Abstract

Background/Aims

The etiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is associated with intestinal mucosal barrier damage. However, changes in the tight junction (TJ) proteins in IBS have not been fully elucidated. This study aimed to evaluate TJ protein changes in IBS patients and the relationship between aging and disease severity.

Methods

Thirty-six patients with IBS fulfilling the Rome IV criteria and twenty-four controls were included. To evaluate the change of TJ in the colonic mucosa, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, western blot, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were performed, respectively.

Results

The entire IBS group (n = 36) exhibited decreased levels of claudin-1 and -2 mRNA compared to the control group (n = 24), with statistical significance (p < 0.05). Additionally, in western blot analyses, both claudin-1 and ZO-1 levels were significantly reduced in the IBS group compared to the control group (n = 24) (p < 0.05). IHC analysis further revealed that ZO-1 expression was significantly lower in the IBS group than in the control group (p < 0.001). This trend of reduced ZO-1 expression was also observed in the moderate-to-severe IBS subgroup (p < 0.001). Significantly, ZO-1 expression was notably lower in both the young- (p = 0.036) and old-aged (p = 0.039) IBS groups compared to their respective age-matched control groups. Subtype analysis indicated a more pronounced decrease in ZO-1 expression with advancing age.

Conclusions

ZO-1 expression was especially decreased in the aged IBS group. These results suggest that ZO-1 might be the prominent TJ protein causing IBS in the aging population.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Tight junction, Aging, Colon

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. This reduces the quality of life and places a significant economic burden on the medical system and society [1-4]. The pathophysiology of IBS is multifactorial, involving alterations in visceral hypersensitivity, GI motility, mucosa-associated immune alterations, microbiome, and intestinal permeability [5]. Recent studies have shown the role of intestinal barrier dysfunction in IBS. Several previous studies have suggested that intestinal permeability is increased in patients with IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D) or in those with post-infection IBS [6].

The intestinal epithelium forms a crucial barrier that regulates the selective passage of nutrients and prevents the infiltration of harmful pathogens and toxins into the underlying tissues [7]. Tight junction (TJ) proteins, which serve as molecular gatekeepers that control paracellular permeability, are central to the integrity of this barrier. TJs consist of various proteins, including claudins, occludins, and zonula occludens, all of which play pivotal roles in maintaining the structural and functional integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier [8-10].

Alterations in TJ proteins may be a key factor that contributes to the disrupted gut barrier observed in patients with IBS. The dysregulation of these proteins can lead to increased intestinal permeability, thereby allowing luminal antigens to translocate into the underlying mucosa. This, in turn, can trigger immune responses, low-grade inflammation, and an array of GI symptoms characteristic of IBS [11,12].

Among the proteins composing TJs, the following three proteins have been mainly studied: the transmembrane proteins, occludin and claudin-1, and the cytosolic protein, zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) [8,13-15]. However, in patients with IBS, the role of TJ proteins has been poorly investigated. Previous studies have recently shown an increase in the colonic paracellular permeability in patients with IBS associated with a decrease in ZO-1 mRNA level [16]. Other studies have reported that occludin mRNA expression remained not modified [17]. However, a recent study has reported a decrease in the occludin expression in the colonic mucosa of patients with IBS [18].

While several studies have investigated the association between TJ protein levels and IBS, the exact nature of these changes, their mechanisms, and their clinical implications remain a subject of ongoing research and debate. Although studies have identified changes in TJ proteins in patients with IBS, the relationship between these changes and the aging process has not been well elucidated.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate the changes in TJ proteins associated with aging and disease severity in patients with IBS, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms in IBS.

METHODS

Participants

This study was conducted prospectively at a tertiary care center from 2018 to 2022. All participants were recruited from Korea, with the control group comprising individuals who underwent colonoscopies as part of a health checkup. Under the guidance of a well-trained interviewer, participants received colonoscopies and completed questionnaires regarding IBS symptoms. We excluded patients with any macroscopic or histologic abnormalities of the colonic mucosa, a history of GI surgery, neuromuscular diseases, GI malignancies, or any other organic bowel diseases. Participants were categorized into control or IBS groups, with only IBS-D patients enrolled according to the Rome IV criteria, as shown in previous studies [19,20]. IBS-D is commonly known to be more prevalent, and it was expected that the expression of TJ proteins would be more closely associated with IBS-D. The control group consisted of individuals with normal colonic mucosa and no evidence of organic or functional bowel disease.

