Abstract

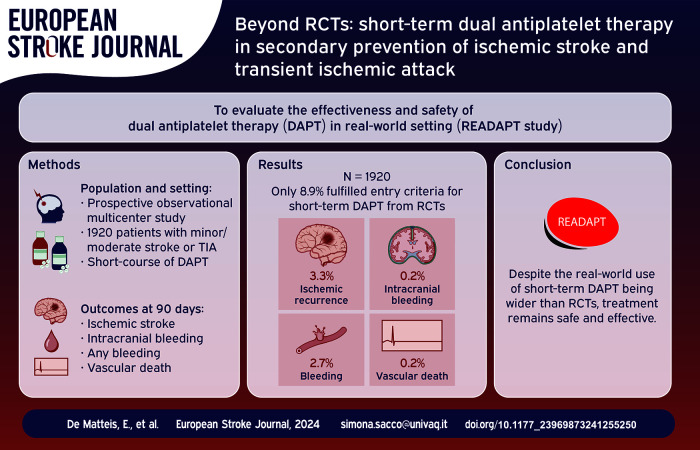

Background and purpose:

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) proved the efficacy of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in secondary prevention of minor ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA). We aimed at evaluating effectiveness and safety of short-term DAPT in real-world, where treatment use is broader than in RCTs.

Methods:

READAPT (REAl-life study on short-term Dual Antiplatelet treatment in Patients with ischemic stroke or Transient ischemic attack) (NCT05476081) was an observational multicenter real-world study with a 90-day follow-up. We included patients aged 18+ receiving short-term DAPT soon after ischemic stroke or TIA. No stringent NIHSS and ABCD2 score cut-offs were applied but adherence to guidelines was recommended. Primary effectiveness outcome was stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or death due to vascular causes, primary safety outcome was moderate-to-severe bleeding. Secondary outcomes were the type of ischemic and hemorrhagic events, disability, cause of death, and compliance to treatment.

Results:

We included 1920 patients; 69.9% started DAPT after an ischemic stroke; only 8.9% strictly followed entry criteria or procedures of RCTs. Primary effectiveness outcome occurred in 3.9% and primary safety outcome in 0.6% of cases. In total, 3.3% cerebrovascular ischemic recurrences occurred, 0.2% intracerebral hemorrhages, and 2.7% bleedings; 0.2% of patients died due to vascular causes. Patients with NIHSS score ⩽5 and those without acute lesions at neuroimaging had significantly higher primary effectiveness outcomes than their counterparts. Additionally, DAPT start >24 h after symptom onset was associated with a lower likelihood of bleeding.

Conclusions:

In real-world, most of the patients who receive DAPT after an ischemic stroke or a TIA do not follow RCTs entry criteria and procedures. Nevertheless, short-term DAPT remains effective and safe in this population. No safety concerns are raised in patients with low-risk TIA, more severe stroke, and delayed treatment start.

Keywords: Dual antiplatelet therapy, ischemic stroke, TIA, aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor

Graphical abstract.

Introduction

Minor ischemic strokes and high-risk transient ischemic attacks (TIA) account for half of all cerebrovascular ischemic events1,2 and are associated with a 4% risk of ischemic recurrences at 90 days.3–5 The cornerstone of secondary prevention of these conditions is short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). RCTs proved that DAPT is superior to single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) in reducing the risk of cerebrovascular ischemic recurrences when at its maximum.6–9 Indeed, DAPT was associated with a number needed to treat of 29 patients to prevent a recurrent stroke in CHANCE 6 and 92 to prevent a composite primary outcome event in THALES. 8 According to POINT, DAPT prevents 15 ischemic events for every 1000 patients receiving the treatment. 7

Few real-world studies have addressed effectiveness and safety of short-term DAPT in ischemic stroke.10–17 Most of these studies were retrospective, had limited sample sizes, and exhibited heterogeneity in outcomes.10–17 Notably, the real-world use of DAPT has increased since the publication of the RCTs, 18 but still around half of the eligible patients does not receive the treatment yet19,20 and there are disparities in treatment prescription according to gender, ethnicity, and cause of the index event. 18 Conversely, physicians occasionally prescribe DAPT to patients with non-minor stroke19,21 or who do not follow RCTs procedure. 21 Benefit/risk profile of DAPT in these patients has not been assessed yet.

Given the lack of evidence on DAPT in patients outside RCTs boundaries and setting, the REAl-life study on short-term Dual Antiplatelet treatment in patients with ischemic stroke or Transient ischemic attack (READAPT) study aimed at evaluating effectiveness and safety of DAPT in a multicenter real-world setting, where treatment use has proven wider that RCTs. 21 The study also aimed at addressing the subgroups of patients who do not meet entry criteria for RCTs due to a more severe ischemic stroke or low risk TIA, as well as those who do not follow RCTs procedures regarding time to DAPT start or antiplatelet loading dose.

Materials and methods

Study methodology has been previously reported 21 and is briefly summarized here. The READAPT (NCT05476081) is an observational prospective multicenter real-world study endorsed by the Italian Stroke Association (ISA-AII) and adherent to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. 22 The Internal review Board of the University of L’Aquila – the coordinating center – approved the study with the number 03/2021 in February 2021 and ethic committees of each participating center subsequently cleared it. All included patients or their proxies signed an informed consent. Between February 2021 and February 2023, 64 Italian centers (Supplemental Table S4) enrolled all consecutive patients treated with DAPT. Patients were included shortly after the index event (i.e., baseline) and had a 90-day follow-up, which concluded with a face-to-face or remotely end of study visit.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included inpatients or outpatients with non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA, older than 18 years, who were treated with short-term DAPT. We did not set rigid entry criteria based on NIHSS or ABCD 2 score to reflect the real-world use of short term DAPT. Nevertheless, we recommended adherence to guidelines criteria to use short-term DAPT.23–26 Key exclusion criteria were DAPT prescription after endovascular stenting procedures and participation to interventional RCTs on stroke prevention.

Study procedures and data collection

Physicians chose DAPT regimen – loading dose and treatment duration – and the antiplatelet to be continued after DAPT cessation according to the best clinical practice and guidelines23–26 (Supplemental Method 1.1).

