Abstract

Background

The potentially higher risk of hemorrhagic complications is of concern in stent-assisted coiling (SAC) of ruptured wide-necked intracranial aneurysms (IAs). The Woven EndoBridge (WEB) is considered an appealing alternative since antiplatelet therapy is not required. Herein, we aimed to compare the safety and effectiveness of WEB vs. SAC for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked IAs.

Methods

This was an international cross-sectional study of consecutive patients treated for ruptured wide-neck IAs with WEB or SAC at four high-volume neurovascular centers between 2019 and 2022. Primary and secondary efficacy outcomes were radiographic aneurysm occlusion at follow-up and functional status at last follow-up. Safety outcomes included periprocedural hemorrhagic/ischemia-related complications.

Results

One hundred five patients treated with WEB and 112 patients treated with SAC were included. The median procedure duration of endovascular treatment was shorter for WEB than for SAC (69 vs. 76 min; p = 0.04). There were no significant differences in complete aneurysm occlusion rates (SAC: 64.5% vs. WEB: 60.9%; adjusted OR [aOR] = 0.70; 95%CI 0.34–1.43; p = 0.328). SAC had a significantly higher risk of complications (23.2% vs. 9.5%, p = 0.009), ischemic events (17% vs. 6.7%, p = 0.024), and EVD hemorrhage (16% vs. 0%, p = 0.008). The probability of procedure-related complications across procedure time was significantly lower with WEB compared with SAC (aOR = 0.40; 95%CI 0.20–1.13; p = 0.03).

Conclusion

WEB and SAC demonstrated similar obliteration rates at follow-up when used for embolization of ruptured wide-necked IAs. However, SAC showed higher rates of procedure-related complications primarily driven by ischemic events and higher rates of EVD hemorrhage. The overall treatment duration was shorter for WEB than for SAC.

Keywords: Intracranial aneurysm, Woven EndoBridge device, stent-assisted coiling, endovascular treatment

Introduction

Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to intracranial aneurysm (IA) rupture is a potentially devastating condition which leads to death in approximately one-third of patients and severe disability in another third. 1 The gold standard treatment for ruptured IAs has been endovascular coiling following the presentation of the results of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial.2,3 However, previously published studies have shown that primary coiling of wide-necked IAs has high rates of aneurysm recurrence. Hence, wide-necked IAs frequently require the performance of additional endovascular adjunctive treatments such as balloon assistance, stent-assisted coiling (SAC), or alternative options such as flow diversion, or intrasaccular flow disruption, to achieve complete aneurysm obliteration in follow-up.4–6

SAC is a commonly used technique for unruptured wide-necked IAs and has demonstrated higher complete occlusion rates and lower recurrence rates compared to primary coiling or balloon assisted-coiling.7–9 However, when intracranial stents are implanted, patients are required to start dual antiplatelet therapy 3 to 5 days before the procedure and continue this treatment indefinitely thereafter to prevent thromboembolic complications. 10 In the setting of ruptured wide-necked IAs, the decision to perform SAC requires an aggressive load of oral dual antiplatelet and/or intravenous antiplatelets, leading to additional concerns due to the potentially higher risk of hemorrhagic complications and aneurysm rebleeding.11,12

The WovenEndobridge device (WEB, MicroVention, CA, USA) is a barrel-like self-expandable intrasaccular device made of nitinol wires developed for the treatment of wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms. 13 After detachment of the device from the microcatheter, the WEB seals the aneurysm neck and leaves the parent artery unaffected. 14 Therefore, in contrast to SAC, long-term antiplatelet therapy is not mandatory, making WEB an attractive alternative especially in patients with ruptured wide-necked IAs. While some opacification of the aneurysm dome is commonly seen after immediate implantation, evidence from recent meta-analyses evaluating the performance of WEB for acutely ruptured IAs suggest high rates of aneurysm occlusion with little rebleeding.15,16

Recent studies have compared WEB vs. SAC in a heterogenous population of wide-necked IAs14,17; however, a comparative real-world analysis in a specific cohort of ruptured wide-necked IAs has yet to be published. Therefore, we sought to compare the safety and effectiveness of WEB vs. SAC for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked IAs.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

This was an international cross-sectional cohort study of consecutive patients treated for ruptured wide-neck IAs with WEB or SAC at four high-volume neurovascular centers from July 2015 to January 2022. The study was approved under the waiver of informed consent by each local institutional review board and is reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. 18

Wide-neck aneurysm was defined as a saccular IA with a neck size ≥4 mm or a dome-to-neck ratio <2. 19 Exclusion criteria were: (1) additional treatment with microsurgical clipping, flow diverter implantation or balloon-assisted coiling, (2) partially thrombosed aneurysms, and (3) fusiform or dissecting aneurysms.

Procedure

All the cases underwent treatment with general anesthesia. Femoral arterial access was obtained under ultrasound guidance. Routine diagnostic contrast images were obtained after a specific selection of the vessel of interest to evaluate the target aneurysm size and characteristics.