Colonoscopy biopsy

All participants underwent a comprehensive colonoscopy, during which biopsies were taken from the sigmoid colon. Using standard biopsy forceps, we collected six tissue samples of the colon mucosa. These samples were then analyzed using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), western blotting, and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Specifically, two colon mucosal biopsy samples were allocated for each analysis method: qRT-PCR, western blot analysis, and IHC.

Questionnaire

Thirty-six patients with IBS fulfilling the Rome IV criteria and twenty-four controls were included in this study. IBS symptom severity was assessed using the IBS Severity Scoring System [19]. The overall IBS score ranged from 0 to 500, and patients were divided into 3 groups according to score, as follows: mild IBS, < 175; moderate IBS, 175–300; and severe IBS, > 300 (Supplementary Fig. 1) [21]. The IBS and control groups were classified according to age. Further, both groups were categorized into the old- and young-aged groups. To clarify differences between ages, participants aged 65 years or older were categorized into the old-aged group, whereas those aged 20–59 years were categorized into the young-aged group.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from human sigmoid colon tissues using QIAzol reagent (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands), according to the manufaturer’s instructions. Using 2 μg of the total RNA as a template, the first strand cDNA was synthesized using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The ABI ViiA7 Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) amplification and detection. qPCR was run in triplicates, each of 10-μg reaction volume using Power SYBR® Green PCR Master mix (ABI), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Thermal cycling was performed under the following conditions: 50°C, 2 minutes; 95°C, 10 minute; 40 cycles of 95°C, 15 seconds; and 60°C, 1 minute. Used primers are described in Supplementary Table 1. All expression levels were normalized to GAPDH levels of the same sample. The relative quantity of target gene expression to housekeeping genes was measured using the comparative Ct method (Supplementary Table 1).

Western blot analysis

Based on the qRT-PCR results, we selected TJ proteins for western blot analysis. Claudin-1, -2, occludin, and ZO-1 were selected for analysis as they are likely to be related to disease severity and age based on PCR analysis. Total protein was extracted from sigmoid colon tissues using RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and PMSF (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Primary antibodies used claudin-1 (rabbit, 1:250, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, 51–9,000), claudin-2 (rabbit, 1:250, Invitrogen, 51–6,100), occludin (rabbit, 1:250, Invitrogen, 40–4,700), ZO-1 (rabbit, 1:500, Invitrogen, 40–2,200), and β-actin (rabbit, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, 4,970). Rabbit-HRP (1:1,000, 7074S, Cell Signaling Technology) was used as the secondary antibody (Supplementary Table 2). We performed densitometric quantification using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) and removed irrelevant or blank lanes from blot images to present our data in a streamlined way.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Based on the qRT-PCR and western blot results, we selected ZO-1 as the TJ protein for IHC analysis. Two professionally trained pathologists performed the IHC analysis. The immunohistochemical experiment was commissioned by SuperBioChips (SuperBioChips Laboratories, Seoul, Korea). The primary antibody used was ZO-1 (rabbit, 1:20, ATLAS, Stockholm, Sweden). Samples were analyzed using the BX43F microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Expression percentage was assessed as a ratio between the number of cells stained with ZO-1 divided by the total number of cells counted in a section. ZO-1 expression was quantified using the ImageJ software. (IHC score, diffuse + strong = 3, focal + strong or diffuse + weak = 2; focal + weak = 1; negative = 0) (Supplementary Table 2).

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, LLC, Boston, MA, USA). Data were expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. The IBS and control groups were analyzed by age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). Each classification criterion was explained in the questionnaire. One-way analysis of variance test and unpaired t-test were used to compare data between different groups. When the number of samples was greater than 10 and less than 30, the normality test was used to analyze the data, and the Mann–Whitney test and Kruskal–Wallis test were used to analyze the data with less than 10 samples. p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

The study’s protocol received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyungpook National University Hospital (IRB 2019-06-020), and written informed consent was secured from all participants.

