Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the relationships between life events and psychological distress in the postepidemic era as well as the effects of fear of COVID-19 (FCV-19) and impermanence on these relationships to enrich the study of the underlying psychological mechanisms of postepidemic psychological distress and to provide a theoretical basis for scientific prevention and intervention in individuals with psychological distress.

Methods

A survey of 504 adults (71.3% female; age M = 26.87, SD = 10.70) was conducted via the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, the FCV-19 Scale, the Impermanence Scale, the Anxiety Scale and the Depression Scale, and a structural equation model was established to explore the relationships between variables.

Results

The present study revealed the following: (1) there is a significant positive correlation between life events and psychological distress; (2) FCV-19 completely mediates the relationship between life events and psychological distress; and (3) impermanence moderates the mediation, regulating the path by which life events affect FCV-19 and the path by which FCV-19 affects psychological distress.

Conclusions

In the postepidemic era, impermanence can effectively mitigate the impact of life events on FCV-19 and the impact of FCV-19 on psychological distress.

Keywords: Fear of COVID-19, Impermanence, Psychological distress, Life events, Postepidemic era moderated mediation model

Introduction

The global spread of COVID-19 has led to widespread devastation, causing significant changes in the economy, social relationships, and lifestyles and impacting the mental health of individuals across age groups and populations with diverse sociocultural backgrounds [1, 2]. Researchers have shown that stressful life events, such as changes in marriage, the death of family members, and the loss of jobs after COVID-19, are significantly correlated with psychological disturbances in the general population [3]. Converging research also indicates that the incidence of mental disorders such as anxiety disorders and depression substantially increased after the epidemic, which has notably affected the psychological well-being of the general population [4]. Life events, as chronic stressors, can be very stressful if effective coping is not provided, affecting the physical and mental health of individuals [5–8]. Negative life events, such as unemployment, the passing of a family member, or interruptions to schooling, became more prevalent during the pandemic. These experiences can directly or indirectly increase the levels of stress individuals experience, subsequently impacting their mental well-being [9, 10]. Life events serve as a common source of psychosocial stress, which can lead individuals to experience increased psychological strain, including heightened levels of anxiety and depression [11–14]. COVID-19 significantly increased the occurrence of negative life events such as the interruption of studies, disease, bankruptcy, and death through direct or indirect effects. These negative life events undeniably increased the public’s fear of COVID-19 (FCV-19).

The high infectivity of the virus, along with daily updates on infection rates, heightened FCV-19 among the public and posed direct threats to both physical and psychological well-being. When individuals suffer continuous stress, they cannot respond to and control dangerous situations and thus develop fear. This primitive feeling is directed at a real or perceived threat [15]. The COVID-19 pandemic has created multiple challenges, including a significant psychological toll on the general population [16]. Previous studies have shown that after an epidemic, many people develop various fears, including the fear of being infected and the recurrence of the disease [17, 18]. This fear is an emotional state that affects the way people process cognition and exacerbates psychological distress. In addition to general life events after the epidemic, many people’s fears of the epidemic undoubtedly increase their previous daily stress and mental health distress.

Chen et al. used a cross-sectional study to investigate the symptoms of anxiety, depression, insomnia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among 22,624 college students in the postepidemic era [19]. The results revealed that FCV-19 increased anxiety, depression, and other forms of psychological distress among college students. Dong et al. reported that fear of the COVID-19 epidemic directly and indirectly affects individuals’ psychological distress through risk perceptions, such as FCV-19 [20].

Another study revealed that people with more positive attitudes and attitudes have lower levels of psychological distress [21–23], indicating that positive attitudes may have moderating effects. Impermanence is a concept based on Buddhist philosophy that expresses an attitude toward life change. Impermanence can potentially reduce life stress by cultivating an interpretation of challenging circumstances [24]. One study reported that both awareness and acceptance of impermanence were positively associated with mental well-being [25]. Therefore, this study explored the correlations between general life events and FCV-19, attitudes toward life and emotional distress to enrich the study of the mechanisms of psychological distress and provide a theoretical basis for scientific prevention and intervention during postepidemic times.

Life events and psychological distress

The main manifestations of psychological distress are anxiety and depression [23, 26]. Previous research has established an association between recent life events and depressive disorders [27–29]. The continuous accumulation of various stressful life events can also lead to an increase in depressive symptoms [12]. Several studies have shown that recent life events can increase individuals’ susceptibility traits and aggravate their anxiety [30, 31]. Pressure from various life events has continued into the postepidemic era, impacting people’s mental health. Accordingly, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1

Life events positively predict psychological distress.

COVID-19 fear

Several researchers have noted the worldwide interruption of study, bankruptcy, loss of jobs, loss of family members and indifference caused by COVID-19; when these events occur, they trigger stress and negative emotions in those who experience them [32], adversely affecting their cognitions, emotions, and behaviors [33] and increasing their fear of another outbreak [18].