To characterize index and ischemic recurrences, we collected symptom duration and findings at neuro-imaging examination that was performed in all included patients. For both index and recurrent ischemic events, we referred to the World Health Organization (WHO) time-based criterion 27 to distinguish ischemic strokes from TIAs. For the severity of bleeding events, we referred to the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO). It is worth noting that severe bleedings included hemorrhagic strokes but excluded asymptomatic hemorrhagic transformations of ischemic brain infarctions, which were not encompassed by this severity classification. 28 Details on variable collected and definitions of the other outcomes are in Supplemental Method 1.2.

We used electronic anonymized baseline and follow-up case-report-form (Supplemental Method 1.2) created with the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software,29,30 which was hosted at University of L’Aquila. The study staff of the coordinating center performed regular quality checks to ensure integrity of data collection and completeness of follow-up as previously reported. 21 All the local investigators were trained on available RCTs and guidelines on short-term DAPT and on study procedures and definitions of the outcomes prior to the study start.

Outcomes

The primary effectiveness outcome was a composite of new stroke events (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or death due to vascular causes at 90 days. The primary safety outcome was a moderate-to-severe bleeding at 90 days.

Secondary outcomes were cerebral ischemic event (i.e., ischemic stroke or TIA), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), subarachnoid hemorrhage, other intracranial hemorrhage (i.e., subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, or other), hemorrhagic infarction, myocardial infarction, vascular death, non-vascular death, any hospitalization, disability measured by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), cause of DAPT discontinuation (i.e., adverse events, lack of compliance, other), severe bleeding, moderate bleeding, and mild bleeding. Secondary composite outcomes were any bleeding (i.e., any of severe, moderate, or mild bleeding) and any death (i.e., any of death due to vascular or non-vascular causes).

Each local investigator adjudicated outcome events on review of medical charts. We reported outcomes in the entire study cohort, in patients following or not RCTs inclusion criteria and procedures, and in pre-specified subgroups: age > or ⩽65 years, body mass index (BMI) < or ⩾30, symptoms < or ≥24 h, presence of acute lesions at neuroimaging, NIHSS score ⩽ or >3, NIHSS score ⩽ or >5, ABCD 2 score ⩽ or >4, and loading dose.

Statistical analysis

The enrollment period spanned a minimum of 2 years with the possibility of an extension if sample size was not reached. Using a 95% confidence interval, we estimated sample size of 1067 subjects to detect a conservative 50% proportion of primary effectiveness outcome with a two-sided 2.5% margin of error.

We performed all the analyses according to the intention-to-treat principle in patients who completed the follow-up or had an outcome event within 90 days. We excluded from the statistical analyses patients who had an end of study visit prior than 80 days, who underwent stenting procedures during the follow-up, and who discontinued DAPT due to the diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or any other condition requiring anticoagulation – excluded to avoid bias attributable to therapeutic switch. In case patients had multiple events, only the first outcome was used in the model. Given the low number of the outcome events all the analyses were exploratory.

We reported descriptive statistics about demographics, characteristics of the index event, and outcome events. Categorical data were reported as number and percentage; 95% Poisson Confidence Interval (CI) were provided for the outcomes. Continuous data had non-normal distribution at Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical and continuous data were compared across subgroups through the χ2 and Mann–Whitney U tests respectively.

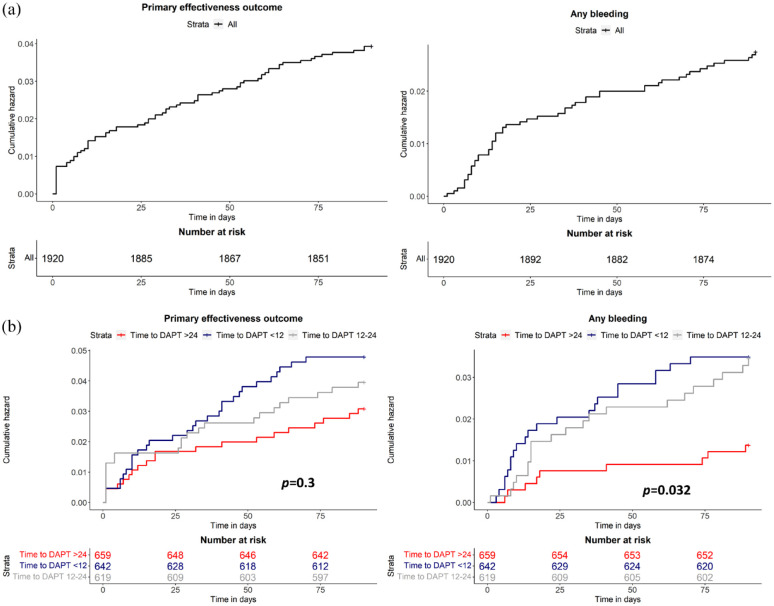

To assess time distribution of outcome events during the follow-up, we performed survival analysis of primary effectiveness outcome and any bleeding. We further compared time to primary effectiveness outcome and any bleeding among patients who started DAPT within 12, 12–24, and after 24 h from symptom onset with log-rank test.

Statistics and graphs were performed through SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), R 3.3.0+, and GraphPad version 10.

Results

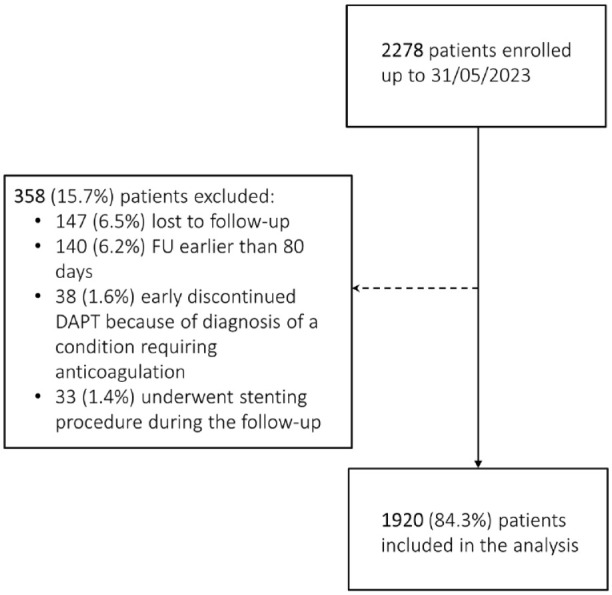

Out of 2278 patients enrolled between February 2021 and February 2023, 6.5% were lost to follow-up, 6.2% had a follow-up earlier than 80 days from the index event, 1.6% discontinued DAPT because of a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation or any other condition requiring anticoagulation, and 1.4% underwent stenting procedures. Therefore, we included in the analysis 1920 (84.3%) patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated standards of reporting trials diagram of enrollment in the study.

DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; FU: follow-up.

Demographics and characteristics of the index event

Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the study cohort. Most patients received DAPT after an ischemic stroke (69.9%); among them 35.4% had NIHSS score >3 and 11.8% NIHSS score >5 (Figure S1). A total of 30.1% of patients had a TIA; among them 20.1% had an ABCD 2 score <4 (Figure S2) and 65.7% an ABCD 2 score <6 without any symptomatic intracranial/extracranial stenosis. Eighteen point four percent of patients underwent a revascularization procedure: 16.2% IVT, 1.9% EVT, and 2.4% endarterectomy. Only 8.9% of patients would have met RCTs entry criteria regarding the characteristics of the event and followed their procedures such as timing of DAPT start and loading dose (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population.

| Characteristics | Overall study cohort* |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 72 (62–79) |

| Female gender, N (%) | 665 (34.6) |

| Caucasian, N (%) | 1877 (97.8) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26 (24–28) |

| Current smoker, N (%) | 492 (25.6) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 1527 (79.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 521 (27.1) |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 1160 (60.4) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 398 (20.7) |

| Previous ischemic event, N (%) | 366 (19.1) |

| TIA | 208 (10.8) |

| Ischemic stroke | 158 (8.3) |

| Previous intracerebral hemorrhage, N (%) | 15 (0.8) |

| Myocardial infarction, N (%) | 183 (9.5) |

| Angina, N (%) | 62 (3.2) |

| Congestive heart failure, N (%) | 58 (3.0) |

| Peripheral chronic obliterative arteriopathy, N (%) | 110 (5.7) |

| Use of antiplatelet prior to the index event, N (%) | 783 (40.7) |

| Symptom duration, N (%) | |

| ≥24 h | 1342 (69.9) |

| <24 h | 578 (30.1) |

| Lesions at neuroimaging, N (%) | |

| Yes | 1302 (67.8) |

| No | 618 (32.2) |

| ABCD 2 score in patients with qualifying TIA, median (IQR) | 5 (4–5) |

| ABCD 2 < 4, N (%) | 120 (20.1) |

| ABCD 2 < 6 and no LAA, N (%) | 380 (65.7) |

| NIHSS score in patients with qualifying ischemic stroke, median (IQR) and [range] | 3 (2–4), [0–28] |

| NIHSS > 3, N (%) | 475 (35.4) |

| NIHSS > 5, N (%) | 159 (11.8) |

| mRS baseline, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) |

| mRS > 2, N (%) | 76 (4.0) |

| Time to DAPT start, N (%) | |

| <12 h | 642 (33.4) |

| 12–24 h | 619 (32.2) |

| 25–48 h | 390 (20.4) |

| >48 h | 269 (14.0) |

| Type of DAPT, N (%) | |

| Aspirin/clopidogrel | 1912 (99.6) |

| Aspirin/ticagrelor | 8 (0.4) |

| Loading dose, N (%) | 1035 (53.9) |

| Aspirin | 552 (28.7) |

| Clopidogrel | 703 (36.6) |

| Ticagrelor | 5 (0.3) |

| Revascularization procedures, N (%) | 353 (18.4) |

| Cause of the event, N (%) | |

| LAA | 452 (23.5) |

| SAO | 534 (27.8) |

| Other | 104 (5.4) |

| Undetermined | 830 (43.3) |

| DAPT duration, median (IQR) | 21 (21–45) |

| DAPT duration <21 days, N (%) | 124 (6.5) |

| DAPT duration 21–30 days, N (%) | 1256 (65.4) |

| DAPT duration 30–90 days, N (%) | 540 (28.1) |

| DAPT discontinuation before expected completion, N (%) | 88 (4.5) |

| Adverse events | 22 (1.1) |

| Lack of compliance | 15 (0.8) |

| Other | 51 (2.6) |

BMI: body mass index; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; h: hours; IQR: interquartile range; LD: loading dose; LAA: large-artery atherosclerosis; mRS: modified Rankin scale; N: number; NIHSS: national institutes of health stroke scale; SAO: small-artery occlusion; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

All patients were evaluable for the analysis.

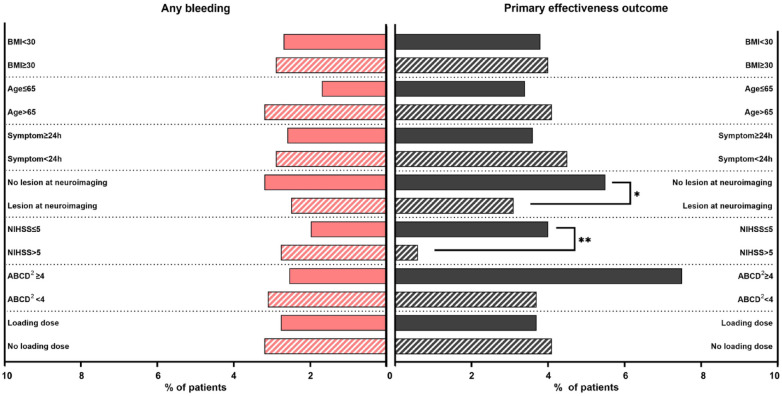

Figure 2.

Rates of any bleeding and primary effectiveness outcomes across pre-specified subgroups.

BMI: body mass index; h: hours; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

*p value =0.010. **p value =0.033.

The cause of the event according to the Trial of Org 10172 in acute stroke treatment (TOAST) classification 31 was in most of the cases undetermined (43.3%) followed by small-artery occlusion (SAO) (27.8%), large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA) (23.5%), and other determined causes (5.4%) (Table 1). Among the undetermined events, 32.5% were classified as embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) and in 11% of cases physicians detected a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

DAPT regimen

The most prescribed DAPT was clopidogrel/aspirin (99.6%), with 33.4% of patients starting the therapy within 12 h from symptom onset and 14.0% after 48 h (Table 1). A total of 53.9% of patients received a loading dose of any antiplatelets, with clopidogrel being the most common (36.6%) (Supplemental Figure S3).

