Abstract

Influenza remains a serious issue for public health and it’s urgent to discover more effected drugs against influenza virus. Rhamnocitrin, as a flavonoid, its effect on influenza virus infection remains poorly explored. In this study, rhamnocitrin showed antiviral effect and anti-apoptosis on influenza virus A/Aichi/2/1968 (H3N2) in MDCK cells and A549 cells. In addition, molecular docking revealed that rhamnocitrin have good binding activity with the target proteins cGAS and STING, molecular dynamic simulation and surface plasmon resonance showed that rhamnocitrin could form a stable complex with the above proteins. Moreover, the qPCR and western blot assays further verified that rhamnocitrin could reduce type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines production by inhibiting the cGAS/STING pathway. Taken together, the results suggest that rhamnocitrin could be a potential anti-viral agent against influenza.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-79788-z.

Keywords: Rhamnocitrin, Influenza, cGAS, STING, Apoptosis, Anti-viral

Subject terms: Virtual drug screening, Pharmacology, Target identification, Virology, Influenza virus, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Drug discovery, Microbiology

Introduction

Influenza, an unpredictable pandemic that causes pneumonia that can be fatal, poses a risk to both human health and the broader economy1. The influenza virus stimulates host immunity and causes inflammatory factors to accumulate, leading to infection toxicity, which in turn causes acute lung damage that leads to death2. Although influneza A (H3N2) virus does not have high morbidity and mortality rates, statistical reports showed that it caused more hospitalizations and deaths in compared to influenza A (H1N1) virus and influenza B virus due to its high rate of antigenic change, which makes it adapt to evade host immunity3. A high rate of antigenic change of influenza virus also leads to high drug resistance and low vaccine effectiveness as well as stability. When the virus enters the cells, the host innate immunity will adapt the relevant programmed cell death (e.g. apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis) to prevent further invasion of the influenza virus4. However, viruses evolve, use a range of proteases in the host, and block corresponding metabolic methods to damage the cells in order to promote the cell death to replicate themselves5,6. Because of this, targeting host innate immunity and restoration of damage in cells may be a new strategy for preventing influenza virus infection.

Apoptosis is a programmed death that defends host cells against viral infection. As in the late stages of viral replication, the virus activates Caspase3 to promote apoptosis, allowing the daughter virus to be released and infect surrounding cells7. Then, the high level of apoptosis can prolong the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and IFN production, which can exacerbate lung tissue damage and aggravate viral infection2,8. Apoptosis is divided into two major pathways namely the extrinsic (DR pathway) and the intrinsic pathway (mitochondrial pathway)8. In the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, the disruption of mitochondrial membrane permeability will trigger the release of mtDNA and then activate the cyclic GMP-AMP synthesis (cGAS). In addition, cGAS, as a DNA sensor, not only could recognize host-derived DNA, but also could recognize non-self DNA, such as viral DNA, microbial DNA, and so on. Upon binding to DNA, cGAS would produce the second messenger cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), which is detected by the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) that is located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)9. Then STING would produce a battery of interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokine that accelerate the cell death and amplify the inflammation. Therefore, while cGAS and STING are crucial regulators of the innate immune response against infections, maintaining precise control over the activation of the cGAS/STING pathway during IAV infection is equally imperative. According to several studies, IAV upregulates USP18 expression, which enhances cGAS stability, leading to prolonged activation of the cGAS/STING pathway, thereby triggering apoptosis and promoting viral replication10. Moreover, IAV compromises mitochondrial integrity, resulting in the release of mtDNA into the cytosol, which activates both the cGAS/STING pathway and the NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby inducing pyroptotic cell death and exacerbating pneumonia11,12. Hence, identifying suitable drugs to target and regulate the cGAS/STING signaling pathway can help prevent further loss of control of the host upon pathogenic invasion.

Influenza is a seasonal disease belonging to the category of “plague” within the ancient Chinese science of warm diseases and could induce fever, cough, and other symptoms. It is reliable to excavate the potential monomers extracted from the traditional medicinal herbs and investigate the therapy effects of the monomers on the diseases that their original herbs usually treat on. For instance, isoliquiritigenin extracted from Glycyrrhiza spp. that is usually used in cough could activate NRF2 signaling pathway to perform antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects on influenza virus13. Rhamnocitrin (RH) is a flavonoid that can be extracted and isolated from many herbs14 such as Nervilia fordii (Hance) Schltr. (family Orchidaceae)15. As a medicinal herb, N. fordii has been generally used in traditional Chinese medicine as an antiviral or anti-inflammatory drug in the treatment of respiratory diseases, such as colds, coughs, and pneumonia16. Available data demonstrate that RH has a range of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antifibrosis, and anti-bacterial pharmacological properties14. With these different biological features, RH is assumed to act on a variety of molecular targets, including TGF-β1/Smads, SOCE/NFATc3, and miR-185/STIM-1 signaling pathways14. Nevertheless, the mechanism underlying the efficacy of RH on influenza A virus (IAV) has not been clarified. In the present research, RH exhibited significant anti-H3N2 activity in MDCK cells and A549 cells. And the molecular mechanism of RH on apoptosis in H3N2-infected A549 cells was also studied using molecular docking and dynamic simulation, and a subsequent validation of cGAS/STING and their downstream signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

RH (lot: HY-N1353) with 99.67% purity, oseltamivir acid (lot: HY-13318) with 98.6% purity, recombinant Human cGAS protein (HY-P71597) and STING protein (HY-P70700A) were purchased from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China). A 10 µM stock solution of RH and a 100 mM stock solution of oseltamivir acid were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at -20 °C before use.

