Abstract

We critically reviewed the motivations, processes, and implementation methods underlying a faculty-driven diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) curriculum self-reflection project in the Rutgers School of Public Health. This case study offers guidance on a curriculum self-reflection tool that was developed through the school’s Curriculum Committee to promote DEI throughout the school’s curricula. We review the key steps in this process and the unique aspects of developing and implementing such evaluations within higher education. The study draws on faculty experience, was informed by students and staff within the Curriculum Committee, and builds on existing knowledge and tools. A flexible 6-step framework—including guiding principles and strategic approaches to planning, developing, and implementing a DEI curriculum self-assessment—is provided to assist instructors, curriculum committees, DEI groups, and academic leaders at schools of public health interested in refining their courses and curricula. Academic units experience contextual challenges, and while each is at a different stage in curriculum reform, our findings provide lessons about integrating the assessment of DEI in school curriculum in a systematic and iterative way. Our approach can be applied to diverse academic settings, including those experiencing similar implementation challenges.

Keywords: diversity, equity, inclusion, curriculum, faculty self-reflection

The field of public health has been fundamental to documenting health inequities and has started to confront its roots in systems of oppression (eg, racism, sexism, classism, xenophobia, heterosexism); however, courses taught in schools and programs of public health in the United States too often inadequately address, or fail to address, the effects of these oppressive systems on health inequities through course content, instruction, and student engagement.1-3 For example, courses often fail to cite and assign readings reflecting the experiences and contributions of Black and Hispanic/Latino/a people, women, and communities from the Global South and do not include topics directly addressing racism and other forms of oppression reflected in population health and the production of public health research. 4

These concerns were raised by junior faculty members on the Rutgers School of Public Health (R-SPH) Curriculum Committee at meetings during the 2019-2020 school year. Concerns were based on faculty members’ observations of coverage of the R-SPH curricula, as well as feedback from student surveys that consistently showed that students wanted more coverage of the experiences of communities typically silenced in public health research (eg, Black, Hispanic/Latino/a, and LGBTQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer]). Noting that public health instruction with a critical lens to equity and justice is effective, supports student engagement, and promotes the health of people served in public health practice,5-11 the committee began to brainstorm a proactive approach to ensuring diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in our curricula. Guided by student- and faculty-led movements within graduate programs in the United States12-14 and in the wake of a historic uprising against racial injustice and police brutality 15 in 2020, we began a process to review the curricula at R-SPH for coverage of topics and scholarly contributions critically considering DEI, justice, and antiracism. We detail this process, including the compilation of a DEI self-reflection tool, implementation and outcomes of the review process, reflections on the process, and future directions.

Purpose

Use of critical frameworks such as intersectionality and queer, critical race, and feminist theories help to identify and challenge policies, institutions, and practices supporting systems of power that simultaneously create inequalities and conceal how those inequalities are perpetuated by dominant culture.16-19 Culturally relevant pedagogy20,21 and culturally responsive teaching 22 are based in critical frameworks and refer to the empowerment of students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically through the promotion of student learning, cultural humility, and critical consciousness (ie, analysis, synthesis, and critique of sociocultural environments). 23 These practices support inclusive learning environments that confront interlocking systems of oppression and seek to create collaborative settings where all students feel safe and have a sense of belonging. Evidence supports that when instruction, course content, and classroom practices are culturally relevant and embrace the lived experiences and perspectives of diverse communities, including students’ own, they may be more engaged in their learning.24,25 This approach can include articles, supplementary materials (eg, videos), in-person instruction by underrepresented scholars, and consideration of students’ lived experiences in the application of course content.

To provide insight into the application of a curriculum DEI self-reflection process based in culturally relevant pedagogy, this case study describes a faculty-led DEI curriculum self-reflection project at R-SPH. This case study is consistent with recent recommendations for antiracism and cross-cultural curricula in public health 26 and aligned with the mission and vision of R-SPH, which values identifying sources of health inequities and pursuing social justice as an essential means of promoting public health locally and globally. 27 We led this process as part of our charge as faculty, students, and staff serving or supporting the R-SPH Curriculum Committee. We represent a diverse cross-section of the faculty, students, and staff at the school. Of the 10 faculty-level authors, 2 identify as Black or Hispanic/Latino/a, 3 as Asian, and 5 as White; 7 of the faculty members are early career, 2 are midcareer, and 1 is late career; several identify as LGBTQ. Because our work on the committee consists of reviewing and providing feedback on the rigor and effectiveness of curricula, we designed this process as a supplement to our work, focusing on promoting self-reflection among faculty and within concentrations (ie, specialized degree programs) on DEI coverage within and across courses. Although this case study may provide useful insights for many higher education programs, our process may not be possible in public institutions located in states and localities pursuing anti-DEI efforts.

