Abstract

Introduction

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is an uncommon but fatal cause of stroke worldwide. Endovascular treatments could be life-saving in patients who don't treat with anticoagulants as a mainstay of treatment. Currently, there is no consensus considering the safety, efficacy, and also selected approaches of endovascular intervention for these patients. This systematic review evaluates the literature on endovascular thrombolysis (EVT) in CVST patients.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted through PubMed and Scopus databases between 2010 and 2021, with additional sources identified through cross-referencing. The primary outcomes were the safety and efficacy of EVT in CVST, including catheter-related and non-catheter-related complications, clinical outcomes, and radiological outcomes.

Results

A total of 10 studies comprising 339 patients were included. Most of the patients presented with headaches (86.72%) and/or focal neurologic deficits (45.43%) (modified Rankin Scale of 5 in 55.88%). Acquired coagulopathy and/or consuming estrogen/progesterone medication were the most frequent predisposing factors (45.59%). At presentation, 68.84% had multi-sinus involvement, and 28.90% had venous infarcts and/or intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). The overall complication rate was 10.3%, with a 2.94%, 1.47%, and 1.17% rate of ICH, herniation, and intracranial edema, respectively. The complete and partial postoperative radiographic resolution was reported in 89.97% of patients, increasing to 95.21% during the follow-up. Additionally, 72.22% of patients had no or mild neurologic deficit at discharge, rising to 91.18% at the last follow-up. The overall mortality rate was 7.07%.

Conclusions

EVT can be an effective and safe treatment option for patients with refractory CVST or contraindications to systemic anticoagulation.

Keywords: “Sinus thrombosis, intracranial”, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, cerebral venous thrombosis, mechanical thrombolysis, endovascular thrombolysis, endovascular treatments, venous stroke, CVST

Introduction

Stroke is one of the main public health concerns in the world and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) is an uncommon but fatal cause of cerebral infarction, accounting for approximately 0.5–1% of all strokes, with a higher prevalence in developing countries.1,2 Genetic and acquired prothrombotic conditions are two main predisposing factors for developing CVST. 2 Underlying inflammatory or infectious processes and using contraceptives are some of the prothrombotic conditions that can predispose a person to CVST, which is well reflected in the fact that 75% of the reported CVST cases occur in young women of childbearing ages.3,4 Other predisposing conditions include deficiencies of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III, antiphospholipid syndrome, prothrombin G20210A mutation, factor V Leiden mutation, etc. 2

Based on the anatomical location of the thrombus, involvement of the brain parenchyma, and the time interval between the onset of symptoms and receiving the treatment, patients with CVST (PwCVST) could present with a variety of symptoms, including new-onset headache, as well as other signs of intracranial hypertension, seizures, focal neurological deficits (FNDs), and altered mental status.5,6 CVST prognosis has significantly improved throughout the years, and the mortality rate has dropped to less than 15% in the modern era.6,7 The main prognostic factors of poor recovery in PwCVST include older age (> 37 years old), male sex, altered mental state, presence of FNDs, associated cerebral deep venous thrombosis, intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), posterior fossa lesions, malignancy, and infections.5,6,8,9

Performing a safe recanalization is the primary purpose of treatment. 10 According to the existing data, the first treatment choice is systemic anticoagulation, which is associated with clinical improvement. 11 However, extensive thromboses are less likely to resolve with systemic anticoagulants. About one-third of patients with aggressive CVST might remain unresponsive to conventional treatments or even experience a deteriorative course. 12 Endovascular treatments, including endovascular thrombolysis (EVT) and mechanical thrombectomy (MT) procedures, are alternative options in the event of failure to respond to anticoagulation or in patients with a high probability of a poor outcome.3,13–15 These patients might benefit from these approaches at early stages to rapidly recanalize the thrombosed sinuses, resulting in improved functional outcomes. 16 The primary objective of this systematic review was to provide comprehensive information regarding the safety and efficacy of EVT for CVST management, according to the available literature.