Cells and viruses

A549 and MDCK cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Influenza virus strain A/Aichi/2/1968 (H3N2), A/PR/8/34 (H1N1)(PR8), A/Chicken/Guangdong/1996 (H9N2), A/California/04/2009 (H1N1)(CA04) were obtained from Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Guangdong, China). The viruses were inoculated in the allantoic cavities of 8-day-old chicken embryos at 37 °C for 48 h, and then the virus stock was dispensed and stored at -80 °C. By using the Reed-Muench method, the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of the viruses was calculated [H3N2 (TCID50 = 10− 5.67/100 µL), PR8 (TCID50 = 10− 7.5/100 µL), H9N2 (TCID50 = 10− 6.67/100 µL), CA04 (TCID50 = 10− 6/100 µL)]. All research procedures adhered to the rules outlined by the Laboratory Animal Center of Guangzhou Medical University and complied with animal protection legislation. The study received approval from the Guangzhou Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee (2022450).

Antibodies

GAPDH (#5174), Caspase9 (#9502), cleaved-Caspase9 (#9505), cGAS (#79978), IRF3 (#4302), phospho-IRF3 (#29047), TBK1 (#3504), phospho-TBK1 (#5483), Caspase3 (#9662), cleaved-Caspase3 (#9664), STING (#13647), NF-κB p65 (#8242), phospho-NF-κB p65 (#3033) antibodies and second antibody (#7074) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA).

Cell viability assay

MDCK and A549 cells were incubated with RH, and cell viability was determined via a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. Briefly, MDCK cells (2 × 104/well) and A549 cells (1 × 104/well) were grown to monolayer in 96-well plates at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Then, the MDCK cells and A549 cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for twice and were treated with two-fold serially diluted RH instead of medium for 48 h–24 h respectively. Additionally, following a 2 h infection of A549 cells with influenza virus (H3N2, PR8, CA04, H9N2), the cells were washed twice with PBS and subsequently incubated for 24 h with the appropriate concentration of RH, determined based on its non-toxic concentration. After 48 h–24 h of treatment, the cells were washed with PBS for twice, and the cells were incubated with 10 µL/well CCK-8 reagent for 2 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a full wavelength fluorescent enzyme labeling instrument (Thermo Fisher, USA).

Antiviral effect of RH in MDCK cells

To estimate the antiviral action of RH against H3N2, cytopathic effect (CPE) inhibition assay and plaque reduction assay under noncytotoxic concentrations of RH in DMEM/F12 containing 0.01% TPCK-trypsin were performed following virus infection17. Briefly, for CPE inhibition assay, MDCK cells were grown into a monolayer in a 96-well plate and incubated with 100 TCID50 of influenza virus H3N2 at 37 °C for 2 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS twice and treated with equivalent dilution concentrations of RH. After 48 h of incubation, the cells were stained with 1% CCK-8 reagent in medium. The optical density (OD) value of each well was measured, and the percentages of cell viability were calculated using the following formula: cell viability (%) = (OD450 for cells / OD450 for normal control cells) × 100%. And for plaque reduction assay, MDCK cells were grown into a monolayer in 6-well plates and incubated with influenza virus H3N2 (2.1 × 103 PFU/mL), PR8 (2.25 × 103 PFU/mL), CA04 (3.2 × 103 PFU/mL), H9N2 (2.7 × 103 PFU/mL) at 37 °C for 2 h, respectively. Cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated in maintenance medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1.5% agarose and 0.01% TPCK-trypsin), which contained equiploid dilutions of RH (100, 50, or 25 µM) and a positive control, oseltamivir acid (10 µM). Following 48 h of incubation, the agarose layer was removed, and the cells were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with 1% crystal violet. The plaques in each well were enumerated and visualized. The inhibition rate (%) was determined using the formula: Inhibition rate (%) = [1 - (plaque number of the treatment group/mean plaque number of the H3N2 control group)] × 100%. Additionally, MDCK cell apoptosis was assessed through fluorescence microscopy using an Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Briefly, MDCK cells were infected with influenza virus H3N2 for 2 h after reaching confluency in a 6-well plate, washed three times with PBS, and then incubated for 48 h in medium containing equal dilutions of RH and oseltamivir acid (DMEM/F12 with 0.01% TPCK-trypsin). After aspirating the cell supernatant, 1.5 mL of medium containing 60 µL of Annexin V-FITC conjugate, 2 µL of Annexin V-FITC, and 3 µL of propidium iodide (PI) staining solution was added to each well and incubated for 20 min at room temperature before being analyzed under a fluorescence microscope to measure fluorescence intensity.

Apoptosis assay in A549 cells

Following the manufacturer’s instruction, apoptosis was detected via flow cytometry using an annexin V apoptosis detection kit APC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). After the A549 cells grown into a monolayer in six-well plates, the cells were mock infected or infected with H3N2. After 2 h of incubation, the cell supernatants were discarded and the cells were washed with PBS for twice. The cells were then treated with RH (100, 50, 25 µM) or 1% DMSO in DMEM/F12 and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS and harvested into tubes. Next, the cells were resuspended with a binding buffer and stained with 5 µL of Annexin V eFluor™ 450 for 15 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the cell suspensions were treated with 5 µL of propidium iodide viability staining solution, and the stained cells were analyzed within 4 h using a LSRFortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated using FlowJo software.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection

Intracellular oxidative stress was determined using a ROS Assay Kit (Beyotime). Briefly, A549 cells were grown in 12-well plates for 24 h, followed by washing twice with PBS. Then, the cells were challenged with A (H3N2) viruses for 2 h. After washing the cells twice with PBS, they were treated with RH (100, 50, 25 µM) or 1% DMSO in DMEM/F12. After 24 h, the cells were washed and treated with 10 µM DCFH-DA for 20 min. Finally, the cells were washed thrice, and the strength of the fluorescence signal was observed time-dependently using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 135; Carl Zeiss, Oberochen, Germany).

Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, a mitochondrial membrane potential test kit with JC-1 (Solarbio, China) was used to measure mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). Briefly, RH (100, 50, 25 µM) or 1% DMSO in DMEM/F12 were applied to A549 cells cultured in 12-well plates, mock-infected, or infected with the H3N2 influenza virus. After 24 h, carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydranzone (CCCP; 15 µM) was incubated at 37 °C for 20 min with one of the wells containing mock-infected cells. Then, for 20 min at 37 °C, 1 mL of the JC-1 staining solution was applied to each well. CCCP was used as a positive control due to its ability to cause MMP decrease. Next, the cells were washed twice with an assay buffer. Afterwards, JC-1 fluorescence was immediately detected using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 135; Carl Zeiss).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) assay

TEM assay was used to observe the mitochondrial morphology of A549 cells. Briefly, A549 cells were cultured in 6-well plate and either mock-infected or infected with the H3N2 influenza virus. Following a 2 h incubation period, the cell supernatants were removed, and the cells were washed twice. The cells were then treated with RH (100 µM) or 1% DMSO in DMEM/F12 and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS and harvested and fixed with electron microscope fixing solution (G1102-100ML; Servicebio). After dehydration and staining, the samples were made into ultra-thin sections. Subsequently, the sections were analyzed by Hitachi TEM system.

Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation

Autodock Tools software version 1.5.6 was used to analyze the molecular interaction between cGAS (Protein Data Bank ID:6NAO) or STING (Protein Data Bank ID: 6MX3) and RH (PubChem CID: 5320946)18. Molecular docking mimics for target proteins were prepared by removing water and ligands from the original space structure prior to molecular docking. And the accuracy of docking was assessed by superimposing the lowest energy pose of the docked ligand onto the crystallized ligand and the RMSD was below 2 Å (supplementary Fig. 1). YASARA STRUCTURE version 20.7.4.W.64 was used to perform 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation, employing the AMBER14 force field19 and the TIP3P solvation model20. Following the refinement for the complexes, a simulation cell with periodic boundary conditions (298 K, pH 7.4, 0.9% NaCl) was established. Simulated annealing was implemented with a time step of 2.0 fs, and long-range electrostatic interactions (cutoff radius: 8.0 Å) were determined using the Particle Mesh Ewald algorithm21. Trajectories were sampled at intervals for 0 ns over 100 ns, and a comprehensive analysis table, encompassing the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) versus time plot, was generated within the YASARA interface. Discovery Studio 2019 (BIOVIA) software and Pymol were used for 2D and 3D visualizations and analysis of the docked complexes.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay

SPR assay was performed on a Biacore T200 instrument (Cytiva, Sweden) with CM5 sensor chip (BR100012, lot 10344853; Cytiva, Sweden). Recombinant Human cGAS protein and STING protein was first dissolved in the mixture (100 µL NHS, 100 µL EDC, and 150 µL Ethamolamine), and then were immobilized in parallel-flow channels of CM5 chip by using amine coupling kit (BR100050, Lot 35063; Cytiva, Sweden) with the parameter (Concentration of 30–50 µg/mL, PH 4.0, 25°C, flow velocity of 10 µL/min), respectively. Different concentration of RH were injected into the flow system with a association time of 120 s and a dissociation time of 300 s. Finally, the binding kinetics was analyzed by Biacore T200 Evaluation Software Version 3.0.12.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay

Primers for GAPDH, cGAS, STING, nucleoprotein of influenza virus (NP), IFN-β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and TNF-α genes (Table 1) were devised using the online primers of NCBI and were synthesized by BGI (Beijing, China). A549 cells (6 × 105/ well) were seeded into a six-well plate at 37 °C for 24 h, washed with PBS twice, and infected with virus for 2 h. The unbound viral inoculums were then discarded, and the cells were divided into five groups: normal control group (NC), virus-infected groups (H3N2), and three different RH concentration groups. The cells were harvested at 24 h. RNA extraction from each group and qPCR analysis were performed as previously described22.

Table 1.

Primer sequence for qPCR.

| Target gene | Direction | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| cGAS | Forward | AAGGATAGCCGCCATGTTTCT |

| Reverse | TGGCTTTCAGCAAAAGTTAGG | |

| STING | Forward | ATATCTGCGGCTGATCCTGC |

| Reverse | GGTCTGCTGGGGCAGTTTAT | |

| NP | Forward | GTGTGCAACCTGCATTTTCTGT |

| Reverse | CGTACTCCTCTGCATTGTCTCC | |

| IFN-β | Forward | GATGACCAACAAGTGTCTCCTCC |

| Reverse | GGAATCCAAGCAAGTTGTAGCTC | |

| IL-6 | Forward | CGGGAACGAAAGAGAAGCTCTA |

| Reverse | CGCTTGTGGAGAAGGAGTTCA | |

| IL-8 | Forward | CTTGGTTTCTCCTTTATTTCTA |

| Reverse | GCACAAATATTTGATGCTTAA | |

| MCP-1 | Forward | CAAGCAGAAGTGGGTTCAGGAT |

| Reverse | AGTGAGTGTTCAAGTCTTCGGAGTT | |

| TNF-α | Forward | AACATCCAACCTTCCCAAACG |

| Reverse | GACCCTAAGCCCCCAATTCTC | |

| GAPDH | Forward | GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC |

| Reverse | GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC |

Western blot assay

A549 cells were treated as described in the “Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay” section. Next, protein extraction from each group and western blot analysis were performed as previously described22.

Data analysis

Utilizing GraphPad Prism 9.0, all the data for this study were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 was used to determine significance in the one-way ANOVA analysis.

