Abstract

Background

Thyroid cancer is ranked as the most common malignancy within the endocrine system and the seventh most prevalent cancer in women globally. Thyroid malignancies require evaluating biomarkers capable of distinguishing between them for accurate diagnosis. We examined both mRNA and protein levels of TSPAN1 in plasma and tissue samples from individuals with thyroid nodules to aid this endeavour.

Methods

In this case-control study, TSPAN1 was assessed at both protein and mRNA levels in 90 subjects, including papillary thyroid cancer (PTC; N = 60), benign (N = 30), and healthy subjects (N = 26) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and SYBR-Green Real-Time PCR, respectively.

Results

TSPAN1 plasma levels were decreased in PTC and benign compared to healthy subjects (P = 0.002). TSPAN1 mRNA levels were also decremented in the tumoral compared to the paired normal tissues (P = 0.012); this drop was also observed in PTC patients compared to benign patients (P = 0.001). Further, TSPAN1 had an appropriate diagnostic value for detecting PTC patients from healthy plasma samples with a sensitivity of 76.7% and specificity of 65.4% at the cutoff value < 2.7 (ng/ml).

Conclusion

TSPAN1 levels are significantly reduced in patients with benign and PTC, demonstrating its potential value as a diagnostic biomarker. Additionally, the significant reduction in TSPAN1 mRNA expression within PTC tumor tissues may suggest its involvement in tumor progression and development. Further studies, including larger-scale validation studies and mechanistic investigations, are imperative to clarify the molecular mechanisms behind TSPAN1 and, ultimately, its clinical utility for treating thyroid disorders.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13176-8.

Keywords: Biomarkers, Benign lesions, Extracellular matrix, Papillary thyroid cancer, Tetraspanin 1

Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy, with the fast-growing worldwide incidence accounting for 213,000 new cases annually [1, 2]. Approximately 1–5% of these cancer cases occur in females and < 2% in males [3]. In light of the recent updates to the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms [4], thyroid tumor diagnostics have become increasingly precise, incorporating molecular and histopathological characteristics. This classification divides follicular cell-derived tumors into benign, low-risk, and malignant categories, refining diagnostic and prognostic accuracy. For instance, papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTCs) are categorized into BRAF-like and RAS-like neoplasms with specific molecular alterations and subtypes. Medullary thyroid carcinomas are further stratified using a new grading system based on mitotic count and tumor necrosis, offering a better understanding of their behavior.

The incidence rate of PTC, the most prevalent thyroid cancer subtype, rose more than any other thyroid malignancy [5]. Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is the first method of diagnosing PTC. Despite advancements in diagnosis strategies by FNAB, approximately 15–30% of thyroid FNABs cannot cytologically differentiate malignancy from benignity; thus, the report would remain “indeterminate thyroid lesions” [6]. The only way for these cases is FNAB repetition or, ultimately, lobectomy or thyroidectomy [7]. Surgical excision of the thyroid gland is more invasive and may damage the parathyroid glands and lead to calcium metabolism disorders. The surgery may also result in voice changes due to damage to the laryngeal nerves [8, 9]. In this circumstance, finding novel non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers that enable practitioners to distinguish between benign and malignant nodules is a prerequisite to avoiding FNAB repetition and unnecessary surgical procedures.

Tetraspanins (TSPANs) have been considered critical factors in regulating tumorigenesis in the history of developing cancer experiments [10]. TSPANs, a heterogeneous group of four transmembrane superfamilies, exist as TSPAN-enriched membrane microdomains (TEMs) [11]. TSPANs play major roles in signal transduction via interaction with several cell surface signaling molecules, including integrins and receptor tyrosine kinases [12]. Through this form, TSPANs are believed to play significant biological roles in physiological and pathophysiological processes, including cell migration, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [10, 12]. TSPAN1 has been recognized as a novel member of the TSPAN family of proteins located at chromosome 1 p34.1 [13]. Prior studies have noted the role of TSPAN1 in cancer angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis. However, the mechanisms of TSPAN1 remain a controversial subject in the cancer development field. TSPAN1 shows upregulation in some tumors, including gastric cancer [14, 15], colon cancer [16, 17], pancreatic cancer [18], and cervical cancer [19]. On the other hand, the expression of TSPAN1 is lower than that of normal tissues in a few different cancers [20]. For example, the expression of TSPAN1 was downregulated in progressive prostate cancer. Further, this study demonstrated that knockdown and overexpression of TSPAN1 in prostate cancer cell lines could inhibit cell proliferation and migration [20]. Although much uncertainty still exists about the relation between TSPAN1 and cancer progression, the studies mentioned above suggest a dual function of TSPAN1: oncogene and tumor suppressor gene.

