Abstract

Excessive fluoride exposure beyond the tolerable limit may adversely impacts brain functionality. Betaine (BET), a trimethyl glycine, possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic functions, although the underlying mechanisms of the role of BET on fluoride-induced neurotoxicity remain unelucidated. To assess the mechanism involved in the neuro-restorative role of BET on behavioural, neurochemical, and histological changes, we employed a rat model of sodium fluoride (NaF) exposure. Animals were treated with NaF (9 mg/kg) body weight (bw) only or co-treated with BET (50 and 100 mg/kg bw) orally uninterrupted for 28 days. We obtained behavioural phenotypes in an open field, performed negative geotaxis, and a forelimb grip test, followed by oxido-inflammatory, apoptotic, and histological assessment. Behavioural endpoints indicated lessened locomotive and motor and heightened anxiety-like performance and upregulated oxidative, inflammatory, and apoptotic biomarkers in NaF-exposed rats. Co-treatment with BET significantly enhanced locomotive, motor, and anxiolytic performance, increased the antioxidant signalling mechanisms and demurred oxidative, inflammatory, and apoptotic biomarkers and histoarchitectural damage in the cerebrum and cerebellum cortices mediated by NaF. The in-silico analysis suggests that multiple hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions of BET with critical amino acid residues, including arginine (ARG380 and ARG415) in the Keap1 Kelch domain, which may disrupt Keap1-Nrf2 complex and activate Nrf2. This may account for the observed increased in the Nrf2 levels, elevated antioxidant response and enhanced anti-inflammatory response. The BET-Keap1 complex was also observed to exhibit structural stability and conformational flexibility in solvated biomolecular systems, as indicated by the thermodynamic parameters computed from the trajectories obtained from a 100 ns full atomistic molecular dynamics simulation. Therefore, BET mediates neuroprotection against NaF-induced cerebro-cerebellar damage through rats’ antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activity, which molecular interactions with Keap1-Nrf2 may drive.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40360-024-00812-z.

Keywords: Sodium fluoride, Betaine, Neurotoxicity, Oxidative stress, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics simulation

Introduction

Fluoride is a vital micronutrient with positive and negative impacts on human health. Fluoride is consumed daily in food sources (spinach, elderberry tomato, tea, and grapes) and drinking water, and it is necessary for healthy teeth and growing bones [1, 2]. Naturally, fluoride occurs as sodium fluorosilicate (Na2SiF6), fluorosilicate (H2SiF6) or sodium fluoride (NaF) in water supply and has been linked to water fluoridation [3]. Studies have shown that continuous fluoride exposure above the tolerable limit (≥ 1.5 mg/l) may occur in water fluoridation, toothpaste, and dental gel usage, causing severe health consequences including skeletal fluorosis, dental fluorosis, renal and neurological effects [2, 4–7]. Of note, overexposure to Fluoride has been associated with geothermalisation activities (volcanic eruption, mining and weathering), fluoride-containing agrochemicals, coal burning and industrial activities [8, 9]. According to Jha et al., (2011), 90% of NaF is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, above the permissive limit and linked to neurological consequences including motor and locomotive derangement, impaired memory, depression, and anxiety [10–12]. However, this effect is attributed to fluoride’s ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), impacting different brain regions and causing behaviour, molecular, and metabolic impairment [11, 13]. Neurotoxin-generated fluoride is reported to hinder mitochondria complex, altering cellular homeostasis [3]. Fluoride is associated with the alteration of biochemical processes such as oxido-inflammatory stress and apoptosis mediated by mitogen-activation protein kinase or c-jun N-terminal kinases or extracellular signal-regulated kinases (MAPK/JNK/ERK) signalling pathways in target tissues [5, 14]. NaF is associated with reduced brain glucose consumption, decreased glucose transporter 1 protein expression and glial fibrillary acidic protein, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) accumulation and TrkB reduction, increasing phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (p-ERK1/2) expression, downregulating dendritic outgrowth and expression of synaptophysin (SYN) and postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95) in vivo and in vitro [15, 16].

Betaine (trimethyl-glycine) is a nontoxic, naturally occurring nutrient present in plants (spinach, wheat bran, wheat germ) and animals (seafood and aquatic invertebrates) [17–19]. Betaine (BET) plays a vital physiologic role as an osmolyte, preventing the denaturation of cells, proteins, and enzymes from environmental stress and methyl donors crucial in the methionine hepatic and renal metabolic pathway [20]. BET possesses several pharmacological properties, including antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, anti-viral, anti-diabetes, and anti-apoptotic properties [21–24]. In addition, it exerts a therapeutic effect on liver diseases [25], acute severe ulcerative colitis [26], neuroinflammation in LPS-activated N9 microglia and amyloid-β42 oligomer (AβO) [27], cardiovascular, renal and neurodegenerative disease [26, 28, 29].

The molecular basis of the antioxidant activities of several nutraceuticals and antioxidant compounds involves the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway. Nrf-2 is a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor regulating several cytoprotective genes. The Keap1-Nrf-2–ARE pathway, an intrinsic defence mechanism against oxidative stress and inflammation, is a promising target for preventing and modifying neurodegenerative diseases [30, 31]. The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) binds, retains and targets Nrf2 for degradation in the cytoplasm via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, thereby serving as a negative regulator of Nrf-2 [32, 33]. The disruption of protein‐protein interaction (PPI) between Keap1 and Nrf-2 helps the free Nrf-2 translocate into the nucleus, which binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE). The activation of Nrf-2 is known to induce the activation of about 250 genes encoding the expression of different cytoprotective and detoxifying proteins. In the brain, these proteins provide cytoprotecting effects against neurodegenerative diseases and other pathologies through the mitigation of multiple pathogenic processes by upregulating antioxidative defence, inhibiting neuroinflammation, improving mitochondrial function, maintaining proteostasis, and inhibiting ferroptosis [34–37]. Also, Nrf-2 pathway activation has been reported to prevent caspase-3-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease [38, 39]. Nrf-2 activation can be either indirectly elicited by modifying cysteine residues in Keap1 or directly through disruption of protein‐protein interaction between Keap1 and Nrf-2. Computational tools, including molecular docking and dynamics simulation, have provided rapid and insightful screening techniques for identifying drug leads and insights into small compound molecules’ biological activities towards drug design [40]. Such methods have been applied to investigate small molecules disrupting the Keap1‐Nrf-2 interaction, activating the Keap1‐Nrf-2‐ARE signalling pathway [41]. Recently, Mili, Das, Nandakumar and Lobo [33] employed several computational techniques to identify sesamol as an activator of NRF-2 for protection against liver injury induced by the drug. The neuroprotective effect of betaine on NaF-induced neurotoxicity remains unclear. Hence, we hypothesised that BET might protect against NaF-induced neurotoxicity by activating the Nrf-2/HO1 signalling pathway. This study aimed to assess the neuroprotective effects of BET against NaF-mediated neuro-toxicities in the cerebrum and cerebellum of male Wistar rats. This study will determine BET’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activity and investigate the experimental animals’ behavioural, biochemical, and morphological changes. Furthermore, the studies will elucidate (in silico) the possible interactions of BET along the Keap1‐Nrf2‐ARE signalling pathway.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents and kits

Betaine hydrochloride (CAS: 590-46-5), Sodium fluoride (CAS: 7681-49-4), 6-Dihydroxypyrimidine-2-thiol (TBA) (CAS: 504-17-6), 6,6′-Dinitro-3,3′-dithiodibenzoic acid (DTNB) (CAS: 69-78-3), 1-Chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB) (CAS: 97-00-7), Reduced glutathione (GSH) (CAS: 70-18-8), Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (CAS: 7722-84-1), and D-hydrogen tartrate (CAS: 526-94-3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA); Epinephrine (CAS: 51-43-4) was purchased from AK Scientific, Union City, USA; Trx (Thioredoxin) ELISA Kit (E-EL-H1728), Trx-R (Thioredoxin reductase) ELISA Kit(E-EL-H1727), Nrf-2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2) ELISA Kit (E-EL-H1564), Rat HO1 (Heme Oxygenase 1) ELISA Kit (E-EL-R0488), Rat IL-10 ELISA Kit (E-EL-R0016), Rat Caspase 3 ELISA Kit (E-EL-R0160), and Rat Caspase 9 ELISA Kit (E-EL-R0163) were purchased from Elabscience Biotechnology Co. (Beijing, China).

Experimental design

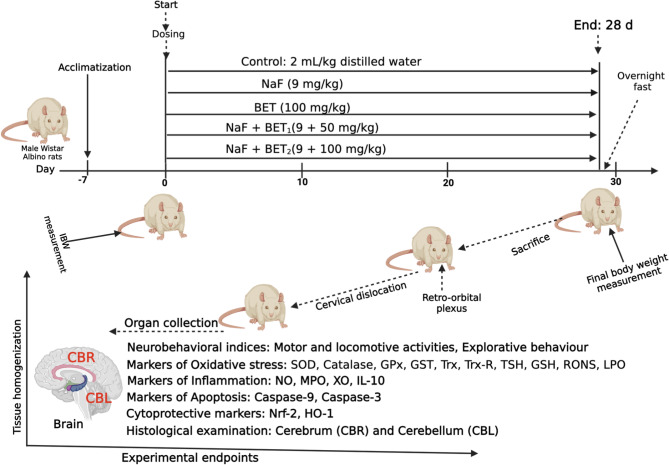

Fifty Male Wistar rats (120 ± 10 g; n = 10/rats) were used for this study. The experimental rats were obtained from the University of Ibadan Central Animal House, College of Medicine. They were housed in well-aerated cages at the Department of Biochemistry animal house facility, University of Ibadan. The experimental rats were acclimatised for 7 d and provided with rodent chows (Breedwell Feeds Limited) and tap water freely under 12 h day/night daily circadian period. The experimental design was approved by the Care and Use Research Ethics Committee (ACUREC) at the University of Ibadan Animal (UI-ACUREC/057-1222/11). In addition, the 3Rs (replacement, reduction, and refinement) guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals were adopted in this study [42]. Although a sample size of 125 was estimated for the study using the G* Power software version 3.1.9.4 [43]. Since reduction implies using a smaller number of animals as possible, we then reduced the number of experimental rats to 50 animals. The experimental rats were randomly distributed into five groups (n = 8 rats each) immediately after the acclimatisation period. They were treated orally with the co-treatment interval of 1 h uninterrupted for 28 days, as in illustrated Fig. 1 and depicted below:

Fig. 1.