The selection of WEB or SAC treatment was made on a case-specific basis according to patient characteristics and local neurovascular interdisciplinary team preferences. WEB implantation was performed according to the technique described elsewhere. 20 The WEB SL (Microvention) and SLS (Microvention) were both employed. Aspirin therapy was prescribed and maintained for up to 6 weeks only if there was concern of WEB herniation.

All patients treated with SAC received a maintenance dose (0.1 mcg/kg/min) of intraoperative intravenous tirofiban, a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, for 4 h, followed by a loading dose of aspirin (325 mg) and clopidogrel (300 mg). Heparinization was routinely performed immediately after successful deployment of the first coil. Specific technical details were similar to previous descriptions, with expected subtle differences between operators. 21 The following stents were employed (selection was determined on a case-specific basis according to the physician's preference considering anatomical and clinical characteristics): Enterprise stent (Codman & Shurtleff, MA, USA), LVIS Jr. (Microvention), and NeuroForm Atlas stent (Stryker, MI, USA).

EVD placement was done according to the local practice at each center, and placement was performed before any IA treatment according to previously described standard techniques. 22

Clinical and radiological outcomes

Baseline patient characteristics include demographics, comorbidities, and clinical presentation (Hunt and Hess grade, Glasgow coma scale, modified Fisher score). Aneurysm characteristics were evaluated before treatment from digital subtraction angiography images and included location, dimensions, and morphology.

All effectiveness and safety outcomes were independently adjudicated by the PI at each center. The primary effectiveness outcome was complete aneurysm occlusion evaluated by the Raymond-Roy (RR) occlusion classification at the final imaging follow-up (either digital subtraction angiography, computed tomography angiography, or magnetic resonance angiography). The RR classification grades angiographic occlusions as class I (complete obliteration), class II (residual neck), and class III (residual aneurysm). 23

Secondary outcomes were categorized as safety and efficacy outcomes. For efficacy, favorable functional outcome and retreatment were evaluated. Favorable functional outcome was defined as a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score 0–2 at final clinical follow-up. The mRS is a categorical scale (0, no symptoms; 6, death) that reflects the degree of disability after a stroke. A score of 0 to 2 reflects independence for activities of daily living. 24

For safety, procedure-related complications included ischemic and hemorrhagic events encountered during the procedure and/or hospitalization. Ischemic complications were defined as neurological deficits resulting in an increase ≥4 points in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale with or without evidence of ischemia on non-contrast computed tomography or magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging. Hemorrhagic complications were defined as any type of bleeding event related to the procedure. In addition, rates of external ventricular drainage (EVD) hemorrhage, in-hospital mortality, all-cause mortality, and rebleeding were also recorded. Symptomatic EVD hemorrhage was defined by a decline in Glasgow coma scale score ≥2 points from baseline and new-onset hemorrhage on neuroimaging and when other possible causes of neurological deterioration were ruled out.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize continuous and categorical variables. We reported counts and percentages for categorical variables and means (standard deviation [SD]) or medians (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables. Shapiro-Wilk test and histograms were used to assess the normality of distributions. For the univariable analysis, we used the student's t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, as needed.

To evaluate the efficacy outcomes between WEB and SAC groups, we performed multivariable logistic regression and a proportional odds regression model (shift analysis). Final models were selected by bidirectional stepwise selection procedures with Akaike's information criteria or Bayesian information criteria. “Center” was used as random effect. Candidate variables considered to feed the stepwise procedures were selected based in clinical relevance 25 and statistical significance in univariable analyses: age, gender, diabetes mellitus, prior antiplatelets, Hunt and Hess grade, EVD, aneurysm location, neck size, aneurysm size, procedure duration, and use of intraprocedural antiplatelets. The logistic regression model analysis was employed for complete occlusion at last follow-up (RR 1 versus RR 2–3) and favorable functional outcome (mRS 0–2 versus mRS 3–6). The ordinal regression statistical values for RR classification were obtained by the proportional odds model. Missing values in the candidate covariates were imputed using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations. Results were pooled together using Rubin's rules. 26 The odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect size of each group were computed. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis, stratified by clinical severity at admission (Hunt and Hess grade), was performed for favorable functional outcome and procedure-related complications.

We further explored the relation between time and procedure complications using both techniques. To generate the time predicted probability curves of procedure-related complications, we used a logistic regression model that adjusted for procedure type, EVD, and procedure duration. There are four combinations of procedure type and EVD (WEB with EVD = 0, WEB with EVD = 1, SAC with EVD = 0, SAC with EVD = 1). For each of the combinations, predicted probabilities were computed over a sequence of procedure duration values. These probabilities were then averaged over the presence or absence of EVD, providing predicted probabilities over a range of procedure duration for both treatments, adjusted for EVD. The curves indicate the predicted probabilities, and the shaded areas are the 95% CIs. All the statistical analyses were considered significant at a two-sided alpha level of ≤0.05. We used the R statistical package (version 4.1.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for the analysis.