During the COVID-19 epidemic, fear is a common emotional response [15] and can include a negative emotional response or continuous worry about impending public health events such as COVID-19-related death and disease [34]. The parallel process model of fear expansion defines fear as a negative arousal emotion generated by overestimating the probability of dangerous situations [35]. During the COVID-19 pandemic and the current stage of standardized prevention and control, the main causes of fear were fear of being infected and worries about a recurrence of the epidemic [17]. Additionally, fear of being infected and fear due to uncertainty about the epidemic are also positively correlated with various mental illnesses, such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders [36].

According to the above analysis and the derivation of H1, life events affect not only psychological distress but also FCV-19, and in turn, FCV-19 affects psychological distress. As such, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2

Life events positively predict psychological distress through the mediating effect of FCV-19.

Impermanence

An increasing body of literature has begun to investigate the moderating and mediating factors in the relationship between stress and emotion. According to the gross emotion regulation process model, cognitive reappraisal is an antecedent-focused strategy that is used in the early stages of emotion generation. Its main goal is to lessen the emotional response by altering how emotional events are understood and their personal significance [37]. Impermanence is a cognitive factor that is a cornerstone of Buddhist philosophy and is positively associated with individual mental health [24, 25]. When individuals experience pressure from adverse life events in the postepidemic era, developing life events may positively predict psychological distress through the mediating effect of FCV-19. As a cognitive reappraisal strategy, impermanence may change an individual’s understanding of stress and fear in the early stages of the emotional response, potentially reducing fear and distress. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 3

Impermanence moderates the path by which life events affect the fear and psychological distress caused by the epidemic and by which FCV-19 affects psychological distress.

The present study

Despite the established association between life events and psychological distress, the understanding of the role of FCV-19 within this context is limited. The research question of this study is as follows: How does impermanence moderate the direct and indirect effects of FCV-19 on the relationship between life events and psychological distress? Within the framework of the parallel process model of fear expansion and the gross emotion regulation process model, this study examines the interrelationships among these variables.

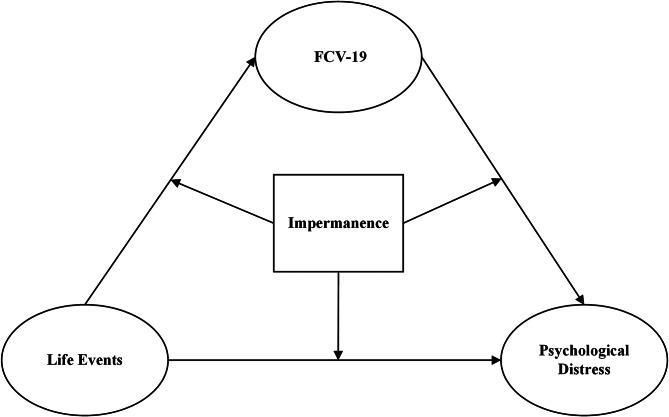

In summary, this study constructed a moderated mediation model (Fig. 1) to investigate the effects of life events, FCV-19, and impermanence on psychological distress in the postepidemic era. Specifically, this study investigated how life events affect psychological distress in the postepidemic era, the mediating role of FCV-19 and the moderating role of the level of impermanence in this process. The objective of this study is to provide empirical support and theoretical guidance for long-term interventions in psychological distress during the postepidemic era.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical model

Methods

Study Design and participants

A cross-sectional study was performed via convenience sampling to recruit participants. Convenience sampling was used to ensure the timeliness of the study, as people’s psychological distress, FCV-19 and perceptions of impermanence can change rapidly as the pandemic progresses. We compiled the questionnaire links and codes through Questionnaire Star (问卷星) and distributed them to the participants. The inclusion criteria were (1) being at least 18 years old and (2) residing in mainland China with experiences of quarantine during the pandemic. The exclusion criteria included (1) previous diagnoses of severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, (2) refusal to consent to participate, and (3) questionnaires that were completed too hastily or provided inaccurate responses for validity checks. Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure the reliability of the scale.

Study sample size

Our study was conducted from May to August 2023. Numerous researchers have emphasized the importance of sample size in modeling and CFA studies, noting that SEM (including CFA) requires a minimum of 200 participants [38]. After deleting invalid questionnaires, such as those with consistent responses and overly quick completion times, a total of 536 valid questionnaires were obtained, for an effective rate of 85.9%. In the subsequent analysis, the topic packaging strategy was used in this study, and the packaged indicators could be distinguished more finely, the skewness was corrected [39], and the skewness distribution became normal [40, 41]. Therefore, 536 samples meet the requirements of this study. In this investigation, there were 154 males and 382 females. The participants were between 18 and 71 years of age (26.87 ± 10.70).

Measurement

Life events

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (Adult Scale) compiled by Holmes and Rahe was used to assess life events [42]. There were a total of 43 items, which may be composed of stressful life events predisposing patients to the disease. Different life events are assigned different points, e.g., “death of spouse” 100 points, “divorce” 73 points, and “marriage failure (separation)” 65 points. Since this scale was used after translation and considering the differences in culture and lifestyle, Item 40, “Changes in eating habits”, was deleted; Item 35, “Changes in church activities”, was changed to “Changes in belief activities”; Item 37, “Loans less than USD 10,000”, was changed to “loans less than RMB 10,000”; and Question 42, “Celebrating Christmas”, was revised to “Celebrating the Spring Festival”. The marked events were summed to obtain the total score. Higher scores indicate more severe stress from life events. In the present study, the α coefficient of this scale was 0.85.

