Abstract

Background:

Women’s artistic gymnastics (WAG) is a complex aesthetic sport in which athletes start at a young age and are exposed to high loads during their careers. Little is known about the external and internal training load characteristics among elite young gymnasts.

Hypothesis:

High training loads, with variations over the weeks, are expected. There is a relationship between external and internal load variables.

Study Design:

Cohort study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 3.

Methods:

Seven elite-level Brazilian youth artistic gymnasts (age, 11.3 ± 0.4 years; mass, 33.0 ± 7.0 kg; height, 137.7 ± 10.6 cm; experience, 4.0 ± 1.2 years) participated in this study. Five nonconsecutive microcycles were monitored. Both external and internal training loads were quantified by counting the number of elements in video recordings of training sessions and by the session rating of perceived exertion method.

Results:

A total of 168 individual training sessions were monitored. The microcycle that succeeded the main competition showed a significantly lower training load than ≥3 of the other 4 microcycles for all training load variables, except for vault elements, of which microcycle 4 was inferior only to the microcycle before the competition. Significant correlations were found between weekly internal training load and the total of elements and elements performed on uneven bars.

Conclusion:

Youth women’s artistic gymnasts present fluctuations in external and internal training load variables over the weeks close to a major competition. Training load management in this sport must consider the specificity of each apparatus, as they have different demands and training load behaviors.

Clinical Relevance:

A better comprehension of external and internal training loads in youth WAG and its apparatuses can benefit coaches and support staff and provide more information to overcome the challenge of training load management in gymnastics.

Keywords: gymnastics, load management, WAG, workload, young athletes

Training load management is a broad expression comprising several variables, procedures, stages, and systems. 11 Collectively, these aim to understand the training dose-response relationship, contribute to athletes’ performance improvement, and minimize negative outcomes. 13 From this perspective, constantly monitoring external (ie, what the athlete has done) and internal (ie, how the athlete’s organism responds during the stimulus) training loads is an essential part of this puzzle.11,15 Despite extensive scientific and technological advancements in this topic over the past decades, it remains a challenge in complex aesthetic sports such as gymnastics. 18

Women’s artistic gymnastics (WAG) is among the 8 disciplines recognized by the International Gymnastics Federation and is one of the most traditional Olympic sports in the modern era. 3 It is a dynamic and effortful sport that involves 4 different apparatuses (vault, uneven bars, balance beam, and floor exercise). 14 Each apparatus presents specific demands and a particular set of difficulty elements,14,16 combining strength, power, flexibility, artistry, and technical excellence. Considering these nuances and the lack of applied scientific evidence on training load monitoring in WAG, precisely measuring gymnasts’ external and internal load can be arduous.

Traditionally, research on training load in WAG has focused on quantifying external training load, mainly by addressing training hours, frequency of skills, and impact forces.2,18,22 While relevant, external training load variables alone are insufficient to fully comprehend the training effects and consequent performance outcomes. Some studies investigated the internal training load using the session rating of perceived exertion (session-RPE) method in WAG9,19,24 and in other gymnastics disciplines, such as men’s artistic gymnastics, 23 rhythmic gymnastics, 7 and trampoline. 20 In general, the literature points out that gymnasts are exposed to high training loads from a young age, train dozens of hours per week during their careers, and experience elevated impact forces when performing skills that must be repeated innumerable times to achieve technical proficiency and consistency.3,22

Due to this peculiar training context, it has been suggested that artistic gymnastics presents high injury incidence and prevalence.4,5,22 Data from 3 editions of the Olympic Games indicate that WAG had the greatest incidence of injury among all gymnastics disciplines. 5 A systematic review of 22 studies on injury epidemiology and risk factors in competitive artistic gymnastics showed that injury incidence ranged between 2.5 and 3.6 injuries per gymnast per year. 4 Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that 91% of elite-level WAG athletes experienced ≥1 injury per season. 5 Lower limb acute and overuse injuries are common in WAG,4,5 and floor exercise is the apparatus associated most frequently with injury, due primarily to landing-related skills.3,4,22 Therefore, understanding the training load in WAG through an apparatus-based approach is paramount. 18

More information on how external training load is distributed among the WAG apparatuses, in conjunction with internal training load measures, could help minimize the risks of negative outcomes in this sport. Gymnastics coaches, practitioners, support staff, and sports scientists can benefit from a better understanding of external and internal training loads in artistic gymnastics apparatuses. However, there is still a lack of longitudinal research investigating external and internal training load variables in WAG. Hence, the aim of the study was to quantify and analyze both external and internal training load in elite youth women’s artistic gymnasts.

