Abstract

Background

Carbon dioxide is a potent cerebral vasodilator that may influence outcomes after ischemic stroke. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of intraprocedural mean end-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) levels on core infarct expansion and neurologic outcome following thrombectomy for anterior circulation ischemic stroke.

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted of consecutive patients from March 2020 to June 2021 who underwent mechanical thrombectomy for acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke under general anesthesia and achieved successful recanalization (Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction [TICI] ≥ 2b). Only patients with CT perfusion, procedural ETCO2, and postoperative MRI data were included. Segmentation software was used for multi-parametric image analysis. Normocarbia defined as mean ETCO2 of 35 mmHg was used to dichotomize subjects. Univariate and multivariate statistics were applied.

Results

Fifty-eight patients met criteria for analysis. Of these, 44 had TICI 3 recanalization, 9 had TICI 2c, and 5 had TICI 2b. Within this combined recanalization group, patients with mean ETCO2 > 35 had significantly higher rates of functional independence at 90 days. Although patients tended to salvage more penumbra and experience smaller final infarcts when ETCO2 exceeded 35 mmHg, this did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions

Stroke patients who underwent successful thrombectomy with general anesthesia achieved higher rates of functional independence when procedural ETCO2 exceeded 35 mmHg. Further studies to confirm this effect and investigate optimal ETCO2 parameters should be considered.

Keywords: Thrombectomy, carbon dioxide, stroke

Introduction

Ischemic stroke carries a tremendous public health burden with approximately 5.5 million global deaths annually and a 40% long-term disability rate. 1 Mechanical thrombectomy (MT) is a treatment option for select patients experiencing acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and involves endovascular retrieval of a thrombus associated with a large vessel occlusion. 2 Given the expanding case volume and accepted indications for MT, interest in optimizing recanalization techniques, including procedural sedation, has increased.

Mechanical thrombectomy is performed under conscious sedation, monitored anesthesia care (MAC) or general anesthesia (GA). To date, there are no data confirming the superiority of one technique over another, and practice patterns vary widely.3–5 GA enables more precise control over hemodynamic factors including carbon dioxide (CO2), a potent cerebral vasodilator.6–8 Takahashi et al. first reported that increasing CO2 levels may improve outcomes in MT by enhancing perfusion to the ischemic penumbra without detrimental steal toward healthy cerebral vasculature. 9

Given the sparse evidence regarding optimal CO2 parameters during thrombectomy, this preliminary study was undertaken to investigate the neuroprotective effect of CO2.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Electronic medical records were reviewed for consecutive patients from March 2020 to June 2021 at a Comprehensive Stroke Center who underwent successful mechanical thrombectomy for acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke. Success was defined as Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI) ≥ 2b. Subjects lacking pre-procedure CT perfusion (CTP), procedural end-tidal (ET) CO2 or post-procedure diffusion-weighted (DWI) MRI data were excluded. This evaluation and management paradigm reflects the study institution's routine clinical practice. TICI scores were independently graded by a blinded interventional neuroradiologist. RAPID software (2020 iSchemaView, Inc.) was used for cross-sectional image analysis and subsequently reviewed by a blinded diagnostic neuroradiologist to assess image quality. Patients whose imaging was compromised by poor contrast bolus or motion artifacts were also excluded. Additionally, patients with multiple thrombectomy procedures prior to obtaining post-procedural MRI were excluded.

Subjects were separated into two groups based upon an ETCO2 cutoff of 35 mmHg. 10 Descriptive statistics were applied to demographic data using, Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test (Mann–Whitney U test) for all continuous variables, and Chi-squared test for categorical variables to determine significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.05). Ischemic penumbra was calculated from CTP by subtracting infarct core (CBF <30%) from the volume of brain tissue harboring Tmax >6.0s ipsilateral to large vessel occlusion. Final infarct volume (apparent diffusion coefficient < 620 mm2/sec) was obtained from post-procedure MRI. 11

The radiographic outcomes of interest included the absolute difference in infarct volume between CTP and MRI as well as percentage of penumbra on CTP that subsequently infarcted on MRI, representing the volume of at-risk brain tissue that infarcted during attempted recanalization and despite successful reperfusion. Mean ETCO2 was also treated as a continuous variable, and a univariate regression analysis was performed to further assess the relationship between ETCO2 and the percentage of penumbra infarcted.

