Abstract

Seed coating with fungicides is a common practice in controlling seed-borne diseases, but conventional methods often result in high toxicity to plants and soil. In this study, a nanoparticle formulation was successfully developed using the metal–organic framework UiO-66 as a carrier of the fungicide ipconazole (IPC), with a tannic acid (TA)-ZnII coating serving as a protective layer. The IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nanoparticles provided a controlled release, triggered and regulated by environmental factors such as pH and temperature. This formulation efficiently controlled the proliferation of Fusarium fujikuroi spores, with high penetration into both rice roots and fungal mycelia. The product exhibited high antifungal activity, achieving control efficacy rates of 84.09% to 93.10%, low biotoxicity, and promoted rice growth. Compared to the IPC flowable suspension formula, IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII improved the physicochemical properties and enzymatic activities in soil. Importantly, it showed potential for mitigating damage to beneficial soil bacteria. This study provides a promising approach for managing plant diseases using nanoscale fungicides in seed treatment.

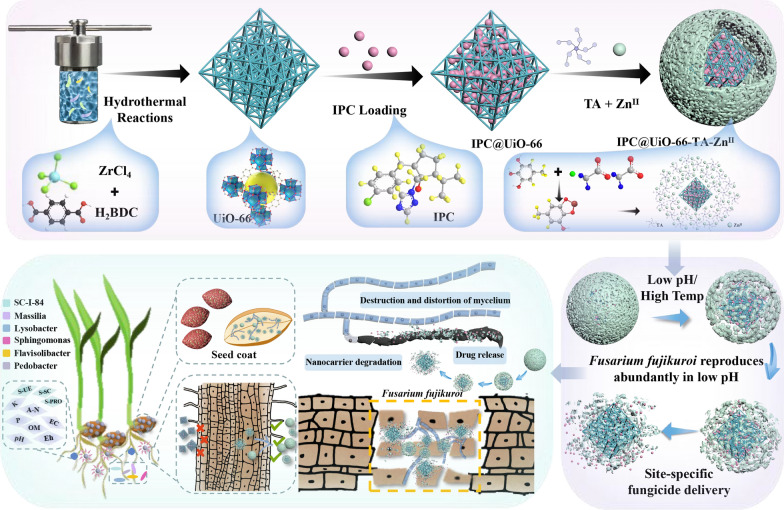

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-024-02938-y.

Keywords: Metal organic framework, Dual stimuli-responsive, Antifungal activity, Soil microorganisms, Controlled release fungicides

Highlights

IPC-loaded UiO-66 with tannic acid-ZnII shells for precision management of rice seedling disease through intelligent, responsive release.

A pH- and temperature-sensitive, controlled-release nanoparticle system was developed.

Tannic acid-ZnII-modified nanoparticles penetrate into rice roots and fungal mycelium.

Nanoparticles provide better control of Fusarium fujikuroi and promote seedling growth.

Nanoparticles reduce the pollution of soil environment by conventional seed coatings.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12951-024-02938-y.

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the most important food crops in the world but faces threats from various diseases, such as rice bakanae, rice sesame spot, and rice blast [1]. Seed treatments using fungicides in flowable suspension (FS) can effectively reduce rice seedling diseases caused by seed-borne and soilborne fungal pathogens [2, 3]. However, FS applications can negatively impact non-target soil microbial communities [4], and increase the risk of fungicide resistance developing in pathogens [5, 6]. This is because pesticides in FS have poor target delivery; therefore large quantities of pesticides are deposited in the non-target microbial communities in the surrounding soil environment. In contrast, a low effective intra-target dose transfer results in poor absorption of the active ingredient in the plant and further increases the risk of fungicide resistance in pathogens [7].

Targeted pesticide delivery is crucial for precision control of seed-borne diseases. This can be achieved by using nanoparticles as a carrier for fungicides (Table S1). Nano carriers enable high dispersion of fungicides, significantly enhancing the potential for targeted delivery. Among the available nanomaterials, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) offer inherent advantages, including structural diversity, high porosity, large specific surface area, and structural stability [8, 9]. MOF materials serve as efficient drug delivery systems with applications in various biomedical and electro-photochemical applications [10–12]. Some nano pesticides are created by encapsulating water-insoluble pesticides within a MOF without external coatings [13]. However, the open structure of MOFs may result in the premature release of pesticides before they should function. Therefore, while MOFs can be effective carriers for nano-pesticides, they may not always ensure adequate persistence for pest control.

The concept of controlled-release design for nanomaterials involves on-demand or site-specific release that responds to environmental stimuli such as pH, temperature, and humidity [13]. This approach effectively minimizes or eliminates the overuse of pesticides, thereby reducing hazards to the soil environment and non-target organisms. Physically encapsulating metal–organic frameworks within a protective shield presents an effective strategy to address both the rapid and imprecise release of active ingredients. In rice seed coating, we aim to identify the most robust “lock” to ensure the transport of the fungicide, and the most efficient “key” to “unlock” the particles, facilitating effective release of the fungicide and delivery to the target site within the pathogen.

Tannic acid (TA) is a plant-derived hydrolyzable tannin that is recognized as safe by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [14]. It has been widely used in medicine due to its potent astringent, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties. TA interacts with macromolecules through hydrogen bonding, ionic bonding, ligand binding, or hydrophobic interactions [14, 15]. Metal ions can act as multivalent sites, chelating with the abundant galloyl groups in TA to form a stable metal-polyphenol complex coating, often referred to as a nano-protective armor [16, 17]. This coating encapsulates active ingredients adsorbed into the metal framework, effectively creating a “lock” [18]. Notably, this type of lock can respond to stimulus factors such as pH, temperature, and light [13]. While some studies have explored the application of nanoparticles in seed treatments [19], the assembly of TA-ZnII shields based on MOFs and the targeted delivery mechanism of fungicides remain largely unknown.

Rice germination and seedling growth begin in water-saturated soil. Under flooded conditions, rice seeds undergo anaerobic respiration, producing carbon dioxide and lactic acid, which results in an acidic environment. This environment significantly favors the proliferation and expansion of endophytic Fusarium fujikuroi (F. fujikuroi) within the seeds, facilitating disease spread [20, 21]. Interestingly, the acidic conditions that enhance pathogen activity also create an optimal environment for triggering the release of the fungicide from its protective TA-ZnII shield. Thus, low pH values act as a triggering factor, functioning as a “key” to disintegrate the pH-sensitive coatings. In essence, this mechanism allows for the intelligent release of fungicides precisely when the pathogen is actively spreading.

The objectives of this study were to design and generate nanoparticles using the UiO-66 as a carrier for the fungicide like ipconazole (IPC), examine the effect of TA and zinc ions (ZnII) as a protective armor to enrapturing the fungicide within the nanoparticles, determine the localization of IPC delivery within plant tissues and pathogen mycelia, and evaluate the safety of seedlings and overall plant growth with this application. Additionally, the antifungal activity, non-target biosafety, and impacts on soil microbial communities of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII were investigated. This study provides new insights into the controlled release of fungicidal agents to aiming to minimize the adverse effects of traditional seed treatment in sustainable agriculture.

Methods

Preparation of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII

The synthesis of UiO-66 was carried out as described by its original authors with minor modifications [22]. Typically, ZrCl4 (35 mg) and 10 mL of N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were mixed thoroughly under sonication, followed by H2BDC (25 mg) and acetic acid (0.7 mL). The mixture was placed in an autoclave and reacted at 120 °C for 24 h. Finally, nanoscale UiO-66 (54.4 ± 1.32 mg) was obtained by washing through filtration and drying under vacuum at 60 °C overnight.