Fear of COVID-19

In this study, the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19 S), developed by Ahorsu et al. and revised by Chi et al. [43, 44], was used to assess individuals’ fear levels of the novel coronavirus. This bidimensional scale contains 7 items and is scored on a five-point scale, from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 points “strongly agree”, where 1, 2, 4, and 5 represent fear thoughts and 3, 6, and 7 represent physical responses. The total score was calculated, with higher scores indicating greater levels of FCV-19. The α coefficient of the original scale was 0.82, but the α coefficient in the present study was 0.92.

Impermanence

The Impermanence Awareness and Acceptance Scale (IMAAS) was used to measure the degree of understanding of the transient nature of all the phenomena and the acceptance of the transient nature of all the phenomena [25]. This scale has 13 items and two subscales (awareness of impermanence and acceptance of impermanence). All the items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = neutral, 7 = strongly agree). Sample items of the “consciousness of impermanence” subscale and the “acceptance of impermanence” subscale are “I realize that life is short” and “nothing in life scares me forever”. After the reverse score of the impermanence acceptance subscale was corrected and the mean values of these two factors were calculated, the total IMAAS score increased, reflecting a greater level of understanding and acceptance of impermanence. The α coefficient of the original scale was 0.81, and the α coefficient in the present study was 0.63.

Depression

The 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire was used to assess depressive symptoms [45]. The respondents were asked to answer on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 3 = almost every day). This scale has good reliability and validity in Chinese and American populations. For example, the internal reliability of this scale in Chinese patients is 0.76 [46], the sensitivity of the PHQ-2 for major depressive disorders is 87%, and the specificity is 78% [47]. An example item is “No interest or pleasure in doing things.” The depression score was obtained by averaging the scores of all the items and was used in the subsequent analysis. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms; the α coefficient in the present study was 0.86.

Anxiety

The 2-item generalized anxiety disorder scale was used to measure the frequency of anxiety symptoms in the participants in the past two weeks [48, 49]. All the items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 3 = almost every day). An example is “unable to stop or control worry.” This scale has satisfactory reliability and validity in Chinese and American populations [49, 50]. The α coefficient in the present study was 0.908.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and common method bias testing were conducted via SPSS 27.0. A structural equation model (SEM) was established and tested via AMOS 24.0. Harman’s single-factor test was employed to evaluate common method bias prior to data analysis. The results indicated that the eigenvalues of all 20 unrotated factors were greater than 1, with the first factor explaining 13.2% of the variance, which is considerably less than the critical value of 40%. Consequently, common method bias was not significant in this study [51].

SEM was employed to construct a model with life events as the independent variable, FCV-19 as the mediating variable, impermanence as the moderating variable, and psychological distress as the dependent variable. Several fit indices were used to examine the data-model fit: (i) a χ2/df ratio, a value ≤ 3 indicates an acceptable fit [52], whereas a value ≤ 5 suggests a reasonable fit [53]; (ii) a comparative fit index (CFI), a value > 0.95 reflects satisfactory fit [54], whereas a value between 0.90 and 0.95 indicates acceptable fit [55]; (iii) a root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), a value of 0.05 or less indicates a close fit, while a range of 0.05 to 0.08 suggests an adequate fit [56]; and (iv) an adjusted goodness-of-fit index, AGFI, a value > 0.90 indicates acceptable fit [57].

In this study, owing to the complexity of the model and the number of estimated parameters, the topic packaging method was used to simplify the model in the subsequent analysis. The main manifestations of psychological distress are anxiety and depression [23, 26]; therefore, this study used depression and anxiety as explicit variables of psychological distress. In accordance with Wu and Wen [58], for the life events scale, the balance method in the factor method was adopted according to the level of the factor loading values of the items, and the life events scale was packaged into six groups. The depression scale and the anxiety scale were divided into groups and used as explicit variables for assessing psychological distress; the fear thoughts and physical response scores of the FCV-19 subscale were packaged as a group and used as an explicit variable of the FCV-19.

To elucidate the essence of the interaction, further analysis of the moderating effect of impermanence was conducted through simple effects plots. Following the recommendations of Preacher et al. [59], individuals were divided into high and low groups on the basis of one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively.