DAPT median duration was 21 days (IQR 21–45 days); bleedings were the most common adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation (Table 1). Aspirin was the most frequent antiplatelet prescribed after DAPT cessation (Supplemental Result 2.1).

Effectiveness and safety outcomes

Median follow-up duration was 96 (IQR 92–106) days. End-of-study visits were conducted face-to-face for 44% of patients and remotely for the remaining 56%.

During the follow-up, a primary effectiveness outcome occurred in 3.9% (3.07–4.83 95% CI) of patients and a primary safety outcome occurred in 0.6% (0.35–1.11 95% CI) of patients; 3.3% (2.61–4.26 95% CI) of patients had an ischemic recurrence (2.0% had an ischemic stroke and 1.3% a TIA) and 0.2% (0.05–0.46 95% CI) had an ICH (Supplemental Result 2.2). In addition, 0.1% (0.03–0.38 95% CI) of patients had a subarachnoid hemorrhage and 0.1% (0.03–0.38 95% CI) other intracranial bleedings. Myocardial infarction occurred in 0.2% (0.05–0.46 95% CI) of patients and 3.3% (2.56–4.19 95% CI) required a new hospitalization. A total of 78.8% (75.03–82.98 95% CI) of patients had mRS of 0–1 and median mRS was 0 (IQR 0–1) at 90 days (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary effectiveness and safety outcome in READAPT, CHANCE, POINT, and THALES.

| Outcome | READAPT* | CHANCE 6 | POINT 7 | THALES 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 1920 | 2584 | 2432 | 5493 |

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Primary effectiveness outcome†, N (%) | 74 (3.9) | 212 (8.2) | 121 (5.0) | 303 (5.5) |

| Primary safety outcome§ N (%) | 12 (0.6) | 7 (0.3) | 23 (0.9) | 28 (0.5) |

| Key secondary outcomes | ||||

| Ischemic event, N (%) | 64 (3.3) | 243 (9.4) | 112 (4.6) | 276 (5.0) |

| Ischemic stroke | 38 (2.0) | 204 (7.9) | 112 (4.6) | 276 (5.0) |

| TIA | 26 (1.3) | 39 (1.5) | NA | NA |

| Hemorrhagic transformation, N (%) | 19 (1.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Symptomatic | 2 (0.1) | |||

| Asymptomatic | 17 (0.9) | |||

| Intracranial hemorrhage, N (%) | 3 (0.2) | 8 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 22 (0.4) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage, N (%) | 2 (0.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| Other intracranial hemorrhage, N (%) | 2 (0.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| Myocardial infarction, N (%) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 10 (0.4) | NA |

| Death, N (%) | 8 (0.5) | 10 (0.4) | 18 (0.7) | 36 (0.7) |

| Vascular | 3 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | |

| Non-vascular | 5 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 12 (0.5) | |

| Severe bleeding, N (%) | 9 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | 17 (0.7) | 28 (0.5) |

| Moderate bleeding, N (%) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | NA | 36 (0.7%) a |

| Mild bleeding, N (%) | 40 (2.1) | 30 (1.2) | 40 (1.6) | 36 (0.7%) a |

| Any bleeding, N (%) | 52 (2.7) | 60 (2.3) | NA | NA |

| Hospitalization, N (%) | 63 (3.3) | NA | NA | NA |

| mRS, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | NA | NA | NA |

mRS: modified Rankin scale; NA: not available; N: Number; TIA: transient ischemic attack.

Moderate or mild bleeding.

All patients were evaluable for the analysis.

Primary efficacy outcome in CHANCE was new stroke event (ischemic or hemorrhagic), in POINT was the composite of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or death from ischemic vascular causes, and in THALES was the composite of stroke (ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke) or death.

Primary safety outcome in CHANCE was moderate-severe bleeding event, in POINT was major hemorrhage, and in THALES was severe bleeding event.

Overall, 2.7% (2.06–3.55 95% CI) of patients had any bleeding event. Severe bleedings occurred in 0.5% (0.24–0.89 95% CI) of patients, moderate in 0.2% (0.05–0.46 95% CI), and mild bleedings in 2.1% (1.53–2.84 95% CI). Death occurred in 0.5% (0.25–0.89 95% CI) of patients, 0.2% (0.05–0.46 95% CI) due to vascular causes and 0.3% (0.11–0.60 95% CI) due to non-vascular causes (Table 2). Hemorrhagic infarction occurred in 1% (0.63–1.54 95% CI) of patients and was symptomatic only in 0.1% (0.03–0.38 95% CI) of cases.

Most of the outcomes occurred while patients were still on DAPT treatment: 60.8% of primary effectiveness outcomes, 58.3% of primary safety outcomes, and 61.5% of any bleedings. Notably, 2.0% of patients had multiple outcome events; additional details are available in Supplemental Table S2.

Effectiveness and safety in subgroups of interest

Patients who did not follow RCTs entry criteria and procedures had comparable effectiveness and safety outcomes to their counterpart (Supplemental Table S3). Regarding the pre-specified subgroups, primary effectiveness outcome was more frequent among those without acute lesion at neuroimaging (5.5%, 3.93–7.69 95% CI) compared with those with lesions at neuroimaging (3.1%, 2.25–4.18 95% CI, p = 0.010) and among patients with NIHSS score ⩽5 (4.0%, 2.99–5.28 95% CI) compared with NIHSS score >5 (0.6%, 0.11–3.56 95% CI, p = 0.033) (Figure 2). A primary safety outcome occurred more often in patients with NIHSS score >3 (1.3%, 0.58–2.76 95% CI) and compared with NIHSS ⩽ 3 (0.2%, 0.06–0.84 95% CI, p = 0.019). We found no statistically significant difference in the other subgroups defined according to BMI, symptom duration, and loading dose. However, any bleeding outcome tended to be more common among patients >65 years (3.2%, 2.37–4.36 95% CI) compared with those ⩽65 years (1.7%, 0.95–3.06 95% CI, p = 0.055) (Supplemental Table S3) (Figure 2).