Material and methods

Search strategy

A systematic review was performed under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline (available at http://www.prisma-statement.org). A thorough search was carried out through PubMed and Scopus databases from January 2010 to November 2021—with additional sources identified through cross-referencing—to find studies assessing PwCVST who underwent EVT. Medical subject headings (MeSH) and terms in the title(s)/ abstract(s)/ keyword(s) were used by the following keywords: “cerebral venous sinus thrombosis,” “cerebral venous thrombosis,” “thrombolytic therapy,” and “mechanical thrombolysis.” We investigated all relevant clinical trials, cohorts, and cross-sectional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were investigated to ascertain the inclusion and exclusion criteria established before review. Studies that met the following criteria were included: clinical trials, cohorts, and cross-sectional, human studies, written in English regarding the adult and adolescent patients with acute CVST who underwent EVT alone (without MT) and were followed up with clinical and/or radiological outcomes.

Studies with the following features were excluded: (a) focusing on general aspects of CVST management, (b) patients treated with other types of endovascular treatments or a combination of ET with MT, (c) patients underwent adjuvant treatment procedures such as craniotomy, (d) patients aged≤ 10 years, (e) patients with chronic CVST, (F) animal studies, and (g) studies with insufficient data on both the clinical and radiologic follow-up, and (h) the letters, case reports, case series with less than ten patients, and review articles.

This review excludes studies in which patients received ET ± MT (including balloon-assisted thrombectomy, stent retriever thrombectomy, aspiration thrombectomy, rheolytic catheter thrombectomy, etc.), and where it was not possible to separate the data for those who only received EVT. It should be noted that the study of Andersen et al. reported 28 PwCVST who received endovascular interventions, of whom 17 patients received EVT alone. 4 Since, in this study, information on those 17 patients was included in our systematic review. A similar approach was implemented for the study of Yakovlev et al. 17

Evaluation method and data extraction

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts according to the research protocol, and if deemed relevant, the second round of screening was subsequently conducted by reviewing the full papers. In the case of disagreement between the two authors, a third investigator was consulted. The primary outcomes included the safety and efficacy of EVT in PwCVST, including (a) catheter-related complications: groin hematoma, catheter displacement, and vascular punctures; and non-catheter-related complications: new or worsening ICH, cerebral herniation, intracranial edema, cerebral infarction, venues sinus re-thrombosis, and cardiovascular events (b) clinical outcomes (CVST recurrence, functional outcomes at discharge and during the follow-up according to the patients’ modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores, and overall mortality rate), and (c) radiological outcomes (CVST recurrence, and postoperative and follow-up radiographic resolution of CVST). CVST recurrence was defined as the presence of both clinical and radiologic evidence of re-thrombosis during follow-up. The overall mortality rate was defined as early mortality in the acute phase of the disease or long-term mortality during the follow-up related to the underlying CVST.

Other extracted information included (a) first author's name, (b) year of publication, (c) sample size, (d) patients’ age, (e) predominant participants’ sex, (f) predisposing factors, (g) initial manifestations of CVST, (h) the duration between symptoms’ onset the diagnosis of CVST, (i) the duration between diagnosis and receiving EVT, (j) initial mRS, (k) mRS at discharge, and (l) follow-up mRS scores.

Given the nature of the studies and the heterogeneity of the reported outcomes, performing a meta-analysis and applying statistics were impossible.

Endovascular technique

The reported endovascular approach for EVT in the studies was described as: The femoral artery was punctured for this EVT approach and a diagnostic digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was used to evaluate the venous outflow pathways and confirmation of the thrombosed cerebral sinuses. After that, the involved venous sinus, using a right transfemoral vein approach, was catheterized. A guiding catheter was placed into the involved sinus and the microcatheter was placed into the distal end of the thrombosed sinus under the guidance of a guidewire. Continuous thrombolytic drugs were administered into the cerebral venous by microcatheter (intra-sinus infusion of 1–2 mg/h alteplase) and then repeat DSA was performed after 12–24 h. Systematic heparin was administrated after the procedure.18,19