RESULTS

This study included 36 participants with IBS and 24 controls. The baseline characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Twenty-three and thirteen patients were included in the IBS group’s young- and old-aged groups, respectively. The control group consisted of 24 participants, of whom 12 and 12 were included in the young- and old-aged groups, respectively. The mild and moderate-to-severe IBS groups comprised 16 and 20 participants, respectively. The average symptom duration in patients with IBS was 34.3 weeks. Moreover, all groups had more than 32 weeks of symptom duration. The average and standard deviation of symptom duration in the IBS subgroups are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of healthy controls and patients with IBS

| Variable | Control (n = 24) | IBS (n = 36) |

p value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Severity |

Aging |

|

|||||||

| Young-aged control (n = 12) | Old-aged control (n = 12) | IBS1 (n = 16) | IBS2 (n = 20) | Young-aged IBS (n = 23) | Old-aged IBS (n = 13) | Control vs. IBS | Among IBS severity | Control (M vs. F) | IBS (M vs. F) | |

| Age (yr) | 59.3 ± 13.4 | 48.6 ± 16.5 | 0.011 | 0.526 | 0.940 | 0.073 | ||||

| 47.8 ± 5.4 | 70.7 ± 7.9 | 46.6 ± 15.0 | 50.2 ± 17.8 | 37.8 ± 8.9 | 67.7 ± 5.6 | |||||

| Sex (M/F) | 14/10 | 17/19 | 0.399 | 0.086 | NA | NA | ||||

| 8/4 | 6/6 | 5/11 | 12/8 | 13/10 | 4/9 | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 2.0 | 22.3 ± 3.0 | 0.080 | 0.628 | NA | NA | ||||

| 23.5 ± 1.5 | 23.2 ± 2.5 | 22.3 ± 3.5 | 22.2 ± 2.8 | 23.1 ± 2.8 | 20.9 ± 2.9 | |||||

| IBS symptom duration (wk) | NA | 34.3 ± 12.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| 36.0 ± 22.6 | 33.7 ± 10.3 | 34.8 ± 14.3 | 32.5 ± 3.5 | |||||||

Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean or number only.

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS1, mild IBS, IBS-SSS questionnaire < 176; IBS-2, moderate-to-severe IBS, IBS-SSS questionnaire ≥ 176; Young-aged IBS, aged 20–59 years; Old-aged IBS, age ≥ 65 years; M, male; F, female; BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable.