Methods

Participants

Seven elite-level youth artistic gymnasts (age, 11.3 ± 0.4 years; mass, 33.0 ± 7.0 kg; height, 137.7 ± 10.6 cm; experience in WAG, 4.0 ± 1.2 years) from a Brazilian club participated in this study. The gymnasts competed in the highest-level national WAG championship for their age group (11-12 years). It is worth mentioning that, over the last 2 decades, Brazil has achieved international recognition in WAG, winning several individual and team medals in World Cups, World Championships, and, more recently, in the Olympic Games. The athletes were properly familiarized with the monitoring tools before data collection. Written informed assent and consent were obtained from each gymnast and their parents/tutors, respectively. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Research with Humans of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (CAAE 06130019.5.0000.5147).

Study Design

Five nonconsecutive microcycles were monitored within 10 weeks of training and competition (Figure 1). In each microcycle, 5 consecutive training sessions (eg, Monday to Friday or Tuesday to Saturday) were monitored, totaling 25 group sessions. The gymnasts had only 1 training session per day during the study period. The sessions occurred in the gymnasium and usually consisted of warm-up, specific physical preparation (strength and flexibility exercises), and technical training on the WAG apparatuses (ie, vault, uneven bars, balance beam, and floor exercise).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the microcycles and timeline of data collection. M, microcycle.

External Training Load

External training load was quantified based on the repetitions of preselected WAG elements in each apparatus. It was obtained by video recording the training sessions using 3 cameras (Canon Power Shot SX420 IS, GoPro Hero Silver 3, and GoPro Hero Silver 4, GoPro Inc). The cameras were positioned to capture the entire interior area of the gymnasium, and this position remained the same for all monitored training sessions. During video analysis, each technical element performed during apparatus training was counted and included in a spreadsheet. The elements were chosen based on the current technical regulation of the Brazilian National Championship for their age group (Table 1). The total elements comprised the sum of all elements performed during that microcycle.

Table 1.

Code of technical elements counted for each apparatus

| Vault | Uneven Bars | Balance Beam | Floor Exercise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements’ code as in the Tables of Elements in 2022-2024 FIG WAG Code of Points | 1.00 1.40 3.10 4.10 4.20 |

1.101 2.201 2.204 3.201 3.206 3.404 4.101 4.208 5.105 5.308 6.104 6.205 |

1.201 1.314 1.417 2.108 2.112 2.202 2.302 2.305 2.405 3.101 4.108 5.208 5.204 5.408 5.409 6.104 6.204 |

1.101 1.201 1.207 1.304 1.305 1.307 1.309 2.101 2.202 2.203 2.207 3.105 3.106 3.107 4.101 4.103 4.104 4.205 4.302 5.101 5.104 5.201 5.301 5.402 |

| Total of selected elements | 5 | 12 | 17 | 24 |

FIG, International Federation of Gymnastics; WAG, women’s artistic gymnastics.

Internal Training Load

Internal training load was determined using the session-RPE method. 10 The session internal training load was calculated as the product of the session duration (in minutes) and the session-RPE score (0-10) and reported in arbitrary units (AU). The total weekly internal training load (wITL) consisted of the sum of all session loads during that microcycle.

Training load variables were assumed to be zero on days off and training days without data collection. The proportion of data missing was 11%. Data were missed randomly from different athletes on distinct days and microcycles. The daily team means of each missing variable and derivate measures were adopted as the missing value imputation method. 12

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as means and standard deviations. Nonparametric tests were performed due to non-normality and nonhomogeneity of variances in the dataset. Therefore, Friedman test with Kendall (W) estimated effect size was used to compare repeated outcome measures at each microcycle time point. The Wilcoxon 2-sample paired signed-rank test was adopted for post hoc comparisons, and the effect size was estimated by matched-pairs rank-biserial correlation (r). Effect size magnitude was categorized as “very small” (<0.1), “small” (0.1-0.3), “moderate” (0.3-0.5), and “large” (>0.5). 6 Repeated measures correlation coefficient was used to analyze the relationships between internal and external training load variables. 1 The statistical significance was set at P < 0.05; 95% CIs were calculated by bootstrapping (1000 from the original data) using the normal approximation criterion. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical programming language (Version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

A total of 168 individual training sessions were monitored. The daily means of elements performed in each apparatus were vault 9 ± 7, uneven bars 57 ± 34, balance beam 59 ± 36, floor exercise 65 ± 32, and the total of elements 191 ± 68. Considering the number of selected elements (Table 1), each distinct vault element was performed around 1.5 times per training session, uneven bars 4.8, balance beam 3.5, and floor exercise 2.7. The mean session duration was 234 ± 12 minutes, the session-RPE score was 2.89 ± 0.79, and the daily internal training load was 678 ± 193 AU.