Results

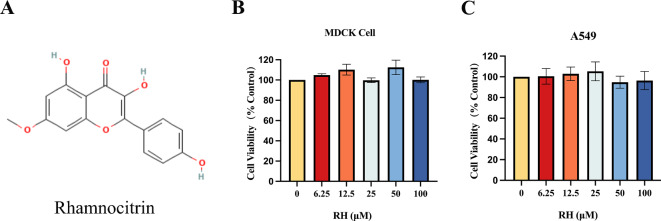

Effect of RH on cell cytotoxicity

To examine the noncytotoxic concentration of RH for following experiments, the sage concentration range was measured via CCK-8 assay after treating MDCK and A549 cells for 48 and 24 h, respectively. The CCK-8 assay results showed that RH was not cytotoxic in both cell line at a concentration of 100 µM (Fig. 1). Therefore, subsequent experiments were performed using an RH concentration of 100 µM.

Fig. 1.

Effect of RH on cell cytotoxicity. (A) The Chemical structure of RH; (B) MDCK and (C) A549 cells were incubated with different concentrations of RH (0-100 µM). MDCK and A549 cell viability after 48 and 24 h of treatment, respectively, were measured via CCK-8 assay. Data of three separate trials were given as the mean ± SD.

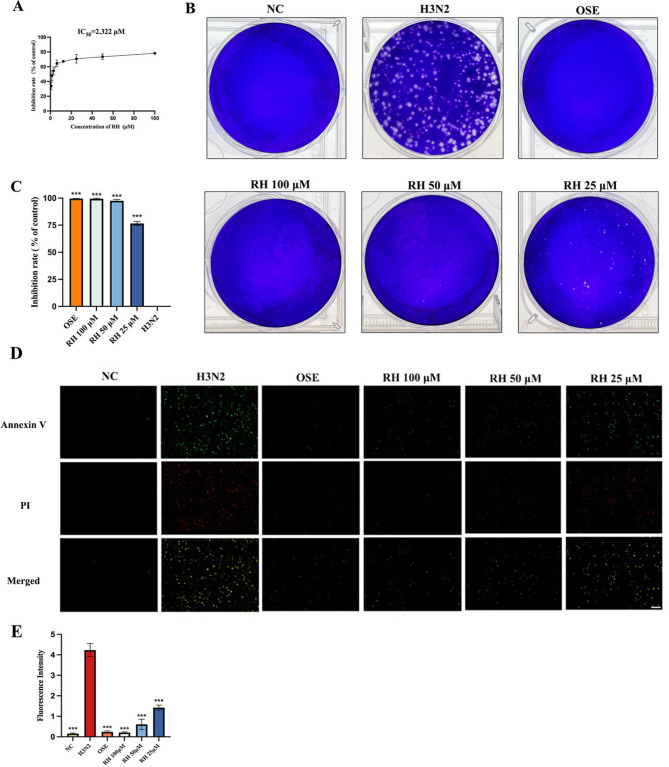

Inhibitory effects of RH on influenza a virus

MDCK cells show high susceptibility to influenza viruses and are extensively used to isolate and propagate influenza viruses23. In this study, MDCK cells were challenged with A (H3N2) virus and treated with equivalent dilution concentrations of RH or oseltamivir. The CPE inhibition assay results showed that the IC50 value of RH was 2.322 µM (Fig. 2A). And the results of plaque reduction assay of H3N2 showed that the plaque number in RH-treated cells was markedly reduced in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B,C). In addition, compared with oseltamivir, which is known to inhibit influenza viral replication and resulted in an inhibition rate of 99.58% ± 0.10%, the efficacy of three concentrations of RH was the approximate inhibition rate of 99.37% ± 0.55%, 97.58% ± 1.15%, and 76.60% ± 1.98%. RH has markedly inhibited the cell cytopathy (P < 0.001, compared with the cytopathy of DMSO-infected cells). Additionally, the results of the apoptosis assay in MDCK cells indicated that the influenza H3N2 virus markedly induced cell apoptosis. In contrast, RH significantly reduced H3N2-induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, showing effects comparable to those of oseltamivir (Fig. 2D,E). Furthermore, the plaque reduction and CPE assay results indicated that RH treatment significantly inhibited viral replication and release of additional influenza strains (PR8, H9N2, CA04) (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). The results indicate that RH effectively inhibits the replication and proliferation of the influenza A virus. What’s more, we observed that H3N2 induced more pronounced lesions in A549 cells compared to PR8, CA04, and H9N2, and RH exhibited a markedly weaker inhibition rate against H3N2 relative to the other viral strains (Supplementary Fig. 5B,C). These findings indicated that RH was significantly less effective in inhibiting H3N2 compared to the other three strains and it needed to be further explored in future studies.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effects of RH on influenza virus A/Aichi/2/1968 (H3N2) in MDCK cells. (A) The cytopathic inhibition assay was detected via calculated the cell viability; (B) The visualization of the plaque reduction assay; (C) The inhibition rate of the plaque reduction on each group. (D) Effects of RH on the apoptosis of H3N2-infected MDCK cells. Scale bar = 100 μm. (E) Quantitative analysis of the Annexin V (green) and PI (red) fluorescence intensity using ImageJ. Error bars indicate the range of values, and data of three separate trials were given as the mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001 vs. the H3N2 group.