The possible role of TSPAN1 in thyroid tumorigenesis remains obscure. Thus, we follow two primary aims of this study: (1) to evaluate the fluctuation of TSPAN1 levels in plasma samples of thyroid nodule patients and (2) to ascertain the mRNA expression of TSPAN1 in tissue samples of thyroid nodule patients. We also sought to find whether TSPAN1 expression levels could discriminate between malignancy and benignity.

Methods

Patients

This study was conducted in plasma and tissue samples of patients who underwent near-total or total thyroidectomy from November 2015 to August 2016 in Shariati Hospital. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.ENDOCRINE.REC.1395.367). Written informed consent was provided according to the local ethics committee guidelines and was obtained from all patients and healthy individuals before collecting data and samples.

Healthy subjects (N = 26) were volunteers referred to Saeed Pathobiology and Genetics Laboratory, Tehran, Iran, for routine medical examination. All healthy volunteers underwent evaluation of thyroid function tests (TSH, T4, T3, and freeT4) and the FBS test.

Fasting blood samples (5 ml) were collected from all case and control subjects in tubes containing ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA). Plasma was separated from whole blood samples by centrifuge for 10 min at 3,000 r.p.m. at 4 °C, then aliquoted into 1.5 ml Eppendorf microtubes and stored at − 80 °C prior to presentation for ELISA analysis.

Following thyroid surgery, a section of the tumor and adjacent tissues were immediately treated in RNAlater® RNA Stabilization Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and incubated overnight at 2–8 °C. Then, they were removed from the reagent and stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Based on the postoperative pathological examination and histological confirmation, a total of 150 thyroid tissue samples were collected, including PTC tumors (60 PTC, 60 paired normal tissues (PNT)) and benign (30 goitrous tissues) with an average size of 0.5 cm per each sample. Tumor staging was defined by the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging system [21].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for plasma TSPAN1

Plasma TSPAN1 analysis was done using a quantitative sandwich-type ELISA method according to the manufacturer’s specifications in three groups (PTC, benign, and healthy). TSPAN1 was appraised using a human TSPAN1 ELISA kit (ZellBio GmbH, Germany) with a minimum sensitivity of 0.1 ng/mL and an intra-assay percent coefficient of variation (%CV) 5.8. All measurements were fulfilled by skilled laboratory staff.

RNA extraction and complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, total mRNA was extracted from clinical tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The quantity and quality of the isolated RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA), after checking the total RNA’s purity based on the A260/A280 ratio. Additionally, the integrity of the RNA samples was analyzed through electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel (Ultra-Pure™ Agarose; Invitrogen).

To generate complementary DNA (cDNA), 3 µg of total RNA were subjected to reverse transcription using Thermo Scientific RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (1 µL of 200 U/µL), random hexamer primers (1 µl of 100 µM), deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) (2 µL of 10 mM), and RiboLock RNase inhibitor (0.5 µL of 40 U/µL). The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, followed by 42 °C for 60 min, in a total volume of 20 µL. The reaction was terminated by heating the samples at 70 °C for 10 min.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The primer sequence for the TSPAN1 gene was designed using Primer 3 and Gene Runner software. The specific primer sequences utilized were as follows: TSPAN1 forward primer, 5′-TCGAGCTGGCTGCCATGAT-3′, TSPAN1 reverse primer, 5′-TGCCTCTTCACAGTTCCCATG-3′, HPRT1 [22] (housekeeping gene) forward primer, 5′-CCCTGGCGTCGTGATTAGTG-3′, HPRT1 reverse primer, 5′-CACCCTTTCCAAATCCTCAGC-3′.

To evaluate the expression of the TSPAN1 gene, real-time PCR experiments were conducted using a Rotor-Gene 6000 instrument (Corbett, Life Science, Sydney, Australia). Each reaction was performed in a volume of 20 µl, comprising 10 µl of 2X SYBR Green Master mix (BIOFACT, South Korea), 1 µl of each forward and reverse primers (10 ng/µl), 7 µl of DEPC water, and 1 ml of total cDNA (100 ng/µl). The qRT-PCR protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by a three-step amplification program: 15 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 60 °C, and 40 s at 72 °C, with the melting curve, repeated 40 times.

The reference gene, HPRT1, was employed for normalizing mRNA levels. The relative quantity of mRNA in each sample was determined based on the threshold cycle (Ct) in comparison to the Ct of the housekeeping gene. To assess the relative expression of TSPAN1 across different groups, the 2–∆∆Ct method was employed [23].

Statistical analysis

The distribution of plasma level and gene expression data were checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and their distribution was non-normal, so non-parametric statistical methods were used. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare two groups of tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the PTC and benign groups. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to compare the TSPAN1 plasma level in three defined groups: healthy, benign, and PTC. Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal Wallis tests were used to compare mRNA and plasma levels in different clinicopathological statuses of PTC patients. Diagnostic tests were assessed by drawing the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) and calculating the area under the curve (AUC). Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 21, and statistical differences were considered significant at a P value < 0.05. For drawing graphs, GraphPad PRISM 6 software was used.