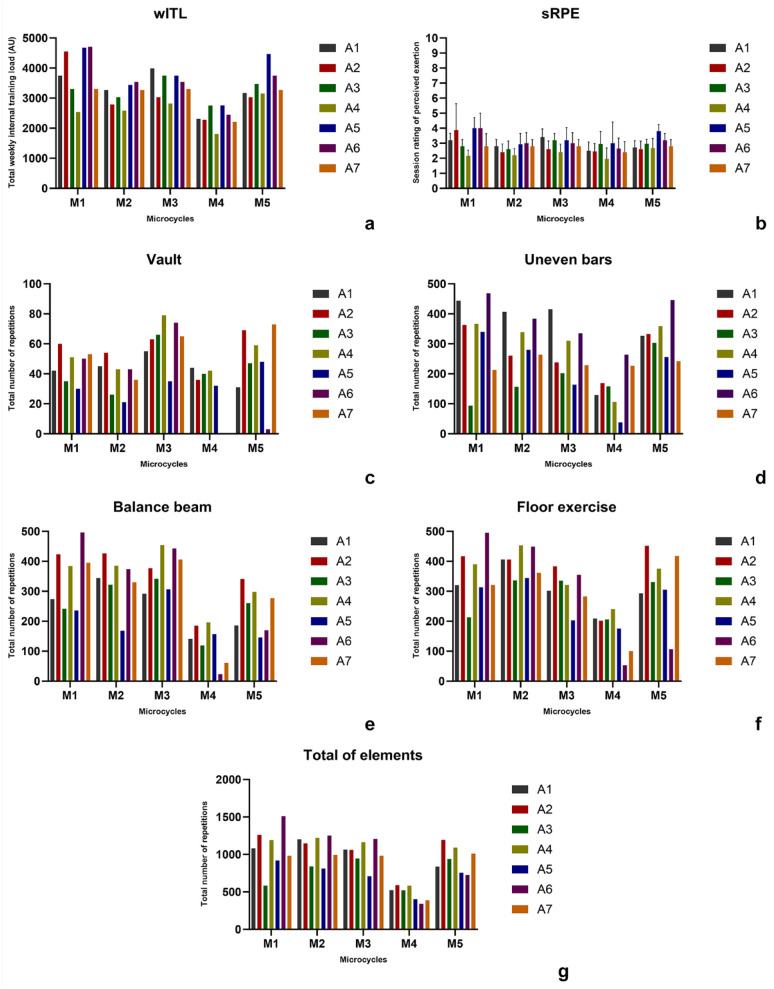

Table 2 presents internal and external training load variables for each microcycle. M4 showed a significantly lower training load than ≥3 of the other 4 microcycles for all variables, except for vault elements, for which M4 was inferior only to M3. Figure 2 displays individual wITL, average session-RPE, the number of repetitions in each apparatus, and the total number of elements for each athlete in every microcycle. Distinct load distribution among the athletes and apparatuses can be noticed over the 5 microcycles.

Table 2.

Weekly internal and external training load variables in each microcycle a

| Training Load Variables | Microcycles | Chi-Squared | Kendall W (95% CI) | Post Hoc Test [Effect Size; 95% CI] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | ||||

| wITL, AU | 3833 ± 841 | 3131 ± 349 | 3454 ± 423 | 2370 ± 330 | 3475 ± 500 | 19.2** | 0.69 (0.5-0.77) |

M4 < M1*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M2*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M3*[0.90; 0.9-0.93], M5*[0.89; 0.9-0.91] M2 < M1*[0.77; 0.39-0.91], M3*[0.87; 0.74-0.92] |

| sRPE | 3.26 ± 0.72 | 2.68 ± 0.29 | 2.94 ± 0.36 | 2.56 ± 0.36 | 2.97 ± 0.42 | 13.8** | 0.49 (0.27-0.57) |