For IPC loading, 2.4 g of metal framework (UiO-66) was suspended in a mixture of IPC and DMF (15 mL) with continuous stirring for 48 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 4973 g for 5 min to obtain IPC@UiO-66, which was then washed with solvent to remove any unencapsulated IPC and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 3 h.

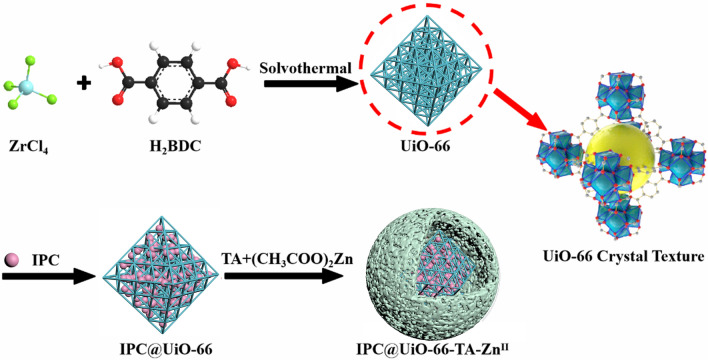

IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII with metal polyphenol shields was prepared using an assembly method. IPC@UiO-66 was dispersed in the surfactant solution to obtain an IPC solution of 1 mg/mL (Fig. 1). Subsequently, IPC@UiO-66 and TA were first dispersed together during the assembly of the shields. TA (0.2 g) was immersed in the solution containing the IPC@UiO-66 (200 mL) and shaken at 25 ℃ for 30 min, and then a (CH₃COO)₂Zn solution (0.6 g) was added. The proportions of TA, ZnII, and TA-ZnII in relation to IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII are 20%, 60%, and 80%, respectively. Upon addition, the mixed solution rapidly turned white, indicating the onset of the metal-polyphenol shield assembly process, and continued to react for 30 min, which indicated that the metal polyphenol shield assembly process had begun. The unreacted components in the resulting sample were washed away, and the solution was the centrifuged at 4973 g for 5 min and dried in an oven at 60 °C. Finally, IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII particles were obtained. The optimal process and loading capacity (LC) nanoparticles were tested in five replicates before subsequent tests. During the experiment, it was observed that surfactant concentration and sonication time had a significant impact on LC. To illustrate the interrelationship between the LC and the response variables (surfactant concentration and sonication time), the experimental data and model were fitted using 3D surface plots [23].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the possible mechanism of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII formation

IPC and zinc ions release from nanoparticles

The release of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII and IPC@UiO-66 was investigated at three different pH values (5, 7, and 9) and three different temperatures (10, 20, and 30 °C). Typically, 100 mg of pesticide particles (IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII and IPC@UiO-66) were dispersed in a dialysis bag (molecular weight cut-off: 8000 to 14,000 Da) and then immersed in 200 mL of release medium consisting of deionized water and ethanol (70:30, v/v). Each treatment was replicated three times. The cumulative release of IPC was calculated using the following formula:

where Er is the cumulative release (%) of IPC from the nanoparticles; Ve is the volume of the release medium taken at a given time interval (with Ve = 0.5 mL); V0 is the volume of release solution (200 mL); Cn (mg/mL) is the IPC concentration in the release medium at time n; mpesticide (mg) is the total pesticide loaded in the nanoparticles.

The release of zinc ions from IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII was also evaluated in this study. Detailed methods and instruments are described in the supplementary materials.

Fungicidal activity of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII against F. fujikuroi

The fungicidal activity of IPC-loaded nanoparticles against the rice bakanae pathogen F. fujikuroi was determined using the growth rate method. Potato dextrose agar (PDA) was mixed with ipconazole technical concentrate (IPC TC), IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII, and IPC FS in concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 0.5 μg/mL. PDA at different pH levels (5, 7, and 9) was mixed with IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII (concentrations ranging from 0.005 to 0.5 µg/mL) at 25 °C. PDA containing an equal amount of sterile water was used as a blank control. Each treatment was replicated three times. The effective concentration for 50% of mycelial inhibition (EC50) was calculated.

Effect of pH on F. fujikuroi spore production

Mung bean liquid media with pH 5, 7, and 9 were prepared. F. fujikuroi colonies were perforated with 5 mm-diameter mycelial discs, and then placed in the liquid medium at the corresponding pH values (5, 7, and 9) in an incubator shaker at 25 °C and 120 rpm. Five replicates were set up, and spore production was measured after 5 days.

Nanoparticle uptake by plants and fungi

The synthesized UiO-66-TA-ZnII (200 mg) was suspended in 50 mL of an ethanol solution containing 5 mg fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), the reaction mixture was centrifuged and washed. Mycelial discs (5 mm in diameter) of F. fujikuroi were placed on PDA plates amended with FITC-labeled nanoparticles. After 5 days of incubation, the mycelial tip of the colony was carefully peeled off and observed using imaging with confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Transmission electron microscope (TEM), scanning electron microscope (SEM), and CLSM imaging analyses were used to assess the fate of nanopesticides in fungi and plant root cells.

Pot experiment for determining fungicidal activity

F. fujikuroi cultures were taken from the edges of colonies using a 5 mm-diameter mycelial discs and placed in a 300 mL erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL mung bean liquid medium. Spore suspensions at a concentration of 106 units/mL were prepared and stored. Seeds were soaked in a spore suspension for 24 h and then treated with IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nano-flowable suspension for seed coating (IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS) or IPC FS (0.15 to 0.25 g/kg seed). The height of rice plants was measured after seedling emergence to compare the infection levels of F. fujikuroi under treatments with different agents. The experiment was conducted with five times replicates.

Impact of NFS on physicochemical properties and microbial communities in soil

The soil used in this indoor potting experiment was obtained from a non-treated field in Yunnan, China (24° 92′N, 99° 08′E). Three treatments were applied: IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS, IPC FS, and sterile water. The seed of rice variety ‘Long Japonica 31’ was coated according to the recommended dose of IPC (0.2 g/kg seed) and mixed thoroughly to ensure the chemical suspension was evenly distributed across the seed surface.

After the treated seeds were sown, soil samples were collected at 7, 14, 21, and 35 days and analyzed to determine their physical and chemical properties. Air-dried soil samples, which had been passed through a 2 mm sieve, were used to assess pH, reduction potential (Eh), electrical conductivity (EC), effective phosphorus (P), effective potassium (K), and organic matter (OM), urease (S-UE), sucrase (S-SC), and protease (S-PRO). Each treatment was replicated three times.

Soil microbial DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA). Primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) were used to amplify the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene [4]. Each DNA sample was analyzed triplicate. Sequencing was performed at the Shiyanjia Lab (www.shiyanjia.com). Detailed methods and instruments are described in the supplementary document.

Toxicity to plants and zebrafish

The acute toxicity of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII to zebrafish was determined using the static method. Healthy, active individuals of similar sizes were selected for testing and exposed to different concentrations of IPC TC, IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII, and IPC FS for 96 h. Fish mortality was recorded daily to assess acute toxicity. Each treatment was replicated three times.