RH suppressed A (H3N2) virus-induced apoptosis in A549 cells

To explore whether RH treatment could suppress A549 cells apoptosis induced by influenza virus H3N2, we utilized flow cytometry and western blot assay to detect the relevant indicators of apoptosis post-infection. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, the apoptosis of A549 cells was significantly triggered by H3N2 infection (percentages of apoptotic cells [18.66% ± 2.77%]; P < 0.001). Meanwhile, RH (100, 50, 25 µM) treatment greatly reduced apoptosis cells with the percentage of 7.83% ± 1.86% (P < 0.001), 9.87% ± 1.99% (P < 0.01) and 10.01% ± 2.04% (P < 0.01) respectively. Caspase9 serves as the initiator Caspase while Caspase3 functions as the effector Caspase in the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis24. In addition, Caspase3 activation is a critical event for efficient influenza virus propagation, while Caspase3 cleavage is a classic marker of virus-induced apoptosis7. As expected, the expression level of cleaved-Caspase9/Caspase9 and cleaved-Caspase3/Caspase3 in the H3N2 group increased (P < 0.001, Fig. 3C), whereas RH treatment (100, 50, or 25 µM) decreased this level (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 or P < 0.001, Fig. 3C). Subsequently, qPCR assay was employed to detect NP expression in each group, unveiling that RH significantly reduced NP mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner compared to the H3N2 group (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, Fig. 3D). These results showed that RH could not only inhibit the viral activity, but also reduce cell apoptosis by inhibiting Caspase9/Caspase3 axis following H3N2 infection.

Fig. 3.

Effects of RH on apoptosis of H3N2-infected A549 cells. (A) The effect of RH on apoptotic A549 cells infected with H3N2 virus for 24 h was detected by flow cytometry analysis. (B) Quantification of the percentages of apoptotic cells (including early and late apoptotic cells). (C) Protein expression of Caspase3 and Cleaved-Caspase3 (a), Caspase9 and Cleaved-Caspase9 (c) was analyzed via western blot assay. Quantitative analysis of Caspase3/Cleaved-Caspase3 (b) and Caspase9/Cleaved-Caspase9 (d) was performed using ImageJ. (D) Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression of the viral NP. Results of three separate trials were given as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the H3N2 group.

Effects of RH on ROS and MMP

Influenza virus damages the fitness and integrity of the mitochondria, which then results in increased oxidative stress and dissipation membrane potential, even inducing the intrinsic apoptosis25. Similarly, excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) further aggravates mitochondrial structural disruption26, thereby accelerating apoptosis. Here, we found that the A (H3N2) virus increased intracellular ROS compared with uninfected cells (P < 0.001; Fig. 4A) and that treatment of infected cells with RH (100, 50, 25 µM) markedly decreased the level of ROS (P < 0.001). Over-expression of ROS leads to the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential; thus, we further detected the expression of MMP. JC-1 is known to exist as a mitochondrial aggregation, and emits red fluorescence indicating the intact MMP in normal cells while JC-1 exists as a monomer emitting green fluorescence which indicates the collapse of MMP in the early apoptosis cell. As shown in Fig. 4B, both H3N2 and CCCP treatment directly impaired MMP compared with normal cells (P < 0.001). Of note, RH (100, 50, 25 µM) could repair the MMP of the infected cells (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001). These findings suggest that RH suppresses ROS production and mitigates MMP dissipation, thereby enhancing mitochondrial structural stability and subsequently reducing H3N2-induced cell apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

ROS overproduction and MMP dissipation induced by H3N2 were inhibited by RH. (A) (a) ROS expression was detected via DCFH fluorescence intensity. Scale bar = 100 μm. (b) The levels of ROS were analyzed using ImageJ. (B) (a) MMP expression was detected via JC-1 polymer fluorescence intensity. Scale bar = 20 μm. (b) JC-1 polymer levels were analyzed using ImageJ. Results of three separate trials were given as the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the H3N2 group.

RH protected mitochondrial structure from H3N2 damage

To further determine the effects of RH on mitochondrial structure of A549 cells infected with H3N2 virus, we used a transmission electron microscope to observed the ultrastructure changes of mitochondrial. As shown in Fig. 5, in the NC group, both the mitochondrial membrane and ridges of A549 cells were distinctly visible. Conversely, the H3N2 group exhibited significant structural damage to the mitochondria, characterized by swelling and vacuolar changes along with vanished cristae. However, those symptoms were less seen in the RH-treated group. These evidences further validated our hypothesis that RH has a protective effect on mitigating mitochondrial damage induced by the H3N2 influenza virus.

Fig. 5.

The mitochondrial ultrastructure changes in the NC group, H3N2 group and RH group (RH 100 µM). Scale bar = 5 μm, 2 μm, 500 nm (from left to right).

Detection of the structural interaction between RH and cGAS or STING

Given that the activation of the cGAS/STING pathway could significantly induce the cell apoptosis death9, we further employed molecular docking to validate the interaction between RH and cGAS or STING. The results showed that RH could combine with cGAS and STING, and the binding energy was − 7.70 kcal/mol and − 6.23 kcal/mol respectively (Fig. 6A and B). In RH-cGAS complex, we discovered three hydrogen interactions of RH with LEU-377, SER-378, and HIS-437 of cGAS, with distances of 4.0 Å, 3.1 Å, and 2.8 Å. And in RH-STING complex, there were two hydrogen interactions of RH with THR-263 and THR-267 of STING, with distances of 3.6 Å and 3.7 Å. It is known that the binding energy under − 5.0 kcal/mol indicates a good binding interaction between a ligand and receptor27, the docking results revealed that RH had the good binding interactions with the cGAS and STING. Next, we performed the molecular dynamics simulation to detect the stability of the formed complex. From 0 ns and 100 ns, the surface crystal structures of RH-cGAS or RH-STING complex interactions remained stable (Fig. 6). The RMSD plot revealed that the fluctuation range of the atoms of the ligand RH and the receptor cGAS or STING were below 2 Å. The results indicated that RH formed a stable complex with cGAS or STING. Subsequently, we used SPR assay to validate the accuracy of molecular docking. As shown in Fig. 6A-B(d), RH had significant binding signals with both cGAS and STING proteins in both groups with good concentration dependence. The kinetic data in the RH-cGAS group was close to the steady state fitting result and the equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) of RH-cGAS was 2.596 µmol/L. There was a weak non-specific signal in the RH-STING group with a slightly weaker steady state result and the KD of RH-STING was 6.748 µmol/L. Of note, the results of both groups all could be judged that RH specifically binds to cGAS and STING.