Results

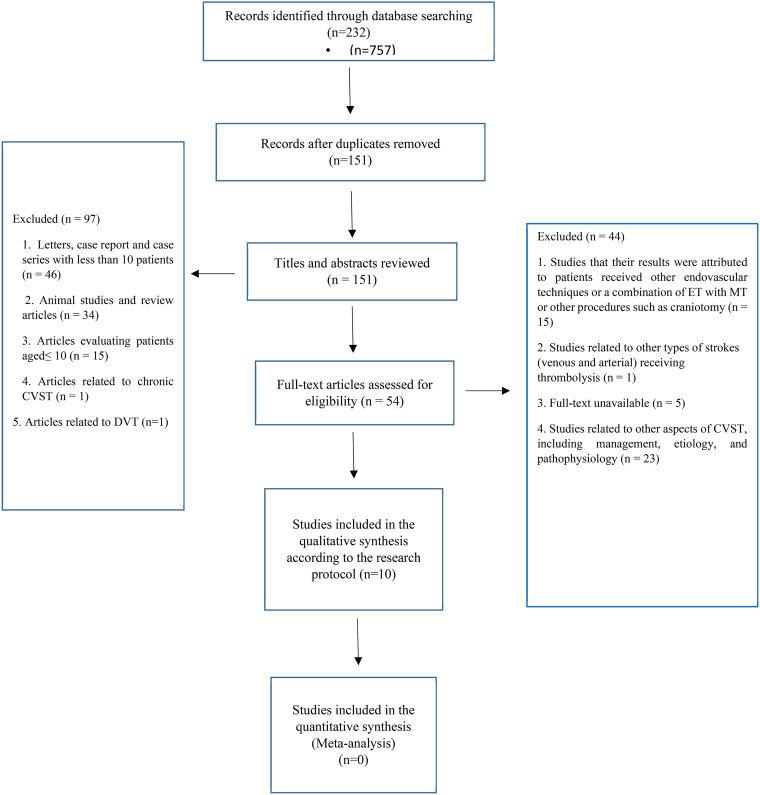

Searches of the databases and reference lists identified 232 articles, of which 177 studies were excluded after removing the duplicates (n = 81) and reviewing the titles/abstracts (n = 97). Subsequently, 54 full-text articles were evaluated, of which 44 articles were excluded for the following reasons: studies in which patients were treated with MT or a combination of MT and ET, as well as patients who underwent other therapeutic interventions (such as craniotomy), studies with unavailable full-texts or insufficient data, and studies related to other aspects of CVST such as general management, etiology, and pathophysiology (Figure 1). Eventually, ten full-text articles were included in this systematic review. Studies varied in size from 10 to 156 patients, and a total number of 339 patients with acute CVST who received EVT were evaluated for each research question. Notably, MT was combined with EVT in three studies, of which only patients who received EVT alone were included in this study.4,17,20 Tables 1 and 2 demonstrate the baseline characteristics of PwCVST, as well as the treatment characteristics extracted from the studies. Figure 2 presents an overview of findings.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the selection process for the studies included in the analyses of endovascular thrombolysis for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) flow diagram; CVST: cerebral venous sinus thrombosis; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; ET: endovascular thrombolysis; MT: mechanical thrombectomy.

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics of patients with CVST treated with endovascular thrombolysis.

| Author Year |

sample size | Age (year) Median [IQR] Mean ± SD (Range) |

Sex Female (%) |

Underlying risk factors N (%) |

Initial symptoms to diagnosis (days/ hours) Median [IQR] Mean ± SD (Range) |

Clinical presentations N (%) |

Initial mRS (score) N (%) |

Initial GCS (score) Median [IQR] Mean ± SD (Range) |

Imaging findings N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al. (2021) 3 | 28, of whom 17 received ET alone | 38 [28.5–49.5] | 13 (76.4) |

