Abstract

Background

Epithelial downgrowth is a rare complication of ocular surgery. While the features of epithelial downgrowth following corneal transplantation are well described, its association with primary graft failure has only been reported once previously. We report a case of primary corneal graft failure (PGF) associated with retrocorneal epithelial cell ingrowth.

Case presentation

A 59 year-old male underwent an uncomplicated penetrating keratoplasty for Fuchs' corneal dystrophy. The patient developed PGF, and a second transplant was performed 5 weeks after the initial surgery. The initial host corneal button and the failed corneal graft were examined with light microscopy. Histopathologic examination of the excised corneal button demonstrated multilaminar epithelial cells on the posterior corneal surface and absence of endothelial cells. DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for herpes simplex virus (HSV) DNA was performed on the failed corneal graft. Polymerase chain reaction performed on the failed corneal graft was negative for HSV DNA, which has been implicated in selected cases of PGF. Three years following repeat penetrating keratoplasty, there was no evidence of recurrent epithelial ingrowth.

Conclusion

This is only the second report of PGF associated with epithelialization of the posterior corneal button, which most likely developed subsequent to, instead of causing, the diffuse endothelial cell loss and primary graft failure.

Background

Epithelial downgrowth is an unusual but recognized complication of ocular surgery [1]. Characteristic features of epithelial downgrowth following corneal transplantation are well described [2], although the association of epithelial downgrowth and PGF has only been made once previously [3]. We present the second case of PGF in which the excised corneal button demonstrated epithelialization of the posterior cornea, most likely secondary to postoperative epithelial cell migration across a denuded Descemet's membrane.

Case presentation

A 59 year-old male with Fuchs' endothelial dystrophy presented with visually limiting pseudophakic corneal edema in his right eye with a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/50. Cataract extraction had been performed two years previously in the right eye through a 3.2 mm limbal incision. An uncomplicated penetrating keratoplasty was performed, with an 8.25 mm donor cornea secured into an 8 mm recipient opening with 16 interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures. On the first postoperative day, the graft demonstrated diffuse 3+–4+ stromal edema and a nearly complete epithelial defect. The anterior chamber was deep, and no aqueous leakage was noted from either the wound or suture tracks. The epithelial defect resolved in the first postoperative week, although 1+–2+ stromal edema persisted. As the graft remained edematous 4 weeks later, the patient was diagnosed with PGF, and a repeat penetrating keratoplasty was performed 5 weeks after the primary graft. Three years later, the second graft remains clear, with a central pachymetry of 495 μm, and corrected visual acuity of 20/25+.

The host corneal button removed at the initial penetrating keratoplasty and the failed donor corneal button were formalin-fixed and analyzed with light microscopy after staining with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and Masson trichrome stains. Histopathologic examination of the host corneal button revealed stromal edema, thickening and excrescences of Descemet's membrane, and a decreased number of endothelial cells, consistent with Fuchs' corneal dystrophy. Histopathologic examination of the failed corneal graft revealed a markedly thickened stroma and near complete absence of endothelial cells. Both sides of the excised donor corneal button were covered with epithelial cells, consistent with epithelial downgrowth. (Figure 1) The corneal sections containing suture tracks were stained with the periodic acid Schiff stain to demonstrate Descemet's membrane. (Figure 2) The suture tracks passed through the true epithelial layer, Bowman's layer, and extended into the stroma, confirming that the button had not been inverted when secured into the recipient opening. Additionally, serial sectioning of the host corneal button failed to demonstrate the presence of epithelial cells on the posterior corneal surface.