Methods

Development of the DEI Curriculum Self-reflection Tool

The R-SPH Curriculum Committee—which includes early- to late-career faculty and full- and part-time faculty from all departments and concentrations, as well as student, alumni, and staff representatives—began developing the DEI curriculum self-reflection tool in a free association process. During this brainstorming session, committee members emphasized the importance of defining terminology, encouraging evidence-based approaches, listing ways to incorporate and evaluate DEI in course materials, creating a tool for instructors to self-reflect on their courses, and encouraging flexibility on how each instructor approaches DEI.

In addition to the brainstorming session, a subgroup of the committee reviewed how other institutions integrated DEI into their curricula.28-34 Many tools aim to diversify curriculum content and integrate cultural competence into teaching practices. 35 We reviewed the revised curriculum Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training, developed by the Association of American Medical Colleges. 36 From these existing tools, the committee identified, incorporated, and modified questions that were relevant to the R-SPH context. Ultimately our self-reflection tool was informed by the committee brainstorming session and preexisting tools.

The committee discussed the completed draft tool during meetings from July through October 2020. Early- to late-career faculty members of the committee beta-tested the tool with their own courses and provided input on its use. Further modifications were made on the basis of this feedback in November and December 2020, resulting in the final instrument.

Description of the Final DEI Curriculum Self-reflection Tool

The final DEI curriculum self-reflection tool had 2 parts (Supplement). Part 1 was predominantly open-ended to collect information on how the course content and materials addressed DEI from various dimensions. DEI could be represented through content and materials used throughout the course (eg, assignments, assessments, guest speakers, lecture examples, readings, the syllabus, accommodations for diverse student experiences). Part 2 included a 4-point Likert scale to rate the extent to which various DEI practices were reflected in an instructor’s course and syllabus.

To help guide faculty members in their self-reflections, the tool provided examples of DEI practices, such as avoiding scheduling assignments and assessments on religious holidays, providing opportunities for students to indicate the pronunciation or phonetic spelling of their name and their pronouns, and avoiding the generic use of male pronouns.

DEI Curriculum Self-reflection Scoring

The DEI curriculum self-reflection scoring assessed only the presence of DEI or the degree to which instruction, course content, and classroom practices focused on DEI, to systematically categorize and describe DEI within the curricula. The self-reflection tool also included an open-ended section for instructors to reflect on any changes made to the course, the strengths of the course in integrating DEI, areas of growth, and any plans for addressing areas of growth (Supplement).

School-wide Implementation of the DEI Curriculum Self-reflection Tool

Prior to school-wide implementation in fall 2021, we provided training on the DEI curriculum self-reflection tool to all faculty via all-school and department meetings, which included expectations, definitions of DEI, and use of the new tool. Department chairs subsequently organized the self-reflection implementation process for their respective departments and concentrations. 37 The timing of this process aligned with school-wide curriculum review efforts to prepare for the Council on Education for Public Health accreditation process. Because R-SPH faculty progressed through the self-reflection process at different rates, the committee reviewed and provided feedback from October 2021 through June 2023 on 17 concentrations (degree programs) and the 6 core courses. The number of courses reviewed for each concentration ranged from 3 to 15. On average, the committee reviewed 93% (120 of 129) of courses for each concentration and 100% (6 of 6) of core courses. The committee compiled and recorded all comments presented to it by concentration directors and notes from monthly meetings. This project did not involve human data or participants; therefore, per guidelines of the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board, human subjects’ approval was not necessary.

Outcomes: Early Reflections

Implementation

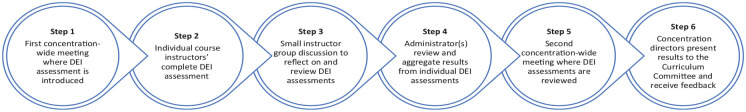

Many faculty greeted the initial implementation of the DEI self-reflection process with enthusiastic support. For example, the first concentration to undergo review engaged in a dynamic process designed by its administrative support staff that was well received and which the committee ultimately recommended for other concentrations. This concentration had the following 6-step progression (Figure):

Figure.