The effects of the seed coatings on rice seed germination and emergence were investigated. IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS and IPC FS were tested at three concentrations (0.25, 0.5, and 1 g/kg seed), with a clear water treatment as the control. Seedling germination was measured within 4 to 5 days. Plant height, root length, and fresh weight of the seedlings were measured 7, 14, 21, and 35 days after sowing. Four replications of the experiment were performed.

Data analysis

All the obtained data were subjected by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) technique using SPSS 20.0 statistical analysis software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Tukey’s multiple range tests were performed to compare the treatment differences. The confidence intervals used in this study were based on 95% (P < 0.05).

Results and discussion

Synthesis of the nanoparticles

We synthesized a metal–organic framework using the hydrothermal method and loaded it with the fungicide IPC. UiO-66 was synthesized with a yield ratio of ZrCl₄: H₂BDC: UiO-66 = 1:0.714:1.55. This method is characterized by high yield, simplicity, ease of operation, and excellent reproducibility. We examined the function of the outer surface of IPC@UiO-66, formed using metal ions complexed with TA. TA possesses multiple reactive functional groups that chelate with metal ions through ligand bonds, forming complexes of different sizes and morphologies. These complexes can create a range of metal polyphenol shields, referred to as nano-protective armor [14, 17].

This two-step self-assembly interaction between the nano-protective armor and the metal framework facilitated the efficient encapsulation of IPC by the nano-armor, addressing the critical issue of low LC. Given that TA is hydrophilic while IPC is hydrophobic, an emulsion method was used to disperse IPC@UiO-66 in a TA solution with a surfactant. The IPC@UiO-66-TA-metal ion nanoparticles with CuII, FeII, and ZnII ions as cross-linking agents showed dark green, black, and white colors, respectively. However, the LC results showed minimal variation among these nanoparticles. When ZnII was used, yield values significantly improved relative to those with CuII and FeII (4.05–5.21 times higher). This improvement may be attributed to the competitive coordination bonding between metal ions and TA in different media [16].

LC of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII

In the optimization of the nano-formulation and drug-loading process, the LC is an important index for evaluating the drug delivery system. The central composite design of response surface methodology (CCD/RSM) was used to optimize the LC of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII [23]. Two factors, namely surfactant concentration (A) and ultrasonic time (B), were considered. As the values of these factors increased, the effect on LC initially increased and then decreased (Fig. 2b and c). The residuals in the plot tended to cluster around the diagonal of the predicted results (Fig. 2d and e), which indicated that the assumption of normality was satisfactory and that these two factors significantly affected LC. The resulting multivariate quadratic regression equation of surfactant concentration (A) versus ultrasound time (B) is as follows: .

Fig. 2.

Intermolecular interactions between UiO-66 clusters and TA were investigated through molecular modelling (a). Response surface map (b) and contour map (c) illustrate the effects of various factors (surfactant concentration: 0 to 5%; ultrasonic time: 0 to 120 min) on LC. Relationships between actual and predicted responses are shown (d), along with normality plots (e) for residuals from the LC analyses. The residuals clustered around the diagonal line of the predicted results, indicating that the assumption of normality was met (R2 for LC = 99%, p-value < 0.0001, n = 3)

IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII (10.55 ± 0.48%) prepared under these optimal conditions were used for characterization and performance studies. High productivity, high loading efficiency, and potential fungicidal activity led to the selection of ZnII as the crosslinking agent for fabricating IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nanoparticles loaded with IPC.

Characterization of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII

The morphological characteristics of UiO-66, IPC@UiO-66, and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII samples were observed using SEM and TEM. Uniform octahedral UiO-66 nanoparticles with an average size of approximately 163 nm were observed (Figs. 3a-1 and a-2). The morphology of the nanoparticles imchanged upon the addition of IPC to the UiO-66 (Fig. 3a-3). TEM-Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS) images confirmed the presence of Zr, O, C, Cl, and Zn elements, corresponding to Zr from UiO-66, Cl from IPC, and Zn from TA-ZnII. This was consistent with x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) results (Figs. 3b, d–f and S1). The presence of IPC in the nanoparticles and the formation of a “nano-protective armor” shield by TA-ZnII on the surface of IPC@UiO-66 were confirmed. Compared to UiO-66 and IPC@UiO-66, the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII particles (296 nm) were uniformly encapsulated in rounded spheres, demonstrating a successful transition from an octahedral to a spherical substrate structure (Figs. 3a-4–a-6). A proposed mechanism for the morphological changes is as follows: TA, possessing a rigid molecular chain, binds to the metal framework through van der Waals forces during the first self-assembly step (Fig. 2a). The crosslinking between TA and ZnII creates a more rigid and ordered structure, resulting in a shield with enhanced mechanical properties that prevents morphological collapse and completes the second self-assembly step. The assembled TA-ZnII shield is positioned on the outer surface of the metal framework, forming a compact structure that effectively encapsulates the fungicide.

Fig. 3.

SEM images of UiO-66 (a-1 and a-2) and IPC@UiO-66 (a-3); SEM and TEM images of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII (a-4–a-6) (scale bar: 500 nm–5 μm for SEM and 50 nm for TEM). EDS mapping characterization of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII (b; b-1–b-4) (Scale bar: 200 nm). FTIR spectra within the range of 4000 to 400 cm.−1 (c), XPS results within the range of 1300 to 0 eV (d), high resolution chlorine spectrum (e), zinc spectra (f), nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (g), and DTG/TG within the range of 35 to 550℃ (h and i) results for the samples. XRD patterns within the range of 5 to 80° (j), and the ζ-potentials (k)

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrum of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII showed characteristic peaks of UiO-66 at 1395.3 cm−1 (C–O–C), 678.8 cm−1 (Zr-O), and 1583.8 cm−1 (C = O). The characteristic peak of IPC was at 1508.6 cm−1 (C-N) was also present, confirming successful loading into the nanoparticles (Fig. 3c). The successful modification of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII with TA-ZnII was further evidenced by the appearance of the characteristic peak (C = O–O) of TA at 1724.5 cm−1 in IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII [24]. The intensities of UiO-66’s characteristic peaks at 1586.7 cm−1 (C = O) and 1397.2 cm−1 (C–O–C) are weakened in IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII, possibly due to van der Waals forces between UiO-66 and the TA-ZnII shield [24]. Interestingly, the characteristic peak of the ester group of TA at 1714.4 cm−1 (C = O–O) in IPC@UiO-66-TA and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII decreases, suggesting van der Waals forces cross-linking between UiO-66’s benzoic acid moiety and TA’s phenol moiety. The analysis reveals that initially, UiO-66 and TA form van der Waals forces, initiating the first stage of coordination self-assembly (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, UiO-66-TA reacts with ZnII, culminating in the completion of the final shield assembly. The two-step self-assembly process minimizes the likelihood of individual complexation of TA and ZnII, consistent with SEM and TEM results.

The porosity of the samples was then determined from N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms. The surface area of pristine UiO-66 composites was approximately 818.75 m2/g, as shown in Fig. 3g. The reason for the reduced surface area of IPC@UiO-66 (Brunauer–Emmett–Teller = 362.87 m2/g) was the presence of IPC molecules in their pores. More porosity reduction was observed after assembling the TA-ZnII shield, which was attributed to the sealing of the pores by the shield.