Results

Correlation analysis was conducted on the total scores of each scale, revealing significant correlations. Life events were significantly associated with fearful thoughts, physical reactions, anxiety, and depression. Fearful thoughts related to FCV-19 were significantly correlated with all the variables except age. All the physical responses to FCV-19 were significantly correlated with all the variables except age and sex. Anxiety was significantly correlated with all the variables except sex. Depression was significantly correlated with all the variables except sex. The correlation coefficients among the variables are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficient matrix for each variable (n = 536)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Sex | — | — | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Age | 26.87 | 10.70 | -0.08 | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Life events | 136.05 | 104.98 | 0.004 | 0.20** | 1 | |||||

| 4 Fear thoughts | 9.47 | 3.99 | 0.12** | -0.03 | 0.18** | 1 | ||||

| 5 Physical responses | 5.57 | 2.57 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.16** | 075** | 1 | |||

| 6 Impermanence | 29.44 | 4.34 | 0.01 | -0.03 | 0.07 | -0.21** | -0.31** | 1 | ||

| 7 Anxiety | 2.34 | 1.84 | -0.001 | 0.33** | 0.12** | 0.21** | 0.20** | -0.11** | 1 | |

| 8 Depression | 2.34 | 1.70 | 0.03 | 0.31** | 0.09** | 0.24** | 0.23** | -0.11** | 0.81** | 1 |

M is the mean, and SD is the standard deviation. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; the same applies below.

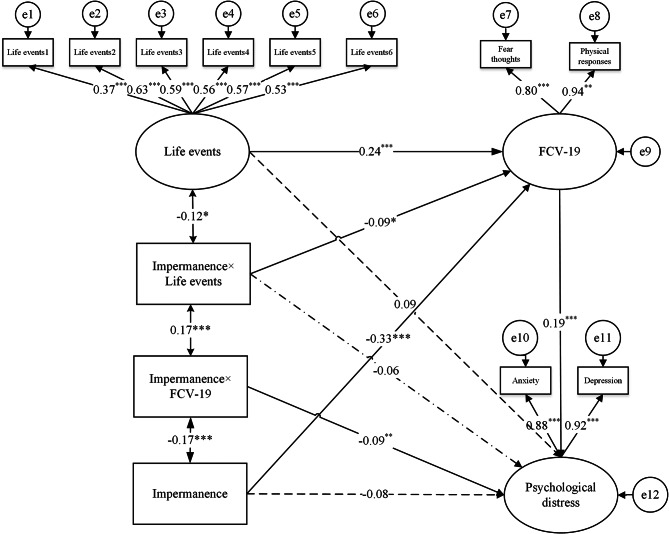

The SEM fit indices were favorable: χ2/df = 3.56, CFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.91, and RMSEA = 0.07. The results are shown in Fig. 2. Life events significantly positively predicted FCV-19 (β = 0.24, P < 0.001), and FCV-19 significantly positively predicted psychological distress (β = 0.19, P < 0.001). The direct impact of life events on psychological distress was not significant. FCV-19 fully mediated the influence of life events on psychological distress. In addition, impermanence significantly negatively affected FCV-19 (β=-0.33, P < 0.001); Impermanence X life events had a significant effect on FCV-19 (β=-0.09, P < 0.05); and impermanence X FCV-19 had a significant effect on psychological distress (β=-0.09, P < 0.05). The effect of impermanence X life events on psychological distress was not significant. We used the bootstrap method to further test the hypothesized model, setting the number of self-samples to 5000. The bias-corrected 95% CIs showed that under conditions of impermanence lower than or equal to one standard deviation, the intervals between the mediation effects were [0.005, 0.042] and [0.003, 0.064] (P < 0.05), respectively, neither of which contained 0. These results suggest that under medium and low levels of impermanence, impermanence plays a regulatory role in both the first half and the second half of the pathway of this mediation model, and a moderated mediation model was established.

Fig. 2.

Effects of life events, FCV-19, and impermanence on psychological distress (n = 536)