M4 < M1*[0.83; 0.51-0.91], M3*[0.89; 0.9-0.92], M5*[0.89; 0.9-0.91] |

| Vault | 46 ± 11 | 38 ± 12 | 62 ± 14 | 28 ± 19 | 47 ± 24 | 14.3** | 0.51 (0.18-0.72) |

M3 > M1*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M2*[0.89; 0.9-0.92], M4*[0.89; 0.9-0.91] M1 > M2*[0.83; 0.52-0.91] |

| Uneven bars | 327 ± 132 | 299 ± 85 | 270 ± 87 | 156 ± 75 | 324 ± 68 | 10.1* | 0.39 (0.01-0.61) |

M4 < M2*[0.83; 0.51-0.91], M3*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M5*[0.89; 0.9-0.92] |

| Balance beam | 350 ± 100 | 336 ± 82 | 374 ± 64 | 126 ± 64 | 240 ± 73 | 21.1** | 0.75 (0.61-0.82) |

M4 < M1*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M2*[0.90; 0.9-0.93], M3*[0.89; 0.9-0.92], M5*[0.83, 0.52-0.91] M5 < M1*[0.83; 0.5-0.91], M2*[0.89; 0.9-0.92], M3*[0.89; 0.9-0.91] |

| Floor exercise | 353 ± 90 | 394 ± 48 | 312 ± 58 | 169 ± 67 | 326 ± 113 | 19.1** | 0.68 (0.5-0.78) |

M4 < M1*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M2*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M3*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M5*[0.89; 0.9-0.91] M3 < M2*[0.89; 0.9-0.91] |

| Total of elements | 1076 ± 292 | 1066 ± 184 | 1019 ± 165 | 479 ± 101 | 936 ± 175 | 16.1** | 0.58 (0.32-0.71) |

M4 < M1*[0.89; 0.9-0.92], M2*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M3*[0.89; 0.9-0.91], M5*[0.89; 0.9-0.91] |

AU, arbitrary units; M, microcycle; sRPE, session rating of perceived exertion; wITL, weekly training load.

Data are shown as mean ± SD. * and ** denote significant difference at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Individual weekly internal training load, (b) average session-RPE, (c-f) number of repetitions in each apparatus, and (g) total number of elements over the 5 microcycles. A, athlete; M, microcycle; sRPE, session rating of perceived exertion; wITL, weekly internal training load.

The analysis of individual weekly measures resulted in significant and positive correlations between wITL and total of elements (r = 0.77; P < 0.01; 95% CI 0.58-0.88) and wITL and uneven bars (r = 0.76; P < 0.01; 95% CI 0.60-0.87).

Discussion

This study aimed to quantify and analyze external and internal training load in young WAG gymnasts. We found a variation of training load among 5 nonconsecutive microcycles, albeit with a significantly diverse pattern for the number of vault element repetitions. There is a correlation between internal training load, the total number of elements performed, and the repetitions on uneven bars.

On average, the training sessions in our investigation lasted approximately 4 hours, the session intensity was commonly perceived as moderate (session-RPE score circa 3), and the daily internal training load was around 678 AU. Only a few studies have measured internal training load in youth WAG using the session-RPE method.9,24 However, our results are in line with the internal training load of an under-13 group of elite Belgian artistic gymnasts. 9 Compared with research conducted with older gymnasts, our study’s internal and external training loads seem much lower. Sands 22 states that national-level artistic gymnasts in the United States train 5 to 6 hours and perform from 700 to 1300 elements per day, while we found a total daily repetition of selected elements of 191. This training load increase across their careers is expected, 9 as the number and difficulty level of skills tend to expand, as well as training duration, frequency, and intensity. Moreover, as we have monitored only a few weeks relatively close to the main championship, a longitudinal investigation of an entire season could find different training load values for young competitive gymnasts.

The microcycle that succeeded the main competition (M4) presented a reduced training load compared with 3 or 4 other microcycles monitored. Decreasing the training load after important competitions is a common practice in most sports with a similar championship format (ie, short events), generally implemented to promote recovery after concentrated high loads. Debien et al 7 described the training load of a 43-week season in elite rhythmic gymnastics and observed a lower internal training load in the weeks after competitive events. In contrast, a surprising finding in our study was that M3 did not present a significant decrease in training load as it was the microcycle preceding a major competitive meeting. Although tapering has shown to be an interesting strategy in gymnastics, 21 there is evidence of rising training loads in the weeks before relevant competitions in Olympic gymnastics disciplines.7,20,22 This training load pattern may be perceived more easily in aesthetic sports due to the challenges of implementing successful training load management, 8 or could also be a consequence of a regular practice of increasing the number and quality of repetitions of elements and routines, elevating both training volume and intensity just before competing.