Thermogravimetric analysis and derivative thermogravimetry (TG-DTG) analysis revealed that the weight loss above 350℃ corresponded to the gradual oxidation of UiO-66 to zirconium oxide (Fig. 3h). The weight of IPC TC started to decrease rapidly from 230 °C to 310 °C. Additionally, IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII exhibited a gradual weight loss starting at 300 °C and 390 °C, attributed to the successful loading of IPC. The temperature at which IPC decomposes is noticeably elevated in IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII compared to IPC TC. This phenomenon is attributed to the protective nature of the TA-ZnII shield (Fig. 3i). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis indicated that the characteristic diffraction peaks of both UiO-66 and IPC were retained in IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII, thereby indicating the successful loading of IPC without destroying the UiO-66 metal framework or crystal structure of IPC during the loading modification (Fig. 3j).

Finally, the change in ζ-potential was measured to study the interactions among the materials. The surfaces of UiO-66 had more pronounced positive ζ-potentials (27.01 mV), as shown in Fig. 3k. The decrease in the potential of IPC@UiO-66 (18.75 mV), demonstrates the successful adsorption of IPC by UiO-66. The final IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nanoparticles (– 22.78 mV) were negatively charged.

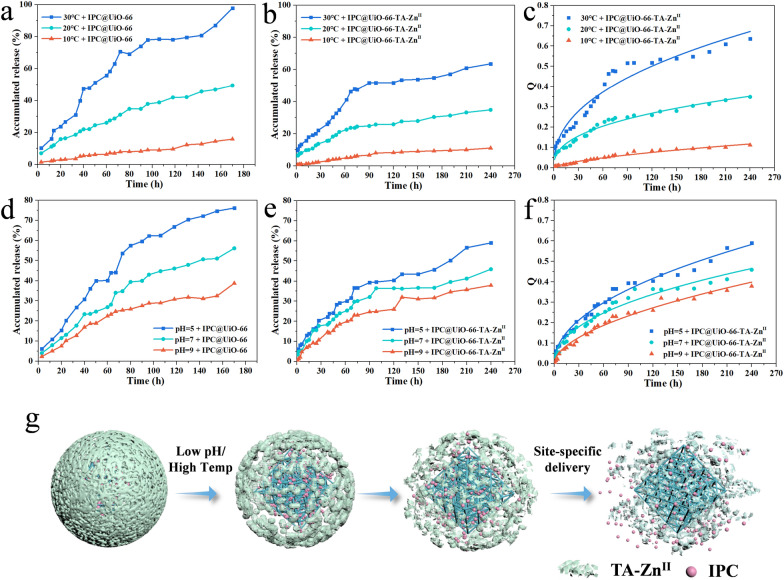

The stimulus-responsive controlled release mechanism of nanopesticides in response to pathogen spread

To evaluate the effect of the TA-ZnII shield on release performance, IPC@UiO-66 and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII were examined under varying temperatures and pH values. IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII showed significant resistance to premature release. The cumulative release efficiency of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII over 90 h was notably lower at 10 °C, 20 °C, and 30 °C, with values of 6.7%, 24.8%, and 51.6%, respectively. In contrast, IPC@UiO-66 (without TA-ZnII shields) exhibited rapid and substantial release under the same conditions, with cumulative efficiencies as high as 8.3%, 34.8%, and 73.9% (Fig. 4a and b). At pH levels of 5, 7, and 9, IPC@UiO-66 released IPC with cumulative efficiencies of 27.6%, 39.9%, and 59.6% after 90 h, while IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII achieved lower release efficiencies of 24.7%, 32.1%, and 39.3% due to partial disintegration of the TA-ZnII shield (Fig. 4d and e). This nano-protective armor not only protects the active ingredient on the metal framework but also significantly extends the active ingredient’s effective periods.

Fig. 4.

Effects of temperature (10℃, 20℃, 30℃) (a, b, c) and pH values (5, 7, 9) (d, e, f) on the release of IPC@UiO-66 and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII in ethanol: deionized water = 3:7 (v/v). Plots of the Ritger-Peppas model for the release of pesticide (c, f). Schematic diagram of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII release at various temperature and pH values (g)

After being subjected to the nano-armor protection strategy, IPC release was tested under different pH and temperature conditions to explore the response characteristics of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII. After 120 h, the release at 30 °C increased by 25.9% and 43.5% compared to 20 °C and 10 °C, respectively. The final cumulative release rate at pH 5 was 59.0%, whereas release efficiencies at pH 7 and 9 were lower only 45.9% and 37.9%, respectively. The release profiles at various temperatures and pH values best fit the Peppas equation (Fig. 4c and f; Table S2–5). IPC release may be driven by thermal effects and attenuated TA-ZnII coordination interactions. Under acidic conditions, the release of active ingredients from nanomaterials can be promoted by reducing the coordination between TA and metal ions [14, 25]. Moreover, cross-linking of ZnII may be disrupted in acidic environments, leading to fewer phenolate binding sites for metal ion complexation, while protonation of TA’s phenolic groups diminishes intermolecular interaction strength. Conversely, at high pH, the deprotonation of TA’s pyrogallol/catechol moiety increases its complexation strength, resulting in slow IPC release from IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII (Fig. 4g).

pH influences fungal growth and plant seed germination. Fungal respiration and fermentation result in the formation of a weakly acidic microenvironment, while the long processing time of rice seed germination can increase the acidity [26]. Additionally, seeds immersed in water may lead to anaerobic respiration, producing alcohol and resulting in an acidic condition that negatively affects seed germination [27]. Thus, constructing a pH-responsive delivery system based on IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII to explore site-specific release behavior is worthwhile. F. fujikuroi exhibited optimal spore production at pH 5, generating up to (3.7 ± 0.29) × 106 spores/mL. The production was progressively reduced as pH increased to pH 7 [produced (2.4 ± 0.22) × 106 spores/mL] and 9 [produced (1.8 ± 0.63) × 106 spores/mL), aligning with findings by Yadav et al. and Zhang et al. [20, 21]. The TA-ZnII shields, positioned on the outer surface of a metal framework, “lock” the fungicide, while the protective mechanism of nano-armor essentially requires a trigger. The TA-ZnII shield exhibited sensitivity to acid under spore spread conditions, with low pH condition acting as a “key” to unlock the nano-armor and facilitate timely IPC release.

Bioactivities of the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nanoparticles

The fungicidal activity of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII against F. fujikuroi was assessed under different pH conditions by measuring mycelial growth (Fig. 5a). Given that fungicide release from nanoparticles is a prolonged process, the concentration of free IPC in the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII suspension was lower than in IPC TC. Consequently, the fungicidal efficacy of the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII and IPC FS was slightly reduced compared to IPC TC at the same concentrations; however, IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII demonstrated superior activity compared to IPC FS. Control carriers, UiO-66-TA-ZnII, also showed some fungicidal activity against F. fujikuroi (Fig. S3), due to the biocidal activity of ZrIV/ZnII ions and tannic acid within the metal framework and coating shield [28, 29]. The concentration of zinc ions in the solution was determined by ICP/MS, revealing that the carrier system gradually released zinc ions into the solution (Fig. S2). It was observed that the TA-ZnII shell releases significantly more zinc ions at pH 5 compared to pH 7 and pH 9. Yadav et al. demonstrated that zinc ions released from zinc oxide nanoparticles effectively inhibit fungal growth [30]. Zinc is known for its antifungal properties against various fungi [31, 32]. Higazy et al. further reported that the inhibitory effect of metallic zinc is significantly enhanced when complexed with tannic acid [29]. Thus, the incorporation of zinc ions and TA on the surface of nanostructures can synergistically improve the bactericidal efficiency of IPC.