Results

A total of 217 patients harboring ruptured wide-necked IAs were included; of these, 105 were treated with WEB and 112 underwent SAC. The demographic data and treatment characteristics of the two groups are presented in Table 1. The group of patients treated with WEB had a lower proportion of females (58.1% vs. 71.4%, p = 0.040), a higher rate of diabetes (19.6% vs. 9.8%, p = 0.045), and a lower rate of prior antiplatelet therapy (8.6%, vs. 21.5%, p = 0.009) than those treated with SAC. Furthermore, patients treated with WEB had a larger median aneurysm size (6.3 vs. 4.6, p < 0.001), larger median neck size (4 vs. 3.3, p = 0.009), lower rate of EVD implantation (34.3% vs. 67.9%, p < 0.001), shorter median procedure time (69 vs. 76, p = 0.004), and lower rate of intraprocedural antiplatelet use (16.2% vs. 82.1%, p < 0.001). The WEB single layer and single layer spheric was implanted in 78.1% and 21.9% of the cases, respectively. Adjunctive coils were used in 11% of patients, all of whom were WEB cases. Most of the patients (97.3%) treated with SAC received one stent, while only three patients received two. Enterprise was the most implanted stent (62.5%), followed by NeuroForm Atlas (21.4%), and LVIS Jr (16.1%).

Table 1.

Baseline and treatment characteristics.

| Total (N = 217) | SAC (N = 112) | WEB (N = 105) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median [IQR] | 56 [48–65] | 56 [48–69] | 56 [48–64] | 0.480 |

| Females, No (%) | 141 (65) | 80 (71.4) | 61 (58.1) | 0.040 |

| Medical history, No (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 113 (54.1) | 58 (51.8) | 55 (56.7) | 0.477 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 53 (25.4) | 25 (22.3) | 28 (28.9) | 0.278 |

| Diabetes | 30 (14.4) | 11 (9.8) | 19 (19.6) | 0.045 |

| Current smoker | 138 (63.6) | 69 (61.6) | 69 (65.7) | 0.530 |

| Prior antiplatelets, No (%) | 32 (15.1) | 23 (21.5) | 9 (8.6) | 0.009 |

| Prior anticoagulants, No (%) | 6 (2.9) | 3 (2.9) | 3 (2.9) | 0.981 |

| Prior aneurysm treatment, No (%) | 10 (4.6) | 5 (4.5) | 5 (4.8) | 0.917 |

| Hunt and Hess grade, No (%) | 0.101 | |||

| 1–3 | 174 (80.2) | 85 (75.9) | 89 (84.8) | |

| 4–5 | 43 (19.8) | 27 (24.1) | 16 (15.2) | |

| Modified Fisher scale, No (%) | 0.785 | |||

| 1–2 | 108 (50) | 55 (49.1) | 53 (51) | |

| 3–4 | 108 (50) | 57 (50.9) | 51 (49) | |

| Baseline mRS, No (%) | 0.867 | |||

| 0–2 | 202 (97.1) | 108 (97.3) | 94 (96.9) | |

| 3–5 | 6 (2.9) | 3 (2.7) | 3 (3.1) | |

| Specific aneurysm location, No (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Anterior communicating artery | 73 (33.6) | 35 (31.2) | 38 (36.2) | |

| Internal carotid artery | 45 (20.7) | 38 (33.9) | 7 (6.7) | |

| Middle cerebral artery | 40 (18.4) | 10 (8.9) | 30 (28.6) | |

| Basilar artery | 11 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 11 (10.5) | |

| Posterior communicating artery | 9 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 9 (8.6) | |

| Other | 39 (18) | 29 (25.9) | 10 (9.5) | |

| Aneurysm size (mm), median [IQR] | 5.3 [4–7.5] | 4.6 [3.2–6.2] | 6.3 [5–8] | <0.001 |

| Neck size (mm), median [IQR] | 3.5 [2.9–4.6] | 3.3 [2.5–4.3] | 4 [3–5] | 0.009 |

| Dome-to-neck ratio, median [IQR] | 1.5 [1.19–1.7] | 1.5 [1.2–1.7] | 1.5 [1.3–1.7] | 0.180 |

| External ventricular drainage, No (%) | 112 (51.6) | 76 (67.9) | 36 (34.3) | <0.001 |

| Type of stent implanted, No (%) a | – | |||

| Enterprise | 70 (62.5) | 70 (62.5) | – | |

| NeuroForm Atlas | 24 (21.4) | 24 (21.4) | – | |

| LVIS Jr | 18 (16.1) | 18 (16.1) | – | |

| Procedure duration (min) | 0.004 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 86.8 ± 54 | 96.7 ± 57.7 | 75.2 ± 46.6 | |

| Median [IQR] | 70.5 [48–111] | 76 [56–120] | 69 [35–100] | |

| Intraprocedural antiplatelets, No (%) | 109 (50.2) | 92 (82.1) | 17 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Imaging follow-up time (months) | 0.007 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 25.8 ± 29.9 | 35.5 ± 37.3 | 17.3 ± 17.5 | |

| Median [IQR] | 11 [6–39.5] | 14.7 [6.2–65.8] | 10 [5.3–23] | |

SAC: Stent-assisted coiling; WEB: Woven EndoBridge; IQR: Interquartile range; SD: Standard deviation; mRS: Modified Rankin scale.