Cumulative probabilities of primary effectiveness outcome and any bleeding according to time to DAPT start

Out of the 74 primary effectiveness outcomes, 18.9% occurred the day after the index event and 28.3% within 7 days (Figure 3a). There were no differences in primary effectiveness outcomes among patients who started DAPT within 12 h, between 12 and 24 h, and after 24 h from symptom onset (p = 0.3) (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Cumulative hazards of the primary effectiveness outcome and any bleeding in the overall study cohort (a) and in subgroups of patients defined according to time to dual antiplatelet therapy start (b).

Out of the 52 any bleeding events, 15.4% occurred within the first week from index event, 23.1% in the second week, and 11.5% in the third week (Figure 3a). Proportions of any bleeding gradually decreased in the following weeks. Patients treated with DAPT within 12 h and between 12-24 h were at higher risk of any bleeding than those who started DAPT after 24 h from symptom onset (p = 0.032) (Figure 3b).

Discussion

The READAPT study provided data on real-world effectiveness and safety of short-term DAPT in secondary prevention of non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA. As previously reported, a high proportion of patients in real-world is treated with a short course of DAPT even if not strictly meeting RCTs definitions of “minor” ischemic stroke or “high-risk” TIA. 21 Additionally, many patients did not follow trials procedures. Nevertheless, in this population, short-term DAPT turned out to be associated with even better effectiveness and safety than anticipated on RCTs results.6–8

During the 90-day follow-up, we observed 3.9% primary effectiveness outcomes – a recurrent ischemic event, vascular death, or an intracranial bleeding – mainly driven by ischemic recurrences which occurred in 3.3% of patients.6–8 Most of the recurrences occurred early after the index event, thus, reinforcing the need of a prompt DAPT start in eligible patients. We found a lower rate of 90-day ischemic recurrences in READAPT than in other real-world studies (3.8-4.7%), which included both patients treated with DAPT and with other preventative therapies.3,5 The same rate was also lower than those reported in RCTs6–8 (Table 2). Investigators might have missed recurrences presenting with mild or worsening of preexisting symptoms or occurred before DAPT start. The effectiveness of DAPT might have been greater than in RCTs due to the underrepresentation of Black and Asian patients, who are at high risk of ischemic recurrences.32,33 Additionally, the high vascular risk profile prevalent in our population might have contributed to the enhanced benefits of DAPT.11,15

DAPT had a similar safety profile in READAPT compared to RCTs6–8 (Table 2), even if mild bleedings were about one percentage point higher.6–8 Furthermore, bleedings were among the most frequent adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation. Time-to-event analysis showed that DAPT start within 12 h from symptom onset was associated with a higher risk of any bleeding possibly due to a higher rate of hemorrhagic transformation or intracranial bleedings in these patients. A proper evaluation of patients’ hemorrhagic risks including an assessment of the volume of ischemic lesions might minimize hemorrhagic complications of DAPT. The exact window for DAPT start after an ischemic event is yet to be defined, the INSPIRES and a sub-analysis of POINT showed that DAPT was still beneficial if administered within 72 h from symptom onset,9,34 thus a delayed treatment start might be considered in specific cases. Mortality was not a concern in our cohort, and the rate of vascular death was comparable to RCTs.6–8

The READAPT study included patients who, in clinical practice, are perceived at high risk of ischemic recurrences and low risk of bleedings even if outside the RCTs boundaries for minor stroke or high-risk TIA. We found no significant difference in primary effectiveness outcome among those with ABCD 2 score ⩾ or <4 supporting the need for a comprehensive vascular risk evaluation not only based on ABCD 2 score. 35 Conversely, patients with NIHSS score >5 had a lower rate of primary effectiveness outcome compared with those with NIHSS score ⩽5 in line with a previous real-world study which identified NIHSS score 3–10 as a predictor of DAPT effectiveness. 12 This result should be carefully interpreted due to the low number of patients with NIHSS score >5 and the increased bleeding risk in patients with NIHSS score >3. Regarding safety, patients older than 65 years had a higher rate of any bleeding events. Similarly, a meta-analysis showed an increased risk of severe bleeding among patients ⩾65 years treated with DAPT compared with SAPT. 36 However, this meta-analysis included data of RCTs, which exclusively evaluated long-term DAPT efficacy with various combinations of antiplatelets and dosages. 36 The safety of short-term DAPT in the elderly still needs to be investigated as it is unclear whether the bleeding risk linearly increases with the age, as shown for long-term SAPT with aspirin, 37 and whether other cofactors such as comorbidities might play a role.

The READAPT cohort distinguished itself from RCTs also due to the lack of loading dose and the use of revascularization procedures. We observed similar DAPT effectiveness and safety in patients who received or not a loading dose. However, the heterogeneity and lack of details on the dosage limits the interpretation of these results. Only 53.9% of patients received a loading dose and they were mainly naïve to prior antiplatelets. The absence of a loading dose in eligible patients might be due to prior antiplatelet therapy with a different agent or physicians’ unfamiliarity with this procedure as previously discussed. 21 Notably, revascularization procedures did not result in a concerning increase in the bleedings compared to RCTs. With 16.2% of patients treated with IVT in our cohort, we support the growing trend in IVT usage in minor stroke. 38 However, the lack of evidence on benefits/risks of DAPT after IVT might have limited the combination of these therapies and some patients might have presented to physicians outside the window for IVT. Therefore, the efficacy and safety of DAPT after IVT needs to be further addressed by larger randomized studies.

In terms of DAPT benefit/risk timeseries, most of the primary effectiveness outcomes occurred within the first week, while the rates of any bleeding peaked during the second week and then remained constant up to day 90. A time-course analysis of CHANCE showed that DAPT reduced the 1-week risk of new ischemic stroke by approximately 35% and numerically increased the risk of any bleeding during the first 4 weeks. 39 Both in READAPT and CHANCE subgroup analyses there was an increase of hemorrhagic risk during the second week, but we did not observe a similar continuous increasing rate of any bleeding over time possibly due to the low number of any bleeding events and/or lack of treatment compliance.