Fig. 5.

Fungicidal activities of IPC TC, IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII, and IPC FS against F. fujikuroi and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII against F. fujikuroi under different pH conditions (5, 7, 9) for 6 days at 25 °C (a). Control efficacy of IPC FS and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS against rice bakanae on potted rice seed plants (0.15–0.25 g/kg seed) (b, c). Seeds were soaked in a spore suspension (10⁶ units/mL) for 24 h, followed by treatment with seed coating. Rice seeds were treated with non-treated CK (A), spore suspension-treated CK (B), IPC FS (C), and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS (D), at 0.15 g/kg seed (b-1), 0.2 g/kg seed (b-2); 0.25 g/kg seed (b-3). Three-dimensional morphological maps of the surface roughness of rice seeds treated with water (d), IPC FS (e) and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS (f). An asterisk (∗) indicates a statistically significant difference at the 0.05 level, n = 5

Furthermore, the effectiveness of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII was evaluated using a bioactivity assay against rice bakanae in pot experiments. Three-dimensional topography analysis revealed that the surface roughness of rice seeds increased after IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS and IPC FS coating compared to the control (Fig. 5d–f). The surface of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS appeared smoother than that of IPC FS, indicating a more uniform coating layer. The nano-pesticide-loaded IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS showed improved control of rice bakanae (Fusarium fujikuroi), with efficacy rates ranging from 84.09% to 93.10%, compared to IPC FS, which ranged from 81.82% to 84.48% (Fig. 5b and c). These findings suggest that IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII has promising applications in sustainable agriculture. Furthermore, the EC50 of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII was 0.038 μg/mL at pH 5, and 0.042 and 0.057 μg/mL at pH 7 and 9, respectively, indicating that IPC release from IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII was enhanced under acidic conditions. Metal complexes are known to dissociate readily under acidic conditions [14, 25, 33]. Thus, the TA-ZnII shield dissociated and released IPC under the acidic conditions, resulting in an effective fungicidal effect. These findings underscore the significance of utilizing pH as a trigger to facilitate the timely release of fungicides, an innovative strategy to enhance the efficacy of IPC in the control of rice bakanae (F. fujikuroi).

Nanoparticle uptake by fungi and plants

A high degree of control over nanoparticle morphology and surface functionalization allows certain nanoparticles to penetrate plant and mycelial tissues [34]. Despite achievements in nano-mediated delivery within plants and mycelia using various sizes of nanoparticles and surface modifications [35], the entry of MOFs framework like UiO-66-TA-ZnII into plants and mycelia remains poorly understood. As shown in Fig. 6a and d, the control sample displayed no fluorescent signals. However, mycelia exposed to UiO-66-TA-ZnII-FITC showed clear fluorescence at a 488 nm laser excitation wavelength (Fig. 6b and c). SEM and TEM analyses exhibited structural deformations and ruptured cell surfaces of treated mycelia with UiO-66-TA-ZnII, including crumpling, cellular deformations, tangles, and discontinuities (Fig. 6h), indicating the potential of UiO-66-TA-ZnII as an effective carrier that can enter the mycelia. These results are consistent with Sharma et al. [19].

Fig. 6.

F. fujikuroi mycelia treated with water (a), and with UiO-66-TA-ZnII-FITC (b, c) for 5 days; Rice root cells treated with water (d), and with UiO-66-TA-ZnII-FITC (e, f) for 7 days, which were observed under a CLSM at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Rice cells treated with UiO-66 (g-1) and UiO-66-TA-ZnII (g-2–g-4) observed under TEM. F. fujikuroi mycelia treated with UiO-66-TA-ZnII, observed under TEM (h-1 and h-2) and SEM (h-3 and h-4). The images show progressive magnifications from left to right, with the red boxes indicating nanoparticles associated with individual cell walls and the blue boxes indicating twisted F. fujikuroi mycelia. The filled arrows indicate the cell wall being broken or fractured. Scale bars from 500 nm to 20 µm. CW annotates cell wall

To confirm the fate of nanoparticles on the subcellular scale, TEM analysis of UiO-66-TA-ZnII and UiO-66 bound to rice root cells was conducted. Characteristic cellular structures, such as the cell wall, were used as indicators to determine whether nanoparticles were localized in the extracellular or intracellular space. We compared UiO-66-TA-ZnII and UiO-66 as well as nanoparticles of different sizes (163 and 296 nm) and shapes (ortho-octahedral and spherical) to investigate the factors affecting the entry of nanoparticles into plant root cells. Notably, TEM images showed UiO-66-TA-ZnII was embedded in the cell walls in the intracellular space (Fig. 6g-2–g-4), whereas the smaller-scaled UiO-66 was found outside the cell walls (Fig. 6g-1). This finding was confirmed by the CLSM results obtained (Fig. 6e and f). Interestingly, we found that UiO-66-TA-ZnII entered plant cells, albeit in the form of spheres with increased sizes. Mechanistic studies have suggested that the addition of nano-protective armored TA-ZnII shields could be a major factor responsible for the successful entry of UiO-66-TA-ZnII into the cell wall. Meng et al. discovered that acidic conditions facilitate the disintegration of the outer shield of the TA-CuII nano-framework, resulting in the release of the copper ion and drug [36]. This degradation releases chelated metal elements which may function as pro-oxidants, contributing to cellular destruction. Furthermore, zinc ions are known to compromise bacterial cell membranes and enter cells [37]. TA has high antioxidant capacity and inhibits biofilm formation by reducing the expression of oxidative stress genes. Additionally, TA can also induce cellular damage by chelating metal ions, leading to cellular rupture and thereby impeding biofilm formation. Jailani et al. demonstrated that TA inhibits biofilm formation on plant roots by SEM [38]. Alternatively, it is also possible that the spherical structures of the nanoparticles improve their freedom of movement in convection within the tissues, thereby facilitating their transport to individual cell walls. Accordingly, interactions between the TA-ZnII shields and plant cell walls have increased their residence time in the vicinity of cells, providing more opportunities for the UiO-66-TA-ZnII to contact (potentially damage) and be utilized by plant cells. Our results highlight important features of nanoparticle transport in plants, emphasizing their importance in transport within plant root tissues.

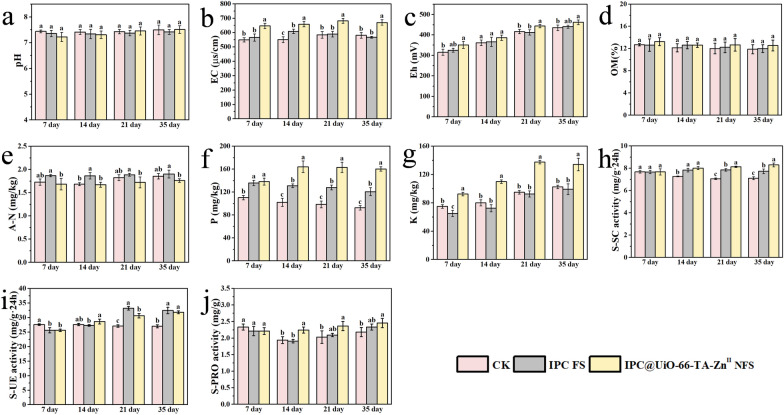

Impact of nanoparticles on the physicochemical properties of soil

In direct seeding of rice, germinating seeds encounter various stressors due to changes in soil physicochemical properties, such as a decrease in redox potential, leading to poor or delayed emergence [39]. Results showed that the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS treatment significantly increased soil pH, EC, and Eh throughout the experimental phase (Fig. 7a–c). In addition, OM levels increased by 0.44% to 0.67% over 35 days compared to the IPC FS and control treatments (Fig. 7d). These results are consistent with previous studies [40]. A-N in the soil treated with the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS decreased later in the experiment compared to the control and IPC FS treatments (Fig. 7e). However, P and K contents increased to some extent and differed significantly throughout the study (P excluded at 7 day) (Fig. 7f and g).