As an exception to the abovementioned training load distribution, vault elements have shown higher training loads in M3 (before competition) compared with M1 and M2, which took place 5 and 3 weeks before the competition, respectively. To 5 of the 7 participants, M3 displayed the highest volume of repetitions on vault (Figure 2c). It is worth noting that vault is the only apparatus where gymnasts perform an isolated skill, with each repetition lasting approximately 5 seconds. 16 It also explains why there are fewer selected elements (Table 1) and lower average daily and weekly repetitions than the other apparatuses in our investigation. Regardless, a comparable decline in training load in all apparatuses during M3 could be expected. In contrast to our study, other authors have collected the session-RPE after each part of the WAG training and have found that less time is dedicated to vault, which represented a minor percentage (~5%) of the total internal training load when compared with uneven bars (~24%), balance beam (~17%), and floor exercise (~15%). 24 Vault does not impose such a high cardiovascular demand (ie, physiological load measured through heartrate) as the other apparatuses,14,16 so a tool capable of accurately measuring the biomechanical load during vault elements could be a more adequate strategy to understand the training load in this apparatus.16,25

WAG is an individual aesthetic sport. Ideally, an individualized approach should be implemented during the entire training load management process.21,22 In youth gymnastics, coaches usually prescribe similar training sessions to the team based on the number of repetitions correctly executed. Depending on the gymnasts’ technical and physical capacities, and on which elements are selected for their routines in each apparatus, a similar prescription may result in entirely different external and internal training loads. This can be observed in Figure 2, where some variables presented a great range among the gymnasts. In a distinct training context, Patel et al 19 also found variations in weekly training load distributions among the gymnasts in their study. In this regard, coaches and practitioners in WAG might consider adopting individualized and multifactorial training load management to improve gymnasts’ performance based on their personal needs and to minimize the risks of negative outcomes. Future studies are encouraged to analyze the use of wearable devices (eg, inertial measurement units) alongside the session-RPE in more extended periods across the season, also considering the specificities of each apparatus in WAG. 18

Our results revealed significant correlations between wITL and the total number of elements performed. While a relationship between external and internal training load variables is expected, we must also be able to note differences as they represent distinct constructs in the training process. 15 Although our method of quantifying external training load is laborious and impractical, this result reinforces previous research in regards to the useful application of the session-RPE as an efficient tool to monitor internal training load in complex sports, such as gymnastics disciplines.2,7,17,19

In addition, the elements repeated on uneven bars were also correlated with wITL. The literature shows that uneven bars are physiologically more demanding (ie, higher heart rate) than balance beam and vault,14,16 which could partially explain this positive correlation with internal training load measures. 25 A presentation of young gymnasts on the uneven bars lasts around 30 seconds. 16 However, unlike the others, this apparatus has a predominantly upper limb demand. 3 The skills used on floor exercise, balance beam, and vault are somewhat transferable, which does not apply to elements performed on uneven bars. 22 From this perspective, more time is expected to be dedicated to this particular apparatus during the earlier stages of a gymnast’s career to develop basic technical capacities. Trucharte and Grande 24 observed that uneven bars produced a higher accumulated internal training load in 4 weeks, essentially due to longer durations, as well as an elevated percentual contribution (~24%) to the session load compared with the other training components. A great number of repetitions is necessary to master specific skills. Nevertheless, this process should be progressive and monitored carefully to guarantee the development of physical, technical, and psychological capacities for each apparatus and to avoid an uncontrolled overload on the body structures of young gymnasts. 22 Researchers are encouraged to continuously investigate training load in WAG by measuring both the internal and external load of each apparatus separately to better comprehend their differences and influences on the overall session load.

Limitations

Although essential for bridging the gap between science and practice in the gymnasium, the results of the current pilot study should not be generalized and must be interpreted with caution. Our findings are based on the training load monitoring of only 7 young gymnasts from the same club and do not represent the characteristics of all clubs working with youth elite WAG. A limitation of our work was that we monitored the athletes only for 5 nonconsecutive weeks close to competition. A data collection encompassing longer training phases and monitoring every week would offer more insightful information about the training load in this population.