Cross-validation of findings with publicly available datasets

To validate our findings, we accessed publicly available datasets from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). GEO datasets were used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across thyroid cancer conditions [24, 25]. We further validated TSPAN1 expression using GEPIA2 (Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis) based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data [26]. The combination of both platforms provided a robust framework for cross-validation, ensuring the reliability of our results across multiple datasets.

Results

Study participants

The demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of the participants are outlined in Table 1. The study involved 90 subjects, including 60 patients with PTC (15 males, 45 females), 30 patients with benign nodules (5 males, 25 females), and 26 healthy individuals as a control group (5 males, 21 females). The mean age (mean ± SD, years) of the participants for each group was as follows: 37.6 ± 12.6 for PTC patients, 48.7 ± 13.4 for patients with benign lesions, and 40.5 ± 9.64 for healthy subjects. A significant difference in mean age was observed between the PTC and benign groups (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants and the clinicopathological characteristics of PTC patients

| Variables | PTC (n = 60) | Benign (n = 30) | Healthy (n = 26) | a P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.6 ± 12.6 | 48.7 ± 13.4 | 40.5 ± 9.64 | 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 15(25.0%) | 5(16.7%) | 5(19.2%) | 0.629 |

| Female | 45(75.0%) | 25(83.3%) | 21(80.8%) | |

| Clinicopathological characteristics | Number (%) | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 55 | 52 (86.7) | - | - | - |

| ≥ 55 | 6 (10.0) | - | - | - |

| BRAF V600E mutation-positive | 24 (40.0) | - | - | - |

| Tumor size | ||||

| < 2 cm | 38 (63.3) | - | - | - |

| ≥ 2 cm | 20 (33.3) | - | - | - |

| < 4 cm | 56 (93.3) | - | - | - |

| ≥ 4 cm | 2 (3.3) | - | - | - |

| b TNM stage based on AJCC | ||||

| I&II | 50 (83.3) | - | - | - |

| III&IV | 10 (16.7) | - | - | - |

| Extracapsular invasion positive | 14 (23.3) | - | - | - |

| Lymph node metastasis positive | 28 (46.7) | - | - | - |

| Lymph vascular invasion positive | 9 (15.0) | - | - | - |

| Variants | ||||

| Classic | 51 (85.0) | - | - | - |

| Follicular | 7 (11.7) | - | - | - |

| Hurtle cell | 1 (1.7) | - | - | - |

| Diffuse sclerosing | 1 (1.7) | - | - | - |

| Focality | ||||

| No multicentricity | 10 (16.7) | - | - | - |

| Unifocal | 11 (18.3) | - | - | - |

| Multifocal | 19 (31.7) | - | - | - |

PTC, papillary thyroid cancer

a P values are from the Mann–Whitney U test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

b American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging system

Alteration of TSPAN1 in the study specimens

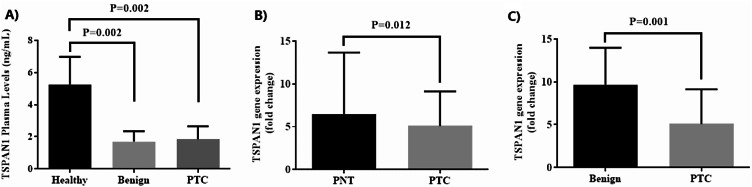

A sandwich-type ELISA-based method was used to determine plasma levels of TSPAN1 in three studied groups. Figure 1A shows that circulating levels of TSPAN1 in both PTC and benign groups were significantly decreased compared to healthy subjects (P = 0.002). No significant difference was found between PTC and benign groups in terms of TSPAN1 levels (P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

(A) The plasma level of TSPAN1 across three groups. (B, C) TSPAN1 mRNA expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma tissues (PTC) compared to the paired normal tissues (PNT) and benign tissues

When PTC and PNT were compared pairwise, the expression levels of TSPAN1 in cancerous tissues were significantly lower than in para-cancer normal thyroid tissues (Fig. 1B). A significant decrease in the mRNA level for TSPAN1 in PTC than benign was also observed (Fig. 1C).

Association of TSPAN 1 gene expression and plasma levels in PTC patients

The mRNA level of TSPAN1 was higher in PTC patients with lymph vascular invasion (10.10 (6.52, 20.3) vs. 4.44 (2.42, 7.14), P = 0.015), as illustrated in Table 2. This table also shows that the TSPAN1 levels had no significant relationship with other demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of PTC patients.