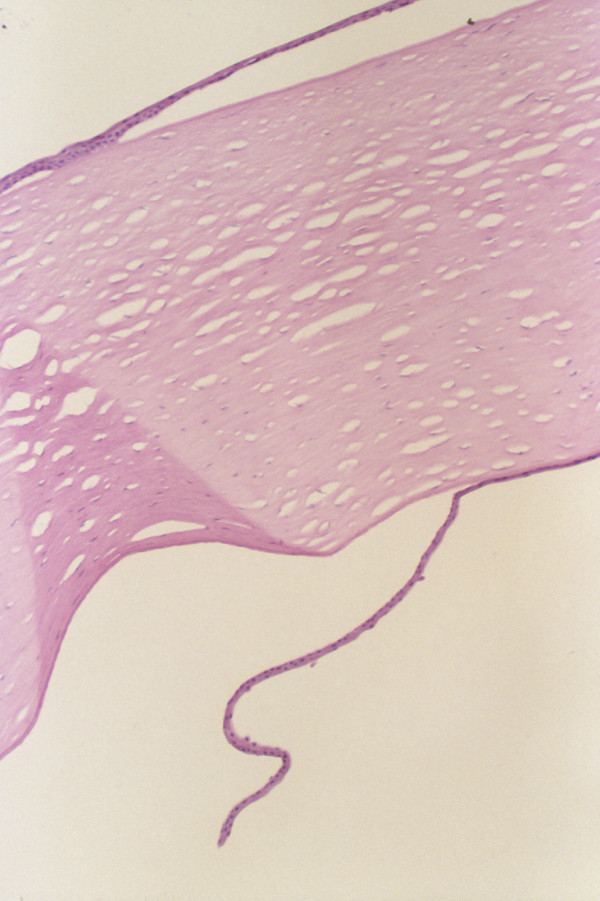

Figure 1.

Histopathologic section of excised corneal button demonstrating a markedly thickened, edematous stroma and the presence of multilayered epithelial cells on the anterior and posterior surfaces (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification × 50).

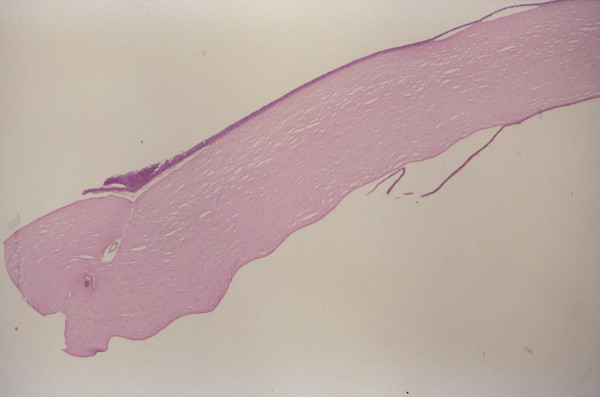

Figure 2.

Histopathologic section of excised corneal button demonstrating anterior portion of suture track seen as focal tissue separation on superior side of corneal button. The identification of Descemet's membrane as a dark band on the inferior side of the corneal button indicates that the donor corneal button had been correctly oriented when secured into the recipient opening (periodic acid Schiff stain, original magnification × 50).

To investigate the possibility of HSV infection of the donor cornea, which has been associated with one-third of cases of PGF [4,5], PCR analysis of the donor corneal button for HSV DNA was performed. Positive and negative controls confirmed adequate extraction of purified DNA from the failed donor corneal button, as well as the sensitivity and specificity of the HSV primers used. PCR analysis for HSV DNA was negative in the donor corneal button.

A complete review of the first donor's medical and eye bank records was performed. The tissue was obtained through the University of California, San Francisco tissue bank from a 56 year-old female donor who died from a myocardial infarction and cardiac tamponade. Routinely performed serologic screening tests and biomicroscopic examination of the donor button were unremarkable. The endothelial cell count was 2852 cells/mm2, and death to preservation was 12 hours, with a 51-hour preservation time in Optisol-GS.

The paired donor cornea was transplanted into another recipient several hours after this patient's original transplant. This cornea also appeared unremarkable on biomicroscopic examination, remained in Optisol-GS for 53 hours prior to transplantation, and had a cell count of 2841 cells/mm2. Five months later, after a similar 16 interrupted suture technique, the graft was clear and compact with central corneal pachymetry of 538 μm.

Conclusion

Epithelial downgrowth is an unusual complication after penetrating keratoplasty [1-3,6-17]. (Table 1) The incidence in patients undergoing aphakic penetrating keratoplasty has been estimated at 0.25% [3], and risk factors include poor wound apposition, full-thickness suture passes, and globe hypotony [1]. Characteristic signs, such as a migratory endothelial line, elevated intraocular pressure and effacement of the normal iris architecture, have been reported between 14 days and 13 years after penetrating keratoplasty [2,3].

Table 1.

