Abstract

Spinal arteriovenous fistulas (SAVFs) are the most common type of vascular malformation of the spine in adult patients. They can lead to acute or progressive myelopathy due to venous congestion of the medullary veins. While most SAVFs are acquired, their pathophysiology remains unclear. The natural history of the disease and its clinical presentation are highly influenced by the location of the fistula and various factors may trigger sudden neurological decline. We present a case of a patient who developed a complete spinal cord injury after a lumbar nerve root block, likely due to an undiagnosed SAVF. The patient underwent endovascular embolization, resulting in a complete recovery of neurological function.

Keywords: Angiography, dural fistula, spine, arteriovenous fistula

Case

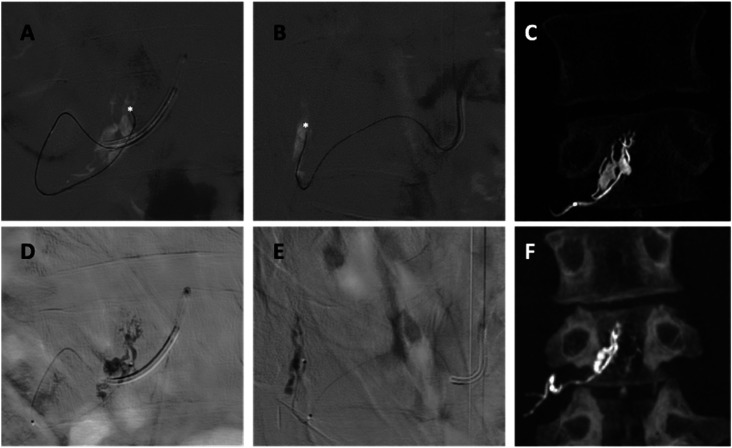

A 63-year-old man presented with right L3 radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was reported by a neuroradiologist indicating multilevel spondylolysis and a right caudal migrated L2–L3 disc herniation (Figure 1). The patient underwent a fluoroscopy-guided extraforaminal nerve root block with 3 mL of bupivacaine (2.5 mg/mL) and 1 mL of triamcinolone (40 mg/mL), which initially relieved his symptoms. However, 6 h later, he experienced progressive weakness, urinary incontinence, and sensory and motor function loss. Neurological examination revealed a complete T10 spinal cord injury ASIA-A. MRI showed intramedullary edema and profuse perimedullary flow voids, raising suspicion of SAVF, which was further confirmed by digital subtraction angiography (Figure 2). A spinal angiogram was performed within the first 24 h from symptom onset. Arterial supply arose from the ipsilateral L3 radicular artery at the neural foramen level throughout two small-caliber retrocorporeal arteries that communicated with a venous pouch located midway between the right lateral recess and neural foramen, confirming spinal epidural arteriovenous fistulas (SEAVFs). Although vascular interconnections linking epidural venous plexus and intradural spinal surface veins exist, they remain angiographically occult in normal conditions. In this case, the SEAVF led to hyperflow and venous hypertension that were transmitted upstream through an emissary's vein from the venous pouch to the ventral superficial medullary veins, displaying arterialized, congestive, and tortuous characteristics (Figure 3). Superselective microcatheterization of the two arterial feeders was performed to reach the fistula point, subsequently embolized with Glue (33% n-butyl cyanoacrylate mixed with Lipiodol), (Figures 4 and 5). Partial occlusion of the venous pouch was tolerated during the glue injection. Angiographic controls demonstrated complete exclusion of the SEAVF and venous outflow restoration through the Batson's plexus. The patient underwent a specialized spinal cord rehabilitation program and was discharged from the hospital two months later. At four-month follow-up, MRI showed partial remission of the intramedullary edema and complete resolution of the vascular engorgement (Figure 6(a)). At one-year follow-up, the MRI revealed complete remission of the medullary edema and no signs of fistula recurrence (Figure 6(b)). The patient was physically active, walked independently, and fully recovered bladder function, but presented with residual neuropathic pain. At a two-year follow-up, no further neurological or radiological changes were observed (Figure 6(c)).