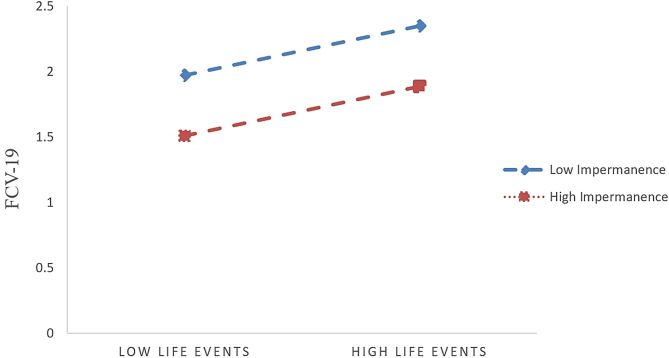

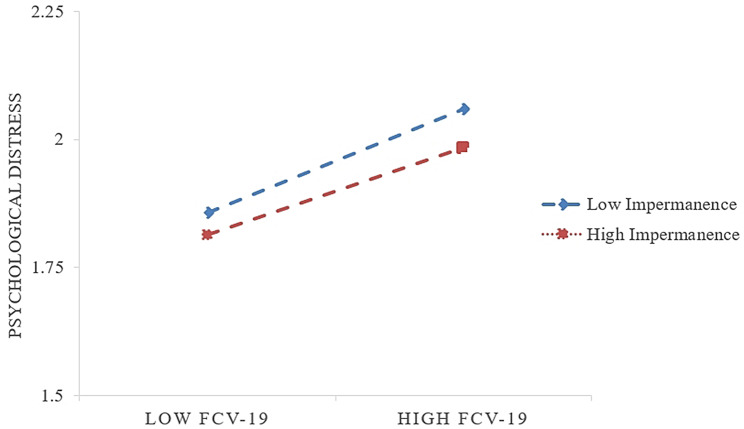

The results of the simple effects analysis shown in Fig. 3 indicate that when impermanence levels are low, life events significantly and positively predict FCV-19 (Bsimple=0.13, P < 0.001). When impermanence levels are high, the positive predictive effect of life events on FCV-19 weakens (Bsimple=0.12, P < 0.001). These findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of impermanence experience less FCV-19. The results of the simple effect analysis shown in Fig. 4 reveal that when the impermanence level is low, FCV-19 significantly predicts psychological distress (Bsimple=0.12, P < 0.01); when the impermanence level is high, the positive predictive effect of FCV-19 on psychological distress is weakened and not significant (Bsimple=0.07, P > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Moderating role of impermanence in the effect of life events on the incidence of FCV-19

Fig. 4.

Moderating role of impermanence in the influence of FCV-19 on psychological distress

Discussion

The present study elucidates the mechanism by which life events influence psychological distress in the postepidemic era. On the one hand, it delineates the relationship between life events and psychological distress. Specifically, life events impact psychological distress through the mediating effect of FCV-19. On the other hand, the anterior and latter halves of the mediation process were regulated by impermanence; impermanence weakened FCV-19 through life events and the effect of FCV-19 on psychological distress. The findings of this study have substantial theoretical implications as well as applicability to the scientific prevention and treatment of psychological distress.

As predicted by H1, this study proposes a positive prediction of postpandemic life events for psychological distress, which is consistent with previous findings and confirms the original hypothesis [27, 28, 30, 31]. The diathesis stress model holds that stress and diathesis are two important factors that cause psychological distress. Stress factors mainly refer to various stressful life events, whereas diathesis factors mainly refer to individual cognition, biological genetic characteristics, personality traits, self-esteem, etc. Individual diathesis factors lead to psychological distress under the stimulation of external stressful events [31, 60]. These findings show that in the postepidemic era, negative life events continue to exert stress that adversely affects the mental health of people of all ages and may have additional indirect effects.

This study revealed that FCV-19 completely mediated the relationship between life events and psychological distress, as anticipated by H2. An individual experiencing adverse life events in the postpandemic era will experience increased FCV-19. Similarly, FCV-19 positively affects psychological distress. That is, the psychological distress caused by individuals’ experiences of negative life events occurs because negative life events cause individuals to experience FCV-19, which in turn generates psychological distress. This conclusion can also be explained by the fear expansion parallel process model, which defines fear as a negative arousal emotion generated by overestimating the probability of dangerous situations [35]. This perception of fear may be exaggerated by fake news (or misunderstandings of COVID-19-related information) and future uncertainties during and even after the COVID-19 pandemic [2, 28, 61]. In the postepidemic era, when individuals encounter negative life events, the fear of contracting COVID-19 still positively influences their level of psychological distress.

This study revealed that impermanence moderates the impact pathway of life events on FCV-19 and the impact of FCV-19 on psychological distress. This finding is somewhat inconsistent with the initial research H3. A possible reason is that impermanence, as a cognitive factor that accepts that all phenomena are temporary and constantly changing, helps weaken the transient fear caused by negative life events. Studies have shown that impermanence can reduce the effects of daily stress on psychological distress [62]. Individuals may experience a reduction in psychological distress when impermanence comes into effect only when adverse events awaken negative emotions. Individuals may reframe stressors as opportunities for spiritual growth and lower their level of psychological distress [63]. Rather than assessing immediately upon encountering adverse events, impermanence may mitigate perceived stress, thereby reducing individuals’ levels of psychological distress. Park proposed a meaning-making model that conceptualizes the process of coping and recovery after a negative stressful event. The model argues that cognitive reappraisal can potentially reduce the stress of everyday life by fostering a more positive interpretation of challenging circumstances, thereby enhancing mental health [64]. Specifically, in the postepidemic era, impermanence can weaken FCV-19 and the psychological distress caused by adverse life events.

Cognitive reappraisal can help individuals more effectively decrease emotional experiences, reduce physiological reactions and sympathetic nervous system activation, lower amygdala activation, regulate emotions, and contribute to their physical and mental health [65, 66]. Individuals with higher impermanence scores during the initial experience of fearful emotions attenuate their emotional responses primarily by reinterpreting emotional events and modifying their personal understanding of those events. Instead of becoming trapped in fear, they experience fewer psychological issues. Studies have proven that impermanence can effectively block the impact of life events on FCV-19 and the impact of FCV-19 on psychological distress, indicating that impermanence is a protective factor against FCV-19 and psychological distress.