Table 2.

Association of TSPAN1 gene expression and plasma levels with clinicopathological variables in PTC patients

| Variables | Status | TSPAN1 plasma levels (ng/ml) | P value | TSPAN1 mRNA levels (fold change) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF V600E | Positive | 1.80 (1.60, 2.40) | 0.448 | 5.78 (2.33, 10.7) | 0.983 |

| Negative | 1.90 (1.60, 3.90) | 5.03 (3.14, 8.66) | |||

| Tumor size | < 2 cm | 1.90 (1.80, 2.60) | 0.867 | 4.44 (2.38, 7.02) | 0.404 |

| >=2 cm | 1.80 (1.60, 2.80) | 5.64 (3.55, 10.3) | |||

| TNM stage | I&II | 1.85 (1.60, 2.75) | 0.958 | 5.10 (2.88, 8.20) | 0.702 |

| III&IV | 1.90 (1.70, 2.78) | 5.39 (2.42, 20.6) | |||

| Extracapsular invasion | No | 1.80 (1.60, 2.65) | 0.277 | 5.43 (2.64, 10.6) | 0.576 |

| Yes | 1.95 (1.80, 5.53) | 5.03 (2.73, 7.02) | |||

| Lymph node metastasis | No | 2.15 (1.75, 2.90) | 0.142 | 4.96 (2.61, 7.02) | 0.382 |

| Yes | 1.80 (1.53, 2.30) | 5.47 (3.43, 11.3) | |||

| Lymph vascular invasion | No | 1.95 (1.60, 2.55) | 0.937 | 4.44 (2.42, 7.14) | 0.015 |

| Yes | 1.80 (1.75, 2.90) | 10.10 (6.52, 20.3) | |||

| Focality | No multicentricity | 3.85 (0.83, 4.95) | 0.313 | 4.96 (2.83, 7.02) | 0.159 |

| Unifocal | 2.00 (1.80, 2.40) | 4.00 (1.84, 9.13) | |||

| Multifocal | 1.80 (1.55, 1.90) | 5.78 (4.20, 10.5) |

Data are expressed as Median (INQ 25, 75)

Correlation between plasma and tissue TSPAN1 levels

Spearman’s correlation analysis has been performed to investigate the relationship between TSPAN1 levels in plasma and its tissue expression. The analysis revealed no significant correlation in any of the groups, including benign (Spearman’s ρ = 0.003, p = 0.989), PNT (Spearman’s ρ = 0.125, p = 0.569), and PTC (Spearman’s ρ = 0.009, p = 0.967) groups. These results indicate no strong association between plasma and tissue levels of TSPAN1, suggesting that plasma concentrations may not directly reflect tissue expression.

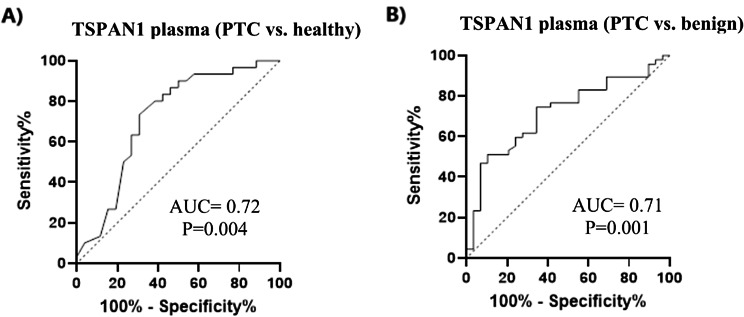

ROC curve analysis of TSPAN1

The diagnostic ability of TSPAN1 as a screening biomarker of PTC was evaluated using ROC curve analyses. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.72 (P = 0.004) in PTC vs. healthy with 76.7% sensitivity and 65.4% specificity at a predicted probability cutoff value < 2.7 (ng/ml) (Fig. 2A). The AUC value for TSPAN1 in PTC vs. benign was 0.71 (P = 0.001) with 74.5% sensitivity and 65.5% specificity at a predicted probability cutoff value < 7.3 (ng/ml). (Fig. 2B). To address the potential limitations due to the small number of disease-free participants, we applied the bootstrap resampling method to enhance the reliability of the cutoff point for TSPAN1 levels in plasma. A total of 1000 bootstrap samples were generated, and the cutoff point was reassessed using Youden’s Index. The bootstrapped ROC curve yielded an AUC of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.67–0.77), consistent with the results from the parametric approach. However, the optimal cutoff point was slightly adjusted to 2.9 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 78.5% and a specificity of 70.3%. This represents a marginal improvement over the initial 2.7 ng/mL cutoff point derived from the parametric method. This bootstrapped analysis provides more robust and reliable estimates of the diagnostic threshold, particularly given the sample size limitations of our study.