Summary of Reported Cases of Epithelial Downgrowth (ED) after Penetrating Keratoplasty (PK)

| Author | Previous ocular surgery | PK Indication | Time from PK to ED diagnosis | Clinical features of ED | Diagnosis of ED | Final Anatomic/ Visual Status |

| Chiou et al [1] | 3 PKs, 2 Trabs, 1 CPC | Graft Failure | 13 months | Concentric peripheral retrocorneal membrane | Confocal microscopy | BSCVA 20/400 |

| Feder & Krachmer [2] | ICCE | ABK | 6 months | Iritis, glaucoma, posterior corneal line | Paracentesis, laser | Graft decompensation, glaucoma |

| ICCE | PBK | 7 months | Iritis, glaucoma | Paracentesis, laser | End-stage glaucoma | |

| ICCE | Fuchs' dystrophy | 5 months | Posterior corneal line | Paracentesis, laser | Evisceration | |

| ECCE | KCN | 13 years | Iritis | Paracentesis, laser | Phthisis bulbi | |

| Mazow [7] | None | Endothelial dystrophy | 5 months | Glaucoma | Histopathologic | Enucleation |

| Karabatsas [8] | 2 PKs | PBK | 8 months | Posterior corneal line, glaucoma | Clinical features | Not available |

| Sugar [3] | PK, ICCE | Graft failure | 7 months | Retrocorneal membrane, pre-iris membrane | Histopathologic | Recurrent retrocorneal membrane; CF VA* |

| ICCE | ABK;Fuchs' dystrophy | 2 weeks | Descemet's deposits | Histopathologic | BSCVA 20/200† | |

| LK, ICCE | Opacification of lamellar graft | 16 months | Pre-iris membrane | Histopathologic | Scarred regraft; VA 10/400 | |

| PK, ICCE | Graft failure | 6 months | Retrocorneal membrane | Clinical features | Vascularized, edeamatous regraft, VA HM | |

| Leibowitz [9] | 2 PKs | Graft failure | 1 month | Retrocorneal membrane; anterior chamber epithelial cyst | Histopathologic | Vascularized, opacified regraft |

| Groh & Naumann [10] | None | KCN | 13 months | Anterior chamber epithelial cyst | Clinical features | VA 14/20 |

| None | Lattice corneal dystrophy | 47 months | Anterior chamber epithelial cyst | Clinical features | VA 10/20 | |

| Wearne [11] ‡ | None | Scarring 2° to HSV keratitis | 10 years | Anterior chamber epithelial cyst | Clinical features | VA 6/20 |

| Yamaguchi et al. [12] | PK, ICCE | Graft failure | 12 months | Retrocorneal membrane | Clinical features and histopathologic | Opacified regraft |

| Sidrys [13] ¶ | ICCE | PBK | 3 weeks§ | Retrocorneal membrane | Clinical features and histopathologic | VA 6/60Θ |

| Weiner [14]# | Unknown | Various | Unknown | Retrocorneal membrane, glaucoma | Clinical features and histopathologic | Unknown |

| Kurz & D'Amico [16] | None | Corneal scar | 10 months | None | Histopathologic | Unknown |

| None | Corneal scar | 8 weeks | None | Histopathologic | Enucleation** | |

| Bennett & D'Amico [15] | None | KCN | 3 years | Iris epithelial inclusion cyst | Clinical features and histopathologic | S/p sector iridectomy without recurrence |

| Claoue et al [17] | None | KCN | 21 months | Iris epithelial inclusion cyst | Clinical features and histopathologic | S/p sector iridectomy without recurrence |

| Daneshvar et al. [6] | CE | ABK | 1 year | Glaucoma, retrocorneal membrane | Laser, ultrasound biomicroscopy | No recurrence 16 months after repeat PK |

BSCVA = best spectacle corrected visual acuity; ABK = aphakic bullous keratopathy; CF = counting fingers; CPC = cyclophotocoagulation; ECCE = extracapsular cataract extraction; HM = hand motions; HSV = herpes simplex virus; ICCE = intracapsular cataract extraction; KCN = keratoconus; LK = lamellar keratectomy; PBK = pseudophakic bullous keratopathy; Trab = trabeculectomy; * limited by ARMD; † h/o CME and RD s/p SB; ‡same patient reported again in; 10§ epithelial downgrowth through a cataract wound fistula; Θ limited by CME; ¶ same patient reported again in; 12 # 13 patients reported; ** performed after traumatic wound dehiscence and total retinal detachment

The histopathologic finding of epithelial downgrowth on the posterior corneal surface after a diagnosis of PGF is rare. Sugar and colleagues reported a patient with PGF 1 week after penetrating keratoplasty [3]. Histopathologic examination of the failed corneal graft excised 2 weeks after the initial transplant demonstrated stratified squamous epithelium covering Descemet's membrane. Though the patient had undergone a previous uncomplicated intracapsular cataract extraction, there was no evidence of epithelial downgrowth on the patient's native cornea. The authors speculated that epithelial migration over Descemet's membrane had occurred during storage.