Limitations and Future Research

This study explored the relationships among impermanence, FCV-19, and psychological distress during life events in the postepidemic era. This study contributes to research on the mechanisms of psychological distress and provides a theoretical foundation for scientific prevention and intervention. This study has several limitations. First, the participants were mostly from one city, the sample size was relatively small, the average age was approximately 20 years, and the majority of the participants were women. Thus, it remains uncertain whether the profiles identified in this study can be generalized to other regions and individuals with different age demographics. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow causal inferences to be made about the relationships between these variables and psychological distress. Third, self-reports may be affected by social evaluation effects, and several measurement methods, such as others’ evaluations, implicit evaluations, and experimental responses, should be used to enhance validity in future research. In future research, it is pivotal to develop effective interventions to help individuals embrace the impermanence of life, which can confirm the present theoretical model and may enhance individuals’ well-being in the postepidemic era. The future prospects for cultural advancement within psychology are promising, particularly within psychotherapy, where culture emerges as an integral component and novel developmental trajectory. Subsequent research should delve deeper into the therapeutic factors embedded within culture.

Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered numerous negative psychological reactions, placing a considerable burden on public mental health. As we transition into the postpandemic era, although the direct impacts of the pandemic have somewhat diminished, psychological distress remains prevalent. Mental health professionals must excel in evaluating psychological distress, which involves not only assessing the symptoms and effects of mental health issues but also employing effective screening tools and methods to identify those who are struggling accurately. Through thorough assessments of individuals’ mental states, these experts can provide appropriate interventions and support, thereby helping alleviate the psychological burdens experienced by many individuals during this challenging period.

Likewise, even in the postpandemic era, FCV-19 has persisted. Despite the decline in direct health threats, fears and worries about potential future outbreaks or new variants continue to affect individuals. During this transition period, psychologists can help ease public fears about COVID-19 by promoting education, providing support, developing coping skills, and facilitating access to professional services, thereby helping society move more smoothly into the postpandemic era. In the postpandemic era, although many regions have begun to gradually return to normalcy, uncertainty still prevails. The pace of economic recovery is uneven, the job market remains volatile, and people’s lifestyles continue to adjust to the new normal. Moreover, the mutation of the virus and the potential for new waves of outbreaks remain concerning, making the global public health situation unpredictable. In this context, individuals and societies seek stability and continuity to address the latest challenges.

Finally, in the postpandemic era, although many regions have begun to gradually return to normalcy, uncertainty still prevails. The pace of economic recovery is uneven, the job market remains volatile, and people’s lifestyles continue to adapt to the new normal. Moreover, the mutation of the virus and the potential for new waves of outbreaks remain concerning, making the global public health situation unpredictable. In this context, individuals and societies seek stability and continuity to address new challenges. By cultivating an acceptance of impermanence, one can better face the uncertainties of life. Since change is inevitable, accepting this reality can alleviate the psychological distress that often arises from resistance to change [62]. Mental health professionals can use acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to intervene in individuals and groups experiencing psychological distress. This method helps people learn to observe their feelings and circumstances without judgment and encourages them to act according to their personal values. ACT can not only help individuals reduce the psychological distress caused by resistance to change but also promote their inner growth and adaptability, making them more resilient and confident in the face of future uncertainties [67, 68].

Conclusions

This study developed a moderated mediation model to investigate the influence of life events on psychological distress during the postepidemic era. Impermanence can effectively alleviate FCV-19 triggered by life events and mitigate the psychological distress caused by FCV-19. The findings of this study contribute to our understanding of the impact of illness on the mental health of Chinese individuals in the context of postepidemic life events.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants who contributed to the study.