1 case received 2 Enterprise stents, another 2 NeuroForm stents, and another 2 LVIS Jr stents.

Primary outcome

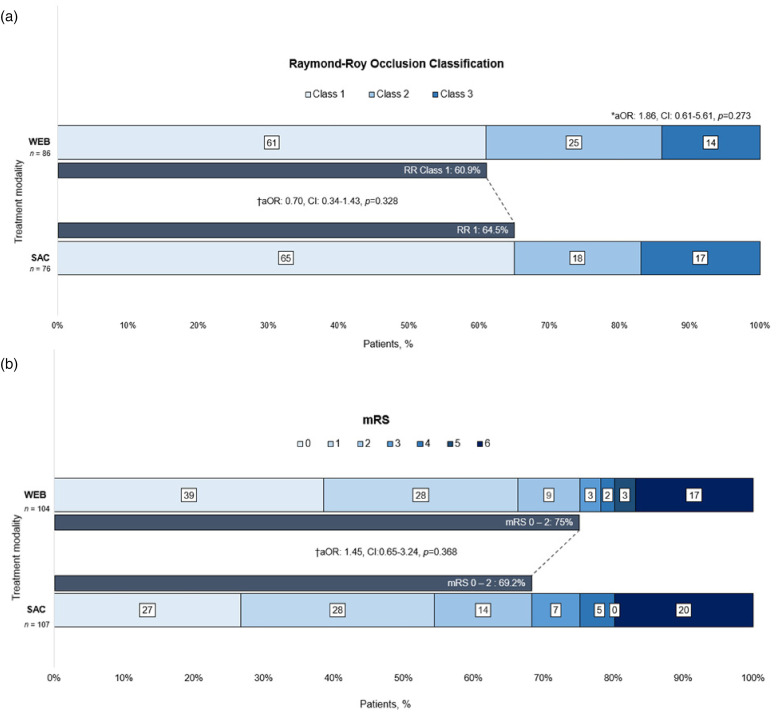

The median length of imaging follow-up was 10 months (IQR 5.3–23 months) in the WEB group and 14.7 months (IQR 6.2–65.8 months) in the SAC group (p = 0.007). Compared with WEB, patients in the SAC group had a slightly higher rate of complete occlusion, but this difference was not significant (64.5% vs. 60.9%, p = 0.640). After adjusting for the selected covariates, the difference in the odds of complete occlusion between the two groups remained non-significant (adjusted OR [aOR] = 0.70; 95% CI 0.34–1.43; p = 0.328). Similarly, after adjusting for the same confounders, the ordinal RR classification did not differ between the two groups (aOR = 1.86; 95% CI 0.61–5.61; p = 0.273) (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

(a) Shift analysis of Raymond-Roy occlusion classification and (b) favorable functional outcome (modified Rankin scale 0–2) at last follow-up. aOR: adjusted odds ratio; WEB: Woven Endobridge device; BAC, balloon-assisted coiling; mRS, modified Rankin scale; SAC, stent-assisted coiling. *Proportional odds model. Adjusted for: age, Hunt and Hess grade, prior antiplatelets, location, and neck size. †Dichotomized RR class 1 vs. 2–3 and mRS score 0–2 vs. 3–6 (performed over multiple imputations). Adjusted for: age, Hunt and Hess grade, prior antiplatelets, location, and neck size.

Secondary outcomes

There were no significant differences in the rate of favorable functional outcome between the WEB and SAC groups, respectively (75% vs 69.2%, p = 0.345). After adjusting for covariates, no association was observed for a favorable functional outcome with either technique (aOR = 1.45; 95% CI 0.65–3.24; p = 0.368) (Figure 1(b)). The results of the sensitivity analysis for favorable functional outcome, stratified by clinical severity, align with the findings of the primary analysis (Supplementary Table 1).

Secondary outcomes are presented in Table 2. There was a statistically significant higher rate of procedure-related complications in the SAC group compared with the WEB group (23.2% vs. 9.5%, p = 0.009). Nevertheless, among patients with Hunt and Hess grade 4–5 at admission, this difference was not statistically significant (SAC: 29.6% vs. WEB: 25%, p = 0.744) [Supplementary Table 1]. Furthermore, patients undergoing SAC had a significantly higher rate of ischemic events (17% vs. 6.7%, p = 0.024). Similarly, the rate of hemorrhagic events was higher with SAC, although not significant (8% vs. 3.8%, p = 0.201). Within the SAC group, the rates of ischemic events were 8.3%, 14.3%, and 16.7% (p = 0.689) with NeuroForm Atlas, Enterprise, and LVIS Jr, respectively. There were no significant differences in in-hospital mortality, all-cause mortality, retreatment, and rebleeding rates between both groups. With respect to EVD hemorrhage, the rate was higher in the SAC group (all cases were asymptomatic) compared with the WEB group (16% vs. 0%, p = 0.008).