Outlines of the experimental timeline to investigate the effect of Betaine (BET) on fluoride rats Albino Wistar strain for 28 consecutive days (A). Created by Arunsi Uche O. using BioRender, https://app.biorender.com/

Group 1

Control received distilled water (2 mL/kg)

Group 2

Sodium Fluoride treated rats (NaF) alone received sodium fluoride (9 mg/kg. bw., p.o)

Group 3

Betaine chloride (BET) received BET (100 mg/ kg. bw, p.o) alone

Group 4

NaF + BET1 – received NaF (9 mg/kg) + BET (50 mg/kg)

Group 5

NaF + BET2 received NaF (9 mg/kg) + BET (100 mg/kg)

The effective doses of NaF (9 mg/kg) and BET (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) were utilised in this study following previous literature [44–47].

Evaluation of experimental animal behaviour and explorative characteristics

Behaviour and exploratory characteristics and motor fitness were assessed using various behavioural models, including open field test, negative geotaxis, and forelimb grip test. An open field test box (100 × 100 × 60 cm) was used to assess rats’ behaviour and exploratory characteristics in each group on day 28 to minimise any confounding stressful situation on the experimental rats. Each rat was placed at the centre of the box and allowed to explore freely for 5 min after removing the olfactory cue using 70% ethanol after each trial. The locomotive and exploratory activities of each experimental animal, namely, heat maps, track plots, maximum speed, path efficiency, total freezing time, absolute turn angle, and total distance travelled data, were obtained using video track software (ANY-maze, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) to analyse pre-recorded, overhead webcam videotapes (Free 2x, Manufacturer, City and Country). Moreover, we determined the panicogenic behaviour of rats by assessing urination frequency and faecal bolus discharge on the open field test [48–50]. Using a negative geotaxis test, the motor fitness of rats was determined by estimating the time spent reorienting the experimental rats on the inclined plane. Each rat was kept on a 45° inclined plane of a rough surface wooden platform (12.5 × 45 cm w × h), and the mean time to rotate (180° re-orientation) was recorded [49]. Using the forelimb grip test, we also evaluated the neuromuscular function as the maximal muscle strength of each animal’s forelimb gripping [51, 52].

Tissue sample collection and biochemical assay

The rats were euthanised by cervical dislocation and carbon dioxide (CO2) asphyxiation on day 29 in an overnight fasted state. The brains of experimental rats were removed and dissected to isolate the cerebrum and cerebellar cortices and immediately homogenised in cold sodium phosphate buffer solution (0.05 M, pH 7.4). The homogenate of tissue samples was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min (4 °C) to obtain cerebrum and cerebellar supernatant and were stored at -20 °C for analysis for biochemical assays (n = 6 rats/group) for non-ELISA and (n = 3 rats/group) for ELISA, such as cerebrum and cerebellar antioxidants, inflammation, and apoptotic biomarkers.

Assessment of rats’ antioxidant status

The activity of rats’ cerebrum and cerebellar antioxidants was evaluated in supernatant. The Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity [53] was assessed. Briefly, in a cuvette, 2.5 mL of carbonate buffer (0.05 M, pH 10.2) was added to 50 µL of sample or standard, and then 0.3 mL of epinephrine was added. The change in absorbance was recorded at 480 nm every 30 s for 2 min. Catalase (CAT) activity was examined using the Clairborne method [54]. 2.95 mL phosphate buffered hydrogen peroxide and 50 µL of sample or standard were added to a cuvette and gently inverted to mix and read at 240 nm absorbance for 5 min. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) activity evaluation was in line with earlier reports by Habig et al. [55]. Ten µL of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB), 170 µL of the reaction mixture and 20 µL of samples or standard were mixed and read at 340 nm absorbance for 3 min every 30 s. According to established protocol, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity was determined following Rotruck’s method [56]. The total sulfhydryl (TSH) level was evaluated by procedure in line with Ellman’s method [57]. The reduced glutathione (GSH) level was estimated using the standard procedure of Jollow et al. [58]. The level of hemeoxygenase 1 (HO-1), Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), thioredoxin (Trx), thioredoxin reductase Trx-R, biomarker of oxidative stress and transcription response factors were analysed using ELISA kits method specified by manufacturer protocol.

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) was evaluated in line with the established method of Okhawa et al. [59]. Briefly, a mixture of 40 µL of cerebrum and cerebellum supernatant sample, 160 µL of Tris-KCl buffer, 50 µL of 30% TCA, and 50 µL of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) incubated for 45 min at 80 ℃, cooled and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min. Then, the absorbance was read at 532 nm using 200 µL of the clear supernatant. The reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) level was quantified in line with the method described by Owumi and Dim [60].

Evaluation of inflammation and apoptotic biomarkers

Nitric oxide (NO) levels of the samples were estimated using the methods of Green et al. [61]. Briefly, equal volumes of Griess’ reagent and cerebra and cerebellar samples were incubated quickly for 15 min, after which the absorbance of the mixture was read at 540 nm. The total nitrite level was calculated from the absorbance obtained from a standard solution, and the results were expressed in units per mg protein. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was analysed as previously described by Granell et al.. and earlier reported [62]. All readings were measured with a SpectraMax™ 384 multimodal plate reader. Tissue concentration of anti-inflammatory indices interleukin 10 (IL-10) and apoptosis (caspases 3 & 9) were analysed using ELISA kits specified by the manufacturer protocol.

Microscopic histopathological and histomorphometry assessment

At the study’s end, the histopathological examination rats were euthanised, perfused cardiac perfusion using normal saline, and post-fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin. The fixed brain tissues were processed through the stages of fixation, dehydration, clearing, infiltration, embedding and staining to obtain paraffin wax-embedded tissue blocks, which were then sectioned in the coronal plane using a rotary microtome (Leica, Germany). The sectioned brain tissues (5 μm) were transferred to pre-charged slides and stained in Haematoxylin and Eosin following the established protocol [63] to demonstrate general histology of the rat cerebellum and the prefrontal cortex. After that, slides were viewed using a Leica DM 500 digital light microscope (Germany) and images were captured with a Leica ICC50 E digital camera (Germany). Histomorphometry analyses were done using Image J software computerised image analyser. Using an objective lens (x 40) and an ocular lens (x 10), the viable and pyknotic neurons of the cerebellum and cerebral cortex were observed and then counted as circular, cytoplasmic membrane-intact cells devoid of pyknotic spots. Viable neurons are identified by their dispersed chromatin, distinct nucleoli and absence of neuronal cell death. Neurons with pyknosis were also counted separately. According to the method described by Taveira et al. [64], was calculated for ten different areas of the cerebellum and cerebral cortex slides in each experimental group. Employing the technique of Taveira et al. [64], the pyknotic index (PI) was calculated using the equation: PI = pyknotic neurons / total neurons x 100.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained in this study (Table S1 and S2) are expressed as means ± SEM and analysed using one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism version 10.0 for MacOS CA, USA). The statistically significant level was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. NaF-induced rats, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001 vs. control.

Molecular docking

Based on the in vivo results, in silico analysis comprising molecular docking was carried out to explore the interactions of betaine with Nrf-2 and caspase-3. Structures of betaine and reference compounds were downloaded from the PubChem compound database (www.pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) as Structure data format (SDF) files. The SDF files of the ligands were then converted to mol2 chemical format using Open Babel [65]. The Gasteiger-type polar hydrogen charges were assigned to the atoms in the structures, while the non-polar hydrogen atoms were merged with the carbons [66]. Finally, the structure files were converted to the PDBQT format dockable in AutoDock Tools. The Structure of human keap1 kelch domain co-crystalised with IVX (PDBID: 4L7D), rat Keap-1 kelch domain (PDBID: 7OFE), human Keap1 Kelch domain- Nrf-2 fragment complex (PDBID: 2FLU), and human caspase-3 protein co-crystalised (PDBID: 1GFW) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org). From the downloaded crystal structures, the native inhibitors were extracted, and water molecules were removed [67]. AutoDock version 4.2 programs were then used to add hydrogen atoms to the structures. The structures of betaine and the native compounds were imported into AutoDock Vina and incorporated in PyRx 0.8. The structures were minimised through Open Babel using the Universal Force Field (UFF) as the energy minimisation parameter and conjugate gradient descent as the optimisation algorithm. The small molecule compounds were then docked against the binding/active sites of the proteins. The binding/active sites were each defined by the grid boxes depicted in Table 1. The docking was performed with other parameters kept as default. Subsequently, visual inspection was performed on the various docked poses using Discovery Studio Visualizer version 16.

Table 1.

Grid box information of the binding sites of receptor proteins

| Dimensions | rKeap1 | hKeap1 | hKeap1-Nrf2 | hCaspase-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center_x | -39.57 | -26.06 | 7.38 | 30.47 |

| Center_y | 18.89 | 39.59 | 11.50 | 36.30 |

| Center_z | -6.89 | -37.22 | 1.62 | 32.42 |

| Size x | 28.55 | 28.89 | 31.19 | 25.00 |

| Size y | 26.13 | 17.46 | 34.49 | 22.94 |

| Size z | 28.19 | 27.29 | 35.43 | 25.00 |

Molecular dynamics simulation

The CHARMM-GUI website was employed to prepare the apo Keap1 and ligand-Keap 1 complexes for molecular dynamic (MD) simulation [68–71]. The biomolecular systems were prepared using the 3-point (TIP3P) water model in a cubic water box. 0.154 M Sodium Chloride ions were added to neutralise the biomolecular systems. Water molecules and amino acids in the Keap1 kelch domain are parameterised using the CHARMM36m force field. Betaine and other ligands were parameterised by applying the CHARMM general force field (CGenFF). The GROMACS 2020.3 software [72] was used as the simulation package for simulating the application of 3-D periodic boundary conditions (PBC). Energy minimisation was performed using the steepest descent algorithm with the minimisation step set at 100,000. Each system was equilibrated to 310 K using an NVT ensemble through the Velocity rescale method [73]. The Berendsen barostat was used to set and maintain pressure at 1 atm. Then, a 100 ns MD simulation production run was performed. For each 0.1 ns, a structural frame was recorded. After the MD run, the PBC was removed using the trjconv script and the trajectories were computed. The thermodynamic parameters were calculated with a script written in tcl and implemented in the Visualising Molecular Dynamics TK console [74].

