patients. 5. Modelling the responses to tilt suggests that, in LD subjects, the short-latency burst could be driven by signals from the neck of the relative acceleration between head and trunk tilt. The longer latency EMG could be driven by a signal of head tilt in space. Normally, this signal is probably otolithic. In patients it could be synthesized from summing proprioceptive signals of position of head on trunk with trunk tilt.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allum J. H., Honegger F., Schicks H. The influence of a bilateral peripheral vestibular deficit on postural synergies. J Vestib Res. 1994 Spring;4(1):49–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allum J. H., Pfaltz C. R. Visual and vestibular contributions to pitch sway stabilization in the ankle muscles of normals and patients with bilateral peripheral vestibular deficits. Exp Brain Res. 1985;58(1):82–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00238956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. R., Rance B. H. Head movement induced by angular oscillation of the body in the pitch and roll axes. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1975 Aug;46(8):987–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borel L., Lacour M. Functional coupling of the stabilizing eye and head reflexes during horizontal and vertical linear motion in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1992;91(2):191–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00231654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein A. M. Evidence for a vestibular input contributing to dynamic head stabilization in man. Acta Otolaryngol. 1988 Jan-Feb;105(1-2):1–6. doi: 10.3109/00016488809119438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch J. G., Halmagyi G. M., Skuse N. F. Myogenic potentials generated by a click-evoked vestibulocollic reflex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994 Feb;57(2):190–197. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch J. G., Halmagyi G. M. Vestibular evoked potentials in human neck muscles before and after unilateral vestibular deafferentation. Neurology. 1992 Aug;42(8):1635–1636. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.8.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa D., Vitti M., De Oliveira Tosello D. Electromyographic study of the sternocleidomastoid muscle in head movements. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1990 Nov;30(7):429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichgans J., Diener H. C. The contribution of vestibulo-spinal mechanisms to the maintenance of human upright posture. Acta Otolaryngol. 1989 May-Jun;107(5-6):338–345. doi: 10.3109/00016488909127518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich M., Brandt T., Fries W. Otolith function in man. Results from a case of otolith Tullio phenomenon. Brain. 1989 Oct;112(Pt 5):1377–1392. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.5.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V. Human neuronal control of automatic functional movements: interaction between central programs and afferent input. Physiol Rev. 1992 Jan;72(1):33–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresty M. Stability of the head in pitch (neck flexion-extension): studies in normal subjects and patients with axial rigidity. Mov Disord. 1989;4(3):233–248. doi: 10.1002/mds.870040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresty M. Stability of the head: studies in normal subjects and in patients with labyrinthine disease, head tremor, and dystonia. Mov Disord. 1987;2(3):165–185. doi: 10.1002/mds.870020304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman G. E., Leigh R. J., Abel L. A., Lanska D. J., Thurston S. E. Frequency and velocity of rotational head perturbations during locomotion. Exp Brain Res. 1988;70(3):470–476. doi: 10.1007/BF00247595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton D., Kearney R. E., Wereley N., Peterson B. W. Visual, vestibular and voluntary contributions to human head stabilization. Exp Brain Res. 1986;64(1):59–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00238201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengstenberg R. Multisensory control in insect oculomotor systems. Rev Oculomot Res. 1993;5:285–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak F. B., Nashner L. M., Diener H. C. Postural strategies associated with somatosensory and vestibular loss. Exp Brain Res. 1990;82(1):167–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00230848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak F. B., Shupert C. L., Dietz V., Horstmann G. Vestibular and somatosensory contributions to responses to head and body displacements in stance. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100(1):93–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00227282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshner E. A., Allum J. H., Pfaltz C. R. Postural coactivation and adaptation in the sway stabilizing responses of normals and patients with bilateral vestibular deficit. Exp Brain Res. 1987;69(1):77–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00247031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini L., Schieppati M. Activation of the neck muscles from the ipsi- or contralateral hemisphere during voluntary head movements in humans. A reaction-time study. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992 Jun;85(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(92)90131-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner T., Siebold C., Schweigart G., Becker W. Human perception of horizontal trunk and head rotation in space during vestibular and neck stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 1991;85(2):389–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00229416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelstaedt H. Somatic versus vestibular gravity reception in man. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992 May 22;656:124–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B. W., Goldberg J., Bilotto G., Fuller J. H. Cervicocollic reflex: its dynamic properties and interaction with vestibular reflexes. J Neurophysiol. 1985 Jul;54(1):90–109. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzo T., Berthoz A., Lefort L., Vitte E. Head stabilization during various locomotor tasks in humans. II. Patients with bilateral peripheral vestibular deficits. Exp Brain Res. 1991;85(1):208–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00230002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond F. J., Abrahams V. C. What are the proprioceptors of the neck? Prog Brain Res. 1979;50:245–254. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60825-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi K., Hirabayashi C., Kikukawa M. Clinical significance of head movement while stepping. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1984;406:125–128. doi: 10.3109/00016488309123018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub M. M., Rothwell J. C., Marsden C. D. A grab reflex in the human hand. Brain. 1980 Dec;103(4):869–884. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.4.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani P., Berthoz A. Dynamics of the head-neck system in response to small perturbations: analysis and modeling in the frequency domain. Biol Cybern. 1975 Aug 1;19(1):19–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00319778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangemeister W. H., Arlt A. C., Lehman S. Sensitivity coefficients, trajectories and graphs of a human head-movement model. J Biomed Eng. 1992 Nov;14(6):451–458. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(92)90096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]