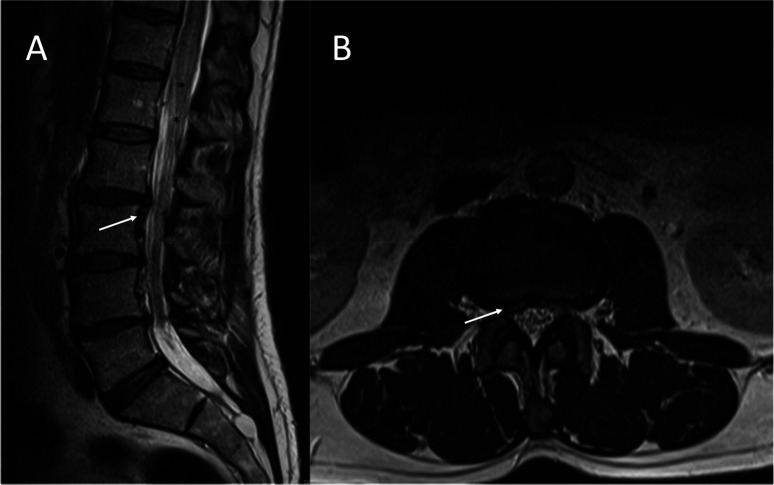

Figure 1.

Lumbosacral magnetic resonance imaging prior to lumbar puncture. A sagittal (A) and axial (B) T2-weighted were reported as revealing a right caudal migrated L2–L3 disc herniation (white arrows). In retrospect, this was an underdiagnosed spinal epidural arteriovenous fistula, and abnormal flow voids (black asterisks) went unnoticed.

Figure 2.

Lumbosacral magnetic resonance imaging following lumbar puncture. A sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) image shows intramedullary edema extending from T7 to the spinal cord cone (black asterisks from T8 to cord cone) and perimedullar vascular engorgement (white arrow).

Figure 3.

Spinal catheter angiography. (A) and (B) Selective right L3 radicular artery angiogram in the AP and L views, respectively. A Simmons 5F catheter is located at the ostium of the artery (white arrow). A venous pouch (white circle) is observed, from which a bridging vein (black arrow) emerges, communicating with the ventral superficial medullary veins (black dotted box). (C) and (D) 3D reconstruction images in the AP and L views, respectively. Road map in the anteroposterior (E) and lateral views (F) showing two retrocorporeal arteries (white arrows) shunting the venous pouch (white circle). Augmented AP (G) and L (H) views displayed the fistulous points (white asterisks). 3D axial reconstruction image shows the arterial feeders joining the venous pouch at the lateral recess.

AP: anterioposterior; 3D: three-dimensional; L: lateral.

Figure 4.

AP (A), L (B) views, and 3D reconstruction image (C) of the arterial feeders microcatheterization (white asterisks). Fluoroscopic AP (D), L (E), and 3D reconstruction images (F) show the glue cast in the venous pouch.

AP: anteroposterior; L: lateral; 3D: three-dimensional.

Figure 5.

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) views of the post-embolization control. Selective right L3 radicular artery angiogram demonstrated complete exclusion of the fistula (white circle).

Figure 6.

Follow-up lumbosacral STIR MRI. At 4 months (A) intramedullary extended from T10 to the spinal cord cone (black asterisks). At 1-year (B) and 2-year follow-ups (C), MRI revealed complete remission of both the medullar edema and vascular engorgement.

STIR: short tau inversion recovery; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Discussion

Over half of spinal arteriovenous fistulas (SAVFs) are initially misdiagnosed on MRIs. 1 Misinterpretation of clinical and radiological features of SAVFs with other concurrent spine conditions can result in invasive treatments. 2 Spinal invasive treatments can trigger a sudden neurological decline in a preexisting SAVF or even cause one.1,2 Epidural steroid injections can induce neurological deterioration by reducing the capillary permeability, causing fluid retention, and reflux into intradural veins, leading to symptoms of spinal venous congestion. 2 Neurological deterioration can occur even with the low volumes recommended in clinical guidelines (2–5 mL), as observed in our case. 3 In this case, in retrospect, the MRI showed very subtle indirect signs of a fistula (abnormal flow voids) (Figure 1) that went unnoticed, leading to the preexisting fistula being misdiagnosed as a herniation.