Identifying the origin of the epithelial cells (donor or host), as well as the timing of epithelial cell access to the posterior cornea, in our case required further investigation. Inadvertent inversion of the donor corneal button during penetrating keratoplasty was excluded by identifying suture tracks extending into the stroma from the true anterior corneal surface.

If PGF had occurred secondary to epithelial cell migration over Descemet's membrane, the migration would have had to begin while the donor cornea was in storage medium. Since epithelial migration is inhibited by an intact endothelium, epithelial extension would have required diffuse endothelial cell loss [18]. In this case, there was no evidence of endothelial loss during harvesting. Additionally, there was no evidence of HSV infection of the donor cornea.

Storage at 4°C, as in the case we report, is designed to inhibit microbial cellular metabolism, and we are unaware of any evidence that human corneal epithelial cells retain sufficient metabolic activity at 4°C to allow proliferation and migration. Furthermore, the donor button in this case was preserved for only 51 hours prior to transplantation, an insufficient amount of time for the epithelial cells to have migrated over the scleral rim and onto the posterior corneal surface [19].

If the epithelial cells on the posterior corneal surface were not of donor origin, then they must be host-derived. The possibility that these cells gained entry during the prior cataract surgery was dismissed by both the absence of epithelial cells on the original host button and the lack of evidence of epithelial downgrowth prior to penetrating keratoplasty.

The most likely explanation is that epithelial cells from the peripheral host cornea rim gained access to the posterior corneal surface after the graft was secured into the recipient opening. The complete absence of endothelial cells on the excised donor button indicates that the PGF occurred secondary to a diffuse endothelial cell injury while the corneoscleral button was in the preservative medium or at the time of penetrating keratoplasty. Interestingly, none of the identified risk factors for epithelial downgrowth, such as wound dehiscence, hypotony or a shallow anterior chamber, were observed.

Methods

DNA extraction

A 20 milligram formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue section from the failed corneal donor button was deparaffinized using xylene, and then treated with alcohol to remove the residual xylene. Protein digestion was performed with 40 μl of 20mg/ml proteinase K at 55°C for 12 hours. A silica-gel-membrane technology (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to isolate 50 μl of purified DNA product.

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for herpes simplex virus (HSV) I DNA was performed on the failed donor button, with a number of simultaneously performed positive and negative controls. Positive controls consisted of varied amounts of HSV I viral DNA (1, 10, 100 and 1000 copies), allowing quantification of the assay's sensitivity to HSV DNA present in the donor corneal button. DNA extracted from the cornea of a patient with keratoconus served as a negative control.

A previously described primer set was used for amplification of a 92bp HSV sequence: forward, 5'- CATCACCGACCCGGAGAGGGAC and reverse, 5'- GGGCCAGGCGCTTGTTGGTGTA1. These are regions of identity in the genomes of HSV types 1 and 2, and do not discriminate between these virus types [20-22]. PCR amplification was performed on a 100 μl final volume containing: 1 μl of 19.7mM of each primer (Biomolecular Research Center, University of California, San Francisco), 5 μl of the extracted DNA product, 10 μl of a 10X PCR Buffer (Sigma Chemical, Saint Louis, MO), 2 μl of 10mM deoxy nucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 10 μl of 25 mM of magnesium chloride, 2.5 μl of RedTaq DNA polymerase (Sigma Chemical), and 68.5 μl of water. Thermal cycling was performed in a GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the following program: initial denaturation for 2 min at 94°C, followed by 41 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, followed by a final extension for 2 minutes at 72°C. The PCR amplification products (10 μl) were separated on a 4% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

To confirm the presence of purified DNA extracted from the failed donor corneal button, previously published primers were used to perform PCR amplification of exon 12 of the TGFBI gene from the purified DNA product [23]. A mixture containing water in place of purified DNA served as a negative control.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Anthony J. Aldave, M.D. Assisted with care of the patient, coordinated performance of PCR for HSV DNA, wrote majority of the manuscript.

David A. Hollander, M.D., M.B.A. Assisted with manuscript preparation and revisions.

Bruno Branco, M.D. Performed PCR for HSV DNA and wrote description of methods for Material and Methods section as well as relevant portion of Results section.

Brooks Crawford, M.D. Performed histopathologic analysis and wrote description of methods for Material and Methods section as well as relevant portion of Results section.