Results

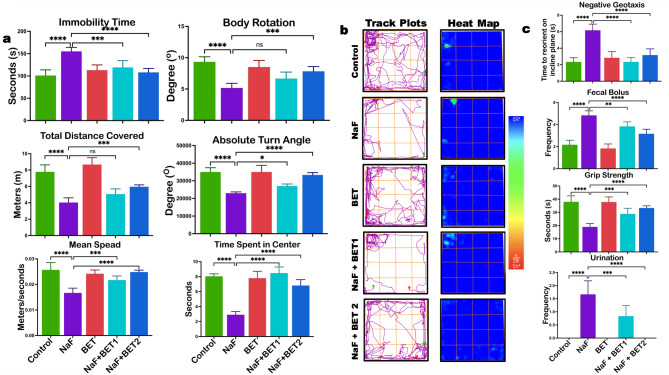

Influence of betaine on impairment of exploratory and locomotor behaviour in rats

Betaine’s locomotor and exploratory effects on NaF-exposed rats are shown in Fig. 2a—b. NaF alone treated rats showed (p < 0.05) reduction in locomotor behaviour as evidenced by decreased absolute turn (F (4, 25) = 36.14, P < 0.0001) body rotation (F (4, 25) = 20.06, P < 0.0001) total distance travelled (F (4, 25) = 49.18, P < 0.0001) maximum speed F (4, 25) = 23.17, P < 0.0001) and reduced time mobile F (4, 25) = 19.55, P < 0.0001) compared to control. In addition, the NaF-alone exposed group showed dysregulated exploratory competencies, as evidenced by reduced track plot density and heat map intensity. However, the BET co-treated group cohort demonstrated improved locomotor and exploratory behaviour compared to the NaF-alone group.

Fig. 2.

a-c The effect of BET on NaF-induced locomotive decline and explorative behaviour (a); representative rack plot and heat map (b); and anxiety-like behaviour and motor dysfunction (c) in male Wistar rats experimentally treated with BET and NaF for 28 consecutive days. All values represent the mean (n = 6; ± SEM). The statistics were analysed using GraphPad Prism V.10.2 for MacOS. The tests used were one-way ANOVA and Tukey Post Hoc. The designated P-values for all tests were set at p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), and < 0.0001 (****). BET betaine, NaF Sodium fluoride

Betaine abates sodium fluoride-induced anxiogenic‐like behaviour and motor activity decline in experimental rats

The effect of BET on panicogenic-like behaviour and motor activity of Rats treated with NaF are presented in Fig. 2C. Experimental rats exposed to NaF-alone displayed panicogenic-like behaviour, characterised by frequent urination F (4, 25) = 38.46, P < 0.0001), discharge of faecal bolus (F (4, 25) = 44.69, P < 0.0001) and decreased time spent in the centre on OFT (F (4, 25) = 63.02, P < 0.0001) relative to the control cohort group. Also, the motor activity was lesser in the NaF-alone exposed rats, as evidenced by a decrease (p < 0.5) in time to reorient on negative geotaxis (F (4, 25) = 34.59, P < 0.0001) and in grip strength on the forelimb grip test (F (4, 25) = 29.65, P < 0.0001) compared to the control group. On the other hand, co-administration of BET reversed NaF-induced anxiogenic‐like behaviour and motor activity decline indicated by a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in urination frequency, faecal bolus discharge, with an increase in time spent in the centre on OFT, time to reorient on negative geotaxis and improvement in grip strength on forelimb grip test when compared to NaF-alone group.

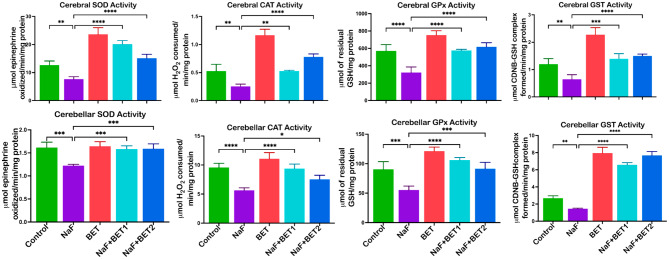

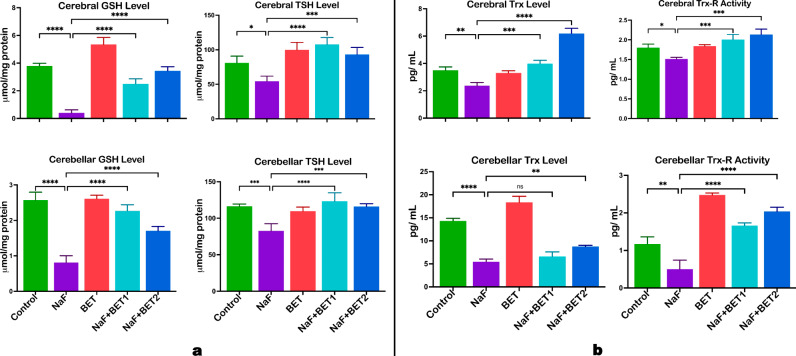

Effect of betaine on cerebral and cerebellar antioxidant status in experimental rats

Figure 3 shows the effect of BET on antioxidant status in sodium fluoride-exposed rats. In the analysis, NaF-induced rats observed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) enzymatic antioxidants activities SOD (F (4, 15) = 64.37, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 15.29, P < 0.0001) CAT (F (4, 15) = 78.28, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 29.74, P < 0.0001), GPx (F (4, 15) = 34.03, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 30.76, P < 0.0001), and GST (F (4, 15) = 219.6, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 219.6, P < 0.0001), and non-enzymatic antioxidants GSH (F (4, 15) = 130.2, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 79.77, P < 0.0001), TSH (F (4, 15) = 19.18, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 17.08, P < 0.0001) levels (Fig. 4a) when compared to the control. In contrast, BET co-administered cohort (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) showed a (p < 0.05) increase in the enzymatic antioxidants’ activities SOD, CAT, GPx, and nonenzymatic antioxidants GST, GSH and TSH levels of the cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) relative to NaF-induced animals.

Fig. 3.

The effect of BET in the cerebrum and cerebellum SOD, CAT, GPx and GST activities of rats experimentally challenged with NaF for 28 consecutive days. All value represents the mean (n = 4; ± SEM). The statistics were analysed using GraphPad Prism V.10.2 for MacOS. The tests used were one-way ANOVA and Tukey Post Hoc. The designated P-values for all tests were set at p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), and < 0.0001 (****). BET betaine, NaF Sodium fluoride; SOD Superoxide dismutase; CAT Catalase; GPx Glutathione peroxidase, and GST Glutathione-S-transferase

Fig. 4.

The effect of BET on GSH, TSH (a) and Trx, Trx-R and activity (b) against NaF-induced antioxidant decline in the cerebrum and cerebellum of rats experimentally treated for 28 consecutive days. All value represents the mean (n = 4; ± SEM). The statistics were analysed using GraphPad Prism V.10.2 for MacOS. The tests used were one-way ANOVA and Tukey Post Hoc. The designated P-values for all tests were set at p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), and < 0.0001 (****). BET betaine, NaF Sodium fluoride; GSH Glutathione; GST Glutathione S-transferase; Trx Thioredoxin, Trx-R Thioredoxin reductase, and TSH Total sulfhydryl group

Influence of betaine on the experimental rats’ cerebral and cerebellar redox-active system

Figure 4B demonstrates the outcome of BET on the cerebrum and cerebellum redox-active proteins such as thioredoxin (Trx) and thioredoxin reductase (Trx-R). NaF-induced animals had a (p < 0.05) decrease in the activities of cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) Trx (F (4, 10) = 88.81, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 132.0, P < 0.0001) and Trx-R (F (4, 10) = 17.64, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 77.18, P < 0.0001) when relative to control. On the other hand, animals treated with BET (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) significantly increased the cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) activity of redox-active protein as indicated by an increase in Trx and Trx-R activity when compared with NaF-induced rats.

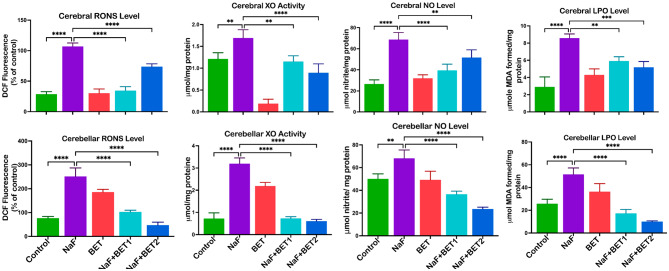

Influence of betaine on cerebral and cerebellar oxidative stress in experimental rats

Figure 5 depicts the outcome of BET on the cerebrum and cerebellum oxidative stress. Experimental rats treated with NaF alone had an increase (p < 0.05) in cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) markers of oxidative stress, including RONS (F (4, 15) = 145.2, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 83.65, P < 0.0001), XO (F (4, 15) = 47.54, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 222.6, P < 0.0001), NO (F (4, 15) = 35.78, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 40.03, P < 0.0001) and LPO (F (4, 15) = 32.40, P < 0.0001 F (4, 15) = 49.28, P < 0.0001), when compared with control. On the other hand, BET co-treated groups reversed cerebral and cerebellar oxidative stress, indicated by a significant decrease in the cerebral and cerebellar RONS, LPO and XO levels when compared to NaF-alone treated animals.

Fig. 5.

The effect of BET on RONS, XO (activities), NO, and LPO levels on NaF-induced oxidative stress in the cerebrum and cerebellum of rats experimentally treated for 28 consecutive days. All value represents the mean (n = 4; ± SEM). The statistics were analysed using GraphPad Prism V.10.2 for MacOS. The tests used were one-way ANOVA and Tukey Post Hoc. The designated P-values for all tests were set at p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), and < 0.0001 (****). BET betaine, NaF Sodium fluoride; RONS Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species; XO Xanthine oxidase; NO nitric oxide; and LPO Lipid peroxidation

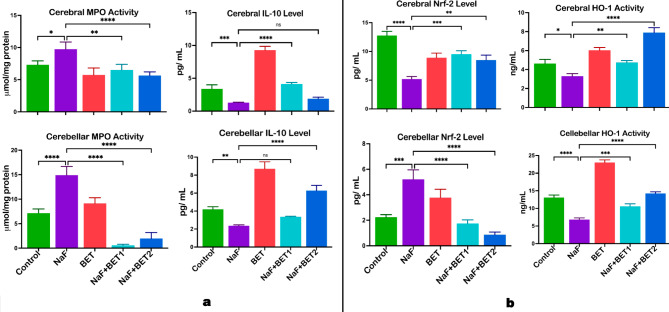

Influence of betaine on cerebral and cerebellar inflammatory responses in experimental rats

Figure 6A shows the consequences of BET on the cerebrum and cerebellum pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers. NaF-induced animals had a higher (p < 0.05) cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) pro-inflammatory response, myeloperoxidase (MPO) level (F (4, 15) = 14.48, P < 0.0001; F (4, 15) = 99.32, P < 0.0001), and a (p < 0.05) lower anti-inflammatory cytokines interleukin 10 (IL-10) (F (4, 10) = 180.8; P < 0.0001, F (4, 10) = 90.80, P < 0.0001) when compared with control. On the contrary, animals treated with BET (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) significantly lowered cerebral and cerebellar inflammatory markers. In comparison, animals treated with the lower dose of BET (50 mg/kg) showed a (p < 0.05) increase in cerebral anti-inflammatory cytokines and animals treated with the higher dose of BET (50 mg/kg) only showed a (p < 0.05) increase in cerebellar IL-10 level when compared with NaF-induced rats.