Fig. 2.

(A) ROC curve analysis of TSPAN1 plasma levels in the discrimination of PTC (papillary thyroid carcinoma) from healthy subjects, and (B) PTC from benign

Analysis from GEO and, followed by validation using GEPIA2

We identified two relevant datasets, GSE35570 [27] and GSE60542 [28], from the GEO and European Array Express databases for further analysis [29]. GSE35570 comprises 65 PTC samples from children and young adults obtained via DNA microarray (Affymetrix Human Genome U133 2.0 Plus). These samples were divided into two groups: 33 cases exposed to radiation (ECR) born before the Chernobyl disaster and 32 non-ECR cases born at least nine months afterward. Our study focused exclusively on the non-ECR PTC samples as the test group, with normal thyroid tissues as the control group. Data preprocessing (filtering and normalization) and statistical analysis were performed using ge-Workbench (v2.6.0) software [24]. DEGs were identified based on an adjusted P-value < 0.01 and |LogFC| > 0.5. Notably, TSPAN1 was identified as a downregulated DEG in this dataset, with a LogFC of -0.782 and an adjusted P-value of 0.00339 (Table S1).

GSE60542 contains transcriptomic data from 13 PTC samples with the papillary histological subtype as the test group, compared to 13 normal thyroid tissues as the control. The same preprocessing and statistical methods (t-test) were applied using ge-Workbench (v2.6.0). DEGs were filtered with thresholds of P-value < 0.05 and |LogFC| > 0.5. In this dataset, TSPAN1 was also identified as a downregulated DEG, with a LogFC of -0.867 and P-value of 0.0373 (Table S2).

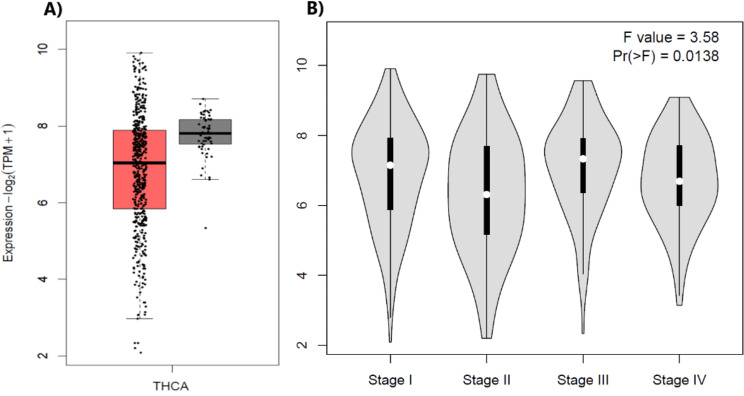

After identifying TSPAN1 as a downregulated gene in both GEO datasets, we further validated its expression using GEPIA2 [30], leveraging RNA-seq data from the TCGA and GTEx databases. The comparison was generated using a P-value cutoff of < 0.01 and a log2 fold change (log2FC) cutoff of > 1, ensuring statistical significance and biological relevance. These thresholds were applied to distinguish meaningful changes in TSPAN1 expression between thyroid cancer samples and normal thyroid tissues from the TCGA dataset. The results indicate that the median expression of TSPAN1 is lower in thyroid cancer samples than in normal tissues, suggesting the downregulation of TSPAN1 in thyroid cancer (Fig. 3A). However, these changes were not significant. A statistical analysis (ANOVA) yielded an F-value of 3.58 and a P-value of 0.0138, indicating a significant difference in TSPAN1 expression between stages. The expression appears to follow a decreasing trend as the cancer progresses, with the highest levels observed in Stage I and a reduction by Stage IV. This suggests TSPAN1 downregulation may correlate with more advanced disease stages (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

(A) The box plot of thyroid carcinoma (THCA) illustrates the expression levels of TSPAN1 in 512 thyroid cancer samples (red box) compared to 59 normal thyroid tissues (dark gray box) derived from GEPIA2 using TCGA datasets. The y-axis represents the log2(TPM + 1) expression values, providing normalized gene expression for accurate comparison. (B) The violin plot depicts the expression levels across four cancer stages (Stage I to Stage IV). This axis measures the expression levels (on a log2 scale(TPM + 1)

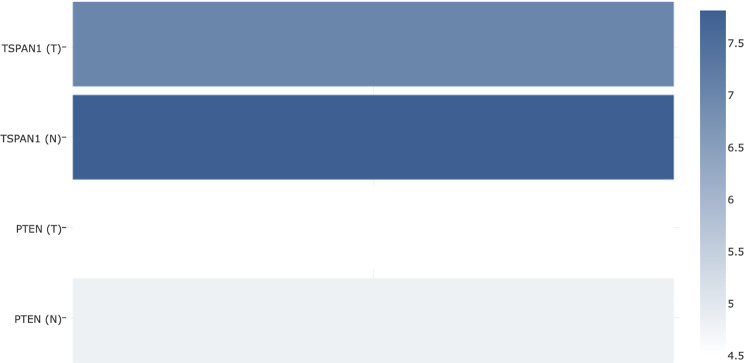

Additionally, we explored the co-expression between TSPAN1 and PTEN, which revealed that both genes exhibit similar expression patterns, suggesting potential co-regulation or functional interaction in thyroid cancer.