Six-step diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) concentration-level implementation process at Rutgers University, 2020. In step 3, small groups consist of 4 or 5 individual course instructors. In step 4, administrators include concentration directors and their support teams.

Step 1: A concentration meeting in which leadership described the importance and format of the review.

Step 2: An individual assessment period in which instructors completed the self-reflection tool.

Step 3: A small group period in which 4 or 5 faculty members met to share reflections.

Step 4: An administrative review period in which the concentration director and support team compiled and synthesized the results of the individual self-reflections.

Step 5: A follow-up concentration meeting to reflect on the concentration-level assessment with faculty feedback.

Step 6: A presentation to the committee by the concentration director with the results of the review process, followed by feedback from the committee. The concentrations that subsequently engaged in this 6-step process shared feedback on its benefits during committee reports (Box).

Box.

Open-ended feedback from faculty regarding the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) curriculum self-reflection process, compiled from comments presented to the Curriculum Committee by concentration directors and notes from monthly committee meetings, Rutgers University, 2020.

| Positive |

| • It was helpful to do the exercise in small groups. |

| • It was helpful to discuss the assessment with colleagues and learn from their ideas and experiences. |

| • Including a list of the dimensions, examples, and suggestions was helpful. |

| • It is hard work; some things made us uncomfortable. We need to embrace the growth that comes from discomfort. |

| Resistance |

| • Denying the applicability of DEI |

| – It is hard to incorporate DEI in a math-based course. |

| – [DEI] is not particularly relevant to statistical methods. |

| • Claiming that DEI reduces the quality of public health instruction |

| – For disciplines like [quantitative public health field], we need to be careful to not dumb down conceptual aspects on the course being taught. |

| – I’m afraid we are on the side of overkill and recognizing high quality and relevant research by majority race and ethnicity; don’t want to see quality go down. |

| – I caution that we are on a slippery slope with regard to academic freedom. |

Positive Support

Many faculty members were supportive of the DEI curriculum self-reflection tool and 6-step implementation process (Box). These responses included positive reinforcement of the value of the implementation process and growing as instructors. In addition, elements of the implementation process were touted as strengths, such as working with faculty members to make changes to improve their courses (step 3). In the open-ended section of the tool, many faculty members reported making changes to their courses while engaging in the self-reflection exercise. Despite these positive responses, the DEI process also met resistance from within and outside the committee.

Resistance and Responses

Resistance

A review of comments from individual instructors in their self-reflections (step 2), comments from concentration directors summarizing small group discussions (step 3), and notes from committee meetings showed 2 resistance themes: denying the applicability of DEI to disciplines within public health and claiming that DEI reduces the quality of public health instruction (Box). Resistance varied across concentrations. A common comment in the denial of applicability of DEI questioned whether DEI could be applied to content in courses such as quantitative research methods and related disciplines. Typically, these faculty only partially completed the DEI self-reflection tool and responded that it was not applicable to their instruction. Regarding the claim that DEI reduces the quality of public health instruction, faculty comments were quite illustrative: some instructors believed that DEI would harm or “dumb down,” as one participant termed it, the intellectual value of their classes and the quality of their instruction; others thought that it would infringe on their ability to exclude perspectives from socially marginalized communities, thus limiting “academic freedom,” as another expressed it.

Responses

Given evidence showing the benefits of culturally relevant pedagogy for public health education, 24 we were disconcerted by these reactions. We focused on consistent messaging in responding to this resistance. For the critique that DEI may not be applicable to public health instruction, we responded by emphasizing that DEI and culturally relevant pedagogy present opportunities rather than limitations. Accordingly, in line with the objectives of culturally relevant pedagogy, we highlighted opportunities to apply DEI through course content, teaching practices, and student engagement and assessment. As an example of course content, quantitative classes could include independent variables such as racism and other social determinants of health that predict inequitable health outcomes. For teaching practices, we encouraged faculty to use free course materials (eg, articles accessible through the university library) to reduce the cost for students and to work with Rutgers teaching and learning units to ensure that materials are accessible to students with disabilities. For student engagement, we stressed the importance of valuing and uplifting student-driven content as a central aspect of the course, such as incorporating student presentations on areas not covered elsewhere and supporting an interactive and equitable environment in which students are viewed as experts in their experiences. Examples of course assessment included planning assessments through various modalities (eg, online and multimedia content, papers, presentations, representative case studies) or providing students with choices that accommodate diverse learning preferences.