Fig. 6.

The effect of BET on NaF-induced elevated proinflammation MPO, IL-10 (a), and signalling biomarkers Nrf-2 and HO-1 (b) in the cerebrum and cerebellum of rats experimentally treated for 28 consecutive days. All value represents the mean (n = 4; ± SEM). The statistics were analysed using GraphPad Prism V.10.2 for MacOS. The tests used were one-way ANOVA and Tukey Post Hoc. The designated P-values for all tests were set at p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), and < 0.0001 (****). BET betaine, NaF Sodium fluoride; MPO Myeloperoxidase; IL-10 Interleukin-10; Nrf-2 Nuclear erythroid factor-2; and HO-1 Hemeoxygenase-1

Influence of betaine on cerebral and cerebellar cytoprotective signalling molecules in experimental rats

Figure 6B demonstrates the outcome of BET on the cerebrum and cerebellum cytoprotective signalling molecules such as nuclear factor-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) and heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1). NaF alone treated animals had a decrease (p < 0.05) in the activities of cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) Nrf-2 (F (4, 10) = 43.76, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 39.32, P < 0.0001) and HO-1 (F (4, 10) = 67.10, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 270.4, P < 0.0001) when compared with control. On the other hand, animals treated with BET (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) significantly increased the cerebral and cerebellar activity of antioxidant response molecules as indicated by an upregulated Nrf-2 and HO-1 activity compared with NaF-induced rats.

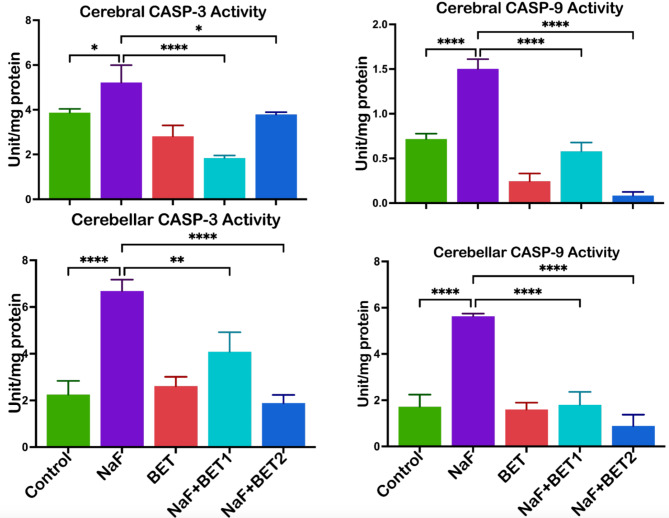

Influence of betaine on cerebral and cerebellar apoptotic responses in experimental rats

Figure 7 shows the consequences of BET on the cerebrum and cerebellum apoptotic responses in caspases 3 and 9. NaF-induced animals had higher (p < 0.05) cerebral (upper panel) and cerebellar (lower panel) apoptotic responses to caspases 3 (F (4, 10) = 26.80, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 37.21, P < 0.0001) and caspases 9 (F (4, 10) = 131.6, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 57.68, P < 0.0001) when compared with the control. On the other hand, animals treated with BET (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg) significantly lowered cerebral and cerebellar apoptotic responses, indicated by a decrease in caspases 3 and caspases 9 activity when compared with NaF-induced rats.

Fig. 7.

The effect of BET on NaF-induced increases in apoptotic biomarkers (caspases − 3 and − 9) activities in the cerebrum and cerebellum of rats experimentally treated for 28 consecutive days. All value represents the mean (n = 4; ± SEM). The statistics were analysed using GraphPad Prism V.10.2 for MacOS. The tests used were one-way ANOVA and Tukey Post Hoc. The designated P-values for all tests were set at p < 0.05 (*), < 0.01 (**), < 0.001 (***), and < 0.0001 (****). BET betaine, NaF Sodium fluoride; CASP-3 Caspase-3; CASP-9 Caspase-9

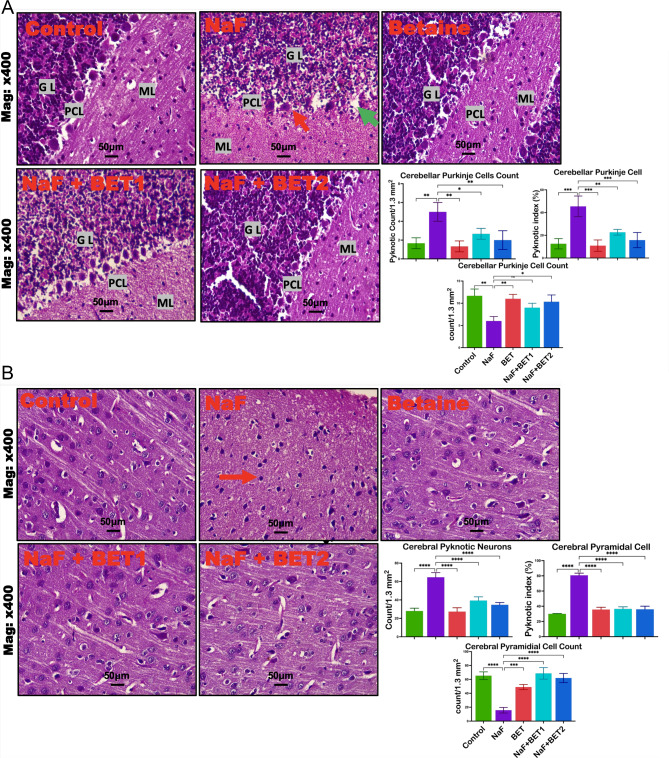

Effect of betaine on cerebral and cerebellar histomorphometry and histological modifications upon treatment with NaF

The effect of Betaine on the NaF-exposed rats’ brain sections is presented in the photomicrograph in Fig. 8A-B. The control and BET-alone exposed group of the cerebrum and cerebellum showed normal cerebral cortex, unperturbed neurons, healthy hippocampal region, and glial cells. At the same time, the NaF-alone group revealed damaged neurons, a distorted cerebral cortex of pyramidal cells, and reduced cerebellum Purkinje cell indicated by reduced pyramidal and Purkinje cell count (F (4, 10) = 41.09, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 9.826, P = 0.0017), elevated pyknosis cell (F (4, 10) = 47.15, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 10.72, P = 0.0012) and pyknotic index (F (4, 10) = 156.5, P < 0.0001; F (4, 10) = 16.75, P = 0.0002) in the cerebral and cerebellar cortices. Meanwhile, the cerebral and cerebellar injuries of the rats treated with NaF alone were dose-dependently improved in the groups of experimental rats co-treated with BET at both doses.

Fig. 8.

A-B Representative histological changes in the cerebellar cortex and representative histomorphometry of experimental rats treated with NaF and BET (A). The control group showed the typical architecture of the cerebellar layers (Molecular layer (ML), Purkinje cell layer (PCL), and Granule layer (GL) with their cells intact. The NaF-treated group (NaF) showed severe Purkinje cell loss in the PCL and pyknosis of neurons, signifying neuronal death in the PCL (Red arrowhead). Betaine group only (BET) showed typical architecture of the cerebellar cortex. Meanwhile, the NaF + BET1 and NaF + BET2 groups showed some restoration of the damaged Purkinje cells. B: Histological changes in the cerebellum and histomorphometry of experimental rats treated with NaF and BET (B). The control group (CNT) shows the typical architecture of the pyramidal layer of the cerebral cortex, with its cells intact. The treated group (NaF) showed severe loss of the pyramidal neurons and pyknosis of surviving neurons (Red arrowhead). Betaine group only (BET) showed typical architecture of the cerebellar cortex. Meanwhile, the NaF + BET1 and NaF + BET2 groups showed some restoration of the damaged pyramidal cells. All value represents the mean (n = 3; ± SEM). The statistics were analysed using GraphPad Prism V.10.2 for MacOS. The tests used were one-way ANOVA and Tukey Post Hoc. The designated P-values for all tests were set at < 0.05 (*) vs. control. Normal cells (dark arrowhead), pyknotic cell red (arrow) indicating shrunken or degenerated neuronal cells. H and E Stain, x 400 magnification, scale bar: 50 μm

The binding affinity of betaine with Keap1 Kelch domain and Caspase-3

Betaine exhibited high binding affinity with rat Keap-1 kelch, human Keap1 Kelch, Keap1-Nrf-2 complex and caspase-3 but with scores lower than those of the native compounds, as shown in Table 2. The interactions of betaine with the receptor proteins were comparable to those of the co-crystalised compounds.

Table 2.