Table 2.

Secondary outcomes.

| Total (N = 217) | SAC (N = 112) | WEB (N = 105) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure-related complications, No (%) | 36 (16.6) | 26 (23.2) | 10 (9.5) | 0.009 |

| Ischemic events, No (%) | 26 (12) | 19 (17) | 7 (6.7) | 0.024 |

| Hemorrhagic events, No (%) | 13 (6) | 9 (8) | 4 (3.8) | 0.201 |

| In-hospital mortality, No (%) | 31 (14.4) | 20 (18) | 11 (10.5) | 0.119 |

| All-cause mortality, No (%) | 39 (18.5) | 21 (19.8) | 18 (17.1) | 0.618 |

| EVD hemorrhage a , No (%) | 12/111 (10.8) | 12/75 (16) b | 0/36 (0) | 0.008 |

| Retreatment, No (%) | 29/178 (16.3) | 13/84 (15.5) | 16/94 (17) | 0.064 |

| Rebleeding a , No (%) | 1/178 (0.6) | 0/84 (0) | 1/94 (1.1) | 0.343 |

SAC: Stent-assisted coiling; WEB: Woven Endobridge; EVD: External ventricular drainage.

Center was not used as a random effect.

None of the cases were symptomatic.

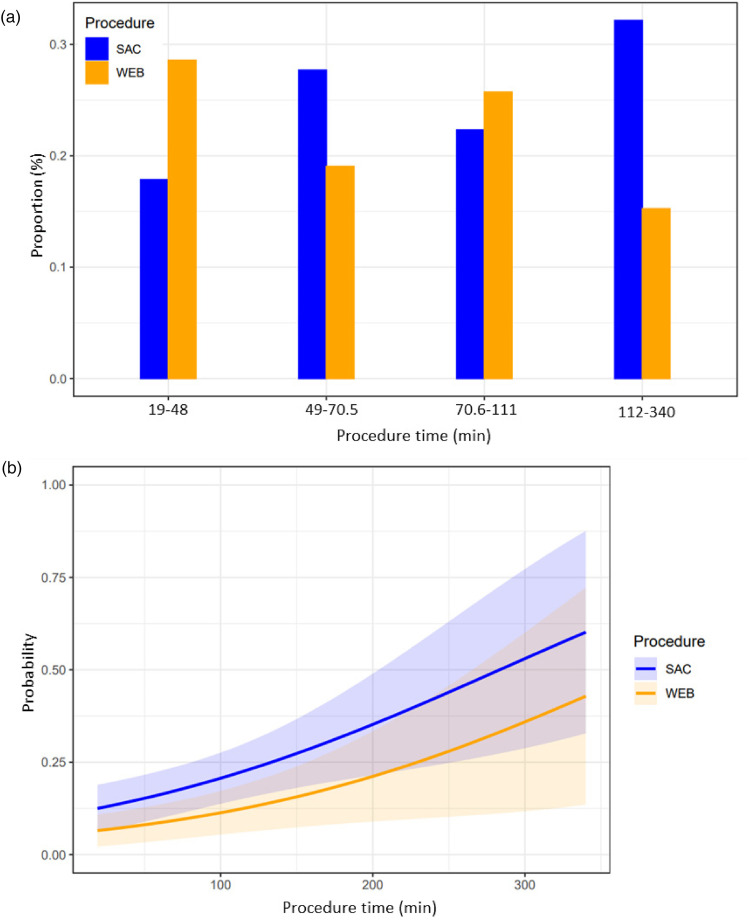

Relation of procedure time with procedure-related complications

When the procedure time was categorized by quartiles, a large proportion of the SAC procedures (33%) lasted more than 112 min, while a significant proportion of WEB procedure (29%) lasted less than 48 min (Figure 2(a)). The differences in the probability of procedure-related complications associated with procedure time are shown in Figure 2(b). We observed a linear relationship between the probability of a procedure-related complication and procedure time and, after adjusting for EVD implantation, the probability across procedure time was lower with WEB when compared with SAC (aOR = 0.40; 95% CI 0.20–1.13; p = 0.03).

Figure 2.

(a) Illustration of the distribution of patients over procedure time (by quartiles) within each treatment technique. (b) Adjusted predicted probability of the association between the procedure time and procedure-related complications. The adjusted predicted probabilities of having procedure-related complications over a sequence of procedure time, grouped by two procedure types. The curves represent the predicted probabilities of the outcome, using two procedure types while adjusted for external ventricular drainage. The shaded areas represent the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. SAC: Stent-assisted coiling; WEB: Woven EndoBridge.