p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

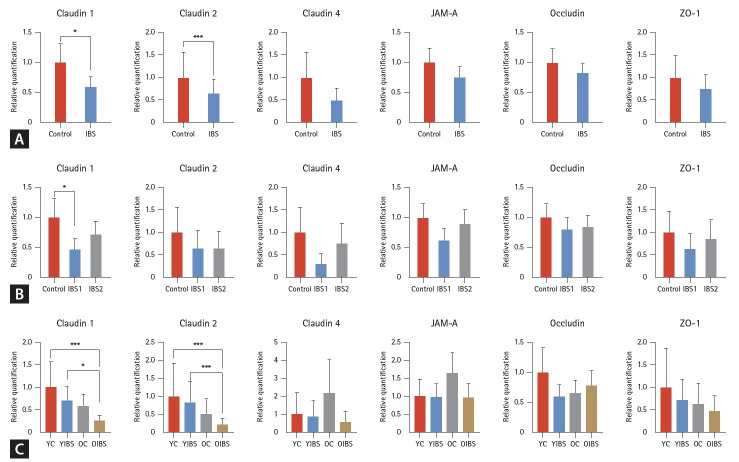

qRT-PCR analysis of TJ mRNA

Compared with the control group, claudin-1, -2, -4, junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A), occludin, and ZO-1 mRNA levels all showed a tendency to decrease the IBS group. However, only claudin-1 and -2 showed a statistically significant decrease (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). In the subgroup analysis, the mild IBS group tended to have lower mRNA levels than the control group; however, only claudin-1 showed a statistically significantly decrease (p < 0.05), and no significant difference was noted in claudin-2, -4, JAM-A, occludin, and ZO-1 (Fig. 1B). Claudin-1, -2, and ZO-1 showed a tendency to decrease in the old-aged and IBS groups. However, claudin-4, JAM-A, and occludin did not show any tendency or statistical significance. Claudins-1 and -2 were statistically significantly reduced in the old IBS group compared to the young IBS group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). In the subgroup analysis by sex, the decrease in Claudin-1, Claudin-2, and ZO-1 TJ mRNA levels in IBS patients was found to have a greater effect in women than in men, although this difference was not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 2). In the analysis by BMI, TJ mRNA levels tended to increase in cases of obesity, but this trend also did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Claudin-1, -2, -4, JAM-A, occludin, and ZO-1 mRNA expression levels using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in the colonic mucosa of the controls and patients with IBS according to IBS severity and aging. (A) mRNA expression levels with or without IBS. (B) mRNA expression levels according to IBS severity. (C) mRNA expression levels according to IBS severity and aging. JAM-A, junctional adhesion molecule; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-1 (mild), IBS-SSS questionnaire < 176 (n = 14); IBS-2 (moderate-to-severe), IBS-SSS questionnaire ≥ 176 (n = 20); YC, young (age 20–59 yr) control (n = 12); YIBS, young (age 20–59 yr) patient with irritable bowel syndrome (n = 21); OC, old (age ≥ 65 yr) control (n = 12); OIBS, old (age ≥ 65 yr) patient with irritable bowel syndrome (n = 13). *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

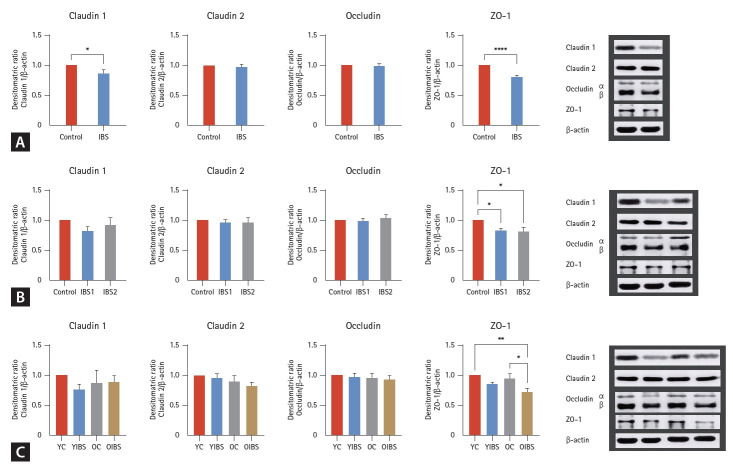

Western blot analysis of TJ proteins

Claudin-1, -2, occludin, and ZO-1 protein levels were measured by western blot. Compared with the control group, claudin-1, -2, occludin, and ZO-1 protein levels all showed a tendency to decrease in the IBS group. Furthermore, claudin-1 (p = 0.040) and ZO-1 (p < 0.0001) protein levels showed a statistically significant decrease in the IBS group (Fig. 2A). In the subgroup analysis, claudin-1 (p = 0.304), -2 (p = 0.832), and occludin (p = 0.690) protein levels showed no significant difference in IBS severity; however, only ZO-1 showed a statistically significant decreased level in both the mild (p = 0.031) and moderate-to-severe IBS groups (p = 0.006) (Fig. 2B). Regarding claudin-1, -2, occludin, and ZO-1 protein levels, a tendency to decrease was observed in the old-aged groups compared with those in the youngaged group. However, claudin-1 (p = 0.452), -2 (p = 0.291), and occludin (p = 0.883) showed no statistical significance. Compared with the young- and old-aged control group, the old-aged IBS group showed a significantly decreased ZO-1 level (p = 0.047) (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Claudin-1, -2, occludin, and ZO-1 in western blot analysis. (A) mRNA expression levels with or without IBS. (B) mRNA expression levels according to IBS severity. (C) mRNA expression levels according to IBS and aging. ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-1 (mild), IBS-SSS questionnaire < 176 (n = 14); IBS-2 (moderate-to-severe), IBS-SSS questionnaire ≥ 176 (n = 20); YC, young (age 20–59 yr) control (n = 12); YIBS, young (age 20–59 yr) patient with irritable bowel syndrome (n = 21); OC, old (age ≥ 65 yr) control (n = 12); OIBS, old (age ≥ 65 yr) patient with irritable bowel syndrome (n = 13). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005; ****p < 0.0001.