Binding affinity scores and amino acid interactions of betaine with Keap1 and caspase-3

| Ligands | Protein | Binding Score (Kcal/mol) |

Hydrogen bond (bond length) | Hydrophobic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Interacted residues | No | Interacted residues | |||

| 1VX | rKeap1 | -8.6 | 4 | ARG 415(4) (2.79, 2.15,2.59, 2.52) | 4 | TYR 334, TYR 525, TYR 572, ALA 556 |

| Betaine | -6.6 | 8 | ARG 415(2)(2.19, 2.27) VAL 463(2)92.55,2.41), GLY 462(3.49), GLY 509(3.67), LEU365(3.53), VAL 604(3.55) | 1 | ALA 366 | |

| 1VX | hkeap-1 | -9.6 | 0 | Nil | 8 | ARG 415(3), ALA556(3) TYR 525, TYR 334 |

| Betaine | -5.7 | 2 | ASN 414(1.91) ARG 380(3.50), | 3 | ALA 556, TYR 334, TYR 572 | |

| 1vx | hKeap1-Nrf2 | -7.0 | 2 | ARG 380(2.05), ASP77 (1.94), | 3 | HIS 436, LEU 84, PHE 478 |

| Betaine | -4.3 | 7 | ARG 415(2.10), GLY 462(3.54), GLY 509(3.59), LEU 365(3.59), ILE 416(3.57), LEU 365(3.48), VAL 604(3.61) | 4 |

ALA 556 THR 80 GLY 364 LEU 557 |

|

| MSI | hCaspase 3 | -5.4 | 4 |

THR62 (2.71) ARG64 (2.65) SER65 (2.12) GLN161 (2.39) |

3 |

HIS121 (4.65) ARG64 (2) (4.01, 4.46) |

| Betaine | -4.3 | 5 |

ARG64 (2) (1.84,1.80) HIS121 (2) (2.11, 3.50) CYS163 (2.57) |

0 | Nil | |

Critical amino acid residues are in Bold font

Molecular interactions of betaine with Keap1-Nrf-2 and caspase-3

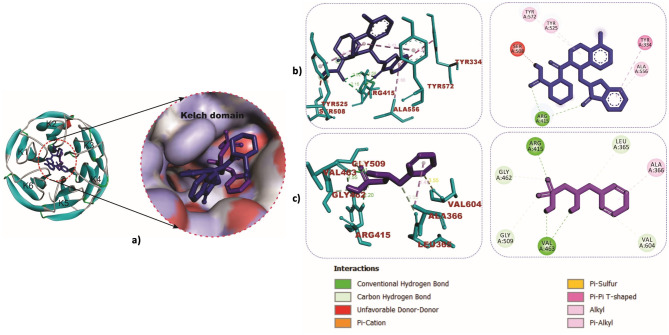

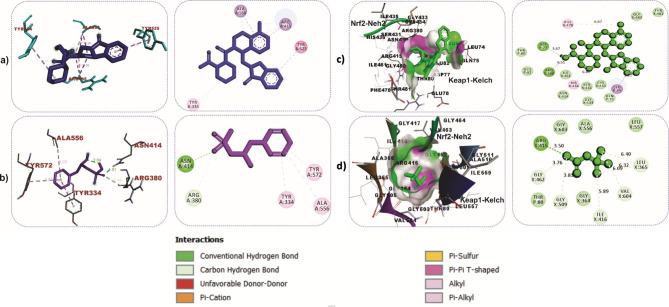

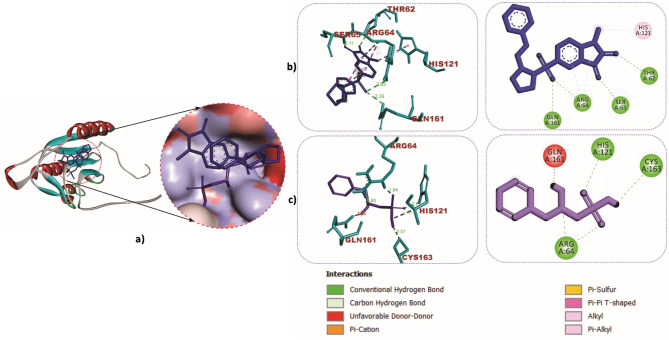

The cartoon view, as well as surface views of the molecular interactions of betaine (purple colour) and IVX (blue colour) in the inhibitor binding pocket within the Kelch domain of Keap-1 protein, is depicted in Table 2; Fig. 9a. Binding of betaine to rat Keap1 featured more hydrogen bonds than the IVX as illustrated in Table 2; Fig. 9b and c. Similar observations were recorded in the binding interactions of betaine to human Keap-1, as shown in Fig. 10a and b. The role of hydrogen bonds in the interactions of betaine with Keap-1 protein was more apparent when betaine was docked into the Keap1-Nrf-2 complex, as shown in Table 2; Fig. 10c and d. Additionally, we investigated the interactions of BET with the active site of caspase-3, which revealed strong hydrogen bonds with critical amino acid residues that define the active site of the enzyme (Table 2; Fig. 11a-c).

Fig. 9.

Molecular interactions of betaine (purple) and IVX (blue) in the inhibitor binding pocket within the Kelch domain of rat Keap-1. a Cartoon and surface views (b) 3D and 2D interactions view of IVX (c) 3D and 2D interactions of BET

Fig. 10.

3D and 2D interactions of ligands with Kelch domain of human Keap-1. Keap1-BET complex (a and b). Keap1-Nrf2-BET complex (c and d)

Fig. 11.

Molecular interactions of betaine (purple) and MSI (blue) in the active site of Caspase-3. a Cartoon and surface views (b) Caspase-3- MSI (c) Caspase-3-BET complex

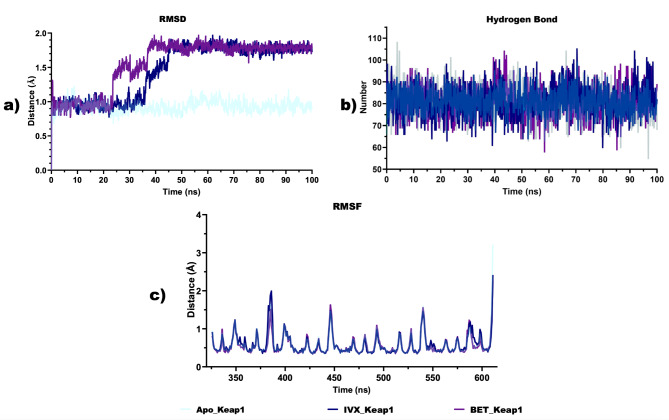

Structural stability and conformational flexibility of BET-Keap1 complex

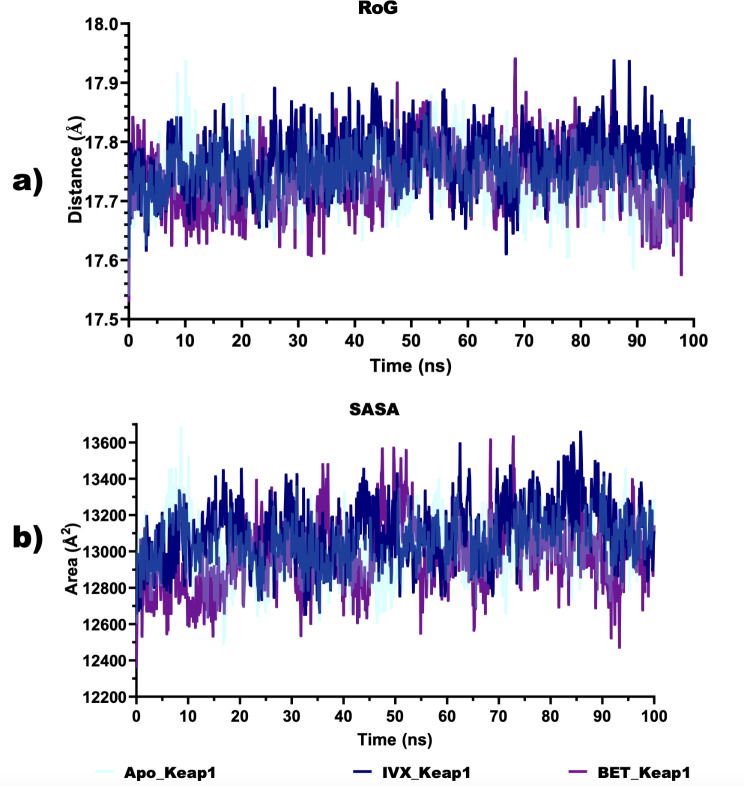

Based on the multiple hydrogen bonds observed between BET and critical amino acid residues, a 100 ns full atomistic MD simulation was conducted. The various thermodynamic parameters computed from the trajectories obtained from the 100 ns MD simulation are depicted in Figs. 12 and 13. The plot of the RMSD (Fig. 12a) revealed that the RMSD values of apoKeap1 showed a rising trend in the first 12 ns and then stabilised at an average value of 0.93 Å. In the Keap1-ligand complexes, an increasing trend was also observed in the RMSD values, stabilising for 25ns and then showing a large fluctuation. The RMSD stabilised again at 40ns, around an average value of 1.8 Å in the BET-Keap1 complex and at 45ns, around 1.8 Å in the case of the IVX-Keap1 complex. The average number of hydrogen bonds in apo Keap1, IVX-Keap1 and BET-Keap1 biomolecular systems are all comparable with 81 each (Fig. 12b). The RMSF plot (Fig. 12c) showed that ligand-protein complexes showed several peaks with the most considerable fluctuations around residues 380–388. Figure 13a shows that the values RoG of the apoKeap1 and those of the complexes were maintained within 2 Å. The average values for apoKeap1, BET-Keap1 and IVX-Keap1 are 17.74 Å, 17.74 Å, and 17.77 Å, respectively. The SASA values depicted in Fig. 13b showed that the average values for apoKeap1, BET-Keap1 and IVX-Keap1 are 13,013 Å2, 12,975 Å2 and 13098Å2.

Fig. 12.

Structural stability and conformational flexibility ligand-protein complexes (a) Backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) plots. b Total number of hydrogen bonds (c) Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF)

Fig. 13.

Unfolding deviation of ligand-protein complexes. a Radius of gyration (b) Surface accessible surface area

Discussion

Exposure to fluoride at a permissible limit is required for dental health. However, fluoride toxicity occurs above this limit, which triggers free radicals’ generation, inflammation, apoptosis, and cellular tissue damage [2]. Fluoride-induced toxicity triggers several mechanisms attributed to inhibition of proteins, organelle disruption, altered pH, and electrolyte imbalance [2]. Previous studies have reported that fluoride affects the brain by promoting the generation of inflammatory factors, microglial activation, and altering cellular energy and neurotransmitter metabolism [13]. Fluoride crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [16, 75, 76], promoting pro-oxidation by increasing the synthesis of reactive oxygen species ROS (O2−, H2O2, and OH−) [77], downregulation of endogenous antioxidants enzyme [14, 78], enhancing neuroinflammation by stimulating the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, TGF-β, and IFN-γ) [79, 80] and increasing proapoptotic proteins (p53, FAS, Cytochrome-c and BAX) and decreasing proteins that mediate anti-apoptosis (Bcl-2) [81–83]. Fluoride has also been reported to induce neuronal loss, promoting neurologic disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, among others [84]. The preceding studies have demonstrated the neurotoxic effect of NaF. This current study elucidates the mechanism involved in the neuroprotective effect of BET against NaF-induced neurotoxicity. The current study showed incompetence in spatial and exploratory behaviour as demonstrated by a drastic reduction in absolute turn, body rotation, total distance travelled, maximum speed time mobile, grip strength, track plots and higher heat maps intensity in NaF-induced animals, indicating a significant decline in motor, locomotive and explorative activities. Our findings agree with earlier literature, according to Sarro [52], animals exposed to stressors developed frequent urination and discharge of faecal bolus, demonstrating panicogenic behaviour and motor abnormalities on exposure to fluoride. Following exposure of rats to NaF treatment, anxiety-like behaviour and depression have been reported [11]. Interestingly, both doses of BET successfully restored the motor and locomotor behaviour compared with NaF-induced animals. Our data demonstrated that BET improved anxiolytic behaviour by significantly decreasing the anxiogenic phenotype, which is indicated by reduced frequent urination, faecal bolus discharge, freezing, and negative geotaxis. This correlates with previous studies that revealed that improved locomotive activities of organisms determine their exploratory behaviour and are essential for animal survival [85, 86]. Of note, exposure to stressors or neurotoxins may present anxiety behaviour presented as escape or avoidance, aggression, freezing or immobility and submissive behaviour [87, 88].