Fig. 7.

Effects on physicochemical properties of soil sown with rice seeds under various treatments with the addition of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nanoparticles (NFS) and IPC fungicide suspension (IPC FS). The parameters measured include: pH (a), EC (b), Eh (c), OM (d), A-N (e), P (f), K (g), S-SC (h), S-UE (i), and S-PRO (j). Rice seeds were sown in soil treated with different coatings: no pesticide coating (CK), IPC FS coating with a dose of 0.2 g/kg seed, and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS with the same dose. Differences between treatments were analyzed using the Tukey’s test, with comparisons made against the control group. Bars labeled by different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05, n = 3)

From days 14 to 35, S-SC activity was significantly higher in the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS-treated group, increasing by 0.14% to 7.41% and 10.24% to 16.69% higher, respectively (Fig. 7h). S-UE activity was also elevated in this treatment compared to the control (Fig. 7i). Additionally, S-PRO activity in the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS-treated soil increased by 12.54% to 16.47% and 5.21% to 17.52% compared to the control and IPC FS groups (Fig. 7j). Previous studies have reported that plant rhizosphere nutrients are positively correlated with soil enzyme activities and soil microorganisms [41]. In conclusion, the addition of the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII as a seed dressing positively influenced the soil microenvironment through improving key soil-related property indices.

Effects of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS on soil microbial communities

Changes in soil microbial communities significantly impact soil functions [42]. Previous studies have shown that conventional fungicides in FS significantly alter seed endophytic bacterial and fungal communities, leading to a reduction in both bacterial and fungal biomass [4]. Comparable reductions in bacterial and fungal populations are noted in soils treated with the fungicide myclobutanil and the herbicide mesosulfuron-methyl [42, 43]. In this study, the differences among IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS, IPC FS, and control groups, with PC1 and PC2 accounting for 41.1% and 18% of the variance, respectively (Fig. 8a). PC1 is the primary factor distinguishing the three sample groups. Compared to the control, IPC FS showed a greater negative bias on PC1, while IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS had a positive impact. Genera such as Sphingomonas, Lysobacter, Massilia, Pedobacter, SC-I-84, and Flavisolibacter were positively correlated with PC1, contributing significantly to the variance (Fig. 8b). These genera are known for their capability to degrade and remove challenging organic pollutants from the soil and are vital in remediating polluted environments (Bacteroidetes vadinHA17, Arenimonas, Lysobacter, Massilia, and Sphingomonas) as well as other beneficial bacteria, including Luteitalea, and SC-I-84 [44–46].

Fig. 8.

Soil bacterial community after sowing rice seeds treated with IPC FS and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS, along with the non-treated control (CK) for 7 days. OPLS-DA scores plot (a). OPLS-DA loadings plot at the genus level (blue circles represent some of the beneficial bacteria) (b). Heatmap at the genus level for the top 40 species (c), with the legend on the right displaying color intervals for different R values (n = 3). Histograms showing species composition and relative abundance of the top 20 bacterial genera (d), and family level (e). Intergroup differences classification unit presentation chart (f). Pearson’s correlation analysis of environmental factors, Mantel test, and Spearman’s correlation analysis between bacterial community and environmental factors (g, upper right panel; g lower left panel; h). Red lines represent P < 0.01, green lines represent 0.01 < P < 0.05, grey lines represent P ≥ 0.05. The number of asterisks indicate the degree of correlation: * P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01

The presence of beneficial bacteria is key to the differences observed among IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS, IPC FS, and control groups, as supported by the heatmap and Manhattan results (Figs. 8c and S4), which show that IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS significantly increased their abundance. The IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS treatment enhanced the bacterial communities at the familyand genus levels compared to CK and IPC FS-treated soil (Fig. 8d–f). Naked IPC in IPC FS had negative effects on soil flora, while the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII effectively dispersed IPC at the nanoscale and encapsulated it, which reduced the adverse effects on soil flora.

Linking different bacterial communities to environmental variables has elucidated key factors affecting the variability of bacterial community composition in soil. The Mantel test and Pearson correlation plots showed the correlation and significance between the bacterial communities and each environmental factor. Soil bacterial communities were significantly affected by the EC, P, and S-PRO (P < 0.01) as well as by K content (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8g). Furthermore, the correlation heatmaps analyses utilize Spearman correlation to reveal the relationship between the abundance of the phyla and environmental factors (Fig. 8h). This analysis highlighted that the driving directions of pH and EC are clearly opposite, which aligns with the results reported by Gan et al. [47]. This indicates that these factors are interdependent within the soil ecosystem.

Safety evaluation of IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII in zebrafish

As shown in Table S6, at 96 h, the LC50 values were 1.983 and 2.588 mg/L for IPC FS and IPC TC, respectively, while it was 6.283 mg/L for IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII. The toxicity of IPC FS and IPC TC to zebrafish was significantly higher than that of the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nanoparticles. This lower toxicity may be attributed to the slow release of IPC encapsulated in the IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII nanoparticle system, thus reducing both the concentration of IPC in the solution and its acute toxicity to zebrafish, unlike IPC FS. Additionally, the surfactants present in IPC FS may contribute to toxicity [48]. These results suggest that IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII is a safer alternative for practical application in rice fields.

Effects of seed coating with IPC FS and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS on rice seed germination and emergence

In a directly seeded rice production system, delayed emergence and poor seedling establishment represent major constraints [39]. In safety assessment experiments, the germination rates of seeds treated with IPC FS and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS were 89.33% to 92.67% and 95.33% to 96.00%, respectively, across three concentrations (0.25, 0.5, and 1 g/kg seed), compared to CK (95.33%) (Fig. 9a and b). Seedling emergence was 88% to 92.67% for IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS-treated seeds, 76.00% to 84.67% for IPC FS-treated seeds, and 86.67% for the CK group (Fig. 9c–e). These results indicated that rice seeds treated with IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII exhibited high germination and seedling emergence rates, demonstrating that the treatment was expected to address the issue of poor emergence in direct seeding of rice. Plant height, root length, and fresh weight of rice seedlings were measured at 7, 14, 21, and 35 days after sowing (Fig. 9f–h). The values of physiological indicators decreased at higher concentrations of IPC FS compared to those in the control group, suggesting a slight phytostatic effect of the fungicide IPC and the adjuvants.

Fig. 9.