To our knowledge, the READAPT is the largest real-world prospective study that provided insights into DAPT effectiveness and safety in real-word; the study also provided outcomes in patients outside RCTs boundaries. The other available real-world studies evaluated the effectiveness and safety of DAPT compared with SAPT10–15 or focused on DAPT safety after IVT.16,17 Most of these studies had a retrospective design, all of them have exclusively included Asian patients with an ischemic stroke, and none have specifically considered those with uncertain DAPT benefits/risks according to RCTs evidence. Indeed, the sole study which included patients with moderate ischemic stroke (i.e., NIHSS ⩽ 10), aimed at comparing SAPT with DAPT both combined with highly intensive statin regimen and had a limited sample size (n = 127 DAPT vs 204 SAPT). 12 Additionally, we evaluated DAPT effectiveness and safety after a TIA, while the sole study that included patients with tissue-based TIA reserved DAPT for those with acute lesions at neuroimaging. 14

The READAPT adopted rigorous procedures to ensure accuracy, completeness, and quality of data. Among the limitations of the study, the geographical setting restricted to Italy, the predominantly Caucasian population, and the low proportion of females hinder the generalizability of our results. The study was underpowered to identify predictors of outcome events and all the analyses were exploratory; therefore, our findings need to be confirmed by larger studies. Additionally, READAPT observational design might have led to an underreporting of the outcomes. The appropriateness of outcome adjudication was upon unblinded investigators part of the same local staff team as we did not have direct access to patients’ records. Most of the end of study visits have been remotely performed possibly affecting the accuracy of outcome collection. Lastly, we excluded patients with minor stroke due to cardioembolic sources with a possible selection bias. We further excluded those who discontinued DAPT because of a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation as we aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of DAPT in patients with non-cardioembolic causes. However, we cannot exclude occult cardioembolism underlying some of the index or recurrent events as not all patients received a prolonged or continuous cardiac monitoring.

Conclusions

Although the use of short-term DAPT for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke or TIA is broader in real-world than in RCTs, the READAPT study showed that, in real-world setting, there are no safety concerns emerging from DAPT use except for the elderly who may be at higher risk of bleeding. Based on our results, the therapy might be considered in patients who slightly exceed the conventional boundaries for minor stroke or with low risk TIA based on NIHSS and ABCD 2 score respectively. We also recommend to promptly start DAPT after symptom onset, since most of the ischemic recurrences occurred early after the index event.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241255250 for Beyond RCTs: Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy in secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack by Eleonora De Matteis, Raffaele Ornello, Federico De Santis, Matteo Foschi, Michele Romoli, Tiziana Tassinari, Valentina Saia, Silvia Cenciarelli, Chiara Bedetti, Chiara Padiglioni, Bruno Censori, Valentina Puglisi, Luisa Vinciguerra, Maria Guarino, Valentina Barone, Marialuisa Zedde, Ilaria Grisendi, Marina Diomedi, Maria Rosaria Bagnato, Marco Petruzzellis, Domenico Maria Mezzapesa, Pietro Di Viesti, Vincenzo Inchingolo, Manuel Cappellari, Mara Zenorini, Paolo Candelaresi, Vincenzo Andreone, Giuseppe Rinaldi, Alessandra Bavaro, Anna Cavallini, Stefan Moraru, Pietro Querzani, Valeria Terruso, Marina Mannino, Alessandro Pezzini, Giovanni Frisullo, Francesco Muscia, Maurizio Paciaroni, Maria Giulia Mosconi, Andrea Zini, Ruggiero Leone, Carmela Palmieri, Letizia Maria Cupini, Michela Marcon, Rossana Tassi, Enzo Sanzaro, Cristina Paci, Giovanna Viticchi, Daniele Orsucci, Anne Falcou, Susanna Diamanti, Roberto Tarletti, Patrizia Nencini, Eugenia Rota, Federica Nicoletta Sepe, Delfina Ferrandi, Luigi Caputi, Gino Volpi, Salvatore La Spada, Mario Beccia, Claudia Rinaldi, Vincenzo Mastrangelo, Francesco Di Blasio, Paolo Invernizzi, Giuseppe Pelliccioni, Maria Vittoria De Angelis, Laura Bonanni, Giampietro Ruzza, Emanuele Alessandro Caggia, Monia Russo, Agnese Tonon, Maria Cristina Acciarri, Sabrina Anticoli, Cinzia Roberti, Giovanni Manobianca, Gaspare Scaglione, Francesca Pistoia, Alberto Fortini, Antonella De Boni, Alessandra Sanna, Alberto Chiti, Leonardo Barbarini, Marcella Caggiula, Maela Masato, Massimo Del Sette, Francesco Passarelli, Maria Roberta Bongioanni, Danilo Toni, Stefano Ricci and Simona Sacco in European Stroke Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-eso-10.1177_23969873241255250 for Beyond RCTs: Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy in secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack by Eleonora De Matteis, Raffaele Ornello, Federico De Santis, Matteo Foschi, Michele Romoli, Tiziana Tassinari, Valentina Saia, Silvia Cenciarelli, Chiara Bedetti, Chiara Padiglioni, Bruno Censori, Valentina Puglisi, Luisa Vinciguerra, Maria Guarino, Valentina Barone, Marialuisa Zedde, Ilaria Grisendi, Marina Diomedi, Maria Rosaria Bagnato, Marco Petruzzellis, Domenico Maria Mezzapesa, Pietro Di Viesti, Vincenzo Inchingolo, Manuel Cappellari, Mara Zenorini, Paolo Candelaresi, Vincenzo Andreone, Giuseppe Rinaldi, Alessandra Bavaro, Anna Cavallini, Stefan Moraru, Pietro Querzani, Valeria Terruso, Marina Mannino, Alessandro Pezzini, Giovanni Frisullo, Francesco Muscia, Maurizio Paciaroni, Maria Giulia Mosconi, Andrea Zini, Ruggiero Leone, Carmela Palmieri, Letizia Maria Cupini, Michela Marcon, Rossana Tassi, Enzo Sanzaro, Cristina Paci, Giovanna Viticchi, Daniele Orsucci, Anne Falcou, Susanna Diamanti, Roberto Tarletti, Patrizia Nencini, Eugenia Rota, Federica Nicoletta Sepe, Delfina Ferrandi, Luigi Caputi, Gino Volpi, Salvatore La Spada, Mario Beccia, Claudia Rinaldi, Vincenzo Mastrangelo, Francesco Di Blasio, Paolo Invernizzi, Giuseppe Pelliccioni, Maria Vittoria De Angelis, Laura Bonanni, Giampietro Ruzza, Emanuele Alessandro Caggia, Monia Russo, Agnese Tonon, Maria Cristina Acciarri, Sabrina Anticoli, Cinzia Roberti, Giovanni Manobianca, Gaspare Scaglione, Francesca Pistoia, Alberto Fortini, Antonella De Boni, Alessandra Sanna, Alberto Chiti, Leonardo Barbarini, Marcella Caggiula, Maela Masato, Massimo Del Sette, Francesco Passarelli, Maria Roberta Bongioanni, Danilo Toni, Stefano Ricci and Simona Sacco in European Stroke Journal

Acknowledgments

The Authors wish to thank all the study patients for their kind cooperation.