Notwithstanding the universal applicability of DEI in public health, there are areas in which the contributions of women and racial, ethnic, and sexual and gender minority communities have been suppressed or undervalued. We encouraged instructors to incorporate the contributions of these scholars.38,39 We also suggested that faculty members acknowledge where a lack of representation exists in a given field, including confronting why this injustice might exist, offering National Institutes of Health diversity reviews as examples. 40

For critiques claiming that DEI hurts the quality of instruction, we reviewed the evidence to the contrary, including evidence cited in the first page of the self-reflection tool.41-47 Quite simply, there is no quality instruction without DEI. One important approach to these critiques was emphasizing that DEI is an opportunity to improve instruction and student learning through considering a critical and holistic lens to public health education. 38

Lessons Learned

While this DEI self-reflection process has been productive, it is just one aspect of a larger intervention needed to improve DEI in public health education. Although the committee provided instructors with feedback and recommendations, we could not compel instructors to complete the self-reflection or make changes to their teaching practices, let alone require attendance at DEI training programs. Our self-reflection relies on the motivation of instructors, which was and continues to be varied.

We recognize the importance of an ongoing longitudinal curriculum assessment that parallels the ongoing process of DEI consideration that we encourage. The committee has proposed to pursue this assessment through informal and formal processes, including reminders for instructors to review their curricula each semester and revisit whether they have addressed areas of growth identified on their initial self-reflection. We also encourage faculty to regularly meet in groups to continue to reflect on their growth in DEI instruction. We asked concentration directors to provide an update on the DEI process to the committee every 2 years. However, given faculty resistance to our initial process, it is clear that broader institutional intervention is needed. This intervention could include, as examples, required training on DEI instruction for faculty or the addition of DEI-related questions to all course evaluations to gather student perspectives.

Structural interventions are needed to promote DEI throughout the fabric of higher education, such as training doctoral candidates and hiring faculty from previously excluded groups. 48 Without inclusion and empowerment throughout universities, DEI in instruction rings hollow.49-51 We cannot encourage our students to reduce inequities if we are not willing to do the hard work ourselves at the faculty level. Many schools and programs of public health sit within institutions where the acquisition of extramural funding is a cornerstone of hiring, promotion, and tenure; this structure is inherently biased against oppressed groups, systematically excluding those who are not empowered in the funding pathway.52-56

Critical incentives for faculty members are promotion, pay, and tenure. Faculty members may be more willing to participate in the DEI process if it is seen as part of the practices most valued by universities, by being included in student evaluations, promotion reviews, and performance incentives. There may be less reluctance about the self-reflection process if it is a core part of academic instruction and the practice of public health education rather than an add-on.

Conclusion

The DEI curriculum self-reflection at R-SPH occurred during a period of multifaceted actions to remove the consideration of DEI in US educational institutions, 57 including the recent Supreme Court decision to strike down affirmative action in higher education. 58 In a period where denial of historically rooted and currently perpetuated oppression is being used against the communities facing that oppression, the pursuit of critical approaches to public health instruction is more important than ever. 59 As shown in our DEI curriculum self-reflection process, the process of reflection can be fraught, but it is also a fruitful and ultimately worthwhile pursuit. We hope that this case study can be used as a framework for similar efforts in other schools and programs of public health.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-phr-10.1177_00333549241271728 for Developing and Implementing a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Curriculum Self-reflection Process at a School of Public Health by Stacy Davis, Devin English, Stephanie Shiau, Rajita Bhavaraju, Shauna Downs, Gwyneth M. Eliasson, Kristen D. Krause, Emily V. Merchant, Tess Olsson, Michelle M. Ruidíaz-Santiago, Nimit N. Shah, Laura E. Liang and Teri Lassiter in Public Health Reports®

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Drs Davis, English, and Shiau contributed equally to this article.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Devin English, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9400-2063

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9400-2063

Stephanie Shiau, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2944-3406

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2944-3406

Laura E. Liang, DrPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1154-835X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1154-835X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online. The authors have provided these supplemental materials to give readers additional information about their work. These materials have not been edited or formatted by Public Health Reports’s scientific editors and, thus, may not conform to the guidelines of the AMA Manual of Style, 11th Edition.