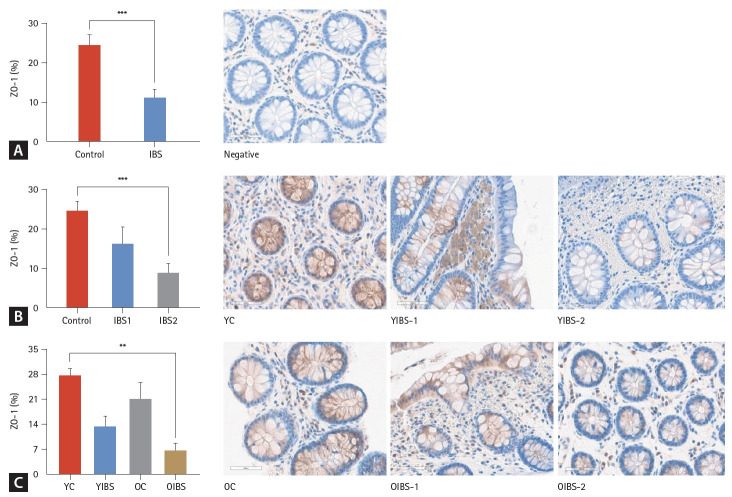

IHC analysis of ZO-1

In the IHC analysis, patients with IBS showed a significantly lower ZO-1 expression than controls (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). In the subgroup analysis, both mild and moderate-to-severe IBS groups tended to have lower ZO-1 expression levels than the control group. However, the mild IBS group did not show statistical significance (p = 0.229), and the moderate-to-severe IBS group had a significantly lower ZO-1 expression level than the control group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). The young-aged group tended to have a higher ZO-1 expression level. Older age and moderate to severe symptoms tended to be associated with lower levels of ZO-1 expression. In the subtype analysis according to age, no difference was observed between the young-versus old-aged control groups (p = 0.506), and the young-versus old-aged IBS groups (p = 0.515). The old-aged IBS groups (p < 0.05) showed a statistically significantly lower ZO-1 expression than the young-aged control group (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

ZO-1 in the immunohistochemical analysis (×40). (A) mRNA expression levels with or without IBS. (B) mRNA expression levels according to IBS severity. (C) mRNA expression levels according to IBS and aging. ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-1 (mild), IBS-SSS questionnaire < 176 (n = 14); IBS-2 (moderate-to-severe), IBS-SSS questionnaire ≥ 176 (n = 20); YC, young (age 20–59 yr) control (n = 12); YIBS, young (age 20–59 yr) patient with irritable bowel syndrome (n = 21);

DISCUSSION

Our study elucidates the complex interplay between TJ protein expression, aging, and disease severity in patients with IBS-D. The differential expression of TJ mRNA or proteins, notably claudin-1, -2, occludin, and ZO-1, underscores the multifaceted nature of IBS-D pathophysiology, particularly in the context of intestinal barrier function.

The statistically significant decrease in claudin-1 and -2 mRNA levels in the IBS group compared to controls (p < 0.05) highlights the potential role of these gene expres-sions in contributing to the compromised intestinal barrier integrity observed in IBS-D. Claudin-1 and -2 are crucial for maintaining the selectivity and permeability of the TJ barrier, and their decreased expression may facilitate increased intestinal permeability, a hallmark feature observed in many IBS-D patients [22,23]. This phenomenon could exacerbate the translocation of luminal contents, thereby triggering inflammatory responses and symptomatology associated with IBS-D [20]. Notably, the specificity of ZO-1’s significant decrease across different analyses (western blot and IHC) further supports its critical role in TJ integrity and the pathogenesis of IBS-D. The reduction in ZO-1 protein, particularly pronounced in the old-aged IBS group and the moderate- to-severe IBS subgroup, aligns with existing theories suggesting a degradation of intestinal barrier function with aging and increased disease severity.