Footnotes

Correction (June 2024): Article updated to replace Figure 3(b). In the original publication the x-axis was cut off.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AZ reports compensation from Angels Initiative, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, CSL Behring, Bayer, and Astra Zeneca; and he is member of ESO guidelines, ISA-AII guidelines, and IRETAS steering committee. RO reports compensations from Novartis and Allergan, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Eli Lilly and Company, SS reports compensations from Novartis, NovoNordisk, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Pfizer Canada, Inc, Eli Lilly and Company, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, H. Lundbeck A/S, and Abbott Canada; employment by Università degli Studi dell’Aquila. MPa reports compensation from Daiichi Sankyo Company, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bayer, and Pfizer Canada, Inc. DT reports compensation from Alexion, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, and Pfizer. The other authors report no conflicts.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: READAPT is a non-profit study.

Informed consent: All patients gave written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Internal Review Board of the University of L’Aquila (Italy) with the number 03/2021.

Guarantor: SS takes full responsibility for the article, including for the accuracy and appropriateness of the reference list.

Contributorship: SS conceived the study and its design; SR and DT provided critical revision to the study protocol; EDM coordinated data collection, performed the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; RO, MF and MR provided support in statistical analysis; SS, EDM, and RO drafted the manuscript; all the Authors acquired data, provided critical revision in the analysis and interpretation of data, and approved the final manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Raffaele Ornello  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9501-4031

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9501-4031

Federico De Santis  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8059-6427

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8059-6427

Matteo Foschi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0321-7155

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0321-7155

Michele Romoli  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8009-8543

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8009-8543

Anna Cavallini  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5227-1502

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5227-1502

Marina Mannino  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7683-7235

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7683-7235

Alessandro Pezzini  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8629-3315

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8629-3315

Maurizio Paciaroni  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5483-8795

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5483-8795

Maria Giulia Mosconi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0456-9160

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0456-9160

Rossana Tassi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5906-8718

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5906-8718

Enzo Sanzaro  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2417-872X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2417-872X

Giovanna Viticchi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1799-1563

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1799-1563

Simona Sacco  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0651-1939

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0651-1939

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Xiong Y, Gu H, Zhao XQ, et al. Clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of varying definitions of minor stroke: from a large-scale nation-wide longitudinal registry. Stroke 2021; 52: 1253–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saber H, Saver JL. Distributional validity and prognostic power of the national institutes of health stroke scale in US administrative claims data. JAMA Neurol 2020; 77: 606–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shahjouei S, Sadighi A, Chaudhary D, et al. A 5-decade analysis of incidence trends of ischemic stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2021; 78: 77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1533–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hobeanu C, Lavallée PC, Charles H, et al. Risk of subsequent disabling or fatal stroke in patients with transient ischaemic attack or minor ischaemic stroke: an international, prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2022; 21: 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, et al. Ticagrelor and aspirin or aspirin alone in acute ischemic stroke or TIA. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gao Y, Chen W, Pan Y, et al. Dual antiplatelet treatment up to 72 hours after ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2023; 389: 2413–2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang M, Yang Y, Wang Y, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy in acute ischaemic stroke with or without cerebral microbleeds. Eur J Neurosci 2023; 57: 1197–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fan H, Wang Y, Liu T, et al. Dual versus mono antiplatelet therapy in mild-to-moderate stroke during hospitalization. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2022; 9: 506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deng T, Zhang T, Lu H, et al. Evaluation and subgroup analysis of the efficacy and safety of intensive rosuvastatin therapy combined with dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2023; 79: 389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang K, Liu T, Fan H, et al. Dual versus mono antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute mild-to-moderate stroke: a multicentre perspective cohort study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. Epub ahead of print 13 June 2023. DOI: 10.1007/s10557-023-07468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pei LL, Chen P, Fang H, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy reduced stroke risk in transient ischemic attack with positive diffusion weighted imaging. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 19132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee HL, Kim JT, Lee JS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel versus aspirin monotherapy in mild-to-moderate acute ischemic stroke according to the risk of recurrent stroke: an analysis of 15 000 patients from a nationwide, multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020; 13: e006474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu Z, Chen N, Sun H, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with minor stroke receiving intravenous thrombolysis. Front Neurol 2022; 13: 819896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhao G, Lin F, Wang Z, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy after intravenous thrombolysis for acute minor ischemic stroke. Eur Neurol 2019; 82: 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Del Brutto VJ, Yin R, Gardener H, et al. Determinants and temporal trends of dual antiplatelet therapy after mild noncardioembolic stroke. Stroke 2023; 54: 2552–2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xian Y, Xu H, Matsouaka R, et al. Analysis of prescriptions for dual antiplatelet therapy after acute ischemic stroke. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5: e2224157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lendaris AR, Lessen S, Cheng NT, et al. Under treatment of high-risk TIA patients with clopidogrel-aspirin in the emergency setting. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2021; 30: 106145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Matteis E, De Santis F, Ornello R, et al. Divergence between clinical trial evidence and actual practice in use of dual antiplatelet therapy after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. Stroke 2023; 54: 1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014; 12: 1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ISO-Spread. Raccomandazione Rapida 11.1 e, https://isa-aii.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/c.20_2019.pdf (2019).