Discussion

In this study, the treatment of ruptured wide-necked IAs with WEB or SAC showed comparable rates of aneurysm occlusion and clinical outcomes. However, SAC showed a higher rate of procedure-related complications primarily driven by ischemic events and a higher rate of EVD hemorrhage. Our findings show that longer procedure times increase the probability of procedure-related complications. Moreover, when WEB was used, the overall duration of embolization was reduced.

Previous studies comparing outcomes between WEB and SAC demonstrated similar short-term (6 months of follow-up) complete aneurysm occlusion rates.14,17 However, in the study by El Naamani et al. only 21% (31/148) of the IAs were ruptured and the proportion of wide-necked IAs was not specified. 17 Likewise, in the study by Kabbasch et al. a low rate (36%, 48/132) of the IAs were ruptured, with the authors reporting 89% (118/132) of wide-necked lesions. 14 In comparison, although in our study the occlusion rate between WEB and SAC was comparable, our cohort included only ruptured wide-necked IAs and the follow-up time available was longer (26 months). Notably, we found slightly higher complete occlusion rates compared to previous studies reporting outcomes of ruptured aneurysms treated with WEB15,16,27 or SAC1.2 Based on previous studies that have shown that longer follow-up times may improve aneurysm occlusion, we suggest that the longer follow-ups in both groups of our cohort might explain the higher occlusion rates we found.28–30

In recent meta-analyses including ruptured IAs, favorable functional outcome (final follow-up 0–2 mRS) rates ranged from 62% to 87% with WEB15,16,31,32 and 67%–86% with SAC,11,12,30 which is in line with our findings. In our specific population of ruptured wide-necked IAs, the favorable functional outcomes were not different between the WEB and SAC groups. Likewise, Kabbasch et al. 14 and El Naamani et al. 17 reported no differences in clinical outcome between the two techniques. Therefore, our findings suggest that WEB and SAC can achieve similar and favorable clinical outcomes in the context of ruptured wide-necked IAs.

A particular concern in the setting of ruptured IAs treated with SAC is the risk of EVD tract hemorrhage, given the need for ongoing antiplatelet therapy.11,12,33 In the current study, EVD hemorrhage was significantly higher in the SAC than in the WEB group (16% vs. 0%). Of note, we observed heterogeneity in regards of the EVD institutional protocol and differences in the frequency of EVD use between the institutions participating in the study. Therefore, our findings could be influenced by the different institutional practices commonly observed in real-world multicentric studies.

SAC requires a strict antiplatelet regimen to avoid ischemic complications and unintended occlusion of side branches covered by the stent.34,35 Previous studies have reported higher rates of ischemic events after SAC when compared to coiling alone, mainly due to a lack of consensus on postoperative antiplatelet regimens, medication compliance, and biologic resistance to antiplatelet drug effects.36–40 In addition, previous reports have shown that the use of antiplatelet therapy after SAC in the context of acutely ruptured IAs increases the risk of hemorrhagic complications.11,12 On the other hand, the WEB device does not require strict antiplatelet therapy if it is successfully deployed inside the aneurysm sac. This is relevant in the acute phase of ruptured IAs when patients require invasive therapies such as EVD or lumbar drains and, in some cases, ventriculoperitoneal shunts, all of which can potentially present hemorrhagic complications specially in the setting of antiplatelet therapy. 31 In the study by Kabbasch et al., SAC was associated with higher risk of procedure-related (symptomatic and asymptomatic complications) and neurological complications (transient or permanent neurological deficits after the procedure) in comparison with WEB for unruptured and ruptured IAs (89% wide-necked). 14 El Naamani et al. reported a higher rate of minor complications (asymptomatic stroke or brain hemorrhage, asymptomatic coil herniation, stent malposition, in-sent thrombus, and access-site complication) in the SAC cohort than in the WEB cohort for unruptured and ruptured IAs; however, the rates were comparable between both techniques after inverse probability weighted adjustment. 17 In our study, although we did not control for confounding variables, we observed significantly higher rates of procedure-related complications and ischemic events in the SAC cohort. Our findings suggest that SAC has higher rates of procedure-related complications primarily driven by ischemic events in comparison with WEB for ruptured wide-necked IAs, which is in line with the current evidence.

The implantation of a single versus multiple devices has demonstrated to shorten treatment times and radiation exposure.41,42 Similarly, our results show that treatment with WEB was significantly shorter than with SAC (median 69 min vs. 76 min). Additionally, the WEB group had significantly larger aneurysms (median 6.3 mm vs. 4.6 mm). Although we did not report radiation times, shorter procedure times reduce radiation exposure. This has also been demonstrated when comparing SAC with flow diversion. 42 Besides these benefits, our findings show that longer procedure times increase the probability of procedure-related complications. This finding is not surprising but should be interpreted with caution as it does not imply that the device itself is safer but that taken together the technique that involves implanting less devices in a shorter time seems to be safer. Nevertheless, treatment selection should be based on the angiographical and clinical characteristics of the patient, favoring the best clinical outcomes.