|

4 d [2.0–6.5] |

|

NA | 9.0 [7.5–12.5] |

|

| Kumar et al. (2010) 21 | 19 | 32 )17–46( |

11 (57.9) |

|

NA |

|

NA | NA |

|

| Mathukumalli et al. (2016) 19 | 24 | 30.5 (16–70) |

12 (50) |

|

4 d (2–45) |

|

|

NA |

|

| Mohammadian et al. (2012) 22 | 26 | 35.5 ± 10.8 (18–56) |

20 (77) |

|

NA |

|

NA | NA |

|

| Qiu et al. (2021) 23 | 40 | 37.9 ± 14.6 (16–67) |

17 (42.5) |

|

7 d (3–360) |

|

NA | NA |

|

| Yakovlev et al. (2014) 16 | 16, of whom 12 received ET alone | 34.58 (15–66) |

8 (66.66) |

|

7.91 (4–15) d |

|

NA | NA |

|

| Yue et al. (2010) 17 | 28, of whom 6 received ET alone | 38 ± 13 (22–57) |

4 (66.66) |

|

19.5 d (1–65) |

|

NA | 6.5 [4.0–10.0] |

|

| Garge et al. (2014) 18 | 10 | 41.4 (26–60) | 6 (60) |

|

(8–48) h |

|

|

NA |

|

| Guo et al. (2019) 20 | 156 | 32 ± 5 (14–68) | 119 (76.3) |

|

NA |

|

NA | NA |

|

| Baddam et al. (2016) 15 | 29 | 36.5 [19–54] |

12 (41.4%) |

|

(12–72) h |

|

NA | 8 (5–11) |

|

NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; h: hour; d: day; m: month; mRS: modified Rankin scale; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; ET: endovascular thrombolysis; ICH: intracranial hemorrhage; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; OCP: oral contraceptive pill; HRT: hormone replacement therapy; APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; FND: focal neurologic deficit.

Table 2.

The profile of endovascular treatment in patients with CVST.

| Author | Diagnose to procedure (days/ hours) Median [IQR] Mean ± SD (Range) |

Procedural adverse event N (%) |

Initial scan recanalization N (%) |

Follow-up scan recanalization N (%) |

Follow-up (month/ year) Median [IQR] Mean ± SD (Range) |

mRS at discharge (score) N (%) |

Follow-up mRS (score) N (%) |

Mortality N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (2021) 3 | <1 d: 11 (64.7) <1.5 d: 2 (11.7) <2 d: 4 (23.6) |

|

|

|

(3–6) m | NA | Three months

|

5 (29.41) |

| Kumar et al. (2010) 21 | 28 h (6–54h) |

|

|

|

6.3 m (6–8) |

|

|

3 (15.7) |

| Mathukumalli et al. (2016) 19 | 2 d (3 h–12 d) |

|

|

|

6 m |

|

|

4 (16.67) |

| Mohammadian et al. (2012) 22 | NA |

|

|

|

10.0 ± 5.9 m (3–23) |

NA | Third week

|

0 (0) |

| Qiu et al. (2021) 23 | Median: 0d (0–6 d) |

|

|

|

(3–6) m | NA |

|

2 (5) |

| Yakovlev et al. (2014) 16 N = 16 | NA |

|

|

NA | (1–3) y (N = 7) |

NA | NA | 0 (0) |

| Yue et al. (2010) 17 | NA |

|

|

NA | 3 m | NA |

|

1 (16.66) |

| Garge et al. (2014) 18 | NA |

|

NA | NA | 1 m | NA |

|

1 (10) |

| Guo et al. (2019) 20 | NA |

|

|

|

6 m (n = 116) |

|

6 months

|

7 (4.48) |

| Baddam et al. (2016) 15 | NA |

|

|

|

1 months 6 months |

NA | 1 month

|

1 (3.4) |

NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; h: hour; d: day; m: month; mRS: modified Rankin scale; ICH: intracranial hemorrhage.

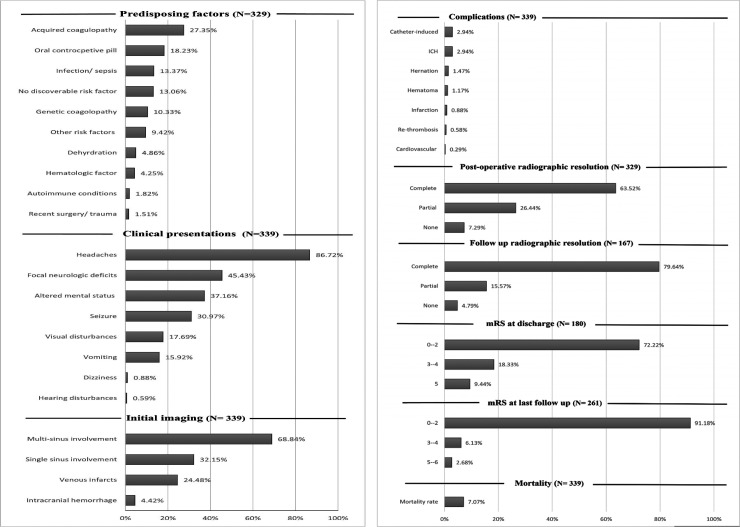

Figure 2.