The primary clinical outcome was functional independence at 90 days, as determined by modified Rankin scale (mRS) ≤ 2. The clinical outcomes of the two groups based on ETCO2 were compared in a univariate fashion using a Chi-squared test. A multivariate logistic regression model was also constructed by including all factors that were independent predictors of functional independence at 90 days at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 based on Wilcoxon Rank-Sum and Chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. From this multivariate model, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

A subgroup analysis of the patients with TICI 3 recanalization was also performed. This subgroup was selected because DWI positivity would not be subject to variability based upon the volume of vascular territory that was not recanalized. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata/SE 16.1 software (2020 StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 60 patients were identified who underwent successful mechanical thrombectomy and possessed the requisite ETCO2, CTP and DWI data. Of these, 2 were excluded for re-occlusion prior to obtaining MRI with subsequent return to angiography suite for re-do thrombectomy. This left 58 patients for analysis among whom 44 experienced TICI 3 recanalization, 9 TICI 2c and 5 TICI 2b.

Mean procedural ETCO2 met or exceeded 35 mmHg in 35 of the 58 subjects composing the study population. Basic demographic information for these patients, along with presenting glucose level, NIHSS score, time from last known well to recanalization, stroke etiology, number of passes and mean intra-procedural systolic blood pressure (SBP) are listed in Table 1. The two groups were similar with the exception of age; the patients with mean CO2 greater than 35 were, on average, younger, and this was statistically significant (p = 0.019).

Table 1.

Demographic information TICI2b/2c/3.

| Mean CO2 ≤ 35 (n = 23) | Mean CO2 > 35 (n = 35) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70.7 (13.7) | 61.2 (15.8) | 0.019 |

| Female sex | 11 (47.8%) | 15 (42.9%) | 0.710 |

| Race | 0.239 | ||

| White | 19 (82.6%) | 23 (67.6%) | |

| Black | 4 (17.4%) | 11 (32.4%) | |

| Received tPA | 8 (34.8%) | 11 (31.4%) | 0.428 |

| Admission Glucose (mg/dl) | |||

| Admission NIHSS | 14.7 (5.3) | 14.1 (5.2) | 0.655 |

| Last known well to recanalization time (min) | 129.3 (28.0) | 118.0 (33.6) | 0.188 |

| Etiology | 0.371 | ||

| Crypotgenic | 9 (40.9%) | 12 (34.3%) | |

| Large vessel disease | 5 (22.7%) | 11 (31.4%) | |

| Cardioembolic | 8 (36.4%) | 9 (25.7%) | |

| Hypercoagulability | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.9%) | |

| ICAD | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.7%) | |

| Number of thrombectomy passes | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.9 (0.9) | 0.281 |

| Mean SBP (mmHg) | 140.7 (11.3) | 136.5 (19.5) | 0.050 |

| Mean end-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 31.7 (2.0) | 38.7 (3.8) |

Reported as mean (SD) or n (%).

significance level of p = 0.05.

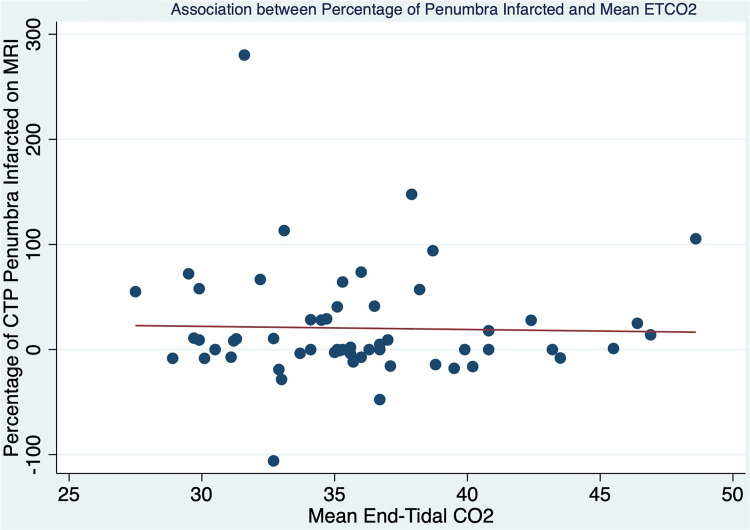

The volumetric CTP and MRI data for these groups are listed in Table 2. The groups presented with similar-sized penumbra on CTP although those with higher CO2 tended to exhibit smaller average core infarcts on both CTP and MRI. Core infarct volume and percentage of penumbra that progressed to infarction were statistically similar between the two groups. When ETCO2 was held as a continuous variable, there was not a significant linear relationship with the percentage of penumbra infarcted (r2 = 0.0007, p = 0.845; Figure 1).

Table 2.