The study further measured the neuroprotective efficacy of BET by conducting multiple biochemical assays to investigate the antioxidant capacity and anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of BET against NaF-induced cerebrum and cerebellum toxicities in rats. The existing hypothesis has well-documented antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic properties of BET in a rat model of neurotoxicity, including behavioural impairments induced by ischemia, toxins, and stress, such as seizures, depressive-like symptoms, motor dysfunction, and memory deficits [89]. Prior studies have looked at the mechanism involved in the disrupting effect of the brain, including fluoride-induced generation of free radicals and a decline in endogenous antioxidative [77, 90]. Our current study demonstrated that fluoride-exposed rats showed compromised antioxidant enzymes revealed by a tremendous reduction in the cerebrum and cerebellum GST, GPx, SOD, and CAT activities and promoted RONS, LPO, and MDA elevation. This study agrees with existing evidence [90, 91], which revealed that fluoride exposure causes a decline in nonenzymatic and enzymatic antioxidants, including GSH GST, GPx, SOD, and CAT—biomarkers of oxidative stress. The drastic reductions in the cerebral and cerebellar GSH, GST, GPx, SOD, and CAT levels are an indication of oxidative stress and can sustain the generation of ROS in the form of LPO (e.g. MDA). In addition, BET treatment abated the suppression in antioxidant status observed in the cerebrum and cerebellar of rats, thereby increasing the levels of nonenzymatic and enzymatic antioxidants (GSH GST, GPx, SOD, CAT) and decreasing the levels of RONS and LPO. Exposure to xenobiotics is associated with oxidation stress that promotes cellular lipid damage, leading to MDA and 4HNE formation [92] with subsequent interaction with proteins and nucleic acid [93]. The observed neuroprotective effect of BET may be attributed to the thwarting effect of BET against NaF-induced lipid peroxidation and RONS generation. Glutathione plays a vital role in neutralising free radicals, facilitated by the activities of CAT and GPx, which are known to initiate the conversion of H2O2 to water.

Furthermore, we evaluated the effect of BET on the inflammatory and cytoprotective indices by determining cerebrum and cerebellar levels of NO, MPO, Nrf-2, HO-1, Trx, and Trx-R. This study’s fluoride exposure promoted nitrosative and oxidative stress by upregulating nitric oxide (NO) levels and downregulating HO-1, Nrf2, Trx, and Trx-R levels. Previous findings have connected Nrf-2 to an elevated antioxidant capacity and expression of protective proteins, such as the anti-inflammatory interleukin (IL)-10 [94]. Of note, suppression of the Nrf-2 system by genetic deletion in animals has been attributed to neurotoxicity characterised by elevated cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthases (iNOS), IL-6, and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and decreased anti-inflammatory [94]. Our study agrees that suppressing Nrf-2 activity in brains led to elevated oxidative stress, severe inflammation, and apoptosis [95, 96]. Earlier studies have reported the antioxidant and anti-apoptotic function of thioredoxin (Trx), and thioredoxin reductase (Trx-R) is attributed to disulfide reductase activity, which mediates protein dithiol/disulfide stability contributing to the regulation of antioxidant defence, cell growth, apoptosis, and gene expression almost all cells [97–99]. Our findings demonstrated an increase in cerebral and cerebellar MPO and NO levels, caspase-3 & -9 activities with a relative decrease in cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory biomarkers such as HO-1, Nrf-2, Trx, Trx-R and IL-10 in NaF-induced animals compared to the control. This finding suggests that NaF exposure increased NO levels and MPO activity in fluoride-exposed rats might be attributed to severe oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis. Interestingly, BET reversed the inflammatory and apoptotic indices by decreasing cerebral and cerebellar MPO, NO levels caspase-3 & -9 activities, upregulating the cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory biomarkers such as Trx, Trx-R and IL-10, and enhancing HO-1, Nrf-2 signalling activities.

According to Anatoliotakis [100], elevated myeloperoxidase activity promotes hypochlorous acid formation that may cause cell death of dopaminergic neurons, an underlying process linked to neurodegenerative diseases [101]. The influence of BET on NaF was further investigated in the histology assessment of the cerebrum and cerebellum of the treated rats. Histopathological findings revealed that BET treatment abated NaF-induced degeneration of cerebral cortex neurons and cerebellum Purkinje cell layer. Thus, BET possesses neuroprotective function in NaF-treated rats. BET counter-balanced NaF-induced neurotoxicity in rats through its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties.

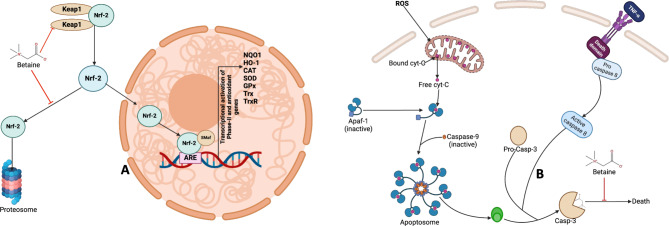

Biochemical analyses in the current study suggest the role of the Nrf-2/HO1 signalling pathway in the neuroprotective effect of BET on Naf-induced neurotoxicity as indicated by increased Nrf-2 level, enhanced antioxidative defence, reduced neuroinflammation and lower caspase activities. The favourable in silico molecular interactions of betaine with rat Keap-1 kelch domain, human Keap1 Kelch domain, and Keap1-Nrf-2 complex, as observed in this study, may account for various biological roles of BET reported in this study. The hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions of betaine with various critical amino acids in the Kelch domain may disrupt Keap1-Nrf-2 protein-protein interactions, activating Nfr2 to drive the expression of relevant genes that affect antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses. The Nrf-2 contains six highly homologous regions viz.: Neh1 to Neh6 domains. The Neh2 region, which is located at the N terminus of Nrf2, contains two structural motifs viz.: the Aspartic acid–Leucine–Glycine (DLG) and Glutamic acid–Threonine–Glycine–Glutamic acid (ETGE), which help to keep protein bound to the Keap1 Kelch domain. In the Keap1-Nrf-2 complex, the Nrf-2-Neh2 ETGE motif makes important contact with the Keap1Kelch through Ser363, Arg380, Asn382, Arg415, Arg483, Ser508, Tyr525, Gln530, Ser555 and Ser602. The Nrf-2-Neh2 DLG motif also binds with SER (363, 508, 555 & 602), ARG (380, 415 & 483), ASN 382, GLN 530, and TYR 525 of KEAP1 protein [102]. The Kelch domain where Keap1 is bounded to the Neh2 domain, which comprises six repeating Kelch motifs (K1–K6) forming a six-bladed β-propeller structure [103], has been explored for screening and identifying Nrf-2 activators [30, 31]. Our in-silico analysis revealed that betaine conducted two hydrogen bonds with ARG 415 of rat Keap 1 Kelch domain. It also made strong hydrogen bonds with ARG 380 in human Keap1. Docking with the Keap1-Nrf-2 showed strong hydrogen with ARG 415. Arg380 and Arg415 in Keap1 play critical roles in facilitating the interaction with Nrf-2, thereby regulating Nrf-2 stability and activity. Arg380 is located within the BTB (broad complex, tramtrack, and bric-a-brac) domain of Keap1. This residue normally forms hydrogen bonds with specific amino acid residues in the Neh2 domain of Nrf-2, particularly with residues in the DLG and ETGE motifs. It interacts with these motifs, facilitating the recruitment of Nrf-2 to the Keap1-Cul3 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Studies have shown that mutation of ARG380 disrupts the interaction between Keap1 and Nrf-2, leading to impaired ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf-2.

Consequently, Nrf-2 is stabilised and accumulates in the nucleus, activating the expression of antioxidant and detoxification genes (Fig. 14a). The ARG415 is located adjacent to the Kelch-repeat domain of Keap1, which is involved in electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged Neh2 domain of Nrf-2. It helps stabilise the binding of Nrf-2 to the Keap1 Kelch domain by forming salt bridges with acidic residues in the Neh2 domain, enhancing the affinity of the Keap1-Nrf-2 complex. Also, the mutation of Arg415 is known to impair the interaction between Keap1 and Nrf-2, leading to diminished ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf2. As a result, Nrf-2 is stabilised and translocated to the nucleus to activate the antioxidant response. Thus, strong hydrogen bond contacts made by betaine with these critical arginine residues may activate Nrf2 by disrupting the Keap1-Nrf-2 complex formation. Additionally, we investigated the interactions of BET with the active site of caspase-3, which revealed strong hydrogen bonds with critical amino acid residues that define the active site of the enzyme. These interactions may inhibit the action of the enzyme as an executional caspase and thereby inhibit apoptosis in the rat brain (Fig. 14b).

Fig. 14.