References

- 1. Chandler CE, Williams CR, Turner MW, Shanahan ME. Training public health students in racial justice and health equity: a systematic review. Public Health Rep. 2022;137(2):375-385. doi: 10.1177/00333549211015665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collins SL, Smith TC, Hack G, Moorhouse MD. Exploring public health education’s integration of critical race theories: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1148959. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1148959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitchell LK, Watson MK, Silva A, Simpson JL. An inter-professional antiracist curriculum is paramount to addressing racial health inequities. J Law Med Ethics. 2022;50(1):109-116. doi: 10.1017/jme.2022.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manalo-Pedro E, Walsemann KM, Gee GC. Whose knowledge heals? Transforming teaching in the struggle for health equity. Health Educ Behav. 2023;50(4):482-492. doi: 10.1177/10901981231177095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perez J, Leonard WR, Bishop V, Neubauer LC. Developing equity-focused education in academic public health: a multiple-step model. Pedagogy Health Promot. 2021;7(4):366-371. doi: 10.1177/23733799211045986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munala L, Allen EM, Beall OM, Phi KM. Social justice and public health: a framework for curriculum reform. Pedagogy Health Promot. 2023;9(4):288-296. doi: 10.1177/23733799221143375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Godley S, Aumiller B, Horigian V, et al. Evidence-based educational practices for public health: how we teach matters. Pedagogy Health Promot. 2021;7(2):89-94. doi: 10.1177/2373379920978421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garbers S, Joseph MA, Jankunis B, O’Brien M, Fried LP. FORWARD: building a model to hold schools of public health accountable for antiracism work. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(10):1086-1088. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anand SS, Pai M. Glocal is global: reimagining the training of global health students in high-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(11):e1686-e1687. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00382-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosales CB, Coe K, Ortiz S, Gámez G, Stroupe N. Social justice, health, and human rights education: challenges and opportunities in schools of public health. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(1):126-130. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Derreth RT, Jones VC, Levin MB. Preparing public health professionals to address social injustices through critical service-learning. Pedagogy Health Promot. 2021;7(4):354-357. doi: 10.1177/23733799211007183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morse M, Loscalzo J. Creating real change at academic medical centers—how social movements can be timely catalysts. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):199-201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2002502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gray DM, Joseph JJ, Glover AR, Olayiwola JN. How academia should respond to racism. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(10):589-590. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0349-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Allen AM, Abram C, Pothamsetty N, et al. Leading change at Berkeley Public Health: building the Anti-racist Community for Justice and Social Transformative Change. Prev Chronic Dis. 2023;20:E48. doi: 10.5888/pcd20.220370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harriot M. A timeline of events that led to the 2020 “Fed Up”-rising. The Root. 2020. Accessed December 13, 2023. https://www.theroot.com/a-timeline-of-events-that-led-to-the-2020-fed-up-rising-1843780800

- 16. Bowleg L. Perspectives from the social sciences: critically engage public health. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):15-16. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sullivan N. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. NYU Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Collins PH. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. New Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ladson-Billings G. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am Educ Res J. 1995;32(3):465-491. doi: 10.2307/1163320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ladson-Billings G. Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: aka the remix. Harvard Educ Rev. 2014;84(1):74-84. doi: 10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gay G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice (Multicultural Education Series). 3rd ed. Teachers College Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ladson-Billings G. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy: Asking a Different Question (Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies Series). Teachers College Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Byrd CM. Does culturally relevant teaching work? An examination from student perspectives. SAGE Open. 2016;6(3):215824401666074. doi: 10.1177/2158244016660744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Verbree AR, Isik U, Janssen J, Dilaver G. Inclusion and diversity within medical education: a focus group study of students’ experiences. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04036-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Magana L, Biberman D. Training the next generation of public health professionals. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(4):579-581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rutgers School of Public Health. About us. 2024. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://sph.rutgers.edu/about

- 28. Utah Center for Teaching and Learning Excellence. Developing an inclusive syllabus. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://cte.utah.edu/instructor-education/inclusive-teaching/resources/inclusive_syllabus/Developing%20an%20Inclusive%20Syllabus_Website%20landing%20copy.pdf

- 29. Cornell University Center for Teaching Innovation. Incorporating diversity. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://teaching.cornell.edu/resource/incorporating-diversity

- 30. University of Kansas Center for Teaching Excellence. Inclusive syllabi. 2024. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://cte.ku.edu/inclusive-syllabi

- 31. University of Denver Office of Teaching and Learning. Inclusive excellence and our teaching: checklist of inclusive excellence (IE) in syllabi. Accessed June 1, 2020. http://otl.du.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/IE-Syllabi-checklist.pdf