Volumetric CTP/DWI: TICI 2b/2c/3.

| Mean CO2 ≤ 35 (n = 23) | Mean CO2 > 35 (n = 35) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTP core (ml) | 24.5 (33.3) | 12.4 (20.0) | 0.132 |

| CTP penumbra (ml) | 114.9 (59.2) | 129.9 (75.9) | 0.520 |

| DWI core (ml) | 54.3 (88.6) | 25.5 (37.5) | 0.326 |

| Core difference (ml) | 29.7 (71.6) | 13.1 (42.5) | 0.394 |

| % penumbra infarcted | 26.0 (69.8) | 16.6 (39.8) | 0.489 |

Reported as mean (SD).

Figure 1.

Association between percentage of penumbra infarcted and mean ETCO2.

However, the patients with ETCO2 greater than 35 had higher rates of functional independence at 90 days (72.7%, compared to 35.0%, p = 0.007). Premorbid mRS was not different between these groups (p = 0.417). There were two additional factors found to be independent predictors of functional independence: age (p = 0.010) and number of passes (p = 0.038). On multivariate logistic regression incorporating these covariates, patients with ETCO2 greater than 35 had a higher likelihood of functional independence (OR 3.97, 95% CI 1.07–14.8, p = 0.040).

There were 44 patients included in the TICI 3 subgroup analysis, 28 of whom had mean end-tidal CO2 greater than 35. Subjects with mean ETCO2 greater than 35 were younger, on average (p = 0.014). There were no other significant differences in demographics, admission glucose or NIHSS, time from last known well to recanalization, stroke etiology, number of passes or intraprocedural mean systolic blood pressure between these two groups (Table 3). There was also no statistically significant difference between these two groups in mean CTP core or penumbra volume (Table 4). Final infarct volume and percentage of penumbra that progressed to infarction were lower in the ETCO2 > 35 group, but these differences were not statistically significant. When mean ETCO2 was treated as a continuous variable, univariate regression showed a nonsignificant inverse correlation between ETCO2 and percentage of penumbra that progressed to infarction (r2 = 0.0295, p = 0.265). There was also a higher rate of functional independence at 90 days in the group with the higher ETCO2 (76.9%, compared to 28.6%, p = 0.003) and no difference in premorbid mRS (p = 0.362).

Table 3.

Demographic information, TICI 3.

| Mean CO2 ≤ 35 (n = 16) | Mean CO2 > 35 (n = 28) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.1 (11.8) | 61.3 (16.1) | 0.014 |

| Female sex | 7 (43.8%) | 12 (42.9%) | 0.954 |

| Race | 0.279 | ||

| White | 13 (81.3%) | 18 (66.7%) | |

| Black | 3 (18.7%) | 9 (33.3%) | |

| Received tPA | 6 (37.5%) | 10 (35.7%) | 0.393 |

| Admission Glucose (mg/dl) | 116.1 (20.4) | 119.5 (41.5) | 0.961 |

| Admission NIHSS | 15.1 (3.5) | 14.7 (5.4) | 0.870 |

| Last known well to recanalization time (min) | 516.3 (353.5) | 510.0 (330.5) | 0.691 |

| Etiology | 0.733 | ||

| Crypotgenic | 7 (43.8%) | 11 (39.3%) | |

| Large vessel disease | 2 (12.4%) | 6 (21.4%) | |

| Cardioembolic | 7 (43.8%) | 9 (32.1%) | |

| Hypercoagulability | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) | |

| ICAD | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) | |

| Number of thrombectomy passes | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.7 (0.9) | 0.196 |

| Mean SBP (mmHg) | 140.4 (10.0) | 134.7 (14.1) | 0.092 |

| Mean end-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 31.3 (2.0) | 38.2 (3.4) |

Reported as mean (SD) or n (%).

significance level of p = 0.05.

Table 4.

Volumetric CTP/DWI: TICI 3.

| Mean CO2 ≤ 35 (n = 16) | Mean CO2 > 35 (n = 28) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTP core (ml) | 18.1 (19.0) | 14.9 (21.7) | 0.429 |

| CTP penumbra (ml) | 118.4 (53.5) | 141.3 (74.4) | 0.278 |

| DWI core (ml) | 40.8 (54.8) | 18.8 (28.3) | 0.361 |

| Core difference (ml) | 22.8 (46.6) | 3.9 (33.5) | 0.347 |

| % penumbra infarcted | 18.2 (38.0) | 8.1 (30.2) | 0.456 |

Reported as mean (SD).