The paracellular permeability of the intestinal barrier is regulated by a complex protein system that constitutes TJs. Transcellular or paracellular pathways can be described in three ways. The first is the pore pathway, which is a high-capacity size- and charge-selection pathway regulated by the claudin family [24]. The second is the leak pathway, which is a nonselective low-dose pathway primarily regulated by ZO-1, occludin, and myosin light chain kinase [25,26]. Finally, unrestricted pathways are opened owing to the loss of TJ complexes, usually as a result of cell death, apoptosis, or mucosal damage. This pathway can allow the passage of large macromolecules and even microorganisms across the epithelium [12]. A decreased membrane protein expression triggers an inflammatory response in the intestinal wall, thereby leading to changes in intestinal sensitivity and motility with intestinal barrier permeability disruption [10,22,23]. Coëffier et al. [27] have linked epithelial barrier disruption and increased permeability to both the downregulation of the TJ scaffolding protein ZO-1 and proteasome-mediated occludin degradation in the colonic mucosa of patients with IBS. Several studies have shown increased intestinal barrier permeability and decreased TJ protein expression in patients with IBS-D. ZO-1 and occludin protein expressions were significantly lower in the colonic mucosa of patients with IBS compared with those of the controls. Zeng et al. [28] have reported that the mRNA expressions of ZO-1 and occludin were significantly reduced in IBS-D. Camilleri et al. [29] have reported that the RNA sequencing of claudin-1 was reduced in IBS-D. Zhen et al. [30] have stated that patients with IBS‑D had significantly reduced occludin production compared with the controls. Moreover, Lee et al. [10] reported that ZO-1 gene expression was decreased in females, and no difference in claudin-1 and occluding was observed. Western blot showed a decrease in ZO-1 [10]. However, in some studies, no differences were noted. Ishimoto et al. [31] and Camilleri et al. [32] have shown that the mRNA levels of ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-1 were similar between each IBS subtype and controls. The expression of TJ proteins showed different results in each study, and no clear data were observed on the subgroup (Table 2). In our study, western blot analysis revealed that patients with IBS exhibited significantly decreased levels of claudin-1 and ZO-1 proteins (p < 0.05). Subgroup analysis showed that ZO-1 protein levels were significantly lower in both mild and moderate-to-severe IBS groups (p < 0.05). In the older IBS group, ZO-1 protein levels were significantly lower than those in the younger IBS group (p < 0.05). The IHC analysis showed that patients with IBS had significantly lower ZO-1 expression compared to those in the control group (p < 0.001). The moderate-to-severe IBS group had significantly lower ZO-1 expression levels than the control group (p < 0.001). The older IBS groups (p = 0.039) showed statistically significant lower ZO-1 expression compared to the control group. The ZO-1 expression level decreased with age. Further, it was lower in individuals with more severe IBS symptoms. In a rat model, age-induced mRNA expression downregulation and decreased ZO-1 and occludin protein expressions were observed in the ileum [30]. Previous studies on the expression of TJ proteins related to age and severity lacked sufficient data in humans. Our study may provide evidence for changes in TJ proteins according to aging and disease severity. Our findings reveal a nuanced relationship between aging, disease severity, and TJ protein expression, especially ZO-1 protein. While the decrease in TJ proteins was more pronounced in the old-aged IBS group, it’s particularly interesting that age itself did not significantly affect ZO-1 expression levels when comparing young and old control groups. This suggests that the observed alterations in TJ protein expression are more directly associated with the presence and severity of IBS-D rather than aging alone. The significant decrease in ZO-1 expression in the old-aged IBS group compared to young-aged controls, and its statistical significance across different degrees of IBS severity, underscores the potential exacerbating effect of aging on the disease’s impact on intestinal barrier function. These findings align with the hypothesis that IBS-D’s pathophysiology may be partly due to a compromised barrier function, which is further impacted by aging. In this study, the expression levels of mRNA and protein showed a significant decrease in the control group and IBS-D group. However, there was a tendency for these levels to decrease even more in the mild IBS group, contrary to the disease severity. Although the expression levels of mRNA and protein did not correlate with disease severity, particularly in IBS, disease severity is determined based on subjective symptoms felt by the patient using the IBS-SSS questionnaire. Since the method of measuring the severity of these symptoms is not based on pathology and biology, the decrease in TJ mRNA and protein may not align with the symptoms. These changes in TJ proteins may be related to symptoms due to alterations in mucosal permeability and the resulting increase in immune cells and inflammatory mediators caused by a compromised epithelial barrier [33]. Further studies are needed to confirm the association with symptoms.