- 32. University of Washington. Developing a reflective teaching practice. 2024. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://teaching.washington.edu/reflect-and-iterate/developing-a-reflective-teaching-practice

- 33. Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. Diversity and inclusion. 2021. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/FacultyResources/Diversity-Inclusion

- 34. University of California Berkeley, Division of Equity and Inclusion. Strategic planning for equity, inclusion, and diversity. 2015. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://diversity.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/academic-strategic-toolkit-final.pdf

- 35. Smith DG. Diversity’s Promise for Higher Education: Making It Work. 3rd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lie D, Boker J, Crandall S, et al. A revised curriculum tool for assessing cultural competency training (TACCT) in health professions education. MedEdPORTAL. 2009;5:3185. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.3185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rutgers School of Public Health. Degree programs. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://sph.rutgers.edu/academics/degree-programs

- 38. Fuentes MA, Zelaya DG, Madsen JW. Rethinking the course syllabus: considerations for promoting equity, diversity, and inclusion. Teaching Psychol. 2021;48(1):69-79. doi: 10.1177/0098628320959979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stein S, de Oliveira Andreotti V. Higher education and the modern/colonial global imaginary. Cult Stud Crit Methodol. 2017;17(3):173-181. doi: 10.1177/1532708616672673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Institutes of Health. Chief Officer for Scientific Workforce Diversity (COSWD). 2024. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://diversity.nih.gov

- 41. Day L, Beard KV. Meaningful inclusion of diverse voices: the case for culturally responsive teaching in nursing education. J Prof Nurs. 2019;35(4):277-281. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hammond Z. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin/Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ladson-Billings G. But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Pract. 1995;34(3):159-165. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gay G. Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. J Teach Educ. 2002;53(2):106-116. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hill ML, Ladson-Billings G. Beats, Rhymes, and Classroom Life: Hip-Hop Pedagogy and the Politics of Identity. Teachers College Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Phillips KW. How diversity makes us smarter. Scientific American. October 1, 2014. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter

- 47. Gurin P, Dey EL, Hurtado S, Gurin G. Diversity and higher education: theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harvard Educ Rev. 2002;72(3):330-366. doi: 10.17763/haer.72.3.01151786u134n051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cosgriff-Hernandez EM, Aguado BA, Akpa B, et al. Equitable hiring strategies towards a diversified faculty. Nat Biomed Eng. 2023;7(8):961-968. doi: 10.1038/s41551-023-01076-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gibbs KD, Basson J, Xierali IM, Broniatowski DA. Decoupling of the minority PhD talent pool and assistant professor hiring in medical school basic science departments in the US. Elife. 2016;5:e21393. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gibbs KD, McGready J, Bennett JC, Griffin K. Biomedical science PhD career interest patterns by race/ethnicity and gender. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gasman M, Abiola U, Travers C. Diversity and senior leadership at elite institutions of higher education. J Divers Higher Educ. 2015;8(1):1-14. doi: 10.1037/a0038872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science. 2011;333(6045):1015-1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/Black scientists. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaaw7238. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ginther DK, Kahn S, Schaffer WT. Gender, race/ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 research awards: is there evidence of a double bind for women of color? Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1098-1107. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lauer MS, Roychowdhury D. Inequalities in the distribution of National Institutes of Health research project grant funding. eLife. 2021;10:e71712. doi: 10.7554/eLife.71712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. National Institutes of Health. Racial disparities in NIH funding. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://diversity.nih.gov/building-evidence/racial-disparities-nih-funding

- 57. Moody J. The new conservative playbook on DEI. Inside Higher Ed. 2023. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2023/02/07/desantis-debuts-new-conservative-playbook-ending-dei

- 58. Students for Fair Admissions, Inc v President & Fellows of Harvard College. 600 US; 2023. Accessed July 9, 2024. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf

- 59. Heller JC, Fleming PJ, Petteway RJ, Givens M, Pollack Porter KM. Power up: a call for public health to recognize, analyze, and shift the balance in power relations to advance health and racial equity. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(10):1079-1082. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-phr-10.1177_00333549241271728 for Developing and Implementing a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Curriculum Self-reflection Process at a School of Public Health by Stacy Davis, Devin English, Stephanie Shiau, Rajita Bhavaraju, Shauna Downs, Gwyneth M. Eliasson, Kristen D. Krause, Emily V. Merchant, Tess Olsson, Michelle M. Ruidíaz-Santiago, Nimit N. Shah, Laura E. Liang and Teri Lassiter in Public Health Reports®