The main values of the patients with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. ICH: Intracranial hemorrhage.

Baseline characteristics of PwCVST receiving EVT

Demographic features

Among the 339 PwCVST, most of the patients (222, 65.48%) were female, and the mean age was 35.63 years.

Predisposing factors

The data on the underlying risk factors were missing in the Garge et al. literature. 22 The major predisposing factors were (a) acquired coagulopathy states (27.35%, 90/329), including puerperium (post-partum period of about six weeks after childbirth), pregnancy, hormonal therapy, and the nephrotic syndrome, (b) consuming oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) (18.23%, 60/329), (c) infections and sepsis (13.37%, 44/329), and (d) genetic coagulopathies (10.33%, 34/329). Other risk factors observed in PwCVST included the following: dehydration (4.86%, 16/329), hematologic factors such as cancers, anemia, and polycythemia (4.25%, 14/329), autoimmune states (1.82%, 6/329), recent surgery or trauma (1.51%, 5/329), and other less common causes (9.42%, 31/ 329). Notably, no specific risk factor was found in 13.06% of the patients (43/329).

The duration between initial manifestations and CVST diagnosis

The interval between the occurrence of the initial symptoms and diagnosis of CVST was different in the studies. The shortest and most extended reported periods were 8–48 h 20 and 45 days, 21 respectively. In three studies, there were no data about the duration between initial manifestations and diagnosis.18,23,24

Clinical presentations

The most common clinical presentation was headaches, reported in 86.72% of the patients (294/339). Other major reported symptoms included focal neurologic deficits (FNDs) (45.43%, 154/339), altered mental status (37.16%, 126/339), seizure (30.97%, 105/339), visual disturbances (17.69%, 60/339), vomiting (15.92%, 54/339), dizziness (0.88%, 3/339), and hearing disturbances (0.59%, 2/339).

The results of initial imaging studies

Single-sinus involvement and multi-sinus involvement (≥ 2) were reported in 32.15% (109/339) and 68.84% (230/339) of patients, respectively. In the study of Yue et al., there was no single sinus involvement, and all patients 7 had more than one sinus involvement. Venous infarcts and ICH were evident before the administration of thrombolytic treatment in 24.48% (83/339) and 4.42% (15/339) of patients, respectively.

Initial mRS scores

mRS is a valuable instrument in stroke settings with acceptable reliability and validity for assessing functional outcomes. 23 The scores of the initial mRS of PwCVST were 0–2 (normal to the mild deficit) in 8.82%, 3–4 (mode deficit) in 35.29%, and 5 (severe deficit) in 55.88% of patients, respectively21,22 (Table 1; Figure 2).

Treatment characteristics and safety of EVT

The duration between CVST diagnosis and receiving EVT

According to the studies, the time between diagnosis and receiving EVT varied from 6 h to 12 days.4,21,23,25

Complications following EVT

Complications of EVT were divided into catheter-induced and non-catheter-induced complications. The catheter-induced complications, including groin hematoma, catheter displacement, and punctures, were reported in 2.94% of the patients (10/339). Non-catheter-induced complications were found in 7.37% (25/339) of the patients, with the most frequent including ICH (2.94%), herniation (1.47%), intracranial edema (1.17%), infarction (0.88%), re-thrombosis (0.58%), and cardiovascular events (0.29%).

Efficacy of EVT

Postoperative radiographic resolution

The data on the imaging resolution was missing in the Garge et al. study. 22 Based on the initial scans to evaluate recanalization, 63.52% (209/329) of patients achieved complete thrombosis resolution, and 26.44% (87/329) of patients attained partial resolution. However, no evidence of recanalization was observed in 7.29% of patients (24/329), of whom nine patients (37.5%) died during hospitalization.24,25

Follow-up radiographic resolution

A total of 171 patients were radiologically followed up, of whom recanalization was not assessed in two patients, and two patients died during the follow-up.4,24,25 The imaging scans demonstrated complete recanalization of CVST in 79.64% of cases (133/167) and partial recanalization in 15.57% (26/167). Moreover, recanalization failed in 4.79% of patients (8/167).