Conclusion

Youth WAG athletes present fluctuations in external and internal training load variables over weeks close to a major competition. Despite being correlated, practitioners and researchers should attempt to measure both external and internal training load in WAG if possible. Vault demonstrated a singular training load variation, while uneven bars were the only apparatus correlated with internal training load measures. In conclusion, training load management in this sport must consider the specificity of each apparatus, as they have different demands and more than just the number of repetitions might be required to understand the real training stimulus.

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Bakdash JZ, Marusich LR. Repeated measures correlation. Front Psychol. 2017;8:456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burt L, Naughton G, Higham DG, Landeo R. Training load in pre-pubertal female artistic gymnastics. Sci Gymnast J. 2010;2(3):5-14. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caine DJ, Russell K, Lim L. Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science - Gymnastics. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campbell RA, Bradshaw EJ, Ball NB, Pease DL, Spratford W. Injury epidemiology and risk factors in competitive artistic gymnasts: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(17):1056-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charpy S, Billard P, Dandrieux PE, Chapon J, Edouard P. Epidemiology of injuries in elite women’s artistic gymnastics: a retrospective analysis of six seasons. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2023;9(4):e001721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Debien PB, Miloski B, Werneck FZ, et al. Training load and recovery during a pre-Olympic season in professional rhythmic gymnasts. J Athl Train. 2020;55(9):977-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Debien PB, Timoteo TF, Gabbett TJ, Bara Filho MG. Training-load management in rhythmic gymnastics: practices and perceptions of coaches, medical staff, and gymnasts. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022;17(4):530-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dumortier J, Mariman A, Boone J, et al. Sleep, training load and performance in elite female gymnasts. Eur J Sport Sci. 2018;18(2):151-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foster C, Florhaug J, Franklin J, et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(1):109-115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gabbett TJ. The training-performance puzzle: how can the past inform future training directions? J Athl Train. 2020;55(9):874-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Griffin A, Kenny IC, Comyns TM, et al. Training load monitoring in team sports: a practical approach to addressing missing data. J Sports Sci. 2021;39(19):2161-2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Impellizzeri FM, Shrier I, McLaren SJ, et al. Understanding training load as exposure and dose. Sport Med. 2023;53(9):1667-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Isacco L, Ennequin G, Cassirame J, Tordi N. Physiological pattern changes in response to a simulated competition in elite women's artistic gymnasts. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(10):2768-2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jeffries AC, Marcora SM, Coutts AJ, Wallace L, McCall A, Impellizzeri FM. Development of a revised conceptual framework of physical training for use in research and practice. Sport Med. 2022;52(4):709-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marina M, Rodríguez FA. Physiological demands of young women’s competitive gymnastic routines. Biol Sport. 2014;31(3):217-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minganti C, Capranica L, Meeusen R, Amici S, Piacentini MF. The validity of session rating of perceived exertion method for quantifying training load in teamgym. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(11):3063-3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patel TS, Faustin M, Katz NB, et al. Monitoring training load in artistic gymnastics. https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2022/09/30/monitoring-training-load-in-artistic-gymnastics/ Accessed November 15, 2023.

- 19. Patel TS, McGregor A, Cumming SP, Williams K, Williams S. Return to competitive gymnastics training in the UK following the first COVID-19 national lockdown. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2022;32(1):191-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patel TS, McGregor A, Williams K, Cumming SP, Williams S. The influence of growth and training loads on injury risk in competitive trampoline gymnasts.J Sports Sci. 2021;39(23):2632-2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sanchez AMJ, Galbès O, Fabre-Guery F, et al. Modelling training response in elite female gymnasts and optimal strategies of overload training and taper.J Sports Sci. 2013;31:1510-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sands WA. Injury prevention in women’s gymnastics. Sport Med. 2000;30(5):359-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sartor F, Vailati E, Valsecchi V, Vailati F, La Torre A. Heart rate variability reflects training load and psychophysiological status in young elite gymnasts. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(10):2782-2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trucharte P, Grande I. Analysis and comparison of training load between two groups of women’s artistic gymnasts related to the perception of effort and the rating of the perceived effort session. Sci Gymnast J. 2021;13(1):19-33. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vanrenterghem J, Nedergaard NJ, Robinson MA, Drust B. Training load monitoring in team sports: a novel framework separating physiological and biomechanical load-adaptation pathways. Sport Med. 2017;47(11):2135-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]