Molecular mechanisms of betaine on Nrf-2-Keap1 pathway and Caspase-3 activation. A: BET can inhibit the interaction between Nrf-2 and Keap1, thus enhancing the stabilisation of Nrf-2, which can translocate into the nucleus and bind to antioxidant-responsive elements (AREs) and other co-activator (SMaf) to induce the transcription of antioxidant and cytoprotective genes. B: Activation of caspase-3 is triggered by the induction of oxidative stress where ROS can impair the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane, releasing cytochrome C, which binds to apaf-1 and pro-caspase-9, releasing active caspase-9. Caspase-9 (active) cleaves inactive caspase-3 and converts it to active caspase-3. Active caspase-3 mediates the execution of programmed cell death. However, BET can form a strong interaction with the amino acid residues in the active site of caspase 3, thus suppressing its apoptotic function. Created by Arunsi Uche O. using BioRender, https://app.biorender.com/

In the molecular docking study, betaine was observed to make more hydrogen bonds with critical residues in Keap1-Nrf-2 complexes than the co-crystalised compounds (reference drugs), as shown in Table 2. Hydrogen bonds are central in determining ligand-protein interaction’s specificity, stability, and affinity [104]. Therefore, understanding the hydrogen bonding interactions between ligands and proteins is essential for rational drug design. Hydrogen bonds can provide specificity to ligand-protein interactions by forming complementary interactions between the ligand and specific amino acid residues in the protein’s binding site, as shown in our study. It also contributes significantly to the stability of ligand-protein complexes by forming transient yet strong interactions between the ligand and protein. These interactions can help anchor the ligand within the binding site and prevent its dissociation. As observed in our study, multiple hydrogen bonds collectively enhance the overall binding affinity of the ligand for the protein and can facilitate conformational changes in both the ligand and the protein, leading to an induced fit mechanism. When a ligand binds to its target protein, hydrogen bonds may form or break, inducing structural rearrangements that optimise the interactions between the ligand and protein. This conformational adaptation allows for tighter binding and optimal positioning of functional groups for subsequent biological activities. Most importantly, hydrogen bonds can also mediate interactions between the ligand, protein, and surrounding water molecules in the binding site, where water molecules may bridge hydrogen bonds between the ligand and protein residues, facilitating the complex formation and thereby further stabilise the ligand-protein complex and influence ligand binding kinetics. It is, therefore, necessary to evaluate the structural stability, conformational flexibility and free energy associated with the BET-Keap1 complex in a solvated system.

Based on the result of the binding affinity and interactions observed in the BET-Keap1 complex, which is sustained by multiple hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions as indicated by the docking simulation, we evaluated the structural stability and conformational flexibility of the BET-Keap1 complexes alongside the apoprotein and IVX-Keap1 complex in a dynamic environment. Higher fluctuations observed in the BET-Keap1 and IVX-Keap1 complexes compared to the apoKeap1 protein suggest that BET and the native compound induced a significant conformational change during the simulation. During MD simulation, low RMSD values with consistent fluctuations show equilibration of the system and stability of the biomolecular system, however, low stability is characterised by higher fluctuations. The higher RMSD values of the BET-Keap1 complex may indicate large conformational transitions by the protein’s backbone C-α atoms such that a stable conformation and strong binding with BET is attained. The BET-Keap1 complex features several hydrogen bonds comparable to the IVX-Keap1 complex. During dynamics simulations, the total hydrogen bond number formed by a small molecule compound with a receptor helps to understand the system’s interaction components, including the receptor protein, solvent molecules, and proteins. Hydrogen bonds are essential in defining a drug molecule’s stability and binding affinity with the receptor. In addition, hydrogen bond numbers may influence the solvent accessibility of the drug molecule. The RMSF computation revealed the conformational flexibility and dynamics of the BET-Keap1 complex during the dynamic simulations, which was comparable to that of the IVX-Keap1 complex as it indicated the variability of atomic positions within the receptor-drug complexes. Large fluctuations were observed around critical residues that define the binding site of Keap1 with Nrf-2 (residues 380–388). Specifically, Arg380 and Asn382 are involved in tight binding interactions of the ETGE motif of the Nrf2-Neh2 with the Keap1 Kelch domain as well as that of the Nrf2-Neh2 DLG motif with the Kelch domain of Keap1 [105]. The few notable peaks also observed around other amino acids in the binding site indicate a strong affinity of Keap1 for interacting with BET and IVX, as the interaction potentials at these points are higher. The radius of gyration estimates the distribution of atoms in the ligand-protein complexes, which provides valuable insight into the conformational flexibility and extent of folding of the protein and the complexes. Thus, indicating the complexes’ overall size, compactness, and structural properties. The average RoG values suggest that the BET-Keap1 complex had more compactness than the IVX-Keap1 complex, as smaller RoG values indicate more compactness and folding.

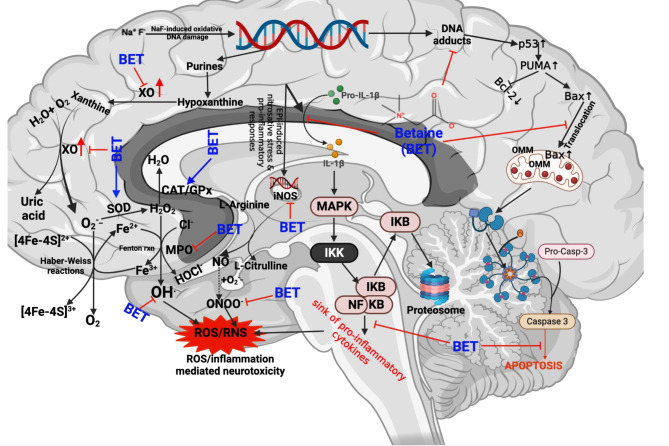

This study has revealed that BET mediates neuroprotection against NaF-induced cerebra-cerebellar damage in vivo through increased antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activity in rats. This may be driven by the modulation of the Keap1-Nrf2‐ARE signalling pathway as indicated by the strong binding affinity and interactions of BET with Keap1-Nrf2 complex as indicated by in silico investigation as depicted in our molecular mechanisms of Chemico-biological interaction to ultimately confers cellular protection. It is worthy of note that, the in-silico analysis presented in the current study complements our previous result [106], which showed the binding tendency of betaine to human Keap1 protein. Of note, the interactions of betaine with rat Keap-1, human Keap1, human Keap1-Nrf-2 complex, docking with corresponding co-crystalized compounds/reference drugs further buttressed our previous findings for validation. In addition, a demonstration of 100 ns full atomistic molecular dynamics simulation and various thermodynamic parameters suggests the stability of the betaine-Keap1 complex. Based on this understanding, we elucidate further that BET can counter-balance NaF-induced redox imbalance through various mechanisms: increasing the expression of Nrf-2, thus increasing the neuronal levels and activities of endogenous antioxidants, including SOD, CAT, GPx, GST, GSH, TSH, Trx, Trx-R while suppressing the ROS generations in the brain (Fig. 15). In addition, BET demonstrated neuroprotection by resolving inflammation as evidenced by a decrease in NO, MPO and XO levels while increasing the neuronal levels of IL-10 – a marker of anti-inflammation. Finally, the demonstration of the anti-apoptotic effect of BET in the NaF-induced neurotoxicity model reconfirms the protective roles of BET in preventing neurodegenerative diseases.

Fig. 15.

Proposed mechanistic mode of action of betaine neuroprotective effect against NaF-induced neurotoxicity in male Wistar rats. BET confers protection to the cerebellum and cerebrum rats treated with NaF by enhancing redox balance and resolving inflammation. BET achieves this by suppressing the accumulation of ROS, as evidenced through increased levels of phase-1 antioxidants, including SOD, CAT, and GPx, which can detoxify O2.− and H2O2. Furthermore, BET increased the levels of phase-2 antioxidants GST, GSH, and TSH, crucial in detoxifying lipid hydroperoxides and primary oxidative products like MDA. Failure to upregulate these antioxidant molecules may result in MDA accumulation in rats’ cerebrum and cerebellum. Aside from regulating redox balance, BET also resolves inflammation by suppressing the levels of pro-inflammatory mediators while increasing the level of anti-inflammatory markers. Furthermore, BET prevented the manifestation of apoptosis in the cerebellum and cerebrum of rats by inhibiting the activity of caspase 3. Created by Arunsi Uche O. using BioRender, https://app.biorender.com/

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

SO, UA, CI, OO, JB and BO: Conceptualization, Supervision. BO, HA, JC, OMO, MO and UA: Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. BO, JB, MA, GG, OMO, AA and UA: Molecular Docking and Simulations. SO, UA, BO, JA, CI, OO, MA, GG, OMO, AA and UA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

This study was carried out without a specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The generated data from the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Ibadan Animal Care and Use Research Ethics Committee (UI-ACUREC) with the approval number UI-ACUREC/057-1222/11. All experiments were performed according to relevant guidelines and regulations and adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines (https://www.arriveguidelines.org) to report animal experiments.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

All authors agree to the publication of the data presented in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kanduti D, Sterbenk P, Artnik B. Fluoride: a review of use and effects on health. Mater Sociomed. 2016;28:133–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston NR, Strobel SA. Principles of fluoride toxicity and the cellular response: a review. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94:1051–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adkins EA, Brunst KJ. Impacts of fluoride neurotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction on cognition and mental health: A literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Pretty IA. High fluoride concentration toothpastes for children and adolescents. Caries Res. 2016;50(Suppl 1):9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian Y, Xiao Y, Wang B, Sun C, Tang K, Sun F. Vitamin E and lycopene reduce coal burning fluorosis-induced spermatogenic cell apoptosis via oxidative stress-mediated JNK and ERK signaling pathways. Biosci Rep 2018;38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Mridha D, Priyadarshni P, Bhaskar K, Gaurav A, De A, Das A, Joardar M, Chowdhury NR, Roychowdhury T. Fluoride exposure and its potential health risk assessment in drinking water and staple food in the population from fluoride endemic regions of Bihar, India. Groundw Sustainable Dev 2021;13.

- 7.Gupta AK, Ayoob S. Fluoride in drinking Water 1ed. Boca Raton: CRC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh A, Gothalwal R. A reappraisal on biodegradation of fluoride compounds: role of microbes. Water Environ J. 2017;32:481–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vithanage M, Bhattacharya PJ. Fluoride in drinking water: health effects and remediation 2015:105–151.