CVST recurrence

CVST recurrence was reported only in the Yakovlev et al. study, in which two patients developed recurrence. 17 The CVST recurrence was missing in other studies.

Neurologic outcome and mortality rate

The discharge mRS and follow-up mRS were reported for 180 and 261 patients, respectively.4,16,18,20–22,24,25 At discharge, 72.22% (130/180) of patients had no or mild neurological deficits (mRS = 0–2), 18.33% (33/180) had moderate neurological deficits (mRS = 3–4), and 9.44% (17/180) had severe neurological deficits (mRS = 5). At the last follow-up, 91.18% (238/261) of patients had mRS = 0–2, 6.13% (16/ 261) had mRS = 3–4, and 2.68% (7/ 261) developed severe neurological deficits or death (mRS = 5–6). It should be noted that Kumar et al. investigated the clinical outcome based on the following mRS categories: 0–1, 2, and 3–6. They demonstrated that 15/19 patients (78.94%) had good or partial improvement (mRS = 0–2) at discharge, and 4/ 19 (21.05%) had a poor response. At the last follow-up, 14 patients had no or mild deficit, and the data of the other two patients were missing. 23

The overall mortality rate was estimated to be 7.07% (24/339). Of note, two studies did not report any deaths17,18 (Table 2; Figure 3).

Discussion

The primary aim of our systematic review was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EVT in PwCVST. Most of the patients presented with headaches and/or FNDs with the severe deficit. Acquired coagulopathy and/or consuming OCP were the most frequent predisposing factors. More than half of the patients had multi-sinus involvement at presentation with severe neurologic deficits. The overall complication rate, including catheter and non-catheter-induced, was 10.3%, with a 2.94% rate of ICH. The post-procedure complete and partial radiographic resolution was reported in 89.97% of patients, increasing to 95.21% during the follow-up time. However, it should be noted that follow-up data were not thoroughly reported in some studies. Additionally, 72.22% of patients had no or mild neurologic deficit at discharge, increasing to 91.18% at the last follow-up. The overall mortality rate was 7.07% (24/339).

Anticoagulation is the mainstay of treatment of acute and subacute CVST to recanalize the occluded sinuses/veins, prevent thrombus propagation, treat the underlying prothrombic state, and eventually improve patients’ outcomes.10,26 Given the increasing use of endovascular treatments, including EVT or MT, in recent years, they might be considered alternative therapeutic choices for patients with acute CVST who develop progressive neurologic deterioration despite adequate anticoagulation with heparin. 10 However, regarding the limited data, there is still no consensus considering the benefits of these endovascular approaches over systemic anticoagulation 10 ; the European Stroke Organization (ESO) guideline does not provide a recommendation on EVT for PwCVST, 27 while the American Heart Association (AHA) guideline recommends considering EVT in patients who deteriorate despite anticoagulant treatment. 3 A recent randomized clinical trial (RCT), namely the Thrombolysis or Anticoagulation for Cerebral Venous Thrombosis RCT, compared functional outcomes of PwCVST who were treated with standard medical care (control group) and those who received a combination of endovascular treatments (consisted of MT, EVT, or both) with standard medical care (intervention group). 28 According to the authors, endovascular treatments in comparison with standard medical care did not improve the functional outcome of PwCVST, which had at least one poor prognostic factor. In addition, they found no significant difference in the mortality rate, new symptomatic ICH, major hemorrhagic complications, and serious adverse events (except for seizure) between the intervention and control groups. 28 However, since the trial had an insufficient sample size and was prematurely halted, the possibility of some beneficial effects in some patients cannot be excluded. 10