Discussion

TSPAN1 is a member of the tetraspanins superfamily, which comprises a diverse group of transmembrane proteins involved in various cellular processes [12]. TSPANs have been implicated in regulating cell adhesion, migration, invasion, and signaling modulation [31]. Through its interactions with other membrane proteins, including integrins, growth factor receptors, and immune cell receptors, TSPANs play a crucial role in organizing membrane microdomains known as TEMs [10, 12]. These TEMs facilitate dynamic protein-protein interactions and modulate intracellular signaling cascades, thereby influencing cellular behavior and function [10]. TSPAN1 has been implicated in numerous cancer types, exhibiting either tumor-promoting or tumor-suppressive effects depending on the specific context. However, the role of TSPAN1 in thyroid cancer remains largely unexplored. In this study, we investigated the plasma levels of TSPAN1 and its mRNA expression in PTC patients, comparing them to both healthy individuals and benign nodules.

Our experiment revealed a significant decrease in plasma levels of TSPAN1 in patients with benign and PTC compared to the healthy control group. Additionally, we observed a notable reduction in TSPAN1 mRNA expression within PTC tissues compared to paracancer non-tumoral tissues and the benign group. These findings have important implications for understanding the role of TSPAN1 in PTC development and progression. Notably, a review of online databases further corroborated the downregulation of this marker in thyroid cancer, supporting our experimental results. This highlights the potential of TSPAN1 as a valuable biomarker for studying PTC development and progression.

Several studies have conclusively shown that TSPAN1 is significantly upregulated in various types of cancer [14–16, 19, 32]. This upregulation has been directly linked to tumor progression, metastasis, and unfavorable prognosis. Chen et al. (2009) conducted a study revealing that TSPAN1 expression considerably increased in colorectal cancer tissues, leading to a lower overall survival rate. In related studies, the activation of the AKT signaling pathway by TSPAN1 led to increased migration and invasion of cancer cells [33, 34]. In contrast, our study found that TSPAN1 expression was significantly downregulated in PTC patients compared to healthy individuals and patients with benign nodules. These findings are consistent with a previous study by Xu et al. (2016), which reported that TSPAN1 could inhibit cell proliferation and migration in prostate cancer (PCa) cell lines [20]. These findings highlight the potential tumor-suppressive role of TSPAN1 in cancer development and progression.

On the other hand, the finding of high TSPAN1 expression in cases of lymph node invasion in our study could be explained by considering the complex role that TSPAN1 plays in different stages of tumor development and progression. Specific cells within the tumor may undergo changes that result in increased TSPAN1 expression. This upregulation could be related to the tumor’s attempt to enhance its invasive capabilities. Higher TSPAN1 levels might be associated with increased cell motility and invasion into nearby tissues, such as lymph nodes. This could explain the observed high expression of TSPAN1 in cases of lymph node invasion. Nonetheless, lymph node invasion cases in our study were limited to only 9 samples. Therefore, the deeper we delve into our investigation, the more comprehensive our understanding becomes of the events occurring at each stage of cancerous cell progression.

A positive correlation between TSPAN1 and PTEN expression in both clinical specimens and mouse models of prostate cancer has been reported [20]. PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene that regulates cell growth and survival by inhibiting the Akt signaling pathway [35]. The combination of TSPAN1 and PTEN as markers showed increased predictive value, particularly in low-risk patients [20]. These findings suggest that the co-assessment of TSPAN1 and PTEN may enhance the predictive power of these markers in identifying patients with more aggressive prostate cancer. In our study, we did not directly examine the correlation between TSPAN1 and PTEN expression in thyroid disorders. However, previous studies from our group have reported that PTEN protein statuses are markedly decreased in PTC and MNG compared to healthy persons [36]. Moreover, in another study, the mRNA expression of PTEN in PTC was reported to be significantly lower than in adjacent non-tumoral tissues [37]. Additionally, analysis of GEPIA2 revealed a parallel decrease in PTEN and TSPAN1 expressions in thyroid cancer (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The comparative expression bar chart compares the expression levels of TSPAN1 and PTEN in tumor (T) and normal tissue (N). Both TSPAN1 and PTEN exhibit lower expression in tumor tissues than normal tissues; however, the reduction for TSPAN1 is more modest compared to PTEN

Given the similar downregulation of TSPAN1 and PTEN observed in both thyroid nodules and prostate cancer, it is plausible to speculate that TSPAN1 and PTEN may also exhibit a correlated expression pattern in thyroid tissues. Future investigations focusing on the relationship between TSPAN1 and PTEN in thyroid nodules could provide valuable insights into the shared molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways involved in different cancers.