Under normal circumstances, the epidural venous plexus and foraminal veins are interconnected with intradural spinal surface veins. However, in our case, the hyperflow from the SEAVF induced significant venous hypertension, leading to the formation of an engorged venous pouch with outflow retrogradely directed through an emissary vein to the ventral superficial medullary veins. The identification of the venous pouch played a crucial role in achieving an accurate diagnosis, indicating that the fistula was located in the lateral epidural space.4,5 This finding holds significant implications for the endovascular management of the condition. Reflow within the venous pouch can be tolerated, but complete occlusion should be avoided to preserve normal radicular venous outflow. Strong precautions must be taken to prevent embolization of the intradural veins. SEAVFs are less common than type I SAVFs, located at the dural entrance of the artery, mainly at the level of the dural sleeve of the nerve root. 4 However, differentiating between them can be challenging if the venous sac is not identified. 4 Treatment for both conditions involves disconnecting the fistula, with percutaneous embolization emerging as the primary option.5–7 A significant aspect of the embolization procedure for SEAVFs involves identifying and embolizing the fistulous points that usually drain into a venous sac, as observed in our case.8,9 While the majority of SAVF patients treated will observe improvement in motor function, fewer than half will experience enhanced sphincter function. 2 Remarkably, our case demonstrated complete recovery in sensory, motor, and sphincter functions, despite the severe spinal cord injury at presentation. This outcome is likely attributable to the early diagnosis and percutaneous embolization performed within the first 24 h of the spinal cord injury.

This case underscores the importance of increased awareness of epidural SEAVFs among healthcare providers and the need for early angiography in the diagnosis and treatment.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This paper is not based on a previous communication to a society or meeting.

Author contributions: All authors contributed equally to the manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. DGM, FBC, and XSN wrote the manuscript. MDL and CP designed and prepared the figures and their corresponding legends. ATW and SH reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the final version. All authors reviewed and approved the final version for submission.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Consent to participate/publish: This is a case report for which patient consent was obtained prior to manuscript writing and submission. The informed consent can be provided upon request. This study did not require an institutional review board evaluation.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Diego Gonzalez-Morgado https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1635-8774

References

- 1.Alhendawy I, Homapour B, Chandra RV, et al. Acute paraplegia in patient with spinal dural arteriovenous fistula after lumbar puncture and steroid administration: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2021; 81: 105797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrin Z, Marino RJ, Oleson CV, et al. Paralysis after lumbar interlaminar epidural steroid injection in the absence of hematoma: A case of congestive myelopathy due to spinal dural arteriovenous Fistula and a review of the literature. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020; 99: e107–e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Spine Intervention Society. In: Bogduk N. (ed) ISIS practice guidelines for spinal diagnostic and treatment procedures, 2nd ed. San Francisco: International Spine Intervention Society, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geibprasert S, Pereira V, Krings T, et al. Dural arteriovenous shunts: A new classification of craniospinal epidural venous anatomical bases and clinical correlations. Stroke 2008; 39: 2783–2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mull M, Othman A, Dafotakis M, et al. Spinal epidural arteriovenous fistula with perimedullary venous reflux: Clinical and neuroradiologic features of an underestimated vascular disorder. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2018; 39: 2095–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinn C, Masood K, Mehta T, et al. Trans-radial spinal angiography: A single-center experience. Interv Neuroradiol 2024; 30: 288–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu F, Bracard S, Trousset Y, et al. Virtual injection software for endovascular management of spinal dural arteriovenous fistula. Interv Neuroradiol 2023. Aug 1: 15910199231193469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathrani NV, Chauhan RS, Ramalingaiah AH, et al. Percutaneous embolization of spinal epidural arteriovenous fistulae: Report of 2 cases and technical considerations. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2023; 34: 498–500.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itsekzon-Hayosh Z, Hendriks EJ, O’Reilly ST, et al. Thoracolumbar spinal dural arteriovenous fistulae present with longer arteriovenous transit compared to cranial and cervical dural fistulae. Interv Neuroradiol 2023. Jan 5: 15910199221149096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]