Fig. 6.

Detection of the structural interaction between RH and cGAS or STING. (A) Molecular docking and dynamic simulation of RH-cGAS interaction. (a) Three-dimensional ribbon structure of the RH-cGAS complex. (b) Surface simulation model of the RH-cGAS complex in 0 and 100 ns. (c) RMSD of all atoms of cGAS and RH. (d) The SPR binding dissociation curve of RH-cGAS complex. (B) Molecular docking and dynamic simulation of RH-STING interaction. (a) Three-dimensional ribbon structure of the RH- STING complex. (b) Surface simulation model of the RH-STING complex in 0 and 100 ns. (c) RMSD of all atoms of STING and RH. (d) The SPR binding dissociation curve of RH-STING complex.

The validation of the effects of RH on regulating the cGAS/STING signaling pathway after infection

To explore whether RH could regulate the cGAS/STING signaling pathway after the influenza virus H3N2 infection, we used qPCR and western blot assay to detect the expression of cGAS and STING. As shown in Fig. 7, the mRNA and protein levels of cGAS and STING in the H3N2 group were significantly higher than those of the NC group (P < 0.001). And compared with the H3N2 group, the mRNA and protein levels of cGAS and STING were markedly decreased in the three concentrations of RH group (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001). The results further verified that RH may interact with cGAS and STING as described in the above results of molecular docking and dynamic simulation. Meanwhile, RH had the suppressive effect on the cGAS/STING pathway, which may reduce the intrinsic apoptosis induced by H3N2.

Fig. 7.

RH inhibited the activation of the cGAS/STING pathway in A549 cells after H3N2 infection. Quantitative analysis of the mRNA expression of cGAS (A) and STING (C). (B and D) Protein expression of cGAS, STING was measured via western blot analysis (a) and was quantified by using Image J (b). Results of three separate trials were given as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the H3N2 group.

RH imroved cell viability and inhibited the expression of IFN-I and proinflammatory cytokines via down-regulating the activation of TBK1, IRF3 and NF-κB after H3N2 infection.

A549 cell viability post-H3N2 infection was assessed, and as anticipated, H3N2 significantly reduced cell viability, while RH substantially enhanced it in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8A). To investigate whether H3N2 virus could amplify the host inflammation while causing apoptosis, we used qPCR assays to detect the level of the type I IFN IFN-β and pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and TNF-α. After 24 h of viral infection, the mRNA expression of the above cytokines in the H3N2 group was markedly increased compared with that in the NC group (p < 0.001). Compared with the H3N2 group, the RH-treated group (100, 50, 25 µM) had significantly reduced expression of these cytokines (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 or P < 0.001; Fig. 8B). The results indicated that RH plays an effective role in virus-induced inflammation.

Fig. 8.

RH improved cell viability and inhibited IFN-I and proinflammatory cytokines production by inhibiting the phosphorylation of the TBK1, IRF3 and NF-κB in A549 cells following infection. (A) The cell viability was measured by CCK-8 assay. (B) mRNA expression levels of IFN-β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1and TNF- α were examined via qPCR analysis. (C) Protein expressions of TBK1, phosphp-TBK1, IRF3, phospho-IRF3, NF-κB P65, and phospho-NF-κB P65 were detected via western blot analysis and were quantified by using ImageJ. Results of three separate trials were given as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. the H3N2 group.

The above IFN-I and proinflammatory cytokines are the downstream genes transcribed by IRF3 and the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), which are the two transcription factors that are critically involved in viral infection28. And the above factors are activated since cGAS transmits through respective adaptor protein STING to recruit TBK129,30. Thus, we further explored the situation of the downstream pathway of the cGAS/STING pathway after infection. The results demonstrated that the expression levels of phospho-TBK1/TBK1, phospho-IRF3/IRF3 and phospho-NF-κB P65/ NF-κB P65 were significantly increased after H3N2 infection (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001). However, these levels obviously decreased in the RH treatment groups (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01 or P < 0.001; Fig. 8C). The results suggested that RH could inhibit the phosphorylation of TBK1, IRF3 and NF-κB by reducing the activation of the cGAS/STING pathway after infection.

Discussion

RH, a natural flavonoid present in many herbs such as N. fordii, had been reported for its beneficial properties, including anti-bacterial and antioxidant effects14. Due to its desirable pharmacological properties, we explored the potential effects of RH against influenza virus H3N2, which had not been reported before. This study has first identified that RH could not only inhibit influenza virus proliferation and replication, but also prominently suppress inflammation as well as apoptosis caused by the virus by inhibiting cGAS/STING signaling pathway in vitro. Initially, we employed CPE inhibition assay and plaque reduction assay, which were recognized as the standard for quantifying the virions and screening the potential virus inhibitors31, to investigate whether RH could reduce the viral titers. Surprisedly, RH showed a quality anti-viral replication comparable to NA inhibitor oseltamivir. Subsequently, we paid attention to revealing the deeper mechanism behind the anti-viral effects of RH.