Currently, there is a broad consensus that anticoagulation is safe to use in PwCVST, even in those with ICH at manifestation. 10 The risk of ICH following anticoagulation in PwCVST is relatively low (<5%). 10 We found a similar hemorrhagic transformation rate of 2.94% among patients receiving EVT. However, a systematic review regarding the safety of EVT in CVST conducted in 2010 indicated more than double the ICH rate among patients receiving EVT; they found a 10% rate of major bleeding and a 7.6% rate of ICH. They also reported a mortality rate of 9.2%, 29 which is higher than the results of our study based on the literature published after 2010 (7.07%). These findings could be attributed to improved clinical awareness, the advancement of neuroimaging techniques, the development of therapeutic management, a shift in risk factors, etc. 7 A 2018 systematic review indicated an overall recanalization rate of 77–85% (both partial and complete) among patients treated with anticoagulation. 30 Our study revealed a higher overall recanalization rate of 89.97–95.21%. With the advances in diagnosis and treatment, CVST generally has a favorable outcome, with a higher rate of functional recovery.10,31 The International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVST) of 624 PwCVST, most of whom (83.3%) were treated with anticoagulation, reported an overall death or dependency rate (mRS = 3–6) of 13.4% which is higher than that in our study on PwCVST treated with EVT (8.81%). Of note, only 2.1% of the ISCVST study patients were treated with local ET. 6

These findings suggested that, despite poorer prognosis and more severe disease progression in PwCVST who were included for EVT, their outcomes may be comparable to those of PwCVST in general. A recent analysis of the data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample—the largest all-payer inpatient healthcare database in the United States—a healthcare mortality rate of 12.40% among patients who received EVT, which is higher than the mortality rate of 7.07% was obtained from the current study. 32 This study included 1248 patients treated with endovascular treatments, of whom 682 received EVT alone. The authors suggested that after adjusting for age and CVST-associated complications (to reduce the potential treatment selection bias), endovascular treatment was associated with an increased risk of mortality compared to medical management. Nevertheless, they reported that EVT was not independently associated with poor discharge outcomes.32,33

Taking all into account, the results of the present review suggest that EVT is beneficial and safe for PwCVST. However, our work has some limitations. First, there are concerns regarding bias in reporting the outcomes, together with publication bias and under-reporting of patients with poor outcomes or severe complications. 10 Second, the results of this study were mainly based on cohort and cross-sectional studies with relatively small sample sizes, limiting its generalizability to draw a firm conclusion considering EVT in PwCVST. Additionally, some of the vital information regarding the efficacy of EVT, including CVST recurrence, were not provided in a considerable number of studies.

Conclusion

This study reported results from 10 studies on PwCVST who underwent EVT. Most patients tend to have worse initial status, with multi-sinus involvement and severe neurologic deficits. Despite the poor baseline characteristics, the current systematic review indicated that functional independence was achieved by approximately 70–90% of patients, with procedural complications and an ICH rate of <10%. As a result, EVT is an effective and safe therapy for patients with refractory disease or contraindications to systemic anticoagulation. This Alternative treatment option can be considered a reliable life-saving treatment for eligible PwCVST. To thoroughly assess the outcomes of EVT for CVST, prospective trials with sufficient sample sizes and longer duration will be required. Furthermore, it seems that it is time for a large and credible head-to-head trial to compare the efficacy of EVT with systemic anticoagulation in the PwCVST who have the same presentation.

Key points

Anticoagulation is the mainstay of the treatment of venous sinus thrombosis (CVST).

Endovascular treatments (EVT) are an alternative therapeutic choice for patients with CVST who develop progressive neurologic deterioration despite anticoagulation.

There is no consensus considering the safety and efficacy of EVT over systemic anticoagulation.

EVT seems to be a relatively effective and safe therapy for CVST.

Prospective trials with sufficient sample sizes and longer duration will be required to assess the outcomes thoroughly.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Ali Emami https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8005-3529

Melika Jameie https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2028-9935

Ehsan Sharifipour https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5793-3288

Reza Mohamadian https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3325-9601