The contrasting results regarding TSPAN1 expression in PTC and other cancers highlight the context-specific nature of TSPAN1 in cancer development and progression. The underlying mechanisms contributing to the differential expression patterns of TSPAN1 across cancer types remain unclear. However, studies suggest that TSPAN1 may interact with different signaling pathways and molecular targets in other cancer types, leading to distinct biological outcomes.

Although our findings shed light on the potential diagnostic and prognostic value of TSPAN1 in thyroid disorders, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size of our study was relatively small, warranting validation in larger cohorts to ensure the robustness of the observed associations. Secondly, our study focused on plasma levels of TSPAN1 and its mRNA expression, and additional investigations into TSPAN1 expression in protein levels would provide a more comprehensive understanding of its involvement in thyroid disorders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates a substantial decrease in plasma levels of TSPAN1 in patients with benign and PTC, suggesting its potential as a diagnostic biomarker. Additionally, the notable reduction in TSPAN1 mRNA expression within PTC tumor tissues supports its involvement in tumor development and progression. Our findings are further corroborated by data retrieved from publicly available databases such as GEO and GEPIA2, which revealed a similar downregulation of TSPAN1 in thyroid cancer tissues compared to normal tissues. Notably, the analysis also identified concurrent downregulation of PTEN, a well-established tumor suppressor, in the same datasets. This alignment between our experimental data and external databases strengthens the robustness of our findings and suggests that the combined reduction of TSPAN1 and PTEN may have synergistic effects on tumor progression, potentially disrupting critical signaling pathways involved in cellular communication, proliferation, and survival.

Further research, including larger-scale validation studies and mechanistic investigations, is warranted to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms and validate the clinical utility of TSPAN1 in managing thyroid disorders. Ultimately, identifying reliable biomarkers such as TSPAN1 could improve early detection, risk stratification, and treatment decisions for patients with thyroid disorders, leading to improved patient outcomes and personalized therapeutic strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to S. Adeleh Razavi for her assistance in collecting samples from individuals.

Abbreviations

- PTC

Papillary thyroid cancer

- FNAB

Fine needle aspiration biopsy

- TSPANs

Tetraspanins

- TEMs

TSPAN-enriched membrane microdomains

- EDTA

Ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid

- PNT

Paired normal tissues

- TNM

Tumor-Node-Metastasis

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- AUC

Area under the curve

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

Author contributions

R.A., Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. M. Z. and M.S. Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis. M. A. and M.S. Software, Formal analysis. F. S., Formal analysis, Resources. M.H., Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Data curation.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.ENDOCRINE.REC.1395.367).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maryam Zarkesh, Email: zarkesh@endocrine.ac.ir, Email: zarkesh1388@gmail.com.

Mehdi Hedayati, Email: hedayati@endocrine.ac.ir, Email: hedayati47@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Safavi A, Azizi F, Jafari R, Chaibakhsh S, Safavi AA. Thyroid cancer epidemiology in Iran: a time trend study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(1):407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jajin MG, Abooshahab R, Hooshmand K, Moradi A, Siadat SD, Mirzazadeh R, et al. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-based untargeted metabolomics reveals metabolic perturbations in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahbari R, Zhang L, Kebebew E. Thyroid cancer gender disparity. Future Oncol. 2010;6(11):1771–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baloch ZW, Asa SL, Barletta JA, Ghossein RA, Juhlin CC, Jung CK, et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of thyroid neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33(1):27–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse S et al. Seer cancer statistics review, 1975–2010, national cancer institute. bethesda, md. 2013.

- 6.Abooshahab R, Ardalani H, Zarkesh M, Hooshmand K, Bakhshi A, Dass CR, et al. Metabolomics—a tool to find metabolism of endocrine cancer. Metabolites. 2022;12(11):1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand B, Ramdas A, Ambroise MM, Kumar NP. The Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology: a cytohistological study. J Thyroid Res. 2020;2020(1):8095378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan E, Angelos P, Applewhite M, Mercier F, Grogan RH. Surgery of the thyroid. Endotext [Internet]. 2015.