Host innate immunity will adapt the relevant measures to prevent further invasion of the influenza virus, such as initiating apoptosis. Although apoptosis is critical to maintain the physical homeostasis, growing evidence suggests that it is inappropriate for numerous cells to undergo apoptosis induced by influenza virus, which will not only release the daughter virus, but also signal through excessive cytokines to recruit more immune cells, such as lymphocytes and macrophages, and then amplify host inflammation32,33. As expected, influenza virus H3N2 significantly replicated itself and promote the activation of Caspase9 and Caspase3 to execute the apoptosis as well as reduce the cell viability in A549 cells. Furthermore, H3N2 increased the production of type I IFN IFN-β and proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and TNF-α by initiating the phosphorylation of IRF3 and NF-κB P65. Type I interferon (IFN) response is known as a pivotal first line of host immune defense and a signature of virally infected cells30, and proinflammatory cytokines are known to promote the infected cells death. In addition, IRF3 is known as the important mediators for IFN response while NF-κB P65 is responsible for the production of proinflammatory cytokines, would cooperate to regulate the viral-induced inflammatory response34. The results further revealed that a regulated apoptosis is crucial for clearing pathogens and safeguarding the host, as an excessive apoptosis can result in tissue damage and disrupt normal function. Notably, these detrimental effects were markedly ameliorated by RH.

More and more evidences suggest that cGAS/STING pathway play an important role in antiviral innate defence system, which could regulate programmed cell deaths and the transcription of the type I IFN, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines9. The over-activation of cGAS/STING pathway could produce diverse inflammatory injuries35. And it had been found that IAV activates the cGAS/STING pathway, which promotes viral replication in A549 cells10 and exacerbates inflammation and tissue damage in the lungs of mice11. Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis of blood samples from influenza-infected patients and healthy individuals revealed that cGAS/STING expression levels were significantly elevated in influenza-infected patients (Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, inhibitors of the cGAS/STING pathway could be the valuable novel target therapies for pandemics caused by influenza virus. Molecular docking has become an powerful method for drug discovery, which could elucidate fundamental biochemical processes between the ligand and target protein36. And SPR is one of commonly used method to detect the binding interactions between small molecular and proteins with the advantage of being label-free, real-time, and sensitive37. With the help of molecular docking, dynamic simulation and SPR, we found that RH could steadily combine with the protein cGAS and STING at the atomic level. And we compared the docking results of RH with that of the current inhibitors of cGAS or STING (as shown in supplementary Fig. 1), we found that RH had the same binding sites as the docked inhibitors of the target proteins produced, which indicated that RH could be a potential molecular inhibitor that targets the cGAS/STING signaling pathway. Influenza viruses are negative-sense single-strand RNA viruses, which are usually thought to be recognized by RNA-sensing (MDA/RIG-I) pathway rather than DNA-sensing (cGAS/STING) pathway1. However, many investigations have discovered, that RNA virus infection also can cause the leakage of the mtDNA form the damaged mitochondria, which then activates the cGAS/STING system. For example, IAV would stimulate type I IFN production in a manner dependent on STING38, and cause cytosolic mtDNA release, which then activates cGAS39. As we all known, the mitochondria is a crucial organelle involved in a variety of cellular processes, such as oxidative phosphorylation, ATP production, autophagy, apoptosis, immunological response, and inflammation40. In addition, mitochondria, is the major production of ROS which is consisted of O2− and H2O241. Consistent with these findings, influenza virus H3N2 caused the overproduction of ROS, disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential, and destruction of mitochondrial structure, which then activated the cGAS/STING system in A549 cells. However, the elevated levels of the above indicators were inhibited by RH. In addition, we also found that the influenza virus upregulated the total protein content of TBK1 and promoted the phosphorylation of TBK1 whereas RH impeded the activation of TBK1 in a dose-dependent manner. TBK1, classically known as an activator of innate immunity, acts on a signaling intermediate downstream of cGAS/STING pathway and an upstream of IFN-I and inflammatory cytokines via IRF3 and NF-κB42,43, which strengthened the above speculation.

In summary, the excessive production of ROS, disruption of MMP, destruction of mitochondrial structure, and the hyperinduction of type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines, activated through the TBK1, IRF3 and NF-κB P65 signaling pathways, had been suggested to contribute to cell apoptosis after H3N2 infection, which subsequently damages tissue. These signaling pathways were associated with cGAS/STING innate system (Fig. 9). Notably, our findings confirmed that RH significantly inhibits the cGAS/STING pathway. This suggests that RH exerts anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, mitigating mitochondrial damage, preventing virus-induced apoptosis and viral replication by mainly inhibiting the cGAS/STING/TBK1/IRF3/NF-κB axis. In light of our finding, the molecular mechanism of RH may suggest a novel therapeutic approach for the management of influenza.

Fig. 9.

The potential mechanism underlying the alleviation of apoptosis and inhibition of viral replication by RH in response to influenza virus H3N2.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 8190140129), National Famous Old Chinese Medicine Experts Inheritance Studio Construction Project, National Chinese Medicine Human Education Letter [2022] No. 75 and Plan on enhancing scientific research in GMU (2024SRP079).

Author contributions

Zexing Chen: Writing - Original Draft, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Curation. Wanqi Wang: Writing - Original Draft, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Curation. Kefeng Zeng, Methodology, Data Curation. Jinyi Zhu: Methodology, Data Curation, Investigation. Xinhua Wang: Project administration, Funding acquisition. Wanyi Huang: Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Equal contributors