Author contributions

All the authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. ZY wrote the online questionnaire program. SF and ZY collected the data. Preliminary statistical analysis was performed by ZY and discussed at SF and ZR. The structural equation model was built in SF. TZ and XH generated the tables and figures. SF and ZR wrote the first manuscript. ZL and JW wrote additional parts of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Program of the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJQN202100452) to RZJ.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in line with the ethical standards set out in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University reviewed and approved all procedures used in this study on April 9, 2021. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang YT, Liu Z, Hu S, Zhang B. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e17–8. 10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;52:102066. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergman YS, Cohen-Fridel S, Shrira A, Bodner E, Palgi Y. COVID-19 health worries and anxiety symptoms among older adults: the moderating role of ageism. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(11):1371–5. 10.1017/s1041610220001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with covid-19: cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Res ed). 2022;376:e068993. 10.1136/bmj-2021-068993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geng LN, Wang X, Xiang P, Yang J. Physiological indicators of chronic stress: hair cortisol. Adv Psychol Sci. 2015;23(10):1799–807. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin L, Liu JQ, Yang Y, Liu Y, Wang CX, Liu T, Yu X, Jia XJ. The effect of negative life events on suicidal ideation of college students: the mediating role of rumination and the moderating role of temperamental optimism. Psychol Behav Res. 2019;17(04):569–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbison CE, Allen K, Robinson M, Newnham J, Pennell C. The impact of life stress on adult depression and anxiety is dependent on gender and timing of exposure. Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29(4):1443–54. 10.1017/S0954579417000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Stressful life events, anxiety sensitivity, and internalizing symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(3):659–69. 10.1037/a0016499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aljaberi MA, Alareqe NA, Alsalahi A, Qasem MA, Noman S, Uzir MUH, Mohammed LA, Fares ZEA, Lin CY, Abdallah AM, et al. A cross-sectional study on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological outcomes: multiple indicators and multiple causes modeling. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(11):e0277368. 10.1371/journal.pone.0277368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aljaberi MA, Lee KH, Alareqe NA, Qasem MA, Alsalahi A, Abdallah AM, Noman S, Al-Tammemi AB, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Lin CY. Rasch Modeling and Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the usability of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthc (Basel Switzerland). 2022;10(10). 10.3390/healthcare10101858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Depressive vulnerability, stressful life events and episode onset of major depression: a longitudinal model. Psychol Med. 2016;46(9):1865–74. 10.1017/s0033291716000349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Zhang N, Bao G, Huang Y, Ji B, Wu Y, Liu C, Li G. Predictors of depressive symptoms in college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:196–208. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun XJ, Niu GF, You ZQ, Zhou ZK, Tang Y. Gender, negative life events and coping on different stages of depression severity: a cross-sectional study among Chinese university students. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:177–81. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu YQ, Zeng ZH, Liu SJ, Ding DQ, Zhan L. Effects of rs17110747 polymorphism of TPH-2 gene and life events on depression in college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2019;27(01):24–7. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.01.005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet (London England). 2020;395(10227):912–20. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aljaberi MA, Al-Sharafi MA, Uzir MUH, Sabah A, Ali AM, Lee K-H, Alsalahi A, Noman S, Lin CY. Psychological toll of the COVID-19 pandemic: an In-Depth exploration of anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia and the influence of Quarantine measures on Daily Life. Healthcare. 2023;11(17):2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhama K, Sharun K, Tiwari R, Dadar M, Malik YS, Singh KP, Chaicumpa W. COVID-19, an emerging coronavirus infection: advances and prospects in designing and developing vaccines, immunotherapeutics, and therapeutics. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. 2020;16(6):1232–8. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1735227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voitsidis P, Nikopoulou VA, Holeva V, Parlapani E, Sereslis K, Tsipropoulou V, Karamouzi P, Giazkoulidou A, Tsopaneli N, Diakogiannis I. The mediating role of fear of COVID-19 in the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and depression. Psychol Psychother. 2021;94(3):884–93. 10.1111/papt.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Feng H, Liu Y, Wu S, Li H, Zhang G, Yang P, Zhang K. Anxiety, depression, insomnia, and PTSD among college students after optimizing the COVID-19 response in China. J Affect Disord. 2023;337:50–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2023.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong WL, Zhang XY, Mu SK. The impact of COVID-19 infection fear on public psychological distress: the mediating role of risk perception. J Psychol. 2019;6(01):3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Peng J, Ding DQ. The relationship between coping styles and anxiety of art students in a university in Shenzhen during the novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic. Med Soc. 2021;34(11):87–92. 10.13723/j.yxysh.2021.11.018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lassale C, Batty GD, Baghdadli A, Jacka F, Sánchez-Villegas A, Kivimäki M, Akbaraly T. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(7):965–86. 10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayram N, Bilgel N. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(8):667–72. 10.1007/s00127-008-0345-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu F, Wang Y, Wang N, Ye Z, Fang S. Embracing the Ebb and Flow of Life: A Latent Profile Analysis of Impermanence and its Association with Mental Health Outcomes among Chinese University students. Mindfulness. 2023;14(9):2224–35. 10.1007/s12671-023-02213-5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernández-Campos S, Roca P, Yaden MB. The impermanence awareness and Acceptance Scale. Mindfulness. 2021;12(6):1542–54. 10.1007/s12671-021-01623-7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, Buchmann LO, Compas B, Deshields TL, Dudley MM, Fleishman S, Fulcher CD, Greenberg DB, et al. Distress management. J Natl Compr Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2013;11(2):190–209. 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncko R, Fischer S, Hatch SL, Frissa S, Goodwin L, Papadopoulos A, Cleare AJ, Hotopf M. Recurrence of Depression in relation to history of Childhood Trauma and Hair Cortisol Concentration in a community-based sample. Neuropsychobiology. 2019;78(1):48–57. 10.1159/000498920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Wang X, Yang J, Zeng P, Lei L. Body talk on Social networking sites, body surveillance, and body shame among young adults: the roles of Self-Compassion and gender. Sex Roles. 2020;82(11):731–42. 10.1007/s11199-019-01084-2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson T, Chen H. Predictors of Cosmetic surgery consideration among Young Chinese women and men. Sex Roles. 2015;73(5):214–30. 10.1007/s11199-015-0514-9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox RC, Jessup SC, Luber MJ, Olatunji BO. Pre-pandemic disgust proneness predicts increased coronavirus anxiety and safety behaviors: evidence for a diathesis-stress model. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;76:102315. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayorga NA, Shepherd JM, Garey L, Viana AG, Zvolensky MJ. Heart-focused anxiety among trauma-exposed latinx young adults: relations to General Depression, Suicidality, anxious Arousal, and social anxiety. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2022;9(4):1135–44. 10.1007/s40615-021-01054-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Assari S, Lankarani MM. Stressful life events and risk of Depression 25 years later: race and gender differences. Front Public Health. 2016;4:49. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye Y, Fan F, Chen SJ, Zhang Y, Long K, Tang KQ, Wang H. The relationship between mental resilience, negative life events and depressive symptoms: tempering effect and sensitization effect. Psychol Sci. 2014;37(06):1502–8. 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2014.06.037. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, Crockett MJ, Crum AJ, Douglas KM, Druckman JN, et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(5):460–71. 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behavior: Official Publication Soc Public Health Educ. 2000;27(5):591–615. 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):e100213. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.John OP, Gross JJ. Individual differences in emotion regulation. Handbook of emotion regulation. The Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 351–72.