Table 2.

Changes in colonic mucosal tight junctions in patients with IBS

| Study (year) | IBS type (study population) | Tight junction type | Method (PCR, WB, or IHC) | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zeng et al. (2008) [28] | IBS-D (n = 30) | Occludin | PCR | ↓Occludin |

| Camilleri et al. (2015) [29] | IBS-D (n = 47) | CLDN-1, ZO-1, Occludin | RNA sequencing | ↓CLDN-1, = ZO-1, Occludin |

| Zhen et al. (2015) [30] | IBS-D (n = 42) | Occludin | WB, IHC | WB: ↓occludin |

| IHC: occludin (faint and discontinuous) | ||||

| Lee et al. (2015) [10] | IBS-D (n = 21) | ZO-1, CLDN-1, Occludin | PCR, WB | PCR: ↓ZO-1 in females, = CLDN-1, Occludin WB: ↓ZO-1 |

| Camilleri et al. (2014) [32] | IBS-D (n = 9) | Occludin, ZO-1 | PCR | = CLDN-1, Occludin, ZO-1 |

| Ishimoto et al. (2017) [31] | IBS-D (n = 17) | CLDN-1, CLDN-2, CLDN-7, JAM-1, Occludin, ZO-1 | PCR | PCR: = CLDN-1, CLDN-2, CLDN-7, JAM-1, Occludin, ZO-1 |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WB, western blot; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IBS-D, IBS with predominant diarrhea; CLDN, claudin; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; RNA, ribonucleic acid; JAM, junctional adhesion molecule.

This study had several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size and the different number of samples per group limited the ability to conduct appropriate analyses of generalizations and subtypes. Second, biopsy samples were taken from the sigmoid colon, and TJ protein expression may vary depending on the location in the GI tract, making identification of the entire intestine difficult. In addition, most previous studies have been conducted in the sigmoid colon, and there is a lack of research in other regions of GI tract. The expression of TJ proteins is not consistent across different sites [22]. Third, this study focused on patients with IBS-D; therefore, results may vary depending on different subtypes. Fourth, IBS is a multifactorial disorder wherein dietary habits, lifestyle, and other potential contributing factors may be present, and these factors may not be considered or controlled. Finally, to evaluate TJ proteins, we utilized various techniques (qRT-PCR, western blot, and IHC). Variability in methodologies and potential technical limitations may introduce bias or affect the consistency of results. Additionally, there may be limitations in terms of specific populations, cross-sectional studies, and clinical relevance.

Our study demonstrates that IBS-D is associated with significant alterations in the expression of specific TJ mRNA and proteins, notably claudin-1, -2, and ZO-1. These changes are further influenced by the severity of the disease and the age of the patients, suggesting that interventions aimed at restoring TJ protein expression could be beneficial, especially in older patients or those with moderate-to-severe IBS-D. Future research should focus on elucidating the mechanisms underlying these alterations and exploring therapeutic strategies to enhance intestinal barrier function in IBS-D.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Age and disease severity are associated with alterations in tight junction proteins, which may contribute to increased intestinal permeability in IBS patients.

2. Tight junction protein ZO-1 expression is significantly decreased in patients with IBS, especially in older patients and those with more severe symptoms.

3. This study suggests that ZO-1 is the prominent tight junction protein involved in the pathogenesis of IBS, with potential implications for understanding the disease mechanisms in older populations.

Footnotes

CRedit authorship contributions

Sang Un Kim: data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Ji A Choi: formal analysis, writing - original draft; Man-Hoon Han: methodology, investigation, writing - review & editing, supervision; Jin Young Choi: methodology, investigation, formal analysis; Ji Hye Park: resources, data curation, formal analysis, visualization; Moon Sik Kim: methodology, resources, investigation, formal analysis; Yong Hwan Kwon: conceptualization, methodology, resources, investigation, data curation, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

The research was supported by Biomedical Research Institute grant, Kyungpook National University Hospital (2020).