Effects of IPC FS and IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS used for seed coating on rice seed germination and seedling growth (a, c, d). Seed coatings included: IPC FS (A, B, C), IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS (D, E, F), and non-treated control (CK, G), applied at seed coating rates of 0.25 g /kg seed (A and D), 0.5 g /kg seed (B and E); and 1 g /kg seed (C and F). Rice seed germination evaluated 4 to 5 days post-seeding (b); seedling emergence evaluated at 2 to 3 leaf stage of rice or 21 days post-seeding (e). Additionally, root length (f), plant height (g), and fresh weight (h) of rice were measured at different stages of rice growth, at 7, 14, 21, and 35 days, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed by comparing treatments to the control group, with asterisk (*) indicating statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level (n = 4)

The effects of triazole fungicides on seed germination are well documented [49]. In this study, we prepared a novel IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII seed coating containing TA, ZnII, and UiO-66. This could be attributed to the fact that IPC was uniformly dispersed and released in a controlled manner within the protective shield, reducing the adverse effects of highly localized concentrations on the seeds. Seed coating is a “feed seed” technique that delivers enhancement materials (micronutrients, fungicides, etc.) directly to the seed [50]. The seed coating retains nutrients on the surface and delivers them to the plant. Polyphenols are known to impede the growth of plants [51]. Aktar et al. found that while TA alone stunts the growth of Mung bean plants, plants exhibited significant growth when grown with the metal-polyphenol complexes (shoot 155%, root 200%) [51]. Zinc is an essential micronutrient for normal plant development and growth, and its deficiency results in reduced biomass, stunted growth, and chlorosis in young leaves [50]. Hu et al. reported that a seed dressing with an appropriate concentration of ZnII promoted seedling emergence, tillering, and root development [52]. Supplying essential nutrients during the early stages of seed growth and root development minimizes the risk of early nutritional deficiencies in plants. Overall, the nano-pesticide-carrying IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII demonstrated superior safety for germination and effectively improved seedling emergence and plant height of rice.

Conclusions

A temperature- and pH-responsive nanoparticle was successfully developed via the unique complexation and assembly of TA-ZnII shields formed on the outer surface of an IPC@UiO-66 metal framework. This study demonstrated that the protective armor of TA and ZnII effectively encapsulate the fungicide IPC, enabling smart response release mechanisms, facilitating plant tissue penetration, and enhancing fungicide efficacy. Acidic conditions promote the growth of F. fujikuroi and also trigger the “disarm” of the TA-ZnII shield, resulting in on-demand antipathogen effects. The IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII formulation exhibited lower toxicity in zebrafish, compared to IPC TC and IPC FS. Additionally, the TA-ZnII component effectively promotes the direct germination of rice seeds. The IPC@UiO-66-TA-ZnII NFS treatment improves the physicochemical properties as well as enzymatic activities of the soil, while also increasing the abundance of beneficial soil bacteria in the rhizosphere soil compared to the conventional IPC FS treatments. This suggests an effective pesticide formulation strategy for controlling diseases in rice seeds. The method developed for preparing the nano seed coating agent is characterized by its simplicity, controllable conditions, and high reproducibility, laying a solid foundation for industrial development and promising future applications. However, additional exploration of process parameters is required for pilot-scale and large-scale production. Additionally, the prepared nano seed coating agent has been tested in the field to assess its effectiveness in preventing seedling diseases, yielding promising results. Further replication and verification of the data are necessary.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

QZ conducted an experiment, analyzed the data, and wrote a manuscript. XS and YX collected samples. TG, HJ, and XL are responsible for the implementation of data collection. JH and PL are responsible for the review of manuscripts. PL and XL are responsible for the review of financial support.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1700300).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirmed that all methods involving the plant and its material adhered with the relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xili Liu, Email: seedling@cau.edu.cn.

Pengfei Liu, Email: pengfeiliu@cau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Abdelrahman TM, Qin X, Li D, Senosy IA, Mmby M, Wan H, et al. Pectinase-responsive carriers based on mesoporous silica nanoparticles for improving the translocation and fungicidal activity of prochloraz in rice plants. Chem Eng J. 2021;404:126440. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ren X, Chen L, Yu C, Zhao L, Su X, Shun H, et al. Development and application of a novel suspension concentrate for seed coating of rice for controlling bakanae disease and seedling rot disease. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1418313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh A, Dhiman KC, Kanwar R, Kapila RK. Effect of seed coating on seed storability and longevity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agric Res J. 2021;58(3):399–406. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma Z, Feng H, Yang C, Ma X, Li P, Feng Z. Integrated microbiology and metabolomics analysis reveal responses of cotton rhizosphere microbiome and metabolite spectrum to conventional seed coating agents. Environ Pollut. 2023;333:122058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Mao C, Zhai X, Jamieson PA, Zhang C. Mutation in cyp51b and overexpression of cyp51a and cyp51b confer multiple resistant to DMIs fungicide prochloraz in Fusarium fujikuroi. Pest Manage Sci. 2021;77(2):824–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Li Y, Zhang B, Gao X, Shi M, Zhang S, et al. Functionalized carbon dot-delivered RNA nano fungicides as superior tools to control Phytophthora pathogens through plant RdRP1 mediated spray-induced gene silencing. Adv Funct Mater. 2023. 10.1002/adfm.202213143.39071865 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rangasamy K, Athiappan M, Devarajan N, Parray JA. Emergence of multi drug resistance among soil bacteria exposing to insecticides. Microb Pathog. 2017;105:153–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng X, Li X, Meng S, Shi G, Li H, Du H, et al. Cascade amplification of tumor chemodynamic therapy and starvation with re-educated TAMs via Fe-MOF based functional nanosystem. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiang X, Pang H, Ma T, Du F, Li L, Huang J, et al. Ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction combined with Fe-MOF based bio-/enzyme-mimics nanoparticles for treating of cancer. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang B, Yao H, Yang J, Chen C, Shi J. Construction of a two-dimensional artificial antioxidase for nanocatalytic rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shelonchik O, Lemcoff N, Shimoni R, Biswas A, Yehezkel E, Yesodi D, et al. Light-induced MOF synthesis enabling composite photothermal materials. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang F, Lu X, Kuai L, Ru Y, Jiang J, Song J, et al. Dual-Site biomimetic Cu/Zn-MOF for atopic dermatitis catalytic therapy via suppressing Fcγr-mediated phagocytosis. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146(5):3186–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong J, Chen W, Feng J, Liu X, Xu Y, Wang C, et al. Facile, smart, and degradable metal-organic framework nanopesticides gated with FeIII-tannic acid networks in response to seven biological and environmental stimuli. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(16):19507–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma M, Zhong Y, Jiang X. Thermosensitive and pH-responsive tannin-containing hydroxypropyl chitin hydrogel with long-lasting antibacterial activity for wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;236:116096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Z, Wang D, Sønderskov SM, Xia D, Wu X, Liang C, et al. Tannic acid-functionalized 3D porous nanofiber sponge for antibiotic-free wound healing with enhanced hemostasis, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ejima H, Richardson JJ, Liang K, Best JP, van Koeverden MP, Such GK, et al. One-step assembly of coordination complexes for versatile film and particle engineering. Science. 2013;341(6142):154–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan J, Gong G, Wang Q, Shang J, He Y, Catania C, et al. A single-cell nanocoating of probiotics for enhanced amelioration of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Shora HM, Khateb AM, Darwish DB, El-Sharkawy RM. Thiolation of myco-synthesized Fe3O4-NPs: a novel promising tool for penicillium expansium laccase immobilization to decolorize textile dyes and as an application for anticancer agent. J Fungi. 2022;8(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma AB, Sidhu A, Manchanda P, Ahuja R. 1,2,4-triazolyldithiocarbamate silver nano conjugate: potent seed priming agent against bakanae disease of rice (Oryzae sativa). Eur J Plant Pathol. 2022;162(4):825–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yadav RS, Tyagi S, Javeria S, Gangwar RK. Effect of different cultural condition on the growth of fusarium moniliforme causing bakanae disease. Eur J Mol Biotechnol. 2014;4(2):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang M. Exploration the pathogenic factors of melon root rot and development of Trichoderma fertilizer-A case of Tangshan. Hebei Normal University of Science Technology. 2019.