- 38.Kline RB, Little TD. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Fourth Edition. In: 2015; 2015.

- 39.Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To Parcel or not to Parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct Equation Model Multidisciplinary J. 2002;9(2):151–73. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandalos DL, Finney SJ. Item parceling issues in structural equation modeling. In: 2001; 2001.

- 41.Hau K, Marsh H. The use of item parcels in structural equation modeling: non-normal data and small sample sizes. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2004;57(Pt 2):327–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11(2):213–8. 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2022;20(3):1537–45. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chi X, Chen S, Chen Y, Chen D, Yu Q, Guo T, Cao Q, Zheng X, Huang S, Hossain MM, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the fear of COVID-19 Scale among Chinese Population. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2022;20(2):1273–88. 10.1007/s11469-020-00441-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–92. 10.1097/01.Mlr.0000093487.78664.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu ZW, Yu Y, Hu M, Liu HM, Zhou L, Xiao SY. PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 for Screening Depression in Chinese Rural Elderly. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151042. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(2):163–71. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, Spitzer C, Glaesmer H, Wingenfeld K, Schneider A, Brähler E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):86–95. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo Z, Li Y, Hou Y, Zhang H, Liu X, Qian X, Jiang J, Wang Y, Liu X, Dong X, et al. Adaptation of the two-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-2) to Chinese rural population: a validation study and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;60:50–6. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24–31. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou H, Long LR. Statistical test and control method of common method deviation. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004; (06):942–50.

- 52.Abiddine FZE, Aljaberi MA, Alduais A, Lin C-Y, Vally Z, Griffiths D M. The Psychometric properties of the arabic Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2024;1:21. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling: Guilford publications. 2023.

- 54.Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. psychology; 2004.

- 55.Carlucci L, Balestrieri M, Maso E, Marini A, Conte N, Balsamo M. Psychometric properties and diagnostic accuracy of the short form of the geriatric anxiety scale (GAS-10). BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El Abiddine FZ, Aljaberi MA, Gadelrab HF, Lin C-Y, Muhammed A. Mediated effects of insomnia in the association between problematic social media use and subjective well-being among university students during COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Epidemiol. 2022;2:100030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bentler PM. Confirmatory Factor Analysis via noniterative estimation: a fast, inexpensive method. J Mark Res. 1982;19(4):417–24. 10.1177/002224378201900403. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu Y, Wen ZL. Problem packaging strategy in structural equation modeling. Adv Psychol Sci. 2011;19(12):1859–67. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple Linear regression, Multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educational Behav Stat. 2006;31(4):437–48. 10.3102/10769986031004437. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychol Bull. 1991;110(3):406–25. 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu F, Chong ESK, Wang N, Zhang X, Bian X. Resilience in the face of adversity: the role of impermanence in mitigating the effects of childhood emotional abuse and everyday stress on depressive symptoms. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2023.

- 63.Cummings JP, Pargament KI. Medicine for the Spirit: religious coping in individuals with medical conditions. Religions. 2010;1(1):28–53. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park CL. Finally, some well-deserved attention to the long-neglected dimension of religious beliefs: suggestions for greater understanding and future research. Relig Brain Behav. 2018;10:191–7. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng L, Yuan JJ, He YY, Li H. Emotional regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal over expression inhibition. Adv Psychol Sci. 2009;17(04):730–5. [Google Scholar]

- 66.SUN Y. Brain network analysis of cognitive reappraisal and expression inhibition of emotion regulation strategies: evidence from EEG and ERP. Acta Physiol Sinica. 2020;52(1):12–25. 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2020.00012. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gloster AT, Walder N, Levin ME, Twohig MP, Karekla M. The empirical status of acceptance and commitment therapy: a review of meta-analyses. J Context Behav Sci. 2020;18:181–92. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.009. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thompson EM, Destree L, Albertella L, Fontenelle LF. Internet-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: a Transdiagnostic Systematic Review and Meta-analysis for Mental Health outcomes. Behav Ther. 2021;52(2):492–507. 10.1016/j.beth.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.