- 24. Gladstone DJ, Lindsay MP, Douketis J, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: secondary prevention of stroke update 2020. Can J Neurol Sci 2022; 49: 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dawson J, Merwick Á, Webb A, et al. European Stroke Organisation expedited recommendation for the use of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy early after minor stroke and high-risk TIA. Eur Stroke J 2021; 6: CLXXXVII–CXCI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the american heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021; 52: e364–e467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aho K, Harmsen P, Hatano S, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ 1980; 58: 113–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. GUSTO investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adams HP, Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke 1993; 24: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kamel H, Zhang C, Kleindorfer DO, et al. Association of black race with early recurrence after minor ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: secondary analysis of the POINT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2020; 77: 601–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pan Y, Chen W, Xu Y, et al. Genetic polymorphisms and clopidogrel efficacy for acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2017; 135: 21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Johnston SC, Elm JJ, Easton JD, et al. Time course for benefit and risk of clopidogrel and aspirin after acute transient ischemic attack and minor ischemic stroke. Circulation 2019; 140: 658–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fonseca AC, Merwick Á, Dennis M, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of transient ischaemic attack. Eur Stroke J 2021; 6: CLXIII–CLXXXVI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ding L, Peng B. Efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy in the elderly for stroke prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 2018; 25: 1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li L, Geraghty OC, Mehta Z, et al. Age-specific risks, severity, time course, and outcome of bleeding on long-term antiplatelet treatment after vascular events: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2017; 390: 490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Asaithambi G, Tong X, Coleman King SM, et al. Contemporary trends in the treatment of mild ischemic stroke with intravenous thrombolysis: Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Program. Cerebrovasc Dis 2022; 51: 60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pan Y, Jing J, Chen W, et al. Risks and benefits of clopidogrel-aspirin in minor stroke or TIA: Time course analysis of CHANCE. Neurology 2017; 88: 1906–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241255250 for Beyond RCTs: Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy in secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack by Eleonora De Matteis, Raffaele Ornello, Federico De Santis, Matteo Foschi, Michele Romoli, Tiziana Tassinari, Valentina Saia, Silvia Cenciarelli, Chiara Bedetti, Chiara Padiglioni, Bruno Censori, Valentina Puglisi, Luisa Vinciguerra, Maria Guarino, Valentina Barone, Marialuisa Zedde, Ilaria Grisendi, Marina Diomedi, Maria Rosaria Bagnato, Marco Petruzzellis, Domenico Maria Mezzapesa, Pietro Di Viesti, Vincenzo Inchingolo, Manuel Cappellari, Mara Zenorini, Paolo Candelaresi, Vincenzo Andreone, Giuseppe Rinaldi, Alessandra Bavaro, Anna Cavallini, Stefan Moraru, Pietro Querzani, Valeria Terruso, Marina Mannino, Alessandro Pezzini, Giovanni Frisullo, Francesco Muscia, Maurizio Paciaroni, Maria Giulia Mosconi, Andrea Zini, Ruggiero Leone, Carmela Palmieri, Letizia Maria Cupini, Michela Marcon, Rossana Tassi, Enzo Sanzaro, Cristina Paci, Giovanna Viticchi, Daniele Orsucci, Anne Falcou, Susanna Diamanti, Roberto Tarletti, Patrizia Nencini, Eugenia Rota, Federica Nicoletta Sepe, Delfina Ferrandi, Luigi Caputi, Gino Volpi, Salvatore La Spada, Mario Beccia, Claudia Rinaldi, Vincenzo Mastrangelo, Francesco Di Blasio, Paolo Invernizzi, Giuseppe Pelliccioni, Maria Vittoria De Angelis, Laura Bonanni, Giampietro Ruzza, Emanuele Alessandro Caggia, Monia Russo, Agnese Tonon, Maria Cristina Acciarri, Sabrina Anticoli, Cinzia Roberti, Giovanni Manobianca, Gaspare Scaglione, Francesca Pistoia, Alberto Fortini, Antonella De Boni, Alessandra Sanna, Alberto Chiti, Leonardo Barbarini, Marcella Caggiula, Maela Masato, Massimo Del Sette, Francesco Passarelli, Maria Roberta Bongioanni, Danilo Toni, Stefano Ricci and Simona Sacco in European Stroke Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-eso-10.1177_23969873241255250 for Beyond RCTs: Short-term dual antiplatelet therapy in secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack by Eleonora De Matteis, Raffaele Ornello, Federico De Santis, Matteo Foschi, Michele Romoli, Tiziana Tassinari, Valentina Saia, Silvia Cenciarelli, Chiara Bedetti, Chiara Padiglioni, Bruno Censori, Valentina Puglisi, Luisa Vinciguerra, Maria Guarino, Valentina Barone, Marialuisa Zedde, Ilaria Grisendi, Marina Diomedi, Maria Rosaria Bagnato, Marco Petruzzellis, Domenico Maria Mezzapesa, Pietro Di Viesti, Vincenzo Inchingolo, Manuel Cappellari, Mara Zenorini, Paolo Candelaresi, Vincenzo Andreone, Giuseppe Rinaldi, Alessandra Bavaro, Anna Cavallini, Stefan Moraru, Pietro Querzani, Valeria Terruso, Marina Mannino, Alessandro Pezzini, Giovanni Frisullo, Francesco Muscia, Maurizio Paciaroni, Maria Giulia Mosconi, Andrea Zini, Ruggiero Leone, Carmela Palmieri, Letizia Maria Cupini, Michela Marcon, Rossana Tassi, Enzo Sanzaro, Cristina Paci, Giovanna Viticchi, Daniele Orsucci, Anne Falcou, Susanna Diamanti, Roberto Tarletti, Patrizia Nencini, Eugenia Rota, Federica Nicoletta Sepe, Delfina Ferrandi, Luigi Caputi, Gino Volpi, Salvatore La Spada, Mario Beccia, Claudia Rinaldi, Vincenzo Mastrangelo, Francesco Di Blasio, Paolo Invernizzi, Giuseppe Pelliccioni, Maria Vittoria De Angelis, Laura Bonanni, Giampietro Ruzza, Emanuele Alessandro Caggia, Monia Russo, Agnese Tonon, Maria Cristina Acciarri, Sabrina Anticoli, Cinzia Roberti, Giovanni Manobianca, Gaspare Scaglione, Francesca Pistoia, Alberto Fortini, Antonella De Boni, Alessandra Sanna, Alberto Chiti, Leonardo Barbarini, Marcella Caggiula, Maela Masato, Massimo Del Sette, Francesco Passarelli, Maria Roberta Bongioanni, Danilo Toni, Stefano Ricci and Simona Sacco in European Stroke Journal