- 22.Kandiah M, Nilsen MH, Usseglio S, Jakobsen S, Olsbye U, Tilset M, et al. Synthesis and stability of tagged UiO-66 Zr-MOFs. Chem Mater. 2010;22(24):6632–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Sharkawy RM, Khairy M, Zaki MEA, Abbas MHH. Innovative optimization for maximum magnetic nanoparticles production by Trichoderma asperellum with evaluation of their antibacterial activity, and application in sustainable dye decolorization. Environ Technol Innov. 2024;35:103660. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang B, Xin T, Shen L, Zhang K, Zhang D, Zhang H, et al. Acoustic transmitted electrospun fibrous membranes for tympanic membrane regeneration. Chem Eng J. 2021;419:129536. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ninan N, Forget A, Shastri VP, Voelcker NH, Blencowe A. Antibacterial and Anti-inflammatory pH-responsive tannic acid-carboxylated agarose composite hydrogels for wound healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(42):28511–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller CP, Hoffmann JF, Ferreira CD, Diehl GW, Rossi RC, Ziegler V. Effect of germination on nutritional and bioactive properties of red rice grains and its application in cupcake production. Int J Gastronomy Food Sci. 2021;25:100379. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wahyuni S, Agustiani N, Salma S, Widiastuti ML. Seed treatment to improve seedling establishment in the anaerobic conditions. 2nd Int Conf Sustain Agric Rural Dev. 2021;653:012106. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Liu K, Qin M, Lan W, Wang L, Liang Z, et al. Abundant tannic acid modified gelatin/sodium alginate biocomposite hydrogels with high toughness, antifreezing, antioxidant and antibacterial properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;309:120702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higazy A, Hashem M, ElShafei A, Shaker N, Hady MA. Development of anti-microbial jute fabrics via in situ formation of cellulose-tannic acid-metal ion complex. Carbohydr Polym. 2010;79(4):890–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yadav A, Sohlot M, Sahu SR, Banerjee T, Bhattacharya J, Bandyopadhyay K, et al. Determination of antifungal efficacy and phytotoxicity of a unique silica coated porous zinc oxide nanocomposite medium for slow-release agrochemicals. J Appl Microbiol. 2024;135(7):153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Sharkawy RM, Abbas MHH. Unveiling antibacterial and antioxidant activities of zinc phosphate-based nanosheets synthesized by Aspergillus fumigatus and its application in sustainable decolorization of textile wastewater. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23(1):358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sardella D, Gatt R, Valdramidis VP. Physiological effects and mode of action of ZnO nanoparticles against postharvest fungal contaminants. Food Res Int. 2017;101:274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang H, Li P, Liu C, Ma H, Huang H, Lin Y, et al. pH-Responsive nanodrug encapsulated by tannic acid complex for controlled drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2017;7(5):2829–35. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avellan A, Yun J, Zhang Y, Spielman-Sun E, Unrine JM, Thieme J, et al. Nanoparticle size and coating chemistry control foliar uptake pathways, translocation, and leaf-to-rhizosphere transport in wheat. ACS Nano. 2019;13(5):5291–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Goh NS, Wang J, Pinals RL, González-Grandío E, Demirer GS, et al. Nanoparticle cellular internalization is not required for RNA delivery to mature plant leaves. Nat Nanotechnol. 2021;17(2):197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng W. Preparation and analytical application of metal-doped silicon nanocarriers in response to tumor microenvironment. Shanxi University, 2023.

- 37.Jin J, Shen H, Liu X, Ba L, Yang H, Zhu C, et al. Antibacterial effect of nano-Zinc oxide preparation on surface of environmental articles in intensive care unit. Chin J Disinfect. 2022;39(10):724–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jailani A, Ahmed B, Lee JH, Lee J. Inhibition of agrobacterium tumefaciens growth and biofilm formation by tannic acid. Biomedicines. 2022;10(7):1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mori S, Fujimoto H, Watanabe S, Ishioka G, Okabe A, Kamei M. Physiological performance of iron-coated primed rice seeds under submerged conditions and the stimulation of coleoptile elongation in primed rice seeds under anoxia. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2012;58(4):469–78. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W, Long J, Li J, Zhang M, Ye X, Chang W, et al. Effect of metal oxide nanoparticles on the chemical speciation of heavy metals and micronutrient bioavailability in paddy soil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du Y, Zhang Q, Yu M, Yin M, Chen F. Effect of sodium alginate-gelatin-polyvinyl pyrrolidone microspheres on cucumber plants, soil, and microbial communities under lead stress. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;247:125688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ju C, Xu J, Wu X, Dong F, Liu X, Zheng Y. Effects of myclobutanil on soil microbial biomass, respiration, and soil nitrogen transformations. Environ Pollut. 2015;208:811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du P, He H, Wu X, Xu J, Dong F, Liu X, et al. Mesosulfuron-methyl influenced biodegradability potential and N transformation of soil. J Hazard Mater. 2021;416:125770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y, Gao Y, Chen W, Zhang W, Lu X. Shifts in bacterial diversity, interactions and microbial elemental cycling genes under cadmium contamination in paddy soil: implications for altered ecological function. J Hazard Mater. 2024;461:132544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han H, Wu X, Hui R, Xia X, Chen Z, Yao L, et al. Synergistic effects of Cd-loving Bacillus sp. N3 and iron oxides on immobilizing Cd and reducing wheat uptake of Cd. Environ Pollut. 2022;305:119303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng Y, Zhao H, Zhang X, Li X, Chi G. The dissipation of organophosphate esters mediated by ryegrass root exudate oxalic acid in soil: analysis of enzymes activities, microorganism. Chemosphere. 2024;356:141896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gan C, Cui S, Wu Z, Yang J. Multiple heavy metal distribution and microbial community characteristics of vanadium-titanium magnetite tailing profiles under different management modes. J Hazard Mater. 2022;429:128032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang X, Niu J, Zhou Z, Tang G, Yan G, Liu Y, et al. Stimuli-responsive polymeric micelles based on cellulose derivative containing imine groups with improved bioavailability and reduced aquatic toxicity of pyraclostrobin. Chem Eng J. 2023;474:145789. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C, Wang Q, Zhang B, Zhang F, Liu P, Zhou S, et al. Hormonal and enzymatic responses of maize seedlings to chilling stress as affected by triazoles seed treatments. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;148:220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adhikari T, Kundu S, Rao AS. Zinc delivery to plants through seed coating with nano-zinc oxide particles. J Plant Nutr. 2016;39(1):139–49. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aktar J, Ray M. Iron-polyphenol nanomaterial removes fluoride and methylene blue dye from water and promotes plant growth. J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10(3):107707. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu Z, Ma C, Ren S, Zhang Y, Chen J, Li X. Effects of ZnSO4 seed dressing on the growth and development of wheat seedling. Hubei Agric Sci. 2017;56(4):613–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.