Supplementary Information

REFERENCES

- 1.Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16014. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71–80. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313:949–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1023–1034. doi: 10.1111/apt.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moshiree B. Irritable bowel syndrome. In: Rao SSC, Lee YY, Ghoshal UC. Clinical and basic neurogastroenterology and motility. London: Academic Press, 2020:Chapter 30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM. Tight junctions and the molecular basis for regulation of paracellular permeability. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(4 Pt 1):G467–G475. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.4.G467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene C, Hanley N, Campbell M. Claudin-5: gatekeeper of neurological function. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2019;16:3. doi: 10.1186/s12987-019-0123-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH. Intestinal permeability regulation by tight junction: implication on inflammatory bowel diseases. Intest Res. 2015;13:11–18. doi: 10.5217/ir.2015.13.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arrieta MC, Bistritz L, Meddings JB. Alterations in intestinal permeability. Gut. 2006;55:1512–1520. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horowitz A, Chanez-Paredes SD, Haest X, Turner JR. Paracellular permeability and tight junction regulation in gut health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:417–432. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy KM, Skare IB, Stankewich MC, et al. Occludin is a functional component of the tight junction. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 9):2287–2298. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.9.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inai T, Kobayashi J, Shibata Y. Claudin-1 contributes to the epithelial barrier function in MDCK cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78:849–855. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fanning AS, Anderson JM. Zonula occludens-1 and -2 are cytosolic scaffolds that regulate the assembly of cellular junctions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piche T, Barbara G, Aubert P, et al. Impaired intestinal barrier integrity in the colon of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: involvement of soluble mediators. Gut. 2009;58:196–201. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.140806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeeshan MH, Vakkalagadda NP, Sree GS, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: prevalence and risk factors. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022;81:104408. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1262–1279.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertiaux-Vandaële N, Youmba SB, Belmonte L, et al. The expression and the cellular distribution of the tight junction proteins are altered in irritable bowel syndrome patients with differences according to the disease subtype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2165–2173. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:634–641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanning N, Edwinson AL, Ceuleers H, et al. Intestinal barrier dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284821993586. doi: 10.1177/1756284821993586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng P, Yao J, Wang C, Zhang L, Kong W. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of tight junction dysfunction in the irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:3257–3264. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai PY, Zhang B, He WQ, et al. IL-22 upregulates epithelial claudin-2 to drive diarrhea and enteric pathogen clearance. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:671–681.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber CR, Raleigh DR, Su L, et al. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase activation induces mucosal interleukin-13 expression to alter tight junction ion selectivity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12037–12046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchiando AM, Shen L, Graham WV, et al. Caveolin-1-dependent occludin endocytosis is required for TNF-induced tight junction regulation in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:111–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200902153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coëffier M, Gloro R, Boukhettala N, et al. Increased proteasome-mediated degradation of occludin in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1181–1188. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng J, Li YQ, Zuo XL, Zhen YB, Yang J, Liu CH. Clinical trial: effect of active lactic acid bacteria on mucosal barrier function in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:994–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camilleri M, Carlson P, Acosta A, Busciglio I. Colonic mucosal gene expression and genotype in irritable bowel syndrome patients with normal or elevated fecal bile acid excretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G10–G20. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00080.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhen Y, Chu C, Zhou S, Qi M, Shu R. Imbalance of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-8 and interleukin-10 production evokes barrier dysfunction, severe abdominal symptoms and psychological disorders in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-associated diarrhea. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5239–5245. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishimoto H, Oshima T, Sei H, et al. Claudin-2 expression is upregulated in the ileum of diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2017;60:146–150. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.16-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camilleri M, Carlson P, Acosta A, et al. RNA sequencing shows transcriptomic changes in rectosigmoid mucosa in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: a pilot case-control study. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G1089–G1098. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00068.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piche T. Tight junctions and IBS--the link between epithelial permeability, low-grade inflammation, and symptom generation? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:296–302. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.