- 10.Bartos M, Gumilar F, Bras C, Gallegos CE, Giannuzzi L, Cancela LM, Minetti A. Neurobehavioural effects of exposure to fluoride in the earliest stages of rat development. Physiol Behav. 2015;147:205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Zhang J, Niu R, Manthari RK, Yang K, Wang J. Effect of fluoride exposure on anxiety- and depression-like behavior in mouse. Chemosphere. 2019;215:454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Q, Wang J, Hao Y, Zhao F, Fu R, Yu Y, Wang J, Niu R, Bian S, Sun Z. Exercise ameliorates fluoride-induced anxiety- and depression-like Behavior in mice: role of GABA. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2022;200:678–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goschorska M, Baranowska-Bosiacka I, Gutowska I, Metryka E, Skorka-Majewicz M, Chlubek D. Potential Role of Fluoride in the Etiopathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Miranda GHN, Gomes BAQ, Bittencourt LO, Aragao WAB, Nogueira LS, Dionizio AS, Buzalaf MAR, Monteiro MC, Lima RR. Chronic exposure to Sodium Fluoride Triggers Oxidative Biochemistry Misbalance in mice: effects on Peripheral blood circulation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:8379123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang C, Zhang S, Liu H, Guan Z, Zeng Q, Zhang C, Lei R, Xia T, Wang Z, Yang L, Chen Y, Wu X, Zhang X, Cui Y, Yu L, Wang A. Low glucose utilization and neurodegenerative changes caused by sodium fluoride exposure in rat’s developmental brain. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;16:94–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jha SK, Mishra VK, Sharma DK, Damodaran T. Fluoride in the environment and its metabolism in humans. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2011;211:121–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao G, He F, Wu C, Li P, Li N, Deng J, Zhu G, Ren W, Peng Y. Betaine in inflammation: mechanistic aspects and applications. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehman A, Mehta KJ. Betaine in ameliorating alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61:1167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig SA. Betaine in human nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:539–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann L, Brauers G, Gehrmann T, Haussinger D, Mayatepek E, Schliess F, Schwahn BC. Osmotic regulation of hepatic betaine metabolism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G835–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorgun O, Cakir A, Bora ES, Erdogan MA, Uyanikgil Y, Erbas O. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of betaine protect against sepsis-induced acute lung injury: CT and histological evidence. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2023;56:e12906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung YS, Kim SJ, Kwon DY, Ahn CW, Kim YS, Choi DW, Kim YC. Alleviation of alcoholic liver injury by betaine involves an enhancement of antioxidant defense via regulation of sulfur amino acid metabolism. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;62:292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szkudelska K, Chan MH, Okulicz M, Jasaszwili M, Lukomska A, Malek E, Shah M, Sunder S, Szkudelski T. Betaine supplementation to rats alleviates disturbances induced by high-fat diet: pleiotropic effects in model of type 2 diabetes. J Physiol Pharmacology: Official J Pol Physiological Soc 2021;72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Szkudelska K, Szkudelski T. The anti-diabetic potential of betaine. Mechanisms of action in rodent models of type 2 diabetes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;150:112946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang C, Ma C, Gong L, Dai S, Li Y. Preventive and therapeutic role of betaine in liver disease: a review on molecular mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;912:174604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L, Liu D, Mao M, Liu W, Wang Y, Liang Y, Cao W, Zhong X. Betaine ameliorates Acute sever Ulcerative Colitis by inhibiting oxidative stress Induced Inflammatory pyroptosis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2022;66:e2200341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Jia J. Betaine mitigates amyloid-beta-Associated Neuroinflammation by suppressing the NLRP3 and NF-kappaB signaling pathways in Microglial cells. J Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD. 2023;94:S9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosas-Rodriguez JA, Valenzuela-Soto EM. The glycine betaine role in neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, hepatic, and renal diseases: insights into disease and dysfunction networks. Life Sci. 2021;285:119943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ilyas A, Wijayasinghe YS, Khan I, El Samaloty NM, Adnan M, Dar TA, Poddar NK, Singh LR, Sharma H, Khan S. Implications of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) and betaine in human health: beyond being osmoprotective compounds. Front Mol Biosci 2022;9:964624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Staurengo-Ferrari L, Badaro-Garcia S, Hohmann MSN, Manchope MF, Zaninelli TH, Casagrande R, Verri WA Jr. Contribution of Nrf2 modulation to the Mechanism of Action of Analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs in pre-clinical and clinical stages. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhakkiyalakshmi E, Sireesh D, Ramkumar KM. Chap. 12—redox sensitive transcription via Nrf2-Keap1 in suppression of inflammation. In: Chatterjee S, Jungraithmayr W, Bagchi D, editors. Immunity and inflammation in Health and Disease. Academic 2018:149–61.

- 32.Kim CK, Lee YR, Ong L, Gold M, Kalali A, Sarkar J. Alzheimer’s Disease: key insights from two decades of clinical trial failures. J Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD. 2022;87:83–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mili A, Das S, Nandakumar K, Lobo R. Molecular docking and dynamics guided approach to identify potential anti-inflammatory molecules as NRF2 activator to protect against drug-induced liver injury (DILI): a computational study. J Biomol Struct Dynamics. 2023;41:9193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buendia I, Michalska P, Navarro E, Gameiro I, Egea J, León R. Nrf2–ARE pathway: an emerging target against oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;157:84–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osama A, Zhang J, Yao J, Yao X, Fang J. Nrf2: a dark horse in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;64:101206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu Z, Sun J, Zhang W, Yu J, Zhuang C. Transcription factor NRF2 as a promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;159:87–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saha S, Buttari B, Profumo E, Tucci P, Saso L. A perspective on Nrf2 Signaling Pathway for Neuroinflammation: a potential therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:787258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villavicencio-Tejo F, Olesen MA, Aranguiz A, Quintanilla RA. Activation of the Nrf2 pathway prevents mitochondrial dysfunction induced by Caspase-3 Cleaved Tau: implications for alzheimer’s disease, antioxidants (Basel) 2022;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Sotolongo K, Ghiso J, Rostagno A. Nrf2 activation through the PI3K/GSK-3 axis protects neuronal cells from Aβ-mediated oxidative and metabolic damage. 2020;12:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Gyebi GA, Ogunyemi OM, Adefolalu AA, Rodríguez-Martínez A, López-Pastor JF, Banegas-Luna AJ, Pérez-Sánchez H, Adegunloye AP, Ogunro OB, Afolabi SO. African derived phytocompounds may interfere with SARS-CoV-2 RNA capping machinery via inhibition of 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase: an in silico perspective. J Mol Struct. 2022;1262:133019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mili A, Das S. Molecular docking and dynamics guided approach to identify potential anti-inflammatory molecules as NRF2 activator to protect against drug-induced liver injury (DILI): a computational study 2023;41:9193–210. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Abbassi R, Chamkhia N, Sakly M. Chloroform-induced oxidative stress in rat liver: implication of metallothionein. Toxicol Ind Health. 2010;26:487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Owumi SE, Aliyu-Banjo NO, Danso OF. Fluoride and diethylnitrosamine coexposure enhances oxido-inflammatory responses and caspase-3 activation in liver and kidney of adult rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2019;33:e22327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes KC, Pronczuk A, Cook MW, Robbins MC. Betaine in sub-acute and sub-chronic rat studies. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41:1685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwahn BC, Hafner D, Hohlfeld T, Balkenhol N, Laryea MD, Wendel U. Pharmacokinetics of oral betaine in healthy subjects and patients with homocystinuria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collins TF, Sprando RL, Shackelford ME, Black TN, Ames MJ, Welsh JJ, Balmer MF, Olejnik N, Ruggles DI. Developmental toxicity of sodium fluoride in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 1995;33:951–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quines CB, Rosa SG, Da Rocha JT, Gai BM, Bortolatto CF, Duarte MM, Nogueira CW. Monosodium glutamate, a food additive, induces depressive-like and anxiogenic-like behaviors in young rats. Life Sci. 2014;107:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Owumi S, Chimezie J, Otunla M, Oluwawibe B, Agbarogi H, Anifowose M, Arunsi U, Owoeye O. Prepubertal repeated Berberine Supplementation enhances Cerebrocerebellar functions by modulating neurochemical and behavioural changes in Wistar rats. J Mol Neurosci. 2024;74:72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owumi S, Chimezie J, Otunla M, Oluwawibe B, Agbarogi H, Anifowose M, Arunsi U, Owoeye O. Prepubertal repeated Berberine Supplementation enhances Cerebrocerebellar functions by modulating neurochemical and behavioural changes in Wistar rats. J Mol Neurosci 2024:74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Folarin O, Olopade F, Onwuka S, Olopade J. Memory deficit recovery after chronic Vanadium exposure in mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:4860582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarro E.C., Sullivan R.M., Barr G. Unpredictable neonatal stress enhances adult anxiety and alters amygdala gene expression related to serotonin and GABA. Neuroscience. 2014;258:147–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Misra HP, Fridovich I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1972 May 25;247(10):3170–5. PMID: 4623845. [PubMed]

- 54.Clairborne A. Catalase activity. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB. Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7130–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE, Swanson AB, Hafeman DG, Hoekstra WG. Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science. 1973;179:588–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Zampaglione N, Gillette JR. Bromobenzene-induced liver necrosis. Protective role of glutathione and evidence for 3,4-bromobenzene oxide as the hepatotoxic metabolite. Pharmacology. 1974;11:151–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohkawa H, Oshishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxidation in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979;95:351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Owumi SE, Dim UJ. Manganese suppresses oxidative stress, inflammation and caspase-3 activation in rats exposed to chlorpyrifos. Toxicol Rep. 2019;6:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15 N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Granell S, Gironella M, Bulbena O, Panes J, Mauri M, Sabater L, Aparisi L, Gelpi E, Closa D. Heparin mobilizes xanthine oxidase and induces lung inflammation in acute pancreatitis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:525–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and practice of histological techniques, 6th Edition ed., Churchill Livingston/Elsevier, China, 2008.

- 64.Taveira KV, Carraro KT, Catalao CH. Lopes Lda, Morphological and morphometric analysis of the hippocampus in Wistar rats with experimental hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2012;48:163–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011;3:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alrehaily A, Elfiky AA, Ibrahim IM, Ibrahim MN, Sonousi A. Novel sofosbuvir derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: an in silico perspective. Sci Rep. 2023;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Samir A, Elshemey WM, Elfiky AA. Molecular dynamics simulations and MM-GBSA reveal a novel small molecule against Flu A RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Biomol Struct Dynamics 2023;1–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Brooks BR, Brooks CL 3rd, Mackerell AD Jr., Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek M, Im W, Kuczera K, Lazaridis T, Ma J, Ovchinnikov V, Paci E, Pastor RW, Post CB, Pu JZ, Schaefer M, Tidor B, Venable RM, Woodcock HL, Wu X, Yang W, York DM. M. Karplus, CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:1545–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jo S, Cheng X, Islam SM, Huang L, Rui H, Zhu A, Lee HS, Qi Y, Han W, Vanommeslaeghe K, MacKerell, Jr. AD, Roux B, Im W. CHARMM-GUI PDB manipulator for advanced modeling and simulations of proteins containing nonstandard residues. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2014;96:235–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]