References

- 1.Krammer, F. et al. Influenza. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 4, 3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Short, K. R., Kroeze, E. J. B. V., Fouchier, R. A. M. & Kuiken, T. Pathogenesis of influenza-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 14, 57–69 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jester, B. J., Uyeki, T. M. & Jernigan, D. B. Fifty years of Influenza A(H3N2) following the pandemic of 1968. Am. J. Public. Health. 110, 669–676 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedoui, S., Herold, M. J. & Strasser, A. Emerging connectivity of programmed cell death pathways and its physiological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.21, 678–695 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downey, J., Pernet, E., Coulombe, F. & Divangahi, M. Dissecting host cell death programs in the pathogenesis of influenza. Microbes Infect.20, 560–569 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keshavarz, M. et al. Metabolic host response and therapeutic approaches to influenza infection. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett.25, 15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wurzer, W. J. Caspase 3 activation is essential for efficient influenza virus propagation. EMBO J.22, 2717–2728 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herold, S., Ludwig, S., Pleschka, S. & Wolff, T. Apoptosis signaling in influenza virus propagation, innate host defense, and lung injury. J. Leukoc. Biol.92, 75–82 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decout, A., Katz, J. D., Venkatraman, S. & Ablasser, A. The cGAS–STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol.21, 548–569 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang, L., Liu, X., Wang, C. & Shu, C. USP18 promotes innate immune responses and apoptosis in influenza a virus-infected A549 cells via cGAS-STING pathway. Virology. 585, 240–247 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lv, N. et al. Dysfunctional telomeres through mitostress-induced cGAS/STING activation to aggravate immune senescence and viral pneumonia. Aging Cell.21 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Mishra, S. et al. Innate immune sensing of influenza a viral RNA through IFI16 promotes pyroptotic cell death. iScience. 25, 103714 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, H. et al. Isoliquiritigenin inhibits virus replication and virus-mediated inflammation via NRF2 signaling. Phytomedicine. 114, 154786 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel, D. K. Biological importance and therapeutic benefit of rhamnocitrin: A review of pharmacology and analytical aspects. DMBL. 15, 150–158 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, T. et al. Rhamnocitrin extracted from Nervilia fordii inhibited vascular endothelial activation via miR-185/STIM-1/SOCE/NFATc3. Phytomedicine. 79, 153350 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie, J. et al. Structural characterization and immunomodulating activities of a novel polysaccharide from Nervilia Fordii. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.114, 520–528 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borges-Argáez, R. et al. In vitro evaluation of anthraquinones from Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) roots and several derivatives against strains of influenza virus. Ind. Crops Prod.132, 468–475 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem.30, 2785–2791 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier, J. A. et al. ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput.11, 3696–3713 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrach, M. F. & Drossel, B. Structure and dynamics of TIP3P, TIP4P, and TIP5P water near smooth and atomistic walls of different hydroaffinity. J. Chem. Phys.140, 174501 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieger, E. & Vriend, G. New ways to boost molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem.36, 996–1007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, Q. et al. Liushen Capsules, a promising clinical candidate for COVID-19, alleviates SARS-CoV-2-induced pulmonary in vivo and inhibits the proliferation of the variant virus strains in vitro. Chin. Med.17, 40 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takada, K. et al. A humanized MDCK cell line for the efficient isolation and propagation of human influenza viruses. Nat. Microbiol.4, 1268–1273 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahoo, G., Samal, D., Khandayataray, P. & Murthy, M. K. A review on caspases: Key regulators of biological activities and apoptosis. Mol. Neurobiol.60, 5805–5837 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.To, E. E. et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species contribute to pathological inflammation during influenza A virus infection in mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal.32, 929–942 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, Y. et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and their contribution in chronic kidney disease progression through oxidative stress. Front. Physiol.12, 627837 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, X. et al. Network pharmacology prediction and molecular docking-based strategy to explore the potential mechanism of Huanglian Jiedu decoction against sepsis. Comput. Biol. Med.144, 105389 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu, B. et al. Induction of INKIT by viral infection negatively regulates antiviral responses through inhibiting phosphorylation of p65 and IRF3. Cell. Host Microbe. 22, 86–98e4 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, S. et al. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science. 347, aaa2630 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perry, A. K., Chow, E. K., Goodnough, J. B., Yeh, W. C. & Cheng, G. Differential requirement for TANK-binding kinase-1 in type I interferon responses to toll-like receptor activation and viral infection. J. Exp. Med.199, 1651–1658 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidwell, R. W. & Smee, D. F. In vitro and in vivo assay systems for study of influenza virus inhibitors. Antiviral Res.48, 1–16 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanz-Garcia, C. et al. The non-transcriptional activity of IRF3 modulates hepatic immune cell populations in acute-on-chronic ethanol administration in mice. J. Hepatol.70, 974–984 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brydon, E. W. A., Morris, S. J. & Sweet, C. Role of apoptosis and cytokines in influenza virus morbidity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev.29, 837–850 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czerkies, M. et al. Cell fate in antiviral response arises in the crosstalk of IRF, NF-κB and JAK/STAT pathways. Nat. Commun.9, 493 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou, M. et al. Inhibition of cGAS-STING by JQ1 alleviates oxidative stress-induced retina inflammation and degeneration. Cell. Death Differ.29, 1816–1833 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng, X. Y., Zhang, H. X., Mezei, M. & Cui, M. Molecular docking: a powerful Approach for structure-based drug Discovery. CAD. 7, 146–157 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patching, S. G. Surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy for characterisation of membrane protein–ligand interactions and its potential for drug discovery. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Biomembr.1838, 43–55 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holm, C. K. et al. Influenza a virus targets a cGAS-independent STING pathway that controls enveloped RNA viruses. Nat. Commun.7, 10680 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, R. et al. Influenza M2 protein regulates MAVS-mediated signaling pathway through interacting with MAVS and increasing ROS production. Autophagy. 15, 1163–1181 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mills, E. L., Kelly, B. & O’Neill, L. A. J. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of immunity. Nat. Immunol.18, 488–498 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sies, H. & Jones, D. P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol.21, 363–383 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helgason, E., Phung, Q. T. & Dueber, E. C. Recent insights into the complexity of Tank-binding kinase 1 signaling networks: The emerging role of cellular localization in the activation and substrate specificity of TBK1. FEBS Lett.587, 1230–1237 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu, J. & Chen, Z. J. Innate Immune sensing and signaling of cytosolic nucleic acids. Annu. Rev. Immunol.32, 461–488 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.