References

- 1.Aghaali M, Yoosefee S, Hejazi SAet al. A prospective population-based study of stroke in the central region of Iran: the Qom Incidence of Stroke Study. Int J Stroke 2022; 17: 957-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bousser M-G, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. The Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD, Jr, et al. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011; 42: 1158–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen TH, Hansen K, Truelsen T, et al. Endovascular treatment for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis–a single center study. Br J Neurosurg 2021; 35: 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dentali F, Gianni M, Crowther MAet al. et al. Natural history of cerebral vein thrombosis: a systematic review. Blood 2006; 108: 1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferro JM, Canhão P, Stam Jet al. et al. Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke 2004; 35: 664–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutinho JM, Zuurbier SM, Stam J. Declining mortality in cerebral venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Stroke 2014; 45: 1338–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goyal G, Charan A, Singh R. Clinical presentation, neuroimaging findings, and predictors of brain parenchymal lesions in cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: a retrospective study. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2018; 21: 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilyas A, Chen C-J, Raper DM, et al. Endovascular mechanical thrombectomy for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: 1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferro JM, Canhão P. Cerebral venous thrombosis: Treatment and prognosis. Waltham MA: UpToDate, Apr 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medel R, Monteith SJ, Crowley RWet al. et al. A review of therapeutic strategies for the management of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Neurosurg Focus 2009; 27: E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coutinho J, de Bruijn SF, Deveber Get al. et al. Anticoagulation for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 8: CD002005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einhäupl K, Stam J, Bousser MG, et al. EFNS Guideline on the treatment of cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in adult patients. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17: 1229–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang S, Hu Y, Li Z, et al. Endovascular treatment for hemorrhagic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: experience with 9 cases for 3 years. Am J Transl Res 2018; 10: 1611. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siddiqui FM, Dandapat S, Banerjee C, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in cerebral venous thrombosis: systematic review of 185 cases. Stroke 2015; 46: 1263–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baddam SR, Pamidimukkala V, Vemuri Ret al. et al. Local intrasinus thrombolysis for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2016; 9: 49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yakovlev SB, Bocharov AV, Mikeladze Ket al. et al. Endovascular treatment of acute thrombosis of cerebral veins and sinuses. Neuroradiol J 2014; 27: 471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammadian R, Sohrabi B, Mansourizadeh R, et al. Treatment of progressive cerebral sinuses thrombosis with local thrombolysis. Interv Neuroradiol 2012; 18: 89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SK, Mokin M, Hetts SWet al. et al. Current endovascular strategies for cerebral venous thrombosis: report of the SNIS Standards and Guidelines Committee. J Neurointerv Surg 2018; 10: 803–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yue X, Xi G, Zhou Zet al. et al. Combined intraarterial and intravenous thrombolysis for severe cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2010; 29: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathukumalli NL, Susarla RM, Kandadai MR, et al. Intrasinus thrombolysis in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: experience from a university hospital, India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2016; 19: 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garge SS, Shah VD, Surya Net al. et al. Role of local thrombolysis in cerebral hemorrhagic venous infarct. Neurol India 2014; 62: 521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Rajshekher G, Reddy CRet al. et al. Intrasinus thrombolysis in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: single-center experience in 19 patients. Neurol India 2010; 58: 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo X, Sun J, Lu Xet al. et al. Intrasinus thrombolysis for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: single-center experience. Front Neurol 2019; 10: 1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu M-J, Song S-J, Gao F. Local thrombolysis combined with balloon dilation for patients with severe cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Chin Med J 2021; 134: 573–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coutinho JM, Stam J. How to treat cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Haemostasis 2010; 8: 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferro JM, Bousser M-G, Canhão P, et al. European Stroke organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis–endorsed by the European academy of neurology. Euro Stroke J 2017; 2: 195–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coutinho JM, Zuurbier SM, Bousser M-G, et al. Effect of endovascular treatment with medical management vs standard care on severe cerebral venous thrombosis: the TO-ACT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2020; 77: 966–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dentali F, Squizzato A, Gianni M, et al. Safety of thrombolysis in cerebral venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 2010; 104: 1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguiar de Sousa D, Lucas Neto L, Canhão Pet al. et al. Recanalization in cerebral venous thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2018; 49: 1828–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulivi L, Squitieri M, Cohen Het al. et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis: a practical guide. Pract Neurol 2020; 20: 356–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddiqui FM, Weber MW, Dandapat S, et al. Endovascular thrombolysis or thrombectomy for cerebral venous thrombosis: study of nationwide inpatient sample 2004–2014. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2019; 28: 1440–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banks JL, Marotta CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke 2007; 38: 1091–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]