- 9.Lukinović J, Bilić M. Overview of thyroid surgery complications. Acta Clin Croatica. 2020;59(Supplement 1):81–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charrin S, Jouannet S, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Tetraspanins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(17):3641–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berditchevski F, Odintsova E, Sawada S, Gilbert E. Expression of the palmitoylation-deficient CD151 weakens the association of α3β1 integrin with the tetraspanin-enriched microdomains and affects integrin-dependent signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(40):36991–7000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Termini CM, Gillette JM. Tetraspanins function as regulators of cellular signaling. Front cell Dev Biology. 2017;5:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serru V, Dessen P, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Sequence and expression of seven new tetraspans. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA)-Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 2000;1478(1):159–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Z, Luo T, Nie M, Pang T, Zhang X, Shen X, et al. TSPAN1 functions as an oncogene in gastric cancer and is downregulated by miR-573. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(15):1988–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai Y, Zheng M, Zhao Z, Huang H, Fu W, Xu X. Expression of Tspan–1 gene in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(3):2996–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L, Zhu Y-Y, Zhang X-J, Wang G-L, Li X-Y, He S, et al. TSPAN1 protein expression: a significant prognostic indicator for patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterology: WJG. 2009;15(18):2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C-H, Im E-J, Moon P-G, Baek M-C. Discovery of a diagnostic biomarker for colon cancer through proteomic profiling of small extracellular vesicles. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Shi G, Gao F, Liu P, Wang H, Tan X. TSPAN1 upregulates MMP2 to promote pancreatic cancer cell migration and invasion via PLCγ. Oncol Rep. 2019;41(4):2117–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wollscheid V, Kühne-Heid R, Stein I, Jansen L, Köllner S, Schneider A, et al. Identification of a new proliferation‐associated protein NET‐1/C4. 8 characteristic for a subset of high‐grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;99(6):771–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu F, Gao Y, Wang Y, Pan J, Sha J, Shao X, et al. Decreased TSPAN1 promotes prostate cancer progression and is a marker for early biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Oncotarget. 2016;7(39):63294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaspersz MP, Buettner S, van Vugt JL, de Jonge J, Polak WG, Doukas M, et al. Evaluation of the new American joint committee on cancer staging manual 8th edition for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:1612–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Razavi SA, Afsharpad M, Modarressi MH, Zarkesh M, Yaghmaei P, Nasiri S, et al. Validation of reference genes for normalization of relative qRT-PCR studies in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Floratos A, Smith K, Ji Z, Watkinson J, Califano A. geWorkbench: an open source platform for integrative genomics. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(14):1779–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sameni M, Mirmotalebisohi SA, Dadashkhan S, Ghani S, Abbasi M, Noori E, et al. COVID-19: a novel holistic systems biology approach to predict its molecular mechanisms (in vitro) and repurpose drugs. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2023;31(2):155–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handkiewicz-Junak D, Swierniak M, Rusinek D, Oczko-Wojciechowska M, Dom G, Maenhaut C, et al. Gene signature of the post-chernobyl papillary thyroid cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1267–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarabichi M, Saiselet M, Trésallet C, Hoang C, Larsimont D, Andry G, et al. Revisiting the transcriptional analysis of primary tumours and associated nodal metastases with enhanced biological and statistical controls: application to thyroid cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(10):1665–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Rudnev D, Evangelista C, et al. NCBI GEO: mining tens of millions of expression profiles—database and tools update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(suppl1):D760–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Abstract Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–W560. 10.1093/nar/gkz430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Munkley J, McClurg UL, Livermore KE, Ehrmann I, Knight B, Mccullagh P, et al. The cancer-associated cell migration protein TSPAN1 is under control of androgens and its upregulation increases prostate cancer cell migration. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Mayea Y, Mir C, Carballo L, Castellvi J, Temprana-Salvador J, Lorente J, et al. TSPAN1: a novel protein involved in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma chemoresistance. Cancers. 2020;12(11):3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Liang Y, Yang G, Lan Y, Han J, Wang J, et al. Tetraspanin 1 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of cholangiocarcinoma via PI3K/AKT signaling. J Experimental Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y, Chen W, Gong Y, Liu H, Zhang B. Tetraspanin 1 (TSPAN1) promotes growth and transferation of breast cancer cells via mediating PI3K/Akt pathway. Bioengineered. 2021;12(2):10761–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Georgescu M-M. PTEN tumor suppressor network in PI3K-Akt pathway control. Genes cancer. 2010;1(12):1170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Razavi SA, Modarressi MH, Yaghmaei P, Tavangar SM, Hedayati M. Circulating levels of PTEN and KLLN in papillary thyroid carcinoma: can they be considered as novel diagnostic biomarkers? Endocrine. 2017;57:428–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Razavi SA, Salehipour P, Gholami H, Sheikholeslami S, Zarif-Yeganeh M, Yaghmaei P, et al. New evidence on tumor suppressor activity of PTEN and KLLN in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Pathology-Research Pract. 2021;225:153586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.