The limitations of this study are mainly related to its non-randomized retrospective design and its relatively small sample size. Follow-up aneurysm occlusion was not corroborated by an independent core laboratory. The relatively short follow-up period in our study limits our ability to assess occlusion rates in the long term and retreatment rate. In addition, the institutional protocols for ruptured IAs were not standardized between centers. As a consequence, the majority of EVD placements (86%) belonged to one of the centers. Therefore, the effects of a selection bias cannot be ignored in our findings. In addition, because of the low rate of events in the secondary outcomes we could not adjust for confounding variables that could have influenced our findings. Data related to the devices used in the interventional procedure were not available and, therefore, we were not able to explore their potential effects on the procedure or outcomes. Furthermore, the current study did not include the newer generations of the WEB device.

Conclusion

The results of the current study indicate that SAC and WEB embolization of ruptured wide-necked IAs have a similar efficacy profile. However, our findings suggest a higher rate of procedure-related complications primarily driven by ischemic events and a higher rate of EVD hemorrhage in patients treated with SAC. On the other hand, WEB seems to have a better safety profile mainly determined by the avoidance of antiplatelet therapy after implantation and a shorter procedure time. Pending further prospective comparative studies, WEB might be a viable alternative for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked IAs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ine-10.1177_15910199231223538 for Woven EndoBridge versus stent-assisted coil embolization for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked aneurysms: A multicentric experience by Aaron Rodriguez-Calienes, Juan Vivanco-Suarez, Yujing Lu, Milagros Galecio-Castillo, Bradley Gross, Mudassir Farooqui, Oktay Algin, Chaim Feigen, David J Altschul and Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez in Interventional Neuroradiology

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Ortega-Gutierrez–Grants: NIH-NINDS (R01NS127114-01), Stryker, Medtronic, Microvention, Methinks, IschemiaView, Viz.ai, Siemens. Consulting fees: Medtronic, Stryker Neurovascular.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Aaron Rodriguez-Calienes https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8413-6954

Juan Vivanco-Suarez https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5326-1907

Oktay Algin https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3877-8366

David J Altschul https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5130-1378

Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3408-1297

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 2007; 369: 306–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molyneux AJ, Birks J, Clarke A, et al. The durability of endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: 18 year follow-up of the UK cohort of the international subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT). Lancet 2015; 385: 691–697. 20141028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salem MM, Maragkos GA, Gomez-Paz S, et al. Trends of ruptured and unruptured aneurysms treatment in the United States in post-ISAT era: a national inpatient sample analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10: e016998. 20210209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naggara ON, Lecler A, Oppenheim C, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial unruptured aneurysms: a systematic review of the literature on safety with emphasis on subgroup analyses. Radiology 2012; 263: 828–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naggara ON, White PM, Guilbert F, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial unruptured aneurysms: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature on safety and efficacy. Radiology 2010; 256: 887–897. 20100715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierot L, Spelle L, Cognard C, et al. Wide neck bifurcation aneurysms: what is the optimal endovascular treatment? J Neurointerv Surg 2021; 13: e9–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H, Sun Y, Jiang Y, et al. Comparison of stent-assisted coiling vs coiling alone in 563 intracranial aneurysms: safety and efficacy at a high-volume center. Neurosurgery 2015; 77: 241–247. discussion 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang F, Chen X, Wang Y, et al. Stent-assisted coiling and balloon-assisted coiling in the management of intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review & meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci 2016; 364: 160–166. 20160325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong Y, Wang YJ, Deng Z, et al. Stent-assisted coiling versus coiling in treatment of intracranial aneurysm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014; 9: e82311. 20140115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youssef PP, Dornbos IIID, Peterson J, et al. Woven EndoBridge (WEB) device in the treatment of ruptured aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg 2021; 13: 443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodily KD, Cloft HJ, Lanzino G, et al. Stent-assisted coiling in acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a qualitative, systematic review of the literature. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 1232–1236. 20110505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bsat S, Bsat A, Tamim H, et al. Safety of stent-assisted coiling for the treatment of wide-necked ruptured aneurysm: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Interv Neuroradiol 2020; 26: 547–556. 20200802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding YH, Lewis DA, Kadirvel R, et al. The Woven EndoBridge: a new aneurysm occlusion device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 607–611. 20110217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabbasch C, Goertz L, Siebert E, et al. WEB Embolization versus stent-assisted coiling: comparison of complication rates and angiographic outcomes. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 812–816. 20190123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monteiro A, Lazar AL, Waqas M, et al. Treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms with the Woven EndoBridge device: a systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg 2022; 14: 366–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie Y, Tian H, Xiang B, et al. Woven EndoBridge device for the treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review of clinical and angiographic results. Interv Neuroradiol 2022; 28: 240–249. 20210623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naamani KE, Chen CJ, Abbas R, et al. Woven EndoBridge versus stent-assisted coil embolization of cerebral bifurcation aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2022; 137: 1786–1793. 20220429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao B, Yin R, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular coiling of wide-neck and wide-neck bifurcation aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 1700–1705. 20160602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Algin O, Corabay S, Ayberk G. Long-term efficacy and safety of WovenEndoBridge (WEB)-assisted cerebral aneurysm embolization. Interv Neuroradiol 2022; 28: 695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vivanco-Suarez J, Wallace AN, Dandapat S, et al. Stent-assisted coiling versus balloon-assisted coiling for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked aneurysms: a 2-center experience. Stroke: Vascular and Interventional Neurology 2023; 3: e000456. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limaye K, Zanaty M, Hudson J, et al. The safety and efficacy of continuous tirofiban as a monoantiplatelet therapy in the management of ruptured aneurysms treated using stent-assisted coiling or flow diversion and requiring ventricular drainage. Neurosurgery 2019; 85: E1037–e1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascitelli JR, Moyle H, Oermann EK, et al. An update to the Raymond-Roy occlusion classification of intracranial aneurysms treated with coil embolization. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 496–502. 20140604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, et al. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988; 19: 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalouhi N, Jabbour P, Singhal S, et al. Stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2013; 44: 1348–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51: 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spelle L, Herbreteau D, Caroff J, et al. CLinical assessment of WEB device in ruptured aneurYSms (CLARYS): results of 1-month and 1-year assessment of rebleeding protection and clinical safety in a multicenter study. J Neurointerv Surg 2022; 14: 807–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierot L, Moret J, Barreau X, et al. Aneurysm treatment with Woven EndoBridge in the cumulative population of 3 prospective, multicenter series: 2-year follow-up. Neurosurgery 2020; 87: 357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierot L, Szikora I, Barreau X, et al. Aneurysm treatment with the Woven EndoBridge (WEB) device in the combined population of two prospective, multicenter series: 5-year follow-up. J Neurointerv Surg 2022: neurintsurg-2021-018414. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-018414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Zuo Q, Tang H, et al. Stent assisted coiling versus non-stent assisted coiling for the management of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Neurointerv Surg 2019; 11: 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Essibayi MA, Lanzino G, Brinjikji W. Safety and efficacy of the Woven EndoBridge device for treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2021; 42: 1627–1632. 20210611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hudson JS, Prout BS, Nagahama Y, et al. External ventricular drain and hemorrhage in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients on dual antiplatelet therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Neurosurgery 2019; 84: 479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai K, Zhang Y, Shen L, et al. Comparison of stent-assisted coiling and balloon-assisted coiling in the treatment of ruptured wide-necked intracranial aneurysms in the acute period. World Neurosurg 2016; 96: 316–321. 20160916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhogal P, Ganslandt O, Bäzner H, et al. The fate of side branches covered by flow diverters-results from 140 patients. World Neurosurg 2017; 103: 789–798. 20170421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo R, Bradac GB, Castellan L, et al. Neuroform Atlas stent-assisted coiling of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a multicenter study. J Neuroradiol 2021; 48: 479–485. 20200320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hetts SW, Turk A, English JD, et al. Stent-assisted coiling versus coiling alone in unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the matrix and platinum science trial: safety, efficacy, and mid-term outcomes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 698–705. 20131101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaughlin N, McArthur DL, Martin NA. Use of stent-assisted coil embolization for the treatment of wide-necked aneurysms: a systematic review. Surg Neurol Int 2013; 4: 43. 20130330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SR, Vora N, Jovin TG, et al. Anatomic results and complications of stent-assisted coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol 2008; 14: 267–284. 20081008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King B, Vaziri S, Singla A, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcomes after stent-assisted coiling of cerebral aneurysms with enterprise and neuroform stents: a comparative analysis of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 905–909. 20141028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishido H, Piotin M, Bartolini B, et al. Analysis of complications and recurrences of aneurysm coiling with special emphasis on the stent-assisted technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 339–344. 20130801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rai AT, Turner RC, Brotman RG, et al. Comparison of operating room variables, radiation exposure and implant costs for WEB versus stent assisted coiling for treatment of wide neck bifurcation aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol 2021; 27: 465–472. 20201020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colby GP, Lin LM, Nundkumar N, et al. Radiation dose analysis of large and giant internal carotid artery aneurysm treatment with the pipeline embolization device versus traditional coiling techniques. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 380–384. 20140408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-ine-10.1177_15910199231223538 for Woven EndoBridge versus stent-assisted coil embolization for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked aneurysms: A multicentric experience by Aaron Rodriguez-Calienes, Juan Vivanco-Suarez, Yujing Lu, Milagros Galecio-Castillo, Bradley Gross, Mudassir Farooqui, Oktay Algin, Chaim Feigen, David J Altschul and Santiago Ortega-Gutierrez in Interventional Neuroradiology