Discussion

No consensus exists regarding optimal physiologic parameters in patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. Specifically, the benefit of induced hypertension and hypercarbia is uncertain. 12 General anesthesia not only affects cerebral blood flow and metabolism in several ways but also allows for more precise modulation through pharmacologic agents and mechanical ventilation. 9 Recent randomized clinical trials have demonstrated no significant difference in outcome based on the use of GA versus conscious sedation during MT.13–15 However, anesthetic induction and maintenance were highly controlled in these studies, with no significant variations in blood pressure or ETCO2 regardless of the level of sedation used. These variables are less reliably regulated without controlled protocols in real-world clinical settings.

Lower mean ETCO2 levels among patients undergoing MT with GA have been associated with worse outcomes. 9 The above results support this conclusion, as a mean ETCO2 ≤ 35 mmHg during thrombectomy was associated with significantly less functional independence at 90 days. Furthermore, subjects with lower ETCO2 tended to infarct a larger percentage of penumbra, although this finding was not statistically significant. As a potent vasodilator, CO2 may enhance collateral circulation to brain tissue at risk in acute ischemic stroke, retarding the progression of ischemic penumbra to complete infarction. However, care must be taken to address resultant systemic hypotension, which may counteract any beneficial effect of CO2 on brain collaterals.

Although the therapeutic potential of CO2 is attractive, this study contains several limitations. It is a single-institution retrospective design with a small sample size. Although the higher end-tidal CO2 group tended to have both better clinical and radiographic outcomes, these mostly did not reach statistical significance. It is possible the study was not sufficiently powered to detect statistical differences in the radiographic outcomes of this heterogeneous population. An optimal ETCO2 level cannot be determined based upon these results. A randomized prospective trial is necessary to further investigate the impact of mean ETCO2 on thrombectomy outcomes in order to better guide perioperative care.

Conclusion

Stroke patients who underwent successful thrombectomy with general anesthesia achieved higher rates of functional independence when procedural ETCO2 exceeded 35 mmHg. Further studies to confirm this effect and investigate optimal ETCO2 parameters should be considered.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Matthew S Parr https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1135-1159

Jesse G A Jones https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2682-9736

References

- 1.Donkor ES. Stroke in the 21(st) century: a snapshot of the burden, epidemiology, and quality of life. Stroke Res Treat 2018; 2018: 3238165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mundiyanapurath S, Schonenberger S, Rosales ML, et al. Circulatory and respiratory parameters during acute endovascular stroke therapy in conscious sedation or general anesthesia. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015; 24: 1244–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta R. Local is better than general anesthesia during endovascular acute stroke interventions. Stroke 2010; 41: 2718–2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abou-Chebl A, Lin R, Hussain MS, et al. Conscious sedation versus general anesthesia during endovascular therapy for acute anterior circulation stroke: preliminary results from a retrospective, multicenter study. Stroke 2010; 41: 1175–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Froehler MT, Fifi JT, Majid A, et al. Anesthesia for endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 2012; 79: S167–S173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahiri S, Schlick K, Kavi T, et al. Optimizing outcomes for mechanically ventilated patients in an era of endovascular acute ischemic stroke therapy. J Intensive Care Med 2017; 32: 467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dony P, Dramaix M, Boogaerts JG. Hypocapnia measured by end-tidal carbon dioxide tension during anesthesia is associated with increased 30-day mortality rate. J Clin Anesth 2017; 36: 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi CE, Brambrink AM, Aziz MF, et al. Association of intraprocedural blood pressure and end tidal carbon dioxide with outcome after acute stroke intervention. Neurocrit Care 2014; 20: 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laiwalla AN, Ooi YC, Van De Wiele B, et al. Rigorous anaesthesia management protocol for patients with intracranial arterial stenosis: a prospective controlled-cohort study. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e009727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilela P, Rowley HA. Brain ischemia: CT and MRI techniques in acute ischemic stroke. Eur J Radiol 2017; 96: 162–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019; 50: e344–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schonenberger S, Mohlenbruch M, Pfaff J, et al. Sedation vs. Intubation for Endovascular Stroke TreAtment (SIESTA)—a randomized monocentric trial. Int J Stroke 2015; 10: 969–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henden P L, Rentzos A, Karlsson JE, et al. General anesthesia versus conscious sedation for endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke: the AnStroke trial (anesthesia during stroke). Stroke 2017; 48: 1601–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simonsen CZ, Sorensen LH, Juul N, et al. Anesthetic strategy during endovascular therapy: general anesthesia or conscious sedation? (GOLIATH - general or local anesthesia in intra arterial therapy) A single-center randomized trial. Int J Stroke 2016; 11: 1045–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]