Richard L. Abbott, M.D. Primary ophthalmologist for the patient. Performed initial and subsequent corneal transplants.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Supported by the AOS Knapp Fellowship Fund, Cleveland, OH (Dr. Aldave); Heed Foundation Fellowship Fund, Cleveland, OH (Dr. Hollander); a grant from CNPq-Brazil (Dr. Branco); and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the study.

Contributor Information

Anthony J Aldave, Email: aldave@jsei.ucla.edu.

David A Hollander, Email: Hollander@jsei.ucla.edu.

Bruno Branco, Email: bcbranco@uol.com.br.

Brooks Crawford, Email: Brooks@itsa.ucsf.edu.

Richard L Abbott, Email: rabbott@itsa.ucsf.edu.

References

- Chiou AG, Kaufman SC, Kaz K, Beuerman RW, Kaufman HE. Characterization of epithelial downgrowth by confocal microscopy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:1172–4. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(99)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder RS, Krachmer JH. The diagnosis of epithelial downgrowth after keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:697–703. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugar A, Meyer RF, Hood CI. Epithelial downgrowth following penetrating keratoplasty in the aphake. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:464–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450030106015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham GC, Bijwaard K, Sheng ZM, Hidayat AA, Font RL, McLean IW. Primary graft failure : a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2083–90. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00361-4. discussion 2090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham GC, Krafft AE, McLean IW. Herpes simplex virus in primary graft failure. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:586–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150588001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvar H, Brownstein S, Mintsioulis G, Chialant D, Punja K, Damji KF. Epithelial ingrowth following penetrating keratoplasty: a clinical, ultrasound biomicroscopic and histopathological correlation. Can J Ophthalmol. 2000;35:222–4. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(00)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazow ML, Stephens RW. An unusual complication after keratoplasty. Surv Ophthalmol. 1966;11:205–8. [Google Scholar]

- Karabatsas CH, Hoh HB, Easty DL. Epithelial downgrowth following penetrating keratoplasty with a running adjustable suture. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1996;22:1242–4. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(96)80076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz HM, Elliott JH, Boruchoff SA. Epithelization of the anterior chamber following penetrating keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;78:613–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980030615010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh MJ, Naumann GO. Cystic epithelial growth after penetrating keratoplasty: successful curative treatment by block excision. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:240. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.2.238b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearne MJ, Buckley RJ, Cree IA, Naumann GO. Cystic epithelial ingrowth as a late complication of penetrating keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1444–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.10.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Polack FM, Valenti J. Electron microscopic study of epithelial downgrowth after penetrating keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;65:374–82. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.5.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrys LA, Demong T. Epithelial downgrowth after penetrating keratoplasty. Can J Ophthalmol. 1982;17:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner MJ, Trentacoste J, Pon DM, Albert DM. Epithelial downgrowth: a 30-year clinicopathological review. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:6–11. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett T, D'Amico RA. Epithelial inclusion cyst of iris after keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;77:87–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(74)90611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz GH, D'Amico RA. Histopathology of corneal graft failures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66:184–99. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)92063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claoue C, Lewkowicz-Moss S, Easty D. Epithelial cyst in the anterior chamber after penetrating keratoplasty: a rare complication. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:36–40. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JD, Flaxman BA, Yanoff M. In vitro studies of corneal wound healing: epithelial-endothelial interactions. Invest Ophthalmol. 1974;13:575–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorski Z, Holbach L, Rummelt C, Gossler B, Naumann GO. Proliferation of corneal epithelial and endothelial cells in the trabecular region of human donor corneas in organ culture. Ophthalmic Res. 1990;22:51–6. doi: 10.1159/000267001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Xiao X, Egbert B, Darragh TM, Yen TS. Rapid detection of cutaneous herpes simplex virus infection with the polymerase chain reaction. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;92:391–2. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12277232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham ET, Jr, Short GA, Irvine AR, Duker JS, Margolis TP. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome – associated herpes simplex virus retinitis. Clinical description and use of a polymerase chain reaction – based assay as a diagnostic tool. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:834–40. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140048006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurumi T, Maeno K, Nishiyama Y. Nucleotide sequence of the DNA polymerase gene of herpes simplex virus type 2 and comparison with the type 1 counterpart. Gene. 1987;52:129–37. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munier FL, Korvatska E, Djemai A, Le Paslier D, Zografos L, Pescia G, Schorderet DF. Kerato-epithelin mutations in four 5q31-linked corneal dystrophies. Nat Genet. 1997;15:247–51. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]